User login

C-reactive protein testing reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD exacerbation

, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) testing led to fewer antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, according to investigators participating in the PACE study, a multicenter, open-label trial of more than 600 patients with COPD enrolled at one of 86 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Patient-reported antibiotic use over the next 4 weeks was more than 20 percentage points lower for the group managed with the point-of-care strategy, compared with those who received usual care, according to the investigators, led by Christopher C. Butler, FMedSci, of the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford (England).

Less antibiotic use and fewer prescriptions did not compromise patient-reported, disease-specific quality of life, added Dr. Butler and colleagues. Their report appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the United States and in Europe, more than 80% of COPD patients with acute exacerbations will receive an antibiotic prescription, according to Dr. Butler and coauthors.

“Although many patients who have acute exacerbations of COPD are helped by these treatments, others are not,” wrote the investigators, noting that in one hospital-based study, about one in five such exacerbations were thought to be due to noninfectious causes.

The present study included patients at least 40 years of age who presented to a primary care practice with an acute exacerbation and at least one of the three Anthonisen criteria (increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence) intended to guide antibiotic therapy in COPD. A total of 325 were randomly assigned to the CRP testing group, and 324 to a group that received just usual care.

Antibiotic use was reported by fewer patients in the CRP testing group, compared with the usual-care group (57.0% vs. 77.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.31, 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.47), the investigators reported.

Only 47.7% of patients in the CRP-guided group received antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, vs. 69.7% of patients in the usual care group.

Hospitalizations over 6 months of follow-up were reported for 8.6% and 9.3% of patients in the CRP-guided and usual-care groups, respectively, while diagnoses of pneumonia were recorded for 3.0% and 4.0%. There was no clinically important difference between groups in the rate of antibiotic-related adverse effects.

“The evidence from our trial suggests that CRP-guided antibiotic prescribing for COPD exacerbations in primary care clinics may reduce patient-reported use of antibiotics and the prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians,” Dr. Butler and colleagues said in a discussion of these results.

Findings from the study by Dr. Butler and colleagues are “compelling enough” to support C-reactive protein (CRP) testing to guide antibiotic use in patient who have acute exacerbations of COPD, wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial.

“The trial achieved its objective, which was to show that CRP testing safely reduces antibiotic use,” stated Allan S. Brett, MD, and Majdi N. Al-Hasan, MB,BS, of the department of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Point-of-care testing of CRP could be applied even more broadly in clinical practice, Dr. Brett and Dr. Al-Hasan wrote, since testing has been shown to reduce prescribing of antibiotics for suspected lower respiratory tract infections and other common presentations in patients with no COPD.

“Whether primary care practices in the United States would embrace point-of-care CRP testing is another matter, given the regulatory requirements for in-office laboratory testing and uncertainty about reimbursement,” they noted.

Reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD likely has certain benefits, including reducing risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, according to the authors.

By contrast, the current study did not determine which COPD patients might benefit from antibiotics, if any, nor which antibiotic might be warranted for those patients.

The study was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Program of the UK National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Butler reported disclosures related to Roche Molecular Systems and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, among others.

SOURCE: Butler CC et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 10;381:111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803185.

, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) testing led to fewer antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, according to investigators participating in the PACE study, a multicenter, open-label trial of more than 600 patients with COPD enrolled at one of 86 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Patient-reported antibiotic use over the next 4 weeks was more than 20 percentage points lower for the group managed with the point-of-care strategy, compared with those who received usual care, according to the investigators, led by Christopher C. Butler, FMedSci, of the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford (England).

Less antibiotic use and fewer prescriptions did not compromise patient-reported, disease-specific quality of life, added Dr. Butler and colleagues. Their report appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the United States and in Europe, more than 80% of COPD patients with acute exacerbations will receive an antibiotic prescription, according to Dr. Butler and coauthors.

“Although many patients who have acute exacerbations of COPD are helped by these treatments, others are not,” wrote the investigators, noting that in one hospital-based study, about one in five such exacerbations were thought to be due to noninfectious causes.

The present study included patients at least 40 years of age who presented to a primary care practice with an acute exacerbation and at least one of the three Anthonisen criteria (increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence) intended to guide antibiotic therapy in COPD. A total of 325 were randomly assigned to the CRP testing group, and 324 to a group that received just usual care.

Antibiotic use was reported by fewer patients in the CRP testing group, compared with the usual-care group (57.0% vs. 77.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.31, 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.47), the investigators reported.

Only 47.7% of patients in the CRP-guided group received antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, vs. 69.7% of patients in the usual care group.

Hospitalizations over 6 months of follow-up were reported for 8.6% and 9.3% of patients in the CRP-guided and usual-care groups, respectively, while diagnoses of pneumonia were recorded for 3.0% and 4.0%. There was no clinically important difference between groups in the rate of antibiotic-related adverse effects.

“The evidence from our trial suggests that CRP-guided antibiotic prescribing for COPD exacerbations in primary care clinics may reduce patient-reported use of antibiotics and the prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians,” Dr. Butler and colleagues said in a discussion of these results.

Findings from the study by Dr. Butler and colleagues are “compelling enough” to support C-reactive protein (CRP) testing to guide antibiotic use in patient who have acute exacerbations of COPD, wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial.

“The trial achieved its objective, which was to show that CRP testing safely reduces antibiotic use,” stated Allan S. Brett, MD, and Majdi N. Al-Hasan, MB,BS, of the department of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Point-of-care testing of CRP could be applied even more broadly in clinical practice, Dr. Brett and Dr. Al-Hasan wrote, since testing has been shown to reduce prescribing of antibiotics for suspected lower respiratory tract infections and other common presentations in patients with no COPD.

“Whether primary care practices in the United States would embrace point-of-care CRP testing is another matter, given the regulatory requirements for in-office laboratory testing and uncertainty about reimbursement,” they noted.

Reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD likely has certain benefits, including reducing risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, according to the authors.

By contrast, the current study did not determine which COPD patients might benefit from antibiotics, if any, nor which antibiotic might be warranted for those patients.

The study was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Program of the UK National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Butler reported disclosures related to Roche Molecular Systems and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, among others.

SOURCE: Butler CC et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 10;381:111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803185.

, according to a recent randomized, controlled trial.

Point-of-care C-reactive protein (CRP) testing led to fewer antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, according to investigators participating in the PACE study, a multicenter, open-label trial of more than 600 patients with COPD enrolled at one of 86 general practices in the United Kingdom.

Patient-reported antibiotic use over the next 4 weeks was more than 20 percentage points lower for the group managed with the point-of-care strategy, compared with those who received usual care, according to the investigators, led by Christopher C. Butler, FMedSci, of the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford (England).

Less antibiotic use and fewer prescriptions did not compromise patient-reported, disease-specific quality of life, added Dr. Butler and colleagues. Their report appears in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the United States and in Europe, more than 80% of COPD patients with acute exacerbations will receive an antibiotic prescription, according to Dr. Butler and coauthors.

“Although many patients who have acute exacerbations of COPD are helped by these treatments, others are not,” wrote the investigators, noting that in one hospital-based study, about one in five such exacerbations were thought to be due to noninfectious causes.

The present study included patients at least 40 years of age who presented to a primary care practice with an acute exacerbation and at least one of the three Anthonisen criteria (increased dyspnea, sputum production, and sputum purulence) intended to guide antibiotic therapy in COPD. A total of 325 were randomly assigned to the CRP testing group, and 324 to a group that received just usual care.

Antibiotic use was reported by fewer patients in the CRP testing group, compared with the usual-care group (57.0% vs. 77.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.31, 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.47), the investigators reported.

Only 47.7% of patients in the CRP-guided group received antibiotic prescriptions at the initial consultation, vs. 69.7% of patients in the usual care group.

Hospitalizations over 6 months of follow-up were reported for 8.6% and 9.3% of patients in the CRP-guided and usual-care groups, respectively, while diagnoses of pneumonia were recorded for 3.0% and 4.0%. There was no clinically important difference between groups in the rate of antibiotic-related adverse effects.

