User login

Harm Reduction Integration in an Interprofessional Primary Care Training Clinic

Background

Among people who use drugs (PWUD), harm reduction (HR) is an evidence-based low barrier approach to mitigating ongoing substance use risks and is considered a key pillar of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Overdose Prevention Strategy.1 Given the accessibility and continuity, primary care (PC) clinics are optimal sites for education about and provision of HR services.2,3

Aim

- Determining the impact of active and passive methods for HR supply.

- Recognizing the importance of clinician addiction education in the provision of HR services.

Methods

In January 2024, physician and nurse practitioner trainees in the West Haven Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Education (CoE) in Interprofessional Primary Care received addiction care and HR strategy education. Initially, all patients presenting to the CoE completed a single-item substance use screening. Patients screening positive were offered HR supplies, including fentanyl and xylazine test strips (FTS, XTS), during the encounter (active distribution). Starting October 2024, HR kiosks were implemented in the clinic lobby, offering patients self-serve access to HR supplies (passive distribution). Test strip uptake was tracked through clinical encounter documentation and weekly kiosk inventory.

Results

Between January 2024 and June 2024, 92 FTS and 84 XTS were actively distributed. Upon implementation of the harm reduction kiosk, 253 FTS and 164 XTS were distributed between October 2024 and February 2025. In the CoE, FTS and XTS distribution increased by 275% and 195%, respectively, through passive kiosk distribution relative to active distribution during clinical encounters.

Conclusions

HR kiosk implementation resulted in significantly increased test strip uptake in the CoE, proving passive distribution to be an effective low barrier method of increasing access to HR and substance use disorder (SUD) resources. Although this model may reduce stigma and logistical barriers when presenting for a healthcare encounter, it limits the ability to track and engage patients for more intensive services. While each approach has unique advantages and disadvantages, test strip demand via both methods highlights the significant need for HR resources in PC settings. Continuing education for PC clinicians on low barrier SUD care and HR is critical to optimizing care for this population.

- Haffajee, RL, Sherry, TB, Dubenitz, JM, et al. Overdose prevention strategy. US Department of Health and Human Services (Issue Brief). Published October 27, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-02-00-005. Published December 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

Background

Among people who use drugs (PWUD), harm reduction (HR) is an evidence-based low barrier approach to mitigating ongoing substance use risks and is considered a key pillar of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Overdose Prevention Strategy.1 Given the accessibility and continuity, primary care (PC) clinics are optimal sites for education about and provision of HR services.2,3

Aim

- Determining the impact of active and passive methods for HR supply.

- Recognizing the importance of clinician addiction education in the provision of HR services.

Methods

In January 2024, physician and nurse practitioner trainees in the West Haven Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Education (CoE) in Interprofessional Primary Care received addiction care and HR strategy education. Initially, all patients presenting to the CoE completed a single-item substance use screening. Patients screening positive were offered HR supplies, including fentanyl and xylazine test strips (FTS, XTS), during the encounter (active distribution). Starting October 2024, HR kiosks were implemented in the clinic lobby, offering patients self-serve access to HR supplies (passive distribution). Test strip uptake was tracked through clinical encounter documentation and weekly kiosk inventory.

Results

Between January 2024 and June 2024, 92 FTS and 84 XTS were actively distributed. Upon implementation of the harm reduction kiosk, 253 FTS and 164 XTS were distributed between October 2024 and February 2025. In the CoE, FTS and XTS distribution increased by 275% and 195%, respectively, through passive kiosk distribution relative to active distribution during clinical encounters.

Conclusions

HR kiosk implementation resulted in significantly increased test strip uptake in the CoE, proving passive distribution to be an effective low barrier method of increasing access to HR and substance use disorder (SUD) resources. Although this model may reduce stigma and logistical barriers when presenting for a healthcare encounter, it limits the ability to track and engage patients for more intensive services. While each approach has unique advantages and disadvantages, test strip demand via both methods highlights the significant need for HR resources in PC settings. Continuing education for PC clinicians on low barrier SUD care and HR is critical to optimizing care for this population.

Background

Among people who use drugs (PWUD), harm reduction (HR) is an evidence-based low barrier approach to mitigating ongoing substance use risks and is considered a key pillar of the Department of Health and Human Service’s Overdose Prevention Strategy.1 Given the accessibility and continuity, primary care (PC) clinics are optimal sites for education about and provision of HR services.2,3

Aim

- Determining the impact of active and passive methods for HR supply.

- Recognizing the importance of clinician addiction education in the provision of HR services.

Methods

In January 2024, physician and nurse practitioner trainees in the West Haven Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Education (CoE) in Interprofessional Primary Care received addiction care and HR strategy education. Initially, all patients presenting to the CoE completed a single-item substance use screening. Patients screening positive were offered HR supplies, including fentanyl and xylazine test strips (FTS, XTS), during the encounter (active distribution). Starting October 2024, HR kiosks were implemented in the clinic lobby, offering patients self-serve access to HR supplies (passive distribution). Test strip uptake was tracked through clinical encounter documentation and weekly kiosk inventory.

Results

Between January 2024 and June 2024, 92 FTS and 84 XTS were actively distributed. Upon implementation of the harm reduction kiosk, 253 FTS and 164 XTS were distributed between October 2024 and February 2025. In the CoE, FTS and XTS distribution increased by 275% and 195%, respectively, through passive kiosk distribution relative to active distribution during clinical encounters.

Conclusions

HR kiosk implementation resulted in significantly increased test strip uptake in the CoE, proving passive distribution to be an effective low barrier method of increasing access to HR and substance use disorder (SUD) resources. Although this model may reduce stigma and logistical barriers when presenting for a healthcare encounter, it limits the ability to track and engage patients for more intensive services. While each approach has unique advantages and disadvantages, test strip demand via both methods highlights the significant need for HR resources in PC settings. Continuing education for PC clinicians on low barrier SUD care and HR is critical to optimizing care for this population.

- Haffajee, RL, Sherry, TB, Dubenitz, JM, et al. Overdose prevention strategy. US Department of Health and Human Services (Issue Brief). Published October 27, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-02-00-005. Published December 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

- Haffajee, RL, Sherry, TB, Dubenitz, JM, et al. Overdose prevention strategy. US Department of Health and Human Services (Issue Brief). Published October 27, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-02-00-005. Published December 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

Building Trust: Enhancing Rural Women Veterans’ Healthcare Experiences Through Need-Supportive Patient-Centered Communication

Background

Rural women veterans often confront unique healthcare barriers—geographic isolation, gender-related stigma, and limited provider cultural sensitivity that undermine trust and engagement. In response, we co-designed an interprofessional communication curriculum to promote relational, patient-centered care grounded in psychological need support.

Innovation

Anchored in Self Determination Theory (SDT), this curriculum equips nurses and social workers with need-supportive communication strategies that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness, integrating two transformative learning methods for enhancing respectful and inclusive listening:

- Cultural humility reflections for veteran-centered care—personal narratives, storytelling, and power-awareness discussions to build lifelong reflective practices.

- Medical improv simulations—adaptive improvisational role plays for healthcare environments fostering presence, adaptability, empathy, trust-building, and real-time responsiveness.

