User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Supreme Court appears ready to overturn Roe

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

Commentary: WHO, UNICEF warn about increased risk of measles outbreaks

The newly released global estimate is now 25 million children (2 million more than in 2020) missing scheduled vaccines. This continues to bode badly for multiple vaccine-preventable infections, but maybe the most for measles in 2022.

Specifically for measles vaccine, global two-dose coverage was only 71%. Coverage was less than 50% in 8 countries: Chad, Guinea, Samoa, North Korea, Central African Republic, Somalia, Angola, and South Sudan. These eight areas seem ripe for outbreaks this year and indeed Somalia is having an outbreak.

Overall, worldwide measles cases increased 79% in early 2022, compared with 2021. The top 10 countries for measles cases from November 2021 to April 2022, per the World Health Organization, include Nigeria, India, Soma Ethiopia, Pakistan, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Liberia, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast.

In the United States, we have been lucky so far with only 55 cases since the start of 2021. However, MMR two-dose coverage has dropped since the pandemic’s start. The list of U.S. areas with the lowest overall two-dose MMR coverage as of 2021 were D.C. (78.9%), Houston (93.7%), Idaho (86.5%), Wisconsin (87.2%), Maryland (87.6%), Georgia (88.5%), Kentucky (88.9%), Ohio (89.6%), and Minnesota (89.8%). Only 14 states had rates over the targeted 95% rate needed for community (herd) immunity against measles (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:561-8).

Two bits of good news are that there seems to be some catch-up occurring in vaccine uptake overall (including MMR) and we now have two MMR suppliers in the United States since GlaxoSmithKline’s MMR was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for persons over 1 year of age. Let’s all redouble our efforts at adding to the catch-up efforts.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

The newly released global estimate is now 25 million children (2 million more than in 2020) missing scheduled vaccines. This continues to bode badly for multiple vaccine-preventable infections, but maybe the most for measles in 2022.

Specifically for measles vaccine, global two-dose coverage was only 71%. Coverage was less than 50% in 8 countries: Chad, Guinea, Samoa, North Korea, Central African Republic, Somalia, Angola, and South Sudan. These eight areas seem ripe for outbreaks this year and indeed Somalia is having an outbreak.

Overall, worldwide measles cases increased 79% in early 2022, compared with 2021. The top 10 countries for measles cases from November 2021 to April 2022, per the World Health Organization, include Nigeria, India, Soma Ethiopia, Pakistan, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Liberia, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast.

In the United States, we have been lucky so far with only 55 cases since the start of 2021. However, MMR two-dose coverage has dropped since the pandemic’s start. The list of U.S. areas with the lowest overall two-dose MMR coverage as of 2021 were D.C. (78.9%), Houston (93.7%), Idaho (86.5%), Wisconsin (87.2%), Maryland (87.6%), Georgia (88.5%), Kentucky (88.9%), Ohio (89.6%), and Minnesota (89.8%). Only 14 states had rates over the targeted 95% rate needed for community (herd) immunity against measles (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:561-8).

Two bits of good news are that there seems to be some catch-up occurring in vaccine uptake overall (including MMR) and we now have two MMR suppliers in the United States since GlaxoSmithKline’s MMR was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for persons over 1 year of age. Let’s all redouble our efforts at adding to the catch-up efforts.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

The newly released global estimate is now 25 million children (2 million more than in 2020) missing scheduled vaccines. This continues to bode badly for multiple vaccine-preventable infections, but maybe the most for measles in 2022.

Specifically for measles vaccine, global two-dose coverage was only 71%. Coverage was less than 50% in 8 countries: Chad, Guinea, Samoa, North Korea, Central African Republic, Somalia, Angola, and South Sudan. These eight areas seem ripe for outbreaks this year and indeed Somalia is having an outbreak.

Overall, worldwide measles cases increased 79% in early 2022, compared with 2021. The top 10 countries for measles cases from November 2021 to April 2022, per the World Health Organization, include Nigeria, India, Soma Ethiopia, Pakistan, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Liberia, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast.

In the United States, we have been lucky so far with only 55 cases since the start of 2021. However, MMR two-dose coverage has dropped since the pandemic’s start. The list of U.S. areas with the lowest overall two-dose MMR coverage as of 2021 were D.C. (78.9%), Houston (93.7%), Idaho (86.5%), Wisconsin (87.2%), Maryland (87.6%), Georgia (88.5%), Kentucky (88.9%), Ohio (89.6%), and Minnesota (89.8%). Only 14 states had rates over the targeted 95% rate needed for community (herd) immunity against measles (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:561-8).

Two bits of good news are that there seems to be some catch-up occurring in vaccine uptake overall (including MMR) and we now have two MMR suppliers in the United States since GlaxoSmithKline’s MMR was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for persons over 1 year of age. Let’s all redouble our efforts at adding to the catch-up efforts.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

Cases of hepatitis of unknown origin in children raise alarm

After several cases of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children in the United Kingdom were reported, further cases have now been reported in France (two cases), Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Spain. More than 80 cases have been reported overall, raising fears of an epidemic, according to a press release from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Furthermore, nine cases have allegedly been reported since last autumn in Alabama in the United States. These cases have mainly been in children aged 1-6 years.

Investigations are ongoing in all these countries, particularly as the “exact causes of these cases of acute hepatitis remain unknown.” Nevertheless, the team working on these cases in the United Kingdom believes that, based on clinical and epidemiologic data, the cause is probably infectious in origin.

Coordinated by the ECDC, European medical societies such as the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) are working together to promote information sharing, according to the European agency.

Potential infectious agent

For context, on April 5, the United Kingdom reported about 10 cases of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children younger than 10 in Scotland with no underlying conditions. Seven days later, the UK reported that 61 additional cases were under investigation in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the majority of which were in children aged 2-5 years.

The cases in the United Kingdom presented with severe acute hepatitis, with increased liver enzyme levels (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT] levels above 500 IU/L), and most presented with jaundice. Some reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting in the previous weeks.

The majority had no fever.

Although no deaths had been reported at press time, some cases needed to be seen by a liver specialist in the hospital, and others had to undergo transplantation (six transplants in Europe and two in the United States).

Initial hypotheses have focused on a potential infectious agent or exposure to a toxin. No link to COVID-19 vaccination has been established.

Which type of hepatitis?

