User login

How One GI Is Tackling His Student Debt – And the Lessons He’s Learned Along the Way

The AGA recently partnered with CommonBond (studentloans.gastro.org) to help its members save thousands by refinancing their student loans. Kevin Tin, MD, who is an AGA member, has a student loan story that can certainly offer guidance and perspective to others. Kevin earned his B.S. in health sciences from Stony Brook University and his M.D. from American University of Antigua. He completed his residency at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is currently a gastroenterology fellow.

How was your medical school experience?

My medical school experience was memorable for many reasons, particularly because I had an opportunity to study in Antigua. My time there allowed me to experience a different culture and, ultimately, a different perspective. I believe this taught me how to relate to each of my patients’ individual situations and to see things from their eyes. But, the overall cost of medical school (i.e., tuition, cost of living, medical supplies, and study resources) caught me off guard. By the time I graduated, I had amassed more than $200,000 in student loans; this was not something that I felt prepared to deal with.

How would you describe your initial experience with student loans?

What strategies have you implemented to pay off your student loans?

I’ve learned a few crucial strategies that any physician could, and should, take advantage of to save money on their student loans. First, be sure to spend responsibly while in medical school. I focused on finding free study resources and medical supplies as well as sharing materials with friends and roommates whenever possible. As I mentioned earlier, make small payments when you can; as soon as I entered residency, I started making interest payments on my loans. I wanted to contribute as much as I could, as early as I could, to get out of debt. Second, after graduation, endeavor to live frugally. Although I knew my salary would ultimately increase, I saved as much money as I could and put money toward paying off my loans. Finally, try to refinance your student loans; I refinanced mine with CommonBond. It was an unexpectedly pleasant experience: the website was extremely easy to navigate and any time I needed help, a representative was available to answer my questions. CommonBond also gave me the best rates I could find.

What were the benefits of refinancing your student loans?

What is your advice to early-career GIs who have or need to take out loans?

Do your research and do it early. While in medical school, understand what options are available to you and learn to live within your means. In your residency, plan to use a portion of your salary for paying off your student loans, even if it is only a small amount each month. This will reduce the volume of interest that will capitalize, so your loan balance doesn’t grow over time. When you start your full-time job, be financially responsible and limit your spending so you can devote additional funds to paying off your student loans.

If you would like to learn more about student loan refinancing with CommonBond, please visit studentloans.gastro.org. AGA members get a $200 cash bonus for refinancing!

Ms. Duggal is vice president of marketing for CommonBond.

The AGA recently partnered with CommonBond (studentloans.gastro.org) to help its members save thousands by refinancing their student loans. Kevin Tin, MD, who is an AGA member, has a student loan story that can certainly offer guidance and perspective to others. Kevin earned his B.S. in health sciences from Stony Brook University and his M.D. from American University of Antigua. He completed his residency at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is currently a gastroenterology fellow.

How was your medical school experience?

My medical school experience was memorable for many reasons, particularly because I had an opportunity to study in Antigua. My time there allowed me to experience a different culture and, ultimately, a different perspective. I believe this taught me how to relate to each of my patients’ individual situations and to see things from their eyes. But, the overall cost of medical school (i.e., tuition, cost of living, medical supplies, and study resources) caught me off guard. By the time I graduated, I had amassed more than $200,000 in student loans; this was not something that I felt prepared to deal with.

How would you describe your initial experience with student loans?

What strategies have you implemented to pay off your student loans?

I’ve learned a few crucial strategies that any physician could, and should, take advantage of to save money on their student loans. First, be sure to spend responsibly while in medical school. I focused on finding free study resources and medical supplies as well as sharing materials with friends and roommates whenever possible. As I mentioned earlier, make small payments when you can; as soon as I entered residency, I started making interest payments on my loans. I wanted to contribute as much as I could, as early as I could, to get out of debt. Second, after graduation, endeavor to live frugally. Although I knew my salary would ultimately increase, I saved as much money as I could and put money toward paying off my loans. Finally, try to refinance your student loans; I refinanced mine with CommonBond. It was an unexpectedly pleasant experience: the website was extremely easy to navigate and any time I needed help, a representative was available to answer my questions. CommonBond also gave me the best rates I could find.

What were the benefits of refinancing your student loans?

What is your advice to early-career GIs who have or need to take out loans?

Do your research and do it early. While in medical school, understand what options are available to you and learn to live within your means. In your residency, plan to use a portion of your salary for paying off your student loans, even if it is only a small amount each month. This will reduce the volume of interest that will capitalize, so your loan balance doesn’t grow over time. When you start your full-time job, be financially responsible and limit your spending so you can devote additional funds to paying off your student loans.

If you would like to learn more about student loan refinancing with CommonBond, please visit studentloans.gastro.org. AGA members get a $200 cash bonus for refinancing!

Ms. Duggal is vice president of marketing for CommonBond.

The AGA recently partnered with CommonBond (studentloans.gastro.org) to help its members save thousands by refinancing their student loans. Kevin Tin, MD, who is an AGA member, has a student loan story that can certainly offer guidance and perspective to others. Kevin earned his B.S. in health sciences from Stony Brook University and his M.D. from American University of Antigua. He completed his residency at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is currently a gastroenterology fellow.

How was your medical school experience?

My medical school experience was memorable for many reasons, particularly because I had an opportunity to study in Antigua. My time there allowed me to experience a different culture and, ultimately, a different perspective. I believe this taught me how to relate to each of my patients’ individual situations and to see things from their eyes. But, the overall cost of medical school (i.e., tuition, cost of living, medical supplies, and study resources) caught me off guard. By the time I graduated, I had amassed more than $200,000 in student loans; this was not something that I felt prepared to deal with.

How would you describe your initial experience with student loans?

What strategies have you implemented to pay off your student loans?

I’ve learned a few crucial strategies that any physician could, and should, take advantage of to save money on their student loans. First, be sure to spend responsibly while in medical school. I focused on finding free study resources and medical supplies as well as sharing materials with friends and roommates whenever possible. As I mentioned earlier, make small payments when you can; as soon as I entered residency, I started making interest payments on my loans. I wanted to contribute as much as I could, as early as I could, to get out of debt. Second, after graduation, endeavor to live frugally. Although I knew my salary would ultimately increase, I saved as much money as I could and put money toward paying off my loans. Finally, try to refinance your student loans; I refinanced mine with CommonBond. It was an unexpectedly pleasant experience: the website was extremely easy to navigate and any time I needed help, a representative was available to answer my questions. CommonBond also gave me the best rates I could find.

What were the benefits of refinancing your student loans?

What is your advice to early-career GIs who have or need to take out loans?

Do your research and do it early. While in medical school, understand what options are available to you and learn to live within your means. In your residency, plan to use a portion of your salary for paying off your student loans, even if it is only a small amount each month. This will reduce the volume of interest that will capitalize, so your loan balance doesn’t grow over time. When you start your full-time job, be financially responsible and limit your spending so you can devote additional funds to paying off your student loans.

If you would like to learn more about student loan refinancing with CommonBond, please visit studentloans.gastro.org. AGA members get a $200 cash bonus for refinancing!

Ms. Duggal is vice president of marketing for CommonBond.

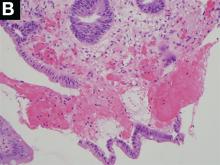

A Rare Endoscopic Clue to a Common Clinical Condition

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2017;152:492-3)

Dr. Anderson and Dr. Sweetser are in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Blazing A Trail in Medical Education

What led you to pursue a career in medical education?

Believe it or not, I pursued my path in medical education even prior to attending medical school. I was a high school teacher with a master’s in education, working during the summer of 1979 under the auspices of the Student Conservation Association at Grand Canyon National Park. Sitting on the edge of the canyon at sunset, I made the momentous decision to attend medical school, requiring attendance at a postbaccalaureate program at Columbia University. While considering medical schools, I knew that I wanted to combine my interest in education with medicine and I therefore chose to attend Case Western University School of Medicine. Since the mid-1950s, Case had been committed to innovative educational programs with a systems-based approach to the curriculum.

What do you enjoy most about working in medical education?

There are so many aspects of medical education that make work fun and rewarding. Perhaps the most rewarding is the ability to make a difference that affects the learner as well as the patients and communities that they will serve. I also enjoy the diverse experiences and opportunities in education and the ability to work with others in creative endeavors.

What are your responsibilities in a typical week?

One of the great things about a focus in education is that there never is a typical week. In the 32 years since my graduation from medical school, I have had the great fortune to fill many different roles: course director, electives director, fellowship program director, associate dean for student affairs, associate dean for undergraduate medical education, and associate dean for continuing medical education. For the past 6 years, I have been the senior associate dean for education at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, overseeing undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, continuing medical education, and the graduate school.

Over time I have had less interaction with students and residents as my administrative responsibilities have grown, but I know it is critical to maintain a presence with learners and I endeavor to do so in limited ways. Since our current priorities are in implementing a new curriculum and in planning for an accreditation visit, there are many days that are filled with meetings, planning, organizing, and writing. To me, the most precious responsibility is shaping a vision and bringing together a team to operationalize that vision in a collaborative and creative way, with learners, teachers, and administrators working together.

What are the different career options available for early-career GIs who are interested in medical education?

