User login

Hospitalist-Specific Data Shows Rise in Use of Some CPT Codes

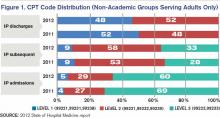

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Lack of Medicare CPT Codes for Hospitalist Practice Creates Dilemma

Hospitalist leaders are taking a proactive approach to the latest wrinkle of the specialty’s rock-and-a-hard-place dilemma when it comes to how clinicians code for their services. The oft-lamented issue is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) dearth of CPT codes designated for day-to-day hospitalist services.

But the latest twist to the story is what happens in skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs). Hospitalists increasingly are taking lead roles in SNFs, yet they must use the same care codes as nursing-home providers despite the higher acuity and longer length of stay found in SNFs compared to nursing homes. Additionally, Medicare recognizes SNFs and nursing homes as primary care for reimbursement via accountable-care organizations (ACOs).

Kerry Weiner, MD, a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says SHM and others, including the American Medical Directors Association, are pushing CMS to reclassify SNF care as inpatient service, similar to acute rehabilitation facilities, inpatient psychiatric care, and long-term acute-care facilities. Dr. Weiner suggests rank-and-file practitioners do the same.

“We think attributing providers to be primary care versus specialty care versus acute care only on the basis of E&M codes will not really capture the nuances of primary-care practice in the country right now,” says Dr. Weiner, chief medical officer at North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company. “This is an example of how just using E&M codes does not really capture the style of practice and the type of patient you’re seeing.”

The arguments for reclassification include:

- Hospitalists and other physicians practicing in SNFs need to spend most of their time there to provide optimal care, but it is difficult to financially justify maintaining that presence without an adequate patient census.

- Generating that census while practicing in one ACO is difficult because most facilities service multiple ACOs, and PCP exclusivity rules tied to many ACO contracts are a hurdle for physicians working with one just ACO (working with multiple ACOs requires multiple tax identification numbers and can be “operationally and politically difficult,” Dr. Wiener says).

- All told, ACO setup creates a fiscal hurdle for providers working in SNFs and does not recognize the clinical burden that separates the types of care provided in SNFs and nursing homes. Were care in SNFs reclassified as inpatient care, the exclusivity rule would not apply, and therefore, hospitalists in those facilities could more easily attain a patient census that justifies their continued presence. Dr. Weiner says one solution is to create a set of CPT codes just for SNFs that could be used by specialist physicians, including hospitalists.

“We are proposing a ‘work around’ by using the site of service as a determinator,” he adds.

Issues to Address

Dr. Weiner, SHM officials, and others have met with CMS to discuss the potential reclassification. Dr. Weiner says that as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) morphs into the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, the issue of ACO exclusivity could become even more prevalent as compensation is tied to performance.

“One of the components of physician value-based purchasing is the cost of care,” Dr. Weiner says. “If you compare a hospitalist’s cost to the pool of primary care, which includes hospitals, SNFs, etc., you’re obviously going to be higher because you have a much sicker population; A lot more things are going on, so there’s a lot higher utilization. So this concept of assigning doctors to a style of practice just based on E&M codes is just inadequate.”

Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer of CMS and director of CMS’ Center of Clinical Standards and Quality, says the agency is sympathetic to the issue. Via PQRS and VBPM, CMS is working to put in place “a robust set of measures that hospitalists can choose to report on,” he says.

“CMS has sought public comment on allowing hospitalists to align with their hospital’s quality measures for CMS quality programs,” he says. “But without this alignment option or a specialty code, we need to at least have sufficient measures to reflect hospitalists’ actual practice and what’s important to hospital medicine.”

Dr. Conway, a former hospitalist and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says he welcomes feedback from SHM and its members on suggested changes to CMS policy.

“I would certainly encourage hospital medicine to have discussions with the CMS payment and coding team that makes determinations about specialty status,” he says.

The Future?

Ironically, the potential panacea of HM-specific codes has not been fully embraced because of fears of unintended consequences. For example, in the case of hospitalists practicing in SNFs, the PCP designation is problematic in terms of lower reimbursement rates. Some hospitalists, however, will see a bump in total revenue the next two years because they will be designated PCPs and paid more via the Medicaid-to-Medicare parity regulation included in the Affordable Care Act.

“Hospital medicine will want to think about that as it goes through the process,” Dr. Conway says. “Internally with CMS, if you’re a specialty, we will specifically consider if you’re primary care or not. Whereas, if you’re in the internal-medicine bucket, by definition from the traditional CMS specialty coding perspective, you are primary care. So if you make a point to carve out your own category, then it’ll be a decision every time if you’re primary care or are you a specialty.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Hospitalist leaders are taking a proactive approach to the latest wrinkle of the specialty’s rock-and-a-hard-place dilemma when it comes to how clinicians code for their services. The oft-lamented issue is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) dearth of CPT codes designated for day-to-day hospitalist services.

But the latest twist to the story is what happens in skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs). Hospitalists increasingly are taking lead roles in SNFs, yet they must use the same care codes as nursing-home providers despite the higher acuity and longer length of stay found in SNFs compared to nursing homes. Additionally, Medicare recognizes SNFs and nursing homes as primary care for reimbursement via accountable-care organizations (ACOs).

