User login

Shorter Treatment for Vertebral Osteomyelitis May Be as Effective as Longer Treatment

Clinical question: Is a six-week regimen of antibiotics as effective as a 12-week regimen in the treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis?

Background: The optimal duration of antibiotic treatment for vertebral osteomyelitis is unknown. Previous guidelines recommending six to 12 weeks of therapy have been based on expert opinion rather than clinical trial data.

Study design: Multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Seventy-one medical care centers in France.

Synopsis: Three hundred fifty-six adult patients with culture-proven bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis were randomized to six- or 12- week antibiotic treatment regimens. The primary outcome was confirmed cure of infection at 12 months, as defined by absence of pain, fever, and CRP <10 mg/L. Outcomes were determined by a blinded panel of physicians.

Results showed 90.9% of the patients in the six-week group, and 90.8% of the patients in the 12-week group, met criteria for clinical cure. The lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the difference in percentages of cure between groups was -6.2%, satisfying the predetermined noninferiority margin of 10%.

Antibiotic therapy in this trial was governed by French guidelines, which recommend oral fluoroquinolones and rifampin as first-line agents for vertebral osteomyelitis. Median duration of IV antibiotic therapy was less than 14 days. Relatively few patients had abscesses, and only eight of the 145 patients with Staphylococcus aureus (SA) infections had methicillin-resistant SA (MRSA).

Bottom line: A six-week regimen of antibiotics was shown to be noninferior to a 12-week regimen for treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis. Treatment for longer than six weeks may be indicated in the setting of drug-resistant organisms, extensive bone destruction, or abscesses.

Clinical question: Is a six-week regimen of antibiotics as effective as a 12-week regimen in the treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis?

Background: The optimal duration of antibiotic treatment for vertebral osteomyelitis is unknown. Previous guidelines recommending six to 12 weeks of therapy have been based on expert opinion rather than clinical trial data.

Study design: Multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Seventy-one medical care centers in France.

Synopsis: Three hundred fifty-six adult patients with culture-proven bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis were randomized to six- or 12- week antibiotic treatment regimens. The primary outcome was confirmed cure of infection at 12 months, as defined by absence of pain, fever, and CRP <10 mg/L. Outcomes were determined by a blinded panel of physicians.

Results showed 90.9% of the patients in the six-week group, and 90.8% of the patients in the 12-week group, met criteria for clinical cure. The lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the difference in percentages of cure between groups was -6.2%, satisfying the predetermined noninferiority margin of 10%.

Antibiotic therapy in this trial was governed by French guidelines, which recommend oral fluoroquinolones and rifampin as first-line agents for vertebral osteomyelitis. Median duration of IV antibiotic therapy was less than 14 days. Relatively few patients had abscesses, and only eight of the 145 patients with Staphylococcus aureus (SA) infections had methicillin-resistant SA (MRSA).

Bottom line: A six-week regimen of antibiotics was shown to be noninferior to a 12-week regimen for treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis. Treatment for longer than six weeks may be indicated in the setting of drug-resistant organisms, extensive bone destruction, or abscesses.

Clinical question: Is a six-week regimen of antibiotics as effective as a 12-week regimen in the treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis?

Background: The optimal duration of antibiotic treatment for vertebral osteomyelitis is unknown. Previous guidelines recommending six to 12 weeks of therapy have been based on expert opinion rather than clinical trial data.

Study design: Multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Seventy-one medical care centers in France.

Synopsis: Three hundred fifty-six adult patients with culture-proven bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis were randomized to six- or 12- week antibiotic treatment regimens. The primary outcome was confirmed cure of infection at 12 months, as defined by absence of pain, fever, and CRP <10 mg/L. Outcomes were determined by a blinded panel of physicians.

Results showed 90.9% of the patients in the six-week group, and 90.8% of the patients in the 12-week group, met criteria for clinical cure. The lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the difference in percentages of cure between groups was -6.2%, satisfying the predetermined noninferiority margin of 10%.

Antibiotic therapy in this trial was governed by French guidelines, which recommend oral fluoroquinolones and rifampin as first-line agents for vertebral osteomyelitis. Median duration of IV antibiotic therapy was less than 14 days. Relatively few patients had abscesses, and only eight of the 145 patients with Staphylococcus aureus (SA) infections had methicillin-resistant SA (MRSA).

Bottom line: A six-week regimen of antibiotics was shown to be noninferior to a 12-week regimen for treatment of vertebral osteomyelitis. Treatment for longer than six weeks may be indicated in the setting of drug-resistant organisms, extensive bone destruction, or abscesses.

Hospitals Launch Bedside Procedure Services

A dedicated procedure team or service can give hospitals needed expertise without requiring a one-size-fits-all approach. In many cases, hospitalists run procedure services, but interventional radiologists and pulmonary critical care specialists also oversee some of them.

At The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the bedside procedure service began in the department of medicine and has since expanded throughout the hospital.

“I think a proceduralist service is as important as the hospitalist service,” says David Lichtman, PA, director of the service. He calls it “essential” for good patient care because it can allow experienced providers to be consistently involved in the process, whether proceduralists, medical students, or new interns perform the procedure.

“Patients have the benefit of expert care, and the trainees have the ability to learn and do without having to worry about working without a safety net,” he says. As a result, the service keeps patients safe while maximizing medical education.

At many institutions, a service or team can also meet a pressing need. In its seven years of existence, for example, the hospitalist-led procedures team at the University of Miami Jackson Memorial Hospital Medical Campus has been called upon to do more than 7,500 procedures.

“The idea behind procedure services is that you consolidate the expertise and training within a few people, be it a few hospitalists or a few proceduralists,” says Michelle Mourad, MD, director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California

San Francisco (UCSF). But a successful service can require significant investments in infrastructure and other resources. When they run the numbers, many hospitalist groups are forced to conclude that they simply don’t have sufficient demand to justify the expense of maintaining provider competency.

