User login

Intermittent, Continuous Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapies Are Comparable

Clinical question: Is intermittent proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy comparable to the current standard of continuous PPI infusion for high risk bleeding ulcers?

Background: Current guidelines recommend an intravenous bolus dose of a PPI followed by continuous PPI infusion for three days after endoscopic therapy in patients with high risk bleeding ulcers. Substitution of intermittent PPI therapy, if comparable, could decrease PPI dose, cost, and resource use.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

Setting: Review of medical databases through December 2013.

Synopsis: A total of 13 studies were identified that met eligibility criteria, with the primary outcome the incidence of recurrent bleeding within seven days of starting a PPI regimen.

The upper boundary of the 95% CI for the absolute risk difference between intermittent and continuous infusion PPI therapy was -0.28% for the primary outcome, indicating that there was no increase in recurrent bleeding with intermittent versus continuous PPI therapy.

Although overall analysis shows that the intermittent use of PPIs is noninferior to bolus plus continuous infusion of PPIs, this study does not delineate which intermittent PPI regimen is the most appropriate.

A variety of dosing schedules and total doses were used, different PPIs were utilized, and both oral and intravenous routes of administration were used. In addition, different endoscopic therapies may have achieved variable results for the primary outcome of rebleeding and could therefore confound the results.

Bottom line: Intermittent PPI therapy is comparable to the current guideline-recommended regimen of intravenous bolus plus continuous infusion of PPIs in patients with endoscopically treated, high risk bleeding ulcers.

Clinical question: Is intermittent proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy comparable to the current standard of continuous PPI infusion for high risk bleeding ulcers?

Background: Current guidelines recommend an intravenous bolus dose of a PPI followed by continuous PPI infusion for three days after endoscopic therapy in patients with high risk bleeding ulcers. Substitution of intermittent PPI therapy, if comparable, could decrease PPI dose, cost, and resource use.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

Setting: Review of medical databases through December 2013.

Synopsis: A total of 13 studies were identified that met eligibility criteria, with the primary outcome the incidence of recurrent bleeding within seven days of starting a PPI regimen.

The upper boundary of the 95% CI for the absolute risk difference between intermittent and continuous infusion PPI therapy was -0.28% for the primary outcome, indicating that there was no increase in recurrent bleeding with intermittent versus continuous PPI therapy.

Although overall analysis shows that the intermittent use of PPIs is noninferior to bolus plus continuous infusion of PPIs, this study does not delineate which intermittent PPI regimen is the most appropriate.

A variety of dosing schedules and total doses were used, different PPIs were utilized, and both oral and intravenous routes of administration were used. In addition, different endoscopic therapies may have achieved variable results for the primary outcome of rebleeding and could therefore confound the results.

Bottom line: Intermittent PPI therapy is comparable to the current guideline-recommended regimen of intravenous bolus plus continuous infusion of PPIs in patients with endoscopically treated, high risk bleeding ulcers.

Clinical question: Is intermittent proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy comparable to the current standard of continuous PPI infusion for high risk bleeding ulcers?

Background: Current guidelines recommend an intravenous bolus dose of a PPI followed by continuous PPI infusion for three days after endoscopic therapy in patients with high risk bleeding ulcers. Substitution of intermittent PPI therapy, if comparable, could decrease PPI dose, cost, and resource use.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

Setting: Review of medical databases through December 2013.

Synopsis: A total of 13 studies were identified that met eligibility criteria, with the primary outcome the incidence of recurrent bleeding within seven days of starting a PPI regimen.

The upper boundary of the 95% CI for the absolute risk difference between intermittent and continuous infusion PPI therapy was -0.28% for the primary outcome, indicating that there was no increase in recurrent bleeding with intermittent versus continuous PPI therapy.

Although overall analysis shows that the intermittent use of PPIs is noninferior to bolus plus continuous infusion of PPIs, this study does not delineate which intermittent PPI regimen is the most appropriate.

A variety of dosing schedules and total doses were used, different PPIs were utilized, and both oral and intravenous routes of administration were used. In addition, different endoscopic therapies may have achieved variable results for the primary outcome of rebleeding and could therefore confound the results.

Bottom line: Intermittent PPI therapy is comparable to the current guideline-recommended regimen of intravenous bolus plus continuous infusion of PPIs in patients with endoscopically treated, high risk bleeding ulcers.

VTE Treatment Strategies Don't Differ in Efficacy, Safety

Clinical question: Are there differences in efficacy and safety between the treatment strategies for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: There are a number of treatment strategies available for acute VTE. Prior to this study, no large meta-analysis review of strategies had been conducted to compare efficacy and safety.

Study design: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Patients with confirmed symptomatic acute VTE or confirmed symptomatic recurrent VTE in the inpatient or ambulatory setting

Synopsis: The review identified 45 relevant studies with a total of 44,989 patients. The resultant analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences for efficacy and safety among most treatment strategies used to treat acute VTE when compared with the low molecular weight heparin-vitamin K antagonist combination. Specifically, no differences were found between effectiveness and bleeding risk. However, the analysis did suggest that the unfractionated heparin-vitamin K antagonist combination was the least effective and resulted in higher rates of recurrent VTE. Additionally, the use of rivaroxaban or apixaban was associated with the lowest risk of bleeding.

Hospitalists treating patients with acute VTE need to use caution when attempting to translate these results into practice. This study did not address comorbidities present in patients with VTE that might limit certain treatment strategies. Also, no studies directly compare the new direct oral anticoagulants, so their use requires thoughtful consideration.

Bottom line: There is no significant difference in efficacy and safety between the strategies used to treat acute VTE.

Clinical question: Are there differences in efficacy and safety between the treatment strategies for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: There are a number of treatment strategies available for acute VTE. Prior to this study, no large meta-analysis review of strategies had been conducted to compare efficacy and safety.

Study design: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Patients with confirmed symptomatic acute VTE or confirmed symptomatic recurrent VTE in the inpatient or ambulatory setting

Synopsis: The review identified 45 relevant studies with a total of 44,989 patients. The resultant analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences for efficacy and safety among most treatment strategies used to treat acute VTE when compared with the low molecular weight heparin-vitamin K antagonist combination. Specifically, no differences were found between effectiveness and bleeding risk. However, the analysis did suggest that the unfractionated heparin-vitamin K antagonist combination was the least effective and resulted in higher rates of recurrent VTE. Additionally, the use of rivaroxaban or apixaban was associated with the lowest risk of bleeding.

Hospitalists treating patients with acute VTE need to use caution when attempting to translate these results into practice. This study did not address comorbidities present in patients with VTE that might limit certain treatment strategies. Also, no studies directly compare the new direct oral anticoagulants, so their use requires thoughtful consideration.

Bottom line: There is no significant difference in efficacy and safety between the strategies used to treat acute VTE.

Clinical question: Are there differences in efficacy and safety between the treatment strategies for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: There are a number of treatment strategies available for acute VTE. Prior to this study, no large meta-analysis review of strategies had been conducted to compare efficacy and safety.

Study design: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Patients with confirmed symptomatic acute VTE or confirmed symptomatic recurrent VTE in the inpatient or ambulatory setting

Synopsis: The review identified 45 relevant studies with a total of 44,989 patients. The resultant analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences for efficacy and safety among most treatment strategies used to treat acute VTE when compared with the low molecular weight heparin-vitamin K antagonist combination. Specifically, no differences were found between effectiveness and bleeding risk. However, the analysis did suggest that the unfractionated heparin-vitamin K antagonist combination was the least effective and resulted in higher rates of recurrent VTE. Additionally, the use of rivaroxaban or apixaban was associated with the lowest risk of bleeding.