Kerry Weiner, MD, a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says SHM and others, including the American Medical Directors Association, are pushing CMS to reclassify SNF care as inpatient service, similar to acute rehabilitation facilities, inpatient psychiatric care, and long-term acute-care facilities. Dr. Weiner suggests rank-and-file practitioners do the same.

“We think attributing providers to be primary care versus specialty care versus acute care only on the basis of E&M codes will not really capture the nuances of primary-care practice in the country right now,” says Dr. Weiner, chief medical officer at North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company. “This is an example of how just using E&M codes does not really capture the style of practice and the type of patient you’re seeing.”

The arguments for reclassification include:

- Hospitalists and other physicians practicing in SNFs need to spend most of their time there to provide optimal care, but it is difficult to financially justify maintaining that presence without an adequate patient census.

- Generating that census while practicing in one ACO is difficult because most facilities service multiple ACOs, and PCP exclusivity rules tied to many ACO contracts are a hurdle for physicians working with one just ACO (working with multiple ACOs requires multiple tax identification numbers and can be “operationally and politically difficult,” Dr. Wiener says).

- All told, ACO setup creates a fiscal hurdle for providers working in SNFs and does not recognize the clinical burden that separates the types of care provided in SNFs and nursing homes. Were care in SNFs reclassified as inpatient care, the exclusivity rule would not apply, and therefore, hospitalists in those facilities could more easily attain a patient census that justifies their continued presence. Dr. Weiner says one solution is to create a set of CPT codes just for SNFs that could be used by specialist physicians, including hospitalists.

“We are proposing a ‘work around’ by using the site of service as a determinator,” he adds.

Issues to Address

Dr. Weiner, SHM officials, and others have met with CMS to discuss the potential reclassification. Dr. Weiner says that as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) morphs into the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, the issue of ACO exclusivity could become even more prevalent as compensation is tied to performance.

“One of the components of physician value-based purchasing is the cost of care,” Dr. Weiner says. “If you compare a hospitalist’s cost to the pool of primary care, which includes hospitals, SNFs, etc., you’re obviously going to be higher because you have a much sicker population; A lot more things are going on, so there’s a lot higher utilization. So this concept of assigning doctors to a style of practice just based on E&M codes is just inadequate.”

Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer of CMS and director of CMS’ Center of Clinical Standards and Quality, says the agency is sympathetic to the issue. Via PQRS and VBPM, CMS is working to put in place “a robust set of measures that hospitalists can choose to report on,” he says.

“CMS has sought public comment on allowing hospitalists to align with their hospital’s quality measures for CMS quality programs,” he says. “But without this alignment option or a specialty code, we need to at least have sufficient measures to reflect hospitalists’ actual practice and what’s important to hospital medicine.”

Dr. Conway, a former hospitalist and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says he welcomes feedback from SHM and its members on suggested changes to CMS policy.

“I would certainly encourage hospital medicine to have discussions with the CMS payment and coding team that makes determinations about specialty status,” he says.

The Future?

Ironically, the potential panacea of HM-specific codes has not been fully embraced because of fears of unintended consequences. For example, in the case of hospitalists practicing in SNFs, the PCP designation is problematic in terms of lower reimbursement rates. Some hospitalists, however, will see a bump in total revenue the next two years because they will be designated PCPs and paid more via the Medicaid-to-Medicare parity regulation included in the Affordable Care Act.

“Hospital medicine will want to think about that as it goes through the process,” Dr. Conway says. “Internally with CMS, if you’re a specialty, we will specifically consider if you’re primary care or not. Whereas, if you’re in the internal-medicine bucket, by definition from the traditional CMS specialty coding perspective, you are primary care. So if you make a point to carve out your own category, then it’ll be a decision every time if you’re primary care or are you a specialty.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Hospitalist leaders are taking a proactive approach to the latest wrinkle of the specialty’s rock-and-a-hard-place dilemma when it comes to how clinicians code for their services. The oft-lamented issue is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) dearth of CPT codes designated for day-to-day hospitalist services.

But the latest twist to the story is what happens in skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs). Hospitalists increasingly are taking lead roles in SNFs, yet they must use the same care codes as nursing-home providers despite the higher acuity and longer length of stay found in SNFs compared to nursing homes. Additionally, Medicare recognizes SNFs and nursing homes as primary care for reimbursement via accountable-care organizations (ACOs).

Kerry Weiner, MD, a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says SHM and others, including the American Medical Directors Association, are pushing CMS to reclassify SNF care as inpatient service, similar to acute rehabilitation facilities, inpatient psychiatric care, and long-term acute-care facilities. Dr. Weiner suggests rank-and-file practitioners do the same.

“We think attributing providers to be primary care versus specialty care versus acute care only on the basis of E&M codes will not really capture the nuances of primary-care practice in the country right now,” says Dr. Weiner, chief medical officer at North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company. “This is an example of how just using E&M codes does not really capture the style of practice and the type of patient you’re seeing.”