“The evidence from our trial suggests that CRP-guided antibiotic prescribing for COPD exacerbations in primary care clinics may reduce patient-reported use of antibiotics and the prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians,” Dr. Butler and colleagues said in a discussion of these results.

Findings from the study by Dr. Butler and colleagues are “compelling enough” to support C-reactive protein (CRP) testing to guide antibiotic use in patient who have acute exacerbations of COPD, wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial.

“The trial achieved its objective, which was to show that CRP testing safely reduces antibiotic use,” stated Allan S. Brett, MD, and Majdi N. Al-Hasan, MB,BS, of the department of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Point-of-care testing of CRP could be applied even more broadly in clinical practice, Dr. Brett and Dr. Al-Hasan wrote, since testing has been shown to reduce prescribing of antibiotics for suspected lower respiratory tract infections and other common presentations in patients with no COPD.

“Whether primary care practices in the United States would embrace point-of-care CRP testing is another matter, given the regulatory requirements for in-office laboratory testing and uncertainty about reimbursement,” they noted.

Reduced antibiotic prescribing in patients with COPD likely has certain benefits, including reducing risk of Clostridioides difficile colitis, according to the authors.

By contrast, the current study did not determine which COPD patients might benefit from antibiotics, if any, nor which antibiotic might be warranted for those patients.

The study was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Program of the UK National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Butler reported disclosures related to Roche Molecular Systems and Roche Molecular Diagnostics, among others.

SOURCE: Butler CC et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 10;381:111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803185.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Higher omega-3 fatty acid levels cut heart failure risk

Higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, were associated with a significantly reduced risk of heart failure in a large, multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States.

Despite the potential benefits of omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for heart health, their use has been controversial, although data in a mouse model showed that dietary EPA was protective against heart failure, wrote Robert C. Block, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and colleagues. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To examine the impact of EPA on heart failure in humans, the researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults, including those who are African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white.

The researchers included 6,562 MESA participants aged 45-84 years from six communities. Participants underwent a baseline exam between July 2000 and July 2002 that included phospholipid measurements used to identify plasma EPA percentage, and they completed study visits approximately every other year for a median follow-up of 13 years.

A total of 292 heart failure events occurred during the follow-up period: 128 with reduced ejection fraction (EF less than 45%), 110 with preserved ejection fraction (EF at least 45%), and 54 with unknown EF status.

The percent EPA for individuals without heart failure was significantly higher compared with those with heart failure (0.76% vs. 0.69%, P =.005). The association remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, lipids and lipid-lowering drugs, albuminuria, and the lead fatty acid (defined as the fatty acid with the largest in-cluster correlation).

An EPA level greater than 2.5% was considered sufficient to prevent heart failure based on prior definitions. A total of 73% of the participants had insufficient EPA (less than 1.0%), 2.4% had marginal levels (1.0%-2.5%), and 4.5% had sufficient levels. However, given that EPA levels can be easily and safely increased with the consumption of seafood or fish oil capsules, increasing EPA is a feasible heart failure prevention strategy, the researchers said.

The study included 2,532 white, 1,794 black, 1,442 Hispanic, and 794 Chinese participants. Overall, the fewest Hispanic participants met the criteria for sufficient EPA (1.4%), followed by black (4.4%), white (4.9%), and Chinese participants (9.8%).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including relatively few participants with preserved ejection fractions and sufficient EPA levels, as well as the inability to account for changes in omega-3 levels and other risk factors over time, the researchers noted.

“We consider this study to strongly determine a benefit of EPA exists, but insufficient to determine whether a threshold for %EPA exists near 3%,” they said. They proposed a follow-up study including individuals with higher levels of EPA to better detect a protective effect.

Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The study findings suggest that revisiting omega-3 fatty acids to improve outcomes in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease may be worthwhile. Not only did the study predict heart failure in a range of ethnicities, but the same authors showed previously in animal models that these dietary supplements can preserve left ventricular function and reduce interstitial fibrosis.

The question is: Is it sufficient to give dietary recommendations of an increased fish consumption, or do we need to take purified pharmaceutical supplements such as those tested in trials? In other words, shall we have to go to the fish market or to the pharmacy to elevate our circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids and, in this way, to try to prevent (or treat) HF?

The answer, at least in part, lies in additional large, randomized clinical trials that test high doses of omega-3 fatty acids along and combined with pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. Considering the very favorable tolerability and safety profile of this therapeutic approach, any positive results of these trials could provide us with an additional strategy to improve the outcomes of patients with HF or at high risk to develop it.

Aldo P. Maggioni, MD, of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation, in Florence, Italy, made these remarks in an editorial. He disclosed honoraria for participation in committees of studies sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Fresenius.

The study findings suggest that revisiting omega-3 fatty acids to improve outcomes in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease may be worthwhile. Not only did the study predict heart failure in a range of ethnicities, but the same authors showed previously in animal models that these dietary supplements can preserve left ventricular function and reduce interstitial fibrosis.

The question is: Is it sufficient to give dietary recommendations of an increased fish consumption, or do we need to take purified pharmaceutical supplements such as those tested in trials? In other words, shall we have to go to the fish market or to the pharmacy to elevate our circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids and, in this way, to try to prevent (or treat) HF?

The answer, at least in part, lies in additional large, randomized clinical trials that test high doses of omega-3 fatty acids along and combined with pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. Considering the very favorable tolerability and safety profile of this therapeutic approach, any positive results of these trials could provide us with an additional strategy to improve the outcomes of patients with HF or at high risk to develop it.

Aldo P. Maggioni, MD, of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation, in Florence, Italy, made these remarks in an editorial. He disclosed honoraria for participation in committees of studies sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Fresenius.

The study findings suggest that revisiting omega-3 fatty acids to improve outcomes in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease may be worthwhile. Not only did the study predict heart failure in a range of ethnicities, but the same authors showed previously in animal models that these dietary supplements can preserve left ventricular function and reduce interstitial fibrosis.

The question is: Is it sufficient to give dietary recommendations of an increased fish consumption, or do we need to take purified pharmaceutical supplements such as those tested in trials? In other words, shall we have to go to the fish market or to the pharmacy to elevate our circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids and, in this way, to try to prevent (or treat) HF?

The answer, at least in part, lies in additional large, randomized clinical trials that test high doses of omega-3 fatty acids along and combined with pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. Considering the very favorable tolerability and safety profile of this therapeutic approach, any positive results of these trials could provide us with an additional strategy to improve the outcomes of patients with HF or at high risk to develop it.

Aldo P. Maggioni, MD, of the ANMCO Research Center Heart Care Foundation, in Florence, Italy, made these remarks in an editorial. He disclosed honoraria for participation in committees of studies sponsored by Bayer, Novartis, and Fresenius.

Higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, were associated with a significantly reduced risk of heart failure in a large, multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States.

Despite the potential benefits of omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for heart health, their use has been controversial, although data in a mouse model showed that dietary EPA was protective against heart failure, wrote Robert C. Block, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and colleagues. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To examine the impact of EPA on heart failure in humans, the researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults, including those who are African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white.

The researchers included 6,562 MESA participants aged 45-84 years from six communities. Participants underwent a baseline exam between July 2000 and July 2002 that included phospholipid measurements used to identify plasma EPA percentage, and they completed study visits approximately every other year for a median follow-up of 13 years.

A total of 292 heart failure events occurred during the follow-up period: 128 with reduced ejection fraction (EF less than 45%), 110 with preserved ejection fraction (EF at least 45%), and 54 with unknown EF status.

The percent EPA for individuals without heart failure was significantly higher compared with those with heart failure (0.76% vs. 0.69%, P =.005). The association remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, lipids and lipid-lowering drugs, albuminuria, and the lead fatty acid (defined as the fatty acid with the largest in-cluster correlation).

