User login

Challenging dogma: Postop fever

The dogma

During our medical school and residency years, many of us learned the “Rule of W” as a helpful mnemonic for causes of postoperative fever: Wind (pulmonary causes, including atelectasis), Water (urinary tract infection), Wound (infection), Walking (deep venous thrombosis), and Wonder Drugs (drug fever). Classic teaching has been that noninfectious causes predominate during the first 48 hours post op, with infectious diseases taking over after that. Atelectasis is also very common in the immediate postoperative period, seen in up to 90% of patients by postoperative day 3, and is often taught as the primary cause of fever in the immediate postoperative period.1,2 But is this backed up by the evidence?

The evidence

A 2011 systematic review looked at the association between atelectasis and fever. Eight studies involving 998 postoperative patients were included, with the majority of cases being postcardiac or abdominal surgeries. Seven of the eight studies failed to show a significant association between early postoperative fever (EPF) and atelectasis; in the one “positive” study, atelectasis was assessed only once on postop day 4. The authors of the review concluded that “there is no clinical evidence suggesting that atelectasis is a major cause of early EPF”.3 A subsequent study of postoperative fever in pediatric patients showed similar negative results.4 This begs the question – does atelectasis cause fever at all? Likely not. In an animal study from 1963, experimentally induced atelectasis resulted in fever, but the fever appeared secondary to infectious causes (i.e. pneumonia in the affected lung) and resolved with antibiotic administration.5 It seems more likely that EPF is due to other factors, such as the increase in pyrogenic cytokines seen in the postoperative period.3

Takeaway

Atelectasis and early postoperative fever are both commonly seen after surgery, but the relationship appears to be simply an association, not causal. The “Rule of W” can be an effective mnemonic for the causes of postop fever – just make sure you use the updated version.

Dr. Sehgal is clinical associate professor of medicine, division of hospital medicine, South Texas Veterans Health Care System and University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio. He is a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

References

1. Carter AR, et al. Thoracic Alterations After Cardiac Surgery. AJR. 1983;140(3):475-81.

2. Chu DI, Agarwal S. Postoperative Complications. In: Doherty GM. eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery, 14e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014.

3. Mavros MN, Velmahos GC, Falagas ME. Atelectasis as a Cause of Postoperative Fever. Chest. 2011;140(2):418-24. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0127.

4. Kane JM, Friedman M, Mitchell JB, Wang D, Huang Z, Backer CL. Association Between Postoperative Fever and Atelectasis in Pediatric Patients. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2011;2(3):359-63. doi: 10.1177/2150135111403778.

5. Lansing AM, Jamieson WG. Mechanisms of fever in pulmonary atelectasis. Arch Surg. 1963;87:168-74.

6. Hyder JA, Wakeam E, Arora V, Hevelone ND, Lipsitz SR, Nguyen LL. Investigating the “Rule of W,” a Mnemonic for Teaching on Postoperative Complications. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(3):430-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.11.004.

The dogma

During our medical school and residency years, many of us learned the “Rule of W” as a helpful mnemonic for causes of postoperative fever: Wind (pulmonary causes, including atelectasis), Water (urinary tract infection), Wound (infection), Walking (deep venous thrombosis), and Wonder Drugs (drug fever). Classic teaching has been that noninfectious causes predominate during the first 48 hours post op, with infectious diseases taking over after that. Atelectasis is also very common in the immediate postoperative period, seen in up to 90% of patients by postoperative day 3, and is often taught as the primary cause of fever in the immediate postoperative period.1,2 But is this backed up by the evidence?

The evidence

A 2011 systematic review looked at the association between atelectasis and fever. Eight studies involving 998 postoperative patients were included, with the majority of cases being postcardiac or abdominal surgeries. Seven of the eight studies failed to show a significant association between early postoperative fever (EPF) and atelectasis; in the one “positive” study, atelectasis was assessed only once on postop day 4. The authors of the review concluded that “there is no clinical evidence suggesting that atelectasis is a major cause of early EPF”.3 A subsequent study of postoperative fever in pediatric patients showed similar negative results.4 This begs the question – does atelectasis cause fever at all? Likely not. In an animal study from 1963, experimentally induced atelectasis resulted in fever, but the fever appeared secondary to infectious causes (i.e. pneumonia in the affected lung) and resolved with antibiotic administration.5 It seems more likely that EPF is due to other factors, such as the increase in pyrogenic cytokines seen in the postoperative period.3

Takeaway

Atelectasis and early postoperative fever are both commonly seen after surgery, but the relationship appears to be simply an association, not causal. The “Rule of W” can be an effective mnemonic for the causes of postop fever – just make sure you use the updated version.

Dr. Sehgal is clinical associate professor of medicine, division of hospital medicine, South Texas Veterans Health Care System and University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio. He is a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

References

1. Carter AR, et al. Thoracic Alterations After Cardiac Surgery. AJR. 1983;140(3):475-81.

2. Chu DI, Agarwal S. Postoperative Complications. In: Doherty GM. eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery, 14e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014.

3. Mavros MN, Velmahos GC, Falagas ME. Atelectasis as a Cause of Postoperative Fever. Chest. 2011;140(2):418-24. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0127.

4. Kane JM, Friedman M, Mitchell JB, Wang D, Huang Z, Backer CL. Association Between Postoperative Fever and Atelectasis in Pediatric Patients. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2011;2(3):359-63. doi: 10.1177/2150135111403778.

5. Lansing AM, Jamieson WG. Mechanisms of fever in pulmonary atelectasis. Arch Surg. 1963;87:168-74.

6. Hyder JA, Wakeam E, Arora V, Hevelone ND, Lipsitz SR, Nguyen LL. Investigating the “Rule of W,” a Mnemonic for Teaching on Postoperative Complications. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(3):430-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.11.004.

The dogma

During our medical school and residency years, many of us learned the “Rule of W” as a helpful mnemonic for causes of postoperative fever: Wind (pulmonary causes, including atelectasis), Water (urinary tract infection), Wound (infection), Walking (deep venous thrombosis), and Wonder Drugs (drug fever). Classic teaching has been that noninfectious causes predominate during the first 48 hours post op, with infectious diseases taking over after that. Atelectasis is also very common in the immediate postoperative period, seen in up to 90% of patients by postoperative day 3, and is often taught as the primary cause of fever in the immediate postoperative period.1,2 But is this backed up by the evidence?