The arguments for reclassification include:

- Hospitalists and other physicians practicing in SNFs need to spend most of their time there to provide optimal care, but it is difficult to financially justify maintaining that presence without an adequate patient census.

- Generating that census while practicing in one ACO is difficult because most facilities service multiple ACOs, and PCP exclusivity rules tied to many ACO contracts are a hurdle for physicians working with one just ACO (working with multiple ACOs requires multiple tax identification numbers and can be “operationally and politically difficult,” Dr. Wiener says).

- All told, ACO setup creates a fiscal hurdle for providers working in SNFs and does not recognize the clinical burden that separates the types of care provided in SNFs and nursing homes. Were care in SNFs reclassified as inpatient care, the exclusivity rule would not apply, and therefore, hospitalists in those facilities could more easily attain a patient census that justifies their continued presence. Dr. Weiner says one solution is to create a set of CPT codes just for SNFs that could be used by specialist physicians, including hospitalists.

“We are proposing a ‘work around’ by using the site of service as a determinator,” he adds.

Issues to Address

Dr. Weiner, SHM officials, and others have met with CMS to discuss the potential reclassification. Dr. Weiner says that as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) morphs into the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, the issue of ACO exclusivity could become even more prevalent as compensation is tied to performance.

“One of the components of physician value-based purchasing is the cost of care,” Dr. Weiner says. “If you compare a hospitalist’s cost to the pool of primary care, which includes hospitals, SNFs, etc., you’re obviously going to be higher because you have a much sicker population; A lot more things are going on, so there’s a lot higher utilization. So this concept of assigning doctors to a style of practice just based on E&M codes is just inadequate.”

Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer of CMS and director of CMS’ Center of Clinical Standards and Quality, says the agency is sympathetic to the issue. Via PQRS and VBPM, CMS is working to put in place “a robust set of measures that hospitalists can choose to report on,” he says.

“CMS has sought public comment on allowing hospitalists to align with their hospital’s quality measures for CMS quality programs,” he says. “But without this alignment option or a specialty code, we need to at least have sufficient measures to reflect hospitalists’ actual practice and what’s important to hospital medicine.”

Dr. Conway, a former hospitalist and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says he welcomes feedback from SHM and its members on suggested changes to CMS policy.

“I would certainly encourage hospital medicine to have discussions with the CMS payment and coding team that makes determinations about specialty status,” he says.

The Future?

Ironically, the potential panacea of HM-specific codes has not been fully embraced because of fears of unintended consequences. For example, in the case of hospitalists practicing in SNFs, the PCP designation is problematic in terms of lower reimbursement rates. Some hospitalists, however, will see a bump in total revenue the next two years because they will be designated PCPs and paid more via the Medicaid-to-Medicare parity regulation included in the Affordable Care Act.

“Hospital medicine will want to think about that as it goes through the process,” Dr. Conway says. “Internally with CMS, if you’re a specialty, we will specifically consider if you’re primary care or not. Whereas, if you’re in the internal-medicine bucket, by definition from the traditional CMS specialty coding perspective, you are primary care. So if you make a point to carve out your own category, then it’ll be a decision every time if you’re primary care or are you a specialty.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Medicare Outlines Anticipated Funding Changes Under Affordable Care Act

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released a few Fact Sheets on how they anticipate funding changes on a few of their programs that were implemented (or sustained) under the Affordable Care Act. As a background, CMS pays most acute-care hospitals by prospectively determining payment based on a patient’s diagnosis and the severity of illness within that diagnosis (e.g. “MS-DRG”). These payment amounts are updated annually after evaluating several factors, including the costs associated with the delivery of care.

One of the most major changes described in the Fact Sheet that will affect hospitalists is how CMS will review inpatient stays based on the number of nights in the hospital. CMS has proposed that any patient who stays in the hospital for two or more “midnights” should be appropriate for payment under Medicare Part A. For those who stay in the hospital for only one (or zero) midnights, payment under Medicare Part A will only be appropriate if:

- There is sufficient documentation at the time of admission that the anticipated length of stay is two or more nights; and.

- Further documentation that circumstances changed, and the hospital stay ended prematurely because of those changes.

Overall for hospitalists, this should substantially simplify the admitting process, whereby most inpatients being admitted with the anticipation of two or more nights should qualify for an inpatient stay. This also reduces the administrative burden of correcting the “inpatient” versus “observation” designation, which keeps many hospital staffs entirely too busy. This change also should relieve a significant burden from the patients and their families, who if kept in observation for a period of time, may have to pay substantially out of pocket to make up for the difference between the cost of the stay and the reimbursement from CMS for observation status. So this is one of the moves that CMS is making to simplify (and not complicate) an already too-complicated payment system. This should go into effect October 2013 and will be a sigh of much relief from many of us.

A few other anticipated changes that will affect hospitalists include:

Payments for Unfunded Care

Another major change that will go into affect October 2013 is the amount of monies received by hospitals that care for unfunded patients. These payments historically have been made to “Disproportionate Share Hospitals” (DSH), which are hospitals that care for a higher percentage of unfunded patients. Under the Affordable Care Act, only 25% of these payments will be distributed to DSH hospitals; the remaining 75% will be reduced based on the number of uninsured in the U.S., then redistributed to DSH hospitals based on their portion of uninsured care delivered.

