User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

New international dermatology registry tracks monkeypox cases

The American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS) have created a new registry that now accepts reports from health care providers worldwide about monkeypox cases and monkeypox vaccine reactions.

Patient data such as names and dates of birth will not be collected.

“As with our joint COVID-19 registry, we will be doing real-time data analysis during the outbreak,” dermatologist Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, director of MGH Global Health Dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and a member of the AAD’s monkeypox task force, said in an interview. “We will to try to feed information back to our front line in terms of clinical characteristics of cases, morphology, and any unexpected findings.”

According to Dr. Freeman, the principal investigator for the COVID-19 registry, this registry has allowed the quick gathering of information about dermatologic findings of COVID-19 from over 53 countries. “We have published over 15 papers, and we share data with outside investigators wishing to do their own analysis of registry-related data,” she said. “Our most-cited paper on COVID vaccine skin reactions has been cited almost 500 times since 2021. It has been used to educate the public on vaccine side effects and to combat vaccine hesitancy.”

The monkeypox registry “doesn’t belong to any one group or person,” Dr. Freeman said. “The idea with rapid data analysis is to be able to give back to the dermatologic community what is hard for us to see with any single case: Patterns and new findings that can be helpful to share with dermatologists and other physicians worldwide, all working together to stop an outbreak.”

The American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS) have created a new registry that now accepts reports from health care providers worldwide about monkeypox cases and monkeypox vaccine reactions.

Patient data such as names and dates of birth will not be collected.

“As with our joint COVID-19 registry, we will be doing real-time data analysis during the outbreak,” dermatologist Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, director of MGH Global Health Dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and a member of the AAD’s monkeypox task force, said in an interview. “We will to try to feed information back to our front line in terms of clinical characteristics of cases, morphology, and any unexpected findings.”

According to Dr. Freeman, the principal investigator for the COVID-19 registry, this registry has allowed the quick gathering of information about dermatologic findings of COVID-19 from over 53 countries. “We have published over 15 papers, and we share data with outside investigators wishing to do their own analysis of registry-related data,” she said. “Our most-cited paper on COVID vaccine skin reactions has been cited almost 500 times since 2021. It has been used to educate the public on vaccine side effects and to combat vaccine hesitancy.”

The monkeypox registry “doesn’t belong to any one group or person,” Dr. Freeman said. “The idea with rapid data analysis is to be able to give back to the dermatologic community what is hard for us to see with any single case: Patterns and new findings that can be helpful to share with dermatologists and other physicians worldwide, all working together to stop an outbreak.”

The American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS) have created a new registry that now accepts reports from health care providers worldwide about monkeypox cases and monkeypox vaccine reactions.

Patient data such as names and dates of birth will not be collected.

“As with our joint COVID-19 registry, we will be doing real-time data analysis during the outbreak,” dermatologist Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, director of MGH Global Health Dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and a member of the AAD’s monkeypox task force, said in an interview. “We will to try to feed information back to our front line in terms of clinical characteristics of cases, morphology, and any unexpected findings.”

According to Dr. Freeman, the principal investigator for the COVID-19 registry, this registry has allowed the quick gathering of information about dermatologic findings of COVID-19 from over 53 countries. “We have published over 15 papers, and we share data with outside investigators wishing to do their own analysis of registry-related data,” she said. “Our most-cited paper on COVID vaccine skin reactions has been cited almost 500 times since 2021. It has been used to educate the public on vaccine side effects and to combat vaccine hesitancy.”

The monkeypox registry “doesn’t belong to any one group or person,” Dr. Freeman said. “The idea with rapid data analysis is to be able to give back to the dermatologic community what is hard for us to see with any single case: Patterns and new findings that can be helpful to share with dermatologists and other physicians worldwide, all working together to stop an outbreak.”

Dermatology and monkeypox: What you need to know

.

Diagnosing cases “can be hard and folks should keep a very open mind and consider monkeypox virus,” said Misha Rosenbach, MD, a University of Pennsylvania dermatologist and member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s ad hoc task force to develop monkeypox content.

Although it’s named after a primate, it turns out that monkeypox is quite the copycat. As dermatologists have learned, its lesions can look like those caused by a long list of other diseases including herpes, varicella, and syphilis. In small numbers, they can even appear to be insect bites.

To make things more complicated, a patient can have one or two lesions – or dozens. They often cluster in the anogenital area, likely reflecting transmission via sexual intercourse, unlike previous outbreaks in which lesions appeared all over the body. “We have to let go of some of our conceptions about what monkeypox might look like,” said dermatologist Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Harvard University, Boston, and a member of the AAD task force.

To make things even more complicated, “the spectrum of illness that we are seeing has ranged from limited, subtle lesions to dramatic, widespread, ulcerative/necrotic lesions,” said Dr. Rosenbach, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

But monkeypox has unique traits that can set it apart and pave the way toward a diagnosis, dermatologists say. And important patient data can help dermatologists gauge the likelihood of a case: Almost 99% of cases with data available have been in men, and among men with available information, 94% reported male-to-male sexual or close intimate contact during the 3 weeks before developing symptoms, according to a CDC report tracking cases from May through late July. So far, cases in women and children are extremely rare, although there have been some reported in the United States.

Are dermatologists likely to see monkeypox in the clinic? It’s unclear so far. Of four dermatologists interviewed for this article, only one has seen patients with monkeypox in person. But others say they’ve been sought for consultations. “I have been asked by infectious disease colleagues for advice remotely but have not seen it,” said dermatologist Howa Yeung, MD, MSc, assistant professor of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta. “Most of the time, they’re catching all the symptomatic cases before any need for dermatology in-person referrals.”

Still, the rapid rate of growth of the outbreak – up from 3,487 in the United States on July 25 to 12,689 as of Aug.16 – suggests that more dermatologists will see cases, and consultations may become more common too.

Know your lesions

Lesions are the telltale signs of symptomatic monkeypox. According to a recent New England Journal of Medicine study of 528 monkeypox cases from 16 nations, diagnosed between April 27 and June 24, 2022, 95% had skin lesions (58% were vesiculopustular), most commonly in the anogenital area (73%), and on the trunk/arms/or legs (55%) and face (25%), and the palms/soles (10%).

However, “the current monkeypox outbreak often presents differently from the multiple classic vesiculopustules on the skin we see in textbooks,” Dr. Yeung said. “Sometimes people can present with throat pain or rectal pain, with isolated pharyngitis or proctitis. Sometimes there are so few lesions on the skin that it can be easily confused with a bug bite, folliculitis, herpes, dyshidrotic eczema, or other skin problems. This is where dermatologists will get consulted to clarify the diagnosis while the monkeypox PCR test is pending.”

Dr. Rosenbach, who has provided consultation services to other physicians about cases, said the lesions often appear to be vesicles or pustules, “but if you go to ‘pop’ it – e.g., for testing – it’s firm and without fluid. This is likely due to pox virus inclusion, similar to other diseases such as molluscum,” caused by another pox virus, he said. Molluscum lesions are “characteristically umbilicated, with a dimple in the center, and monkeypox lesions seem to be showing a roughly similar morphology with many bowl- or caldera-shaped lesions that are donut-like in appearance,” he added.

Over time, Dr. Rosenbach said, “lesions tend to evolve slowly from smaller flesh-colored or vaguely white firm papules to broader more umbilicated/donut-shaped lesions which may erode, ulcerate, develop a crust or scab, and then heal. The amount of scarring is not yet clear, but we anticipate it to be significant, especially in patients with more widespread or severe disease.”