“People are really struggling with this,” she says.

The few studies conducted on procedure services, however, suggest that hospitals can benefit from improved patient satisfaction and a potential reduction in some complications.

“We were worried that that use of trainees and the teaching that went on at the bedside might be a concern for patients,” Dr. Mourad says of the UCSF procedures program. “We found that, instead, patients were reassured by having a designated expert in the room and recognized that it hadn’t always been the case in the past.” Accordingly, she says, a survey of satisfaction recorded “exceptionally high” rates.3

Initial research also suggests a reduction in such complications as thoracentesis-related pneumothorax.

“We have some inkling that perhaps the rigor with which we approach procedures, the high level of experience that we bring to procedures, and the presence of an expert in the room for every procedure may have decreased the complication rate for thoracentesis at our institution,” Dr. Mourad says.

At Boston University, the procedure service is based in the department of pulmonary critical care, and the department’s attending physicians supervise internal medicine residents. It was developed after “identifying some potential patient safety concerns with unsupervised resident procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, now a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass. A major aim of the procedure service, she says, is to provide supervision and teaching to medical house staff performing the procedures.

To test whether the service was delivering on those goals, Dr. Tukey and colleagues studied thoracentesis, paracentesis, central line, and lumbar puncture procedures.4 The study, an 18-month comparison of the procedures performed by the dedicated procedure service versus those done by other providers, found no significant difference in what were already quite low complication rates.

Unexpectedly, the researchers didn’t see higher levels of resident engagement in procedures performed by the procedure team, but they did find improvement in “best practice safety process measures,” such as whether ultrasound use followed established recommendations.

“I think that whenever you’re looking at quality improvement initiatives, you have to have an understanding of what might be the potential benefits,”

Dr. Tukey says. Her study, at least, suggests that launching a procedure service primarily to reduce the number of severe complications may not be the most appropriate goal. On the other hand, she says, the data do support the “very realistic goals” of improving residency education and maintaining procedure quality.

A dedicated service may not be a cure-all, in other words. And it’s certainly not for everyone. But given enough resources and buy-in, experts say, it could at least help put a hospital’s ailing bedside procedure strategy on the road to recovery without overextending its providers.

A dedicated procedure team or service can give hospitals needed expertise without requiring a one-size-fits-all approach. In many cases, hospitalists run procedure services, but interventional radiologists and pulmonary critical care specialists also oversee some of them.

At The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the bedside procedure service began in the department of medicine and has since expanded throughout the hospital.

“I think a proceduralist service is as important as the hospitalist service,” says David Lichtman, PA, director of the service. He calls it “essential” for good patient care because it can allow experienced providers to be consistently involved in the process, whether proceduralists, medical students, or new interns perform the procedure.

“Patients have the benefit of expert care, and the trainees have the ability to learn and do without having to worry about working without a safety net,” he says. As a result, the service keeps patients safe while maximizing medical education.

At many institutions, a service or team can also meet a pressing need. In its seven years of existence, for example, the hospitalist-led procedures team at the University of Miami Jackson Memorial Hospital Medical Campus has been called upon to do more than 7,500 procedures.

“The idea behind procedure services is that you consolidate the expertise and training within a few people, be it a few hospitalists or a few proceduralists,” says Michelle Mourad, MD, director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California

San Francisco (UCSF). But a successful service can require significant investments in infrastructure and other resources. When they run the numbers, many hospitalist groups are forced to conclude that they simply don’t have sufficient demand to justify the expense of maintaining provider competency.

“People are really struggling with this,” she says.

The few studies conducted on procedure services, however, suggest that hospitals can benefit from improved patient satisfaction and a potential reduction in some complications.

“We were worried that that use of trainees and the teaching that went on at the bedside might be a concern for patients,” Dr. Mourad says of the UCSF procedures program. “We found that, instead, patients were reassured by having a designated expert in the room and recognized that it hadn’t always been the case in the past.” Accordingly, she says, a survey of satisfaction recorded “exceptionally high” rates.3

Initial research also suggests a reduction in such complications as thoracentesis-related pneumothorax.

“We have some inkling that perhaps the rigor with which we approach procedures, the high level of experience that we bring to procedures, and the presence of an expert in the room for every procedure may have decreased the complication rate for thoracentesis at our institution,” Dr. Mourad says.

At Boston University, the procedure service is based in the department of pulmonary critical care, and the department’s attending physicians supervise internal medicine residents. It was developed after “identifying some potential patient safety concerns with unsupervised resident procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, now a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass. A major aim of the procedure service, she says, is to provide supervision and teaching to medical house staff performing the procedures.

To test whether the service was delivering on those goals, Dr. Tukey and colleagues studied thoracentesis, paracentesis, central line, and lumbar puncture procedures.4 The study, an 18-month comparison of the procedures performed by the dedicated procedure service versus those done by other providers, found no significant difference in what were already quite low complication rates.

Unexpectedly, the researchers didn’t see higher levels of resident engagement in procedures performed by the procedure team, but they did find improvement in “best practice safety process measures,” such as whether ultrasound use followed established recommendations.

“I think that whenever you’re looking at quality improvement initiatives, you have to have an understanding of what might be the potential benefits,”

Dr. Tukey says. Her study, at least, suggests that launching a procedure service primarily to reduce the number of severe complications may not be the most appropriate goal. On the other hand, she says, the data do support the “very realistic goals” of improving residency education and maintaining procedure quality.

A dedicated service may not be a cure-all, in other words. And it’s certainly not for everyone. But given enough resources and buy-in, experts say, it could at least help put a hospital’s ailing bedside procedure strategy on the road to recovery without overextending its providers.

A dedicated procedure team or service can give hospitals needed expertise without requiring a one-size-fits-all approach. In many cases, hospitalists run procedure services, but interventional radiologists and pulmonary critical care specialists also oversee some of them.

At The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the bedside procedure service began in the department of medicine and has since expanded throughout the hospital.

