User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

When it’s not long, but medium COVID?

Symptom timelines surrounding COVID infection tend to center on either the immediate 5-day quarantine protocols for acute infection or the long-COVID symptoms that can last a month or potentially far longer.

People may return to work or daily routines, but something is off: What had been simple exercise regimens become onerous. Everyday tasks take more effort.

Does this ill-defined subset point to a “medium COVID?”

Farha Ikramuddin, MD, MHA, a physiatrist and rehabilitation specialist at the University of Minnesota and M Health Fairview in Minneapolis, points out there is no definition or diagnostic code or shared official understanding of a middle category for COVID.

“But am I seeing that? Absolutely,” she said in an interview.

“I have seen patients who are younger, healthier, [and] with not so many comorbidities have either persistence of symptoms or reappearance after the initial infection is done,” she said.

Some patients report they had very low infection or were nonsymptomatic and returned to their normal health fairly quickly after infection. Then a week later they began experiencing fatigue, lost appetite, loss of smell, and feeling full after a few bites, Dr. Ikramuddin said.

Part of the trouble in categorizing the space between returning to normal after a week and having symptoms for months is that organizations can’t agree on a timeline for when symptoms warrant a “long-COVID” label.

For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines it as 4 or more weeks after infection. The World Health Organization defines it as starting 3 months after COVID-19 symptom onset.

“I’m seeing ‘medium COVID’ – as one would call it – in younger and healthier patients. I’m also noticing that these symptoms are not severe enough to warrant stopping their job or changing their job schedules,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

They go back to work, she said, but start noticing something is off.

“I am seeing that.”

“I discharge at least two patients a week from my clinic because they have moved on and no longer have symptoms,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

In a story from Kaiser Health News published last month, WHYY health reporter Nina Feldman writes: “What I’ve come to think of as my ‘medium COVID’ affected my life. I couldn’t socialize much, drink, or stay up past 9:30 p.m. It took me 10 weeks to go for my first run – I’d been too afraid to try.”

She described a dinner with a friend after ending initial isolation protocols: “One glass of wine left me feeling like I’d had a whole bottle. I was bone-achingly exhausted but couldn’t sleep.”

Medical mystery

Dr. Ikramuddin notes the mechanism behind prolonged COVID-19 symptoms is still a medical mystery.

“In one scenario,” she said, “the question is being asked about whether the virus is staying dormant, similar to herpes zoster or HIV.”

“Right now, instead of getting more answers, we’re getting more questions,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

Mouhib Naddour, MD, a pulmonary specialist with Sharp HealthCare in San Diego, said he’s seeing that it’s taking some patients who have had COVID longer to recover than it would for other viral infections.

Some patients fall between those recovering within 2-3 weeks and patients having long COVID. Those patients in the gap could be lumped into a middle-range COVID, he told this news organization.

“We try to put things into tables and boxes but it is hard with this disease,” Dr. Naddour said.

He agrees there’s no medical definition for “medium” COVID, but he said the idea should bring hope for patients to know that, if their symptoms are persisting they don’t necessarily have long COVID – and their symptoms may still disappear.

“This is an illness that may take longer to completely recover from,” he said. “The majority of patients we’re seeing in this group could be healthy young patients who get COVID, then 2-3 weeks after they test negative, still have lingering symptoms.”

Common symptoms

Some commonly reported symptoms of those with enduring illness, which often overlap with other stages of COVID, are difficulty breathing, chest tightness, dry cough, chest pain, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, difficulty sleeping, and mood swings, Dr. Naddour said.

“We need to do an extensive assessment to make sure there’s no other problem causing these symptoms,” he said.

Still, there is no set timeline for the medium-COVID range, he noted, so checking in with a primary care physician is important for people experiencing symptoms.

It’s a continuum, not a category

Fernando Carnavali, MD, coordinator for Mount Sinai’s Center for Post-COVID Care in New York, said he is not ready to recognize a separate category for a “medium” COVID.

He noted that science can’t even agree on a name for lasting post-COVID symptoms, whether it’s “long COVID” or “long-haul COVID,” “post-COVID syndrome” or “post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC ).” There’s no agreed-upon pathophysiology or biomarker.

“That creates these gaps of understanding on where we are,” Dr. Carnavali said in an interview.

He said he understands people’s need to categorize symptoms, but rather than a middle ground he sees a continuum.

It doesn’t mean what others may call COVID’s middle ground doesn’t exist, Dr. Carnavali said: “We are in the infancy of defining this. Trying to classify them may create more anxiety.”

The clinicians interviewed for this story report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Symptom timelines surrounding COVID infection tend to center on either the immediate 5-day quarantine protocols for acute infection or the long-COVID symptoms that can last a month or potentially far longer.

People may return to work or daily routines, but something is off: What had been simple exercise regimens become onerous. Everyday tasks take more effort.

Does this ill-defined subset point to a “medium COVID?”

Farha Ikramuddin, MD, MHA, a physiatrist and rehabilitation specialist at the University of Minnesota and M Health Fairview in Minneapolis, points out there is no definition or diagnostic code or shared official understanding of a middle category for COVID.

“But am I seeing that? Absolutely,” she said in an interview.

“I have seen patients who are younger, healthier, [and] with not so many comorbidities have either persistence of symptoms or reappearance after the initial infection is done,” she said.

Some patients report they had very low infection or were nonsymptomatic and returned to their normal health fairly quickly after infection. Then a week later they began experiencing fatigue, lost appetite, loss of smell, and feeling full after a few bites, Dr. Ikramuddin said.

Part of the trouble in categorizing the space between returning to normal after a week and having symptoms for months is that organizations can’t agree on a timeline for when symptoms warrant a “long-COVID” label.

For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines it as 4 or more weeks after infection. The World Health Organization defines it as starting 3 months after COVID-19 symptom onset.

“I’m seeing ‘medium COVID’ – as one would call it – in younger and healthier patients. I’m also noticing that these symptoms are not severe enough to warrant stopping their job or changing their job schedules,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

They go back to work, she said, but start noticing something is off.

“I am seeing that.”

“I discharge at least two patients a week from my clinic because they have moved on and no longer have symptoms,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

In a story from Kaiser Health News published last month, WHYY health reporter Nina Feldman writes: “What I’ve come to think of as my ‘medium COVID’ affected my life. I couldn’t socialize much, drink, or stay up past 9:30 p.m. It took me 10 weeks to go for my first run – I’d been too afraid to try.”

She described a dinner with a friend after ending initial isolation protocols: “One glass of wine left me feeling like I’d had a whole bottle. I was bone-achingly exhausted but couldn’t sleep.”

Medical mystery

Dr. Ikramuddin notes the mechanism behind prolonged COVID-19 symptoms is still a medical mystery.

“In one scenario,” she said, “the question is being asked about whether the virus is staying dormant, similar to herpes zoster or HIV.”

“Right now, instead of getting more answers, we’re getting more questions,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

Mouhib Naddour, MD, a pulmonary specialist with Sharp HealthCare in San Diego, said he’s seeing that it’s taking some patients who have had COVID longer to recover than it would for other viral infections.

Some patients fall between those recovering within 2-3 weeks and patients having long COVID. Those patients in the gap could be lumped into a middle-range COVID, he told this news organization.

“We try to put things into tables and boxes but it is hard with this disease,” Dr. Naddour said.

He agrees there’s no medical definition for “medium” COVID, but he said the idea should bring hope for patients to know that, if their symptoms are persisting they don’t necessarily have long COVID – and their symptoms may still disappear.

“This is an illness that may take longer to completely recover from,” he said. “The majority of patients we’re seeing in this group could be healthy young patients who get COVID, then 2-3 weeks after they test negative, still have lingering symptoms.”

Common symptoms

Some commonly reported symptoms of those with enduring illness, which often overlap with other stages of COVID, are difficulty breathing, chest tightness, dry cough, chest pain, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, difficulty sleeping, and mood swings, Dr. Naddour said.

“We need to do an extensive assessment to make sure there’s no other problem causing these symptoms,” he said.

Still, there is no set timeline for the medium-COVID range, he noted, so checking in with a primary care physician is important for people experiencing symptoms.

It’s a continuum, not a category

Fernando Carnavali, MD, coordinator for Mount Sinai’s Center for Post-COVID Care in New York, said he is not ready to recognize a separate category for a “medium” COVID.

He noted that science can’t even agree on a name for lasting post-COVID symptoms, whether it’s “long COVID” or “long-haul COVID,” “post-COVID syndrome” or “post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC ).” There’s no agreed-upon pathophysiology or biomarker.

