User login

Renal Function Caveats

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

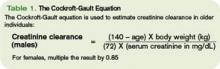

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

SHM Behind the Scenes

You may have noticed a new look to SHM’s Web site. To the naked eye, many of these changes might appear subtle. Behind the nuanced changes to the graphical interface, the content now resides in a completely different structure that allows users to more easily find information and resources.

Why the change? As SHM’s interactive services manager, I have spent a lot of time trying to find pages of content on the SHM Web site that need to be added, updated, or removed. This is not a task for the faint of heart, considering there are more than 10,000 active pages on the SHM Web site.

About a year ago, after a particularly head-splitting day of trying to find an obscure piece of information, I concluded: “There has got to be a better way to organize the information on this site!” After discussions with key stakeholders, we concluded it was time to completely reorganize our Web site. As a reward for bringing this to everyone’s attention, I was chosen to head the endeavor.

After a couple of minutes of pondering the sheer magnitude of the effort I thought for a moment about taking an extended leave of absence. It would have been easy to sit in my cubicle and pound out a new architecture I thought would work well for the organization’s needs. But the reality was that just about everybody would need a say in the process.

As one of the most prominent faces of the organization, the Web site projects the core of SHM. Its online presence is a major tool for finding and engaging members, promoting SHM’s major initiatives and letting the world know exactly what the hospital medicine movement is about. Because of this, it was imperative that all the individuals involved in making the Society what it is were involved in the process of creating an information architecture for the Web site that would best serve the needs of all our users.

Right from the beginning of the process, it was clear that in order to create an information structure that worked for the organization as a whole, everyone would need to understand the importance of each other’s stake in the content on the Web site. Once there was an across-the-board understanding of the key pieces and groups of information on the site, it would be easier to implement structural changes that made sense to the organization as a whole.

Buy-in needed to occur at a high level early on. From the beginning of this project, I saw an opportunity to use many of the teaching and group-participation skills I learned as a Peace Corp volunteer in Ukraine. Not surprisingly, much of what I used to engage individuals, generate discussions and create ideas actually worked better in a roomful of SHM staff than it did in a classroom packed with hormone driven teenagers who were more interested in knowing if I personally knew Britney Spears than speaking English.

The initial brainstorming and idea-gathering sessions we held laid a solid foundation for restructuring the site’s navigation and information architecture, making it easier to navigate and more engaging for the end-user.

In the end, brute force, hard work, and group collaboration got the job done. Without the contribution and dedication of countless members of the SHM staff and community, this project would not have become a reality.

SHM now boasts a site that is cleaner, easier to navigate, and better showcases SHM’s role as the heart of the hospital medicine movement. A Web site, like many other things in life, is always a work in progress. But we feel confident that what you see today is a significant improvement over its predecessor.

Stop by www.hospitalmedicine.org to check out the result of this organization-wide effort. Comments and suggestions are always welcome as we continue to strive to improve the user experience. E-mail me at [email protected].

You may have noticed a new look to SHM’s Web site. To the naked eye, many of these changes might appear subtle. Behind the nuanced changes to the graphical interface, the content now resides in a completely different structure that allows users to more easily find information and resources.

Why the change? As SHM’s interactive services manager, I have spent a lot of time trying to find pages of content on the SHM Web site that need to be added, updated, or removed. This is not a task for the faint of heart, considering there are more than 10,000 active pages on the SHM Web site.

About a year ago, after a particularly head-splitting day of trying to find an obscure piece of information, I concluded: “There has got to be a better way to organize the information on this site!” After discussions with key stakeholders, we concluded it was time to completely reorganize our Web site. As a reward for bringing this to everyone’s attention, I was chosen to head the endeavor.

After a couple of minutes of pondering the sheer magnitude of the effort I thought for a moment about taking an extended leave of absence. It would have been easy to sit in my cubicle and pound out a new architecture I thought would work well for the organization’s needs. But the reality was that just about everybody would need a say in the process.

As one of the most prominent faces of the organization, the Web site projects the core of SHM. Its online presence is a major tool for finding and engaging members, promoting SHM’s major initiatives and letting the world know exactly what the hospital medicine movement is about. Because of this, it was imperative that all the individuals involved in making the Society what it is were involved in the process of creating an information architecture for the Web site that would best serve the needs of all our users.

Right from the beginning of the process, it was clear that in order to create an information structure that worked for the organization as a whole, everyone would need to understand the importance of each other’s stake in the content on the Web site. Once there was an across-the-board understanding of the key pieces and groups of information on the site, it would be easier to implement structural changes that made sense to the organization as a whole.

Buy-in needed to occur at a high level early on. From the beginning of this project, I saw an opportunity to use many of the teaching and group-participation skills I learned as a Peace Corp volunteer in Ukraine. Not surprisingly, much of what I used to engage individuals, generate discussions and create ideas actually worked better in a roomful of SHM staff than it did in a classroom packed with hormone driven teenagers who were more interested in knowing if I personally knew Britney Spears than speaking English.

The initial brainstorming and idea-gathering sessions we held laid a solid foundation for restructuring the site’s navigation and information architecture, making it easier to navigate and more engaging for the end-user.

In the end, brute force, hard work, and group collaboration got the job done. Without the contribution and dedication of countless members of the SHM staff and community, this project would not have become a reality.

SHM now boasts a site that is cleaner, easier to navigate, and better showcases SHM’s role as the heart of the hospital medicine movement. A Web site, like many other things in life, is always a work in progress. But we feel confident that what you see today is a significant improvement over its predecessor.

Stop by www.hospitalmedicine.org to check out the result of this organization-wide effort. Comments and suggestions are always welcome as we continue to strive to improve the user experience. E-mail me at [email protected].

You may have noticed a new look to SHM’s Web site. To the naked eye, many of these changes might appear subtle. Behind the nuanced changes to the graphical interface, the content now resides in a completely different structure that allows users to more easily find information and resources.