An EPA level greater than 2.5% was considered sufficient to prevent heart failure based on prior definitions. A total of 73% of the participants had insufficient EPA (less than 1.0%), 2.4% had marginal levels (1.0%-2.5%), and 4.5% had sufficient levels. However, given that EPA levels can be easily and safely increased with the consumption of seafood or fish oil capsules, increasing EPA is a feasible heart failure prevention strategy, the researchers said.

The study included 2,532 white, 1,794 black, 1,442 Hispanic, and 794 Chinese participants. Overall, the fewest Hispanic participants met the criteria for sufficient EPA (1.4%), followed by black (4.4%), white (4.9%), and Chinese participants (9.8%).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including relatively few participants with preserved ejection fractions and sufficient EPA levels, as well as the inability to account for changes in omega-3 levels and other risk factors over time, the researchers noted.

“We consider this study to strongly determine a benefit of EPA exists, but insufficient to determine whether a threshold for %EPA exists near 3%,” they said. They proposed a follow-up study including individuals with higher levels of EPA to better detect a protective effect.

Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, were associated with a significantly reduced risk of heart failure in a large, multi-ethnic cohort of adults in the United States.

Despite the potential benefits of omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for heart health, their use has been controversial, although data in a mouse model showed that dietary EPA was protective against heart failure, wrote Robert C. Block, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and colleagues. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To examine the impact of EPA on heart failure in humans, the researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults, including those who are African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white.

The researchers included 6,562 MESA participants aged 45-84 years from six communities. Participants underwent a baseline exam between July 2000 and July 2002 that included phospholipid measurements used to identify plasma EPA percentage, and they completed study visits approximately every other year for a median follow-up of 13 years.

A total of 292 heart failure events occurred during the follow-up period: 128 with reduced ejection fraction (EF less than 45%), 110 with preserved ejection fraction (EF at least 45%), and 54 with unknown EF status.

The percent EPA for individuals without heart failure was significantly higher compared with those with heart failure (0.76% vs. 0.69%, P =.005). The association remained significant after the researchers controlled for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure, lipids and lipid-lowering drugs, albuminuria, and the lead fatty acid (defined as the fatty acid with the largest in-cluster correlation).

An EPA level greater than 2.5% was considered sufficient to prevent heart failure based on prior definitions. A total of 73% of the participants had insufficient EPA (less than 1.0%), 2.4% had marginal levels (1.0%-2.5%), and 4.5% had sufficient levels. However, given that EPA levels can be easily and safely increased with the consumption of seafood or fish oil capsules, increasing EPA is a feasible heart failure prevention strategy, the researchers said.

The study included 2,532 white, 1,794 black, 1,442 Hispanic, and 794 Chinese participants. Overall, the fewest Hispanic participants met the criteria for sufficient EPA (1.4%), followed by black (4.4%), white (4.9%), and Chinese participants (9.8%).

The study findings were limited by several factors, including relatively few participants with preserved ejection fractions and sufficient EPA levels, as well as the inability to account for changes in omega-3 levels and other risk factors over time, the researchers noted.

“We consider this study to strongly determine a benefit of EPA exists, but insufficient to determine whether a threshold for %EPA exists near 3%,” they said. They proposed a follow-up study including individuals with higher levels of EPA to better detect a protective effect.

Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

FROM JACC

Key clinical point: Adults with high levels of eicosapentaenoic acid had significantly lower risk of heart failure than did those with lower levels of EPA.

Major finding: The percent EPA was 0.76% for individuals without heart failure vs. 0.69% for those who suffered heart failure (P = .005).

Study details: An analysis of 6,562 adults aged 45-84 years in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

Disclosures: Lead author Dr. Block had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors received honoraria from Amarin Pharmaceuticals. The study was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

No reduction in PE risk with vena cava filters after severe injury

MELBOURNE – Use of a prophylactic vena cava filter to trap blood clots in severely injured patients does not appear to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism or death, according to data presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, controlled trial in which 240 severely injured patients with a contraindication to anticoagulants were randomized to receive a vena cava filter within 72 hours of admission, or no filter. The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study showed no significant differences between the filter and no-filter groups in the primary outcome of a composite of symptomatic pulmonary embolism or death from any cause at 90 days after enrollment (13.9% vs. 14.4% respectively, P = .98).

In a prespecified subgroup analysis, researchers examined patients who survived 7 days after injury and did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation in those 7 days. Among this group of patients, none of those who received the vena cava filter experienced a symptomatic pulmonary embolism between day 8 and day 90, but five patients (14.7%) in the no-filter group did.

Filters were left in place for a median duration of 27 days (11-90 days). Among the 122 patients who received a filter – which included two patients in the control group – researchers found trapped thrombi in the filter in six patients.

Transfusion requirements, and the incidence of major and nonmajor bleeding and leg deep vein thrombosis, were similar between the filter and no-filter groups. Seven patients in the filter group (5.7%) required more than one attempt to remove the filter, and in one patient the filter had to be removed surgically.

Kwok M. Ho, PhD, of the department of intensive care medicine at Royal Perth Hospital, Australia, and coauthors wrote that while vena cava filters are widely used in trauma centers to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients at high risk of bleeding, there are conflicting recommendations regarding their use, and most studies so far have been observational.

“Given the cost and risks associated with a vena cava filter, our data suggest that there is no urgency to insert the filter in patients who can be treated with prophylactic anticoagulation within 7 days after injury,” they wrote. “Unnecessary insertion of a vena cava filter has the potential to cause harm.”

However, they noted that patients with multiple, large intracranial hematomas were particularly at risk from bleeding with anticoagulant therapy, and therefore may benefit from the use of a vena cava filter.

The Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital and the Western Australian Department of Health funded the study. Dr. Ho reported funding from the Western Australian Department of Health and the Raine Medical Research Foundation to conduct the study, as well as serving as an adviser to Medtronic and Cardinal Health.

SOURCE: Ho KM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.156/NEJMoa1806515.

MELBOURNE – Use of a prophylactic vena cava filter to trap blood clots in severely injured patients does not appear to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism or death, according to data presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, controlled trial in which 240 severely injured patients with a contraindication to anticoagulants were randomized to receive a vena cava filter within 72 hours of admission, or no filter. The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study showed no significant differences between the filter and no-filter groups in the primary outcome of a composite of symptomatic pulmonary embolism or death from any cause at 90 days after enrollment (13.9% vs. 14.4% respectively, P = .98).

In a prespecified subgroup analysis, researchers examined patients who survived 7 days after injury and did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation in those 7 days. Among this group of patients, none of those who received the vena cava filter experienced a symptomatic pulmonary embolism between day 8 and day 90, but five patients (14.7%) in the no-filter group did.

Filters were left in place for a median duration of 27 days (11-90 days). Among the 122 patients who received a filter – which included two patients in the control group – researchers found trapped thrombi in the filter in six patients.

Transfusion requirements, and the incidence of major and nonmajor bleeding and leg deep vein thrombosis, were similar between the filter and no-filter groups. Seven patients in the filter group (5.7%) required more than one attempt to remove the filter, and in one patient the filter had to be removed surgically.

Kwok M. Ho, PhD, of the department of intensive care medicine at Royal Perth Hospital, Australia, and coauthors wrote that while vena cava filters are widely used in trauma centers to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients at high risk of bleeding, there are conflicting recommendations regarding their use, and most studies so far have been observational.

“Given the cost and risks associated with a vena cava filter, our data suggest that there is no urgency to insert the filter in patients who can be treated with prophylactic anticoagulation within 7 days after injury,” they wrote. “Unnecessary insertion of a vena cava filter has the potential to cause harm.”

However, they noted that patients with multiple, large intracranial hematomas were particularly at risk from bleeding with anticoagulant therapy, and therefore may benefit from the use of a vena cava filter.

The Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital and the Western Australian Department of Health funded the study. Dr. Ho reported funding from the Western Australian Department of Health and the Raine Medical Research Foundation to conduct the study, as well as serving as an adviser to Medtronic and Cardinal Health.