Most DSH hospitals should expect a decrease in DSH payments, the amount of which will depend on their share of unfunded patients.

Any reduction in the “bottom line” to the hospital can affect hospitalists, especially those who are directly employed by the hospital.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

CMS has long had the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) program in effect, which has the ability to reduce the amount of payment for inpatients who acquire a HAC during their hospital stay. Starting in October 2014, CMS will impose additional financial penalties for hospitals with high HAC rates.

Specifically, those hospitals in the highest 25th percentile of HAC rates will be penalized 1% of their overall CMS payments. Another proposed change is that the following be included in the HAC reduction plan (two “domains” of measures):

- Domain No. 1: Six of the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), including pressure ulcers, foreign bodies left in after surgery, iatrogenic pneumothorax, postoperative physiologic or metabolic derangements, postoperative VTE, and accidental puncture/laceration.

- Domain No. 2: Central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The domains will be weighted equally, and an average score will determine the total score. There will be some methodology for risk adjustment, and hospitals will be given a review and comment period to validate their own scores.

Most hospitalists have at least indirect control over many of these HACs,and all need to pay very close attention to their hospital’s rates of these now and in the future.

Readmissions

As we all know, the Hospital Readmission Reduction program went into effect October 2012; it placed 1% of CMS payments at risk. This will increase to 2% of payments as of October 2013. CMS will continue to use AMI, CHF, and pneumonia as the three conditions under which the readmissions are measured but will put in some methodology to account for planned readmissions.

In addition, in October 2014, they plan to add readmission rates for COPD and for hip/knee arthroplasty.

Hospitalists will continue to need to progress their transitions of care programs, at least for these five patients conditions but more likely (and more effectively) for all hospital discharges.

Quality Measures

Currently more than 99% of acute-care hospitals participate in the pay-for-reporting quality program through CMS, the results of which have been displayed on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) for years. The program started in 2004 with 10 quality metrics and now includes 57 metrics. These include process and outcome measures for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia, as well as process measures for surgical care, HACs, and patient-satisfaction surveys, among others.

This program will continue to expand over time, including hospital-acquired MRSA and Clostridium difficile rates. The few hospitals not participating will have their CMS annual payments reduced by 2%.

EHR Incentives

CMS is evaluating ways to reduce the burden of reporting by aligning EHR incentives with the Inpatient Quality Reporting program.

Summary

After an open commentary period, the Final Rule will be published Aug. 1, and will become effective for discharges on or after Oct. 1. Although CMS will continue to expand the total number of measures that need to be reported, and the penalties for non-reporting or low performance will continue to escalate, CMS is at least attempting to reduce the overall burden of reporting by combining measures and programs over time and using EHRs to facilitate the bulk of reporting over time.

The global message to hospitalists is: Continue to focus on reducing the burden of HACs, enhance throughput, and carefully and thoughtfully transition patients to the next provider after their hospital discharge. All in all, although at times this can feel overwhelming, these changes represent the right direction to move for high-quality and safe patient care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released a few Fact Sheets on how they anticipate funding changes on a few of their programs that were implemented (or sustained) under the Affordable Care Act. As a background, CMS pays most acute-care hospitals by prospectively determining payment based on a patient’s diagnosis and the severity of illness within that diagnosis (e.g. “MS-DRG”). These payment amounts are updated annually after evaluating several factors, including the costs associated with the delivery of care.

One of the most major changes described in the Fact Sheet that will affect hospitalists is how CMS will review inpatient stays based on the number of nights in the hospital. CMS has proposed that any patient who stays in the hospital for two or more “midnights” should be appropriate for payment under Medicare Part A. For those who stay in the hospital for only one (or zero) midnights, payment under Medicare Part A will only be appropriate if:

- There is sufficient documentation at the time of admission that the anticipated length of stay is two or more nights; and.

- Further documentation that circumstances changed, and the hospital stay ended prematurely because of those changes.

Overall for hospitalists, this should substantially simplify the admitting process, whereby most inpatients being admitted with the anticipation of two or more nights should qualify for an inpatient stay. This also reduces the administrative burden of correcting the “inpatient” versus “observation” designation, which keeps many hospital staffs entirely too busy. This change also should relieve a significant burden from the patients and their families, who if kept in observation for a period of time, may have to pay substantially out of pocket to make up for the difference between the cost of the stay and the reimbursement from CMS for observation status. So this is one of the moves that CMS is making to simplify (and not complicate) an already too-complicated payment system. This should go into effect October 2013 and will be a sigh of much relief from many of us.

A few other anticipated changes that will affect hospitalists include:

Payments for Unfunded Care

Another major change that will go into affect October 2013 is the amount of monies received by hospitals that care for unfunded patients. These payments historically have been made to “Disproportionate Share Hospitals” (DSH), which are hospitals that care for a higher percentage of unfunded patients. Under the Affordable Care Act, only 25% of these payments will be distributed to DSH hospitals; the remaining 75% will be reduced based on the number of uninsured in the U.S., then redistributed to DSH hospitals based on their portion of uninsured care delivered.

