User login

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

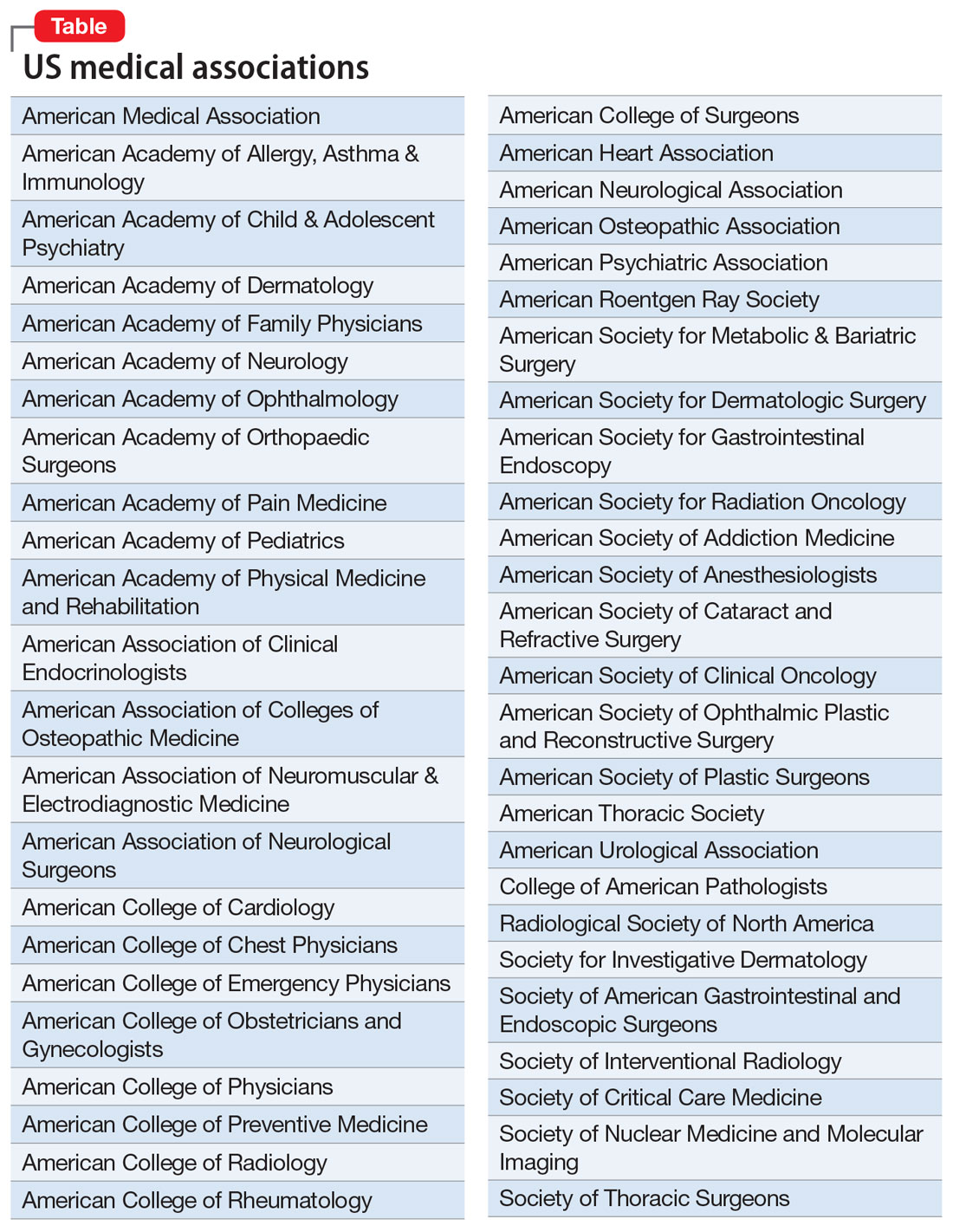

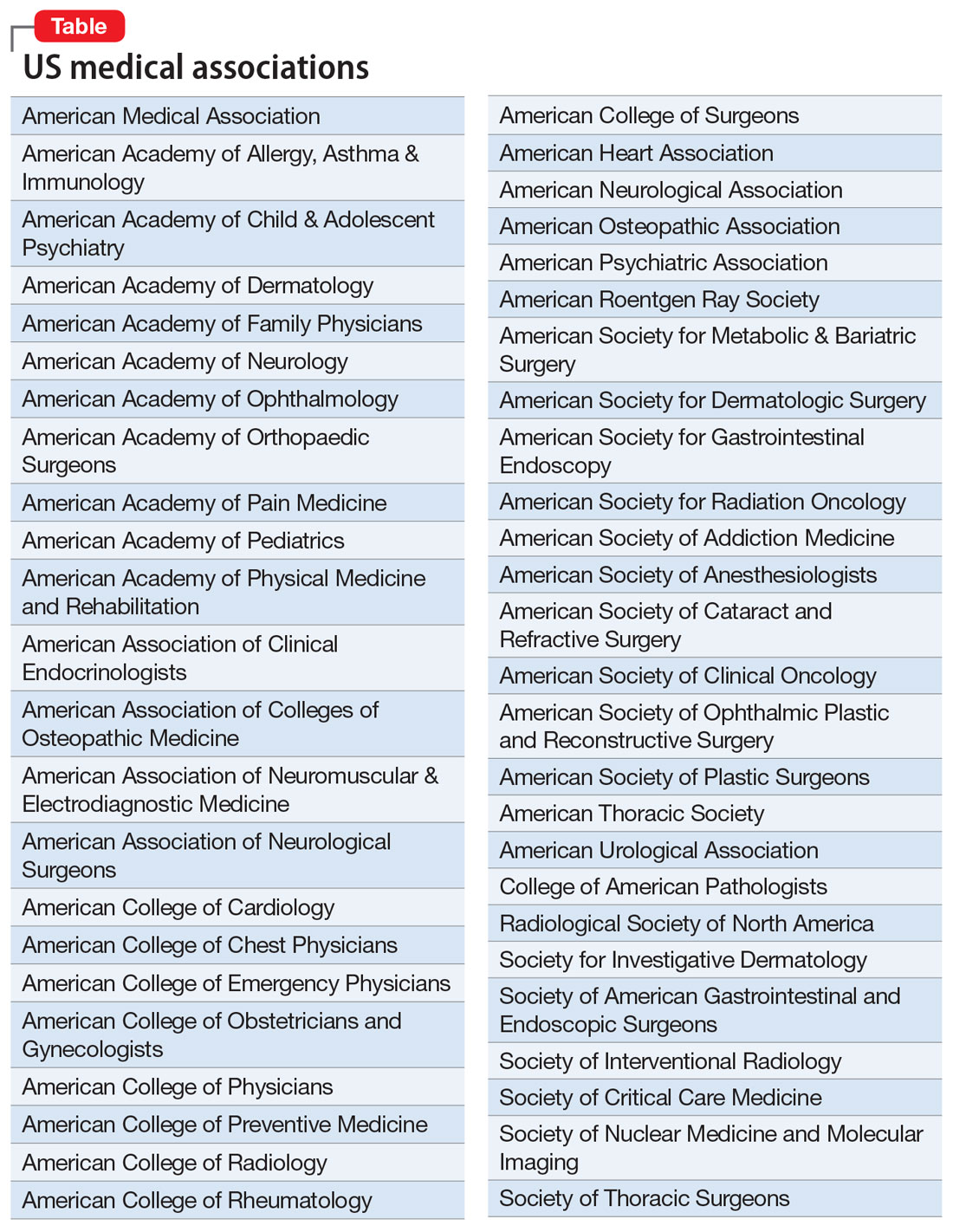

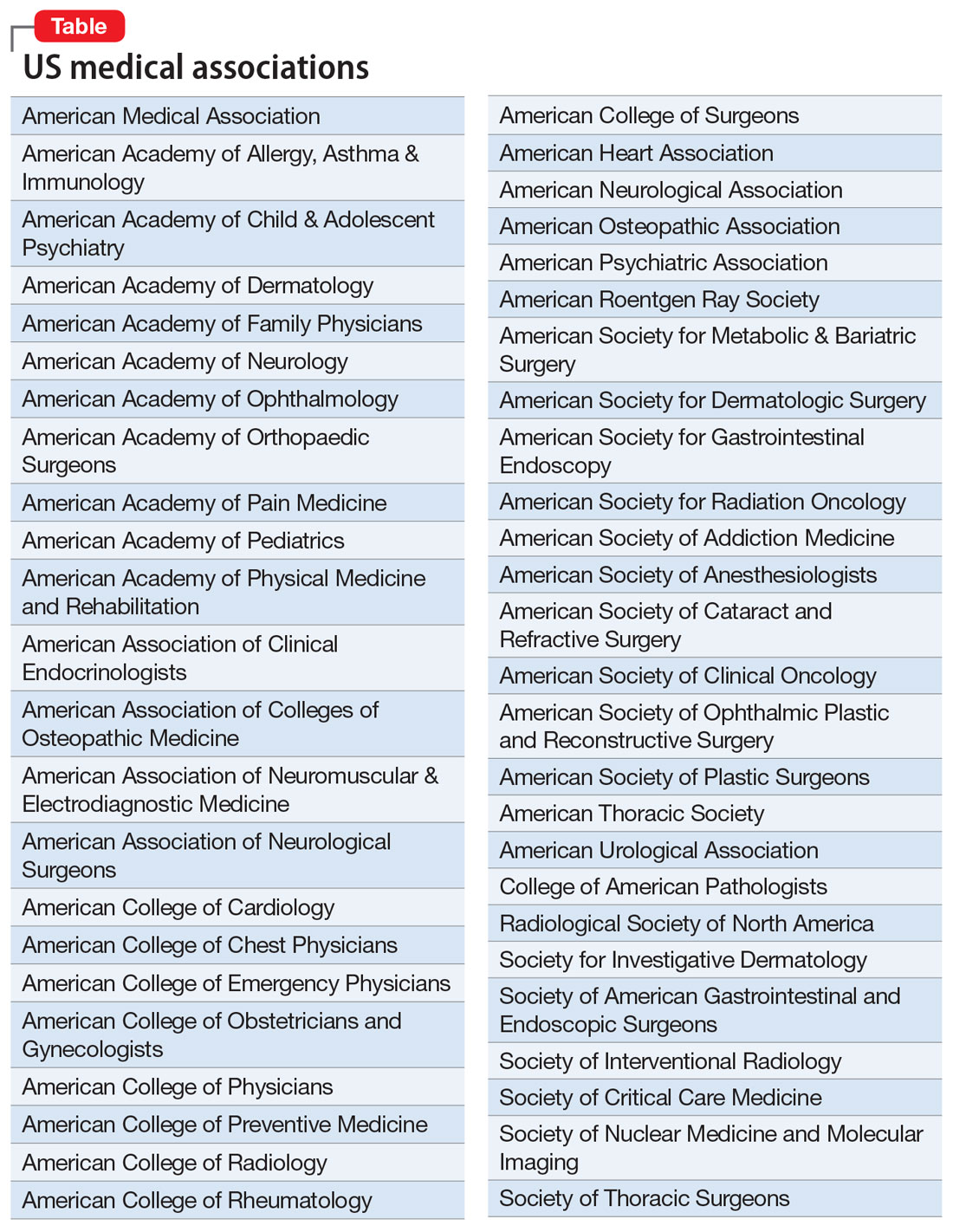

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

One of the most malignant threats that is adversely impacting physicians is the insidious metastasis of the term “provider” within the national health care system over the past 2 to 3 decades.

This demeaning adjective is outrageously inappropriate and beneath the stature of medical doctors (MDs) who sacrificed 12 to 15 years of their lives in college, medical schools, residency programs, and post-residency fellowships to become physicians, specialists, and subspecialists. It is distressing to see hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, insurance corporations, and managed care companies refer to psychiatrists and other physicians as “providers.” It is time to fight back and restore our noble medical identity, which society has always respected and appreciated.

