User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

First Omicron variant case identified in U.S.

He or she was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and experienced only “mild symptoms that are improving,” officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

The patient, who was not named in the CDC’s announcement of the first U.S. case of the Omicron variant Dec. 1, is self-quarantining.

“All close contacts have been contacted and have tested negative,” officials said.

The announcement comes as no surprise to many as the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa, has been reported in countries around the world in recent days. Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and Germany each reported this variant, as have Italy and the Netherlands. Over the weekend, the first North American cases were identified in Canada.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced over the weekend that this newest variant was likely already in the United States, telling ABC’s This Week its appearance here was “inevitable.”

Similar to previous variants, this new strain likely started circulating in the United States before scientists could do genetic tests to confirm its presence.

The World Health Organization named Omicron a “variant of concern” on Nov. 26, even though much remains unknown about how well it spreads, how severe it can be, and how it may resist vaccines. In the meantime, the United States enacted travel bans from multiple South African countries.

It remains to be seen if Omicron will follow the pattern of the Delta variant, which was first identified in the United States in May and became the dominant strain by July. It’s also possible it will follow the path taken by the Mu variant. Mu emerged in March and April to much concern, only to fizzle out by September because it was unable to compete with the Delta variant.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

He or she was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and experienced only “mild symptoms that are improving,” officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

The patient, who was not named in the CDC’s announcement of the first U.S. case of the Omicron variant Dec. 1, is self-quarantining.

“All close contacts have been contacted and have tested negative,” officials said.

The announcement comes as no surprise to many as the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa, has been reported in countries around the world in recent days. Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and Germany each reported this variant, as have Italy and the Netherlands. Over the weekend, the first North American cases were identified in Canada.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced over the weekend that this newest variant was likely already in the United States, telling ABC’s This Week its appearance here was “inevitable.”

Similar to previous variants, this new strain likely started circulating in the United States before scientists could do genetic tests to confirm its presence.

The World Health Organization named Omicron a “variant of concern” on Nov. 26, even though much remains unknown about how well it spreads, how severe it can be, and how it may resist vaccines. In the meantime, the United States enacted travel bans from multiple South African countries.

It remains to be seen if Omicron will follow the pattern of the Delta variant, which was first identified in the United States in May and became the dominant strain by July. It’s also possible it will follow the path taken by the Mu variant. Mu emerged in March and April to much concern, only to fizzle out by September because it was unable to compete with the Delta variant.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

He or she was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and experienced only “mild symptoms that are improving,” officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

The patient, who was not named in the CDC’s announcement of the first U.S. case of the Omicron variant Dec. 1, is self-quarantining.

“All close contacts have been contacted and have tested negative,” officials said.

The announcement comes as no surprise to many as the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa, has been reported in countries around the world in recent days. Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and Germany each reported this variant, as have Italy and the Netherlands. Over the weekend, the first North American cases were identified in Canada.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced over the weekend that this newest variant was likely already in the United States, telling ABC’s This Week its appearance here was “inevitable.”

Similar to previous variants, this new strain likely started circulating in the United States before scientists could do genetic tests to confirm its presence.

The World Health Organization named Omicron a “variant of concern” on Nov. 26, even though much remains unknown about how well it spreads, how severe it can be, and how it may resist vaccines. In the meantime, the United States enacted travel bans from multiple South African countries.

It remains to be seen if Omicron will follow the pattern of the Delta variant, which was first identified in the United States in May and became the dominant strain by July. It’s also possible it will follow the path taken by the Mu variant. Mu emerged in March and April to much concern, only to fizzle out by September because it was unable to compete with the Delta variant.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Moderna warns of material drop in vaccine efficacy against Omicron

“There is no world, I think, where [the effectiveness] is the same level … we had with Delta,” Stephane Bancel told the Financial Times .

“I think it’s going to be a material drop,” he said. “I just don’t know how much, because we need to wait for the data. But all the scientists I’ve talked to … are like, ‘This is not going to be good.’”

Vaccine companies are now studying whether the new Omicron variant could evade the current shots. Some data is expected in about 2 weeks.

Mr. Bancel said that if a new vaccine is needed, it could take several months to produce at scale. He estimated that Moderna could make billions of vaccine doses in 2022.

“[Moderna] and Pfizer cannot get a billion doses next week. The math doesn’t work,” he said. “But could we get the billion doses out by the summer? Sure.”

The news caused some panic on Nov. 30, prompting financial markets to fall sharply, according to Reuters. But the markets recovered after European officials gave a more reassuring outlook.

“Even if the new variant becomes more widespread, the vaccines we have will continue to provide protection,” Emer Cooke, executive director of the European Medicines Agency, told the European Parliament.

Mr. Cooke said the agency could approve new vaccines that target the Omicron variant within 3 to 4 months, if needed. Moderna and Pfizer have announced they are beginning to tailor a shot to address the Omicron variant in case the data shows they are necessary.

Also on Nov. 30, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control announced that 42 Omicron cases had been identified in 10 European Union countries, according to Reuters.

The cases were mild or had no symptoms, although they were found in younger people who may have mild or no symptoms anyway.

“For the assessment of whether [Omicron] escapes immunity, we still have to wait until investigations in the laboratories with [blood samples] from people who have recovered have been carried out,” Andrea Ammon, MD, chair of the agency, said during an online conference.

The University of Oxford, which developed a COVID-19 vaccine with AstraZeneca, said Nov. 30 that there’s no evidence that vaccines won’t prevent severe disease from the Omicron variant, according to Reuters.

“Despite the appearance of new variants over the past year, vaccines have continued to provide very high levels of protection against severe disease and there is no evidence so far that Omicron is any different,” the university said in a statement. “However, we have the necessary tools and processes in place for rapid development of an updated COVID-19 vaccine if it should be necessary.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

“There is no world, I think, where [the effectiveness] is the same level … we had with Delta,” Stephane Bancel told the Financial Times .

