User login

Withdrawal of candidacy for APA President-Elect

To the readers of Current Psychiatry,

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed me on 12-27-19 that my editorial in the December issue about my candidacy for APA President-Elect was unfair to the other candidates because they should have been invited to publish their own statements side-by-side with mine. I was not aware of this because the APA election rules allow a candidate to blog or write on all social media or to send a mass mailing unilaterally. I take full responsibility for my mistake and decided to inform the APA Board of Trustees that I am withdrawing my candidacy for APA President-Elect. I hope the elections will go smoothly and wish the APA well.

Please note that my loyalty to the APA is very strong. That’s why my January 2020 editorial strongly urges all psychiatrists to join (or rejoin) the APA because unity will make it more possible for us to advocate for our patients, increase access to mental health, eliminate stigma, achieve true parity, and raise the profile of psychiatry as a medical discipline.

As you may have read in my campaign statement, one of my major goals as a candidate was to change the name of the APA to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This name change is critical so that the public knows our medical identity. It also will differentiate us from the other APA (American Psychological Association), which is the first to appear when anyone enters APA on Google or other search engines. I will lobby vigorously with the current APA president, the APA CEO, and whoever becomes President-Elect to get this name change approved by the Board of Trustees. I am very sure that the vast majority of psychiatrists will support such a name change.

Thank you and I hope 2020 will be a happy and healthy year for all of you, and for all our psychiatric patients.

To the readers of Current Psychiatry,

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed me on 12-27-19 that my editorial in the December issue about my candidacy for APA President-Elect was unfair to the other candidates because they should have been invited to publish their own statements side-by-side with mine. I was not aware of this because the APA election rules allow a candidate to blog or write on all social media or to send a mass mailing unilaterally. I take full responsibility for my mistake and decided to inform the APA Board of Trustees that I am withdrawing my candidacy for APA President-Elect. I hope the elections will go smoothly and wish the APA well.

Please note that my loyalty to the APA is very strong. That’s why my January 2020 editorial strongly urges all psychiatrists to join (or rejoin) the APA because unity will make it more possible for us to advocate for our patients, increase access to mental health, eliminate stigma, achieve true parity, and raise the profile of psychiatry as a medical discipline.

As you may have read in my campaign statement, one of my major goals as a candidate was to change the name of the APA to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This name change is critical so that the public knows our medical identity. It also will differentiate us from the other APA (American Psychological Association), which is the first to appear when anyone enters APA on Google or other search engines. I will lobby vigorously with the current APA president, the APA CEO, and whoever becomes President-Elect to get this name change approved by the Board of Trustees. I am very sure that the vast majority of psychiatrists will support such a name change.

Thank you and I hope 2020 will be a happy and healthy year for all of you, and for all our psychiatric patients.

To the readers of Current Psychiatry,

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed me on 12-27-19 that my editorial in the December issue about my candidacy for APA President-Elect was unfair to the other candidates because they should have been invited to publish their own statements side-by-side with mine. I was not aware of this because the APA election rules allow a candidate to blog or write on all social media or to send a mass mailing unilaterally. I take full responsibility for my mistake and decided to inform the APA Board of Trustees that I am withdrawing my candidacy for APA President-Elect. I hope the elections will go smoothly and wish the APA well.

Please note that my loyalty to the APA is very strong. That’s why my January 2020 editorial strongly urges all psychiatrists to join (or rejoin) the APA because unity will make it more possible for us to advocate for our patients, increase access to mental health, eliminate stigma, achieve true parity, and raise the profile of psychiatry as a medical discipline.

As you may have read in my campaign statement, one of my major goals as a candidate was to change the name of the APA to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This name change is critical so that the public knows our medical identity. It also will differentiate us from the other APA (American Psychological Association), which is the first to appear when anyone enters APA on Google or other search engines. I will lobby vigorously with the current APA president, the APA CEO, and whoever becomes President-Elect to get this name change approved by the Board of Trustees. I am very sure that the vast majority of psychiatrists will support such a name change.

Thank you and I hope 2020 will be a happy and healthy year for all of you, and for all our psychiatric patients.

Becoming the paradigm for clinical trial enrollment

The previous issue of The Sarcoma Journal focused on findings from numerous clinical trials in sarcomas of various histologies presented at ASCO’s annual meeting. This issue features a study on enrollment issues that surround clinical trials in sarcoma and sheds light on patient perceptions on clinical trial enrollment.

Clinical trials and their investigators are frequently impacted by enrollment issues, such as the limited number of eligible patients and the wide variations in time it can take to reach complete enrollment. For example, the phase 3 ANNOUNCE trial of olaratumab in soft tissue sarcoma completed its accrual of 509 patients in a record 10 months, while the trial of temozolomide by the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group took 6 years to enroll 120 patients. Recruitment difficulties may even hamper the investigators’ and sponsors’ ability to bring a trial to a meaningful conclusion.

An interesting finding from the study published in this issue is the correlation between knowledge about trials and the positive attitude towards participating in them. People who had participated in clinical trials had higher levels of knowledge and developed more favorable attitudes towards clinical trials. One of the goals of the Sarcoma Foundation of America (curesarcoma.org) is to increase awareness of the numbers and types of ongoing clinical trials in sarcoma, benefitting patients and investigators alike. The SFA operates the Clinical Trial Navigating Service, which offers patients, caregivers, and health care professionals up-to-date information about sarcoma clinical trials throughout the United States and Canada. The service, provided in collaboration with EmergingMed, helps patients search for clinical trial options that match their specific diagnosis and treatment history.

The paper published in this issue suggests that, through patient education and careful trial design, sarcoma could become a paradigm for trial enrollment in other therapeutic areas. Together—as physicians, investigators, patients, trial sponsors, and anyone interested in curing sarcoma—we may be able to accomplish this. It’s certainly worth a try.

William D. Tap, MD

Editor-in-Chief

The previous issue of The Sarcoma Journal focused on findings from numerous clinical trials in sarcomas of various histologies presented at ASCO’s annual meeting. This issue features a study on enrollment issues that surround clinical trials in sarcoma and sheds light on patient perceptions on clinical trial enrollment.

Clinical trials and their investigators are frequently impacted by enrollment issues, such as the limited number of eligible patients and the wide variations in time it can take to reach complete enrollment. For example, the phase 3 ANNOUNCE trial of olaratumab in soft tissue sarcoma completed its accrual of 509 patients in a record 10 months, while the trial of temozolomide by the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group took 6 years to enroll 120 patients. Recruitment difficulties may even hamper the investigators’ and sponsors’ ability to bring a trial to a meaningful conclusion.

An interesting finding from the study published in this issue is the correlation between knowledge about trials and the positive attitude towards participating in them. People who had participated in clinical trials had higher levels of knowledge and developed more favorable attitudes towards clinical trials. One of the goals of the Sarcoma Foundation of America (curesarcoma.org) is to increase awareness of the numbers and types of ongoing clinical trials in sarcoma, benefitting patients and investigators alike. The SFA operates the Clinical Trial Navigating Service, which offers patients, caregivers, and health care professionals up-to-date information about sarcoma clinical trials throughout the United States and Canada. The service, provided in collaboration with EmergingMed, helps patients search for clinical trial options that match their specific diagnosis and treatment history.

The paper published in this issue suggests that, through patient education and careful trial design, sarcoma could become a paradigm for trial enrollment in other therapeutic areas. Together—as physicians, investigators, patients, trial sponsors, and anyone interested in curing sarcoma—we may be able to accomplish this. It’s certainly worth a try.

William D. Tap, MD

Editor-in-Chief

The previous issue of The Sarcoma Journal focused on findings from numerous clinical trials in sarcomas of various histologies presented at ASCO’s annual meeting. This issue features a study on enrollment issues that surround clinical trials in sarcoma and sheds light on patient perceptions on clinical trial enrollment.

Clinical trials and their investigators are frequently impacted by enrollment issues, such as the limited number of eligible patients and the wide variations in time it can take to reach complete enrollment. For example, the phase 3 ANNOUNCE trial of olaratumab in soft tissue sarcoma completed its accrual of 509 patients in a record 10 months, while the trial of temozolomide by the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group took 6 years to enroll 120 patients. Recruitment difficulties may even hamper the investigators’ and sponsors’ ability to bring a trial to a meaningful conclusion.