Delivered via a multiday health professions learning lab, the training combines asynchronous workshops with in-person facilitated interactions. Core modules cover SDT foundations, need supportive dialogue, veteran-centered cultural humility, and shared decision-making practices that uplift rural women veterans’ voices. Using Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Model, we assess impact at multiple tiers:

- Reaction: Participant satisfaction and perceived training relevance.

- Learning: Pre/post assessments track SDT knowledge and communication skills gains.

- Behavior: Observe simulations and self-reported changes in communication practices.

- Results: Qualitative satisfaction metrics and care engagement trends among rural women veterans.

Results

A pilot cohort (N = 20) across two rural sites is pending implementation. pre/post surveys will assess any improved confidence in applying need supportive communication and the most effective component in building empathetic presence. Feedback measures will also indicate the significance of combined uses of medical improv and cultural humility on deepened relational capacity and trust.

Discussion

This program operationalizes SDT within healthcare communications, integrating cultural humility and improvisation learning modalities to enhance care quality for rural women veterans, ultimately strengthening provider-patient connections. Using health professions learning lab environments can foster sustained behavioral impacts. Future iterations will expand to additional rural VA sites, co-designing with the voices of women veterans through focus groups.

Background

Rural women veterans often confront unique healthcare barriers—geographic isolation, gender-related stigma, and limited provider cultural sensitivity that undermine trust and engagement. In response, we co-designed an interprofessional communication curriculum to promote relational, patient-centered care grounded in psychological need support.

Innovation

Anchored in Self Determination Theory (SDT), this curriculum equips nurses and social workers with need-supportive communication strategies that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness, integrating two transformative learning methods for enhancing respectful and inclusive listening:

- Cultural humility reflections for veteran-centered care—personal narratives, storytelling, and power-awareness discussions to build lifelong reflective practices.

- Medical improv simulations—adaptive improvisational role plays for healthcare environments fostering presence, adaptability, empathy, trust-building, and real-time responsiveness.

Delivered via a multiday health professions learning lab, the training combines asynchronous workshops with in-person facilitated interactions. Core modules cover SDT foundations, need supportive dialogue, veteran-centered cultural humility, and shared decision-making practices that uplift rural women veterans’ voices. Using Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Model, we assess impact at multiple tiers:

- Reaction: Participant satisfaction and perceived training relevance.

- Learning: Pre/post assessments track SDT knowledge and communication skills gains.

- Behavior: Observe simulations and self-reported changes in communication practices.

- Results: Qualitative satisfaction metrics and care engagement trends among rural women veterans.

Results

A pilot cohort (N = 20) across two rural sites is pending implementation. pre/post surveys will assess any improved confidence in applying need supportive communication and the most effective component in building empathetic presence. Feedback measures will also indicate the significance of combined uses of medical improv and cultural humility on deepened relational capacity and trust.

Discussion

This program operationalizes SDT within healthcare communications, integrating cultural humility and improvisation learning modalities to enhance care quality for rural women veterans, ultimately strengthening provider-patient connections. Using health professions learning lab environments can foster sustained behavioral impacts. Future iterations will expand to additional rural VA sites, co-designing with the voices of women veterans through focus groups.

Background

Rural women veterans often confront unique healthcare barriers—geographic isolation, gender-related stigma, and limited provider cultural sensitivity that undermine trust and engagement. In response, we co-designed an interprofessional communication curriculum to promote relational, patient-centered care grounded in psychological need support.

Innovation

Anchored in Self Determination Theory (SDT), this curriculum equips nurses and social workers with need-supportive communication strategies that nurture autonomy, competence, and relatedness, integrating two transformative learning methods for enhancing respectful and inclusive listening:

- Cultural humility reflections for veteran-centered care—personal narratives, storytelling, and power-awareness discussions to build lifelong reflective practices.

- Medical improv simulations—adaptive improvisational role plays for healthcare environments fostering presence, adaptability, empathy, trust-building, and real-time responsiveness.

Delivered via a multiday health professions learning lab, the training combines asynchronous workshops with in-person facilitated interactions. Core modules cover SDT foundations, need supportive dialogue, veteran-centered cultural humility, and shared decision-making practices that uplift rural women veterans’ voices. Using Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Model, we assess impact at multiple tiers:

- Reaction: Participant satisfaction and perceived training relevance.

- Learning: Pre/post assessments track SDT knowledge and communication skills gains.

- Behavior: Observe simulations and self-reported changes in communication practices.

- Results: Qualitative satisfaction metrics and care engagement trends among rural women veterans.

Results

A pilot cohort (N = 20) across two rural sites is pending implementation. pre/post surveys will assess any improved confidence in applying need supportive communication and the most effective component in building empathetic presence. Feedback measures will also indicate the significance of combined uses of medical improv and cultural humility on deepened relational capacity and trust.

Discussion

This program operationalizes SDT within healthcare communications, integrating cultural humility and improvisation learning modalities to enhance care quality for rural women veterans, ultimately strengthening provider-patient connections. Using health professions learning lab environments can foster sustained behavioral impacts. Future iterations will expand to additional rural VA sites, co-designing with the voices of women veterans through focus groups.

Tai Chi Modification and Supplemental Movements Quality Improvement Program

Background

The original program consisted of 12 movements that were to be split up between 3 weeks teaching 4 movements each week. Range of mobility was the main consideration for developing this HPE quality improvement project. Veterans who wanted to participate in Tai Chi were not able to engage in the activity due to the range of movement traditional Tai Chi required.

Innovation

The HPE Quality Improvement program developed a 15-movement warm-up, 12 co-ordinational movements consistent with the original program, 18 supplemental Tai Chi movements that were not included in the original program all of which focus on movements remaining below the shoulders and can be done standing or sitting. Four advanced exercises including “hip over heel” were included to target participants balance if able and to improve their hip strength, knee tendon/ligament strength. Tai Chi loses its potential to increase balance when performed in a sitting position.1 The movements drew upon Fu style Tai Chi and the program developer was given permission from Tommy Kirchoff to use his DVD Healing Exercises. The HPE program consisted of four 30–60-minute weekly sessions of learning the movements with another 4 weekly sessions of demonstrating the movements. Instructors were given written and visual documents to learn from and were evaluated by the developer during the last 4 weeks.

.

Results

Qualitative Data: Instructors notice a difference in how they feel, and appreciate having another option to offer veterans with mobility/standing issues. Patients expressed improvement in mobility relating to bending, arm extension, arm raising, muscle strengthening, hip strengthening and rotation.

Discussion

Future research will want to look at taking measurements before and after patient implementation to determine quantitative data related to balance, strength and range of movement including grip strength, stand up and go, and one-legged stands.

- Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important?. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74-84. Published 2018 Jun 1. doi:10.22540/JFSF-03-074

Background

The original program consisted of 12 movements that were to be split up between 3 weeks teaching 4 movements each week. Range of mobility was the main consideration for developing this HPE quality improvement project. Veterans who wanted to participate in Tai Chi were not able to engage in the activity due to the range of movement traditional Tai Chi required.