There are so many options in medical education for early-career gastroenterologists. For those working in private, group, or community practices, there are opportunities to precept students, residents, and fellows. For those working in an academic setting, opportunities abound. It is often a good idea to start within the division: get involved in teaching fellows in a clinical setting, or creating a new simulation experience or case workshop for fellows. There are opportunities to teach and supervise students. One of my first opportunities was in teaching in the physical diagnosis course. There are options to be involved in curriculum committees, admissions, CME, and to engage in educational initiatives at your institution.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has defined five areas of scholarship in education, and it is possible to get promoted to full professor – and even to attain academic tenure, as I have – if you fulfill the requirements for promotion at your institution. These areas include teaching, curriculum development, assessment, mentorship/advising, and leadership. There are also many ways to get involved in the AGA (http://www.gastro.org/trainees) and other organizations.1,2

Are there advanced training options available for those interested in medical education?

The AGA Academy of Educators (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-academy-of-educators)3 is a wonderful resource for networking. It has a competitive process for educational project grants as well as faculty development sessions and networking events at DDW®. There are also national leadership academies in medicine that have a focus in medical education. The Harvard Macy Institute is one such opportunity. Many medical schools have their own academies to support educators and teachers. I have been privileged to be one of the co-leaders of the AGA Future Leaders Program (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-future-leaders-program) and those with a niche interest in education can benefit and pursue related projects.4 One group was successful in publishing an educational article after completing the Future Leaders program.5 There are also several master’s programs for further education and training in educational theory. Some of these programs are available online or largely online, with limited requirements for onsite classes.

How do you go about finding a job in medical education?

First of all, you have to do your “day job.” In order to be a credible medical clinician-educator you must have clinical experience in patient care. It is important for the first years of your career to make sure that you have at least 70% clinical roles that can be reduced over time to accommodate advancing educational responsibilities. Get involved in teaching fellows. If you are in a practice, reach out to your local medical school or hospital to see how you might participate in educational programs. If you are in an academic setting, meet with the deans in education to express your interest and look for opportunities to get involved in an area of interest. If you are in academia, you have to make your work “count twice:” being productive in a scholarly way is not only important as a role model for learners, but it is important for you as a faculty member to grow and advance in your professional career.

It is always wise to think about when to say “yes” and when to say “no.” An important point is not to overextend yourself. Your reputation of completing tasks not only well, but on time, and thoroughly, is critical to your success. This includes making sure your learner evaluations are submitted on time, that you complete the administrative work in order to participate in CME programs, and that you honor your commitments by attending committee meetings.

What are the resources available to early-career GIs interested in medical education?

It is easy to find resources within your practice, your institution, or externally. The AGA has many resources available with a good start being the AGA Academy of Educators. Opportunities for creativity are numerous and with new advances in team-based learning, simulation, and interprofessional learning, there are new areas for involvement evolving all the time.6,7

Finally, pursuing a career in education is exciting, fun, and fulfilling. Having the opportunity to influence learners, which in turn will impact patient care, is an awesome privilege.

Dr. Rose is a professor of medicine and senior associate dean for education at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.

References

1. Gusic M, et al. MedEdPORTAL; 2013. Available from: http://www.mededportal.org/publication/9313.

2. Gusic ME, et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1006-11.

3. Pfeil SA, et al. Gastroenterology 2015;149(6):1309-14.

4. Cryer B, Rose S. Gastroenterology 2015;149:246-8.

5. Shah BJ, et al. Gastroenterology 2016;151(2):218-21.

6. Shah BJ, Rose S. Gastroenterology 2012;142:684-9.

7. Shah BJ, Rose S. AGA Perspectives 2012;April-May:20-21.

What led you to pursue a career in medical education?

Believe it or not, I pursued my path in medical education even prior to attending medical school. I was a high school teacher with a master’s in education, working during the summer of 1979 under the auspices of the Student Conservation Association at Grand Canyon National Park. Sitting on the edge of the canyon at sunset, I made the momentous decision to attend medical school, requiring attendance at a postbaccalaureate program at Columbia University. While considering medical schools, I knew that I wanted to combine my interest in education with medicine and I therefore chose to attend Case Western University School of Medicine. Since the mid-1950s, Case had been committed to innovative educational programs with a systems-based approach to the curriculum.

What do you enjoy most about working in medical education?

There are so many aspects of medical education that make work fun and rewarding. Perhaps the most rewarding is the ability to make a difference that affects the learner as well as the patients and communities that they will serve. I also enjoy the diverse experiences and opportunities in education and the ability to work with others in creative endeavors.

What are your responsibilities in a typical week?

One of the great things about a focus in education is that there never is a typical week. In the 32 years since my graduation from medical school, I have had the great fortune to fill many different roles: course director, electives director, fellowship program director, associate dean for student affairs, associate dean for undergraduate medical education, and associate dean for continuing medical education. For the past 6 years, I have been the senior associate dean for education at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, overseeing undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, continuing medical education, and the graduate school.

Over time I have had less interaction with students and residents as my administrative responsibilities have grown, but I know it is critical to maintain a presence with learners and I endeavor to do so in limited ways. Since our current priorities are in implementing a new curriculum and in planning for an accreditation visit, there are many days that are filled with meetings, planning, organizing, and writing. To me, the most precious responsibility is shaping a vision and bringing together a team to operationalize that vision in a collaborative and creative way, with learners, teachers, and administrators working together.

What are the different career options available for early-career GIs who are interested in medical education?

There are so many options in medical education for early-career gastroenterologists. For those working in private, group, or community practices, there are opportunities to precept students, residents, and fellows. For those working in an academic setting, opportunities abound. It is often a good idea to start within the division: get involved in teaching fellows in a clinical setting, or creating a new simulation experience or case workshop for fellows. There are opportunities to teach and supervise students. One of my first opportunities was in teaching in the physical diagnosis course. There are options to be involved in curriculum committees, admissions, CME, and to engage in educational initiatives at your institution.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has defined five areas of scholarship in education, and it is possible to get promoted to full professor – and even to attain academic tenure, as I have – if you fulfill the requirements for promotion at your institution. These areas include teaching, curriculum development, assessment, mentorship/advising, and leadership. There are also many ways to get involved in the AGA (http://www.gastro.org/trainees) and other organizations.1,2

Are there advanced training options available for those interested in medical education?

The AGA Academy of Educators (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-academy-of-educators)3 is a wonderful resource for networking. It has a competitive process for educational project grants as well as faculty development sessions and networking events at DDW®. There are also national leadership academies in medicine that have a focus in medical education. The Harvard Macy Institute is one such opportunity. Many medical schools have their own academies to support educators and teachers. I have been privileged to be one of the co-leaders of the AGA Future Leaders Program (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-future-leaders-program) and those with a niche interest in education can benefit and pursue related projects.4 One group was successful in publishing an educational article after completing the Future Leaders program.5 There are also several master’s programs for further education and training in educational theory. Some of these programs are available online or largely online, with limited requirements for onsite classes.

How do you go about finding a job in medical education?

First of all, you have to do your “day job.” In order to be a credible medical clinician-educator you must have clinical experience in patient care. It is important for the first years of your career to make sure that you have at least 70% clinical roles that can be reduced over time to accommodate advancing educational responsibilities. Get involved in teaching fellows. If you are in a practice, reach out to your local medical school or hospital to see how you might participate in educational programs. If you are in an academic setting, meet with the deans in education to express your interest and look for opportunities to get involved in an area of interest. If you are in academia, you have to make your work “count twice:” being productive in a scholarly way is not only important as a role model for learners, but it is important for you as a faculty member to grow and advance in your professional career.

It is always wise to think about when to say “yes” and when to say “no.” An important point is not to overextend yourself. Your reputation of completing tasks not only well, but on time, and thoroughly, is critical to your success. This includes making sure your learner evaluations are submitted on time, that you complete the administrative work in order to participate in CME programs, and that you honor your commitments by attending committee meetings.

What are the resources available to early-career GIs interested in medical education?

It is easy to find resources within your practice, your institution, or externally. The AGA has many resources available with a good start being the AGA Academy of Educators. Opportunities for creativity are numerous and with new advances in team-based learning, simulation, and interprofessional learning, there are new areas for involvement evolving all the time.6,7

Finally, pursuing a career in education is exciting, fun, and fulfilling. Having the opportunity to influence learners, which in turn will impact patient care, is an awesome privilege.

Dr. Rose is a professor of medicine and senior associate dean for education at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.

References

1. Gusic M, et al. MedEdPORTAL; 2013. Available from: http://www.mededportal.org/publication/9313.

2. Gusic ME, et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1006-11.

3. Pfeil SA, et al. Gastroenterology 2015;149(6):1309-14.

4. Cryer B, Rose S. Gastroenterology 2015;149:246-8.

5. Shah BJ, et al. Gastroenterology 2016;151(2):218-21.

6. Shah BJ, Rose S. Gastroenterology 2012;142:684-9.

7. Shah BJ, Rose S. AGA Perspectives 2012;April-May:20-21.

What led you to pursue a career in medical education?