“I think a proceduralist service is as important as the hospitalist service,” says David Lichtman, PA, director of the service. He calls it “essential” for good patient care because it can allow experienced providers to be consistently involved in the process, whether proceduralists, medical students, or new interns perform the procedure.

“Patients have the benefit of expert care, and the trainees have the ability to learn and do without having to worry about working without a safety net,” he says. As a result, the service keeps patients safe while maximizing medical education.

At many institutions, a service or team can also meet a pressing need. In its seven years of existence, for example, the hospitalist-led procedures team at the University of Miami Jackson Memorial Hospital Medical Campus has been called upon to do more than 7,500 procedures.

“The idea behind procedure services is that you consolidate the expertise and training within a few people, be it a few hospitalists or a few proceduralists,” says Michelle Mourad, MD, director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California

San Francisco (UCSF). But a successful service can require significant investments in infrastructure and other resources. When they run the numbers, many hospitalist groups are forced to conclude that they simply don’t have sufficient demand to justify the expense of maintaining provider competency.

“People are really struggling with this,” she says.

The few studies conducted on procedure services, however, suggest that hospitals can benefit from improved patient satisfaction and a potential reduction in some complications.

“We were worried that that use of trainees and the teaching that went on at the bedside might be a concern for patients,” Dr. Mourad says of the UCSF procedures program. “We found that, instead, patients were reassured by having a designated expert in the room and recognized that it hadn’t always been the case in the past.” Accordingly, she says, a survey of satisfaction recorded “exceptionally high” rates.3

Initial research also suggests a reduction in such complications as thoracentesis-related pneumothorax.

“We have some inkling that perhaps the rigor with which we approach procedures, the high level of experience that we bring to procedures, and the presence of an expert in the room for every procedure may have decreased the complication rate for thoracentesis at our institution,” Dr. Mourad says.

At Boston University, the procedure service is based in the department of pulmonary critical care, and the department’s attending physicians supervise internal medicine residents. It was developed after “identifying some potential patient safety concerns with unsupervised resident procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, now a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass. A major aim of the procedure service, she says, is to provide supervision and teaching to medical house staff performing the procedures.

To test whether the service was delivering on those goals, Dr. Tukey and colleagues studied thoracentesis, paracentesis, central line, and lumbar puncture procedures.4 The study, an 18-month comparison of the procedures performed by the dedicated procedure service versus those done by other providers, found no significant difference in what were already quite low complication rates.

Unexpectedly, the researchers didn’t see higher levels of resident engagement in procedures performed by the procedure team, but they did find improvement in “best practice safety process measures,” such as whether ultrasound use followed established recommendations.

“I think that whenever you’re looking at quality improvement initiatives, you have to have an understanding of what might be the potential benefits,”

Dr. Tukey says. Her study, at least, suggests that launching a procedure service primarily to reduce the number of severe complications may not be the most appropriate goal. On the other hand, she says, the data do support the “very realistic goals” of improving residency education and maintaining procedure quality.

A dedicated service may not be a cure-all, in other words. And it’s certainly not for everyone. But given enough resources and buy-in, experts say, it could at least help put a hospital’s ailing bedside procedure strategy on the road to recovery without overextending its providers.

Clinical Images Capture Hospitalists’ Daily Rounds

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fourth in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is a collection of 76 clinical cases discussing actual patient scenarios with accompanying clinical case questions, images, and evidence-based discussions. Cases are presented in the same manner a practicing hospitalist would encounter them during daily rounds—that is to say, randomly. Chosen cases vary widely, from aspiration pneumonitis to necrotizing fasciitis, and are also representative of a day in the life of most hospitalists. The clinical images are of excellent quality and accurately represent the conditions discussed. The case discussions are logical, clinically relevant, and evidence-based.

Analysis

In this reviewer’s opinion, Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is required reading for all practicing hospitalists. The full-color images are high resolution and presented as patients would be viewed from the bedside. The cases are diverse and absolutely pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine. I am confident even the most experienced reader will learn something that will quite probably improve his or her diagnostic capability.

Dr. Lindsey is a hospitalist and chief of staff at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas. She has been a member of Team Hospitalist since 2013.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fourth in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is a collection of 76 clinical cases discussing actual patient scenarios with accompanying clinical case questions, images, and evidence-based discussions. Cases are presented in the same manner a practicing hospitalist would encounter them during daily rounds—that is to say, randomly. Chosen cases vary widely, from aspiration pneumonitis to necrotizing fasciitis, and are also representative of a day in the life of most hospitalists. The clinical images are of excellent quality and accurately represent the conditions discussed. The case discussions are logical, clinically relevant, and evidence-based.

Analysis

In this reviewer’s opinion, Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is required reading for all practicing hospitalists. The full-color images are high resolution and presented as patients would be viewed from the bedside. The cases are diverse and absolutely pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine. I am confident even the most experienced reader will learn something that will quite probably improve his or her diagnostic capability.

Dr. Lindsey is a hospitalist and chief of staff at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas. She has been a member of Team Hospitalist since 2013.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fourth in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is a collection of 76 clinical cases discussing actual patient scenarios with accompanying clinical case questions, images, and evidence-based discussions. Cases are presented in the same manner a practicing hospitalist would encounter them during daily rounds—that is to say, randomly. Chosen cases vary widely, from aspiration pneumonitis to necrotizing fasciitis, and are also representative of a day in the life of most hospitalists. The clinical images are of excellent quality and accurately represent the conditions discussed. The case discussions are logical, clinically relevant, and evidence-based.

Analysis

In this reviewer’s opinion, Hospital Images: A Clinical Atlas is required reading for all practicing hospitalists. The full-color images are high resolution and presented as patients would be viewed from the bedside. The cases are diverse and absolutely pertinent to the practice of hospital medicine. I am confident even the most experienced reader will learn something that will quite probably improve his or her diagnostic capability.