The evidence

A 2011 systematic review looked at the association between atelectasis and fever. Eight studies involving 998 postoperative patients were included, with the majority of cases being postcardiac or abdominal surgeries. Seven of the eight studies failed to show a significant association between early postoperative fever (EPF) and atelectasis; in the one “positive” study, atelectasis was assessed only once on postop day 4. The authors of the review concluded that “there is no clinical evidence suggesting that atelectasis is a major cause of early EPF”.3 A subsequent study of postoperative fever in pediatric patients showed similar negative results.4 This begs the question – does atelectasis cause fever at all? Likely not. In an animal study from 1963, experimentally induced atelectasis resulted in fever, but the fever appeared secondary to infectious causes (i.e. pneumonia in the affected lung) and resolved with antibiotic administration.5 It seems more likely that EPF is due to other factors, such as the increase in pyrogenic cytokines seen in the postoperative period.3

Takeaway

Atelectasis and early postoperative fever are both commonly seen after surgery, but the relationship appears to be simply an association, not causal. The “Rule of W” can be an effective mnemonic for the causes of postop fever – just make sure you use the updated version.

Dr. Sehgal is clinical associate professor of medicine, division of hospital medicine, South Texas Veterans Health Care System and University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio. He is a member of the editorial advisory board for The Hospitalist.

References

1. Carter AR, et al. Thoracic Alterations After Cardiac Surgery. AJR. 1983;140(3):475-81.

2. Chu DI, Agarwal S. Postoperative Complications. In: Doherty GM. eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery, 14e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014.

3. Mavros MN, Velmahos GC, Falagas ME. Atelectasis as a Cause of Postoperative Fever. Chest. 2011;140(2):418-24. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0127.

4. Kane JM, Friedman M, Mitchell JB, Wang D, Huang Z, Backer CL. Association Between Postoperative Fever and Atelectasis in Pediatric Patients. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2011;2(3):359-63. doi: 10.1177/2150135111403778.

5. Lansing AM, Jamieson WG. Mechanisms of fever in pulmonary atelectasis. Arch Surg. 1963;87:168-74.

6. Hyder JA, Wakeam E, Arora V, Hevelone ND, Lipsitz SR, Nguyen LL. Investigating the “Rule of W,” a Mnemonic for Teaching on Postoperative Complications. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(3):430-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.11.004.

Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury?

SAN DIEGO – Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and those on renin angiotensin system inhibitors and/or diuretics should have their renal function monitored during periods of overanticoagulation, results from a large retrospective study suggest.

“Unfortunately, warfarin-related nephropathy is quite hard to study,” Hugh Traquair, MD, the study’s lead author, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “The best way to establish diagnosis is with a kidney biopsy. No one is very keen to stick a needle into a kidney when someone’s overanticoagulated. It’s been observed previously that acute kidney injury related to over-anticoagulation is more common in people with CKD, but we don’t know more about risk factors.”

The primary outcome was AKI, defined as an acute increase in creatinine of greater than 26.5 micromol/L within 7-14 days of an INR 4 or greater. The secondary outcome was creatinine level within 3 months of the abnormal INR. The researchers excluded patients with AKI due to another cause, and those who lacked a creatinine level at baseline, within 7-14 days of an INR of 4 or greater, and/or at 3 months.

The median age of the 292 patients was 79 years, 55% were male, 30% were taking aspirin, and 77% were taking renin angiotensin inhibitors and/or diuretics. The control group consisted of 93 patients with a 12-month time in therapeutic range of 100%. The median age of controls was 68 years, 67% were male, and 9% had CKD. None of the controls had an AKI, said Dr. Traquair, a second-year internal medicine resident in the department of medicine at McMaster University.

Of the 292 patients with an INR of 4 or greater, 13% had an AKI, and the incidence of AKI was significantly higher in the CKD patients, compared with those who had a normal baseline creatinine level (19% vs. 10%; odds ratio, 2.1; P less than .05).

In a binomial logistic regression model, diuretic use was the only significant predictor of AKI (OR 3.4; P less than .05). The researchers also found that of the 52 patients with an INR of 4 or greater who did not use renin angiotensin system inhibitors and/or diuretics and did not have CKD, only 1 had an AKI (2%).

“We don’t know that all of these episodes of AKI are related to warfarin, but we do see a definite increase of AKI after an episode of overanticoagulation (an INR greater than 4),” Dr. Traquair said. “In patients who are at risk for AKI, monitoring their kidney function after an episode of overanticoagulation is probably warranted.”

Dr. Traquair reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Traquair H et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 79.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and those on renin angiotensin system inhibitors and/or diuretics should have their renal function monitored during periods of overanticoagulation, results from a large retrospective study suggest.

“Unfortunately, warfarin-related nephropathy is quite hard to study,” Hugh Traquair, MD, the study’s lead author, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “The best way to establish diagnosis is with a kidney biopsy. No one is very keen to stick a needle into a kidney when someone’s overanticoagulated. It’s been observed previously that acute kidney injury related to over-anticoagulation is more common in people with CKD, but we don’t know more about risk factors.”

The primary outcome was AKI, defined as an acute increase in creatinine of greater than 26.5 micromol/L within 7-14 days of an INR 4 or greater. The secondary outcome was creatinine level within 3 months of the abnormal INR. The researchers excluded patients with AKI due to another cause, and those who lacked a creatinine level at baseline, within 7-14 days of an INR of 4 or greater, and/or at 3 months.

The median age of the 292 patients was 79 years, 55% were male, 30% were taking aspirin, and 77% were taking renin angiotensin inhibitors and/or diuretics. The control group consisted of 93 patients with a 12-month time in therapeutic range of 100%. The median age of controls was 68 years, 67% were male, and 9% had CKD. None of the controls had an AKI, said Dr. Traquair, a second-year internal medicine resident in the department of medicine at McMaster University.

Of the 292 patients with an INR of 4 or greater, 13% had an AKI, and the incidence of AKI was significantly higher in the CKD patients, compared with those who had a normal baseline creatinine level (19% vs. 10%; odds ratio, 2.1; P less than .05).

In a binomial logistic regression model, diuretic use was the only significant predictor of AKI (OR 3.4; P less than .05). The researchers also found that of the 52 patients with an INR of 4 or greater who did not use renin angiotensin system inhibitors and/or diuretics and did not have CKD, only 1 had an AKI (2%).

“We don’t know that all of these episodes of AKI are related to warfarin, but we do see a definite increase of AKI after an episode of overanticoagulation (an INR greater than 4),” Dr. Traquair said. “In patients who are at risk for AKI, monitoring their kidney function after an episode of overanticoagulation is probably warranted.”

Dr. Traquair reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Traquair H et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 79.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and those on renin angiotensin system inhibitors and/or diuretics should have their renal function monitored during periods of overanticoagulation, results from a large retrospective study suggest.

“Unfortunately, warfarin-related nephropathy is quite hard to study,” Hugh Traquair, MD, the study’s lead author, said in an interview at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America. “The best way to establish diagnosis is with a kidney biopsy. No one is very keen to stick a needle into a kidney when someone’s overanticoagulated. It’s been observed previously that acute kidney injury related to over-anticoagulation is more common in people with CKD, but we don’t know more about risk factors.”

