User login

Welcome Editorial

It’s an honor and a great pleasure to take on this new role as editor in chief for Hematology News. When I got the call from our outgoing editor Matt Kalaycio, MD, a year ago asking me to consider stepping into his shoes a few things flashed through my mind. Will I do this role justice? Do I have what it takes to be a great editor in chief?

Then I thought – will there be time to learn the ropes or will this be like most of my career positions where you jump into the water first and figure out how to swim later? I never once thought: “Oh no … I cannot do this and I’m going to say no!” So here I am today, reporting for duty as the editor in chief of Hematology News.

I was once accused of being “intellectually restless” which is a badge I wear with honor and is perhaps a trait I learned from my mom who was a public health nurse in Nigeria back in the seventies. She broke a lot of glass ceilings in her day – Cornell University–trained advanced practice nurse, mother of five girls, with a degree in textile and design and business accounting. She also got a certificate in baking and cake decorating and she used all her skills and certifications to raise her daughters to believe the sky was the limit.

Mom started one of the first licensed practical nursing (LPN) schools in Nigeria and I learned from her to never back down from a challenge – on a dare I got my LPN certification before I went to medical school.

You see I love a challenge and an adventure and serving as the editor in chief for Hematology News provides me with an amazing platform and opportunity to achieve a lot of firsts and satisfy that hunger to make a global difference that has always guided my career.

I’ve thought long and hard about what and how I envision this role shaping out. What do I want our readers to take away from this newspaper under my leadership? What common themes will be woven in every edition? I want our readers to be challenged and keep learning. Not just about hematologic disorders and the latest scientific breakthroughs that drive improved patient outcomes for blood disorders but also about the intersectionality between hematology and other life disciplines.

I remember taking an art class in high school learning about dimensions and proportions of buildings and I dreamt of becoming an architect. Fast forward 2 decades later, I attended a medical conference at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta and was enthralled at how various sessions demonstrated how art, engineering and architecture played a role in the development and design of orthopedic prosthesis used in amputees. I learned how engineering shaped our understanding of microfluidics, something that is now being leveraged in drug delivery science and in the field of hematology.

I want our readers to keep learning not just from esteemed scientists and clinicians but from various stakeholders – the patient, the high school student, the spouse of the hematologist, not to mention our residents and fellows, who are the future of our discipline. Furthermore, I want our readers to see the human side of hematology – the face behind the scientist or clinician and the reality of what joys and tolls we experience in this field.

A Fall 2019 Medscape survey cited the prevalence of physician burnout among hematology oncology physicians: 32% of oncologists were burned out, 4% were depressed, and 9% were both burned out and depressed. These are statistics that cannot be ignored or minimized a they ultimately have a profound impact on patient outcomes. You see, I really believe that much of the success we have in healing our patients relies not just on the medications we prescribe or on the procedures we perform or the science we leverage. Much of healing in medicine and in hematology is based on the secret sauce of being humane – defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as the character trait that is “marked by demonstrating compassion, sympathy, or consideration for humans or animals.”

So, to sum up what to expect in the coming year from your editor in chief? Look out for some thought-provoking, fun, and unusual perspectives that are aimed to keep us learning, growing, and remaining humane in our interactions with our patients, each other, but more importantly with ourselves. #bringit2020 #HematologyNews #NewEditorInChiefPerspectives.

Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, MPH, is a professor of medicine and the director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise at the Levine Cancer Institute, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. She is the editor in chief of Hematology News.

It’s an honor and a great pleasure to take on this new role as editor in chief for Hematology News. When I got the call from our outgoing editor Matt Kalaycio, MD, a year ago asking me to consider stepping into his shoes a few things flashed through my mind. Will I do this role justice? Do I have what it takes to be a great editor in chief?

Then I thought – will there be time to learn the ropes or will this be like most of my career positions where you jump into the water first and figure out how to swim later? I never once thought: “Oh no … I cannot do this and I’m going to say no!” So here I am today, reporting for duty as the editor in chief of Hematology News.

I was once accused of being “intellectually restless” which is a badge I wear with honor and is perhaps a trait I learned from my mom who was a public health nurse in Nigeria back in the seventies. She broke a lot of glass ceilings in her day – Cornell University–trained advanced practice nurse, mother of five girls, with a degree in textile and design and business accounting. She also got a certificate in baking and cake decorating and she used all her skills and certifications to raise her daughters to believe the sky was the limit.

Mom started one of the first licensed practical nursing (LPN) schools in Nigeria and I learned from her to never back down from a challenge – on a dare I got my LPN certification before I went to medical school.

You see I love a challenge and an adventure and serving as the editor in chief for Hematology News provides me with an amazing platform and opportunity to achieve a lot of firsts and satisfy that hunger to make a global difference that has always guided my career.

I’ve thought long and hard about what and how I envision this role shaping out. What do I want our readers to take away from this newspaper under my leadership? What common themes will be woven in every edition? I want our readers to be challenged and keep learning. Not just about hematologic disorders and the latest scientific breakthroughs that drive improved patient outcomes for blood disorders but also about the intersectionality between hematology and other life disciplines.

I remember taking an art class in high school learning about dimensions and proportions of buildings and I dreamt of becoming an architect. Fast forward 2 decades later, I attended a medical conference at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta and was enthralled at how various sessions demonstrated how art, engineering and architecture played a role in the development and design of orthopedic prosthesis used in amputees. I learned how engineering shaped our understanding of microfluidics, something that is now being leveraged in drug delivery science and in the field of hematology.

I want our readers to keep learning not just from esteemed scientists and clinicians but from various stakeholders – the patient, the high school student, the spouse of the hematologist, not to mention our residents and fellows, who are the future of our discipline. Furthermore, I want our readers to see the human side of hematology – the face behind the scientist or clinician and the reality of what joys and tolls we experience in this field.

A Fall 2019 Medscape survey cited the prevalence of physician burnout among hematology oncology physicians: 32% of oncologists were burned out, 4% were depressed, and 9% were both burned out and depressed. These are statistics that cannot be ignored or minimized a they ultimately have a profound impact on patient outcomes. You see, I really believe that much of the success we have in healing our patients relies not just on the medications we prescribe or on the procedures we perform or the science we leverage. Much of healing in medicine and in hematology is based on the secret sauce of being humane – defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as the character trait that is “marked by demonstrating compassion, sympathy, or consideration for humans or animals.”