Why the change? As SHM’s interactive services manager, I have spent a lot of time trying to find pages of content on the SHM Web site that need to be added, updated, or removed. This is not a task for the faint of heart, considering there are more than 10,000 active pages on the SHM Web site.

About a year ago, after a particularly head-splitting day of trying to find an obscure piece of information, I concluded: “There has got to be a better way to organize the information on this site!” After discussions with key stakeholders, we concluded it was time to completely reorganize our Web site. As a reward for bringing this to everyone’s attention, I was chosen to head the endeavor.

After a couple of minutes of pondering the sheer magnitude of the effort I thought for a moment about taking an extended leave of absence. It would have been easy to sit in my cubicle and pound out a new architecture I thought would work well for the organization’s needs. But the reality was that just about everybody would need a say in the process.

As one of the most prominent faces of the organization, the Web site projects the core of SHM. Its online presence is a major tool for finding and engaging members, promoting SHM’s major initiatives and letting the world know exactly what the hospital medicine movement is about. Because of this, it was imperative that all the individuals involved in making the Society what it is were involved in the process of creating an information architecture for the Web site that would best serve the needs of all our users.

Right from the beginning of the process, it was clear that in order to create an information structure that worked for the organization as a whole, everyone would need to understand the importance of each other’s stake in the content on the Web site. Once there was an across-the-board understanding of the key pieces and groups of information on the site, it would be easier to implement structural changes that made sense to the organization as a whole.

Buy-in needed to occur at a high level early on. From the beginning of this project, I saw an opportunity to use many of the teaching and group-participation skills I learned as a Peace Corp volunteer in Ukraine. Not surprisingly, much of what I used to engage individuals, generate discussions and create ideas actually worked better in a roomful of SHM staff than it did in a classroom packed with hormone driven teenagers who were more interested in knowing if I personally knew Britney Spears than speaking English.

The initial brainstorming and idea-gathering sessions we held laid a solid foundation for restructuring the site’s navigation and information architecture, making it easier to navigate and more engaging for the end-user.

In the end, brute force, hard work, and group collaboration got the job done. Without the contribution and dedication of countless members of the SHM staff and community, this project would not have become a reality.

SHM now boasts a site that is cleaner, easier to navigate, and better showcases SHM’s role as the heart of the hospital medicine movement. A Web site, like many other things in life, is always a work in progress. But we feel confident that what you see today is a significant improvement over its predecessor.

Stop by www.hospitalmedicine.org to check out the result of this organization-wide effort. Comments and suggestions are always welcome as we continue to strive to improve the user experience. E-mail me at [email protected].

All Eyes on San Diego

SHM’s Annual Meeting highlights hospital medicine as a distinct field within internal medicine. Being able to, year after year, incorporate core clinical topics, evidence-based practice, quality-related content, and career development into three days is only possible because of the foundation laid from previous meetings over the past 10 years.

Expectations about the role of hospitalists have taken shape through recommendations from education summits and national experts on healthcare policy, and via publications like the Journal of Hospital Medicine and The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. The Annual Meeting Committee’s goal was to define a program that facilitates hospitalists in achieving that role.

The 2008 meeting April 3-5 in San Diego will feature:

- National leaders in hospital medicine and healthcare;

- Six precourses addressing timely and relevant topics; and

- Seven tracks addressing clinical, operational, quality, academic, and pediatric issues.

Issues that have broad appeal and present challenges for hospitalists will be addressed in three widely anticipated keynotes:

Quality: Don Berwick, MD, MPP, FRCP, president and CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and architect of both the 100,000 Lives and 5 Million Lives campaigns;

The future of healthcare: Ian Morrison, PhD, president emeritus and health advisory panel chair, Institute for the Future, and an internationally known author on long-term forecasting with particular emphasis on healthcare;

Thriving in the face of comanagement, non-teaching services, transparency, and the reality of perpetual change: Robert Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine, associate chairman of the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

The future of hospital medicine: opportunities and challenges: A special plenary session presented by a panel of hospital medicine leaders who will share perspectives from:

- The large hospitalist company;

- The large hospital company as an employer;

- The hospital CEO; and

- The individual hospital employed/associated hospital medicine group.

The following program elements are only a few of the many highlights of “Hospital Medicine 2008”:

The Evidence-Based Rapid-Fire Track: This track was developed in response from last year’s attendees. It is designed to provide participants—new or old attendees, academic or community caregivers—with “rapid bursts” of content and to address specific questions framed by the committee, based on the highest level of medical evidence available.

Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) Competition: Building on a new feature from “Hospital Medicine 2007,” a nationally renowned professor will again tour the poster session and comment on the entries, meet with academic hospitalists, attend forums, and generally be a “visiting professor” for the duration of the meeting. Additionally, SHM’s RIV Committee, along with staff, are working on arrangements for junior faculty to interact with senior researchers during times that run concurrent with non-plenary sessions. Senior hospitalists with expertise in quality-improvement research will also provide individual feedback to authors at the poster sessions. Mini poster presentation sessions will provide a way for residents to highlight their work, and there will be new, separate receptions for the posters (April 3) and exhibits (April 4).

More networking: Networking provides a critical outlet to interact with senior hospitalists, find out what others are doing to advance their careers, and seek mentorship. In addition to the networking opportunities incorporated in the RIV Competition, other networking opportunities include the exhibits, President’s Luncheon and additional receptions, and two new special-interest forums on com-anagement and consultative medicine and international hospital medicine.

The Annual Meeting Committee sought improvements in developing and implementing this year’s program. Committee brainstorming sessions for this year’s meeting focused on:

- Balancing what works with innovation;

- Making the meeting more valuable to clinical educators and researchers, and more applicable to community hospitalists; and

- Showing national leaders the extraordinary talent behind and work of SHM.

A key innovation was a successful “call for speakers.” Submissions were sought for three breakout sessions to create additional opportunity for members to play an active role in “Hospital Medicine 2008.” Based on submissions, sessions were added on the following topics:

- “Prevention, Management, and Treatment of Acute Delirium”;

- “Designing Compensation and Bonus Plans to Drive Desired Behavior”; and

- “Acute Coronary Syndrome Trials and Tribulations.”