Hospitalists treating patients with acute VTE need to use caution when attempting to translate these results into practice. This study did not address comorbidities present in patients with VTE that might limit certain treatment strategies. Also, no studies directly compare the new direct oral anticoagulants, so their use requires thoughtful consideration.

Bottom line: There is no significant difference in efficacy and safety between the strategies used to treat acute VTE.

Antimicrobial Prescribing Common in Inpatient Setting

Clinical question: What is the daily prevalence of antimicrobial use in acute-care hospitals?

Background: Inappropriate antimicrobial use is associated with adverse events and contributes to the emergence of resistant pathogens. Strategies need to be implemented to reduce inappropriate use. An understanding of antibiotic prevalence and epidemiology in hospitals will aid in the development of these strategies.

Study design: Cross-sectional prevalence study.

Setting: Acute-care hospitals in 10 states.

Synopsis: Surveys were conducted in 183 hospitals (11,282 patients) to assess the prevalence of antimicrobial prescription on a given day. The survey showed 51.9% of patients were receiving antimicrobials. Four antimicrobials (parenteral vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftriaxone, and levofloxacin) accounted for 45% of all antimicrobial treatments.

Additionally, 54% of antimicrobials were used to treat three infection syndromes: lower respiratory tract, urinary tract, and skin and soft tissue. This prescribing pattern was consistent between community-acquired infections and healthcare-acquired infections, as well as inside and outside the critical care unit. The study authors concluded that targeting these four antimicrobials and these three infection syndromes could be the focus of strategies for antimicrobial overuse.

Hospitalists need to use caution, as this data is from 2011 and patterns might have changed. Also, the study included only 183 hospitals, and generalizability is limited. In addition, the study did not take into account the patients’ diagnoses; therefore, it is difficult to assess the appropriateness of the antimicrobial prescriptions.

Bottom line: Use of broad spectrum antibiotics such as vancomycin is common in hospitalized patients.

Clinical question: What is the daily prevalence of antimicrobial use in acute-care hospitals?

Background: Inappropriate antimicrobial use is associated with adverse events and contributes to the emergence of resistant pathogens. Strategies need to be implemented to reduce inappropriate use. An understanding of antibiotic prevalence and epidemiology in hospitals will aid in the development of these strategies.

Study design: Cross-sectional prevalence study.

Setting: Acute-care hospitals in 10 states.

Synopsis: Surveys were conducted in 183 hospitals (11,282 patients) to assess the prevalence of antimicrobial prescription on a given day. The survey showed 51.9% of patients were receiving antimicrobials. Four antimicrobials (parenteral vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftriaxone, and levofloxacin) accounted for 45% of all antimicrobial treatments.

Additionally, 54% of antimicrobials were used to treat three infection syndromes: lower respiratory tract, urinary tract, and skin and soft tissue. This prescribing pattern was consistent between community-acquired infections and healthcare-acquired infections, as well as inside and outside the critical care unit. The study authors concluded that targeting these four antimicrobials and these three infection syndromes could be the focus of strategies for antimicrobial overuse.

Hospitalists need to use caution, as this data is from 2011 and patterns might have changed. Also, the study included only 183 hospitals, and generalizability is limited. In addition, the study did not take into account the patients’ diagnoses; therefore, it is difficult to assess the appropriateness of the antimicrobial prescriptions.

Bottom line: Use of broad spectrum antibiotics such as vancomycin is common in hospitalized patients.

Clinical question: What is the daily prevalence of antimicrobial use in acute-care hospitals?

Background: Inappropriate antimicrobial use is associated with adverse events and contributes to the emergence of resistant pathogens. Strategies need to be implemented to reduce inappropriate use. An understanding of antibiotic prevalence and epidemiology in hospitals will aid in the development of these strategies.

Study design: Cross-sectional prevalence study.

Setting: Acute-care hospitals in 10 states.

Synopsis: Surveys were conducted in 183 hospitals (11,282 patients) to assess the prevalence of antimicrobial prescription on a given day. The survey showed 51.9% of patients were receiving antimicrobials. Four antimicrobials (parenteral vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftriaxone, and levofloxacin) accounted for 45% of all antimicrobial treatments.

Additionally, 54% of antimicrobials were used to treat three infection syndromes: lower respiratory tract, urinary tract, and skin and soft tissue. This prescribing pattern was consistent between community-acquired infections and healthcare-acquired infections, as well as inside and outside the critical care unit. The study authors concluded that targeting these four antimicrobials and these three infection syndromes could be the focus of strategies for antimicrobial overuse.

Hospitalists need to use caution, as this data is from 2011 and patterns might have changed. Also, the study included only 183 hospitals, and generalizability is limited. In addition, the study did not take into account the patients’ diagnoses; therefore, it is difficult to assess the appropriateness of the antimicrobial prescriptions.

Bottom line: Use of broad spectrum antibiotics such as vancomycin is common in hospitalized patients.

Hemoglobin Transfusion Threshold Not Associated with Differences in Morbidity, Mortality Among Patients with Septic Shock

Clinical question: Is there a difference in 90-day mortality and other outcomes when a lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold is used for blood transfusions in ICU patients with septic shock?

Background: Patients with septic shock frequently receive blood transfusions. This often occurs in the setting of active bleeding but has also been observed in non-bleeding patients for variable hemoglobin levels. Concrete data regarding the efficacy and safety of such transfusions based on hemoglobin thresholds is lacking.

Study design: International, multi-center, stratified, parallel group randomized trial.

Setting: General ICUs in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

Synopsis: Researchers analyzed data from 998 ICU patients in the Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) trial. Primary outcome was 90-day mortality rate. Hemoglobin levels less than 7 gm/dL and 9 gm/dL were used for lower and higher hemoglobin thresholds, respectively. The mortality rates were 43% and 45%, respectively (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.78 -1.09; P=0.44); when adjusted for risk factors, the results were similar. Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes (i.e., use of life support, development of ischemic events, and severe adverse reactions).

Hospitalists involved in managing patients with septic shock should be mindful of similar 90-day mortality and several other secondary outcomes regardless of hemoglobin threshold.

Bottom line: Ninety-day mortality and other outcomes were not affected by transfusion thresholds in ICU patients with septic shock.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in 90-day mortality and other outcomes when a lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold is used for blood transfusions in ICU patients with septic shock?

Background: Patients with septic shock frequently receive blood transfusions. This often occurs in the setting of active bleeding but has also been observed in non-bleeding patients for variable hemoglobin levels. Concrete data regarding the efficacy and safety of such transfusions based on hemoglobin thresholds is lacking.

Study design: International, multi-center, stratified, parallel group randomized trial.

Setting: General ICUs in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

Synopsis: Researchers analyzed data from 998 ICU patients in the Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) trial. Primary outcome was 90-day mortality rate. Hemoglobin levels less than 7 gm/dL and 9 gm/dL were used for lower and higher hemoglobin thresholds, respectively. The mortality rates were 43% and 45%, respectively (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.78 -1.09; P=0.44); when adjusted for risk factors, the results were similar. Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes (i.e., use of life support, development of ischemic events, and severe adverse reactions).

Hospitalists involved in managing patients with septic shock should be mindful of similar 90-day mortality and several other secondary outcomes regardless of hemoglobin threshold.

Bottom line: Ninety-day mortality and other outcomes were not affected by transfusion thresholds in ICU patients with septic shock.