Jon Peebles, MD, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in Largo, Md., who has treated a few in-person monkeypox cases, said the lesions can be “exquisitely painful,” although he’s also seen patients with asymptomatic lesions. “Lesions are showing a predilection for the anogenital skin, though they can occur anywhere and not uncommonly involve the oral mucosa,” said Dr. Peebles, also a member of the AAD monkeypox task force.

Dr. Yeung said it’s important to ask patients about their sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexual behaviors. “That is the only way to know who your patients are and the only way to understand who else may be at risks and can benefit from contact tracing and additional prevention measures, such as vaccination for asymptomatic sex partners.” (The Jynneos smallpox vaccine is Food and Drug Administration–approved to prevent monkeypox, although its efficacy is not entirely clear, and there’s controversy over expanding its limited availability by administering the vaccine intradermally.)

It’s also important to keep in mind that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are common in gay and bisexual men. “Just because the patient is diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis does not mean the patient cannot also have monkeypox,” Dr. Rosenbach said. Indeed, the NEJM study reported that of 377 patients screened, 29% had an STI other than HIV, mostly syphilis (9%) and gonorrhea (8%). Of all 528 patients in the study (all male or transgender/nonbinary), 41% were HIV-positive, and the median number of sex partners in the last 3 months was 5 (range, 3-15).

Testing is crucial to rule monkeypox in – or out

While monkeypox lesions can be confused for other diseases, Dr. Rosenbach said that a diagnosis can be confirmed through various tests. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) have distinct findings on Tzanck smears (nuclear molding, multinucleated cells), and have widely available fairly rapid tests (PCR, or in some places, DFA). “Staph and bacterial folliculitis can usually be cultured quickly,” he said. “If you have someone with no risk factors/exposure, and you test for VZV, HSV, folliculitis, and it’s negative – you should know within 24 hours in most places – then you can broaden your differential diagnosis and consider alternate explanations, including monkeypox.”

Quest Diagnostics and Labcorp, two of the largest commercial labs in the United States, are now offering monkeypox tests. Labcorp says its test has a 2- to 3-day turnaround time.

As for treatment, some physicians are prescribing off-label use of tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX or ST-246), a smallpox antiviral treatment. The CDC offers guidelines about its use. “It seems to work very fast, with patients improving in 24-72 hours,” Dr. Rosenbach said. However, “it is still very challenging to give and get. There’s a cumbersome system to prescribe it, and it needs to be shipped from the national stockpile. Dermatologists should be working with their state health department, infection control, and infectious disease doctors.”

It’s likely that dermatologists are not comfortable with the process to access the drug, he said, “but if we do not act quickly to control the current outbreak, we will all – unfortunately – need to learn to be comfortable prescribing it.”

In regard to pain control, an over-the-counter painkiller approach may be appropriate depending on comorbidities, Dr. Rosenbach said. “Some patients with very severe disease, such as perianal involvement and proctitis, have such severe pain they need to be hospitalized. This is less common.”

Recommendations pending on scarring prevention

There’s limited high-quality evidence about the prevention of scarring in diseases like monkeypox, Dr. Rosenbach noted. “Any recommendations are usually based on very small, limited, uncontrolled studies. In the case of monkeypox, truly we are off the edge of the map.”

He advises cleaning lesions with gentle soap and water – keeping in mind that contaminated towels may spread disease – and potentially using a topical ointment-based dressing such as a Vaseline/nonstick dressing or Vaseline-impregnated gauze. If there’s concern about superinfection, as can occur with staph infections, topical antibiotics such as mupirocin 2% ointment may be appropriate, he said.

“Some folks like to try silica gel sheets to prevent scarring,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “There’s not a lot of evidence to support that, but they’re unlikely to be harmful. I would personally consider them, but it really depends on the extent of disease, anatomic sites involved, and access to care.”

Emory University’s Dr. Yeung also suggested using silicone gel or sheets to optimize the scar appearance once the lesions have crusted over. “People have used lasers, microneedling, etc., to improve smallpox scar appearance,” he added, “and I’m sure dermatologists will be the ones to study what works best for treating monkeypox scars.”

As for the big picture, Dr. Yeung said that dermatologists are critical in the fight to control monkeypox: “We can help our colleagues and patients manage symptoms and wound care, advocate for vaccination and treatment, treat long-term scarring sequelae, and destigmatize LGBTQ health care.”

The dermatologists interviewed for this article report no disclosures.

.

Diagnosing cases “can be hard and folks should keep a very open mind and consider monkeypox virus,” said Misha Rosenbach, MD, a University of Pennsylvania dermatologist and member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s ad hoc task force to develop monkeypox content.

Although it’s named after a primate, it turns out that monkeypox is quite the copycat. As dermatologists have learned, its lesions can look like those caused by a long list of other diseases including herpes, varicella, and syphilis. In small numbers, they can even appear to be insect bites.

To make things more complicated, a patient can have one or two lesions – or dozens. They often cluster in the anogenital area, likely reflecting transmission via sexual intercourse, unlike previous outbreaks in which lesions appeared all over the body. “We have to let go of some of our conceptions about what monkeypox might look like,” said dermatologist Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Harvard University, Boston, and a member of the AAD task force.

To make things even more complicated, “the spectrum of illness that we are seeing has ranged from limited, subtle lesions to dramatic, widespread, ulcerative/necrotic lesions,” said Dr. Rosenbach, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

But monkeypox has unique traits that can set it apart and pave the way toward a diagnosis, dermatologists say. And important patient data can help dermatologists gauge the likelihood of a case: Almost 99% of cases with data available have been in men, and among men with available information, 94% reported male-to-male sexual or close intimate contact during the 3 weeks before developing symptoms, according to a CDC report tracking cases from May through late July. So far, cases in women and children are extremely rare, although there have been some reported in the United States.

Are dermatologists likely to see monkeypox in the clinic? It’s unclear so far. Of four dermatologists interviewed for this article, only one has seen patients with monkeypox in person. But others say they’ve been sought for consultations. “I have been asked by infectious disease colleagues for advice remotely but have not seen it,” said dermatologist Howa Yeung, MD, MSc, assistant professor of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta. “Most of the time, they’re catching all the symptomatic cases before any need for dermatology in-person referrals.”

Still, the rapid rate of growth of the outbreak – up from 3,487 in the United States on July 25 to 12,689 as of Aug.16 – suggests that more dermatologists will see cases, and consultations may become more common too.

Know your lesions

Lesions are the telltale signs of symptomatic monkeypox. According to a recent New England Journal of Medicine study of 528 monkeypox cases from 16 nations, diagnosed between April 27 and June 24, 2022, 95% had skin lesions (58% were vesiculopustular), most commonly in the anogenital area (73%), and on the trunk/arms/or legs (55%) and face (25%), and the palms/soles (10%).

However, “the current monkeypox outbreak often presents differently from the multiple classic vesiculopustules on the skin we see in textbooks,” Dr. Yeung said. “Sometimes people can present with throat pain or rectal pain, with isolated pharyngitis or proctitis. Sometimes there are so few lesions on the skin that it can be easily confused with a bug bite, folliculitis, herpes, dyshidrotic eczema, or other skin problems. This is where dermatologists will get consulted to clarify the diagnosis while the monkeypox PCR test is pending.”