“That creates these gaps of understanding on where we are,” Dr. Carnavali said in an interview.

He said he understands people’s need to categorize symptoms, but rather than a middle ground he sees a continuum.

It doesn’t mean what others may call COVID’s middle ground doesn’t exist, Dr. Carnavali said: “We are in the infancy of defining this. Trying to classify them may create more anxiety.”

The clinicians interviewed for this story report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Symptom timelines surrounding COVID infection tend to center on either the immediate 5-day quarantine protocols for acute infection or the long-COVID symptoms that can last a month or potentially far longer.

People may return to work or daily routines, but something is off: What had been simple exercise regimens become onerous. Everyday tasks take more effort.

Does this ill-defined subset point to a “medium COVID?”

Farha Ikramuddin, MD, MHA, a physiatrist and rehabilitation specialist at the University of Minnesota and M Health Fairview in Minneapolis, points out there is no definition or diagnostic code or shared official understanding of a middle category for COVID.

“But am I seeing that? Absolutely,” she said in an interview.

“I have seen patients who are younger, healthier, [and] with not so many comorbidities have either persistence of symptoms or reappearance after the initial infection is done,” she said.

Some patients report they had very low infection or were nonsymptomatic and returned to their normal health fairly quickly after infection. Then a week later they began experiencing fatigue, lost appetite, loss of smell, and feeling full after a few bites, Dr. Ikramuddin said.

Part of the trouble in categorizing the space between returning to normal after a week and having symptoms for months is that organizations can’t agree on a timeline for when symptoms warrant a “long-COVID” label.

For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines it as 4 or more weeks after infection. The World Health Organization defines it as starting 3 months after COVID-19 symptom onset.

“I’m seeing ‘medium COVID’ – as one would call it – in younger and healthier patients. I’m also noticing that these symptoms are not severe enough to warrant stopping their job or changing their job schedules,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

They go back to work, she said, but start noticing something is off.

“I am seeing that.”

“I discharge at least two patients a week from my clinic because they have moved on and no longer have symptoms,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

In a story from Kaiser Health News published last month, WHYY health reporter Nina Feldman writes: “What I’ve come to think of as my ‘medium COVID’ affected my life. I couldn’t socialize much, drink, or stay up past 9:30 p.m. It took me 10 weeks to go for my first run – I’d been too afraid to try.”

She described a dinner with a friend after ending initial isolation protocols: “One glass of wine left me feeling like I’d had a whole bottle. I was bone-achingly exhausted but couldn’t sleep.”

Medical mystery

Dr. Ikramuddin notes the mechanism behind prolonged COVID-19 symptoms is still a medical mystery.

“In one scenario,” she said, “the question is being asked about whether the virus is staying dormant, similar to herpes zoster or HIV.”

“Right now, instead of getting more answers, we’re getting more questions,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

Mouhib Naddour, MD, a pulmonary specialist with Sharp HealthCare in San Diego, said he’s seeing that it’s taking some patients who have had COVID longer to recover than it would for other viral infections.

Some patients fall between those recovering within 2-3 weeks and patients having long COVID. Those patients in the gap could be lumped into a middle-range COVID, he told this news organization.

“We try to put things into tables and boxes but it is hard with this disease,” Dr. Naddour said.

He agrees there’s no medical definition for “medium” COVID, but he said the idea should bring hope for patients to know that, if their symptoms are persisting they don’t necessarily have long COVID – and their symptoms may still disappear.

“This is an illness that may take longer to completely recover from,” he said. “The majority of patients we’re seeing in this group could be healthy young patients who get COVID, then 2-3 weeks after they test negative, still have lingering symptoms.”

Common symptoms

Some commonly reported symptoms of those with enduring illness, which often overlap with other stages of COVID, are difficulty breathing, chest tightness, dry cough, chest pain, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, difficulty sleeping, and mood swings, Dr. Naddour said.

“We need to do an extensive assessment to make sure there’s no other problem causing these symptoms,” he said.

Still, there is no set timeline for the medium-COVID range, he noted, so checking in with a primary care physician is important for people experiencing symptoms.

It’s a continuum, not a category

Fernando Carnavali, MD, coordinator for Mount Sinai’s Center for Post-COVID Care in New York, said he is not ready to recognize a separate category for a “medium” COVID.

He noted that science can’t even agree on a name for lasting post-COVID symptoms, whether it’s “long COVID” or “long-haul COVID,” “post-COVID syndrome” or “post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC ).” There’s no agreed-upon pathophysiology or biomarker.

“That creates these gaps of understanding on where we are,” Dr. Carnavali said in an interview.

He said he understands people’s need to categorize symptoms, but rather than a middle ground he sees a continuum.

It doesn’t mean what others may call COVID’s middle ground doesn’t exist, Dr. Carnavali said: “We are in the infancy of defining this. Trying to classify them may create more anxiety.”

The clinicians interviewed for this story report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data confirm risk of Guillain-Barré with J&J COVID shot

The Janssen vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S) is a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector vaccine.

The data show no increased risk of GBS with the Pfizer (BNT162b2) or Moderna (mRNA-1273) shots – both mRNA vaccines.

“Our findings support the current guidance from U.S. health officials that preferentially recommend use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster doses,” Nicola Klein, MD, PhD, with Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center, Oakland, Calif., told this news organization.

“Individuals who choose to receive Janssen/J&J COVID-19 vaccine should be informed of the potential safety risks, including GBS,” Dr. Klein said.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Eleven cases

Between mid-December 2020 and mid-November 2021, roughly 15.1 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine were administered to nearly 7.9 million adults in the United States.

This includes roughly 483,000 doses of the Janssen vaccine, 8.8 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine, and 5.8 million doses of the Moderna vaccine.

The researchers confirmed 11 cases of GBS after the Janssen vaccine.

The unadjusted incidence of GBS (per 100,000 person-years) was 32.4 in the first 21 days after the Janssen vaccine – substantially higher than the expected background rate of 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 person-years.

There were 36 confirmed cases of GBS after mRNA vaccines. The unadjusted incidence in the first 21 days after mRNA vaccination was 1.3 per 100,000 person-years, similar to the overall expected background rate.

In an adjusted head-to-head comparison, GBS incidence during the 21 days after receipt of the Janssen vaccine was 20.6 times higher than the GBS incidence during the 21 days after the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccines, amounting to 15.5 excess cases per million Janssen vaccine recipients.

Most cases of GBS after the Janssen vaccine occurred during the 1- to 21-day risk interval, with the period of greatest risk in the 1-14 days after vaccination.

The findings of this analysis of surveillance data of COVID-19 vaccines are “consistent with an elevated risk of GBS after primary Ad26.COV2.S vaccination,” the authors wrote.

Novel presentation?

The researchers note that nearly all individuals who developed GBS after the Janssen vaccine had facial weakness or paralysis, in addition to weakness and decreased reflexes in the limbs, suggesting that the presentation of GBS after COVID-19 adenoviral vector vaccine may be novel.

“More research is needed to determine if the presentation of GBS after adenoviral vector vaccine differs from GBS after other exposures such as Campylobacter jejuni, and to investigate the mechanism for how adenoviral vector vaccines may cause GBS,” Dr. Klein and colleagues said.

“The Vaccine Safety Datalink continues to conduct safety surveillance for all COVID-19 vaccines, including monitoring for GBS and other serious health outcomes after vaccination,” Dr. Klein said in an interview.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Klein reported receiving grants from Pfizer research support for a COVID vaccine clinical trial as well as other unrelated studies, grants from Merck, grants from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Sanofi Pasteur, and grants from Protein Science (now Sanofi Pasteur) outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Janssen vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S) is a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector vaccine.

The data show no increased risk of GBS with the Pfizer (BNT162b2) or Moderna (mRNA-1273) shots – both mRNA vaccines.

“Our findings support the current guidance from U.S. health officials that preferentially recommend use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster doses,” Nicola Klein, MD, PhD, with Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center, Oakland, Calif., told this news organization.

“Individuals who choose to receive Janssen/J&J COVID-19 vaccine should be informed of the potential safety risks, including GBS,” Dr. Klein said.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Eleven cases

Between mid-December 2020 and mid-November 2021, roughly 15.1 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine were administered to nearly 7.9 million adults in the United States.

This includes roughly 483,000 doses of the Janssen vaccine, 8.8 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine, and 5.8 million doses of the Moderna vaccine.

The researchers confirmed 11 cases of GBS after the Janssen vaccine.

The unadjusted incidence of GBS (per 100,000 person-years) was 32.4 in the first 21 days after the Janssen vaccine – substantially higher than the expected background rate of 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 person-years.