The ECDC reports that laboratory tests have ruled out the possibility of attributing the cases to type A, B, C, D, and E viral hepatitis. Of the 13 cases in Scotland, 3 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 5 were negative, and 2 had contracted COVID-19 over the course of the last 3 months.

One positive test for adenovirus was found in 5 of the 13 Scottish cases, out of the 11 that were tested. All the cases reported in the United States tested positive for an adenovirus, five of which were for adenovirus type 41, which is responsible for inflammation of the bowel. Investigations are ongoing to assess any possible involvement of this virus in other cases. It should be noted that adenoviruses can cause hepatitis in children, but generally only in those who are immunosuppressed.

The pandemic could be another possible explanation, Nancy Reau, MD, head of the hepatology department at Rush University, Chicago, told this news organization. “The possibility that these cases are linked to COVID still exists,” she said. Some cases in the United Kingdom tested positive for COVID-19; none of these children had received the COVID-19 vaccine.

“COVID has been regularly seen to raise liver markers. It has also been shown to affect organs other than the lungs,” she stated. “It could be the case that, as it evolves, this virus has the potential to cause hepatitis in children.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After several cases of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children in the United Kingdom were reported, further cases have now been reported in France (two cases), Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Spain. More than 80 cases have been reported overall, raising fears of an epidemic, according to a press release from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Furthermore, nine cases have allegedly been reported since last autumn in Alabama in the United States. These cases have mainly been in children aged 1-6 years.

Investigations are ongoing in all these countries, particularly as the “exact causes of these cases of acute hepatitis remain unknown.” Nevertheless, the team working on these cases in the United Kingdom believes that, based on clinical and epidemiologic data, the cause is probably infectious in origin.

Coordinated by the ECDC, European medical societies such as the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) are working together to promote information sharing, according to the European agency.

Potential infectious agent

For context, on April 5, the United Kingdom reported about 10 cases of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children younger than 10 in Scotland with no underlying conditions. Seven days later, the UK reported that 61 additional cases were under investigation in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the majority of which were in children aged 2-5 years.

The cases in the United Kingdom presented with severe acute hepatitis, with increased liver enzyme levels (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT] levels above 500 IU/L), and most presented with jaundice. Some reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting in the previous weeks.

The majority had no fever.

Although no deaths had been reported at press time, some cases needed to be seen by a liver specialist in the hospital, and others had to undergo transplantation (six transplants in Europe and two in the United States).

Initial hypotheses have focused on a potential infectious agent or exposure to a toxin. No link to COVID-19 vaccination has been established.

Which type of hepatitis?

The ECDC reports that laboratory tests have ruled out the possibility of attributing the cases to type A, B, C, D, and E viral hepatitis. Of the 13 cases in Scotland, 3 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 5 were negative, and 2 had contracted COVID-19 over the course of the last 3 months.

One positive test for adenovirus was found in 5 of the 13 Scottish cases, out of the 11 that were tested. All the cases reported in the United States tested positive for an adenovirus, five of which were for adenovirus type 41, which is responsible for inflammation of the bowel. Investigations are ongoing to assess any possible involvement of this virus in other cases. It should be noted that adenoviruses can cause hepatitis in children, but generally only in those who are immunosuppressed.

The pandemic could be another possible explanation, Nancy Reau, MD, head of the hepatology department at Rush University, Chicago, told this news organization. “The possibility that these cases are linked to COVID still exists,” she said. Some cases in the United Kingdom tested positive for COVID-19; none of these children had received the COVID-19 vaccine.

“COVID has been regularly seen to raise liver markers. It has also been shown to affect organs other than the lungs,” she stated. “It could be the case that, as it evolves, this virus has the potential to cause hepatitis in children.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After several cases of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children in the United Kingdom were reported, further cases have now been reported in France (two cases), Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Spain. More than 80 cases have been reported overall, raising fears of an epidemic, according to a press release from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Furthermore, nine cases have allegedly been reported since last autumn in Alabama in the United States. These cases have mainly been in children aged 1-6 years.

Investigations are ongoing in all these countries, particularly as the “exact causes of these cases of acute hepatitis remain unknown.” Nevertheless, the team working on these cases in the United Kingdom believes that, based on clinical and epidemiologic data, the cause is probably infectious in origin.

Coordinated by the ECDC, European medical societies such as the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) are working together to promote information sharing, according to the European agency.

Potential infectious agent

For context, on April 5, the United Kingdom reported about 10 cases of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children younger than 10 in Scotland with no underlying conditions. Seven days later, the UK reported that 61 additional cases were under investigation in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the majority of which were in children aged 2-5 years.

The cases in the United Kingdom presented with severe acute hepatitis, with increased liver enzyme levels (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT] levels above 500 IU/L), and most presented with jaundice. Some reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting in the previous weeks.

The majority had no fever.

Although no deaths had been reported at press time, some cases needed to be seen by a liver specialist in the hospital, and others had to undergo transplantation (six transplants in Europe and two in the United States).

Initial hypotheses have focused on a potential infectious agent or exposure to a toxin. No link to COVID-19 vaccination has been established.

Which type of hepatitis?

The ECDC reports that laboratory tests have ruled out the possibility of attributing the cases to type A, B, C, D, and E viral hepatitis. Of the 13 cases in Scotland, 3 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 5 were negative, and 2 had contracted COVID-19 over the course of the last 3 months.

One positive test for adenovirus was found in 5 of the 13 Scottish cases, out of the 11 that were tested. All the cases reported in the United States tested positive for an adenovirus, five of which were for adenovirus type 41, which is responsible for inflammation of the bowel. Investigations are ongoing to assess any possible involvement of this virus in other cases. It should be noted that adenoviruses can cause hepatitis in children, but generally only in those who are immunosuppressed.

The pandemic could be another possible explanation, Nancy Reau, MD, head of the hepatology department at Rush University, Chicago, told this news organization. “The possibility that these cases are linked to COVID still exists,” she said. Some cases in the United Kingdom tested positive for COVID-19; none of these children had received the COVID-19 vaccine.

“COVID has been regularly seen to raise liver markers. It has also been shown to affect organs other than the lungs,” she stated. “It could be the case that, as it evolves, this virus has the potential to cause hepatitis in children.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vegetarian diet as good for children, with slight risk of underweight

With more families placing their children on vegetarian diets, the results from a Canadian longitudinal cohort study are reassuring: It found no clinically meaningful differences in height, growth, or biochemical measures of nutrition in young children on vegetarian and nonvegetarian diets.