“I think it’s going to be a material drop,” he said. “I just don’t know how much, because we need to wait for the data. But all the scientists I’ve talked to … are like, ‘This is not going to be good.’”

Vaccine companies are now studying whether the new Omicron variant could evade the current shots. Some data is expected in about 2 weeks.

Mr. Bancel said that if a new vaccine is needed, it could take several months to produce at scale. He estimated that Moderna could make billions of vaccine doses in 2022.

“[Moderna] and Pfizer cannot get a billion doses next week. The math doesn’t work,” he said. “But could we get the billion doses out by the summer? Sure.”

The news caused some panic on Nov. 30, prompting financial markets to fall sharply, according to Reuters. But the markets recovered after European officials gave a more reassuring outlook.

“Even if the new variant becomes more widespread, the vaccines we have will continue to provide protection,” Emer Cooke, executive director of the European Medicines Agency, told the European Parliament.

Mr. Cooke said the agency could approve new vaccines that target the Omicron variant within 3 to 4 months, if needed. Moderna and Pfizer have announced they are beginning to tailor a shot to address the Omicron variant in case the data shows they are necessary.

Also on Nov. 30, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control announced that 42 Omicron cases had been identified in 10 European Union countries, according to Reuters.

The cases were mild or had no symptoms, although they were found in younger people who may have mild or no symptoms anyway.

“For the assessment of whether [Omicron] escapes immunity, we still have to wait until investigations in the laboratories with [blood samples] from people who have recovered have been carried out,” Andrea Ammon, MD, chair of the agency, said during an online conference.

The University of Oxford, which developed a COVID-19 vaccine with AstraZeneca, said Nov. 30 that there’s no evidence that vaccines won’t prevent severe disease from the Omicron variant, according to Reuters.

“Despite the appearance of new variants over the past year, vaccines have continued to provide very high levels of protection against severe disease and there is no evidence so far that Omicron is any different,” the university said in a statement. “However, we have the necessary tools and processes in place for rapid development of an updated COVID-19 vaccine if it should be necessary.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

“There is no world, I think, where [the effectiveness] is the same level … we had with Delta,” Stephane Bancel told the Financial Times .

“I think it’s going to be a material drop,” he said. “I just don’t know how much, because we need to wait for the data. But all the scientists I’ve talked to … are like, ‘This is not going to be good.’”

Vaccine companies are now studying whether the new Omicron variant could evade the current shots. Some data is expected in about 2 weeks.

Mr. Bancel said that if a new vaccine is needed, it could take several months to produce at scale. He estimated that Moderna could make billions of vaccine doses in 2022.

“[Moderna] and Pfizer cannot get a billion doses next week. The math doesn’t work,” he said. “But could we get the billion doses out by the summer? Sure.”

The news caused some panic on Nov. 30, prompting financial markets to fall sharply, according to Reuters. But the markets recovered after European officials gave a more reassuring outlook.

“Even if the new variant becomes more widespread, the vaccines we have will continue to provide protection,” Emer Cooke, executive director of the European Medicines Agency, told the European Parliament.

Mr. Cooke said the agency could approve new vaccines that target the Omicron variant within 3 to 4 months, if needed. Moderna and Pfizer have announced they are beginning to tailor a shot to address the Omicron variant in case the data shows they are necessary.

Also on Nov. 30, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control announced that 42 Omicron cases had been identified in 10 European Union countries, according to Reuters.

The cases were mild or had no symptoms, although they were found in younger people who may have mild or no symptoms anyway.

“For the assessment of whether [Omicron] escapes immunity, we still have to wait until investigations in the laboratories with [blood samples] from people who have recovered have been carried out,” Andrea Ammon, MD, chair of the agency, said during an online conference.

The University of Oxford, which developed a COVID-19 vaccine with AstraZeneca, said Nov. 30 that there’s no evidence that vaccines won’t prevent severe disease from the Omicron variant, according to Reuters.

“Despite the appearance of new variants over the past year, vaccines have continued to provide very high levels of protection against severe disease and there is no evidence so far that Omicron is any different,” the university said in a statement. “However, we have the necessary tools and processes in place for rapid development of an updated COVID-19 vaccine if it should be necessary.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases, vaccinations both decline

States reported 131,828 new pediatric cases for the week of Nov. 19-25, a decline of 7.1% over the previous week but still enough to surpass 100,000 for the 16th consecutive week. The weekly count had risen for 3 straight weeks since the last decrease in late October, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said Nov. 30 in their weekly COVID report.

The AAP/CHA analysis, based on data from state and territorial health departments, puts the total number of cases in children at 6.9 million since the pandemic began, representing 17.0% of cases in Americans of all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which uses an age limit of 18 years to define a child, unlike some states, reports numbers of 6.1 million and 15.5%.

