User login

FDA approves diroximel fumarate for relapsing MS

The Food and Drug Administration has approved diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, according to an Oct. 30 announcement from its developers, Biogen and Alkermes.

The approval is based on pharmacokinetic studies that established the bioequivalence of diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and it relied in part on the safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate, which was approved in 2013. Diroximel fumarate rapidly converts to monomethyl fumarate, the same active metabolite as dimethyl fumarate.

Diroximel fumarate may be better tolerated than dimethyl fumarate. A trial found that the newer drug has significantly better gastrointestinal tolerability, the developers of the drug announced in July. In addition, the drug application for diroximel fumarate included interim data from EVOLVE-MS-1, an ongoing, open-label, 2-year safety study evaluating diroximel fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Researchers found a 6.3% rate of treatment discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal adverse events.

Serious side effects of diroximel fumarate may include allergic reaction, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, decreases in white blood cell count, and liver problems. Flushing and stomach problems are the most common side effects, which may decrease over time.

Biogen plans to make diroximel fumarate available in the United States in the near future, the company said. Prescribing information is available online.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, according to an Oct. 30 announcement from its developers, Biogen and Alkermes.

The approval is based on pharmacokinetic studies that established the bioequivalence of diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and it relied in part on the safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate, which was approved in 2013. Diroximel fumarate rapidly converts to monomethyl fumarate, the same active metabolite as dimethyl fumarate.

Diroximel fumarate may be better tolerated than dimethyl fumarate. A trial found that the newer drug has significantly better gastrointestinal tolerability, the developers of the drug announced in July. In addition, the drug application for diroximel fumarate included interim data from EVOLVE-MS-1, an ongoing, open-label, 2-year safety study evaluating diroximel fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Researchers found a 6.3% rate of treatment discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal adverse events.

Serious side effects of diroximel fumarate may include allergic reaction, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, decreases in white blood cell count, and liver problems. Flushing and stomach problems are the most common side effects, which may decrease over time.

Biogen plans to make diroximel fumarate available in the United States in the near future, the company said. Prescribing information is available online.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults, including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, according to an Oct. 30 announcement from its developers, Biogen and Alkermes.

The approval is based on pharmacokinetic studies that established the bioequivalence of diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), and it relied in part on the safety and efficacy data for dimethyl fumarate, which was approved in 2013. Diroximel fumarate rapidly converts to monomethyl fumarate, the same active metabolite as dimethyl fumarate.

Diroximel fumarate may be better tolerated than dimethyl fumarate. A trial found that the newer drug has significantly better gastrointestinal tolerability, the developers of the drug announced in July. In addition, the drug application for diroximel fumarate included interim data from EVOLVE-MS-1, an ongoing, open-label, 2-year safety study evaluating diroximel fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Researchers found a 6.3% rate of treatment discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal adverse events.

Serious side effects of diroximel fumarate may include allergic reaction, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, decreases in white blood cell count, and liver problems. Flushing and stomach problems are the most common side effects, which may decrease over time.

Biogen plans to make diroximel fumarate available in the United States in the near future, the company said. Prescribing information is available online.

Role of Psoriasis in the Development of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

1. O’Brien T, Power DG. Metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma: the dawn of a new era. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11:2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224924.

2. Del Marmol V, Lebbé C. New perspectives in Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:72-83.

3. Garcia-Carbonero R, Marquez-Rodas I, de la Cruz-Merino L, et al. Recent therapeutic advances and change in treatment paradigm of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma [published online April 8, 2019]. Oncologist. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0718.

4. Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

5. Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

6. Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

7. Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

8. Yousif J, Yousif B, Kuriata MA. Complete remission of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;101:E24-E27.

9. Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

10. Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

11. Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Merkel cell carcinoma. Published October 3, 2016. http://merkelcell.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/MccNccn.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

13. Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

14. Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

15. Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

1. O’Brien T, Power DG. Metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma: the dawn of a new era. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11:2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224924.

2. Del Marmol V, Lebbé C. New perspectives in Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:72-83.

3. Garcia-Carbonero R, Marquez-Rodas I, de la Cruz-Merino L, et al. Recent therapeutic advances and change in treatment paradigm of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma [published online April 8, 2019]. Oncologist. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0718.

4. Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

5. Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

6. Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

7. Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

8. Yousif J, Yousif B, Kuriata MA. Complete remission of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;101:E24-E27.

9. Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

10. Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

11. Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Merkel cell carcinoma. Published October 3, 2016. http://merkelcell.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/MccNccn.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

13. Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

14. Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

15. Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

1. O’Brien T, Power DG. Metastatic Merkel-cell carcinoma: the dawn of a new era. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11:2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224924.

2. Del Marmol V, Lebbé C. New perspectives in Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31:72-83.

3. Garcia-Carbonero R, Marquez-Rodas I, de la Cruz-Merino L, et al. Recent therapeutic advances and change in treatment paradigm of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma [published online April 8, 2019]. Oncologist. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0718.

4. Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

5. Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

6. Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

7. Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

8. Yousif J, Yousif B, Kuriata MA. Complete remission of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with severe psoriasis. Cutis. 2018;101:E24-E27.

9. Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

10. Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

11. Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Merkel cell carcinoma. Published October 3, 2016. http://merkelcell.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/MccNccn.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

13. Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

14. Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

15. Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

Role of the Nervous System in Psoriasis

1. Amanat M, Salehi M, Rezaei N. Neurological and psychiatric disorders in psoriasis. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29:805-813.

2. Eberle FC, Brück J, Holstein J, et al. Recent advances in understanding psoriasis [published April 28, 2016]. F1000Res. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7927.1.

3. Lee EB, Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, et al. Clearance of psoriasis after ischemic stroke. Cutis. 2019;103:74-76.

4. Zhu TH, Nakamura M, Farahnik B, et al. The role of the nervous system in the pathophysiology of psoriasis: a review of cases of psoriasis remission or improvement following denervation injury. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:257-263.

5. Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. Neuroimmunologic aspects of psoriasis. Cutis. 2000;66:357-362.

6. Kwon CW, Fried RG, Nousari Y, et al. Psoriasis: psychosomatic, somatopsychic, or both? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:698-703.

7. Lotti T, D’Erme AM, Hercogová J. The role of neuropeptides in the control of regional immunity. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:633-645.

8. Hall JM, Cruser D, Podawiltz A, et al. Psychological stress and the cutaneous immune response: roles of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [published online August 30, 2012]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:403908.

9. Raychaudhuri SK, Raychaudhuri SP. NGF and its receptor system: a new dimension in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:470-477.

10. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:243-251.

11. Levi-Montalcini R, Skaper SD, Dal Toso R, et al. Nerve growth factor: from neurotrophin to neurokine. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:514-520.

12. Harvima IT, Viinamäki H, Naukkarinen A, et al. Association of cutaneous mast cells and sensory nerves with psychic stress in psoriasis. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;60:168-176.

13. He Y, Ding G, Wang X, et al. Calcitonin gene‐related peptide in Langerhans cells in psoriatic plaque lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2000;113:747-751.

14. Chu DQ, Choy M, Foster P, et al. A comparative study of the ability of calcitonin gene‐related peptide and adrenomedullin13–52 to modulate microvascular but not thermal hyperalgesia responses. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1589-1596.

15. Al’Abadie MS, Senior HJ, Bleehen SS, et al. Neuropeptides and general neuronal marker in psoriasis—an immunohistochemical study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:384-389.

16. Farber EM, Nickoloff BJ, Recht B, et al. Stress, symmetry, and psoriasis: possible role of neuropeptides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2, pt 1):305-311.

17. Pincelli C, Fantini F, Romualdi P, et al. Substance P is diminished and vasoactive intestinal peptide is augmented in psoriatic lesions and these peptides exert disparate effects on the proliferation of cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:421-427.