Dr. Lindsey is a hospitalist and chief of staff at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas. She has been a member of Team Hospitalist since 2013.

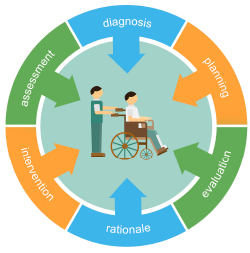

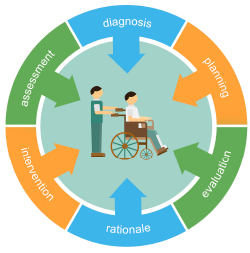

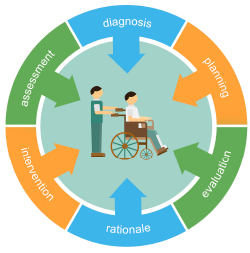

How to Initiate a VTE Quality Improvement Project

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

Hospitalists Try To Reclaim Lead Role in Bedside Procedures

On his way to a recent conference, David Lichtman, PA, stopped to talk with medical residents at a nearby medical center about their experiences performing bedside procedures. “How many times have you guys done something that you knew you weren’t fully trained for but you didn’t want to say anything?” asked Lichtman, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md. “At least once?”

Everyone raised a hand.

When Lichtman asked how many of the residents had ever spoken up and admitted being uncomfortable about doing a procedure, however, only about 20% raised their hands.

It’s one thing to struggle with a procedure like drawing blood. But a less-than-confident or unskilled provider who attempts more invasive procedures, such as a central line insertion or thoracentesis, can do major harm. And observers say confidence and competence levels, particularly among internal medicine residents, are heading in the wrong direction.

Two years ago, in fact, three hospitalists penned an article in The Hospitalist lamenting the “sharp decline” of HM proficiency in bedside procedures.1 Co-author Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety and medical director of the hospital’s Procedure Service, says the trend is continuing for several reasons.

“One is internal medicine’s willingness to surrender these bedside procedures to others,” Dr. Lenchus says, perhaps due to time constraints, a lack of confidence, or a perception that it’s not cost effective for HM providers to take on the role. Several medical organizations have loosened their competency standards, and the default in many cases has been for interventional radiologists to perform the procedures instead.

Another reason may be more practical: Perhaps there just isn’t a need for all hospitalists to perform them. Many new hospitalist positions advertised through employment agencies, Dr. Lenchus says, do not require competency in bedside procedures.

“The question is, did that happen first and then we reacted to it as hospitalists, or did we stop doing them and employment agencies then modified their process to reflect that?” he says.

For hospitalists, perhaps the bigger question is this: Is there a need to address the decline?

For Lichtman, Dr. Lenchus, and many other leaders, the answer is an emphatic yes—an opportunity to carve out a niche of skilled and patient-focused bedside care and to demonstrate real value to hospitals.

“I think it makes perfect sense from a financial and throughput and healthcare system perspective,” he says. The talent, knowledge, and experience of interventional radiologists, Dr. Lenchus says, is far better spent on procedures that cannot be conducted at a patient’s bedside.

It’s also a matter of professional pride for hospitalists like Michelle Mourad, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine and director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“I derive a tremendous amount of enjoyment from working with my hands, from being able to provide my patients this service, from often giving them relief from excessive fluid buildup, and from being able to do these procedures at the bedside,” she says.

Reversing the recent slide of hospitalist involvement in procedures, however, may require more cohesive expectations, an emphasis on minimizing complications, identification of willing and able procedure champions, and comprehensive technology-aided training.

Confounding Expectations

Paracentesis, thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, lumbar puncture, and central line placement generally are considered “core” bedside procedures. Experts like Lichtman, however, say little agreement exists on the main procedures for which hospitalists should demonstrate competency.

“We don’t have any semblance of that,” he says. “The reality is that different groups have different beliefs, and different hospitals have different protocols that they follow.”

Pinning down a consistent list can be difficult, because HM providers can play different roles depending on the setting, says hospitalist Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“You could be in an academic center. You could be in a community hospital. You could be in a rural setting where there’s no other access to anyone else doing these procedures, or you can have a robust interventional radiology service that will do all the procedures for you,” she says.

In 2007, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) revised its procedure-related requirements for board certification. Physicians still had to understand indications and contraindications, recognize the risks and benefits and manage complications, and interpret procedure results. But they no longer had to perform a minimum number to demonstrate competency. To assure “adequate knowledge and understanding” of each procedure, however, ABIM recommended that residents be active participants five or more times. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) followed suit in its program requirements for internal medicine.

Furman McDonald, MD, ABIM’s vice president of graduate medical education, says the board isn’t suggesting that procedure training should be limited to “book learning.” Rather, he says, the revision reflects the broad range of practice among internists and the recognition that not all of them will be conducting bedside procedures as part of their daily responsibilities. In that context, then, perhaps more rigorous training should be linked to the honing of a subspecialty practice that demands competency in specific procedures.

“It really is one of those areas where I don’t think one size fits all when it comes to training needs,” Dr. McDonald says, “and it’s also an area where practices vary so much depending on the size of the institution and availability of the people who can do the procedures.”

Nevertheless, observers say the retreat from an absolute numerical threshold—itself a debatable standard—set the tone for many hospitalist groups and has contributed to a lack of consistency in expectations.

“If someone is never going to be doing these procedures in their career, we can argue whether they should be trained,” says Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. But evidence suggests that internal medicine residents are still performing many bedside procedures in academic hospitals, he says. A recent study of his, in fact, found that internal medicine and family medicine-trained clinicians frequently perform paracentesis procedures on complex inpatients.2 If they’re expected to be able to do these procedures safely on the first day of residency, he says, the lack of a requirement for hands-on competency is “ridiculous.”

Whatever the reasons, observers say, fewer well-trained hospitalists are performing bedside procedures on a routine basis.