Dr. Rosenbach, who has provided consultation services to other physicians about cases, said the lesions often appear to be vesicles or pustules, “but if you go to ‘pop’ it – e.g., for testing – it’s firm and without fluid. This is likely due to pox virus inclusion, similar to other diseases such as molluscum,” caused by another pox virus, he said. Molluscum lesions are “characteristically umbilicated, with a dimple in the center, and monkeypox lesions seem to be showing a roughly similar morphology with many bowl- or caldera-shaped lesions that are donut-like in appearance,” he added.

Over time, Dr. Rosenbach said, “lesions tend to evolve slowly from smaller flesh-colored or vaguely white firm papules to broader more umbilicated/donut-shaped lesions which may erode, ulcerate, develop a crust or scab, and then heal. The amount of scarring is not yet clear, but we anticipate it to be significant, especially in patients with more widespread or severe disease.”

Jon Peebles, MD, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in Largo, Md., who has treated a few in-person monkeypox cases, said the lesions can be “exquisitely painful,” although he’s also seen patients with asymptomatic lesions. “Lesions are showing a predilection for the anogenital skin, though they can occur anywhere and not uncommonly involve the oral mucosa,” said Dr. Peebles, also a member of the AAD monkeypox task force.

Dr. Yeung said it’s important to ask patients about their sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexual behaviors. “That is the only way to know who your patients are and the only way to understand who else may be at risks and can benefit from contact tracing and additional prevention measures, such as vaccination for asymptomatic sex partners.” (The Jynneos smallpox vaccine is Food and Drug Administration–approved to prevent monkeypox, although its efficacy is not entirely clear, and there’s controversy over expanding its limited availability by administering the vaccine intradermally.)

It’s also important to keep in mind that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are common in gay and bisexual men. “Just because the patient is diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis does not mean the patient cannot also have monkeypox,” Dr. Rosenbach said. Indeed, the NEJM study reported that of 377 patients screened, 29% had an STI other than HIV, mostly syphilis (9%) and gonorrhea (8%). Of all 528 patients in the study (all male or transgender/nonbinary), 41% were HIV-positive, and the median number of sex partners in the last 3 months was 5 (range, 3-15).

Testing is crucial to rule monkeypox in – or out

While monkeypox lesions can be confused for other diseases, Dr. Rosenbach said that a diagnosis can be confirmed through various tests. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) have distinct findings on Tzanck smears (nuclear molding, multinucleated cells), and have widely available fairly rapid tests (PCR, or in some places, DFA). “Staph and bacterial folliculitis can usually be cultured quickly,” he said. “If you have someone with no risk factors/exposure, and you test for VZV, HSV, folliculitis, and it’s negative – you should know within 24 hours in most places – then you can broaden your differential diagnosis and consider alternate explanations, including monkeypox.”

Quest Diagnostics and Labcorp, two of the largest commercial labs in the United States, are now offering monkeypox tests. Labcorp says its test has a 2- to 3-day turnaround time.

As for treatment, some physicians are prescribing off-label use of tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX or ST-246), a smallpox antiviral treatment. The CDC offers guidelines about its use. “It seems to work very fast, with patients improving in 24-72 hours,” Dr. Rosenbach said. However, “it is still very challenging to give and get. There’s a cumbersome system to prescribe it, and it needs to be shipped from the national stockpile. Dermatologists should be working with their state health department, infection control, and infectious disease doctors.”

It’s likely that dermatologists are not comfortable with the process to access the drug, he said, “but if we do not act quickly to control the current outbreak, we will all – unfortunately – need to learn to be comfortable prescribing it.”

In regard to pain control, an over-the-counter painkiller approach may be appropriate depending on comorbidities, Dr. Rosenbach said. “Some patients with very severe disease, such as perianal involvement and proctitis, have such severe pain they need to be hospitalized. This is less common.”

Recommendations pending on scarring prevention

There’s limited high-quality evidence about the prevention of scarring in diseases like monkeypox, Dr. Rosenbach noted. “Any recommendations are usually based on very small, limited, uncontrolled studies. In the case of monkeypox, truly we are off the edge of the map.”

He advises cleaning lesions with gentle soap and water – keeping in mind that contaminated towels may spread disease – and potentially using a topical ointment-based dressing such as a Vaseline/nonstick dressing or Vaseline-impregnated gauze. If there’s concern about superinfection, as can occur with staph infections, topical antibiotics such as mupirocin 2% ointment may be appropriate, he said.

“Some folks like to try silica gel sheets to prevent scarring,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “There’s not a lot of evidence to support that, but they’re unlikely to be harmful. I would personally consider them, but it really depends on the extent of disease, anatomic sites involved, and access to care.”

Emory University’s Dr. Yeung also suggested using silicone gel or sheets to optimize the scar appearance once the lesions have crusted over. “People have used lasers, microneedling, etc., to improve smallpox scar appearance,” he added, “and I’m sure dermatologists will be the ones to study what works best for treating monkeypox scars.”

As for the big picture, Dr. Yeung said that dermatologists are critical in the fight to control monkeypox: “We can help our colleagues and patients manage symptoms and wound care, advocate for vaccination and treatment, treat long-term scarring sequelae, and destigmatize LGBTQ health care.”

The dermatologists interviewed for this article report no disclosures.

.

Diagnosing cases “can be hard and folks should keep a very open mind and consider monkeypox virus,” said Misha Rosenbach, MD, a University of Pennsylvania dermatologist and member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s ad hoc task force to develop monkeypox content.

Although it’s named after a primate, it turns out that monkeypox is quite the copycat. As dermatologists have learned, its lesions can look like those caused by a long list of other diseases including herpes, varicella, and syphilis. In small numbers, they can even appear to be insect bites.

To make things more complicated, a patient can have one or two lesions – or dozens. They often cluster in the anogenital area, likely reflecting transmission via sexual intercourse, unlike previous outbreaks in which lesions appeared all over the body. “We have to let go of some of our conceptions about what monkeypox might look like,” said dermatologist Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Harvard University, Boston, and a member of the AAD task force.

To make things even more complicated, “the spectrum of illness that we are seeing has ranged from limited, subtle lesions to dramatic, widespread, ulcerative/necrotic lesions,” said Dr. Rosenbach, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

But monkeypox has unique traits that can set it apart and pave the way toward a diagnosis, dermatologists say. And important patient data can help dermatologists gauge the likelihood of a case: Almost 99% of cases with data available have been in men, and among men with available information, 94% reported male-to-male sexual or close intimate contact during the 3 weeks before developing symptoms, according to a CDC report tracking cases from May through late July. So far, cases in women and children are extremely rare, although there have been some reported in the United States.

Are dermatologists likely to see monkeypox in the clinic? It’s unclear so far. Of four dermatologists interviewed for this article, only one has seen patients with monkeypox in person. But others say they’ve been sought for consultations. “I have been asked by infectious disease colleagues for advice remotely but have not seen it,” said dermatologist Howa Yeung, MD, MSc, assistant professor of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta. “Most of the time, they’re catching all the symptomatic cases before any need for dermatology in-person referrals.”

Still, the rapid rate of growth of the outbreak – up from 3,487 in the United States on July 25 to 12,689 as of Aug.16 – suggests that more dermatologists will see cases, and consultations may become more common too.

Know your lesions

Lesions are the telltale signs of symptomatic monkeypox. According to a recent New England Journal of Medicine study of 528 monkeypox cases from 16 nations, diagnosed between April 27 and June 24, 2022, 95% had skin lesions (58% were vesiculopustular), most commonly in the anogenital area (73%), and on the trunk/arms/or legs (55%) and face (25%), and the palms/soles (10%).

