User login

Updated ACCP Guideline for Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients. Although it is well-known that anticoagulation therapy is effective in the prevention and treatment of VTE events, these agents are some of the highest-risk medications a hospitalist will prescribe given the danger of major bleeding. With the recent approval of several newer anticoagulants, it is important for the practicing hospitalist to be comfortable initiating, maintaining, and stopping these agents in a wide variety of patient populations.

Guideline Updates

In February 2016, an update to the ninth edition of the antithrombotic guideline from the American College of Chest Physician (ACCP) was published and included updated recommendations on 12 topics in addition to three new topics. This 10th-edition guideline update is referred to as AT10.1

One of the most notable changes in the updated guideline is the recommended choice of anticoagulant in patients with acute DVT or PE without cancer. Now, the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban are recommended over warfarin. Although this is a weak recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence (grade 2B), this is the first time that warfarin is not considered first-line therapy. It should be emphasized that none of the four FDA-approved DOACs are preferred over another, and they should be avoided in patients who are pregnant or have severe renal disease. In patients with DVT or PE and cancer, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is still the preferred medication. If LMWH is not prescribed, AT10 does not have a preference for either a DOAC or warfarin for patients with cancer.

When it comes to duration of anticoagulation following a VTE event, the updated guideline continues to recommend three months for a provoked VTE event, with consideration for lifelong anticoagulation for an unprovoked event for patients at low or moderate bleeding risk. However, it now suggests that the recurrence risk factors of male sex and a positive D-dimer measured one month after stopping anticoagulant therapy should be taken into consideration when deciding whether extended anticoagulation is indicated.

AT10 also includes new recommendations concerning the role of aspirin for extended VTE treatment. Interestingly, the 2008 ACCP guideline gave a strong recommendation against the use of aspirin for VTE management in any patient population. In the 2012 guideline, the role of aspirin was not addressed for VTE treatment. Now, AT10 states that low-dose aspirin can be used in patients who stop anticoagulant therapy for treatment of an unprovoked proximal DVT or PE as an extended therapy (grade 2B). The significant change in this recommendation stems from two recent randomized trials that compared aspirin with placebo for the prevention of VTE recurrence in patients who have completed a course of anticoagulation for a first unprovoked proximal DVT or PE.2,3 Although the guideline doesn’t consider aspirin to be a reasonable alternative to anticoagulation for patients who require extended therapy and are agreeable to continue, for patients who have decided to stop anticoagulation, aspirin appears to reduce recurrent VTE by approximately one-third, with no significant increased risk of bleeding.

Another significant change in AT10 is the recommendation against the routine use of compression stockings to prevent postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). This change was influenced by a recent multicenter randomized trial showing that elastic compression stockings did not prevent PTS after an acute proximal DVT.4 The guideline authors remark that this recommendation focuses on the prevention of the chronic complications of PTS rather than treatment of the symptoms. Thus, for patients with acute or chronic leg pain or swelling from DVT, compression stockings may be justified.

A topic that was not addressed in the previous guideline was whether patients with a subsegmental PE should be treated. The guideline now suggests that patients with only subsegmental PE and no ultrasound-proven proximal DVT of the legs should undergo “clinical surveillance” rather than anticoagulation (grade 2C). Exceptions include patients at high risk for recurrent VTE (e.g., hospitalization, reduced mobility, active cancer, or irreversible VTE risk factors) and those with a low cardiopulmonary reserve or marked symptoms thought to be from PE. AT10 also states that patient preferences regarding anticoagulation treatment as well as the patient’s risk of bleeding should be taken into consideration. If the decision is made to not prescribe anticoagulation for subsegmental PE, patients should be advised to seek reevaluation if their symptoms persist or worsen.

The 2012 guideline included a new recommendation that patients with low-risk PE (typically defined by a low Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index [PESI] score) could be discharged “early” from the hospital. This recommendation has now been modified to state that patients with low-risk PE may be treated entirely at home. It is worth noting that outpatient management of low-risk PE has become much less complicated if using a DOAC, particularly rivaroxaban and apixaban as neither require initial treatment with parenteral anticoagulation.

AT10 has not changed the recommendation for which patients should receive thrombolytic therapy for treatment of PE. It recommends systemic thrombolytic therapy for patients with acute PE associated with hypotension (defined as systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg for 15 minutes) who are not at high risk for bleeding (grade 2B). Likewise, for patients with acute PE not associated with hypotension, the guideline recommends against systemic thrombolytics (grade 1B). If thrombolytics are implemented, AT10 favors systemic administration over catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) due to the higher-quality evidence available. However, the authors state that CDT may be preferred for patients at higher risk of bleeding and when local expertise is available. Lastly, catheter-assisted thrombus removal should be considered in patients with acute PE and hypotension who have a high bleeding risk, who have failed systemic thrombolytics, or who are in shock and likely to die before systemic thrombolytics become therapeutic.

Although no prospective trials have evaluated the management of patients with recurrent VTE events while on anticoagulation therapy, AT10 offers some guidance. After ensuring the patient truly had a recurrent VTE event while on therapeutic warfarin or compliant with a DOAC, the authors suggest switching to LMWH for at least one month (grade 2C). Furthermore, for patients who have a recurrent VTE event while compliant on long-term LMWH, the guideline suggests increasing the dose of LMWH by about one-quarter to one-third (grade 2C).

Guideline Analysis

It is important to note that of the 54 recommendations included in the complete guideline update, only 20 were strong recommendations (grade 1), and none were based on high-quality evidence (level A). It is obvious that more research is needed in this field. Regardless, the ACCP antithrombotic guideline remains the authoritative source in VTE management and has a strong influence on practice behavior. With the recent addition of several newer anticoagulants, AT10 is particularly useful in helping providers understand when and when not to use them. The authors indicate that future iterations will be continually updated, describing them as “living guidelines.” The format of AT10 was designed to facilitate this method with the goal of having discrete topics discussed as new evidence becomes available.

Hospital Medicine Takeaways

Despite the lack of randomized and prospective clinical trials, the updated recommendations from AT10 provide important information on challenging VTE issues that the hospitalist can apply to most patients most of the time. Important updates include:

- Prescribe DOACs as first-line agents for the treatment of acute VTE in patients without cancer.

- Use aspirin for the prevention of recurrent VTE in patients who stop anticoagulation for treatment of an unprovoked DVT or PE.

- Avoid compression stockings for the sole purpose of preventing postthrombotic syndrome.

- Do not admit patients with low-risk PE (as determined by the PESI score) to the hospital but rather treat them entirely at home.

Lastly, it is important to remember that VTE treatment decisions need to be individualized based on the clinical, imaging, and biochemical features of your patient.

Paul J. Grant, MD, SFHM, is assistant professor of medicine and director of perioperative and consultative medicine within the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

References

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

- Brighton TA, Eikelboom JW, Mann K, et al. Low-dose aspirin for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1979-1987.

- Becattini C, Agnelli G, Schenone A, et al. Aspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1959-1967.

- Kahn SR, Shapiro S, Wells PS, et al. Compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):880-888.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients. Although it is well-known that anticoagulation therapy is effective in the prevention and treatment of VTE events, these agents are some of the highest-risk medications a hospitalist will prescribe given the danger of major bleeding. With the recent approval of several newer anticoagulants, it is important for the practicing hospitalist to be comfortable initiating, maintaining, and stopping these agents in a wide variety of patient populations.

