User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Reimagining psychiatric assessment and interventions as procedures

Many psychiatric physicians lament the dearth of procedures in psychiatry compared to other medical specialties such as surgery, cardiology, gastroenterology, or radiology. The few procedures in psychiatry include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation, which are restricted to a small number of sites and not available for most psychiatric practitioners. This lack of tangible/physical procedures should not be surprising because psychiatry deals with disorders of the mind, which are invisible.

However, when one closely examines what psychiatrists do in daily practice to heal our patients, most of what we do actually qualifies as “procedures” although no hardware, machines, or gadgets are involved. Treating psychiatric brain disorders (aka mental illness) requires exquisite skills and expertise, just like medical specialties that use machines to measure or treat various body organs.

It’s time to relabel psychiatric interventions as procedures designed to improve anomalous thoughts, affect, emotions, cognition, and behavior. After giving it some thought (and with a bit of tongue in cheek), I came up with the following list of “psychiatric procedures”:

- Psychosocial exploratory laparotomy: The comprehensive psychiatric assessment and mental status exam.

- Chemotherapy: Oral or injective pharmacotherapeutic intervention.

- Psychoplastic repair: Neuroplasticity, including neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine regeneration, have been shown to be associated with both psychotherapy and psychotropic medications.1,2

- Suicidectomy: Extracting the lethal urge to die by suicide.

- Anger debridement: Removing the irritability and destructive anger outbursts frequently associated with various psychopathologies.

- Anxiety ablation: Eliminating the noxious emotional state of anxiety and frightening panic attacks.

- Empathy infusion: Enabling patients to become more understanding of other people and bolstering their impaired “theory of mind.”

- Personality transplant: Replacing a maladaptive personality with a healthier one (eg, using dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder).

- Cognitive LASIK: To improve insight, analogous to how ophthalmologic LASIK improves sight.

- Mental embolectomy: Removing a blockage to repair rigid attitudes and develop “open-mindedness.”

- Behavioral dilation and curettage (D&C): To rid patients of negative attributes such as impulsivity or reckless behavior.

- Psychotherapeutic anesthesia: Numbing emotional pain or severe grief reaction.

- Social anastomosis: Helping patients who are schizoid or isolative via group therapy, an effective interpersonal and social procedure.

- Psychotherapeutic stent: To open the vessels of narrow-mindedness.

- Cortico-psychological resuscitation (CPR): For patients experiencing stress-induced behavioral arrhythmias or emotional infarction.

- Immunotherapy: Using various neuroprotective psychotropic medications with anti-inflammatory properties or employing evidence-based psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavior therapy (aka neuropsychotherapy), which have been shown to reduce inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and cytokines.3

- Psychotherapy: A neuromodulation procedure for a variety of psychiatric disorders.4

- Neurobiological facelift: It is well established that neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine sprouting are significantly increased with both neuroprotective psychotropic medications (antidepressants, lithium, valproate, and second-generationantipsychotics5) as well as with psychotherapy. There is growing evidence of “premature brain aging” in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, with shrinkage in the volume of the cortex and subcortical regions, especially the hippocampus. Psychiatric biopsychosocial intervention rebuilds those brain regions by stimulating and replenishing the neuropil and neurogenic regions (dentate gyrus and subventricular zone). This is like performing virtual plastic surgery on a wrinkled brain and its sagging mind. MRI scans before and after ECT show a remarkable ≥10% increase in the volume of the hippocampus and amygdala, which translates to billions of new neurons, glia, and synapses.6

Reinventing psychiatric therapies as procedures may elicit sarcasm from skeptics, but when you think about it, it is justified. Excising depression is like excising a tumor, not with a scalpel, but virtually. Stabilizing the broken brain and mind after a psychotic episode (aka brain attack) is like stabilizing the heart after a myocardial infarction (aka heart attack). Just because the mind is virtual doesn’t mean it is not “real and tangible.” A desktop computer is visible, but the software that brings it to life is invisible. Healing the human mind requires multiple medical interventions by psychiatrists in hospitals and clinics, just like surgeons and endoscopists or cardiologists. Mental health care is as much procedural as other medical and surgical specialties.

One more thing: the validated clinical rating scales for various psychiatric brain disorders (eg, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale for depression, Young Mania Rating Scale for bipolar mania, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale for anxiety, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for obsessive-compulsive disorder) are actual measurement procedures for the severity of the illness, just as a sphygmomanometer measures blood pressure and its improvement with treatment. There are also multiple cognitive test batteries to measure cognitive impairment.7

Finally, unlike psychiatric reimbursement, which is tethered to time, procedures are compensated more generously, irrespective of the time involved. The complexities of diagnosing and treating psychiatric brain disorders that dangerously disrupt thoughts, feelings, behavior, and cognition are just as intricate and demanding as the diagnosis and treatment of general medical and surgical conditions. They should all be equally appreciated as vital life-saving procedures for the human body, brain, and mind.

1. Nasrallah HA, Hopkins T, Pixley SK. Differential effects of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs on neurogenic regions in rats. Brain Res. 2010;1354:23-29.

2. Tomasino B, Fabbro F. Increases in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and decreases the rostral prefrontal cortex activation after-8 weeks of focused attention based mindfulness meditation. Brain Cogn. 2016;102:46-54.

3. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

4. Nasrallah HA. Optimal psychiatric treatment: Target the brain and avoid the body. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(12):3-6.

5. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

6. Gryglewski G, Lanzenberger R, Silberbauer LR, et al. Meta-analysis of brain structural changes after electroconvulsive therapy in depression. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(4):927-937.

7. Nasrallah HA. The Cognition Self-Assessment Rating Scale for patients with schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(3):30-34.

Many psychiatric physicians lament the dearth of procedures in psychiatry compared to other medical specialties such as surgery, cardiology, gastroenterology, or radiology. The few procedures in psychiatry include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation, which are restricted to a small number of sites and not available for most psychiatric practitioners. This lack of tangible/physical procedures should not be surprising because psychiatry deals with disorders of the mind, which are invisible.

However, when one closely examines what psychiatrists do in daily practice to heal our patients, most of what we do actually qualifies as “procedures” although no hardware, machines, or gadgets are involved. Treating psychiatric brain disorders (aka mental illness) requires exquisite skills and expertise, just like medical specialties that use machines to measure or treat various body organs.

It’s time to relabel psychiatric interventions as procedures designed to improve anomalous thoughts, affect, emotions, cognition, and behavior. After giving it some thought (and with a bit of tongue in cheek), I came up with the following list of “psychiatric procedures”:

- Psychosocial exploratory laparotomy: The comprehensive psychiatric assessment and mental status exam.

- Chemotherapy: Oral or injective pharmacotherapeutic intervention.