However, “the current monkeypox outbreak often presents differently from the multiple classic vesiculopustules on the skin we see in textbooks,” Dr. Yeung said. “Sometimes people can present with throat pain or rectal pain, with isolated pharyngitis or proctitis. Sometimes there are so few lesions on the skin that it can be easily confused with a bug bite, folliculitis, herpes, dyshidrotic eczema, or other skin problems. This is where dermatologists will get consulted to clarify the diagnosis while the monkeypox PCR test is pending.”

Dr. Rosenbach, who has provided consultation services to other physicians about cases, said the lesions often appear to be vesicles or pustules, “but if you go to ‘pop’ it – e.g., for testing – it’s firm and without fluid. This is likely due to pox virus inclusion, similar to other diseases such as molluscum,” caused by another pox virus, he said. Molluscum lesions are “characteristically umbilicated, with a dimple in the center, and monkeypox lesions seem to be showing a roughly similar morphology with many bowl- or caldera-shaped lesions that are donut-like in appearance,” he added.

Over time, Dr. Rosenbach said, “lesions tend to evolve slowly from smaller flesh-colored or vaguely white firm papules to broader more umbilicated/donut-shaped lesions which may erode, ulcerate, develop a crust or scab, and then heal. The amount of scarring is not yet clear, but we anticipate it to be significant, especially in patients with more widespread or severe disease.”

Jon Peebles, MD, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in Largo, Md., who has treated a few in-person monkeypox cases, said the lesions can be “exquisitely painful,” although he’s also seen patients with asymptomatic lesions. “Lesions are showing a predilection for the anogenital skin, though they can occur anywhere and not uncommonly involve the oral mucosa,” said Dr. Peebles, also a member of the AAD monkeypox task force.

Dr. Yeung said it’s important to ask patients about their sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexual behaviors. “That is the only way to know who your patients are and the only way to understand who else may be at risks and can benefit from contact tracing and additional prevention measures, such as vaccination for asymptomatic sex partners.” (The Jynneos smallpox vaccine is Food and Drug Administration–approved to prevent monkeypox, although its efficacy is not entirely clear, and there’s controversy over expanding its limited availability by administering the vaccine intradermally.)

It’s also important to keep in mind that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are common in gay and bisexual men. “Just because the patient is diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis does not mean the patient cannot also have monkeypox,” Dr. Rosenbach said. Indeed, the NEJM study reported that of 377 patients screened, 29% had an STI other than HIV, mostly syphilis (9%) and gonorrhea (8%). Of all 528 patients in the study (all male or transgender/nonbinary), 41% were HIV-positive, and the median number of sex partners in the last 3 months was 5 (range, 3-15).

Testing is crucial to rule monkeypox in – or out

While monkeypox lesions can be confused for other diseases, Dr. Rosenbach said that a diagnosis can be confirmed through various tests. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) have distinct findings on Tzanck smears (nuclear molding, multinucleated cells), and have widely available fairly rapid tests (PCR, or in some places, DFA). “Staph and bacterial folliculitis can usually be cultured quickly,” he said. “If you have someone with no risk factors/exposure, and you test for VZV, HSV, folliculitis, and it’s negative – you should know within 24 hours in most places – then you can broaden your differential diagnosis and consider alternate explanations, including monkeypox.”

Quest Diagnostics and Labcorp, two of the largest commercial labs in the United States, are now offering monkeypox tests. Labcorp says its test has a 2- to 3-day turnaround time.

As for treatment, some physicians are prescribing off-label use of tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX or ST-246), a smallpox antiviral treatment. The CDC offers guidelines about its use. “It seems to work very fast, with patients improving in 24-72 hours,” Dr. Rosenbach said. However, “it is still very challenging to give and get. There’s a cumbersome system to prescribe it, and it needs to be shipped from the national stockpile. Dermatologists should be working with their state health department, infection control, and infectious disease doctors.”

It’s likely that dermatologists are not comfortable with the process to access the drug, he said, “but if we do not act quickly to control the current outbreak, we will all – unfortunately – need to learn to be comfortable prescribing it.”

In regard to pain control, an over-the-counter painkiller approach may be appropriate depending on comorbidities, Dr. Rosenbach said. “Some patients with very severe disease, such as perianal involvement and proctitis, have such severe pain they need to be hospitalized. This is less common.”

Recommendations pending on scarring prevention

There’s limited high-quality evidence about the prevention of scarring in diseases like monkeypox, Dr. Rosenbach noted. “Any recommendations are usually based on very small, limited, uncontrolled studies. In the case of monkeypox, truly we are off the edge of the map.”

He advises cleaning lesions with gentle soap and water – keeping in mind that contaminated towels may spread disease – and potentially using a topical ointment-based dressing such as a Vaseline/nonstick dressing or Vaseline-impregnated gauze. If there’s concern about superinfection, as can occur with staph infections, topical antibiotics such as mupirocin 2% ointment may be appropriate, he said.

“Some folks like to try silica gel sheets to prevent scarring,” Dr. Rosenbach said. “There’s not a lot of evidence to support that, but they’re unlikely to be harmful. I would personally consider them, but it really depends on the extent of disease, anatomic sites involved, and access to care.”

Emory University’s Dr. Yeung also suggested using silicone gel or sheets to optimize the scar appearance once the lesions have crusted over. “People have used lasers, microneedling, etc., to improve smallpox scar appearance,” he added, “and I’m sure dermatologists will be the ones to study what works best for treating monkeypox scars.”

As for the big picture, Dr. Yeung said that dermatologists are critical in the fight to control monkeypox: “We can help our colleagues and patients manage symptoms and wound care, advocate for vaccination and treatment, treat long-term scarring sequelae, and destigmatize LGBTQ health care.”

The dermatologists interviewed for this article report no disclosures.