Guideline Updates

In February 2016, an update to the ninth edition of the antithrombotic guideline from the American College of Chest Physician (ACCP) was published and included updated recommendations on 12 topics in addition to three new topics. This 10th-edition guideline update is referred to as AT10.1

One of the most notable changes in the updated guideline is the recommended choice of anticoagulant in patients with acute DVT or PE without cancer. Now, the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban are recommended over warfarin. Although this is a weak recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence (grade 2B), this is the first time that warfarin is not considered first-line therapy. It should be emphasized that none of the four FDA-approved DOACs are preferred over another, and they should be avoided in patients who are pregnant or have severe renal disease. In patients with DVT or PE and cancer, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is still the preferred medication. If LMWH is not prescribed, AT10 does not have a preference for either a DOAC or warfarin for patients with cancer.

When it comes to duration of anticoagulation following a VTE event, the updated guideline continues to recommend three months for a provoked VTE event, with consideration for lifelong anticoagulation for an unprovoked event for patients at low or moderate bleeding risk. However, it now suggests that the recurrence risk factors of male sex and a positive D-dimer measured one month after stopping anticoagulant therapy should be taken into consideration when deciding whether extended anticoagulation is indicated.

AT10 also includes new recommendations concerning the role of aspirin for extended VTE treatment. Interestingly, the 2008 ACCP guideline gave a strong recommendation against the use of aspirin for VTE management in any patient population. In the 2012 guideline, the role of aspirin was not addressed for VTE treatment. Now, AT10 states that low-dose aspirin can be used in patients who stop anticoagulant therapy for treatment of an unprovoked proximal DVT or PE as an extended therapy (grade 2B). The significant change in this recommendation stems from two recent randomized trials that compared aspirin with placebo for the prevention of VTE recurrence in patients who have completed a course of anticoagulation for a first unprovoked proximal DVT or PE.2,3 Although the guideline doesn’t consider aspirin to be a reasonable alternative to anticoagulation for patients who require extended therapy and are agreeable to continue, for patients who have decided to stop anticoagulation, aspirin appears to reduce recurrent VTE by approximately one-third, with no significant increased risk of bleeding.

Another significant change in AT10 is the recommendation against the routine use of compression stockings to prevent postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). This change was influenced by a recent multicenter randomized trial showing that elastic compression stockings did not prevent PTS after an acute proximal DVT.4 The guideline authors remark that this recommendation focuses on the prevention of the chronic complications of PTS rather than treatment of the symptoms. Thus, for patients with acute or chronic leg pain or swelling from DVT, compression stockings may be justified.

A topic that was not addressed in the previous guideline was whether patients with a subsegmental PE should be treated. The guideline now suggests that patients with only subsegmental PE and no ultrasound-proven proximal DVT of the legs should undergo “clinical surveillance” rather than anticoagulation (grade 2C). Exceptions include patients at high risk for recurrent VTE (e.g., hospitalization, reduced mobility, active cancer, or irreversible VTE risk factors) and those with a low cardiopulmonary reserve or marked symptoms thought to be from PE. AT10 also states that patient preferences regarding anticoagulation treatment as well as the patient’s risk of bleeding should be taken into consideration. If the decision is made to not prescribe anticoagulation for subsegmental PE, patients should be advised to seek reevaluation if their symptoms persist or worsen.

The 2012 guideline included a new recommendation that patients with low-risk PE (typically defined by a low Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index [PESI] score) could be discharged “early” from the hospital. This recommendation has now been modified to state that patients with low-risk PE may be treated entirely at home. It is worth noting that outpatient management of low-risk PE has become much less complicated if using a DOAC, particularly rivaroxaban and apixaban as neither require initial treatment with parenteral anticoagulation.

AT10 has not changed the recommendation for which patients should receive thrombolytic therapy for treatment of PE. It recommends systemic thrombolytic therapy for patients with acute PE associated with hypotension (defined as systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg for 15 minutes) who are not at high risk for bleeding (grade 2B). Likewise, for patients with acute PE not associated with hypotension, the guideline recommends against systemic thrombolytics (grade 1B). If thrombolytics are implemented, AT10 favors systemic administration over catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) due to the higher-quality evidence available. However, the authors state that CDT may be preferred for patients at higher risk of bleeding and when local expertise is available. Lastly, catheter-assisted thrombus removal should be considered in patients with acute PE and hypotension who have a high bleeding risk, who have failed systemic thrombolytics, or who are in shock and likely to die before systemic thrombolytics become therapeutic.

Although no prospective trials have evaluated the management of patients with recurrent VTE events while on anticoagulation therapy, AT10 offers some guidance. After ensuring the patient truly had a recurrent VTE event while on therapeutic warfarin or compliant with a DOAC, the authors suggest switching to LMWH for at least one month (grade 2C). Furthermore, for patients who have a recurrent VTE event while compliant on long-term LMWH, the guideline suggests increasing the dose of LMWH by about one-quarter to one-third (grade 2C).

Guideline Analysis

It is important to note that of the 54 recommendations included in the complete guideline update, only 20 were strong recommendations (grade 1), and none were based on high-quality evidence (level A). It is obvious that more research is needed in this field. Regardless, the ACCP antithrombotic guideline remains the authoritative source in VTE management and has a strong influence on practice behavior. With the recent addition of several newer anticoagulants, AT10 is particularly useful in helping providers understand when and when not to use them. The authors indicate that future iterations will be continually updated, describing them as “living guidelines.” The format of AT10 was designed to facilitate this method with the goal of having discrete topics discussed as new evidence becomes available.

Hospital Medicine Takeaways

Despite the lack of randomized and prospective clinical trials, the updated recommendations from AT10 provide important information on challenging VTE issues that the hospitalist can apply to most patients most of the time. Important updates include:

- Prescribe DOACs as first-line agents for the treatment of acute VTE in patients without cancer.

- Use aspirin for the prevention of recurrent VTE in patients who stop anticoagulation for treatment of an unprovoked DVT or PE.

- Avoid compression stockings for the sole purpose of preventing postthrombotic syndrome.

- Do not admit patients with low-risk PE (as determined by the PESI score) to the hospital but rather treat them entirely at home.

Lastly, it is important to remember that VTE treatment decisions need to be individualized based on the clinical, imaging, and biochemical features of your patient.

Paul J. Grant, MD, SFHM, is assistant professor of medicine and director of perioperative and consultative medicine within the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

References

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

- Brighton TA, Eikelboom JW, Mann K, et al. Low-dose aspirin for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1979-1987.

- Becattini C, Agnelli G, Schenone A, et al. Aspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1959-1967.

- Kahn SR, Shapiro S, Wells PS, et al. Compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):880-888.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients. Although it is well-known that anticoagulation therapy is effective in the prevention and treatment of VTE events, these agents are some of the highest-risk medications a hospitalist will prescribe given the danger of major bleeding. With the recent approval of several newer anticoagulants, it is important for the practicing hospitalist to be comfortable initiating, maintaining, and stopping these agents in a wide variety of patient populations.