Believe it or not, I pursued my path in medical education even prior to attending medical school. I was a high school teacher with a master’s in education, working during the summer of 1979 under the auspices of the Student Conservation Association at Grand Canyon National Park. Sitting on the edge of the canyon at sunset, I made the momentous decision to attend medical school, requiring attendance at a postbaccalaureate program at Columbia University. While considering medical schools, I knew that I wanted to combine my interest in education with medicine and I therefore chose to attend Case Western University School of Medicine. Since the mid-1950s, Case had been committed to innovative educational programs with a systems-based approach to the curriculum.

What do you enjoy most about working in medical education?

There are so many aspects of medical education that make work fun and rewarding. Perhaps the most rewarding is the ability to make a difference that affects the learner as well as the patients and communities that they will serve. I also enjoy the diverse experiences and opportunities in education and the ability to work with others in creative endeavors.

What are your responsibilities in a typical week?

One of the great things about a focus in education is that there never is a typical week. In the 32 years since my graduation from medical school, I have had the great fortune to fill many different roles: course director, electives director, fellowship program director, associate dean for student affairs, associate dean for undergraduate medical education, and associate dean for continuing medical education. For the past 6 years, I have been the senior associate dean for education at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, overseeing undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, continuing medical education, and the graduate school.

Over time I have had less interaction with students and residents as my administrative responsibilities have grown, but I know it is critical to maintain a presence with learners and I endeavor to do so in limited ways. Since our current priorities are in implementing a new curriculum and in planning for an accreditation visit, there are many days that are filled with meetings, planning, organizing, and writing. To me, the most precious responsibility is shaping a vision and bringing together a team to operationalize that vision in a collaborative and creative way, with learners, teachers, and administrators working together.

What are the different career options available for early-career GIs who are interested in medical education?

There are so many options in medical education for early-career gastroenterologists. For those working in private, group, or community practices, there are opportunities to precept students, residents, and fellows. For those working in an academic setting, opportunities abound. It is often a good idea to start within the division: get involved in teaching fellows in a clinical setting, or creating a new simulation experience or case workshop for fellows. There are opportunities to teach and supervise students. One of my first opportunities was in teaching in the physical diagnosis course. There are options to be involved in curriculum committees, admissions, CME, and to engage in educational initiatives at your institution.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has defined five areas of scholarship in education, and it is possible to get promoted to full professor – and even to attain academic tenure, as I have – if you fulfill the requirements for promotion at your institution. These areas include teaching, curriculum development, assessment, mentorship/advising, and leadership. There are also many ways to get involved in the AGA (http://www.gastro.org/trainees) and other organizations.1,2

Are there advanced training options available for those interested in medical education?

The AGA Academy of Educators (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-academy-of-educators)3 is a wonderful resource for networking. It has a competitive process for educational project grants as well as faculty development sessions and networking events at DDW®. There are also national leadership academies in medicine that have a focus in medical education. The Harvard Macy Institute is one such opportunity. Many medical schools have their own academies to support educators and teachers. I have been privileged to be one of the co-leaders of the AGA Future Leaders Program (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-future-leaders-program) and those with a niche interest in education can benefit and pursue related projects.4 One group was successful in publishing an educational article after completing the Future Leaders program.5 There are also several master’s programs for further education and training in educational theory. Some of these programs are available online or largely online, with limited requirements for onsite classes.

How do you go about finding a job in medical education?

First of all, you have to do your “day job.” In order to be a credible medical clinician-educator you must have clinical experience in patient care. It is important for the first years of your career to make sure that you have at least 70% clinical roles that can be reduced over time to accommodate advancing educational responsibilities. Get involved in teaching fellows. If you are in a practice, reach out to your local medical school or hospital to see how you might participate in educational programs. If you are in an academic setting, meet with the deans in education to express your interest and look for opportunities to get involved in an area of interest. If you are in academia, you have to make your work “count twice:” being productive in a scholarly way is not only important as a role model for learners, but it is important for you as a faculty member to grow and advance in your professional career.

It is always wise to think about when to say “yes” and when to say “no.” An important point is not to overextend yourself. Your reputation of completing tasks not only well, but on time, and thoroughly, is critical to your success. This includes making sure your learner evaluations are submitted on time, that you complete the administrative work in order to participate in CME programs, and that you honor your commitments by attending committee meetings.

What are the resources available to early-career GIs interested in medical education?

It is easy to find resources within your practice, your institution, or externally. The AGA has many resources available with a good start being the AGA Academy of Educators. Opportunities for creativity are numerous and with new advances in team-based learning, simulation, and interprofessional learning, there are new areas for involvement evolving all the time.6,7

Finally, pursuing a career in education is exciting, fun, and fulfilling. Having the opportunity to influence learners, which in turn will impact patient care, is an awesome privilege.

Dr. Rose is a professor of medicine and senior associate dean for education at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.

References

1. Gusic M, et al. MedEdPORTAL; 2013. Available from: http://www.mededportal.org/publication/9313.

2. Gusic ME, et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1006-11.

3. Pfeil SA, et al. Gastroenterology 2015;149(6):1309-14.

4. Cryer B, Rose S. Gastroenterology 2015;149:246-8.

5. Shah BJ, et al. Gastroenterology 2016;151(2):218-21.

6. Shah BJ, Rose S. Gastroenterology 2012;142:684-9.

7. Shah BJ, Rose S. AGA Perspectives 2012;April-May:20-21.

Legal Issues for the Gastroenterologist: Part I

An unfortunate fact for many physicians practicing in the United States is that they will contend with medical malpractice suits at some point in their careers. While data specific to gastroenterology malpractice claims is difficult to find,1 the Physician Insurers Association of America has reported that out of the 28 specialty fields of medicine analyzed from 1985 to 2004, gastroenterology ranked 21st in the number of claims reported2, representing about 2% of the total overall number of claims.

In 2017, JAMA Internal Medicine published additional statistical findings related to medical malpractice claims.4JAMA reported that the rate of claims paid on behalf of all physicians had declined by 55.7% between 1992 and 2014; from 20.1 per 1,000 physicians to 8.9 per 1000 physicians.4 The mean payment for the 280,368 claims reported in the National Practitioner Data Bank during this time frame was $329,565 (adjusted to 2014 dollars).4

Professional liability

Patients can allege or establish malpractice liability against a doctor based on a number of things; we will discuss a few of the most common types of liability, offer suggestions as to how you might minimize your risk of being sued, and how best to cope when you are sued.

Negligence: One of the most common theories you may be sued under is negligence. To state a negligence claim against a physician, a plaintiff must show that the doctor owed the patient a duty recognized by law, that the physician breached that duty, that the alleged breach resulted in injury to the patient, and that the patient sustained legally recognized damages as a result. In a lawsuit brought on the basis of claimed medical negligence, a patient claims that a physician, in the course of rendering treatment, failed to meet the applicable standard of care.

Contractual liability of doctor to patient: Physicians and patients can enter into express written contracts regarding the care provided. These contracts can include various treatment plans, the likelihood of success, and even the physician’s promise to cure. Traditionally, courts have respected a physician’s freedom to contract as he or she chooses. However, once a contract is formed, a plaintiff may have a cause of action for breach of contract if the outcome of the treatment is not what was promised.

Minimizing risk

Another opportunity to decrease your chances of being sued is to keep informed about recent developments in your field. Make a point to read pertinent literature, attend seminars, and do whatever is necessary to stay aware of, and to incorporate into your practice, current methods of treatment and diagnosis.

Physicians should also be cognizant of contractual liability. When discussing treatment, never guarantee results. Additionally, once a physician-patient relationship is established, you cannot withdraw from the relationship without providing adequate notice to the patient in time to obtain alternative care. Terminating the relationship without such is called abandonment, and can result in professional discipline and civil liability.

Conclusion

Before a lawsuit, and as a regular part of your practice, it is important that you thoroughly and legibly document all aspects of care provided, stay current with medical advances, and take the time to create a relationship with your patients involving quality communication. It is impossible for us to provide you with enough information to adequately prepare you for the day on which you may be sued. We nevertheless hope that following the aforementioned suggestions will be of some help.

References

1. Medical Malpractice Claims and Risk Management in Gastroenterology and Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2017. <www.asge.org>.

2. Physician Insurers Association of America. PIAA Claim Trend Analysis: Gastroenterology, iv. Lawrenceville, N.J.: PIAA, 2004. <http://www.piaa.us>.

3. Kane C., Policy Research Perspective: Medical Liability Claim Frequency: 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians, American Medical Association, 2010.

4. Schaffer A.C., et al. JAMA Internal Med. 2017;177(5):710-8.

5. Dodge A.M. Wilsonville, Ore. Book Partners, Inc. 2001.

An unfortunate fact for many physicians practicing in the United States is that they will contend with medical malpractice suits at some point in their careers. While data specific to gastroenterology malpractice claims is difficult to find,1 the Physician Insurers Association of America has reported that out of the 28 specialty fields of medicine analyzed from 1985 to 2004, gastroenterology ranked 21st in the number of claims reported2, representing about 2% of the total overall number of claims.

In 2017, JAMA Internal Medicine published additional statistical findings related to medical malpractice claims.4JAMA reported that the rate of claims paid on behalf of all physicians had declined by 55.7% between 1992 and 2014; from 20.1 per 1,000 physicians to 8.9 per 1000 physicians.4 The mean payment for the 280,368 claims reported in the National Practitioner Data Bank during this time frame was $329,565 (adjusted to 2014 dollars).4

Professional liability

Patients can allege or establish malpractice liability against a doctor based on a number of things; we will discuss a few of the most common types of liability, offer suggestions as to how you might minimize your risk of being sued, and how best to cope when you are sued.