An interesting finding from the study published in this issue is the correlation between knowledge about trials and the positive attitude towards participating in them. People who had participated in clinical trials had higher levels of knowledge and developed more favorable attitudes towards clinical trials. One of the goals of the Sarcoma Foundation of America (curesarcoma.org) is to increase awareness of the numbers and types of ongoing clinical trials in sarcoma, benefitting patients and investigators alike. The SFA operates the Clinical Trial Navigating Service, which offers patients, caregivers, and health care professionals up-to-date information about sarcoma clinical trials throughout the United States and Canada. The service, provided in collaboration with EmergingMed, helps patients search for clinical trial options that match their specific diagnosis and treatment history.

The paper published in this issue suggests that, through patient education and careful trial design, sarcoma could become a paradigm for trial enrollment in other therapeutic areas. Together—as physicians, investigators, patients, trial sponsors, and anyone interested in curing sarcoma—we may be able to accomplish this. It’s certainly worth a try.

William D. Tap, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Retained placenta after vaginal birth: How long should you wait to manually remove the placenta?

You have just safely delivered the baby who is quietly resting on her mother’s chest. You begin active management of the third stage of labor, administering oxytocin, performing uterine massage and applying controlled tension on the umbilical cord. There is no evidence of excess postpartum bleeding.

How long will you wait to deliver the placenta?

Active management of the third stage of labor

Most authorities recommend active management of the third stage of labor because active management reduces the risk of maternal hemorrhage >1,000 mL (relative risk [RR], 0.34), postpartum hemoglobin levels < 9 g/dL (RR, 0.50), and maternal blood transfusion (RR, 0.35) compared with expectant management.1

The most important component of active management of the third stage of labor is the administration of a uterotonic after delivery of the newborn. In the United States, oxytocin is the uterotonic most often utilized for the active management of the third stage of labor. Authors of a recent randomized clinical trial reported that intravenous oxytocin is superior to intramuscular oxytocin for reducing postpartum blood loss (385 vs 445 mL), the frequency of blood loss greater than 1,000 mL (4.6% vs 8.1%), and the rate of maternal blood transfusion (1.5% vs 4.4%).2

In addition to administering oxytocin, the active management of the third stage often involves maneuvers to accelerate placental delivery, including the Crede and Brandt-Andrews maneuvers and controlled tension on the umbilical cord. The Crede maneuver, described in 1853, involves placing a hand on the abdominal wall near the uterine fundus and squeezing the uterine fundus between the thumb and fingers.3,4

The Brandt-Andrews maneuver, described in 1933, involves placing a clamp on the umbilical cord close to the vulva.5 The clamp is used to apply judicious tension on the cord with one hand, while the other hand is placed on the mother’s abdomen with the palm and fingers overlying the junction between the uterine corpus and the lower segment. With judicious tension on the cord, the abdominal hand pushes the uterus upward toward the umbilicus. Placental separation is indicated when lengthening of the umbilical cord occurs. The Brandt-Andrews maneuver may be associated with fewer cases of uterine inversion than the Crede maneuver.5-7

Of note, umbilical cord traction has not been demonstrated to reduce the need for blood transfusion or the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) >1,000 mL, and it is commonly utilized by obstetricians and midwives.8,9 Hence, in the third stage, the delivering clinician should routinely administer a uterotonic, but use of judicious tension on the cord can be deferred if the woman prefers a noninterventional approach to delivery.

Following a vaginal birth, when should the diagnosis of retained placenta be made?

The historic definition of retained placenta is nonexpulsion of the placenta 30 minutes after delivery of the newborn. However, many observational studies report that, when active management of the third stage is utilized, 90%, 95%, and 99% of placentas deliver by 9 minutes, 13 minutes, and 28 minutes, respectively.10 In addition, many observational studies report that the incidence of PPH increases significantly with longer intervals between birth of the newborn and delivery of the placenta. In one study the rate of blood loss >500 mL was 8.5% when the placenta delivered between 5 and 9 minutes and 35.1% when the placenta delivered ≥30 minutes following birth of the baby.10 In another observational study, compared with women delivering the placenta < 10 minutes after birth, women delivering the placenta ≥30 minutes after birth had a 3-fold increased risk of PPH.11 Similar findings have been reported in other studies.12-14

Continue to: Based on the association between a delay in delivery...

Based on the association between a delay in delivery of the placenta and an increased risk of PPH, some authorities recommend that, in term pregnancy, the diagnosis of retained placenta should be made at 20 minutes following birth and consideration should be given to removing the placenta at this time. For women with effective neuraxial anesthesia, manual removal of the placenta 20 minutes following birth may be the best decision for balancing the benefit of preventing PPH with the risk of unnecessary intervention. For women with no anesthesia, delaying manual removal of the placenta to 30 minutes or more following birth may permit more time for the placenta to deliver prior to performing an intervention that might cause pain, but the delay increases the risk of PPH.

The retained placenta may prevent the uterine muscle from effectively contracting around penetrating veins and arteries, thereby increasing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. The placenta that has separated from the uterine wall but is trapped inside the uterine cavity can be removed easily with manual extraction. If the placenta is physiologically adherent to the uterine wall, a gentle sweeping motion with an intrauterine hand usually can separate the placenta from the uterus in preparation for manual extraction. However, if a placenta accreta spectrum disorder is contributing to a retained placenta, it may be difficult to separate the densely adherent portion of the uterus from the uterine wall. In the presence of placenta accreta spectrum disorder, vigorous attempts to remove the placenta may precipitate massive bleeding. In some cases, the acchoucheur/midwife may recognize the presence of a focal accreta and cease attempts to remove the placenta in order to organize the personnel and equipment needed to effectively treat a potential case of placenta accreta. In one study, when a placenta accreta was recognized or suspected, immediately ceasing attempts at manually removing the placenta resulted in better case outcomes than continued attempts to remove the placenta.1

Uterine inversion may occur during an attempt to manually remove the placenta. There is universal agreement that once a uterine inversion is recognized it is critically important to immediately restore normal uterine anatomy to avoid massive hemorrhage and maternal shock. The initial management of uterine inversion includes:

- stopping oxytocin infusion

- initiating high volume fluid resuscitation

- considering a dose of a uterine relaxant, such as nitroglycerin or terbutaline

- preparing for blood product replacement.

In my experience, when uterine inversion is immediately recognized and successfully treated, blood product replacement is not usually necessary. However, if uterine inversion has not been immediately recognized or treated, massive hemorrhage and shock may occur.