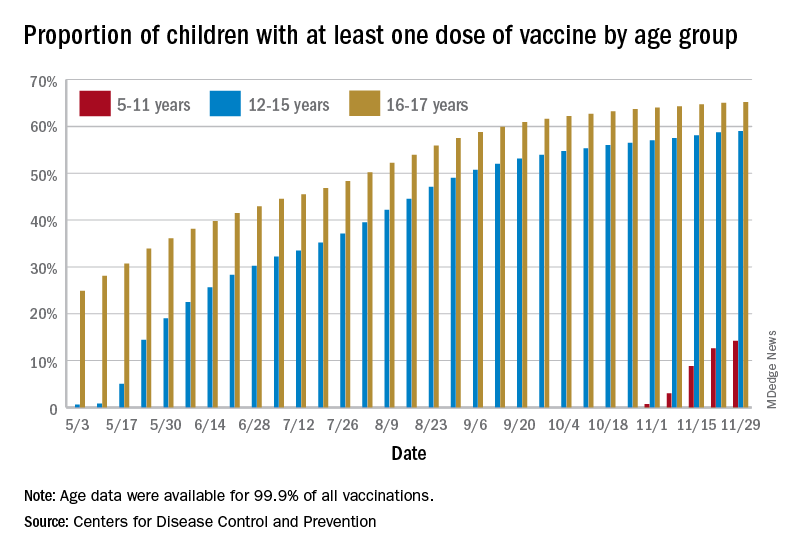

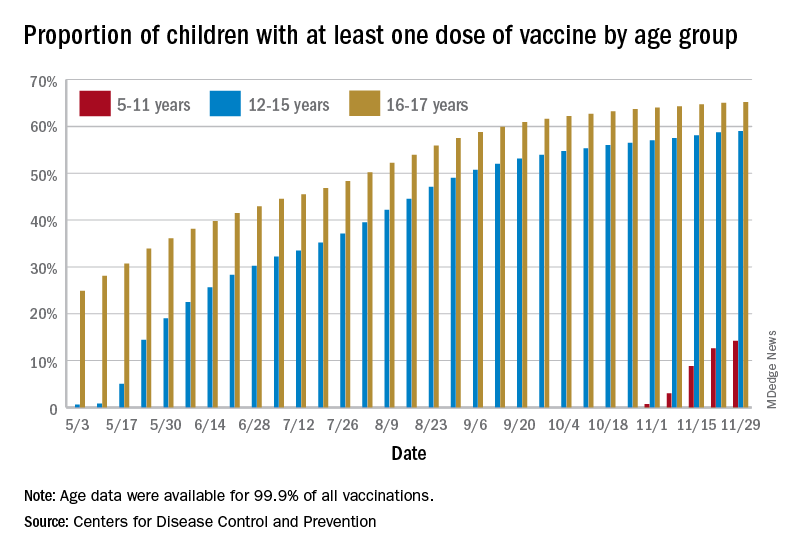

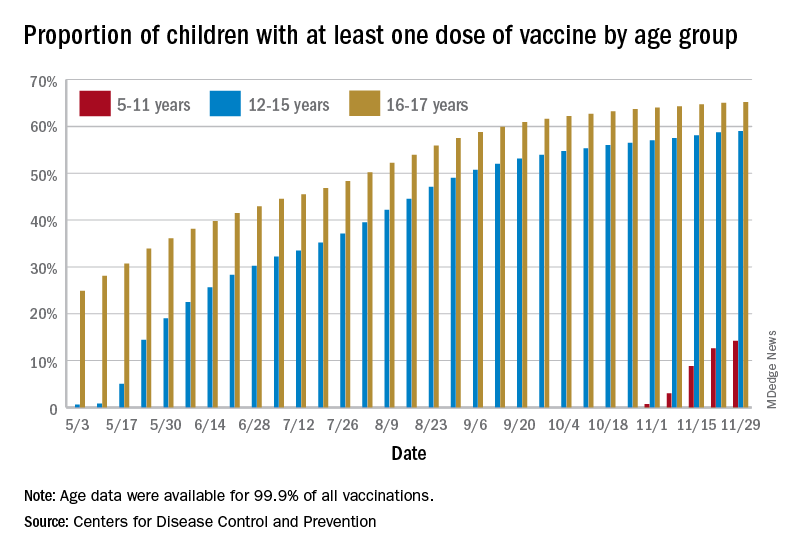

New vaccinations among the youngest eligible children, those aged 5-11 years, were down for the second week in a row after reaching almost 1.7 million during the first full week after approval on Nov. 2. Since then, the vaccination counts have been 1.2 million (Nov. 16-22) and 333,000 (Nov. 23-29), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. A similar drop in the last week – from 127,000 to just 50,000 – also was seen for those aged 12-17 years.

Altogether, 14.2% of children aged 5-11, almost 4.1 million individuals, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 59.0% (10 million) of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 65.2% (5.5 million) of those aged 16-17. Just under 1% of the youngest group has been fully vaccinated, versus 49.0% and 55.8% for the older children, the CDC said.

It has been reported that Pfizer and BioNTech, which produce the only COVID vaccine approved for children, are planning to apply to the Food and Drug Administration during the first week of December for authorization for a booster dose for 16- and 17-year-olds.

States reported 131,828 new pediatric cases for the week of Nov. 19-25, a decline of 7.1% over the previous week but still enough to surpass 100,000 for the 16th consecutive week. The weekly count had risen for 3 straight weeks since the last decrease in late October, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said Nov. 30 in their weekly COVID report.

The AAP/CHA analysis, based on data from state and territorial health departments, puts the total number of cases in children at 6.9 million since the pandemic began, representing 17.0% of cases in Americans of all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which uses an age limit of 18 years to define a child, unlike some states, reports numbers of 6.1 million and 15.5%.

New vaccinations among the youngest eligible children, those aged 5-11 years, were down for the second week in a row after reaching almost 1.7 million during the first full week after approval on Nov. 2. Since then, the vaccination counts have been 1.2 million (Nov. 16-22) and 333,000 (Nov. 23-29), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. A similar drop in the last week – from 127,000 to just 50,000 – also was seen for those aged 12-17 years.

Altogether, 14.2% of children aged 5-11, almost 4.1 million individuals, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 59.0% (10 million) of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 65.2% (5.5 million) of those aged 16-17. Just under 1% of the youngest group has been fully vaccinated, versus 49.0% and 55.8% for the older children, the CDC said.

It has been reported that Pfizer and BioNTech, which produce the only COVID vaccine approved for children, are planning to apply to the Food and Drug Administration during the first week of December for authorization for a booster dose for 16- and 17-year-olds.

