User login

Aquatic Antagonists: Jellyfish Stings

Jellyfish stings are one of the most common marine injuries, with an estimated 150 million stings occurring annually worldwide.1 Most jellyfish stings result in painful localized skin reactions that are self-limited and can be treated with conservative measures including hot water immersion and topical anesthetics. Life-threatening systemic reactions (eg, anaphylaxis, Irukandji syndrome) can occur with some species.2-4 Mainstream media reports do not reflect the true incidence and variability of jellyfish-related injuries that are commonly encountered in the clinic.3

Characteristics of Jellyfish

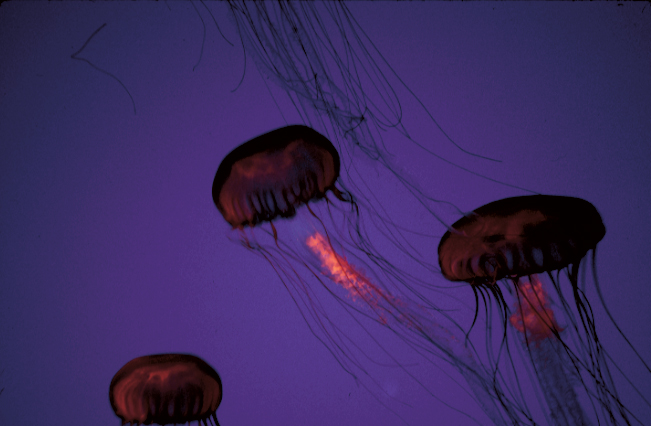

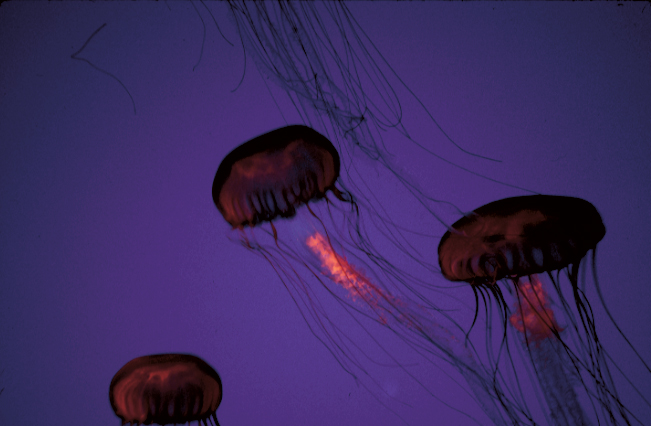

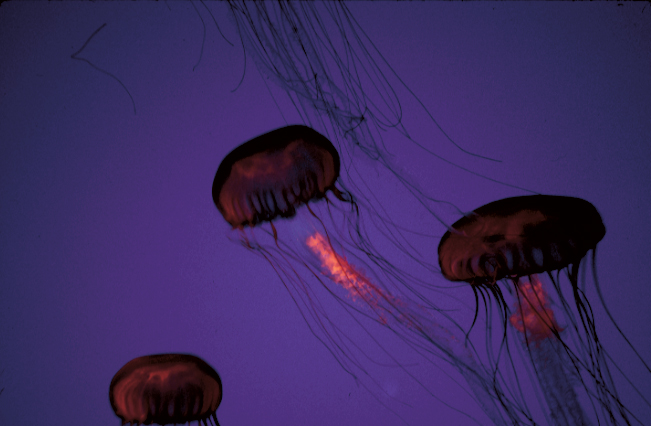

There are roughly 10,000 known species of jellyfish, with approximately 100 of them posing danger to humans.5 Jellyfish belong to the phylum Cnidaria, which is comprised of 5 classes of both free-floating and sessile animals: Staurozoa (stauromedusae), Hydrozoa (hydroids, fire corals, and Portuguese man-of-war), Scyphozoa (true jellyfish), Anthozoa (corals and sea anemones), and Cubozoa (box jellyfish and Irukandji jellyfish).1,2,6 Jellyfish typically have several tentacles suspended from a free-floating gelatinous body or bell; these tentacles are covered with thousands of cells unique to Cnidaria called nematocytes or cnidocytes containing specialized stinging organelles known as nematocysts. When triggered by physical (eg, human or foreign-body contact) or chemical stimuli, each nematocyst ejects a hollow filament or barb externally, releasing venom into the victim.7,8

The scyphozoan, hydrozoan, and cubozoan life cycles generally consist of a bottom-dwelling, sessile polyp form that produces multiple free-swimming ephyrae through an asexual reproductive process called strobilation. These ephyrae grow into the fully mature medusae, recognizable as jellyfish (Figure 1).5 Additionally, jellyfish populations experience cycles of temporal and spatial population abundance and crashes known as jellyfish blooms. In 2017, Kaffenberger et al9 reviewed the shifting landscape of skin diseases in North America attributable to major changes in climate and weather patterns, including the rise in jellyfish blooms and envenomation outbreaks worldwide (eg, Physalia physalis [Portuguese man-of-war][Figure 2] along the southeastern US coastline, Porpita pacifica off Japanese beaches). Some research suggests jellyfish surges relate to climate change and human interactions with jellyfish habitats by way of eutrophication and fishing (removing predators of jellyfish).9,10

Clinical Presentation

Jellyfish injuries can vary greatly in clinical symptoms, but they do follow some basic patterns. The severity of pain and symptoms is related to the jellyfish species, the number of stinging cells (nematocysts) that are triggered, and the potency of the venom that is absorbed by the victim.11-13 Most stings are minor, and patients experience immediate localized pain with serpiginous raised erythematous or urticarial lesions following the distribution of tentacle contact; these lesions have been described as tentaclelike and resembling a string of beads (Figure 3).12 Pain usually lasts a couple hours, while the skin lesions can last hours to days and can even recur years later. This pattern fits that of the well-known hydrozoans P physalis and Physalia utriculus (bluebottle), which are endemic to the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Oceans, respectively. The scyphozoan jellyfish causing similar presentations include Pelagia noctiluca (Mauve stinger), Aurelia aurita (Moon jellyfish), and Cyanea species. The cubozoan Chironex fleckeri (Australian box jellyfish or sea wasp) also causes tentaclelike stings but is widely considered the most dangerous jellyfish, as its venom is known to cause cardiac or respiratory arrest.4,11 More than 100 fatalities have been reported following severe envenomations from C fleckeri in Australian and Indo-Pacific waters.6

Stings from another box jellyfish species, Carukia barnesi, cause a unique presentation known as Irukandji syndrome. Carukia barnesi is a small box jellyfish with a bell measuring roughly 2 cm in diameter. It has nematocysts on both its bell and tentacles. It inhabits deeper waters and typically stings divers but also can wash ashore and injure beach tourists. Although Irukandji syndrome usually is associated with C barnesi, which is endemic to Northern Australian beaches, other jellyfish species including P physalis rarely have been linked to this potentially fatal syndrome.6,11 Unlike the immediate cutaneous and systemic findings described in C fleckeri encounters, symptoms of Irukandji-like stings can be delayed by up to 30 minutes. Patients may present with severe generalized pain (lower back, chest, headache), signs of excess catecholamine release (tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, diaphoresis, agitation), or cardiopulmonary decompensation (arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, pulmonary edema).6,11,14.15 Anaphylactic reactions also have been reported in those sensitized by prior stings.16

Management

Prevention of drowning is key in all marine injuries. Rescuers should remove the individual from the water, establish the ABCs—airway, breathing, and circulation—and seek acute medical attention. If immediate resuscitation is not required, douse the wound as soon as possible with a solution that halts further nematocyst discharge, which may contain alcohol, vinegar, or bicarbonate, depending on the prevalent species. General guidance is available to providers through evidence-based, point-of-care databases including UpToDate and DynaMed, as well as through the American Heart Association (AHA) or a country’s equivalent council on emergency care if residing outside the United States. Pressure immobilization bandages as a means of decreasing venom redistribution is no longer recommended by the AHA because animal studies have shown increased nematocyst discharge after pressure application.17 As such, touching or applying pressure to the affected area is not recommended until after a proper rinse solution has been applied. Tentacles may be removed mechanically with gloved hands or sand and seawater with minimal compression or agitation.

When acetic acid is appropriate, such as for cubozoan stings, commercially available vinegar (5% acetic acid in the United States) is preferred.16,17 Tap water can cause discharge of nematocysts, and seawater is preferred when no other solution is available.18 Most marine venoms are heat labile. Immersion in hot water can produce pain relief, but ice can be just as efficacious and is preferred by some patients. Prior reports of patients stung by Physalia species demonstrated greater pain relief with hot water immersion compared to ice pack application.18,19

In the setting of anaphylaxis, patients should receive epinephrine and be transported to a hospital with appropriate hemodynamic monitoring and supportive care. If the species of jellyfish has been identified, species-specific antivenin also may be available in certain regions (eg, C fleckeri antivenin manufactured in Australia), but it is unclear if it improves outcomes when compared with supportive care alone.6,16

Conclusion

Following jellyfish stings, most skin lesions will spontaneously resolve. Patients likely will present days to weeks following the inciting event with mild cutaneous symptoms that are amenable to topical corticosteroids. Recurrent dermatitis following a jellyfish sting is uncommon and is thought to be due to an immunologic mechanism consistent with type IV hypersensitivity reactions. Patients may require multiple courses of treatment before complete resolution.20

Patient education regarding marine envenomation and mechanical barriers such as wetsuits or stinger suits can reduce the risk for injury from jellyfish stings. Sting-inhibiting lotions also are commercially available, though more research is needed.21 Many beaches that are known to harbor the dangerous box jellyfish provide stinger nets to direct travelers to safer waters. Complete avoidance during jellyfish season is recommended in highly endemic areas.1

- Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, et al. Jellyfish stings and their management: a review. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:523-550.

- Hornbeak KB, Auerbach PS. Marine envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:321-337.

- Ward NT, Darracq MA, Tomaszewski C, et al. Evidence-based treatment of jellyfish stings in North America and Hawaii. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:399-414.

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Burnett HW. Jellyfish envenomation syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:100-106.

- Brotz L, Cheung WWL, Kleisner K, et al. Increasing jellyfish populations: trends in large marine ecosystems. Hydrobiologia. 2012;690:3-20.

- Ottuso PT. Aquatic antagonists: Cubozoan jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri and Carukia barnesi). Cutis. 2010;85:133-136.

- Lakkis NA, Maalouf GJ, Mahmassani DM. Jellyfish stings: a practical approach. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:422-429.

- Li L, McGee RG, Isbister G, et al. Interventions for the symptoms and signs resulting from jellyfish stings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD009688.

- Kaffenberger BH, Shetlar D, Norton SA, et al. The effect of climate change on skin disease in North America. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:140-147.

- Purcell JE, Uye S, Lo W. Anthropogenic causes of jellyfish blooms and their direct consequences for humans: a review. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;350:153-174.

- Berling I, Isbister G. Marine envenomations. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44:28-32.

- Tibballs J, Yanagihara AA, Turner HC, et al. Immunological and toxinological responses to jellyfish stings. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:438-446.

- Tibballs J. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon. 2006;48:830-859.

- Stein MR, Marracini JV, Rothschild NE, et al. Fatal Portuguese man-o’-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:312-315.

- Burnett JW, Gable WD. A fatal jellyfish envenomation by the Portuguese man-o’war. Toxicon. 1989;27:823-824.

- Warrell DA. Venomous bites, stings, and poisoning: an update. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:17-38.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 suppl 2):S315-S367.

- Wilcox CL, Headlam JL, Doyle TK, et al. Assessing the efficacy of first-aid measures in Physalia sp. envenomation, using solution- and blood agarose-based models. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9:149.

- Wilcox CL, Yanagihara AA. Heated debates: hot-water immersion or ice packs as first aid for cnidarian envenomations? Toxins (Basel). 2016;8:97.

- Loredana Asztalos M, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Recurrent dermatitis and dermal hypersensitivity following a jellyfish sting: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:217-219.

- Boulware DR. A randomized, controlled field trial for the prevention of jellyfish stings with a topical sting inhibitor. J Travel Med. 2006;13:166-171.

Jellyfish stings are one of the most common marine injuries, with an estimated 150 million stings occurring annually worldwide.1 Most jellyfish stings result in painful localized skin reactions that are self-limited and can be treated with conservative measures including hot water immersion and topical anesthetics. Life-threatening systemic reactions (eg, anaphylaxis, Irukandji syndrome) can occur with some species.2-4 Mainstream media reports do not reflect the true incidence and variability of jellyfish-related injuries that are commonly encountered in the clinic.3

Characteristics of Jellyfish

There are roughly 10,000 known species of jellyfish, with approximately 100 of them posing danger to humans.5 Jellyfish belong to the phylum Cnidaria, which is comprised of 5 classes of both free-floating and sessile animals: Staurozoa (stauromedusae), Hydrozoa (hydroids, fire corals, and Portuguese man-of-war), Scyphozoa (true jellyfish), Anthozoa (corals and sea anemones), and Cubozoa (box jellyfish and Irukandji jellyfish).1,2,6 Jellyfish typically have several tentacles suspended from a free-floating gelatinous body or bell; these tentacles are covered with thousands of cells unique to Cnidaria called nematocytes or cnidocytes containing specialized stinging organelles known as nematocysts. When triggered by physical (eg, human or foreign-body contact) or chemical stimuli, each nematocyst ejects a hollow filament or barb externally, releasing venom into the victim.7,8

The scyphozoan, hydrozoan, and cubozoan life cycles generally consist of a bottom-dwelling, sessile polyp form that produces multiple free-swimming ephyrae through an asexual reproductive process called strobilation. These ephyrae grow into the fully mature medusae, recognizable as jellyfish (Figure 1).5 Additionally, jellyfish populations experience cycles of temporal and spatial population abundance and crashes known as jellyfish blooms. In 2017, Kaffenberger et al9 reviewed the shifting landscape of skin diseases in North America attributable to major changes in climate and weather patterns, including the rise in jellyfish blooms and envenomation outbreaks worldwide (eg, Physalia physalis [Portuguese man-of-war][Figure 2] along the southeastern US coastline, Porpita pacifica off Japanese beaches). Some research suggests jellyfish surges relate to climate change and human interactions with jellyfish habitats by way of eutrophication and fishing (removing predators of jellyfish).9,10

Clinical Presentation

Jellyfish injuries can vary greatly in clinical symptoms, but they do follow some basic patterns. The severity of pain and symptoms is related to the jellyfish species, the number of stinging cells (nematocysts) that are triggered, and the potency of the venom that is absorbed by the victim.11-13 Most stings are minor, and patients experience immediate localized pain with serpiginous raised erythematous or urticarial lesions following the distribution of tentacle contact; these lesions have been described as tentaclelike and resembling a string of beads (Figure 3).12 Pain usually lasts a couple hours, while the skin lesions can last hours to days and can even recur years later. This pattern fits that of the well-known hydrozoans P physalis and Physalia utriculus (bluebottle), which are endemic to the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Oceans, respectively. The scyphozoan jellyfish causing similar presentations include Pelagia noctiluca (Mauve stinger), Aurelia aurita (Moon jellyfish), and Cyanea species. The cubozoan Chironex fleckeri (Australian box jellyfish or sea wasp) also causes tentaclelike stings but is widely considered the most dangerous jellyfish, as its venom is known to cause cardiac or respiratory arrest.4,11 More than 100 fatalities have been reported following severe envenomations from C fleckeri in Australian and Indo-Pacific waters.6

Stings from another box jellyfish species, Carukia barnesi, cause a unique presentation known as Irukandji syndrome. Carukia barnesi is a small box jellyfish with a bell measuring roughly 2 cm in diameter. It has nematocysts on both its bell and tentacles. It inhabits deeper waters and typically stings divers but also can wash ashore and injure beach tourists. Although Irukandji syndrome usually is associated with C barnesi, which is endemic to Northern Australian beaches, other jellyfish species including P physalis rarely have been linked to this potentially fatal syndrome.6,11 Unlike the immediate cutaneous and systemic findings described in C fleckeri encounters, symptoms of Irukandji-like stings can be delayed by up to 30 minutes. Patients may present with severe generalized pain (lower back, chest, headache), signs of excess catecholamine release (tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, diaphoresis, agitation), or cardiopulmonary decompensation (arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, pulmonary edema).6,11,14.15 Anaphylactic reactions also have been reported in those sensitized by prior stings.16

Management

Prevention of drowning is key in all marine injuries. Rescuers should remove the individual from the water, establish the ABCs—airway, breathing, and circulation—and seek acute medical attention. If immediate resuscitation is not required, douse the wound as soon as possible with a solution that halts further nematocyst discharge, which may contain alcohol, vinegar, or bicarbonate, depending on the prevalent species. General guidance is available to providers through evidence-based, point-of-care databases including UpToDate and DynaMed, as well as through the American Heart Association (AHA) or a country’s equivalent council on emergency care if residing outside the United States. Pressure immobilization bandages as a means of decreasing venom redistribution is no longer recommended by the AHA because animal studies have shown increased nematocyst discharge after pressure application.17 As such, touching or applying pressure to the affected area is not recommended until after a proper rinse solution has been applied. Tentacles may be removed mechanically with gloved hands or sand and seawater with minimal compression or agitation.