18. Raychaudhuri SP, Jiang WY, Farber EM. Psoriatic keratinocytes express high levels of nerve growth factor. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:84-86.

19. Pincelli C. Nerve growth factor and keratinocytes: a role in psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:85-90.

20. Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

21. Nakamura M, Toyoda M, Morohashi M. Pruritogenic mediators in psoriasis vulgaris: comparative evaluation of itch-associated cutaneous factors. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:718-730.

22. Stratigos AJ, Katoulis AK, Stavrianeas NG. Spontaneous clearing of psoriasis after stroke. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5, pt 1):768-770.

23. Wang TS, Tsai TF. Psoriasis sparing the lower limb with postpoliomyelitis residual paralysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:429-431.

24. Weiner SR, Bassett LW, Reichman RP. Protective effect of poliomyelitis on psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:703-706.

25. Ostrowski SM, Belkai A, Loyd CM, et al. Cutaneous denervation of psoriasiform mouse skin improves acanthosis and inflammation in a sensory neuropeptide-dependent manner. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1530-1538.

26. Farber EM, Lanigan SW, Boer J. The role of cutaneous sensory nerves in the maintenance of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:418-420.

27. Dewing SB. Remission of psoriasis associated with cutaneous nerve section. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:220-221.

28. Perlman HH. Remission of psoriasis vulgaris from the use of nerve-blocking agents. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:128-129.

1. Amanat M, Salehi M, Rezaei N. Neurological and psychiatric disorders in psoriasis. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29:805-813.

2. Eberle FC, Brück J, Holstein J, et al. Recent advances in understanding psoriasis [published April 28, 2016]. F1000Res. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7927.1.

3. Lee EB, Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, et al. Clearance of psoriasis after ischemic stroke. Cutis. 2019;103:74-76.

4. Zhu TH, Nakamura M, Farahnik B, et al. The role of the nervous system in the pathophysiology of psoriasis: a review of cases of psoriasis remission or improvement following denervation injury. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:257-263.

5. Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. Neuroimmunologic aspects of psoriasis. Cutis. 2000;66:357-362.

6. Kwon CW, Fried RG, Nousari Y, et al. Psoriasis: psychosomatic, somatopsychic, or both? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:698-703.

7. Lotti T, D’Erme AM, Hercogová J. The role of neuropeptides in the control of regional immunity. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:633-645.

8. Hall JM, Cruser D, Podawiltz A, et al. Psychological stress and the cutaneous immune response: roles of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [published online August 30, 2012]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:403908.

9. Raychaudhuri SK, Raychaudhuri SP. NGF and its receptor system: a new dimension in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:470-477.

10. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:243-251.

11. Levi-Montalcini R, Skaper SD, Dal Toso R, et al. Nerve growth factor: from neurotrophin to neurokine. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:514-520.

12. Harvima IT, Viinamäki H, Naukkarinen A, et al. Association of cutaneous mast cells and sensory nerves with psychic stress in psoriasis. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;60:168-176.

13. He Y, Ding G, Wang X, et al. Calcitonin gene‐related peptide in Langerhans cells in psoriatic plaque lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2000;113:747-751.

14. Chu DQ, Choy M, Foster P, et al. A comparative study of the ability of calcitonin gene‐related peptide and adrenomedullin13–52 to modulate microvascular but not thermal hyperalgesia responses. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1589-1596.

15. Al’Abadie MS, Senior HJ, Bleehen SS, et al. Neuropeptides and general neuronal marker in psoriasis—an immunohistochemical study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:384-389.

16. Farber EM, Nickoloff BJ, Recht B, et al. Stress, symmetry, and psoriasis: possible role of neuropeptides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2, pt 1):305-311.

17. Pincelli C, Fantini F, Romualdi P, et al. Substance P is diminished and vasoactive intestinal peptide is augmented in psoriatic lesions and these peptides exert disparate effects on the proliferation of cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:421-427.

18. Raychaudhuri SP, Jiang WY, Farber EM. Psoriatic keratinocytes express high levels of nerve growth factor. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:84-86.

19. Pincelli C. Nerve growth factor and keratinocytes: a role in psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:85-90.

20. Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

21. Nakamura M, Toyoda M, Morohashi M. Pruritogenic mediators in psoriasis vulgaris: comparative evaluation of itch-associated cutaneous factors. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:718-730.

22. Stratigos AJ, Katoulis AK, Stavrianeas NG. Spontaneous clearing of psoriasis after stroke. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5, pt 1):768-770.

23. Wang TS, Tsai TF. Psoriasis sparing the lower limb with postpoliomyelitis residual paralysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:429-431.

24. Weiner SR, Bassett LW, Reichman RP. Protective effect of poliomyelitis on psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:703-706.

25. Ostrowski SM, Belkai A, Loyd CM, et al. Cutaneous denervation of psoriasiform mouse skin improves acanthosis and inflammation in a sensory neuropeptide-dependent manner. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1530-1538.

26. Farber EM, Lanigan SW, Boer J. The role of cutaneous sensory nerves in the maintenance of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:418-420.

27. Dewing SB. Remission of psoriasis associated with cutaneous nerve section. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:220-221.

28. Perlman HH. Remission of psoriasis vulgaris from the use of nerve-blocking agents. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:128-129.

1. Amanat M, Salehi M, Rezaei N. Neurological and psychiatric disorders in psoriasis. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29:805-813.

2. Eberle FC, Brück J, Holstein J, et al. Recent advances in understanding psoriasis [published April 28, 2016]. F1000Res. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7927.1.

3. Lee EB, Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, et al. Clearance of psoriasis after ischemic stroke. Cutis. 2019;103:74-76.

4. Zhu TH, Nakamura M, Farahnik B, et al. The role of the nervous system in the pathophysiology of psoriasis: a review of cases of psoriasis remission or improvement following denervation injury. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:257-263.

5. Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. Neuroimmunologic aspects of psoriasis. Cutis. 2000;66:357-362.

6. Kwon CW, Fried RG, Nousari Y, et al. Psoriasis: psychosomatic, somatopsychic, or both? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:698-703.

7. Lotti T, D’Erme AM, Hercogová J. The role of neuropeptides in the control of regional immunity. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:633-645.

8. Hall JM, Cruser D, Podawiltz A, et al. Psychological stress and the cutaneous immune response: roles of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [published online August 30, 2012]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:403908.

9. Raychaudhuri SK, Raychaudhuri SP. NGF and its receptor system: a new dimension in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:470-477.

10. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:243-251.

11. Levi-Montalcini R, Skaper SD, Dal Toso R, et al. Nerve growth factor: from neurotrophin to neurokine. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:514-520.

12. Harvima IT, Viinamäki H, Naukkarinen A, et al. Association of cutaneous mast cells and sensory nerves with psychic stress in psoriasis. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;60:168-176.

13. He Y, Ding G, Wang X, et al. Calcitonin gene‐related peptide in Langerhans cells in psoriatic plaque lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2000;113:747-751.

14. Chu DQ, Choy M, Foster P, et al. A comparative study of the ability of calcitonin gene‐related peptide and adrenomedullin13–52 to modulate microvascular but not thermal hyperalgesia responses. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1589-1596.

15. Al’Abadie MS, Senior HJ, Bleehen SS, et al. Neuropeptides and general neuronal marker in psoriasis—an immunohistochemical study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:384-389.

16. Farber EM, Nickoloff BJ, Recht B, et al. Stress, symmetry, and psoriasis: possible role of neuropeptides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2, pt 1):305-311.

17. Pincelli C, Fantini F, Romualdi P, et al. Substance P is diminished and vasoactive intestinal peptide is augmented in psoriatic lesions and these peptides exert disparate effects on the proliferation of cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:421-427.