SOURCE: Ho KM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.156/NEJMoa1806515.

MELBOURNE – Use of a prophylactic vena cava filter to trap blood clots in severely injured patients does not appear to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism or death, according to data presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, controlled trial in which 240 severely injured patients with a contraindication to anticoagulants were randomized to receive a vena cava filter within 72 hours of admission, or no filter. The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study showed no significant differences between the filter and no-filter groups in the primary outcome of a composite of symptomatic pulmonary embolism or death from any cause at 90 days after enrollment (13.9% vs. 14.4% respectively, P = .98).

In a prespecified subgroup analysis, researchers examined patients who survived 7 days after injury and did not receive prophylactic anticoagulation in those 7 days. Among this group of patients, none of those who received the vena cava filter experienced a symptomatic pulmonary embolism between day 8 and day 90, but five patients (14.7%) in the no-filter group did.

Filters were left in place for a median duration of 27 days (11-90 days). Among the 122 patients who received a filter – which included two patients in the control group – researchers found trapped thrombi in the filter in six patients.

Transfusion requirements, and the incidence of major and nonmajor bleeding and leg deep vein thrombosis, were similar between the filter and no-filter groups. Seven patients in the filter group (5.7%) required more than one attempt to remove the filter, and in one patient the filter had to be removed surgically.

Kwok M. Ho, PhD, of the department of intensive care medicine at Royal Perth Hospital, Australia, and coauthors wrote that while vena cava filters are widely used in trauma centers to prevent pulmonary embolism in patients at high risk of bleeding, there are conflicting recommendations regarding their use, and most studies so far have been observational.

“Given the cost and risks associated with a vena cava filter, our data suggest that there is no urgency to insert the filter in patients who can be treated with prophylactic anticoagulation within 7 days after injury,” they wrote. “Unnecessary insertion of a vena cava filter has the potential to cause harm.”

However, they noted that patients with multiple, large intracranial hematomas were particularly at risk from bleeding with anticoagulant therapy, and therefore may benefit from the use of a vena cava filter.

The Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital and the Western Australian Department of Health funded the study. Dr. Ho reported funding from the Western Australian Department of Health and the Raine Medical Research Foundation to conduct the study, as well as serving as an adviser to Medtronic and Cardinal Health.

SOURCE: Ho KM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.156/NEJMoa1806515.