Most DSH hospitals should expect a decrease in DSH payments, the amount of which will depend on their share of unfunded patients.

Any reduction in the “bottom line” to the hospital can affect hospitalists, especially those who are directly employed by the hospital.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

CMS has long had the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) program in effect, which has the ability to reduce the amount of payment for inpatients who acquire a HAC during their hospital stay. Starting in October 2014, CMS will impose additional financial penalties for hospitals with high HAC rates.

Specifically, those hospitals in the highest 25th percentile of HAC rates will be penalized 1% of their overall CMS payments. Another proposed change is that the following be included in the HAC reduction plan (two “domains” of measures):

- Domain No. 1: Six of the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), including pressure ulcers, foreign bodies left in after surgery, iatrogenic pneumothorax, postoperative physiologic or metabolic derangements, postoperative VTE, and accidental puncture/laceration.

- Domain No. 2: Central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The domains will be weighted equally, and an average score will determine the total score. There will be some methodology for risk adjustment, and hospitals will be given a review and comment period to validate their own scores.

Most hospitalists have at least indirect control over many of these HACs,and all need to pay very close attention to their hospital’s rates of these now and in the future.

Readmissions

As we all know, the Hospital Readmission Reduction program went into effect October 2012; it placed 1% of CMS payments at risk. This will increase to 2% of payments as of October 2013. CMS will continue to use AMI, CHF, and pneumonia as the three conditions under which the readmissions are measured but will put in some methodology to account for planned readmissions.

In addition, in October 2014, they plan to add readmission rates for COPD and for hip/knee arthroplasty.

Hospitalists will continue to need to progress their transitions of care programs, at least for these five patients conditions but more likely (and more effectively) for all hospital discharges.

Quality Measures

Currently more than 99% of acute-care hospitals participate in the pay-for-reporting quality program through CMS, the results of which have been displayed on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) for years. The program started in 2004 with 10 quality metrics and now includes 57 metrics. These include process and outcome measures for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia, as well as process measures for surgical care, HACs, and patient-satisfaction surveys, among others.

This program will continue to expand over time, including hospital-acquired MRSA and Clostridium difficile rates. The few hospitals not participating will have their CMS annual payments reduced by 2%.

EHR Incentives

CMS is evaluating ways to reduce the burden of reporting by aligning EHR incentives with the Inpatient Quality Reporting program.

Summary

After an open commentary period, the Final Rule will be published Aug. 1, and will become effective for discharges on or after Oct. 1. Although CMS will continue to expand the total number of measures that need to be reported, and the penalties for non-reporting or low performance will continue to escalate, CMS is at least attempting to reduce the overall burden of reporting by combining measures and programs over time and using EHRs to facilitate the bulk of reporting over time.

The global message to hospitalists is: Continue to focus on reducing the burden of HACs, enhance throughput, and carefully and thoughtfully transition patients to the next provider after their hospital discharge. All in all, although at times this can feel overwhelming, these changes represent the right direction to move for high-quality and safe patient care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently released a few Fact Sheets on how they anticipate funding changes on a few of their programs that were implemented (or sustained) under the Affordable Care Act. As a background, CMS pays most acute-care hospitals by prospectively determining payment based on a patient’s diagnosis and the severity of illness within that diagnosis (e.g. “MS-DRG”). These payment amounts are updated annually after evaluating several factors, including the costs associated with the delivery of care.

One of the most major changes described in the Fact Sheet that will affect hospitalists is how CMS will review inpatient stays based on the number of nights in the hospital. CMS has proposed that any patient who stays in the hospital for two or more “midnights” should be appropriate for payment under Medicare Part A. For those who stay in the hospital for only one (or zero) midnights, payment under Medicare Part A will only be appropriate if:

- There is sufficient documentation at the time of admission that the anticipated length of stay is two or more nights; and.

- Further documentation that circumstances changed, and the hospital stay ended prematurely because of those changes.

Overall for hospitalists, this should substantially simplify the admitting process, whereby most inpatients being admitted with the anticipation of two or more nights should qualify for an inpatient stay. This also reduces the administrative burden of correcting the “inpatient” versus “observation” designation, which keeps many hospital staffs entirely too busy. This change also should relieve a significant burden from the patients and their families, who if kept in observation for a period of time, may have to pay substantially out of pocket to make up for the difference between the cost of the stay and the reimbursement from CMS for observation status. So this is one of the moves that CMS is making to simplify (and not complicate) an already too-complicated payment system. This should go into effect October 2013 and will be a sigh of much relief from many of us.

A few other anticipated changes that will affect hospitalists include:

Payments for Unfunded Care

Another major change that will go into affect October 2013 is the amount of monies received by hospitals that care for unfunded patients. These payments historically have been made to “Disproportionate Share Hospitals” (DSH), which are hospitals that care for a higher percentage of unfunded patients. Under the Affordable Care Act, only 25% of these payments will be distributed to DSH hospitals; the remaining 75% will be reduced based on the number of uninsured in the U.S., then redistributed to DSH hospitals based on their portion of uninsured care delivered.

Most DSH hospitals should expect a decrease in DSH payments, the amount of which will depend on their share of unfunded patients.