While z scores (the standard deviation above or below the mean) were similar in both dietary groups, there was a weak association between a vegetarian diet and lower mean z height, as well as slightly higher odds of underweight.

No significant associations were identified between vegetarian and nonvegetarian diets for child z body mass index (BMI), serum ferritin, 25(OH)D, and serum lipids, according to Jonathon L. Maguire, MD. MSc, of St. Michael’s Hospital Pediatric Clinic in Toronto.

Moreover, the magnitude of the height and vegetarian diet association was small at just 0.3 cm for a 3-year-old child and unlikely to be clinically meaningful, Dr. Maguire and colleagues wrote online in Pediatrics.

In a secondary study outcome, cow’s milk consumption was associated with higher serum lipid levels for both diets. Serum lipids were similar among those who did or did not consume a vegetarian diet and consumed the recommended 2 cups of cow’s milk per day.

“The vast majority of children with vegetarian diets have similar growth and nutrition as children without vegetarian diets,” said Dr. Maguire, who is also a professor of pediatrics and nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto, in an interview. “But, I think we should be mindful to carefully plan vegetarian diets for children [who are] underweight.”

The study conclusion was based on 8,907 children, 6 months to 8 years of age, including 248 vegetarian and 25 vegan children, at baseline. They were part of theTARGet Kids! practice-based research network in Toronto.

The mean age of children at baseline was 2.2 years (standard deviation, 1.5), and 52.4% were male. Participants were followed for an average of 2.8 years (SD, 1.7).

Those with a vegetarian diet had longer breastfeeding duration: 12.6 months (SD, 9.5) versus 10.0 months (SD, 7.0). They were also more likely to be of Asian ethnicity: 33.8% versus 19.0%. Otherwise, children with and without a vegetarian diet were similar at baseline.

In study outcomes, vegetarian children had higher odds of underweight: body mass index z score less than –2 (odds ratio 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 1.19-2.96, P = .007), while no association with overweight or obesity was found.

In a secondary outcome, cow’s milk consumption was associated with higher levels of non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .03), total cholesterol (P = .04), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .02) in young children on a vegetarian diet. Levels were similar in children with and without a vegetarian diet who consumed the recommended 2 cups of cow’s milk per day.

Previous studies have found that vegetarian children have normal growth and development but tend to be leaner than their omnivore peers.

As for the potential effect of following a fully vegan diet on these nutritional measures, Dr. Maguire said, “Unfortunately, there were not enough children with vegan diets to make meaningful conclusions.”

Would results likely be similar in older children who have more independence and engage more with their peers?“ I don’t know, but we will be following these children for many years to come through the TARGet Kids! research network, Dr. Maguire said.

Studies such as this are timely as plant-based eating becomes more widespread in the United States. The 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys found that 2.1% of American adults followed a vegetarian diet, and that figure appears to have increased, with 5% of American adults self-identifying as vegetarian in a 2019 Gallup poll.

Offering her perspective on the Canadian study but not involved in it, Stephanie Di Figlia-Peck, MS, RDN, agreed the results indicate that “a vegetarian diet is not a negative thing for growth and development.” She is a lead registered dietitian in the division of adolescent medicine at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y. She noted, however, that the study looked only at very young children on average.

She stressed that vegetarian regimens require family commitment and agreed on the need for planning. “For these diets to work, a lot has to go into it. But if they’re carefully planned, there is adequate protein and micro- and macronutrients and there’s a nonnegative effect on growth and development.”

The study results mirror what she sees in clinical practice, with vegetarian children tending to weigh less. “Some obese and overweight children will adopt vegetarian diets to lose weight,” Ms. Di Figlia-Peck said.

And perseverance has rewards. “When people follow a vegetarian diet, they tend to have lower blood pressure and cholesterol. A plant-based diet can favorably impact diseases for an entire lifetime.”

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the St. Michael’s Hospital and SickKids Hospital foundations. Dr. Maguire received an unrestricted research grant for a previous investigator-initiated study from Dairy Farmers of Canada, and D drops provided nonfinancial support (vitamin D supplements) for a previous investigator-initiated study on vitamin D and respiratory tract infections. Coauthor David Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, reported research support from multiple private-sector and nonprivate organizations; several of his family members are involved in the promotion of vegetarian diets. Ms. Di Figlia-Peck had no competing interests to declare.

With more families placing their children on vegetarian diets, the results from a Canadian longitudinal cohort study are reassuring: It found no clinically meaningful differences in height, growth, or biochemical measures of nutrition in young children on vegetarian and nonvegetarian diets.

While z scores (the standard deviation above or below the mean) were similar in both dietary groups, there was a weak association between a vegetarian diet and lower mean z height, as well as slightly higher odds of underweight.

No significant associations were identified between vegetarian and nonvegetarian diets for child z body mass index (BMI), serum ferritin, 25(OH)D, and serum lipids, according to Jonathon L. Maguire, MD. MSc, of St. Michael’s Hospital Pediatric Clinic in Toronto.

Moreover, the magnitude of the height and vegetarian diet association was small at just 0.3 cm for a 3-year-old child and unlikely to be clinically meaningful, Dr. Maguire and colleagues wrote online in Pediatrics.

In a secondary study outcome, cow’s milk consumption was associated with higher serum lipid levels for both diets. Serum lipids were similar among those who did or did not consume a vegetarian diet and consumed the recommended 2 cups of cow’s milk per day.

“The vast majority of children with vegetarian diets have similar growth and nutrition as children without vegetarian diets,” said Dr. Maguire, who is also a professor of pediatrics and nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto, in an interview. “But, I think we should be mindful to carefully plan vegetarian diets for children [who are] underweight.”

The study conclusion was based on 8,907 children, 6 months to 8 years of age, including 248 vegetarian and 25 vegan children, at baseline. They were part of theTARGet Kids! practice-based research network in Toronto.

The mean age of children at baseline was 2.2 years (standard deviation, 1.5), and 52.4% were male. Participants were followed for an average of 2.8 years (SD, 1.7).