States reported 131,828 new pediatric cases for the week of Nov. 19-25, a decline of 7.1% over the previous week but still enough to surpass 100,000 for the 16th consecutive week. The weekly count had risen for 3 straight weeks since the last decrease in late October, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said Nov. 30 in their weekly COVID report.

The AAP/CHA analysis, based on data from state and territorial health departments, puts the total number of cases in children at 6.9 million since the pandemic began, representing 17.0% of cases in Americans of all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which uses an age limit of 18 years to define a child, unlike some states, reports numbers of 6.1 million and 15.5%.

New vaccinations among the youngest eligible children, those aged 5-11 years, were down for the second week in a row after reaching almost 1.7 million during the first full week after approval on Nov. 2. Since then, the vaccination counts have been 1.2 million (Nov. 16-22) and 333,000 (Nov. 23-29), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. A similar drop in the last week – from 127,000 to just 50,000 – also was seen for those aged 12-17 years.

Altogether, 14.2% of children aged 5-11, almost 4.1 million individuals, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 59.0% (10 million) of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 65.2% (5.5 million) of those aged 16-17. Just under 1% of the youngest group has been fully vaccinated, versus 49.0% and 55.8% for the older children, the CDC said.

It has been reported that Pfizer and BioNTech, which produce the only COVID vaccine approved for children, are planning to apply to the Food and Drug Administration during the first week of December for authorization for a booster dose for 16- and 17-year-olds.

Association of height, BMI, and AD in young children may be transient

The , according to a large cohort study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

“The potential for ‘catch up’ in height for children with atopic dermatitis observed in our study may be explained with resolution of atopic dermatitis or successful treatment,” write senior author Aaron M. Drucker, MD, ScM, from the division of dermatology, University of Toronto, and Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, and colleagues. They postulated that, while the association between AD and shorter height is “is likely multifactorial,” it may be driven in part by sleep loss caused by AD, or corticosteroid treatment of AD, both of which can result in growth retardation and subsequent increased BMI.

The researchers used data from TARGet Kids!, a prospective, longitudinal cohort study designed to study multiple health conditions in children from general pediatric and family practices across Toronto. Their study included 10,611 children for whom there was data on height, weight, BMI, and standardized z scores, which account for age and sex differences in anthropometric characteristics. Clinically relevant covariates that were collected included child age, sex, birth weight, history of asthma, family income, maternal and paternal ethnicity, and maternal height and BMI.

The mean age of the children in the study at cohort entry was 23 months, and they were followed for a median of 28.5 months, during which time they had a median of two visits. At baseline, 947 (8.9%) children had parent-reported AD, with this number rising to 1,834 (17.3%) during follow-up.

After adjusting for covariates, AD was associated with lower mean z-height (P < .001), higher mean z-BMI (P = .008), but lower mean z-weight (P < .001), compared with children without AD. Using World Health Organization growth tables, the researchers estimated that “children with atopic dermatitis were, on average, approximately 0.5 cm shorter at age 2 years and 0.6 cm shorter at age 5 years than children without atopic dermatitis” after adjusting for covariates. They also estimated that children with AD were “on average, approximately 0.2 more BMI units at age 2 years” than children without AD. The associations between AD and height diminished by age 14 years, as did the association between AD and BMI by age 5.5 years.

“Given that we found children with atopic dermatitis to be somewhat less heavy, as measured by z-weight, than children without atopic dermatitis and that this association did not attenuate with age, it is possible that our findings for BMI, and perhaps those of previous studies, are explained mainly by differences in height,” the authors write. “This distinction has obvious clinical importance – rather than a focus on obesity and obesogenic behaviors being problematic in children with atopic dermatitis, research might be better directed at understanding the association between atopic dermatitis and initially shorter stature.”

Asked to comment on the study results, Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, told this news organization he would have preferred using the wording “in addition to focusing on obesity,” rather than “focus on obesity.”

“We should not ignore diet and sedentary activity as important factors,” he said, pointing to another recent study that found higher rates of eating disorders associated with AD.

Dr. Silverberg said that he was not familiar enough with the cohort sample to comment on how representative it is of the Canadian population, or on how generalizable the results are to other regions and populations. Generalizability, he added, “is an important issue, as we previously found regional differences with respect to the association between AD and obesity.”

In addition, he noted that in the study AD was defined as an “ever history” of disease rather than “in the past year or currently,” so, even though it is a longitudinal study, “it is really looking at how AD at any point in patients’ lives is related to weight or stature,” he explained. But, he added, “many cases of childhood AD ‘burn out’ or become milder/clear as the children get older. So, if the AD clears, then one would expect to see attenuation of associations as the children get older. However, this doesn’t tell us about how persistent AD into later childhood or adolescence is related to height or weight.”

Previous studies found that short stature and obesity were particularly associated with moderate – and even more to severe – atopic dermatitis, Dr. Silverberg said. It is likely that most patients in this primary care cohort had mild disease, he noted, so the effect sizes are likely diluted by mostly mild disease “and not relevant to the more persistent and severe AD patients encountered in the dermatology practice setting.”

The study was supported by the department of medicine, Women’s College Hospital, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

One author reported receiving compensation from the British Journal of Dermatology, the American Academy of Dermatology, and the National Eczema Association and has served as a paid consultant for the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Silverberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH

Among the more puzzling “associations” to emerge in recent literature has been the association between atopic dermatitis (AD) and obesity. I see many children with severe AD every day and my gestalt “association” is a thinner, shorter child rather than an overweight one. Dr. Drucker and colleagues’ data has helped me understand this dissonance. Children with AD do in fact, on average, weigh less but they are also shorter, possibly explaining their higher body mass index (BMI). More important, these findings are transient, with height differences dissipating by 14 years of age, and BMI differences by kindergarten. This information should train providers’ sights on optimal AD treatment and optimal nutritional and lifestyle support without undue concern for obesity or obesogenic behaviors.