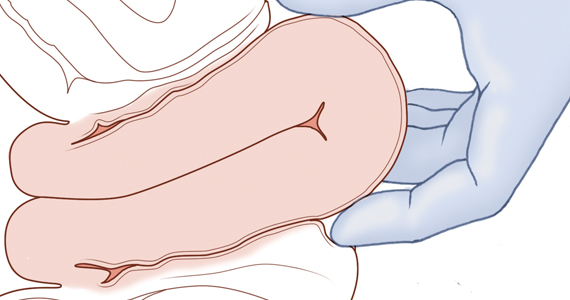

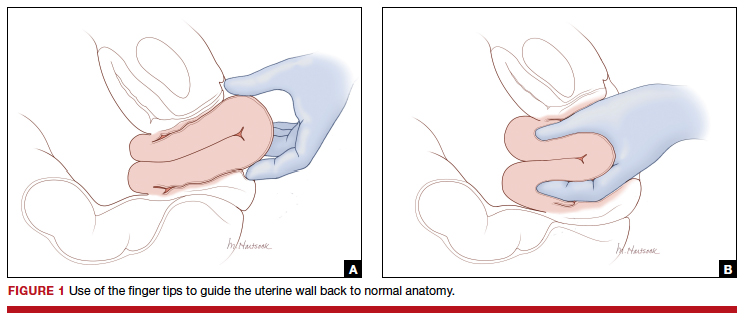

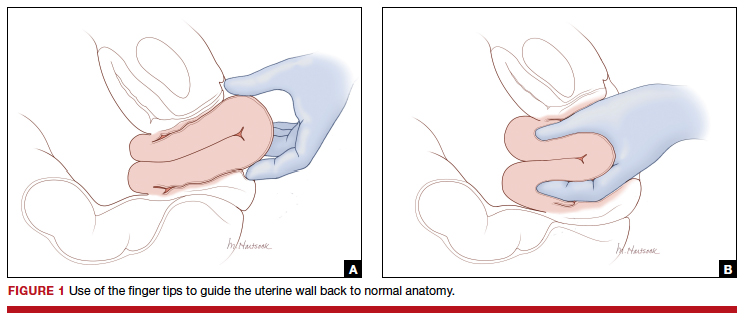

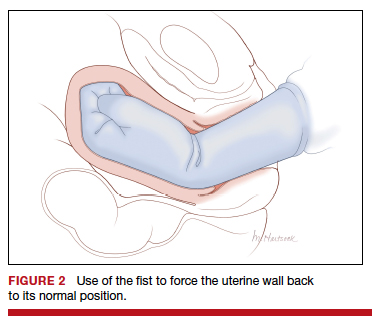

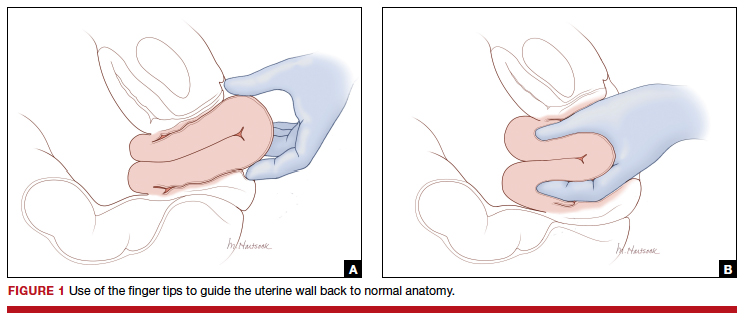

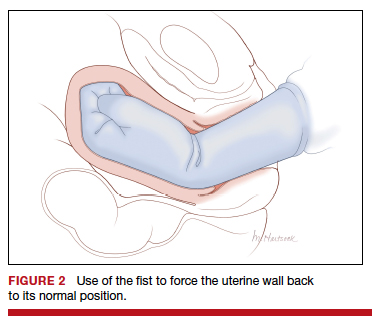

Two approaches to the vaginal restoration of uterine anatomy involve using the tips of the fingers and palm of the hand to guide the wall of the uterus back to its normal position (FIGURE 1) or to forcefully use a fist to force the uterine wall back to its normal position (FIGURE 2). If these maneuvers are unsuccessful, a laparotomy may be necessary.

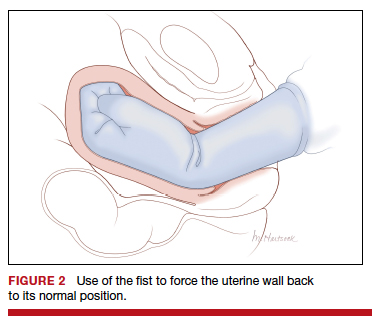

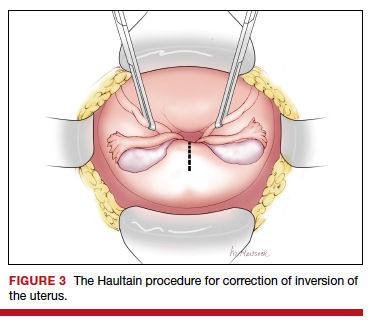

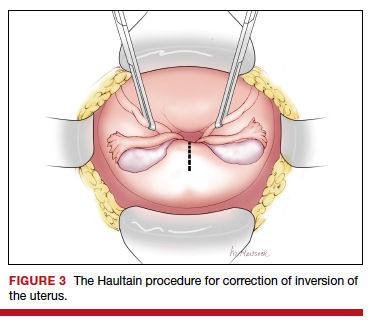

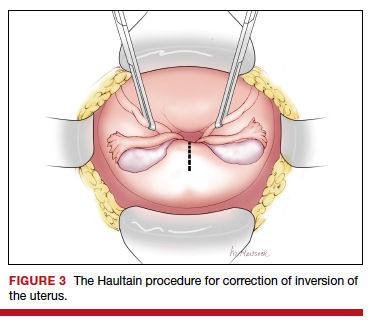

At laparotomy, the Huntington or Haultain procedures may help restore normal uterine anatomy. The Huntington procedure involves using clamps to apply symmetrical tension to the left and right round ligaments and/or uterine serosa to sequentially tease the uterus back to normal anatomy.2,3 The Haultain procedure involves a vertical incision on the posterior wall of the uterus to release the uterine constriction ring that is preventing the return of the uterine fundus to its normal position (FIGURE 3).4,5

References

- Kayem G, Anselem O, Schmitz T, et al. Conservative versus radical management in cases of placenta accreta: a historical study. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2007;36:680-687.

- Huntington JL. Acute inversion of the uterus. Boston Med Surg J. 1921;184:376-378.

- Huntington JL, Irving FC, Kellogg FS. Abdominal reposition in acute inversion of the puerperal uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1928;15:34-40.

- Haultain FW. Abdominal hysterotomy for chronic uterine inversion: a record of 3 cases. Proc Roy Soc Med. 1908;1:528-535.

- Easterday CL, Reid DE. Inversion of the puerperal uterus managed by the Haultain technique; A case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78:1224-1226.

Manual extraction of the placenta

Prior to performing manual extraction of the placenta, a decision should be made regarding the approach to anesthesia and perioperative antibiotics. Manual extraction of the placenta is performed by placing one hand on the uterine fundus to stabilize the uterus and using the other hand to follow the umbilical cord into the uterine cavity. The intrauterine hand is used to separate the uterine-placental interface with a gentle sweeping motion. The placental mass is grasped and gently teased through the cervix and vagina. Inspection of the placenta to ensure complete removal is necessary.

An alternative to manual extraction of the placenta is the use of Bierer forceps and ultrasound guidance to tease the placenta through the cervical os. This technique involves the following steps15:

1. use ultrasound to locate the placenta

2. place a ring forceps on the anterior lip of the cervix

3. introduce the Bierer forcep into the uterus

4. use the forceps to grasp the placenta and pull it toward the vagina

5. stop frequently to re-grasp placental tissue that is deeper in the uterine cavity

6. once the placenta is extracted, examine the placenta to ensure complete removal.

Of note when manual extraction is used to deliver a retained placenta, randomized clinical trials report no benefit for the following interventions:

- perioperative antibiotics16

- nitroglycerin to relax the uterus17

- ultrasound to detect retained placental tissue.18

Best timing for manual extraction of the placenta

The timing for the diagnosis of retained placenta, and the risks and benefits of manual extraction would be best evaluated in a large, randomized clinical trial. However, based on observational studies, in a term pregnancy, the diagnosis of retained placenta is best made using a 20-minute interval. In women with effective neuraxial anesthesia, consideration should be given to manual removal of the placenta at that time.

- Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD007412.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP. The evolving management of the third stage of labour. BJOG. 2009;116(suppl 1):26-28.

- Ebert AD, David M. Meilensteine der Praventionsmedizin. Carl Siegmund Franz Credé (1819-1882), der Credesche Handgriff und die Credesche Augenprophylaxe. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:675-678.

- Brandt ML. The mechanism and management of the third stage of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1933;25:662-667.

- Kimbell N. Brandt-Andrews technique of delivery of the placenta. Br Med J. 1958;1:203-204.

- De Lee JB, Greenhill JP. Principles and Practice of Obstetrics. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1947:275.

- Du Y, Ye M, Zheng F. Active management of the third stage of labor with and without controlled cord traction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:626-633.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mshweshwe NT, Gülmezoglu AM. Controlled cord traction for the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD008020.

- Frolova AI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. Duration of the third stage of labor and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:951-956.

- Shinar S, Schwartz A, Maslovitz S, et al. How long is safe? Setting the cutoff for uncomplicated third stage length: a retrospective case-control study. Birth. 2016;43:36-41.

- Magann EF, Evans S, Chauhan SP, et al. The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:290-293.

- Cummings K, Doherty DA, Magann EF, et al. Timing of manual placenta removal to prevent postpartum hemorrhage: is it time to act? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:3930-3933.

- Rabie NZ, Ounpraseuth S, Hughes D, et al. Association of the length of the third stage of labor and blood loss following vaginal delivery. South Med J. 2018;111:178-182.

- Rosenstein MG, Vargas JE, Drey EA. Ultrasound-guided instrumental removal of the retained placenta after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:180.e1-e3.