Those with a vegetarian diet had longer breastfeeding duration: 12.6 months (SD, 9.5) versus 10.0 months (SD, 7.0). They were also more likely to be of Asian ethnicity: 33.8% versus 19.0%. Otherwise, children with and without a vegetarian diet were similar at baseline.

In study outcomes, vegetarian children had higher odds of underweight: body mass index z score less than –2 (odds ratio 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 1.19-2.96, P = .007), while no association with overweight or obesity was found.

In a secondary outcome, cow’s milk consumption was associated with higher levels of non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .03), total cholesterol (P = .04), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .02) in young children on a vegetarian diet. Levels were similar in children with and without a vegetarian diet who consumed the recommended 2 cups of cow’s milk per day.

Previous studies have found that vegetarian children have normal growth and development but tend to be leaner than their omnivore peers.

As for the potential effect of following a fully vegan diet on these nutritional measures, Dr. Maguire said, “Unfortunately, there were not enough children with vegan diets to make meaningful conclusions.”

Would results likely be similar in older children who have more independence and engage more with their peers?“ I don’t know, but we will be following these children for many years to come through the TARGet Kids! research network, Dr. Maguire said.

Studies such as this are timely as plant-based eating becomes more widespread in the United States. The 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys found that 2.1% of American adults followed a vegetarian diet, and that figure appears to have increased, with 5% of American adults self-identifying as vegetarian in a 2019 Gallup poll.

Offering her perspective on the Canadian study but not involved in it, Stephanie Di Figlia-Peck, MS, RDN, agreed the results indicate that “a vegetarian diet is not a negative thing for growth and development.” She is a lead registered dietitian in the division of adolescent medicine at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y. She noted, however, that the study looked only at very young children on average.

She stressed that vegetarian regimens require family commitment and agreed on the need for planning. “For these diets to work, a lot has to go into it. But if they’re carefully planned, there is adequate protein and micro- and macronutrients and there’s a nonnegative effect on growth and development.”

The study results mirror what she sees in clinical practice, with vegetarian children tending to weigh less. “Some obese and overweight children will adopt vegetarian diets to lose weight,” Ms. Di Figlia-Peck said.

And perseverance has rewards. “When people follow a vegetarian diet, they tend to have lower blood pressure and cholesterol. A plant-based diet can favorably impact diseases for an entire lifetime.”

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the St. Michael’s Hospital and SickKids Hospital foundations. Dr. Maguire received an unrestricted research grant for a previous investigator-initiated study from Dairy Farmers of Canada, and D drops provided nonfinancial support (vitamin D supplements) for a previous investigator-initiated study on vitamin D and respiratory tract infections. Coauthor David Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, reported research support from multiple private-sector and nonprivate organizations; several of his family members are involved in the promotion of vegetarian diets. Ms. Di Figlia-Peck had no competing interests to declare.

With more families placing their children on vegetarian diets, the results from a Canadian longitudinal cohort study are reassuring: It found no clinically meaningful differences in height, growth, or biochemical measures of nutrition in young children on vegetarian and nonvegetarian diets.

While z scores (the standard deviation above or below the mean) were similar in both dietary groups, there was a weak association between a vegetarian diet and lower mean z height, as well as slightly higher odds of underweight.

No significant associations were identified between vegetarian and nonvegetarian diets for child z body mass index (BMI), serum ferritin, 25(OH)D, and serum lipids, according to Jonathon L. Maguire, MD. MSc, of St. Michael’s Hospital Pediatric Clinic in Toronto.

Moreover, the magnitude of the height and vegetarian diet association was small at just 0.3 cm for a 3-year-old child and unlikely to be clinically meaningful, Dr. Maguire and colleagues wrote online in Pediatrics.

In a secondary study outcome, cow’s milk consumption was associated with higher serum lipid levels for both diets. Serum lipids were similar among those who did or did not consume a vegetarian diet and consumed the recommended 2 cups of cow’s milk per day.

“The vast majority of children with vegetarian diets have similar growth and nutrition as children without vegetarian diets,” said Dr. Maguire, who is also a professor of pediatrics and nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto, in an interview. “But, I think we should be mindful to carefully plan vegetarian diets for children [who are] underweight.”

The study conclusion was based on 8,907 children, 6 months to 8 years of age, including 248 vegetarian and 25 vegan children, at baseline. They were part of theTARGet Kids! practice-based research network in Toronto.

The mean age of children at baseline was 2.2 years (standard deviation, 1.5), and 52.4% were male. Participants were followed for an average of 2.8 years (SD, 1.7).

Those with a vegetarian diet had longer breastfeeding duration: 12.6 months (SD, 9.5) versus 10.0 months (SD, 7.0). They were also more likely to be of Asian ethnicity: 33.8% versus 19.0%. Otherwise, children with and without a vegetarian diet were similar at baseline.

In study outcomes, vegetarian children had higher odds of underweight: body mass index z score less than –2 (odds ratio 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 1.19-2.96, P = .007), while no association with overweight or obesity was found.

In a secondary outcome, cow’s milk consumption was associated with higher levels of non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .03), total cholesterol (P = .04), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P = .02) in young children on a vegetarian diet. Levels were similar in children with and without a vegetarian diet who consumed the recommended 2 cups of cow’s milk per day.

Previous studies have found that vegetarian children have normal growth and development but tend to be leaner than their omnivore peers.

As for the potential effect of following a fully vegan diet on these nutritional measures, Dr. Maguire said, “Unfortunately, there were not enough children with vegan diets to make meaningful conclusions.”

Would results likely be similar in older children who have more independence and engage more with their peers?“ I don’t know, but we will be following these children for many years to come through the TARGet Kids! research network, Dr. Maguire said.

Studies such as this are timely as plant-based eating becomes more widespread in the United States. The 2007-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys found that 2.1% of American adults followed a vegetarian diet, and that figure appears to have increased, with 5% of American adults self-identifying as vegetarian in a 2019 Gallup poll.

Offering her perspective on the Canadian study but not involved in it, Stephanie Di Figlia-Peck, MS, RDN, agreed the results indicate that “a vegetarian diet is not a negative thing for growth and development.” She is a lead registered dietitian in the division of adolescent medicine at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y. She noted, however, that the study looked only at very young children on average.

She stressed that vegetarian regimens require family commitment and agreed on the need for planning. “For these diets to work, a lot has to go into it. But if they’re carefully planned, there is adequate protein and micro- and macronutrients and there’s a nonnegative effect on growth and development.”