So, to sum up what to expect in the coming year from your editor in chief? Look out for some thought-provoking, fun, and unusual perspectives that are aimed to keep us learning, growing, and remaining humane in our interactions with our patients, each other, but more importantly with ourselves. #bringit2020 #HematologyNews #NewEditorInChiefPerspectives.

Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, MPH, is a professor of medicine and the director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise at the Levine Cancer Institute, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. She is the editor in chief of Hematology News.

It’s an honor and a great pleasure to take on this new role as editor in chief for Hematology News. When I got the call from our outgoing editor Matt Kalaycio, MD, a year ago asking me to consider stepping into his shoes a few things flashed through my mind. Will I do this role justice? Do I have what it takes to be a great editor in chief?

Then I thought – will there be time to learn the ropes or will this be like most of my career positions where you jump into the water first and figure out how to swim later? I never once thought: “Oh no … I cannot do this and I’m going to say no!” So here I am today, reporting for duty as the editor in chief of Hematology News.

I was once accused of being “intellectually restless” which is a badge I wear with honor and is perhaps a trait I learned from my mom who was a public health nurse in Nigeria back in the seventies. She broke a lot of glass ceilings in her day – Cornell University–trained advanced practice nurse, mother of five girls, with a degree in textile and design and business accounting. She also got a certificate in baking and cake decorating and she used all her skills and certifications to raise her daughters to believe the sky was the limit.

Mom started one of the first licensed practical nursing (LPN) schools in Nigeria and I learned from her to never back down from a challenge – on a dare I got my LPN certification before I went to medical school.

You see I love a challenge and an adventure and serving as the editor in chief for Hematology News provides me with an amazing platform and opportunity to achieve a lot of firsts and satisfy that hunger to make a global difference that has always guided my career.

I’ve thought long and hard about what and how I envision this role shaping out. What do I want our readers to take away from this newspaper under my leadership? What common themes will be woven in every edition? I want our readers to be challenged and keep learning. Not just about hematologic disorders and the latest scientific breakthroughs that drive improved patient outcomes for blood disorders but also about the intersectionality between hematology and other life disciplines.

I remember taking an art class in high school learning about dimensions and proportions of buildings and I dreamt of becoming an architect. Fast forward 2 decades later, I attended a medical conference at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta and was enthralled at how various sessions demonstrated how art, engineering and architecture played a role in the development and design of orthopedic prosthesis used in amputees. I learned how engineering shaped our understanding of microfluidics, something that is now being leveraged in drug delivery science and in the field of hematology.

I want our readers to keep learning not just from esteemed scientists and clinicians but from various stakeholders – the patient, the high school student, the spouse of the hematologist, not to mention our residents and fellows, who are the future of our discipline. Furthermore, I want our readers to see the human side of hematology – the face behind the scientist or clinician and the reality of what joys and tolls we experience in this field.

A Fall 2019 Medscape survey cited the prevalence of physician burnout among hematology oncology physicians: 32% of oncologists were burned out, 4% were depressed, and 9% were both burned out and depressed. These are statistics that cannot be ignored or minimized a they ultimately have a profound impact on patient outcomes. You see, I really believe that much of the success we have in healing our patients relies not just on the medications we prescribe or on the procedures we perform or the science we leverage. Much of healing in medicine and in hematology is based on the secret sauce of being humane – defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as the character trait that is “marked by demonstrating compassion, sympathy, or consideration for humans or animals.”

So, to sum up what to expect in the coming year from your editor in chief? Look out for some thought-provoking, fun, and unusual perspectives that are aimed to keep us learning, growing, and remaining humane in our interactions with our patients, each other, but more importantly with ourselves. #bringit2020 #HematologyNews #NewEditorInChiefPerspectives.

Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, MPH, is a professor of medicine and the director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise at the Levine Cancer Institute, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. She is the editor in chief of Hematology News.

Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for menopausal hot flashes

The field of menopause medicine is dominated by studies documenting the effectiveness of systemic estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes caused by hypoestrogenism. The effectiveness of progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes is much less studied and seldom is utilized in clinical practice. A small number of studies have reported that progestins, including micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethindrone acetate, are effective treatment for hot flashes. Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment.

Micronized progesterone

Micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 300 mg daily taken at bedtime has been reported to effectively treat hot flashes in postmenopausal women. In one study, 133 postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years and approximately 3 years from their last menstrual period were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo or micronized progesterone 300 mg daily taken at bedtime.1 Mean serum progesterone levels were 0.28 ng/mL (0.89 nM) and 27 ng/mL (86 nM) in the women taking placebo and micronized progesterone, respectively. Compared with placebo, micronized progesterone reduced daytime and nighttime hot flash frequency and severity. In addition, compared with placebo, micronized progesterone improved the quality of sleep.1

Most reviews conclude that micronized progesterone has minimal cardiovascular risk.2 Micronized progesterone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment such as those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or women with a thrombophilia. Many experts believe that systemic estrogen therapy is contraindicated in postmenopausal women with an American Heart Association risk score greater than 10% over 10 years.3 Additional contraindications to systemic estrogen include women with cardiac disease who have a thrombophilia, such as the Factor V Leiden mutation.4

For women who are at high risk for estrogen-induced cardiovascular events, micronized progesterone may be a better option than systemic estrogen for treating hot flashes. Alternatively, in these women at risk of cardiovascular disease a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, such as escitalopram, 10 mg to 20 mg daily, may be a good option for treating postmenopausal hot flashes.5

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, at a dosage of 20 mg daily, is an effective treatment for hot flashes. In a randomized clinical trial 27 postmenopausal women with hot flashes were randomly assigned to treatment with placebo or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily for 4 weeks. Vasomotor flushes were decreased by 26% and 74% in the placebo and medroxyprogesterone groups, respectively.6

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at dosages from 150 mg to 400 mg also have been reported to effectively treat hot flashes.7,8 In a trial comparing the effectiveness of estrogen monotherapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.6 mg daily) with progestin monotherapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily), both treatments were equally effective in reducing hot flashes.9

Continue to: Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate...

Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate

Experts in menopause medicine have suggested that in postmenopausal women micronized progesterone has a better pattern of benefits and fewer risks than medroxyprogesterone acetate.10,11 For example, in the E3N observational study of hormones and breast cancer risk, among 80,377 French postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8 years, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone was associated with no significantly increased risk of breast cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.31) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy.12 By contrast, the combination of oral estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.02–2.16) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. The E3N study indicates that micronized progesterone may have a more favorable breast health profile than medroxyprogesterone acetate.12

Norethindrone acetate

Norethindrone acetate monotherapy is not commonly prescribed for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. However, a large clinical trial has demonstrated that norethindrone acetate effectively suppresses hot flashes in women with endometriosis treated with depot leuprolide acetate (LA). In one trial 201 women with endometriosis were randomly assigned to 12 months of treatment with13:

- LA plus placebo pills

- LA plus norethindrone acetate (NEA) 5 mg daily

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily, or

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus CEE 1.25 mg daily.

The median number of hot flashes in 24 hours was 6 in the LA plus placebo group and 0 in both the LA plus NEA 5 mg daily group and the LA plus NEA 5 mg plus CEE 1.25 mg daily group. This study demonstrates that NEA 5 mg daily is an effective treatment for hot flashes.

In the same study, LA plus placebo was associated with a significant decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density. No significant decrease in bone mineral density was observed in the women who received LA plus NEA 5 mg daily. This finding indicates that NEA 5 mg reduces bone absorption caused by hypoestrogenism. In humans, norethindrone is a substrate for the aromatase enzyme system.14 Small quantities of ethinyl estradiol may be formed by aromatization of norethindrone in vivo,15,16 contributing to the effectiveness of NEA in suppressing hot flashes and preserving bone density.

Progestin: The estrogen alternative to hot flashes

For postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, estrogen treatment reliably suppresses hot flashes and often improves sleep quality and mood. For postmenopausal women with a contraindication to estrogen treatment, progestin-only treatment with micronized progesterone or norethindrone acetate may be an effective option.

- Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral micronized progesterone for vasomotor symptoms—a placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:886-893.

- Spark MJ, Willis J. Systematic review of progesterone use by midlife menopausal women. Maturitas 2012; 72: 192-202.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/nonhormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-suport tool from The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:247-253.

- Herrington DM, Vittinghoff E, Howard TD, et al. Factor V Leiden, hormone replacement therapy, and risk of venous thromboembolic events in women with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1012-1017.

- Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848-855.

- Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA. 1980;244:1443-1445.

- Bullock JL, Massey FM, Gambrell RD Jr. Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:165-168.

- Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, et al. Phase III comparison of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1409-1414.

- Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112:517-525.

- L’hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, et al. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas. 2008;60:185-201.

- Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? Menopause. 2014;21:769-783.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:103-111.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Barbieri RL, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. High-affinity steroid binding to rat testis 17 alpha-hydroxylase and human placental aromatase. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:387-393.

- Chu MC, Zhang X, Gentzschein E, et al. Formation of ethinyl estradiol in women during treatment with norethindrone acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2205-2207.

- Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:563-571.

The field of menopause medicine is dominated by studies documenting the effectiveness of systemic estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes caused by hypoestrogenism. The effectiveness of progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes is much less studied and seldom is utilized in clinical practice. A small number of studies have reported that progestins, including micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethindrone acetate, are effective treatment for hot flashes. Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment.

Micronized progesterone

Micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 300 mg daily taken at bedtime has been reported to effectively treat hot flashes in postmenopausal women. In one study, 133 postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years and approximately 3 years from their last menstrual period were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo or micronized progesterone 300 mg daily taken at bedtime.1 Mean serum progesterone levels were 0.28 ng/mL (0.89 nM) and 27 ng/mL (86 nM) in the women taking placebo and micronized progesterone, respectively. Compared with placebo, micronized progesterone reduced daytime and nighttime hot flash frequency and severity. In addition, compared with placebo, micronized progesterone improved the quality of sleep.1

Most reviews conclude that micronized progesterone has minimal cardiovascular risk.2 Micronized progesterone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment such as those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or women with a thrombophilia. Many experts believe that systemic estrogen therapy is contraindicated in postmenopausal women with an American Heart Association risk score greater than 10% over 10 years.3 Additional contraindications to systemic estrogen include women with cardiac disease who have a thrombophilia, such as the Factor V Leiden mutation.4

For women who are at high risk for estrogen-induced cardiovascular events, micronized progesterone may be a better option than systemic estrogen for treating hot flashes. Alternatively, in these women at risk of cardiovascular disease a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, such as escitalopram, 10 mg to 20 mg daily, may be a good option for treating postmenopausal hot flashes.5

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, at a dosage of 20 mg daily, is an effective treatment for hot flashes. In a randomized clinical trial 27 postmenopausal women with hot flashes were randomly assigned to treatment with placebo or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily for 4 weeks. Vasomotor flushes were decreased by 26% and 74% in the placebo and medroxyprogesterone groups, respectively.6

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at dosages from 150 mg to 400 mg also have been reported to effectively treat hot flashes.7,8 In a trial comparing the effectiveness of estrogen monotherapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.6 mg daily) with progestin monotherapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily), both treatments were equally effective in reducing hot flashes.9

Continue to: Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate...

Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate

Experts in menopause medicine have suggested that in postmenopausal women micronized progesterone has a better pattern of benefits and fewer risks than medroxyprogesterone acetate.10,11 For example, in the E3N observational study of hormones and breast cancer risk, among 80,377 French postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8 years, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone was associated with no significantly increased risk of breast cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.31) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy.12 By contrast, the combination of oral estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.02–2.16) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. The E3N study indicates that micronized progesterone may have a more favorable breast health profile than medroxyprogesterone acetate.12

Norethindrone acetate

Norethindrone acetate monotherapy is not commonly prescribed for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. However, a large clinical trial has demonstrated that norethindrone acetate effectively suppresses hot flashes in women with endometriosis treated with depot leuprolide acetate (LA). In one trial 201 women with endometriosis were randomly assigned to 12 months of treatment with13:

- LA plus placebo pills

- LA plus norethindrone acetate (NEA) 5 mg daily

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily, or

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus CEE 1.25 mg daily.