Guideline Updates

In February 2016, an update to the ninth edition of the antithrombotic guideline from the American College of Chest Physician (ACCP) was published and included updated recommendations on 12 topics in addition to three new topics. This 10th-edition guideline update is referred to as AT10.1

One of the most notable changes in the updated guideline is the recommended choice of anticoagulant in patients with acute DVT or PE without cancer. Now, the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban are recommended over warfarin. Although this is a weak recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence (grade 2B), this is the first time that warfarin is not considered first-line therapy. It should be emphasized that none of the four FDA-approved DOACs are preferred over another, and they should be avoided in patients who are pregnant or have severe renal disease. In patients with DVT or PE and cancer, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is still the preferred medication. If LMWH is not prescribed, AT10 does not have a preference for either a DOAC or warfarin for patients with cancer.

When it comes to duration of anticoagulation following a VTE event, the updated guideline continues to recommend three months for a provoked VTE event, with consideration for lifelong anticoagulation for an unprovoked event for patients at low or moderate bleeding risk. However, it now suggests that the recurrence risk factors of male sex and a positive D-dimer measured one month after stopping anticoagulant therapy should be taken into consideration when deciding whether extended anticoagulation is indicated.

AT10 also includes new recommendations concerning the role of aspirin for extended VTE treatment. Interestingly, the 2008 ACCP guideline gave a strong recommendation against the use of aspirin for VTE management in any patient population. In the 2012 guideline, the role of aspirin was not addressed for VTE treatment. Now, AT10 states that low-dose aspirin can be used in patients who stop anticoagulant therapy for treatment of an unprovoked proximal DVT or PE as an extended therapy (grade 2B). The significant change in this recommendation stems from two recent randomized trials that compared aspirin with placebo for the prevention of VTE recurrence in patients who have completed a course of anticoagulation for a first unprovoked proximal DVT or PE.2,3 Although the guideline doesn’t consider aspirin to be a reasonable alternative to anticoagulation for patients who require extended therapy and are agreeable to continue, for patients who have decided to stop anticoagulation, aspirin appears to reduce recurrent VTE by approximately one-third, with no significant increased risk of bleeding.

Another significant change in AT10 is the recommendation against the routine use of compression stockings to prevent postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). This change was influenced by a recent multicenter randomized trial showing that elastic compression stockings did not prevent PTS after an acute proximal DVT.4 The guideline authors remark that this recommendation focuses on the prevention of the chronic complications of PTS rather than treatment of the symptoms. Thus, for patients with acute or chronic leg pain or swelling from DVT, compression stockings may be justified.

A topic that was not addressed in the previous guideline was whether patients with a subsegmental PE should be treated. The guideline now suggests that patients with only subsegmental PE and no ultrasound-proven proximal DVT of the legs should undergo “clinical surveillance” rather than anticoagulation (grade 2C). Exceptions include patients at high risk for recurrent VTE (e.g., hospitalization, reduced mobility, active cancer, or irreversible VTE risk factors) and those with a low cardiopulmonary reserve or marked symptoms thought to be from PE. AT10 also states that patient preferences regarding anticoagulation treatment as well as the patient’s risk of bleeding should be taken into consideration. If the decision is made to not prescribe anticoagulation for subsegmental PE, patients should be advised to seek reevaluation if their symptoms persist or worsen.

The 2012 guideline included a new recommendation that patients with low-risk PE (typically defined by a low Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index [PESI] score) could be discharged “early” from the hospital. This recommendation has now been modified to state that patients with low-risk PE may be treated entirely at home. It is worth noting that outpatient management of low-risk PE has become much less complicated if using a DOAC, particularly rivaroxaban and apixaban as neither require initial treatment with parenteral anticoagulation.

AT10 has not changed the recommendation for which patients should receive thrombolytic therapy for treatment of PE. It recommends systemic thrombolytic therapy for patients with acute PE associated with hypotension (defined as systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg for 15 minutes) who are not at high risk for bleeding (grade 2B). Likewise, for patients with acute PE not associated with hypotension, the guideline recommends against systemic thrombolytics (grade 1B). If thrombolytics are implemented, AT10 favors systemic administration over catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) due to the higher-quality evidence available. However, the authors state that CDT may be preferred for patients at higher risk of bleeding and when local expertise is available. Lastly, catheter-assisted thrombus removal should be considered in patients with acute PE and hypotension who have a high bleeding risk, who have failed systemic thrombolytics, or who are in shock and likely to die before systemic thrombolytics become therapeutic.

Although no prospective trials have evaluated the management of patients with recurrent VTE events while on anticoagulation therapy, AT10 offers some guidance. After ensuring the patient truly had a recurrent VTE event while on therapeutic warfarin or compliant with a DOAC, the authors suggest switching to LMWH for at least one month (grade 2C). Furthermore, for patients who have a recurrent VTE event while compliant on long-term LMWH, the guideline suggests increasing the dose of LMWH by about one-quarter to one-third (grade 2C).

Guideline Analysis

It is important to note that of the 54 recommendations included in the complete guideline update, only 20 were strong recommendations (grade 1), and none were based on high-quality evidence (level A). It is obvious that more research is needed in this field. Regardless, the ACCP antithrombotic guideline remains the authoritative source in VTE management and has a strong influence on practice behavior. With the recent addition of several newer anticoagulants, AT10 is particularly useful in helping providers understand when and when not to use them. The authors indicate that future iterations will be continually updated, describing them as “living guidelines.” The format of AT10 was designed to facilitate this method with the goal of having discrete topics discussed as new evidence becomes available.

Hospital Medicine Takeaways

Despite the lack of randomized and prospective clinical trials, the updated recommendations from AT10 provide important information on challenging VTE issues that the hospitalist can apply to most patients most of the time. Important updates include:

- Prescribe DOACs as first-line agents for the treatment of acute VTE in patients without cancer.

- Use aspirin for the prevention of recurrent VTE in patients who stop anticoagulation for treatment of an unprovoked DVT or PE.

- Avoid compression stockings for the sole purpose of preventing postthrombotic syndrome.

- Do not admit patients with low-risk PE (as determined by the PESI score) to the hospital but rather treat them entirely at home.

Lastly, it is important to remember that VTE treatment decisions need to be individualized based on the clinical, imaging, and biochemical features of your patient.

Paul J. Grant, MD, SFHM, is assistant professor of medicine and director of perioperative and consultative medicine within the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

References

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352.

- Brighton TA, Eikelboom JW, Mann K, et al. Low-dose aspirin for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1979-1987.

- Becattini C, Agnelli G, Schenone A, et al. Aspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1959-1967.

- Kahn SR, Shapiro S, Wells PS, et al. Compression stockings to prevent post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):880-888.

ASTRO guidelines lower age thresholds for APBI

The American Society for Radiation Oncology has issued new guidelines recommending accelerated partial breast irradiation brachytherapy (APBI) as an alternative to whole breast irradiation (WBI) after surgery in early-stage breast cancer patients, and lowering the age range of patients considered suitable for the procedure to people 50 and older, from 60.

With APBI, localized radiation is delivered to the region around the excised tissue, reducing treatment time and sparing healthy tissue. APBI may also be considered for patients 40 and older, according to ASTRO, if they meet all of the pathologic criteria for suitability listed in the guidelines for patients 50 and above.

The guidelines represent the first ASTRO update on APBI since 2009. In addition to expanding the age range for APBI treatment, the guidelines add low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ as an indication. The guidelines also address intraoperative radiation therapy, or IORT, in which patients receive low-energy photon or electron radiation during surgery (Pract Rad Oncol. 2016 Nov. 17 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.09.007).