Dr. Sidbury is chief of dermatology at Seattle Children's Hospital and professor, department of pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle. He is a site principal investigator for dupilumab trials, for which the hospital has a contract with Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

The , according to a large cohort study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

“The potential for ‘catch up’ in height for children with atopic dermatitis observed in our study may be explained with resolution of atopic dermatitis or successful treatment,” write senior author Aaron M. Drucker, MD, ScM, from the division of dermatology, University of Toronto, and Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, and colleagues. They postulated that, while the association between AD and shorter height is “is likely multifactorial,” it may be driven in part by sleep loss caused by AD, or corticosteroid treatment of AD, both of which can result in growth retardation and subsequent increased BMI.

The researchers used data from TARGet Kids!, a prospective, longitudinal cohort study designed to study multiple health conditions in children from general pediatric and family practices across Toronto. Their study included 10,611 children for whom there was data on height, weight, BMI, and standardized z scores, which account for age and sex differences in anthropometric characteristics. Clinically relevant covariates that were collected included child age, sex, birth weight, history of asthma, family income, maternal and paternal ethnicity, and maternal height and BMI.

The mean age of the children in the study at cohort entry was 23 months, and they were followed for a median of 28.5 months, during which time they had a median of two visits. At baseline, 947 (8.9%) children had parent-reported AD, with this number rising to 1,834 (17.3%) during follow-up.

After adjusting for covariates, AD was associated with lower mean z-height (P < .001), higher mean z-BMI (P = .008), but lower mean z-weight (P < .001), compared with children without AD. Using World Health Organization growth tables, the researchers estimated that “children with atopic dermatitis were, on average, approximately 0.5 cm shorter at age 2 years and 0.6 cm shorter at age 5 years than children without atopic dermatitis” after adjusting for covariates. They also estimated that children with AD were “on average, approximately 0.2 more BMI units at age 2 years” than children without AD. The associations between AD and height diminished by age 14 years, as did the association between AD and BMI by age 5.5 years.

“Given that we found children with atopic dermatitis to be somewhat less heavy, as measured by z-weight, than children without atopic dermatitis and that this association did not attenuate with age, it is possible that our findings for BMI, and perhaps those of previous studies, are explained mainly by differences in height,” the authors write. “This distinction has obvious clinical importance – rather than a focus on obesity and obesogenic behaviors being problematic in children with atopic dermatitis, research might be better directed at understanding the association between atopic dermatitis and initially shorter stature.”

Asked to comment on the study results, Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, told this news organization he would have preferred using the wording “in addition to focusing on obesity,” rather than “focus on obesity.”

“We should not ignore diet and sedentary activity as important factors,” he said, pointing to another recent study that found higher rates of eating disorders associated with AD.

Dr. Silverberg said that he was not familiar enough with the cohort sample to comment on how representative it is of the Canadian population, or on how generalizable the results are to other regions and populations. Generalizability, he added, “is an important issue, as we previously found regional differences with respect to the association between AD and obesity.”

In addition, he noted that in the study AD was defined as an “ever history” of disease rather than “in the past year or currently,” so, even though it is a longitudinal study, “it is really looking at how AD at any point in patients’ lives is related to weight or stature,” he explained. But, he added, “many cases of childhood AD ‘burn out’ or become milder/clear as the children get older. So, if the AD clears, then one would expect to see attenuation of associations as the children get older. However, this doesn’t tell us about how persistent AD into later childhood or adolescence is related to height or weight.”

Previous studies found that short stature and obesity were particularly associated with moderate – and even more to severe – atopic dermatitis, Dr. Silverberg said. It is likely that most patients in this primary care cohort had mild disease, he noted, so the effect sizes are likely diluted by mostly mild disease “and not relevant to the more persistent and severe AD patients encountered in the dermatology practice setting.”

The study was supported by the department of medicine, Women’s College Hospital, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

One author reported receiving compensation from the British Journal of Dermatology, the American Academy of Dermatology, and the National Eczema Association and has served as a paid consultant for the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Silverberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH

Among the more puzzling “associations” to emerge in recent literature has been the association between atopic dermatitis (AD) and obesity. I see many children with severe AD every day and my gestalt “association” is a thinner, shorter child rather than an overweight one. Dr. Drucker and colleagues’ data has helped me understand this dissonance. Children with AD do in fact, on average, weigh less but they are also shorter, possibly explaining their higher body mass index (BMI). More important, these findings are transient, with height differences dissipating by 14 years of age, and BMI differences by kindergarten. This information should train providers’ sights on optimal AD treatment and optimal nutritional and lifestyle support without undue concern for obesity or obesogenic behaviors.

Dr. Sidbury is chief of dermatology at Seattle Children's Hospital and professor, department of pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle. He is a site principal investigator for dupilumab trials, for which the hospital has a contract with Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

The , according to a large cohort study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

“The potential for ‘catch up’ in height for children with atopic dermatitis observed in our study may be explained with resolution of atopic dermatitis or successful treatment,” write senior author Aaron M. Drucker, MD, ScM, from the division of dermatology, University of Toronto, and Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, and colleagues. They postulated that, while the association between AD and shorter height is “is likely multifactorial,” it may be driven in part by sleep loss caused by AD, or corticosteroid treatment of AD, both of which can result in growth retardation and subsequent increased BMI.

The researchers used data from TARGet Kids!, a prospective, longitudinal cohort study designed to study multiple health conditions in children from general pediatric and family practices across Toronto. Their study included 10,611 children for whom there was data on height, weight, BMI, and standardized z scores, which account for age and sex differences in anthropometric characteristics. Clinically relevant covariates that were collected included child age, sex, birth weight, history of asthma, family income, maternal and paternal ethnicity, and maternal height and BMI.