When acetic acid is appropriate, such as for cubozoan stings, commercially available vinegar (5% acetic acid in the United States) is preferred.16,17 Tap water can cause discharge of nematocysts, and seawater is preferred when no other solution is available.18 Most marine venoms are heat labile. Immersion in hot water can produce pain relief, but ice can be just as efficacious and is preferred by some patients. Prior reports of patients stung by Physalia species demonstrated greater pain relief with hot water immersion compared to ice pack application.18,19

In the setting of anaphylaxis, patients should receive epinephrine and be transported to a hospital with appropriate hemodynamic monitoring and supportive care. If the species of jellyfish has been identified, species-specific antivenin also may be available in certain regions (eg, C fleckeri antivenin manufactured in Australia), but it is unclear if it improves outcomes when compared with supportive care alone.6,16

Conclusion

Following jellyfish stings, most skin lesions will spontaneously resolve. Patients likely will present days to weeks following the inciting event with mild cutaneous symptoms that are amenable to topical corticosteroids. Recurrent dermatitis following a jellyfish sting is uncommon and is thought to be due to an immunologic mechanism consistent with type IV hypersensitivity reactions. Patients may require multiple courses of treatment before complete resolution.20

Patient education regarding marine envenomation and mechanical barriers such as wetsuits or stinger suits can reduce the risk for injury from jellyfish stings. Sting-inhibiting lotions also are commercially available, though more research is needed.21 Many beaches that are known to harbor the dangerous box jellyfish provide stinger nets to direct travelers to safer waters. Complete avoidance during jellyfish season is recommended in highly endemic areas.1

Jellyfish stings are one of the most common marine injuries, with an estimated 150 million stings occurring annually worldwide.1 Most jellyfish stings result in painful localized skin reactions that are self-limited and can be treated with conservative measures including hot water immersion and topical anesthetics. Life-threatening systemic reactions (eg, anaphylaxis, Irukandji syndrome) can occur with some species.2-4 Mainstream media reports do not reflect the true incidence and variability of jellyfish-related injuries that are commonly encountered in the clinic.3

Characteristics of Jellyfish

There are roughly 10,000 known species of jellyfish, with approximately 100 of them posing danger to humans.5 Jellyfish belong to the phylum Cnidaria, which is comprised of 5 classes of both free-floating and sessile animals: Staurozoa (stauromedusae), Hydrozoa (hydroids, fire corals, and Portuguese man-of-war), Scyphozoa (true jellyfish), Anthozoa (corals and sea anemones), and Cubozoa (box jellyfish and Irukandji jellyfish).1,2,6 Jellyfish typically have several tentacles suspended from a free-floating gelatinous body or bell; these tentacles are covered with thousands of cells unique to Cnidaria called nematocytes or cnidocytes containing specialized stinging organelles known as nematocysts. When triggered by physical (eg, human or foreign-body contact) or chemical stimuli, each nematocyst ejects a hollow filament or barb externally, releasing venom into the victim.7,8

The scyphozoan, hydrozoan, and cubozoan life cycles generally consist of a bottom-dwelling, sessile polyp form that produces multiple free-swimming ephyrae through an asexual reproductive process called strobilation. These ephyrae grow into the fully mature medusae, recognizable as jellyfish (Figure 1).5 Additionally, jellyfish populations experience cycles of temporal and spatial population abundance and crashes known as jellyfish blooms. In 2017, Kaffenberger et al9 reviewed the shifting landscape of skin diseases in North America attributable to major changes in climate and weather patterns, including the rise in jellyfish blooms and envenomation outbreaks worldwide (eg, Physalia physalis [Portuguese man-of-war][Figure 2] along the southeastern US coastline, Porpita pacifica off Japanese beaches). Some research suggests jellyfish surges relate to climate change and human interactions with jellyfish habitats by way of eutrophication and fishing (removing predators of jellyfish).9,10

Clinical Presentation

Jellyfish injuries can vary greatly in clinical symptoms, but they do follow some basic patterns. The severity of pain and symptoms is related to the jellyfish species, the number of stinging cells (nematocysts) that are triggered, and the potency of the venom that is absorbed by the victim.11-13 Most stings are minor, and patients experience immediate localized pain with serpiginous raised erythematous or urticarial lesions following the distribution of tentacle contact; these lesions have been described as tentaclelike and resembling a string of beads (Figure 3).12 Pain usually lasts a couple hours, while the skin lesions can last hours to days and can even recur years later. This pattern fits that of the well-known hydrozoans P physalis and Physalia utriculus (bluebottle), which are endemic to the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Oceans, respectively. The scyphozoan jellyfish causing similar presentations include Pelagia noctiluca (Mauve stinger), Aurelia aurita (Moon jellyfish), and Cyanea species. The cubozoan Chironex fleckeri (Australian box jellyfish or sea wasp) also causes tentaclelike stings but is widely considered the most dangerous jellyfish, as its venom is known to cause cardiac or respiratory arrest.4,11 More than 100 fatalities have been reported following severe envenomations from C fleckeri in Australian and Indo-Pacific waters.6

Stings from another box jellyfish species, Carukia barnesi, cause a unique presentation known as Irukandji syndrome. Carukia barnesi is a small box jellyfish with a bell measuring roughly 2 cm in diameter. It has nematocysts on both its bell and tentacles. It inhabits deeper waters and typically stings divers but also can wash ashore and injure beach tourists. Although Irukandji syndrome usually is associated with C barnesi, which is endemic to Northern Australian beaches, other jellyfish species including P physalis rarely have been linked to this potentially fatal syndrome.6,11 Unlike the immediate cutaneous and systemic findings described in C fleckeri encounters, symptoms of Irukandji-like stings can be delayed by up to 30 minutes. Patients may present with severe generalized pain (lower back, chest, headache), signs of excess catecholamine release (tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, diaphoresis, agitation), or cardiopulmonary decompensation (arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, pulmonary edema).6,11,14.15 Anaphylactic reactions also have been reported in those sensitized by prior stings.16

Management

Prevention of drowning is key in all marine injuries. Rescuers should remove the individual from the water, establish the ABCs—airway, breathing, and circulation—and seek acute medical attention. If immediate resuscitation is not required, douse the wound as soon as possible with a solution that halts further nematocyst discharge, which may contain alcohol, vinegar, or bicarbonate, depending on the prevalent species. General guidance is available to providers through evidence-based, point-of-care databases including UpToDate and DynaMed, as well as through the American Heart Association (AHA) or a country’s equivalent council on emergency care if residing outside the United States. Pressure immobilization bandages as a means of decreasing venom redistribution is no longer recommended by the AHA because animal studies have shown increased nematocyst discharge after pressure application.17 As such, touching or applying pressure to the affected area is not recommended until after a proper rinse solution has been applied. Tentacles may be removed mechanically with gloved hands or sand and seawater with minimal compression or agitation.

When acetic acid is appropriate, such as for cubozoan stings, commercially available vinegar (5% acetic acid in the United States) is preferred.16,17 Tap water can cause discharge of nematocysts, and seawater is preferred when no other solution is available.18 Most marine venoms are heat labile. Immersion in hot water can produce pain relief, but ice can be just as efficacious and is preferred by some patients. Prior reports of patients stung by Physalia species demonstrated greater pain relief with hot water immersion compared to ice pack application.18,19

In the setting of anaphylaxis, patients should receive epinephrine and be transported to a hospital with appropriate hemodynamic monitoring and supportive care. If the species of jellyfish has been identified, species-specific antivenin also may be available in certain regions (eg, C fleckeri antivenin manufactured in Australia), but it is unclear if it improves outcomes when compared with supportive care alone.6,16

Conclusion

Following jellyfish stings, most skin lesions will spontaneously resolve. Patients likely will present days to weeks following the inciting event with mild cutaneous symptoms that are amenable to topical corticosteroids. Recurrent dermatitis following a jellyfish sting is uncommon and is thought to be due to an immunologic mechanism consistent with type IV hypersensitivity reactions. Patients may require multiple courses of treatment before complete resolution.20

Patient education regarding marine envenomation and mechanical barriers such as wetsuits or stinger suits can reduce the risk for injury from jellyfish stings. Sting-inhibiting lotions also are commercially available, though more research is needed.21 Many beaches that are known to harbor the dangerous box jellyfish provide stinger nets to direct travelers to safer waters. Complete avoidance during jellyfish season is recommended in highly endemic areas.1

- Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, et al. Jellyfish stings and their management: a review. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:523-550.

- Hornbeak KB, Auerbach PS. Marine envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:321-337.

- Ward NT, Darracq MA, Tomaszewski C, et al. Evidence-based treatment of jellyfish stings in North America and Hawaii. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:399-414.

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Burnett HW. Jellyfish envenomation syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:100-106.

- Brotz L, Cheung WWL, Kleisner K, et al. Increasing jellyfish populations: trends in large marine ecosystems. Hydrobiologia. 2012;690:3-20.

- Ottuso PT. Aquatic antagonists: Cubozoan jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri and Carukia barnesi). Cutis. 2010;85:133-136.

- Lakkis NA, Maalouf GJ, Mahmassani DM. Jellyfish stings: a practical approach. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:422-429.

- Li L, McGee RG, Isbister G, et al. Interventions for the symptoms and signs resulting from jellyfish stings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD009688.

- Kaffenberger BH, Shetlar D, Norton SA, et al. The effect of climate change on skin disease in North America. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:140-147.

- Purcell JE, Uye S, Lo W. Anthropogenic causes of jellyfish blooms and their direct consequences for humans: a review. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;350:153-174.

- Berling I, Isbister G. Marine envenomations. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44:28-32.

- Tibballs J, Yanagihara AA, Turner HC, et al. Immunological and toxinological responses to jellyfish stings. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:438-446.

- Tibballs J. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon. 2006;48:830-859.

- Stein MR, Marracini JV, Rothschild NE, et al. Fatal Portuguese man-o’-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:312-315.

- Burnett JW, Gable WD. A fatal jellyfish envenomation by the Portuguese man-o’war. Toxicon. 1989;27:823-824.

- Warrell DA. Venomous bites, stings, and poisoning: an update. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:17-38.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 suppl 2):S315-S367.

- Wilcox CL, Headlam JL, Doyle TK, et al. Assessing the efficacy of first-aid measures in Physalia sp. envenomation, using solution- and blood agarose-based models. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9:149.

- Wilcox CL, Yanagihara AA. Heated debates: hot-water immersion or ice packs as first aid for cnidarian envenomations? Toxins (Basel). 2016;8:97.

- Loredana Asztalos M, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Recurrent dermatitis and dermal hypersensitivity following a jellyfish sting: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:217-219.

- Boulware DR. A randomized, controlled field trial for the prevention of jellyfish stings with a topical sting inhibitor. J Travel Med. 2006;13:166-171.

- Cegolon L, Heymann WC, Lange JH, et al. Jellyfish stings and their management: a review. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:523-550.

- Hornbeak KB, Auerbach PS. Marine envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:321-337.

- Ward NT, Darracq MA, Tomaszewski C, et al. Evidence-based treatment of jellyfish stings in North America and Hawaii. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:399-414.

- Burnett JW, Calton GJ, Burnett HW. Jellyfish envenomation syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:100-106.

- Brotz L, Cheung WWL, Kleisner K, et al. Increasing jellyfish populations: trends in large marine ecosystems. Hydrobiologia. 2012;690:3-20.

- Ottuso PT. Aquatic antagonists: Cubozoan jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri and Carukia barnesi). Cutis. 2010;85:133-136.

- Lakkis NA, Maalouf GJ, Mahmassani DM. Jellyfish stings: a practical approach. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:422-429.

- Li L, McGee RG, Isbister G, et al. Interventions for the symptoms and signs resulting from jellyfish stings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD009688.

- Kaffenberger BH, Shetlar D, Norton SA, et al. The effect of climate change on skin disease in North America. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:140-147.

- Purcell JE, Uye S, Lo W. Anthropogenic causes of jellyfish blooms and their direct consequences for humans: a review. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;350:153-174.

- Berling I, Isbister G. Marine envenomations. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44:28-32.

- Tibballs J, Yanagihara AA, Turner HC, et al. Immunological and toxinological responses to jellyfish stings. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:438-446.

- Tibballs J. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon. 2006;48:830-859.

- Stein MR, Marracini JV, Rothschild NE, et al. Fatal Portuguese man-o’-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:312-315.

- Burnett JW, Gable WD. A fatal jellyfish envenomation by the Portuguese man-o’war. Toxicon. 1989;27:823-824.

- Warrell DA. Venomous bites, stings, and poisoning: an update. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:17-38.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 suppl 2):S315-S367.

- Wilcox CL, Headlam JL, Doyle TK, et al. Assessing the efficacy of first-aid measures in Physalia sp. envenomation, using solution- and blood agarose-based models. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9:149.

- Wilcox CL, Yanagihara AA. Heated debates: hot-water immersion or ice packs as first aid for cnidarian envenomations? Toxins (Basel). 2016;8:97.

- Loredana Asztalos M, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Recurrent dermatitis and dermal hypersensitivity following a jellyfish sting: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:217-219.

- Boulware DR. A randomized, controlled field trial for the prevention of jellyfish stings with a topical sting inhibitor. J Travel Med. 2006;13:166-171.

Practice Points

- Jellyfish stings occur an estimated 150 million times annually worldwide, with numbers expected to rise due to climate change.

- Most stings result in painful self-limited cutaneous symptoms that resolve spontaneously. Box jellyfish (Cubozoa) stings carry a greater risk for causing severe systemic reactions.

- Treatment of skin reactions includes removal of tentacles and hot water immersion. Vinegar dousing for at least 30 seconds is recommended for box jellyfish stings. Supportive care and monitoring for cardiovascular collapse are key. The role of antivenin is uncertain.

What’s Eating You? Caterpillars

Causes of Lepidopterism

Caterpillars are wormlike organisms that serve as the larval stage of moths and butterflies, which belong to the order Lepidoptera. There are almost 165,000 discovered species, with 13,000 found in the United States.1,2 Roughly 150 species are known to have the potential to cause an adverse reaction in humans, with 50 of these in the United States.1Lepidopterism describes systemic and cutaneous reactions to moths, butterflies, and caterpillars; erucism describes strictly cutaneous reactions.1

Although the rate of lepidopterism is thought to be underreported because it often is self-limited and of a mild nature, a review found caterpillars to be the cause of roughly 2.2% of reported bites and stings annually.2 Cases increase in number with seasonal increases in caterpillars, which vary by region and species. For example, the Megalopyge opercularis (southern flannel moth) caterpillar was noted to have 2 peaks in a Texas-based study: 12% of reported stings occurred in July; 59% from October through November.3 In general, the likelihood of exposure increases during warmer months, and exposure is more common in people who work outdoors in a rural area or in a suburban area where there are many caterpillar-infested trees.4

Most cases of lepidopterism are caused by caterpillars, not by adult butterflies and moths, because the former have many tubular, or porous, hairlike structures called setae that are embedded in the integument. Setae were once thought to be connected to poison-secreting glandular cells, but current belief is that venomous caterpillars lack specialized gland cells and instead produce venom through secretory epithelial cells located above the integument.1 Venom accumulates in the hemolymph and is stored in the setae or other types of bristles, such as scoli (wartlike bumps that bear setae) or spines.5 With a large amount of chitin, bristles have a tendency to fracture and release venom upon contact.1 It is thought that some species of caterpillars formulate venom by ingesting toxins or toxin precursors from plants; for example, the tiger moth (family Arctiidae) is known to produce venom containing biogenic amines, pyrrolizidine, alkaloids, and cardiac glycosides obtained through food sources.5

Even if a caterpillar does not produce venom, its setae might embed into skin or mucous membranes and cause an adverse irritant reaction.1 Setae also might dislodge and be transported in the air to embed in objects—some remaining stable in the environment for longer than a year.2 In contrast to setae, spines are permanently fixed into the integument; for that reason, only direct contact with the caterpillar can result in an adverse reaction. Although it is mostly caterpillars that contain setae and spines, certain species of moths also might contain these structures or might acquire them as they emerge from the cocoon, which often contains incorporated setae.2