- Psychoplastic repair: Neuroplasticity, including neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine regeneration, have been shown to be associated with both psychotherapy and psychotropic medications.1,2

- Suicidectomy: Extracting the lethal urge to die by suicide.

- Anger debridement: Removing the irritability and destructive anger outbursts frequently associated with various psychopathologies.

- Anxiety ablation: Eliminating the noxious emotional state of anxiety and frightening panic attacks.

- Empathy infusion: Enabling patients to become more understanding of other people and bolstering their impaired “theory of mind.”

- Personality transplant: Replacing a maladaptive personality with a healthier one (eg, using dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder).

- Cognitive LASIK: To improve insight, analogous to how ophthalmologic LASIK improves sight.

- Mental embolectomy: Removing a blockage to repair rigid attitudes and develop “open-mindedness.”

- Behavioral dilation and curettage (D&C): To rid patients of negative attributes such as impulsivity or reckless behavior.

- Psychotherapeutic anesthesia: Numbing emotional pain or severe grief reaction.

- Social anastomosis: Helping patients who are schizoid or isolative via group therapy, an effective interpersonal and social procedure.

- Psychotherapeutic stent: To open the vessels of narrow-mindedness.

- Cortico-psychological resuscitation (CPR): For patients experiencing stress-induced behavioral arrhythmias or emotional infarction.

- Immunotherapy: Using various neuroprotective psychotropic medications with anti-inflammatory properties or employing evidence-based psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavior therapy (aka neuropsychotherapy), which have been shown to reduce inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and cytokines.3

- Psychotherapy: A neuromodulation procedure for a variety of psychiatric disorders.4

- Neurobiological facelift: It is well established that neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine sprouting are significantly increased with both neuroprotective psychotropic medications (antidepressants, lithium, valproate, and second-generationantipsychotics5) as well as with psychotherapy. There is growing evidence of “premature brain aging” in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, with shrinkage in the volume of the cortex and subcortical regions, especially the hippocampus. Psychiatric biopsychosocial intervention rebuilds those brain regions by stimulating and replenishing the neuropil and neurogenic regions (dentate gyrus and subventricular zone). This is like performing virtual plastic surgery on a wrinkled brain and its sagging mind. MRI scans before and after ECT show a remarkable ≥10% increase in the volume of the hippocampus and amygdala, which translates to billions of new neurons, glia, and synapses.6

Reinventing psychiatric therapies as procedures may elicit sarcasm from skeptics, but when you think about it, it is justified. Excising depression is like excising a tumor, not with a scalpel, but virtually. Stabilizing the broken brain and mind after a psychotic episode (aka brain attack) is like stabilizing the heart after a myocardial infarction (aka heart attack). Just because the mind is virtual doesn’t mean it is not “real and tangible.” A desktop computer is visible, but the software that brings it to life is invisible. Healing the human mind requires multiple medical interventions by psychiatrists in hospitals and clinics, just like surgeons and endoscopists or cardiologists. Mental health care is as much procedural as other medical and surgical specialties.

One more thing: the validated clinical rating scales for various psychiatric brain disorders (eg, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale for depression, Young Mania Rating Scale for bipolar mania, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale for anxiety, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for obsessive-compulsive disorder) are actual measurement procedures for the severity of the illness, just as a sphygmomanometer measures blood pressure and its improvement with treatment. There are also multiple cognitive test batteries to measure cognitive impairment.7

Finally, unlike psychiatric reimbursement, which is tethered to time, procedures are compensated more generously, irrespective of the time involved. The complexities of diagnosing and treating psychiatric brain disorders that dangerously disrupt thoughts, feelings, behavior, and cognition are just as intricate and demanding as the diagnosis and treatment of general medical and surgical conditions. They should all be equally appreciated as vital life-saving procedures for the human body, brain, and mind.

Many psychiatric physicians lament the dearth of procedures in psychiatry compared to other medical specialties such as surgery, cardiology, gastroenterology, or radiology. The few procedures in psychiatry include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation, which are restricted to a small number of sites and not available for most psychiatric practitioners. This lack of tangible/physical procedures should not be surprising because psychiatry deals with disorders of the mind, which are invisible.

However, when one closely examines what psychiatrists do in daily practice to heal our patients, most of what we do actually qualifies as “procedures” although no hardware, machines, or gadgets are involved. Treating psychiatric brain disorders (aka mental illness) requires exquisite skills and expertise, just like medical specialties that use machines to measure or treat various body organs.

It’s time to relabel psychiatric interventions as procedures designed to improve anomalous thoughts, affect, emotions, cognition, and behavior. After giving it some thought (and with a bit of tongue in cheek), I came up with the following list of “psychiatric procedures”:

- Psychosocial exploratory laparotomy: The comprehensive psychiatric assessment and mental status exam.

- Chemotherapy: Oral or injective pharmacotherapeutic intervention.

- Psychoplastic repair: Neuroplasticity, including neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine regeneration, have been shown to be associated with both psychotherapy and psychotropic medications.1,2

- Suicidectomy: Extracting the lethal urge to die by suicide.

- Anger debridement: Removing the irritability and destructive anger outbursts frequently associated with various psychopathologies.

- Anxiety ablation: Eliminating the noxious emotional state of anxiety and frightening panic attacks.

- Empathy infusion: Enabling patients to become more understanding of other people and bolstering their impaired “theory of mind.”

- Personality transplant: Replacing a maladaptive personality with a healthier one (eg, using dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder).

- Cognitive LASIK: To improve insight, analogous to how ophthalmologic LASIK improves sight.

- Mental embolectomy: Removing a blockage to repair rigid attitudes and develop “open-mindedness.”

- Behavioral dilation and curettage (D&C): To rid patients of negative attributes such as impulsivity or reckless behavior.

- Psychotherapeutic anesthesia: Numbing emotional pain or severe grief reaction.

- Social anastomosis: Helping patients who are schizoid or isolative via group therapy, an effective interpersonal and social procedure.

- Psychotherapeutic stent: To open the vessels of narrow-mindedness.

- Cortico-psychological resuscitation (CPR): For patients experiencing stress-induced behavioral arrhythmias or emotional infarction.