Negligence: One of the most common theories you may be sued under is negligence. To state a negligence claim against a physician, a plaintiff must show that the doctor owed the patient a duty recognized by law, that the physician breached that duty, that the alleged breach resulted in injury to the patient, and that the patient sustained legally recognized damages as a result. In a lawsuit brought on the basis of claimed medical negligence, a patient claims that a physician, in the course of rendering treatment, failed to meet the applicable standard of care.

Contractual liability of doctor to patient: Physicians and patients can enter into express written contracts regarding the care provided. These contracts can include various treatment plans, the likelihood of success, and even the physician’s promise to cure. Traditionally, courts have respected a physician’s freedom to contract as he or she chooses. However, once a contract is formed, a plaintiff may have a cause of action for breach of contract if the outcome of the treatment is not what was promised.

Minimizing risk

Another opportunity to decrease your chances of being sued is to keep informed about recent developments in your field. Make a point to read pertinent literature, attend seminars, and do whatever is necessary to stay aware of, and to incorporate into your practice, current methods of treatment and diagnosis.

Physicians should also be cognizant of contractual liability. When discussing treatment, never guarantee results. Additionally, once a physician-patient relationship is established, you cannot withdraw from the relationship without providing adequate notice to the patient in time to obtain alternative care. Terminating the relationship without such is called abandonment, and can result in professional discipline and civil liability.

Conclusion

Before a lawsuit, and as a regular part of your practice, it is important that you thoroughly and legibly document all aspects of care provided, stay current with medical advances, and take the time to create a relationship with your patients involving quality communication. It is impossible for us to provide you with enough information to adequately prepare you for the day on which you may be sued. We nevertheless hope that following the aforementioned suggestions will be of some help.

References

1. Medical Malpractice Claims and Risk Management in Gastroenterology and Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2017. <www.asge.org>.

2. Physician Insurers Association of America. PIAA Claim Trend Analysis: Gastroenterology, iv. Lawrenceville, N.J.: PIAA, 2004. <http://www.piaa.us>.

3. Kane C., Policy Research Perspective: Medical Liability Claim Frequency: 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians, American Medical Association, 2010.

4. Schaffer A.C., et al. JAMA Internal Med. 2017;177(5):710-8.

5. Dodge A.M. Wilsonville, Ore. Book Partners, Inc. 2001.

An unfortunate fact for many physicians practicing in the United States is that they will contend with medical malpractice suits at some point in their careers. While data specific to gastroenterology malpractice claims is difficult to find,1 the Physician Insurers Association of America has reported that out of the 28 specialty fields of medicine analyzed from 1985 to 2004, gastroenterology ranked 21st in the number of claims reported2, representing about 2% of the total overall number of claims.

In 2017, JAMA Internal Medicine published additional statistical findings related to medical malpractice claims.4JAMA reported that the rate of claims paid on behalf of all physicians had declined by 55.7% between 1992 and 2014; from 20.1 per 1,000 physicians to 8.9 per 1000 physicians.4 The mean payment for the 280,368 claims reported in the National Practitioner Data Bank during this time frame was $329,565 (adjusted to 2014 dollars).4

Professional liability

Patients can allege or establish malpractice liability against a doctor based on a number of things; we will discuss a few of the most common types of liability, offer suggestions as to how you might minimize your risk of being sued, and how best to cope when you are sued.

Negligence: One of the most common theories you may be sued under is negligence. To state a negligence claim against a physician, a plaintiff must show that the doctor owed the patient a duty recognized by law, that the physician breached that duty, that the alleged breach resulted in injury to the patient, and that the patient sustained legally recognized damages as a result. In a lawsuit brought on the basis of claimed medical negligence, a patient claims that a physician, in the course of rendering treatment, failed to meet the applicable standard of care.

Contractual liability of doctor to patient: Physicians and patients can enter into express written contracts regarding the care provided. These contracts can include various treatment plans, the likelihood of success, and even the physician’s promise to cure. Traditionally, courts have respected a physician’s freedom to contract as he or she chooses. However, once a contract is formed, a plaintiff may have a cause of action for breach of contract if the outcome of the treatment is not what was promised.

Minimizing risk

Another opportunity to decrease your chances of being sued is to keep informed about recent developments in your field. Make a point to read pertinent literature, attend seminars, and do whatever is necessary to stay aware of, and to incorporate into your practice, current methods of treatment and diagnosis.

Physicians should also be cognizant of contractual liability. When discussing treatment, never guarantee results. Additionally, once a physician-patient relationship is established, you cannot withdraw from the relationship without providing adequate notice to the patient in time to obtain alternative care. Terminating the relationship without such is called abandonment, and can result in professional discipline and civil liability.

Conclusion

Before a lawsuit, and as a regular part of your practice, it is important that you thoroughly and legibly document all aspects of care provided, stay current with medical advances, and take the time to create a relationship with your patients involving quality communication. It is impossible for us to provide you with enough information to adequately prepare you for the day on which you may be sued. We nevertheless hope that following the aforementioned suggestions will be of some help.

References

1. Medical Malpractice Claims and Risk Management in Gastroenterology and Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2017. <www.asge.org>.

2. Physician Insurers Association of America. PIAA Claim Trend Analysis: Gastroenterology, iv. Lawrenceville, N.J.: PIAA, 2004. <http://www.piaa.us>.

3. Kane C., Policy Research Perspective: Medical Liability Claim Frequency: 2007-2008 Snapshot of Physicians, American Medical Association, 2010.

4. Schaffer A.C., et al. JAMA Internal Med. 2017;177(5):710-8.

5. Dodge A.M. Wilsonville, Ore. Book Partners, Inc. 2001.

AGA’s 2017 Women’s Leadership Conference: Developing Skills in Advocacy and Personal Branding

The 2017 AGA Women’s Leadership Conference brought together 38 women from across the United States and Mexico for an inspiring and productive meeting. The group included 21 early-career and 17 experienced track women in GI. Among the attendees were 3 PhDs, 9 private practitioners, 1 pediatric gastroenterologist, and 25 academic gastroenterologists. We were particularly fortunate to benefit from the strong representation of AGA leadership, including Marcia Cruz-Correa, MD, PhD, AGAF (At-Large Councillor) and Deborah Proctor, MD, AGAF (Education and Training Councillor), as well as Ellen Zimmermann, MD, AGAF (Chair of the Women’s Committee) and Sheila Crowe, MD, AGAF (President, AGA Institute Governing Board).

The program included lively problem-solving sessions and a passionate discussion about negotiating skills. The latter topic was of particular interest given data indicating that pay inequity still exists. The group engaged in animated conversation about advocating for fair pay in academics and private practice.

In addition to strong mentorship, the early-career group discussed the importance of discerning one’s own individual passions. Identifying professional and personal ambitions can allow us to focus our energy and activities. We were encouraged to write down one personal and one professional goal on an annual basis. These goals can offer clarity for a range of decisions such as when to accept new responsibilities and how to structure activities and manage time at work and at home.

The AGA leaders in attendance shared inspiring stories of their own paths to leadership. These paths were not linear and it was reassuring to discover common themes of finding and developing personal strengths, identifying passions, and building areas of expertise. We learned, how once identified, strengths and passions can be connected to areas of need within a home institution or an organization such as the AGA. Dr. Zimmermann offered moving commentary about her own journey as a clinician, scientist, and mother. She encouraged those in attendance with small children to take the time to be present at home, knowing that there will be opportunities to assume leadership roles in the future. Of course, for others, the time to assume leadership roles may be now, and the Women’s Leadership Conference offered the chance to network and forge new connections within the AGA.

The second new topic was addressed in a powerful session on personal branding by Dr. Cruz-Correa. Personal branding involves identifying and communicating who one is to the world in a memorable way. Dr. Cruz-Correa emphasized that creating a personal brand is essential for leadership and critically important for advancing one’s career. Developing a personal brand should include crafting a statement of one to two sentences that considers both one’s values and the target audience. The statement should be memorable and punchy with an emphasis on solutions. Branding expands beyond indicating an area of interest; a personal brand should demonstrate consistent delivery of high-quality work. An example of a personal brand could be “Physician, fitness fanatic, and fearless foodie empowering patients and colleagues to lead healthy fulfilling lives.” An alternative might be: “Physician, teacher, empowering colleagues, advocating for patients, and evolving with the times.” Creating a personal brand that highlights action and solutions emphasizes a theme of the meeting: Follow-through after accepting responsibilities is critically important.

In summary, the 2017 AGA Women’s Leadership Conference provided an invigorating curriculum as well as many opportunities for establishing new networks of strong women in our field. Participants were charged with bringing some of the content back home, and we’re already receiving reports about these local events. Be sure to look for future content from the AGA at http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/womens-committee.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Garman and Dr. Alaparthi would like to offer heartfelt thanks to the AGA as well as to Celena NuQuay and Carol Brown for their support.

Dr. Garman is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. Dr. Alaparthi is managing partner of Gastroenterology Center of Connecticut and assistant clinical professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine, Conn., and Frank Netter School of Medicine, Conn.

The 2017 AGA Women’s Leadership Conference brought together 38 women from across the United States and Mexico for an inspiring and productive meeting. The group included 21 early-career and 17 experienced track women in GI. Among the attendees were 3 PhDs, 9 private practitioners, 1 pediatric gastroenterologist, and 25 academic gastroenterologists. We were particularly fortunate to benefit from the strong representation of AGA leadership, including Marcia Cruz-Correa, MD, PhD, AGAF (At-Large Councillor) and Deborah Proctor, MD, AGAF (Education and Training Councillor), as well as Ellen Zimmermann, MD, AGAF (Chair of the Women’s Committee) and Sheila Crowe, MD, AGAF (President, AGA Institute Governing Board).

The program included lively problem-solving sessions and a passionate discussion about negotiating skills. The latter topic was of particular interest given data indicating that pay inequity still exists. The group engaged in animated conversation about advocating for fair pay in academics and private practice.

In addition to strong mentorship, the early-career group discussed the importance of discerning one’s own individual passions. Identifying professional and personal ambitions can allow us to focus our energy and activities. We were encouraged to write down one personal and one professional goal on an annual basis. These goals can offer clarity for a range of decisions such as when to accept new responsibilities and how to structure activities and manage time at work and at home.

The AGA leaders in attendance shared inspiring stories of their own paths to leadership. These paths were not linear and it was reassuring to discover common themes of finding and developing personal strengths, identifying passions, and building areas of expertise. We learned, how once identified, strengths and passions can be connected to areas of need within a home institution or an organization such as the AGA. Dr. Zimmermann offered moving commentary about her own journey as a clinician, scientist, and mother. She encouraged those in attendance with small children to take the time to be present at home, knowing that there will be opportunities to assume leadership roles in the future. Of course, for others, the time to assume leadership roles may be now, and the Women’s Leadership Conference offered the chance to network and forge new connections within the AGA.

The second new topic was addressed in a powerful session on personal branding by Dr. Cruz-Correa. Personal branding involves identifying and communicating who one is to the world in a memorable way. Dr. Cruz-Correa emphasized that creating a personal brand is essential for leadership and critically important for advancing one’s career. Developing a personal brand should include crafting a statement of one to two sentences that considers both one’s values and the target audience. The statement should be memorable and punchy with an emphasis on solutions. Branding expands beyond indicating an area of interest; a personal brand should demonstrate consistent delivery of high-quality work. An example of a personal brand could be “Physician, fitness fanatic, and fearless foodie empowering patients and colleagues to lead healthy fulfilling lives.” An alternative might be: “Physician, teacher, empowering colleagues, advocating for patients, and evolving with the times.” Creating a personal brand that highlights action and solutions emphasizes a theme of the meeting: Follow-through after accepting responsibilities is critically important.

In summary, the 2017 AGA Women’s Leadership Conference provided an invigorating curriculum as well as many opportunities for establishing new networks of strong women in our field. Participants were charged with bringing some of the content back home, and we’re already receiving reports about these local events. Be sure to look for future content from the AGA at http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/womens-committee.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Garman and Dr. Alaparthi would like to offer heartfelt thanks to the AGA as well as to Celena NuQuay and Carol Brown for their support.

Dr. Garman is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. Dr. Alaparthi is managing partner of Gastroenterology Center of Connecticut and assistant clinical professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine, Conn., and Frank Netter School of Medicine, Conn.

The 2017 AGA Women’s Leadership Conference brought together 38 women from across the United States and Mexico for an inspiring and productive meeting. The group included 21 early-career and 17 experienced track women in GI. Among the attendees were 3 PhDs, 9 private practitioners, 1 pediatric gastroenterologist, and 25 academic gastroenterologists. We were particularly fortunate to benefit from the strong representation of AGA leadership, including Marcia Cruz-Correa, MD, PhD, AGAF (At-Large Councillor) and Deborah Proctor, MD, AGAF (Education and Training Councillor), as well as Ellen Zimmermann, MD, AGAF (Chair of the Women’s Committee) and Sheila Crowe, MD, AGAF (President, AGA Institute Governing Board).

The program included lively problem-solving sessions and a passionate discussion about negotiating skills. The latter topic was of particular interest given data indicating that pay inequity still exists. The group engaged in animated conversation about advocating for fair pay in academics and private practice.

In addition to strong mentorship, the early-career group discussed the importance of discerning one’s own individual passions. Identifying professional and personal ambitions can allow us to focus our energy and activities. We were encouraged to write down one personal and one professional goal on an annual basis. These goals can offer clarity for a range of decisions such as when to accept new responsibilities and how to structure activities and manage time at work and at home.

The AGA leaders in attendance shared inspiring stories of their own paths to leadership. These paths were not linear and it was reassuring to discover common themes of finding and developing personal strengths, identifying passions, and building areas of expertise. We learned, how once identified, strengths and passions can be connected to areas of need within a home institution or an organization such as the AGA. Dr. Zimmermann offered moving commentary about her own journey as a clinician, scientist, and mother. She encouraged those in attendance with small children to take the time to be present at home, knowing that there will be opportunities to assume leadership roles in the future. Of course, for others, the time to assume leadership roles may be now, and the Women’s Leadership Conference offered the chance to network and forge new connections within the AGA.

The second new topic was addressed in a powerful session on personal branding by Dr. Cruz-Correa. Personal branding involves identifying and communicating who one is to the world in a memorable way. Dr. Cruz-Correa emphasized that creating a personal brand is essential for leadership and critically important for advancing one’s career. Developing a personal brand should include crafting a statement of one to two sentences that considers both one’s values and the target audience. The statement should be memorable and punchy with an emphasis on solutions. Branding expands beyond indicating an area of interest; a personal brand should demonstrate consistent delivery of high-quality work. An example of a personal brand could be “Physician, fitness fanatic, and fearless foodie empowering patients and colleagues to lead healthy fulfilling lives.” An alternative might be: “Physician, teacher, empowering colleagues, advocating for patients, and evolving with the times.” Creating a personal brand that highlights action and solutions emphasizes a theme of the meeting: Follow-through after accepting responsibilities is critically important.

In summary, the 2017 AGA Women’s Leadership Conference provided an invigorating curriculum as well as many opportunities for establishing new networks of strong women in our field. Participants were charged with bringing some of the content back home, and we’re already receiving reports about these local events. Be sure to look for future content from the AGA at http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/womens-committee.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Garman and Dr. Alaparthi would like to offer heartfelt thanks to the AGA as well as to Celena NuQuay and Carol Brown for their support.

Dr. Garman is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. Dr. Alaparthi is managing partner of Gastroenterology Center of Connecticut and assistant clinical professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine, Conn., and Frank Netter School of Medicine, Conn.

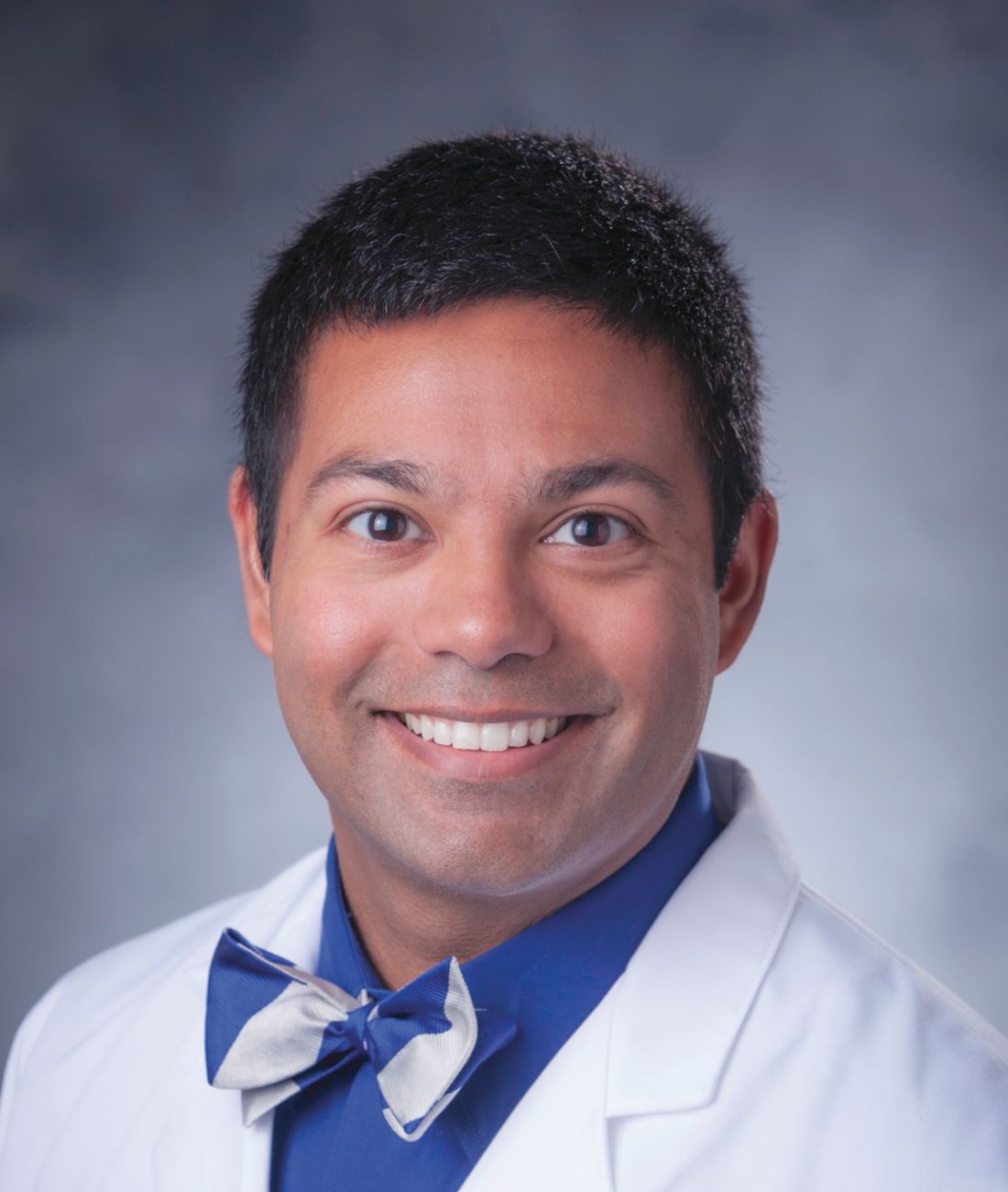

Reflux Diagnostics: Modern Techniques and Future Directions

Introduction

Chronic esophageal symptoms attributed to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are common presenting symptoms in gastroenterology, leading to high healthcare costs and adverse quality of life globally.1,2 The clinical diagnosis of GERD hinges on the presence of “troublesome” compatible typical symptoms (heartburn, acid regurgitation) or evidence of mucosal injury on endoscopy (esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic stricture).3 With the growing availability of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), patients and clinicians often utilize an empiric therapeutic trial of PPI as an initial test, with symptom improvement in the absence of alarm symptoms indicating a high likelihood of GERD.4 A meta-analysis of studies that used objective measures of GERD (in this case, 24-hour pH monitoring) showed that the “PPI test” has a sensitivity of 78%, but a specificity of only 54%, as a diagnostic approach to GERD symptoms.5 Apart from noncardiac chest pain, the diagnostic yield is even lower for atypical and extra-esophageal symptoms such as cough or laryngeal symptoms.6

The “nuts and bolts” of reflux testing

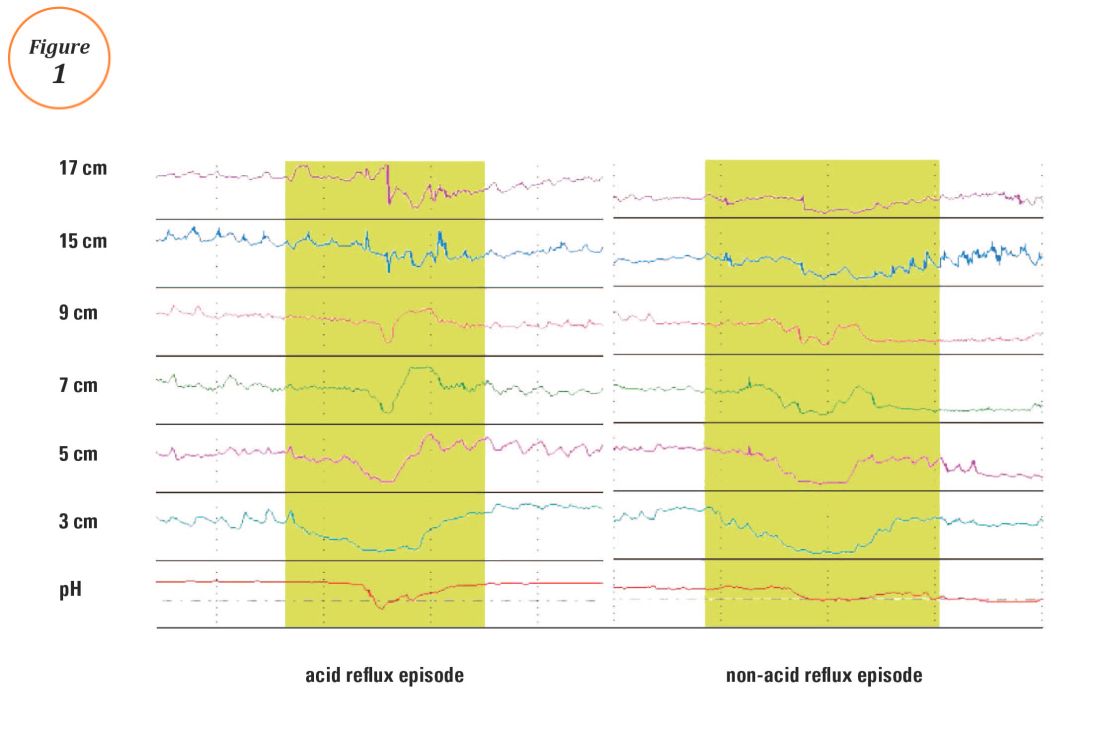

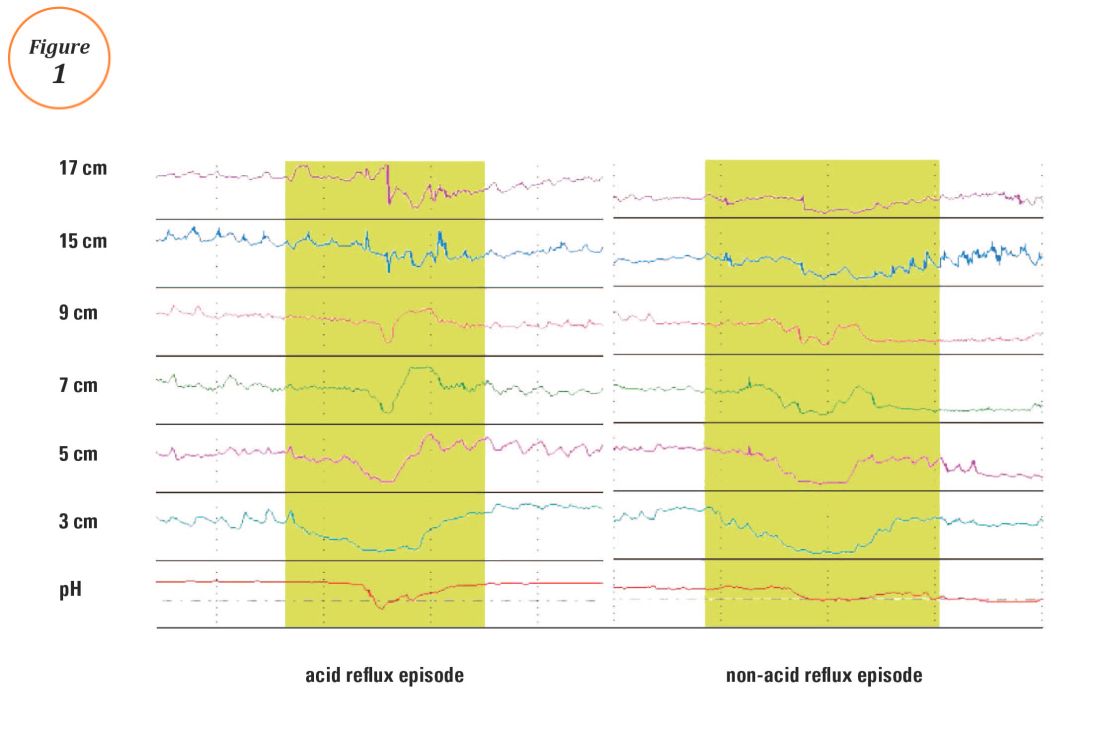

Ambulatory reflux testing assesses esophageal reflux burden and symptom-reflux association (SRA). Individual reflux events are identified as either a drop in esophageal pH to less than 4 (acid reflux events), or a sharp decrease in esophageal impedance measurements in a retrograde fashion (impedance-detected reflux events), with subsequent recovery to the baseline in each instance. Ambulatory reflux testing affords insight into three areas: 1) measurement of esophageal acid exposure time (AET); the cumulative time duration when distal esophageal pH is less than 4 at the recording site, reported as a percentage of the recording period; 2) measurement of the number of reflux events both acidic (from pH monitoring) and weakly acidic/alkaline (from impedance monitoring); and 3) quantitative evaluation of the association between reported symptom episodes and reflux events.

The SI and SAP can be calculated individually for acid-detected reflux events and for impedance-detected reflux events. Since reflux events are better detected with impedance, combined pH-impedance testing increases the yield of detecting positive SRA, especially when performed off PPI therapy.16,17 Because these indices are heavily reliant on patient reporting of symptom episodes, SRA can be overinterpreted;18 positive associations are more clinically useful than negative results in the evaluation of symptoms attributed to GERD.19 Despite these concerns, the two most consistent predictors of symptomatic outcome with antireflux therapy on pH-impedance testing are abnormal AET and positive SAP with impedance-detected reflux events.17

Testing on or off PPI?

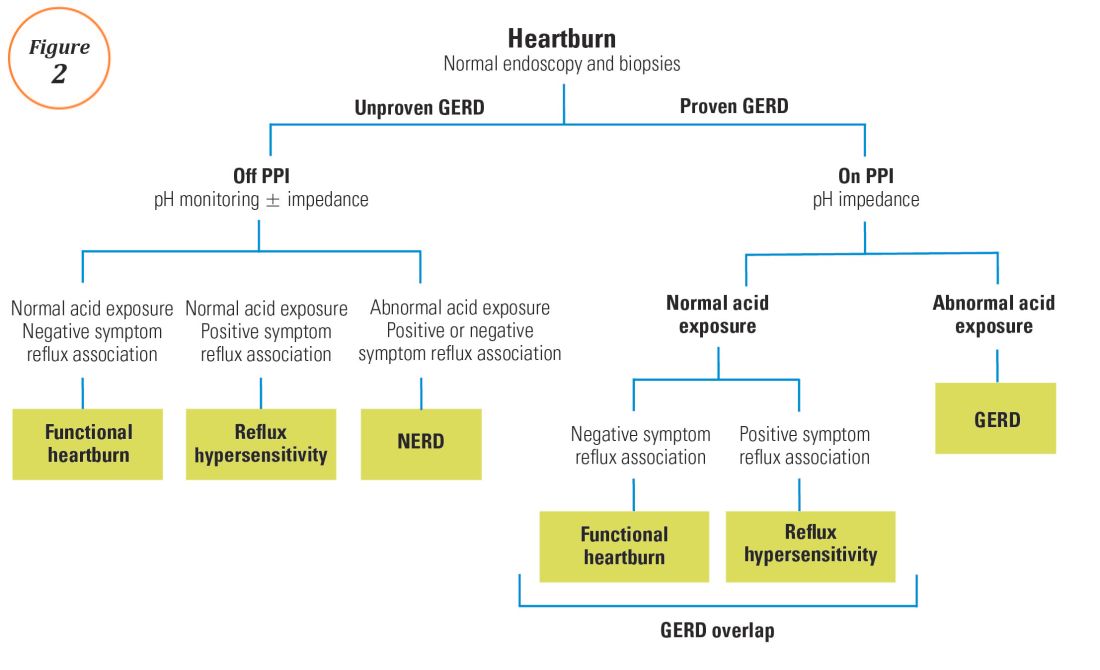

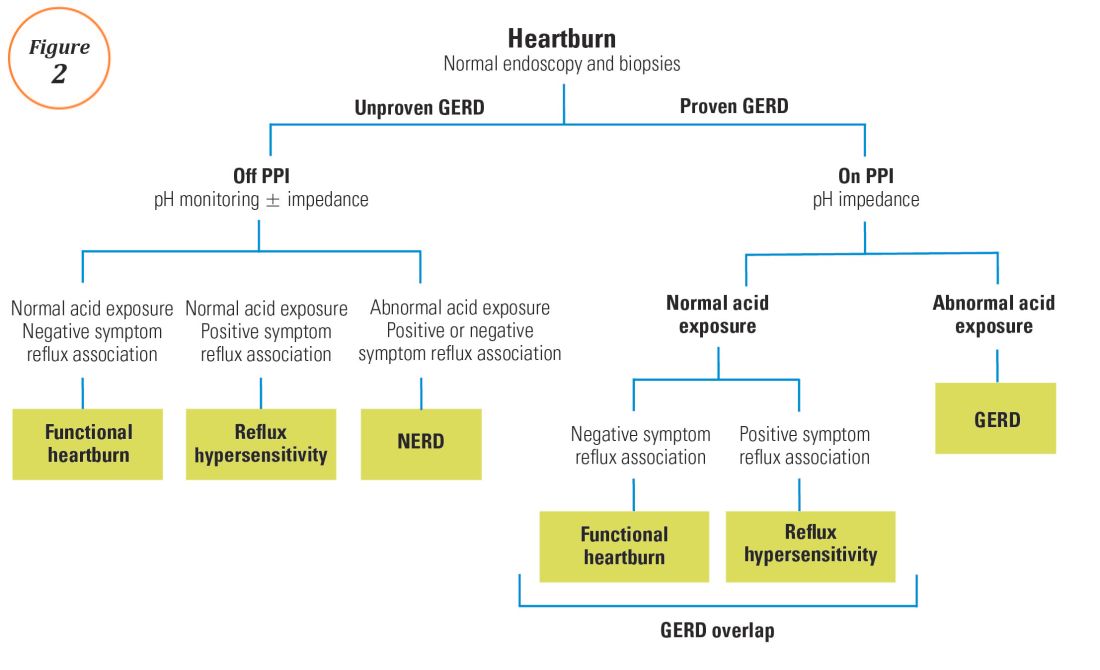

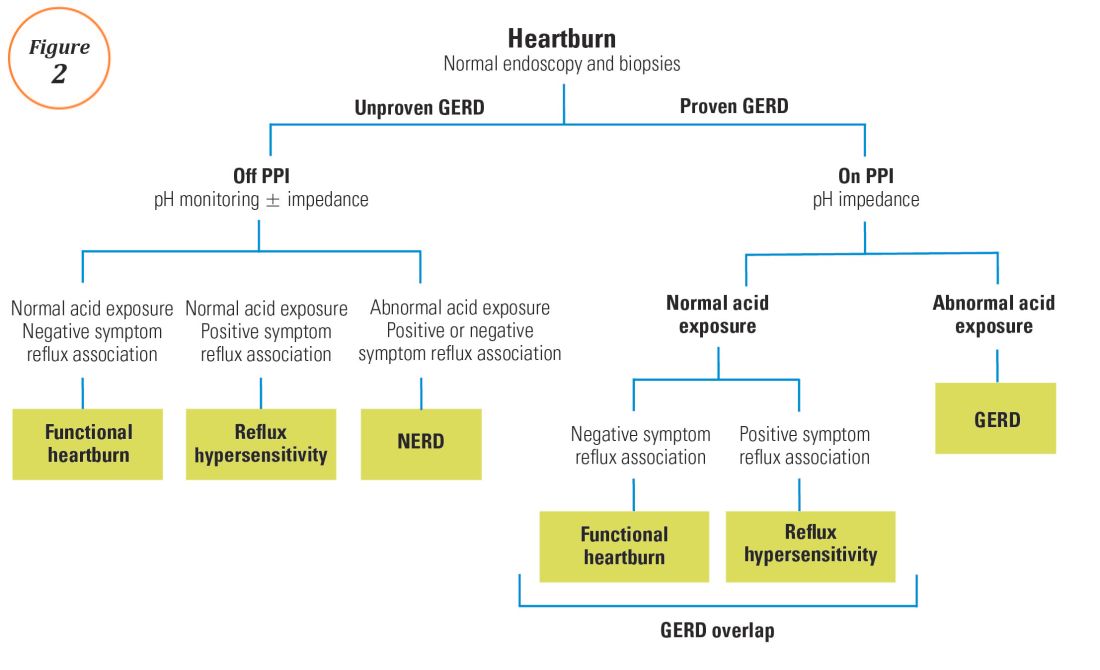

For symptoms attributable to GERD that persist despite properly administered PPI therapy, the 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines suggest upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies for typical symptoms and appropriate referrals for atypical symptoms.24 However, if these evaluations are unremarkable, reflux monitoring is recommended, with PPI status for testing guided by the pre-test probability of GERD: with a low pre-test probability of GERD, reflux testing is best performed off PPI with either pH or combined pH-impedance testing. In contrast, with a high pre-test probability of GERD, testing is best performed on PPI with combined pH-impedance testing. A similar concept is proposed in the Rome IV approach (Figure 2)23 and on GERD consensus guidelines:7 when heartburn or chest pain persists despite PPI therapy and endoscopy and esophageal biopsies are normal, evidence for GERD (past esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic stricture, or prior positive reflux testing) prompts pH-impedance monitoring on PPI therapy (i.e., proven GERD). Those without this evidence for proven GERD (i.e., unproven GERD) are best tested off PPI, and the test utilized can be either pH alone or combined pH-impedance.

GERD phenotypes and management

The presence or absence of the two core metrics on ambulatory reflux monitoring – abnormal AET and positive SRA – can stratify symptomatic GERD patients into phenotypes that predict symptomatic improvement with antireflux therapy and guide management of symptoms (Figure 3).25,26 The presence of both abnormal AET and positive SRA suggests “strong” evidence for GERD, for which symptom improvement is likely with maximization of antireflux therapy, which can include BID PPI, baclofen (to decrease transient LES relaxations), alginates (such as Gaviscon), and consideration of endosopic or surgical antireflux procedures such as fundoplication or magnetic sphincter augmentation. Abnormal AET but negative SRA is regarded as “good” evidence for GERD, for which similar antireflux therapies can be advocated. Normal AET but positive SRA is designated as “reflux hypersensitivity,”23 with increasing proportions of patients meeting this phenotype when tested with combined pH-impedance and off PPI therapy.27 Both normal AET and negative SRA suggest equivocal evidence for GERD and the likely presence of a functional esophageal disorder, such as functional heartburn.23 For reflux hypersensitivity and especially functional esophageal disorders, antireflux therapy is unlikely to be as effective and management can include pharmacologic neuromodulation (such as tricyclic antidepressants administered at bedtime) as well as adjunctive nonpharmacologic approaches (such as stress reduction, relaxation, hypnosis, or cognitive-behavioral therapy).