The mean age of the children in the study at cohort entry was 23 months, and they were followed for a median of 28.5 months, during which time they had a median of two visits. At baseline, 947 (8.9%) children had parent-reported AD, with this number rising to 1,834 (17.3%) during follow-up.

After adjusting for covariates, AD was associated with lower mean z-height (P < .001), higher mean z-BMI (P = .008), but lower mean z-weight (P < .001), compared with children without AD. Using World Health Organization growth tables, the researchers estimated that “children with atopic dermatitis were, on average, approximately 0.5 cm shorter at age 2 years and 0.6 cm shorter at age 5 years than children without atopic dermatitis” after adjusting for covariates. They also estimated that children with AD were “on average, approximately 0.2 more BMI units at age 2 years” than children without AD. The associations between AD and height diminished by age 14 years, as did the association between AD and BMI by age 5.5 years.

“Given that we found children with atopic dermatitis to be somewhat less heavy, as measured by z-weight, than children without atopic dermatitis and that this association did not attenuate with age, it is possible that our findings for BMI, and perhaps those of previous studies, are explained mainly by differences in height,” the authors write. “This distinction has obvious clinical importance – rather than a focus on obesity and obesogenic behaviors being problematic in children with atopic dermatitis, research might be better directed at understanding the association between atopic dermatitis and initially shorter stature.”

Asked to comment on the study results, Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, told this news organization he would have preferred using the wording “in addition to focusing on obesity,” rather than “focus on obesity.”

“We should not ignore diet and sedentary activity as important factors,” he said, pointing to another recent study that found higher rates of eating disorders associated with AD.

Dr. Silverberg said that he was not familiar enough with the cohort sample to comment on how representative it is of the Canadian population, or on how generalizable the results are to other regions and populations. Generalizability, he added, “is an important issue, as we previously found regional differences with respect to the association between AD and obesity.”

In addition, he noted that in the study AD was defined as an “ever history” of disease rather than “in the past year or currently,” so, even though it is a longitudinal study, “it is really looking at how AD at any point in patients’ lives is related to weight or stature,” he explained. But, he added, “many cases of childhood AD ‘burn out’ or become milder/clear as the children get older. So, if the AD clears, then one would expect to see attenuation of associations as the children get older. However, this doesn’t tell us about how persistent AD into later childhood or adolescence is related to height or weight.”

Previous studies found that short stature and obesity were particularly associated with moderate – and even more to severe – atopic dermatitis, Dr. Silverberg said. It is likely that most patients in this primary care cohort had mild disease, he noted, so the effect sizes are likely diluted by mostly mild disease “and not relevant to the more persistent and severe AD patients encountered in the dermatology practice setting.”

The study was supported by the department of medicine, Women’s College Hospital, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

One author reported receiving compensation from the British Journal of Dermatology, the American Academy of Dermatology, and the National Eczema Association and has served as a paid consultant for the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Silverberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH

Among the more puzzling “associations” to emerge in recent literature has been the association between atopic dermatitis (AD) and obesity. I see many children with severe AD every day and my gestalt “association” is a thinner, shorter child rather than an overweight one. Dr. Drucker and colleagues’ data has helped me understand this dissonance. Children with AD do in fact, on average, weigh less but they are also shorter, possibly explaining their higher body mass index (BMI). More important, these findings are transient, with height differences dissipating by 14 years of age, and BMI differences by kindergarten. This information should train providers’ sights on optimal AD treatment and optimal nutritional and lifestyle support without undue concern for obesity or obesogenic behaviors.

Dr. Sidbury is chief of dermatology at Seattle Children's Hospital and professor, department of pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle. He is a site principal investigator for dupilumab trials, for which the hospital has a contract with Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Fauci: Omicron ‘very different from other variants’

The newly detected Omicron COVID-19 variant may be highly infectious and less responsive to available vaccines than other variants, but it is too early to know how it compares to the Delta variant, top infectious disease official Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said Nov. 30.

Dr. Fauci, speaking at a White House COVID-19 briefing, said there’s a “very unusual constellation of changes” across the COVID-19 genome that indicates it is unlike any variant we have seen so far.

“This mutational profile is very different from other variants of interest and concern, and although some mutations are also found in Delta, this is not Delta,” Dr. Fauci said. “These mutations have been associated with increased transmissibility and immune evasion.”

Omicron is the fifth designated COVID-19 variant of concern.

Detected first in South Africa, Omicron has been found in 20 countries so far. There are no known cases yet in the United States, but it has been detected in Canada.

Omicron has more than 30 mutations to the spike protein, the part of the virus that binds to human cells, Dr. Fauci said.

Cross-protection from boosters

Though the mutations suggest there is increased transmission of this variant, he said it is too soon to know how this compares to the Delta variant. And although the vaccines may not be as effective against Omicron, Dr. Fauci said there will likely be some protection.

“Remember, as with other variants, although partial immune escape may occur, vaccines, particularly boosters, give a level of antibodies that even with variants like Delta give you a degree of cross-protection, particularly against severe disease,” he said.

“When we say that although these mutations suggest a diminution of protection and a degree of immune evasion, we still, from experience with Delta, can make a reasonable conclusion that you would not eliminate all protection against this particular variant,” Dr. Fauci said.

So far, there is no reason to believe Omicron will cause more severe illness than other variants of concern.

“Although some preliminary information from South Africa suggests no unusual symptoms associated with variant, we do not know, and it is too early to tell,” Dr. Fauci said.

He recommended that people continue to wear masks, wash hands, and avoid crowded indoor venues. Most importantly, he recommended that everyone get their vaccines and boosters.

“One thing has become clear over the last 20 months: We can’t predict the future, but we can be prepared for it,” CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, said at the briefing. “We have far more tools to fight the variant today than we did at this time last year.”

A version of this story first appeared on Medscape.com.