- Chibueze EC, Parsons AJ, Ota E, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for manual removal of retained placenta during vaginal birth: a systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:313.

- Abdel-Aleem H, Abdel-Aleem MA, Shaaban OM. Nitroglycerin for management of retained placenta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD007708.

- Weissback T, Haikin-Herzberger E, Bacci-Hugger K, et al. Immediate postpartum ultrasound evaluation for suspected retained placental tissue in patients undergoing manual removal of placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;192:37-40.

You have just safely delivered the baby who is quietly resting on her mother’s chest. You begin active management of the third stage of labor, administering oxytocin, performing uterine massage and applying controlled tension on the umbilical cord. There is no evidence of excess postpartum bleeding.

How long will you wait to deliver the placenta?

Active management of the third stage of labor

Most authorities recommend active management of the third stage of labor because active management reduces the risk of maternal hemorrhage >1,000 mL (relative risk [RR], 0.34), postpartum hemoglobin levels < 9 g/dL (RR, 0.50), and maternal blood transfusion (RR, 0.35) compared with expectant management.1

The most important component of active management of the third stage of labor is the administration of a uterotonic after delivery of the newborn. In the United States, oxytocin is the uterotonic most often utilized for the active management of the third stage of labor. Authors of a recent randomized clinical trial reported that intravenous oxytocin is superior to intramuscular oxytocin for reducing postpartum blood loss (385 vs 445 mL), the frequency of blood loss greater than 1,000 mL (4.6% vs 8.1%), and the rate of maternal blood transfusion (1.5% vs 4.4%).2

In addition to administering oxytocin, the active management of the third stage often involves maneuvers to accelerate placental delivery, including the Crede and Brandt-Andrews maneuvers and controlled tension on the umbilical cord. The Crede maneuver, described in 1853, involves placing a hand on the abdominal wall near the uterine fundus and squeezing the uterine fundus between the thumb and fingers.3,4

The Brandt-Andrews maneuver, described in 1933, involves placing a clamp on the umbilical cord close to the vulva.5 The clamp is used to apply judicious tension on the cord with one hand, while the other hand is placed on the mother’s abdomen with the palm and fingers overlying the junction between the uterine corpus and the lower segment. With judicious tension on the cord, the abdominal hand pushes the uterus upward toward the umbilicus. Placental separation is indicated when lengthening of the umbilical cord occurs. The Brandt-Andrews maneuver may be associated with fewer cases of uterine inversion than the Crede maneuver.5-7

Of note, umbilical cord traction has not been demonstrated to reduce the need for blood transfusion or the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) >1,000 mL, and it is commonly utilized by obstetricians and midwives.8,9 Hence, in the third stage, the delivering clinician should routinely administer a uterotonic, but use of judicious tension on the cord can be deferred if the woman prefers a noninterventional approach to delivery.

Following a vaginal birth, when should the diagnosis of retained placenta be made?

The historic definition of retained placenta is nonexpulsion of the placenta 30 minutes after delivery of the newborn. However, many observational studies report that, when active management of the third stage is utilized, 90%, 95%, and 99% of placentas deliver by 9 minutes, 13 minutes, and 28 minutes, respectively.10 In addition, many observational studies report that the incidence of PPH increases significantly with longer intervals between birth of the newborn and delivery of the placenta. In one study the rate of blood loss >500 mL was 8.5% when the placenta delivered between 5 and 9 minutes and 35.1% when the placenta delivered ≥30 minutes following birth of the baby.10 In another observational study, compared with women delivering the placenta < 10 minutes after birth, women delivering the placenta ≥30 minutes after birth had a 3-fold increased risk of PPH.11 Similar findings have been reported in other studies.12-14

Continue to: Based on the association between a delay in delivery...

Based on the association between a delay in delivery of the placenta and an increased risk of PPH, some authorities recommend that, in term pregnancy, the diagnosis of retained placenta should be made at 20 minutes following birth and consideration should be given to removing the placenta at this time. For women with effective neuraxial anesthesia, manual removal of the placenta 20 minutes following birth may be the best decision for balancing the benefit of preventing PPH with the risk of unnecessary intervention. For women with no anesthesia, delaying manual removal of the placenta to 30 minutes or more following birth may permit more time for the placenta to deliver prior to performing an intervention that might cause pain, but the delay increases the risk of PPH.

The retained placenta may prevent the uterine muscle from effectively contracting around penetrating veins and arteries, thereby increasing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. The placenta that has separated from the uterine wall but is trapped inside the uterine cavity can be removed easily with manual extraction. If the placenta is physiologically adherent to the uterine wall, a gentle sweeping motion with an intrauterine hand usually can separate the placenta from the uterus in preparation for manual extraction. However, if a placenta accreta spectrum disorder is contributing to a retained placenta, it may be difficult to separate the densely adherent portion of the uterus from the uterine wall. In the presence of placenta accreta spectrum disorder, vigorous attempts to remove the placenta may precipitate massive bleeding. In some cases, the acchoucheur/midwife may recognize the presence of a focal accreta and cease attempts to remove the placenta in order to organize the personnel and equipment needed to effectively treat a potential case of placenta accreta. In one study, when a placenta accreta was recognized or suspected, immediately ceasing attempts at manually removing the placenta resulted in better case outcomes than continued attempts to remove the placenta.1

Uterine inversion may occur during an attempt to manually remove the placenta. There is universal agreement that once a uterine inversion is recognized it is critically important to immediately restore normal uterine anatomy to avoid massive hemorrhage and maternal shock. The initial management of uterine inversion includes:

- stopping oxytocin infusion

- initiating high volume fluid resuscitation

- considering a dose of a uterine relaxant, such as nitroglycerin or terbutaline

- preparing for blood product replacement.

In my experience, when uterine inversion is immediately recognized and successfully treated, blood product replacement is not usually necessary. However, if uterine inversion has not been immediately recognized or treated, massive hemorrhage and shock may occur.

Two approaches to the vaginal restoration of uterine anatomy involve using the tips of the fingers and palm of the hand to guide the wall of the uterus back to its normal position (FIGURE 1) or to forcefully use a fist to force the uterine wall back to its normal position (FIGURE 2). If these maneuvers are unsuccessful, a laparotomy may be necessary.

At laparotomy, the Huntington or Haultain procedures may help restore normal uterine anatomy. The Huntington procedure involves using clamps to apply symmetrical tension to the left and right round ligaments and/or uterine serosa to sequentially tease the uterus back to normal anatomy.2,3 The Haultain procedure involves a vertical incision on the posterior wall of the uterus to release the uterine constriction ring that is preventing the return of the uterine fundus to its normal position (FIGURE 3).4,5

References

- Kayem G, Anselem O, Schmitz T, et al. Conservative versus radical management in cases of placenta accreta: a historical study. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2007;36:680-687.

- Huntington JL. Acute inversion of the uterus. Boston Med Surg J. 1921;184:376-378.

- Huntington JL, Irving FC, Kellogg FS. Abdominal reposition in acute inversion of the puerperal uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1928;15:34-40.

- Haultain FW. Abdominal hysterotomy for chronic uterine inversion: a record of 3 cases. Proc Roy Soc Med. 1908;1:528-535.

- Easterday CL, Reid DE. Inversion of the puerperal uterus managed by the Haultain technique; A case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78:1224-1226.

Manual extraction of the placenta

Prior to performing manual extraction of the placenta, a decision should be made regarding the approach to anesthesia and perioperative antibiotics. Manual extraction of the placenta is performed by placing one hand on the uterine fundus to stabilize the uterus and using the other hand to follow the umbilical cord into the uterine cavity. The intrauterine hand is used to separate the uterine-placental interface with a gentle sweeping motion. The placental mass is grasped and gently teased through the cervix and vagina. Inspection of the placenta to ensure complete removal is necessary.

An alternative to manual extraction of the placenta is the use of Bierer forceps and ultrasound guidance to tease the placenta through the cervical os. This technique involves the following steps15:

1. use ultrasound to locate the placenta

2. place a ring forceps on the anterior lip of the cervix

3. introduce the Bierer forcep into the uterus

4. use the forceps to grasp the placenta and pull it toward the vagina

5. stop frequently to re-grasp placental tissue that is deeper in the uterine cavity

6. once the placenta is extracted, examine the placenta to ensure complete removal.