The study results mirror what she sees in clinical practice, with vegetarian children tending to weigh less. “Some obese and overweight children will adopt vegetarian diets to lose weight,” Ms. Di Figlia-Peck said.

And perseverance has rewards. “When people follow a vegetarian diet, they tend to have lower blood pressure and cholesterol. A plant-based diet can favorably impact diseases for an entire lifetime.”

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the St. Michael’s Hospital and SickKids Hospital foundations. Dr. Maguire received an unrestricted research grant for a previous investigator-initiated study from Dairy Farmers of Canada, and D drops provided nonfinancial support (vitamin D supplements) for a previous investigator-initiated study on vitamin D and respiratory tract infections. Coauthor David Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, reported research support from multiple private-sector and nonprivate organizations; several of his family members are involved in the promotion of vegetarian diets. Ms. Di Figlia-Peck had no competing interests to declare.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Commentary: Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

This study of antibiotic use in the first 2 years of life in a reasonably standardized primary care office raises issues about antibiotic stewardship that can be the basis for counseling against antibiotics for viral infections or mild uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) above 6 months of age. Even unintended and previously undescribed downstream effects of antibiotics should play a role in our decisions and are another nudge toward prudent antibiotic use – for example, watchful waiting (WW) for AOM.

Some families ask for antibiotics for almost any infection while others may want antibiotics only if really necessary. But maybe patient family wishes are not the main driver, considering a report in Pediatrics (2022;150[1]:e2021055613). They analyzed over 2 million AOM episodes from billing/enrollment records from the MarketScan commercial claims research databases. They reported that, despite WW being the management of choice per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for uncomplicated AOM in children over 1 year of age, WW use had not increased between 2015 and 2019. Further, they noted that WW was not related to patient factors or demographics but was associated with specialty and provider. For example, WW use was five times more likely by otolaryngologists than pediatricians and less likely by nonpediatricians than pediatricians. Further, some clinicians used WW a lot, while others almost not at all (high-volume antibiotic prescribers). Of note, having a fever significantly lowered the chance of WW.

Maturing data on antibiotic-related alterations in species distribution and quantity within children’s microbiome plus potential effects on antibody responses to vaccines are ideas families need to hear. I suggest sharing these as part of anticipatory guidance at well-child checks as early in life as is feasible.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

This study of antibiotic use in the first 2 years of life in a reasonably standardized primary care office raises issues about antibiotic stewardship that can be the basis for counseling against antibiotics for viral infections or mild uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) above 6 months of age. Even unintended and previously undescribed downstream effects of antibiotics should play a role in our decisions and are another nudge toward prudent antibiotic use – for example, watchful waiting (WW) for AOM.

Some families ask for antibiotics for almost any infection while others may want antibiotics only if really necessary. But maybe patient family wishes are not the main driver, considering a report in Pediatrics (2022;150[1]:e2021055613). They analyzed over 2 million AOM episodes from billing/enrollment records from the MarketScan commercial claims research databases. They reported that, despite WW being the management of choice per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for uncomplicated AOM in children over 1 year of age, WW use had not increased between 2015 and 2019. Further, they noted that WW was not related to patient factors or demographics but was associated with specialty and provider. For example, WW use was five times more likely by otolaryngologists than pediatricians and less likely by nonpediatricians than pediatricians. Further, some clinicians used WW a lot, while others almost not at all (high-volume antibiotic prescribers). Of note, having a fever significantly lowered the chance of WW.

Maturing data on antibiotic-related alterations in species distribution and quantity within children’s microbiome plus potential effects on antibody responses to vaccines are ideas families need to hear. I suggest sharing these as part of anticipatory guidance at well-child checks as early in life as is feasible.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

This study of antibiotic use in the first 2 years of life in a reasonably standardized primary care office raises issues about antibiotic stewardship that can be the basis for counseling against antibiotics for viral infections or mild uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) above 6 months of age. Even unintended and previously undescribed downstream effects of antibiotics should play a role in our decisions and are another nudge toward prudent antibiotic use – for example, watchful waiting (WW) for AOM.

Some families ask for antibiotics for almost any infection while others may want antibiotics only if really necessary. But maybe patient family wishes are not the main driver, considering a report in Pediatrics (2022;150[1]:e2021055613). They analyzed over 2 million AOM episodes from billing/enrollment records from the MarketScan commercial claims research databases. They reported that, despite WW being the management of choice per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for uncomplicated AOM in children over 1 year of age, WW use had not increased between 2015 and 2019. Further, they noted that WW was not related to patient factors or demographics but was associated with specialty and provider. For example, WW use was five times more likely by otolaryngologists than pediatricians and less likely by nonpediatricians than pediatricians. Further, some clinicians used WW a lot, while others almost not at all (high-volume antibiotic prescribers). Of note, having a fever significantly lowered the chance of WW.

Maturing data on antibiotic-related alterations in species distribution and quantity within children’s microbiome plus potential effects on antibody responses to vaccines are ideas families need to hear. I suggest sharing these as part of anticipatory guidance at well-child checks as early in life as is feasible.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

In this column I have previously discussed the microbiome and its importance to health, especially as it relates to infections in children. Given the appreciated connection between microbiome and immunity, my group in Rochester, N.Y., recently undertook a study of the effect of antibiotic usage on the immune response to routine early childhood vaccines. In mouse models, it was previously shown that antibiotic exposure induced a reduction in the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota that in turn negatively affected the generation and maintenance of vaccine-induced immunity.1,2 A study from Stanford University was the first experimental human trial of antibiotic effects on vaccine responses. Adult volunteers were given an antibiotic or not before seasonal influenza vaccination and the researchers identified specific bacteria in the gut that were reduced by the antibiotics given. Those normal bacteria in the gut microbiome were shown to provide positive immunity signals to the systemic immune system that potentiated vaccine responses.3

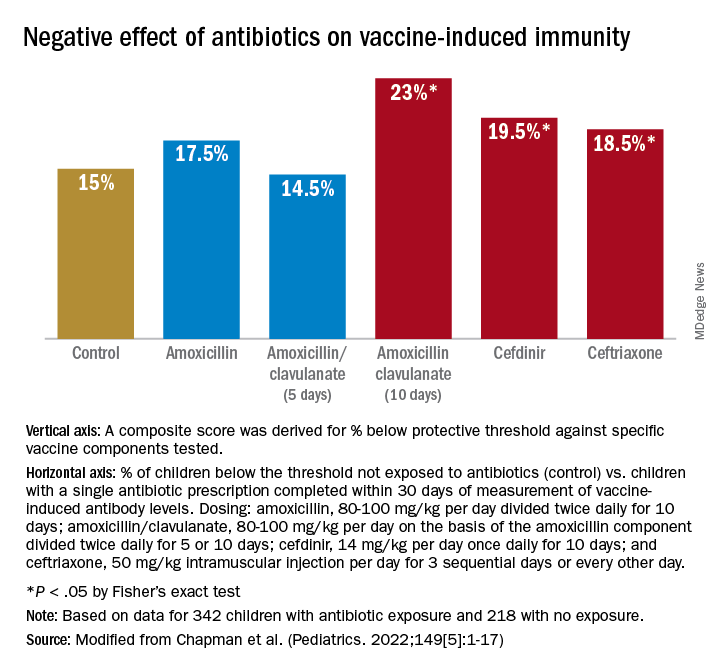

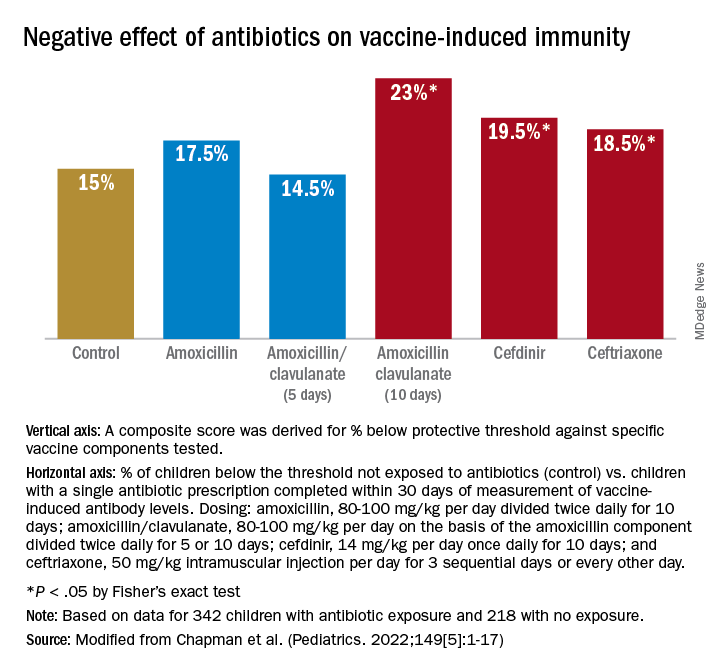

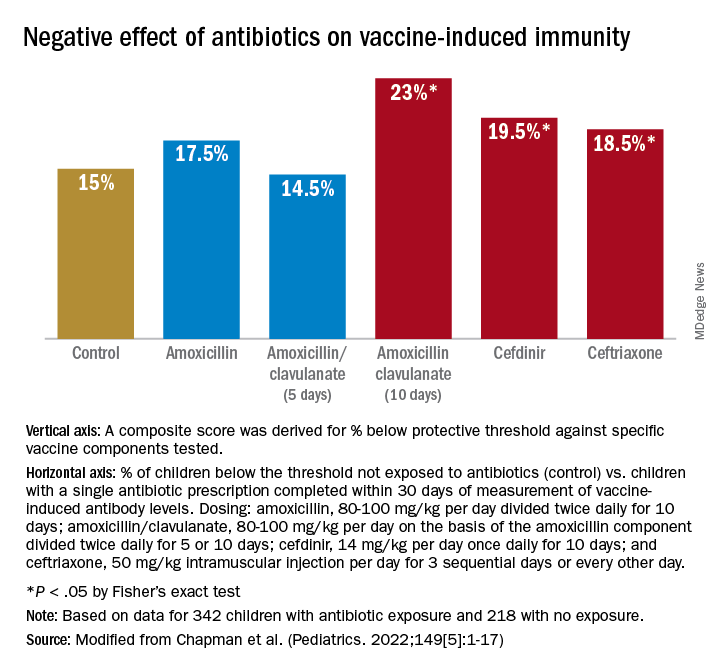

My group conducted the first-ever study in children to explore whether an association existed between antibiotic use and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the May issue of Pediatrics we report results from 560 children studied.4 From these children, 11,888 serum antibody levels to vaccine antigens were measured. Vaccine-induced antibody levels were determined at various time points after primary vaccination at child age 2, 4, and 6 months and boosters at age 12-18 months for 10 antigens included in four vaccines: DTaP, Hib, IPV, and PCV. The antibody levels to vaccine components were measured to DTaP (diphtheria toxoid, pertussis toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin), Hib conjugate (polyribosylribitol phosphate), IPV (polio 2), and PCV (serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). A total of 342 children with 1,678 antibiotic courses prescribed were compared with 218 children with no antibiotic exposures. The predominant antibiotics prescribed were amoxicillin, cefdinir, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and ceftriaxone, since most treatments were for acute otitis media.

Of possible high clinical relevance, we found that from 9 to 24 months of age, children with antibiotic exposure had a higher frequency of vaccine-induced antibody levels below protection compared with children with no antibiotic use, placing them at risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable infection for DTaP antigens DT, TT, and PT and for PCV serotype 14.

For time points where antibody levels were determined within 30 days of completion of a course of antibiotics (recent antibiotic use), individual antibiotics were analyzed for effect on antibody levels below protective levels. Across all vaccine antigens measured, we found that all antibiotics had a negative effect on antibody levels and percentage of children achieving the protective antibody level threshold. Amoxicillin use had a lower association with lower antibody levels than the broader spectrum antibiotics, amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin), cefdinir, and ceftriaxone. For children receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions, it was possible to compare the effect of shorter versus longer courses and we found that a 5-day course was associated with subprotective antibody levels similar to 10 days of amoxicillin, whereas 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate was associated with higher frequency of children having subprotective antibody levels (Figure).