“I think we’re seeing a trend away from an expectation that all residents are going to be comfortable and qualified to perform these procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass., who has studied procedural training and outcomes. “That is reflected in the literature showing that a lot of graduating residents, even before these changes were made, felt uncomfortable performing these procedures unsupervised, even later into their residency.”

By changing their requirements, however, she says the ABIM and ACGME have effectively accelerated the de-emphasis on procedures among internal medicine generalists and put the onus on individual hospitals to ensure that they have qualified and capable staff to perform them. As a result, some medical institutions are opting to train a smaller subset of internal medicine physicians, while others are shifting the workload to other subspecialists.

Lichtman says he’s frustrated that many medical boards and programs continue to link competency in bedside procedures to arbitrary numbers that seem to come out of “thin air.” While studies suggest that practitioners aren’t experienced until they’ve performed 50 central line insertions, for example, many guidelines suggest that they can perform the procedure on their own after only five supervised insertions. “My thought is, you need as many as it takes for you, as an individual, to become good,” Lichtman says. “That may be five. It may be 10. It may be 100.”

Virtually all of us started doing this because we were asked to do cases that couldn’t be done by others because we had imaging—usually ultrasound guidance—and that yielded superior results. —Robert L. Vogelzang, MD, FSIR, professor of radiology, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, and past president, Society for Interventional Radiology

Complicating Factors

Central venous line placement has been a lightning rod in the debate over training, standardization, and staffing roles for bedside procedures, Lichtman says, due in large part to the seriousness of a central line-associated bloodstream infection, or CLABSI. In 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services deemed the preventable and life-threatening infection a “never” event and stopped reimbursing hospitals for any CLABSI-related treatment costs.

“If I’m trying to stick a needle in your knee to drain fluid out, there’s a really low risk of something catastrophically bad happening,” he says. But patients can die from faulty central line insertion and management. Stick the needle in the wrong place, and you could cause unnecessary bleeding, a stroke, or complications ranging from a fistula to a hemopneumothorax.

If discomfort and concern over potential complications are contributing to a decline in hospitalist-led bedside procedures, many experts agree that the role may not always make economic or practical sense either. “It doesn’t make sense to train all hospitalists to do all of these procedures,” Dr. Lenchus says. “If you’re at a small community hospital where the procedures are done in the ICU and you have no ICU coverage, then, frankly, that skill’s going to be lost on you, because you’re never going to do it in the real world in the course of your normal, everyday activities.”

Even at bigger institutions, he says, it makes sense to identify and train a core group of providers who have both the skill and the desire to perform procedures on a consistent basis. “It’s a technical skill. Not all of us could be concert pianists, even if we were trained,” Dr. Lenchus says.

Dr. Wang says it will be particularly important for hospitalist groups to identify a subset of “procedure champions” who enjoy doing the procedures, are good at it, have been properly trained, and can maintain their competency with regular practice.

Familiar Territory

At first glance, the significant time commitment and lackluster reimbursement of many bedside procedures would seem to do little to up the incentive for busy hospitalists. “If they have to stop and take two hours to do a procedure that 1) they don’t feel comfortable with and 2) they get very little reimbursement for, why not just put an order in and have interventional radiologists whisk them off and do these procedures?” Dr. Wang says.

Robert L. Vogelzang, MD, FSIR, professor of radiology at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago and a past president of the Society of Interventional Radiology, says radiologists are regularly called upon to perform bedside procedures because of their imaging expertise.

“Virtually all of us started doing this because we were asked to do cases that couldn’t be done by others because we had imaging—usually ultrasound guidance—and that yielded superior results,” he says.

Dr. Vogelzang says he’s “specialty-agnostic” about who should perform the procedures, as long as they’re done by well-trained providers who use imaging guidance and do them on a regular basis. Hospitalists could defer to radiologists if they’re uncomfortable with any procedure, he says, while teams of physician assistants and nurse practitioners might offer another cost-effective solution. Ultimately, the question over who performs minor bedside procedures “is going to reach a solution that involves dedicated teams in some fashion, because as a patient, you don’t want someone who does five a year,” he says. “Patient care is improved by trained people who do enough of them to do it consistently.”

So why not train designated hospitalists as proceduralists? Dr. Lenchus and other experts say naysayers who believe hospitalists should give up the role aren’t fully considering the impact of a well-trained individual or team. “It’s not just the money that you bring in—it’s the money that you don’t spend,” he says. An initial hospitalist consultation, for example, may determine that a procedure isn’t needed at all for some patients. Perhaps more importantly, a well-trained provider can reduce or eliminate costly complications, such as CLABSIs.

Dr. Wang agrees, stressing that the profession still has the opportunity to build a niche in providing care that decreases overall hospital costs. Instead of regularly sending patients to the interventional radiology department, she says, hospitalist-performed bedside procedures can allow radiologists to focus on more complex cases.

A hospitalist, she says, can generate additional value by eliminating the need to put in a separate order, provide patient transportation, or spend more time fitting the patient into another specialist’s schedule—potentially extending that patient’s length of stay. The economic case for hospitalist-led procedures could improve even more under a bundled payment structure, Dr. Wang says.

“I see a future here if the accountable care organizations are infiltrated through the United States,” she says.

Future involvement of hospitalists in bedside procedures also could depend on the ability of programs to deliver top-notch teaching and training options. At Harvard Medical School, Dr. Wang regularly trains internal medicine residents, fellows, and even some attending physicians with a “robust” curriculum that includes hands-on practice with ultrasound in a simulation center and one-on-one testing on patients. Since instituting the training program a few years ago, she says, procedure-related infection rates have dropped to zero. Within the hospital’s ICUs, Dr. Wang says, complication rates have dropped as well.

Among the comments she now regularly hears: “Oh my gosh. I can’t believe we used to do this without a training program.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle and frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Chang W, Lenchus J, Barsuk J. A lost art? The Hospitalist. 2012;16(6):1,28,30,32.

- Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168.