18. Raychaudhuri SP, Jiang WY, Farber EM. Psoriatic keratinocytes express high levels of nerve growth factor. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:84-86.

19. Pincelli C. Nerve growth factor and keratinocytes: a role in psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:85-90.

20. Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:231-236.

21. Nakamura M, Toyoda M, Morohashi M. Pruritogenic mediators in psoriasis vulgaris: comparative evaluation of itch-associated cutaneous factors. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:718-730.

22. Stratigos AJ, Katoulis AK, Stavrianeas NG. Spontaneous clearing of psoriasis after stroke. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5, pt 1):768-770.

23. Wang TS, Tsai TF. Psoriasis sparing the lower limb with postpoliomyelitis residual paralysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:429-431.

24. Weiner SR, Bassett LW, Reichman RP. Protective effect of poliomyelitis on psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:703-706.

25. Ostrowski SM, Belkai A, Loyd CM, et al. Cutaneous denervation of psoriasiform mouse skin improves acanthosis and inflammation in a sensory neuropeptide-dependent manner. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1530-1538.

26. Farber EM, Lanigan SW, Boer J. The role of cutaneous sensory nerves in the maintenance of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:418-420.

27. Dewing SB. Remission of psoriasis associated with cutaneous nerve section. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:220-221.

28. Perlman HH. Remission of psoriasis vulgaris from the use of nerve-blocking agents. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:128-129.

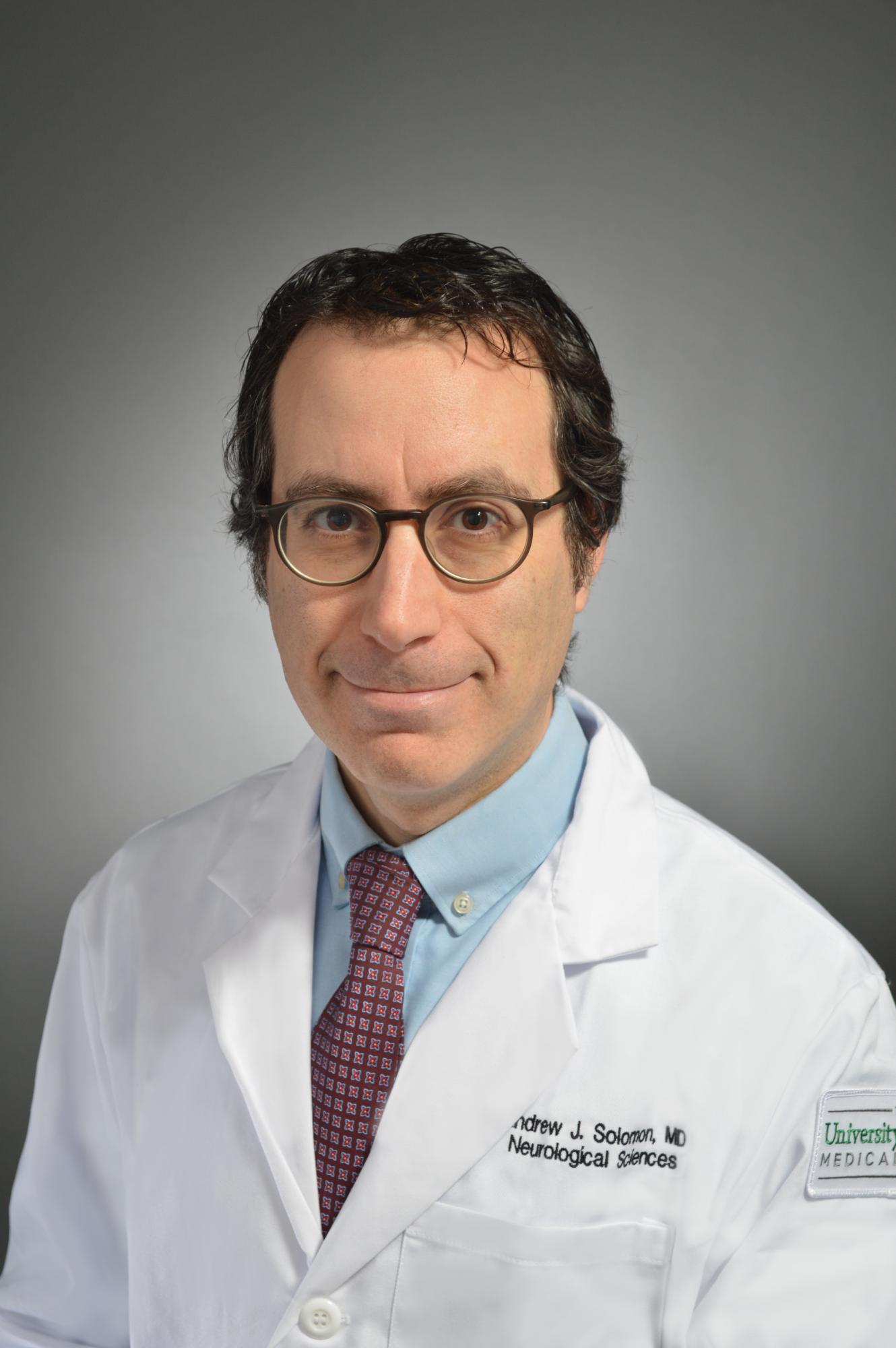

Interview with Andrew Solomon, MD, on diagnosing multiple sclerosis

Andrew Solomon, MD, is a neurologist and Associate Professor in the Department of Neurological Sciences and Division Chief of Multiple Sclerosis at The University of Vermont. We sat down to talk with Dr. Solomon about his experience with multiple sclerosis (MS) misdiagnosis and what can be done to improve MS diagnosis going forward.

How prevalent is the misdiagnosis of MS and what are the effects that it has on patients?

The first thing to clarify is what we mean by MS misdiagnosis. In this case, we’re talking about patients who are incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS. MS is hard to diagnose. Sometimes we take too long to diagnose people who have MS, sometimes we incorrectly diagnose MS in people who don’t have it.

We don’t have very good data in terms of how frequent misdiagnosis is, but we have some. The earliest data we have is from the 1980s. In 1988 there was a study published involving approximately 500 patients who had been diagnosed with MS in life and subsequently died between the 1960s and the 1980s and had a postmortem exam. 6% of those people who had a diagnosis of MS during their lifetime didn’t actually have MS.1

In 2012, we did a survey of 122 MS specialists.2 We asked them if they had encountered patients incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS in the past year, and 95% of them had seen such a patient. This was not the most scientific study because it was just a survey and subject to recall bias. Still, many of these MS providers recalled having seen three to ten such patients in the last year where they strongly felt that a pre-existing MS diagnosis made by another provider was incorrect.

Another study was recently published by Dr. Kaisey.3 She looked at referrals to two academic MS centers on the West Coast, and specifically new patient referrals over 12 months to those two MS centers. She found that out of 241 patients referred to the two MS centers, almost one in five who was referred with a pre-existing diagnosis of MS who came to these MS centers was subsequently found not have MS. This included 17% of patients at Cedars Sinai and 19% at UCLA. That’s an alarmingly high number of patients. And that’s the best data we have right now.

We don’t know how representative that number is of other MS centers and clinical practice nationally, but the bottom line is that misdiagnosis of MS is, unfortunately, fairly common and there’s a lot of risks to patients associated with misdiagnosis, as well as costs to our health care system.

Can you elaborate on the risks to patients?

We published a study where we looked at records from 110 patients who had been incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS. Twenty-three MS specialists from 4 different MS centers participated in this study that was published in Neurology in 2016.4

70% of these patients had been receiving disease modifying therapy for MS, which certainly has risks and side effects associated with it. 24% received disease modifying therapy with a known risk of PML, which is a frequently fatal brain infection associated with these therapies. Approximately 30% of these patients who did not have MS were on disease modifying therapy for in 3 to 9 years and 30% were on disease modifying therapy for 10 years or more.