While IORT is suitable for patients with invasive cancer eligible for APBI, the guidelines say, patients considering this option should be counseled about the risk of recurrence compared with standard treatment, and, with photon IORT, about potential toxicity risk requiring follow-up. Though more than 40 studies were considered by the ASTRO committee, including large randomized trials comparing APBI with WBI, the new recommendations represent “more of a tweak than a revolution,” said Jay Harris, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, one of the guideline authors.

Dr. Harris noted in an interview that two important randomized controlled trials comparing APBI and WBI are still underway, with full follow-up results expected in 2-3 years, after which more definitive recommendations can be made. For the intraoperative radiation advice contained in the guidelines, “we had evidence from two trials looking at different approaches,” Dr. Harris said. “One has long-term data using an electron beam in the operating room – this group showed that that approach seems reasonable in patients that we at ASTRO considered suitable in general for APBI. The other approach is low-dose photon radiation, for which we have only short-term follow-up, making us more hesitant to endorse it.” As for the new recommendation sanctioning APBI for ductal carcinoma, “There’s a lot of variation [in protocols] across the country, compared with invasive cancer,” Dr. Harris said. “We’re kind of all over the map with DCIS. This guideline presents another option.”

The guidelines were sponsored by ASTRO; two authors disclosed financial relationships with firms that make radiologic technology.

The American Society for Radiation Oncology has issued new guidelines recommending accelerated partial breast irradiation brachytherapy (APBI) as an alternative to whole breast irradiation (WBI) after surgery in early-stage breast cancer patients, and lowering the age range of patients considered suitable for the procedure to people 50 and older, from 60.

With APBI, localized radiation is delivered to the region around the excised tissue, reducing treatment time and sparing healthy tissue. APBI may also be considered for patients 40 and older, according to ASTRO, if they meet all of the pathologic criteria for suitability listed in the guidelines for patients 50 and above.

The guidelines represent the first ASTRO update on APBI since 2009. In addition to expanding the age range for APBI treatment, the guidelines add low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ as an indication. The guidelines also address intraoperative radiation therapy, or IORT, in which patients receive low-energy photon or electron radiation during surgery (Pract Rad Oncol. 2016 Nov. 17 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.09.007).

While IORT is suitable for patients with invasive cancer eligible for APBI, the guidelines say, patients considering this option should be counseled about the risk of recurrence compared with standard treatment, and, with photon IORT, about potential toxicity risk requiring follow-up. Though more than 40 studies were considered by the ASTRO committee, including large randomized trials comparing APBI with WBI, the new recommendations represent “more of a tweak than a revolution,” said Jay Harris, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, one of the guideline authors.

Dr. Harris noted in an interview that two important randomized controlled trials comparing APBI and WBI are still underway, with full follow-up results expected in 2-3 years, after which more definitive recommendations can be made. For the intraoperative radiation advice contained in the guidelines, “we had evidence from two trials looking at different approaches,” Dr. Harris said. “One has long-term data using an electron beam in the operating room – this group showed that that approach seems reasonable in patients that we at ASTRO considered suitable in general for APBI. The other approach is low-dose photon radiation, for which we have only short-term follow-up, making us more hesitant to endorse it.” As for the new recommendation sanctioning APBI for ductal carcinoma, “There’s a lot of variation [in protocols] across the country, compared with invasive cancer,” Dr. Harris said. “We’re kind of all over the map with DCIS. This guideline presents another option.”

The guidelines were sponsored by ASTRO; two authors disclosed financial relationships with firms that make radiologic technology.

The American Society for Radiation Oncology has issued new guidelines recommending accelerated partial breast irradiation brachytherapy (APBI) as an alternative to whole breast irradiation (WBI) after surgery in early-stage breast cancer patients, and lowering the age range of patients considered suitable for the procedure to people 50 and older, from 60.

With APBI, localized radiation is delivered to the region around the excised tissue, reducing treatment time and sparing healthy tissue. APBI may also be considered for patients 40 and older, according to ASTRO, if they meet all of the pathologic criteria for suitability listed in the guidelines for patients 50 and above.

The guidelines represent the first ASTRO update on APBI since 2009. In addition to expanding the age range for APBI treatment, the guidelines add low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ as an indication. The guidelines also address intraoperative radiation therapy, or IORT, in which patients receive low-energy photon or electron radiation during surgery (Pract Rad Oncol. 2016 Nov. 17 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.09.007).

While IORT is suitable for patients with invasive cancer eligible for APBI, the guidelines say, patients considering this option should be counseled about the risk of recurrence compared with standard treatment, and, with photon IORT, about potential toxicity risk requiring follow-up. Though more than 40 studies were considered by the ASTRO committee, including large randomized trials comparing APBI with WBI, the new recommendations represent “more of a tweak than a revolution,” said Jay Harris, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, one of the guideline authors.

Dr. Harris noted in an interview that two important randomized controlled trials comparing APBI and WBI are still underway, with full follow-up results expected in 2-3 years, after which more definitive recommendations can be made. For the intraoperative radiation advice contained in the guidelines, “we had evidence from two trials looking at different approaches,” Dr. Harris said. “One has long-term data using an electron beam in the operating room – this group showed that that approach seems reasonable in patients that we at ASTRO considered suitable in general for APBI. The other approach is low-dose photon radiation, for which we have only short-term follow-up, making us more hesitant to endorse it.” As for the new recommendation sanctioning APBI for ductal carcinoma, “There’s a lot of variation [in protocols] across the country, compared with invasive cancer,” Dr. Harris said. “We’re kind of all over the map with DCIS. This guideline presents another option.”

The guidelines were sponsored by ASTRO; two authors disclosed financial relationships with firms that make radiologic technology.

FROM PRACTICAL RADIATION ONCOLOGY

NCCN: Deliver vincristine by mini IV drip bag

Always dilute chemotherapy agent vincristine and administer it by mini IV-drip bag, instead of syringe, urges the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in a new campaign.

The goal of “Just Bag It” is to prevent a rare but uniformly fatal medical error – administering vincristine to the spinal fluid. When syringes are side by side – one with vincristine for IV push, another with a chemotherapeutic agent meant for push into the spinal fluid – it is just too easy to make a mistake. When administered intrathecally, vincristine causes ascending paralysis, neurological defects, and eventually death.

Despite all the warning labels and checks, “this still happens,” Marc Stewart, MD, cochair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Best Practices Committee, as well as medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance and professor of medicine at the University of Washington, said at a press conference.

Mini IV-drip bag administration will make it “virtually impossible. No physician would hook the bag up to a needle in someone’s spine” and even if they did, there wouldn’t be enough pressure in the bag to push vincristine in, he said.

The group has encouraged drip-bag delivery of vincristine for years, but only about half of hospitals have adopted the policy. The mistake happens so rarely – about 125 cases since the 1960s – “that the motivation for change is just not there.” Until somebody like NCCN calls it out in a high-profile campaign, “it’s not high on the radar screen,” Dr. Stewart said. It should be a relatively easy fix because bagging vincristine is not more costly. In general, the cost difference versus syringe “is going to be pennies,” he said.

“We challenge all medical centers, hospitals, and oncology practices around the nation and the world to implement this medication safety policy so this error never occurs again,” NCCN Chief Executive Officer Robert Carlson, MD, said in a press release. A medical oncologist, he witnessed the death of a 21-year-old patient after an intrathecal vincristine injection in 2005.