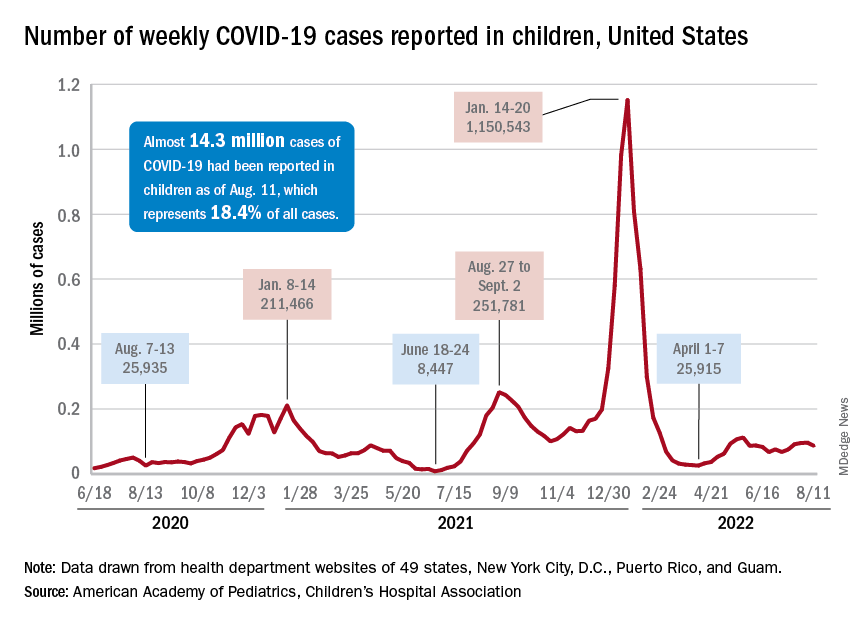

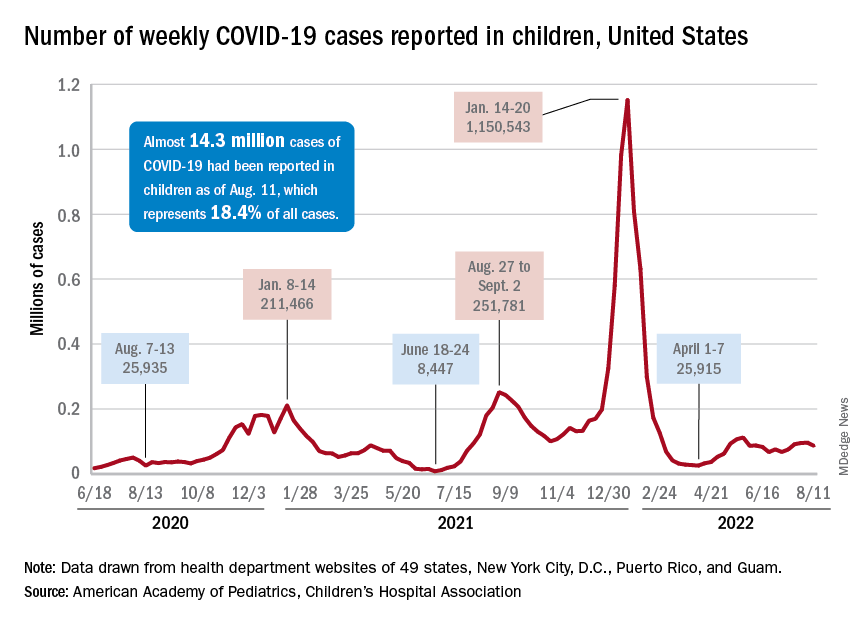

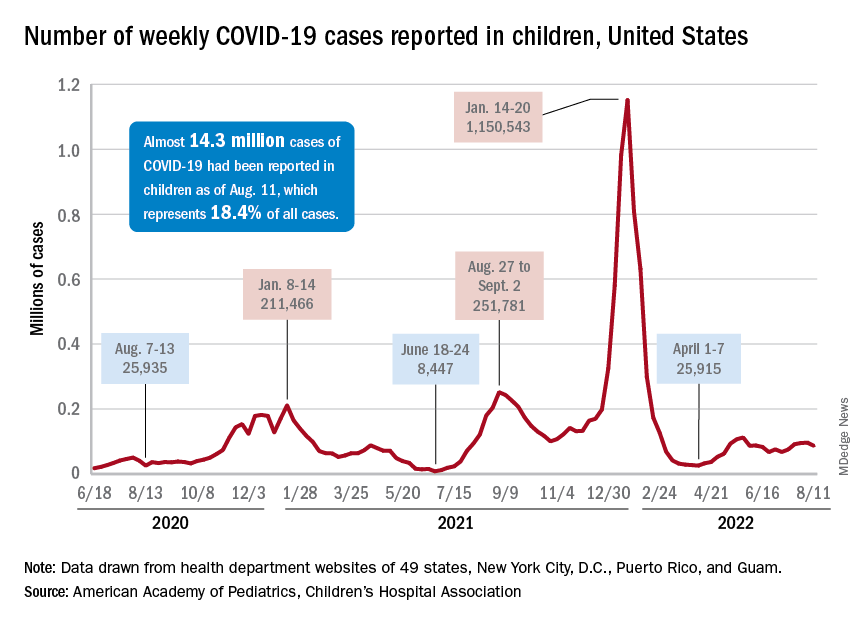

Children and COVID: ED visits and new admissions change course

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Hearing aids available in October without a prescription

The White House announced today that the Food and Drug Administration will move forward with plans to make hearing aids available over the counter in pharmacies, other retail locations, and online.

This major milestone aims to make hearing aids easier to buy and more affordable, potentially saving families thousands of dollars.

An estimated 28.8 million U.S. adults could benefit from using hearing aids, according to numbers from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. But only about 16% of people aged 20-69 years who could be helped by hearing aids have ever used them.

The risk for hearing loss increases with age. Among Americans ages 70 and older, only 30% who could hear better with these devices have ever used them, the institute reports.

Once the FDA final rule takes effect, Americans with mild to moderate hearing loss will be able to buy a hearing aid without a doctor’s exam, prescription, or fitting adjustment.

President Joe Biden announced in 2021 he intended to allow hearing aids to be sold over the counter without a prescription to increase competition among manufacturers. Congress also passed bipartisan legislation in 2017 requiring the FDA to create a new category for hearing aids sold directly to consumers. Some devices intended for minors or people with severe hearing loss will remain available only with a prescription.

“This action makes good on my commitment to lower costs for American families, delivering nearly $3,000 in savings to American families for a pair of hearing aids and giving people more choices to improve their health and wellbeing,” the president said in a statement announcing the news.

The new over-the-counter hearing aids will be considered medical devices. To avoid confusion, the FDA explains the differences between hearing aids and personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). For example, PSAPs are considered electronic devices designed for people with normal hearing to use in certain situations, like birdwatching or hunting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The White House announced today that the Food and Drug Administration will move forward with plans to make hearing aids available over the counter in pharmacies, other retail locations, and online.

This major milestone aims to make hearing aids easier to buy and more affordable, potentially saving families thousands of dollars.

An estimated 28.8 million U.S. adults could benefit from using hearing aids, according to numbers from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. But only about 16% of people aged 20-69 years who could be helped by hearing aids have ever used them.

The risk for hearing loss increases with age. Among Americans ages 70 and older, only 30% who could hear better with these devices have ever used them, the institute reports.

Once the FDA final rule takes effect, Americans with mild to moderate hearing loss will be able to buy a hearing aid without a doctor’s exam, prescription, or fitting adjustment.

President Joe Biden announced in 2021 he intended to allow hearing aids to be sold over the counter without a prescription to increase competition among manufacturers. Congress also passed bipartisan legislation in 2017 requiring the FDA to create a new category for hearing aids sold directly to consumers. Some devices intended for minors or people with severe hearing loss will remain available only with a prescription.

“This action makes good on my commitment to lower costs for American families, delivering nearly $3,000 in savings to American families for a pair of hearing aids and giving people more choices to improve their health and wellbeing,” the president said in a statement announcing the news.

The new over-the-counter hearing aids will be considered medical devices. To avoid confusion, the FDA explains the differences between hearing aids and personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). For example, PSAPs are considered electronic devices designed for people with normal hearing to use in certain situations, like birdwatching or hunting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The White House announced today that the Food and Drug Administration will move forward with plans to make hearing aids available over the counter in pharmacies, other retail locations, and online.

This major milestone aims to make hearing aids easier to buy and more affordable, potentially saving families thousands of dollars.

An estimated 28.8 million U.S. adults could benefit from using hearing aids, according to numbers from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. But only about 16% of people aged 20-69 years who could be helped by hearing aids have ever used them.

The risk for hearing loss increases with age. Among Americans ages 70 and older, only 30% who could hear better with these devices have ever used them, the institute reports.