Changes for “Hospital Medicine 2008” reflect the volunteerism of many professionals and would not have been possible without the mentorship and expertise of seasoned veteran leaders in hospital medicine, as well as the feedback and participation of hospitalists providing daily inpatient care. As part of a continuous quality-improvement initiative, rules of engagement were developed so speakers would have useful information up front.

The success of the SHM Annual Meeting depends upon the participation and leadership of SHM members, staff, committees, and task forces, as well as the SHM Board. My thanks goes out to them all for their efforts in once again creating a top-flight program.

For more information on “Hospital Medicine 2008,” and to register, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/hospitalmedicine2008.

SHM’s Annual Meeting highlights hospital medicine as a distinct field within internal medicine. Being able to, year after year, incorporate core clinical topics, evidence-based practice, quality-related content, and career development into three days is only possible because of the foundation laid from previous meetings over the past 10 years.

Expectations about the role of hospitalists have taken shape through recommendations from education summits and national experts on healthcare policy, and via publications like the Journal of Hospital Medicine and The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. The Annual Meeting Committee’s goal was to define a program that facilitates hospitalists in achieving that role.

The 2008 meeting April 3-5 in San Diego will feature:

- National leaders in hospital medicine and healthcare;

- Six precourses addressing timely and relevant topics; and

- Seven tracks addressing clinical, operational, quality, academic, and pediatric issues.

Issues that have broad appeal and present challenges for hospitalists will be addressed in three widely anticipated keynotes:

Quality: Don Berwick, MD, MPP, FRCP, president and CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and architect of both the 100,000 Lives and 5 Million Lives campaigns;

The future of healthcare: Ian Morrison, PhD, president emeritus and health advisory panel chair, Institute for the Future, and an internationally known author on long-term forecasting with particular emphasis on healthcare;

Thriving in the face of comanagement, non-teaching services, transparency, and the reality of perpetual change: Robert Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine, associate chairman of the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

The future of hospital medicine: opportunities and challenges: A special plenary session presented by a panel of hospital medicine leaders who will share perspectives from:

- The large hospitalist company;

- The large hospital company as an employer;

- The hospital CEO; and

- The individual hospital employed/associated hospital medicine group.

The following program elements are only a few of the many highlights of “Hospital Medicine 2008”:

The Evidence-Based Rapid-Fire Track: This track was developed in response from last year’s attendees. It is designed to provide participants—new or old attendees, academic or community caregivers—with “rapid bursts” of content and to address specific questions framed by the committee, based on the highest level of medical evidence available.

Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) Competition: Building on a new feature from “Hospital Medicine 2007,” a nationally renowned professor will again tour the poster session and comment on the entries, meet with academic hospitalists, attend forums, and generally be a “visiting professor” for the duration of the meeting. Additionally, SHM’s RIV Committee, along with staff, are working on arrangements for junior faculty to interact with senior researchers during times that run concurrent with non-plenary sessions. Senior hospitalists with expertise in quality-improvement research will also provide individual feedback to authors at the poster sessions. Mini poster presentation sessions will provide a way for residents to highlight their work, and there will be new, separate receptions for the posters (April 3) and exhibits (April 4).

More networking: Networking provides a critical outlet to interact with senior hospitalists, find out what others are doing to advance their careers, and seek mentorship. In addition to the networking opportunities incorporated in the RIV Competition, other networking opportunities include the exhibits, President’s Luncheon and additional receptions, and two new special-interest forums on com-anagement and consultative medicine and international hospital medicine.

The Annual Meeting Committee sought improvements in developing and implementing this year’s program. Committee brainstorming sessions for this year’s meeting focused on:

- Balancing what works with innovation;

- Making the meeting more valuable to clinical educators and researchers, and more applicable to community hospitalists; and

- Showing national leaders the extraordinary talent behind and work of SHM.

A key innovation was a successful “call for speakers.” Submissions were sought for three breakout sessions to create additional opportunity for members to play an active role in “Hospital Medicine 2008.” Based on submissions, sessions were added on the following topics:

- “Prevention, Management, and Treatment of Acute Delirium”;

- “Designing Compensation and Bonus Plans to Drive Desired Behavior”; and

- “Acute Coronary Syndrome Trials and Tribulations.”

Changes for “Hospital Medicine 2008” reflect the volunteerism of many professionals and would not have been possible without the mentorship and expertise of seasoned veteran leaders in hospital medicine, as well as the feedback and participation of hospitalists providing daily inpatient care. As part of a continuous quality-improvement initiative, rules of engagement were developed so speakers would have useful information up front.

The success of the SHM Annual Meeting depends upon the participation and leadership of SHM members, staff, committees, and task forces, as well as the SHM Board. My thanks goes out to them all for their efforts in once again creating a top-flight program.

For more information on “Hospital Medicine 2008,” and to register, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/hospitalmedicine2008.

SHM’s Annual Meeting highlights hospital medicine as a distinct field within internal medicine. Being able to, year after year, incorporate core clinical topics, evidence-based practice, quality-related content, and career development into three days is only possible because of the foundation laid from previous meetings over the past 10 years.

Expectations about the role of hospitalists have taken shape through recommendations from education summits and national experts on healthcare policy, and via publications like the Journal of Hospital Medicine and The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. The Annual Meeting Committee’s goal was to define a program that facilitates hospitalists in achieving that role.

The 2008 meeting April 3-5 in San Diego will feature:

- National leaders in hospital medicine and healthcare;

- Six precourses addressing timely and relevant topics; and

- Seven tracks addressing clinical, operational, quality, academic, and pediatric issues.