The future of reflux diagnostics

Conclusions

For esophageal symptoms potentially attributable to GERD that persist despite optimized PPI therapy, esophageal testing should be undertaken, starting with endoscopy and biopsies and proceeding to ambulatory reflux monitoring with HRM. The decisions between pH testing alone versus combined pH-impedance monitoring, and between testing on or off PPI therapy, can be guided either by the pre-test probability of GERD or whether GERD has been proven or unproven in prior evaluations (Figure 2). Elevated AET and positive SRA with impedance-detected reflux events can predict the likelihood of successful management outcomes from antireflux therapy. These two core metrics can be utilized to phenotype GERD and guide management approaches for persisting symptoms (Figure 3). Novel impedance metrics (baseline mucosal impedance, postreflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index) and markers for esophageal mucosal damage continue to be studied as potential markers for evidence of longitudinal reflux exposure.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Duke University School of Medicine and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, N.C. Dr. Gyawali is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo.

References

1. Shaheen N.J., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128-38.

2. Patel A., Gyawali C.P.. Switzerland: Springer International, 2016.

3. Vakil N., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-20; quiz 1943.

4. Fass R., et al. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2161-8.

5. Numans M.E., et al. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:518-27.

6. Shaheen N.J., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:225-34.

7. Roman S., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil Mar 31. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13067. [Epub ahead of print] 2017.

8. Dellon E.S., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679-92; quiz 693.

9. Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:917-30, 930 e1.

10. Shay S., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1037-43.

11. Zerbib F., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:366-72.

12. Wiener G.J., et al. Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:358-61.

13. Weusten B.L., et al. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1741-5.

14. Ghillebert G., et al. Gut 1990;31:738-44.

15. Kushnir V.M., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(9):1080-7.

16. Bredenoord A.J., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:453-9.

17. Patel A., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:884-91.

18. Slaughter J.C., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:868-74.

19. Kavitt R.T., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1826-32.

20. Kahrilas P.J., et al. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1383-91, 1391 e1-5.

21. Kessing B.F., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1020-4.

22. Kahrilas P.J., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160-74.

23. Aziz A, et al. Esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1368-79.

24. Katz P.O., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-28; quiz 329.

25. Boeckxstaens G., et al. Gut 2014;63:1185-93.

26. Patel A., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:513-21.

27. Patel A., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1382-90.

28. Martinucci I., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:546-55.

29. Ates F., et al. Gastroenterology 2015;148:334-43.

30. Kessing B.F., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2093-7.

31. Patel A., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:890-8.

32. Frazzoni M., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016.

33. Frazzoni M., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:399-406, e295.

34. Vela M.F., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:844-50.

Introduction

Chronic esophageal symptoms attributed to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are common presenting symptoms in gastroenterology, leading to high healthcare costs and adverse quality of life globally.1,2 The clinical diagnosis of GERD hinges on the presence of “troublesome” compatible typical symptoms (heartburn, acid regurgitation) or evidence of mucosal injury on endoscopy (esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic stricture).3 With the growing availability of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), patients and clinicians often utilize an empiric therapeutic trial of PPI as an initial test, with symptom improvement in the absence of alarm symptoms indicating a high likelihood of GERD.4 A meta-analysis of studies that used objective measures of GERD (in this case, 24-hour pH monitoring) showed that the “PPI test” has a sensitivity of 78%, but a specificity of only 54%, as a diagnostic approach to GERD symptoms.5 Apart from noncardiac chest pain, the diagnostic yield is even lower for atypical and extra-esophageal symptoms such as cough or laryngeal symptoms.6

The “nuts and bolts” of reflux testing

Ambulatory reflux testing assesses esophageal reflux burden and symptom-reflux association (SRA). Individual reflux events are identified as either a drop in esophageal pH to less than 4 (acid reflux events), or a sharp decrease in esophageal impedance measurements in a retrograde fashion (impedance-detected reflux events), with subsequent recovery to the baseline in each instance. Ambulatory reflux testing affords insight into three areas: 1) measurement of esophageal acid exposure time (AET); the cumulative time duration when distal esophageal pH is less than 4 at the recording site, reported as a percentage of the recording period; 2) measurement of the number of reflux events both acidic (from pH monitoring) and weakly acidic/alkaline (from impedance monitoring); and 3) quantitative evaluation of the association between reported symptom episodes and reflux events.

The SI and SAP can be calculated individually for acid-detected reflux events and for impedance-detected reflux events. Since reflux events are better detected with impedance, combined pH-impedance testing increases the yield of detecting positive SRA, especially when performed off PPI therapy.16,17 Because these indices are heavily reliant on patient reporting of symptom episodes, SRA can be overinterpreted;18 positive associations are more clinically useful than negative results in the evaluation of symptoms attributed to GERD.19 Despite these concerns, the two most consistent predictors of symptomatic outcome with antireflux therapy on pH-impedance testing are abnormal AET and positive SAP with impedance-detected reflux events.17

Testing on or off PPI?

For symptoms attributable to GERD that persist despite properly administered PPI therapy, the 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines suggest upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies for typical symptoms and appropriate referrals for atypical symptoms.24 However, if these evaluations are unremarkable, reflux monitoring is recommended, with PPI status for testing guided by the pre-test probability of GERD: with a low pre-test probability of GERD, reflux testing is best performed off PPI with either pH or combined pH-impedance testing. In contrast, with a high pre-test probability of GERD, testing is best performed on PPI with combined pH-impedance testing. A similar concept is proposed in the Rome IV approach (Figure 2)23 and on GERD consensus guidelines:7 when heartburn or chest pain persists despite PPI therapy and endoscopy and esophageal biopsies are normal, evidence for GERD (past esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, peptic stricture, or prior positive reflux testing) prompts pH-impedance monitoring on PPI therapy (i.e., proven GERD). Those without this evidence for proven GERD (i.e., unproven GERD) are best tested off PPI, and the test utilized can be either pH alone or combined pH-impedance.

GERD phenotypes and management

The presence or absence of the two core metrics on ambulatory reflux monitoring – abnormal AET and positive SRA – can stratify symptomatic GERD patients into phenotypes that predict symptomatic improvement with antireflux therapy and guide management of symptoms (Figure 3).25,26 The presence of both abnormal AET and positive SRA suggests “strong” evidence for GERD, for which symptom improvement is likely with maximization of antireflux therapy, which can include BID PPI, baclofen (to decrease transient LES relaxations), alginates (such as Gaviscon), and consideration of endosopic or surgical antireflux procedures such as fundoplication or magnetic sphincter augmentation. Abnormal AET but negative SRA is regarded as “good” evidence for GERD, for which similar antireflux therapies can be advocated. Normal AET but positive SRA is designated as “reflux hypersensitivity,”23 with increasing proportions of patients meeting this phenotype when tested with combined pH-impedance and off PPI therapy.27 Both normal AET and negative SRA suggest equivocal evidence for GERD and the likely presence of a functional esophageal disorder, such as functional heartburn.23 For reflux hypersensitivity and especially functional esophageal disorders, antireflux therapy is unlikely to be as effective and management can include pharmacologic neuromodulation (such as tricyclic antidepressants administered at bedtime) as well as adjunctive nonpharmacologic approaches (such as stress reduction, relaxation, hypnosis, or cognitive-behavioral therapy).

The future of reflux diagnostics

Conclusions

For esophageal symptoms potentially attributable to GERD that persist despite optimized PPI therapy, esophageal testing should be undertaken, starting with endoscopy and biopsies and proceeding to ambulatory reflux monitoring with HRM. The decisions between pH testing alone versus combined pH-impedance monitoring, and between testing on or off PPI therapy, can be guided either by the pre-test probability of GERD or whether GERD has been proven or unproven in prior evaluations (Figure 2). Elevated AET and positive SRA with impedance-detected reflux events can predict the likelihood of successful management outcomes from antireflux therapy. These two core metrics can be utilized to phenotype GERD and guide management approaches for persisting symptoms (Figure 3). Novel impedance metrics (baseline mucosal impedance, postreflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index) and markers for esophageal mucosal damage continue to be studied as potential markers for evidence of longitudinal reflux exposure.

Dr. Patel is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Duke University School of Medicine and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, N.C. Dr. Gyawali is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo.

References

1. Shaheen N.J., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128-38.

2. Patel A., Gyawali C.P.. Switzerland: Springer International, 2016.

3. Vakil N., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-20; quiz 1943.

4. Fass R., et al. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2161-8.

5. Numans M.E., et al. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:518-27.

6. Shaheen N.J., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:225-34.

7. Roman S., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil Mar 31. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13067. [Epub ahead of print] 2017.

8. Dellon E.S., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679-92; quiz 693.

9. Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:917-30, 930 e1.

10. Shay S., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1037-43.

11. Zerbib F., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:366-72.

12. Wiener G.J., et al. Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:358-61.

13. Weusten B.L., et al. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1741-5.

14. Ghillebert G., et al. Gut 1990;31:738-44.

15. Kushnir V.M., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(9):1080-7.

16. Bredenoord A.J., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:453-9.

17. Patel A., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:884-91.

18. Slaughter J.C., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:868-74.

19. Kavitt R.T., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1826-32.

20. Kahrilas P.J., et al. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1383-91, 1391 e1-5.

21. Kessing B.F., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1020-4.

22. Kahrilas P.J., et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160-74.