Any reduction in the “bottom line” to the hospital can affect hospitalists, especially those who are directly employed by the hospital.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

CMS has long had the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) program in effect, which has the ability to reduce the amount of payment for inpatients who acquire a HAC during their hospital stay. Starting in October 2014, CMS will impose additional financial penalties for hospitals with high HAC rates.

Specifically, those hospitals in the highest 25th percentile of HAC rates will be penalized 1% of their overall CMS payments. Another proposed change is that the following be included in the HAC reduction plan (two “domains” of measures):

- Domain No. 1: Six of the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), including pressure ulcers, foreign bodies left in after surgery, iatrogenic pneumothorax, postoperative physiologic or metabolic derangements, postoperative VTE, and accidental puncture/laceration.

- Domain No. 2: Central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The domains will be weighted equally, and an average score will determine the total score. There will be some methodology for risk adjustment, and hospitals will be given a review and comment period to validate their own scores.

Most hospitalists have at least indirect control over many of these HACs,and all need to pay very close attention to their hospital’s rates of these now and in the future.

Readmissions

As we all know, the Hospital Readmission Reduction program went into effect October 2012; it placed 1% of CMS payments at risk. This will increase to 2% of payments as of October 2013. CMS will continue to use AMI, CHF, and pneumonia as the three conditions under which the readmissions are measured but will put in some methodology to account for planned readmissions.

In addition, in October 2014, they plan to add readmission rates for COPD and for hip/knee arthroplasty.

Hospitalists will continue to need to progress their transitions of care programs, at least for these five patients conditions but more likely (and more effectively) for all hospital discharges.

Quality Measures

Currently more than 99% of acute-care hospitals participate in the pay-for-reporting quality program through CMS, the results of which have been displayed on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) for years. The program started in 2004 with 10 quality metrics and now includes 57 metrics. These include process and outcome measures for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia, as well as process measures for surgical care, HACs, and patient-satisfaction surveys, among others.

This program will continue to expand over time, including hospital-acquired MRSA and Clostridium difficile rates. The few hospitals not participating will have their CMS annual payments reduced by 2%.

EHR Incentives

CMS is evaluating ways to reduce the burden of reporting by aligning EHR incentives with the Inpatient Quality Reporting program.

Summary

After an open commentary period, the Final Rule will be published Aug. 1, and will become effective for discharges on or after Oct. 1. Although CMS will continue to expand the total number of measures that need to be reported, and the penalties for non-reporting or low performance will continue to escalate, CMS is at least attempting to reduce the overall burden of reporting by combining measures and programs over time and using EHRs to facilitate the bulk of reporting over time.

The global message to hospitalists is: Continue to focus on reducing the burden of HACs, enhance throughput, and carefully and thoughtfully transition patients to the next provider after their hospital discharge. All in all, although at times this can feel overwhelming, these changes represent the right direction to move for high-quality and safe patient care.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

Should Skyrocketing Health Care Costs Concern Hospitalists?

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Advanced-Practice Providers Have More to Offer Hospital Medicine Groups

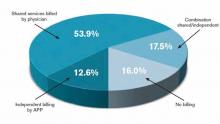

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Advanced-practice providers (APPs) continue to make their presence felt in the world of hospital medicine. According to survey data from the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report, more than half (53.9%) of respondent groups serving adults have nurse practitioners (NP) and/or physician assistants (PA) integrated into their practices. The median ratio of APPs to hospitalist physicians in these groups has remained about the same as in previous surveys, with respondents reporting 0.2 FTE NPs per FTE physician, and 0.1 FTE PAs per FTE physician. We’ve also learned that APPs tend to be stable members of most hospitalist practices, with more than 70% of groups reporting no turnover among their APPs during the survey period.

Unfortunately, we don’t yet have much information on the specific roles APPs are filling in HM practices; hopefully, this will be a subject for the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, scheduled to launch in January 2014.

The 2012 survey did provide new information about how APP work is billed by HM groups. More than half the time, APP work is billed as a shared service under a physician’s provider number (see Table 1). Only on rare occasions is APP work billed separately under the APP’s provider number.

Perhaps most surprising of all, 16% of adult HM groups with APPs reported that their APPs don’t generally provide billable services, or no charges were submitted to payors for their services. This figure rose to 23% for hospital-employed groups.

Almost everywhere I go in my consulting work, we are asked about the value APPs can provide to hospitalist practice, and what their optimal roles are. I am extremely supportive of integrating APPs into hospitalist practice and believe they can play valuable roles supporting both excellent patient care and overall group efficiency.

But in my experience, many HM groups fail to execute well on this promise. As the survey results suggest, sometimes APPs are relegated to nonbillable tasks that could be performed by individuals at a lower skill level. Sometimes the hospitalists tend to think of the APPs as “free” help, and no real attempt is made to account for their contribution or capture their billable work. And some groups are so focused on ensuring they capture the 100% reimbursement available by billing under the physician’s name (rather than the 85% reimbursement typically available to APPs) that they lose sight of the fact that the extra physician time and effort involved might cost more than the incremental additional reimbursement received.