Issues that have broad appeal and present challenges for hospitalists will be addressed in three widely anticipated keynotes:

Quality: Don Berwick, MD, MPP, FRCP, president and CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and architect of both the 100,000 Lives and 5 Million Lives campaigns;

The future of healthcare: Ian Morrison, PhD, president emeritus and health advisory panel chair, Institute for the Future, and an internationally known author on long-term forecasting with particular emphasis on healthcare;

Thriving in the face of comanagement, non-teaching services, transparency, and the reality of perpetual change: Robert Wachter, MD, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine, associate chairman of the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

The future of hospital medicine: opportunities and challenges: A special plenary session presented by a panel of hospital medicine leaders who will share perspectives from:

- The large hospitalist company;

- The large hospital company as an employer;

- The hospital CEO; and

- The individual hospital employed/associated hospital medicine group.

The following program elements are only a few of the many highlights of “Hospital Medicine 2008”:

The Evidence-Based Rapid-Fire Track: This track was developed in response from last year’s attendees. It is designed to provide participants—new or old attendees, academic or community caregivers—with “rapid bursts” of content and to address specific questions framed by the committee, based on the highest level of medical evidence available.

Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) Competition: Building on a new feature from “Hospital Medicine 2007,” a nationally renowned professor will again tour the poster session and comment on the entries, meet with academic hospitalists, attend forums, and generally be a “visiting professor” for the duration of the meeting. Additionally, SHM’s RIV Committee, along with staff, are working on arrangements for junior faculty to interact with senior researchers during times that run concurrent with non-plenary sessions. Senior hospitalists with expertise in quality-improvement research will also provide individual feedback to authors at the poster sessions. Mini poster presentation sessions will provide a way for residents to highlight their work, and there will be new, separate receptions for the posters (April 3) and exhibits (April 4).

More networking: Networking provides a critical outlet to interact with senior hospitalists, find out what others are doing to advance their careers, and seek mentorship. In addition to the networking opportunities incorporated in the RIV Competition, other networking opportunities include the exhibits, President’s Luncheon and additional receptions, and two new special-interest forums on com-anagement and consultative medicine and international hospital medicine.

The Annual Meeting Committee sought improvements in developing and implementing this year’s program. Committee brainstorming sessions for this year’s meeting focused on:

- Balancing what works with innovation;

- Making the meeting more valuable to clinical educators and researchers, and more applicable to community hospitalists; and

- Showing national leaders the extraordinary talent behind and work of SHM.

A key innovation was a successful “call for speakers.” Submissions were sought for three breakout sessions to create additional opportunity for members to play an active role in “Hospital Medicine 2008.” Based on submissions, sessions were added on the following topics:

- “Prevention, Management, and Treatment of Acute Delirium”;

- “Designing Compensation and Bonus Plans to Drive Desired Behavior”; and

- “Acute Coronary Syndrome Trials and Tribulations.”

Changes for “Hospital Medicine 2008” reflect the volunteerism of many professionals and would not have been possible without the mentorship and expertise of seasoned veteran leaders in hospital medicine, as well as the feedback and participation of hospitalists providing daily inpatient care. As part of a continuous quality-improvement initiative, rules of engagement were developed so speakers would have useful information up front.

The success of the SHM Annual Meeting depends upon the participation and leadership of SHM members, staff, committees, and task forces, as well as the SHM Board. My thanks goes out to them all for their efforts in once again creating a top-flight program.

For more information on “Hospital Medicine 2008,” and to register, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/hospitalmedicine2008.

Malpractice Chronicle

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Who Was to Blame for Hyponatremia Death?

At age 63, a man visited the defendant family physician with complaints of fever and productive cough; he also needed a change in his blood pressure medication.

Chest x-ray results were negative, and the defendant prescribed an antibiotic. Six days later, the patient returned to the defendant’s office with similar but waning symptoms and new complaints consistent with anxiety and depression.

Over the following four days, the patient’s wife placed two documented calls to the defendant’s office to update him regarding the patient’s condition. The patient was subsequently taken to a hospital emergency department, where a sodium level of 101 mEq/L was detected on blood chemistry. A diagnosis of hyponatremia was made and an isotonic saline solution started.

The patient was then transferred to another hospital, where a hypertonic saline solution was ordered. Because his sodium level was replenished too quickly, the man developed central pontine myelinolysis (CPM). Three weeks later, he died of CPM-related aspiration pneumonia.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant physician failed to diagnose hyponatremia and to give the patient proper treatment, which led to his death.

The defendant contended that there was no way to diagnose hyponatremia, based on the decedent’s signs and symptoms. The defendant also charged that death was caused by mistreatment at the hospital where the patient died.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned.

Pneumonia Patient Sent Home Too Soon

Complaints of upper back pain, evidently exacerbated by respiration, took a 44-year-old woman to a hospital emergency department. Tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count, but a chest x-ray was clear. A diagnosis of a pulled muscle was made; the patient was sent home with prescriptions for naproxen and hydrocodone with acetaminophen.

Four days later, the patient went to a clinic complaining of back pain. A second chest x-ray showed extensive right-sided pneumonia, for which she was hospitalized. Test results revealed that the patient was hypoxic, that her band cells were elevated to 65%, and that her white blood cell count was 5,000/mL. An additional chest x-ray was ordered, which the plaintiffs later claimed showed worsening pneumonia in the right lung.

When the patient complained of severely increased pain, her medications were discontinued and IV morphine was initiated. On day 5 of the patient’s hospital stay, her case was transferred to a different physician, and she was discharged two days later.

When the patient’s condition had not improved five days after her discharge, she placed a call to her physician, which was not returned. Very early the next morning, the woman was taken to the hospital. An hour later, she was pronounced dead as a result of cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to pneumonia.

Plaintiffs claimed that the decedent was prematurely discharged and that the defendant was negligent in failing to return her phone call. The defendant argued that the test results and x-rays that the plaintiffs claimed contraindicated discharge were not available when the decision was made to discharge the decedent. The defendant also claimed that, according to the office telephone record, the decedent had failed to convey any urgency when she called; thus, there was no negligence in failing to return the call that day. The plaintiffs maintained that the call had described the patient’s situation as urgent.