REPORTING FROM 2019 ISTH CONGRESS

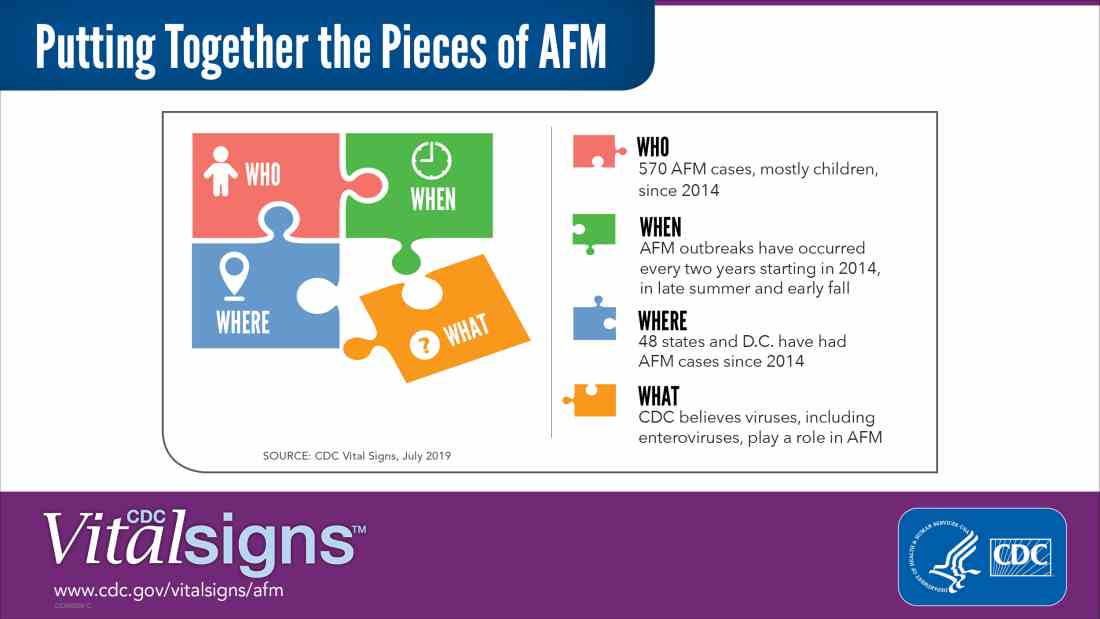

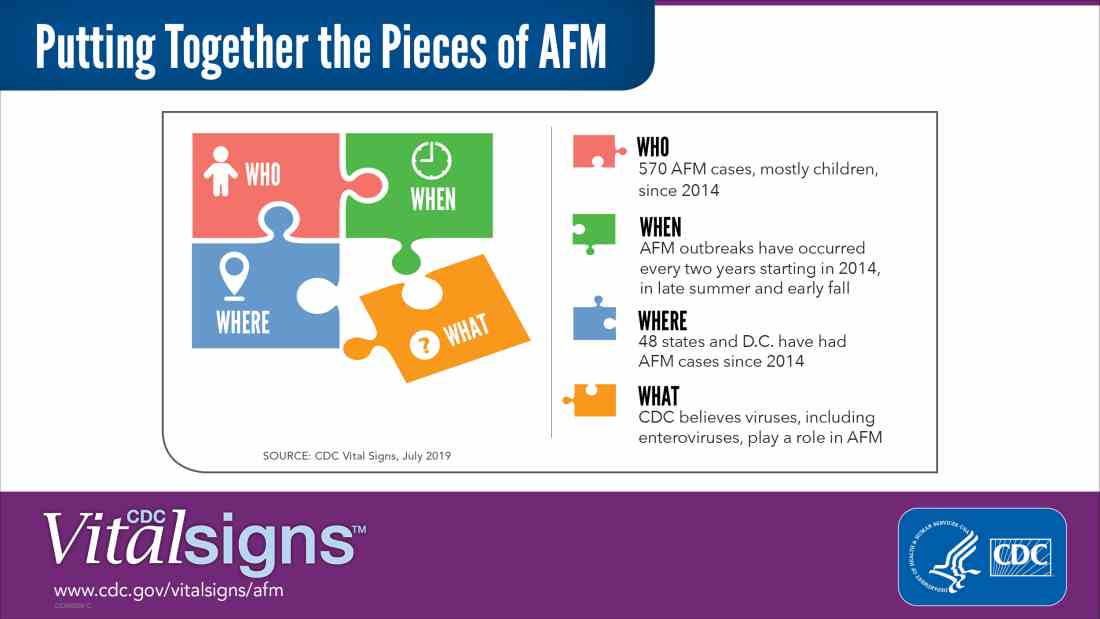

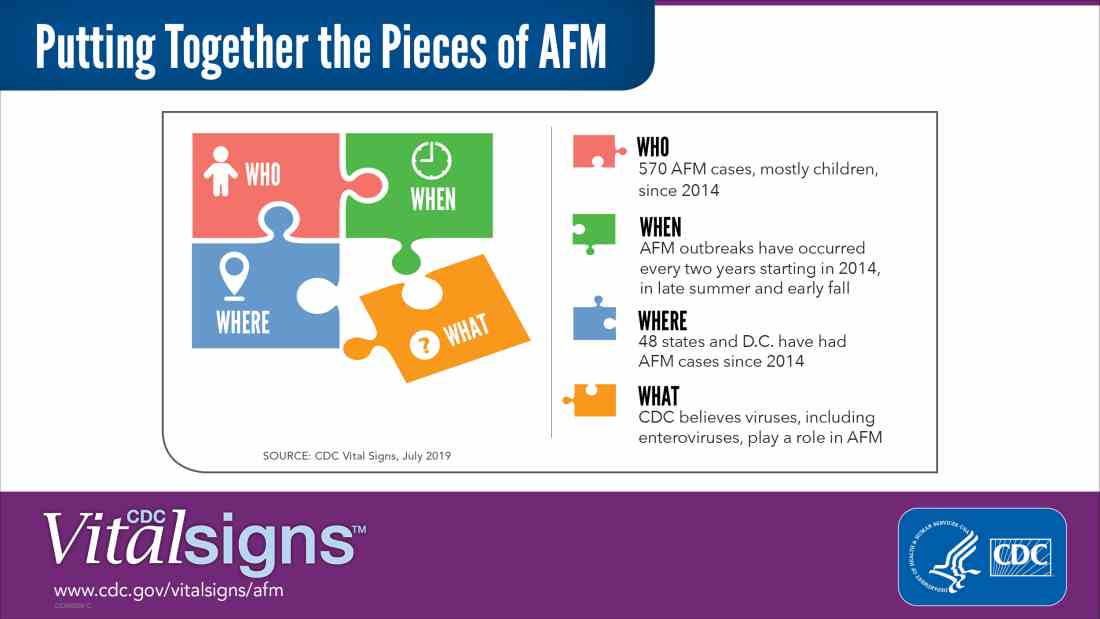

CDC: Look for early symptoms of acute flaccid myelitis, report suspected cases

the CDC said in a telebriefing.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is defined as acute, flaccid muscle weakness that occurs less than 1 week after a fever or respiratory illness. Viruses, including enterovirus, are believed to play a role in AFM, but the cause still is unknown. The disease appears mostly in children, and the average age of a patient diagnosed with AFM is 5 years.

“Doctors and other clinicians in the United States play a critical role,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in the telebriefing. “We ask for your help with early recognition of patients with AFM symptoms, prompt specimen collection for testing, and immediate reporting of suspected AFM cases to health departments.”

While there is no proven treatment for AFM, early diagnosis is critical to getting patients the best care possible, according to a Vital Signs report released today. This means that clinicians should not wait for the CDC’s case definition before diagnosis, the CDC said.

“When specimens are collected as soon as possible after symptom onset, we have a better chance of understanding the causes of AFM, these recurrent outbreaks, and developing a diagnostic test,” Dr. Schuchat said. “Rapid reporting also helps us to identify and respond to outbreaks early and alert other clinicians and the public.”

AFM appears to follow a seasonal and biennial pattern, with the number of cases increasing mainly in the late summer and early fall. As the season approaches where AFM cases increase, CDC is asking clinicians to look out for patients with suspected AFM so cases can be reported as early as possible.

Since the CDC began tracking AFM, the number of cases has risen every 2 years. In 2018, there were 233 cases in 41 states, the highest number of reported cases since the CDC began tracking AFM following an outbreak in 2014, according to a Vital Signs report. Overall, there have been 570 cases of AFM reported in 48 states and the District of Columbia since 2014.

There is yet to be a confirmatory test for AFM, but clinicians should obtain cerebrospinal fluid, serum, stool and nasopharyngeal swab from patients with suspected AFM as soon as possible, followed by an MRI. AFM has unique MRI features , such as gray matter involvement, that can help distinguish it from other diseases characterized by acute weakness.

In the Vital Signs report, which examined AFM in 2018, 92% of confirmed cases had respiratory symptoms or fever, and 42% of confirmed cases had upper limb involvement. The median time from limb weakness to hospitalization was 1 day, and time from weakness to MRI was 2 days. Cases were reported to the CDC a median of 18 days from onset of limb weakness, but time to reporting ranged between 18 days and 36 days, said Tom Clark, MD, MPH, deputy director of the division of viral diseases at CDC.

“This delay hampers our ability to understand the causes AFM,” he said. “We believe that recognizing AFM early is critical and can lead to better patient management.”

In lieu of a diagnostic test for AFM, clinicians should make management decisions through review of patient symptoms, exam findings, MRI, other test results, and in consulting with neurology experts. The Transverse Myelitis Association also has created a support portal for 24/7 physician consultation in AFM cases.

SOURCE: Lopez A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1-7 .

the CDC said in a telebriefing.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is defined as acute, flaccid muscle weakness that occurs less than 1 week after a fever or respiratory illness. Viruses, including enterovirus, are believed to play a role in AFM, but the cause still is unknown. The disease appears mostly in children, and the average age of a patient diagnosed with AFM is 5 years.

“Doctors and other clinicians in the United States play a critical role,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in the telebriefing. “We ask for your help with early recognition of patients with AFM symptoms, prompt specimen collection for testing, and immediate reporting of suspected AFM cases to health departments.”

While there is no proven treatment for AFM, early diagnosis is critical to getting patients the best care possible, according to a Vital Signs report released today. This means that clinicians should not wait for the CDC’s case definition before diagnosis, the CDC said.

“When specimens are collected as soon as possible after symptom onset, we have a better chance of understanding the causes of AFM, these recurrent outbreaks, and developing a diagnostic test,” Dr. Schuchat said. “Rapid reporting also helps us to identify and respond to outbreaks early and alert other clinicians and the public.”

AFM appears to follow a seasonal and biennial pattern, with the number of cases increasing mainly in the late summer and early fall. As the season approaches where AFM cases increase, CDC is asking clinicians to look out for patients with suspected AFM so cases can be reported as early as possible.

Since the CDC began tracking AFM, the number of cases has risen every 2 years. In 2018, there were 233 cases in 41 states, the highest number of reported cases since the CDC began tracking AFM following an outbreak in 2014, according to a Vital Signs report. Overall, there have been 570 cases of AFM reported in 48 states and the District of Columbia since 2014.

There is yet to be a confirmatory test for AFM, but clinicians should obtain cerebrospinal fluid, serum, stool and nasopharyngeal swab from patients with suspected AFM as soon as possible, followed by an MRI. AFM has unique MRI features , such as gray matter involvement, that can help distinguish it from other diseases characterized by acute weakness.

In the Vital Signs report, which examined AFM in 2018, 92% of confirmed cases had respiratory symptoms or fever, and 42% of confirmed cases had upper limb involvement. The median time from limb weakness to hospitalization was 1 day, and time from weakness to MRI was 2 days. Cases were reported to the CDC a median of 18 days from onset of limb weakness, but time to reporting ranged between 18 days and 36 days, said Tom Clark, MD, MPH, deputy director of the division of viral diseases at CDC.

“This delay hampers our ability to understand the causes AFM,” he said. “We believe that recognizing AFM early is critical and can lead to better patient management.”

In lieu of a diagnostic test for AFM, clinicians should make management decisions through review of patient symptoms, exam findings, MRI, other test results, and in consulting with neurology experts. The Transverse Myelitis Association also has created a support portal for 24/7 physician consultation in AFM cases.

SOURCE: Lopez A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1-7 .

the CDC said in a telebriefing.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is defined as acute, flaccid muscle weakness that occurs less than 1 week after a fever or respiratory illness. Viruses, including enterovirus, are believed to play a role in AFM, but the cause still is unknown. The disease appears mostly in children, and the average age of a patient diagnosed with AFM is 5 years.

“Doctors and other clinicians in the United States play a critical role,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in the telebriefing. “We ask for your help with early recognition of patients with AFM symptoms, prompt specimen collection for testing, and immediate reporting of suspected AFM cases to health departments.”

While there is no proven treatment for AFM, early diagnosis is critical to getting patients the best care possible, according to a Vital Signs report released today. This means that clinicians should not wait for the CDC’s case definition before diagnosis, the CDC said.

“When specimens are collected as soon as possible after symptom onset, we have a better chance of understanding the causes of AFM, these recurrent outbreaks, and developing a diagnostic test,” Dr. Schuchat said. “Rapid reporting also helps us to identify and respond to outbreaks early and alert other clinicians and the public.”