Dr. Kaisey’s study also supports our findings. She found approximately 110 patient-years of exposure to unnecessary disease modifying therapy in the misdiagnosed patients in her study.3 Patients suffer side effects in addition to unnecessary risk related to these therapies.

It’s also important to emphasize that many of these patients also received inadequate treatment for their correct diagnoses.

How did the 2017 revision to the McDonald criteria address the challenge of MS diagnosis?

The problem of MS misdiagnosis is prominently discussed in the 2017 McDonald criteria.5 Unfortunately, one of the likely causes of misdiagnosis is that many clinicians may not read the full manuscript of the McDonald criteria itself. They instead rely on summary cards or reproductions—condensed versions of how to diagnose MS—which often don’t really provide the full context that would allow physicians to think critically and avoid a misdiagnosis.

MS is still a clinical diagnosis, which means we’re reliant on physician decision-making to confirm a diagnosis of MS. There are multiple steps to it.

First, we must determine if somebody has a syndrome typical for MS and they have objective evidence of a CNS lesion. After that the McDonald criteria can be applied to determine if they meet dissemination in time, dissemination in space, and have no other explanation for this syndrome before making a diagnosis of MS. Each one of those steps is reliant on thoughtful clinical decision-making and may be prone to potential error.

Knowing the ins and outs and the details of each of those steps is important. Reading the diagnostic criteria is probably the first step in becoming skilled at MS diagnosis. It’s important to know the criteria were not developed as a screening tool. The neurologist is essentially the screening tool. The diagnostic criteria can’t be used until a MS-typical syndrome with objective evidence of a CNS lesion is confirmed.

In what way was the previous criteria flawed?

I wouldn’t say any of the MS diagnostic criteria were flawed; they have evolved along with data in our field that has helped us make diagnosis of MS earlier in many patients. When using the criteria, it’s important to understand the types of patients in the cohorts used to validate our diagnostic criteria. They were primarily younger than 50, and usually Caucasian. They had only syndromes typical for MS with objective evidence of CNS damage corroborating these syndromes. Using the criteria more broadly in patients who do not fit this profile can reduce its specificity and lead to misdiagnosis.

For determination of MRI dissemination in time and dissemination space, there are also some misconceptions that frequently lead to misdiagnosis. Knowing which areas are required for dissemination in space in crucial. For example, the optic nerve currently is not an area that can be used to fulfill dissemination in space, which is a mistake people frequently make. Knowing that the terms “juxtacortical” and “periventricular” means touching the ventricle and touching the cortex is very important. This is a mistake that’s often made as well, and many disorders present with MRI lesions near but not touching the cortex or ventricle. Knowing each element of our diagnostic criteria and what those terms specifically mean is important. In the 2017 McDonald criteria there’s an excellent glossary that helps clinicians understand these terms and how to use them appropriately.5

What more needs to be done to prevent MS misdiagnosis?

First, we need to figure out how to better educate clinicians on how to use our diagnostic criteria appropriately.

We recently completed a study that suggests that residents in training, and even MS specialists, have trouble using the diagnostic criteria. This study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Annual meeting but has not been published yet. Education on how to use the diagnostic criteria, and in which patients to use the criteria (and in which patients the criteria do not apply) is important, particularly when new revisions to the diagnostic criteria are published.

We published a paper recently that provided guidance on how to avoid misdiagnosis using the 2017 McDonald criteria, and how to approach patients where the diagnostic criteria didn’t apply.6 Sometimes additional clinical, laboratory, or MRI evaluation and monitoring is required in such patients to either confirm a diagnosis of MS, or determine that a patient does not have MS.

We also desperately need biomarkers that may help us diagnose MS more accurately in patients who have neurological symptoms and an abnormal MRI and are seeing a neurologist for the first time. There’s research going on now to find relevant biomarkers in the form of blood tests, as well as MRI assessments. In particular, ongoing research focused on the MRI finding we have termed the “central vein sign” suggests this approach may be helpful as a MRI-specific biomarker for MS.7,8 We need multicenter studies evaluating this and other biomarkers in patients who come to our clinics for a new evaluation for MS, to confirm that they are accurate. We need more researchers working on how to improve diagnosis of MS.

References:

1. Engell T. A clinico-pathoanatomical study of multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;78(1):39-44.

2. Solomon AJ, Klein EP, Bourdette D. "Undiagnosing" multiple sclerosis: the challenge of misdiagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2012;78(24):1986-1991.

3. Kaisey M, Solomon AJ, Luu M, Giesser BS, Sicotte NL. Incidence of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis in referrals to two academic centers. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:51-56.

4. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

5. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173..

6. Solomon AJ, Naismith RT, Cross AH. Misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis: impact of the 2017 McDonald criteria on clinical practice. Neurology. 2019;92(1):26-33.

7. Sati P, Oh J, Constable RT, et al; NAIMS Cooperative. The central vein sign and its clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement from the North American Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis Cooperative. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(12):714-722.

8. Sinnecker T, Clarke MA, Meier D, et al. Evaluation of the central vein sign as a diagnostic imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis [published online ahead of print August 19, 2019]. JAMA Neurology. 2019: doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2478.

Andrew Solomon, MD, is a neurologist and Associate Professor in the Department of Neurological Sciences and Division Chief of Multiple Sclerosis at The University of Vermont. We sat down to talk with Dr. Solomon about his experience with multiple sclerosis (MS) misdiagnosis and what can be done to improve MS diagnosis going forward.

How prevalent is the misdiagnosis of MS and what are the effects that it has on patients?

The first thing to clarify is what we mean by MS misdiagnosis. In this case, we’re talking about patients who are incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS. MS is hard to diagnose. Sometimes we take too long to diagnose people who have MS, sometimes we incorrectly diagnose MS in people who don’t have it.

We don’t have very good data in terms of how frequent misdiagnosis is, but we have some. The earliest data we have is from the 1980s. In 1988 there was a study published involving approximately 500 patients who had been diagnosed with MS in life and subsequently died between the 1960s and the 1980s and had a postmortem exam. 6% of those people who had a diagnosis of MS during their lifetime didn’t actually have MS.1

In 2012, we did a survey of 122 MS specialists.2 We asked them if they had encountered patients incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS in the past year, and 95% of them had seen such a patient. This was not the most scientific study because it was just a survey and subject to recall bias. Still, many of these MS providers recalled having seen three to ten such patients in the last year where they strongly felt that a pre-existing MS diagnosis made by another provider was incorrect.

Another study was recently published by Dr. Kaisey.3 She looked at referrals to two academic MS centers on the West Coast, and specifically new patient referrals over 12 months to those two MS centers. She found that out of 241 patients referred to the two MS centers, almost one in five who was referred with a pre-existing diagnosis of MS who came to these MS centers was subsequently found not have MS. This included 17% of patients at Cedars Sinai and 19% at UCLA. That’s an alarmingly high number of patients. And that’s the best data we have right now.

We don’t know how representative that number is of other MS centers and clinical practice nationally, but the bottom line is that misdiagnosis of MS is, unfortunately, fairly common and there’s a lot of risks to patients associated with misdiagnosis, as well as costs to our health care system.

Can you elaborate on the risks to patients?

We published a study where we looked at records from 110 patients who had been incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS. Twenty-three MS specialists from 4 different MS centers participated in this study that was published in Neurology in 2016.4

70% of these patients had been receiving disease modifying therapy for MS, which certainly has risks and side effects associated with it. 24% received disease modifying therapy with a known risk of PML, which is a frequently fatal brain infection associated with these therapies. Approximately 30% of these patients who did not have MS were on disease modifying therapy for in 3 to 9 years and 30% were on disease modifying therapy for 10 years or more.