The newly detected Omicron COVID-19 variant may be highly infectious and less responsive to available vaccines than other variants, but it is too early to know how it compares to the Delta variant, top infectious disease official Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said Nov. 30.

Dr. Fauci, speaking at a White House COVID-19 briefing, said there’s a “very unusual constellation of changes” across the COVID-19 genome that indicates it is unlike any variant we have seen so far.

“This mutational profile is very different from other variants of interest and concern, and although some mutations are also found in Delta, this is not Delta,” Dr. Fauci said. “These mutations have been associated with increased transmissibility and immune evasion.”

Omicron is the fifth designated COVID-19 variant of concern.

Detected first in South Africa, Omicron has been found in 20 countries so far. There are no known cases yet in the United States, but it has been detected in Canada.

Omicron has more than 30 mutations to the spike protein, the part of the virus that binds to human cells, Dr. Fauci said.

Cross-protection from boosters

Though the mutations suggest there is increased transmission of this variant, he said it is too soon to know how this compares to the Delta variant. And although the vaccines may not be as effective against Omicron, Dr. Fauci said there will likely be some protection.

“Remember, as with other variants, although partial immune escape may occur, vaccines, particularly boosters, give a level of antibodies that even with variants like Delta give you a degree of cross-protection, particularly against severe disease,” he said.

“When we say that although these mutations suggest a diminution of protection and a degree of immune evasion, we still, from experience with Delta, can make a reasonable conclusion that you would not eliminate all protection against this particular variant,” Dr. Fauci said.

So far, there is no reason to believe Omicron will cause more severe illness than other variants of concern.

“Although some preliminary information from South Africa suggests no unusual symptoms associated with variant, we do not know, and it is too early to tell,” Dr. Fauci said.

He recommended that people continue to wear masks, wash hands, and avoid crowded indoor venues. Most importantly, he recommended that everyone get their vaccines and boosters.

“One thing has become clear over the last 20 months: We can’t predict the future, but we can be prepared for it,” CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, said at the briefing. “We have far more tools to fight the variant today than we did at this time last year.”

A version of this story first appeared on Medscape.com.

The newly detected Omicron COVID-19 variant may be highly infectious and less responsive to available vaccines than other variants, but it is too early to know how it compares to the Delta variant, top infectious disease official Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said Nov. 30.

Dr. Fauci, speaking at a White House COVID-19 briefing, said there’s a “very unusual constellation of changes” across the COVID-19 genome that indicates it is unlike any variant we have seen so far.

“This mutational profile is very different from other variants of interest and concern, and although some mutations are also found in Delta, this is not Delta,” Dr. Fauci said. “These mutations have been associated with increased transmissibility and immune evasion.”

Omicron is the fifth designated COVID-19 variant of concern.

Detected first in South Africa, Omicron has been found in 20 countries so far. There are no known cases yet in the United States, but it has been detected in Canada.

Omicron has more than 30 mutations to the spike protein, the part of the virus that binds to human cells, Dr. Fauci said.

Cross-protection from boosters

Though the mutations suggest there is increased transmission of this variant, he said it is too soon to know how this compares to the Delta variant. And although the vaccines may not be as effective against Omicron, Dr. Fauci said there will likely be some protection.

“Remember, as with other variants, although partial immune escape may occur, vaccines, particularly boosters, give a level of antibodies that even with variants like Delta give you a degree of cross-protection, particularly against severe disease,” he said.

“When we say that although these mutations suggest a diminution of protection and a degree of immune evasion, we still, from experience with Delta, can make a reasonable conclusion that you would not eliminate all protection against this particular variant,” Dr. Fauci said.

So far, there is no reason to believe Omicron will cause more severe illness than other variants of concern.

“Although some preliminary information from South Africa suggests no unusual symptoms associated with variant, we do not know, and it is too early to tell,” Dr. Fauci said.

He recommended that people continue to wear masks, wash hands, and avoid crowded indoor venues. Most importantly, he recommended that everyone get their vaccines and boosters.

“One thing has become clear over the last 20 months: We can’t predict the future, but we can be prepared for it,” CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, said at the briefing. “We have far more tools to fight the variant today than we did at this time last year.”

A version of this story first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA panel backs first pill for COVID-19 by a small margin

, according to a panel of experts that advises the Food and Drug Administration on its regulatory decisions for these types of drugs.

The FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee narrowly voted to authorize the drug molnupiravir, voting 13 to 10 to support emergency use, which requires a medication to meet a lower standard of evidence than does full approval.

The FDA is not bound by the committee’s vote but typically follows its advice.

If authorized by the agency, molnupiravir would be the first antiviral agent available as a pill to treat COVID-19. Other therapies to treat the infection are available — monoclonal antibodies and the drug remdesivir — but they are given by infusion.

The United Kingdom has already authorized the use of Merck’s drug.

“This was clearly a difficult decision,” said committee member Michael Green, MD, a pediatric infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburg School of Medicine.

Green said he voted yes, and that the drug’s ability to prevent deaths in the study weighed heavily on his decision. He said given uncertainties around the drug both the company and FDA should keep a close eye on patients taking the drug going forward.

“Should an alternative oral agent become available that had a better safety profile and equal or better efficacy profile, the agency might reconsider its authorization,” he said.

Others didn’t agree that the drug should be allowed onto the market.

“I voted no,” said Jennifer Le, PharmD, a professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of California. Dr. Le said the modest benefit of the medication didn’t outweigh all the potential safety issues. “I think I just need more efficacy and safety data,” she said.

Initial results from the first half of people enrolled in the clinical trial found the pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 50% in patients at higher risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19.

But later results, released just days before the meeting, showed that the drug’s effectiveness had dropped to about 30%.

In the updated analysis, 48 patients out of the 709 who were taking the drug were hospitalized or died within 29 days compared to 68 out of 699 who randomly got the placebo. There was one death in the group that got molnupiravir compared to nine in the placebo group. Nearly all those deaths occurred during the first phase of the study.