The primary outcome was AKI, defined as an acute increase in creatinine of greater than 26.5 micromol/L within 7-14 days of an INR 4 or greater. The secondary outcome was creatinine level within 3 months of the abnormal INR. The researchers excluded patients with AKI due to another cause, and those who lacked a creatinine level at baseline, within 7-14 days of an INR of 4 or greater, and/or at 3 months.

The median age of the 292 patients was 79 years, 55% were male, 30% were taking aspirin, and 77% were taking renin angiotensin inhibitors and/or diuretics. The control group consisted of 93 patients with a 12-month time in therapeutic range of 100%. The median age of controls was 68 years, 67% were male, and 9% had CKD. None of the controls had an AKI, said Dr. Traquair, a second-year internal medicine resident in the department of medicine at McMaster University.

Of the 292 patients with an INR of 4 or greater, 13% had an AKI, and the incidence of AKI was significantly higher in the CKD patients, compared with those who had a normal baseline creatinine level (19% vs. 10%; odds ratio, 2.1; P less than .05).

In a binomial logistic regression model, diuretic use was the only significant predictor of AKI (OR 3.4; P less than .05). The researchers also found that of the 52 patients with an INR of 4 or greater who did not use renin angiotensin system inhibitors and/or diuretics and did not have CKD, only 1 had an AKI (2%).

“We don’t know that all of these episodes of AKI are related to warfarin, but we do see a definite increase of AKI after an episode of overanticoagulation (an INR greater than 4),” Dr. Traquair said. “In patients who are at risk for AKI, monitoring their kidney function after an episode of overanticoagulation is probably warranted.”

Dr. Traquair reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Traquair H et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 79.

REPORTING FROM THSNA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients with warfarin anticoagulation, 13% had an acute kidney injury.

Study details: A retrospective study of 292 patients with an INR of 4.0 or greater who were treated between 2007 and 2017.

Disclosures: Dr. Traquair reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Traquair H et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 79.

HM18: Tick-borne illnesses

Presenter

Andrew J. Hale, MD

University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington

Session summary

With rising temperatures from climate change, tick territory – and therefore tick-borne illnesses – are being seen with increasing frequency.

Lyme disease manifests as early-localized, early-disseminated, and late disease. The diagnosis of Lyme can be challenging and the pretest probability is key (geographic distribution, time of year, consistent symptoms). Do not send serologies unless the pretest probability is high, since the sensitivity of the test is generally low.

Concerning early-localized disease, 20% of patients will not develop the classic “bullseye” erythema migrans rash. Only 25% of patients recall even getting a tick bite. Not everyone with a rash will have a classic appearance (prepare for heterogeneity).

Neurologic symptoms can appear early or late in Lyme disease (usually weeks to months, but sometimes in days). The manifestations can include lymphocytic meningitis (which can be hard to separate from viral meningitis), radiculopathies, and cranial nerve palsies.

Lyme carditis happens early in the disseminated phase with a variety of disease (palpitations, conduction abnormalities, pericarditis, myocarditis, left ventricular failure). For those who develop a high-grade atrioventricular block, a temporary pacer may be needed; a permanent pacemaker is unnecessary because patients often do well with a course of antibiotics.

Late Lyme develops months to years after infection. It often presents as arthritis of the knee, although other large joints such as the shoulders, ankles, and elbows can also be affected. Chronic neurologic effects such as peripheral neuropathy and encephalitis can also occur.

Treatment depends on how the disease manifests. If one has arthritis or mild carditis, 28 days of doxycycline is appropriate; for neurologic disease or “bad” carditis, give ceftriaxone for 28 days; for everything else, 14-21 days of doxycycline. Amoxicillin can be used for patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline.

Borrelia miyamotoi and B. mayonii are emerging infections. Compared with Lyme, B. miyamotoi will present with more joint pain and less rash. B. mayonii has a more diffuse rash, but is otherwise similar to Lyme. Serologies for Lyme for both will be negative, but they are treated the same as Lyme disease.

Anaplasma presents as a flu-like illness and can be difficult to distinguish from Lyme. Ehrlichia is similar, but has more headache and CNS findings. Diagnosis during the first week is best with a blood smear (looking for morulae) and polymerase chain reaction; in week 2, serology is a bit better; after 3 weeks, serologies are very sensitive. Treatment for both is doxycycline for 7-14 days. Rifampin is second-line treatment, but does not treat Lyme (both can happen simultaneously).

Babesia is found in the same distribution as Lyme disease. Incubation is 1-12 weeks. Mild disease consists of parasitemia of less than 4% while severe disease is greater than 4%. Being asplenic, having HIV, receiving tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers or rituximab increases risk for severe disease. A blood smear is sufficient to diagnose Babesia, but polymerase chain reaction is also available. Treatment is atovaquone and azithromycin for 7 days for mild disease; clindamycin and quinine for 7-10 days for severe. Exchange transfusion can also be done especially for those with high parasitemia or severe symptoms.

Powassan virus is seen in the northeastern United States and the Minnesota/Wisconsin region. It has a fatality rate of 10%. About 50% of patients have long-term neurologic sequelae. Heartland virus has symptoms similar to other tick-borne illnesses, but can be associated with nausea, headache, diarrhea, myalgias, arthralgias, and renal failure. Bourbon virus also behaves like most tick-borne illnesses, but patients can develop a rapid sepsis picture.

Key takeaways for HM

- Lyme disease can be seen in inpatient settings with cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal manifestations.

- Several emerging tick-borne infections (tularemia, STARI [southern tick-associated rash illness]), relapsing fever (B. hermsii), B. miyamotoi, and B. mayonii should also be on clinicians’ radar.

- Ticks can also spread viruses that can have particularly deadly consequences such as Powassan, Heartland, and Bourbon.

- Climate change is good for ticks, but bad for humans.

Dr. Kim is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

Presenter

Andrew J. Hale, MD

University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington

Session summary

With rising temperatures from climate change, tick territory – and therefore tick-borne illnesses – are being seen with increasing frequency.

Lyme disease manifests as early-localized, early-disseminated, and late disease. The diagnosis of Lyme can be challenging and the pretest probability is key (geographic distribution, time of year, consistent symptoms). Do not send serologies unless the pretest probability is high, since the sensitivity of the test is generally low.

Concerning early-localized disease, 20% of patients will not develop the classic “bullseye” erythema migrans rash. Only 25% of patients recall even getting a tick bite. Not everyone with a rash will have a classic appearance (prepare for heterogeneity).

Neurologic symptoms can appear early or late in Lyme disease (usually weeks to months, but sometimes in days). The manifestations can include lymphocytic meningitis (which can be hard to separate from viral meningitis), radiculopathies, and cranial nerve palsies.