“Some health care providers may associate the use of an IV bag with a heightened risk of extravasation, but research shows that the risk of extravasation is extremely low (less than 0.05%) regardless of how vincristine is administered,” the press release noted.

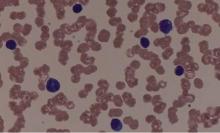

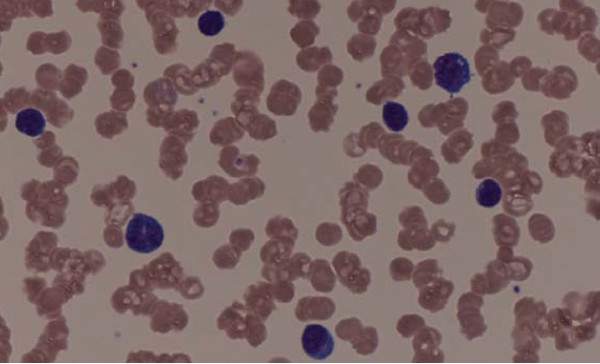

Vincristine is widely used in treating patients with leukemia or lymphoma.

The safety of intravenous administration of vincristine has been a long-standing concern for anyone who participates in the management of patients with hematologic malignancies. As we all know, accidental intrathecal administration of vincristine is uniformly fatal.

At many centers, including ours, policies related to intravenous infusion of vesicants via a peripheral line have made the implementation of the safety recommendations difficult. It is not surprising that only 50% of hospitals surveyed by NCCN have fully implemented the mini-bag recommendation given the concern for extravasation. However, the newest ONS guidelines for vesicant administration allow for short-term infusions via a peripheral line. For our center, this support has been instrumental in allowing us to move to a practice with the recommended mini-bags. The NCCN “Just Bag It” campaign will likely help to move institutions such as ours to be in compliance with this important safety initiative.

Donna Capozzi, PharmD, is associate director of ambulatory services in the department of pharmacy at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia. She is on the editorial advisory board of Hematology News, a publication of this news company.

The safety of intravenous administration of vincristine has been a long-standing concern for anyone who participates in the management of patients with hematologic malignancies. As we all know, accidental intrathecal administration of vincristine is uniformly fatal.

At many centers, including ours, policies related to intravenous infusion of vesicants via a peripheral line have made the implementation of the safety recommendations difficult. It is not surprising that only 50% of hospitals surveyed by NCCN have fully implemented the mini-bag recommendation given the concern for extravasation. However, the newest ONS guidelines for vesicant administration allow for short-term infusions via a peripheral line. For our center, this support has been instrumental in allowing us to move to a practice with the recommended mini-bags. The NCCN “Just Bag It” campaign will likely help to move institutions such as ours to be in compliance with this important safety initiative.

Donna Capozzi, PharmD, is associate director of ambulatory services in the department of pharmacy at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia. She is on the editorial advisory board of Hematology News, a publication of this news company.

The safety of intravenous administration of vincristine has been a long-standing concern for anyone who participates in the management of patients with hematologic malignancies. As we all know, accidental intrathecal administration of vincristine is uniformly fatal.

At many centers, including ours, policies related to intravenous infusion of vesicants via a peripheral line have made the implementation of the safety recommendations difficult. It is not surprising that only 50% of hospitals surveyed by NCCN have fully implemented the mini-bag recommendation given the concern for extravasation. However, the newest ONS guidelines for vesicant administration allow for short-term infusions via a peripheral line. For our center, this support has been instrumental in allowing us to move to a practice with the recommended mini-bags. The NCCN “Just Bag It” campaign will likely help to move institutions such as ours to be in compliance with this important safety initiative.

Donna Capozzi, PharmD, is associate director of ambulatory services in the department of pharmacy at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine in Philadelphia. She is on the editorial advisory board of Hematology News, a publication of this news company.

Always dilute chemotherapy agent vincristine and administer it by mini IV-drip bag, instead of syringe, urges the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in a new campaign.

The goal of “Just Bag It” is to prevent a rare but uniformly fatal medical error – administering vincristine to the spinal fluid. When syringes are side by side – one with vincristine for IV push, another with a chemotherapeutic agent meant for push into the spinal fluid – it is just too easy to make a mistake. When administered intrathecally, vincristine causes ascending paralysis, neurological defects, and eventually death.

Despite all the warning labels and checks, “this still happens,” Marc Stewart, MD, cochair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Best Practices Committee, as well as medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance and professor of medicine at the University of Washington, said at a press conference.

Mini IV-drip bag administration will make it “virtually impossible. No physician would hook the bag up to a needle in someone’s spine” and even if they did, there wouldn’t be enough pressure in the bag to push vincristine in, he said.

The group has encouraged drip-bag delivery of vincristine for years, but only about half of hospitals have adopted the policy. The mistake happens so rarely – about 125 cases since the 1960s – “that the motivation for change is just not there.” Until somebody like NCCN calls it out in a high-profile campaign, “it’s not high on the radar screen,” Dr. Stewart said. It should be a relatively easy fix because bagging vincristine is not more costly. In general, the cost difference versus syringe “is going to be pennies,” he said.

“We challenge all medical centers, hospitals, and oncology practices around the nation and the world to implement this medication safety policy so this error never occurs again,” NCCN Chief Executive Officer Robert Carlson, MD, said in a press release. A medical oncologist, he witnessed the death of a 21-year-old patient after an intrathecal vincristine injection in 2005.

“Some health care providers may associate the use of an IV bag with a heightened risk of extravasation, but research shows that the risk of extravasation is extremely low (less than 0.05%) regardless of how vincristine is administered,” the press release noted.

Vincristine is widely used in treating patients with leukemia or lymphoma.

Always dilute chemotherapy agent vincristine and administer it by mini IV-drip bag, instead of syringe, urges the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in a new campaign.

The goal of “Just Bag It” is to prevent a rare but uniformly fatal medical error – administering vincristine to the spinal fluid. When syringes are side by side – one with vincristine for IV push, another with a chemotherapeutic agent meant for push into the spinal fluid – it is just too easy to make a mistake. When administered intrathecally, vincristine causes ascending paralysis, neurological defects, and eventually death.

Despite all the warning labels and checks, “this still happens,” Marc Stewart, MD, cochair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Best Practices Committee, as well as medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance and professor of medicine at the University of Washington, said at a press conference.

Mini IV-drip bag administration will make it “virtually impossible. No physician would hook the bag up to a needle in someone’s spine” and even if they did, there wouldn’t be enough pressure in the bag to push vincristine in, he said.

The group has encouraged drip-bag delivery of vincristine for years, but only about half of hospitals have adopted the policy. The mistake happens so rarely – about 125 cases since the 1960s – “that the motivation for change is just not there.” Until somebody like NCCN calls it out in a high-profile campaign, “it’s not high on the radar screen,” Dr. Stewart said. It should be a relatively easy fix because bagging vincristine is not more costly. In general, the cost difference versus syringe “is going to be pennies,” he said.

“We challenge all medical centers, hospitals, and oncology practices around the nation and the world to implement this medication safety policy so this error never occurs again,” NCCN Chief Executive Officer Robert Carlson, MD, said in a press release. A medical oncologist, he witnessed the death of a 21-year-old patient after an intrathecal vincristine injection in 2005.