According to a published account, an $864,000 arbitration award was given.

Was Surgery for Hydrocephalus Delayed?

A 53-year-old man presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) after experiencing headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and a temperature as high as 101.9°F for several days. After the initial physical examination, nystagmus was diagnosed; meningitis was not considered. The patient was sent home with medication.

The next day, he returned to the same ED. MRI and CT of the brain revealed a 1.0-in brain tumor and hydrocephalus. The man was admitted for neurosurgical evaluation and treatment. During his examination, he was somewhat disoriented but could carry on a conversation. He was also able to stand, and his reflexes (including the pupillary reflexes) were normal. When increased hydrocephalus and intracranial pressure became evident, he was given steroids and mannitol.

The next day, the patient was lethargic, and his pupillary reflexes were slowly reactive. He responded to voice commands, but there were signs of increasing intracranial pressure.

That evening, the man ceased responding to voice commands and appeared increasingly confused. The following day, he was more lethargic. He made no spontaneous movements and no response to commands, although he did withdraw from painful stimuli. A repeat MRI showed the tumor and hydrocephalus.

Surgery was performed for removal of the tumor, which was identified as a T-cell lymphoma. The patient did not regain consciousness after the surgery. CT performed shortly thereafter showed herniation of the brain and diffuse hypoxic damage of a duration to suggest that it had occurred before the surgery.

The family refused a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order and discontinuation of life support. For nine days after the surgery, the medical staff tried to persuade the family that the patient was dead; they then wrote a DNR order in the chart. When the family protested, doctors transferred the decedent out of the ICU and discontinued all medical support; they also clamped the ventriculostomy tube that had been placed after surgery. The decedent’s blood pressure and pulse remained normal, and his only requirements for life were IV fluids and a respirator.

After continued protest, the family was told that DNR orders are within the doctor’s decision. Consent was then sought to harvest the decedent’s organs for transplantation. Some 25 family members were present when a nurse discontinued the ventilator, and the man died.

Twenty-one family members sued for intentional infliction of emotional distress. Plaintiffs claimed that the decedent was in a coma that was caused not by the tumor but by hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure that accompanied the tumor. The plaintiffs claimed that a decompressing ventriculostomy would have prevented the herniation and hypoxic brain damage; this developed either before or during the surgery, which they charged was delayed. The plaintiffs also claimed that the decedent was not dead when life support was discontinued. The last electroencephalogram showed brain activity, they claimed, and the decedent’s blood pressure and pulse remained normal without any medical support. The plaintiffs also claimed that the decedent made respiratory movements for five minutes after the respirator was discontinued.

The defendants argued that the delay in performing surgery was necessary and that the decedent’s deterioration resulted from administration of sedatives to obtain a clear MRI. The defendants also claimed that the decedent was brain-dead after the surgery and that malpractice and wrongful death claims could not be applied to a person who was already dead.

According to a published report, a $425,000 settlement was reached.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Who Was to Blame for Hyponatremia Death?

At age 63, a man visited the defendant family physician with complaints of fever and productive cough; he also needed a change in his blood pressure medication.

Chest x-ray results were negative, and the defendant prescribed an antibiotic. Six days later, the patient returned to the defendant’s office with similar but waning symptoms and new complaints consistent with anxiety and depression.

Over the following four days, the patient’s wife placed two documented calls to the defendant’s office to update him regarding the patient’s condition. The patient was subsequently taken to a hospital emergency department, where a sodium level of 101 mEq/L was detected on blood chemistry. A diagnosis of hyponatremia was made and an isotonic saline solution started.

The patient was then transferred to another hospital, where a hypertonic saline solution was ordered. Because his sodium level was replenished too quickly, the man developed central pontine myelinolysis (CPM). Three weeks later, he died of CPM-related aspiration pneumonia.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant physician failed to diagnose hyponatremia and to give the patient proper treatment, which led to his death.

The defendant contended that there was no way to diagnose hyponatremia, based on the decedent’s signs and symptoms. The defendant also charged that death was caused by mistreatment at the hospital where the patient died.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned.

Pneumonia Patient Sent Home Too Soon

Complaints of upper back pain, evidently exacerbated by respiration, took a 44-year-old woman to a hospital emergency department. Tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count, but a chest x-ray was clear. A diagnosis of a pulled muscle was made; the patient was sent home with prescriptions for naproxen and hydrocodone with acetaminophen.

Four days later, the patient went to a clinic complaining of back pain. A second chest x-ray showed extensive right-sided pneumonia, for which she was hospitalized. Test results revealed that the patient was hypoxic, that her band cells were elevated to 65%, and that her white blood cell count was 5,000/mL. An additional chest x-ray was ordered, which the plaintiffs later claimed showed worsening pneumonia in the right lung.

When the patient complained of severely increased pain, her medications were discontinued and IV morphine was initiated. On day 5 of the patient’s hospital stay, her case was transferred to a different physician, and she was discharged two days later.

When the patient’s condition had not improved five days after her discharge, she placed a call to her physician, which was not returned. Very early the next morning, the woman was taken to the hospital. An hour later, she was pronounced dead as a result of cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to pneumonia.

Plaintiffs claimed that the decedent was prematurely discharged and that the defendant was negligent in failing to return her phone call. The defendant argued that the test results and x-rays that the plaintiffs claimed contraindicated discharge were not available when the decision was made to discharge the decedent. The defendant also claimed that, according to the office telephone record, the decedent had failed to convey any urgency when she called; thus, there was no negligence in failing to return the call that day. The plaintiffs maintained that the call had described the patient’s situation as urgent.

According to a published account, an $864,000 arbitration award was given.

Was Surgery for Hydrocephalus Delayed?

A 53-year-old man presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) after experiencing headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and a temperature as high as 101.9°F for several days. After the initial physical examination, nystagmus was diagnosed; meningitis was not considered. The patient was sent home with medication.

