User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Diversity – We’re not one size fits all

The United States has often been described as a “melting pot,” defined as diverse cultures and ethnicities coming together to form the rich fabric of our nation. These days, it seems that our fabric is a bit frayed.

DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) is dawning as a significant conversation. Each and every one of us is unique by age, gender, culture/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, geographical location, race, and sexual identity – to name just a few aspects of our identity. Keeping these differences in mind, it is evident that none of us fits a “one size fits all” mold.

Some of these differences, such as cross-cultural cuisine and holidays, are enjoyed and celebrated as wonderful opportunities to learn from others, embrace our distinctions, and have them beneficially contribute to our lives. Other differences, however, are not understood or embraced and are, in fact, belittled and stigmatized. Sexual identity falls into this category. It behooves us as a country to become more aware and educated about this category in our identities, in order to understand it, quell our unfounded fear, learn to support one another, and improve our collective mental health.

Recent reports have shown that exposing students and teachers to sexual identity diversity education has sparked some backlash from parents and communities alike. Those opposed are citing concerns over introducing children to LGBTQ+ information, either embedded in the school curriculum or made available in school library reading materials. “Children should remain innocent” seems to be the message. Perhaps parents prefer to discuss this topic privately, at home. Either way, teaching about diversity does not damage one’s innocence or deprive parents of private conversations. In fact, it educates children by improving their awareness, tolerance, and acceptance of others’ differences, and can serve as a catalyst to further parental conversation.

There are kids everywhere who are starting to develop and understand their identities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for them to know that whichever way they identify is okay, that they are not ‘weird’ or ‘different,’ but that in fact we are all different? Wouldn’t it be great for them to be able to explore and discuss their identities and journeys openly, and not have to hide for fear of retribution or bullying?

It is important for these children to know that they are not alone, that they have options, and that they don’t need to contemplate suicide because they believe that their identity makes them not worthy of being in this world.

Starting the conversation early on in life can empower our youth by planting the seed that people are not “one size fits all,” which is the element responsible for our being unique and human. Diversity can be woven into the rich fabric that defines our nation, rather than be a factor that unravels it.

April was National Diversity Awareness Month and we took time to celebrate our country’s cultural melting pot. By embracing our differences, we can show our children and ourselves how to better navigate diversity, which can help us all fit in.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

The United States has often been described as a “melting pot,” defined as diverse cultures and ethnicities coming together to form the rich fabric of our nation. These days, it seems that our fabric is a bit frayed.

DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) is dawning as a significant conversation. Each and every one of us is unique by age, gender, culture/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, geographical location, race, and sexual identity – to name just a few aspects of our identity. Keeping these differences in mind, it is evident that none of us fits a “one size fits all” mold.

Some of these differences, such as cross-cultural cuisine and holidays, are enjoyed and celebrated as wonderful opportunities to learn from others, embrace our distinctions, and have them beneficially contribute to our lives. Other differences, however, are not understood or embraced and are, in fact, belittled and stigmatized. Sexual identity falls into this category. It behooves us as a country to become more aware and educated about this category in our identities, in order to understand it, quell our unfounded fear, learn to support one another, and improve our collective mental health.

Recent reports have shown that exposing students and teachers to sexual identity diversity education has sparked some backlash from parents and communities alike. Those opposed are citing concerns over introducing children to LGBTQ+ information, either embedded in the school curriculum or made available in school library reading materials. “Children should remain innocent” seems to be the message. Perhaps parents prefer to discuss this topic privately, at home. Either way, teaching about diversity does not damage one’s innocence or deprive parents of private conversations. In fact, it educates children by improving their awareness, tolerance, and acceptance of others’ differences, and can serve as a catalyst to further parental conversation.

There are kids everywhere who are starting to develop and understand their identities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for them to know that whichever way they identify is okay, that they are not ‘weird’ or ‘different,’ but that in fact we are all different? Wouldn’t it be great for them to be able to explore and discuss their identities and journeys openly, and not have to hide for fear of retribution or bullying?

It is important for these children to know that they are not alone, that they have options, and that they don’t need to contemplate suicide because they believe that their identity makes them not worthy of being in this world.

Starting the conversation early on in life can empower our youth by planting the seed that people are not “one size fits all,” which is the element responsible for our being unique and human. Diversity can be woven into the rich fabric that defines our nation, rather than be a factor that unravels it.

April was National Diversity Awareness Month and we took time to celebrate our country’s cultural melting pot. By embracing our differences, we can show our children and ourselves how to better navigate diversity, which can help us all fit in.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

The United States has often been described as a “melting pot,” defined as diverse cultures and ethnicities coming together to form the rich fabric of our nation. These days, it seems that our fabric is a bit frayed.

DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) is dawning as a significant conversation. Each and every one of us is unique by age, gender, culture/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, geographical location, race, and sexual identity – to name just a few aspects of our identity. Keeping these differences in mind, it is evident that none of us fits a “one size fits all” mold.

Some of these differences, such as cross-cultural cuisine and holidays, are enjoyed and celebrated as wonderful opportunities to learn from others, embrace our distinctions, and have them beneficially contribute to our lives. Other differences, however, are not understood or embraced and are, in fact, belittled and stigmatized. Sexual identity falls into this category. It behooves us as a country to become more aware and educated about this category in our identities, in order to understand it, quell our unfounded fear, learn to support one another, and improve our collective mental health.

Recent reports have shown that exposing students and teachers to sexual identity diversity education has sparked some backlash from parents and communities alike. Those opposed are citing concerns over introducing children to LGBTQ+ information, either embedded in the school curriculum or made available in school library reading materials. “Children should remain innocent” seems to be the message. Perhaps parents prefer to discuss this topic privately, at home. Either way, teaching about diversity does not damage one’s innocence or deprive parents of private conversations. In fact, it educates children by improving their awareness, tolerance, and acceptance of others’ differences, and can serve as a catalyst to further parental conversation.

There are kids everywhere who are starting to develop and understand their identities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for them to know that whichever way they identify is okay, that they are not ‘weird’ or ‘different,’ but that in fact we are all different? Wouldn’t it be great for them to be able to explore and discuss their identities and journeys openly, and not have to hide for fear of retribution or bullying?

It is important for these children to know that they are not alone, that they have options, and that they don’t need to contemplate suicide because they believe that their identity makes them not worthy of being in this world.

Starting the conversation early on in life can empower our youth by planting the seed that people are not “one size fits all,” which is the element responsible for our being unique and human. Diversity can be woven into the rich fabric that defines our nation, rather than be a factor that unravels it.

April was National Diversity Awareness Month and we took time to celebrate our country’s cultural melting pot. By embracing our differences, we can show our children and ourselves how to better navigate diversity, which can help us all fit in.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Widespread prescribing of stimulants with other CNS-active meds

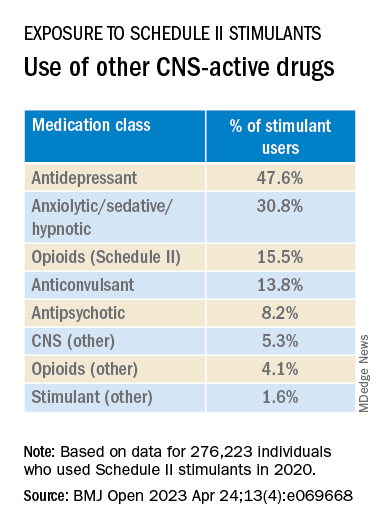

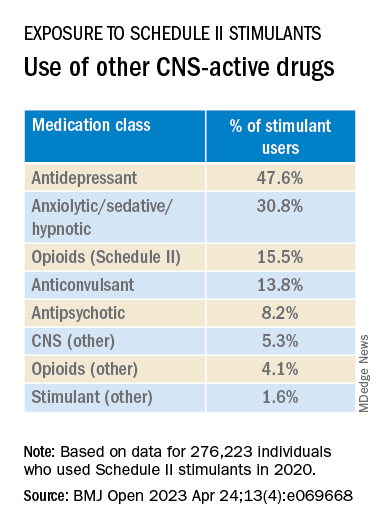

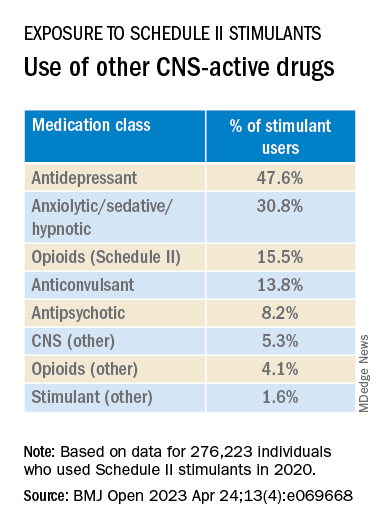

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed prescription drug claims for over 9.1 million U.S. adults over a 1-year period and found that 276,223 (3%) had used a schedule II stimulant, such as methylphenidate and amphetamines, during that time. Of these 276,223 patients, 45% combined these agents with one or more additional CNS-active drugs and almost 25% were simultaneously using two or more additional CNS-active drugs.

Close to half of the stimulant users were taking an antidepressant, while close to one-third filled prescriptions for anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic meditations, and one-fifth received opioid prescriptions.

The widespread, often off-label use of these stimulants in combination therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics, opioids, and other psychoactive drugs, “reveals new patterns of utilization beyond the approved use of stimulants as monotherapy for ADHD, but because there are so few studies of these kinds of combination therapy, both the advantages and additional risks [of this type of prescribing] remain unknown,” study investigator Thomas J. Moore, AB, faculty associate in epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in BMJ Open.

‘Dangerous’ substances

Amphetamines and methylphenidate are CNS stimulants that have been in use for almost a century. Like opioids and barbiturates, they’re considered “dangerous” and classified as schedule II Controlled Substances because of their high potential for abuse.

Over many years, these stimulants have been used for multiple purposes, including nasal congestion, narcolepsy, appetite suppression, binge eating, depression, senile behavior, lethargy, and ADHD, the researchers note.

Observational studies suggest medical use of these agents has been increasing in the United States. The investigators conducted previous research that revealed a 79% increase from 2013 to 2018 in the number of adults who self-report their use. The current study, said Mr. Moore, explores how these stimulants are being used.

For the study, data was extracted from the MarketScan 2019 and 2020 Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases, focusing on 9.1 million adults aged 19-64 years who were continuously enrolled in an included commercial benefit plan from Oct. 1, 2019 to Dec. 31, 2020.

The primary outcome consisted of an outpatient prescription claim, service date, and days’ supply for the CNS-active drugs.

The researchers defined “combination-2” therapy as 60 or more days of combination treatment with a schedule II stimulant and at least one additional CNS-active drug. “Combination-3” therapy was defined as the addition of at least two additional CNS-active drugs.

The researchers used service date and days’ supply to examine the number of stimulant and other CNS-active drugs for each of the days of 2020.

CNS-active drug classes included antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, opioids, anticonvulsants, and other CNS-active drugs.

Prescribing cascade

Of the total number of adults enrolled, 3% (n = 276,223) were taking schedule II stimulants during 2020, with a median of 8 (interquartile range, 4-11) prescriptions. These drugs provided 227 (IQR, 110-322) treatment days of exposure.

Among those taking stimulants 45.5% combined the use of at least one additional CNS-active drug for a median of 213 (IQR, 126-301) treatment days; and 24.3% used at least two additional CNS-active drugs for a median of 182 (IQR, 108-276) days.

“Clinicians should beware of the prescribing cascade. Sometimes it begins with an antidepressant that causes too much sedation, so a stimulant gets added, which leads to insomnia, so alprazolam gets added to the mix,” Mr. Moore said.

He cautioned that this “leaves a patient with multiple drugs, all with discontinuation effects of different kinds and clashing effects.”

These new findings, the investigators note, “add new public health concerns to those raised by our previous study. ... this more-detailed profile reveals several new patterns.”

Most patients become “long-term users” once treatment has started, with 75% continuing for a 1-year period.

“This underscores the possible risks of nonmedical use and dependence that have warranted the classification of these drugs as having high potential for psychological or physical dependence and their prominent appearance in toxicology drug rankings of fatal overdose cases,” they write.

They note that the data “do not indicate which intervention may have come first – a stimulant added to compensate for excess sedation from the benzodiazepine, or the alprazolam added to calm excessive CNS stimulation and/or insomnia from the stimulants or other drugs.”

Several limitations cited by the authors include the fact that, although the population encompassed 9.1 million people, it “may not represent all commercially insured adults,” and it doesn’t include people who aren’t covered by commercial insurance.

Moreover, the MarketScan dataset included up to four diagnosis codes for each outpatient and emergency department encounter; therefore, it was not possible to directly link the diagnoses to specific prescription drug claims, and thus the diagnoses were not evaluated.

“Since many providers will not accept a drug claim for a schedule II stimulant without an on-label diagnosis of ADHD,” the authors suspect that “large numbers of this diagnosis were present.”

Complex prescribing regimens

Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law and professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the report “highlights the pharmacological complexity of adults who are treated with stimulants.”

Dr. Olfson, who is a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, and was not involved with the study, observed there is “evidence to support stimulants as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar depression in older adults.”

However, he added, “this indication is unlikely to fully explain the high proportion of nonelderly, stimulant-treated adults who also receive antidepressants.”

These new findings “call for research to increase our understanding of the clinical contexts that motivate these complex prescribing regimens as well as their effectiveness and safety,” said Dr. Olfson.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Mr. Moore declares no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor G. Caleb Alexander, MD, is past chair and a current member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation, for whom he has served as a paid expert witness; and is a past member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. Dr. Olfson declares no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Hearing aids are a ‘powerful’ tool for reducing dementia risk

, new research confirms. A large observational study from the United Kingdom showed a 42% increased risk for dementia in people with hearing loss compared with their peers with no hearing trouble. In addition, there was no increased risk in those with hearing loss who used hearing aids.

“The evidence is building that hearing loss may be the most impactful modifiable risk factor for dementia in mid-life, but the effectiveness of hearing aid use on reducing the risk of dementia in the real world has remained unclear,” Dongshan Zhu, PhD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, said in a news release.

“Our study provides the best evidence to date to suggest that hearing aids could be a minimally invasive, cost-effective treatment to mitigate the potential impact of hearing loss on dementia,” Dr. Zhu said.

The study, which was published online in Lancet Public Health, comes on the heels of the 2020 Lancet Commission report on dementia, which suggested hearing loss may be linked to approximately 8% of worldwide dementia cases.

‘Compelling’ evidence

For the study, investigators analyzed longitudinal data on 437,704 individuals, most of whom were White, from the UK Biobank (54% female; mean age at baseline, 56 years). Roughly three quarters of the cohort had no hearing loss and one quarter had some level of hearing loss, with 12% of these individuals using hearing aids.

After the researchers controlled for relevant cofactors, compared with people without hearing loss, those with hearing loss who were not using hearing aids had an increased risk for all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29-1.56).

No increased risk was seen in people with hearing loss who were using hearing aids (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.10).

The positive association of hearing aid use was observed in all-cause dementia and cause-specific dementia subtypes, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and non–Alzheimer’s disease nonvascular dementia.

The data also suggest that the protection against dementia conferred by hearing aid use most likely stems from direct effects from hearing aids rather than indirect mediators, such as social isolation, loneliness, and low mood.

Dr. Zhu said the findings highlight the “urgent need” for the early use of hearing aids when an individual starts having trouble hearing.

“A group effort from across society is necessary, including raising awareness of hearing loss and the potential links with dementia; increasing accessibility to hearing aids by reducing cost; and more support for primary care workers to screen for hearing impairment, raise awareness, and deliver treatment such as fitting hearing aids,” Dr. Zhu said.

Writing in a linked comment, Gill Livingston, MD, and Sergi Costafreda, MD, PhD, with University College London, noted that with addition of this study, “the evidence that hearing aids are a powerful tool to reduce the risk of dementia in people with hearing loss, is as good as possible without randomized controlled trials, which might not be practically possible or ethical because people with hearing loss should not be stopped from using effective treatments.”

“The evidence is compelling that treating hearing loss is a promising way of reducing dementia risk. This is the time to increase awareness of and detection of hearing loss, as well as the acceptability and usability of hearing aids,” Dr. Livingston and Dr. Costafreda added.

High-quality evidence – with caveats

Several experts offered perspective on the analysis in a statement from the U.K.-based nonprofit Science Media Centre, which was not involved with the conduct of this study. Charles Marshall, MRCP, PhD, with Queen Mary University of London, said that the study provides “high-quality evidence” that those with hearing loss who use hearing aids are at lower risk for dementia than are those with hearing loss who do not use hearing aids.

“This raises the possibility that a proportion of dementia cases could be prevented by using hearing aids to correct hearing loss. However, the observational nature of this study makes it difficult to be sure that hearing aids are actually causing the reduced risk of dementia,” Dr. Marshall added.

“Hearing aids produce slightly distorted sound, and the brain has to adapt to this in order for hearing aids to be helpful,” he said. “People who are at risk of developing dementia in the future may have early changes in their brain that impair this adaptation, and this may lead to them choosing to not use hearing aids. This would confound the association, creating the appearance that hearing aids were reducing dementia risk, when actually their use was just identifying people with relatively healthy brains,” Dr. Marshall added.

Tara Spires-Jones, PhD, with the University of Edinburgh, said this “well-conducted” study confirms previous similar studies showing an association between hearing loss and dementia risk.

Echoing Dr. Marshall, Dr. Spires-Jones noted that this type of study cannot prove conclusively that hearing loss causes dementia.

“For example,” she said, “it is possible that people who are already in the very early stages of disease are less likely to seek help for hearing loss. However, on balance, this study and the rest of the data in the field indicate that keeping your brain healthy and engaged reduces dementia risk.”

Dr. Spires-Jones said that she agrees with the investigators that it’s “important to help people with hearing loss to get effective hearing aids to help keep their brains engaged through allowing richer social interactions.”

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Shandong Province, Taishan Scholars Project, China Medical Board, and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. Dr. Zhu, Dr. Livingston, Dr. Costafreda, Dr. Marshall, and Dr. Spires-Jones have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research confirms. A large observational study from the United Kingdom showed a 42% increased risk for dementia in people with hearing loss compared with their peers with no hearing trouble. In addition, there was no increased risk in those with hearing loss who used hearing aids.

“The evidence is building that hearing loss may be the most impactful modifiable risk factor for dementia in mid-life, but the effectiveness of hearing aid use on reducing the risk of dementia in the real world has remained unclear,” Dongshan Zhu, PhD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, said in a news release.

“Our study provides the best evidence to date to suggest that hearing aids could be a minimally invasive, cost-effective treatment to mitigate the potential impact of hearing loss on dementia,” Dr. Zhu said.

The study, which was published online in Lancet Public Health, comes on the heels of the 2020 Lancet Commission report on dementia, which suggested hearing loss may be linked to approximately 8% of worldwide dementia cases.

‘Compelling’ evidence

For the study, investigators analyzed longitudinal data on 437,704 individuals, most of whom were White, from the UK Biobank (54% female; mean age at baseline, 56 years). Roughly three quarters of the cohort had no hearing loss and one quarter had some level of hearing loss, with 12% of these individuals using hearing aids.

After the researchers controlled for relevant cofactors, compared with people without hearing loss, those with hearing loss who were not using hearing aids had an increased risk for all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29-1.56).

No increased risk was seen in people with hearing loss who were using hearing aids (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.10).

The positive association of hearing aid use was observed in all-cause dementia and cause-specific dementia subtypes, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and non–Alzheimer’s disease nonvascular dementia.

The data also suggest that the protection against dementia conferred by hearing aid use most likely stems from direct effects from hearing aids rather than indirect mediators, such as social isolation, loneliness, and low mood.

Dr. Zhu said the findings highlight the “urgent need” for the early use of hearing aids when an individual starts having trouble hearing.

“A group effort from across society is necessary, including raising awareness of hearing loss and the potential links with dementia; increasing accessibility to hearing aids by reducing cost; and more support for primary care workers to screen for hearing impairment, raise awareness, and deliver treatment such as fitting hearing aids,” Dr. Zhu said.

Writing in a linked comment, Gill Livingston, MD, and Sergi Costafreda, MD, PhD, with University College London, noted that with addition of this study, “the evidence that hearing aids are a powerful tool to reduce the risk of dementia in people with hearing loss, is as good as possible without randomized controlled trials, which might not be practically possible or ethical because people with hearing loss should not be stopped from using effective treatments.”

“The evidence is compelling that treating hearing loss is a promising way of reducing dementia risk. This is the time to increase awareness of and detection of hearing loss, as well as the acceptability and usability of hearing aids,” Dr. Livingston and Dr. Costafreda added.

High-quality evidence – with caveats

Several experts offered perspective on the analysis in a statement from the U.K.-based nonprofit Science Media Centre, which was not involved with the conduct of this study. Charles Marshall, MRCP, PhD, with Queen Mary University of London, said that the study provides “high-quality evidence” that those with hearing loss who use hearing aids are at lower risk for dementia than are those with hearing loss who do not use hearing aids.

“This raises the possibility that a proportion of dementia cases could be prevented by using hearing aids to correct hearing loss. However, the observational nature of this study makes it difficult to be sure that hearing aids are actually causing the reduced risk of dementia,” Dr. Marshall added.

“Hearing aids produce slightly distorted sound, and the brain has to adapt to this in order for hearing aids to be helpful,” he said. “People who are at risk of developing dementia in the future may have early changes in their brain that impair this adaptation, and this may lead to them choosing to not use hearing aids. This would confound the association, creating the appearance that hearing aids were reducing dementia risk, when actually their use was just identifying people with relatively healthy brains,” Dr. Marshall added.

Tara Spires-Jones, PhD, with the University of Edinburgh, said this “well-conducted” study confirms previous similar studies showing an association between hearing loss and dementia risk.

Echoing Dr. Marshall, Dr. Spires-Jones noted that this type of study cannot prove conclusively that hearing loss causes dementia.

“For example,” she said, “it is possible that people who are already in the very early stages of disease are less likely to seek help for hearing loss. However, on balance, this study and the rest of the data in the field indicate that keeping your brain healthy and engaged reduces dementia risk.”

Dr. Spires-Jones said that she agrees with the investigators that it’s “important to help people with hearing loss to get effective hearing aids to help keep their brains engaged through allowing richer social interactions.”

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Shandong Province, Taishan Scholars Project, China Medical Board, and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. Dr. Zhu, Dr. Livingston, Dr. Costafreda, Dr. Marshall, and Dr. Spires-Jones have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research confirms. A large observational study from the United Kingdom showed a 42% increased risk for dementia in people with hearing loss compared with their peers with no hearing trouble. In addition, there was no increased risk in those with hearing loss who used hearing aids.

“The evidence is building that hearing loss may be the most impactful modifiable risk factor for dementia in mid-life, but the effectiveness of hearing aid use on reducing the risk of dementia in the real world has remained unclear,” Dongshan Zhu, PhD, with Shandong University, Jinan, China, said in a news release.

“Our study provides the best evidence to date to suggest that hearing aids could be a minimally invasive, cost-effective treatment to mitigate the potential impact of hearing loss on dementia,” Dr. Zhu said.

The study, which was published online in Lancet Public Health, comes on the heels of the 2020 Lancet Commission report on dementia, which suggested hearing loss may be linked to approximately 8% of worldwide dementia cases.

‘Compelling’ evidence

For the study, investigators analyzed longitudinal data on 437,704 individuals, most of whom were White, from the UK Biobank (54% female; mean age at baseline, 56 years). Roughly three quarters of the cohort had no hearing loss and one quarter had some level of hearing loss, with 12% of these individuals using hearing aids.

After the researchers controlled for relevant cofactors, compared with people without hearing loss, those with hearing loss who were not using hearing aids had an increased risk for all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29-1.56).

No increased risk was seen in people with hearing loss who were using hearing aids (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.10).

The positive association of hearing aid use was observed in all-cause dementia and cause-specific dementia subtypes, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and non–Alzheimer’s disease nonvascular dementia.

The data also suggest that the protection against dementia conferred by hearing aid use most likely stems from direct effects from hearing aids rather than indirect mediators, such as social isolation, loneliness, and low mood.

Dr. Zhu said the findings highlight the “urgent need” for the early use of hearing aids when an individual starts having trouble hearing.

“A group effort from across society is necessary, including raising awareness of hearing loss and the potential links with dementia; increasing accessibility to hearing aids by reducing cost; and more support for primary care workers to screen for hearing impairment, raise awareness, and deliver treatment such as fitting hearing aids,” Dr. Zhu said.

Writing in a linked comment, Gill Livingston, MD, and Sergi Costafreda, MD, PhD, with University College London, noted that with addition of this study, “the evidence that hearing aids are a powerful tool to reduce the risk of dementia in people with hearing loss, is as good as possible without randomized controlled trials, which might not be practically possible or ethical because people with hearing loss should not be stopped from using effective treatments.”

“The evidence is compelling that treating hearing loss is a promising way of reducing dementia risk. This is the time to increase awareness of and detection of hearing loss, as well as the acceptability and usability of hearing aids,” Dr. Livingston and Dr. Costafreda added.

High-quality evidence – with caveats

Several experts offered perspective on the analysis in a statement from the U.K.-based nonprofit Science Media Centre, which was not involved with the conduct of this study. Charles Marshall, MRCP, PhD, with Queen Mary University of London, said that the study provides “high-quality evidence” that those with hearing loss who use hearing aids are at lower risk for dementia than are those with hearing loss who do not use hearing aids.

“This raises the possibility that a proportion of dementia cases could be prevented by using hearing aids to correct hearing loss. However, the observational nature of this study makes it difficult to be sure that hearing aids are actually causing the reduced risk of dementia,” Dr. Marshall added.

“Hearing aids produce slightly distorted sound, and the brain has to adapt to this in order for hearing aids to be helpful,” he said. “People who are at risk of developing dementia in the future may have early changes in their brain that impair this adaptation, and this may lead to them choosing to not use hearing aids. This would confound the association, creating the appearance that hearing aids were reducing dementia risk, when actually their use was just identifying people with relatively healthy brains,” Dr. Marshall added.

Tara Spires-Jones, PhD, with the University of Edinburgh, said this “well-conducted” study confirms previous similar studies showing an association between hearing loss and dementia risk.

Echoing Dr. Marshall, Dr. Spires-Jones noted that this type of study cannot prove conclusively that hearing loss causes dementia.

“For example,” she said, “it is possible that people who are already in the very early stages of disease are less likely to seek help for hearing loss. However, on balance, this study and the rest of the data in the field indicate that keeping your brain healthy and engaged reduces dementia risk.”

Dr. Spires-Jones said that she agrees with the investigators that it’s “important to help people with hearing loss to get effective hearing aids to help keep their brains engaged through allowing richer social interactions.”

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Shandong Province, Taishan Scholars Project, China Medical Board, and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. Dr. Zhu, Dr. Livingston, Dr. Costafreda, Dr. Marshall, and Dr. Spires-Jones have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Most children with ADHD are not receiving treatment

Just more than one-third (34.8%) had received either treatment.

Researchers, led by Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law and professor of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, also found that girls were much less likely to get medications.

In this cross-sectional sample taken from 11, 723 children in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, 1,206 children aged 9 and 10 years had parent-reported ADHD, and of those children, 15.7% of boys and 7% of girls were currently receiving ADHD medications. The parents reported the children met ADHD criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Diagnoses have doubled but treatment numbers lag

Report authors noted that the percentage of U.S. children whose parents report their child has been diagnosed with ADHD has nearly doubled over 2 decades from 5.5% in 1999 to 9.8% in 2018. That has led to misperceptions among professionals and the public that the disorder is overdiagnosed and overtreated, the authors wrote.

However, they wrote, “a focus on the increasing numbers of children treated for ADHD does not give a sense of what fraction of children in the population with ADHD receive treatment.”

Higher uptake at lower income and education levels

Researchers also found that, contrary to popular belief, children with ADHD from families with lower educational levels and lower income were more likely than those with higher educational levels and higher incomes to have received outpatient mental health care.

Among children with ADHD whose parents did not have a high school education, 32.2% of children were receiving medications while among children of parents with a bachelor’s degree 11.5% received medications.

Among children from families with incomes of less than $25 000, 36.5% were receiving outpatient mental health care, compared with 20.1% of those from families with incomes of $75,000 or more.

“These patterns suggest that attitudinal rather than socioeconomic factors often impede the flow of children with ADHD into treatment,” they wrote.

Black children less likely to receive medications

The researchers found that substantially more White children (14.8% [104 of 759]) than Black children (9.4% [22 of 206]), received medication, a finding consistent with previous research.

“Population-based racial and ethnic gradients exist in prescriptions for stimulants and other controlled substances, with the highest rates in majority-White areas,” the authors wrote. “As a result of structural racism, Black parents’ perspectives might further influence ADHD management decisions through mistrust in clinicians and concerns over safety and efficacy of stimulants.”

“Physician efforts to recognize and manage their own implicit biases, together with patient-centered clinical approaches that promote shared decision-making,” might help narrow the treatment gap, the authors wrote. That includes talking with Black parents about their knowledge and beliefs concerning managing ADHD, they added.

Confirming diagnosis critical

The authors noted that not all children with parent-reported ADHD need treatment or would benefit from it.

Lenard Adler, MD, director of the adult ADHD program and professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone Health, who was not part of the current study, said this research emphasizes the urgency of clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Adler was part of a team of researchers that found similar low numbers for treatment among adults with ADHD.

The current results highlight that “we want to get the diagnosis correct so that people who receive a diagnosis actually have it and, if they do, that they have access to care. Because the consequences for not having treatment for ADHD are significant,” Dr. Adler said.

He urged physicians who diagnose ADHD to make follow-up part of the care plan or these treatment gaps will persist.

The authors wrote that the results suggest a need to increase availability for mental health services and better communicate symptoms among parents, teachers, and primary care providers.

The authors declare no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adler has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, has done research with Takeda, and has received royalty payments from NYU for licensing of ADHD training materials.

Just more than one-third (34.8%) had received either treatment.

Researchers, led by Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law and professor of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, also found that girls were much less likely to get medications.

In this cross-sectional sample taken from 11, 723 children in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, 1,206 children aged 9 and 10 years had parent-reported ADHD, and of those children, 15.7% of boys and 7% of girls were currently receiving ADHD medications. The parents reported the children met ADHD criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Diagnoses have doubled but treatment numbers lag

Report authors noted that the percentage of U.S. children whose parents report their child has been diagnosed with ADHD has nearly doubled over 2 decades from 5.5% in 1999 to 9.8% in 2018. That has led to misperceptions among professionals and the public that the disorder is overdiagnosed and overtreated, the authors wrote.

However, they wrote, “a focus on the increasing numbers of children treated for ADHD does not give a sense of what fraction of children in the population with ADHD receive treatment.”

Higher uptake at lower income and education levels

Researchers also found that, contrary to popular belief, children with ADHD from families with lower educational levels and lower income were more likely than those with higher educational levels and higher incomes to have received outpatient mental health care.

Among children with ADHD whose parents did not have a high school education, 32.2% of children were receiving medications while among children of parents with a bachelor’s degree 11.5% received medications.

Among children from families with incomes of less than $25 000, 36.5% were receiving outpatient mental health care, compared with 20.1% of those from families with incomes of $75,000 or more.

“These patterns suggest that attitudinal rather than socioeconomic factors often impede the flow of children with ADHD into treatment,” they wrote.

Black children less likely to receive medications

The researchers found that substantially more White children (14.8% [104 of 759]) than Black children (9.4% [22 of 206]), received medication, a finding consistent with previous research.

“Population-based racial and ethnic gradients exist in prescriptions for stimulants and other controlled substances, with the highest rates in majority-White areas,” the authors wrote. “As a result of structural racism, Black parents’ perspectives might further influence ADHD management decisions through mistrust in clinicians and concerns over safety and efficacy of stimulants.”

“Physician efforts to recognize and manage their own implicit biases, together with patient-centered clinical approaches that promote shared decision-making,” might help narrow the treatment gap, the authors wrote. That includes talking with Black parents about their knowledge and beliefs concerning managing ADHD, they added.

Confirming diagnosis critical

The authors noted that not all children with parent-reported ADHD need treatment or would benefit from it.

Lenard Adler, MD, director of the adult ADHD program and professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone Health, who was not part of the current study, said this research emphasizes the urgency of clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Adler was part of a team of researchers that found similar low numbers for treatment among adults with ADHD.

The current results highlight that “we want to get the diagnosis correct so that people who receive a diagnosis actually have it and, if they do, that they have access to care. Because the consequences for not having treatment for ADHD are significant,” Dr. Adler said.

He urged physicians who diagnose ADHD to make follow-up part of the care plan or these treatment gaps will persist.

The authors wrote that the results suggest a need to increase availability for mental health services and better communicate symptoms among parents, teachers, and primary care providers.

The authors declare no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adler has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, has done research with Takeda, and has received royalty payments from NYU for licensing of ADHD training materials.

Just more than one-third (34.8%) had received either treatment.

Researchers, led by Mark Olfson, MD, MPH, Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law and professor of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, New York, also found that girls were much less likely to get medications.

In this cross-sectional sample taken from 11, 723 children in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, 1,206 children aged 9 and 10 years had parent-reported ADHD, and of those children, 15.7% of boys and 7% of girls were currently receiving ADHD medications. The parents reported the children met ADHD criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Diagnoses have doubled but treatment numbers lag

Report authors noted that the percentage of U.S. children whose parents report their child has been diagnosed with ADHD has nearly doubled over 2 decades from 5.5% in 1999 to 9.8% in 2018. That has led to misperceptions among professionals and the public that the disorder is overdiagnosed and overtreated, the authors wrote.

However, they wrote, “a focus on the increasing numbers of children treated for ADHD does not give a sense of what fraction of children in the population with ADHD receive treatment.”

Higher uptake at lower income and education levels

Researchers also found that, contrary to popular belief, children with ADHD from families with lower educational levels and lower income were more likely than those with higher educational levels and higher incomes to have received outpatient mental health care.

Among children with ADHD whose parents did not have a high school education, 32.2% of children were receiving medications while among children of parents with a bachelor’s degree 11.5% received medications.

Among children from families with incomes of less than $25 000, 36.5% were receiving outpatient mental health care, compared with 20.1% of those from families with incomes of $75,000 or more.

“These patterns suggest that attitudinal rather than socioeconomic factors often impede the flow of children with ADHD into treatment,” they wrote.

Black children less likely to receive medications

The researchers found that substantially more White children (14.8% [104 of 759]) than Black children (9.4% [22 of 206]), received medication, a finding consistent with previous research.

“Population-based racial and ethnic gradients exist in prescriptions for stimulants and other controlled substances, with the highest rates in majority-White areas,” the authors wrote. “As a result of structural racism, Black parents’ perspectives might further influence ADHD management decisions through mistrust in clinicians and concerns over safety and efficacy of stimulants.”

“Physician efforts to recognize and manage their own implicit biases, together with patient-centered clinical approaches that promote shared decision-making,” might help narrow the treatment gap, the authors wrote. That includes talking with Black parents about their knowledge and beliefs concerning managing ADHD, they added.

Confirming diagnosis critical

The authors noted that not all children with parent-reported ADHD need treatment or would benefit from it.

Lenard Adler, MD, director of the adult ADHD program and professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone Health, who was not part of the current study, said this research emphasizes the urgency of clinical diagnosis.

Dr. Adler was part of a team of researchers that found similar low numbers for treatment among adults with ADHD.

The current results highlight that “we want to get the diagnosis correct so that people who receive a diagnosis actually have it and, if they do, that they have access to care. Because the consequences for not having treatment for ADHD are significant,” Dr. Adler said.

He urged physicians who diagnose ADHD to make follow-up part of the care plan or these treatment gaps will persist.

The authors wrote that the results suggest a need to increase availability for mental health services and better communicate symptoms among parents, teachers, and primary care providers.

The authors declare no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adler has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, has done research with Takeda, and has received royalty payments from NYU for licensing of ADHD training materials.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Long-term impact of childhood trauma explained

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).