There were 36 confirmed cases of GBS after mRNA vaccines. The unadjusted incidence in the first 21 days after mRNA vaccination was 1.3 per 100,000 person-years, similar to the overall expected background rate.

In an adjusted head-to-head comparison, GBS incidence during the 21 days after receipt of the Janssen vaccine was 20.6 times higher than the GBS incidence during the 21 days after the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccines, amounting to 15.5 excess cases per million Janssen vaccine recipients.

Most cases of GBS after the Janssen vaccine occurred during the 1- to 21-day risk interval, with the period of greatest risk in the 1-14 days after vaccination.

The findings of this analysis of surveillance data of COVID-19 vaccines are “consistent with an elevated risk of GBS after primary Ad26.COV2.S vaccination,” the authors wrote.

Novel presentation?

The researchers note that nearly all individuals who developed GBS after the Janssen vaccine had facial weakness or paralysis, in addition to weakness and decreased reflexes in the limbs, suggesting that the presentation of GBS after COVID-19 adenoviral vector vaccine may be novel.

“More research is needed to determine if the presentation of GBS after adenoviral vector vaccine differs from GBS after other exposures such as Campylobacter jejuni, and to investigate the mechanism for how adenoviral vector vaccines may cause GBS,” Dr. Klein and colleagues said.

“The Vaccine Safety Datalink continues to conduct safety surveillance for all COVID-19 vaccines, including monitoring for GBS and other serious health outcomes after vaccination,” Dr. Klein said in an interview.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Klein reported receiving grants from Pfizer research support for a COVID vaccine clinical trial as well as other unrelated studies, grants from Merck, grants from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Sanofi Pasteur, and grants from Protein Science (now Sanofi Pasteur) outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Janssen vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S) is a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector vaccine.

The data show no increased risk of GBS with the Pfizer (BNT162b2) or Moderna (mRNA-1273) shots – both mRNA vaccines.

“Our findings support the current guidance from U.S. health officials that preferentially recommend use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster doses,” Nicola Klein, MD, PhD, with Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center, Oakland, Calif., told this news organization.

“Individuals who choose to receive Janssen/J&J COVID-19 vaccine should be informed of the potential safety risks, including GBS,” Dr. Klein said.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Eleven cases

Between mid-December 2020 and mid-November 2021, roughly 15.1 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine were administered to nearly 7.9 million adults in the United States.

This includes roughly 483,000 doses of the Janssen vaccine, 8.8 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine, and 5.8 million doses of the Moderna vaccine.

The researchers confirmed 11 cases of GBS after the Janssen vaccine.

The unadjusted incidence of GBS (per 100,000 person-years) was 32.4 in the first 21 days after the Janssen vaccine – substantially higher than the expected background rate of 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 person-years.

There were 36 confirmed cases of GBS after mRNA vaccines. The unadjusted incidence in the first 21 days after mRNA vaccination was 1.3 per 100,000 person-years, similar to the overall expected background rate.

In an adjusted head-to-head comparison, GBS incidence during the 21 days after receipt of the Janssen vaccine was 20.6 times higher than the GBS incidence during the 21 days after the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccines, amounting to 15.5 excess cases per million Janssen vaccine recipients.

Most cases of GBS after the Janssen vaccine occurred during the 1- to 21-day risk interval, with the period of greatest risk in the 1-14 days after vaccination.

The findings of this analysis of surveillance data of COVID-19 vaccines are “consistent with an elevated risk of GBS after primary Ad26.COV2.S vaccination,” the authors wrote.

Novel presentation?

The researchers note that nearly all individuals who developed GBS after the Janssen vaccine had facial weakness or paralysis, in addition to weakness and decreased reflexes in the limbs, suggesting that the presentation of GBS after COVID-19 adenoviral vector vaccine may be novel.

“More research is needed to determine if the presentation of GBS after adenoviral vector vaccine differs from GBS after other exposures such as Campylobacter jejuni, and to investigate the mechanism for how adenoviral vector vaccines may cause GBS,” Dr. Klein and colleagues said.

“The Vaccine Safety Datalink continues to conduct safety surveillance for all COVID-19 vaccines, including monitoring for GBS and other serious health outcomes after vaccination,” Dr. Klein said in an interview.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Klein reported receiving grants from Pfizer research support for a COVID vaccine clinical trial as well as other unrelated studies, grants from Merck, grants from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Sanofi Pasteur, and grants from Protein Science (now Sanofi Pasteur) outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Maternal autoimmune diseases up risk of mental illness in children

Mental disorders were significantly more likely in children whose mothers had one of five common autoimmune diseases, a new study found.

Previous research has linked both maternal and paternal autoimmune diseases and specific mental disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but most of these studies focused on specific conditions in relatively small populations. The new study included data on more than 2 million births, making it one of the largest efforts to date to examine the association, according to the researchers, whose findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

Previous evidence of the possible association between certain maternal autoimmune diseases and mental disorders in offspring has been “scattered and limited,” which “hampered an overall understanding” of the link, Fei Li, MD, the corresponding author of the study, told this news organization.

Dr. Li, of Shanghai Jiao Tong University China, and colleagues reviewed data from a Danish registry cohort of singleton births with up to 38 years of follow-up. They explored associations between a range of maternal autoimmune diseases diagnosed before childbirth and the risks of mental disorders in children in early childhood through young adulthood.

The study population included 2,254,234 births and 38,916,359 person-years. Data on mental health were collected from the Psychiatric Central Research Register and the country’s National Patient Register. The median age of the children at the time of assessment was 16.7 years; approximately half were male.

A total of 50,863 children (2.26%) were born to mothers who had been diagnosed with autoimmune diseases before childbirth. During the follow-up period, 5,460 children of mothers with autoimmune diseases and 303,092 children of mothers without autoimmune diseases were diagnosed with a mental disorder (10.73% vs. 13.76%), according to the researchers.

The risk of being diagnosed with a mental disorder was significantly higher among children of mothers with any autoimmune disease (hazard ratio [HR,], 1.16), with an incidence of 9.38 vs. 7.91 per 1,000 person-years, the researchers reported.

The increased risk persisted when the results were classified by organ system, including connective tissue (HR, 1.11), endocrine (HR, 1.19), gastrointestinal (HR, 1.11), blood (HR, 1.10), nervous (HR, 1.17), and skin (HR, 1.19).

The five autoimmune diseases in mothers that were most commonly associated mental health disorders in children were type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis vulgaris.

The greatest risk for children of mothers with any autoimmune disease was observed for organic conditions such as delirium, (HR, 1.54), followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.42), schizophrenia (HR, 1.54), and mood problems (HR, 1.12).

Children of mothers with any autoimmune disorder also had a significantly increased risk of autism (HR, 1.21), intellectual disability (HR, 1.19), and ADHD (HR, 1.19).

The results add to evidence that activation of the maternal immune system may drive changes in the brain and behavioral problems, which has been observed in animal studies, the researchers wrote.

Potential underlying mechanisms in need of more exploration include genetic risk factors, maternal transmission of autoantibodies to the fetus during pregnancy, and the increased risk of obstetric complications, such as preterm birth, for women with autoimmune disorders that could affect mental development in children, they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on potential exacerbation of autoimmune disease activity during pregnancy and its effect on the fetus, the researchers noted. Other limitations included potential detection bias, lack of data on mental disorders in adulthood, and potential changes in diagnostic criteria over the long study period.

The results were strengthened by the use of a population-based registry, the large sample size, and ability to consider a range of confounders, the researchers said.

“This study could help acquire a comprehensive compilation of the associations between maternal autoimmune disorders diagnosed before childbirth and offspring’s mental disorders from childhood through early adulthood,” Dr. Li said in an interview.

For clinicians, Dr. Li said, the findings suggest that the offspring of mothers with autoimmune diseases may benefit from long-term surveillance for mental health disorders.

“Further studies should provide more evidence on the detailed associations of specific maternal autoimmune diseases with a full spectrum of mental disorders in offspring, and more research on underlying mechanisms is needed as well,” she said.

Pay early attention

M. Susan Jay, MD, an adjunct professor of pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said previous efforts to examine the association between maternal autoimmunity were hampered by study design, small samples, and self-report of disease history – problems the new research avoids.

The large patient population allowed for detailed subgroup analysis of different conditions and outcomes. Another advantage was the availability of sociodemographic and clinical information, which allowed for the elimination of confounding factors, said Dr. Jay, who was not involved in the research.