“Some health care providers may associate the use of an IV bag with a heightened risk of extravasation, but research shows that the risk of extravasation is extremely low (less than 0.05%) regardless of how vincristine is administered,” the press release noted.

Vincristine is widely used in treating patients with leukemia or lymphoma.

Why Aren’t Doctors Following Guidelines?

One recent paper in Clinical Pediatrics, for example, chronicled low adherence to the 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute lipid screening guidelines in primary-care settings.1 Another cautioned providers to “mind the (implementation) gap” in venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients.2 A third found that lower adherence to guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for acute coronary syndrome patients was significantly associated with higher bleeding and mortality rates.3

Both clinical trials and real-world studies have demonstrated that when guidelines are applied, patients do better, says William Lewis, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and director of the Heart & Vascular Center at MetroHealth in Cleveland. So why aren’t they followed more consistently?

Experts in both HM and other disciplines cite multiple obstacles. Lack of evidence, conflicting evidence, or lack of awareness about evidence can all conspire against the main goal of helping providers deliver consistent high-value care, says Christopher Moriates, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“In our day-to-day lives as hospitalists, for the vast majority probably of what we do there’s no clear guideline or there’s a guideline that doesn’t necessarily apply to the patient standing in front of me,” he says.

Even when a guideline is clear and relevant, other doctors say inadequate dissemination and implementation can still derail quality improvement efforts.

“A lot of what we do as physicians is what we learned in residency, and to incorporate the new data is difficult,” says Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Feldman believes many doctors have yet to integrate recently revised hypertension and cholesterol guidelines into their practice, for example. Some guidelines have proven more complex or controversial, limiting their adoption.

“I know I struggle to keep up with all of the guidelines, and I’m in a big academic center where people are talking about them all the time, and I’m working with residents who are talking about them all the time,” Dr. Feldman says.

Despite the remaining gaps, however, many researchers agree that momentum has built steadily over the past two decades toward a more systematic approach to creating solid evidence-based guidelines and integrating them into real-world decision making.

Emphasis on Evidence and Transparency

The term “evidence-based medicine” was coined in 1990 by Gordon Guyatt, MD, MSc, FRCPC, distinguished professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. It’s played an active role in formulating guidelines for multiple organizations. The guideline-writing process, Dr. Guyatt says, once consisted of little more than self-selected clinicians sitting around a table.

“It used to be that a bunch of experts got together and decided and made the recommendations with very little in the way of a systematic process and certainly not evidence based,” he says.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center was among the pioneers pushing for a more systematic approach; the hospital began working on its own guidelines in 1995 and published the first of many the following year.

“We started evidence-based guidelines when the docs were still saying, ‘This is cookbook medicine. I don’t know if I want to do this or not,’” says Wendy Gerhardt, MSN, director of evidence-based decision making in the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s.

Some doctors also argued that clinical guidelines would stifle innovation, cramp their individual style, or intrude on their relationships with patients. Despite some lingering misgivings among clinicians, however, the process has gained considerable support. In 2000, an organization called the GRADE Working Group (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) began developing a new approach to raise the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

The group’s work led to a 2004 article in BMJ, and the journal subsequently published a six-part series about GRADE for clinicians.4 More recently, the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology also delved into the issue with a 15-part series detailing the GRADE methodology.5 Together, Dr. Guyatt says, the articles have become a go-to guide for guidelines and have helped solidify the focus on evidence.

Cincinnati Children’s and other institutions also have developed tools, and the Institute of Medicine has published guideline-writing standards.

“So it’s easier than it’s ever been to know whether or not you have a decent guideline in your hand,” Gerhardt says.

Likewise, medical organizations are more clearly explaining how they came up with different kinds of guidelines. Evidence-based and consensus guidelines aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, though consensus building is often used in the absence of high-quality evidence. Some organizations have limited the pool of evidence for guidelines to randomized controlled trial data.

“Unfortunately, for us in the real world, we actually have to make decisions even when there’s not enough data,” Dr. Feldman says.

Sometimes, the best available evidence may be observational studies, and some committees still try to reach a consensus based on that evidence and on the panelists’ professional opinions.

Dr. Guyatt agrees that it’s “absolutely not” true that evidence-based guidelines require randomized controlled trials. “What you need for any recommendation is a thorough review and summary of the best available evidence,” he says.

As part of each final document, Cincinnati Children’s details how it created the guideline, when the literature searches occurred, how the committee reached a consensus, and which panelists participated in the deliberations. The information, Gerhardt says, allows anyone else to “make some sensible decisions about whether or not it’s a guideline you want to use.”

Guideline-crafting institutions are also focusing more on the proper makeup of their panels. In general, Dr. Guyatt says, a panel with more than 10 people can be unwieldy. Guidelines that include many specific recommendations, however, may require multiple subsections, each with its own committee.

Dr. Guyatt is careful to note that, like many other experts, he has multiple potential conflicts of interest, such as working on the anti-thrombotic guidelines issued by the American College of Chest Physicians. Committees, he says, have become increasingly aware of how properly handling conflicts (financial or otherwise) can be critical in building and maintaining trust among clinicians and patients. One technique is to ensure that a diversity of opinions is reflected among a committee whose experts have various conflicts. If one expert’s company makes drug A, for example, then the committee also includes experts involved with drugs B or C. As an alternative, some committees have explicitly barred anyone with a conflict of interest from participating at all.

But experts often provide crucial input, Dr. Guyatt says, and several committees have adopted variations of a middle-ground approach. In an approach that he favors, all guideline-formulating panelists are conflict-free but begin their work by meeting with a separate group of experts who may have some conflicts but can help point out the main issues. The panelists then deliberate and write a draft of the recommendations, after which they meet again with the experts to receive feedback before finalizing the draft.

In a related approach, experts sit on the panel and discuss the evidence, but those with conflicts recuse themselves before the group votes on any recommendations. Delineating between discussions of the evidence and discussions of recommendations can be tricky, though, increasing the risk that a conflict of interest may influence the outcome. Even so, Dr. Guyatt says the model is still preferable to other alternatives.

Getting the Word Out

Once guidelines have been crafted and vetted, how can hospitalists get up to speed on them? Dr. Feldman’s favorite go-to source is Guideline.gov, a national guideline clearinghouse that he calls one of the best compendiums of available information. Especially helpful, he adds, are details such as how the guidelines were created.

To help maximize his time, he also uses tools like NEJM Journal Watch, which sends daily emails on noteworthy articles and weekend roundups of the most important studies.

“It is a way of at least trying to keep up with what’s going on,” he says. Similarly, he adds, ACP Journal Club provides summaries of important new articles, The Hospitalist can help highlight important guidelines that affect HM, and CME meetings or online modules like SHMconsults.com can help doctors keep pace.

For the past decade, Dr. Guyatt has worked with another popular tool, a guideline-disseminating service called UpToDate. Many alternatives exist, such as DynaMed Plus.

“I think you just need to pick away,” Dr. Feldman says. “You need to decide that as a physician, as a lifelong learner, that you are going to do something that is going to keep you up-to-date. There are many ways of doing it. You just have to decide what you’re going to do and commit to it.”