Once the FDA final rule takes effect, Americans with mild to moderate hearing loss will be able to buy a hearing aid without a doctor’s exam, prescription, or fitting adjustment.

President Joe Biden announced in 2021 he intended to allow hearing aids to be sold over the counter without a prescription to increase competition among manufacturers. Congress also passed bipartisan legislation in 2017 requiring the FDA to create a new category for hearing aids sold directly to consumers. Some devices intended for minors or people with severe hearing loss will remain available only with a prescription.

“This action makes good on my commitment to lower costs for American families, delivering nearly $3,000 in savings to American families for a pair of hearing aids and giving people more choices to improve their health and wellbeing,” the president said in a statement announcing the news.

The new over-the-counter hearing aids will be considered medical devices. To avoid confusion, the FDA explains the differences between hearing aids and personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). For example, PSAPs are considered electronic devices designed for people with normal hearing to use in certain situations, like birdwatching or hunting.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Prematurity, family environment linked to lower rate of school readiness

Among children born prematurely, rates of school readiness were lower, compared with rates for children born full term, new data indicate.

In a Canadian cohort study that included more than 60,000 children, 35% of children born prematurely had scores on the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that indicated they were vulnerable to developmental problems, compared with 28% of children born full term.

“Our take-home message is that being born prematurely, even if all was well, is a risk factor for not being ready for school, and these families should be identified early, screened for any difficulties, and offered early intervention,” senior author Chelsea A. Ruth, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Gestational age gradient

The investigators examined two cohorts of children who were in kindergarten at the time of data collection. One of them, the population-based cohort, included children born between 2000 and 2011 whose school readiness was assessed using the EDI data. Preterm birth was defined as a gestational age (GA) of less than 37 weeks. The other, the sibling cohort, was a subset of the population cohort and included children born prematurely and their closest-in-age siblings who were born full term.

The main outcome was vulnerability in the EDI, which was defined as having a score below the 10th percentile of the Canadian population norms for one or more of the five EDI domains. These domains are physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

A total of 63,277 children were included in the analyses, of whom 4,352 were born prematurely (mean GA, 34 weeks; 53% boys) and 58,925 were born full term (mean GA, 39 weeks; 51% boys).

After data adjustment, 35% of children born prematurely were vulnerable in the EDI, compared with 28% of those born full term (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32).

The investigators found a clear GA gradient. Children born at earlier GAs (< 28 weeks or 28-33 weeks) were at higher risk of being vulnerable than those born at later GAs (34-36 weeks) in any EDI domain (48% vs. 40%) and in each of the five EDI domains. Earlier GA was associated with greater risk for vulnerability in physical health and well-being (34% vs. 22%) and in the Multiple Challenge Index (25% vs. 17%). It also was associated with greater risk for need for additional support in kindergarten (22% vs. 5%).

Furthermore, 12% of children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation were vulnerable in two EDI domains, and 8% were vulnerable in three domains. The corresponding proportions were 9% and 7%, respectively, for those born between 28 and 33 weeks and 7% and 5% for those born between 34 and 36 weeks.

“The study confirmed what we see in practice, that being born even a little bit early increases the chance for not being ready for school, and the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to have troubles,” said Dr. Ruth.

Cause or manifestation?

In the population cohort, prematurity (< 34 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.72; 34-36 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.23), male sex (AOR, 2.24), small for GA (AOR, 1.31), and various maternal medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with EDI vulnerability.

In the sibling subset, EDI outcomes were similar for children born prematurely and their siblings born full term, except for the communication skills and general knowledge domain (AOR, 1.39) and the Multiple Challenge Index (AOR, 1.43). Male sex (AOR, 2.19) was associated with EDI vulnerability in this cohort as well, as was maternal age at delivery (AOR, 1.53).

“Whether prematurity is a cause or a manifestation of an altered family ecosystem is difficult to ascertain,” Lauren Neel, MD, a neonatologist at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues write in an accompanying editorial. “However, research on this topic is much needed, along with novel interventions to change academic trajectories and care models that implement these findings in practice. As we begin to understand the factors in and interventions for promoting resilience in preterm-born children, we may need to change our research question to this: Could we optimize resilience and long-term academic trajectories to include the family as well?”

Six crucial years

Commenting on the study, Veronica Bordes Edgar, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, Dallas, said, “None of the findings surprised me, but I was very pleased that they looked at such a broad sample.”

Pediatricians should monitor and screen children for early academic readiness, since these factors are associated with later academic outcomes, Dr. Edgar added. “Early intervention does not stop at age 3, but rather the first 6 years are so crucial to lay the foundation for future success. The pediatrician can play a role in preparing children and families by promoting early reading, such as through Reach Out and Read, encouraging language-rich play, and providing guidance on early childhood education and developmental needs.

“Further examination of long-term outcomes for these children to capture the longitudinal trend would help to document what is often observed clinically, in that children who start off with difficulties do not always catch up once they are in the academic environment,” Dr. Edgar concluded.

The study was supported by Research Manitoba and the Children’s Research Institute of Manitoba. Dr. Ruth, Dr. Neel, and Dr. Edgar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among children born prematurely, rates of school readiness were lower, compared with rates for children born full term, new data indicate.

In a Canadian cohort study that included more than 60,000 children, 35% of children born prematurely had scores on the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that indicated they were vulnerable to developmental problems, compared with 28% of children born full term.

“Our take-home message is that being born prematurely, even if all was well, is a risk factor for not being ready for school, and these families should be identified early, screened for any difficulties, and offered early intervention,” senior author Chelsea A. Ruth, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Gestational age gradient

The investigators examined two cohorts of children who were in kindergarten at the time of data collection. One of them, the population-based cohort, included children born between 2000 and 2011 whose school readiness was assessed using the EDI data. Preterm birth was defined as a gestational age (GA) of less than 37 weeks. The other, the sibling cohort, was a subset of the population cohort and included children born prematurely and their closest-in-age siblings who were born full term.

The main outcome was vulnerability in the EDI, which was defined as having a score below the 10th percentile of the Canadian population norms for one or more of the five EDI domains. These domains are physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

A total of 63,277 children were included in the analyses, of whom 4,352 were born prematurely (mean GA, 34 weeks; 53% boys) and 58,925 were born full term (mean GA, 39 weeks; 51% boys).

After data adjustment, 35% of children born prematurely were vulnerable in the EDI, compared with 28% of those born full term (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32).

The investigators found a clear GA gradient. Children born at earlier GAs (< 28 weeks or 28-33 weeks) were at higher risk of being vulnerable than those born at later GAs (34-36 weeks) in any EDI domain (48% vs. 40%) and in each of the five EDI domains. Earlier GA was associated with greater risk for vulnerability in physical health and well-being (34% vs. 22%) and in the Multiple Challenge Index (25% vs. 17%). It also was associated with greater risk for need for additional support in kindergarten (22% vs. 5%).

Furthermore, 12% of children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation were vulnerable in two EDI domains, and 8% were vulnerable in three domains. The corresponding proportions were 9% and 7%, respectively, for those born between 28 and 33 weeks and 7% and 5% for those born between 34 and 36 weeks.

“The study confirmed what we see in practice, that being born even a little bit early increases the chance for not being ready for school, and the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to have troubles,” said Dr. Ruth.

Cause or manifestation?

In the population cohort, prematurity (< 34 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.72; 34-36 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.23), male sex (AOR, 2.24), small for GA (AOR, 1.31), and various maternal medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with EDI vulnerability.