Our unique professional identify is at stake. We do not want to be lumped with nonphysicians as if we are interchangeable parts of a health care system or cogs in a wheel. No other mental health professional has the extensive training, scientific knowledge, clinical expertise, research accomplishments, and teaching/supervisory abilities that physicians have. We strongly uphold the sacred tenet of the physician-patient relationship, and adamantly reject its corruption into a provider-consumer transaction.

Even plumbers and electricians are not referred to as “providers.” Lawyers are not called legal aid providers. Teachers are not called knowledge providers, and administrators and CEOs are not called management providers. So why should physicians in any specialty, including psychiatry, obsequiously accept the denigration of their esteemed medical identify into the vague, amorphous ipseity of a “provider”? Family physicians, internists, and pediatricians used to be called primary care physicians, but have been reduced to primary care providers, which is insulting and degrading to these highly trained MD specialists.

The corruption and debasement of the professional identify of physicians and the propagation of the usage of the belittling term “provider” can be traced back to 3 entities:

1. The Nazi Third Reich. This is the most evil origin of the term “provider,” inflicted on Jewish physicians as part of the despicable persecution of German Jews in the 1930s. The Nazis decided to deprive pediatricians of being called physicians (“Arzt” in German) and forcefully relabeled them as “behandlers” or “providers,” thus erasing their noble medical identity.1 In 1933, all Jewish pediatricians were expelled or forced to resign from the German Society of Pediatrics and were no longer allowed to be called doctors. This deliberate and systematic humiliation of pediatric clinicians and scientists was followed by deporting the lowly “providers” to concentration camps. So why perpetuate this pernicious Nazi terminology?