As a specialty, we still have a lot to learn about the optimal ways to deploy APPs to support high-quality, effective hospitalist practice. In the meantime, it can be valuable for HM groups to ensure that APPs are functioning in roles that take advantage of their advanced skills and licensure scope, and that efforts are being made to ensure the capture of all billable services provided.

I hope you will plan to participate in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey and share your own practice’s experience with APPs.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Effective Clinical Documentation Can Influence Medicare Reimbursement

Back in the 1980s, I would go by medical records every day or two and find, on the front of the charts of my recently discharged patients, a form listing the diagnoses the hospital was billing to Medicare. Before the hospital could submit a patient’s bill, the attending physician was required to review the form and, by signing it, indicate agreement.

The requirement for this signature by the physician went away a long time ago and in my memory is one of the very few examples of reducing a doctor’s paperwork.

For my first few months in practice, I regularly would seek out the people who completed the form and explain they had misunderstood the patient’s clinical situation. “The main issue was a urinary tract infection,” I would say, “but you listed diabetes as the principal diagnosis.”

I don’t ever remember them changing anything based on my feedback. Instead, they explained to me that, for billing purposes, it was legitimate to list diabetes as the principal diagnosis because it had the additional benefit of resulting in a higher payment to the hospital than having “urinary tract infection” listed first.

Such was my introduction to the world of documentation and coding for hospital billing purposes and how it can sometimes differ significantly from the way a doctor sees the clinical picture. Things have evolved a lot since then, but the way doctors document medical conditions still has a huge influence on hospital reimbursement.

Hospital CDI Programs

About 80% of hospitals have formal clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs to help ensure all clinical conditions are captured and described in the medical record in ways that are valuable for billing and other recordkeeping purposes. These programs might lead to you receive queries about your documentation. For example, you might be asked to clarify whether your patient’s pneumonia might be on the basis of aspiration.

Within SHM’s Code-H program, Dr. Richard Pinson, a former ED physician who now works with Houston-based HCQ Consulting, has a good presentation explaining these documentation issues. In it, he makes the point that, in addition to influencing how hospitals are paid, the way various conditions are documented also influences quality ratings.

Novel Approach

The most common approach to engaging hospitalists in CDI initiatives is to have them attend a presentation on the topic, then put in place documentation specialists who generate queries asking the doctor to clarify diagnoses when it might influence payment, severity of illness determination, etc. Dr. Kenji Asakura, a Seattle hospitalist, and Erik Ordal, MBA, have a company called ClinIntell that analyzes each hospitalist (or other specialty) group’s historical patient mix and trains them on the documentation issues that they see most often. The idea of this focused approach is to make “documentation queries” unnecessary, or at least much less necessary. The benefits of this approach are many, including reducing or eliminating the risk of “leading queries”—that is, queries that seem to encourage the doctor to document a diagnosis because it is an advantage to the hospital rather than a well-considered medical opinion. Leading queries can be regarded as fraudulent and can get a lot of people in trouble.

I asked Kenji and Erik if they could provide me with a list of common documentation issues that most hospitalists need to know more about. Table 1 is what they came up with. I hope it helps you and your practice.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at [email protected].

Back in the 1980s, I would go by medical records every day or two and find, on the front of the charts of my recently discharged patients, a form listing the diagnoses the hospital was billing to Medicare. Before the hospital could submit a patient’s bill, the attending physician was required to review the form and, by signing it, indicate agreement.

The requirement for this signature by the physician went away a long time ago and in my memory is one of the very few examples of reducing a doctor’s paperwork.

For my first few months in practice, I regularly would seek out the people who completed the form and explain they had misunderstood the patient’s clinical situation. “The main issue was a urinary tract infection,” I would say, “but you listed diabetes as the principal diagnosis.”

I don’t ever remember them changing anything based on my feedback. Instead, they explained to me that, for billing purposes, it was legitimate to list diabetes as the principal diagnosis because it had the additional benefit of resulting in a higher payment to the hospital than having “urinary tract infection” listed first.

Such was my introduction to the world of documentation and coding for hospital billing purposes and how it can sometimes differ significantly from the way a doctor sees the clinical picture. Things have evolved a lot since then, but the way doctors document medical conditions still has a huge influence on hospital reimbursement.

Hospital CDI Programs

About 80% of hospitals have formal clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs to help ensure all clinical conditions are captured and described in the medical record in ways that are valuable for billing and other recordkeeping purposes. These programs might lead to you receive queries about your documentation. For example, you might be asked to clarify whether your patient’s pneumonia might be on the basis of aspiration.

Within SHM’s Code-H program, Dr. Richard Pinson, a former ED physician who now works with Houston-based HCQ Consulting, has a good presentation explaining these documentation issues. In it, he makes the point that, in addition to influencing how hospitals are paid, the way various conditions are documented also influences quality ratings.