In the sibling subset, EDI outcomes were similar for children born prematurely and their siblings born full term, except for the communication skills and general knowledge domain (AOR, 1.39) and the Multiple Challenge Index (AOR, 1.43). Male sex (AOR, 2.19) was associated with EDI vulnerability in this cohort as well, as was maternal age at delivery (AOR, 1.53).

“Whether prematurity is a cause or a manifestation of an altered family ecosystem is difficult to ascertain,” Lauren Neel, MD, a neonatologist at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues write in an accompanying editorial. “However, research on this topic is much needed, along with novel interventions to change academic trajectories and care models that implement these findings in practice. As we begin to understand the factors in and interventions for promoting resilience in preterm-born children, we may need to change our research question to this: Could we optimize resilience and long-term academic trajectories to include the family as well?”

Six crucial years

Commenting on the study, Veronica Bordes Edgar, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, Dallas, said, “None of the findings surprised me, but I was very pleased that they looked at such a broad sample.”

Pediatricians should monitor and screen children for early academic readiness, since these factors are associated with later academic outcomes, Dr. Edgar added. “Early intervention does not stop at age 3, but rather the first 6 years are so crucial to lay the foundation for future success. The pediatrician can play a role in preparing children and families by promoting early reading, such as through Reach Out and Read, encouraging language-rich play, and providing guidance on early childhood education and developmental needs.

“Further examination of long-term outcomes for these children to capture the longitudinal trend would help to document what is often observed clinically, in that children who start off with difficulties do not always catch up once they are in the academic environment,” Dr. Edgar concluded.

The study was supported by Research Manitoba and the Children’s Research Institute of Manitoba. Dr. Ruth, Dr. Neel, and Dr. Edgar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among children born prematurely, rates of school readiness were lower, compared with rates for children born full term, new data indicate.

In a Canadian cohort study that included more than 60,000 children, 35% of children born prematurely had scores on the Early Development Instrument (EDI) that indicated they were vulnerable to developmental problems, compared with 28% of children born full term.

“Our take-home message is that being born prematurely, even if all was well, is a risk factor for not being ready for school, and these families should be identified early, screened for any difficulties, and offered early intervention,” senior author Chelsea A. Ruth, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Gestational age gradient

The investigators examined two cohorts of children who were in kindergarten at the time of data collection. One of them, the population-based cohort, included children born between 2000 and 2011 whose school readiness was assessed using the EDI data. Preterm birth was defined as a gestational age (GA) of less than 37 weeks. The other, the sibling cohort, was a subset of the population cohort and included children born prematurely and their closest-in-age siblings who were born full term.

The main outcome was vulnerability in the EDI, which was defined as having a score below the 10th percentile of the Canadian population norms for one or more of the five EDI domains. These domains are physical health and well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive development, and communication skills and general knowledge.

A total of 63,277 children were included in the analyses, of whom 4,352 were born prematurely (mean GA, 34 weeks; 53% boys) and 58,925 were born full term (mean GA, 39 weeks; 51% boys).

After data adjustment, 35% of children born prematurely were vulnerable in the EDI, compared with 28% of those born full term (adjusted odds ratio, 1.32).

The investigators found a clear GA gradient. Children born at earlier GAs (< 28 weeks or 28-33 weeks) were at higher risk of being vulnerable than those born at later GAs (34-36 weeks) in any EDI domain (48% vs. 40%) and in each of the five EDI domains. Earlier GA was associated with greater risk for vulnerability in physical health and well-being (34% vs. 22%) and in the Multiple Challenge Index (25% vs. 17%). It also was associated with greater risk for need for additional support in kindergarten (22% vs. 5%).

Furthermore, 12% of children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation were vulnerable in two EDI domains, and 8% were vulnerable in three domains. The corresponding proportions were 9% and 7%, respectively, for those born between 28 and 33 weeks and 7% and 5% for those born between 34 and 36 weeks.

“The study confirmed what we see in practice, that being born even a little bit early increases the chance for not being ready for school, and the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to have troubles,” said Dr. Ruth.

Cause or manifestation?

In the population cohort, prematurity (< 34 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.72; 34-36 weeks’ GA: AOR, 1.23), male sex (AOR, 2.24), small for GA (AOR, 1.31), and various maternal medical and sociodemographic factors were associated with EDI vulnerability.

In the sibling subset, EDI outcomes were similar for children born prematurely and their siblings born full term, except for the communication skills and general knowledge domain (AOR, 1.39) and the Multiple Challenge Index (AOR, 1.43). Male sex (AOR, 2.19) was associated with EDI vulnerability in this cohort as well, as was maternal age at delivery (AOR, 1.53).

“Whether prematurity is a cause or a manifestation of an altered family ecosystem is difficult to ascertain,” Lauren Neel, MD, a neonatologist at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues write in an accompanying editorial. “However, research on this topic is much needed, along with novel interventions to change academic trajectories and care models that implement these findings in practice. As we begin to understand the factors in and interventions for promoting resilience in preterm-born children, we may need to change our research question to this: Could we optimize resilience and long-term academic trajectories to include the family as well?”

Six crucial years

Commenting on the study, Veronica Bordes Edgar, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, Dallas, said, “None of the findings surprised me, but I was very pleased that they looked at such a broad sample.”

Pediatricians should monitor and screen children for early academic readiness, since these factors are associated with later academic outcomes, Dr. Edgar added. “Early intervention does not stop at age 3, but rather the first 6 years are so crucial to lay the foundation for future success. The pediatrician can play a role in preparing children and families by promoting early reading, such as through Reach Out and Read, encouraging language-rich play, and providing guidance on early childhood education and developmental needs.

“Further examination of long-term outcomes for these children to capture the longitudinal trend would help to document what is often observed clinically, in that children who start off with difficulties do not always catch up once they are in the academic environment,” Dr. Edgar concluded.

The study was supported by Research Manitoba and the Children’s Research Institute of Manitoba. Dr. Ruth, Dr. Neel, and Dr. Edgar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Diagnosing children with long COVID can be tricky: Experts

When Spencer Siedlecki got COVID-19 in March 2021, he was sick for weeks with extreme fatigue, fevers, a sore throat, bad headaches, nausea, and eventually, pneumonia.

That was scary enough for the then-13-year-old and his parents, who live in Ohio. More than a year later, Spencer still had many of the symptoms and, more alarming, the once-healthy teen had postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a condition that has caused dizziness, a racing heart when he stands, and fainting. Spencer missed most of the last few months of eighth grade because of long COVID.

“He gets sick very easily,” said his mother, Melissa Siedlecki, who works in technology sales. “The common cold that he would shake off in a few days takes weeks for him to feel better.”

The transformation from regular teen life to someone with a chronic illness “sucked,” said Spencer, who will turn 15 in August. “I felt like I was never going to get better.” Fortunately, after some therapy at a specialized clinic, Spencer is back to playing baseball and golf.

Spencer’s journey to better health was difficult; his regular pediatrician told the family at first that there were no treatments to help him – a reaction that is not uncommon. “I still get a lot of parents who heard of me through the grapevine,” said Amy Edwards, MD, director of the pediatric COVID clinic at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland. “The pediatricians either are unsure of what is wrong, or worse, tell children ‘there is nothing wrong with you. Stop faking it.’ ” Dr. Edwards treated Spencer after his mother found the clinic through an internet search.