AFM appears to follow a seasonal and biennial pattern, with the number of cases increasing mainly in the late summer and early fall. As the season approaches where AFM cases increase, CDC is asking clinicians to look out for patients with suspected AFM so cases can be reported as early as possible.

Since the CDC began tracking AFM, the number of cases has risen every 2 years. In 2018, there were 233 cases in 41 states, the highest number of reported cases since the CDC began tracking AFM following an outbreak in 2014, according to a Vital Signs report. Overall, there have been 570 cases of AFM reported in 48 states and the District of Columbia since 2014.

There is yet to be a confirmatory test for AFM, but clinicians should obtain cerebrospinal fluid, serum, stool and nasopharyngeal swab from patients with suspected AFM as soon as possible, followed by an MRI. AFM has unique MRI features , such as gray matter involvement, that can help distinguish it from other diseases characterized by acute weakness.

In the Vital Signs report, which examined AFM in 2018, 92% of confirmed cases had respiratory symptoms or fever, and 42% of confirmed cases had upper limb involvement. The median time from limb weakness to hospitalization was 1 day, and time from weakness to MRI was 2 days. Cases were reported to the CDC a median of 18 days from onset of limb weakness, but time to reporting ranged between 18 days and 36 days, said Tom Clark, MD, MPH, deputy director of the division of viral diseases at CDC.

“This delay hampers our ability to understand the causes AFM,” he said. “We believe that recognizing AFM early is critical and can lead to better patient management.”

In lieu of a diagnostic test for AFM, clinicians should make management decisions through review of patient symptoms, exam findings, MRI, other test results, and in consulting with neurology experts. The Transverse Myelitis Association also has created a support portal for 24/7 physician consultation in AFM cases.

SOURCE: Lopez A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1-7 .

NEWS FROM THE FDA/CDC

Study: Most patients hospitalized with pneumonia receive excessive antibiotics

Two-thirds of patients hospitalized with pneumonia received an excess duration of antibiotics, according to a recent study of more than 6,000 patients.

.

The findings bolster a growing body of evidence showing that short-course therapy for pneumonia is safe and that longer durations are not only unnecessary, but “potentially harmful,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coinvestigators.

“Reducing excess treatment durations should be a top priority for antibiotic stewardship nationally,” the investigators wrote in their report, which appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The primary analysis of their retrospective cohort study included 6,481 individuals with pneumonia treated at 43 hospitals participating in a statewide quality initiative designed to improve care for hospitalized medical patients at risk of adverse events. About half of the patients were women, and the median age was 70 years. Nearly 60% had severe pneumonia.

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of excess antibiotic therapy duration beyond the shortest expected treatment duration consistent with guidelines. Patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), representing about three-quarters of the study cohort, were expected to have a treatment duration of at least 5 days, while patients with health care–acquired pneumonia (HCAP) were expected to have at least 7 days of treatment.

Overall, 4,391 patients (67.8%) had antibiotic courses longer than the shortest effective duration, with a median duration of 8 days, and a median excess duration of 2 days, the researchers noted.

The great majority of excess days (93.2%) were due to antibiotic prescribed at discharge, according to Dr. Vaughn and colleagues.

Excess treatment duration was not linked to any improvement in 30-day mortality, readmission rates, or subsequent emergency department visits, they found.

In a telephone call at 30 days, 38% of patients treated to excess said they had gone to the doctor for an antibiotic-associated adverse event, compared with 31% who received appropriate-length courses (P = .003).

Odds of a patient-reported adverse event were increased by 5% for every excess treatment day, the investigators wrote.

Taken together, these findings have implications for patient care, research efforts, and future guidelines, according to Dr. Vaughn and coinvestigators.

“The next iteration of CAP and HCAP guidelines should explicitly recommend (rather than imply) that providers prescribe the shortest effective duration,” they said in a discussion of their study results.

Dr. Vaughn reported no disclosures related to the study. Coauthors reported grants from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, personal fees from Wiley Publishing, and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Publishing and Oxford University Press, among other disclosures.

SOURCE: Vaughn VM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:153-63. doi: 10.7326/M18-3640.

This study by Vaughn and colleagues adds “valuable insight” to an already considerable body of evidence showing that shorter durations of antibiotic therapy are effective and limit potential harm due to adverse effects, authors of an accompanying editorial said.

“After dozens of randomized, controlled trials and more than a decade since the initial clarion call to move to short-course therapy, it is time to adapt clinical practice for diseases that have been studied and adopt the mantra ‘shorter is better,’ ” Brad Spellberg, MD, and Louis B. Rice, MD, wrote in their editorial.

“It is time for regulatory agencies, payers, and professional societies to align themselves with the overwhelming data and assist in converting practice patterns to short-course therapy,” the authors said.

Brad Spellberg, MD, is with the Los Angeles County–University of Southern California Medical Center, and Louis B. Rice, MD, is with Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University, Providence, R.I. Their editorial appears in Annals of Internal Medicine. The authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work from Alexion, Paratek, TheoremDx, Acurx, Shionogi, Merck, Motif, BioAIM, Mycomed, and ExBaq (Dr. Spellberg); and Zavante Pharmaceuticals and Macrolide (Dr. Rice).

This study by Vaughn and colleagues adds “valuable insight” to an already considerable body of evidence showing that shorter durations of antibiotic therapy are effective and limit potential harm due to adverse effects, authors of an accompanying editorial said.

“After dozens of randomized, controlled trials and more than a decade since the initial clarion call to move to short-course therapy, it is time to adapt clinical practice for diseases that have been studied and adopt the mantra ‘shorter is better,’ ” Brad Spellberg, MD, and Louis B. Rice, MD, wrote in their editorial.

“It is time for regulatory agencies, payers, and professional societies to align themselves with the overwhelming data and assist in converting practice patterns to short-course therapy,” the authors said.

Brad Spellberg, MD, is with the Los Angeles County–University of Southern California Medical Center, and Louis B. Rice, MD, is with Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University, Providence, R.I. Their editorial appears in Annals of Internal Medicine. The authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work from Alexion, Paratek, TheoremDx, Acurx, Shionogi, Merck, Motif, BioAIM, Mycomed, and ExBaq (Dr. Spellberg); and Zavante Pharmaceuticals and Macrolide (Dr. Rice).

This study by Vaughn and colleagues adds “valuable insight” to an already considerable body of evidence showing that shorter durations of antibiotic therapy are effective and limit potential harm due to adverse effects, authors of an accompanying editorial said.

“After dozens of randomized, controlled trials and more than a decade since the initial clarion call to move to short-course therapy, it is time to adapt clinical practice for diseases that have been studied and adopt the mantra ‘shorter is better,’ ” Brad Spellberg, MD, and Louis B. Rice, MD, wrote in their editorial.

“It is time for regulatory agencies, payers, and professional societies to align themselves with the overwhelming data and assist in converting practice patterns to short-course therapy,” the authors said.

Brad Spellberg, MD, is with the Los Angeles County–University of Southern California Medical Center, and Louis B. Rice, MD, is with Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University, Providence, R.I. Their editorial appears in Annals of Internal Medicine. The authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work from Alexion, Paratek, TheoremDx, Acurx, Shionogi, Merck, Motif, BioAIM, Mycomed, and ExBaq (Dr. Spellberg); and Zavante Pharmaceuticals and Macrolide (Dr. Rice).

Two-thirds of patients hospitalized with pneumonia received an excess duration of antibiotics, according to a recent study of more than 6,000 patients.

.

The findings bolster a growing body of evidence showing that short-course therapy for pneumonia is safe and that longer durations are not only unnecessary, but “potentially harmful,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coinvestigators.

“Reducing excess treatment durations should be a top priority for antibiotic stewardship nationally,” the investigators wrote in their report, which appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The primary analysis of their retrospective cohort study included 6,481 individuals with pneumonia treated at 43 hospitals participating in a statewide quality initiative designed to improve care for hospitalized medical patients at risk of adverse events. About half of the patients were women, and the median age was 70 years. Nearly 60% had severe pneumonia.