Clinical question: Is there a difference in 90-day mortality and other outcomes when a lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold is used for blood transfusions in ICU patients with septic shock?

Background: Patients with septic shock frequently receive blood transfusions. This often occurs in the setting of active bleeding but has also been observed in non-bleeding patients for variable hemoglobin levels. Concrete data regarding the efficacy and safety of such transfusions based on hemoglobin thresholds is lacking.

Study design: International, multi-center, stratified, parallel group randomized trial.

Setting: General ICUs in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

Synopsis: Researchers analyzed data from 998 ICU patients in the Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) trial. Primary outcome was 90-day mortality rate. Hemoglobin levels less than 7 gm/dL and 9 gm/dL were used for lower and higher hemoglobin thresholds, respectively. The mortality rates were 43% and 45%, respectively (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.78 -1.09; P=0.44); when adjusted for risk factors, the results were similar. Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes (i.e., use of life support, development of ischemic events, and severe adverse reactions).

Hospitalists involved in managing patients with septic shock should be mindful of similar 90-day mortality and several other secondary outcomes regardless of hemoglobin threshold.

Bottom line: Ninety-day mortality and other outcomes were not affected by transfusion thresholds in ICU patients with septic shock.

Early, Goal-Directed Therapy Doesn’t Improve Mortality in Patients with Early Septic Shock

Clinical question: Does early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) improve mortality in patients presenting to the ED with early septic shock?

Background: EGDT (achieving central venous pressure of 8-12 mmHg, superior vena oxygen saturation (ScvO2) of > 70%, mean arterial pressure ≥ 65mmHg, and urine output ≥ 0.5 mL/kg/h) has been endorsed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign as a key strategy to decrease mortality among patients with septic shock, but its effectiveness is uncertain and has been questioned by a recent randomized trial.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, parallel group trial.

Setting: Fifty-one tertiary and non-tertiary care metropolitan and rural hospitals, mainly in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,600 patients who presented to the ED with early septic shock (evidence of refractory hypotension or hypoperfusion) to receive EGDT or usual care for six hours. All patients received antimicrobials and fluid resuscitation (approximately 2.5 liters) before randomization. There was no significant difference between the groups for the primary outcome (all-cause mortality at 90 days), but the EGDT group was more likely to receive vasopressor support and red blood cell transfusions and to have invasive monitoring.

Analysis for the whole group and various patient subgroups (location, age, APACHE II score, and others) did not show any benefit from using EGDT for any outcomes (including length of stay in ICU and hospital, invasive mechanical ventilation, and use of renal replacement therapy).

This study confirms that early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of sepsis is crucial. EGDT might be less important when fluid resuscitation and antimicrobials are started early after sepsis is suspected. With continuous improvement in these areas, monitoring of certain parameters as required in EGDT (like ScvO2, which requires a special catheter) might not be as important.

Bottom line: Early-goal directed therapy is not associated with improved mortality in sepsis in patients treated early with antimicrobials and aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Clinical question: Does early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) improve mortality in patients presenting to the ED with early septic shock?

Background: EGDT (achieving central venous pressure of 8-12 mmHg, superior vena oxygen saturation (ScvO2) of > 70%, mean arterial pressure ≥ 65mmHg, and urine output ≥ 0.5 mL/kg/h) has been endorsed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign as a key strategy to decrease mortality among patients with septic shock, but its effectiveness is uncertain and has been questioned by a recent randomized trial.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, parallel group trial.

Setting: Fifty-one tertiary and non-tertiary care metropolitan and rural hospitals, mainly in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,600 patients who presented to the ED with early septic shock (evidence of refractory hypotension or hypoperfusion) to receive EGDT or usual care for six hours. All patients received antimicrobials and fluid resuscitation (approximately 2.5 liters) before randomization. There was no significant difference between the groups for the primary outcome (all-cause mortality at 90 days), but the EGDT group was more likely to receive vasopressor support and red blood cell transfusions and to have invasive monitoring.

Analysis for the whole group and various patient subgroups (location, age, APACHE II score, and others) did not show any benefit from using EGDT for any outcomes (including length of stay in ICU and hospital, invasive mechanical ventilation, and use of renal replacement therapy).

This study confirms that early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of sepsis is crucial. EGDT might be less important when fluid resuscitation and antimicrobials are started early after sepsis is suspected. With continuous improvement in these areas, monitoring of certain parameters as required in EGDT (like ScvO2, which requires a special catheter) might not be as important.

Bottom line: Early-goal directed therapy is not associated with improved mortality in sepsis in patients treated early with antimicrobials and aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Clinical question: Does early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) improve mortality in patients presenting to the ED with early septic shock?

Background: EGDT (achieving central venous pressure of 8-12 mmHg, superior vena oxygen saturation (ScvO2) of > 70%, mean arterial pressure ≥ 65mmHg, and urine output ≥ 0.5 mL/kg/h) has been endorsed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign as a key strategy to decrease mortality among patients with septic shock, but its effectiveness is uncertain and has been questioned by a recent randomized trial.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, parallel group trial.

Setting: Fifty-one tertiary and non-tertiary care metropolitan and rural hospitals, mainly in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,600 patients who presented to the ED with early septic shock (evidence of refractory hypotension or hypoperfusion) to receive EGDT or usual care for six hours. All patients received antimicrobials and fluid resuscitation (approximately 2.5 liters) before randomization. There was no significant difference between the groups for the primary outcome (all-cause mortality at 90 days), but the EGDT group was more likely to receive vasopressor support and red blood cell transfusions and to have invasive monitoring.

Analysis for the whole group and various patient subgroups (location, age, APACHE II score, and others) did not show any benefit from using EGDT for any outcomes (including length of stay in ICU and hospital, invasive mechanical ventilation, and use of renal replacement therapy).

This study confirms that early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of sepsis is crucial. EGDT might be less important when fluid resuscitation and antimicrobials are started early after sepsis is suspected. With continuous improvement in these areas, monitoring of certain parameters as required in EGDT (like ScvO2, which requires a special catheter) might not be as important.

Bottom line: Early-goal directed therapy is not associated with improved mortality in sepsis in patients treated early with antimicrobials and aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Arterial Catheter Use in ICU Doesn’t Improve Hospital Mortality

Clinical question: Does the use of arterial catheters (AC) improve hospital mortality in ICU patients requiring mechanical ventilation?

Background: AC are used in 40% of ICU patients, mostly to facilitate diagnostic phlebotomy (including arterial blood gases) and improve hemodynamic monitoring. Despite known risks (limb ischemia, pseudoaneurysms, infections) and costs necessary for insertion and maintenance, data regarding their impact on outcomes are limited.

Study design: Propensity-matched cohort analysis of data in the Project IMPACT database.

Setting: 139 ICUs in the U.S., with larger and urban hospitals providing the majority of the data.

Synopsis: Of 60,975 medical patients who required mechanical ventilation, 24,126 (39.6%) patients had an AC. Propensity score matching yielded 13,603 pairs of patients who did not have an AC with patients who did have an AC. For many variables that could influence mortality in such patients, there were no significant differences between the two groups. No association between AC use and hospital mortality in medical ICU patients who required mechanical ventilation was noted. This was confirmed in analyses of eight of nine secondary cohorts. In one cohort (patients requiring vasopressors), AC use was associated with an 8% increase in the odds of death. More blood transfusions were administered in the AC group, although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

Despite the rigorous and complex statistical analysis used in this study, residual confounders remained. It is still possible, but unlikely, that patients with an AC could have had a higher expected mortality, which the use of the AC ameliorated. This study raises an important question that should ideally be addressed by randomized trials.

Bottom line: Arterial catheters used in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU are not associated with lower mortality and should therefore be used with caution, weighing the risks and benefits, until more studies are performed.

Clinical question: Does the use of arterial catheters (AC) improve hospital mortality in ICU patients requiring mechanical ventilation?

Background: AC are used in 40% of ICU patients, mostly to facilitate diagnostic phlebotomy (including arterial blood gases) and improve hemodynamic monitoring. Despite known risks (limb ischemia, pseudoaneurysms, infections) and costs necessary for insertion and maintenance, data regarding their impact on outcomes are limited.

Study design: Propensity-matched cohort analysis of data in the Project IMPACT database.

Setting: 139 ICUs in the U.S., with larger and urban hospitals providing the majority of the data.

Synopsis: Of 60,975 medical patients who required mechanical ventilation, 24,126 (39.6%) patients had an AC. Propensity score matching yielded 13,603 pairs of patients who did not have an AC with patients who did have an AC. For many variables that could influence mortality in such patients, there were no significant differences between the two groups. No association between AC use and hospital mortality in medical ICU patients who required mechanical ventilation was noted. This was confirmed in analyses of eight of nine secondary cohorts. In one cohort (patients requiring vasopressors), AC use was associated with an 8% increase in the odds of death. More blood transfusions were administered in the AC group, although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

Despite the rigorous and complex statistical analysis used in this study, residual confounders remained. It is still possible, but unlikely, that patients with an AC could have had a higher expected mortality, which the use of the AC ameliorated. This study raises an important question that should ideally be addressed by randomized trials.

Bottom line: Arterial catheters used in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU are not associated with lower mortality and should therefore be used with caution, weighing the risks and benefits, until more studies are performed.

Clinical question: Does the use of arterial catheters (AC) improve hospital mortality in ICU patients requiring mechanical ventilation?

Background: AC are used in 40% of ICU patients, mostly to facilitate diagnostic phlebotomy (including arterial blood gases) and improve hemodynamic monitoring. Despite known risks (limb ischemia, pseudoaneurysms, infections) and costs necessary for insertion and maintenance, data regarding their impact on outcomes are limited.

Study design: Propensity-matched cohort analysis of data in the Project IMPACT database.

Setting: 139 ICUs in the U.S., with larger and urban hospitals providing the majority of the data.

Synopsis: Of 60,975 medical patients who required mechanical ventilation, 24,126 (39.6%) patients had an AC. Propensity score matching yielded 13,603 pairs of patients who did not have an AC with patients who did have an AC. For many variables that could influence mortality in such patients, there were no significant differences between the two groups. No association between AC use and hospital mortality in medical ICU patients who required mechanical ventilation was noted. This was confirmed in analyses of eight of nine secondary cohorts. In one cohort (patients requiring vasopressors), AC use was associated with an 8% increase in the odds of death. More blood transfusions were administered in the AC group, although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

Despite the rigorous and complex statistical analysis used in this study, residual confounders remained. It is still possible, but unlikely, that patients with an AC could have had a higher expected mortality, which the use of the AC ameliorated. This study raises an important question that should ideally be addressed by randomized trials.

Bottom line: Arterial catheters used in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU are not associated with lower mortality and should therefore be used with caution, weighing the risks and benefits, until more studies are performed.

Bedside Attention Tests May Be Useful in Detecting Delirium

Clinical question: Are simple bedside attention tests a reliable way to routinely screen for delirium?

Background: Early diagnosis of delirium decreases adverse outcomes, but it often goes unrecognized, in part because clinicians do not routinely screen for it. Patients at high risk of delirium should be assessed regularly, although the best brief screening method is unknown. For example, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) requires training and is time-consuming to administer.

Study design: Cross-sectional portion of a larger point prevalence study.

Setting: Adult inpatients in a large university hospital in Ireland.

Synopsis: The study population (265 adult inpatients) was screened for inattention using months of the year backwards (MOTYB) and Spatial Span Forwards (SSF), a visual pattern recognition test. In addition, subjective/objective reports of confusion were gathered by interviewing patients and nurses and by reviewing physician documentation. Any patient who failed at least one of the screening tests or had reports of confusion was administered the CAM and then evaluated by a team of psychiatrists experienced in delirium detection.

Combining MOTYB with assessment of objective/subjective reports of delirium was the most accurate way to screen for delirium (sensitivity 93.8%, specificity 84.7%). In older patients (>69 years), MOTYB by itself was the most accurate. Addition of the CAM as a second-line screening test increased specificity but led to an unacceptable drop in sensitivity.

Hospitalists can easily incorporate the MOTYB test into daily patient assessments to help identify delirious patients but should be mindful of this study’s limitations (involved patients at a single institution, included assessment of only two bedside tests for attention, and completed formal delirium testing only in patients who screened positive).

Bottom line: Simple attention tests, particularly MOTYB, could be useful in increasing recognition of delirium among adult inpatients.

Clinical question: Are simple bedside attention tests a reliable way to routinely screen for delirium?

Background: Early diagnosis of delirium decreases adverse outcomes, but it often goes unrecognized, in part because clinicians do not routinely screen for it. Patients at high risk of delirium should be assessed regularly, although the best brief screening method is unknown. For example, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) requires training and is time-consuming to administer.

Study design: Cross-sectional portion of a larger point prevalence study.

Setting: Adult inpatients in a large university hospital in Ireland.

Synopsis: The study population (265 adult inpatients) was screened for inattention using months of the year backwards (MOTYB) and Spatial Span Forwards (SSF), a visual pattern recognition test. In addition, subjective/objective reports of confusion were gathered by interviewing patients and nurses and by reviewing physician documentation. Any patient who failed at least one of the screening tests or had reports of confusion was administered the CAM and then evaluated by a team of psychiatrists experienced in delirium detection.

Combining MOTYB with assessment of objective/subjective reports of delirium was the most accurate way to screen for delirium (sensitivity 93.8%, specificity 84.7%). In older patients (>69 years), MOTYB by itself was the most accurate. Addition of the CAM as a second-line screening test increased specificity but led to an unacceptable drop in sensitivity.

Hospitalists can easily incorporate the MOTYB test into daily patient assessments to help identify delirious patients but should be mindful of this study’s limitations (involved patients at a single institution, included assessment of only two bedside tests for attention, and completed formal delirium testing only in patients who screened positive).

Bottom line: Simple attention tests, particularly MOTYB, could be useful in increasing recognition of delirium among adult inpatients.

Clinical question: Are simple bedside attention tests a reliable way to routinely screen for delirium?

Background: Early diagnosis of delirium decreases adverse outcomes, but it often goes unrecognized, in part because clinicians do not routinely screen for it. Patients at high risk of delirium should be assessed regularly, although the best brief screening method is unknown. For example, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) requires training and is time-consuming to administer.

Study design: Cross-sectional portion of a larger point prevalence study.

Setting: Adult inpatients in a large university hospital in Ireland.

Synopsis: The study population (265 adult inpatients) was screened for inattention using months of the year backwards (MOTYB) and Spatial Span Forwards (SSF), a visual pattern recognition test. In addition, subjective/objective reports of confusion were gathered by interviewing patients and nurses and by reviewing physician documentation. Any patient who failed at least one of the screening tests or had reports of confusion was administered the CAM and then evaluated by a team of psychiatrists experienced in delirium detection.

Combining MOTYB with assessment of objective/subjective reports of delirium was the most accurate way to screen for delirium (sensitivity 93.8%, specificity 84.7%). In older patients (>69 years), MOTYB by itself was the most accurate. Addition of the CAM as a second-line screening test increased specificity but led to an unacceptable drop in sensitivity.

Hospitalists can easily incorporate the MOTYB test into daily patient assessments to help identify delirious patients but should be mindful of this study’s limitations (involved patients at a single institution, included assessment of only two bedside tests for attention, and completed formal delirium testing only in patients who screened positive).

Bottom line: Simple attention tests, particularly MOTYB, could be useful in increasing recognition of delirium among adult inpatients.

What Should Hospitalists Know about Transarterial Liver Tumor Therapies?

Case

A 51-year-old male with known hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recently underwent successful transarterial chemoembolization of a segment VII liver lesion. The patient was admitted to the hospitalist service for overnight observation. Soon after being sent to the floor, he developed a large mass in his right groin, with associated erythema and tenderness. Upon examination, the radiology resident on call found a 3-cm round red hematoma near the arterial puncture site.

Manual pressure was reapplied for 15 minutes, and the mass was circled with a marker. The patient was monitored for an additional day in the hospital with serial blood counts that were stable. Prior to discharge, the hematoma was 1 cm and disappeared by his follow-up, five days later.

Current State of Liver Malignancies

Liver malignancies have increased in incidence over the last decade, from 7.1 to 8.4 per 100,000 people.1 HCC is the most common form of primary liver cancer, with more than one million new cases worldwide each year. While generally more prevalent in countries where hepatitis B is endemic (i.e., China and sub-Saharan Africa), prevalence is increasing in the United States and Europe due to chronic hepatitis C, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and alcoholic cirrhosis. HCC traditionally has had few treatment options, with surgical resection or liver transplantation providing the only potential cures; however, only a minority of patients (10%-15%) are surgical candidates.2,3

Similarly, liver metastasis due to cancers from the gastrointestinal tract and breast are on the rise in developing and developed countries. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimates that approximately 50% of patients with colon cancer will have liver metastases at some point in the course of their disease, and only a small number of patients will be candidates for surgical resection.4

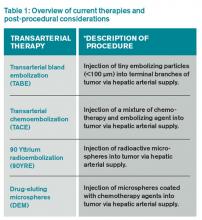

In light of the limited treatment options for liver malignancies, alternative treatments continue to be an area of intense research, namely transarterial therapies, the most common of which are briefly described in Table 1.

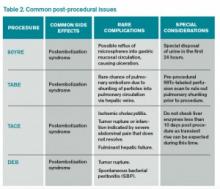

Puncture Site Complications

Hematoma. Puncture site hematoma is the most common complication of arterial access, with an estimated incidence of 5%-23%.5 The main clinical findings are erythema and swelling at the puncture site, with a palpable hardening of the skin. Pain and decreased range of motion in the affected extremity are common. Severe cases can result in hypotension and tachycardia with an acute drop in hemoglobin. Initial management will involve marking the site to evaluate for change in size as well as applying pressure. Patients should remain in bed, and serial blood counts should be monitored. Simple hematomas may resolve with time; however, more severe cases may require surgical intervention.6,7

Pseudoaneurysm formation. The incidence of pseudoaneurysm after arterial puncture is 0.5%-9%. These primarily arise from difficulty with cannulation of the artery and inadequate compression after vascular sheath removal. Signs of pseudoaneurysm are similar to those associated with hematoma; however, these will present with a palpable thrill or possibly a bruit on auscultation. Ultrasound is used for diagnosis. As with hematoma, bed rest and close monitoring are important. More severe cases may require surgical intervention or thrombin injection.5,8

Infection: Puncture site infection is rare, with incidence around 1%. Pain, swelling, and erythema, in combination with fever and leukocytosis, should raise suspicion for infection. Treatment typically involves antibiotics.

Nerve damage: Another rare occurrence is damage to surrounding nerves when performing initial puncture or post-procedural compression. The incidence of nerve damage is <0.5%, and symptoms include numbness and tingling at the access site, along with limb weakness. Treatment involves symptomatic management and physical therapy. Nerve damage may also arise secondary to nerve sheath compression from a hematoma.5,9

Thrombosis of the artery. Arterial thrombosis can occur at the site of sheath entry; however, this can be avoided by administering anticoagulation during the procedure. Classic symptoms include the “5 P’s”: pain, pallor, parasthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. Treatment depends on clot burden, with small clots potentially dissolving and larger clots requiring possible thrombolysis, embolectomy, or surgery.5,10

Systemic Considerations

Postembolization syndrome: This syndrome is characterized by fever, leukocytosis, and pain; while not a true complication, this issue must be addressed, as it is an expected event in post-procedural care. The reported incidence is as high as 90%-95%, with 81% of patients reporting nausea, vomiting, malaise, and myalgias; 42% experience low-grade fever. Typically, the symptoms peak around five days post-procedure and last about 10 days. Although this syndrome is mostly self-limited, it is important to rule out concurrent infection in patients with prolonged symptoms and/or fever outside of the expected time frame.11

Delayed hypersensitivity to contrast. Contrast reactions can occur anywhere from one hour to seven days after administration. The most common symptoms are pruritis, maculopapular rash, and urticaria; however, more severe reactions may involve respiratory distress and cardiovascular collapse.

Risk factors for delayed reactions include prior contrast reaction, history of drug allergy, and chronic renal impairment. Ideally, high risk patients should avoid contrast medium, if possible; if contrast is necessary, premedication should be provided.

For treatment of a delayed reaction, use the patient’s symptoms as a guide on how to proceed. If the reaction is mild (pruritis or rash), secure IV access, have oxygen on standby, begin IV fluids, and consider administering diphenhydramine 50 mg IV or PO. Hydrocortisone 200 mg IV can be substituted if the patient has a diphenhydramine allergy. In severe reactions, epinephrine (1:1,000 IM or 1:10,000 IV) should be administered immediately.

Hypersensitivity to embolizing agents. Frequently in chemoembolization, iodized oil is used both as contrast and as an occluding agent. This lipiodol suspension is combined with the chemotherapy drug of choice and injected into the vessel of interest. The most common hypersensitivity reaction experienced with this technique is dyspnea. Patients also can experience pruritis, urticaria, bronchospasm, or altered mental status in lower frequencies.

One study showed a 3.2% occurrence of hypersensitivity to the frequently used combination of lipiodol and cisplatin.12 The most common reactions were dyspnea and urticaria (observed in 57% of patients); bronchospasm, altered mental status, and pruritus were observed in lower frequencies. Treatment involves corticosteroids and antihistamines, with blood pressure support using vasopressors as needed.12

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN). CIN is defined as a 25% rise in serum creatinine from baseline after exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Patients particularly at risk for this complication include those with preexisting renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or acute renal failure due to dehydration. Other risk factors include age, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and hepatic impairment. Prophylactic strategies primarily rely on intravenous hydration prior to exposure. The use of N-acetylcysteine can be considered; however, its effectiveness is controversial and it is not routinely recommended.13,14

Bottom Line

Transarterial liver tumor therapies offer treatment options to patients who would otherwise have none. With these presented considerations in mind, the hospitalist will be prepared to address common issues when and if they arise.

Drs. Sandeep and Archana Laroia are clinical assistant professors in the department of radiology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. Dr. Morales is a radiology resident at UIHC.

References

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- Llovet JM. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7(6):431-441.

- Sasson AR, Sigurdson ER. Surgical treatment of liver metastases. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(2):107-118.

- National Cancer Institute. Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ). Available at: http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/colon/HealthProfessional. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- Merriweather N, Sulzbach-Hoke LM. Managing risk of complications at femoral vascular access sites in percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(5):16-29.

- Sigstedt B, Lunderquist A. Complications of angiographic examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;130(3):455-460.

- Clark TW. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):119-125.

- Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674.

- Tran DD, Andersen CA. Axillary sheath hematomas causing neurologic complications following arterial access. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(5):697 e5-8.

- Hall R. Vascular injuries resulting from arterial puncture of catheterization. Br J Surg. 1971;58(7):513-516.

- Leung DA, Goin JE, Sickles C, Raskay BJ, Soulen MC. Determinants of postembolization syndrome after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(3):321-326.

- Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Katamura Y, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to transcatheter chemoembolization with cisplatin and Lipiodol suspension for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(8):1219-1225.

- Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced by contrast medium. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):379-386.

- McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, et al. Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6A):27K-36K.

Case

A 51-year-old male with known hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recently underwent successful transarterial chemoembolization of a segment VII liver lesion. The patient was admitted to the hospitalist service for overnight observation. Soon after being sent to the floor, he developed a large mass in his right groin, with associated erythema and tenderness. Upon examination, the radiology resident on call found a 3-cm round red hematoma near the arterial puncture site.

Manual pressure was reapplied for 15 minutes, and the mass was circled with a marker. The patient was monitored for an additional day in the hospital with serial blood counts that were stable. Prior to discharge, the hematoma was 1 cm and disappeared by his follow-up, five days later.

Current State of Liver Malignancies

Liver malignancies have increased in incidence over the last decade, from 7.1 to 8.4 per 100,000 people.1 HCC is the most common form of primary liver cancer, with more than one million new cases worldwide each year. While generally more prevalent in countries where hepatitis B is endemic (i.e., China and sub-Saharan Africa), prevalence is increasing in the United States and Europe due to chronic hepatitis C, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and alcoholic cirrhosis. HCC traditionally has had few treatment options, with surgical resection or liver transplantation providing the only potential cures; however, only a minority of patients (10%-15%) are surgical candidates.2,3

Similarly, liver metastasis due to cancers from the gastrointestinal tract and breast are on the rise in developing and developed countries. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimates that approximately 50% of patients with colon cancer will have liver metastases at some point in the course of their disease, and only a small number of patients will be candidates for surgical resection.4

In light of the limited treatment options for liver malignancies, alternative treatments continue to be an area of intense research, namely transarterial therapies, the most common of which are briefly described in Table 1.

Puncture Site Complications

Hematoma. Puncture site hematoma is the most common complication of arterial access, with an estimated incidence of 5%-23%.5 The main clinical findings are erythema and swelling at the puncture site, with a palpable hardening of the skin. Pain and decreased range of motion in the affected extremity are common. Severe cases can result in hypotension and tachycardia with an acute drop in hemoglobin. Initial management will involve marking the site to evaluate for change in size as well as applying pressure. Patients should remain in bed, and serial blood counts should be monitored. Simple hematomas may resolve with time; however, more severe cases may require surgical intervention.6,7

Pseudoaneurysm formation. The incidence of pseudoaneurysm after arterial puncture is 0.5%-9%. These primarily arise from difficulty with cannulation of the artery and inadequate compression after vascular sheath removal. Signs of pseudoaneurysm are similar to those associated with hematoma; however, these will present with a palpable thrill or possibly a bruit on auscultation. Ultrasound is used for diagnosis. As with hematoma, bed rest and close monitoring are important. More severe cases may require surgical intervention or thrombin injection.5,8

Infection: Puncture site infection is rare, with incidence around 1%. Pain, swelling, and erythema, in combination with fever and leukocytosis, should raise suspicion for infection. Treatment typically involves antibiotics.

Nerve damage: Another rare occurrence is damage to surrounding nerves when performing initial puncture or post-procedural compression. The incidence of nerve damage is <0.5%, and symptoms include numbness and tingling at the access site, along with limb weakness. Treatment involves symptomatic management and physical therapy. Nerve damage may also arise secondary to nerve sheath compression from a hematoma.5,9

Thrombosis of the artery. Arterial thrombosis can occur at the site of sheath entry; however, this can be avoided by administering anticoagulation during the procedure. Classic symptoms include the “5 P’s”: pain, pallor, parasthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. Treatment depends on clot burden, with small clots potentially dissolving and larger clots requiring possible thrombolysis, embolectomy, or surgery.5,10

Systemic Considerations

Postembolization syndrome: This syndrome is characterized by fever, leukocytosis, and pain; while not a true complication, this issue must be addressed, as it is an expected event in post-procedural care. The reported incidence is as high as 90%-95%, with 81% of patients reporting nausea, vomiting, malaise, and myalgias; 42% experience low-grade fever. Typically, the symptoms peak around five days post-procedure and last about 10 days. Although this syndrome is mostly self-limited, it is important to rule out concurrent infection in patients with prolonged symptoms and/or fever outside of the expected time frame.11

Delayed hypersensitivity to contrast. Contrast reactions can occur anywhere from one hour to seven days after administration. The most common symptoms are pruritis, maculopapular rash, and urticaria; however, more severe reactions may involve respiratory distress and cardiovascular collapse.

Risk factors for delayed reactions include prior contrast reaction, history of drug allergy, and chronic renal impairment. Ideally, high risk patients should avoid contrast medium, if possible; if contrast is necessary, premedication should be provided.

For treatment of a delayed reaction, use the patient’s symptoms as a guide on how to proceed. If the reaction is mild (pruritis or rash), secure IV access, have oxygen on standby, begin IV fluids, and consider administering diphenhydramine 50 mg IV or PO. Hydrocortisone 200 mg IV can be substituted if the patient has a diphenhydramine allergy. In severe reactions, epinephrine (1:1,000 IM or 1:10,000 IV) should be administered immediately.

Hypersensitivity to embolizing agents. Frequently in chemoembolization, iodized oil is used both as contrast and as an occluding agent. This lipiodol suspension is combined with the chemotherapy drug of choice and injected into the vessel of interest. The most common hypersensitivity reaction experienced with this technique is dyspnea. Patients also can experience pruritis, urticaria, bronchospasm, or altered mental status in lower frequencies.

One study showed a 3.2% occurrence of hypersensitivity to the frequently used combination of lipiodol and cisplatin.12 The most common reactions were dyspnea and urticaria (observed in 57% of patients); bronchospasm, altered mental status, and pruritus were observed in lower frequencies. Treatment involves corticosteroids and antihistamines, with blood pressure support using vasopressors as needed.12

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN). CIN is defined as a 25% rise in serum creatinine from baseline after exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Patients particularly at risk for this complication include those with preexisting renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or acute renal failure due to dehydration. Other risk factors include age, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and hepatic impairment. Prophylactic strategies primarily rely on intravenous hydration prior to exposure. The use of N-acetylcysteine can be considered; however, its effectiveness is controversial and it is not routinely recommended.13,14

Bottom Line

Transarterial liver tumor therapies offer treatment options to patients who would otherwise have none. With these presented considerations in mind, the hospitalist will be prepared to address common issues when and if they arise.

Drs. Sandeep and Archana Laroia are clinical assistant professors in the department of radiology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. Dr. Morales is a radiology resident at UIHC.

References

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- Llovet JM. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7(6):431-441.

- Sasson AR, Sigurdson ER. Surgical treatment of liver metastases. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(2):107-118.

- National Cancer Institute. Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ). Available at: http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/colon/HealthProfessional. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- Merriweather N, Sulzbach-Hoke LM. Managing risk of complications at femoral vascular access sites in percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(5):16-29.

- Sigstedt B, Lunderquist A. Complications of angiographic examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;130(3):455-460.

- Clark TW. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):119-125.

- Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674.

- Tran DD, Andersen CA. Axillary sheath hematomas causing neurologic complications following arterial access. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(5):697 e5-8.

- Hall R. Vascular injuries resulting from arterial puncture of catheterization. Br J Surg. 1971;58(7):513-516.

- Leung DA, Goin JE, Sickles C, Raskay BJ, Soulen MC. Determinants of postembolization syndrome after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(3):321-326.

- Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Katamura Y, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to transcatheter chemoembolization with cisplatin and Lipiodol suspension for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(8):1219-1225.

- Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced by contrast medium. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):379-386.

- McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, et al. Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6A):27K-36K.

Case

A 51-year-old male with known hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recently underwent successful transarterial chemoembolization of a segment VII liver lesion. The patient was admitted to the hospitalist service for overnight observation. Soon after being sent to the floor, he developed a large mass in his right groin, with associated erythema and tenderness. Upon examination, the radiology resident on call found a 3-cm round red hematoma near the arterial puncture site.

Manual pressure was reapplied for 15 minutes, and the mass was circled with a marker. The patient was monitored for an additional day in the hospital with serial blood counts that were stable. Prior to discharge, the hematoma was 1 cm and disappeared by his follow-up, five days later.

Current State of Liver Malignancies

Liver malignancies have increased in incidence over the last decade, from 7.1 to 8.4 per 100,000 people.1 HCC is the most common form of primary liver cancer, with more than one million new cases worldwide each year. While generally more prevalent in countries where hepatitis B is endemic (i.e., China and sub-Saharan Africa), prevalence is increasing in the United States and Europe due to chronic hepatitis C, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and alcoholic cirrhosis. HCC traditionally has had few treatment options, with surgical resection or liver transplantation providing the only potential cures; however, only a minority of patients (10%-15%) are surgical candidates.2,3

Similarly, liver metastasis due to cancers from the gastrointestinal tract and breast are on the rise in developing and developed countries. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimates that approximately 50% of patients with colon cancer will have liver metastases at some point in the course of their disease, and only a small number of patients will be candidates for surgical resection.4

In light of the limited treatment options for liver malignancies, alternative treatments continue to be an area of intense research, namely transarterial therapies, the most common of which are briefly described in Table 1.

Puncture Site Complications

Hematoma. Puncture site hematoma is the most common complication of arterial access, with an estimated incidence of 5%-23%.5 The main clinical findings are erythema and swelling at the puncture site, with a palpable hardening of the skin. Pain and decreased range of motion in the affected extremity are common. Severe cases can result in hypotension and tachycardia with an acute drop in hemoglobin. Initial management will involve marking the site to evaluate for change in size as well as applying pressure. Patients should remain in bed, and serial blood counts should be monitored. Simple hematomas may resolve with time; however, more severe cases may require surgical intervention.6,7

Pseudoaneurysm formation. The incidence of pseudoaneurysm after arterial puncture is 0.5%-9%. These primarily arise from difficulty with cannulation of the artery and inadequate compression after vascular sheath removal. Signs of pseudoaneurysm are similar to those associated with hematoma; however, these will present with a palpable thrill or possibly a bruit on auscultation. Ultrasound is used for diagnosis. As with hematoma, bed rest and close monitoring are important. More severe cases may require surgical intervention or thrombin injection.5,8

Infection: Puncture site infection is rare, with incidence around 1%. Pain, swelling, and erythema, in combination with fever and leukocytosis, should raise suspicion for infection. Treatment typically involves antibiotics.

Nerve damage: Another rare occurrence is damage to surrounding nerves when performing initial puncture or post-procedural compression. The incidence of nerve damage is <0.5%, and symptoms include numbness and tingling at the access site, along with limb weakness. Treatment involves symptomatic management and physical therapy. Nerve damage may also arise secondary to nerve sheath compression from a hematoma.5,9

Thrombosis of the artery. Arterial thrombosis can occur at the site of sheath entry; however, this can be avoided by administering anticoagulation during the procedure. Classic symptoms include the “5 P’s”: pain, pallor, parasthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. Treatment depends on clot burden, with small clots potentially dissolving and larger clots requiring possible thrombolysis, embolectomy, or surgery.5,10

Systemic Considerations

Postembolization syndrome: This syndrome is characterized by fever, leukocytosis, and pain; while not a true complication, this issue must be addressed, as it is an expected event in post-procedural care. The reported incidence is as high as 90%-95%, with 81% of patients reporting nausea, vomiting, malaise, and myalgias; 42% experience low-grade fever. Typically, the symptoms peak around five days post-procedure and last about 10 days. Although this syndrome is mostly self-limited, it is important to rule out concurrent infection in patients with prolonged symptoms and/or fever outside of the expected time frame.11

Delayed hypersensitivity to contrast. Contrast reactions can occur anywhere from one hour to seven days after administration. The most common symptoms are pruritis, maculopapular rash, and urticaria; however, more severe reactions may involve respiratory distress and cardiovascular collapse.

Risk factors for delayed reactions include prior contrast reaction, history of drug allergy, and chronic renal impairment. Ideally, high risk patients should avoid contrast medium, if possible; if contrast is necessary, premedication should be provided.

For treatment of a delayed reaction, use the patient’s symptoms as a guide on how to proceed. If the reaction is mild (pruritis or rash), secure IV access, have oxygen on standby, begin IV fluids, and consider administering diphenhydramine 50 mg IV or PO. Hydrocortisone 200 mg IV can be substituted if the patient has a diphenhydramine allergy. In severe reactions, epinephrine (1:1,000 IM or 1:10,000 IV) should be administered immediately.

Hypersensitivity to embolizing agents. Frequently in chemoembolization, iodized oil is used both as contrast and as an occluding agent. This lipiodol suspension is combined with the chemotherapy drug of choice and injected into the vessel of interest. The most common hypersensitivity reaction experienced with this technique is dyspnea. Patients also can experience pruritis, urticaria, bronchospasm, or altered mental status in lower frequencies.

One study showed a 3.2% occurrence of hypersensitivity to the frequently used combination of lipiodol and cisplatin.12 The most common reactions were dyspnea and urticaria (observed in 57% of patients); bronchospasm, altered mental status, and pruritus were observed in lower frequencies. Treatment involves corticosteroids and antihistamines, with blood pressure support using vasopressors as needed.12

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN). CIN is defined as a 25% rise in serum creatinine from baseline after exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Patients particularly at risk for this complication include those with preexisting renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or acute renal failure due to dehydration. Other risk factors include age, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and hepatic impairment. Prophylactic strategies primarily rely on intravenous hydration prior to exposure. The use of N-acetylcysteine can be considered; however, its effectiveness is controversial and it is not routinely recommended.13,14

Bottom Line

Transarterial liver tumor therapies offer treatment options to patients who would otherwise have none. With these presented considerations in mind, the hospitalist will be prepared to address common issues when and if they arise.

Drs. Sandeep and Archana Laroia are clinical assistant professors in the department of radiology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. Dr. Morales is a radiology resident at UIHC.

References

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- Llovet JM. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7(6):431-441.

- Sasson AR, Sigurdson ER. Surgical treatment of liver metastases. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(2):107-118.

- National Cancer Institute. Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ). Available at: http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/colon/HealthProfessional. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- Merriweather N, Sulzbach-Hoke LM. Managing risk of complications at femoral vascular access sites in percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(5):16-29.

- Sigstedt B, Lunderquist A. Complications of angiographic examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;130(3):455-460.

- Clark TW. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23(2):119-125.

- Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674.

- Tran DD, Andersen CA. Axillary sheath hematomas causing neurologic complications following arterial access. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(5):697 e5-8.

- Hall R. Vascular injuries resulting from arterial puncture of catheterization. Br J Surg. 1971;58(7):513-516.

- Leung DA, Goin JE, Sickles C, Raskay BJ, Soulen MC. Determinants of postembolization syndrome after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(3):321-326.

- Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Katamura Y, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to transcatheter chemoembolization with cisplatin and Lipiodol suspension for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(8):1219-1225.

- Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced by contrast medium. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):379-386.

- McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, et al. Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6A):27K-36K.

Who Should Be Screened for HIV Infection?

Case

A 31-year-old male with a history of asthma is admitted with an asthma exacerbation. He has no regular outpatient provider. He denies tobacco use and reports that he is in a monogamous relationship with his girlfriend. On rounds, a medical student mentions that new HIV screening guidelines have been released recently and asks whether this patient should be screened for HIV.

Background

By the mid-2000s, approximately one to 1.2 million people in the United States were infected with HIV.1 Approximately one quarter of these patients are estimated to be unaware of their HIV status, and this subgroup is believed responsible for a disproportionately higher percentage of new HIV infections each year.1

While older HIV screening recommendations focused on screening patients who were deemed to be at high risk for HIV infection, there has been a paradigm change in recent years toward universal screening of all patients.2,3 The ultimate goal is for earlier identification of infected patients, which will, in turn, lead to earlier treatment and better prevention efforts.

Universal screening has been supported by a number of different professional societies and screening guidelines.4

2013 Guideline

In 2013, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations regarding HIV screening. Although the previous USPSTF guidelines (released in 2005) recommended screening patients who were believed to be at increased risk for contracting HIV, the 2013 guidelines now recommend screening all patients aged 15 to 65.4

Screening patients outside of this age range is recommended if the patient is deemed to be at increased risk for contracting HIV.4 The USPSTF provides criteria for identifying patients who are at increased risk of contracting HIV. These include:

- Men who have sex with men;

- People having unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse;

- People using injection drugs;

- People exchanging sex for drugs or money; and

- People requesting testing for other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).4

Patients are also considered to be high risk if their sexual partners are infected with HIV, are bisexual, or use injection drugs.4

The shift toward universal HIV screening has been a trend for many years, because risk-based targeting of HIV screening will miss a significant number of HIV infections.2 In fact, the 2013 recommendations bring the USPSTF guidelines into agreement with current CDC guidelines, which were released in 2006.2

The CDC, in its 2006 guidelines, recommended screening for all patients 13 to 64 years old unless HIV prevalence in the patient population has been found to be less than 0.1%, the minimum prevalence deemed necessary for HIV screening to be cost-effective.2 The CDC guidelines also recommend HIV screening for all patients starting treatment for tuberculosis, patients being screened for STDs, and patients visiting STD clinics regardless of chief complaint.2 They recommend that HIV screening be performed in an “opt-out” fashion, meaning that patients are informed that screening will be performed unless they decline.2 Furthermore, they recommend against the need for a separate written consent form for HIV screening, as well as the prior requirement that pre-screening counseling be performed, because these requirements were felt to create potential time constraint barriers that prevented providers from screening patients.2

The CDC and the USPSTF are less conclusive with regard to frequency of rescreening for HIV infection. Both recommend rescreening patients considered high risk for HIV infection, but the interval for rescreening has not been concretely defined.2,4 The guidelines urge providers to use clinical judgment in deciding when to rescreen for HIV infection.2 For example, one reason for rescreening cited by the CDC would be the initiation of a new sexual relationship.2

In the 2013 guidelines, the USPSTF also recommends screening all pregnant women, including those presenting in labor without a known HIV status.4 This stance is supported by the American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians.3 In high-risk patients with a negative screening test early in pregnancy, consideration should be given to repeat testing in the third trimester.3 Routinely screening pregnant women for HIV and starting appropriate therapy in positive patients has lowered the incidence of perinatal HIV transmission dramatically.2

Rationale

There are several reasons behind the shift to universal HIV screening, regardless of risk. First, providers often do not accurately identify patients’ HIV risk, often because patients are not aware of their actual risk or are uncomfortable discussing their high-risk behaviors with healthcare providers.2 Using risk factors as a basis of screening will miss a significant number of HIV-positive patients.4

Additionally, screening all patients will result in the detection of HIV infection in a greater number of patients during the early asymptomatic phase, rather than when they later become symptomatic from HIV or AIDS.2,4 Recent data has led the International Antiviral Society—USA Panel to issue updated recommendations advising initiation of antiretroviral therapy at all CD4 levels.5 Studies and observational data suggest that this could result in reduced AIDS complications and death rates.4

Early detection of HIV infection also has the potential of reducing spread of the virus.2,4 It has been suggested that early initiation of antiretroviral therapy could reduce risk of transmission to noninfected partners by lowering viral load in the infected patient.2 Knowledge of HIV status has also been shown to reduce high-risk behaviors.4

Moreover, by facilitating earlier detection of HIV, universal screening will allow for earlier and better counseling for infected patients.4 This has the potential to further alter behaviors and possibly reduce transmission of HIV and/or other sexually transmitted diseases.4 Additionally, routine screening of pregnant women allows for better detection of HIV-infected mothers.3 With appropriate interventions during pregnancy, including antiretroviral therapy, rates of mother-to-child transmission have decreased significantly.4

On the other hand, potential harms from HIV screening were considered during the USPSTF analysis, including risk of false positive test results, as well as the side effects of antiretroviral medications.4 Although there are known short-term and long-term side effects of antiretroviral medications, some of these side effects can be avoided by changing drug regimens.4 For many other side effects, the benefits appeared to outweigh the risks of these medications.4

Studies have also shown some potential side effects in infants exposed to antiretroviral medications, but the overall evidence is not strong.4 In the end, thorough analysis performed by the USPSTF resulted in the opinion that the benefits of HIV screening far outweigh the associated risks.4

Challenges for Hospitalists

Several potential drawbacks to universal HIV screening are relatively unique to hospitalists and other providers of hospital-based care.6 First, hospitalists must be prepared to counsel patients regarding their test results, particularly if patients are hospitalized for another issue. Second, hospitalists must be able to communicate these test results to primary care providers in a timely fashion, a challenge that is not unique to HIV testing.

The biggest concern for hospitalists is what to do with HIV test results that are still pending at the time of hospital discharge. Hospitalists will likely face this issue more as increasing numbers of patients are screened in a growing number of medical settings, including the ED and inpatient admissions. Hospitalists who plan to screen inpatients for HIV testing must ensure that these issues have been worked out prior to screening.

Back to the Case

Looking back to the initial case discussion, based on the 2006 CDC and 2013 USPSTF guidelines, this patient should be offered HIV screening if he has not been tested previously. Although the patient states that he is in a monogamous relationship and does not report any high-risk behaviors, patients often do not recognize the true risk associated with their behaviors and fail to accurately report them.2 Additionally, patients often are embarrassed by high-risk behaviors and may not report them completely to providers.2