- Mourad M, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Sliwka D. Patient satisfaction with a hospitalist procedure service: Is bedside procedure teaching reassuring to patients? J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4):219-224.

- Tukey MH, Wiener RS. The impact of a medical procedure service on patient safety, procedure quality and resident training opportunities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29(3):485-490.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB. Simulation-based mastery learning reduces complications during central venous catheter insertion in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2697-2701.

On his way to a recent conference, David Lichtman, PA, stopped to talk with medical residents at a nearby medical center about their experiences performing bedside procedures. “How many times have you guys done something that you knew you weren’t fully trained for but you didn’t want to say anything?” asked Lichtman, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md. “At least once?”

Everyone raised a hand.

When Lichtman asked how many of the residents had ever spoken up and admitted being uncomfortable about doing a procedure, however, only about 20% raised their hands.

It’s one thing to struggle with a procedure like drawing blood. But a less-than-confident or unskilled provider who attempts more invasive procedures, such as a central line insertion or thoracentesis, can do major harm. And observers say confidence and competence levels, particularly among internal medicine residents, are heading in the wrong direction.

Two years ago, in fact, three hospitalists penned an article in The Hospitalist lamenting the “sharp decline” of HM proficiency in bedside procedures.1 Co-author Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety and medical director of the hospital’s Procedure Service, says the trend is continuing for several reasons.

“One is internal medicine’s willingness to surrender these bedside procedures to others,” Dr. Lenchus says, perhaps due to time constraints, a lack of confidence, or a perception that it’s not cost effective for HM providers to take on the role. Several medical organizations have loosened their competency standards, and the default in many cases has been for interventional radiologists to perform the procedures instead.

Another reason may be more practical: Perhaps there just isn’t a need for all hospitalists to perform them. Many new hospitalist positions advertised through employment agencies, Dr. Lenchus says, do not require competency in bedside procedures.

“The question is, did that happen first and then we reacted to it as hospitalists, or did we stop doing them and employment agencies then modified their process to reflect that?” he says.

For hospitalists, perhaps the bigger question is this: Is there a need to address the decline?

For Lichtman, Dr. Lenchus, and many other leaders, the answer is an emphatic yes—an opportunity to carve out a niche of skilled and patient-focused bedside care and to demonstrate real value to hospitals.

“I think it makes perfect sense from a financial and throughput and healthcare system perspective,” he says. The talent, knowledge, and experience of interventional radiologists, Dr. Lenchus says, is far better spent on procedures that cannot be conducted at a patient’s bedside.

It’s also a matter of professional pride for hospitalists like Michelle Mourad, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine and director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“I derive a tremendous amount of enjoyment from working with my hands, from being able to provide my patients this service, from often giving them relief from excessive fluid buildup, and from being able to do these procedures at the bedside,” she says.

Reversing the recent slide of hospitalist involvement in procedures, however, may require more cohesive expectations, an emphasis on minimizing complications, identification of willing and able procedure champions, and comprehensive technology-aided training.

Confounding Expectations

Paracentesis, thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, lumbar puncture, and central line placement generally are considered “core” bedside procedures. Experts like Lichtman, however, say little agreement exists on the main procedures for which hospitalists should demonstrate competency.

“We don’t have any semblance of that,” he says. “The reality is that different groups have different beliefs, and different hospitals have different protocols that they follow.”

Pinning down a consistent list can be difficult, because HM providers can play different roles depending on the setting, says hospitalist Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“You could be in an academic center. You could be in a community hospital. You could be in a rural setting where there’s no other access to anyone else doing these procedures, or you can have a robust interventional radiology service that will do all the procedures for you,” she says.

In 2007, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) revised its procedure-related requirements for board certification. Physicians still had to understand indications and contraindications, recognize the risks and benefits and manage complications, and interpret procedure results. But they no longer had to perform a minimum number to demonstrate competency. To assure “adequate knowledge and understanding” of each procedure, however, ABIM recommended that residents be active participants five or more times. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) followed suit in its program requirements for internal medicine.

Furman McDonald, MD, ABIM’s vice president of graduate medical education, says the board isn’t suggesting that procedure training should be limited to “book learning.” Rather, he says, the revision reflects the broad range of practice among internists and the recognition that not all of them will be conducting bedside procedures as part of their daily responsibilities. In that context, then, perhaps more rigorous training should be linked to the honing of a subspecialty practice that demands competency in specific procedures.

“It really is one of those areas where I don’t think one size fits all when it comes to training needs,” Dr. McDonald says, “and it’s also an area where practices vary so much depending on the size of the institution and availability of the people who can do the procedures.”

Nevertheless, observers say the retreat from an absolute numerical threshold—itself a debatable standard—set the tone for many hospitalist groups and has contributed to a lack of consistency in expectations.

“If someone is never going to be doing these procedures in their career, we can argue whether they should be trained,” says Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. But evidence suggests that internal medicine residents are still performing many bedside procedures in academic hospitals, he says. A recent study of his, in fact, found that internal medicine and family medicine-trained clinicians frequently perform paracentesis procedures on complex inpatients.2 If they’re expected to be able to do these procedures safely on the first day of residency, he says, the lack of a requirement for hands-on competency is “ridiculous.”

Whatever the reasons, observers say, fewer well-trained hospitalists are performing bedside procedures on a routine basis.

“I think we’re seeing a trend away from an expectation that all residents are going to be comfortable and qualified to perform these procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass., who has studied procedural training and outcomes. “That is reflected in the literature showing that a lot of graduating residents, even before these changes were made, felt uncomfortable performing these procedures unsupervised, even later into their residency.”

By changing their requirements, however, she says the ABIM and ACGME have effectively accelerated the de-emphasis on procedures among internal medicine generalists and put the onus on individual hospitals to ensure that they have qualified and capable staff to perform them. As a result, some medical institutions are opting to train a smaller subset of internal medicine physicians, while others are shifting the workload to other subspecialists.

Lichtman says he’s frustrated that many medical boards and programs continue to link competency in bedside procedures to arbitrary numbers that seem to come out of “thin air.” While studies suggest that practitioners aren’t experienced until they’ve performed 50 central line insertions, for example, many guidelines suggest that they can perform the procedure on their own after only five supervised insertions. “My thought is, you need as many as it takes for you, as an individual, to become good,” Lichtman says. “That may be five. It may be 10. It may be 100.”

Virtually all of us started doing this because we were asked to do cases that couldn’t be done by others because we had imaging—usually ultrasound guidance—and that yielded superior results. —Robert L. Vogelzang, MD, FSIR, professor of radiology, Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, and past president, Society for Interventional Radiology

Complicating Factors

Central venous line placement has been a lightning rod in the debate over training, standardization, and staffing roles for bedside procedures, Lichtman says, due in large part to the seriousness of a central line-associated bloodstream infection, or CLABSI. In 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services deemed the preventable and life-threatening infection a “never” event and stopped reimbursing hospitals for any CLABSI-related treatment costs.

“If I’m trying to stick a needle in your knee to drain fluid out, there’s a really low risk of something catastrophically bad happening,” he says. But patients can die from faulty central line insertion and management. Stick the needle in the wrong place, and you could cause unnecessary bleeding, a stroke, or complications ranging from a fistula to a hemopneumothorax.

If discomfort and concern over potential complications are contributing to a decline in hospitalist-led bedside procedures, many experts agree that the role may not always make economic or practical sense either. “It doesn’t make sense to train all hospitalists to do all of these procedures,” Dr. Lenchus says. “If you’re at a small community hospital where the procedures are done in the ICU and you have no ICU coverage, then, frankly, that skill’s going to be lost on you, because you’re never going to do it in the real world in the course of your normal, everyday activities.”

Even at bigger institutions, he says, it makes sense to identify and train a core group of providers who have both the skill and the desire to perform procedures on a consistent basis. “It’s a technical skill. Not all of us could be concert pianists, even if we were trained,” Dr. Lenchus says.

Dr. Wang says it will be particularly important for hospitalist groups to identify a subset of “procedure champions” who enjoy doing the procedures, are good at it, have been properly trained, and can maintain their competency with regular practice.

Familiar Territory

At first glance, the significant time commitment and lackluster reimbursement of many bedside procedures would seem to do little to up the incentive for busy hospitalists. “If they have to stop and take two hours to do a procedure that 1) they don’t feel comfortable with and 2) they get very little reimbursement for, why not just put an order in and have interventional radiologists whisk them off and do these procedures?” Dr. Wang says.

Robert L. Vogelzang, MD, FSIR, professor of radiology at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago and a past president of the Society of Interventional Radiology, says radiologists are regularly called upon to perform bedside procedures because of their imaging expertise.

“Virtually all of us started doing this because we were asked to do cases that couldn’t be done by others because we had imaging—usually ultrasound guidance—and that yielded superior results,” he says.

Dr. Vogelzang says he’s “specialty-agnostic” about who should perform the procedures, as long as they’re done by well-trained providers who use imaging guidance and do them on a regular basis. Hospitalists could defer to radiologists if they’re uncomfortable with any procedure, he says, while teams of physician assistants and nurse practitioners might offer another cost-effective solution. Ultimately, the question over who performs minor bedside procedures “is going to reach a solution that involves dedicated teams in some fashion, because as a patient, you don’t want someone who does five a year,” he says. “Patient care is improved by trained people who do enough of them to do it consistently.”

So why not train designated hospitalists as proceduralists? Dr. Lenchus and other experts say naysayers who believe hospitalists should give up the role aren’t fully considering the impact of a well-trained individual or team. “It’s not just the money that you bring in—it’s the money that you don’t spend,” he says. An initial hospitalist consultation, for example, may determine that a procedure isn’t needed at all for some patients. Perhaps more importantly, a well-trained provider can reduce or eliminate costly complications, such as CLABSIs.

Dr. Wang agrees, stressing that the profession still has the opportunity to build a niche in providing care that decreases overall hospital costs. Instead of regularly sending patients to the interventional radiology department, she says, hospitalist-performed bedside procedures can allow radiologists to focus on more complex cases.

A hospitalist, she says, can generate additional value by eliminating the need to put in a separate order, provide patient transportation, or spend more time fitting the patient into another specialist’s schedule—potentially extending that patient’s length of stay. The economic case for hospitalist-led procedures could improve even more under a bundled payment structure, Dr. Wang says.

“I see a future here if the accountable care organizations are infiltrated through the United States,” she says.

Future involvement of hospitalists in bedside procedures also could depend on the ability of programs to deliver top-notch teaching and training options. At Harvard Medical School, Dr. Wang regularly trains internal medicine residents, fellows, and even some attending physicians with a “robust” curriculum that includes hands-on practice with ultrasound in a simulation center and one-on-one testing on patients. Since instituting the training program a few years ago, she says, procedure-related infection rates have dropped to zero. Within the hospital’s ICUs, Dr. Wang says, complication rates have dropped as well.

Among the comments she now regularly hears: “Oh my gosh. I can’t believe we used to do this without a training program.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle and frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Chang W, Lenchus J, Barsuk J. A lost art? The Hospitalist. 2012;16(6):1,28,30,32.

- Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168.

- Mourad M, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Sliwka D. Patient satisfaction with a hospitalist procedure service: Is bedside procedure teaching reassuring to patients? J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4):219-224.

- Tukey MH, Wiener RS. The impact of a medical procedure service on patient safety, procedure quality and resident training opportunities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29(3):485-490.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB. Simulation-based mastery learning reduces complications during central venous catheter insertion in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2697-2701.

On his way to a recent conference, David Lichtman, PA, stopped to talk with medical residents at a nearby medical center about their experiences performing bedside procedures. “How many times have you guys done something that you knew you weren’t fully trained for but you didn’t want to say anything?” asked Lichtman, a hospitalist and director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md. “At least once?”

Everyone raised a hand.

When Lichtman asked how many of the residents had ever spoken up and admitted being uncomfortable about doing a procedure, however, only about 20% raised their hands.

It’s one thing to struggle with a procedure like drawing blood. But a less-than-confident or unskilled provider who attempts more invasive procedures, such as a central line insertion or thoracentesis, can do major harm. And observers say confidence and competence levels, particularly among internal medicine residents, are heading in the wrong direction.

Two years ago, in fact, three hospitalists penned an article in The Hospitalist lamenting the “sharp decline” of HM proficiency in bedside procedures.1 Co-author Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital Center for Patient Safety and medical director of the hospital’s Procedure Service, says the trend is continuing for several reasons.

“One is internal medicine’s willingness to surrender these bedside procedures to others,” Dr. Lenchus says, perhaps due to time constraints, a lack of confidence, or a perception that it’s not cost effective for HM providers to take on the role. Several medical organizations have loosened their competency standards, and the default in many cases has been for interventional radiologists to perform the procedures instead.

Another reason may be more practical: Perhaps there just isn’t a need for all hospitalists to perform them. Many new hospitalist positions advertised through employment agencies, Dr. Lenchus says, do not require competency in bedside procedures.

“The question is, did that happen first and then we reacted to it as hospitalists, or did we stop doing them and employment agencies then modified their process to reflect that?” he says.

For hospitalists, perhaps the bigger question is this: Is there a need to address the decline?

For Lichtman, Dr. Lenchus, and many other leaders, the answer is an emphatic yes—an opportunity to carve out a niche of skilled and patient-focused bedside care and to demonstrate real value to hospitals.

“I think it makes perfect sense from a financial and throughput and healthcare system perspective,” he says. The talent, knowledge, and experience of interventional radiologists, Dr. Lenchus says, is far better spent on procedures that cannot be conducted at a patient’s bedside.

It’s also a matter of professional pride for hospitalists like Michelle Mourad, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine and director of quality improvement and patient safety for the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“I derive a tremendous amount of enjoyment from working with my hands, from being able to provide my patients this service, from often giving them relief from excessive fluid buildup, and from being able to do these procedures at the bedside,” she says.

Reversing the recent slide of hospitalist involvement in procedures, however, may require more cohesive expectations, an emphasis on minimizing complications, identification of willing and able procedure champions, and comprehensive technology-aided training.

Confounding Expectations

Paracentesis, thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, lumbar puncture, and central line placement generally are considered “core” bedside procedures. Experts like Lichtman, however, say little agreement exists on the main procedures for which hospitalists should demonstrate competency.

“We don’t have any semblance of that,” he says. “The reality is that different groups have different beliefs, and different hospitals have different protocols that they follow.”

Pinning down a consistent list can be difficult, because HM providers can play different roles depending on the setting, says hospitalist Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“You could be in an academic center. You could be in a community hospital. You could be in a rural setting where there’s no other access to anyone else doing these procedures, or you can have a robust interventional radiology service that will do all the procedures for you,” she says.

In 2007, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) revised its procedure-related requirements for board certification. Physicians still had to understand indications and contraindications, recognize the risks and benefits and manage complications, and interpret procedure results. But they no longer had to perform a minimum number to demonstrate competency. To assure “adequate knowledge and understanding” of each procedure, however, ABIM recommended that residents be active participants five or more times. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) followed suit in its program requirements for internal medicine.

Furman McDonald, MD, ABIM’s vice president of graduate medical education, says the board isn’t suggesting that procedure training should be limited to “book learning.” Rather, he says, the revision reflects the broad range of practice among internists and the recognition that not all of them will be conducting bedside procedures as part of their daily responsibilities. In that context, then, perhaps more rigorous training should be linked to the honing of a subspecialty practice that demands competency in specific procedures.

“It really is one of those areas where I don’t think one size fits all when it comes to training needs,” Dr. McDonald says, “and it’s also an area where practices vary so much depending on the size of the institution and availability of the people who can do the procedures.”

Nevertheless, observers say the retreat from an absolute numerical threshold—itself a debatable standard—set the tone for many hospitalist groups and has contributed to a lack of consistency in expectations.

“If someone is never going to be doing these procedures in their career, we can argue whether they should be trained,” says Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. But evidence suggests that internal medicine residents are still performing many bedside procedures in academic hospitals, he says. A recent study of his, in fact, found that internal medicine and family medicine-trained clinicians frequently perform paracentesis procedures on complex inpatients.2 If they’re expected to be able to do these procedures safely on the first day of residency, he says, the lack of a requirement for hands-on competency is “ridiculous.”

Whatever the reasons, observers say, fewer well-trained hospitalists are performing bedside procedures on a routine basis.

“I think we’re seeing a trend away from an expectation that all residents are going to be comfortable and qualified to perform these procedures,” says Melissa Tukey, MD, MSc, a pulmonology critical care physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Mass., who has studied procedural training and outcomes. “That is reflected in the literature showing that a lot of graduating residents, even before these changes were made, felt uncomfortable performing these procedures unsupervised, even later into their residency.”

By changing their requirements, however, she says the ABIM and ACGME have effectively accelerated the de-emphasis on procedures among internal medicine generalists and put the onus on individual hospitals to ensure that they have qualified and capable staff to perform them. As a result, some medical institutions are opting to train a smaller subset of internal medicine physicians, while others are shifting the workload to other subspecialists.

Lichtman says he’s frustrated that many medical boards and programs continue to link competency in bedside procedures to arbitrary numbers that seem to come out of “thin air.” While studies suggest that practitioners aren’t experienced until they’ve performed 50 central line insertions, for example, many guidelines suggest that they can perform the procedure on their own after only five supervised insertions. “My thought is, you need as many as it takes for you, as an individual, to become good,” Lichtman says. “That may be five. It may be 10. It may be 100.”