Reactions in Humans

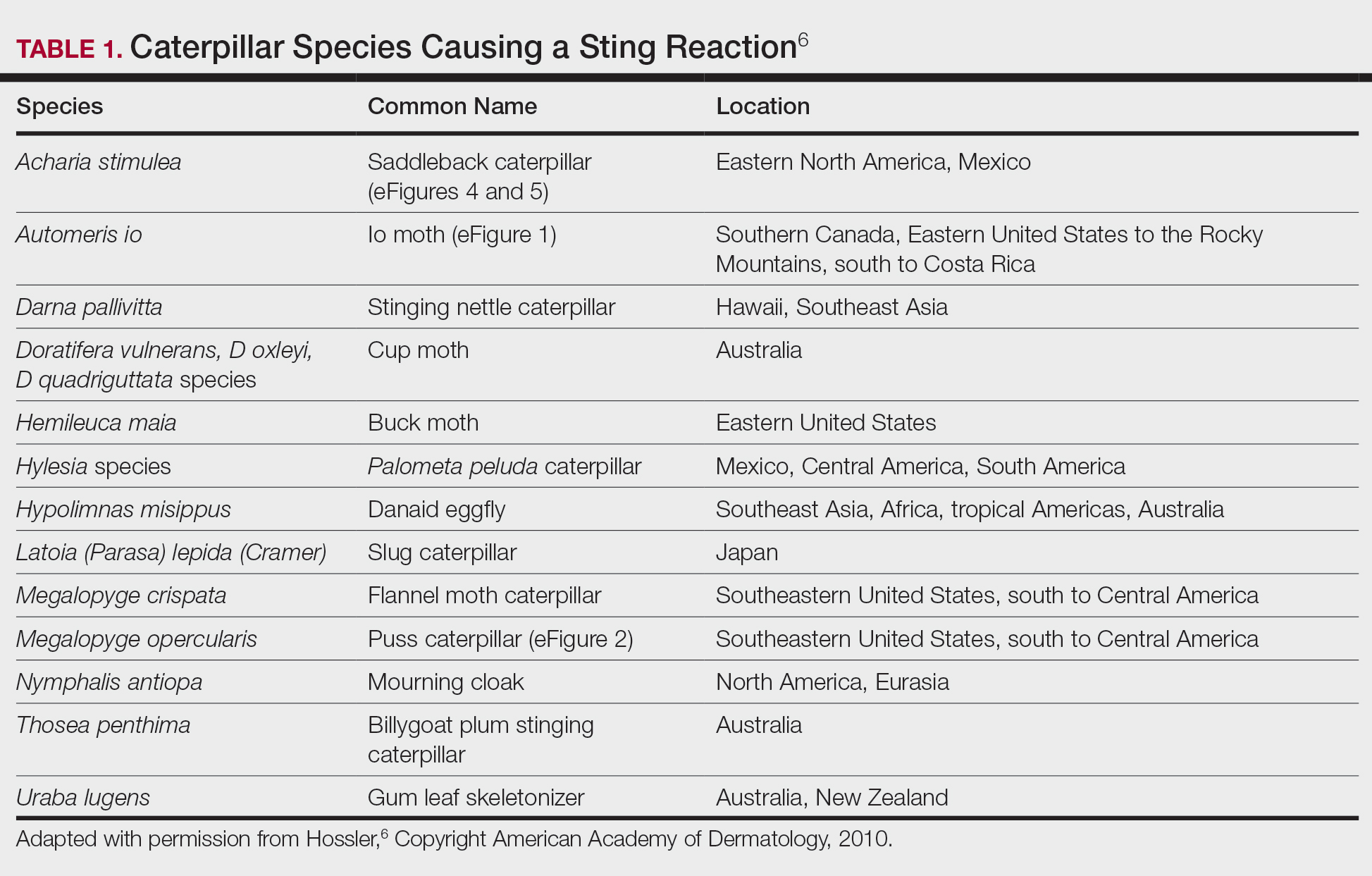

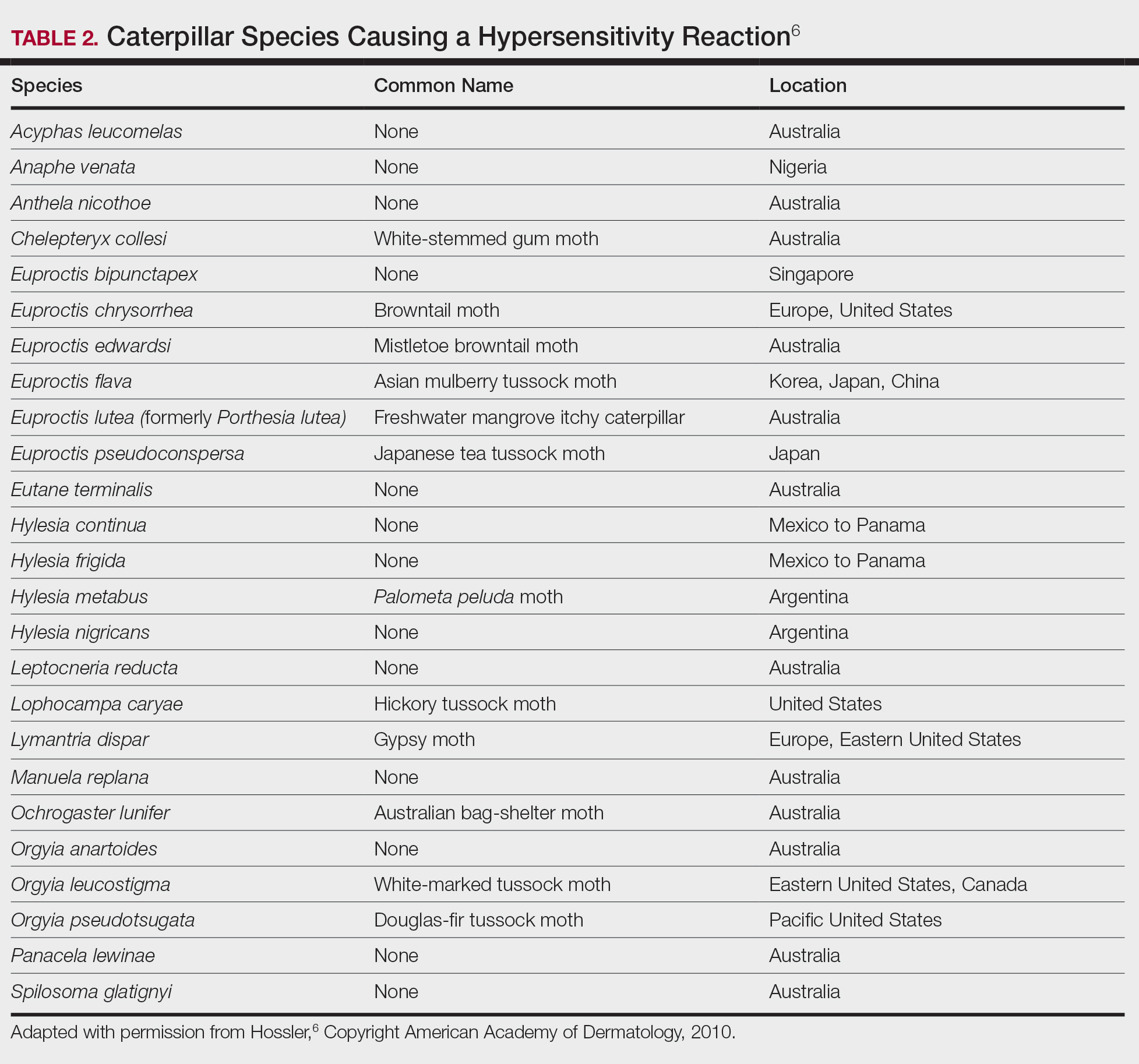

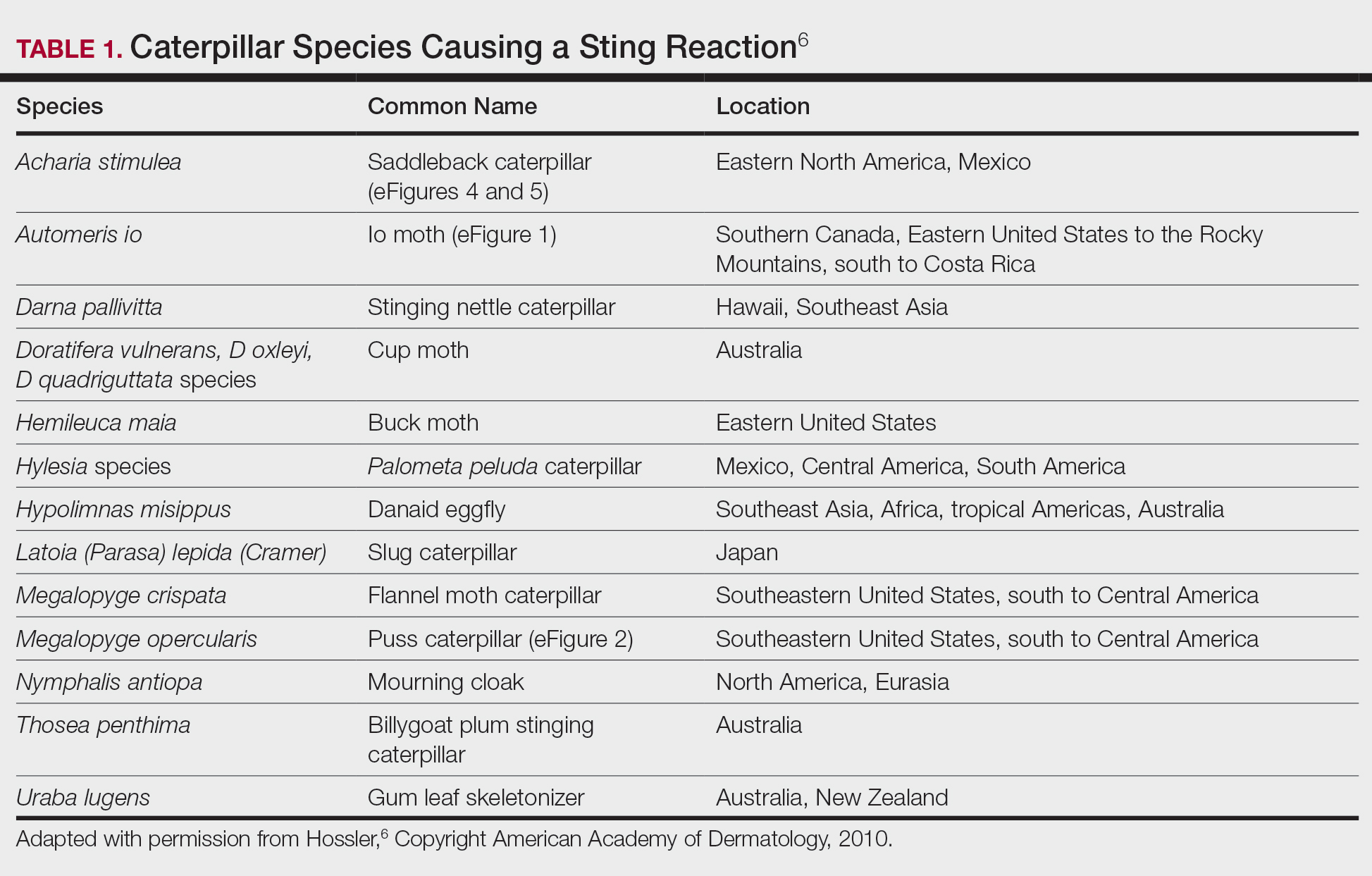

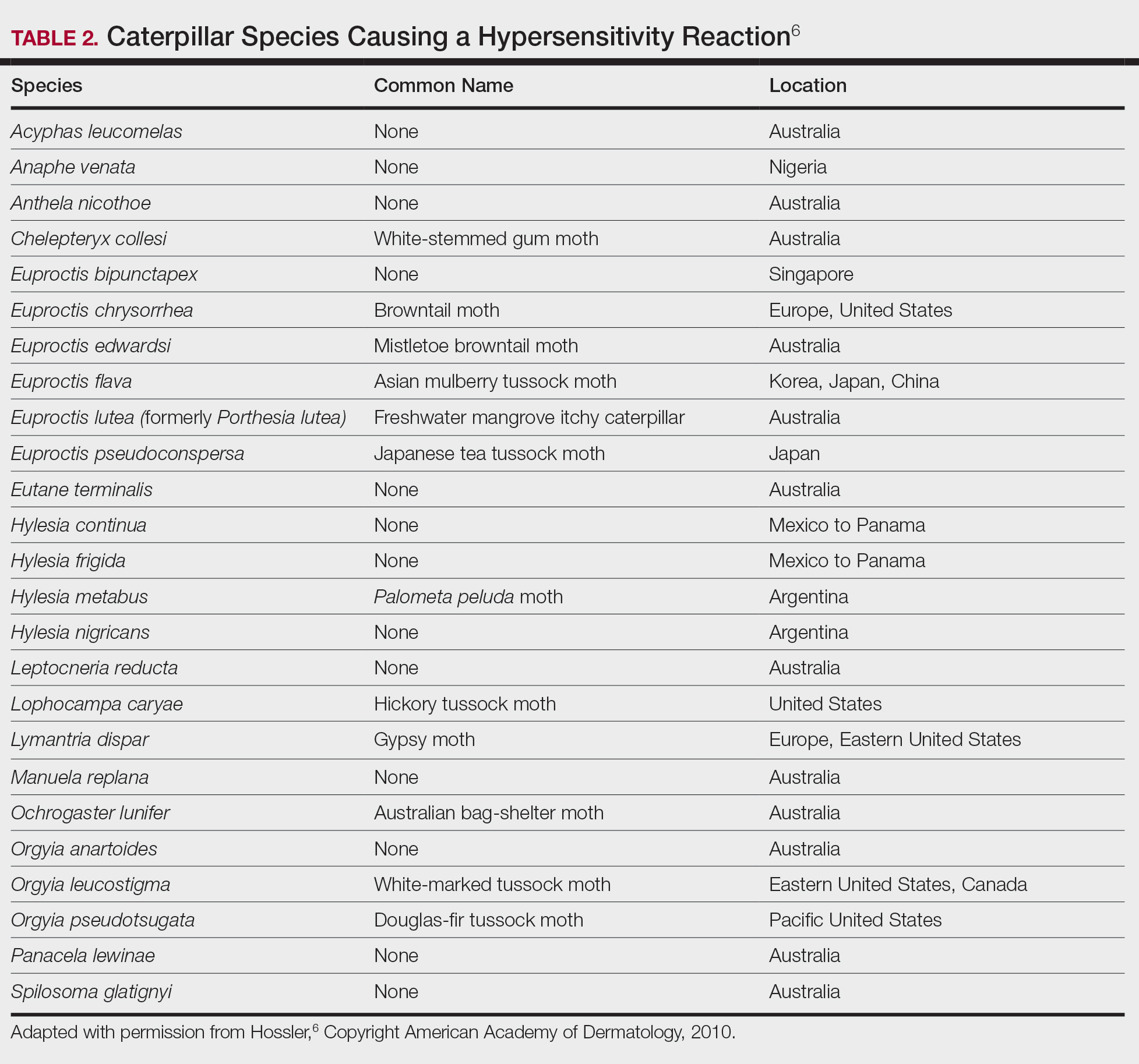

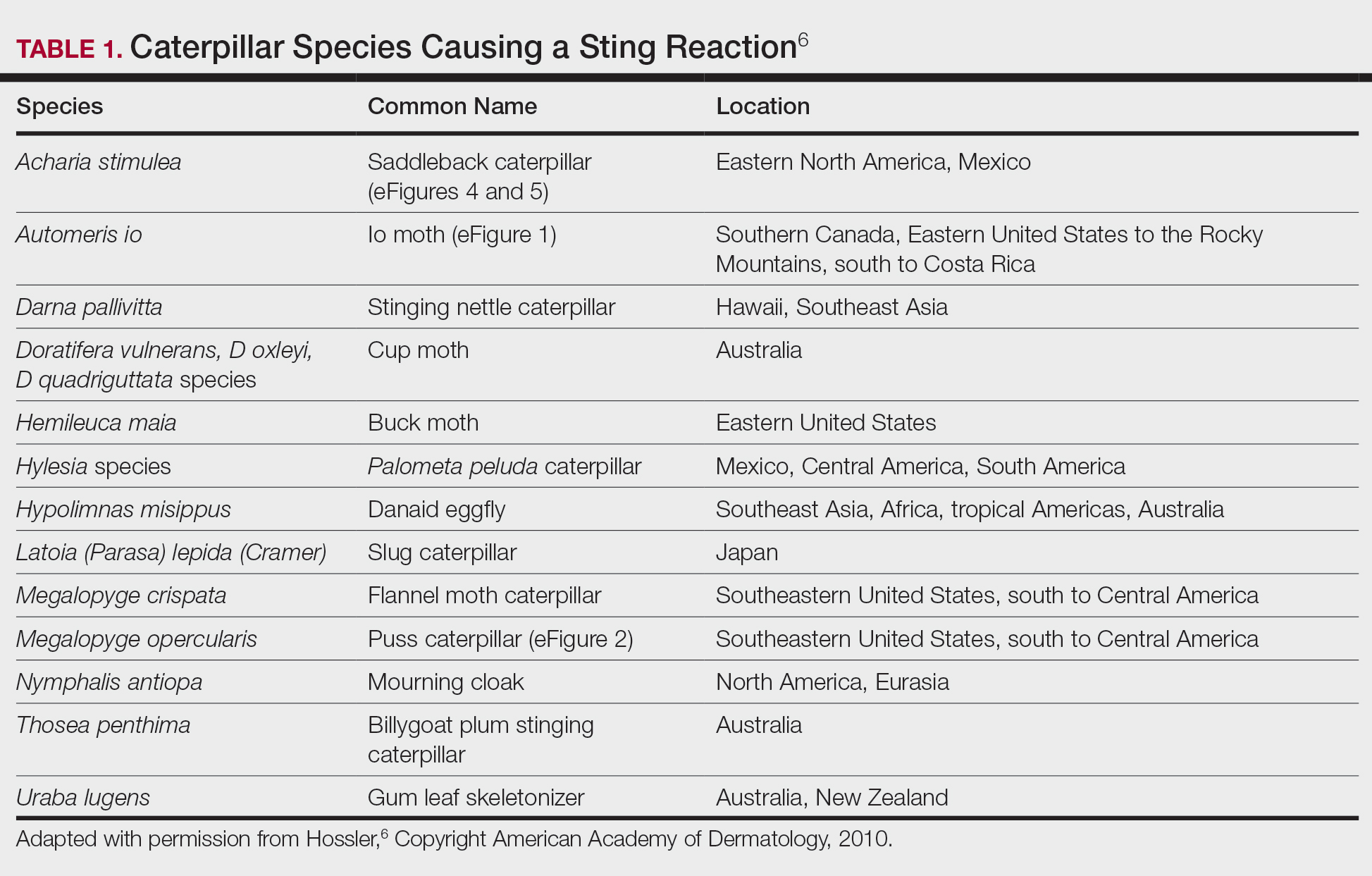

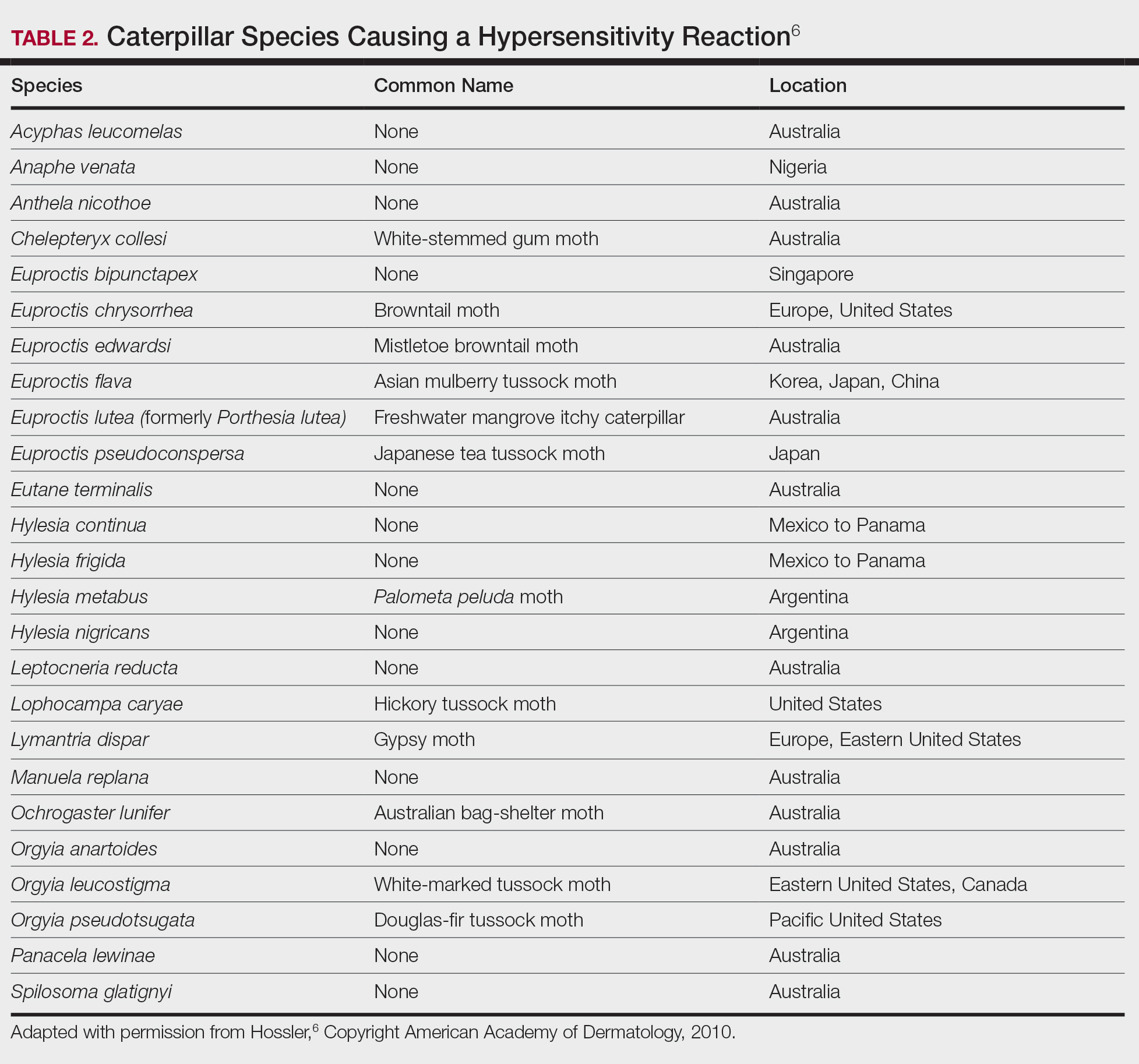

Lepidopterism encompasses 3 principal reactions in humans: sting reaction, hypersensitivity reaction, and lonomism (a hemorrhagic diathesis produced by Lonomia caterpillars). The type and severity of the reaction depends on (1) the species of caterpillar or moth and (2) the individual patient.2 There are approximately 12 families of caterpillars, mainly of the moth variety, that can cause an adverse reaction in humans.1 Tables 1 and 2 list examples of species that cause each type of reaction.6