2. The Federal Government. The term “provider” was introduced and propagated in Public Law 93-641 titled “The National Health Planning and Resource Development Act of 1974.” In that document, patients were referred to as “consumers” and physicians as “providers” (this term was used 19 times in that law). At that time, the civil service employees who drafted the law that marginalized physicians by using generic, nonmedical nomenclature may not have realized the dire consequences of relabeling physicians as “providers.”

Continue to: Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems...

3. Insurance companies, managed care companies, and consolidated health systems have jubilantly adopted the term “provider” because they can equate physicians with less expensive, nonphysician clinicians (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and certified registered nurse anesthetists), especially when physicians across several specialties (particularly psychiatry) are in short supply. None of these clinicians deserve to be labeled “providers,” either.

To understand why the term “provider” was used instead of “clinicians” or “clinical practitioner,” one must recognize the “businessification” of medicine and the commoditization of clinical care in our country. In some ways, health care has adopted a model similar to a fast-food joint, where workers provide customers with a hamburger. The question here is why did the 1.1 million physicians in the United States not halt this terminology shift before it spread and permeated the national health care system? Physicians who graduate from medical schools (not “provider” schools!) must vigorously and loudly fight back and put this wicked genie back in its bottle. This is feasible only if the American Medical Association (which would never conceive of itself as the “American Provider Association”), along with all 48 specialty organizations (Table), including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), unite and demand that physicians be called medical doctors or physicians, or by a term that reflects their specialty (orthopedists, psychiatrists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, cardiologists, etc.). This is an urgent issue to prevent the dissolution of our professional identity and its highly regarded societal image. It is a travesty that we physicians have allowed it to go on unopposed and to become entrenched in the dumbed-down jargon of health care. Physicians tend to avoid confrontation and adversarial stances, but we must unite and demand a return to the traditional nomenclature of medicine.

Much debate has emerged lately about an epidemic of “burnout” among physicians. Proposed causes include the savage increase in the amount of paperwork at the expense of patient care, the sense of helplessness that pre-authorization has inflicted on physicians’ decision-making, and the tyranny of relative value units (RVUs) as a benchmark for physician performance, as if healing patients is like manufacturing widgets. However, the blow to the self-esteem of physicians by being called “providers” daily is certainly another major factor contributing to burnout. It is perfectly legitimate for physicians to expect recognition for their long, rigorous, and uniquely advanced medical training, instead of being lumped together with less qualified professionals as anonymous “providers” in the name of politically correct pseudo-equality of all clinical practitioners. Let the administrators stop and contemplate whether tertiary or quaternary care for the most complex and severely ill patients in medical, surgical, or psychiatric intensive care units can operate without highly specialized physicians.

I urge APA leadership to take a visible and strong stand to rid psychiatrists of this assault on our medical identity. As I mentioned in my January 2020 editorial,2 it is vital that the name of our national psychiatric organization (APA) be modified to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, to remind all health care systems, as well as patients, the public, and the media, of our medical identity as physicians before we specialized in psychiatry.

Continue to: Patients, not clients

Patients, not clients

We should also emphasize that our suffering and medically ill patients with serious neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder are patients, not clients. The terminology used in community mental health centers around the country almost universally includes “providers” and “clients.” This de-medicalization of psychiatrists and our patients must be corrected and reversed so that the public understands that treating mental illness is not a business transaction between a “provider” and a “client.” Using the correct terminology may help generate sympathy and compassion towards patients with serious psychiatric illnesses, just as it does for patients with cancer, heart disease, or stroke. The term “client” will never evoke the public sympathy and support that our patients truly deserve.

Let’s keep this issue alive and translate our demands into actions, both locally and nationally. Psychiatrists and physicians of all other specialties must stand up for their rights and inform their systems of care that they must be called by their legitimate and lawful name: physicians or medical doctors (never “providers”). This is an issue that unites all 1.1 million of us. The US health care system would collapse without us, and asking that we be called exactly what our medical license displays is our right and our professional identity.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

1. Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of persecution. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8(5):324-328.

2. Nasrallah HA. 20 Reasons to celebrate our APA membership in 2020. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.