Of note when manual extraction is used to deliver a retained placenta, randomized clinical trials report no benefit for the following interventions:

- perioperative antibiotics16

- nitroglycerin to relax the uterus17

- ultrasound to detect retained placental tissue.18

Best timing for manual extraction of the placenta

The timing for the diagnosis of retained placenta, and the risks and benefits of manual extraction would be best evaluated in a large, randomized clinical trial. However, based on observational studies, in a term pregnancy, the diagnosis of retained placenta is best made using a 20-minute interval. In women with effective neuraxial anesthesia, consideration should be given to manual removal of the placenta at that time.

You have just safely delivered the baby who is quietly resting on her mother’s chest. You begin active management of the third stage of labor, administering oxytocin, performing uterine massage and applying controlled tension on the umbilical cord. There is no evidence of excess postpartum bleeding.

How long will you wait to deliver the placenta?

Active management of the third stage of labor

Most authorities recommend active management of the third stage of labor because active management reduces the risk of maternal hemorrhage >1,000 mL (relative risk [RR], 0.34), postpartum hemoglobin levels < 9 g/dL (RR, 0.50), and maternal blood transfusion (RR, 0.35) compared with expectant management.1

The most important component of active management of the third stage of labor is the administration of a uterotonic after delivery of the newborn. In the United States, oxytocin is the uterotonic most often utilized for the active management of the third stage of labor. Authors of a recent randomized clinical trial reported that intravenous oxytocin is superior to intramuscular oxytocin for reducing postpartum blood loss (385 vs 445 mL), the frequency of blood loss greater than 1,000 mL (4.6% vs 8.1%), and the rate of maternal blood transfusion (1.5% vs 4.4%).2

In addition to administering oxytocin, the active management of the third stage often involves maneuvers to accelerate placental delivery, including the Crede and Brandt-Andrews maneuvers and controlled tension on the umbilical cord. The Crede maneuver, described in 1853, involves placing a hand on the abdominal wall near the uterine fundus and squeezing the uterine fundus between the thumb and fingers.3,4

The Brandt-Andrews maneuver, described in 1933, involves placing a clamp on the umbilical cord close to the vulva.5 The clamp is used to apply judicious tension on the cord with one hand, while the other hand is placed on the mother’s abdomen with the palm and fingers overlying the junction between the uterine corpus and the lower segment. With judicious tension on the cord, the abdominal hand pushes the uterus upward toward the umbilicus. Placental separation is indicated when lengthening of the umbilical cord occurs. The Brandt-Andrews maneuver may be associated with fewer cases of uterine inversion than the Crede maneuver.5-7

Of note, umbilical cord traction has not been demonstrated to reduce the need for blood transfusion or the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) >1,000 mL, and it is commonly utilized by obstetricians and midwives.8,9 Hence, in the third stage, the delivering clinician should routinely administer a uterotonic, but use of judicious tension on the cord can be deferred if the woman prefers a noninterventional approach to delivery.

Following a vaginal birth, when should the diagnosis of retained placenta be made?

The historic definition of retained placenta is nonexpulsion of the placenta 30 minutes after delivery of the newborn. However, many observational studies report that, when active management of the third stage is utilized, 90%, 95%, and 99% of placentas deliver by 9 minutes, 13 minutes, and 28 minutes, respectively.10 In addition, many observational studies report that the incidence of PPH increases significantly with longer intervals between birth of the newborn and delivery of the placenta. In one study the rate of blood loss >500 mL was 8.5% when the placenta delivered between 5 and 9 minutes and 35.1% when the placenta delivered ≥30 minutes following birth of the baby.10 In another observational study, compared with women delivering the placenta < 10 minutes after birth, women delivering the placenta ≥30 minutes after birth had a 3-fold increased risk of PPH.11 Similar findings have been reported in other studies.12-14

Continue to: Based on the association between a delay in delivery...

Based on the association between a delay in delivery of the placenta and an increased risk of PPH, some authorities recommend that, in term pregnancy, the diagnosis of retained placenta should be made at 20 minutes following birth and consideration should be given to removing the placenta at this time. For women with effective neuraxial anesthesia, manual removal of the placenta 20 minutes following birth may be the best decision for balancing the benefit of preventing PPH with the risk of unnecessary intervention. For women with no anesthesia, delaying manual removal of the placenta to 30 minutes or more following birth may permit more time for the placenta to deliver prior to performing an intervention that might cause pain, but the delay increases the risk of PPH.

The retained placenta may prevent the uterine muscle from effectively contracting around penetrating veins and arteries, thereby increasing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. The placenta that has separated from the uterine wall but is trapped inside the uterine cavity can be removed easily with manual extraction. If the placenta is physiologically adherent to the uterine wall, a gentle sweeping motion with an intrauterine hand usually can separate the placenta from the uterus in preparation for manual extraction. However, if a placenta accreta spectrum disorder is contributing to a retained placenta, it may be difficult to separate the densely adherent portion of the uterus from the uterine wall. In the presence of placenta accreta spectrum disorder, vigorous attempts to remove the placenta may precipitate massive bleeding. In some cases, the acchoucheur/midwife may recognize the presence of a focal accreta and cease attempts to remove the placenta in order to organize the personnel and equipment needed to effectively treat a potential case of placenta accreta. In one study, when a placenta accreta was recognized or suspected, immediately ceasing attempts at manually removing the placenta resulted in better case outcomes than continued attempts to remove the placenta.1

Uterine inversion may occur during an attempt to manually remove the placenta. There is universal agreement that once a uterine inversion is recognized it is critically important to immediately restore normal uterine anatomy to avoid massive hemorrhage and maternal shock. The initial management of uterine inversion includes:

- stopping oxytocin infusion

- initiating high volume fluid resuscitation

- considering a dose of a uterine relaxant, such as nitroglycerin or terbutaline

- preparing for blood product replacement.

In my experience, when uterine inversion is immediately recognized and successfully treated, blood product replacement is not usually necessary. However, if uterine inversion has not been immediately recognized or treated, massive hemorrhage and shock may occur.

Two approaches to the vaginal restoration of uterine anatomy involve using the tips of the fingers and palm of the hand to guide the wall of the uterus back to its normal position (FIGURE 1) or to forcefully use a fist to force the uterine wall back to its normal position (FIGURE 2). If these maneuvers are unsuccessful, a laparotomy may be necessary.

At laparotomy, the Huntington or Haultain procedures may help restore normal uterine anatomy. The Huntington procedure involves using clamps to apply symmetrical tension to the left and right round ligaments and/or uterine serosa to sequentially tease the uterus back to normal anatomy.2,3 The Haultain procedure involves a vertical incision on the posterior wall of the uterus to release the uterine constriction ring that is preventing the return of the uterine fundus to its normal position (FIGURE 3).4,5

References

- Kayem G, Anselem O, Schmitz T, et al. Conservative versus radical management in cases of placenta accreta: a historical study. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2007;36:680-687.

- Huntington JL. Acute inversion of the uterus. Boston Med Surg J. 1921;184:376-378.

- Huntington JL, Irving FC, Kellogg FS. Abdominal reposition in acute inversion of the puerperal uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1928;15:34-40.

- Haultain FW. Abdominal hysterotomy for chronic uterine inversion: a record of 3 cases. Proc Roy Soc Med. 1908;1:528-535.

- Easterday CL, Reid DE. Inversion of the puerperal uterus managed by the Haultain technique; A case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78:1224-1226.

Manual extraction of the placenta

Prior to performing manual extraction of the placenta, a decision should be made regarding the approach to anesthesia and perioperative antibiotics. Manual extraction of the placenta is performed by placing one hand on the uterine fundus to stabilize the uterus and using the other hand to follow the umbilical cord into the uterine cavity. The intrauterine hand is used to separate the uterine-placental interface with a gentle sweeping motion. The placental mass is grasped and gently teased through the cervix and vagina. Inspection of the placenta to ensure complete removal is necessary.

An alternative to manual extraction of the placenta is the use of Bierer forceps and ultrasound guidance to tease the placenta through the cervical os. This technique involves the following steps15:

1. use ultrasound to locate the placenta

2. place a ring forceps on the anterior lip of the cervix

3. introduce the Bierer forcep into the uterus

4. use the forceps to grasp the placenta and pull it toward the vagina

5. stop frequently to re-grasp placental tissue that is deeper in the uterine cavity

6. once the placenta is extracted, examine the placenta to ensure complete removal.