Lyme carditis happens early in the disseminated phase with a variety of disease (palpitations, conduction abnormalities, pericarditis, myocarditis, left ventricular failure). For those who develop a high-grade atrioventricular block, a temporary pacer may be needed; a permanent pacemaker is unnecessary because patients often do well with a course of antibiotics.

Late Lyme develops months to years after infection. It often presents as arthritis of the knee, although other large joints such as the shoulders, ankles, and elbows can also be affected. Chronic neurologic effects such as peripheral neuropathy and encephalitis can also occur.

Treatment depends on how the disease manifests. If one has arthritis or mild carditis, 28 days of doxycycline is appropriate; for neurologic disease or “bad” carditis, give ceftriaxone for 28 days; for everything else, 14-21 days of doxycycline. Amoxicillin can be used for patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline.

Borrelia miyamotoi and B. mayonii are emerging infections. Compared with Lyme, B. miyamotoi will present with more joint pain and less rash. B. mayonii has a more diffuse rash, but is otherwise similar to Lyme. Serologies for Lyme for both will be negative, but they are treated the same as Lyme disease.

Anaplasma presents as a flu-like illness and can be difficult to distinguish from Lyme. Ehrlichia is similar, but has more headache and CNS findings. Diagnosis during the first week is best with a blood smear (looking for morulae) and polymerase chain reaction; in week 2, serology is a bit better; after 3 weeks, serologies are very sensitive. Treatment for both is doxycycline for 7-14 days. Rifampin is second-line treatment, but does not treat Lyme (both can happen simultaneously).

Babesia is found in the same distribution as Lyme disease. Incubation is 1-12 weeks. Mild disease consists of parasitemia of less than 4% while severe disease is greater than 4%. Being asplenic, having HIV, receiving tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers or rituximab increases risk for severe disease. A blood smear is sufficient to diagnose Babesia, but polymerase chain reaction is also available. Treatment is atovaquone and azithromycin for 7 days for mild disease; clindamycin and quinine for 7-10 days for severe. Exchange transfusion can also be done especially for those with high parasitemia or severe symptoms.

Powassan virus is seen in the northeastern United States and the Minnesota/Wisconsin region. It has a fatality rate of 10%. About 50% of patients have long-term neurologic sequelae. Heartland virus has symptoms similar to other tick-borne illnesses, but can be associated with nausea, headache, diarrhea, myalgias, arthralgias, and renal failure. Bourbon virus also behaves like most tick-borne illnesses, but patients can develop a rapid sepsis picture.

Key takeaways for HM

- Lyme disease can be seen in inpatient settings with cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal manifestations.

- Several emerging tick-borne infections (tularemia, STARI [southern tick-associated rash illness]), relapsing fever (B. hermsii), B. miyamotoi, and B. mayonii should also be on clinicians’ radar.

- Ticks can also spread viruses that can have particularly deadly consequences such as Powassan, Heartland, and Bourbon.

- Climate change is good for ticks, but bad for humans.

Dr. Kim is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

Presenter

Andrew J. Hale, MD

University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington

Session summary

With rising temperatures from climate change, tick territory – and therefore tick-borne illnesses – are being seen with increasing frequency.

Lyme disease manifests as early-localized, early-disseminated, and late disease. The diagnosis of Lyme can be challenging and the pretest probability is key (geographic distribution, time of year, consistent symptoms). Do not send serologies unless the pretest probability is high, since the sensitivity of the test is generally low.

Concerning early-localized disease, 20% of patients will not develop the classic “bullseye” erythema migrans rash. Only 25% of patients recall even getting a tick bite. Not everyone with a rash will have a classic appearance (prepare for heterogeneity).

Neurologic symptoms can appear early or late in Lyme disease (usually weeks to months, but sometimes in days). The manifestations can include lymphocytic meningitis (which can be hard to separate from viral meningitis), radiculopathies, and cranial nerve palsies.

Lyme carditis happens early in the disseminated phase with a variety of disease (palpitations, conduction abnormalities, pericarditis, myocarditis, left ventricular failure). For those who develop a high-grade atrioventricular block, a temporary pacer may be needed; a permanent pacemaker is unnecessary because patients often do well with a course of antibiotics.

Late Lyme develops months to years after infection. It often presents as arthritis of the knee, although other large joints such as the shoulders, ankles, and elbows can also be affected. Chronic neurologic effects such as peripheral neuropathy and encephalitis can also occur.

Treatment depends on how the disease manifests. If one has arthritis or mild carditis, 28 days of doxycycline is appropriate; for neurologic disease or “bad” carditis, give ceftriaxone for 28 days; for everything else, 14-21 days of doxycycline. Amoxicillin can be used for patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline.

Borrelia miyamotoi and B. mayonii are emerging infections. Compared with Lyme, B. miyamotoi will present with more joint pain and less rash. B. mayonii has a more diffuse rash, but is otherwise similar to Lyme. Serologies for Lyme for both will be negative, but they are treated the same as Lyme disease.

Anaplasma presents as a flu-like illness and can be difficult to distinguish from Lyme. Ehrlichia is similar, but has more headache and CNS findings. Diagnosis during the first week is best with a blood smear (looking for morulae) and polymerase chain reaction; in week 2, serology is a bit better; after 3 weeks, serologies are very sensitive. Treatment for both is doxycycline for 7-14 days. Rifampin is second-line treatment, but does not treat Lyme (both can happen simultaneously).

Babesia is found in the same distribution as Lyme disease. Incubation is 1-12 weeks. Mild disease consists of parasitemia of less than 4% while severe disease is greater than 4%. Being asplenic, having HIV, receiving tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers or rituximab increases risk for severe disease. A blood smear is sufficient to diagnose Babesia, but polymerase chain reaction is also available. Treatment is atovaquone and azithromycin for 7 days for mild disease; clindamycin and quinine for 7-10 days for severe. Exchange transfusion can also be done especially for those with high parasitemia or severe symptoms.

Powassan virus is seen in the northeastern United States and the Minnesota/Wisconsin region. It has a fatality rate of 10%. About 50% of patients have long-term neurologic sequelae. Heartland virus has symptoms similar to other tick-borne illnesses, but can be associated with nausea, headache, diarrhea, myalgias, arthralgias, and renal failure. Bourbon virus also behaves like most tick-borne illnesses, but patients can develop a rapid sepsis picture.

Key takeaways for HM

- Lyme disease can be seen in inpatient settings with cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal manifestations.

- Several emerging tick-borne infections (tularemia, STARI [southern tick-associated rash illness]), relapsing fever (B. hermsii), B. miyamotoi, and B. mayonii should also be on clinicians’ radar.

- Ticks can also spread viruses that can have particularly deadly consequences such as Powassan, Heartland, and Bourbon.