The next day, he returned to the same ED. MRI and CT of the brain revealed a 1.0-in brain tumor and hydrocephalus. The man was admitted for neurosurgical evaluation and treatment. During his examination, he was somewhat disoriented but could carry on a conversation. He was also able to stand, and his reflexes (including the pupillary reflexes) were normal. When increased hydrocephalus and intracranial pressure became evident, he was given steroids and mannitol.

The next day, the patient was lethargic, and his pupillary reflexes were slowly reactive. He responded to voice commands, but there were signs of increasing intracranial pressure.

That evening, the man ceased responding to voice commands and appeared increasingly confused. The following day, he was more lethargic. He made no spontaneous movements and no response to commands, although he did withdraw from painful stimuli. A repeat MRI showed the tumor and hydrocephalus.

Surgery was performed for removal of the tumor, which was identified as a T-cell lymphoma. The patient did not regain consciousness after the surgery. CT performed shortly thereafter showed herniation of the brain and diffuse hypoxic damage of a duration to suggest that it had occurred before the surgery.

The family refused a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order and discontinuation of life support. For nine days after the surgery, the medical staff tried to persuade the family that the patient was dead; they then wrote a DNR order in the chart. When the family protested, doctors transferred the decedent out of the ICU and discontinued all medical support; they also clamped the ventriculostomy tube that had been placed after surgery. The decedent’s blood pressure and pulse remained normal, and his only requirements for life were IV fluids and a respirator.

After continued protest, the family was told that DNR orders are within the doctor’s decision. Consent was then sought to harvest the decedent’s organs for transplantation. Some 25 family members were present when a nurse discontinued the ventilator, and the man died.

Twenty-one family members sued for intentional infliction of emotional distress. Plaintiffs claimed that the decedent was in a coma that was caused not by the tumor but by hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure that accompanied the tumor. The plaintiffs claimed that a decompressing ventriculostomy would have prevented the herniation and hypoxic brain damage; this developed either before or during the surgery, which they charged was delayed. The plaintiffs also claimed that the decedent was not dead when life support was discontinued. The last electroencephalogram showed brain activity, they claimed, and the decedent’s blood pressure and pulse remained normal without any medical support. The plaintiffs also claimed that the decedent made respiratory movements for five minutes after the respirator was discontinued.

The defendants argued that the delay in performing surgery was necessary and that the decedent’s deterioration resulted from administration of sedatives to obtain a clear MRI. The defendants also claimed that the decedent was brain-dead after the surgery and that malpractice and wrongful death claims could not be applied to a person who was already dead.

According to a published report, a $425,000 settlement was reached.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Who Was to Blame for Hyponatremia Death?

At age 63, a man visited the defendant family physician with complaints of fever and productive cough; he also needed a change in his blood pressure medication.

Chest x-ray results were negative, and the defendant prescribed an antibiotic. Six days later, the patient returned to the defendant’s office with similar but waning symptoms and new complaints consistent with anxiety and depression.

Over the following four days, the patient’s wife placed two documented calls to the defendant’s office to update him regarding the patient’s condition. The patient was subsequently taken to a hospital emergency department, where a sodium level of 101 mEq/L was detected on blood chemistry. A diagnosis of hyponatremia was made and an isotonic saline solution started.

The patient was then transferred to another hospital, where a hypertonic saline solution was ordered. Because his sodium level was replenished too quickly, the man developed central pontine myelinolysis (CPM). Three weeks later, he died of CPM-related aspiration pneumonia.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant physician failed to diagnose hyponatremia and to give the patient proper treatment, which led to his death.

The defendant contended that there was no way to diagnose hyponatremia, based on the decedent’s signs and symptoms. The defendant also charged that death was caused by mistreatment at the hospital where the patient died.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned.

Pneumonia Patient Sent Home Too Soon

Complaints of upper back pain, evidently exacerbated by respiration, took a 44-year-old woman to a hospital emergency department. Tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count, but a chest x-ray was clear. A diagnosis of a pulled muscle was made; the patient was sent home with prescriptions for naproxen and hydrocodone with acetaminophen.

Four days later, the patient went to a clinic complaining of back pain. A second chest x-ray showed extensive right-sided pneumonia, for which she was hospitalized. Test results revealed that the patient was hypoxic, that her band cells were elevated to 65%, and that her white blood cell count was 5,000/mL. An additional chest x-ray was ordered, which the plaintiffs later claimed showed worsening pneumonia in the right lung.

When the patient complained of severely increased pain, her medications were discontinued and IV morphine was initiated. On day 5 of the patient’s hospital stay, her case was transferred to a different physician, and she was discharged two days later.

When the patient’s condition had not improved five days after her discharge, she placed a call to her physician, which was not returned. Very early the next morning, the woman was taken to the hospital. An hour later, she was pronounced dead as a result of cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to pneumonia.

Plaintiffs claimed that the decedent was prematurely discharged and that the defendant was negligent in failing to return her phone call. The defendant argued that the test results and x-rays that the plaintiffs claimed contraindicated discharge were not available when the decision was made to discharge the decedent. The defendant also claimed that, according to the office telephone record, the decedent had failed to convey any urgency when she called; thus, there was no negligence in failing to return the call that day. The plaintiffs maintained that the call had described the patient’s situation as urgent.

According to a published account, an $864,000 arbitration award was given.

Was Surgery for Hydrocephalus Delayed?

A 53-year-old man presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) after experiencing headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and a temperature as high as 101.9°F for several days. After the initial physical examination, nystagmus was diagnosed; meningitis was not considered. The patient was sent home with medication.

The next day, he returned to the same ED. MRI and CT of the brain revealed a 1.0-in brain tumor and hydrocephalus. The man was admitted for neurosurgical evaluation and treatment. During his examination, he was somewhat disoriented but could carry on a conversation. He was also able to stand, and his reflexes (including the pupillary reflexes) were normal. When increased hydrocephalus and intracranial pressure became evident, he was given steroids and mannitol.

The next day, the patient was lethargic, and his pupillary reflexes were slowly reactive. He responded to voice commands, but there were signs of increasing intracranial pressure.