Chemicals and toxins contained in the poison of setae and spines vary by species of caterpillar. Numerous kinds have been isolated from different venoms,1,2 including several peptides, histamine, histamine-releasing substances, acetylcholine, phospholipase A, hyaluronidase, formic acid, proteins with trypsinlike activity, serine proteases such as kallikrein, and other enzymes with vasodegenerative and fibrinolytic properties

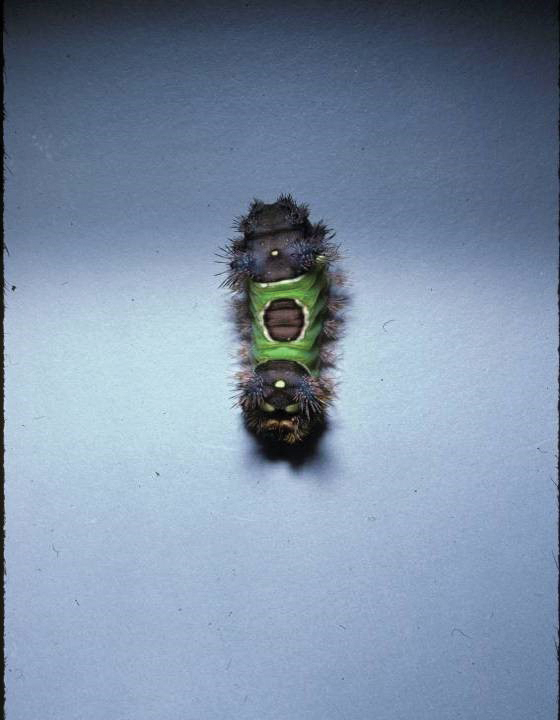

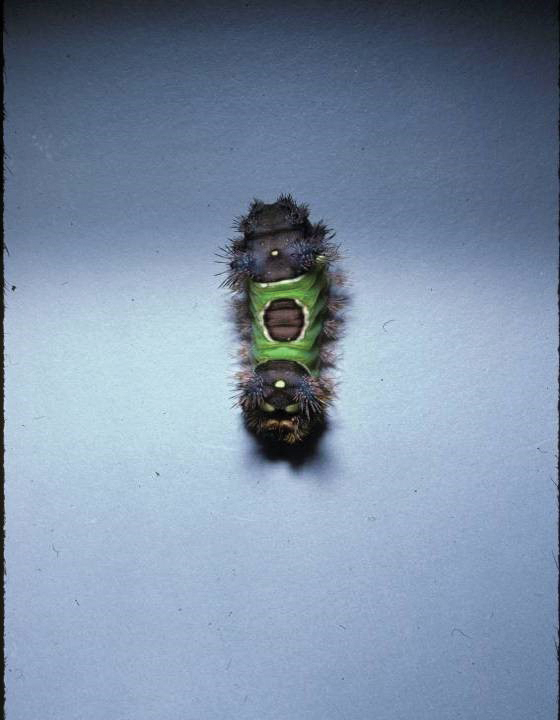

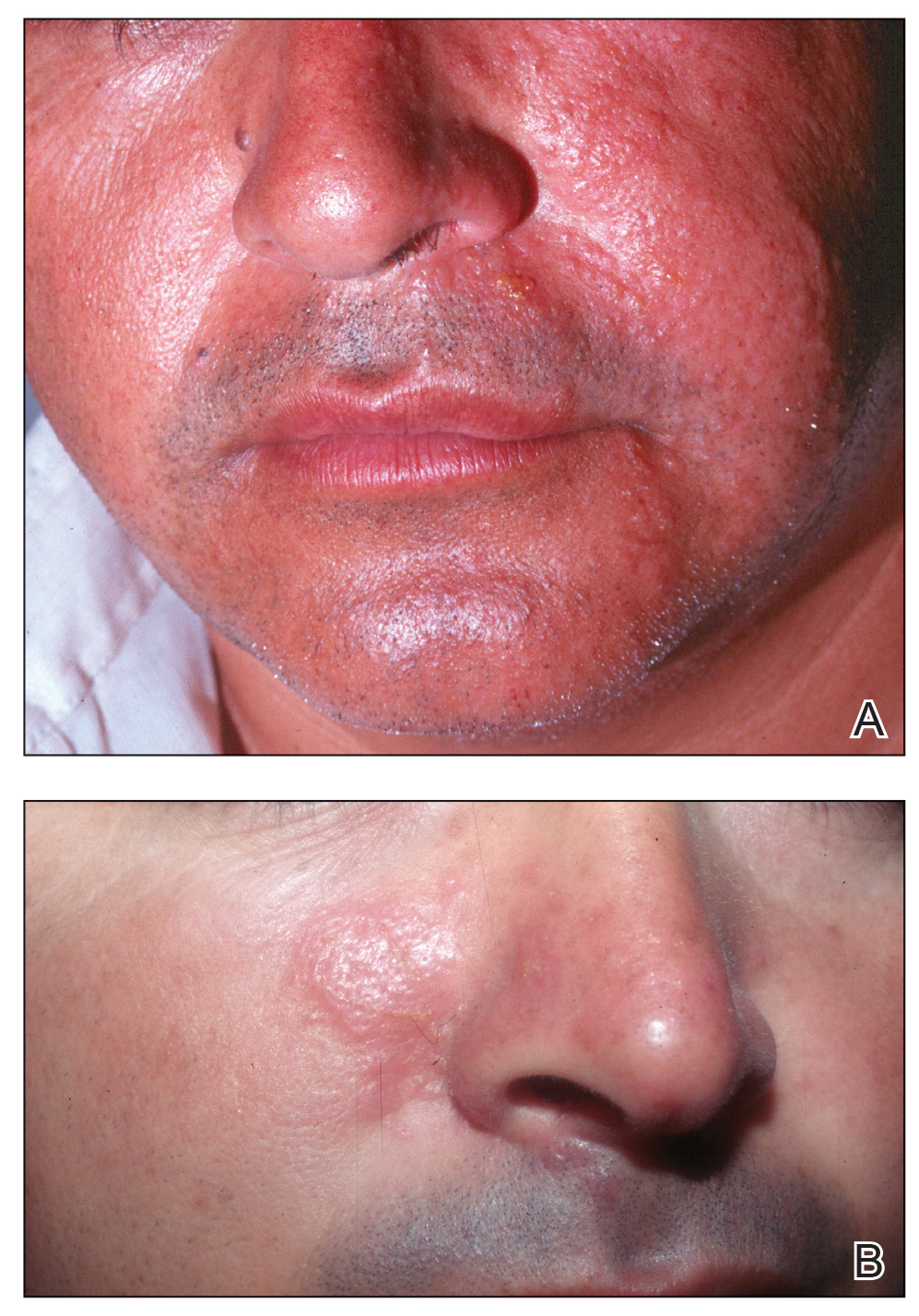

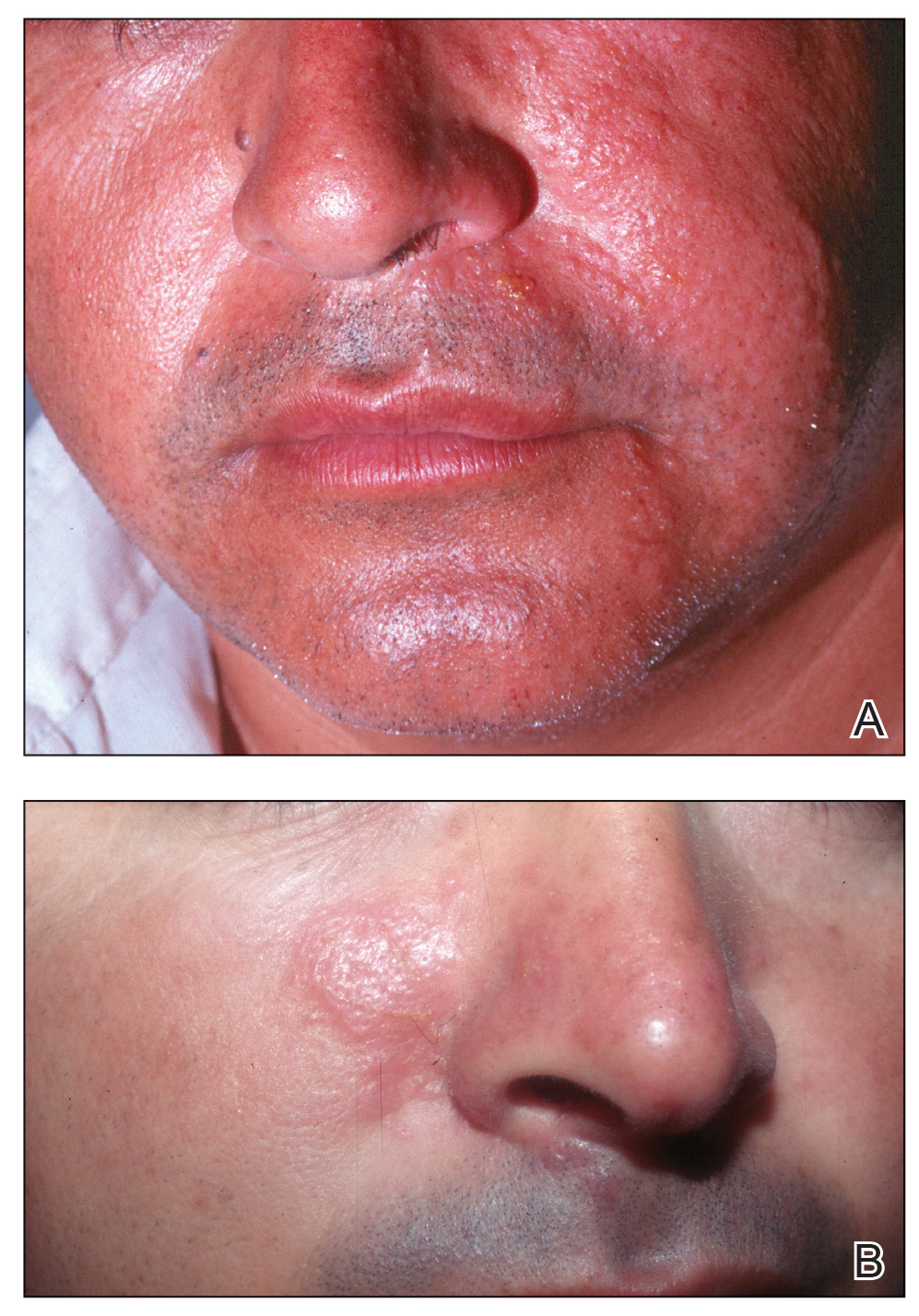

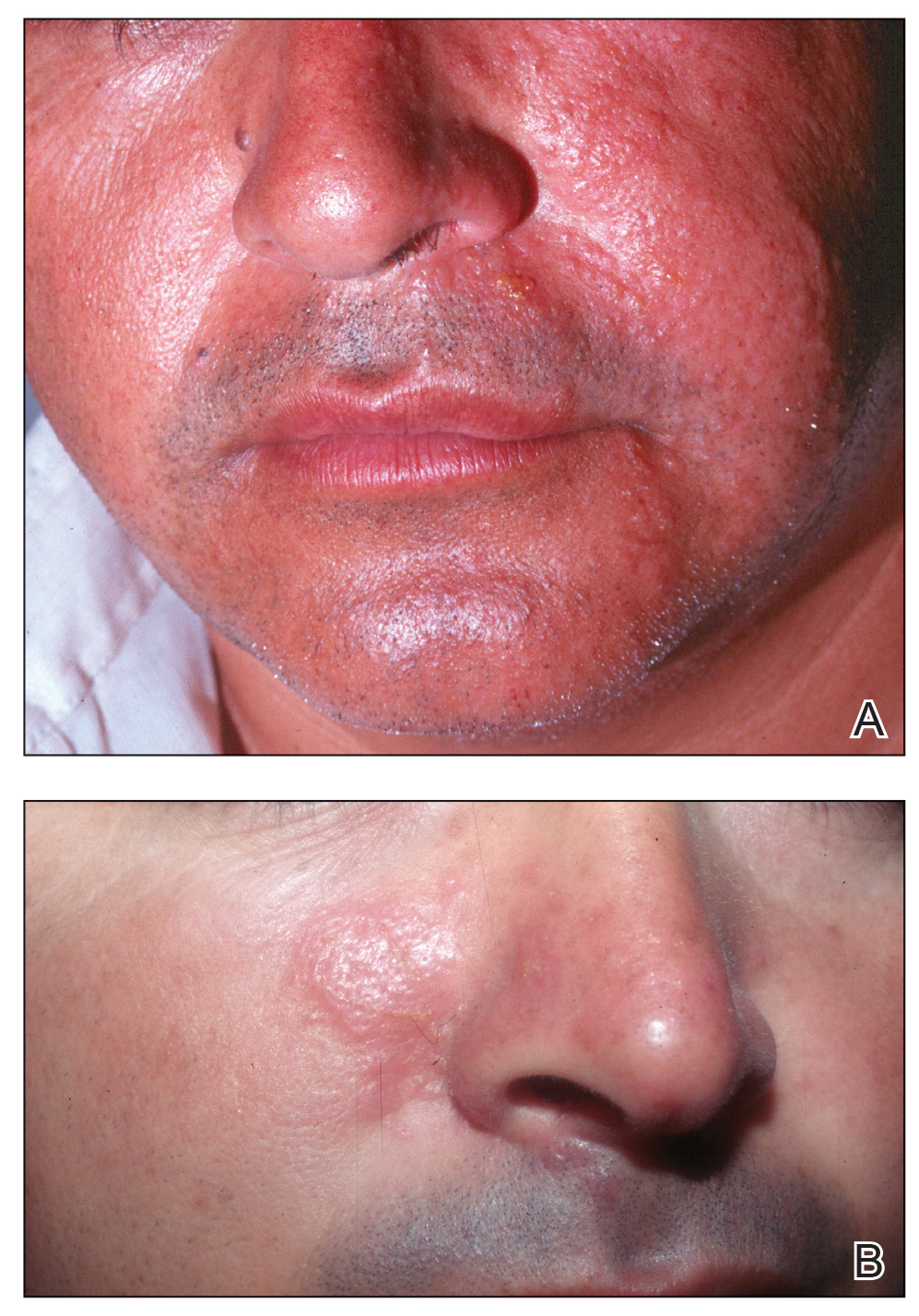

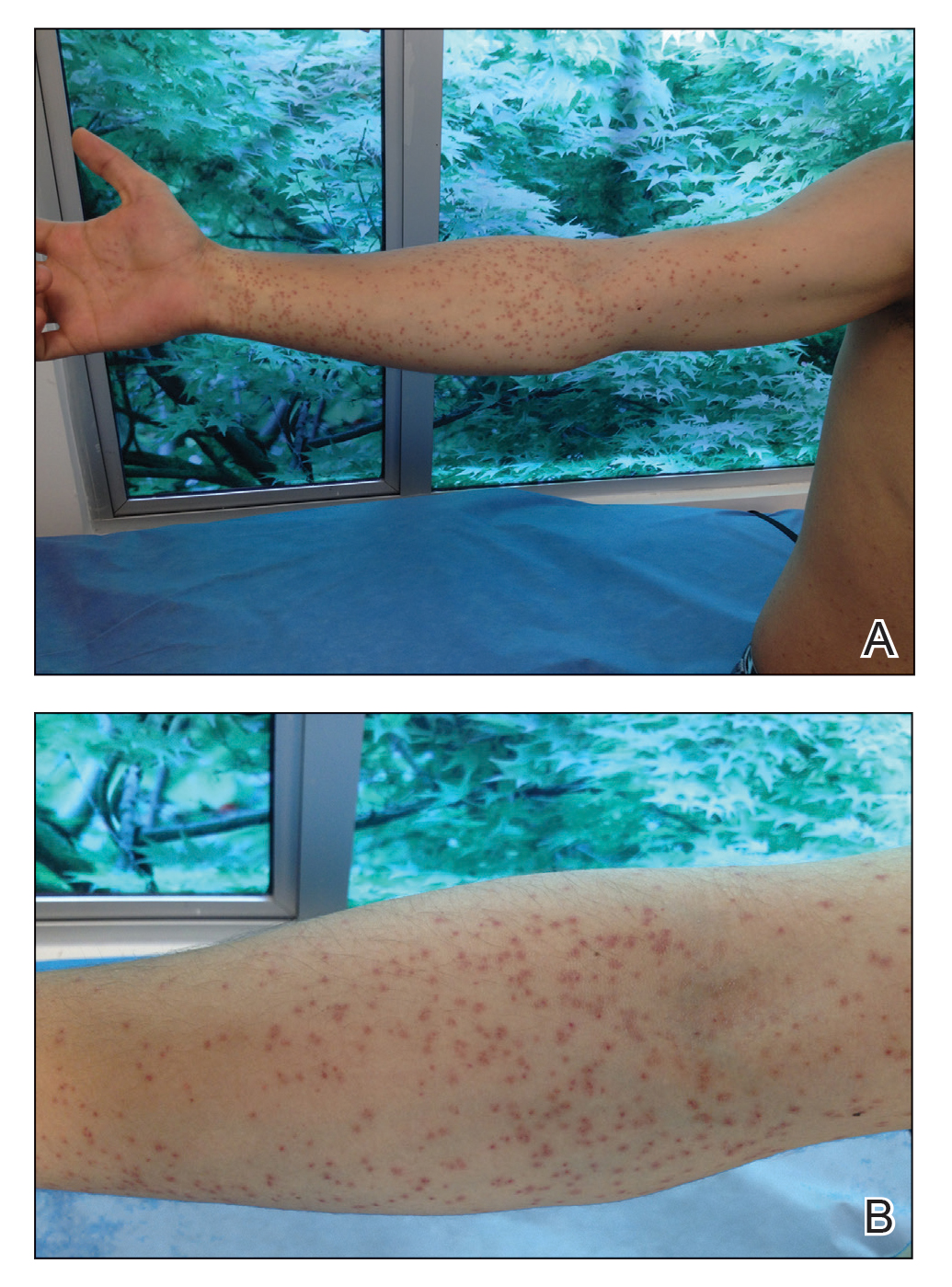

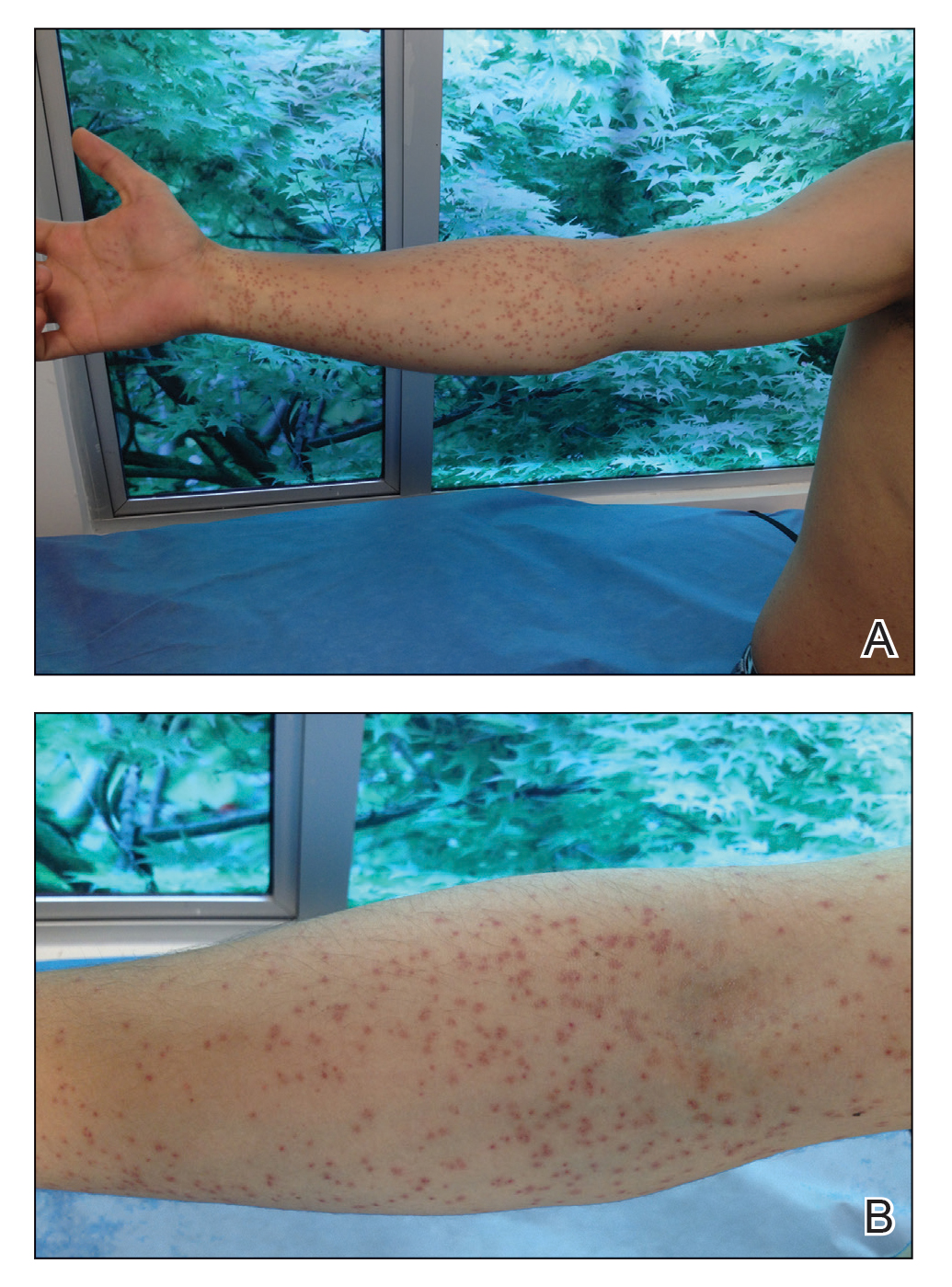

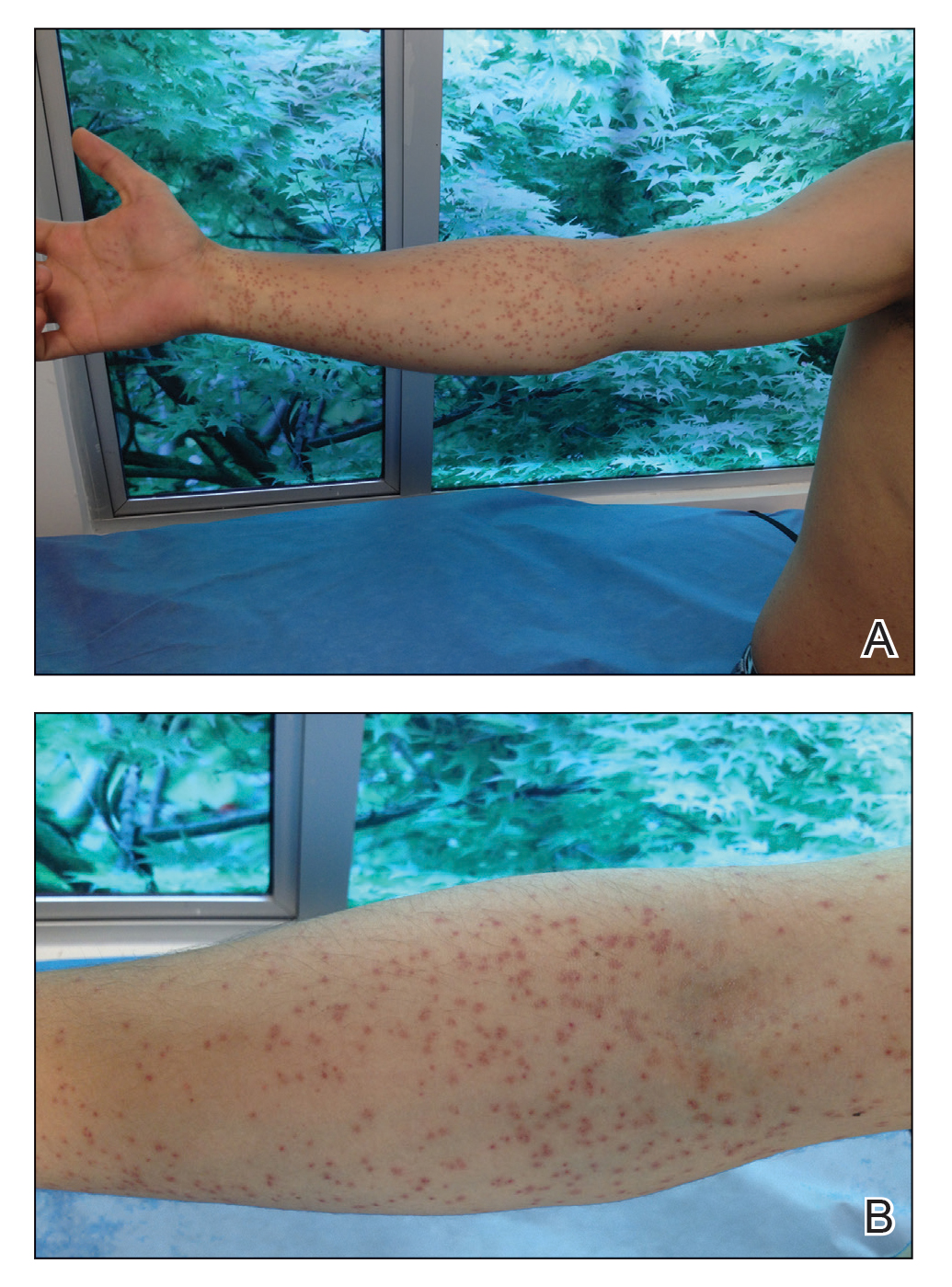

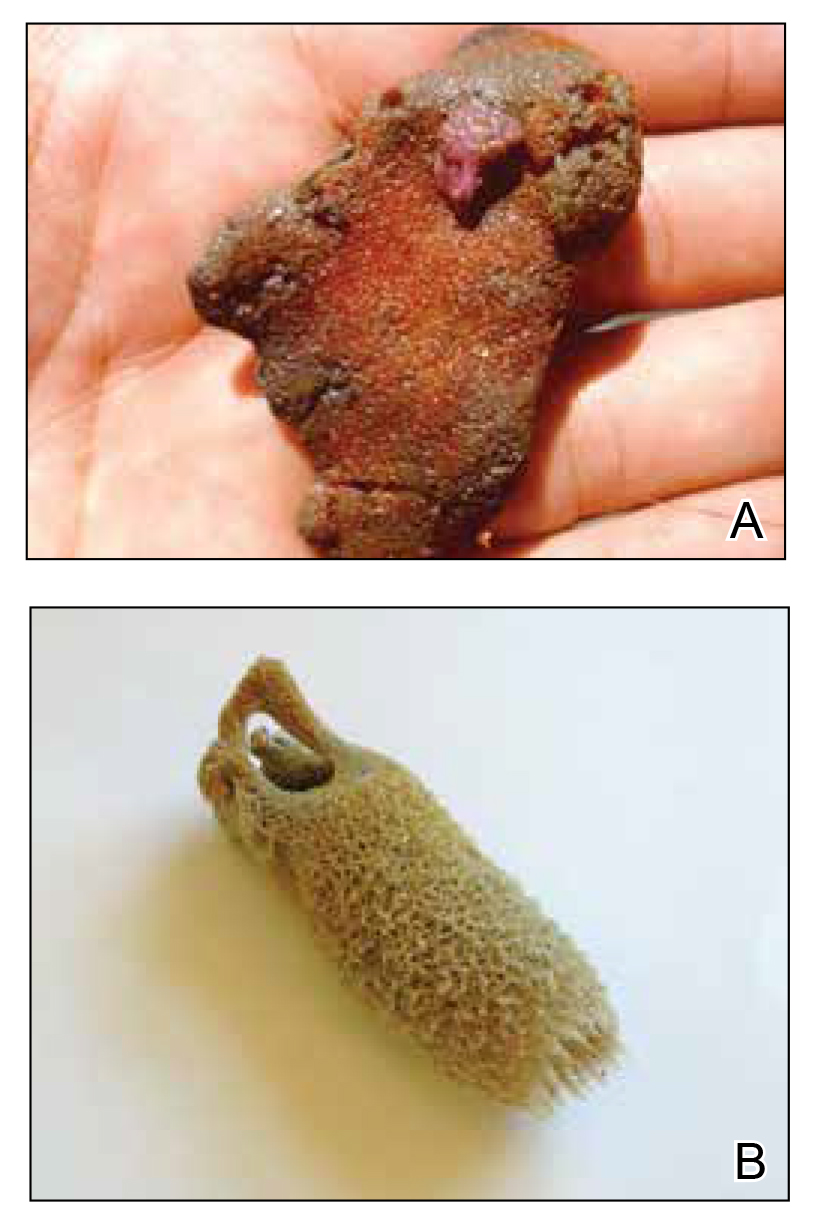

Stings: An Immediate Adverse Reaction—Depending on the venom, a sting might result in mild to severe burning pain, accompanied by welts, vesicles, and red papules or plaques.2 Figure 1 demonstrates a particularly mild sting from a caterpillar of the family Automeris, examples of which are seen in Figures 2 and 3 and eFigure 1. Components of the venom determine the mechanism of the sting and the pain that accompanies it. For example, a recent study demonstrated that the venom of the Latoia consocia caterpillar induces pain through the ion-channel receptor known as transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, which integrates and sends painful stimuli from the peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system.7 It is thought that a variety of ion channels are targets of the venom of caterpillars.

One of the most characteristic sting patterns is that of the caterpillar of family Megalopygidae (flannel moth)(eFigures 2 and 3). The stings of these caterpillars create a unique tram-track pattern of hemorrhagic macules or papules (Figure 4).4 A study found that 90% of reported M opercularis envenomations consist primarily of cutaneous symptoms, with 84% of those symptoms being irritation or pain; 45% a puncture or wound; 29% erythema; and 15% edema.3 Systemic findings can include headache, fever, adenopathy, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and chest pain.4 Symptoms normally are self-limited, though they can last minutes or hours.

Hypersensitivity Reaction—Studies demonstrate that the symptoms of this reaction are a mixture of type I hypersensitivity, type IV hypersensitivity, and a foreign-body response.2 The specific hypersensitivity reaction depends on the venom and the exposed individual—most commonly including a combination of pruritic papules, urticarial wheals, flares, and dermatitis.2 A reaction that is a result of direct contact with the caterpillar or moth will appear on exposed areas; however, because setae embed in linens and clothing, they might cause a reaction anywhere on the body. Although usually self-limited, a hypersensitivity reaction might develop within minutes and can last for days or weeks.