Dr. Kaisey’s study also supports our findings. She found approximately 110 patient-years of exposure to unnecessary disease modifying therapy in the misdiagnosed patients in her study.3 Patients suffer side effects in addition to unnecessary risk related to these therapies.

It’s also important to emphasize that many of these patients also received inadequate treatment for their correct diagnoses.

How did the 2017 revision to the McDonald criteria address the challenge of MS diagnosis?

The problem of MS misdiagnosis is prominently discussed in the 2017 McDonald criteria.5 Unfortunately, one of the likely causes of misdiagnosis is that many clinicians may not read the full manuscript of the McDonald criteria itself. They instead rely on summary cards or reproductions—condensed versions of how to diagnose MS—which often don’t really provide the full context that would allow physicians to think critically and avoid a misdiagnosis.

MS is still a clinical diagnosis, which means we’re reliant on physician decision-making to confirm a diagnosis of MS. There are multiple steps to it.

First, we must determine if somebody has a syndrome typical for MS and they have objective evidence of a CNS lesion. After that the McDonald criteria can be applied to determine if they meet dissemination in time, dissemination in space, and have no other explanation for this syndrome before making a diagnosis of MS. Each one of those steps is reliant on thoughtful clinical decision-making and may be prone to potential error.

Knowing the ins and outs and the details of each of those steps is important. Reading the diagnostic criteria is probably the first step in becoming skilled at MS diagnosis. It’s important to know the criteria were not developed as a screening tool. The neurologist is essentially the screening tool. The diagnostic criteria can’t be used until a MS-typical syndrome with objective evidence of a CNS lesion is confirmed.

In what way was the previous criteria flawed?

I wouldn’t say any of the MS diagnostic criteria were flawed; they have evolved along with data in our field that has helped us make diagnosis of MS earlier in many patients. When using the criteria, it’s important to understand the types of patients in the cohorts used to validate our diagnostic criteria. They were primarily younger than 50, and usually Caucasian. They had only syndromes typical for MS with objective evidence of CNS damage corroborating these syndromes. Using the criteria more broadly in patients who do not fit this profile can reduce its specificity and lead to misdiagnosis.

For determination of MRI dissemination in time and dissemination space, there are also some misconceptions that frequently lead to misdiagnosis. Knowing which areas are required for dissemination in space in crucial. For example, the optic nerve currently is not an area that can be used to fulfill dissemination in space, which is a mistake people frequently make. Knowing that the terms “juxtacortical” and “periventricular” means touching the ventricle and touching the cortex is very important. This is a mistake that’s often made as well, and many disorders present with MRI lesions near but not touching the cortex or ventricle. Knowing each element of our diagnostic criteria and what those terms specifically mean is important. In the 2017 McDonald criteria there’s an excellent glossary that helps clinicians understand these terms and how to use them appropriately.5

What more needs to be done to prevent MS misdiagnosis?

First, we need to figure out how to better educate clinicians on how to use our diagnostic criteria appropriately.

We recently completed a study that suggests that residents in training, and even MS specialists, have trouble using the diagnostic criteria. This study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Annual meeting but has not been published yet. Education on how to use the diagnostic criteria, and in which patients to use the criteria (and in which patients the criteria do not apply) is important, particularly when new revisions to the diagnostic criteria are published.

We published a paper recently that provided guidance on how to avoid misdiagnosis using the 2017 McDonald criteria, and how to approach patients where the diagnostic criteria didn’t apply.6 Sometimes additional clinical, laboratory, or MRI evaluation and monitoring is required in such patients to either confirm a diagnosis of MS, or determine that a patient does not have MS.

We also desperately need biomarkers that may help us diagnose MS more accurately in patients who have neurological symptoms and an abnormal MRI and are seeing a neurologist for the first time. There’s research going on now to find relevant biomarkers in the form of blood tests, as well as MRI assessments. In particular, ongoing research focused on the MRI finding we have termed the “central vein sign” suggests this approach may be helpful as a MRI-specific biomarker for MS.7,8 We need multicenter studies evaluating this and other biomarkers in patients who come to our clinics for a new evaluation for MS, to confirm that they are accurate. We need more researchers working on how to improve diagnosis of MS.

References:

1. Engell T. A clinico-pathoanatomical study of multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;78(1):39-44.

2. Solomon AJ, Klein EP, Bourdette D. "Undiagnosing" multiple sclerosis: the challenge of misdiagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2012;78(24):1986-1991.

3. Kaisey M, Solomon AJ, Luu M, Giesser BS, Sicotte NL. Incidence of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis in referrals to two academic centers. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:51-56.

4. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

5. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173..

6. Solomon AJ, Naismith RT, Cross AH. Misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis: impact of the 2017 McDonald criteria on clinical practice. Neurology. 2019;92(1):26-33.

7. Sati P, Oh J, Constable RT, et al; NAIMS Cooperative. The central vein sign and its clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement from the North American Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis Cooperative. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(12):714-722.

8. Sinnecker T, Clarke MA, Meier D, et al. Evaluation of the central vein sign as a diagnostic imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis [published online ahead of print August 19, 2019]. JAMA Neurology. 2019: doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2478.

Andrew Solomon, MD, is a neurologist and Associate Professor in the Department of Neurological Sciences and Division Chief of Multiple Sclerosis at The University of Vermont. We sat down to talk with Dr. Solomon about his experience with multiple sclerosis (MS) misdiagnosis and what can be done to improve MS diagnosis going forward.

How prevalent is the misdiagnosis of MS and what are the effects that it has on patients?

The first thing to clarify is what we mean by MS misdiagnosis. In this case, we’re talking about patients who are incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS. MS is hard to diagnose. Sometimes we take too long to diagnose people who have MS, sometimes we incorrectly diagnose MS in people who don’t have it.

We don’t have very good data in terms of how frequent misdiagnosis is, but we have some. The earliest data we have is from the 1980s. In 1988 there was a study published involving approximately 500 patients who had been diagnosed with MS in life and subsequently died between the 1960s and the 1980s and had a postmortem exam. 6% of those people who had a diagnosis of MS during their lifetime didn’t actually have MS.1

In 2012, we did a survey of 122 MS specialists.2 We asked them if they had encountered patients incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS in the past year, and 95% of them had seen such a patient. This was not the most scientific study because it was just a survey and subject to recall bias. Still, many of these MS providers recalled having seen three to ten such patients in the last year where they strongly felt that a pre-existing MS diagnosis made by another provider was incorrect.

Another study was recently published by Dr. Kaisey.3 She looked at referrals to two academic MS centers on the West Coast, and specifically new patient referrals over 12 months to those two MS centers. She found that out of 241 patients referred to the two MS centers, almost one in five who was referred with a pre-existing diagnosis of MS who came to these MS centers was subsequently found not have MS. This included 17% of patients at Cedars Sinai and 19% at UCLA. That’s an alarmingly high number of patients. And that’s the best data we have right now.

We don’t know how representative that number is of other MS centers and clinical practice nationally, but the bottom line is that misdiagnosis of MS is, unfortunately, fairly common and there’s a lot of risks to patients associated with misdiagnosis, as well as costs to our health care system.

Can you elaborate on the risks to patients?

We published a study where we looked at records from 110 patients who had been incorrectly assigned a diagnosis of MS. Twenty-three MS specialists from 4 different MS centers participated in this study that was published in Neurology in 2016.4

70% of these patients had been receiving disease modifying therapy for MS, which certainly has risks and side effects associated with it. 24% received disease modifying therapy with a known risk of PML, which is a frequently fatal brain infection associated with these therapies. Approximately 30% of these patients who did not have MS were on disease modifying therapy for in 3 to 9 years and 30% were on disease modifying therapy for 10 years or more.