Researchers are helping out by studying how to present new guidelines in ways that engage doctors and improve patient outcomes. Another trend is to make guidelines routinely accessible not only in electronic medical records but also on tablets and smartphones. Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD, FHM, a hospitalist and clinical professor of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center, has studied how best-practice alerts, or BPAs, impact adherence to guidelines covering the appropriate use of blood products. Dr. Shieh, who splits her time between quality improvement and hospital medicine, says getting new information and guidelines into clinicians’ hands can be a logistical challenge.

“At Stanford, we had a huge official campaign around the guidelines, and that did make some impact, but it wasn’t huge in improving appropriate blood use,” she says. When the medial center set up a BPA through the electronic medical record system, however, both overall and inappropriate blood use declined significantly. In fact, the percentage of providers ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count above 8 g/dL dropped from 60% to 25%.6

One difference maker, Dr. Shieh says, was providing education at the moment a doctor actually ordered blood. To avoid alert fatigue, the “smart BPA” fires only if a doctor tries to order blood and the patient’s hemoglobin is greater than 7 or 8 g/dL, depending on the diagnosis. If the doctor still wants to transfuse, the system requests a clinical indication for the exception.

Despite the clear improvement in appropriate use, the team wanted to understand why 25% of providers were still ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count greater than 8 despite the triggered BPA and whether additional interventions could yield further improvements. Through their study, the researchers documented several reasons for the continued ordering. In some cases, the system failed to properly document actual or potential bleeding as an indicator. In other cases, the ordering reflected a lack of consensus on the guidelines in fields like hematology and oncology.

One of the most intriguing reasons, though, was that residents often did the ordering at the behest of an attending who might have never seen the BPA.

“It’s not actually reaching the audience making the decision; it might be reaching the audience that’s just carrying out the order,” Dr. Shieh says.

The insight, she says, may provide an opportunity to talk with attending physicians who may not have completely bought into the guidelines and to involve the entire team in the decision-making process.

Hospitalists, she says, can play a vital role in guideline development and implementation, especially for strategies that include BPAs.

“I think they’re the perfect group to help use this technology wisely because they are at the front lines taking care of patients so they’ll know the best workflow of when these alerts fire and maybe which ones happen the most often,” Dr. Shieh says. “I think this is a fantastic opportunity to get more hospitalists involved in designing these alerts and collaborating with the IT folks.”

Even with widespread buy-in from providers, guidelines may not reach their full potential without a careful consideration of patients’ values and concerns. Experts say joint deliberations and discussions are especially important for guidelines that are complicated, controversial, or carrying potential risks that must be weighed against the benefits.

Some of the conversations are easy, with well-defined risks and benefits and clear patient preferences, but others must traverse vast tracts of gray area. Fortunately, Dr. Feldman says, more tools also are becoming available for this kind of shared decision making. Some use pictorial representations to help patients understand the potential outcomes of alternative courses of action or inaction.

“Sometimes, that pictorial representation is worth the 1,000 words that we wouldn’t be able to adequately describe otherwise,” he says.

Similarly, Cincinnati Children’s has developed tools to help to ease the shared decision-making process.

“We look where there’s equivocal evidence or no evidence and have developed tools that help the clinician have that conversation with the family and then have them informed enough that they can actually weigh in on what they want,” Gerhardt says. One end product is a card or trifold pamphlet that might help parents understand the benefits and side effects of alternate strategies.

“Typically, in medicine, we’re used to telling people what needs to be done,” she says. “So shared decision making is kind of a different thing for clinicians to engage in.” TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

- Valle CW, Binns HJ, Quadri-Sheriff M, Benuck I, Patel A. Physicians’ lack of adherence to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines for pediatric lipid screening. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(12):1200-1205.

- Maynard G, Jenkins IH, Merli GJ. Venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients: mind the (implementation) gap. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):582-588.

- Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131(11):980-987.

- GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490

- Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726-735.

- 6. Chen JH, Fang DZ, Tim Goodnough L, Evans KH, Lee Porter M, Shieh L. Why providers transfuse blood products outside recommended guidelines in spite of integrated electronic best practice alerts. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):1-7.

One recent paper in Clinical Pediatrics, for example, chronicled low adherence to the 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute lipid screening guidelines in primary-care settings.1 Another cautioned providers to “mind the (implementation) gap” in venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients.2 A third found that lower adherence to guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for acute coronary syndrome patients was significantly associated with higher bleeding and mortality rates.3

Both clinical trials and real-world studies have demonstrated that when guidelines are applied, patients do better, says William Lewis, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and director of the Heart & Vascular Center at MetroHealth in Cleveland. So why aren’t they followed more consistently?

Experts in both HM and other disciplines cite multiple obstacles. Lack of evidence, conflicting evidence, or lack of awareness about evidence can all conspire against the main goal of helping providers deliver consistent high-value care, says Christopher Moriates, MD, assistant clinical professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“In our day-to-day lives as hospitalists, for the vast majority probably of what we do there’s no clear guideline or there’s a guideline that doesn’t necessarily apply to the patient standing in front of me,” he says.

Even when a guideline is clear and relevant, other doctors say inadequate dissemination and implementation can still derail quality improvement efforts.

“A lot of what we do as physicians is what we learned in residency, and to incorporate the new data is difficult,” says Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Feldman believes many doctors have yet to integrate recently revised hypertension and cholesterol guidelines into their practice, for example. Some guidelines have proven more complex or controversial, limiting their adoption.

“I know I struggle to keep up with all of the guidelines, and I’m in a big academic center where people are talking about them all the time, and I’m working with residents who are talking about them all the time,” Dr. Feldman says.

Despite the remaining gaps, however, many researchers agree that momentum has built steadily over the past two decades toward a more systematic approach to creating solid evidence-based guidelines and integrating them into real-world decision making.

Emphasis on Evidence and Transparency

The term “evidence-based medicine” was coined in 1990 by Gordon Guyatt, MD, MSc, FRCPC, distinguished professor of medicine and clinical epidemiology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. It’s played an active role in formulating guidelines for multiple organizations. The guideline-writing process, Dr. Guyatt says, once consisted of little more than self-selected clinicians sitting around a table.

“It used to be that a bunch of experts got together and decided and made the recommendations with very little in the way of a systematic process and certainly not evidence based,” he says.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center was among the pioneers pushing for a more systematic approach; the hospital began working on its own guidelines in 1995 and published the first of many the following year.

“We started evidence-based guidelines when the docs were still saying, ‘This is cookbook medicine. I don’t know if I want to do this or not,’” says Wendy Gerhardt, MSN, director of evidence-based decision making in the James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s.

Some doctors also argued that clinical guidelines would stifle innovation, cramp their individual style, or intrude on their relationships with patients. Despite some lingering misgivings among clinicians, however, the process has gained considerable support. In 2000, an organization called the GRADE Working Group (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) began developing a new approach to raise the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

The group’s work led to a 2004 article in BMJ, and the journal subsequently published a six-part series about GRADE for clinicians.4 More recently, the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology also delved into the issue with a 15-part series detailing the GRADE methodology.5 Together, Dr. Guyatt says, the articles have become a go-to guide for guidelines and have helped solidify the focus on evidence.

Cincinnati Children’s and other institutions also have developed tools, and the Institute of Medicine has published guideline-writing standards.

“So it’s easier than it’s ever been to know whether or not you have a decent guideline in your hand,” Gerhardt says.

Likewise, medical organizations are more clearly explaining how they came up with different kinds of guidelines. Evidence-based and consensus guidelines aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, though consensus building is often used in the absence of high-quality evidence. Some organizations have limited the pool of evidence for guidelines to randomized controlled trial data.