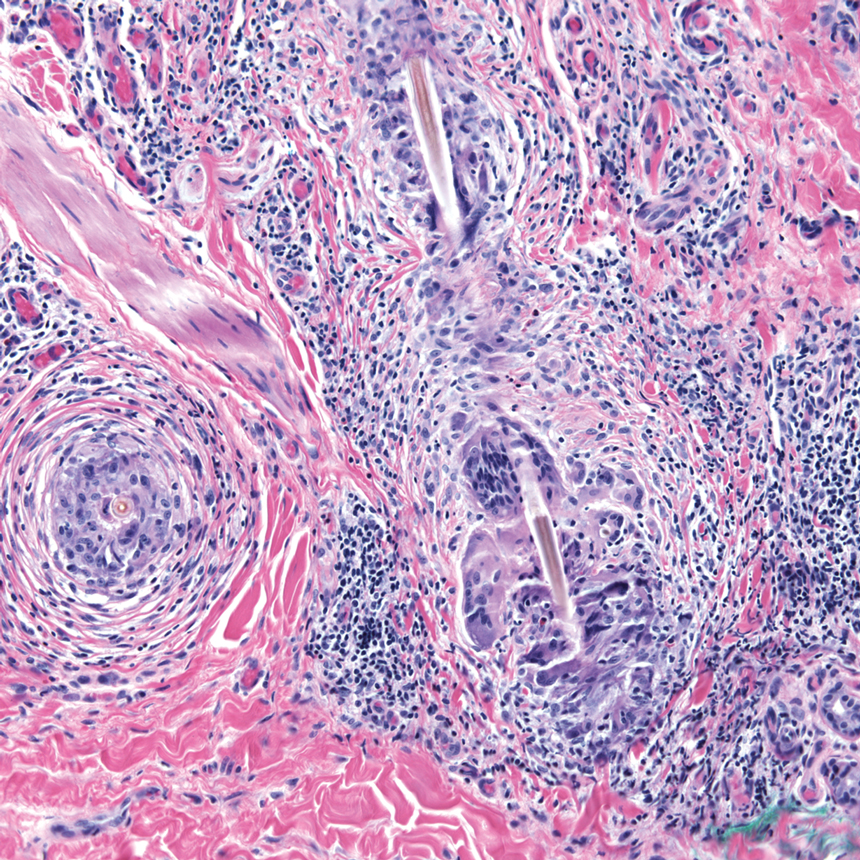

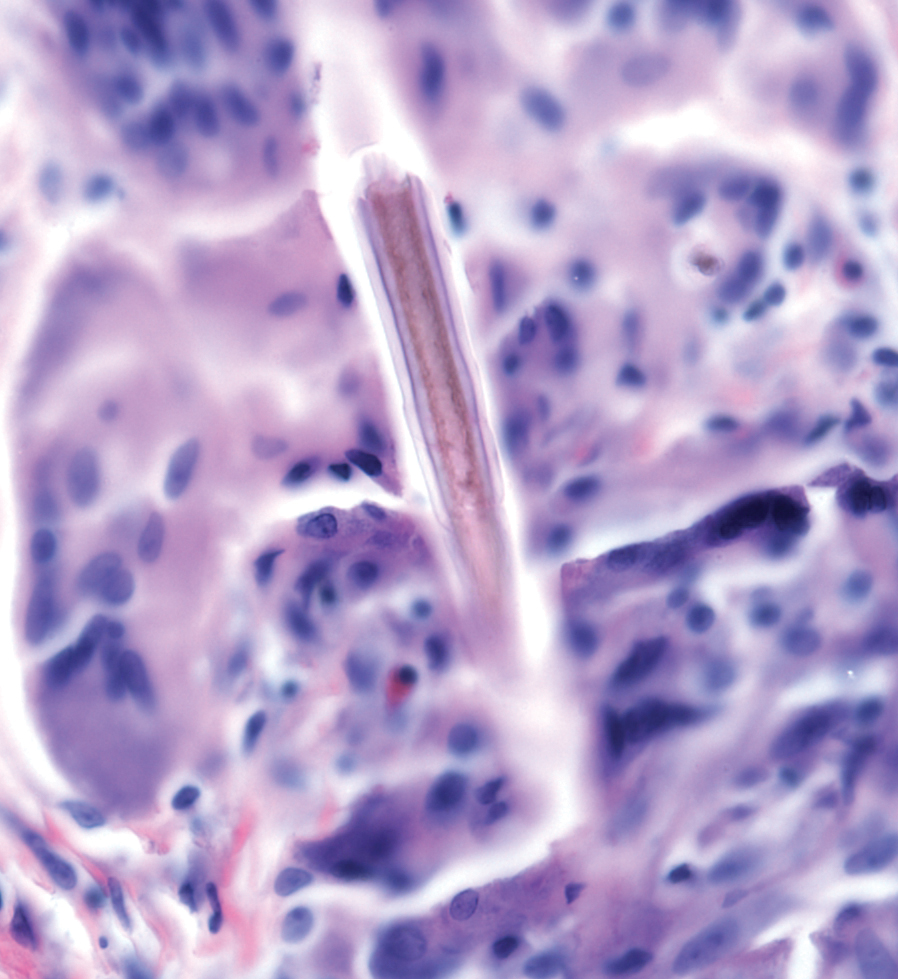

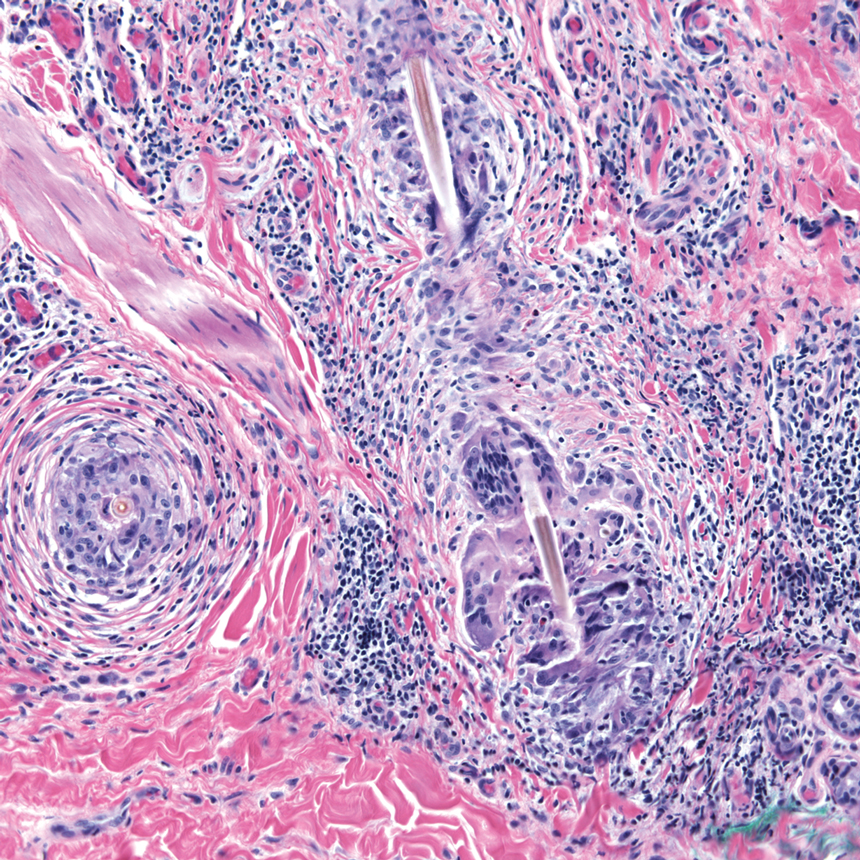

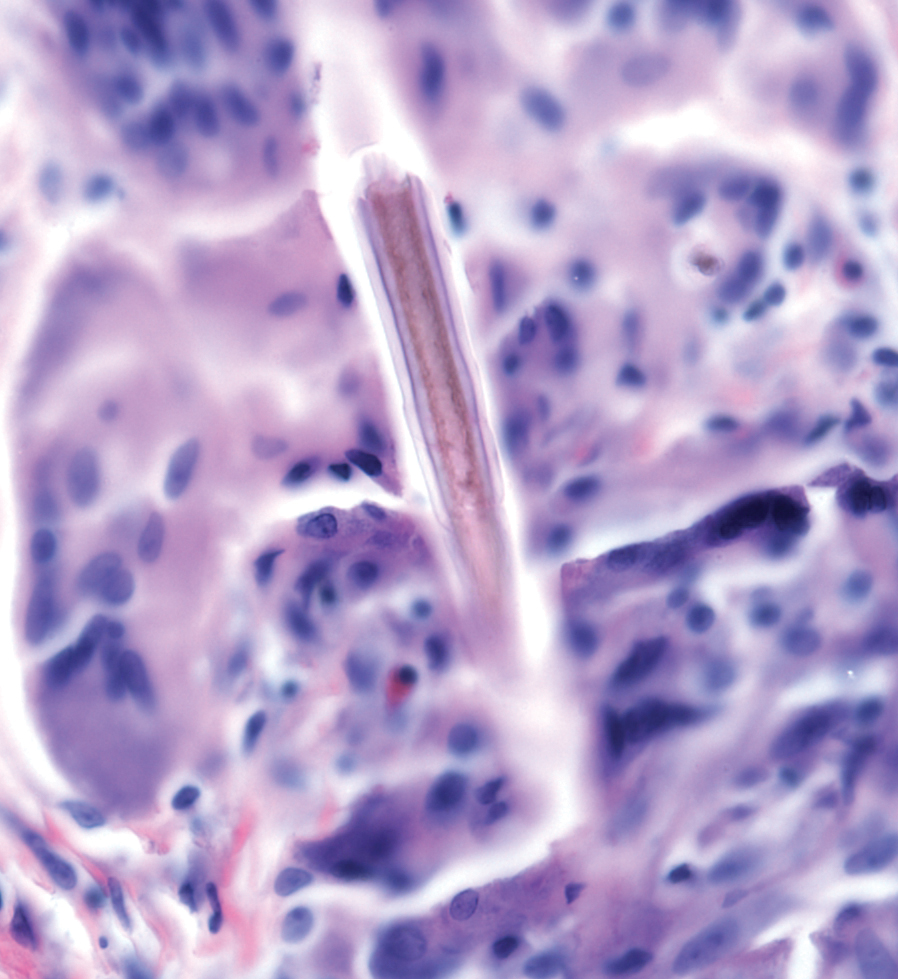

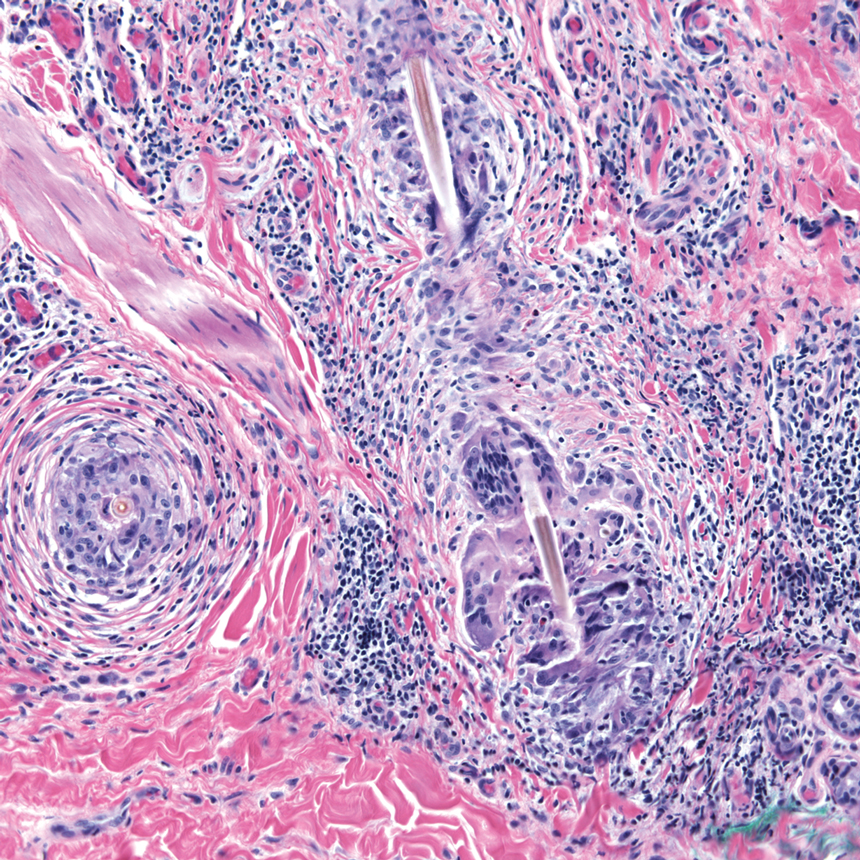

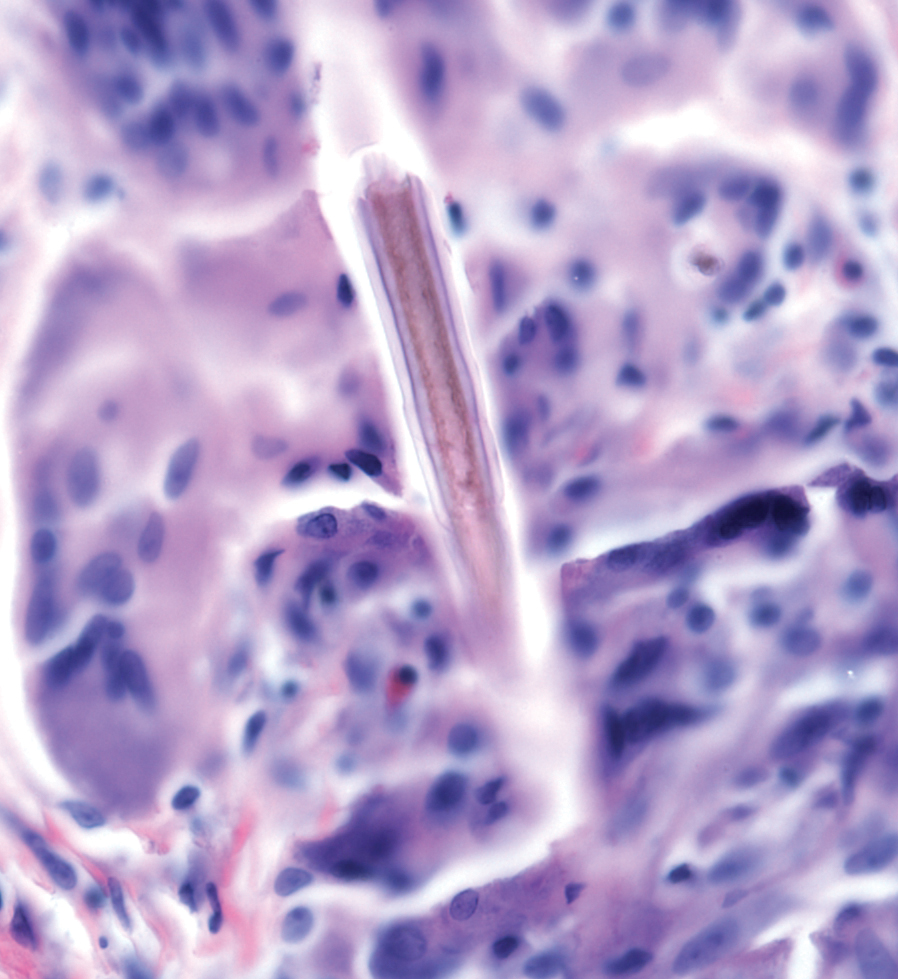

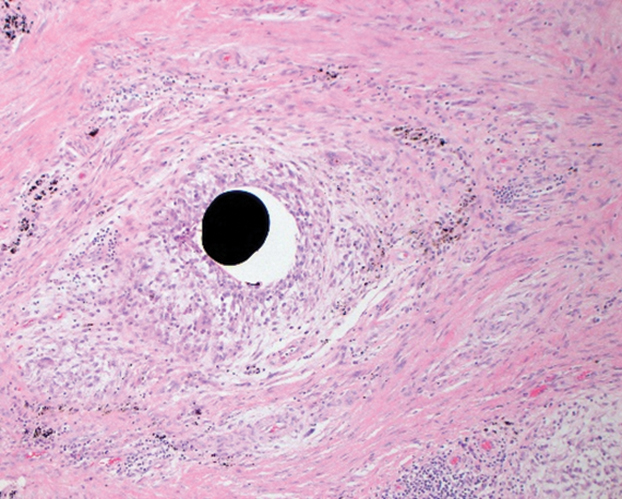

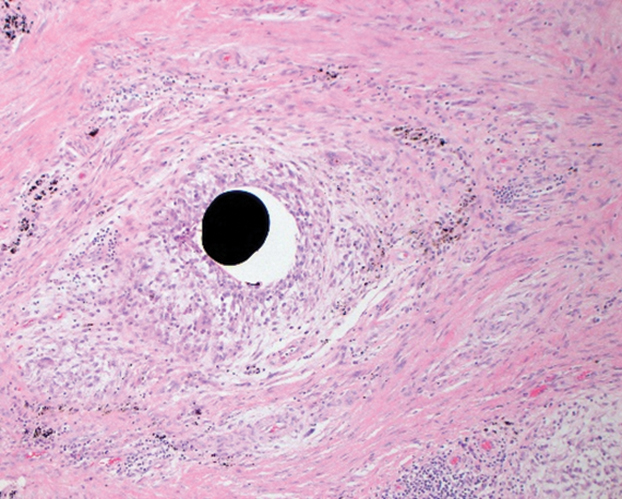

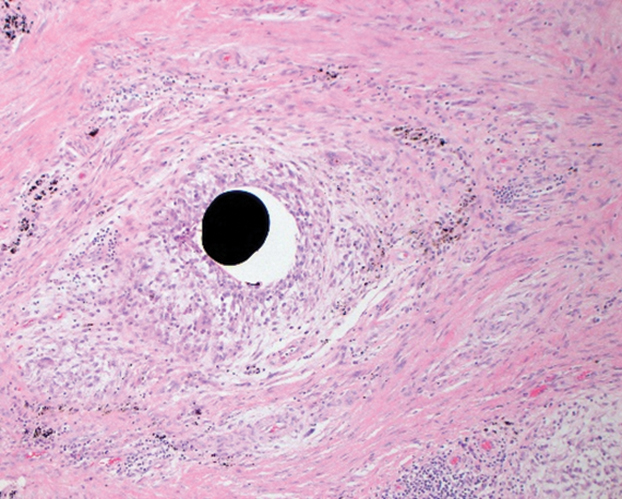

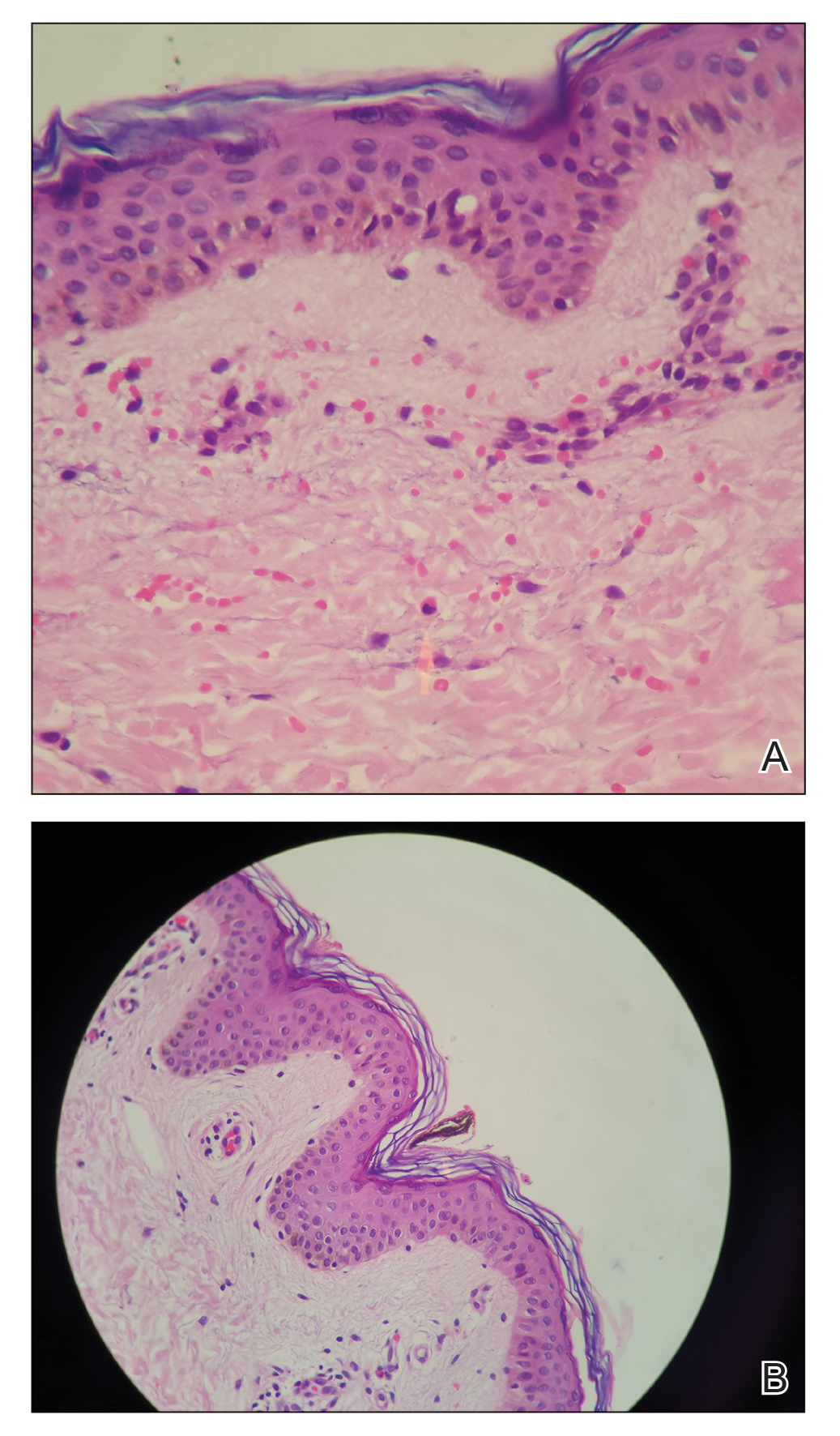

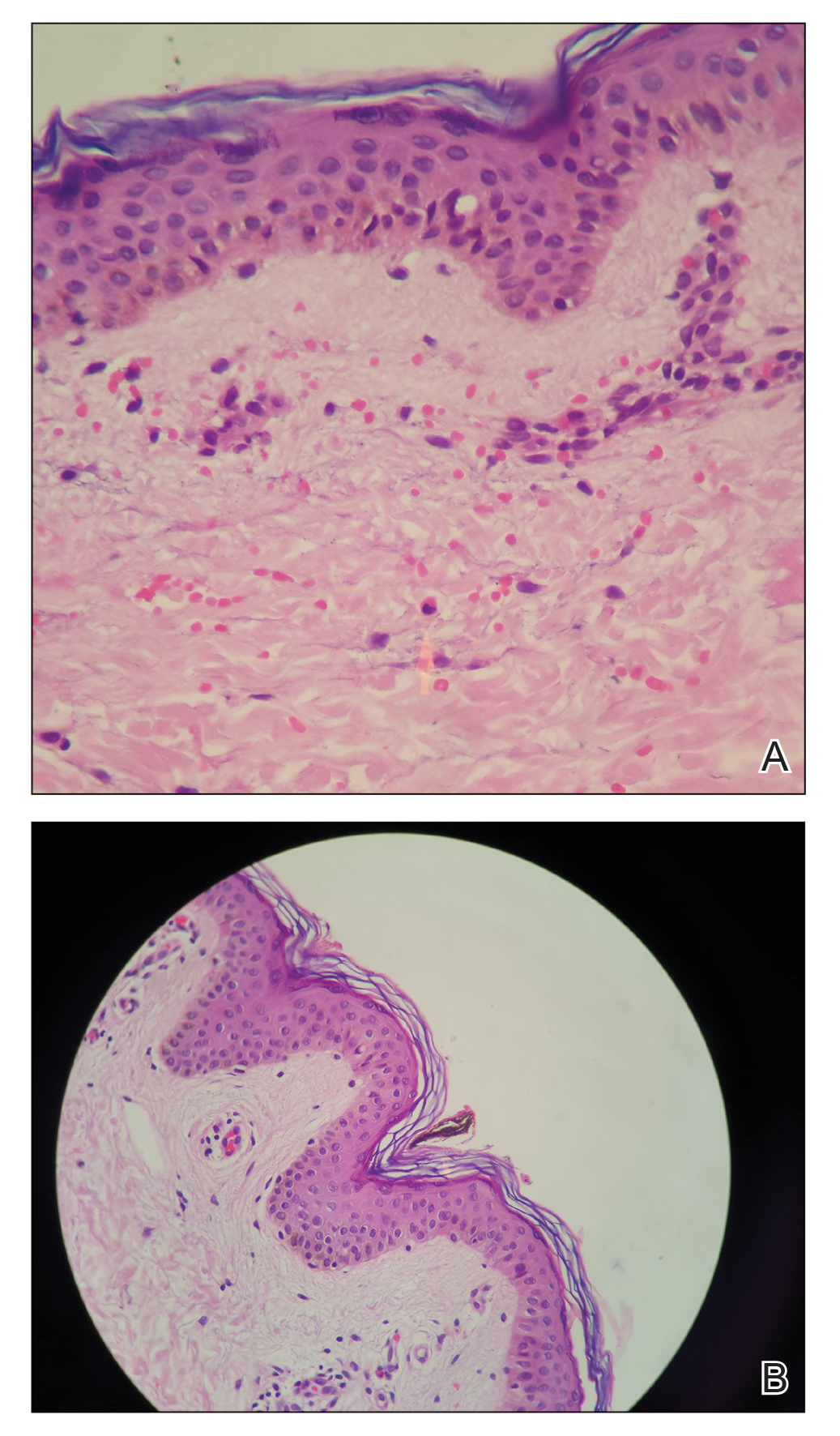

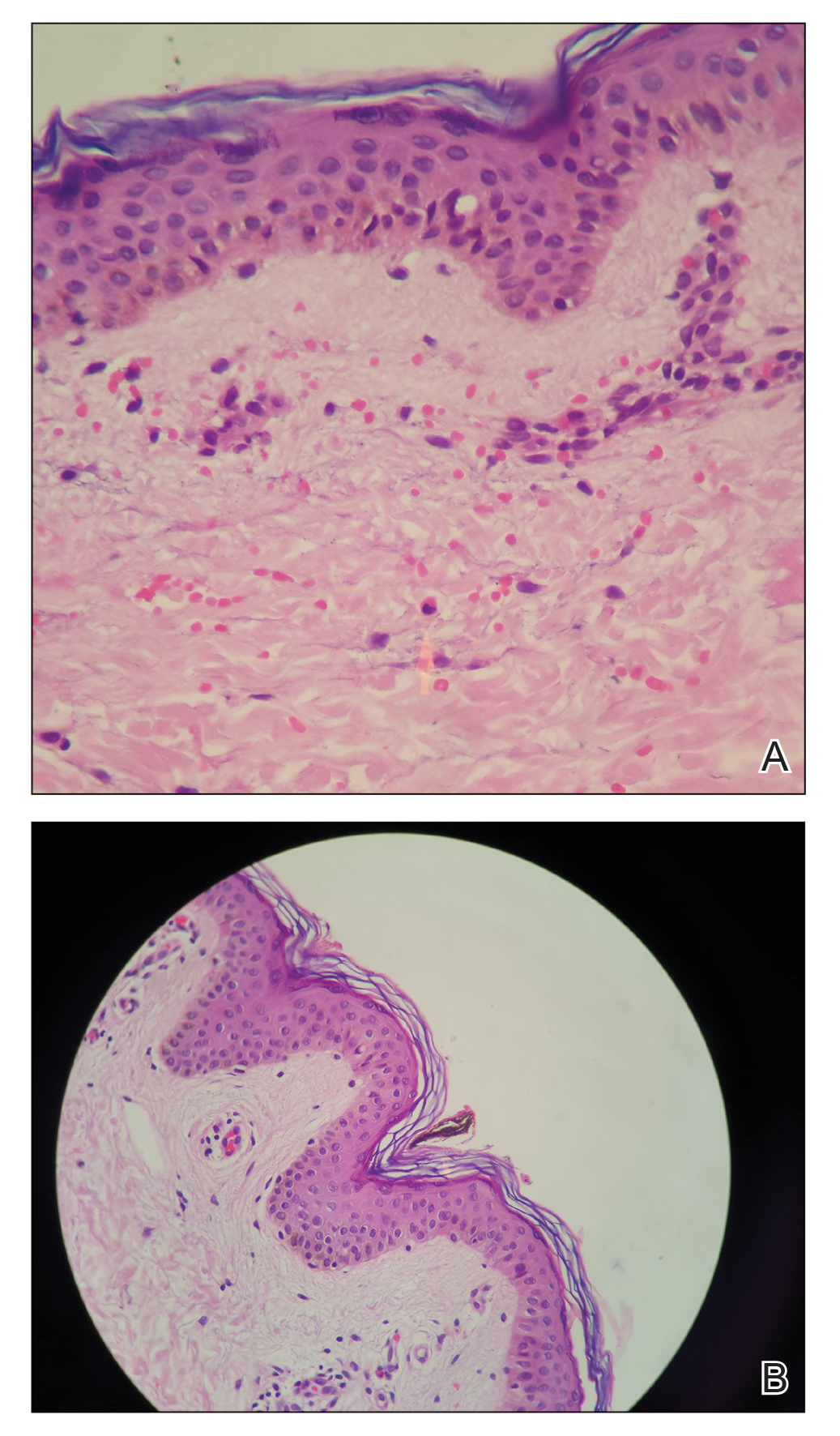

Stings and hypersensitivity reactions to caterpillars and moths tend to lead to a nonspecific histologic presentation characterized by epidermal edema and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, often with eosinophils.6 After approximately 1 week, a foreign-body response to setae can lead to tuberculoid granulomas accompanied by neutrophils in the dermis and occasionally in subcutaneous tissues (Figures 5 and 6).8 If setae have not yet been removed, they also might be visible in skin scrapings.

Additional complications can accompany the hypersensitivity reaction to setae or spines. Type I hypersensitivity reactions can lead to severe reactions on second contact due to previously sensitized IgE antibodies. Although the first reaction appears mild, second contact might result in angioedema, wheezing, dyspnea, or anaphylaxis, or a combination of these findings.9 In addition, some patients who come in contact with Dendrolimus caterpillars might develop a condition known as dendrolimiasis, characterized by dermatitis in addition to arthritis or chondritis.6 The arthritis is normally monoarticular and can result in complete destruction of the joint. Pararamose, a condition with a similar presentation, is caused by the Brazilian moth Premolis semirufa.6

Contact of setae or spines with mucous membranes or inhalation of setae also might result in edema, dysphagia, dyspnea, drooling, rhinitis, or conjunctivitis, or a combination of these findings.6 In addition, setae can embed in the eye and cause an inflammatory reaction—ophthalmia nodosa—most commonly caused by caterpillars of the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) and characterized by immediate chemosis, which can progress to liquefactive necrosis and hypopyon, later developing into a granulomatous foreign-body response.2,10 The process is thought to be the result of a combination of the thaumetopoein toxin in the setae and an IgE-mediated response to other proteins.10

Due to their harpoon shape and forward-only motion, setae might migrate deeper, potentially even to the optic nerve.11 Because migration might take years and the barbed shape of setae does not always allow removal, some patients require lifetime monitoring with slit-lamp examination.Chronic problems, such as cataracts and persistent posterior uveitis, have been reported.10,11

Lonomism—One of the most serious (though rarest) reactions to caterpillars is lonomism, a condition caused by the caterpillars of Lonomia achelous and Lonomia obliqua moths. These caterpillars have a unique combination of toxins filling their branched spines, which ultimately leads to the same outcome: a hemorrhagic diathesis.

The toxin of L achelous comprises several proteases that degrade fibrin, fibrinogen, and factor XIII while activating prothrombin. In contrast, L obliqua poison causes a hemorrhagic diathesis by promoting a consumptive coagulopathy through enzymes that activate factor X and prothrombin.

With initial contact with either of these Lonomia caterpillars, the patient experiences severe pain accompanied by systemic symptoms, including headache, nausea, and vomiting. Shortly afterward, symptoms of a hemorrhagic diathesis manifest, including bleeding gums, hematuria, bleeding from prior wounds, and epistaxis.5 Serious complications of the hemorrhagic diathesis, such as hemorrhage of major organs, leads to death in 4% of patients.5 A reported case of a patient whose Lonomia caterpillar sting went unrecognized until a week after the accident ended with progression to stage V chronic renal disease.12

Recent research has focused on the specific mechanism of injury caused by Lonomia species. A study found that the venom of L obliqua causes cytoskeleton rearrangement and migration in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) by inducing formation of reactive oxygen species through activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase.13 Thus, the venom directly contributes to the proinflammatory phenotype of endothelial cells seen following envenomation. The same study also demonstrated that elevated reactive oxygen species trigger extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway activation in VSMCs, leading to cell proliferation, re-stenosis, and ischemia.13 This finding was confirmed by another study,14 which demonstrated an increase in Rac1, a signaling protein involved in the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway, in VSMCs upon exposure to L obliqua venom. These studies propose potential new targets for treatment to prevent vascular damage.

Reactions to Adult Organisms—Although it is more common for the caterpillar form of these organisms to cause an adverse reaction, the adult moth also might be capable of causing a similar reaction by retaining setae from the cocoon or by their own spines. The most notable example of this is female moths of the genus Hylesia, which possess spines attached to glands on the abdomen. The poison in these spines—a mixture of proteases and chitinase—causes a dermatitis known as Caripito itch—the name derived from a river port in Venezuela where this moth caused a memorable epidemic of moth-induced dermatitis.7,15 Caripito itch is known for intense pruritus that most commonly lasts days or weeks, possibly longer than 1 year.

Diagnostic Difficulties

The challenge of diagnosing a caterpillar- or moth-induced reaction in humans arises from (1) the lack of clinical history (the caterpillar might not be seen at all by the patient or the examiner) and (2) the similarity of these reactions to those with more common triggers.

When setae remain embedded in the skin or mucous membranes, skin scrapings allow accelerated diagnosis. On a skin scraping prepared with 20% potassium hydroxide, setae appear as tapered and barbed hairlike structures, which allows them to be distinguished from other similar-appearing but differently shaped structures, such as glass fibers.

When setae do not remain embedded in the skin or when the cause of the reaction is due to spines, the physician is left with a nonspecific histologic picture and a large differential diagnosis to be narrowed down based on the history and occasionally the pattern of the skin lesion.

A challenge in sting diagnosis is differentiating a caterpillar or moth sting from that of another organism. In certain cases, such as those of the family Megalopygidae, specific patterns of stings might assist in making the diagnosis. Hypersensitivity reactions are associated with a wider differential diagnosis, including irritant or allergic dermatitis from other causes, scabies, eczema, lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea corporis, to name a few.6 Skin scrapings can be examined for other features, such as burrows in the case of scabies, to further narrow the differential.

Stings and hypersensitivity reactions lacking a proper history and associated with more severe systemic symptoms have caused misdiagnosis or led to a workup for the wrong condition; for example, the picture of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, leukocytosis, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis can simulate appendicitis.16 Upon discovery of a puss caterpillar sting in a patient, her symptoms resolved after treatment with ondansetron, morphine, and intravenous fluids.16

In lonomism, the diagnosis must be established by laboratory measurement of the fibrinogen level, clotting factors, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time.4 The differential diagnosis associated with lonomism includes disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), snakebite, and a hereditary bleeding disorder.4 The combination of laboratory tests and an extensive medical history allows a diagnosis. Absence of a personal or family history of bleeding excludes a diagnosis of hereditary bleeding disorder, whereas the absence of known causes of DIC or thrombocytopenia allows DIC to be excluded from the differential.

Treatment Options and Prevention

Treatment—The first step is to remove any embedded setae from the skin or mucous membranes. The stepwise recommendation is to remove any constricted clothing, detach setae with adhesive tape, wash with soap and water, and dry without touching the skin.1 Any remaining setae can be removed with additional tape or forceps; setae tend to be fragile and are difficult to remove in their entirety.

Other than removal of the setae, skin reactions are treated symptomatically. Ice packs and isopropyl alcohol have been utilized to cool burning or stinging areas. Pain, pruritus, and inflammation have been alleviated with antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.1 When pain is severe, oral codeine or local injection of anesthetic can be used. For severe and persistent skin lesions, a course of an oral glucocorticoid can be administered. Intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide has been shown to treat pain, dermatitis, and subcutaneous nodules otherwise refractory to treatment.8

Antivenin specific for L obliqua exists to treat lonomism and is therefore effective only when lonomism is caused by that species. Lonomism caused by L achelous is treated with cryoprecipitate, purified fibrinogen, and antifibrinolytic drugs, such as aprotinin.6 Whole blood and fresh-frozen plasma have been noted to make hemorrhage worse when utilized to treat lonomism. Because the mechanism of action of the venom of Lonomia species is based, in part, on inducing a proinflammatory profile in endothelial cells, studies have demonstrated that inhibition of kallikrein might prevent vascular injury and thus prevent serious adverse effects, such as renal failure.17

Prevention—People should wear proper protective clothing when outdoors in potentially infested areas. Measures should be taken to ensure that linens and clothing are not left outside in areas where setae might be carried on the wind. Infestation control is necessary if the population of caterpillars reaches a high enough level.

Conclusion

Several species of caterpillars and moths cause adverse reactions in humans: stings, hypersensitivity reactions, and lonomism. Although most reactions are self-limited, some might have more serious effects, including organ failure and death. Mechanisms of injury vary by species of caterpillar, moth, and butterfly; current research is focused on further defining venom components and signaling pathways to isolate potential targets to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of lepidopterism.

- Goldman BS, Bragg BN. Caterpillar and moth bites. Stat Pearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 3, 2021. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539851/

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. Dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.060

- Forrester MB. Megalopyge opercularis caterpillar stings reported to Texas poison centers. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29:215-220. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2018.02.002

- Hossler EW. Lepidopterism: skin disorders secondary to caterpillars and moths. UpToDate website. Published October 20, 2021. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lepidopterism-skin-disorders-secondary-to-caterpillars-and-moths

- Villas-Boas IM, Bonfá G, Tambourgi DV. Venomous caterpillars: from inoculation apparatus to venom composition and envenomation. Toxicon. 2018;153:39-52. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.08.007

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:13-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.061

- Yao Z, Kamau PM, Han Y, et al. The Latoia consocia caterpillar induces pain by targeting nociceptive ion channel TRPV1. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11:695. doi:10.3390/toxins11120695

- Paniz-Mondolfi AE, Pérez-Alvarez AM, Lundberg U, et al. Cutaneous lepidopterism: dermatitis from contact with moths of Hylesia metabus (Cramer 1775) (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae), the causative agent of caripito itch. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:535-541. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04683.x

- Santos-Magadán S, González de Olano D, Bartolomé-Zavala B, et al. Adverse reactions to the processionary caterpillar: irritant or allergic mechanism? Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:109-110. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01464.x

- González-Martín-Moro J, Contreras-Martín I, Castro-Rebollo M, et al. Focal cortical cataract due to caterpillar hair migration. Clin Exp Optom. 2019;102:89-90. doi:10.1111/cxo.12809

- Singh A, Behera UC, Agrawal H. Intra-lenticular caterpillar seta in ophthalmia nodosa. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31:NP109-NP111. doi:10.1177/1120672119858899

- Schmitberger PA, Fernandes TC, Santos RC, et al. Probable chronic renal failure caused by Lonomia caterpillar envenomation. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2013;19:14. doi:10.1186/1678-9199-19-14

- Moraes JA, Rodrigues G, Nascimento-Silva V, et al. Effects of Lonomia obliqua venom on vascular smooth muscle cells: contribution of NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9:360. doi:10.3390/toxins9110360

- Bernardi L, Pinto AFM, Mendes E, et al. Lonomia obliqua bristle extract modulates Rac1 activation, membrane dynamics and cell adhesion properties. Toxicon. 2019;162:32-39. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.019

- Cabrera G, Lundberg U, Rodríguez-Ulloa A, et al. Protein content of the Hylesia metabus egg nest setae (Cramer [1775]) (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) and its association with the parental investment for the reproductive success and lepidopterism. J Proteomics. 2017;150:183-200. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2016.08.010

- Greene SC, Carey JM. Puss caterpillar envenomation: erucism mimicking appendicitis in a young child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E732-E734. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001514

- Berger M, de Moraes JA, Beys-da-Silva WO, et al. Renal and vascular effects of kallikrein inhibition in a model of Lonomia obliqua venom-induced acute kidney injury. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007197. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007197

Causes of Lepidopterism

Caterpillars are wormlike organisms that serve as the larval stage of moths and butterflies, which belong to the order Lepidoptera. There are almost 165,000 discovered species, with 13,000 found in the United States.1,2 Roughly 150 species are known to have the potential to cause an adverse reaction in humans, with 50 of these in the United States.1Lepidopterism describes systemic and cutaneous reactions to moths, butterflies, and caterpillars; erucism describes strictly cutaneous reactions.1

Although the rate of lepidopterism is thought to be underreported because it often is self-limited and of a mild nature, a review found caterpillars to be the cause of roughly 2.2% of reported bites and stings annually.2 Cases increase in number with seasonal increases in caterpillars, which vary by region and species. For example, the Megalopyge opercularis (southern flannel moth) caterpillar was noted to have 2 peaks in a Texas-based study: 12% of reported stings occurred in July; 59% from October through November.3 In general, the likelihood of exposure increases during warmer months, and exposure is more common in people who work outdoors in a rural area or in a suburban area where there are many caterpillar-infested trees.4

Most cases of lepidopterism are caused by caterpillars, not by adult butterflies and moths, because the former have many tubular, or porous, hairlike structures called setae that are embedded in the integument. Setae were once thought to be connected to poison-secreting glandular cells, but current belief is that venomous caterpillars lack specialized gland cells and instead produce venom through secretory epithelial cells located above the integument.1 Venom accumulates in the hemolymph and is stored in the setae or other types of bristles, such as scoli (wartlike bumps that bear setae) or spines.5 With a large amount of chitin, bristles have a tendency to fracture and release venom upon contact.1 It is thought that some species of caterpillars formulate venom by ingesting toxins or toxin precursors from plants; for example, the tiger moth (family Arctiidae) is known to produce venom containing biogenic amines, pyrrolizidine, alkaloids, and cardiac glycosides obtained through food sources.5

Even if a caterpillar does not produce venom, its setae might embed into skin or mucous membranes and cause an adverse irritant reaction.1 Setae also might dislodge and be transported in the air to embed in objects—some remaining stable in the environment for longer than a year.2 In contrast to setae, spines are permanently fixed into the integument; for that reason, only direct contact with the caterpillar can result in an adverse reaction. Although it is mostly caterpillars that contain setae and spines, certain species of moths also might contain these structures or might acquire them as they emerge from the cocoon, which often contains incorporated setae.2

Reactions in Humans

Lepidopterism encompasses 3 principal reactions in humans: sting reaction, hypersensitivity reaction, and lonomism (a hemorrhagic diathesis produced by Lonomia caterpillars). The type and severity of the reaction depends on (1) the species of caterpillar or moth and (2) the individual patient.2 There are approximately 12 families of caterpillars, mainly of the moth variety, that can cause an adverse reaction in humans.1 Tables 1 and 2 list examples of species that cause each type of reaction.6

Chemicals and toxins contained in the poison of setae and spines vary by species of caterpillar. Numerous kinds have been isolated from different venoms,1,2 including several peptides, histamine, histamine-releasing substances, acetylcholine, phospholipase A, hyaluronidase, formic acid, proteins with trypsinlike activity, serine proteases such as kallikrein, and other enzymes with vasodegenerative and fibrinolytic properties

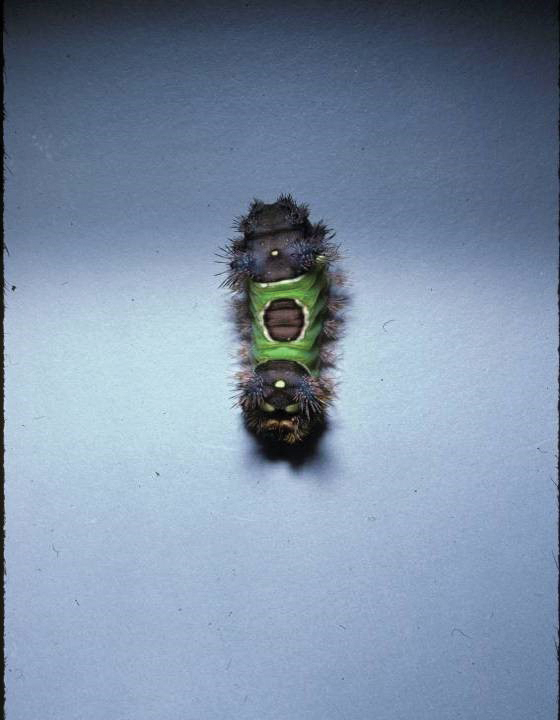

Stings: An Immediate Adverse Reaction—Depending on the venom, a sting might result in mild to severe burning pain, accompanied by welts, vesicles, and red papules or plaques.2 Figure 1 demonstrates a particularly mild sting from a caterpillar of the family Automeris, examples of which are seen in Figures 2 and 3 and eFigure 1. Components of the venom determine the mechanism of the sting and the pain that accompanies it. For example, a recent study demonstrated that the venom of the Latoia consocia caterpillar induces pain through the ion-channel receptor known as transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, which integrates and sends painful stimuli from the peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system.7 It is thought that a variety of ion channels are targets of the venom of caterpillars.

One of the most characteristic sting patterns is that of the caterpillar of family Megalopygidae (flannel moth)(eFigures 2 and 3). The stings of these caterpillars create a unique tram-track pattern of hemorrhagic macules or papules (Figure 4).4 A study found that 90% of reported M opercularis envenomations consist primarily of cutaneous symptoms, with 84% of those symptoms being irritation or pain; 45% a puncture or wound; 29% erythema; and 15% edema.3 Systemic findings can include headache, fever, adenopathy, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and chest pain.4 Symptoms normally are self-limited, though they can last minutes or hours.

Hypersensitivity Reaction—Studies demonstrate that the symptoms of this reaction are a mixture of type I hypersensitivity, type IV hypersensitivity, and a foreign-body response.2 The specific hypersensitivity reaction depends on the venom and the exposed individual—most commonly including a combination of pruritic papules, urticarial wheals, flares, and dermatitis.2 A reaction that is a result of direct contact with the caterpillar or moth will appear on exposed areas; however, because setae embed in linens and clothing, they might cause a reaction anywhere on the body. Although usually self-limited, a hypersensitivity reaction might develop within minutes and can last for days or weeks.

Stings and hypersensitivity reactions to caterpillars and moths tend to lead to a nonspecific histologic presentation characterized by epidermal edema and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, often with eosinophils.6 After approximately 1 week, a foreign-body response to setae can lead to tuberculoid granulomas accompanied by neutrophils in the dermis and occasionally in subcutaneous tissues (Figures 5 and 6).8 If setae have not yet been removed, they also might be visible in skin scrapings.

Additional complications can accompany the hypersensitivity reaction to setae or spines. Type I hypersensitivity reactions can lead to severe reactions on second contact due to previously sensitized IgE antibodies. Although the first reaction appears mild, second contact might result in angioedema, wheezing, dyspnea, or anaphylaxis, or a combination of these findings.9 In addition, some patients who come in contact with Dendrolimus caterpillars might develop a condition known as dendrolimiasis, characterized by dermatitis in addition to arthritis or chondritis.6 The arthritis is normally monoarticular and can result in complete destruction of the joint. Pararamose, a condition with a similar presentation, is caused by the Brazilian moth Premolis semirufa.6

Contact of setae or spines with mucous membranes or inhalation of setae also might result in edema, dysphagia, dyspnea, drooling, rhinitis, or conjunctivitis, or a combination of these findings.6 In addition, setae can embed in the eye and cause an inflammatory reaction—ophthalmia nodosa—most commonly caused by caterpillars of the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) and characterized by immediate chemosis, which can progress to liquefactive necrosis and hypopyon, later developing into a granulomatous foreign-body response.2,10 The process is thought to be the result of a combination of the thaumetopoein toxin in the setae and an IgE-mediated response to other proteins.10

Due to their harpoon shape and forward-only motion, setae might migrate deeper, potentially even to the optic nerve.11 Because migration might take years and the barbed shape of setae does not always allow removal, some patients require lifetime monitoring with slit-lamp examination.Chronic problems, such as cataracts and persistent posterior uveitis, have been reported.10,11

Lonomism—One of the most serious (though rarest) reactions to caterpillars is lonomism, a condition caused by the caterpillars of Lonomia achelous and Lonomia obliqua moths. These caterpillars have a unique combination of toxins filling their branched spines, which ultimately leads to the same outcome: a hemorrhagic diathesis.

The toxin of L achelous comprises several proteases that degrade fibrin, fibrinogen, and factor XIII while activating prothrombin. In contrast, L obliqua poison causes a hemorrhagic diathesis by promoting a consumptive coagulopathy through enzymes that activate factor X and prothrombin.

With initial contact with either of these Lonomia caterpillars, the patient experiences severe pain accompanied by systemic symptoms, including headache, nausea, and vomiting. Shortly afterward, symptoms of a hemorrhagic diathesis manifest, including bleeding gums, hematuria, bleeding from prior wounds, and epistaxis.5 Serious complications of the hemorrhagic diathesis, such as hemorrhage of major organs, leads to death in 4% of patients.5 A reported case of a patient whose Lonomia caterpillar sting went unrecognized until a week after the accident ended with progression to stage V chronic renal disease.12

Recent research has focused on the specific mechanism of injury caused by Lonomia species. A study found that the venom of L obliqua causes cytoskeleton rearrangement and migration in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) by inducing formation of reactive oxygen species through activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase.13 Thus, the venom directly contributes to the proinflammatory phenotype of endothelial cells seen following envenomation. The same study also demonstrated that elevated reactive oxygen species trigger extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway activation in VSMCs, leading to cell proliferation, re-stenosis, and ischemia.13 This finding was confirmed by another study,14 which demonstrated an increase in Rac1, a signaling protein involved in the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway, in VSMCs upon exposure to L obliqua venom. These studies propose potential new targets for treatment to prevent vascular damage.

Reactions to Adult Organisms—Although it is more common for the caterpillar form of these organisms to cause an adverse reaction, the adult moth also might be capable of causing a similar reaction by retaining setae from the cocoon or by their own spines. The most notable example of this is female moths of the genus Hylesia, which possess spines attached to glands on the abdomen. The poison in these spines—a mixture of proteases and chitinase—causes a dermatitis known as Caripito itch—the name derived from a river port in Venezuela where this moth caused a memorable epidemic of moth-induced dermatitis.7,15 Caripito itch is known for intense pruritus that most commonly lasts days or weeks, possibly longer than 1 year.

Diagnostic Difficulties

The challenge of diagnosing a caterpillar- or moth-induced reaction in humans arises from (1) the lack of clinical history (the caterpillar might not be seen at all by the patient or the examiner) and (2) the similarity of these reactions to those with more common triggers.

When setae remain embedded in the skin or mucous membranes, skin scrapings allow accelerated diagnosis. On a skin scraping prepared with 20% potassium hydroxide, setae appear as tapered and barbed hairlike structures, which allows them to be distinguished from other similar-appearing but differently shaped structures, such as glass fibers.

When setae do not remain embedded in the skin or when the cause of the reaction is due to spines, the physician is left with a nonspecific histologic picture and a large differential diagnosis to be narrowed down based on the history and occasionally the pattern of the skin lesion.

A challenge in sting diagnosis is differentiating a caterpillar or moth sting from that of another organism. In certain cases, such as those of the family Megalopygidae, specific patterns of stings might assist in making the diagnosis. Hypersensitivity reactions are associated with a wider differential diagnosis, including irritant or allergic dermatitis from other causes, scabies, eczema, lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea corporis, to name a few.6 Skin scrapings can be examined for other features, such as burrows in the case of scabies, to further narrow the differential.

Stings and hypersensitivity reactions lacking a proper history and associated with more severe systemic symptoms have caused misdiagnosis or led to a workup for the wrong condition; for example, the picture of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, leukocytosis, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis can simulate appendicitis.16 Upon discovery of a puss caterpillar sting in a patient, her symptoms resolved after treatment with ondansetron, morphine, and intravenous fluids.16

In lonomism, the diagnosis must be established by laboratory measurement of the fibrinogen level, clotting factors, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time.4 The differential diagnosis associated with lonomism includes disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), snakebite, and a hereditary bleeding disorder.4 The combination of laboratory tests and an extensive medical history allows a diagnosis. Absence of a personal or family history of bleeding excludes a diagnosis of hereditary bleeding disorder, whereas the absence of known causes of DIC or thrombocytopenia allows DIC to be excluded from the differential.

Treatment Options and Prevention

Treatment—The first step is to remove any embedded setae from the skin or mucous membranes. The stepwise recommendation is to remove any constricted clothing, detach setae with adhesive tape, wash with soap and water, and dry without touching the skin.1 Any remaining setae can be removed with additional tape or forceps; setae tend to be fragile and are difficult to remove in their entirety.

Other than removal of the setae, skin reactions are treated symptomatically. Ice packs and isopropyl alcohol have been utilized to cool burning or stinging areas. Pain, pruritus, and inflammation have been alleviated with antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.1 When pain is severe, oral codeine or local injection of anesthetic can be used. For severe and persistent skin lesions, a course of an oral glucocorticoid can be administered. Intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide has been shown to treat pain, dermatitis, and subcutaneous nodules otherwise refractory to treatment.8

Antivenin specific for L obliqua exists to treat lonomism and is therefore effective only when lonomism is caused by that species. Lonomism caused by L achelous is treated with cryoprecipitate, purified fibrinogen, and antifibrinolytic drugs, such as aprotinin.6 Whole blood and fresh-frozen plasma have been noted to make hemorrhage worse when utilized to treat lonomism. Because the mechanism of action of the venom of Lonomia species is based, in part, on inducing a proinflammatory profile in endothelial cells, studies have demonstrated that inhibition of kallikrein might prevent vascular injury and thus prevent serious adverse effects, such as renal failure.17

Prevention—People should wear proper protective clothing when outdoors in potentially infested areas. Measures should be taken to ensure that linens and clothing are not left outside in areas where setae might be carried on the wind. Infestation control is necessary if the population of caterpillars reaches a high enough level.

Conclusion

Several species of caterpillars and moths cause adverse reactions in humans: stings, hypersensitivity reactions, and lonomism. Although most reactions are self-limited, some might have more serious effects, including organ failure and death. Mechanisms of injury vary by species of caterpillar, moth, and butterfly; current research is focused on further defining venom components and signaling pathways to isolate potential targets to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of lepidopterism.

Causes of Lepidopterism

Caterpillars are wormlike organisms that serve as the larval stage of moths and butterflies, which belong to the order Lepidoptera. There are almost 165,000 discovered species, with 13,000 found in the United States.1,2 Roughly 150 species are known to have the potential to cause an adverse reaction in humans, with 50 of these in the United States.1Lepidopterism describes systemic and cutaneous reactions to moths, butterflies, and caterpillars; erucism describes strictly cutaneous reactions.1

Although the rate of lepidopterism is thought to be underreported because it often is self-limited and of a mild nature, a review found caterpillars to be the cause of roughly 2.2% of reported bites and stings annually.2 Cases increase in number with seasonal increases in caterpillars, which vary by region and species. For example, the Megalopyge opercularis (southern flannel moth) caterpillar was noted to have 2 peaks in a Texas-based study: 12% of reported stings occurred in July; 59% from October through November.3 In general, the likelihood of exposure increases during warmer months, and exposure is more common in people who work outdoors in a rural area or in a suburban area where there are many caterpillar-infested trees.4

Most cases of lepidopterism are caused by caterpillars, not by adult butterflies and moths, because the former have many tubular, or porous, hairlike structures called setae that are embedded in the integument. Setae were once thought to be connected to poison-secreting glandular cells, but current belief is that venomous caterpillars lack specialized gland cells and instead produce venom through secretory epithelial cells located above the integument.1 Venom accumulates in the hemolymph and is stored in the setae or other types of bristles, such as scoli (wartlike bumps that bear setae) or spines.5 With a large amount of chitin, bristles have a tendency to fracture and release venom upon contact.1 It is thought that some species of caterpillars formulate venom by ingesting toxins or toxin precursors from plants; for example, the tiger moth (family Arctiidae) is known to produce venom containing biogenic amines, pyrrolizidine, alkaloids, and cardiac glycosides obtained through food sources.5

Even if a caterpillar does not produce venom, its setae might embed into skin or mucous membranes and cause an adverse irritant reaction.1 Setae also might dislodge and be transported in the air to embed in objects—some remaining stable in the environment for longer than a year.2 In contrast to setae, spines are permanently fixed into the integument; for that reason, only direct contact with the caterpillar can result in an adverse reaction. Although it is mostly caterpillars that contain setae and spines, certain species of moths also might contain these structures or might acquire them as they emerge from the cocoon, which often contains incorporated setae.2

Reactions in Humans

Lepidopterism encompasses 3 principal reactions in humans: sting reaction, hypersensitivity reaction, and lonomism (a hemorrhagic diathesis produced by Lonomia caterpillars). The type and severity of the reaction depends on (1) the species of caterpillar or moth and (2) the individual patient.2 There are approximately 12 families of caterpillars, mainly of the moth variety, that can cause an adverse reaction in humans.1 Tables 1 and 2 list examples of species that cause each type of reaction.6

Chemicals and toxins contained in the poison of setae and spines vary by species of caterpillar. Numerous kinds have been isolated from different venoms,1,2 including several peptides, histamine, histamine-releasing substances, acetylcholine, phospholipase A, hyaluronidase, formic acid, proteins with trypsinlike activity, serine proteases such as kallikrein, and other enzymes with vasodegenerative and fibrinolytic properties

Stings: An Immediate Adverse Reaction—Depending on the venom, a sting might result in mild to severe burning pain, accompanied by welts, vesicles, and red papules or plaques.2 Figure 1 demonstrates a particularly mild sting from a caterpillar of the family Automeris, examples of which are seen in Figures 2 and 3 and eFigure 1. Components of the venom determine the mechanism of the sting and the pain that accompanies it. For example, a recent study demonstrated that the venom of the Latoia consocia caterpillar induces pain through the ion-channel receptor known as transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, which integrates and sends painful stimuli from the peripheral nervous system to the central nervous system.7 It is thought that a variety of ion channels are targets of the venom of caterpillars.

One of the most characteristic sting patterns is that of the caterpillar of family Megalopygidae (flannel moth)(eFigures 2 and 3). The stings of these caterpillars create a unique tram-track pattern of hemorrhagic macules or papules (Figure 4).4 A study found that 90% of reported M opercularis envenomations consist primarily of cutaneous symptoms, with 84% of those symptoms being irritation or pain; 45% a puncture or wound; 29% erythema; and 15% edema.3 Systemic findings can include headache, fever, adenopathy, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and chest pain.4 Symptoms normally are self-limited, though they can last minutes or hours.

Hypersensitivity Reaction—Studies demonstrate that the symptoms of this reaction are a mixture of type I hypersensitivity, type IV hypersensitivity, and a foreign-body response.2 The specific hypersensitivity reaction depends on the venom and the exposed individual—most commonly including a combination of pruritic papules, urticarial wheals, flares, and dermatitis.2 A reaction that is a result of direct contact with the caterpillar or moth will appear on exposed areas; however, because setae embed in linens and clothing, they might cause a reaction anywhere on the body. Although usually self-limited, a hypersensitivity reaction might develop within minutes and can last for days or weeks.

Stings and hypersensitivity reactions to caterpillars and moths tend to lead to a nonspecific histologic presentation characterized by epidermal edema and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, often with eosinophils.6 After approximately 1 week, a foreign-body response to setae can lead to tuberculoid granulomas accompanied by neutrophils in the dermis and occasionally in subcutaneous tissues (Figures 5 and 6).8 If setae have not yet been removed, they also might be visible in skin scrapings.

Additional complications can accompany the hypersensitivity reaction to setae or spines. Type I hypersensitivity reactions can lead to severe reactions on second contact due to previously sensitized IgE antibodies. Although the first reaction appears mild, second contact might result in angioedema, wheezing, dyspnea, or anaphylaxis, or a combination of these findings.9 In addition, some patients who come in contact with Dendrolimus caterpillars might develop a condition known as dendrolimiasis, characterized by dermatitis in addition to arthritis or chondritis.6 The arthritis is normally monoarticular and can result in complete destruction of the joint. Pararamose, a condition with a similar presentation, is caused by the Brazilian moth Premolis semirufa.6

Contact of setae or spines with mucous membranes or inhalation of setae also might result in edema, dysphagia, dyspnea, drooling, rhinitis, or conjunctivitis, or a combination of these findings.6 In addition, setae can embed in the eye and cause an inflammatory reaction—ophthalmia nodosa—most commonly caused by caterpillars of the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) and characterized by immediate chemosis, which can progress to liquefactive necrosis and hypopyon, later developing into a granulomatous foreign-body response.2,10 The process is thought to be the result of a combination of the thaumetopoein toxin in the setae and an IgE-mediated response to other proteins.10

Due to their harpoon shape and forward-only motion, setae might migrate deeper, potentially even to the optic nerve.11 Because migration might take years and the barbed shape of setae does not always allow removal, some patients require lifetime monitoring with slit-lamp examination.Chronic problems, such as cataracts and persistent posterior uveitis, have been reported.10,11