- Climate change is good for ticks, but bad for humans.

Dr. Kim is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

How should asymptomatic hypertension be managed in the hospital?

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3

Other studies have examined the role of oral antihypertensives for management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Souza et al. assessed the use of oral pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency.11 Sixteen randomized clinical trials were reviewed and it was determined that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) had a superior effect in treating hypertensive urgencies.11 The most common side effect of using an ACE-I was a bad taste in patient’s mouths, and researchers did not observe side effects that were similar as those seen with the use of IV antihypertensives.11

Further, Jaker et al. performed a randomized, double-blind prospective study comparing a single dose of oral nifedipine with oral clonidine for the treatment of hypertensive urgency in 51 patients.12 Both the oral nifedipine and oral clonidine were extremely effective in reducing blood pressure fairly safely.12 However, the rapid lowering of blood pressure with oral nifedipine was concerning to Grossman et al.13 In their literature review of the side effects of oral and sublingual nifedipine, they found that it was one of the most common therapeutic interventions for hypertensive urgency or emergency.13 However, it was potentially dangerous because of the inconsistent blood pressure response after nifedipine administration, particularly with the sublingual form.13 CVAs, acute MIs, and even death were the reported adverse events with the use of oral and sublingual nifedipine.13 Because of that, the investigators recommend against the use of oral or sublingual nifedipine in hypertensive urgency or emergency and suggest using other oral antihypertensive agents instead.13