- Immunotherapy: Using various neuroprotective psychotropic medications with anti-inflammatory properties or employing evidence-based psychotherapy such as cognitive-behavior therapy (aka neuropsychotherapy), which have been shown to reduce inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and cytokines.3

- Psychotherapy: A neuromodulation procedure for a variety of psychiatric disorders.4

- Neurobiological facelift: It is well established that neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine sprouting are significantly increased with both neuroprotective psychotropic medications (antidepressants, lithium, valproate, and second-generationantipsychotics5) as well as with psychotherapy. There is growing evidence of “premature brain aging” in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, with shrinkage in the volume of the cortex and subcortical regions, especially the hippocampus. Psychiatric biopsychosocial intervention rebuilds those brain regions by stimulating and replenishing the neuropil and neurogenic regions (dentate gyrus and subventricular zone). This is like performing virtual plastic surgery on a wrinkled brain and its sagging mind. MRI scans before and after ECT show a remarkable ≥10% increase in the volume of the hippocampus and amygdala, which translates to billions of new neurons, glia, and synapses.6

Reinventing psychiatric therapies as procedures may elicit sarcasm from skeptics, but when you think about it, it is justified. Excising depression is like excising a tumor, not with a scalpel, but virtually. Stabilizing the broken brain and mind after a psychotic episode (aka brain attack) is like stabilizing the heart after a myocardial infarction (aka heart attack). Just because the mind is virtual doesn’t mean it is not “real and tangible.” A desktop computer is visible, but the software that brings it to life is invisible. Healing the human mind requires multiple medical interventions by psychiatrists in hospitals and clinics, just like surgeons and endoscopists or cardiologists. Mental health care is as much procedural as other medical and surgical specialties.

One more thing: the validated clinical rating scales for various psychiatric brain disorders (eg, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale for depression, Young Mania Rating Scale for bipolar mania, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale for anxiety, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for obsessive-compulsive disorder) are actual measurement procedures for the severity of the illness, just as a sphygmomanometer measures blood pressure and its improvement with treatment. There are also multiple cognitive test batteries to measure cognitive impairment.7

Finally, unlike psychiatric reimbursement, which is tethered to time, procedures are compensated more generously, irrespective of the time involved. The complexities of diagnosing and treating psychiatric brain disorders that dangerously disrupt thoughts, feelings, behavior, and cognition are just as intricate and demanding as the diagnosis and treatment of general medical and surgical conditions. They should all be equally appreciated as vital life-saving procedures for the human body, brain, and mind.

1. Nasrallah HA, Hopkins T, Pixley SK. Differential effects of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs on neurogenic regions in rats. Brain Res. 2010;1354:23-29.

2. Tomasino B, Fabbro F. Increases in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and decreases the rostral prefrontal cortex activation after-8 weeks of focused attention based mindfulness meditation. Brain Cogn. 2016;102:46-54.

3. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

4. Nasrallah HA. Optimal psychiatric treatment: Target the brain and avoid the body. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(12):3-6.

5. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

6. Gryglewski G, Lanzenberger R, Silberbauer LR, et al. Meta-analysis of brain structural changes after electroconvulsive therapy in depression. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(4):927-937.

7. Nasrallah HA. The Cognition Self-Assessment Rating Scale for patients with schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(3):30-34.

1. Nasrallah HA, Hopkins T, Pixley SK. Differential effects of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs on neurogenic regions in rats. Brain Res. 2010;1354:23-29.

2. Tomasino B, Fabbro F. Increases in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and decreases the rostral prefrontal cortex activation after-8 weeks of focused attention based mindfulness meditation. Brain Cogn. 2016;102:46-54.

3. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

4. Nasrallah HA. Optimal psychiatric treatment: Target the brain and avoid the body. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(12):3-6.

5. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

6. Gryglewski G, Lanzenberger R, Silberbauer LR, et al. Meta-analysis of brain structural changes after electroconvulsive therapy in depression. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(4):927-937.

7. Nasrallah HA. The Cognition Self-Assessment Rating Scale for patients with schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(3):30-34.

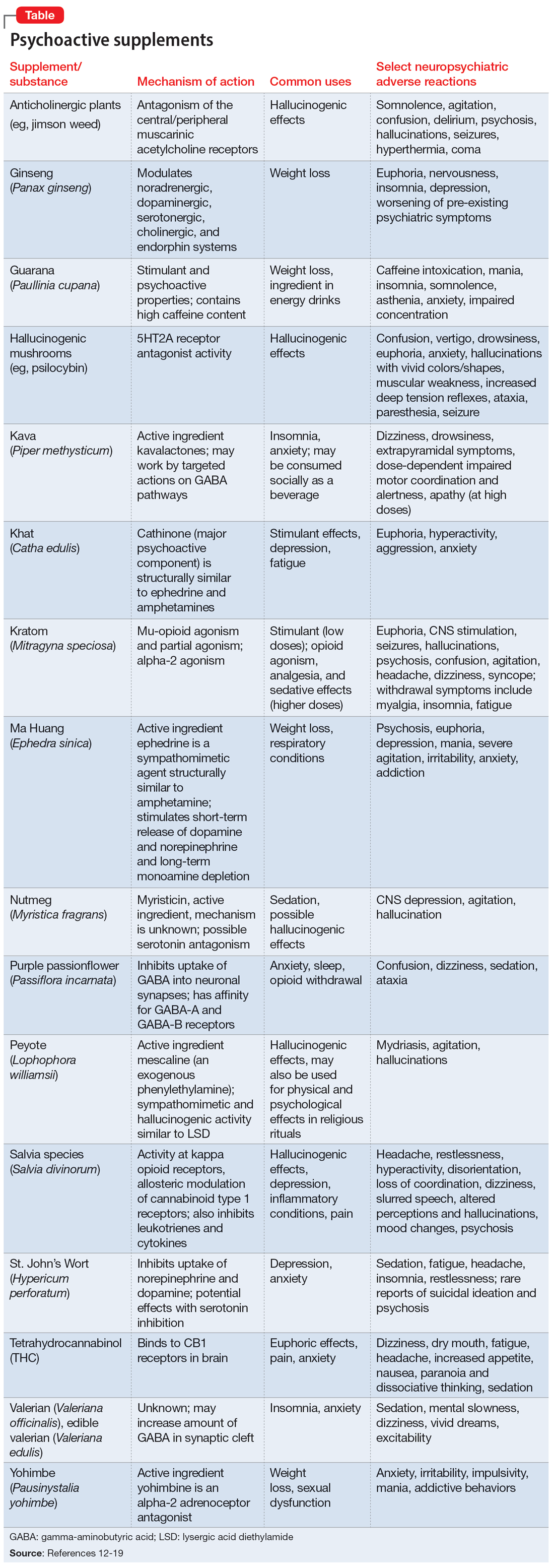

Psychoactive supplements: What to tell patients

Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

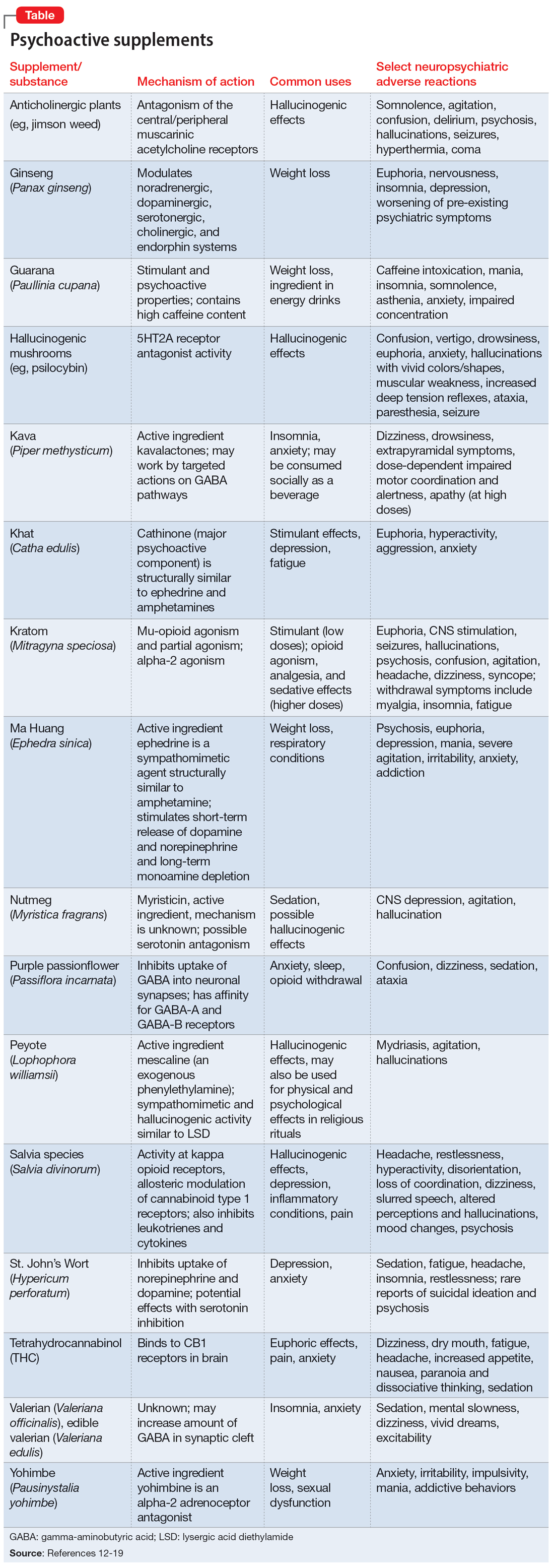

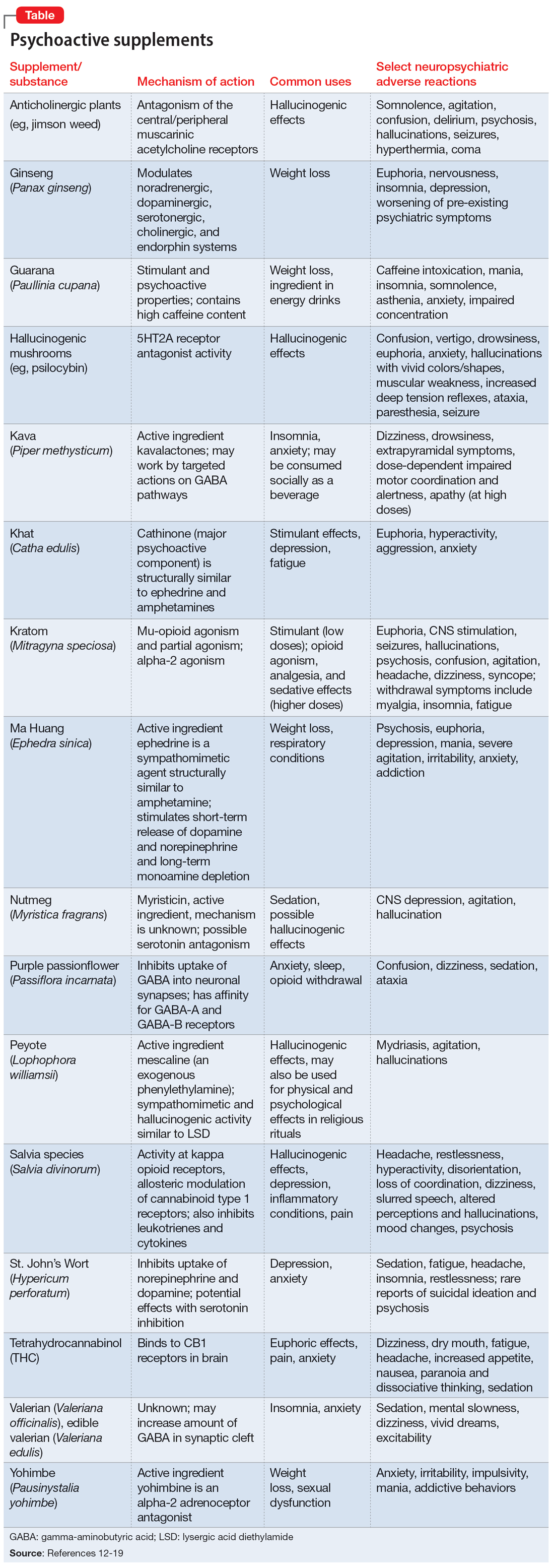

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...

Another category of “supplements” includes medications that are not FDA-approved but are approved for therapeutic use in other countries and readily available in the US via online sources. Such medications include phenibut, a glutamic acid derivative that functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and outside of the US it is prescribed for anxiolysis and other psychiatric indications.22 In the US, phenibut may be used as a nootropic or as a dietary supplement to treat anxiety, sleep problems, and other psychiatric disorders.22 It may also be used recreationally to induce euphoria. Chronic phenibut use results in tolerance and abrupt discontinuation may mimic benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.13,22

Educating patients about supplements

One of the most critical steps in assessing a patient’s supplement use is to directly ask them about their use of herbal or over-the-counter products. Research has consistently shown that patients are unlikely to disclose supplement use unless they are specifically asked.23,24

Additional strategies include25,26:

- Approach patients without judgment; ask open-ended questions to determine their motivations for using supplements.

- Explain the difference between supplements medically necessary to treat vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium) and those without robust clinical evidence.

- Counsel patients that many supplements with psychoactive properties, if indicated, are generally meant to be used short-term and not as substitutes for prescription medications.

- Educate patients that supplements have limited evidence regarding their safety and efficacy, but like prescription medications, supplements may cause organ damage, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions.

- Remind patients that commonly used nutritional supplements/dietary aids, including protein or workout supplements, may contain potentially harmful ingredients.

- Utilize evidence-based resources such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database14 or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov) to review levels of evidence and educate patients.

- When toxicity or withdrawal is suspected, reach out to local poison control centers for guidance.

- For a patient with a potential supplement-related substance use disorder, urine drug screens may be of limited utility and evidence is often sparse; clinicians may need to rely on primary literature such as case reports to guide management.

- If patients wish to continue taking a supplement, recommend they purchase supplements from manufacturers that have achieved the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. Products with the USP mark undergo quality assurance measures to ensure the product contains the ingredients listed on the label in the declared potency and amounts, does not contain harmful levels of contaminants, will be metabolized in the body within a specified amount of time, and has been produced in keeping with FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.

CASE CONTINUED

In the ED, the consulting psychiatry team discusses Mr. D’s use of phenibut with him, and asks if he uses any additional supplements or nonprescription medications. Mr. D discloses he has been anxious and having trouble sleeping, and a friend recommended phenibut as a safe, natural alternative to medication. The team explains to Mr. D that phenibut’s efficacy has not been studied in the US and that based on available evidence, it is likely unsafe. It may have serious adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, and is potentially addictive.

Mr. D says he was unaware of these risks and agrees to stop taking phenibut. The treatment team discharges him from the ED with a referral for outpatient psychiatric services to address his anxiety and insomnia.

Related Resources

- Tillman B. The hidden dangers of supplements: a case of substance-induced psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2020; 19(7):e7-e8. doi:10.12788/cp.0018

- McQueen CE. Herb–drug interactions: caution patients when changing supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2017; 16(6):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine • Fioricet with Codeine

1. Graziano S, Orsolini L, Rotolo MC, et al. Herbal highs: review on psychoactive effects and neuropharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):750-761.

2. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

3. O’Neill-Dee C, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Natural psychoactive substance-related exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(8):813-820.

4. Gray DC, Rutledge CM. Herbal supplements in primary care: patient perceptions, motivations, and effects on use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):6-12.

5. Wu K, Messamore E. Reimagining roles of dietary supplements in psychiatric care. AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E437-E442.

6. Snyder FJ, Dundas ML, Kirkpatrick C, et al. Use and safety perceptions regarding herbal supplements: a study of older persons in southeast Idaho. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(1):81-95.

7. Schulz P, Hede V. Alternative and complementary approaches in psychiatry: beliefs versus evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(3):207-214.

8. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Pub L 103-417, 103rd Cong (1993-1994).

9. Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):478-485.

10. New psychoactive substances. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. November 10, 2021. Updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/new-psychoactive-substances/

11. Shafi A, Berry AJ, Sumnall H, et al. New psychoactive substances: a review and updates. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320967197.

12. Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, et al. Adverse psychiatric effects associated with herbal weight-loss products. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:120679.

13. IBM Micromedex POISINDEX® System. IBM Watson Health. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com

14. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

15. Savage KM, Stough CK, Byrne GJ, et al. Kava for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (K-GAD): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:493.

16. Swogger MT, Smith KE, Garcia-Romeu A, et al. Understanding kratom use: a guide for healthcare providers. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:801855.

17. Modabbernia A, Akhondzadeh S. Saffron, passionflower, valerian and sage for mental health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):85-91.

18. Coffeen U, Pellicer F. Salvia divinorum: from recreational hallucinogenic use to analgesic and anti-inflammatory action. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1069-1076.

19. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Valerian Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Updated March 15, 2013. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Valerian-HealthProfessional

20. An H, Sohn H, Chung S. Phentermine, sibutramine and affective disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(1):7-12.

21. Miliano C, Margiani G, Fattore L, et al. Sales and advertising channels of new psychoactive substances (NPS): internet, social networks, and smartphone apps. Brain Sci. 2018;8(7):123.

22. Hardman MI, Sprung J, Weingarten TN. Acute phenibut withdrawal: a comprehensive literature review and illustrative case report. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019;19(2):125-129.

23. Guzman JR, Paterniti DA, Liu Y, et al. Factors related to disclosure and nondisclosure of dietary supplements in primary care, integrative medicine, and naturopathic medicine. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2019;5(4):10.23937/2469-5793/1510109.

24. Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1573.

25. Aldridge Young C. ‘No miracle cures’: counseling patients about dietary supplements. Pharmacy Today. 2014;February:35.

26. United States Pharmacopeia. USP Verified Mark. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.usp.org/verification-services/verified-mark

Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...

Another category of “supplements” includes medications that are not FDA-approved but are approved for therapeutic use in other countries and readily available in the US via online sources. Such medications include phenibut, a glutamic acid derivative that functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and outside of the US it is prescribed for anxiolysis and other psychiatric indications.22 In the US, phenibut may be used as a nootropic or as a dietary supplement to treat anxiety, sleep problems, and other psychiatric disorders.22 It may also be used recreationally to induce euphoria. Chronic phenibut use results in tolerance and abrupt discontinuation may mimic benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.13,22

Educating patients about supplements

One of the most critical steps in assessing a patient’s supplement use is to directly ask them about their use of herbal or over-the-counter products. Research has consistently shown that patients are unlikely to disclose supplement use unless they are specifically asked.23,24

Additional strategies include25,26:

- Approach patients without judgment; ask open-ended questions to determine their motivations for using supplements.

- Explain the difference between supplements medically necessary to treat vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium) and those without robust clinical evidence.

- Counsel patients that many supplements with psychoactive properties, if indicated, are generally meant to be used short-term and not as substitutes for prescription medications.

- Educate patients that supplements have limited evidence regarding their safety and efficacy, but like prescription medications, supplements may cause organ damage, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions.

- Remind patients that commonly used nutritional supplements/dietary aids, including protein or workout supplements, may contain potentially harmful ingredients.

- Utilize evidence-based resources such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database14 or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov) to review levels of evidence and educate patients.

- When toxicity or withdrawal is suspected, reach out to local poison control centers for guidance.

- For a patient with a potential supplement-related substance use disorder, urine drug screens may be of limited utility and evidence is often sparse; clinicians may need to rely on primary literature such as case reports to guide management.

- If patients wish to continue taking a supplement, recommend they purchase supplements from manufacturers that have achieved the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. Products with the USP mark undergo quality assurance measures to ensure the product contains the ingredients listed on the label in the declared potency and amounts, does not contain harmful levels of contaminants, will be metabolized in the body within a specified amount of time, and has been produced in keeping with FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.

CASE CONTINUED

In the ED, the consulting psychiatry team discusses Mr. D’s use of phenibut with him, and asks if he uses any additional supplements or nonprescription medications. Mr. D discloses he has been anxious and having trouble sleeping, and a friend recommended phenibut as a safe, natural alternative to medication. The team explains to Mr. D that phenibut’s efficacy has not been studied in the US and that based on available evidence, it is likely unsafe. It may have serious adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, and is potentially addictive.

Mr. D says he was unaware of these risks and agrees to stop taking phenibut. The treatment team discharges him from the ED with a referral for outpatient psychiatric services to address his anxiety and insomnia.

Related Resources

- Tillman B. The hidden dangers of supplements: a case of substance-induced psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2020; 19(7):e7-e8. doi:10.12788/cp.0018

- McQueen CE. Herb–drug interactions: caution patients when changing supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2017; 16(6):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine • Fioricet with Codeine

Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...

Another category of “supplements” includes medications that are not FDA-approved but are approved for therapeutic use in other countries and readily available in the US via online sources. Such medications include phenibut, a glutamic acid derivative that functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist in the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. Phenibut was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and outside of the US it is prescribed for anxiolysis and other psychiatric indications.22 In the US, phenibut may be used as a nootropic or as a dietary supplement to treat anxiety, sleep problems, and other psychiatric disorders.22 It may also be used recreationally to induce euphoria. Chronic phenibut use results in tolerance and abrupt discontinuation may mimic benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms.13,22

Educating patients about supplements

One of the most critical steps in assessing a patient’s supplement use is to directly ask them about their use of herbal or over-the-counter products. Research has consistently shown that patients are unlikely to disclose supplement use unless they are specifically asked.23,24

Additional strategies include25,26:

- Approach patients without judgment; ask open-ended questions to determine their motivations for using supplements.

- Explain the difference between supplements medically necessary to treat vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, calcium, magnesium) and those without robust clinical evidence.

- Counsel patients that many supplements with psychoactive properties, if indicated, are generally meant to be used short-term and not as substitutes for prescription medications.

- Educate patients that supplements have limited evidence regarding their safety and efficacy, but like prescription medications, supplements may cause organ damage, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions.

- Remind patients that commonly used nutritional supplements/dietary aids, including protein or workout supplements, may contain potentially harmful ingredients.

- Utilize evidence-based resources such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database14 or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov) to review levels of evidence and educate patients.

- When toxicity or withdrawal is suspected, reach out to local poison control centers for guidance.

- For a patient with a potential supplement-related substance use disorder, urine drug screens may be of limited utility and evidence is often sparse; clinicians may need to rely on primary literature such as case reports to guide management.

- If patients wish to continue taking a supplement, recommend they purchase supplements from manufacturers that have achieved the US Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. Products with the USP mark undergo quality assurance measures to ensure the product contains the ingredients listed on the label in the declared potency and amounts, does not contain harmful levels of contaminants, will be metabolized in the body within a specified amount of time, and has been produced in keeping with FDA Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.

CASE CONTINUED

In the ED, the consulting psychiatry team discusses Mr. D’s use of phenibut with him, and asks if he uses any additional supplements or nonprescription medications. Mr. D discloses he has been anxious and having trouble sleeping, and a friend recommended phenibut as a safe, natural alternative to medication. The team explains to Mr. D that phenibut’s efficacy has not been studied in the US and that based on available evidence, it is likely unsafe. It may have serious adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, and is potentially addictive.

Mr. D says he was unaware of these risks and agrees to stop taking phenibut. The treatment team discharges him from the ED with a referral for outpatient psychiatric services to address his anxiety and insomnia.

Related Resources

- Tillman B. The hidden dangers of supplements: a case of substance-induced psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2020; 19(7):e7-e8. doi:10.12788/cp.0018

- McQueen CE. Herb–drug interactions: caution patients when changing supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2017; 16(6):38-41.

Drug Brand Names

Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine • Fioricet with Codeine

1. Graziano S, Orsolini L, Rotolo MC, et al. Herbal highs: review on psychoactive effects and neuropharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):750-761.

2. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

3. O’Neill-Dee C, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Natural psychoactive substance-related exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(8):813-820.

4. Gray DC, Rutledge CM. Herbal supplements in primary care: patient perceptions, motivations, and effects on use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):6-12.

5. Wu K, Messamore E. Reimagining roles of dietary supplements in psychiatric care. AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E437-E442.

6. Snyder FJ, Dundas ML, Kirkpatrick C, et al. Use and safety perceptions regarding herbal supplements: a study of older persons in southeast Idaho. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(1):81-95.

7. Schulz P, Hede V. Alternative and complementary approaches in psychiatry: beliefs versus evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(3):207-214.

8. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Pub L 103-417, 103rd Cong (1993-1994).

9. Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):478-485.

10. New psychoactive substances. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. November 10, 2021. Updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/new-psychoactive-substances/

11. Shafi A, Berry AJ, Sumnall H, et al. New psychoactive substances: a review and updates. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320967197.

12. Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, et al. Adverse psychiatric effects associated with herbal weight-loss products. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:120679.

13. IBM Micromedex POISINDEX® System. IBM Watson Health. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com

14. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

15. Savage KM, Stough CK, Byrne GJ, et al. Kava for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (K-GAD): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:493.

16. Swogger MT, Smith KE, Garcia-Romeu A, et al. Understanding kratom use: a guide for healthcare providers. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:801855.

17. Modabbernia A, Akhondzadeh S. Saffron, passionflower, valerian and sage for mental health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):85-91.

18. Coffeen U, Pellicer F. Salvia divinorum: from recreational hallucinogenic use to analgesic and anti-inflammatory action. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1069-1076.

19. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Valerian Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Updated March 15, 2013. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Valerian-HealthProfessional

20. An H, Sohn H, Chung S. Phentermine, sibutramine and affective disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(1):7-12.

21. Miliano C, Margiani G, Fattore L, et al. Sales and advertising channels of new psychoactive substances (NPS): internet, social networks, and smartphone apps. Brain Sci. 2018;8(7):123.

22. Hardman MI, Sprung J, Weingarten TN. Acute phenibut withdrawal: a comprehensive literature review and illustrative case report. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019;19(2):125-129.

23. Guzman JR, Paterniti DA, Liu Y, et al. Factors related to disclosure and nondisclosure of dietary supplements in primary care, integrative medicine, and naturopathic medicine. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2019;5(4):10.23937/2469-5793/1510109.

24. Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1573.

25. Aldridge Young C. ‘No miracle cures’: counseling patients about dietary supplements. Pharmacy Today. 2014;February:35.

26. United States Pharmacopeia. USP Verified Mark. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.usp.org/verification-services/verified-mark

1. Graziano S, Orsolini L, Rotolo MC, et al. Herbal highs: review on psychoactive effects and neuropharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(5):750-761.

2. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, et al. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(399):1-8.

3. O’Neill-Dee C, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Natural psychoactive substance-related exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000-2017. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(8):813-820.

4. Gray DC, Rutledge CM. Herbal supplements in primary care: patient perceptions, motivations, and effects on use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):6-12.

5. Wu K, Messamore E. Reimagining roles of dietary supplements in psychiatric care. AMA J Ethics. 2022;24(5):E437-E442.

6. Snyder FJ, Dundas ML, Kirkpatrick C, et al. Use and safety perceptions regarding herbal supplements: a study of older persons in southeast Idaho. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28(1):81-95.

7. Schulz P, Hede V. Alternative and complementary approaches in psychiatry: beliefs versus evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(3):207-214.

8. Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Pub L 103-417, 103rd Cong (1993-1994).

9. Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):478-485.

10. New psychoactive substances. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. November 10, 2021. Updated November 28, 2022. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/new-psychoactive-substances/

11. Shafi A, Berry AJ, Sumnall H, et al. New psychoactive substances: a review and updates. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320967197.

12. Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, et al. Adverse psychiatric effects associated with herbal weight-loss products. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:120679.

13. IBM Micromedex POISINDEX® System. IBM Watson Health. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com

14. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

15. Savage KM, Stough CK, Byrne GJ, et al. Kava for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder (K-GAD): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:493.

16. Swogger MT, Smith KE, Garcia-Romeu A, et al. Understanding kratom use: a guide for healthcare providers. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:801855.

17. Modabbernia A, Akhondzadeh S. Saffron, passionflower, valerian and sage for mental health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(1):85-91.

18. Coffeen U, Pellicer F. Salvia divinorum: from recreational hallucinogenic use to analgesic and anti-inflammatory action. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1069-1076.

19. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Valerian Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Updated March 15, 2013. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Valerian-HealthProfessional

20. An H, Sohn H, Chung S. Phentermine, sibutramine and affective disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11(1):7-12.

21. Miliano C, Margiani G, Fattore L, et al. Sales and advertising channels of new psychoactive substances (NPS): internet, social networks, and smartphone apps. Brain Sci. 2018;8(7):123.

22. Hardman MI, Sprung J, Weingarten TN. Acute phenibut withdrawal: a comprehensive literature review and illustrative case report. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019;19(2):125-129.

23. Guzman JR, Paterniti DA, Liu Y, et al. Factors related to disclosure and nondisclosure of dietary supplements in primary care, integrative medicine, and naturopathic medicine. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2019;5(4):10.23937/2469-5793/1510109.

24. Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1573.

25. Aldridge Young C. ‘No miracle cures’: counseling patients about dietary supplements. Pharmacy Today. 2014;February:35.

26. United States Pharmacopeia. USP Verified Mark. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.usp.org/verification-services/verified-mark

Increased anxiety and depression after menstruation

CASE Increased anxiety and depression

Ms. C, age 29, has bipolar II disorder (BD II) and generalized anxiety disorder. She presents to her outpatient psychiatrist seeking relief from chronic and significant dips in her mood from Day 5 to Day 15 of her menstrual cycle. During this time, she says she experiences increased anxiety, insomnia, frequent tearfulness, and intermittent suicidal ideation.

Ms. C meticulously charts her menstrual cycle using a smartphone app and reports having a regular 28-day cycle. She says she has experienced this worsening of symptoms since the onset of menarche, but her mood generally stabilizes after Day 14 of her cycle–around the time of ovulation–and remains euthymic throughout the premenstrual period.

HISTORY Depression and a change in medication

Ms. C has a history of major depressive episodes and has experienced hypomanic episodes that lasted 1 to 2 weeks and were associated with an elevated mood, high energy, rapid speech, and increased self-confidence. Ms. C says she has chronically high anxiety associated with trouble sleeping, difficulty focusing, restlessness, and muscle tension. When she was receiving care from previous psychiatrists, treatment with lithium, quetiapine, lamotrigine, sertraline, and fluoxetine was not successful, and Ms. C said she had severe anxiety when she tried sertraline and fluoxetine. After several months of substantial mood instability and high anxiety, Ms. C responded well to pregabalin 100 mg 3 times a day, lurasidone 60 mg/d at bedtime, and gabapentin 500 mg/d at bedtime. Over the last 4 months, she reports that her overall mood has been even, and she has been coping well with her anxiety.

Ms. C is married with no children. She uses condoms for birth control. She previously tried taking a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive, but stopped because she said it made her feel very depressed. Ms. C reports no history of substance use. She is employed, says she has many positive relationships, and does not have a social history suggestive of a personality disorder.

[polldaddy:11818926]

The author’s observations

Many women report worsening of mood during the premenstrual period (luteal phase). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) involves symptoms that develop during the luteal phase and end shortly after menstruation; this condition impacts ≤5% of women.1 The etiology of PMDD appears to involve contributions from genetics, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, allopregnanolone (a progesterone metabolite), brain-derived neurotrophic factor, brain structural and functional differences, and hypothalamic pathways.2

Researchers have postulated that the precipitous decline in the levels of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the luteal phase may contribute to the mood symptoms of PMDD.2 Allopregnanolone is a modulator of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptors and may exert anxiolytic and sedative effects. Women who experience PMDD may be less sensitive to the effects of allopregnanolone.3 Additionally, early luteal phase levels of estrogen may predict late luteal phase symptoms of PMDD.4 The mechanism involved may be estrogen’s effect on the serotonin system. The HPA axis may also be involved in the etiology of PMDD because patients with this condition appear to have a blunted cortisol response in reaction to stress.5 Research also has implicated immune activation and inflammation in the etiology of PMDD.6

A PMDD diagnosis should be distinguished from a premenstrual exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric condition, which occurs when a patient has an untreated primary mood or anxiety disorder that worsens during the premenstrual period. PMDD is differentiated from premenstrual syndrome by the severity of symptoms.2 The recommended first-line treatment of PMDD is an SSRI, but if an SSRI does not work, is not tolerated, or is not preferred for any other reason, recommended alternatives include combined hormone oral contraceptive pills, dutasteride, gabapentin, or various supplements.7,8 PMDD has been widely studied and is treated by both psychiatrists and gynecologists. In addition, some women report experiencing mood instability around ovulation. Kiesner9 found that 13% of women studied showed an increased negative mood state midcycle, rather than during the premenstrual period.

Continue to: Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual syndrome

Postmenstrual mood symptoms are atypical. Postmenstrual syndrome is not listed in DSM-5 or formally recognized as a medical diagnosis. Peer-reviewed research or literature on the condition is scarce to nonexistent. However, it has been discussed by physicians in articles in the lay press. One gynecologist and reproductive endocrinologist estimated that approximately 10% of women experience significant physical and emotional symptoms postmenstruation.10 An internist and women’s health specialist suggested that the cause of postmenstrual syndrome might be a surge in levels of estrogen and testosterone and may be associated with insulin resistance and polycystic ovarian syndrome, while another possible contribution could be iron deficiency caused by loss of blood from menstruation.11

TREATMENT Recommending an oral contraceptive

Ms. C’s psychiatrist does not prescribe an SSRI because he is concerned it would destabilize her BD II. The patient also had negative experiences in her past 2 trials of SSRIs.

Because the psychiatrist believes it is prudent to optimize the dosages of a patient’s current medication before starting a new medication or intervention, he considers increasing Ms. C’s dosage of lurasidone or pregabalin. The rationale for optimizing Ms. C’s current medication regimen is that greater overall mood stability would likely result in less severe postmenstrual mood symptoms. However, Ms. C does not want to increase her dosage of either medication because she is concerned about adverse effects.

Ms. C’s psychiatrist discusses the case with 2 gynecologist/obstetrician colleagues. One suggests the patient try a progesterone-only oral contraceptive and the other suggests a trial of Prometrium (a progesterone capsule used to treat endometrial hyperplasia and secondary amenorrhea). Both suggestions are based on the theory that Ms. C may be sensitive to levels of progesterone, which are low during the follicular phase and rise after ovulation; neither recommendation is evidence-based. A low level of allopregnanolone may lead to less GABAergic activity and consequently greater mood dysregulation. Some women are particularly sensitive to low levels of allopregnanolone in the follicular phase, which might lead to postmenstrual mood symptoms. Additionally, Ms. C’s previous treatment with a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive may have decreased her level of allopregnanolone.12 Ultimately, Ms. C’s psychiatrist suggests that she take a progesterone-only oral contraceptive.

The author’s observations

Guidance on how to treat Ms. C’s postmenstrual symptoms came from research on how to treat PMDD in patients who have BD. In a review of managing PMDD in women with BD, Sepede et al13 presented a treatment algorithm that recommends a combined estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive as first-line treatment in euthymic patients who are already receiving an optimal dose of mood stabilizers. Sepede et al13 expressed caution about using SSRIs due to the risk of inducing mood changes, but recommended SSRIs for patients with comorbid PMDD and BD who experience a depressive episode.

Another question is which type of oral contraceptive is most effective for treating PMDD. The combined oral contraceptive drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol has the most evidence for efficacy.14 Combined oral contraceptives carry risks of venous thromboembolism, hypertension, stroke, migraines, and liver complications, and are possibly associated with certain types of cancer, such as breast and cervical cancer.15 Their use is contraindicated in patients with a history of these conditions and for women age >35 who smoke ≥15 cigarettes/d.

The limited research that has examined the efficacy of progestin-only oral contraceptives for treating PMDD has been inconclusive.16 However, progesterone-only oral contraceptives are associated with less overall risk than combined oral contraceptives, and many women opt to use progesterone-only oral contraceptives due to concerns about possible adverse effects of the combined formulations. A substantial drawback of progesterone-only oral contraceptives is they must be taken at the same time every day, and if a dose is taken late, these agents may lose their efficacy in preventing pregnancy (and a backup birth control method must be used17). Additionally, drospirenone, a progestin that is a component of many oral contraceptives, has antimineralocorticoid properties and is contraindicated in patients with kidney or adrenal gland insufficiency or liver disease. As was the case when Ms. C initially took a combined contraceptive, hormonal contraceptives can sometimes cause mood dysregulation.

Continue to: OUTCOME Improved symptoms

OUTCOME Improved symptoms

Ms. C meets with her gynecologist, who prescribes norethindrone, a progestin-only oral contraceptive. Since taking norethindrone, Ms. C reports a dramatic improvement in the mood symptoms she experiences during the postmenstrual period.

Bottom Line

Some women may experience mood symptoms during the postmenstrual period that are similar to the symptoms experienced by patients who have premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). This phenomenon has been described as postmenstrual syndrome, and though evidence is lacking, treating it similarly to PMDD may be effective.

Related Resources

- Ray P, Mandal N, Sinha VK. Change of symptoms of schizophrenia across phases of menstrual cycle. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(1):113-122. doi:10.1007/s00737-019-0952-4

- Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

Drug Brand Names

Drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol • Yasmin

Dutasteride • Avodart

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Progesterone • Prometrium

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

2. Raffi ER, Freeman MP. The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):20-28.

3. Timby E, Bäckström T, Nyberg S, et al. Women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have altered sensitivity to allopregnanolone over the menstrual cycle compared to controls--a pilot study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(11):2109-2117.

4. Yen JY, Lin HC, Lin PC, et al. Early- and late-luteal-phase estrogen and progesterone levels of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4352.

5. Huang Y, Zhou R, Wu M, et al. Premenstrual syndrome is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to the TSST. Stress. 2015;18(2):160-168.

6. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(11):87.

7. Tiranini L, Nappi RE. Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Faculty Rev. 2022:11:(11). doi:10.12703/r/11-11

8. Raffi ER. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9). Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/145089/somatic-disorders/premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder

9. Kiesner J. One woman’s low is another woman’s high: paradoxical effects of the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(1):68-76.

10. Alnuweiri T. Feel low after your period? Postmenstrual syndrome could be the reason. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.wellandgood.com/pms-after-period/

11. Sharkey L. Everything you need to know about post-menstrual syndrome. Healthline. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.healthline.com/health/post-menstrual-syndrome

12. Santoru F, Berretti R, Locci A, et al. Decreased allopregnanolone induced by hormonal contraceptives is associated with a reduction in social behavior and sexual motivation in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3351-3364.

13. Sepede G, Brunetti M, Di Giannantonio M. Comorbid premenstrual dysphoric disorder in women with bipolar disorder: management challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment. 2020;16:415-426.

14. Rapkin AJ, Korotkaya Y, Taylor KC. Contraception counseling for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): current perspectives. Open Access J Contraception. 2019;10:27-39. doi:10.2147/OAJC.S183193

15. Roe AH, Bartz DA, Douglas PS. Combined estrogen-progestin contraception: side effects and health concerns. UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/combined-estrogen-progestin-contraception-side-effects-and-health-concerns

16. Ford O, Lethaby A, Roberts H, et al. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2012;3:CD003415. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003415.pub4

17. Kaunitz AM. Contraception: progestin-only pills (POPs). UpToDate. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/contraception-progestin-only-pills-pops

CASE Increased anxiety and depression

Ms. C, age 29, has bipolar II disorder (BD II) and generalized anxiety disorder. She presents to her outpatient psychiatrist seeking relief from chronic and significant dips in her mood from Day 5 to Day 15 of her menstrual cycle. During this time, she says she experiences increased anxiety, insomnia, frequent tearfulness, and intermittent suicidal ideation.

Ms. C meticulously charts her menstrual cycle using a smartphone app and reports having a regular 28-day cycle. She says she has experienced this worsening of symptoms since the onset of menarche, but her mood generally stabilizes after Day 14 of her cycle–around the time of ovulation–and remains euthymic throughout the premenstrual period.

HISTORY Depression and a change in medication