Dr. Kaisey’s study also supports our findings. She found approximately 110 patient-years of exposure to unnecessary disease modifying therapy in the misdiagnosed patients in her study.3 Patients suffer side effects in addition to unnecessary risk related to these therapies.

It’s also important to emphasize that many of these patients also received inadequate treatment for their correct diagnoses.

How did the 2017 revision to the McDonald criteria address the challenge of MS diagnosis?

The problem of MS misdiagnosis is prominently discussed in the 2017 McDonald criteria.5 Unfortunately, one of the likely causes of misdiagnosis is that many clinicians may not read the full manuscript of the McDonald criteria itself. They instead rely on summary cards or reproductions—condensed versions of how to diagnose MS—which often don’t really provide the full context that would allow physicians to think critically and avoid a misdiagnosis.

MS is still a clinical diagnosis, which means we’re reliant on physician decision-making to confirm a diagnosis of MS. There are multiple steps to it.

First, we must determine if somebody has a syndrome typical for MS and they have objective evidence of a CNS lesion. After that the McDonald criteria can be applied to determine if they meet dissemination in time, dissemination in space, and have no other explanation for this syndrome before making a diagnosis of MS. Each one of those steps is reliant on thoughtful clinical decision-making and may be prone to potential error.

Knowing the ins and outs and the details of each of those steps is important. Reading the diagnostic criteria is probably the first step in becoming skilled at MS diagnosis. It’s important to know the criteria were not developed as a screening tool. The neurologist is essentially the screening tool. The diagnostic criteria can’t be used until a MS-typical syndrome with objective evidence of a CNS lesion is confirmed.

In what way was the previous criteria flawed?

I wouldn’t say any of the MS diagnostic criteria were flawed; they have evolved along with data in our field that has helped us make diagnosis of MS earlier in many patients. When using the criteria, it’s important to understand the types of patients in the cohorts used to validate our diagnostic criteria. They were primarily younger than 50, and usually Caucasian. They had only syndromes typical for MS with objective evidence of CNS damage corroborating these syndromes. Using the criteria more broadly in patients who do not fit this profile can reduce its specificity and lead to misdiagnosis.

For determination of MRI dissemination in time and dissemination space, there are also some misconceptions that frequently lead to misdiagnosis. Knowing which areas are required for dissemination in space in crucial. For example, the optic nerve currently is not an area that can be used to fulfill dissemination in space, which is a mistake people frequently make. Knowing that the terms “juxtacortical” and “periventricular” means touching the ventricle and touching the cortex is very important. This is a mistake that’s often made as well, and many disorders present with MRI lesions near but not touching the cortex or ventricle. Knowing each element of our diagnostic criteria and what those terms specifically mean is important. In the 2017 McDonald criteria there’s an excellent glossary that helps clinicians understand these terms and how to use them appropriately.5

What more needs to be done to prevent MS misdiagnosis?

First, we need to figure out how to better educate clinicians on how to use our diagnostic criteria appropriately.

We recently completed a study that suggests that residents in training, and even MS specialists, have trouble using the diagnostic criteria. This study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Annual meeting but has not been published yet. Education on how to use the diagnostic criteria, and in which patients to use the criteria (and in which patients the criteria do not apply) is important, particularly when new revisions to the diagnostic criteria are published.

We published a paper recently that provided guidance on how to avoid misdiagnosis using the 2017 McDonald criteria, and how to approach patients where the diagnostic criteria didn’t apply.6 Sometimes additional clinical, laboratory, or MRI evaluation and monitoring is required in such patients to either confirm a diagnosis of MS, or determine that a patient does not have MS.

We also desperately need biomarkers that may help us diagnose MS more accurately in patients who have neurological symptoms and an abnormal MRI and are seeing a neurologist for the first time. There’s research going on now to find relevant biomarkers in the form of blood tests, as well as MRI assessments. In particular, ongoing research focused on the MRI finding we have termed the “central vein sign” suggests this approach may be helpful as a MRI-specific biomarker for MS.7,8 We need multicenter studies evaluating this and other biomarkers in patients who come to our clinics for a new evaluation for MS, to confirm that they are accurate. We need more researchers working on how to improve diagnosis of MS.

References:

1. Engell T. A clinico-pathoanatomical study of multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;78(1):39-44.

2. Solomon AJ, Klein EP, Bourdette D. "Undiagnosing" multiple sclerosis: the challenge of misdiagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2012;78(24):1986-1991.

3. Kaisey M, Solomon AJ, Luu M, Giesser BS, Sicotte NL. Incidence of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis in referrals to two academic centers. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:51-56.

4. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

5. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173..

6. Solomon AJ, Naismith RT, Cross AH. Misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis: impact of the 2017 McDonald criteria on clinical practice. Neurology. 2019;92(1):26-33.

7. Sati P, Oh J, Constable RT, et al; NAIMS Cooperative. The central vein sign and its clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement from the North American Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis Cooperative. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(12):714-722.

8. Sinnecker T, Clarke MA, Meier D, et al. Evaluation of the central vein sign as a diagnostic imaging biomarker in multiple sclerosis [published online ahead of print August 19, 2019]. JAMA Neurology. 2019: doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2478.

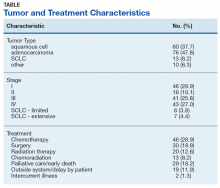

Open Clinical Trials for Patients With Lung Cancers (FULL)

Providing access to clinical trials for veteran and active-duty military patients can be a challenge, but a significant number of trials are now recruiting patients from those patient populations. Many trials explicitly recruit patients from the VA, the military, and IHS. The VA Office of Research and Development alone sponsors or cosponsors nearly 1,000 research initiatives, and many more are sponsored by Walter Reed National Medical Center and other major defense and VA facilities. The clinical trials listed below are all open as of August 1, 201 8 ; have at least 1 VA, DoD, or IHS location recruiting patients; and are focused on treatment for colorectal cancer. For additional information and full inclusion/exclusion criteria, please consult clinicaltrials.gov.

Lung-MAP (multiple trials)

Lung-MAP (SWOG S1400) is a multidrug, multi-substudy, biomarker-driven squamous cell lung cancer clinical trial that uses state-of-the-art genomic profiling to match patients to substudies testing investigational treatments that may target the genomic alterations, or mutations, found to be driving the growth of their cancer.

ID: NCT02154490, NCT02595944, NCT02766335, NCT02785913, NCT02785939, NCT02926638, NCT02965378, NCT03373760, NCT03377556

Sponsor: Southwest Oncology Group

Locations: VA Connecticut Healthcare System-West Haven Campus; Hines VA Hospital, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Ann Arbor VAMC, Michigan; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA New Jersey Health Care System, East Orange; Michael E. DeBakey VAMC Houston, Texas

ALCHEMIST: Adjuvant Lung Cancer Enrichment Marker Identification and Sequencing Trials (multiple trials)

A group of randomized clinical trials for patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer whose tumors have been completely removed by surgery.

ID: NCT02193282, NCT02194738, NCT02201992, NCT02595944

Sponsor: National Cancer Institute

Locations: Little Rock VAMC, Arkansas; VA Connecticut Healthcare System West Haven Campus; Atlanta VAMC, Decatur, Georgia; Hines VA Hospital, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Minneapolis VAMC, Minnesota; Saint Louis VAMC, Missouri; Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System-Brooklyn Campus; Dayton VAMC, Ohio; William S. Middleton VAMC, Madison, Wisconsin

Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Or Stereotactic Radiotherapy (VALOR)

The standard of care for stage I non-small cell lung cancer has historically been surgical resection in patients who are medically fit to tolerate an operation. Recent data now suggests that stereotactic radiotherapy may be a suitable alternative. This includes the results from a pooled analysis of two incomplete phase III studies that reported a 15% overall survival advantage with stereotactic radiotherapy at 3 years. While these data are promising, the median follow-up period was short, the results underpowered, and the findings were in contradiction to multiple retrospective studies that demonstrate the outcomes with surgery are likely equal or superior. Therefore, the herein trial aims to evaluate these two treatments in a prospective randomized fashion with a goal to compare the overall survival beyond 5 years. It has been designed to enroll patients who have a long life-expectancy, and are fit enough to tolerate an anatomic pulmonary resection with intraoperative lymph node sampling.