“Unfortunately, for us in the real world, we actually have to make decisions even when there’s not enough data,” Dr. Feldman says.

Sometimes, the best available evidence may be observational studies, and some committees still try to reach a consensus based on that evidence and on the panelists’ professional opinions.

Dr. Guyatt agrees that it’s “absolutely not” true that evidence-based guidelines require randomized controlled trials. “What you need for any recommendation is a thorough review and summary of the best available evidence,” he says.

As part of each final document, Cincinnati Children’s details how it created the guideline, when the literature searches occurred, how the committee reached a consensus, and which panelists participated in the deliberations. The information, Gerhardt says, allows anyone else to “make some sensible decisions about whether or not it’s a guideline you want to use.”

Guideline-crafting institutions are also focusing more on the proper makeup of their panels. In general, Dr. Guyatt says, a panel with more than 10 people can be unwieldy. Guidelines that include many specific recommendations, however, may require multiple subsections, each with its own committee.

Dr. Guyatt is careful to note that, like many other experts, he has multiple potential conflicts of interest, such as working on the anti-thrombotic guidelines issued by the American College of Chest Physicians. Committees, he says, have become increasingly aware of how properly handling conflicts (financial or otherwise) can be critical in building and maintaining trust among clinicians and patients. One technique is to ensure that a diversity of opinions is reflected among a committee whose experts have various conflicts. If one expert’s company makes drug A, for example, then the committee also includes experts involved with drugs B or C. As an alternative, some committees have explicitly barred anyone with a conflict of interest from participating at all.

But experts often provide crucial input, Dr. Guyatt says, and several committees have adopted variations of a middle-ground approach. In an approach that he favors, all guideline-formulating panelists are conflict-free but begin their work by meeting with a separate group of experts who may have some conflicts but can help point out the main issues. The panelists then deliberate and write a draft of the recommendations, after which they meet again with the experts to receive feedback before finalizing the draft.

In a related approach, experts sit on the panel and discuss the evidence, but those with conflicts recuse themselves before the group votes on any recommendations. Delineating between discussions of the evidence and discussions of recommendations can be tricky, though, increasing the risk that a conflict of interest may influence the outcome. Even so, Dr. Guyatt says the model is still preferable to other alternatives.

Getting the Word Out

Once guidelines have been crafted and vetted, how can hospitalists get up to speed on them? Dr. Feldman’s favorite go-to source is Guideline.gov, a national guideline clearinghouse that he calls one of the best compendiums of available information. Especially helpful, he adds, are details such as how the guidelines were created.

To help maximize his time, he also uses tools like NEJM Journal Watch, which sends daily emails on noteworthy articles and weekend roundups of the most important studies.

“It is a way of at least trying to keep up with what’s going on,” he says. Similarly, he adds, ACP Journal Club provides summaries of important new articles, The Hospitalist can help highlight important guidelines that affect HM, and CME meetings or online modules like SHMconsults.com can help doctors keep pace.

For the past decade, Dr. Guyatt has worked with another popular tool, a guideline-disseminating service called UpToDate. Many alternatives exist, such as DynaMed Plus.

“I think you just need to pick away,” Dr. Feldman says. “You need to decide that as a physician, as a lifelong learner, that you are going to do something that is going to keep you up-to-date. There are many ways of doing it. You just have to decide what you’re going to do and commit to it.”

Researchers are helping out by studying how to present new guidelines in ways that engage doctors and improve patient outcomes. Another trend is to make guidelines routinely accessible not only in electronic medical records but also on tablets and smartphones. Lisa Shieh, MD, PhD, FHM, a hospitalist and clinical professor of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center, has studied how best-practice alerts, or BPAs, impact adherence to guidelines covering the appropriate use of blood products. Dr. Shieh, who splits her time between quality improvement and hospital medicine, says getting new information and guidelines into clinicians’ hands can be a logistical challenge.

“At Stanford, we had a huge official campaign around the guidelines, and that did make some impact, but it wasn’t huge in improving appropriate blood use,” she says. When the medial center set up a BPA through the electronic medical record system, however, both overall and inappropriate blood use declined significantly. In fact, the percentage of providers ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count above 8 g/dL dropped from 60% to 25%.6

One difference maker, Dr. Shieh says, was providing education at the moment a doctor actually ordered blood. To avoid alert fatigue, the “smart BPA” fires only if a doctor tries to order blood and the patient’s hemoglobin is greater than 7 or 8 g/dL, depending on the diagnosis. If the doctor still wants to transfuse, the system requests a clinical indication for the exception.

Despite the clear improvement in appropriate use, the team wanted to understand why 25% of providers were still ordering blood products for patients with a hemoglobin count greater than 8 despite the triggered BPA and whether additional interventions could yield further improvements. Through their study, the researchers documented several reasons for the continued ordering. In some cases, the system failed to properly document actual or potential bleeding as an indicator. In other cases, the ordering reflected a lack of consensus on the guidelines in fields like hematology and oncology.

One of the most intriguing reasons, though, was that residents often did the ordering at the behest of an attending who might have never seen the BPA.

“It’s not actually reaching the audience making the decision; it might be reaching the audience that’s just carrying out the order,” Dr. Shieh says.

The insight, she says, may provide an opportunity to talk with attending physicians who may not have completely bought into the guidelines and to involve the entire team in the decision-making process.

Hospitalists, she says, can play a vital role in guideline development and implementation, especially for strategies that include BPAs.

“I think they’re the perfect group to help use this technology wisely because they are at the front lines taking care of patients so they’ll know the best workflow of when these alerts fire and maybe which ones happen the most often,” Dr. Shieh says. “I think this is a fantastic opportunity to get more hospitalists involved in designing these alerts and collaborating with the IT folks.”

Even with widespread buy-in from providers, guidelines may not reach their full potential without a careful consideration of patients’ values and concerns. Experts say joint deliberations and discussions are especially important for guidelines that are complicated, controversial, or carrying potential risks that must be weighed against the benefits.

Some of the conversations are easy, with well-defined risks and benefits and clear patient preferences, but others must traverse vast tracts of gray area. Fortunately, Dr. Feldman says, more tools also are becoming available for this kind of shared decision making. Some use pictorial representations to help patients understand the potential outcomes of alternative courses of action or inaction.

“Sometimes, that pictorial representation is worth the 1,000 words that we wouldn’t be able to adequately describe otherwise,” he says.

Similarly, Cincinnati Children’s has developed tools to help to ease the shared decision-making process.

“We look where there’s equivocal evidence or no evidence and have developed tools that help the clinician have that conversation with the family and then have them informed enough that they can actually weigh in on what they want,” Gerhardt says. One end product is a card or trifold pamphlet that might help parents understand the benefits and side effects of alternate strategies.

“Typically, in medicine, we’re used to telling people what needs to be done,” she says. “So shared decision making is kind of a different thing for clinicians to engage in.” TH

Bryn Nelson, PhD, is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

- Valle CW, Binns HJ, Quadri-Sheriff M, Benuck I, Patel A. Physicians’ lack of adherence to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines for pediatric lipid screening. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(12):1200-1205.

- Maynard G, Jenkins IH, Merli GJ. Venous thromboembolism prevention guidelines for medical inpatients: mind the (implementation) gap. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):582-588.

- Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131(11):980-987.