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of excess antibiotic therapy duration beyond the shortest expected treatment duration consistent with guidelines. Patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), representing about three-quarters of the study cohort, were expected to have a treatment duration of at least 5 days, while patients with health care–acquired pneumonia (HCAP) were expected to have at least 7 days of treatment.

Overall, 4,391 patients (67.8%) had antibiotic courses longer than the shortest effective duration, with a median duration of 8 days, and a median excess duration of 2 days, the researchers noted.

The great majority of excess days (93.2%) were due to antibiotic prescribed at discharge, according to Dr. Vaughn and colleagues.

Excess treatment duration was not linked to any improvement in 30-day mortality, readmission rates, or subsequent emergency department visits, they found.

In a telephone call at 30 days, 38% of patients treated to excess said they had gone to the doctor for an antibiotic-associated adverse event, compared with 31% who received appropriate-length courses (P = .003).

Odds of a patient-reported adverse event were increased by 5% for every excess treatment day, the investigators wrote.

Taken together, these findings have implications for patient care, research efforts, and future guidelines, according to Dr. Vaughn and coinvestigators.

“The next iteration of CAP and HCAP guidelines should explicitly recommend (rather than imply) that providers prescribe the shortest effective duration,” they said in a discussion of their study results.

Dr. Vaughn reported no disclosures related to the study. Coauthors reported grants from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, personal fees from Wiley Publishing, and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Publishing and Oxford University Press, among other disclosures.

SOURCE: Vaughn VM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:153-63. doi: 10.7326/M18-3640.

Two-thirds of patients hospitalized with pneumonia received an excess duration of antibiotics, according to a recent study of more than 6,000 patients.

.

The findings bolster a growing body of evidence showing that short-course therapy for pneumonia is safe and that longer durations are not only unnecessary, but “potentially harmful,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coinvestigators.

“Reducing excess treatment durations should be a top priority for antibiotic stewardship nationally,” the investigators wrote in their report, which appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The primary analysis of their retrospective cohort study included 6,481 individuals with pneumonia treated at 43 hospitals participating in a statewide quality initiative designed to improve care for hospitalized medical patients at risk of adverse events. About half of the patients were women, and the median age was 70 years. Nearly 60% had severe pneumonia.

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of excess antibiotic therapy duration beyond the shortest expected treatment duration consistent with guidelines. Patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), representing about three-quarters of the study cohort, were expected to have a treatment duration of at least 5 days, while patients with health care–acquired pneumonia (HCAP) were expected to have at least 7 days of treatment.

Overall, 4,391 patients (67.8%) had antibiotic courses longer than the shortest effective duration, with a median duration of 8 days, and a median excess duration of 2 days, the researchers noted.

The great majority of excess days (93.2%) were due to antibiotic prescribed at discharge, according to Dr. Vaughn and colleagues.

Excess treatment duration was not linked to any improvement in 30-day mortality, readmission rates, or subsequent emergency department visits, they found.

In a telephone call at 30 days, 38% of patients treated to excess said they had gone to the doctor for an antibiotic-associated adverse event, compared with 31% who received appropriate-length courses (P = .003).

Odds of a patient-reported adverse event were increased by 5% for every excess treatment day, the investigators wrote.

Taken together, these findings have implications for patient care, research efforts, and future guidelines, according to Dr. Vaughn and coinvestigators.

“The next iteration of CAP and HCAP guidelines should explicitly recommend (rather than imply) that providers prescribe the shortest effective duration,” they said in a discussion of their study results.

Dr. Vaughn reported no disclosures related to the study. Coauthors reported grants from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, personal fees from Wiley Publishing, and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Publishing and Oxford University Press, among other disclosures.

SOURCE: Vaughn VM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:153-63. doi: 10.7326/M18-3640.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Excessive antibiotic therapy was common among patients hospitalized with pneumonia and linked to an increase in patient-reported adverse events.

Major finding: Two-thirds (67.8%) of patients had antibiotic courses longer than the shortest effective duration.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 6,481 individuals with pneumonia treated at 43 hospitals participating in a statewide quality initiative.

Disclosures: Study authors reported grants from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, personal fees from Wiley Publishing, and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Publishing and Oxford University Press, among other disclosures.

Source: Vaughn VM et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:153-63. doi: 10.7326/M18-3640.

Uncomplicated appendicitis can be treated successfully with antibiotics

Clinical question: What is the late recurrence rate for patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics only?

Background: Short-term results support antibiotic treatment as alternative to surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. Long-term outcomes have not been assessed.

Study design: Observational follow-up.

Setting: Six hospitals in Finland.

Synopsis: The APPAC trial looked at 530 patients, aged 18-60 years, with CT confirmed acute uncomplicated appendicitis, who were randomized to receive either appendectomy or antibiotics. In this follow-up report, outcomes were assessed by telephone interviews conducted 3-5 years after the initial interventions. Overall, 100 of 256 (39.1%) of the antibiotic group ultimately underwent appendectomy within 5 years. Of those, 70/100 (70%) had their recurrence within 1 year of their initial presentation.

Bottom line: Patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics have a 39% cumulative 5-year recurrence rate, with most recurrences occurring within the first year.

Citation: Salminem P et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259-65.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: What is the late recurrence rate for patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics only?

Background: Short-term results support antibiotic treatment as alternative to surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. Long-term outcomes have not been assessed.

Study design: Observational follow-up.

Setting: Six hospitals in Finland.

Synopsis: The APPAC trial looked at 530 patients, aged 18-60 years, with CT confirmed acute uncomplicated appendicitis, who were randomized to receive either appendectomy or antibiotics. In this follow-up report, outcomes were assessed by telephone interviews conducted 3-5 years after the initial interventions. Overall, 100 of 256 (39.1%) of the antibiotic group ultimately underwent appendectomy within 5 years. Of those, 70/100 (70%) had their recurrence within 1 year of their initial presentation.

Bottom line: Patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics have a 39% cumulative 5-year recurrence rate, with most recurrences occurring within the first year.

Citation: Salminem P et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259-65.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: What is the late recurrence rate for patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics only?

Background: Short-term results support antibiotic treatment as alternative to surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. Long-term outcomes have not been assessed.

Study design: Observational follow-up.

Setting: Six hospitals in Finland.

Synopsis: The APPAC trial looked at 530 patients, aged 18-60 years, with CT confirmed acute uncomplicated appendicitis, who were randomized to receive either appendectomy or antibiotics. In this follow-up report, outcomes were assessed by telephone interviews conducted 3-5 years after the initial interventions. Overall, 100 of 256 (39.1%) of the antibiotic group ultimately underwent appendectomy within 5 years. Of those, 70/100 (70%) had their recurrence within 1 year of their initial presentation.

Bottom line: Patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics have a 39% cumulative 5-year recurrence rate, with most recurrences occurring within the first year.

Citation: Salminem P et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259-65.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Almost one-third of ED patients with gout are prescribed opioids

Patients with gout who visit the emergency department are regularly prescribed opioids, based on a review of electronic medical records.

“In addition to regulatory changes, the burden of opioid prescription could be potentially reduced by creating prompts for providers in electronic record systems to avoid prescribing opioids in opioid-naive patients or using lower intensity and shorter duration of prescription,” wrote Deepan S. Dalal, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and coauthors. The study was published in Arthritis Care & Research.

To determine frequency, dose, and duration of opioid prescription at ED discharge, the researchers reviewed the records of 456 patients with acute gout who were discharged in Rhode Island between March 30, 2015, and Sept. 30, 2017. All data were gathered via electronic medical system records.

Of the 456 discharged patients, 129 (28.3%) were prescribed opioids; 102 (79%) were not on opioids at the time. A full prescription description was available for 119 of the 129 patients; 96 (81%) were prescribed oxycodone or oxycodone combinations. Hydrocodone was prescribed for 9 patients (8%) and tramadol was prescribed for 11 patients (9%).