Of note when manual extraction is used to deliver a retained placenta, randomized clinical trials report no benefit for the following interventions:

- perioperative antibiotics16

- nitroglycerin to relax the uterus17

- ultrasound to detect retained placental tissue.18

Best timing for manual extraction of the placenta

The timing for the diagnosis of retained placenta, and the risks and benefits of manual extraction would be best evaluated in a large, randomized clinical trial. However, based on observational studies, in a term pregnancy, the diagnosis of retained placenta is best made using a 20-minute interval. In women with effective neuraxial anesthesia, consideration should be given to manual removal of the placenta at that time.

- Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD007412.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP. The evolving management of the third stage of labour. BJOG. 2009;116(suppl 1):26-28.

- Ebert AD, David M. Meilensteine der Praventionsmedizin. Carl Siegmund Franz Credé (1819-1882), der Credesche Handgriff und die Credesche Augenprophylaxe. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:675-678.

- Brandt ML. The mechanism and management of the third stage of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1933;25:662-667.

- Kimbell N. Brandt-Andrews technique of delivery of the placenta. Br Med J. 1958;1:203-204.

- De Lee JB, Greenhill JP. Principles and Practice of Obstetrics. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1947:275.

- Du Y, Ye M, Zheng F. Active management of the third stage of labor with and without controlled cord traction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:626-633.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mshweshwe NT, Gülmezoglu AM. Controlled cord traction for the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD008020.

- Frolova AI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. Duration of the third stage of labor and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:951-956.

- Shinar S, Schwartz A, Maslovitz S, et al. How long is safe? Setting the cutoff for uncomplicated third stage length: a retrospective case-control study. Birth. 2016;43:36-41.

- Magann EF, Evans S, Chauhan SP, et al. The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:290-293.

- Cummings K, Doherty DA, Magann EF, et al. Timing of manual placenta removal to prevent postpartum hemorrhage: is it time to act? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:3930-3933.

- Rabie NZ, Ounpraseuth S, Hughes D, et al. Association of the length of the third stage of labor and blood loss following vaginal delivery. South Med J. 2018;111:178-182.

- Rosenstein MG, Vargas JE, Drey EA. Ultrasound-guided instrumental removal of the retained placenta after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:180.e1-e3.

- Chibueze EC, Parsons AJ, Ota E, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for manual removal of retained placenta during vaginal birth: a systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:313.

- Abdel-Aleem H, Abdel-Aleem MA, Shaaban OM. Nitroglycerin for management of retained placenta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD007708.

- Weissback T, Haikin-Herzberger E, Bacci-Hugger K, et al. Immediate postpartum ultrasound evaluation for suspected retained placental tissue in patients undergoing manual removal of placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;192:37-40.

- Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD007412.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP. The evolving management of the third stage of labour. BJOG. 2009;116(suppl 1):26-28.

- Ebert AD, David M. Meilensteine der Praventionsmedizin. Carl Siegmund Franz Credé (1819-1882), der Credesche Handgriff und die Credesche Augenprophylaxe. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:675-678.

- Brandt ML. The mechanism and management of the third stage of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1933;25:662-667.

- Kimbell N. Brandt-Andrews technique of delivery of the placenta. Br Med J. 1958;1:203-204.

- De Lee JB, Greenhill JP. Principles and Practice of Obstetrics. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1947:275.

- Du Y, Ye M, Zheng F. Active management of the third stage of labor with and without controlled cord traction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:626-633.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Mshweshwe NT, Gülmezoglu AM. Controlled cord traction for the third stage of labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD008020.

- Frolova AI, Stout MJ, Tuuli MG, et al. Duration of the third stage of labor and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:951-956.

- Shinar S, Schwartz A, Maslovitz S, et al. How long is safe? Setting the cutoff for uncomplicated third stage length: a retrospective case-control study. Birth. 2016;43:36-41.

- Magann EF, Evans S, Chauhan SP, et al. The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:290-293.

- Cummings K, Doherty DA, Magann EF, et al. Timing of manual placenta removal to prevent postpartum hemorrhage: is it time to act? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:3930-3933.

- Rabie NZ, Ounpraseuth S, Hughes D, et al. Association of the length of the third stage of labor and blood loss following vaginal delivery. South Med J. 2018;111:178-182.

- Rosenstein MG, Vargas JE, Drey EA. Ultrasound-guided instrumental removal of the retained placenta after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:180.e1-e3.

- Chibueze EC, Parsons AJ, Ota E, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for manual removal of retained placenta during vaginal birth: a systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:313.

- Abdel-Aleem H, Abdel-Aleem MA, Shaaban OM. Nitroglycerin for management of retained placenta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD007708.

- Weissback T, Haikin-Herzberger E, Bacci-Hugger K, et al. Immediate postpartum ultrasound evaluation for suspected retained placental tissue in patients undergoing manual removal of placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;192:37-40.

Off-label and oft-prescribed

In no way do I minimize the value of the imprimatur of FDA approval stating a drug, after appropriate preclinical and clinical studies, is deemed safe and effective. Whatever the agency’s shortcomings, the story of thalidomide (a drug never approved by the FDA) gives credence to the value of having a robust approval process. Arguments will likely continue forever as to whether the agency errs on the side of being too permissive or too restrictive in its approval process.

Nonetheless, I believe there are valid clinical reasons why we should continue to prescribe FDA-approved medications for nonapproved indications. In my practice, I treat some conditions that are sufficiently uncommon or heterogeneous in expression that large-scale clinical trials are logistically hard to carry out or deemed financially unviable by the corporate sponsor, even though clinical experience has informed us of a reasonable likelihood of efficacy. Sometimes drugs have “failed” in clinical trials, but experience and post hoc subset analysis of data have indicated a likely positive response in certain patients.

Although a drug that has been FDA approved has passed significant safety testing, the patients exposed to the drug when it was evaluated for treating a certain disease may be strikingly different from patients who have a different disease—the age, sex, comorbidities, and coprescribed medications may all differ significantly in the population of patients with the “off-label” disorder. Hence, appropriate caution is warranted, and if relevant, this should be explained to patients before giving them the medication.

In this issue of the Journal, 2 papers address the use of medications in an “off-label” manner. Schneider and colleagues discuss several frequent clinical uses of tricyclic antidepressants for reasons other than depression, and Modesto-Lowe and colleagues review the more controversial use of gabapentin in patients with alcohol use disorder. The hoped-for benefits in both circumstances are symptomatic, and both benefits and side effects are dose-related in ways not necessarily coinciding with those in the FDA-labeled indications.

My experience in using tricyclics as adjunctive treatment for fibromyalgia is that patients are quite sensitive to some of the side effects of the drugs (eg, oral dryness and fatigue), even in low doses. Moreover, we should expect only modest benefits, which should be explicitly described to the patient: improved quality of sleep with resultant decreased fatigue (while we watch closely for worsened fatigue from too-high dosing) and a modest reduction in pain over time as part of a multimodality treatment plan. I often find that practitioners who are less familiar with the use of these medications in this setting tend to start at lowish (but higher than often tolerated) doses, have patients take the medication too close to bedtime (resulting in some morning hangover sensation), fail to discuss the timing and degree of expected pain relief, don’t titrate the dose over time, and are not aware of the different responses that patients may experience with different medications within the same class. As with all prescribed medications, the benefits and ill effects must be frequently assessed, and particularly with these medications, one must be willing to discontinue them if appropriate outcomes are not achieved.

“Off-label” should not imply off the table as a therapeutic option. But it is incumbent on us to devote sufficient time to explain to each patient the anticipated side effects and hoped-for benefits, particularly since in most cases, we and our patients cannot refer to the results of definitive phase 3 clinical trials or patient online information sites that are totally relevant, reliable, data supported, and FDA reviewed.

In no way do I minimize the value of the imprimatur of FDA approval stating a drug, after appropriate preclinical and clinical studies, is deemed safe and effective. Whatever the agency’s shortcomings, the story of thalidomide (a drug never approved by the FDA) gives credence to the value of having a robust approval process. Arguments will likely continue forever as to whether the agency errs on the side of being too permissive or too restrictive in its approval process.