Innovation

The HPE Quality Improvement program developed a 15-movement warm-up, 12 co-ordinational movements consistent with the original program, 18 supplemental Tai Chi movements that were not included in the original program all of which focus on movements remaining below the shoulders and can be done standing or sitting. Four advanced exercises including “hip over heel” were included to target participants balance if able and to improve their hip strength, knee tendon/ligament strength. Tai Chi loses its potential to increase balance when performed in a sitting position.1 The movements drew upon Fu style Tai Chi and the program developer was given permission from Tommy Kirchoff to use his DVD Healing Exercises. The HPE program consisted of four 30–60-minute weekly sessions of learning the movements with another 4 weekly sessions of demonstrating the movements. Instructors were given written and visual documents to learn from and were evaluated by the developer during the last 4 weeks.

.

Results

Qualitative Data: Instructors notice a difference in how they feel, and appreciate having another option to offer veterans with mobility/standing issues. Patients expressed improvement in mobility relating to bending, arm extension, arm raising, muscle strengthening, hip strengthening and rotation.

Discussion

Future research will want to look at taking measurements before and after patient implementation to determine quantitative data related to balance, strength and range of movement including grip strength, stand up and go, and one-legged stands.

Background

The original program consisted of 12 movements that were to be split up between 3 weeks teaching 4 movements each week. Range of mobility was the main consideration for developing this HPE quality improvement project. Veterans who wanted to participate in Tai Chi were not able to engage in the activity due to the range of movement traditional Tai Chi required.

Innovation

The HPE Quality Improvement program developed a 15-movement warm-up, 12 co-ordinational movements consistent with the original program, 18 supplemental Tai Chi movements that were not included in the original program all of which focus on movements remaining below the shoulders and can be done standing or sitting. Four advanced exercises including “hip over heel” were included to target participants balance if able and to improve their hip strength, knee tendon/ligament strength. Tai Chi loses its potential to increase balance when performed in a sitting position.1 The movements drew upon Fu style Tai Chi and the program developer was given permission from Tommy Kirchoff to use his DVD Healing Exercises. The HPE program consisted of four 30–60-minute weekly sessions of learning the movements with another 4 weekly sessions of demonstrating the movements. Instructors were given written and visual documents to learn from and were evaluated by the developer during the last 4 weeks.

.

Results

Qualitative Data: Instructors notice a difference in how they feel, and appreciate having another option to offer veterans with mobility/standing issues. Patients expressed improvement in mobility relating to bending, arm extension, arm raising, muscle strengthening, hip strengthening and rotation.

Discussion

Future research will want to look at taking measurements before and after patient implementation to determine quantitative data related to balance, strength and range of movement including grip strength, stand up and go, and one-legged stands.

- Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important?. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74-84. Published 2018 Jun 1. doi:10.22540/JFSF-03-074

- Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important?. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74-84. Published 2018 Jun 1. doi:10.22540/JFSF-03-074

Improving Life-Sustaining Treatment Discussions and Order Quality in a Primary Care Clinic

Background

Veterans Health Administration Directive 1004.03(1) (Advance Care Planning) aims to establish a “system-wide, patient-centered and evidence-based approach to Advance Care Planning.”1 Life-sustaining treatment (LST) orders are documents of patient preference regarding interventions such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, dialysis, artificial nutrition and hydration; and are considered part of an Advance Care Plan. From a bioethics perspective, these orders promote patient autonomy by formalizing patient preferences around LSTs in the medical record, particularly for when a patient lacks capacity and/or cannot make decisions on their own.2 Through consensus building, our team defined vague, inactionable, or incorrectly written LST orders as Potentially Problematic Orders (PPO). PPOs which cause confusion at the bedside or lack clarity around preferences can pose serious risks to patient safety and autonomy by exposing patients to inappropriate initiation or withholding of LSTs. Improving the quality of LST orders and reducing the number of PPOs is a crucial element for safe and effective implementation of Directive 1004.03(1).

Aim

The aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the number of PPOs in a VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) by 75% by the end of 2025.

Methods

The Model for Improvement was used for this quality improvement project.3 One year of LST orders were audited and thematic analysis identified 7 subtypes of PPO. Some PPO subtypes included clerical errors, potentially mismatched order sets (e.g., Comfort Care order with no associated DNR order) ill-defined or vague orders, and clinically impractical orders (eg, “consents to one shock during CPR”). We defined vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders as the most ethically and clinically challenging given the possibility of confusion or error at the bedside. Initial data were collected from October 2022 to October 2023, and post-intervention data were collected from February 2024 to September 2024. Interventions included process changes (clarifying role responsibility, documentation practices, patient education), regular auditing and feedback from a supervisor, and staff education.

Results

Post-intervention analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PPO remained the same, with 25% of patient charts containing at least one PPO. However, the distribution of PPO in the most ethically and clinically problematic categories (vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders) decreased from 14.7% to <1%.

Conclusions

We successfully reduced the most ethically and clinically challenging PPOs to <1% in our initial intervention. To reduce the overall proportion of PPO, we plan enhancements in process automations, additional physical educational resources, and minor changes in audit criteria. Future projects will aim to address the remaining PPO error types and prepare this project for implementation in other CBOCs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1004.03(1): Advance care planning. Published December 12, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11610

- White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2053-2059. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Dolansky MA, Madigosky WS, Miltner RS, Hall AG. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (4th edition). Joint Commission Resources and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2022.

Background

Veterans Health Administration Directive 1004.03(1) (Advance Care Planning) aims to establish a “system-wide, patient-centered and evidence-based approach to Advance Care Planning.”1 Life-sustaining treatment (LST) orders are documents of patient preference regarding interventions such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, dialysis, artificial nutrition and hydration; and are considered part of an Advance Care Plan. From a bioethics perspective, these orders promote patient autonomy by formalizing patient preferences around LSTs in the medical record, particularly for when a patient lacks capacity and/or cannot make decisions on their own.2 Through consensus building, our team defined vague, inactionable, or incorrectly written LST orders as Potentially Problematic Orders (PPO). PPOs which cause confusion at the bedside or lack clarity around preferences can pose serious risks to patient safety and autonomy by exposing patients to inappropriate initiation or withholding of LSTs. Improving the quality of LST orders and reducing the number of PPOs is a crucial element for safe and effective implementation of Directive 1004.03(1).

Aim

The aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the number of PPOs in a VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) by 75% by the end of 2025.

Methods

The Model for Improvement was used for this quality improvement project.3 One year of LST orders were audited and thematic analysis identified 7 subtypes of PPO. Some PPO subtypes included clerical errors, potentially mismatched order sets (e.g., Comfort Care order with no associated DNR order) ill-defined or vague orders, and clinically impractical orders (eg, “consents to one shock during CPR”). We defined vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders as the most ethically and clinically challenging given the possibility of confusion or error at the bedside. Initial data were collected from October 2022 to October 2023, and post-intervention data were collected from February 2024 to September 2024. Interventions included process changes (clarifying role responsibility, documentation practices, patient education), regular auditing and feedback from a supervisor, and staff education.