The median duration of each prescription was 8 days (interquartile range, 5-14 days) and the average daily dose was 37.9 mg of morphine equivalent. Patients who were prescribed opioids tended to be younger and male. After multivariable analysis, diabetes, polyarticular gout attack, and prior opioid use were all associated with a more than 100% higher odds of receiving an opioid prescription.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including their inability to determine the physicians’ reasoning behind each prescription or the prescribing habits of each provider. In addition, they were only able to assess the prescriptions as being written and not the number of pills actually taken or not taken.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Dalal DS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23928.

Patients with gout who visit the emergency department are regularly prescribed opioids, based on a review of electronic medical records.

“In addition to regulatory changes, the burden of opioid prescription could be potentially reduced by creating prompts for providers in electronic record systems to avoid prescribing opioids in opioid-naive patients or using lower intensity and shorter duration of prescription,” wrote Deepan S. Dalal, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and coauthors. The study was published in Arthritis Care & Research.

To determine frequency, dose, and duration of opioid prescription at ED discharge, the researchers reviewed the records of 456 patients with acute gout who were discharged in Rhode Island between March 30, 2015, and Sept. 30, 2017. All data were gathered via electronic medical system records.

Of the 456 discharged patients, 129 (28.3%) were prescribed opioids; 102 (79%) were not on opioids at the time. A full prescription description was available for 119 of the 129 patients; 96 (81%) were prescribed oxycodone or oxycodone combinations. Hydrocodone was prescribed for 9 patients (8%) and tramadol was prescribed for 11 patients (9%).

The median duration of each prescription was 8 days (interquartile range, 5-14 days) and the average daily dose was 37.9 mg of morphine equivalent. Patients who were prescribed opioids tended to be younger and male. After multivariable analysis, diabetes, polyarticular gout attack, and prior opioid use were all associated with a more than 100% higher odds of receiving an opioid prescription.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including their inability to determine the physicians’ reasoning behind each prescription or the prescribing habits of each provider. In addition, they were only able to assess the prescriptions as being written and not the number of pills actually taken or not taken.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Dalal DS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23928.

Patients with gout who visit the emergency department are regularly prescribed opioids, based on a review of electronic medical records.

“In addition to regulatory changes, the burden of opioid prescription could be potentially reduced by creating prompts for providers in electronic record systems to avoid prescribing opioids in opioid-naive patients or using lower intensity and shorter duration of prescription,” wrote Deepan S. Dalal, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and coauthors. The study was published in Arthritis Care & Research.

To determine frequency, dose, and duration of opioid prescription at ED discharge, the researchers reviewed the records of 456 patients with acute gout who were discharged in Rhode Island between March 30, 2015, and Sept. 30, 2017. All data were gathered via electronic medical system records.

Of the 456 discharged patients, 129 (28.3%) were prescribed opioids; 102 (79%) were not on opioids at the time. A full prescription description was available for 119 of the 129 patients; 96 (81%) were prescribed oxycodone or oxycodone combinations. Hydrocodone was prescribed for 9 patients (8%) and tramadol was prescribed for 11 patients (9%).

The median duration of each prescription was 8 days (interquartile range, 5-14 days) and the average daily dose was 37.9 mg of morphine equivalent. Patients who were prescribed opioids tended to be younger and male. After multivariable analysis, diabetes, polyarticular gout attack, and prior opioid use were all associated with a more than 100% higher odds of receiving an opioid prescription.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including their inability to determine the physicians’ reasoning behind each prescription or the prescribing habits of each provider. In addition, they were only able to assess the prescriptions as being written and not the number of pills actually taken or not taken.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Dalal DS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23928.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Though there are other effective conventional treatments, opioids are often prescribed for patients who present to the ED with gout.

Major finding: After multivariable analysis, diabetes, polyarticular gout attack, and prior opioid use were all associated with a more than 100% higher odds of opioid prescription.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 456 patients with acute gout discharged from EDs in Rhode Island.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Dalal DS et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23928.

The hospitalist role in treating opioid use disorder

Screen patients at the time of admission

Let’s begin with a brief case. A 25-year-old patient with a history of injection heroin use is in your care. He is admitted for treatment of endocarditis and will remain in the hospital for intravenous antibiotics for several weeks. Over the first few days of hospitalization, he frequently asks for pain medicine, stating that he is in severe pain, withdrawal, and having opioid cravings. On day 3, he leaves the hospital against medical advice. After 2 weeks, he presents to the ED in septic shock and spends several weeks in the ICU. Or, alternatively, he is found down in the community and pronounced dead from a heroin overdose.

These cases occur all too often, and hospitalists across the nation are actively building knowledge and programs to improve care for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). It is evident that opioid misuse is the public health crisis of our time. In 2017, over 70,000 patients died from an overdose, and over 2 million patients in the United States have a diagnosis of OUD.1,2 Many of these patients interact with the hospital at some point during the course of their illness for management of overdose, withdrawal, and other complications of OUD, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and skin and soft tissue infections. Moreover, just 20% of the 580,000 patients hospitalized with OUD in 2015 presented as a direct sequelae of the disease.3 Patients with OUD are often admitted for unrelated reasons, but their addiction goes unaddressed.

Opioid use disorder, like many of the other conditions we see, is a chronic relapsing remitting medical disease and a risk factor for premature mortality. When a patient with diabetes is admitted with cellulitis, we might check an A1C, provide diabetic counseling, and offer evidence-based diabetes treatment, including medications like insulin. We rarely build similar systems of care within the walls of our hospitals to treat OUD like we do for diabetes or other commonly encountered diseases like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

We should be intentional about separating prevention from treatment. Significant work has gone into reducing the availability of prescription opioids and increasing utilization of prescription drug monitoring programs. As a result, the average morphine milligram equivalent per opioid prescription has decreased since 2010.4 An unintended consequence of restricting legal opioids is potentially pushing patients with opioid addiction towards heroin and fentanyl. Limiting opioid prescriptions alone will only decrease opioid overdose mortality by 5% through 2025.5 Thus, treatment of OUD is critical and something that hospitalists should be trained and engaged in.

Food and Drug Administration–approved OUD treatment includes buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone. Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that treats withdrawal and cravings. Buprenorphine started in the hospital reduces mortality, increases time spent in outpatient treatment after discharge, and reduces opioid-related 30-day readmissions by over 50%.6-8 The number needed to treat with buprenorphine to prevent return to illicit opioid use is two.9 While physicians require an 8-hour “x-waiver” training (physician assistants and nurse practitioners require a 24-hour training) to prescribe buprenorphine for the outpatient treatment of OUD, such certification is not required to order the medication as part of an acute hospitalization.

Hospitalization represents a reachable moment and unique opportunity to start treatment for OUD. Patients are away from triggering environments and surrounded by supportive staff. Unfortunately, up to 30% of these patients leave the hospital against medical advice because of inadequately treated withdrawal, unaddressed cravings, and fear of mistreatment.10 Buprenorphine therapy may help tackle the physiological piece of hospital-based treatment, but we also must work on shifting the culture of our institutions. Importantly, OUD is a medical diagnosis. These patients must receive the same dignity, autonomy, and meaningful care afforded to patients with other medical diagnoses. Patients with OUD are not “addicts,” “abusers,” or “frequent fliers.”

Hospitalists have a clear and compelling role in treating OUD. The National Academy of Medicine recently held a workshop where they compared similarities of the HIV crisis with today’s opioid epidemic. The Academy advocated for the development of hospital-based protocols that empower physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners to integrate the treatment of OUD into their practice.11 Some in our field may feel that treating underlying addiction is a role for behavioral health practitioners. This is akin to having said that HIV specialists should be the only providers to treat patients with HIV during its peak. There are simply not enough psychiatrists or addiction medicine specialists to treat all of the patients who need us during this time of national urgency.

There are several examples of institutions that are laying the groundwork for this important work. The University of California, San Francisco; Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; Rush Medical College, Boston; Boston Medical Center; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; and the University of Texas at Austin – to name a few. Offering OUD treatment in the hospital setting must be our new and only acceptable standard of care.