That evening, the man ceased responding to voice commands and appeared increasingly confused. The following day, he was more lethargic. He made no spontaneous movements and no response to commands, although he did withdraw from painful stimuli. A repeat MRI showed the tumor and hydrocephalus.

Surgery was performed for removal of the tumor, which was identified as a T-cell lymphoma. The patient did not regain consciousness after the surgery. CT performed shortly thereafter showed herniation of the brain and diffuse hypoxic damage of a duration to suggest that it had occurred before the surgery.

The family refused a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order and discontinuation of life support. For nine days after the surgery, the medical staff tried to persuade the family that the patient was dead; they then wrote a DNR order in the chart. When the family protested, doctors transferred the decedent out of the ICU and discontinued all medical support; they also clamped the ventriculostomy tube that had been placed after surgery. The decedent’s blood pressure and pulse remained normal, and his only requirements for life were IV fluids and a respirator.

After continued protest, the family was told that DNR orders are within the doctor’s decision. Consent was then sought to harvest the decedent’s organs for transplantation. Some 25 family members were present when a nurse discontinued the ventilator, and the man died.

Twenty-one family members sued for intentional infliction of emotional distress. Plaintiffs claimed that the decedent was in a coma that was caused not by the tumor but by hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure that accompanied the tumor. The plaintiffs claimed that a decompressing ventriculostomy would have prevented the herniation and hypoxic brain damage; this developed either before or during the surgery, which they charged was delayed. The plaintiffs also claimed that the decedent was not dead when life support was discontinued. The last electroencephalogram showed brain activity, they claimed, and the decedent’s blood pressure and pulse remained normal without any medical support. The plaintiffs also claimed that the decedent made respiratory movements for five minutes after the respirator was discontinued.

The defendants argued that the delay in performing surgery was necessary and that the decedent’s deterioration resulted from administration of sedatives to obtain a clear MRI. The defendants also claimed that the decedent was brain-dead after the surgery and that malpractice and wrongful death claims could not be applied to a person who was already dead.

According to a published report, a $425,000 settlement was reached.

Do feeding tubes improve outcomes in patients with dementia?

Case

A 68-year-old cachectic female with a history of Alzheimer’s dementia presents with a slowly progressive decline in functional status. She is bed bound, minimally verbal, and has lost interest in eating.

Her problems with decreased oral intake started when her diet was changed to nectar-thickened liquids. This change was made after the patient was hospitalized multiple times for aspiration pneumonia and she underwent a fluoroscopic swallowing evaluation that revealed aspiration of thin liquids. The patient’s husband requests that a feeding tube be placed so his wife doesn’t “die of pneumonia or starve to death.”

Overview

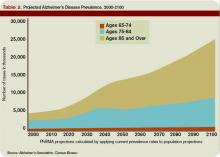

As the U.S. population ages, hospitalists are seeing a steady increase in the average patient age and the prevalence of dementia. Alzheimer’s dementia affects an estimated 4 million to 5 million Americans; this number expected to triple by the year 2050.1

As patients with dementia near the end of life, they often fail to thrive, with less oral intake and more swallowing disorders leading to aspiration. This is when physicians and patient family members must decide whether a feeding tube should be placed.

Placement of a nasogastric or percutaneous endogastric gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube has become a relatively common medical intervention instituted to maintain or improve a patient’s nutritional status. Prior to 1980, permanent gastric or postpyloric feeding tubes were placed surgically by laparotomy, but the advent of endoscopy and computed tomography (CT) guided procedures offers a simplified procedure requiring only mild sedation and local anesthesia.2

Many patients who suffer multiple bouts of aspiration pneumonia and fail a swallowing evaluation because of an irreversible process are offered a percutaneous feeding tube to maintain nutrition. A feeding tube is also seen as a way to supply nutrition at the end of life in patients no longer able or willing to take food orally.

Although it seems logical that a feeding tube might improve the outcomes of these clinical scenarios, limited literature exists on the topic because of the legal, ethical, emotional, and religious implications a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial would entail.

Review of the Data

Placement of a PEG has become accepted as a relatively benign procedure, although it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Minor complications including pain, abdominal wall ulcers, wound infections, peristomal leakage, and tube displacement occur in approximately 10% of cases.3 Major complications including hemorrhage, bowel or liver perforation, or aspiration occur in 3% of cases.4

These numbers do not account for long-term complications including peristomal infections, leakage problems, or the use of physical restraints to avoid self-extubation.

Aspiration Risk

A common indication for PEG placement is aspiration risk. PEG tubes are often placed in patients who fail swallowing evaluations in order to decrease their risk of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia.

True aspiration pneumonia is thought to originate from an inoculum of oral cavity or nasopharynx bacteria, which placement of a PEG tube would not prevent. Leibovitz, et al., showed that elderly patients with nasogastric or percutaneous feeding tubes are associated with colonization of the oropharynx with more pathogenic bacteria when compared with orally fed patients.5 Thus, the use of PEG tubes might put them at higher risk for pathogenic inoculation.

Aspiration pneumonia occurs in up to 50% of patients with feeding tubes. Studies have shown PEG tube placement decreases lower esophageal sphincter tone, potentially increasing regurgitation risk.6 It has also been shown that aspiration of gastric contents produces a pneumonitis with the resultant inflammatory response allowing for establishment of infection by smaller inoculums of or less virulent organisms.7

Small, randomized trials have shown no decrease in aspiration risk with post-pyloric versus gastric feeding tubes, nasogastric versus percutaneous feeding tubes, or continuous versus intermittent tube feeds.8 There have been no sizable randomized prospective trials to determine if feeding tube placement versus hand feeding patients with end-stage dementia alters aspiration pneumonia risk.

Pressure Ulcers

Patients with end-stage dementia often become bed bound as their disease progresses, and they commonly suffer from pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers often coexist in patients with malnutrition, and it is well established that patients with biochemical markers of malnutrition are at higher risk for pressure ulcer formation.