“It would be prudent to follow children of mothers with autoimmune disorders before or during pregnancy for mental health issues, and if identified clinically, to offer psychological and developmental behavioral support options,” Dr. Jay added.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mental disorders were significantly more likely in children whose mothers had one of five common autoimmune diseases, a new study found.

Previous research has linked both maternal and paternal autoimmune diseases and specific mental disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but most of these studies focused on specific conditions in relatively small populations. The new study included data on more than 2 million births, making it one of the largest efforts to date to examine the association, according to the researchers, whose findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

Previous evidence of the possible association between certain maternal autoimmune diseases and mental disorders in offspring has been “scattered and limited,” which “hampered an overall understanding” of the link, Fei Li, MD, the corresponding author of the study, told this news organization.

Dr. Li, of Shanghai Jiao Tong University China, and colleagues reviewed data from a Danish registry cohort of singleton births with up to 38 years of follow-up. They explored associations between a range of maternal autoimmune diseases diagnosed before childbirth and the risks of mental disorders in children in early childhood through young adulthood.

The study population included 2,254,234 births and 38,916,359 person-years. Data on mental health were collected from the Psychiatric Central Research Register and the country’s National Patient Register. The median age of the children at the time of assessment was 16.7 years; approximately half were male.

A total of 50,863 children (2.26%) were born to mothers who had been diagnosed with autoimmune diseases before childbirth. During the follow-up period, 5,460 children of mothers with autoimmune diseases and 303,092 children of mothers without autoimmune diseases were diagnosed with a mental disorder (10.73% vs. 13.76%), according to the researchers.

The risk of being diagnosed with a mental disorder was significantly higher among children of mothers with any autoimmune disease (hazard ratio [HR,], 1.16), with an incidence of 9.38 vs. 7.91 per 1,000 person-years, the researchers reported.

The increased risk persisted when the results were classified by organ system, including connective tissue (HR, 1.11), endocrine (HR, 1.19), gastrointestinal (HR, 1.11), blood (HR, 1.10), nervous (HR, 1.17), and skin (HR, 1.19).

The five autoimmune diseases in mothers that were most commonly associated mental health disorders in children were type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis vulgaris.

The greatest risk for children of mothers with any autoimmune disease was observed for organic conditions such as delirium, (HR, 1.54), followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.42), schizophrenia (HR, 1.54), and mood problems (HR, 1.12).

Children of mothers with any autoimmune disorder also had a significantly increased risk of autism (HR, 1.21), intellectual disability (HR, 1.19), and ADHD (HR, 1.19).

The results add to evidence that activation of the maternal immune system may drive changes in the brain and behavioral problems, which has been observed in animal studies, the researchers wrote.

Potential underlying mechanisms in need of more exploration include genetic risk factors, maternal transmission of autoantibodies to the fetus during pregnancy, and the increased risk of obstetric complications, such as preterm birth, for women with autoimmune disorders that could affect mental development in children, they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on potential exacerbation of autoimmune disease activity during pregnancy and its effect on the fetus, the researchers noted. Other limitations included potential detection bias, lack of data on mental disorders in adulthood, and potential changes in diagnostic criteria over the long study period.

The results were strengthened by the use of a population-based registry, the large sample size, and ability to consider a range of confounders, the researchers said.

“This study could help acquire a comprehensive compilation of the associations between maternal autoimmune disorders diagnosed before childbirth and offspring’s mental disorders from childhood through early adulthood,” Dr. Li said in an interview.

For clinicians, Dr. Li said, the findings suggest that the offspring of mothers with autoimmune diseases may benefit from long-term surveillance for mental health disorders.

“Further studies should provide more evidence on the detailed associations of specific maternal autoimmune diseases with a full spectrum of mental disorders in offspring, and more research on underlying mechanisms is needed as well,” she said.

Pay early attention

M. Susan Jay, MD, an adjunct professor of pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said previous efforts to examine the association between maternal autoimmunity were hampered by study design, small samples, and self-report of disease history – problems the new research avoids.

The large patient population allowed for detailed subgroup analysis of different conditions and outcomes. Another advantage was the availability of sociodemographic and clinical information, which allowed for the elimination of confounding factors, said Dr. Jay, who was not involved in the research.

“It would be prudent to follow children of mothers with autoimmune disorders before or during pregnancy for mental health issues, and if identified clinically, to offer psychological and developmental behavioral support options,” Dr. Jay added.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mental disorders were significantly more likely in children whose mothers had one of five common autoimmune diseases, a new study found.

Previous research has linked both maternal and paternal autoimmune diseases and specific mental disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but most of these studies focused on specific conditions in relatively small populations. The new study included data on more than 2 million births, making it one of the largest efforts to date to examine the association, according to the researchers, whose findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

Previous evidence of the possible association between certain maternal autoimmune diseases and mental disorders in offspring has been “scattered and limited,” which “hampered an overall understanding” of the link, Fei Li, MD, the corresponding author of the study, told this news organization.

Dr. Li, of Shanghai Jiao Tong University China, and colleagues reviewed data from a Danish registry cohort of singleton births with up to 38 years of follow-up. They explored associations between a range of maternal autoimmune diseases diagnosed before childbirth and the risks of mental disorders in children in early childhood through young adulthood.

The study population included 2,254,234 births and 38,916,359 person-years. Data on mental health were collected from the Psychiatric Central Research Register and the country’s National Patient Register. The median age of the children at the time of assessment was 16.7 years; approximately half were male.

A total of 50,863 children (2.26%) were born to mothers who had been diagnosed with autoimmune diseases before childbirth. During the follow-up period, 5,460 children of mothers with autoimmune diseases and 303,092 children of mothers without autoimmune diseases were diagnosed with a mental disorder (10.73% vs. 13.76%), according to the researchers.

The risk of being diagnosed with a mental disorder was significantly higher among children of mothers with any autoimmune disease (hazard ratio [HR,], 1.16), with an incidence of 9.38 vs. 7.91 per 1,000 person-years, the researchers reported.

The increased risk persisted when the results were classified by organ system, including connective tissue (HR, 1.11), endocrine (HR, 1.19), gastrointestinal (HR, 1.11), blood (HR, 1.10), nervous (HR, 1.17), and skin (HR, 1.19).

The five autoimmune diseases in mothers that were most commonly associated mental health disorders in children were type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis vulgaris.

The greatest risk for children of mothers with any autoimmune disease was observed for organic conditions such as delirium, (HR, 1.54), followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.42), schizophrenia (HR, 1.54), and mood problems (HR, 1.12).

Children of mothers with any autoimmune disorder also had a significantly increased risk of autism (HR, 1.21), intellectual disability (HR, 1.19), and ADHD (HR, 1.19).

The results add to evidence that activation of the maternal immune system may drive changes in the brain and behavioral problems, which has been observed in animal studies, the researchers wrote.

Potential underlying mechanisms in need of more exploration include genetic risk factors, maternal transmission of autoantibodies to the fetus during pregnancy, and the increased risk of obstetric complications, such as preterm birth, for women with autoimmune disorders that could affect mental development in children, they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on potential exacerbation of autoimmune disease activity during pregnancy and its effect on the fetus, the researchers noted. Other limitations included potential detection bias, lack of data on mental disorders in adulthood, and potential changes in diagnostic criteria over the long study period.

The results were strengthened by the use of a population-based registry, the large sample size, and ability to consider a range of confounders, the researchers said.

“This study could help acquire a comprehensive compilation of the associations between maternal autoimmune disorders diagnosed before childbirth and offspring’s mental disorders from childhood through early adulthood,” Dr. Li said in an interview.

For clinicians, Dr. Li said, the findings suggest that the offspring of mothers with autoimmune diseases may benefit from long-term surveillance for mental health disorders.

“Further studies should provide more evidence on the detailed associations of specific maternal autoimmune diseases with a full spectrum of mental disorders in offspring, and more research on underlying mechanisms is needed as well,” she said.

Pay early attention

M. Susan Jay, MD, an adjunct professor of pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said previous efforts to examine the association between maternal autoimmunity were hampered by study design, small samples, and self-report of disease history – problems the new research avoids.

The large patient population allowed for detailed subgroup analysis of different conditions and outcomes. Another advantage was the availability of sociodemographic and clinical information, which allowed for the elimination of confounding factors, said Dr. Jay, who was not involved in the research.

“It would be prudent to follow children of mothers with autoimmune disorders before or during pregnancy for mental health issues, and if identified clinically, to offer psychological and developmental behavioral support options,” Dr. Jay added.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Neonatal sepsis morbidity and mortality high across rich and poor countries

LISBON – A shift toward broader-spectrum antibiotics and increasing antibiotic resistance has led to high levels of mortality and neurodevelopmental impacts in surviving babies, according to a large international study conducted on four continents.