ID: NCT02984761

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana; Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Minnesota; Durham VAMC, North Carolina; Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, Texas; Hunter Holmes McGuire VA Medical Center, Richmond, Virginia

Naloxegol in Treating Patients With Stage IIIB-IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

This randomized pilot clinical trial studies the side effects and best dose of naloxegol and to see how well it works in treating patients with stage IIIB-IV non-small cell lung cancer. Naloxegol may relieve some of the side effects of opioid pain medication and fight off future growth in the cancer.

ID: NCT03087708

Sponsor: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Locations: Minneapolis VAMC, Minnesota; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA Western New York Health Care System-Buffalo; Salisbury VAMC, North Carolina

Palliative Care Interventions for Outpatients Newly Diagnosed With Lung Cancer: Phase II (PCI2)

The focus of the study is to test a nurse-led telephone-based palliative care intervention on improving the delivery of care for patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. The study is a three site randomized control trial to determine the efficacy of the intervention on improving patients’ quality of life, symptom burden, and satisfaction of care. Additionally, the study will test an innovative care delivery model to improve patients’ access to palliative care. The investigators will also determine the effect of the intervention on patient activation to discuss treatment preferences with their clinician and on clinician knowledge of patients’ goals of care.

ID: NCT03007953

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: Birmingham VAMC, Alabama; VA Portland Health Care System, Oregon; VA Puget Sound Health Care System Seattle Division, Washington

Radiation Therapy Regimens in Treating Patients With Limited-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Cisplatin and Etoposide

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays to kill tumor cells. Drugs used in chemotherapy, such as etoposide, carboplatin and cisplatin, work in different ways to stop the growth of tumor cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. It is not yet known which radiation therapy regimen is more effective when given together with chemotherapy in treating patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer. This randomized phase III trial is comparing different chest radiation therapy regimens to see how well they work in treating patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer.

ID: NCT00632853

Sponsor: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Locations: Baltimore VAMC, Maryland; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA Western New York Health Care System, Buffalo, New York; Dayton VAMC, Ohio; Zablocki VAMC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Comparison of Different Types of Surgery in Treating Patients With Stage IA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Wedge resection or segmentectomy may be less invasive types of surgery than lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer and may have fewer side effects and improve recovery. It is not yet known whether wedge resection or segmentectomy are more effective than lobectomy in treating stage IA non-small cell lung cancer.

ID: NCT00499330

Sponsor: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Locations: VA Loma Linda Healthcare System, California; VA Long Beach Medical Center, California; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Portland VAMC, Oregon

Lung Cancer Screening Decisions (VA-LCSDecTool)

Veterans have a high risk of developing lung in comparison to general populations due to their older age and smoking history. Recent evidence indicates that lung cancer screening with low dose CT scan reduces lung cancer mortality among older heavy smokers. However, the rates of false positive findings are high, requiring further testing and evaluation. Preliminary studies report that while some Veterans are enthusiastic about screening, others are highly reluctant. Patient preferences should be considered as part of an informed decision making process for this emerging paradigm of lung cancer control. Effective methods for preference assessment among Veterans have not yet been developed, evaluated, and integrated into clinical practice. The specific aims of this study are to 1) elicit patient and provider stakeholder input to inform the development of a lung cancer screening decision tool, 2) develop a web based Lung Cancer Screening Decision Tool (LCSDecTool) that incorporates patient and provider input, and 3) evaluate the impact of the LCSDecTool compared to usual care on the decision process, clinical outcomes, and quality of life.

ID

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: VA Connecticut Healthcare System West Haven Campus; Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Molecular Predictors of Cancer in Patients at High Risk of Lung Cancer

Using samples of blood, urine, sputum, and lung tissue from patients at high risk of cancer for laboratory studies may help doctors learn more about changes that may occur in DNA and identify biomarkers related to cancer.

ID: NCT00898313

Sponsor: Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

Location: VAMC Nashville, Tennessee

Improving Supportive Care for Patients With Thoracic Malignancies

The purpose of this study is to use a proactive approach to improve symptom management of patients with thoracic malignancies. In this pilot study, the investigators propose to evaluate the feasibility of using outbound, proactive telephone symptom assessment strategies and measure the efficacy of this approach on patient satisfaction with their care, patient activation, quality of life and use of healthcare resources.

ID: NCT03216109

Sponsor: Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research

Location: VA Palo Alto Health Care System, California

Providing access to clinical trials for veteran and active-duty military patients can be a challenge, but a significant number of trials are now recruiting patients from those patient populations. Many trials explicitly recruit patients from the VA, the military, and IHS. The VA Office of Research and Development alone sponsors or cosponsors nearly 1,000 research initiatives, and many more are sponsored by Walter Reed National Medical Center and other major defense and VA facilities. The clinical trials listed below are all open as of August 1, 201 8 ; have at least 1 VA, DoD, or IHS location recruiting patients; and are focused on treatment for colorectal cancer. For additional information and full inclusion/exclusion criteria, please consult clinicaltrials.gov.

Lung-MAP (multiple trials)

Lung-MAP (SWOG S1400) is a multidrug, multi-substudy, biomarker-driven squamous cell lung cancer clinical trial that uses state-of-the-art genomic profiling to match patients to substudies testing investigational treatments that may target the genomic alterations, or mutations, found to be driving the growth of their cancer.

ID: NCT02154490, NCT02595944, NCT02766335, NCT02785913, NCT02785939, NCT02926638, NCT02965378, NCT03373760, NCT03377556

Sponsor: Southwest Oncology Group

Locations: VA Connecticut Healthcare System-West Haven Campus; Hines VA Hospital, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Ann Arbor VAMC, Michigan; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA New Jersey Health Care System, East Orange; Michael E. DeBakey VAMC Houston, Texas

ALCHEMIST: Adjuvant Lung Cancer Enrichment Marker Identification and Sequencing Trials (multiple trials)

A group of randomized clinical trials for patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer whose tumors have been completely removed by surgery.

ID: NCT02193282, NCT02194738, NCT02201992, NCT02595944

Sponsor: National Cancer Institute

Locations: Little Rock VAMC, Arkansas; VA Connecticut Healthcare System West Haven Campus; Atlanta VAMC, Decatur, Georgia; Hines VA Hospital, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Minneapolis VAMC, Minnesota; Saint Louis VAMC, Missouri; Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System-Brooklyn Campus; Dayton VAMC, Ohio; William S. Middleton VAMC, Madison, Wisconsin

Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Or Stereotactic Radiotherapy (VALOR)

The standard of care for stage I non-small cell lung cancer has historically been surgical resection in patients who are medically fit to tolerate an operation. Recent data now suggests that stereotactic radiotherapy may be a suitable alternative. This includes the results from a pooled analysis of two incomplete phase III studies that reported a 15% overall survival advantage with stereotactic radiotherapy at 3 years. While these data are promising, the median follow-up period was short, the results underpowered, and the findings were in contradiction to multiple retrospective studies that demonstrate the outcomes with surgery are likely equal or superior. Therefore, the herein trial aims to evaluate these two treatments in a prospective randomized fashion with a goal to compare the overall survival beyond 5 years. It has been designed to enroll patients who have a long life-expectancy, and are fit enough to tolerate an anatomic pulmonary resection with intraoperative lymph node sampling.