Results

Post-intervention analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PPO remained the same, with 25% of patient charts containing at least one PPO. However, the distribution of PPO in the most ethically and clinically problematic categories (vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders) decreased from 14.7% to <1%.

Conclusions

We successfully reduced the most ethically and clinically challenging PPOs to <1% in our initial intervention. To reduce the overall proportion of PPO, we plan enhancements in process automations, additional physical educational resources, and minor changes in audit criteria. Future projects will aim to address the remaining PPO error types and prepare this project for implementation in other CBOCs.

Background

Veterans Health Administration Directive 1004.03(1) (Advance Care Planning) aims to establish a “system-wide, patient-centered and evidence-based approach to Advance Care Planning.”1 Life-sustaining treatment (LST) orders are documents of patient preference regarding interventions such as mechanical ventilation, CPR, dialysis, artificial nutrition and hydration; and are considered part of an Advance Care Plan. From a bioethics perspective, these orders promote patient autonomy by formalizing patient preferences around LSTs in the medical record, particularly for when a patient lacks capacity and/or cannot make decisions on their own.2 Through consensus building, our team defined vague, inactionable, or incorrectly written LST orders as Potentially Problematic Orders (PPO). PPOs which cause confusion at the bedside or lack clarity around preferences can pose serious risks to patient safety and autonomy by exposing patients to inappropriate initiation or withholding of LSTs. Improving the quality of LST orders and reducing the number of PPOs is a crucial element for safe and effective implementation of Directive 1004.03(1).

Aim

The aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the number of PPOs in a VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (CBOC) by 75% by the end of 2025.

Methods

The Model for Improvement was used for this quality improvement project.3 One year of LST orders were audited and thematic analysis identified 7 subtypes of PPO. Some PPO subtypes included clerical errors, potentially mismatched order sets (e.g., Comfort Care order with no associated DNR order) ill-defined or vague orders, and clinically impractical orders (eg, “consents to one shock during CPR”). We defined vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders as the most ethically and clinically challenging given the possibility of confusion or error at the bedside. Initial data were collected from October 2022 to October 2023, and post-intervention data were collected from February 2024 to September 2024. Interventions included process changes (clarifying role responsibility, documentation practices, patient education), regular auditing and feedback from a supervisor, and staff education.

Results

Post-intervention analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PPO remained the same, with 25% of patient charts containing at least one PPO. However, the distribution of PPO in the most ethically and clinically problematic categories (vague, ill-defined, and impractical orders) decreased from 14.7% to <1%.

Conclusions

We successfully reduced the most ethically and clinically challenging PPOs to <1% in our initial intervention. To reduce the overall proportion of PPO, we plan enhancements in process automations, additional physical educational resources, and minor changes in audit criteria. Future projects will aim to address the remaining PPO error types and prepare this project for implementation in other CBOCs.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1004.03(1): Advance care planning. Published December 12, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11610

- White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2053-2059. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Dolansky MA, Madigosky WS, Miltner RS, Hall AG. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (4th edition). Joint Commission Resources and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2022.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1004.03(1): Advance care planning. Published December 12, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11610

- White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2053-2059. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1

- Ogrinc GS, Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Dolansky MA, Madigosky WS, Miltner RS, Hall AG. Fundamentals of Health Care Improvement: A Guide to Improving Your Patients’ Care (4th edition). Joint Commission Resources and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2022.

A Health Educator’s Primer to Cost-Effectiveness in Health Professions Education

Background

Cost-effectiveness (CE) evaluations, for existing and anticipated programs, are common in healthcare, but are rarely used in health professions education (HPE). A systematic review of HPE literature found not only few examples of CE evaluations, but also unclear and inconsistent methodology.1 One proposed reason HPE has been slow to adopt CE evaluations is uncertainty over terminology and how to adapt this methodology to HPE.2 CE evaluations present further challenges for HPE since educational outcomes are often not easily monetized. However, given the reality of constrained budgets and limited resources, CE evaluations can be a powerful tool for educators to strengthen arguments for proposed innovations, and for scholars seeking to conduct rigorous work that sustains critical review.

Innovation

This project aims to make CE evaluations more understandable to HPE educators, using a one-page infographic and glossary. This will provide a primer, operationalizing the steps involved in CE evaluations and addressing why and when CE evaluations might be considered in HPE. To improve comprehension, this is being developed collaboratively with health professions educators and an economist. This infographic will be submitted for publication, as a resource to facilitate educators’ scholarly work and conversations with fiscal administrators.

Results

The infographic includes 1) an overview of CE evaluations, 2) information about inputs required for CE evaluations, 3) guidance on interpreting results, 4) a glossary of key terminology, and 5) considerations for why educators might consider this type of analysis. A final draft will be pilot tested with a focus group to assess interdisciplinary accessibility.

Discussion

Discussions between health professions educators and an economist on this infographic uncovered concepts that were poorly understood or defined differently across disciplines, determining specific knowledge gaps and misunderstandings. For example, facilitating conversation between educators and economists highlighted key terms that were a source of misunderstanding. These were then added to the glossary, creating a shared vocabulary. This also helped clarify the steps and information necessary for conducting CE evaluations in HPE, particularly the issue of perspective choice for the analysis (educator, patient, learner, etc.). Overall, this collaboration aimed at making CE evaluations more approachable and understandable for HPE professionals through this infographic.

- Foo J, Cook DA, Walsh K, et al. Cost evaluations in health professions education: a systematic review of methods and reporting quality. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1196-1208. doi:10.1111/medu.13936

- Maloney S, Reeves S, Rivers G, Ilic D, Foo J, Walsh K. The Prato Statement on cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):1-4. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1257255

Background

Cost-effectiveness (CE) evaluations, for existing and anticipated programs, are common in healthcare, but are rarely used in health professions education (HPE). A systematic review of HPE literature found not only few examples of CE evaluations, but also unclear and inconsistent methodology.1 One proposed reason HPE has been slow to adopt CE evaluations is uncertainty over terminology and how to adapt this methodology to HPE.2 CE evaluations present further challenges for HPE since educational outcomes are often not easily monetized. However, given the reality of constrained budgets and limited resources, CE evaluations can be a powerful tool for educators to strengthen arguments for proposed innovations, and for scholars seeking to conduct rigorous work that sustains critical review.

Innovation

This project aims to make CE evaluations more understandable to HPE educators, using a one-page infographic and glossary. This will provide a primer, operationalizing the steps involved in CE evaluations and addressing why and when CE evaluations might be considered in HPE. To improve comprehension, this is being developed collaboratively with health professions educators and an economist. This infographic will be submitted for publication, as a resource to facilitate educators’ scholarly work and conversations with fiscal administrators.

Results

The infographic includes 1) an overview of CE evaluations, 2) information about inputs required for CE evaluations, 3) guidance on interpreting results, 4) a glossary of key terminology, and 5) considerations for why educators might consider this type of analysis. A final draft will be pilot tested with a focus group to assess interdisciplinary accessibility.