Results of the 3-year study were presented at this week’s European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID).

The observational study, NeoOBS, conducted by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) and key partners from 2018 to 2020, explored the outcomes of more than 3,200 newborns, finding an overall mortality of 11% in those with suspected neonatal sepsis. The mortality rate increased to 18% in newborns in whom a pathogen was detected in blood culture.

More than half of infection-related deaths (59%) were due to hospital-acquired infections. Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most common pathogen isolated and is usually associated with hospital-acquired infections, which are increasingly resistant to existing antibiotic treatments, said a report produced by GARDP to accompany the results.

The study also identified a worrying trend: Hospitals are frequently using last-line agents such as carbapenems because of the high degree of antibiotic resistance in their facilities. Of note, 15% of babies with neonatal sepsis were given last-line antibiotics.

Pediatrician Julia Bielicki, MD, PhD, senior lecturer, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Research Group, St. George’s University of London, and clinician at the University of Basel Children’s Hospital, Switzerland, was a coinvestigator on the NeoOBS study.

In an interview, she explained that, as well as reducing mortality, the research is about managing infections better to prevent long-term events and improve the quality of life for survivors of neonatal sepsis. “It can have life-changing impacts for so many babies,” Dr. Bielicki said. “Improving care is much more than just making sure the baby survives the episode of sepsis – it’s about ensuring these babies can become children and adults and go on to lead productive lives.”

Also, only a minority of patients (13%) received the World Health Organization guidelines for standard of care use of ampicillin and gentamicin, and there was increasing use of last-line agents such as carbapenems and even polymyxins in some settings in low- and middle-income countries. “This is alarming and foretells the impending crisis of a lack of antibiotics to treat sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant organisms,” according to the GARDP report.

There was wide variability in antibiotic combinations used across sites in Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Greece, India, Italy, Kenya, South Africa, Thailand, Uganda, and Vietnam, and often such use was not supported by underlying data.

Dr. Bielicki remarked that there was a shift toward broad-spectrum antibiotic use. “In a high-income country, you have more restrictive patterns of antibiotic use, but it isn’t necessarily less antibiotic exposure of neonates to antibiotics, but on the whole, usually narrow-spectrum agents are used.”

In Africa and Asia, on the other hand, clinicians often have to use a broader-spectrum antibiotic empirically and may need to switch to another antibiotic very quickly. “Sometimes alternatives are not available,” she pointed out.

“Local physicians are very perceptive of this problem of antibiotic resistance in their daily practice, especially in centers with high mortality,” said Dr. Bielicki, emphasizing that it is not their fault, but is “due to the limitations in terms of the weapons available to treat these babies, which strongly demonstrates the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance affecting these babies on a global scale.”

Tim Jinks, PhD, Head of Drug Resistant Infections Priority Program at Wellcome Trust, commented on the study in a series of text messages to this news organization. “This research provides further demonstration of the urgent need for improved treatment of newborns suffering with sepsis and particularly the requirement for new antibiotics that overcome the burden of drug-resistant infections caused by [antimicrobial resistance].”

“The study is a hugely important contribution to our understanding of the burden of neonatal sepsis in low- and middle- income countries,” he added, “and points toward ways that patient treatment can be improved to save more lives.”

High-, middle-, and low-income countries

The NeoOBS study gathered data from 19 hospitals in 11 high-, middle-, and low-income countries and assessed which antibiotics are currently being used to treat neonatal sepsis, as well as the degree of drug resistance associated with them. Sites included some in Italy and Greece, where most of the neonatal sepsis data currently originate, and this helped to anchor the data, Dr. Bielicki said.

The study identified babies with clinical sepsis over a 4-week period and observed how these patients were managed, particularly with respect to antibiotics, as well as outcomes including whether they recovered, remained in hospital, or died. Investigators obtained bacterial cultures from the patients and grew them to identify which organisms were causing the sepsis.

Of note, mortality varied widely between hospitals, ranging from 1% to 27%. Dr. Bielicki explained that the investigators were currently exploring the reasons behind this wide range of mortality. “There are lots of possible reasons for this, including structural factors such as how care is delivered, which is complex to measure,” she said. “It isn’t trivial to measure why, in a certain setting, mortality is low and why in another setting of comparable income range, mortality is much higher.”

Aside from the mortality results, Dr. Bielicki also emphasized that the survivors of neonatal sepsis frequently experience neurodevelopmental impacts. “A hospital may have low mortality, but many of these babies may have neurodevelopment problems, and this has a long-term impact.”

“Even though mortality might be low in a certain hospital, it might not be low in terms of morbidity,” she added.

The researchers also collected isolates from the cohort of neonates to determine which antibiotic combinations work against the pathogens. “This will help us define what sort of antibiotic regimen warrants further investigation,” Dr. Bielicki said.

Principal Investigator, Mike Sharland, MD, also from St. George’s, University of London, who is also the Antimicrobial Resistance Program Lead at Penta Child Health Research, said, in a press release, that the study had shown that antibiotic resistance is now one of the major threats to neonatal health globally. “There are virtually no studies underway on developing novel antibiotic treatments for babies with sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant infections.”

“This is a major problem for babies in all countries, both rich and poor,” he stressed.

NeoSep-1 trial to compare multiple different treatments

The results have paved the way for a major new global trial of multiple established and new antibiotics with the goal of reducing mortality from neonatal sepsis – the NeoSep1 trial.

“This is a randomized trial with a specific design that allows us to rank different treatments against each other in terms of effectiveness, safety, and costs,” Dr. Bielicki explained.

Among the antibiotics in the study are amikacin, flomoxef and amikacin, or fosfomycin and flomoxef in babies with sepsis 28 days old or younger. Similar to the NeoOBS study, patients will be recruited from all over the world, and in particular from low- and middle-income countries such as Kenya, South Africa, and other countries in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Ultimately, the researchers want to identify modifiable risk factors and enact change in practice. But Dr. Bielicki was quick to point out that it was difficult to disentangle those factors that can easily be changed. “Some can be changed in theory, but in practice it is actually difficult to change them. One modifiable risk factor that can be changed is probably infection control, so when resistant bacteria appear in a unit, we need to ensure that there is no or minimal transmission between babies.”

Luregn Schlapbach, MD, PhD, Head, department of intensive care and neonatology, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, welcomed the study, saying recent recognition of pediatric and neonatal sepsis was an urgent problem worldwide.

She referred to the 2017 WHO resolution recognizing that sepsis represents a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, affecting patients of all ages, across all continents and health care systems but that many were pediatric. “At that time, our understanding of the true burden of sepsis was limited, as was our knowledge of current epidemiology,” she said in an email interview. “The Global Burden of Disease study in 2020 revealed that about half of the approximatively 50 million global sepsis cases affect pediatric age groups, many of those during neonatal age.”

The formal acknowledgment of this extensive need emphasizes the “urgency to design preventive and therapeutic interventions to reduce this devastating burden,” Dr. Schlapbach said. “In this context, the work led by GARDP is of great importance – it is designed to improve our understanding of current practice, risk factors, and burden of neonatal sepsis across low- to middle-income settings and is essential to design adequately powered trials testing interventions such as antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes and reduce the further emergence of antimicrobial resistance.”

Dr. Bielicki and Dr. Schlapbach have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LISBON – A shift toward broader-spectrum antibiotics and increasing antibiotic resistance has led to high levels of mortality and neurodevelopmental impacts in surviving babies, according to a large international study conducted on four continents.

Results of the 3-year study were presented at this week’s European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID).

The observational study, NeoOBS, conducted by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) and key partners from 2018 to 2020, explored the outcomes of more than 3,200 newborns, finding an overall mortality of 11% in those with suspected neonatal sepsis. The mortality rate increased to 18% in newborns in whom a pathogen was detected in blood culture.

More than half of infection-related deaths (59%) were due to hospital-acquired infections. Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most common pathogen isolated and is usually associated with hospital-acquired infections, which are increasingly resistant to existing antibiotic treatments, said a report produced by GARDP to accompany the results.

The study also identified a worrying trend: Hospitals are frequently using last-line agents such as carbapenems because of the high degree of antibiotic resistance in their facilities. Of note, 15% of babies with neonatal sepsis were given last-line antibiotics.

Pediatrician Julia Bielicki, MD, PhD, senior lecturer, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Research Group, St. George’s University of London, and clinician at the University of Basel Children’s Hospital, Switzerland, was a coinvestigator on the NeoOBS study.