Alexandra Yonts, MD, a pediatric infectious diseases doctor and director of the post-COVID program clinic at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, has seen this too. she said.

But those who do get attention tend to be White and affluent, something Dr. Yonts said “doesn’t jibe with the epidemiologic data of who COVID has affected the most.” Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native children are more likely to be infected with COVID than White children, and have higher rates of hospitalization and death than White children.

It’s not clear whether these children have a particular risk factor, or if they are just the ones who have the resources to get to the clinics. But Dr. Yonts and Dr. Edwards believe many children are not getting the help they need. High-performing kids are coming in “because they are the ones whose symptoms are most obvious,” said Dr. Edwards. “I think there are kids out there who are getting missed because they’re already struggling because of socioeconomic reasons.”

Spencer is one of 14 million children who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 since the start of the pandemic. Many pediatricians are still grappling with how to address cases like Spencer’s. The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued only brief guidance on long COVID in children, in part because there have been so few studies to use as a basis for guidance.

The federal government is aiming to change that with a newly launched National Research Action Plan on Long COVID that includes speeding up research on how the condition affects children and youths, including their ability to learn and thrive.

A CDC study found children with COVID were significantly more likely to have smell and taste disturbances, circulatory system problems, fatigue and malaise, and pain. Those who had been infected had higher rates of acute blockage of a lung artery, myocarditis and weakening of the heart, kidney failure, and type 1 diabetes.

Difficult to diagnose

Even with increased media attention and more published studies on pediatric long COVID, it’s still hard for a busy primary care doctor “to sort through what could just be a cold or what could be a series of colds and trying to look at the bigger picture of what’s been going on in a 1- to 3-month period with a kid,” Dr. Yonts said.

Most children with potential or definite long COVID are still being seen by individual pediatricians, not in a specialized clinic with easy access to an army of specialists. It’s not clear how many of those pediatric clinics exist. Survivor Corps, an advocacy group for people with long COVID, has posted a map of locations providing care, but few are specialized or focus on pediatric long COVID.

Long COVID is different from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), which occurs within a month or so of infection, triggers high fevers and severe symptoms in the gut, and often results in hospitalization. MIS-C “is not subtle,” said Dr. Edwards.

The long COVID clinic doctors said most of their patients were not very sick at first. “Anecdotally, of the 83 kids that we’ve seen, most have had mild, very mild, or even asymptomatic infections initially,” and then went on to have long COVID, said Dr. Yonts.

“We see it even in children who have very mild disease or even are asymptomatic,” agreed Allison Eckard, MD, director of pediatric infectious diseases at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

Fatigue, mood problems

Dr. Yonts said 90% of her patients have fatigue, and many also have severe symptoms in their gut. Those and other long COVID symptoms will be looked at more closely in a 3-year study the Children’s National Medical Center is doing along with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

There are no treatments for long COVID itself.

“Management is probably more the correct term for what we do in our clinic at this point,” said Dr. Yonts. That means dealing with fatigue and managing headache and digestive symptoms with medications or coping strategies. Guidelines from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation help inform how to help kids safely resume exercise.

At the Children’s National Medical Center clinic, children will typically meet with a team of specialists including infectious diseases doctors on the same day, said Dr. Yonts. Psychologists help children with coping skills. Dr. Yonts is careful not to imply that long COVID is a psychological illness. Parents “will just shut down, because for so long, they’ve been told this is all a mental thing.”

In about a third of children, symptoms get better on their own, and most kids get better over time. But many still struggle. “We don’t talk about cure, because we don’t know what cure looks like,” said Dr. Edwards.

Vaccination may be best protection

Vaccination seems to help reduce the risk of long COVID, perhaps by as much as half. But parents have been slow to vaccinate children, especially the very young. The AAP reported that, as of Aug. 3, just 5% of children under age 5, 37% of those ages 5-11, and 69% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

“We have tried to really push vaccine as one of the ways to help prevent some of these long COVID syndromes,” said Dr. Eckard. But that advice is not always welcome. Dr. Eckard told the story of a mother who refused to have her autistic son vaccinated, even as she tearfully pleaded for help with his long COVID symptoms, which had also worsened his autism. The woman told Dr. Eckard: “Nothing you can say will convince me to get him vaccinated.” She thought a vaccine could make his symptoms even worse.

The best prevention is to avoid being infected in the first place.

“The more times you get COVID, the more you increase your risk of getting long COVID,” said Dr. Yonts. “The more times you roll the dice, eventually your number could come up.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

When Spencer Siedlecki got COVID-19 in March 2021, he was sick for weeks with extreme fatigue, fevers, a sore throat, bad headaches, nausea, and eventually, pneumonia.

That was scary enough for the then-13-year-old and his parents, who live in Ohio. More than a year later, Spencer still had many of the symptoms and, more alarming, the once-healthy teen had postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a condition that has caused dizziness, a racing heart when he stands, and fainting. Spencer missed most of the last few months of eighth grade because of long COVID.

“He gets sick very easily,” said his mother, Melissa Siedlecki, who works in technology sales. “The common cold that he would shake off in a few days takes weeks for him to feel better.”

The transformation from regular teen life to someone with a chronic illness “sucked,” said Spencer, who will turn 15 in August. “I felt like I was never going to get better.” Fortunately, after some therapy at a specialized clinic, Spencer is back to playing baseball and golf.

Spencer’s journey to better health was difficult; his regular pediatrician told the family at first that there were no treatments to help him – a reaction that is not uncommon. “I still get a lot of parents who heard of me through the grapevine,” said Amy Edwards, MD, director of the pediatric COVID clinic at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland. “The pediatricians either are unsure of what is wrong, or worse, tell children ‘there is nothing wrong with you. Stop faking it.’ ” Dr. Edwards treated Spencer after his mother found the clinic through an internet search.

Alexandra Yonts, MD, a pediatric infectious diseases doctor and director of the post-COVID program clinic at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, has seen this too. she said.

But those who do get attention tend to be White and affluent, something Dr. Yonts said “doesn’t jibe with the epidemiologic data of who COVID has affected the most.” Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native children are more likely to be infected with COVID than White children, and have higher rates of hospitalization and death than White children.

It’s not clear whether these children have a particular risk factor, or if they are just the ones who have the resources to get to the clinics. But Dr. Yonts and Dr. Edwards believe many children are not getting the help they need. High-performing kids are coming in “because they are the ones whose symptoms are most obvious,” said Dr. Edwards. “I think there are kids out there who are getting missed because they’re already struggling because of socioeconomic reasons.”

Spencer is one of 14 million children who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 since the start of the pandemic. Many pediatricians are still grappling with how to address cases like Spencer’s. The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued only brief guidance on long COVID in children, in part because there have been so few studies to use as a basis for guidance.

The federal government is aiming to change that with a newly launched National Research Action Plan on Long COVID that includes speeding up research on how the condition affects children and youths, including their ability to learn and thrive.

A CDC study found children with COVID were significantly more likely to have smell and taste disturbances, circulatory system problems, fatigue and malaise, and pain. Those who had been infected had higher rates of acute blockage of a lung artery, myocarditis and weakening of the heart, kidney failure, and type 1 diabetes.

Difficult to diagnose

Even with increased media attention and more published studies on pediatric long COVID, it’s still hard for a busy primary care doctor “to sort through what could just be a cold or what could be a series of colds and trying to look at the bigger picture of what’s been going on in a 1- to 3-month period with a kid,” Dr. Yonts said.