Nonetheless, I believe there are valid clinical reasons why we should continue to prescribe FDA-approved medications for nonapproved indications. In my practice, I treat some conditions that are sufficiently uncommon or heterogeneous in expression that large-scale clinical trials are logistically hard to carry out or deemed financially unviable by the corporate sponsor, even though clinical experience has informed us of a reasonable likelihood of efficacy. Sometimes drugs have “failed” in clinical trials, but experience and post hoc subset analysis of data have indicated a likely positive response in certain patients.

Although a drug that has been FDA approved has passed significant safety testing, the patients exposed to the drug when it was evaluated for treating a certain disease may be strikingly different from patients who have a different disease—the age, sex, comorbidities, and coprescribed medications may all differ significantly in the population of patients with the “off-label” disorder. Hence, appropriate caution is warranted, and if relevant, this should be explained to patients before giving them the medication.

In this issue of the Journal, 2 papers address the use of medications in an “off-label” manner. Schneider and colleagues discuss several frequent clinical uses of tricyclic antidepressants for reasons other than depression, and Modesto-Lowe and colleagues review the more controversial use of gabapentin in patients with alcohol use disorder. The hoped-for benefits in both circumstances are symptomatic, and both benefits and side effects are dose-related in ways not necessarily coinciding with those in the FDA-labeled indications.

My experience in using tricyclics as adjunctive treatment for fibromyalgia is that patients are quite sensitive to some of the side effects of the drugs (eg, oral dryness and fatigue), even in low doses. Moreover, we should expect only modest benefits, which should be explicitly described to the patient: improved quality of sleep with resultant decreased fatigue (while we watch closely for worsened fatigue from too-high dosing) and a modest reduction in pain over time as part of a multimodality treatment plan. I often find that practitioners who are less familiar with the use of these medications in this setting tend to start at lowish (but higher than often tolerated) doses, have patients take the medication too close to bedtime (resulting in some morning hangover sensation), fail to discuss the timing and degree of expected pain relief, don’t titrate the dose over time, and are not aware of the different responses that patients may experience with different medications within the same class. As with all prescribed medications, the benefits and ill effects must be frequently assessed, and particularly with these medications, one must be willing to discontinue them if appropriate outcomes are not achieved.

“Off-label” should not imply off the table as a therapeutic option. But it is incumbent on us to devote sufficient time to explain to each patient the anticipated side effects and hoped-for benefits, particularly since in most cases, we and our patients cannot refer to the results of definitive phase 3 clinical trials or patient online information sites that are totally relevant, reliable, data supported, and FDA reviewed.

In no way do I minimize the value of the imprimatur of FDA approval stating a drug, after appropriate preclinical and clinical studies, is deemed safe and effective. Whatever the agency’s shortcomings, the story of thalidomide (a drug never approved by the FDA) gives credence to the value of having a robust approval process. Arguments will likely continue forever as to whether the agency errs on the side of being too permissive or too restrictive in its approval process.

Nonetheless, I believe there are valid clinical reasons why we should continue to prescribe FDA-approved medications for nonapproved indications. In my practice, I treat some conditions that are sufficiently uncommon or heterogeneous in expression that large-scale clinical trials are logistically hard to carry out or deemed financially unviable by the corporate sponsor, even though clinical experience has informed us of a reasonable likelihood of efficacy. Sometimes drugs have “failed” in clinical trials, but experience and post hoc subset analysis of data have indicated a likely positive response in certain patients.

Although a drug that has been FDA approved has passed significant safety testing, the patients exposed to the drug when it was evaluated for treating a certain disease may be strikingly different from patients who have a different disease—the age, sex, comorbidities, and coprescribed medications may all differ significantly in the population of patients with the “off-label” disorder. Hence, appropriate caution is warranted, and if relevant, this should be explained to patients before giving them the medication.

In this issue of the Journal, 2 papers address the use of medications in an “off-label” manner. Schneider and colleagues discuss several frequent clinical uses of tricyclic antidepressants for reasons other than depression, and Modesto-Lowe and colleagues review the more controversial use of gabapentin in patients with alcohol use disorder. The hoped-for benefits in both circumstances are symptomatic, and both benefits and side effects are dose-related in ways not necessarily coinciding with those in the FDA-labeled indications.

My experience in using tricyclics as adjunctive treatment for fibromyalgia is that patients are quite sensitive to some of the side effects of the drugs (eg, oral dryness and fatigue), even in low doses. Moreover, we should expect only modest benefits, which should be explicitly described to the patient: improved quality of sleep with resultant decreased fatigue (while we watch closely for worsened fatigue from too-high dosing) and a modest reduction in pain over time as part of a multimodality treatment plan. I often find that practitioners who are less familiar with the use of these medications in this setting tend to start at lowish (but higher than often tolerated) doses, have patients take the medication too close to bedtime (resulting in some morning hangover sensation), fail to discuss the timing and degree of expected pain relief, don’t titrate the dose over time, and are not aware of the different responses that patients may experience with different medications within the same class. As with all prescribed medications, the benefits and ill effects must be frequently assessed, and particularly with these medications, one must be willing to discontinue them if appropriate outcomes are not achieved.

“Off-label” should not imply off the table as a therapeutic option. But it is incumbent on us to devote sufficient time to explain to each patient the anticipated side effects and hoped-for benefits, particularly since in most cases, we and our patients cannot refer to the results of definitive phase 3 clinical trials or patient online information sites that are totally relevant, reliable, data supported, and FDA reviewed.

My vision as a candidate for APA President-Elect

Note: Dr. Nasrallah has withdrawn his candidacy for APA President-Elect. For a statement of explanation click here.

I have been informed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Nominating Committee that I am a candidate for the position of APA President-Elect. I am honored to be nominated along with 2 other esteemed psychiatrists, David C. Henderson, MD, and Vivian B. Pender, MD.

You have all known me for many years as Editor-in-Chief of this journal, and probably have read many of my 150 editorials in which I frequently discussed and commented on not only the challenges that face psychiatry, but also the great promise and bright future of our evolving clinical neuroscience medical specialty. You can access all of these at MDedge.com/psychiatry/editor.

In this pre-election editorial, I would like to tell you about my qualifications as a candidate for this critical national psychiatry leadership role. Most of you are APA members who will have the opportunity to vote for the candidate of your choice from January 2 to 31, 2020. I hope that you will support my candidacy after learning about my long-standing involvement within the APA governance, as well as my 3 decades of academic leadership experience and productivity. You also know where I stand on the issues from my writings in

APA involvement

- President, Missouri Psychiatric Physicians Association District Branch (2017-2018)

- President, Cincinnati Psychiatric Society (2007-2009)

- President, Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Foundation (2008-2013)

- Editor, Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association (OPPA) Newsletter (Insight Matters) (2003-2008)

- Executive Council, OPPA (2003-2013)

- APA Council on Research (1993-2000)

- APA Committee on Research in Psychiatric Treatments (1992-1995)

- APA Task Force on Schizophrenia (1998-1999)

- President, Ohio Psychiatric Association Education and Research Foundation (1987-1994)

Academic track record

- Served as Chief of Psychiatry, VA Medical Center, Iowa City, Iowa for 6 years; Chair, Department of Psychiatry, The Ohio State University for 12 years; Chair, Department of Psychiatry, Saint Louis University for 6 years; and Associate Dean, University of Cincinnati for 4 years

- Published >700 articles, 570 abstracts, and 14 books

- Recruited and developed dozens of faculty members; supervised and mentored hundreds of residents, many of whom became medical directors, department chairs, and/or distinguished clinicians

- Received numerous awards and recognitions for clinical, teaching, and research excellence

- Serve as Editor for 3 journals (Current Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Research, and Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry)

Statement of vision and priorities

I am very optimistic about the future of psychiatry. The breakthroughs and advances in neuroscience all bolster the scientific basis of psychiatric disorders, and will lead to many novel treatments in the future. Psychiatry is a medical specialty that is now much more integrated into the “big tent” of medicine. Psychiatrists are physicians, and I believe the name of our association must reflect that. I was successful in changing the names of 2 district branches to include “physicians” (Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association and Missouri Psychiatric Physicians Association). If elected, I will propose to the Board of Trustees and the APA members that we change our name to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, which will emphasize our medical identity within mental health. In its 175-year history, the APA has experienced 2 previous name changes.

I believe the strengths of the APA far exceed its weaknesses, and its opportunities outnumber its threats. However, the following perennial challenges must be forcefully addressed by all of us:

- The pernicious and discriminatory dogma of stigma must be shattered for the sake of patients, their families, their psychiatrists, and the profession.

- Pre-authorization is essentially the insurance companies practicing medicine without a license when, without ever actually examining the patient, they tell physicians what they should or should not prescribe. That’s felonious!

- Competent and safe prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training (approximately 14,000 hours) and psychologists do not qualify.

- Board certification fees must be reduced, and recertification (Maintenance of Certification) must be simpler and less onerous.

- Effective parity laws must have teeth, not just words!

- Patient care, not computer care! Electronic health records must be more user-friendly and less time-consuming.

- Patients with psychiatric illness who have relapsed must be surrounded by compassionate medical professionals in a hospital setting, not by armed guards in a jail or prison.

- The shortage of psychiatrists can be remedied if the government funds additional residency slots as it did in the 1960s and 1970s. The number of applicants for psychiatric training is rapidly rising, but the number of residency slots has not changed for decades. Approximately 100 US medical school graduates did not match last year, along with >1,000 international medical graduate applicants.

- Lawyers have clients; psychiatrists have patients (as do cardiologists, neurologists, and oncologists). The term “clients” de-medicalizes psychiatric disorders and does not evoke public support or compassion.

- Psychotherapy is in fact a neurobiologic treatment that repairs the mind via neuroplasticity and synaptogenesis. It should get the same respect as pharmacotherapy.

- Untether psychiatric reimbursement from “time”! Psychiatric assessment and treatment are medical procedures. Excising depression, psychosis, panic attacks, or suicidal urges are to the mind what surgery is to the body.

- Clinical psychiatrists have much to offer for medical advances. Their observations generate hypotheses, and if these are published as a case report or letter to the editor, researchers can conduct hypothesis-testing and discover new treatments thanks to astute clinicians.

- The FDA should allow clinical trials to investigate treatments of symptoms, not (often heterogenous) DSM diagnoses. This will enable “off-label use” of medication, which often is necessary.

Continue to: Annual dues

Annual dues. The APA is a great organization that should continue to re-invent itself and re-engineer its procedures and business practices to generate additional revenue streams that could help reduce its annual dues. I know many members who complain about the APA dues, and former members who dropped out because of what they consider to be high dues.

Public education. The APA must intensify public education across all media platforms. This will help dispel myths, eliminate stigma, enforce parity, and portray psychiatry as a medical and scientific discipline. We have a great story to tell about how neurologic circuitry generates the mind and its mental functions, and the neurobiologic foundations of psychiatric brain disorders.

The APA should advocate for (and perhaps organize) an annual mental health check-up (online) in children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly for early detection and intervention.

Collaborative care. We should have close relationships with obstetricians to help prevent neurodevelopmental pathology due to perinatal complications as well as to manage depression in women in the pre- and postpartum phases. Collaborative care with pediatricians, family physicians, internists, and neurologists is necessary to integrate physical and mental health care for our patients, many of whom have multiple medical comorbidities and premature mortality.

Lobbying. The APA must intensify its lobbying to address the unacceptably high rate of suicide, addiction-related deaths, posttraumatic stress disorder due to trauma in children and adults, threats to mental health due to climate change and pollution, refugee mental health, stressful political zeitgeist, and the woefully high rate of uninsured or under-insured individuals.

Continue to: Industry

Industry. There are many significant unmet treatment needs in psychiatry. Approximately 82% of DSM disorders do not have any FDA-approved medication. The APA should constructively engage the pharmaceutical industry (the only entity that develops medications for our patients!) to do more research and development of therapies for conditions with no approved treatments, and to explore new mechanisms of action for more effective or tolerable psychiatric medications. Importantly, the APA should urge major pharmaceutical companies not to abandon neuropsychiatric disorders because they afflict tens of millions of US citizens and are the top causes of long-term disabilities.

Journals. The APA should consider rebranding its journals as “JAPA,” similar to JAMA, which will widen its influence and generate revenue to fund various priorities.

Telepsychiatry. And why can’t the APA create a national telepsychiatry network to meet the needs of underserved populations who have very little access to psychiatric care as in many rural areas? Private companies have filled that space, but the APA and its members can do it better, and this can become a benefit of membership.

Brain bank. Finally, the APA should consider establishing a “Brain Bank” of various psychiatric subspecialties to consult and advise the military, college administrators, corporations, and government agencies about strategies and tactics to solve many problems that arise from overt or covert psychiatric illnesses among their employees, staff, students, or constituents.

The APA cannot solve all societal problems, but it has the moral authority and clinical/scientific depth and gravitas to create an agenda of solutions and to partner with many other stakeholders to achieve mutual societal health goals.

Note: Dr. Nasrallah has withdrawn his candidacy for APA President-Elect. For a statement of explanation click here.

I have been informed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Nominating Committee that I am a candidate for the position of APA President-Elect. I am honored to be nominated along with 2 other esteemed psychiatrists, David C. Henderson, MD, and Vivian B. Pender, MD.

You have all known me for many years as Editor-in-Chief of this journal, and probably have read many of my 150 editorials in which I frequently discussed and commented on not only the challenges that face psychiatry, but also the great promise and bright future of our evolving clinical neuroscience medical specialty. You can access all of these at MDedge.com/psychiatry/editor.

In this pre-election editorial, I would like to tell you about my qualifications as a candidate for this critical national psychiatry leadership role. Most of you are APA members who will have the opportunity to vote for the candidate of your choice from January 2 to 31, 2020. I hope that you will support my candidacy after learning about my long-standing involvement within the APA governance, as well as my 3 decades of academic leadership experience and productivity. You also know where I stand on the issues from my writings in

APA involvement

- President, Missouri Psychiatric Physicians Association District Branch (2017-2018)

- President, Cincinnati Psychiatric Society (2007-2009)

- President, Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Foundation (2008-2013)

- Editor, Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association (OPPA) Newsletter (Insight Matters) (2003-2008)

- Executive Council, OPPA (2003-2013)

- APA Council on Research (1993-2000)

- APA Committee on Research in Psychiatric Treatments (1992-1995)

- APA Task Force on Schizophrenia (1998-1999)

- President, Ohio Psychiatric Association Education and Research Foundation (1987-1994)

Academic track record

- Served as Chief of Psychiatry, VA Medical Center, Iowa City, Iowa for 6 years; Chair, Department of Psychiatry, The Ohio State University for 12 years; Chair, Department of Psychiatry, Saint Louis University for 6 years; and Associate Dean, University of Cincinnati for 4 years

- Published >700 articles, 570 abstracts, and 14 books

- Recruited and developed dozens of faculty members; supervised and mentored hundreds of residents, many of whom became medical directors, department chairs, and/or distinguished clinicians

- Received numerous awards and recognitions for clinical, teaching, and research excellence

- Serve as Editor for 3 journals (Current Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Research, and Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry)

Statement of vision and priorities

I am very optimistic about the future of psychiatry. The breakthroughs and advances in neuroscience all bolster the scientific basis of psychiatric disorders, and will lead to many novel treatments in the future. Psychiatry is a medical specialty that is now much more integrated into the “big tent” of medicine. Psychiatrists are physicians, and I believe the name of our association must reflect that. I was successful in changing the names of 2 district branches to include “physicians” (Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association and Missouri Psychiatric Physicians Association). If elected, I will propose to the Board of Trustees and the APA members that we change our name to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, which will emphasize our medical identity within mental health. In its 175-year history, the APA has experienced 2 previous name changes.

I believe the strengths of the APA far exceed its weaknesses, and its opportunities outnumber its threats. However, the following perennial challenges must be forcefully addressed by all of us:

- The pernicious and discriminatory dogma of stigma must be shattered for the sake of patients, their families, their psychiatrists, and the profession.

- Pre-authorization is essentially the insurance companies practicing medicine without a license when, without ever actually examining the patient, they tell physicians what they should or should not prescribe. That’s felonious!

- Competent and safe prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training (approximately 14,000 hours) and psychologists do not qualify.

- Board certification fees must be reduced, and recertification (Maintenance of Certification) must be simpler and less onerous.

- Effective parity laws must have teeth, not just words!

- Patient care, not computer care! Electronic health records must be more user-friendly and less time-consuming.

- Patients with psychiatric illness who have relapsed must be surrounded by compassionate medical professionals in a hospital setting, not by armed guards in a jail or prison.