In an interview, she explained that, as well as reducing mortality, the research is about managing infections better to prevent long-term events and improve the quality of life for survivors of neonatal sepsis. “It can have life-changing impacts for so many babies,” Dr. Bielicki said. “Improving care is much more than just making sure the baby survives the episode of sepsis – it’s about ensuring these babies can become children and adults and go on to lead productive lives.”

Also, only a minority of patients (13%) received the World Health Organization guidelines for standard of care use of ampicillin and gentamicin, and there was increasing use of last-line agents such as carbapenems and even polymyxins in some settings in low- and middle-income countries. “This is alarming and foretells the impending crisis of a lack of antibiotics to treat sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant organisms,” according to the GARDP report.

There was wide variability in antibiotic combinations used across sites in Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Greece, India, Italy, Kenya, South Africa, Thailand, Uganda, and Vietnam, and often such use was not supported by underlying data.

Dr. Bielicki remarked that there was a shift toward broad-spectrum antibiotic use. “In a high-income country, you have more restrictive patterns of antibiotic use, but it isn’t necessarily less antibiotic exposure of neonates to antibiotics, but on the whole, usually narrow-spectrum agents are used.”

In Africa and Asia, on the other hand, clinicians often have to use a broader-spectrum antibiotic empirically and may need to switch to another antibiotic very quickly. “Sometimes alternatives are not available,” she pointed out.

“Local physicians are very perceptive of this problem of antibiotic resistance in their daily practice, especially in centers with high mortality,” said Dr. Bielicki, emphasizing that it is not their fault, but is “due to the limitations in terms of the weapons available to treat these babies, which strongly demonstrates the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance affecting these babies on a global scale.”

Tim Jinks, PhD, Head of Drug Resistant Infections Priority Program at Wellcome Trust, commented on the study in a series of text messages to this news organization. “This research provides further demonstration of the urgent need for improved treatment of newborns suffering with sepsis and particularly the requirement for new antibiotics that overcome the burden of drug-resistant infections caused by [antimicrobial resistance].”

“The study is a hugely important contribution to our understanding of the burden of neonatal sepsis in low- and middle- income countries,” he added, “and points toward ways that patient treatment can be improved to save more lives.”

High-, middle-, and low-income countries

The NeoOBS study gathered data from 19 hospitals in 11 high-, middle-, and low-income countries and assessed which antibiotics are currently being used to treat neonatal sepsis, as well as the degree of drug resistance associated with them. Sites included some in Italy and Greece, where most of the neonatal sepsis data currently originate, and this helped to anchor the data, Dr. Bielicki said.

The study identified babies with clinical sepsis over a 4-week period and observed how these patients were managed, particularly with respect to antibiotics, as well as outcomes including whether they recovered, remained in hospital, or died. Investigators obtained bacterial cultures from the patients and grew them to identify which organisms were causing the sepsis.

Of note, mortality varied widely between hospitals, ranging from 1% to 27%. Dr. Bielicki explained that the investigators were currently exploring the reasons behind this wide range of mortality. “There are lots of possible reasons for this, including structural factors such as how care is delivered, which is complex to measure,” she said. “It isn’t trivial to measure why, in a certain setting, mortality is low and why in another setting of comparable income range, mortality is much higher.”

Aside from the mortality results, Dr. Bielicki also emphasized that the survivors of neonatal sepsis frequently experience neurodevelopmental impacts. “A hospital may have low mortality, but many of these babies may have neurodevelopment problems, and this has a long-term impact.”

“Even though mortality might be low in a certain hospital, it might not be low in terms of morbidity,” she added.

The researchers also collected isolates from the cohort of neonates to determine which antibiotic combinations work against the pathogens. “This will help us define what sort of antibiotic regimen warrants further investigation,” Dr. Bielicki said.

Principal Investigator, Mike Sharland, MD, also from St. George’s, University of London, who is also the Antimicrobial Resistance Program Lead at Penta Child Health Research, said, in a press release, that the study had shown that antibiotic resistance is now one of the major threats to neonatal health globally. “There are virtually no studies underway on developing novel antibiotic treatments for babies with sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant infections.”

“This is a major problem for babies in all countries, both rich and poor,” he stressed.

NeoSep-1 trial to compare multiple different treatments

The results have paved the way for a major new global trial of multiple established and new antibiotics with the goal of reducing mortality from neonatal sepsis – the NeoSep1 trial.

“This is a randomized trial with a specific design that allows us to rank different treatments against each other in terms of effectiveness, safety, and costs,” Dr. Bielicki explained.

Among the antibiotics in the study are amikacin, flomoxef and amikacin, or fosfomycin and flomoxef in babies with sepsis 28 days old or younger. Similar to the NeoOBS study, patients will be recruited from all over the world, and in particular from low- and middle-income countries such as Kenya, South Africa, and other countries in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Ultimately, the researchers want to identify modifiable risk factors and enact change in practice. But Dr. Bielicki was quick to point out that it was difficult to disentangle those factors that can easily be changed. “Some can be changed in theory, but in practice it is actually difficult to change them. One modifiable risk factor that can be changed is probably infection control, so when resistant bacteria appear in a unit, we need to ensure that there is no or minimal transmission between babies.”

Luregn Schlapbach, MD, PhD, Head, department of intensive care and neonatology, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, welcomed the study, saying recent recognition of pediatric and neonatal sepsis was an urgent problem worldwide.

She referred to the 2017 WHO resolution recognizing that sepsis represents a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, affecting patients of all ages, across all continents and health care systems but that many were pediatric. “At that time, our understanding of the true burden of sepsis was limited, as was our knowledge of current epidemiology,” she said in an email interview. “The Global Burden of Disease study in 2020 revealed that about half of the approximatively 50 million global sepsis cases affect pediatric age groups, many of those during neonatal age.”

The formal acknowledgment of this extensive need emphasizes the “urgency to design preventive and therapeutic interventions to reduce this devastating burden,” Dr. Schlapbach said. “In this context, the work led by GARDP is of great importance – it is designed to improve our understanding of current practice, risk factors, and burden of neonatal sepsis across low- to middle-income settings and is essential to design adequately powered trials testing interventions such as antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes and reduce the further emergence of antimicrobial resistance.”

Dr. Bielicki and Dr. Schlapbach have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LISBON – A shift toward broader-spectrum antibiotics and increasing antibiotic resistance has led to high levels of mortality and neurodevelopmental impacts in surviving babies, according to a large international study conducted on four continents.

Results of the 3-year study were presented at this week’s European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID).

The observational study, NeoOBS, conducted by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) and key partners from 2018 to 2020, explored the outcomes of more than 3,200 newborns, finding an overall mortality of 11% in those with suspected neonatal sepsis. The mortality rate increased to 18% in newborns in whom a pathogen was detected in blood culture.

More than half of infection-related deaths (59%) were due to hospital-acquired infections. Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most common pathogen isolated and is usually associated with hospital-acquired infections, which are increasingly resistant to existing antibiotic treatments, said a report produced by GARDP to accompany the results.

The study also identified a worrying trend: Hospitals are frequently using last-line agents such as carbapenems because of the high degree of antibiotic resistance in their facilities. Of note, 15% of babies with neonatal sepsis were given last-line antibiotics.

Pediatrician Julia Bielicki, MD, PhD, senior lecturer, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Research Group, St. George’s University of London, and clinician at the University of Basel Children’s Hospital, Switzerland, was a coinvestigator on the NeoOBS study.

In an interview, she explained that, as well as reducing mortality, the research is about managing infections better to prevent long-term events and improve the quality of life for survivors of neonatal sepsis. “It can have life-changing impacts for so many babies,” Dr. Bielicki said. “Improving care is much more than just making sure the baby survives the episode of sepsis – it’s about ensuring these babies can become children and adults and go on to lead productive lives.”

Also, only a minority of patients (13%) received the World Health Organization guidelines for standard of care use of ampicillin and gentamicin, and there was increasing use of last-line agents such as carbapenems and even polymyxins in some settings in low- and middle-income countries. “This is alarming and foretells the impending crisis of a lack of antibiotics to treat sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant organisms,” according to the GARDP report.

There was wide variability in antibiotic combinations used across sites in Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Greece, India, Italy, Kenya, South Africa, Thailand, Uganda, and Vietnam, and often such use was not supported by underlying data.

Dr. Bielicki remarked that there was a shift toward broad-spectrum antibiotic use. “In a high-income country, you have more restrictive patterns of antibiotic use, but it isn’t necessarily less antibiotic exposure of neonates to antibiotics, but on the whole, usually narrow-spectrum agents are used.”

In Africa and Asia, on the other hand, clinicians often have to use a broader-spectrum antibiotic empirically and may need to switch to another antibiotic very quickly. “Sometimes alternatives are not available,” she pointed out.

“Local physicians are very perceptive of this problem of antibiotic resistance in their daily practice, especially in centers with high mortality,” said Dr. Bielicki, emphasizing that it is not their fault, but is “due to the limitations in terms of the weapons available to treat these babies, which strongly demonstrates the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance affecting these babies on a global scale.”

Tim Jinks, PhD, Head of Drug Resistant Infections Priority Program at Wellcome Trust, commented on the study in a series of text messages to this news organization. “This research provides further demonstration of the urgent need for improved treatment of newborns suffering with sepsis and particularly the requirement for new antibiotics that overcome the burden of drug-resistant infections caused by [antimicrobial resistance].”

“The study is a hugely important contribution to our understanding of the burden of neonatal sepsis in low- and middle- income countries,” he added, “and points toward ways that patient treatment can be improved to save more lives.”

High-, middle-, and low-income countries

The NeoOBS study gathered data from 19 hospitals in 11 high-, middle-, and low-income countries and assessed which antibiotics are currently being used to treat neonatal sepsis, as well as the degree of drug resistance associated with them. Sites included some in Italy and Greece, where most of the neonatal sepsis data currently originate, and this helped to anchor the data, Dr. Bielicki said.

The study identified babies with clinical sepsis over a 4-week period and observed how these patients were managed, particularly with respect to antibiotics, as well as outcomes including whether they recovered, remained in hospital, or died. Investigators obtained bacterial cultures from the patients and grew them to identify which organisms were causing the sepsis.

Of note, mortality varied widely between hospitals, ranging from 1% to 27%. Dr. Bielicki explained that the investigators were currently exploring the reasons behind this wide range of mortality. “There are lots of possible reasons for this, including structural factors such as how care is delivered, which is complex to measure,” she said. “It isn’t trivial to measure why, in a certain setting, mortality is low and why in another setting of comparable income range, mortality is much higher.”

Aside from the mortality results, Dr. Bielicki also emphasized that the survivors of neonatal sepsis frequently experience neurodevelopmental impacts. “A hospital may have low mortality, but many of these babies may have neurodevelopment problems, and this has a long-term impact.”

“Even though mortality might be low in a certain hospital, it might not be low in terms of morbidity,” she added.

The researchers also collected isolates from the cohort of neonates to determine which antibiotic combinations work against the pathogens. “This will help us define what sort of antibiotic regimen warrants further investigation,” Dr. Bielicki said.

Principal Investigator, Mike Sharland, MD, also from St. George’s, University of London, who is also the Antimicrobial Resistance Program Lead at Penta Child Health Research, said, in a press release, that the study had shown that antibiotic resistance is now one of the major threats to neonatal health globally. “There are virtually no studies underway on developing novel antibiotic treatments for babies with sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant infections.”

“This is a major problem for babies in all countries, both rich and poor,” he stressed.

NeoSep-1 trial to compare multiple different treatments

The results have paved the way for a major new global trial of multiple established and new antibiotics with the goal of reducing mortality from neonatal sepsis – the NeoSep1 trial.

“This is a randomized trial with a specific design that allows us to rank different treatments against each other in terms of effectiveness, safety, and costs,” Dr. Bielicki explained.

Among the antibiotics in the study are amikacin, flomoxef and amikacin, or fosfomycin and flomoxef in babies with sepsis 28 days old or younger. Similar to the NeoOBS study, patients will be recruited from all over the world, and in particular from low- and middle-income countries such as Kenya, South Africa, and other countries in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Ultimately, the researchers want to identify modifiable risk factors and enact change in practice. But Dr. Bielicki was quick to point out that it was difficult to disentangle those factors that can easily be changed. “Some can be changed in theory, but in practice it is actually difficult to change them. One modifiable risk factor that can be changed is probably infection control, so when resistant bacteria appear in a unit, we need to ensure that there is no or minimal transmission between babies.”

Luregn Schlapbach, MD, PhD, Head, department of intensive care and neonatology, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, welcomed the study, saying recent recognition of pediatric and neonatal sepsis was an urgent problem worldwide.

She referred to the 2017 WHO resolution recognizing that sepsis represents a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, affecting patients of all ages, across all continents and health care systems but that many were pediatric. “At that time, our understanding of the true burden of sepsis was limited, as was our knowledge of current epidemiology,” she said in an email interview. “The Global Burden of Disease study in 2020 revealed that about half of the approximatively 50 million global sepsis cases affect pediatric age groups, many of those during neonatal age.”

The formal acknowledgment of this extensive need emphasizes the “urgency to design preventive and therapeutic interventions to reduce this devastating burden,” Dr. Schlapbach said. “In this context, the work led by GARDP is of great importance – it is designed to improve our understanding of current practice, risk factors, and burden of neonatal sepsis across low- to middle-income settings and is essential to design adequately powered trials testing interventions such as antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes and reduce the further emergence of antimicrobial resistance.”

Dr. Bielicki and Dr. Schlapbach have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ECCMID 2022

Children and COVID: New cases up for third straight week

Moderna submitted a request to the Food and Drug administration for emergency use authorization of its COVID-19 vaccine in children under the age of 6 years, according to this news organization, and Pfizer/BioNTech officially applied for authorization of a booster dose in children aged 5-11, the companies announced.

The FDA has tentatively scheduled meetings of its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee in June to consider the applications, saying that it “understands the urgency to authorize a vaccine for age groups who are not currently eligible for vaccination and will work diligently to complete our evaluation of the data. Should any of the submissions be completed in a timely manner and the data support a clear path forward following our evaluation, the FDA will act quickly” to convene the necessary meetings.