ID: NCT02984761

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana; Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Minnesota; Durham VAMC, North Carolina; Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, Texas; Hunter Holmes McGuire VA Medical Center, Richmond, Virginia

Naloxegol in Treating Patients With Stage IIIB-IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

This randomized pilot clinical trial studies the side effects and best dose of naloxegol and to see how well it works in treating patients with stage IIIB-IV non-small cell lung cancer. Naloxegol may relieve some of the side effects of opioid pain medication and fight off future growth in the cancer.

ID: NCT03087708

Sponsor: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Locations: Minneapolis VAMC, Minnesota; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA Western New York Health Care System-Buffalo; Salisbury VAMC, North Carolina

Palliative Care Interventions for Outpatients Newly Diagnosed With Lung Cancer: Phase II (PCI2)

The focus of the study is to test a nurse-led telephone-based palliative care intervention on improving the delivery of care for patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. The study is a three site randomized control trial to determine the efficacy of the intervention on improving patients’ quality of life, symptom burden, and satisfaction of care. Additionally, the study will test an innovative care delivery model to improve patients’ access to palliative care. The investigators will also determine the effect of the intervention on patient activation to discuss treatment preferences with their clinician and on clinician knowledge of patients’ goals of care.

ID: NCT03007953

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: Birmingham VAMC, Alabama; VA Portland Health Care System, Oregon; VA Puget Sound Health Care System Seattle Division, Washington

Radiation Therapy Regimens in Treating Patients With Limited-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Cisplatin and Etoposide

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays to kill tumor cells. Drugs used in chemotherapy, such as etoposide, carboplatin and cisplatin, work in different ways to stop the growth of tumor cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. It is not yet known which radiation therapy regimen is more effective when given together with chemotherapy in treating patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer. This randomized phase III trial is comparing different chest radiation therapy regimens to see how well they work in treating patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer.

ID: NCT00632853

Sponsor: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Locations: Baltimore VAMC, Maryland; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA Western New York Health Care System, Buffalo, New York; Dayton VAMC, Ohio; Zablocki VAMC, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Comparison of Different Types of Surgery in Treating Patients With Stage IA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Wedge resection or segmentectomy may be less invasive types of surgery than lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer and may have fewer side effects and improve recovery. It is not yet known whether wedge resection or segmentectomy are more effective than lobectomy in treating stage IA non-small cell lung cancer.

ID: NCT00499330

Sponsor: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Locations: VA Loma Linda Healthcare System, California; VA Long Beach Medical Center, California; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Portland VAMC, Oregon

Lung Cancer Screening Decisions (VA-LCSDecTool)

Veterans have a high risk of developing lung in comparison to general populations due to their older age and smoking history. Recent evidence indicates that lung cancer screening with low dose CT scan reduces lung cancer mortality among older heavy smokers. However, the rates of false positive findings are high, requiring further testing and evaluation. Preliminary studies report that while some Veterans are enthusiastic about screening, others are highly reluctant. Patient preferences should be considered as part of an informed decision making process for this emerging paradigm of lung cancer control. Effective methods for preference assessment among Veterans have not yet been developed, evaluated, and integrated into clinical practice. The specific aims of this study are to 1) elicit patient and provider stakeholder input to inform the development of a lung cancer screening decision tool, 2) develop a web based Lung Cancer Screening Decision Tool (LCSDecTool) that incorporates patient and provider input, and 3) evaluate the impact of the LCSDecTool compared to usual care on the decision process, clinical outcomes, and quality of life.

ID

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: VA Connecticut Healthcare System West Haven Campus; Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Molecular Predictors of Cancer in Patients at High Risk of Lung Cancer

Using samples of blood, urine, sputum, and lung tissue from patients at high risk of cancer for laboratory studies may help doctors learn more about changes that may occur in DNA and identify biomarkers related to cancer.

ID: NCT00898313

Sponsor: Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

Location: VAMC Nashville, Tennessee

Improving Supportive Care for Patients With Thoracic Malignancies

The purpose of this study is to use a proactive approach to improve symptom management of patients with thoracic malignancies. In this pilot study, the investigators propose to evaluate the feasibility of using outbound, proactive telephone symptom assessment strategies and measure the efficacy of this approach on patient satisfaction with their care, patient activation, quality of life and use of healthcare resources.

ID: NCT03216109

Sponsor: Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research

Location: VA Palo Alto Health Care System, California

Providing access to clinical trials for veteran and active-duty military patients can be a challenge, but a significant number of trials are now recruiting patients from those patient populations. Many trials explicitly recruit patients from the VA, the military, and IHS. The VA Office of Research and Development alone sponsors or cosponsors nearly 1,000 research initiatives, and many more are sponsored by Walter Reed National Medical Center and other major defense and VA facilities. The clinical trials listed below are all open as of August 1, 201 8 ; have at least 1 VA, DoD, or IHS location recruiting patients; and are focused on treatment for colorectal cancer. For additional information and full inclusion/exclusion criteria, please consult clinicaltrials.gov.

Lung-MAP (multiple trials)

Lung-MAP (SWOG S1400) is a multidrug, multi-substudy, biomarker-driven squamous cell lung cancer clinical trial that uses state-of-the-art genomic profiling to match patients to substudies testing investigational treatments that may target the genomic alterations, or mutations, found to be driving the growth of their cancer.

ID: NCT02154490, NCT02595944, NCT02766335, NCT02785913, NCT02785939, NCT02926638, NCT02965378, NCT03373760, NCT03377556

Sponsor: Southwest Oncology Group

Locations: VA Connecticut Healthcare System-West Haven Campus; Hines VA Hospital, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Ann Arbor VAMC, Michigan; Kansas City VAMC, Missouri; VA New Jersey Health Care System, East Orange; Michael E. DeBakey VAMC Houston, Texas

ALCHEMIST: Adjuvant Lung Cancer Enrichment Marker Identification and Sequencing Trials (multiple trials)

A group of randomized clinical trials for patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer whose tumors have been completely removed by surgery.

ID: NCT02193282, NCT02194738, NCT02201992, NCT02595944

Sponsor: National Cancer Institute

Locations: Little Rock VAMC, Arkansas; VA Connecticut Healthcare System West Haven Campus; Atlanta VAMC, Decatur, Georgia; Hines VA Hospital, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VAMC, Indianapolis, Indiana; Minneapolis VAMC, Minnesota; Saint Louis VAMC, Missouri; Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System-Brooklyn Campus; Dayton VAMC, Ohio; William S. Middleton VAMC, Madison, Wisconsin

Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Or Stereotactic Radiotherapy (VALOR)

The standard of care for stage I non-small cell lung cancer has historically been surgical resection in patients who are medically fit to tolerate an operation. Recent data now suggests that stereotactic radiotherapy may be a suitable alternative. This includes the results from a pooled analysis of two incomplete phase III studies that reported a 15% overall survival advantage with stereotactic radiotherapy at 3 years. While these data are promising, the median follow-up period was short, the results underpowered, and the findings were in contradiction to multiple retrospective studies that demonstrate the outcomes with surgery are likely equal or superior. Therefore, the herein trial aims to evaluate these two treatments in a prospective randomized fashion with a goal to compare the overall survival beyond 5 years. It has been designed to enroll patients who have a long life-expectancy, and are fit enough to tolerate an anatomic pulmonary resection with intraoperative lymph node sampling.

ID: NCT02984761

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois; Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana; Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Minnesota; Durham VAMC, North Carolina; Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, Texas; Hunter Holmes McGuire VA Medical Center, Richmond, Virginia

Naloxegol in Treating Patients With Stage IIIB-IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer