User login

HF an added risk in COVID-19, regardless of ejection fraction

People with a history of heart failure – no matter the type – face more complications and death than their peers without HF once hospitalized with COVID-19, a new observational study shows.

A history of HF was associated with a near doubling risk of in-hospital mortality and ICU care and more than a tripling risk of mechanical ventilation despite adjustment for 18 factors including race, obesity, diabetes, previous treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, and severity of illness.

Adverse outcomes were high regardless of whether patients had HF with a preserved, mid-range, or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF/HFmrEF/HFrEF).

“That for me was the real zinger,” senior author Anuradha Lala, MD, said in an interview . “Because as clinicians, oftentimes, and wrongly so, we think this person has preserved ejection fraction, so they’re not needing my heart failure expertise as much as someone with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.”

In the peak of the pandemic, that may have meant triaging patients with HFpEF to a regular floor, whereas those with HFrEF were seen by the specialist team.

“What this alerted me to is to take heart failure as a diagnosis very seriously, regardless of ejection fraction, and that is very much in line with all of the emerging data about heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” said Dr. Lala, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“Now when I see patients in the clinic, I incorporate part of our visit to talking about what they are doing to prevent COVID, which I really wasn’t doing before. It was like ‘Oh yeah, what crazy times we’re dealing with’ and then addressing their heart failure as I normally would,” she said. “But now, interwoven into every visit is: Are you wearing a mask, what’s your social distancing policy, who are you living with at home, has anyone at home or who you’ve interacted with been sick? I’m asking those questions just as a knee-jerk reaction for these patients because I know the repercussions. We have to keep in mind these are observational studies, so I can’t prove causality but these are observations that are, nonetheless, quite robust.”

Although cardiovascular disease, including HF, is recognized as a risk factor for worse outcomes in COVID-19 patients, data are sparse on the clinical course and prognosis of patients with preexisting HF.

“I would have expected that there would have been a gradation of risk from the people with very low ejection fractions up into the normal range, but here it didn’t seem to matter at all. So that’s an important point that bad outcomes were independent of ejection fraction,” commented Lee Goldberg, MD, professor of medicine and chief of advanced heart failure and cardiac transplant at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The study also validated that there is no association between use of RAAS inhibitors and bad outcomes in patients with COVID-19, he said.

Although this has been demonstrated in several studies, concerns were raised early in the pandemic that ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers could facilitate infection with SARS-CoV-2 and increase the risk of severe or lethal COVID-19.

“For most clinicians that question has been put to bed, but we’re still getting patients that will ask during office visits ‘Is it safe for me to stay on?’ They still have that doubt [about] ‘Are we doing the right thing?’ ” Dr. Goldberg said.

“We can reassure them now. A lot of us are able to say there’s nothing to that, we’re very clear about this, stay on the meds. If anything, there’s data that suggest actually it may be better to be on an ACE inhibitor; that the hospitalizations were shorter and the outcomes were a little bit better.”

For the current study, published online Oct. 28 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators analyzed 6,439 patients admitted for COVID-19 at one of five Mount Sinai Health System hospitals in New York between Feb. 27 and June 26. Their mean age was 65.3 years, 45% were women, and one-third were treated with RAAS inhibitors before admission.

Using ICD-9/10 codes and individual chart review, HF was identified in 422 patients (6.6%), of which 250 patients had HFpEF (≥50%), 44 had HFmrEF (41%-49%), and 128 had HFrEF (≤40%).

Patients with HFpEF were older, more frequently women with a higher body mass index and history of lung disease than patients with HFrEF, whereas those with HFmrEF fell in between.

The HFpEF group was also treated with hydroxychloroquine or macrolides and noninvasive ventilation more frequently than the other two groups, whereas antiplatelet and neurohormonal therapies were more common in the HFrEF group.

Patients with a history of HF had significantly longer hospital stays than those without HF (8 days vs. 6 days), increased need for intubation (22.8% vs. 11.9%) and ICU care (23.2% vs. 16.6%), and worse in-hospital mortality (40% vs. 24.9%).

After multivariable regression adjustment, HF persisted as an independent risk factor for ICU care (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.25-2.34), intubation and mechanical ventilation (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 2.56-5.16), and in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.27-2.78).

“I knew to expect higher rates of adverse outcomes but I didn’t expect it to be nearly a twofold increase,” Dr. Lala said. “I thought that was pretty powerful.”

No significant differences were seen across LVEF categories in length of stay, need for ICU care, intubation and mechanical ventilation, acute kidney injury, shock, thromboembolic events, arrhythmias, or 30-day readmission rates.

However, cardiogenic shock (7.8% vs. 2.3% vs. 2%) and HF-related causes for 30-day readmissions (47.1% vs. 0% vs. 8.6%) were significantly higher in patients with HFrEF than in those with HFmrEF or HFpEF.

Also, mortality was lower in those with HFmrEF (22.7%) than with HFrEF (38.3%) and HFpEF (44%). The group was small but the “results suggested that patients with HFmrEF could have a better prognosis, because they can represent a distinct and more favorable HF phenotype,” the authors wrote.

The statistical testing didn’t show much difference and the patient numbers were very small, noted Dr. Goldberg. “So they might be overreaching a little bit there.”

“To me, the take-home message is that just having the phenotype of heart failure, regardless of EF, is associated with bad outcomes and we need to be vigilant on two fronts,” he said. “We really need to be doing prevention in the folks with heart failure because if they get COVID their outcomes are not going to be as good. Second, as clinicians, if we see a patient presenting with COVID who has a history of heart failure we may want to be much more vigilant with that individual than we might otherwise be. So I think there’s something to be said for kind of risk-stratifying people in that way.”

Dr. Goldberg pointed out that the study had many “amazing strengths,” including a large, racially diverse population, direct chart review to identify HF patients, and capturing a patient’s specific HF phenotype.

Weaknesses are that it was a single-center study, so the biases of how these patients were treated are not easily controlled for, he said. “We also don’t know when the hospital system was very strained as they were making some decisions: Were the older patients who had advanced heart and lung disease ultimately less aggressively treated because they felt they wouldn’t survive?”

Dr. Lala has received personal fees from Zoll, outside the submitted work. Dr. Goldberg reported research funding with Respicardia and consulting fees from Abbott.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with a history of heart failure – no matter the type – face more complications and death than their peers without HF once hospitalized with COVID-19, a new observational study shows.

A history of HF was associated with a near doubling risk of in-hospital mortality and ICU care and more than a tripling risk of mechanical ventilation despite adjustment for 18 factors including race, obesity, diabetes, previous treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, and severity of illness.

Adverse outcomes were high regardless of whether patients had HF with a preserved, mid-range, or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF/HFmrEF/HFrEF).

“That for me was the real zinger,” senior author Anuradha Lala, MD, said in an interview . “Because as clinicians, oftentimes, and wrongly so, we think this person has preserved ejection fraction, so they’re not needing my heart failure expertise as much as someone with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.”

In the peak of the pandemic, that may have meant triaging patients with HFpEF to a regular floor, whereas those with HFrEF were seen by the specialist team.

“What this alerted me to is to take heart failure as a diagnosis very seriously, regardless of ejection fraction, and that is very much in line with all of the emerging data about heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” said Dr. Lala, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“Now when I see patients in the clinic, I incorporate part of our visit to talking about what they are doing to prevent COVID, which I really wasn’t doing before. It was like ‘Oh yeah, what crazy times we’re dealing with’ and then addressing their heart failure as I normally would,” she said. “But now, interwoven into every visit is: Are you wearing a mask, what’s your social distancing policy, who are you living with at home, has anyone at home or who you’ve interacted with been sick? I’m asking those questions just as a knee-jerk reaction for these patients because I know the repercussions. We have to keep in mind these are observational studies, so I can’t prove causality but these are observations that are, nonetheless, quite robust.”

Although cardiovascular disease, including HF, is recognized as a risk factor for worse outcomes in COVID-19 patients, data are sparse on the clinical course and prognosis of patients with preexisting HF.

“I would have expected that there would have been a gradation of risk from the people with very low ejection fractions up into the normal range, but here it didn’t seem to matter at all. So that’s an important point that bad outcomes were independent of ejection fraction,” commented Lee Goldberg, MD, professor of medicine and chief of advanced heart failure and cardiac transplant at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The study also validated that there is no association between use of RAAS inhibitors and bad outcomes in patients with COVID-19, he said.

Although this has been demonstrated in several studies, concerns were raised early in the pandemic that ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers could facilitate infection with SARS-CoV-2 and increase the risk of severe or lethal COVID-19.

“For most clinicians that question has been put to bed, but we’re still getting patients that will ask during office visits ‘Is it safe for me to stay on?’ They still have that doubt [about] ‘Are we doing the right thing?’ ” Dr. Goldberg said.

“We can reassure them now. A lot of us are able to say there’s nothing to that, we’re very clear about this, stay on the meds. If anything, there’s data that suggest actually it may be better to be on an ACE inhibitor; that the hospitalizations were shorter and the outcomes were a little bit better.”

For the current study, published online Oct. 28 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators analyzed 6,439 patients admitted for COVID-19 at one of five Mount Sinai Health System hospitals in New York between Feb. 27 and June 26. Their mean age was 65.3 years, 45% were women, and one-third were treated with RAAS inhibitors before admission.

Using ICD-9/10 codes and individual chart review, HF was identified in 422 patients (6.6%), of which 250 patients had HFpEF (≥50%), 44 had HFmrEF (41%-49%), and 128 had HFrEF (≤40%).

Patients with HFpEF were older, more frequently women with a higher body mass index and history of lung disease than patients with HFrEF, whereas those with HFmrEF fell in between.

The HFpEF group was also treated with hydroxychloroquine or macrolides and noninvasive ventilation more frequently than the other two groups, whereas antiplatelet and neurohormonal therapies were more common in the HFrEF group.

Patients with a history of HF had significantly longer hospital stays than those without HF (8 days vs. 6 days), increased need for intubation (22.8% vs. 11.9%) and ICU care (23.2% vs. 16.6%), and worse in-hospital mortality (40% vs. 24.9%).

After multivariable regression adjustment, HF persisted as an independent risk factor for ICU care (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.25-2.34), intubation and mechanical ventilation (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 2.56-5.16), and in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.27-2.78).

“I knew to expect higher rates of adverse outcomes but I didn’t expect it to be nearly a twofold increase,” Dr. Lala said. “I thought that was pretty powerful.”

No significant differences were seen across LVEF categories in length of stay, need for ICU care, intubation and mechanical ventilation, acute kidney injury, shock, thromboembolic events, arrhythmias, or 30-day readmission rates.

However, cardiogenic shock (7.8% vs. 2.3% vs. 2%) and HF-related causes for 30-day readmissions (47.1% vs. 0% vs. 8.6%) were significantly higher in patients with HFrEF than in those with HFmrEF or HFpEF.

Also, mortality was lower in those with HFmrEF (22.7%) than with HFrEF (38.3%) and HFpEF (44%). The group was small but the “results suggested that patients with HFmrEF could have a better prognosis, because they can represent a distinct and more favorable HF phenotype,” the authors wrote.

The statistical testing didn’t show much difference and the patient numbers were very small, noted Dr. Goldberg. “So they might be overreaching a little bit there.”

“To me, the take-home message is that just having the phenotype of heart failure, regardless of EF, is associated with bad outcomes and we need to be vigilant on two fronts,” he said. “We really need to be doing prevention in the folks with heart failure because if they get COVID their outcomes are not going to be as good. Second, as clinicians, if we see a patient presenting with COVID who has a history of heart failure we may want to be much more vigilant with that individual than we might otherwise be. So I think there’s something to be said for kind of risk-stratifying people in that way.”

Dr. Goldberg pointed out that the study had many “amazing strengths,” including a large, racially diverse population, direct chart review to identify HF patients, and capturing a patient’s specific HF phenotype.

Weaknesses are that it was a single-center study, so the biases of how these patients were treated are not easily controlled for, he said. “We also don’t know when the hospital system was very strained as they were making some decisions: Were the older patients who had advanced heart and lung disease ultimately less aggressively treated because they felt they wouldn’t survive?”

Dr. Lala has received personal fees from Zoll, outside the submitted work. Dr. Goldberg reported research funding with Respicardia and consulting fees from Abbott.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with a history of heart failure – no matter the type – face more complications and death than their peers without HF once hospitalized with COVID-19, a new observational study shows.

A history of HF was associated with a near doubling risk of in-hospital mortality and ICU care and more than a tripling risk of mechanical ventilation despite adjustment for 18 factors including race, obesity, diabetes, previous treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, and severity of illness.

Adverse outcomes were high regardless of whether patients had HF with a preserved, mid-range, or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF/HFmrEF/HFrEF).

“That for me was the real zinger,” senior author Anuradha Lala, MD, said in an interview . “Because as clinicians, oftentimes, and wrongly so, we think this person has preserved ejection fraction, so they’re not needing my heart failure expertise as much as someone with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.”

In the peak of the pandemic, that may have meant triaging patients with HFpEF to a regular floor, whereas those with HFrEF were seen by the specialist team.

“What this alerted me to is to take heart failure as a diagnosis very seriously, regardless of ejection fraction, and that is very much in line with all of the emerging data about heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” said Dr. Lala, from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“Now when I see patients in the clinic, I incorporate part of our visit to talking about what they are doing to prevent COVID, which I really wasn’t doing before. It was like ‘Oh yeah, what crazy times we’re dealing with’ and then addressing their heart failure as I normally would,” she said. “But now, interwoven into every visit is: Are you wearing a mask, what’s your social distancing policy, who are you living with at home, has anyone at home or who you’ve interacted with been sick? I’m asking those questions just as a knee-jerk reaction for these patients because I know the repercussions. We have to keep in mind these are observational studies, so I can’t prove causality but these are observations that are, nonetheless, quite robust.”

Although cardiovascular disease, including HF, is recognized as a risk factor for worse outcomes in COVID-19 patients, data are sparse on the clinical course and prognosis of patients with preexisting HF.

“I would have expected that there would have been a gradation of risk from the people with very low ejection fractions up into the normal range, but here it didn’t seem to matter at all. So that’s an important point that bad outcomes were independent of ejection fraction,” commented Lee Goldberg, MD, professor of medicine and chief of advanced heart failure and cardiac transplant at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The study also validated that there is no association between use of RAAS inhibitors and bad outcomes in patients with COVID-19, he said.

Although this has been demonstrated in several studies, concerns were raised early in the pandemic that ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers could facilitate infection with SARS-CoV-2 and increase the risk of severe or lethal COVID-19.

“For most clinicians that question has been put to bed, but we’re still getting patients that will ask during office visits ‘Is it safe for me to stay on?’ They still have that doubt [about] ‘Are we doing the right thing?’ ” Dr. Goldberg said.

“We can reassure them now. A lot of us are able to say there’s nothing to that, we’re very clear about this, stay on the meds. If anything, there’s data that suggest actually it may be better to be on an ACE inhibitor; that the hospitalizations were shorter and the outcomes were a little bit better.”

For the current study, published online Oct. 28 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators analyzed 6,439 patients admitted for COVID-19 at one of five Mount Sinai Health System hospitals in New York between Feb. 27 and June 26. Their mean age was 65.3 years, 45% were women, and one-third were treated with RAAS inhibitors before admission.

Using ICD-9/10 codes and individual chart review, HF was identified in 422 patients (6.6%), of which 250 patients had HFpEF (≥50%), 44 had HFmrEF (41%-49%), and 128 had HFrEF (≤40%).

Patients with HFpEF were older, more frequently women with a higher body mass index and history of lung disease than patients with HFrEF, whereas those with HFmrEF fell in between.

The HFpEF group was also treated with hydroxychloroquine or macrolides and noninvasive ventilation more frequently than the other two groups, whereas antiplatelet and neurohormonal therapies were more common in the HFrEF group.

Patients with a history of HF had significantly longer hospital stays than those without HF (8 days vs. 6 days), increased need for intubation (22.8% vs. 11.9%) and ICU care (23.2% vs. 16.6%), and worse in-hospital mortality (40% vs. 24.9%).

After multivariable regression adjustment, HF persisted as an independent risk factor for ICU care (odds ratio, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.25-2.34), intubation and mechanical ventilation (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 2.56-5.16), and in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.27-2.78).

“I knew to expect higher rates of adverse outcomes but I didn’t expect it to be nearly a twofold increase,” Dr. Lala said. “I thought that was pretty powerful.”

No significant differences were seen across LVEF categories in length of stay, need for ICU care, intubation and mechanical ventilation, acute kidney injury, shock, thromboembolic events, arrhythmias, or 30-day readmission rates.

However, cardiogenic shock (7.8% vs. 2.3% vs. 2%) and HF-related causes for 30-day readmissions (47.1% vs. 0% vs. 8.6%) were significantly higher in patients with HFrEF than in those with HFmrEF or HFpEF.

Also, mortality was lower in those with HFmrEF (22.7%) than with HFrEF (38.3%) and HFpEF (44%). The group was small but the “results suggested that patients with HFmrEF could have a better prognosis, because they can represent a distinct and more favorable HF phenotype,” the authors wrote.

The statistical testing didn’t show much difference and the patient numbers were very small, noted Dr. Goldberg. “So they might be overreaching a little bit there.”

“To me, the take-home message is that just having the phenotype of heart failure, regardless of EF, is associated with bad outcomes and we need to be vigilant on two fronts,” he said. “We really need to be doing prevention in the folks with heart failure because if they get COVID their outcomes are not going to be as good. Second, as clinicians, if we see a patient presenting with COVID who has a history of heart failure we may want to be much more vigilant with that individual than we might otherwise be. So I think there’s something to be said for kind of risk-stratifying people in that way.”

Dr. Goldberg pointed out that the study had many “amazing strengths,” including a large, racially diverse population, direct chart review to identify HF patients, and capturing a patient’s specific HF phenotype.

Weaknesses are that it was a single-center study, so the biases of how these patients were treated are not easily controlled for, he said. “We also don’t know when the hospital system was very strained as they were making some decisions: Were the older patients who had advanced heart and lung disease ultimately less aggressively treated because they felt they wouldn’t survive?”

Dr. Lala has received personal fees from Zoll, outside the submitted work. Dr. Goldberg reported research funding with Respicardia and consulting fees from Abbott.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Biologics may protect psoriasis patients against severe COVID-19

presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Biologics seem to be very protective against severe, poor-prognosis COVID-19, but they do not prevent infection with the virus,” reported Giovanni Damiani, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

This apparent protective effect of biologic agents against severe and even fatal COVID-19 is all the more impressive because the psoriasis patients included in the Italian study – as is true of those elsewhere throughout the world – had relatively high rates of obesity, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19, he added.

He presented a case-control study including 1,193 adult psoriasis patients on biologics or apremilast (Otezla) at Milan’s San Donato Hospital during the period from Feb. 21 to April 9, 2020. The control group comprised more than 10 million individuals, the entire adult population of the Lombardy region, of which Milan is the capital. This was the hardest-hit area in all of Italy during the first wave of COVID-19.

Twenty-two of the 1,193 psoriasis patients experienced confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. Seventeen were quarantined at home because their disease was mild. Five were hospitalized. But no psoriasis patients were placed in intensive care, and none died.

Psoriasis patients on biologics were significantly more likely than the general Lombardian population to test positive for COVID-19, with an unadjusted odds ratio of 3.43. They were at 9.05-fold increased risk of home quarantine for mild disease, and at 3.59-fold greater risk than controls for hospitalization for COVID-19. However, they were not at significantly increased risk of ICU admission. And while they actually had a 59% relative risk reduction for death, this didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Forty-five percent of the psoriasis patients were on an interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitor, 22% were on a tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor, and 20% were taking an IL-12/23 inhibitor. Of note, none of 77 patients on apremilast developed COVID-19, even though it is widely considered a less potent psoriasis therapy than the injectable monoclonal antibody biologics.

The French experience

Anne-Claire Fougerousse, MD, and her French coinvestigators conducted a study designed to address a different question: Is it safe to start psoriasis patients on biologics or older conventional systemic agents such as methotrexate during the pandemic?

She presented a French national cross-sectional study of 1,418 adult psoriasis patients on a biologic or standard systemic therapy during a snapshot in time near the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France: the period from April 27 to May 7, 2020. The group included 1,188 psoriasis patients on maintenance therapy and 230 who had initiated systemic treatment within the past 4 months. More than one-third of the patients had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Although testing wasn’t available to confirm all cases, 54 patients developed probable COVID-19 during the study period. Only five required hospitalization. None died. The two hospitalized psoriasis patients admitted to an ICU had obesity as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as did another of the five hospitalized patients, reported Dr. Fougerousse, a dermatologist at the Bégin Military Teaching Hospital in Saint-Mandé, France. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was required in 0.43% of the French treatment initiators, not significantly different from the 0.34% rate in patients on maintenance systemic therapy. A study limitation was the lack of a control group.

Nonetheless, the data did answer the investigators’ main question: “This is the first data showing no increased incidence of severe COVID-19 in psoriasis patients receiving systemic therapy in the treatment initiation period compared to those on maintenance therapy. This may now allow physicians to initiate conventional systemic or biologic therapy in patients with severe psoriasis on a case-by-case basis in the context of the persistent COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Fougerousse concluded.

Proposed mechanism of benefit

The Italian study findings that biologics boost the risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in psoriasis patients while potentially protecting them against ICU admission and death are backed by a biologically plausible albeit as yet unproven mechanism of action, Dr. Damiani asserted.

He elaborated: A vast body of high-quality clinical trials data demonstrates that these targeted immunosuppressive agents are associated with modestly increased risk of viral infections, including both skin and respiratory tract infections. So there is no reason to suppose these agents would offer protection against the first phase of COVID-19, involving SARS-CoV-2 infection, nor protect against the second (pulmonary phase), whose hallmarks are dyspnea with or without hypoxia. But progression to the third phase, involving hyperinflammation and hypercoagulation – dubbed the cytokine storm – could be a different matter.

“Of particular interest was that our patients on IL-17 inhibitors displayed a really great outcome. Interleukin-17 has procoagulant and prothrombotic effects, organizes bronchoalveolar remodeling, has a profibrotic effect, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and encourages dendritic cell migration in peribronchial lymph nodes. Therefore, by antagonizing this interleukin, we may have a better prognosis, although further studies are needed to be certain,” Dr. Damiani commented.

Publication of his preliminary findings drew the attention of a group of highly respected thought leaders in psoriasis, including James G. Krueger, MD, head of the laboratory for investigative dermatology and codirector of the center for clinical and investigative science at Rockefeller University, New York.

The Italian report prompted them to analyze data from the phase 4, double-blind, randomized ObePso-S study investigating the effects of the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) on systemic inflammatory markers and gene expression in psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that IL-17–mediated inflammation in psoriasis patients was associated with increased expression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in lesional skin, and that treatment with secukinumab dropped ACE2 expression to levels seen in nonlesional skin. Given that ACE2 is the chief portal of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and that IL-17 exerts systemic proinflammatory effects, it’s plausible that inhibition of IL-17–mediated inflammation via dampening of ACE2 expression in noncutaneous epithelia “could prove to be advantageous in patients with psoriasis who are at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection,” according to Dr. Krueger and his coinvestigators in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Damiani and Dr. Fougerousse reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies. The secukinumab/ACE2 receptor study was funded by Novartis.

presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Biologics seem to be very protective against severe, poor-prognosis COVID-19, but they do not prevent infection with the virus,” reported Giovanni Damiani, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

This apparent protective effect of biologic agents against severe and even fatal COVID-19 is all the more impressive because the psoriasis patients included in the Italian study – as is true of those elsewhere throughout the world – had relatively high rates of obesity, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19, he added.

He presented a case-control study including 1,193 adult psoriasis patients on biologics or apremilast (Otezla) at Milan’s San Donato Hospital during the period from Feb. 21 to April 9, 2020. The control group comprised more than 10 million individuals, the entire adult population of the Lombardy region, of which Milan is the capital. This was the hardest-hit area in all of Italy during the first wave of COVID-19.

Twenty-two of the 1,193 psoriasis patients experienced confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. Seventeen were quarantined at home because their disease was mild. Five were hospitalized. But no psoriasis patients were placed in intensive care, and none died.

Psoriasis patients on biologics were significantly more likely than the general Lombardian population to test positive for COVID-19, with an unadjusted odds ratio of 3.43. They were at 9.05-fold increased risk of home quarantine for mild disease, and at 3.59-fold greater risk than controls for hospitalization for COVID-19. However, they were not at significantly increased risk of ICU admission. And while they actually had a 59% relative risk reduction for death, this didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Forty-five percent of the psoriasis patients were on an interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitor, 22% were on a tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor, and 20% were taking an IL-12/23 inhibitor. Of note, none of 77 patients on apremilast developed COVID-19, even though it is widely considered a less potent psoriasis therapy than the injectable monoclonal antibody biologics.

The French experience

Anne-Claire Fougerousse, MD, and her French coinvestigators conducted a study designed to address a different question: Is it safe to start psoriasis patients on biologics or older conventional systemic agents such as methotrexate during the pandemic?

She presented a French national cross-sectional study of 1,418 adult psoriasis patients on a biologic or standard systemic therapy during a snapshot in time near the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France: the period from April 27 to May 7, 2020. The group included 1,188 psoriasis patients on maintenance therapy and 230 who had initiated systemic treatment within the past 4 months. More than one-third of the patients had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Although testing wasn’t available to confirm all cases, 54 patients developed probable COVID-19 during the study period. Only five required hospitalization. None died. The two hospitalized psoriasis patients admitted to an ICU had obesity as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as did another of the five hospitalized patients, reported Dr. Fougerousse, a dermatologist at the Bégin Military Teaching Hospital in Saint-Mandé, France. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was required in 0.43% of the French treatment initiators, not significantly different from the 0.34% rate in patients on maintenance systemic therapy. A study limitation was the lack of a control group.

Nonetheless, the data did answer the investigators’ main question: “This is the first data showing no increased incidence of severe COVID-19 in psoriasis patients receiving systemic therapy in the treatment initiation period compared to those on maintenance therapy. This may now allow physicians to initiate conventional systemic or biologic therapy in patients with severe psoriasis on a case-by-case basis in the context of the persistent COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Fougerousse concluded.

Proposed mechanism of benefit

The Italian study findings that biologics boost the risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in psoriasis patients while potentially protecting them against ICU admission and death are backed by a biologically plausible albeit as yet unproven mechanism of action, Dr. Damiani asserted.

He elaborated: A vast body of high-quality clinical trials data demonstrates that these targeted immunosuppressive agents are associated with modestly increased risk of viral infections, including both skin and respiratory tract infections. So there is no reason to suppose these agents would offer protection against the first phase of COVID-19, involving SARS-CoV-2 infection, nor protect against the second (pulmonary phase), whose hallmarks are dyspnea with or without hypoxia. But progression to the third phase, involving hyperinflammation and hypercoagulation – dubbed the cytokine storm – could be a different matter.

“Of particular interest was that our patients on IL-17 inhibitors displayed a really great outcome. Interleukin-17 has procoagulant and prothrombotic effects, organizes bronchoalveolar remodeling, has a profibrotic effect, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and encourages dendritic cell migration in peribronchial lymph nodes. Therefore, by antagonizing this interleukin, we may have a better prognosis, although further studies are needed to be certain,” Dr. Damiani commented.

Publication of his preliminary findings drew the attention of a group of highly respected thought leaders in psoriasis, including James G. Krueger, MD, head of the laboratory for investigative dermatology and codirector of the center for clinical and investigative science at Rockefeller University, New York.

The Italian report prompted them to analyze data from the phase 4, double-blind, randomized ObePso-S study investigating the effects of the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) on systemic inflammatory markers and gene expression in psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that IL-17–mediated inflammation in psoriasis patients was associated with increased expression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in lesional skin, and that treatment with secukinumab dropped ACE2 expression to levels seen in nonlesional skin. Given that ACE2 is the chief portal of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and that IL-17 exerts systemic proinflammatory effects, it’s plausible that inhibition of IL-17–mediated inflammation via dampening of ACE2 expression in noncutaneous epithelia “could prove to be advantageous in patients with psoriasis who are at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection,” according to Dr. Krueger and his coinvestigators in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Damiani and Dr. Fougerousse reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies. The secukinumab/ACE2 receptor study was funded by Novartis.

presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Biologics seem to be very protective against severe, poor-prognosis COVID-19, but they do not prevent infection with the virus,” reported Giovanni Damiani, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

This apparent protective effect of biologic agents against severe and even fatal COVID-19 is all the more impressive because the psoriasis patients included in the Italian study – as is true of those elsewhere throughout the world – had relatively high rates of obesity, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19, he added.

He presented a case-control study including 1,193 adult psoriasis patients on biologics or apremilast (Otezla) at Milan’s San Donato Hospital during the period from Feb. 21 to April 9, 2020. The control group comprised more than 10 million individuals, the entire adult population of the Lombardy region, of which Milan is the capital. This was the hardest-hit area in all of Italy during the first wave of COVID-19.

Twenty-two of the 1,193 psoriasis patients experienced confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. Seventeen were quarantined at home because their disease was mild. Five were hospitalized. But no psoriasis patients were placed in intensive care, and none died.

Psoriasis patients on biologics were significantly more likely than the general Lombardian population to test positive for COVID-19, with an unadjusted odds ratio of 3.43. They were at 9.05-fold increased risk of home quarantine for mild disease, and at 3.59-fold greater risk than controls for hospitalization for COVID-19. However, they were not at significantly increased risk of ICU admission. And while they actually had a 59% relative risk reduction for death, this didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Forty-five percent of the psoriasis patients were on an interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitor, 22% were on a tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor, and 20% were taking an IL-12/23 inhibitor. Of note, none of 77 patients on apremilast developed COVID-19, even though it is widely considered a less potent psoriasis therapy than the injectable monoclonal antibody biologics.

The French experience

Anne-Claire Fougerousse, MD, and her French coinvestigators conducted a study designed to address a different question: Is it safe to start psoriasis patients on biologics or older conventional systemic agents such as methotrexate during the pandemic?

She presented a French national cross-sectional study of 1,418 adult psoriasis patients on a biologic or standard systemic therapy during a snapshot in time near the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France: the period from April 27 to May 7, 2020. The group included 1,188 psoriasis patients on maintenance therapy and 230 who had initiated systemic treatment within the past 4 months. More than one-third of the patients had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Although testing wasn’t available to confirm all cases, 54 patients developed probable COVID-19 during the study period. Only five required hospitalization. None died. The two hospitalized psoriasis patients admitted to an ICU had obesity as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as did another of the five hospitalized patients, reported Dr. Fougerousse, a dermatologist at the Bégin Military Teaching Hospital in Saint-Mandé, France. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was required in 0.43% of the French treatment initiators, not significantly different from the 0.34% rate in patients on maintenance systemic therapy. A study limitation was the lack of a control group.

Nonetheless, the data did answer the investigators’ main question: “This is the first data showing no increased incidence of severe COVID-19 in psoriasis patients receiving systemic therapy in the treatment initiation period compared to those on maintenance therapy. This may now allow physicians to initiate conventional systemic or biologic therapy in patients with severe psoriasis on a case-by-case basis in the context of the persistent COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Fougerousse concluded.

Proposed mechanism of benefit

The Italian study findings that biologics boost the risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in psoriasis patients while potentially protecting them against ICU admission and death are backed by a biologically plausible albeit as yet unproven mechanism of action, Dr. Damiani asserted.

He elaborated: A vast body of high-quality clinical trials data demonstrates that these targeted immunosuppressive agents are associated with modestly increased risk of viral infections, including both skin and respiratory tract infections. So there is no reason to suppose these agents would offer protection against the first phase of COVID-19, involving SARS-CoV-2 infection, nor protect against the second (pulmonary phase), whose hallmarks are dyspnea with or without hypoxia. But progression to the third phase, involving hyperinflammation and hypercoagulation – dubbed the cytokine storm – could be a different matter.

“Of particular interest was that our patients on IL-17 inhibitors displayed a really great outcome. Interleukin-17 has procoagulant and prothrombotic effects, organizes bronchoalveolar remodeling, has a profibrotic effect, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and encourages dendritic cell migration in peribronchial lymph nodes. Therefore, by antagonizing this interleukin, we may have a better prognosis, although further studies are needed to be certain,” Dr. Damiani commented.

Publication of his preliminary findings drew the attention of a group of highly respected thought leaders in psoriasis, including James G. Krueger, MD, head of the laboratory for investigative dermatology and codirector of the center for clinical and investigative science at Rockefeller University, New York.

The Italian report prompted them to analyze data from the phase 4, double-blind, randomized ObePso-S study investigating the effects of the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) on systemic inflammatory markers and gene expression in psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that IL-17–mediated inflammation in psoriasis patients was associated with increased expression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in lesional skin, and that treatment with secukinumab dropped ACE2 expression to levels seen in nonlesional skin. Given that ACE2 is the chief portal of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and that IL-17 exerts systemic proinflammatory effects, it’s plausible that inhibition of IL-17–mediated inflammation via dampening of ACE2 expression in noncutaneous epithelia “could prove to be advantageous in patients with psoriasis who are at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection,” according to Dr. Krueger and his coinvestigators in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Damiani and Dr. Fougerousse reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies. The secukinumab/ACE2 receptor study was funded by Novartis.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Updated heart failure measures add newer meds

Safety measures for lab monitoring of mineralocorticoid receptor agonist therapy, performance measures for sacubitril/valsartan, cardiac resynchronization therapy and titration of medications, and quality measures based on patient-reported outcomes are among the updates the joint task force of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have made to performance and quality measures for managing adults with heart failure.

The revisions, published online Nov. 2 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, update the 2011 ACC/AHA heart failure measure set, writing committee vice chair Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said in an interview. The 2011 measure set predates the 2015 approval of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan for heart failure in adults.

Measures stress dosages, strength of evidence

“For the first time the heart failure performance measure sets also focus on not just the use of guideline-recommended medication at any dose, but on utilizing the doses that are evidence-based and guideline recommended so long as they are well tolerated,” said Dr. Fonarow, interim chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The measure set now includes assessment of patients being treated with doses of medications at 50% or greater of target dose in the absence of contraindications or documented intolerance.”

The update includes seven new performance measures, two quality measures, and one structural measure. The performance measures come from the strongest recommendations – that is, a class of recommendation of 1 (strong) or 3 (no benefit or harmful, process to be avoided) – in the 2017 ACC/AHA/Heart Failure Society of American heart failure guideline update published in Circulation.

In addition to the 2017 update, the writing committee also reviewed existing performance measures. “Those management strategies, diagnostic testing, medications, and devices with the strongest evidence and highest level of guideline recommendations were further considered for inclusion in the performance measure set,” Dr. Fonarow said. “The measures went through extensive review by peer reviewers and approval from the organizations represented.”

Specifically, the update includes measures for monitoring serum potassium after starting mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists therapy, and cardiac resynchronization therapy for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction already on guideline-directed therapy. “This therapy can significantly improve functional capacity and outcomes in appropriately selected patients,” Dr. Fonarow said.

New and retired measures

The update adds two performance measures for titration of medications based on dose, either reaching 50% of the recommended dose for a variety of medications, including ARNI, or documenting that the dose wasn’t tolerated for other reason for not using the dose.

The new structural measure calls for facility participation in a heart failure registry. The revised measure set now consists of 18 measures in all.

The update retired one measure from the 2011 set: left ventricular ejection fraction assessment for inpatients. The committee cited its use above 97% as the reason, but LVEF in outpatients remains a measure.

The following tree measures have been revised:

- Patient self-care education has moved from performance measure to quality measure because of concerns about the accuracy of self-care education documentation and limited evidence of improved outcomes with better documentation.

- ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for left ventricular systolic dysfunction adds ARNI therapy to align with the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA update.

- Postdischarge appointments shifts from performance to quality measure and include a 7-day limit.

Measures future research should focus on, noted Dr. Fonarow, include the use of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for heart failure, including in patients without diabetes. “Since the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines had not yet been updated to recommend these therapies they could not be included in this performance measure set,” he said.

He also said “an urgent need” exists for further research into treatments for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction along with optimal implementation strategies.

“If these ACC/AHA heart failure performance measures were applied in all settings in which patients with heart failure in the United States are being cared for, and optimal and equitable conformity with each of these measures were achieved, over 100,000 lives a year of patients with heart failure could be saved,” he said. “There’s in an urgent need to measure and improve heart failure care quality.”

Dr. Fonarow reported financial relationships with Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CHF Solutions, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

SOURCE: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 2;76:2527-64.

Safety measures for lab monitoring of mineralocorticoid receptor agonist therapy, performance measures for sacubitril/valsartan, cardiac resynchronization therapy and titration of medications, and quality measures based on patient-reported outcomes are among the updates the joint task force of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have made to performance and quality measures for managing adults with heart failure.

The revisions, published online Nov. 2 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, update the 2011 ACC/AHA heart failure measure set, writing committee vice chair Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said in an interview. The 2011 measure set predates the 2015 approval of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan for heart failure in adults.

Measures stress dosages, strength of evidence

“For the first time the heart failure performance measure sets also focus on not just the use of guideline-recommended medication at any dose, but on utilizing the doses that are evidence-based and guideline recommended so long as they are well tolerated,” said Dr. Fonarow, interim chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The measure set now includes assessment of patients being treated with doses of medications at 50% or greater of target dose in the absence of contraindications or documented intolerance.”

The update includes seven new performance measures, two quality measures, and one structural measure. The performance measures come from the strongest recommendations – that is, a class of recommendation of 1 (strong) or 3 (no benefit or harmful, process to be avoided) – in the 2017 ACC/AHA/Heart Failure Society of American heart failure guideline update published in Circulation.

In addition to the 2017 update, the writing committee also reviewed existing performance measures. “Those management strategies, diagnostic testing, medications, and devices with the strongest evidence and highest level of guideline recommendations were further considered for inclusion in the performance measure set,” Dr. Fonarow said. “The measures went through extensive review by peer reviewers and approval from the organizations represented.”

Specifically, the update includes measures for monitoring serum potassium after starting mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists therapy, and cardiac resynchronization therapy for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction already on guideline-directed therapy. “This therapy can significantly improve functional capacity and outcomes in appropriately selected patients,” Dr. Fonarow said.

New and retired measures

The update adds two performance measures for titration of medications based on dose, either reaching 50% of the recommended dose for a variety of medications, including ARNI, or documenting that the dose wasn’t tolerated for other reason for not using the dose.

The new structural measure calls for facility participation in a heart failure registry. The revised measure set now consists of 18 measures in all.

The update retired one measure from the 2011 set: left ventricular ejection fraction assessment for inpatients. The committee cited its use above 97% as the reason, but LVEF in outpatients remains a measure.

The following tree measures have been revised:

- Patient self-care education has moved from performance measure to quality measure because of concerns about the accuracy of self-care education documentation and limited evidence of improved outcomes with better documentation.

- ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for left ventricular systolic dysfunction adds ARNI therapy to align with the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA update.

- Postdischarge appointments shifts from performance to quality measure and include a 7-day limit.

Measures future research should focus on, noted Dr. Fonarow, include the use of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for heart failure, including in patients without diabetes. “Since the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines had not yet been updated to recommend these therapies they could not be included in this performance measure set,” he said.

He also said “an urgent need” exists for further research into treatments for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction along with optimal implementation strategies.

“If these ACC/AHA heart failure performance measures were applied in all settings in which patients with heart failure in the United States are being cared for, and optimal and equitable conformity with each of these measures were achieved, over 100,000 lives a year of patients with heart failure could be saved,” he said. “There’s in an urgent need to measure and improve heart failure care quality.”

Dr. Fonarow reported financial relationships with Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CHF Solutions, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

SOURCE: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 2;76:2527-64.

Safety measures for lab monitoring of mineralocorticoid receptor agonist therapy, performance measures for sacubitril/valsartan, cardiac resynchronization therapy and titration of medications, and quality measures based on patient-reported outcomes are among the updates the joint task force of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have made to performance and quality measures for managing adults with heart failure.

The revisions, published online Nov. 2 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, update the 2011 ACC/AHA heart failure measure set, writing committee vice chair Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said in an interview. The 2011 measure set predates the 2015 approval of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan for heart failure in adults.

Measures stress dosages, strength of evidence

“For the first time the heart failure performance measure sets also focus on not just the use of guideline-recommended medication at any dose, but on utilizing the doses that are evidence-based and guideline recommended so long as they are well tolerated,” said Dr. Fonarow, interim chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The measure set now includes assessment of patients being treated with doses of medications at 50% or greater of target dose in the absence of contraindications or documented intolerance.”

The update includes seven new performance measures, two quality measures, and one structural measure. The performance measures come from the strongest recommendations – that is, a class of recommendation of 1 (strong) or 3 (no benefit or harmful, process to be avoided) – in the 2017 ACC/AHA/Heart Failure Society of American heart failure guideline update published in Circulation.

In addition to the 2017 update, the writing committee also reviewed existing performance measures. “Those management strategies, diagnostic testing, medications, and devices with the strongest evidence and highest level of guideline recommendations were further considered for inclusion in the performance measure set,” Dr. Fonarow said. “The measures went through extensive review by peer reviewers and approval from the organizations represented.”

Specifically, the update includes measures for monitoring serum potassium after starting mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists therapy, and cardiac resynchronization therapy for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction already on guideline-directed therapy. “This therapy can significantly improve functional capacity and outcomes in appropriately selected patients,” Dr. Fonarow said.

New and retired measures

The update adds two performance measures for titration of medications based on dose, either reaching 50% of the recommended dose for a variety of medications, including ARNI, or documenting that the dose wasn’t tolerated for other reason for not using the dose.

The new structural measure calls for facility participation in a heart failure registry. The revised measure set now consists of 18 measures in all.

The update retired one measure from the 2011 set: left ventricular ejection fraction assessment for inpatients. The committee cited its use above 97% as the reason, but LVEF in outpatients remains a measure.

The following tree measures have been revised:

- Patient self-care education has moved from performance measure to quality measure because of concerns about the accuracy of self-care education documentation and limited evidence of improved outcomes with better documentation.

- ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for left ventricular systolic dysfunction adds ARNI therapy to align with the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA update.

- Postdischarge appointments shifts from performance to quality measure and include a 7-day limit.

Measures future research should focus on, noted Dr. Fonarow, include the use of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for heart failure, including in patients without diabetes. “Since the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines had not yet been updated to recommend these therapies they could not be included in this performance measure set,” he said.

He also said “an urgent need” exists for further research into treatments for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction along with optimal implementation strategies.

“If these ACC/AHA heart failure performance measures were applied in all settings in which patients with heart failure in the United States are being cared for, and optimal and equitable conformity with each of these measures were achieved, over 100,000 lives a year of patients with heart failure could be saved,” he said. “There’s in an urgent need to measure and improve heart failure care quality.”

Dr. Fonarow reported financial relationships with Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CHF Solutions, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

SOURCE: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 2;76:2527-64.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Health sector has spent $464 million on lobbying in 2020

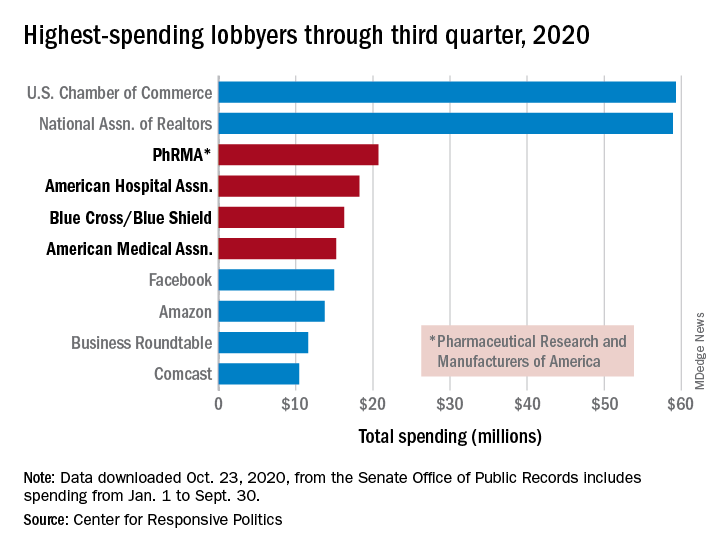

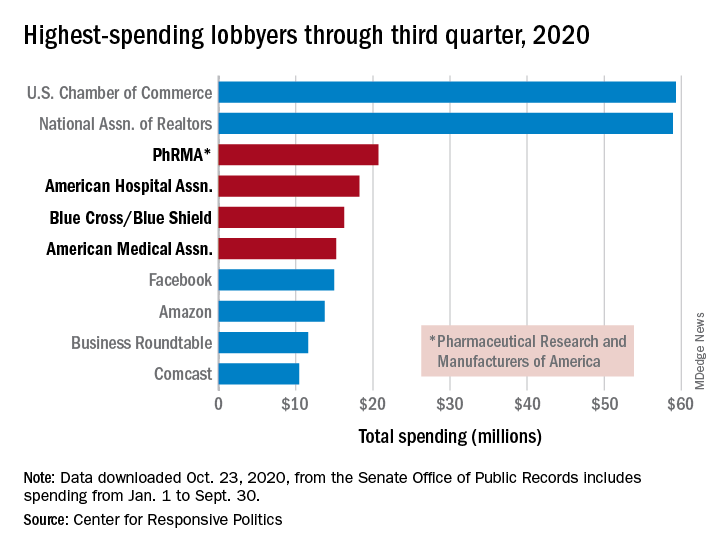

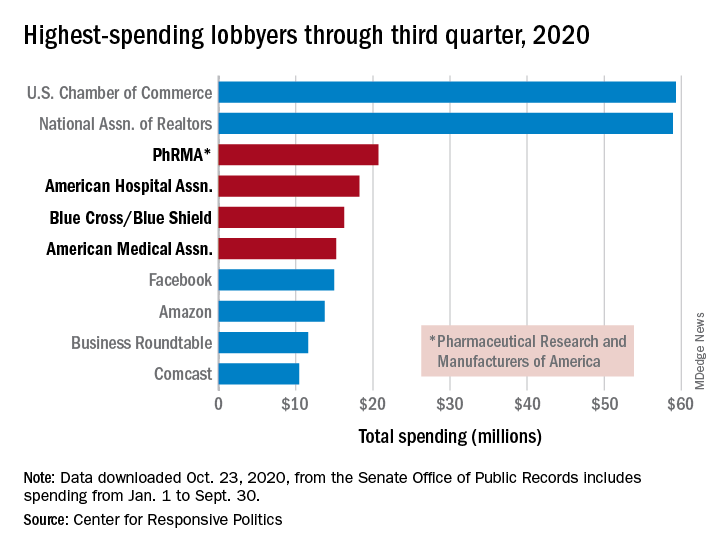

, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

PhRMA spent $20.7 million on lobbying through the end of September, good enough for third on the overall list of U.S. companies and organizations. Three other members of the health sector made the top 10: the American Hospital Association ($18.3 million), BlueCross/BlueShield ($16.3 million), and the American Medical Association ($15.2 million), the center reported.

Total spending by the health sector was $464 million from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, topping the finance/insurance/real estate sector at $403 million, and miscellaneous business at $371 million. Miscellaneous business is the home of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the annual leader in such spending for the last 20 years, based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records.

The largest share of health sector spending came from pharmaceuticals/health products, with a total of almost $233 million, just slightly more than the sector’s four other constituents combined: hospitals/nursing homes ($80 million), health services/HMOs ($75 million), health professionals ($67 million), and miscellaneous health ($9.5 million), the center said on OpenSecrets.org.

Taking one step down from the sector level, that $233 million made pharmaceuticals/health products the highest spending of about 100 industries in 2020, nearly doubling the efforts of electronics manufacturing and equipment ($118 million), which came a distant second. Hospitals/nursing homes was eighth on the industry list, the center noted.

, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

PhRMA spent $20.7 million on lobbying through the end of September, good enough for third on the overall list of U.S. companies and organizations. Three other members of the health sector made the top 10: the American Hospital Association ($18.3 million), BlueCross/BlueShield ($16.3 million), and the American Medical Association ($15.2 million), the center reported.

Total spending by the health sector was $464 million from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, topping the finance/insurance/real estate sector at $403 million, and miscellaneous business at $371 million. Miscellaneous business is the home of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the annual leader in such spending for the last 20 years, based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records.

The largest share of health sector spending came from pharmaceuticals/health products, with a total of almost $233 million, just slightly more than the sector’s four other constituents combined: hospitals/nursing homes ($80 million), health services/HMOs ($75 million), health professionals ($67 million), and miscellaneous health ($9.5 million), the center said on OpenSecrets.org.

Taking one step down from the sector level, that $233 million made pharmaceuticals/health products the highest spending of about 100 industries in 2020, nearly doubling the efforts of electronics manufacturing and equipment ($118 million), which came a distant second. Hospitals/nursing homes was eighth on the industry list, the center noted.

, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

PhRMA spent $20.7 million on lobbying through the end of September, good enough for third on the overall list of U.S. companies and organizations. Three other members of the health sector made the top 10: the American Hospital Association ($18.3 million), BlueCross/BlueShield ($16.3 million), and the American Medical Association ($15.2 million), the center reported.

Total spending by the health sector was $464 million from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, topping the finance/insurance/real estate sector at $403 million, and miscellaneous business at $371 million. Miscellaneous business is the home of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the annual leader in such spending for the last 20 years, based on data from the Senate Office of Public Records.

The largest share of health sector spending came from pharmaceuticals/health products, with a total of almost $233 million, just slightly more than the sector’s four other constituents combined: hospitals/nursing homes ($80 million), health services/HMOs ($75 million), health professionals ($67 million), and miscellaneous health ($9.5 million), the center said on OpenSecrets.org.

Taking one step down from the sector level, that $233 million made pharmaceuticals/health products the highest spending of about 100 industries in 2020, nearly doubling the efforts of electronics manufacturing and equipment ($118 million), which came a distant second. Hospitals/nursing homes was eighth on the industry list, the center noted.

Physician burnout costly to organizations and U.S. health system

Background: Occupational burnout is more prevalent among physicians than among the general population, and physician burnout is associated with several negative clinical outcomes. However, little is known about the economic cost of this widespread issue.

Study design: Cost-consequence analysis using a novel mathematical model.

Setting: Simulated population of U.S. physicians.

Synopsis: Researchers conducted a cost-consequence analysis using a mathematical model designed to determine the financial impact of burnout – or the difference in observed cost and the theoretical cost if physicians did not experience burnout. The model used a hypothetical physician population based on a 2013 profile of U.S. physicians, a 2014 survey of physicians that assessed burnout, and preexisting literature on burnout to generate the input data for their model. The investigators focused on two outcomes: turnover and reduction in clinical hours. They found that approximately $4.6 billion per year is lost in direct cost secondary to physician burnout, with the greatest proportion coming from physician turnover. The figure ranged from $2.6 billion to $6.3 billion in multivariate sensitivity analysis. For an organization, the cost of burnout is about $7,600 per physician per year, with a range of $4,100 to $10,200. Though statistical modeling can be imprecise, and the input data were imperfect, the study was the first to examine the systemwide cost of physician burnout in the United States.

Bottom line: Along with the negative effects on physician and patient well-being, physician burnout is financially costly to the U.S. health care system and to individual organizations. Programs to reduce burnout could be both ethically and economically advantageous.

Citation: Han S et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-90.

Dr. Suojanen is a hospitalist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Background: Occupational burnout is more prevalent among physicians than among the general population, and physician burnout is associated with several negative clinical outcomes. However, little is known about the economic cost of this widespread issue.

Study design: Cost-consequence analysis using a novel mathematical model.

Setting: Simulated population of U.S. physicians.

Synopsis: Researchers conducted a cost-consequence analysis using a mathematical model designed to determine the financial impact of burnout – or the difference in observed cost and the theoretical cost if physicians did not experience burnout. The model used a hypothetical physician population based on a 2013 profile of U.S. physicians, a 2014 survey of physicians that assessed burnout, and preexisting literature on burnout to generate the input data for their model. The investigators focused on two outcomes: turnover and reduction in clinical hours. They found that approximately $4.6 billion per year is lost in direct cost secondary to physician burnout, with the greatest proportion coming from physician turnover. The figure ranged from $2.6 billion to $6.3 billion in multivariate sensitivity analysis. For an organization, the cost of burnout is about $7,600 per physician per year, with a range of $4,100 to $10,200. Though statistical modeling can be imprecise, and the input data were imperfect, the study was the first to examine the systemwide cost of physician burnout in the United States.

Bottom line: Along with the negative effects on physician and patient well-being, physician burnout is financially costly to the U.S. health care system and to individual organizations. Programs to reduce burnout could be both ethically and economically advantageous.

Citation: Han S et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-90.

Dr. Suojanen is a hospitalist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Background: Occupational burnout is more prevalent among physicians than among the general population, and physician burnout is associated with several negative clinical outcomes. However, little is known about the economic cost of this widespread issue.

Study design: Cost-consequence analysis using a novel mathematical model.

Setting: Simulated population of U.S. physicians.

Synopsis: Researchers conducted a cost-consequence analysis using a mathematical model designed to determine the financial impact of burnout – or the difference in observed cost and the theoretical cost if physicians did not experience burnout. The model used a hypothetical physician population based on a 2013 profile of U.S. physicians, a 2014 survey of physicians that assessed burnout, and preexisting literature on burnout to generate the input data for their model. The investigators focused on two outcomes: turnover and reduction in clinical hours. They found that approximately $4.6 billion per year is lost in direct cost secondary to physician burnout, with the greatest proportion coming from physician turnover. The figure ranged from $2.6 billion to $6.3 billion in multivariate sensitivity analysis. For an organization, the cost of burnout is about $7,600 per physician per year, with a range of $4,100 to $10,200. Though statistical modeling can be imprecise, and the input data were imperfect, the study was the first to examine the systemwide cost of physician burnout in the United States.

Bottom line: Along with the negative effects on physician and patient well-being, physician burnout is financially costly to the U.S. health care system and to individual organizations. Programs to reduce burnout could be both ethically and economically advantageous.

Citation: Han S et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-90.

Dr. Suojanen is a hospitalist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Med student’s cardiac crisis a COVID-era medical mystery

Within minutes of her arrival at Community North Hospital in Indianapolis, Ramya Yeleti’s vital signs plummeted; her pulse was at 45 beats per minute and her ejection fraction was hovering near 10%. “I definitely thought there was a chance I would close my eyes and never open them again, but I only had a few seconds to process that,” she recalled. Then everything went black. Ramya fell unconscious as shock pads were positioned and a swarm of clinicians prepared to insert an Impella heart pump through a catheter into her aorta.

The third-year medical student and aspiring psychiatrist had been doing in-person neurology rotations in July when she began to experience fever and uncontrolled vomiting. Her initial thought was that she must have caught the flu from a patient.

After all, Ramya, along with her father Ram Yeleti, MD, mother Indira, and twin sister Divya, had all weathered COVID-19 in previous months and later tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The only family member who had been spared was her younger brother Rohith.

Indira suffered a severe case, requiring ICU care for 2 days but no ventilator; the others experienced mostly mild symptoms. Ramya — who was studying for her third-year board exams after classes at Marian University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Indianapolis went virtual in March — was left with lingering fatigue; however, her cough and muscle aches abated and her sense of taste and smell returned. When she started rotations, she thought her life was getting back to normal.

Ramya’s flu symptoms did not improve. A university-mandated rapid COVID test came back negative, but 2 more days of vomiting started to worry both her and her father, who is a cardiologist and chief physician executive at Community Health Network in Indianapolis. After Ramya felt some chest pain, she asked her father to listen to her heart. All sounded normal, and Ram prescribed ondansetron for her nausea.

But the antiemetic didn’t work, and by the next morning both father and daughter were convinced that they needed to head to the emergency department.

“I wanted to double-check if I was missing something about her being dehydrated,” Ram told Medscape Medical News. “Several things can cause protracted nausea, like hepatitis, appendicitis, or another infection. I feel terribly guilty I didn’t realize she had a heart condition.”

A surprising turn for the worst

Ramya’s subtle symptoms quickly gave way to the dramatic cardiac crisis that unfolded just after her arrival at Community North. “Her EKG looked absolutely horrendous, like a 75-year-old having a heart attack,” Ram said.

As a cardiologist, he knew his daughter’s situation was growing dire when he heard physicians shouting that the Impella wasn’t working and she needed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

“At that point, I didn’t think she’d survive,” her father recalled. “We had 10 physicians in the room who worked on her for 5 hours to get her stabilized.”

“It was especially traumatic because, obviously, I knew exactly what was happening,” he added. “You can’t sugarcoat anything.”

After being connected to the heart–lung equipment, Ramya was transferred to IU Health Methodist Hospital, also in Indianapolis, where she was tested again for COVID-19. Unlike the rapid test administered just days earlier, the PCR assay came back positive.

“I knew she had acute myocarditis, but coronavirus never crossed my mind,” said Ram.

“As we were dealing with her heart, we were also dealing with this challenge: she was coming back positive for COVID-19 again,” said Roopa Rao, MD, the heart failure transplant cardiologist at IU Health who treated Ramya.

“We weren’t sure whether we were dealing with an active infection or dead virus” from her previous infection, Rao said, “so we started treating her like she had active COVID-19 and gave her remdesivir, convalescent plasma, and steroids, which was the protocol in our hospital.”

A biopsy of Ramya’s heart tissue, along with blood tests, indicated a past parvovirus infection. It’s possible that Ramya’s previous coronavirus infection made her susceptible to heart damage from a newer parvovirus infection, said Rao. Either virus, or both together, could have been responsible for the calamity.

Although it was unheard of during Ramya’s cardiac crisis in early August, evolving evidence now raises the possibility that she is one of a handful of people in the world to be reinfected with SARS-CoV-2. Also emerging are cases of COVID-related myocarditis and other extreme heart complications, particularly in young people.

“At the time, it wasn’t really clear if people could have another infection so quickly,” Rao told Medscape Medical News. “It is possible she is one of these rare individuals to have COVID-19 twice. I’m hoping at some point we will have some clarity.”

“I would favor a coinfection as probably the triggering factor for her sickness,” she said. “It may take some time, but like any other disease — and it doesn’t look like COVID will go away magically — I hope we’ll have some answers down the road.”

Another wrinkle

The next 48 hours brought astonishing news: Ramya’s heart function had rebounded to nearly normal, and her ejection fraction increased to about 45%. Heart transplantation wouldn’t be necessary, although Rao stood poised to follow through if ECMO only sustained, rather than improved, Ramya’s prognosis.

“Ramya was so sick that if she didn’t recover, the only option would be a heart transplant,” said Rao. “But we wanted to do everything to keep that heart.”

After steroid and COVID treatment, Ramya’s heart started to come back. “It didn’t make sense to me,” said Rao. “I don’t know what helped. If we hadn’t done ECMO, her heart probably wouldn’t have recovered, so I would say we have to support these patients and give them time for the heart to recover, even to the point of ECMO.”

Despite the good news, Ramya’s survival still hung in the balance. When she was disconnected from ECMO, clinicians discovered that the Impella device had caused a rare complication, damaging her mitral valve. The valve could be repaired surgically, but both Rao and Ram felt great trepidation at the prospect of cardiopulmonary bypass during the open-heart procedure.

“They would need to stop her heart and restart it, and I was concerned it would not restart,” Ram explained. “I didn’t like the idea of open-heart surgery, but my biggest fear was she was not going to survive it because of a really fresh, sick heart.”

The cardiologists’ fears did, in fact, come to pass: it took an hour to coax Ramya’s heart back at the end of surgery. But, just as the surgeon was preparing to reconnect Ramya to ECMO in desperation, “her heart recovered again,” Rao reported.

“Some things you never forget in life,” she said. “I can’t describe how everyone in the OR felt, all taking care of her. I told Ramya, ‘you are a fighter’.”

New strength

Six days would pass before Ramya woke up and learned of the astounding series of events that saved her. She knew “something was really wrong” because of the incision at the center of her chest, but learning she’d been on ECMO and the heart transplant list drove home how close to death she’d actually come.

“Most people don’t get off ECMO; they die on it,” she said. “And the chances of dying on the heart transplant list are very high. It was very strange to me that this was my story all of a sudden, when a week and a half earlier I was on rotation.”

Ongoing physical therapy over the past 3 months has transformed Ramya from a state of profound physical weakness to a place of relative strength. The now-fourth-year med student is turning 26 in November and is hungry to restart in-person rotations. Her downtime has been filled in part with researching myocarditis and collaborating with Rao on her own case study for journal publication.

But the mental trauma from her experience has girded her in ways she knows will make her stronger personally and professionally in the years ahead.

“It’s still very hard. I’m still recovering,” she acknowledged. “I described it to my therapist as an invisible wound on my brain.”