Novel Approach

The most common approach to engaging hospitalists in CDI initiatives is to have them attend a presentation on the topic, then put in place documentation specialists who generate queries asking the doctor to clarify diagnoses when it might influence payment, severity of illness determination, etc. Dr. Kenji Asakura, a Seattle hospitalist, and Erik Ordal, MBA, have a company called ClinIntell that analyzes each hospitalist (or other specialty) group’s historical patient mix and trains them on the documentation issues that they see most often. The idea of this focused approach is to make “documentation queries” unnecessary, or at least much less necessary. The benefits of this approach are many, including reducing or eliminating the risk of “leading queries”—that is, queries that seem to encourage the doctor to document a diagnosis because it is an advantage to the hospital rather than a well-considered medical opinion. Leading queries can be regarded as fraudulent and can get a lot of people in trouble.

I asked Kenji and Erik if they could provide me with a list of common documentation issues that most hospitalists need to know more about. Table 1 is what they came up with. I hope it helps you and your practice.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at [email protected].

Back in the 1980s, I would go by medical records every day or two and find, on the front of the charts of my recently discharged patients, a form listing the diagnoses the hospital was billing to Medicare. Before the hospital could submit a patient’s bill, the attending physician was required to review the form and, by signing it, indicate agreement.

The requirement for this signature by the physician went away a long time ago and in my memory is one of the very few examples of reducing a doctor’s paperwork.

For my first few months in practice, I regularly would seek out the people who completed the form and explain they had misunderstood the patient’s clinical situation. “The main issue was a urinary tract infection,” I would say, “but you listed diabetes as the principal diagnosis.”

I don’t ever remember them changing anything based on my feedback. Instead, they explained to me that, for billing purposes, it was legitimate to list diabetes as the principal diagnosis because it had the additional benefit of resulting in a higher payment to the hospital than having “urinary tract infection” listed first.

Such was my introduction to the world of documentation and coding for hospital billing purposes and how it can sometimes differ significantly from the way a doctor sees the clinical picture. Things have evolved a lot since then, but the way doctors document medical conditions still has a huge influence on hospital reimbursement.

Hospital CDI Programs

About 80% of hospitals have formal clinical documentation improvement (CDI) programs to help ensure all clinical conditions are captured and described in the medical record in ways that are valuable for billing and other recordkeeping purposes. These programs might lead to you receive queries about your documentation. For example, you might be asked to clarify whether your patient’s pneumonia might be on the basis of aspiration.

Within SHM’s Code-H program, Dr. Richard Pinson, a former ED physician who now works with Houston-based HCQ Consulting, has a good presentation explaining these documentation issues. In it, he makes the point that, in addition to influencing how hospitals are paid, the way various conditions are documented also influences quality ratings.

Novel Approach

The most common approach to engaging hospitalists in CDI initiatives is to have them attend a presentation on the topic, then put in place documentation specialists who generate queries asking the doctor to clarify diagnoses when it might influence payment, severity of illness determination, etc. Dr. Kenji Asakura, a Seattle hospitalist, and Erik Ordal, MBA, have a company called ClinIntell that analyzes each hospitalist (or other specialty) group’s historical patient mix and trains them on the documentation issues that they see most often. The idea of this focused approach is to make “documentation queries” unnecessary, or at least much less necessary. The benefits of this approach are many, including reducing or eliminating the risk of “leading queries”—that is, queries that seem to encourage the doctor to document a diagnosis because it is an advantage to the hospital rather than a well-considered medical opinion. Leading queries can be regarded as fraudulent and can get a lot of people in trouble.

I asked Kenji and Erik if they could provide me with a list of common documentation issues that most hospitalists need to know more about. Table 1 is what they came up with. I hope it helps you and your practice.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at [email protected].

'Systems,' Not 'Points,' Is Correct Terminology for ROS Statements

The “Billing and Coding Bandwagon” article in the May 2011 issue of The Hospitalist (p. 26) recently was brought to my attention and I have some concerns that the following statement gives a false impression of acceptable documentation: “When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”

In fact, that would still not be considered acceptable documentation for services that require a complete review of systems (99222, 99223, 99219, 99220, 99235, and 99236). The documentation guidelines clearly state: “A complete ROS [review of systems] inquires about the system(s) directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI plus all additional body systems.” At least 10 organ systems must be reviewed. Those systems with positive or pertinent negative responses must be individually documented. For the remaining systems, a notation indicating all other systems are negative is permissible. In the absence of such a notation, at least 10 systems must be individually documented.

What Medicare is saying is the provider must have inquired about all 14 systems, not just 10 or 12. The term “point” means nothing in an ROS statement. “Systems” is the correct terminology, not “points.”

I am afraid the article is misleading and could be providing inappropriate documentation advice to hospitalists dealing with CMS and AMA guidelines.

The “Billing and Coding Bandwagon” article in the May 2011 issue of The Hospitalist (p. 26) recently was brought to my attention and I have some concerns that the following statement gives a false impression of acceptable documentation: “When I first started working, I couldn’t believe that I could get audited and fined just because I didn’t add ‘10-point’ or ‘12-point’ to my note of ‘review of systems: negative,’” says hospitalist Amaka Nweke, MD, assistant director with Hospitalists Management Group (HMG) at Kenosha Medical Center in Kenosha, Wis. “I had a lot of frustration, because I had to repackage and re-present my notes in a manner that makes sense to Medicare but makes no sense to physicians.”