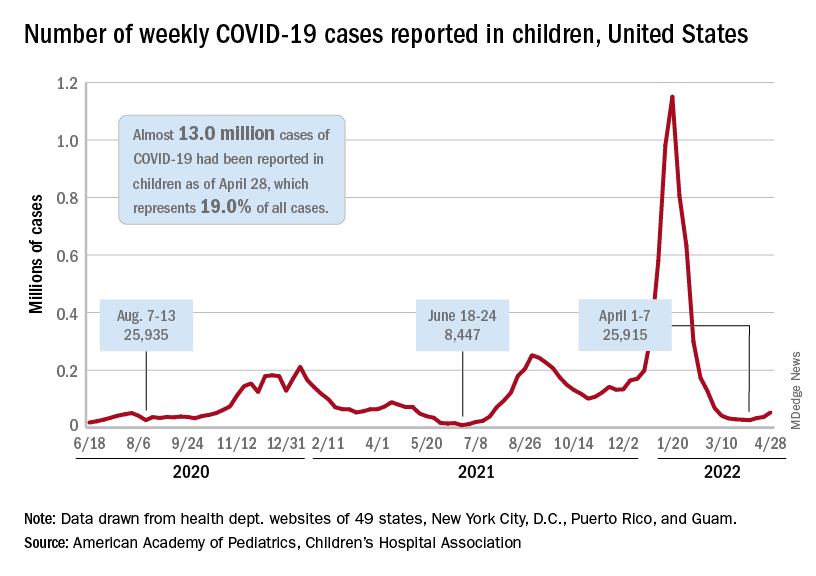

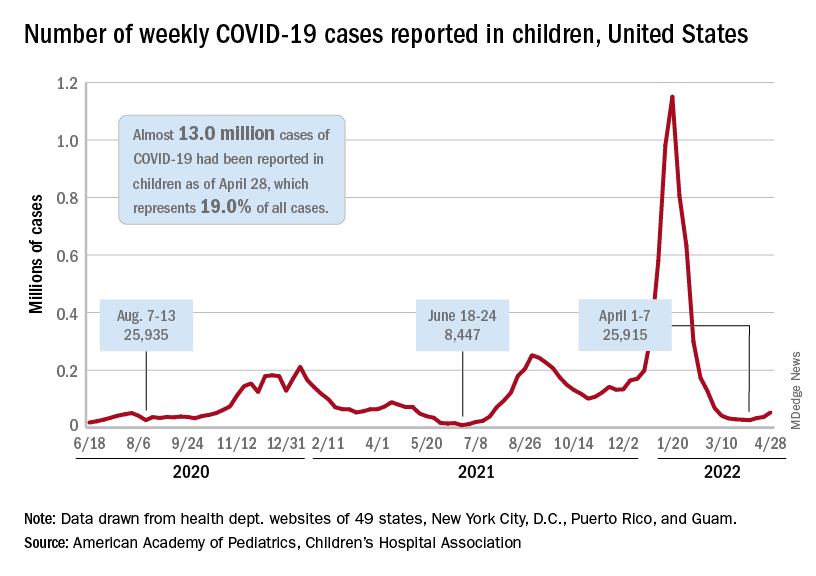

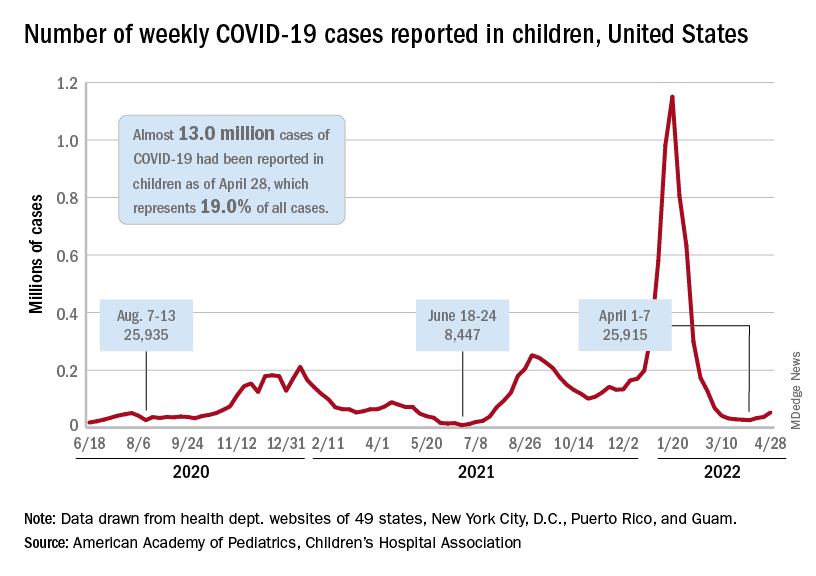

The need for greater access to vaccines seems to be increasing, as new pediatric COVID cases rose for the third consecutive week. April 22-28 saw over 53,000 new cases reported in children, up 43.5% from the previous week and up 105% since cases started rising again after dipping under 26,000 during the week of April 1-7, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Hospital admissions involving diagnosed COVID also ticked up over the latter half of April, although the most recent 7-day average (April 24-30) of 112 per day was lower than the 117 reported for the previous week (April 17-23), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, also noting that figures for the latest week “should be interpreted with caution.”

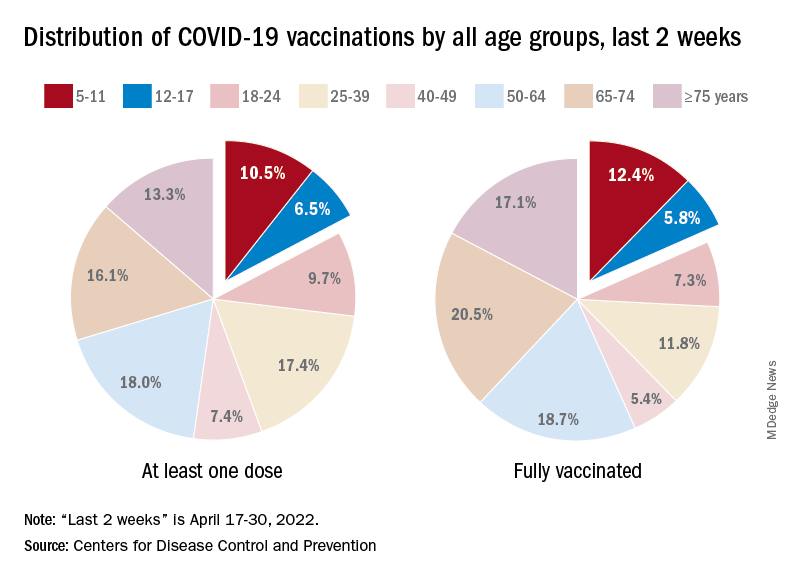

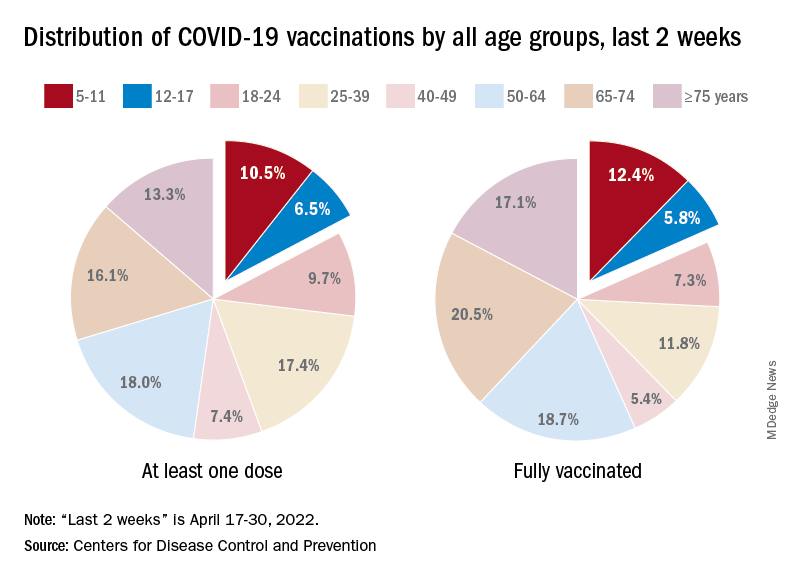

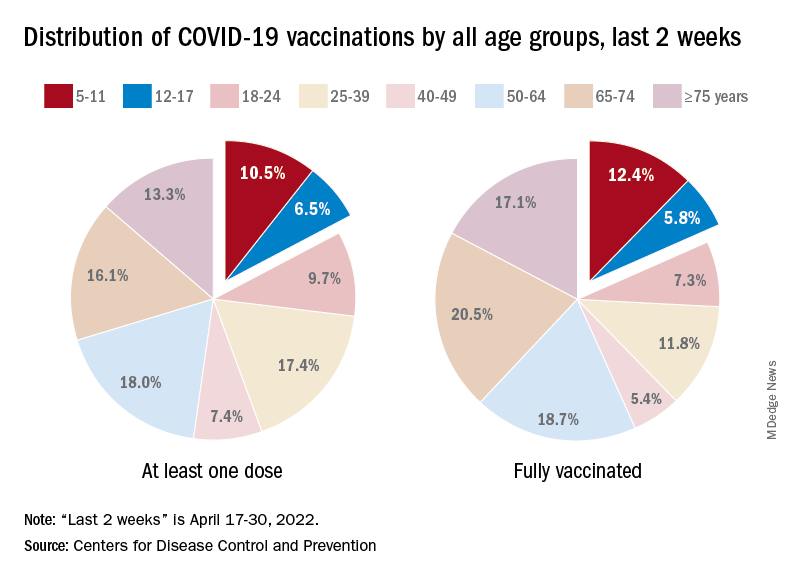

Vaccinations also were up slightly in children aged 5-11 years, with 52,000 receiving their first dose during the week of April 21-27, compared with 48,000 the week before. There was a slight dip, however, among 12- to 17-year-olds, who received 34,000 first doses during April 21-27, versus 35,000 the previous week, the AAP said in a separate report.

Cumulatively, almost 69% of all children aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and 59% are fully vaccinated. Those aged 5-11 are well short of those figures, with just over 35% having received at least one dose and 28.5% fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

A look at recent activity shows that children are not gaining on adults, who are much more likely to be vaccinated – full vaccination in those aged 50-64, for example, is 80%. During the 2 weeks from April 17-30, the 5- to 11-year-olds represented 10.5% of those who had initiated a first dose and 12.4% of those who gained full-vaccination status, both of which were well below the oldest age groups, the CDC reported.

Moderna submitted a request to the Food and Drug administration for emergency use authorization of its COVID-19 vaccine in children under the age of 6 years, according to this news organization, and Pfizer/BioNTech officially applied for authorization of a booster dose in children aged 5-11, the companies announced.

The FDA has tentatively scheduled meetings of its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee in June to consider the applications, saying that it “understands the urgency to authorize a vaccine for age groups who are not currently eligible for vaccination and will work diligently to complete our evaluation of the data. Should any of the submissions be completed in a timely manner and the data support a clear path forward following our evaluation, the FDA will act quickly” to convene the necessary meetings.

The need for greater access to vaccines seems to be increasing, as new pediatric COVID cases rose for the third consecutive week. April 22-28 saw over 53,000 new cases reported in children, up 43.5% from the previous week and up 105% since cases started rising again after dipping under 26,000 during the week of April 1-7, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.