The median number of hot flashes in 24 hours was 6 in the LA plus placebo group and 0 in both the LA plus NEA 5 mg daily group and the LA plus NEA 5 mg plus CEE 1.25 mg daily group. This study demonstrates that NEA 5 mg daily is an effective treatment for hot flashes.

In the same study, LA plus placebo was associated with a significant decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density. No significant decrease in bone mineral density was observed in the women who received LA plus NEA 5 mg daily. This finding indicates that NEA 5 mg reduces bone absorption caused by hypoestrogenism. In humans, norethindrone is a substrate for the aromatase enzyme system.14 Small quantities of ethinyl estradiol may be formed by aromatization of norethindrone in vivo,15,16 contributing to the effectiveness of NEA in suppressing hot flashes and preserving bone density.

Progestin: The estrogen alternative to hot flashes

For postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, estrogen treatment reliably suppresses hot flashes and often improves sleep quality and mood. For postmenopausal women with a contraindication to estrogen treatment, progestin-only treatment with micronized progesterone or norethindrone acetate may be an effective option.

The field of menopause medicine is dominated by studies documenting the effectiveness of systemic estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes caused by hypoestrogenism. The effectiveness of progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes is much less studied and seldom is utilized in clinical practice. A small number of studies have reported that progestins, including micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethindrone acetate, are effective treatment for hot flashes. Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment.

Micronized progesterone

Micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 300 mg daily taken at bedtime has been reported to effectively treat hot flashes in postmenopausal women. In one study, 133 postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years and approximately 3 years from their last menstrual period were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo or micronized progesterone 300 mg daily taken at bedtime.1 Mean serum progesterone levels were 0.28 ng/mL (0.89 nM) and 27 ng/mL (86 nM) in the women taking placebo and micronized progesterone, respectively. Compared with placebo, micronized progesterone reduced daytime and nighttime hot flash frequency and severity. In addition, compared with placebo, micronized progesterone improved the quality of sleep.1

Most reviews conclude that micronized progesterone has minimal cardiovascular risk.2 Micronized progesterone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment such as those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or women with a thrombophilia. Many experts believe that systemic estrogen therapy is contraindicated in postmenopausal women with an American Heart Association risk score greater than 10% over 10 years.3 Additional contraindications to systemic estrogen include women with cardiac disease who have a thrombophilia, such as the Factor V Leiden mutation.4

For women who are at high risk for estrogen-induced cardiovascular events, micronized progesterone may be a better option than systemic estrogen for treating hot flashes. Alternatively, in these women at risk of cardiovascular disease a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, such as escitalopram, 10 mg to 20 mg daily, may be a good option for treating postmenopausal hot flashes.5

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, at a dosage of 20 mg daily, is an effective treatment for hot flashes. In a randomized clinical trial 27 postmenopausal women with hot flashes were randomly assigned to treatment with placebo or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily for 4 weeks. Vasomotor flushes were decreased by 26% and 74% in the placebo and medroxyprogesterone groups, respectively.6

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at dosages from 150 mg to 400 mg also have been reported to effectively treat hot flashes.7,8 In a trial comparing the effectiveness of estrogen monotherapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.6 mg daily) with progestin monotherapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily), both treatments were equally effective in reducing hot flashes.9

Continue to: Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate...

Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate

Experts in menopause medicine have suggested that in postmenopausal women micronized progesterone has a better pattern of benefits and fewer risks than medroxyprogesterone acetate.10,11 For example, in the E3N observational study of hormones and breast cancer risk, among 80,377 French postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8 years, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone was associated with no significantly increased risk of breast cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.31) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy.12 By contrast, the combination of oral estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.02–2.16) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. The E3N study indicates that micronized progesterone may have a more favorable breast health profile than medroxyprogesterone acetate.12

Norethindrone acetate

Norethindrone acetate monotherapy is not commonly prescribed for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. However, a large clinical trial has demonstrated that norethindrone acetate effectively suppresses hot flashes in women with endometriosis treated with depot leuprolide acetate (LA). In one trial 201 women with endometriosis were randomly assigned to 12 months of treatment with13:

- LA plus placebo pills

- LA plus norethindrone acetate (NEA) 5 mg daily

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily, or

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus CEE 1.25 mg daily.

The median number of hot flashes in 24 hours was 6 in the LA plus placebo group and 0 in both the LA plus NEA 5 mg daily group and the LA plus NEA 5 mg plus CEE 1.25 mg daily group. This study demonstrates that NEA 5 mg daily is an effective treatment for hot flashes.

In the same study, LA plus placebo was associated with a significant decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density. No significant decrease in bone mineral density was observed in the women who received LA plus NEA 5 mg daily. This finding indicates that NEA 5 mg reduces bone absorption caused by hypoestrogenism. In humans, norethindrone is a substrate for the aromatase enzyme system.14 Small quantities of ethinyl estradiol may be formed by aromatization of norethindrone in vivo,15,16 contributing to the effectiveness of NEA in suppressing hot flashes and preserving bone density.

Progestin: The estrogen alternative to hot flashes

For postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, estrogen treatment reliably suppresses hot flashes and often improves sleep quality and mood. For postmenopausal women with a contraindication to estrogen treatment, progestin-only treatment with micronized progesterone or norethindrone acetate may be an effective option.

- Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral micronized progesterone for vasomotor symptoms—a placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:886-893.

- Spark MJ, Willis J. Systematic review of progesterone use by midlife menopausal women. Maturitas 2012; 72: 192-202.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/nonhormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-suport tool from The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:247-253.

- Herrington DM, Vittinghoff E, Howard TD, et al. Factor V Leiden, hormone replacement therapy, and risk of venous thromboembolic events in women with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1012-1017.

- Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848-855.

- Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA. 1980;244:1443-1445.

- Bullock JL, Massey FM, Gambrell RD Jr. Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:165-168.

- Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, et al. Phase III comparison of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1409-1414.

- Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112:517-525.

- L’hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, et al. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas. 2008;60:185-201.

- Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? Menopause. 2014;21:769-783.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:103-111.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Barbieri RL, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. High-affinity steroid binding to rat testis 17 alpha-hydroxylase and human placental aromatase. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:387-393.