Discussion

Discussions between health professions educators and an economist on this infographic uncovered concepts that were poorly understood or defined differently across disciplines, determining specific knowledge gaps and misunderstandings. For example, facilitating conversation between educators and economists highlighted key terms that were a source of misunderstanding. These were then added to the glossary, creating a shared vocabulary. This also helped clarify the steps and information necessary for conducting CE evaluations in HPE, particularly the issue of perspective choice for the analysis (educator, patient, learner, etc.). Overall, this collaboration aimed at making CE evaluations more approachable and understandable for HPE professionals through this infographic.

Background

Cost-effectiveness (CE) evaluations, for existing and anticipated programs, are common in healthcare, but are rarely used in health professions education (HPE). A systematic review of HPE literature found not only few examples of CE evaluations, but also unclear and inconsistent methodology.1 One proposed reason HPE has been slow to adopt CE evaluations is uncertainty over terminology and how to adapt this methodology to HPE.2 CE evaluations present further challenges for HPE since educational outcomes are often not easily monetized. However, given the reality of constrained budgets and limited resources, CE evaluations can be a powerful tool for educators to strengthen arguments for proposed innovations, and for scholars seeking to conduct rigorous work that sustains critical review.

Innovation

This project aims to make CE evaluations more understandable to HPE educators, using a one-page infographic and glossary. This will provide a primer, operationalizing the steps involved in CE evaluations and addressing why and when CE evaluations might be considered in HPE. To improve comprehension, this is being developed collaboratively with health professions educators and an economist. This infographic will be submitted for publication, as a resource to facilitate educators’ scholarly work and conversations with fiscal administrators.

Results

The infographic includes 1) an overview of CE evaluations, 2) information about inputs required for CE evaluations, 3) guidance on interpreting results, 4) a glossary of key terminology, and 5) considerations for why educators might consider this type of analysis. A final draft will be pilot tested with a focus group to assess interdisciplinary accessibility.

Discussion

Discussions between health professions educators and an economist on this infographic uncovered concepts that were poorly understood or defined differently across disciplines, determining specific knowledge gaps and misunderstandings. For example, facilitating conversation between educators and economists highlighted key terms that were a source of misunderstanding. These were then added to the glossary, creating a shared vocabulary. This also helped clarify the steps and information necessary for conducting CE evaluations in HPE, particularly the issue of perspective choice for the analysis (educator, patient, learner, etc.). Overall, this collaboration aimed at making CE evaluations more approachable and understandable for HPE professionals through this infographic.

- Foo J, Cook DA, Walsh K, et al. Cost evaluations in health professions education: a systematic review of methods and reporting quality. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1196-1208. doi:10.1111/medu.13936

- Maloney S, Reeves S, Rivers G, Ilic D, Foo J, Walsh K. The Prato Statement on cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):1-4. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1257255

- Foo J, Cook DA, Walsh K, et al. Cost evaluations in health professions education: a systematic review of methods and reporting quality. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1196-1208. doi:10.1111/medu.13936

- Maloney S, Reeves S, Rivers G, Ilic D, Foo J, Walsh K. The Prato Statement on cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):1-4. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1257255

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

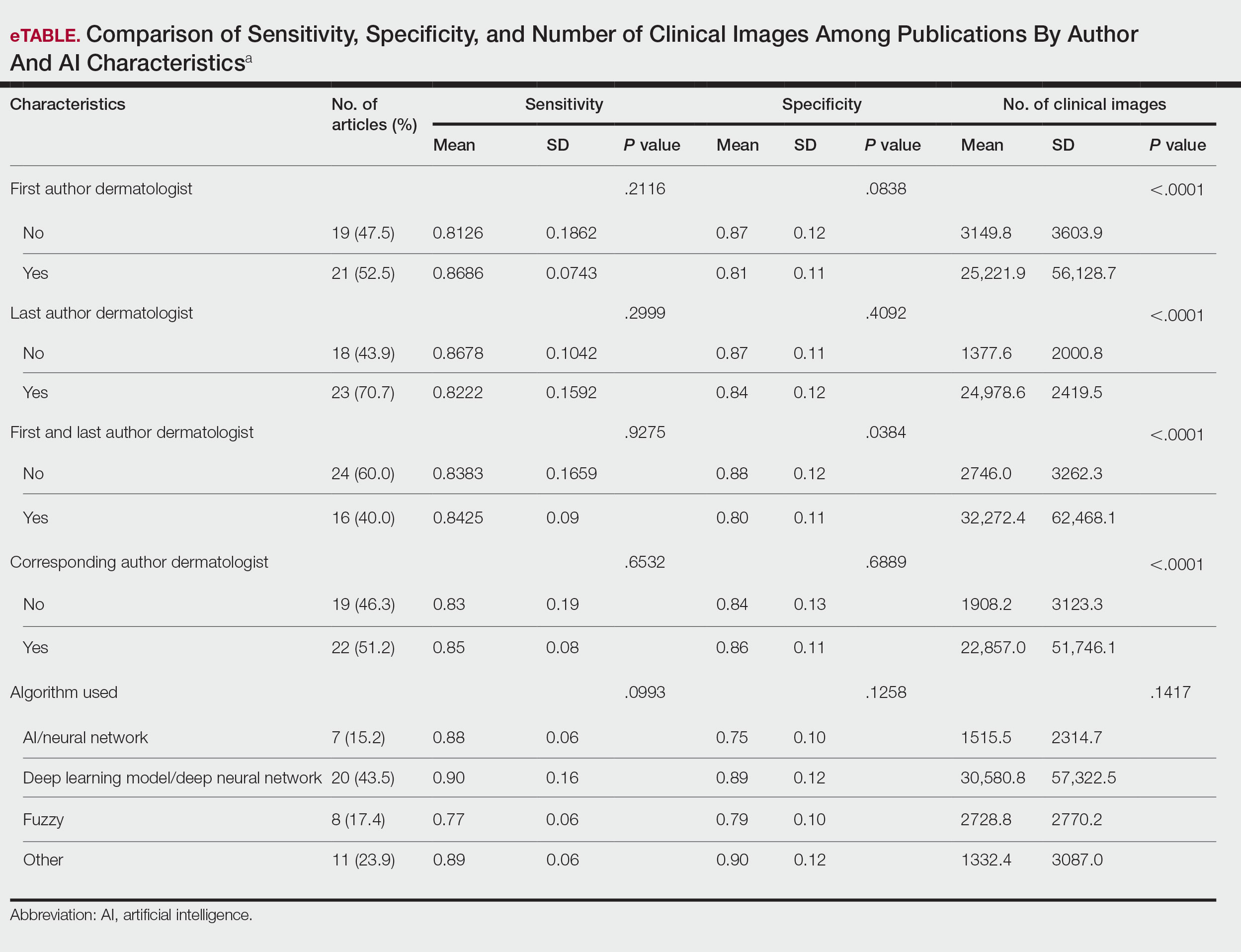

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

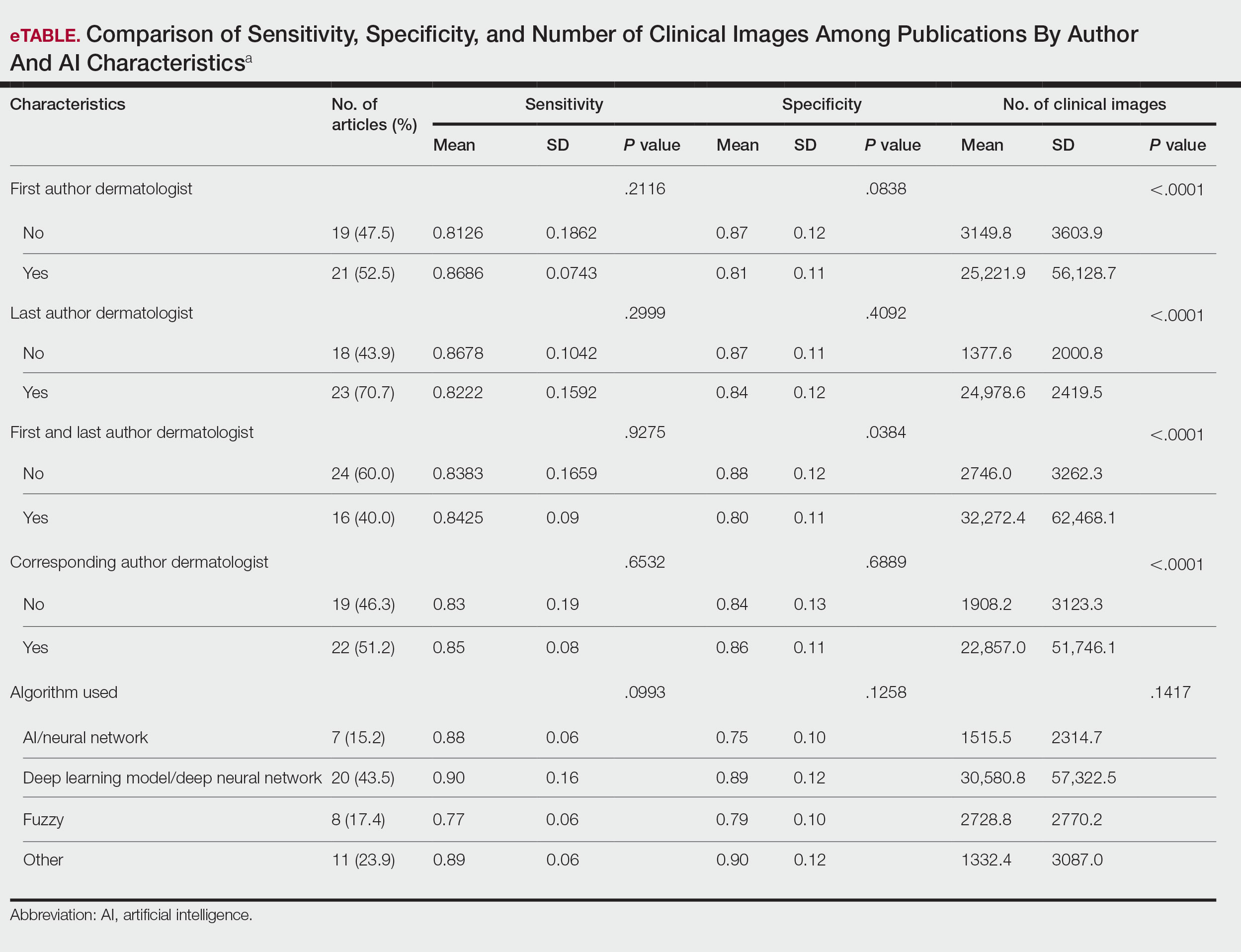

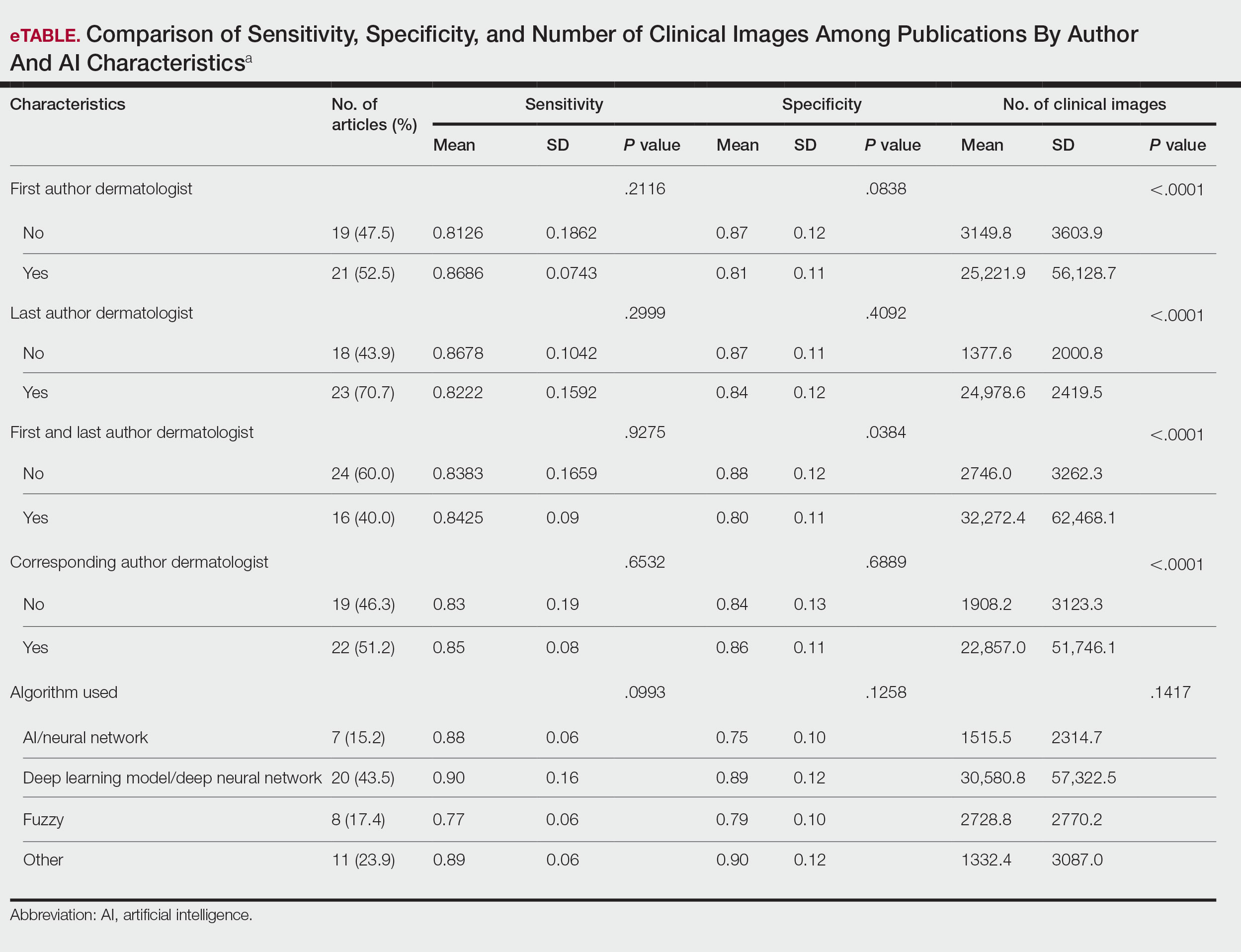

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology application costs increased from 2021 to 2024, largely due to expenses related to away rotations and, in some cases, a return to in-person interviews.

- Away rotations play a critical role in the dermatology match; however, they also contribute substantially to financial burden.

- The cost-saving impact of virtual interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights a meaningful opportunity for future cost reduction.

- Further interventions are needed to meaningfully reduce financial burden and promote equity.

Staff Perspectives on the VISN 20 Tele-Neuropsychology Program

Staff Perspectives on the VISN 20 Tele-Neuropsychology Program

There are 2.7 million (48%) rural veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1 Many VHA-enrolled rural veterans are aged ≥ 65 years (54%), a medically complex population that requires more extensive health care.1 These veterans may live far from US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) and often receive most of their care at rural community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). In addition to face-to-face (F2F) services provided at these clinics, many patient care needs may be met using telehealth technology, which can connect veterans at CBOCs with remote health care practitioners (HCPs).

This technology is used across medical specialties throughout the VA and has expanded into neuropsychology services to improve access amid the shortage of rural neuropsychologists. Prior research suggests that access to neuropsychology services improves the functional outcomes of people with diverse medical conditions, including dementia, brain injury, and epilepsy, and reduces emergency department visits, hospitalization duration, and health care costs.2-6 Given that veterans unable to access neuropsychology services may be at risk for poorer outcomes, identifying ways to improve access is a priority. Tele-neuropsychology (teleNP) has been used to expand access for rural veterans in need of these services.7,8

TeleNP is the application of audiovisual technologies to enable remote clinical encounters for neuropsychological assessments.9 TeleNP has been shown to be generally equivalent to F2F care, without significant differences compared with in-person visits.10-13 TeleNP was increasingly implemented following the COVID-19 pandemic and remains an enduring and expanding feature of neuropsychology care delivery.8,14-18 TeleNP services can increase access to care, especially for rural veterans and those with limited transportation.

Research in non-VA samples suggests a high level of clinician satisfaction with teleNP.16 In VA samples, research has found high levels of patient satisfaction with teleNP both within Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 20 and in a VA health care system outside VISN 20.7,19 Investigating staff perceptions of these services and their utility compared with non-VA F2F visits is pertinent to the overall feasibility and effectiveness of teleNP.

TELE-NEUROPSYCHOLOGY PROGRAM

A clinical resource hub (CRH) is a VISN-governed program that provides veteran health care when local VHA facilities have service gaps.20,21 CRH 20 serves several Pacific Northwest VISN 20 health care systems and began providing teleNP in 2015. The CRH 20 teleNP service serves older adults in rural settings with > 570 teleNP evaluations completed over a recent 12-month period (May 2023 to May 2024). In the CRH 20 teleNP program, veterans are offered services by CRH 20 neuropsychologists via telehealth to a patient’s local VAMC, larger health care clinic, CBOC, or via Veterans Video Connect to the home.

Referral pathways to the CRH 20 teleNP program differ across sites. For VISN 20 sites that do not have any in-house neuropsychology services, referrals are initiated by HCPs from any discipline. At 2 sites with in-house neuropsychology programs, CRH 20 teleNP referrals typically are forwarded from the inhouse service whenever the veteran prefers to be seen at an outlying clinic. All sites, including the CBOCs, are equipped fully for testing, and the HCP encounters veterans in a private office via video-based telehealth technology after a telehealth technician orients them to the space. The private office minimizes environmental disruptions and uses standardized technology to ensure valid results. A limited number of evaluations are offered at home (< 5% of the evaluations) if the veteran is unable to come to a VHA facility, has access to reliable internet, and a minimally distracting home setting.

In VISN 20, teleNP is a routine practice for delivering services to rural sites, most of which lack neuropsychologists. However, there is limited information about the extent to which the referral sources find the service useful. This quality improvement (QI) project aimed to better understand how well-established teleNP services were received by referral sources/stakeholders and how services could be improved. Prior to the advent of the CRH 20 teleNP program, staff had the option of referring for F2F evaluations in the local community (outside the VA) at some sites, an option that remains. This QI project examined staff perspectives on the usefulness of CRH 20 teleNP services compared with non-VA F2F services. We administered an anonymous, confidential survey examining these factors to VISN 20 staff within 4 VA health care systems.

METHODS

This QI project used a mixed quantitative and qualitative descriptive survey design to elicit feedback. The authors (3 neuropsychologists, 1 geropsychologist, and 1 research coordinator) developed the survey questions. The 13-question survey was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential, and respondents were given an opportunity to ask questions, with the first author serving as the point of contact.