We examined whether accumulation of antibiotic courses in the first year of life had an association with subsequent vaccine-induced antibody levels and found that each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in the median antibody level. For DTaP, each prescription was associated with 5.8% drop in antibody level to the vaccine components. For Hib the drop was 6.8%, IPV was 11.3%, and PCV was 10.4% – all statistically significant. To determine if booster vaccination influenced this association, a second analysis was performed using antibiotic prescriptions up to 15 months of age. We found each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in median vaccine-induced antibody levels for DTaP by 18%, Hib by 21%, IPV by 19%, and PCV by 12% – all statistically significant.

Our study is the first in young children during the early age window where vaccine-induced immunity is established. Antibiotic use was associated with increased frequency of subprotective antibody levels for several vaccines used in children up to 2 years of age. The lower antibody levels could leave children vulnerable to vaccine preventable diseases. Perhaps outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis, may be a consequence of multiple courses of antibiotics suppressing vaccine-induced immunity.

A goal of this study was to explore potential acute and long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on vaccine-induced antibody levels. Accumulated antibiotic courses up to booster immunization was associated with decreased vaccine antibody levels both before and after booster, suggesting that booster immunization was not sufficient to change the negative association with antibiotic exposure. The results were similar for all vaccines tested, suggesting that the specific vaccine formulation was not a factor.

The study has several limitations. The antibiotic prescription data and measurements of vaccine-induced antibody levels were recorded and measured prospectively; however, our analysis was done retrospectively. The group of study children was derived from my private practice in Rochester, N.Y., and may not be broadly representative of all children. The number of vaccine antibody measurements was limited by serum availability at some sampling time points in some children; and sometimes, the serum samples were collected far apart, which weakened our ability to perform longitudinal analyses. We did not collect stool samples from the children so we could not directly study the effect of antibiotic courses on the gut microbiome.

Our study adds new reasons to be cautious about overprescribing antibiotics on an individual child basis because an adverse effect extends to reduction in vaccine responses. This should be explained to parents requesting unnecessary antibiotics for colds and coughs. When antibiotics are necessary, the judicious choice of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic or a shorter duration of a broader spectrum antibiotic may reduce adverse effects on vaccine-induced immunity.

References

1. Valdez Y et al. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(11):526-37.

2. Lynn MA et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(5):653-60.e5.

3. Hagan T et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. 2019;178(6):1313-28.e13.

4. Chapman T et al. Antibiotic use and vaccine antibody levels. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5);1-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

In this column I have previously discussed the microbiome and its importance to health, especially as it relates to infections in children. Given the appreciated connection between microbiome and immunity, my group in Rochester, N.Y., recently undertook a study of the effect of antibiotic usage on the immune response to routine early childhood vaccines. In mouse models, it was previously shown that antibiotic exposure induced a reduction in the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota that in turn negatively affected the generation and maintenance of vaccine-induced immunity.1,2 A study from Stanford University was the first experimental human trial of antibiotic effects on vaccine responses. Adult volunteers were given an antibiotic or not before seasonal influenza vaccination and the researchers identified specific bacteria in the gut that were reduced by the antibiotics given. Those normal bacteria in the gut microbiome were shown to provide positive immunity signals to the systemic immune system that potentiated vaccine responses.3

My group conducted the first-ever study in children to explore whether an association existed between antibiotic use and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the May issue of Pediatrics we report results from 560 children studied.4 From these children, 11,888 serum antibody levels to vaccine antigens were measured. Vaccine-induced antibody levels were determined at various time points after primary vaccination at child age 2, 4, and 6 months and boosters at age 12-18 months for 10 antigens included in four vaccines: DTaP, Hib, IPV, and PCV. The antibody levels to vaccine components were measured to DTaP (diphtheria toxoid, pertussis toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin), Hib conjugate (polyribosylribitol phosphate), IPV (polio 2), and PCV (serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). A total of 342 children with 1,678 antibiotic courses prescribed were compared with 218 children with no antibiotic exposures. The predominant antibiotics prescribed were amoxicillin, cefdinir, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and ceftriaxone, since most treatments were for acute otitis media.

Of possible high clinical relevance, we found that from 9 to 24 months of age, children with antibiotic exposure had a higher frequency of vaccine-induced antibody levels below protection compared with children with no antibiotic use, placing them at risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable infection for DTaP antigens DT, TT, and PT and for PCV serotype 14.

For time points where antibody levels were determined within 30 days of completion of a course of antibiotics (recent antibiotic use), individual antibiotics were analyzed for effect on antibody levels below protective levels. Across all vaccine antigens measured, we found that all antibiotics had a negative effect on antibody levels and percentage of children achieving the protective antibody level threshold. Amoxicillin use had a lower association with lower antibody levels than the broader spectrum antibiotics, amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin), cefdinir, and ceftriaxone. For children receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions, it was possible to compare the effect of shorter versus longer courses and we found that a 5-day course was associated with subprotective antibody levels similar to 10 days of amoxicillin, whereas 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate was associated with higher frequency of children having subprotective antibody levels (Figure).

We examined whether accumulation of antibiotic courses in the first year of life had an association with subsequent vaccine-induced antibody levels and found that each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in the median antibody level. For DTaP, each prescription was associated with 5.8% drop in antibody level to the vaccine components. For Hib the drop was 6.8%, IPV was 11.3%, and PCV was 10.4% – all statistically significant. To determine if booster vaccination influenced this association, a second analysis was performed using antibiotic prescriptions up to 15 months of age. We found each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in median vaccine-induced antibody levels for DTaP by 18%, Hib by 21%, IPV by 19%, and PCV by 12% – all statistically significant.

Our study is the first in young children during the early age window where vaccine-induced immunity is established. Antibiotic use was associated with increased frequency of subprotective antibody levels for several vaccines used in children up to 2 years of age. The lower antibody levels could leave children vulnerable to vaccine preventable diseases. Perhaps outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis, may be a consequence of multiple courses of antibiotics suppressing vaccine-induced immunity.

A goal of this study was to explore potential acute and long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on vaccine-induced antibody levels. Accumulated antibiotic courses up to booster immunization was associated with decreased vaccine antibody levels both before and after booster, suggesting that booster immunization was not sufficient to change the negative association with antibiotic exposure. The results were similar for all vaccines tested, suggesting that the specific vaccine formulation was not a factor.