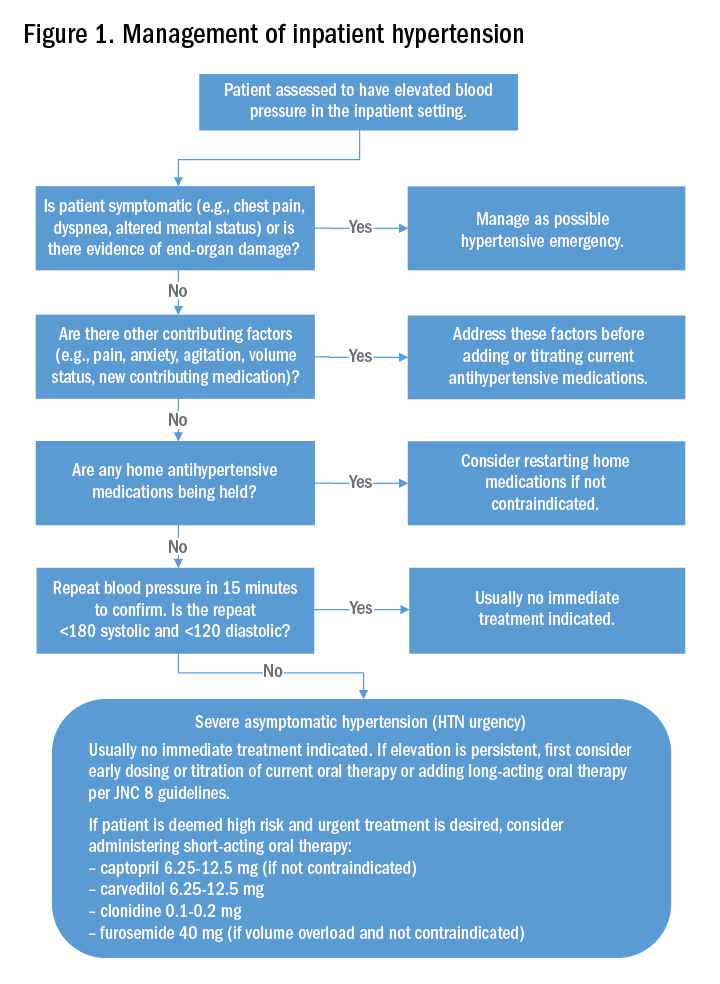

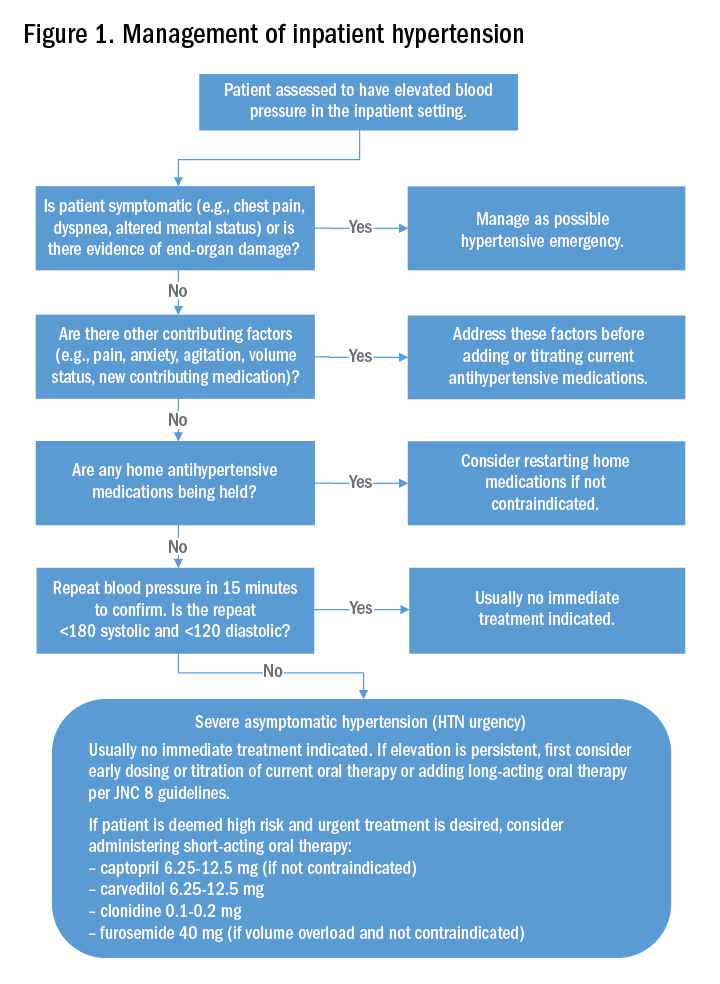

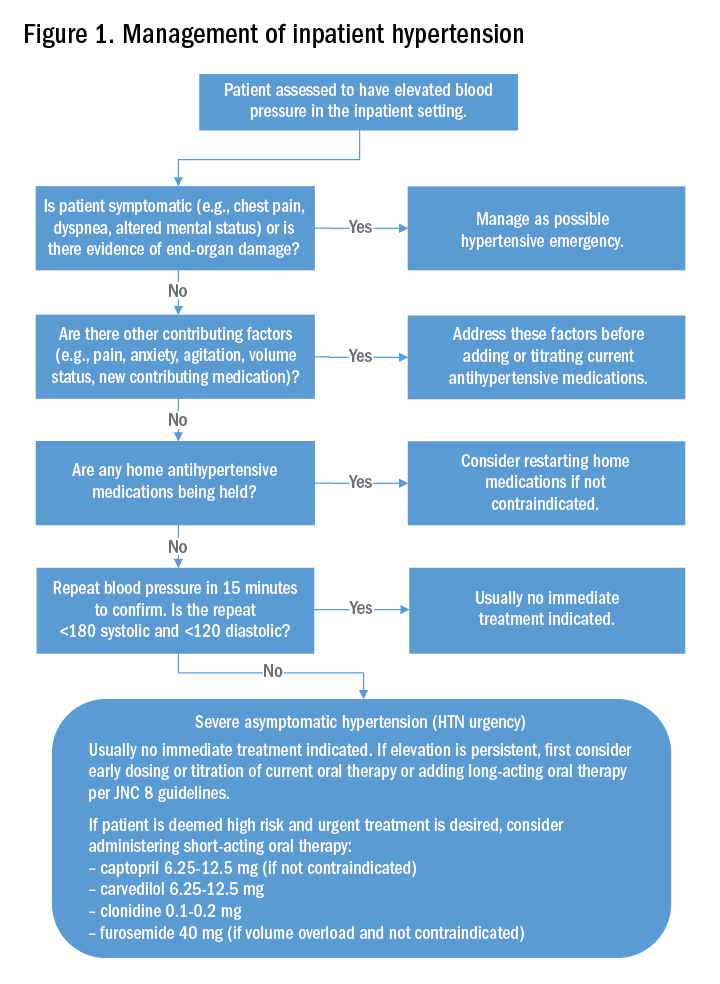

Typically, if the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite these efforts, no urgent treatment is indicated and we recommend close monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure during the hospitalization. If hypertension persists, the next best step would be to titrate a patient’s current oral antihypertensive therapy or to start a long-acting antihypertensive therapy per the JNC 8 (Eighth Joint National Committee) guidelines. It should be noted that, in those patients that are high risk, such as those with known coronary artery disease, heart failure, or prior hemorrhagic CVA, a short-acting oral antihypertensive such as captopril, carvedilol, clonidine, or furosemide should be considered.

Back to the case

The patient’s pain was treated with oral oxycodone. He received no oral or intravenous antihypertensive therapy, and the following morning, his blood pressure improved to 145/95 mm Hg. Based on our suggested approach in Fig. 1, the patient would require no acute treatment despite an improved but elevated blood pressure. We continued to monitor his blood pressure and despite adequate pain control, his blood pressure remain persistently elevated. Thus, per the JNC 8 guidelines, we started him on a long-acting antihypertensive, which improved his blood pressure to 123/78 at the time of discharge.

Bottom line

Management of asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital begins with addressing contributing factors, reviewing held home medications – and rarely – urgent oral pharmacotherapy.

Dr. Lippert is PGY-3 in the department of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Bailey is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Gray is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky.

References

1. Yoon S, Fryar C, Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. 2015. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

2. Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M. Hypertension. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):801-12.

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: Use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(1):29-33.

4. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417-22.

5. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Statistical brief; 2014 Oct. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

6. Weder AB. Treating acute hypertension in the hospital: a Lacuna in the guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):18-20.

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology. J Hypertens. 2013 Jul;31(7):1281-357.

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-20.

9. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):193-8.

10. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: Its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-7.

11. Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, et al. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(6):366-72.

12. Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, et al. Oral nifedipine vs. oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):260-5.

13. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, et al. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-31.

14. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94.

Additional Reading

1. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Nov;17(11):94.

2. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-60.

3. Sharma P, Shrestha A. Inpatient hypertension management. ACP Hospitalist. Aug 2014.

Quiz

Asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital

Hypertension is a common focus in the ambulatory setting because of its increased risk for cardiovascular events. Evidence for management in the inpatient setting is limited but does suggest a more conservative approach.

Question: A 75-year-old woman is hospitalized after sustaining a mechanical fall and subsequent right femoral neck fracture. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia for which she takes amlodipine and atorvastatin. Her blood pressure initially on admission is 170/102 mm Hg, and she is asymptomatic other than severe right hip pain. Her amlodipine and atorvastatin are resumed. Repeat blood pressures after resuming her amlodipine are still elevated with an average blood pressure reading of 168/98 mm Hg. Which of the following would be the next best step in treating this patient?

A. A one-time dose of intravenous hydralazine at 10 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

B. A one-time dose of oral clonidine at 0.1 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

C. Start a second daily antihypertensive with lisinopril 5 mg daily.

D. Address the patient’s pain.

The best answer is choice D. The patient’s hypertension is likely aggravated by her hip pain. Thus, the best course of action would be to address her pain.

Choice A is not the best answer as an intravenous antihypertensive is not indicated in this patient as she is asymptomatic and exhibiting no signs/symptoms of end-organ damage.

Choice B is not the best answer as by addressing her pain it is likely her blood pressure will improve. Urgent use of oral antihypertensives would not be indicated.

Choice C is not the best answer as patient has acute elevation of blood pressure in setting of a right femoral neck fracture and pain. Her blood pressure will likely improve after addressing her pain. However, if there is persistent blood pressure elevation, starting long-acting antihypertensive would be appropriate per JNC 8 guidelines.

Key Points

- Evidence for treatment of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is lacking.

- The use of intravenous antihypertensives in the setting of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is inappropriate and may be harmful.

- A conservative approach for inpatient asymptomatic hypertension should be employed by addressing contributing factors and reviewing held home antihypertensive medications prior to administering any oral antihypertensive pharmacotherapy.

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3

Other studies have examined the role of oral antihypertensives for management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Souza et al. assessed the use of oral pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency.11 Sixteen randomized clinical trials were reviewed and it was determined that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) had a superior effect in treating hypertensive urgencies.11 The most common side effect of using an ACE-I was a bad taste in patient’s mouths, and researchers did not observe side effects that were similar as those seen with the use of IV antihypertensives.11

Further, Jaker et al. performed a randomized, double-blind prospective study comparing a single dose of oral nifedipine with oral clonidine for the treatment of hypertensive urgency in 51 patients.12 Both the oral nifedipine and oral clonidine were extremely effective in reducing blood pressure fairly safely.12 However, the rapid lowering of blood pressure with oral nifedipine was concerning to Grossman et al.13 In their literature review of the side effects of oral and sublingual nifedipine, they found that it was one of the most common therapeutic interventions for hypertensive urgency or emergency.13 However, it was potentially dangerous because of the inconsistent blood pressure response after nifedipine administration, particularly with the sublingual form.13 CVAs, acute MIs, and even death were the reported adverse events with the use of oral and sublingual nifedipine.13 Because of that, the investigators recommend against the use of oral or sublingual nifedipine in hypertensive urgency or emergency and suggest using other oral antihypertensive agents instead.13

Typically, if the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite these efforts, no urgent treatment is indicated and we recommend close monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure during the hospitalization. If hypertension persists, the next best step would be to titrate a patient’s current oral antihypertensive therapy or to start a long-acting antihypertensive therapy per the JNC 8 (Eighth Joint National Committee) guidelines. It should be noted that, in those patients that are high risk, such as those with known coronary artery disease, heart failure, or prior hemorrhagic CVA, a short-acting oral antihypertensive such as captopril, carvedilol, clonidine, or furosemide should be considered.

Back to the case

The patient’s pain was treated with oral oxycodone. He received no oral or intravenous antihypertensive therapy, and the following morning, his blood pressure improved to 145/95 mm Hg. Based on our suggested approach in Fig. 1, the patient would require no acute treatment despite an improved but elevated blood pressure. We continued to monitor his blood pressure and despite adequate pain control, his blood pressure remain persistently elevated. Thus, per the JNC 8 guidelines, we started him on a long-acting antihypertensive, which improved his blood pressure to 123/78 at the time of discharge.

Bottom line

Management of asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital begins with addressing contributing factors, reviewing held home medications – and rarely – urgent oral pharmacotherapy.

Dr. Lippert is PGY-3 in the department of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Bailey is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Gray is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky.

References

1. Yoon S, Fryar C, Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. 2015. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

2. Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M. Hypertension. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):801-12.

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: Use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(1):29-33.

4. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417-22.

5. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Statistical brief; 2014 Oct. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

6. Weder AB. Treating acute hypertension in the hospital: a Lacuna in the guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):18-20.

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology. J Hypertens. 2013 Jul;31(7):1281-357.

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-20.

9. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):193-8.

10. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: Its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-7.

11. Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, et al. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(6):366-72.

12. Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, et al. Oral nifedipine vs. oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):260-5.

13. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, et al. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-31.

14. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94.

Additional Reading

1. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Nov;17(11):94.

2. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-60.

3. Sharma P, Shrestha A. Inpatient hypertension management. ACP Hospitalist. Aug 2014.

Quiz

Asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital

Hypertension is a common focus in the ambulatory setting because of its increased risk for cardiovascular events. Evidence for management in the inpatient setting is limited but does suggest a more conservative approach.

Question: A 75-year-old woman is hospitalized after sustaining a mechanical fall and subsequent right femoral neck fracture. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia for which she takes amlodipine and atorvastatin. Her blood pressure initially on admission is 170/102 mm Hg, and she is asymptomatic other than severe right hip pain. Her amlodipine and atorvastatin are resumed. Repeat blood pressures after resuming her amlodipine are still elevated with an average blood pressure reading of 168/98 mm Hg. Which of the following would be the next best step in treating this patient?

A. A one-time dose of intravenous hydralazine at 10 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

B. A one-time dose of oral clonidine at 0.1 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

C. Start a second daily antihypertensive with lisinopril 5 mg daily.

D. Address the patient’s pain.

The best answer is choice D. The patient’s hypertension is likely aggravated by her hip pain. Thus, the best course of action would be to address her pain.

Choice A is not the best answer as an intravenous antihypertensive is not indicated in this patient as she is asymptomatic and exhibiting no signs/symptoms of end-organ damage.

Choice B is not the best answer as by addressing her pain it is likely her blood pressure will improve. Urgent use of oral antihypertensives would not be indicated.

Choice C is not the best answer as patient has acute elevation of blood pressure in setting of a right femoral neck fracture and pain. Her blood pressure will likely improve after addressing her pain. However, if there is persistent blood pressure elevation, starting long-acting antihypertensive would be appropriate per JNC 8 guidelines.

Key Points

- Evidence for treatment of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is lacking.

- The use of intravenous antihypertensives in the setting of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is inappropriate and may be harmful.

- A conservative approach for inpatient asymptomatic hypertension should be employed by addressing contributing factors and reviewing held home antihypertensive medications prior to administering any oral antihypertensive pharmacotherapy.

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3

Other studies have examined the role of oral antihypertensives for management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Souza et al. assessed the use of oral pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency.11 Sixteen randomized clinical trials were reviewed and it was determined that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) had a superior effect in treating hypertensive urgencies.11 The most common side effect of using an ACE-I was a bad taste in patient’s mouths, and researchers did not observe side effects that were similar as those seen with the use of IV antihypertensives.11

Further, Jaker et al. performed a randomized, double-blind prospective study comparing a single dose of oral nifedipine with oral clonidine for the treatment of hypertensive urgency in 51 patients.12 Both the oral nifedipine and oral clonidine were extremely effective in reducing blood pressure fairly safely.12 However, the rapid lowering of blood pressure with oral nifedipine was concerning to Grossman et al.13 In their literature review of the side effects of oral and sublingual nifedipine, they found that it was one of the most common therapeutic interventions for hypertensive urgency or emergency.13 However, it was potentially dangerous because of the inconsistent blood pressure response after nifedipine administration, particularly with the sublingual form.13 CVAs, acute MIs, and even death were the reported adverse events with the use of oral and sublingual nifedipine.13 Because of that, the investigators recommend against the use of oral or sublingual nifedipine in hypertensive urgency or emergency and suggest using other oral antihypertensive agents instead.13

Typically, if the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite these efforts, no urgent treatment is indicated and we recommend close monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure during the hospitalization. If hypertension persists, the next best step would be to titrate a patient’s current oral antihypertensive therapy or to start a long-acting antihypertensive therapy per the JNC 8 (Eighth Joint National Committee) guidelines. It should be noted that, in those patients that are high risk, such as those with known coronary artery disease, heart failure, or prior hemorrhagic CVA, a short-acting oral antihypertensive such as captopril, carvedilol, clonidine, or furosemide should be considered.

Back to the case

The patient’s pain was treated with oral oxycodone. He received no oral or intravenous antihypertensive therapy, and the following morning, his blood pressure improved to 145/95 mm Hg. Based on our suggested approach in Fig. 1, the patient would require no acute treatment despite an improved but elevated blood pressure. We continued to monitor his blood pressure and despite adequate pain control, his blood pressure remain persistently elevated. Thus, per the JNC 8 guidelines, we started him on a long-acting antihypertensive, which improved his blood pressure to 123/78 at the time of discharge.

Bottom line

Management of asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital begins with addressing contributing factors, reviewing held home medications – and rarely – urgent oral pharmacotherapy.

Dr. Lippert is PGY-3 in the department of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Bailey is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Gray is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky.

References

1. Yoon S, Fryar C, Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. 2015. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

2. Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M. Hypertension. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):801-12.

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: Use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(1):29-33.

4. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417-22.

5. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Statistical brief; 2014 Oct. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

6. Weder AB. Treating acute hypertension in the hospital: a Lacuna in the guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):18-20.

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology. J Hypertens. 2013 Jul;31(7):1281-357.

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-20.

9. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):193-8.

10. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: Its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-7.

11. Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, et al. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(6):366-72.

12. Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, et al. Oral nifedipine vs. oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):260-5.

13. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, et al. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-31.

14. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94.

Additional Reading

1. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Nov;17(11):94.

2. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-60.

3. Sharma P, Shrestha A. Inpatient hypertension management. ACP Hospitalist. Aug 2014.

Quiz

Asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital

Hypertension is a common focus in the ambulatory setting because of its increased risk for cardiovascular events. Evidence for management in the inpatient setting is limited but does suggest a more conservative approach.

Question: A 75-year-old woman is hospitalized after sustaining a mechanical fall and subsequent right femoral neck fracture. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia for which she takes amlodipine and atorvastatin. Her blood pressure initially on admission is 170/102 mm Hg, and she is asymptomatic other than severe right hip pain. Her amlodipine and atorvastatin are resumed. Repeat blood pressures after resuming her amlodipine are still elevated with an average blood pressure reading of 168/98 mm Hg. Which of the following would be the next best step in treating this patient?

A. A one-time dose of intravenous hydralazine at 10 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

B. A one-time dose of oral clonidine at 0.1 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

C. Start a second daily antihypertensive with lisinopril 5 mg daily.

D. Address the patient’s pain.

The best answer is choice D. The patient’s hypertension is likely aggravated by her hip pain. Thus, the best course of action would be to address her pain.

Choice A is not the best answer as an intravenous antihypertensive is not indicated in this patient as she is asymptomatic and exhibiting no signs/symptoms of end-organ damage.

Choice B is not the best answer as by addressing her pain it is likely her blood pressure will improve. Urgent use of oral antihypertensives would not be indicated.

Choice C is not the best answer as patient has acute elevation of blood pressure in setting of a right femoral neck fracture and pain. Her blood pressure will likely improve after addressing her pain. However, if there is persistent blood pressure elevation, starting long-acting antihypertensive would be appropriate per JNC 8 guidelines.

Key Points

- Evidence for treatment of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is lacking.

- The use of intravenous antihypertensives in the setting of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is inappropriate and may be harmful.

- A conservative approach for inpatient asymptomatic hypertension should be employed by addressing contributing factors and reviewing held home antihypertensive medications prior to administering any oral antihypertensive pharmacotherapy.

Prompt palliative care cut hospital costs in pooled study

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

For adults with serious illness, consulting with a palliative care team within 3 days of hospital admission significantly reduced hospital costs, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

In a pooled analysis of six cohort studies, average cost savings per admission were $3,237 (95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to −$2,893) overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P values less than .001), reported Peter May, PhD, of Trinity College Dublin, and his associates.

In this latter group, prompt palliative care consultations saved more when patients had at least four comorbidities rather than two or fewer comorbidities, the reviewers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

About one in four Medicare beneficiaries dies in acute care hospitals, often after weeks of intensive, costly care that may not reflect personal wishes, according to an earlier study (JAMA. 2013;309:470-7). Economic studies have tried to pinpoint the cost savings of palliative care. These studies have found it important to consider both the clinical characteristics of patients and the amount of time between admission and palliative consultations, the reviewers noted. However, heterogeneity among older studies had precluded pooled analyses.

The six studies in this meta-analysis were identified by a search of Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, PubMed, CINAHL, and EconLit databases for economic studies of hospital-based palliative care consultations. The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and included 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease. Patients tended to be in their 60s and were usually Medicare beneficiaries, although one study focused only on Medicaid enrollees. Forty-one percent of patients had a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 93% were discharged alive. Most also had at least two comorbidities. Only 3.6% received a palliative care consultation (range, 2.2% to 22.3%).

The link that they found between more comorbidities and greater cost savings “is the reverse of prior research that assumed that long-stay, high-cost hospitalized patients could not have their care trajectories affected by palliative care,” the researchers wrote. “Current palliative care provision in the United States is characterized by widespread understaffing. Our results suggest that acute care hospitals may be able to reduce costs for this population by increasing palliative care capacity to meet national guidelines.”

Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Average cost savings per admission were $3,237 overall, $4,251 for patients with cancer, and $2,105 for patients with other serious illnesses (all P-values less than .001).

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of six cohort studies of 133,118 adults with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major organ failure, AIDS/HIV, or serious neurodegenerative disease.

Disclosures: Dr. May received grant support from The Atlantic Philanthropies. The reviewers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: May P et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0750.

Avoiding in-hospital acute kidney injury is a new imperative

NEW ORLEANS– Preventing acute kidney injury and its progression in hospitalized patients deserves to be a high priority – and now there is finally proof that it’s doable, Harold M. Szerlip, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The PrevAKI study, a recent randomized controlled clinical trial conducted by German investigators, has demonstrated that the use of renal biomarkers to identify patients at high risk for acute kidney injury (AKI) after major cardiac surgery and providing them with a range of internationally recommended supportive measures known as the KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) care bundle reduced the occurrence of moderate-to-severe AKI by 34% (Intensive Care Med. 2017 Nov;43[11]:1551-61).

The enthusiasm that greeted the PrevAKI trial findings is reflected in an editorial entitled, “AKI: the Myth of Inevitability is Finally Shattered,” by John A. Kellum, MD, professor of critical care medicine and director of the Center for Critical Care Nephrology at the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Kellum noted that the renal biomarker-based approach to implementation of the KDIGO care bundle resulted in an attractively low number needed to treat (NNT) of only 6, whereas without biomarker-based enrichment of the target population, the NNT would have been more than 33.

“,” Dr. Kellum declared in the editorial (Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017 Mar;13[3]:140-1).

Indeed, another way to do it was recently demonstrated in the SALT-ED trial, in which 13,347 noncritically ill hospitalized patients requiring intravenous fluid administration were randomized to conventional saline or balanced crystalloids. The incidence of AKI and other major adverse kidney events was 4.7% in the balanced crystalloids group, for a significant 18% risk reduction relative to the 5.6% rate with saline (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 1;378[9]:819-28).

While that absolute 0.9% risk reduction might initially not sound like much, with 35 million people per year getting IV saline while in the hospital, it translates into 315,000 fewer major adverse kidney events as a result of a simple switch to balanced crystalloids, Dr. Szerlip observed.

The PrevAKI findings validate the concept of AKI ‘golden hours’ during which time potentially reversible early kidney injury detectable via renal biomarkers is occurring prior to the abrupt decline in kidney function measured by change in serum creatinine. “The problem with using change in creatinine to define AKI is the delay in diagnosis, which makes AKI more difficult to treat,” he explained.