Still, no studies show that improved nutrition prevents pressure ulcer formation. In a nursing home population of patients with dementia, a two-year follow-up study showed no significant improvement in pressure ulcer healing or decreased ulcer formation with nutrition by feeding tube.9 These studies are adjusted for independent risk factors for mortality and indication for PEG placement, but we can assume there are confounders that go into the decision for feeding tube placement that are not necessarily identifiable.

Nutritional Status

Family members are often concerned that if the patient is unable to take food by mouth and no feeding tube is placed, then the patient will suffer from the discomfort of starvation and dehydration.

As a patient with a severe dementing illness enters the end stage of his/her clinical course, practitioners frequently make a plan with families to change the goals of care toward keeping the patient comfortable. Comfort is a difficult clinical parameter to measure, but studies in the hospice population of patients with end-stage cancer and AIDS report that the hunger and thirst are transient and improve with ice chips and mouth swabs.10

Despite the lack of evidence of PEG tubes prolonging survival in patients with dementia who are no longer able or willing to take in food orally, it is logical that withholding all hydration or nutritional support will hasten death despite the risks associated with feeding tubes. This is where the ethical argument arises regarding prolonging life of decreasing quality.

In certain medical and legal sectors, artificial nutrition, and hydration are considered a medical intervention. Therefore, the ideals of patient autonomy dictate that the patient’s proxy should decide whether or not the patient would have wanted the intervention after weighing the risks and benefits.

If hospitalists view artificial nutrition as a medical intervention, our moral obligation is to instruct patients and their families about these risks and benefits.

Often, the patient will not clinically improve with artificial nutrition. But we can maintain physiologic processes or at least slow their decline.

Emerging research indicates the standard of care in how we present this information is changing to include presentation of data instead of only using a patient’s suspected beliefs about quality of life.

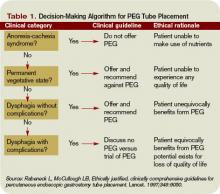

A useful algorithm proposed by Rabeneck, et al., provides comprehensive guidelines for PEG placement in all patient populations based on the reason for PEG consideration.11

Back to the Case

Our patient is likely nearing the end of her life because of end-stage dementia. There is no evidence to suggest placement of a feeding tube would extend her life more than hand feeding.

We know feeding-tube placement could increase aspiration pneumonia risk and significant short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. We can keep her comfortable with small amounts of water, wetting her lips with swabs. If a feeding tube is placed, its use should be evaluated based on the patient’s clinical course. TH

Dr. Pell is an instructor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver.

References

- Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15(6):872-875.

- Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, and Evans DA. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:169-173.

- Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Brody JA. Gastrostomy placement and mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 1998;279:1973-1976.

- Finocchiaro C, Galletti R, Rovera G, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a long-term follow-up. Nutrition. 1997;13(6):520-523.

- Leibovitz A, Plotnikov G, Habot B, et al. Pathogenic colonization of oral flora in frail elderly patients fed by nasogastric tube or percutaneous enterogastric tube. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2003;58(1):52-55.

- McCann R. Lack of evidence about tube feeding: food for thought. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1380-1381.

- Cameron JL, Caldini P, Toung J-K, et al. Aspiration pneumonia: physiologic data following experimental Aspiration. Surgery. 1972;72:238.

- Loeb MB, Becker M, Eady A, et al. Interventions to prevent aspiration pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review. JAGS. 2003;51(7):1018-1022.

- Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:327-332.

- McCann RM, Hall WJ, Groth-Junker A. Comfort care for terminally ill patients: the appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA. 1994;272:1263-1266.

- Rabeneck L, McCullough LB. Ethically justified, clinically comprehensive guidelines for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Lancet. 1997;349(9050):496-498.

Case

A 68-year-old cachectic female with a history of Alzheimer’s dementia presents with a slowly progressive decline in functional status. She is bed bound, minimally verbal, and has lost interest in eating.

Her problems with decreased oral intake started when her diet was changed to nectar-thickened liquids. This change was made after the patient was hospitalized multiple times for aspiration pneumonia and she underwent a fluoroscopic swallowing evaluation that revealed aspiration of thin liquids. The patient’s husband requests that a feeding tube be placed so his wife doesn’t “die of pneumonia or starve to death.”

Overview

As the U.S. population ages, hospitalists are seeing a steady increase in the average patient age and the prevalence of dementia. Alzheimer’s dementia affects an estimated 4 million to 5 million Americans; this number expected to triple by the year 2050.1

As patients with dementia near the end of life, they often fail to thrive, with less oral intake and more swallowing disorders leading to aspiration. This is when physicians and patient family members must decide whether a feeding tube should be placed.

Placement of a nasogastric or percutaneous endogastric gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube has become a relatively common medical intervention instituted to maintain or improve a patient’s nutritional status. Prior to 1980, permanent gastric or postpyloric feeding tubes were placed surgically by laparotomy, but the advent of endoscopy and computed tomography (CT) guided procedures offers a simplified procedure requiring only mild sedation and local anesthesia.2

Many patients who suffer multiple bouts of aspiration pneumonia and fail a swallowing evaluation because of an irreversible process are offered a percutaneous feeding tube to maintain nutrition. A feeding tube is also seen as a way to supply nutrition at the end of life in patients no longer able or willing to take food orally.

Although it seems logical that a feeding tube might improve the outcomes of these clinical scenarios, limited literature exists on the topic because of the legal, ethical, emotional, and religious implications a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial would entail.

Review of the Data

Placement of a PEG has become accepted as a relatively benign procedure, although it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Minor complications including pain, abdominal wall ulcers, wound infections, peristomal leakage, and tube displacement occur in approximately 10% of cases.3 Major complications including hemorrhage, bowel or liver perforation, or aspiration occur in 3% of cases.4

These numbers do not account for long-term complications including peristomal infections, leakage problems, or the use of physical restraints to avoid self-extubation.

Aspiration Risk