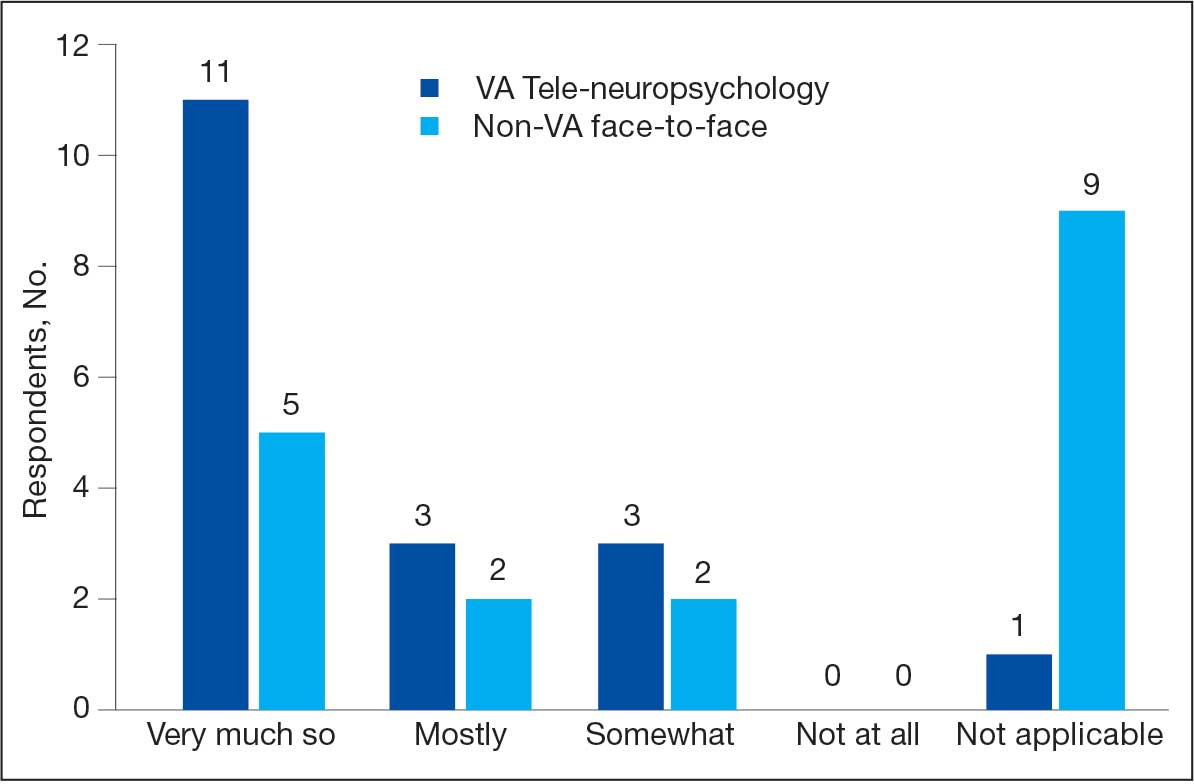

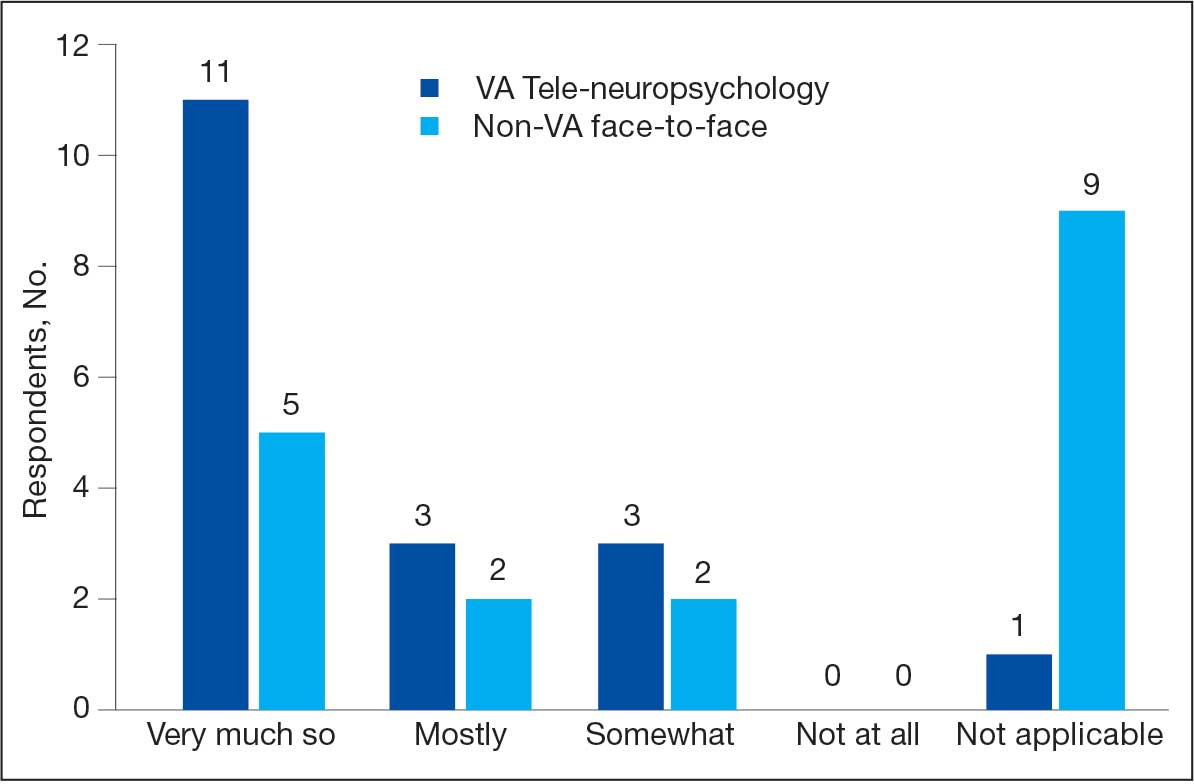

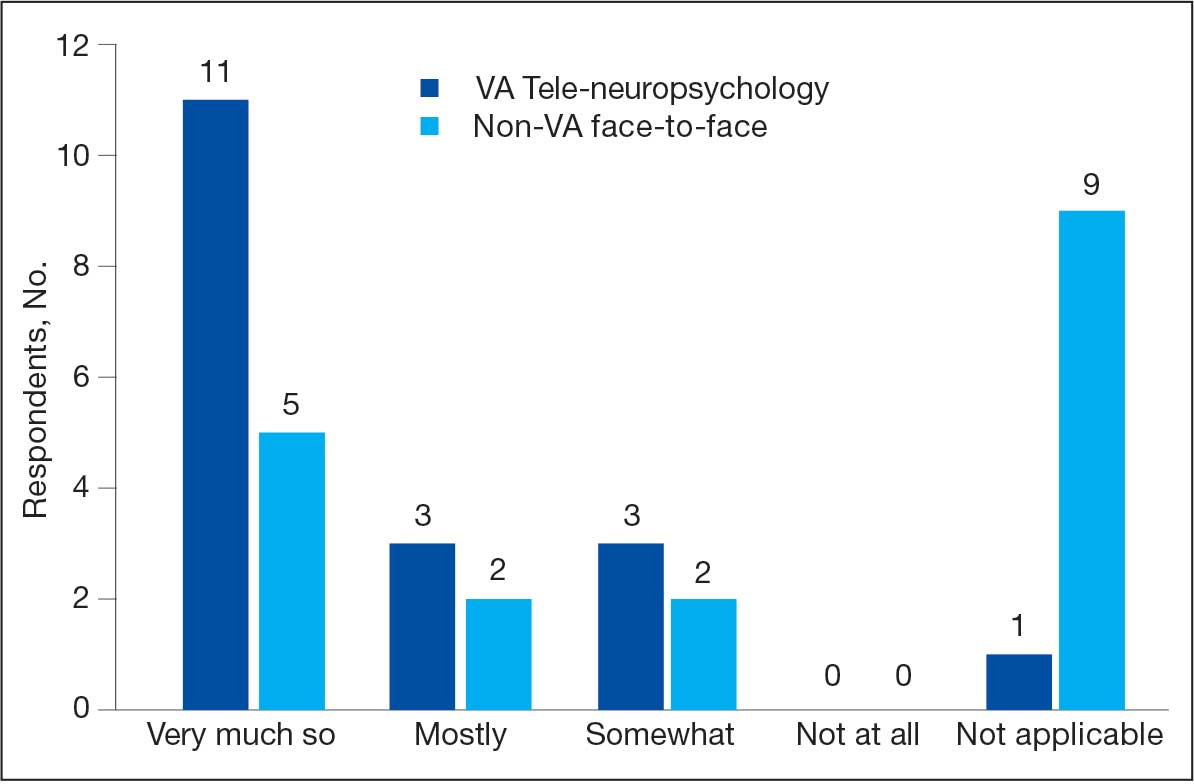

The survey ascertained information about respondents and their work setting (ie, facility type, specific work setting and location, profession, and rurality of patients). First respondents were asked whether they have referred patients to neuropsychology services in the past year. Those who had not referred patients during the past year were asked about reasons for nonreferral with an option to provide an open-ended response. Respondents who did refer were asked how they refer for neuropsychology services and about the usefulness and timeliness of both teleNP and non-VA F2F services. Respondents were asked to respond with their preference for teleNP vs non-VA F2F with an open-ended prompt. Finally, respondents were invited to share any feedback for improvement regarding teleNP services.