The study has several limitations. The antibiotic prescription data and measurements of vaccine-induced antibody levels were recorded and measured prospectively; however, our analysis was done retrospectively. The group of study children was derived from my private practice in Rochester, N.Y., and may not be broadly representative of all children. The number of vaccine antibody measurements was limited by serum availability at some sampling time points in some children; and sometimes, the serum samples were collected far apart, which weakened our ability to perform longitudinal analyses. We did not collect stool samples from the children so we could not directly study the effect of antibiotic courses on the gut microbiome.

Our study adds new reasons to be cautious about overprescribing antibiotics on an individual child basis because an adverse effect extends to reduction in vaccine responses. This should be explained to parents requesting unnecessary antibiotics for colds and coughs. When antibiotics are necessary, the judicious choice of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic or a shorter duration of a broader spectrum antibiotic may reduce adverse effects on vaccine-induced immunity.

References

1. Valdez Y et al. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(11):526-37.

2. Lynn MA et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(5):653-60.e5.

3. Hagan T et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. 2019;178(6):1313-28.e13.

4. Chapman T et al. Antibiotic use and vaccine antibody levels. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5);1-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

In this column I have previously discussed the microbiome and its importance to health, especially as it relates to infections in children. Given the appreciated connection between microbiome and immunity, my group in Rochester, N.Y., recently undertook a study of the effect of antibiotic usage on the immune response to routine early childhood vaccines. In mouse models, it was previously shown that antibiotic exposure induced a reduction in the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota that in turn negatively affected the generation and maintenance of vaccine-induced immunity.1,2 A study from Stanford University was the first experimental human trial of antibiotic effects on vaccine responses. Adult volunteers were given an antibiotic or not before seasonal influenza vaccination and the researchers identified specific bacteria in the gut that were reduced by the antibiotics given. Those normal bacteria in the gut microbiome were shown to provide positive immunity signals to the systemic immune system that potentiated vaccine responses.3

My group conducted the first-ever study in children to explore whether an association existed between antibiotic use and vaccine-induced antibody levels. In the May issue of Pediatrics we report results from 560 children studied.4 From these children, 11,888 serum antibody levels to vaccine antigens were measured. Vaccine-induced antibody levels were determined at various time points after primary vaccination at child age 2, 4, and 6 months and boosters at age 12-18 months for 10 antigens included in four vaccines: DTaP, Hib, IPV, and PCV. The antibody levels to vaccine components were measured to DTaP (diphtheria toxoid, pertussis toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin), Hib conjugate (polyribosylribitol phosphate), IPV (polio 2), and PCV (serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). A total of 342 children with 1,678 antibiotic courses prescribed were compared with 218 children with no antibiotic exposures. The predominant antibiotics prescribed were amoxicillin, cefdinir, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and ceftriaxone, since most treatments were for acute otitis media.

Of possible high clinical relevance, we found that from 9 to 24 months of age, children with antibiotic exposure had a higher frequency of vaccine-induced antibody levels below protection compared with children with no antibiotic use, placing them at risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable infection for DTaP antigens DT, TT, and PT and for PCV serotype 14.

For time points where antibody levels were determined within 30 days of completion of a course of antibiotics (recent antibiotic use), individual antibiotics were analyzed for effect on antibody levels below protective levels. Across all vaccine antigens measured, we found that all antibiotics had a negative effect on antibody levels and percentage of children achieving the protective antibody level threshold. Amoxicillin use had a lower association with lower antibody levels than the broader spectrum antibiotics, amoxicillin clavulanate (Augmentin), cefdinir, and ceftriaxone. For children receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate prescriptions, it was possible to compare the effect of shorter versus longer courses and we found that a 5-day course was associated with subprotective antibody levels similar to 10 days of amoxicillin, whereas 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate was associated with higher frequency of children having subprotective antibody levels (Figure).

We examined whether accumulation of antibiotic courses in the first year of life had an association with subsequent vaccine-induced antibody levels and found that each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in the median antibody level. For DTaP, each prescription was associated with 5.8% drop in antibody level to the vaccine components. For Hib the drop was 6.8%, IPV was 11.3%, and PCV was 10.4% – all statistically significant. To determine if booster vaccination influenced this association, a second analysis was performed using antibiotic prescriptions up to 15 months of age. We found each antibiotic prescription was associated with a reduction in median vaccine-induced antibody levels for DTaP by 18%, Hib by 21%, IPV by 19%, and PCV by 12% – all statistically significant.

Our study is the first in young children during the early age window where vaccine-induced immunity is established. Antibiotic use was associated with increased frequency of subprotective antibody levels for several vaccines used in children up to 2 years of age. The lower antibody levels could leave children vulnerable to vaccine preventable diseases. Perhaps outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as pertussis, may be a consequence of multiple courses of antibiotics suppressing vaccine-induced immunity.

A goal of this study was to explore potential acute and long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on vaccine-induced antibody levels. Accumulated antibiotic courses up to booster immunization was associated with decreased vaccine antibody levels both before and after booster, suggesting that booster immunization was not sufficient to change the negative association with antibiotic exposure. The results were similar for all vaccines tested, suggesting that the specific vaccine formulation was not a factor.

The study has several limitations. The antibiotic prescription data and measurements of vaccine-induced antibody levels were recorded and measured prospectively; however, our analysis was done retrospectively. The group of study children was derived from my private practice in Rochester, N.Y., and may not be broadly representative of all children. The number of vaccine antibody measurements was limited by serum availability at some sampling time points in some children; and sometimes, the serum samples were collected far apart, which weakened our ability to perform longitudinal analyses. We did not collect stool samples from the children so we could not directly study the effect of antibiotic courses on the gut microbiome.

Our study adds new reasons to be cautious about overprescribing antibiotics on an individual child basis because an adverse effect extends to reduction in vaccine responses. This should be explained to parents requesting unnecessary antibiotics for colds and coughs. When antibiotics are necessary, the judicious choice of a narrow-spectrum antibiotic or a shorter duration of a broader spectrum antibiotic may reduce adverse effects on vaccine-induced immunity.

References

1. Valdez Y et al. Influence of the microbiota on vaccine effectiveness. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(11):526-37.

2. Lynn MA et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(5):653-60.e5.

3. Hagan T et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. 2019;178(6):1313-28.e13.

4. Chapman T et al. Antibiotic use and vaccine antibody levels. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5);1-17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

How to communicate effectively with patients when tension is high

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.