- Chu MC, Zhang X, Gentzschein E, et al. Formation of ethinyl estradiol in women during treatment with norethindrone acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2205-2207.

- Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:563-571.

- Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral micronized progesterone for vasomotor symptoms—a placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:886-893.

- Spark MJ, Willis J. Systematic review of progesterone use by midlife menopausal women. Maturitas 2012; 72: 192-202.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/nonhormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-suport tool from The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:247-253.

- Herrington DM, Vittinghoff E, Howard TD, et al. Factor V Leiden, hormone replacement therapy, and risk of venous thromboembolic events in women with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1012-1017.

- Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848-855.

- Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA. 1980;244:1443-1445.

- Bullock JL, Massey FM, Gambrell RD Jr. Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:165-168.

- Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, et al. Phase III comparison of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1409-1414.

- Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112:517-525.

- L’hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, et al. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas. 2008;60:185-201.

- Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? Menopause. 2014;21:769-783.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:103-111.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Barbieri RL, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. High-affinity steroid binding to rat testis 17 alpha-hydroxylase and human placental aromatase. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:387-393.

- Chu MC, Zhang X, Gentzschein E, et al. Formation of ethinyl estradiol in women during treatment with norethindrone acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2205-2207.

- Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:563-571.

We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients!

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

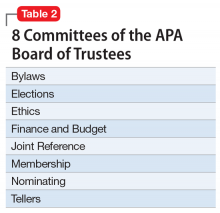

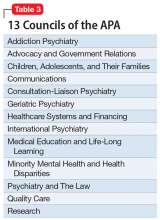

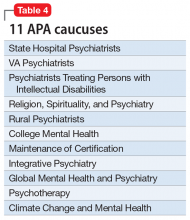

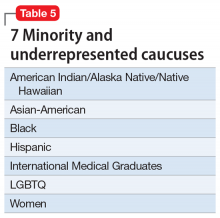

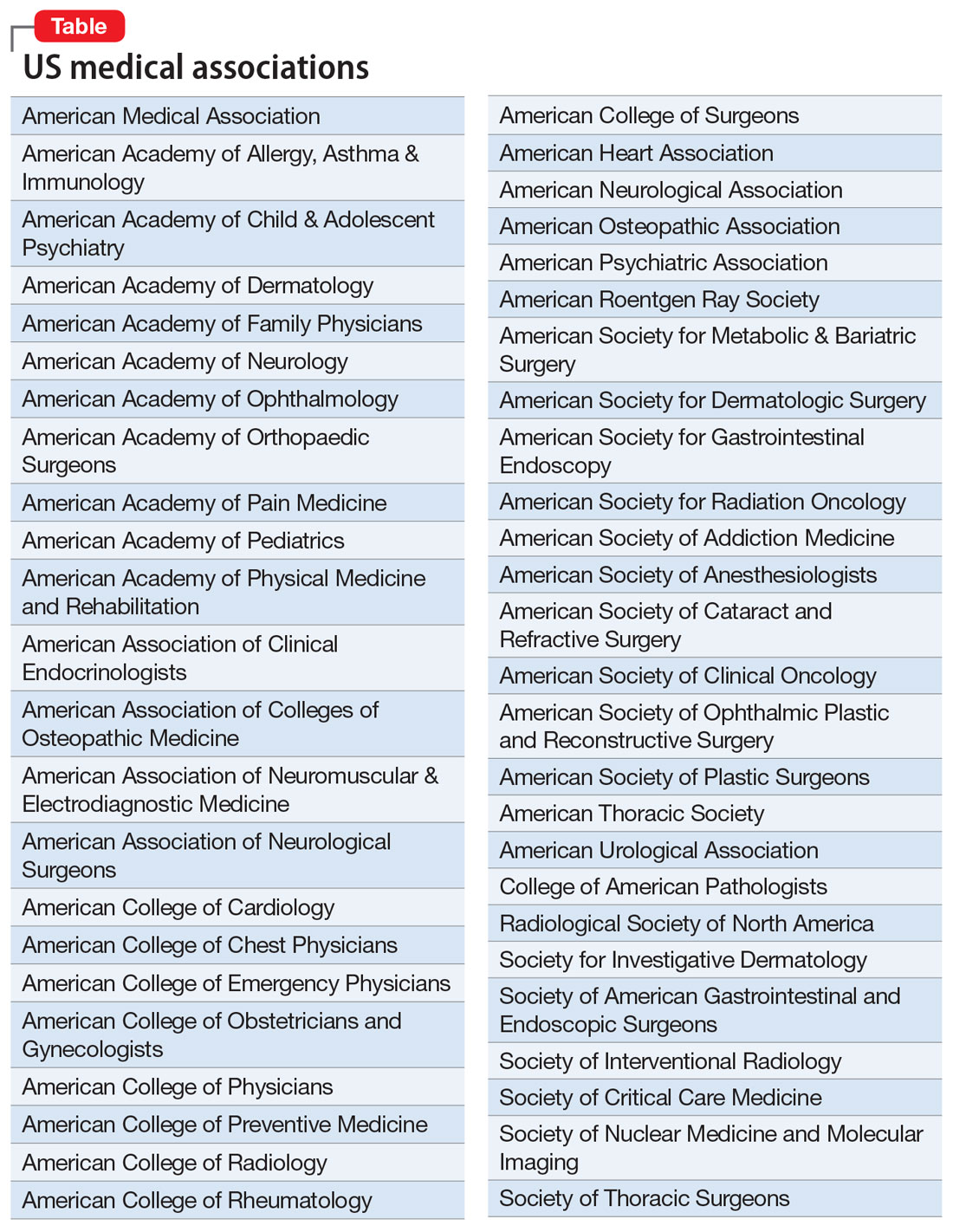

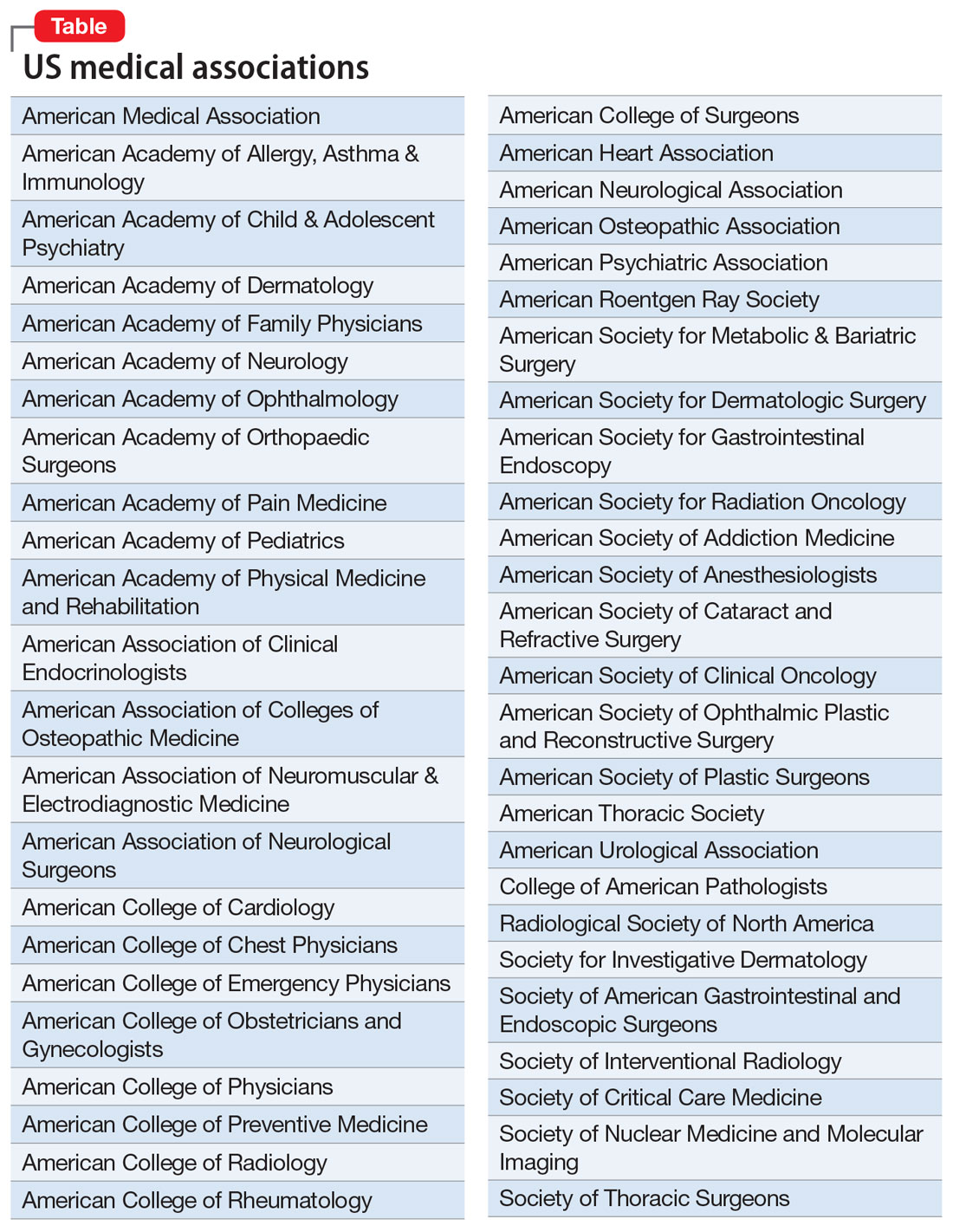

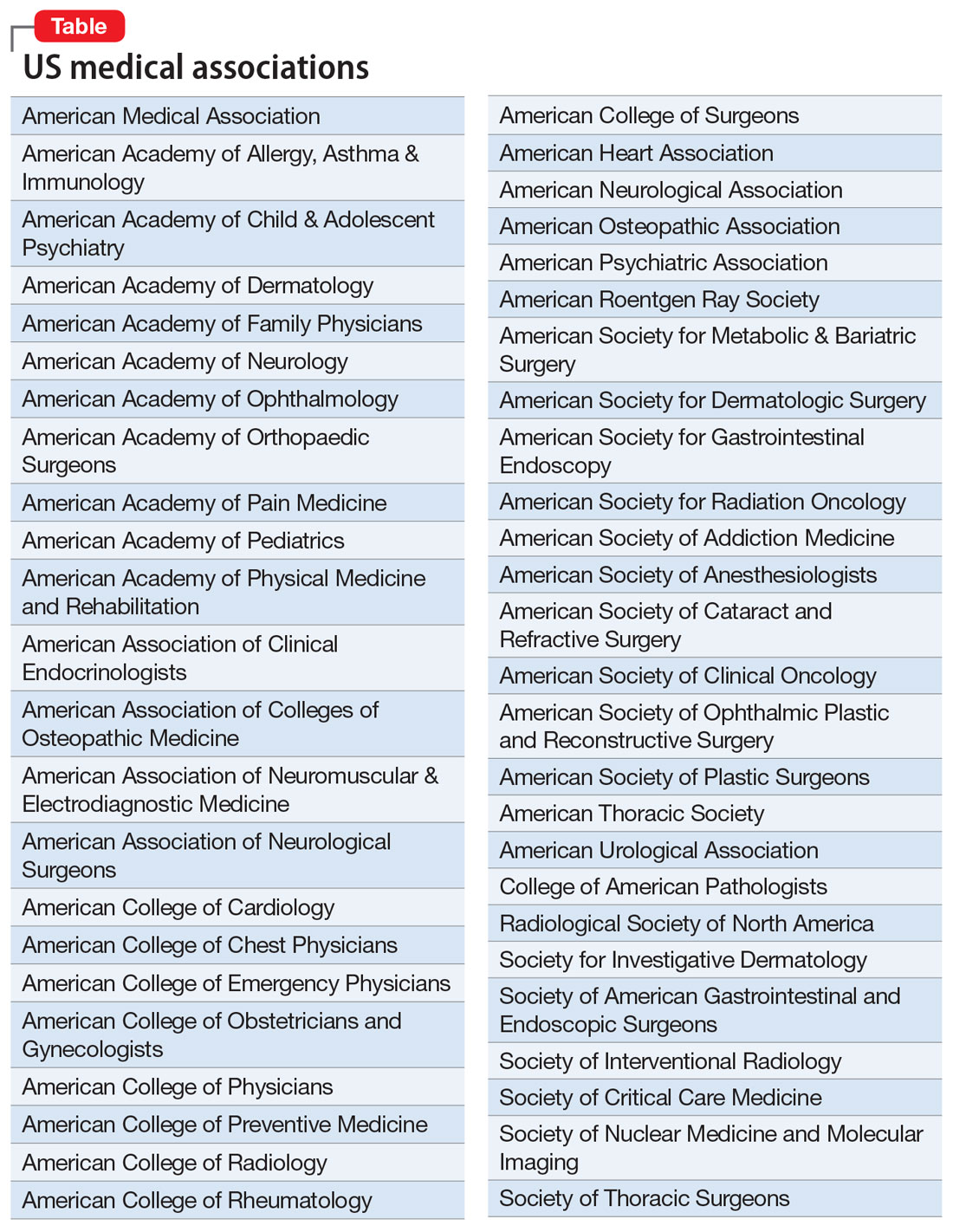

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

What is optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

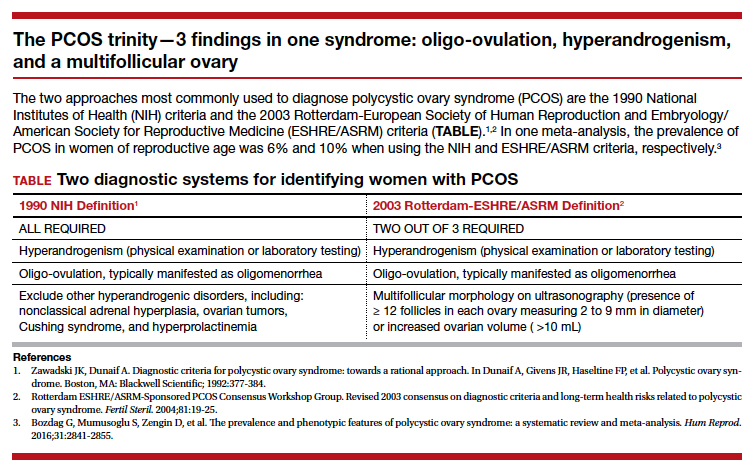

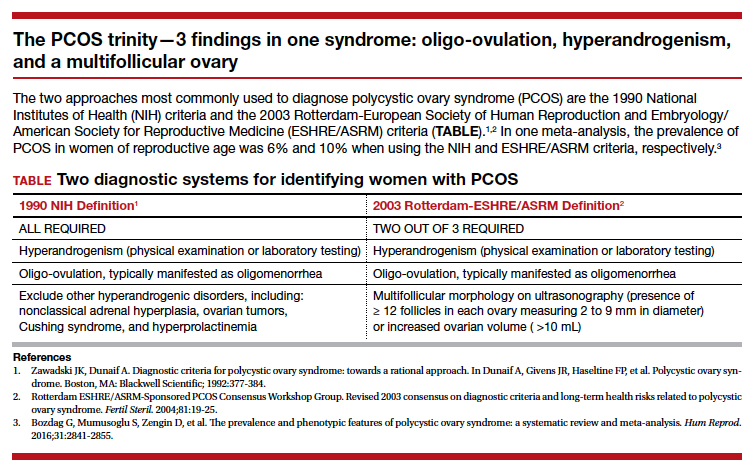

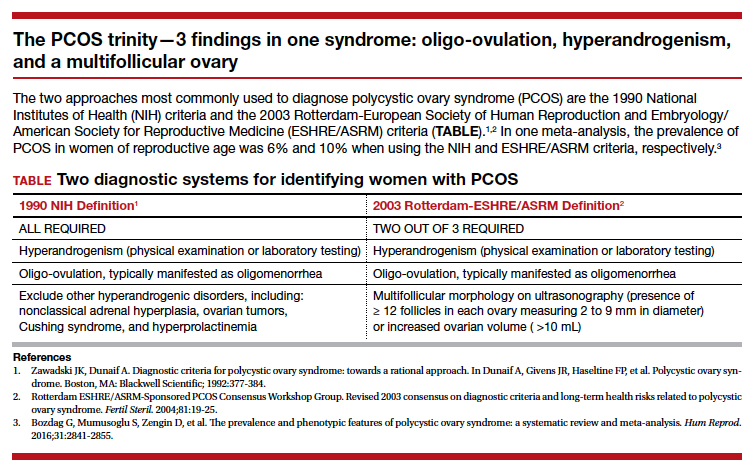

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the triad of oligo-ovulation resulting in oligomenorrhea, hyperandrogenism and, often, an excess number of small antral follicles on high-resolution pelvic ultrasound. One meta-analysis reported that, in women of reproductive age, the prevalence of PCOS was 10% using the Rotterdam-European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ESHRE/ASRM) criteria1 and 6% using the National Institutes of Health 1990 diagnostic criteria.2 (See “The PCOS trinity—3 findings in one syndrome: oligo-ovulation, hyperandrogenism, and a multifollicular ovary.”3)

PCOS is caused by abnormalities in 3 systems: reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic. Reproductive abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include4:

- an increase in pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), resulting from both an increase in LH pulse amplitude and LH pulse frequency, suggesting a primary hypothalamic disorder

- an increase in ovarian secretion of androstenedione and testosterone due to stimulation by LH and possibly insulin

- oligo-ovulation with chronically low levels of progesterone that can result in endometrial hyperplasia

- ovulatory infertility.

Metabolic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include5,6:

- insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia

- excess adipose tissue in the liver

- excess visceral fat

- elevated adipokines

- obesity

- an increased prevalence of glucose intolerance and frank diabetes.

Dermatologic abnormalities commonly observed in women with PCOS include7:

- facial hirsutism

- acne

- androgenetic alopecia.

Given that PCOS is caused by abnormalities in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic systems, it is appropriate to consider multimodal hormonal therapy that addresses all 3 problems. In my practice, I believe that the best approach to the long-term hormonal treatment of PCOS for many women is to prescribe a combination of 3 medicines: a combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptive (COC), an insulin sensitizer, and an antiandrogen.

The COC reduces pituitary secretion of LH, decreases ovarian androgen production, and prevents the development of endometrial hyperplasia. When taken cyclically, the COC treatment also restores regular withdrawal uterine bleeding.

An insulin sensitizer, such as metformin or pioglitazone, helps to reduce insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and hepatic adipose content, rebalancing central metabolism. It is important to include diet and exercise in the long-term treatment of PCOS, and I always encourage these lifestyle changes. However, my patients usually report that they have tried multiple times to restrict dietary caloric intake and increase exercise and have been unable to rebalance their metabolism with these interventions alone. Of note, in the women with PCOS and a body mass index >35 kg/m2, bariatric surgery, such as a sleeve gastrectomy, often results in marked improvement of their PCOS.8

The antiandrogen spironolactone provides effective treatment for the dermatologic problems of facial hirsutism and acne. Some COCs containing the progestins drospirenone, norgestimate, and norethindrone acetate are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of acne. A common approach I use in practice is to prescribe a COC, plus spironolactone 100 mg daily plus metformin extended-release 750 mg to 1,500 mg daily.

Continue to: Which COCs have low androgenicity?...

Which COCs have low androgenicity?

I believe that every COC is an effective treatment for PCOS, regardless of the androgenicity of the progestin in the contraceptive. However, some dermatologists believe that combination contraceptives containing progestins with low androgenicity, such as drospirenone, norgestimate, and desogestrel, are more likely to improve acne than contraceptives with an androgenic progestin such as levonorgestrel. In one study in which 2,147 women with acne were treated by one dermatologic practice, the percentage of women reporting that a birth control pill helped to improve their acne was 66% for pills containing drospirenone, 53% for pills containing norgestimate, 44% for pills containing desogestrel, 30% for pills containing norethindrone, and 25% for pills containing levonorgestrel. In the same study, the percent of women reporting that a birth control pill made their acne worse was 3% for pills containing drospirenone, 6% for pills containing norgestimate, 2% for pills containing desogestrel, 8% for pills containing norethindrone, and 10% for pills containing levonorgestrel.9 Given these findings, when treating a woman with PCOS, I generally prescribe a contraceptive that does not contain levonorgestrel.

Why is a spironolactone dose of 100 mg a good choice for PCOS treatment?

Spironolactone, an antiandrogen and inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase, is commonly prescribed for the treatment of hirsutism and acne at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily.10,11 In my clinical experience, spironolactone at a dose of 200 mg daily commonly causes irregular and bothersome uterine bleeding while spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg daily is seldom associated with irregular bleeding. I believe that spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg daily results in superior clinical efficacy than a 50-mg daily dose, although studies report that both doses are effective in the treatment of acne and hirsutism. Spironolactone should not be prescribed to women with renal failure because it can result in severe hyperkalemia. In a study of spironolactone safety in the treatment of acne, no adverse effects on the kidney, liver, or adrenal glands were reported over 8 years of use.12

What insulin sensitizers are useful in rebalancing the metabolic abnormalities observed with PCOS?

Diet and exercise are superb approaches to rebalancing metabolic abnormalities, but for many of my patients they are insufficient and treatment with an insulin sensitizer is warranted. The most commonly utilized insulin sensitizer for the treatment of PCOS is metformin because it is very inexpensive and has a low risk of serious adverse effects such as lactic acidosis. Metformin increases peripheral glucose uptake and reduces gastrointestinal glucose absorption. Insulin sensitizers also decrease visceral fat, a major source of adipokines. One major disadvantage of metformin is that at doses in the range of 1,500 mg to 2,250 mg it often causes gastrointestinal adverse effects such as borborygmi, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and loose stools.

Thiazolidinediones, including pioglitazone, have been reported to be effective in rebalancing central metabolism in women with PCOS. Pioglitazone carries a black box warning of an increased risk of congestive heart failure and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Pioglitazone is also associated with a risk of hepatotoxicity. However, at the pioglitazone dose commonly used in the treatment of PCOS (7.5 mg daily), these serious adverse effects are rare. In practice, I initiate metformin at a dose of 750 mg daily using the extended-release formulation. I increase the metformin dose to 1,500 mg daily if the patient has no bothersome gastrointestinal symptoms on the lower dose. If the patient cannot tolerate metformin treatment because of adverse effects, I will use pioglitazone 7.5 mg daily.

Continue to: Treatment of PCOS in women who are carriers of the Factor V Leiden mutation...

Treatment of PCOS in women who are carriers of the Factor V Leiden mutation

The Factor V Leiden allele is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Estrogen-progestin contraception is contraindicated in women with the Factor V Leiden mutation. The prevalence of this mutation varies by race and ethnicity. It is present in about 5% of white, 2% of Hispanic, 1% of black, 1% of Native American, and 0.5% of Asian women. In women with PCOS who are known to be carriers of the mutation, dual therapy with metformin and spironolactone is highly effective.13-15 For these women I also offer a levonorgestrel IUD to provide contraception and reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia.

Combination triple medication treatment of PCOS

Optimal treatment of the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic problems associated with PCOS requires multimodal medications including an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, an antiandrogen, and an insulin sensitizer. In my practice, I initiate treatment of PCOS by offering patients 3 medications: a COC, spironolactone 100 mg daily, and metformin extended-release formulation 750 mg daily. Some patients elect dual medication therapy (COC plus spironolactone or COC plus metformin), but many patients select treatment with all 3 medications. Although triple medication treatment of PCOS has not been tested in large randomized clinical trials, small trials report that triple medication treatment produces optimal improvement in the reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic problems associated with PCOS.16-18

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:19-25.

- Zawadski JK, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine FP, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Boston, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:377-384.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, et al. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2841-2855.

- Baskind NE, Balen AH. Hypothalamic-pituitary, ovarian and adrenal contributions to polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;37:80-97.

- Gilbert EW, Tay CT, Hiam DS, et al. Comorbidities and complications of polycystic ovary syndrome: an overview of systematic reviews. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;89:683-699.

- Harsha Varma S, Tirupati S, Pradeep TV, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperandrogenemia independently predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:1065-1069.

- Housman E, Reynolds RV. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: Part I. Diagnosis and manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:847.e1-e10.

- Dilday J, Derickson M, Kuckelman J, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy for obesity in polycystic ovarian syndrome: a pilot study evaluating weight loss and fertility outcomes. Obes Surg. 2019;29:93-98.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:670-674.