On Nov. 30 Merck explained that the drug’s efficacy appeared to fall, in part, because the placebo group had experienced fewer hospitalizations and deaths than expected during the second half of the study, making the drug look less beneficial by comparison.

The company said it wasn’t sure why patients in the placebo group had fared so much better in later trial enrollments.

“The efficacy of this product is not overwhelmingly good,” said committee member David Hardy, MD, an infectious disease expert at Charles Drew University School of Medicine in Los Angeles. “And I think that makes all of us a little uncomfortable about whether this is an advanced therapeutic because it’s an oral medication rather than an intravenous medication,” he said during the panel’s deliberations.

“I think we have to be very careful about how we’re going to allow people to use this,” Dr. Hardy said.

Many who voted for authorization thought use of the drug should be restricted to unvaccinated people who were at high risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes, the same population enrolled in the clinical trial. People in the trial were considered at higher risk if they were over age 60, had cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were obese, or had heart disease or diabetes.

There are some significant limitations of the study that may affect how the drug is used. Vaccinated people couldn’t enroll in the study, so it’s not known if the medication would have any benefit for them. Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population is fully vaccinated. The study found no additional benefit of the medication compared to the placebo in people who had detectable antibodies, presumably from a prior infection.

Animal studies found that the drug — which kills the virus by forcing it to make errors as it copies its genetic material inside cells — could disrupt bone formation. For that reason, the manufacturer and the FDA agreed that it should not be used in anyone younger than age 18.

Animal studies also indicated that the drug could cause birth defects. For that reason, the company said the drug shouldn’t be given to women who are pregnant or breastfeeding and said doctors should make sure women of childbearing age aren’t pregnant before taking the medication.

Some members of the panel felt that pregnant women and their doctors should be given the choice of whether or not to use the drug, given that pregnant women are at high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and infused therapies may not be available in all settings.

Other members of the committee said they were uncomfortable authorizing the drug given its potential to mutate the virus.

The drug, which forces the virus to mutate as it copies its RNA, eventually causes the virus to make so many errors in its genetic material that it can no longer make more of itself and the immune system clears it out of the body.

But it takes a few days to work — the drug is designed to be taken for 5 consecutive days -- and studies of the viral loads of patients taking the drug show that through the first 2 days, viral loads remain detectable as these mutations occur.

Studies by the FDA show some of those mutations in the spike protein are the same ones that have helped the virus become more transmissible and escape the protection of vaccines.

So the question is whether someone taking the medication could develop a dangerous mutation and then infect someone else, sparking the spread of a new variant.

Nicholas Kartsonis, MD, a vice president at Merck, said that the company was still analyzing data.

“Even if the probability is very low — 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100,000 -- that this drug would induce an escape mutant for which the vaccines we have would not cover, that would be catastrophic for the whole world, actually,” said committee member James Hildreth, MD, an immunologist and president of Meharry Medical College, Nashville. “Do you have sufficient data on the likelihood of that happening?” he asked Dr. Kartsonis of Merck.

“So we don’t,” Dr. Kartsonis said.

He said, in theory, the risk of mutation with molnupiravir is the same as seen with the use of vaccines or monoclonal antibody therapies. Dr. Hildreth wasn’t satisfied with that answer.

“With all respect, the mechanism of your drug is to drive [genetic mutations], so it’s not the same as the vaccine. It’s not the same as monoclonal antibodies,” he said.

Dr. Hildreth later said he didn’t feel comfortable voting for authorization given the uncertainties around escape mutants. He voted no.

“It was an easy vote for me,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a panel of experts that advises the Food and Drug Administration on its regulatory decisions for these types of drugs.

The FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee narrowly voted to authorize the drug molnupiravir, voting 13 to 10 to support emergency use, which requires a medication to meet a lower standard of evidence than does full approval.

The FDA is not bound by the committee’s vote but typically follows its advice.

If authorized by the agency, molnupiravir would be the first antiviral agent available as a pill to treat COVID-19. Other therapies to treat the infection are available — monoclonal antibodies and the drug remdesivir — but they are given by infusion.

The United Kingdom has already authorized the use of Merck’s drug.

“This was clearly a difficult decision,” said committee member Michael Green, MD, a pediatric infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburg School of Medicine.

Green said he voted yes, and that the drug’s ability to prevent deaths in the study weighed heavily on his decision. He said given uncertainties around the drug both the company and FDA should keep a close eye on patients taking the drug going forward.

“Should an alternative oral agent become available that had a better safety profile and equal or better efficacy profile, the agency might reconsider its authorization,” he said.

Others didn’t agree that the drug should be allowed onto the market.

“I voted no,” said Jennifer Le, PharmD, a professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of California. Dr. Le said the modest benefit of the medication didn’t outweigh all the potential safety issues. “I think I just need more efficacy and safety data,” she said.

Initial results from the first half of people enrolled in the clinical trial found the pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 50% in patients at higher risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19.

But later results, released just days before the meeting, showed that the drug’s effectiveness had dropped to about 30%.

In the updated analysis, 48 patients out of the 709 who were taking the drug were hospitalized or died within 29 days compared to 68 out of 699 who randomly got the placebo. There was one death in the group that got molnupiravir compared to nine in the placebo group. Nearly all those deaths occurred during the first phase of the study.

On Nov. 30 Merck explained that the drug’s efficacy appeared to fall, in part, because the placebo group had experienced fewer hospitalizations and deaths than expected during the second half of the study, making the drug look less beneficial by comparison.

The company said it wasn’t sure why patients in the placebo group had fared so much better in later trial enrollments.

“The efficacy of this product is not overwhelmingly good,” said committee member David Hardy, MD, an infectious disease expert at Charles Drew University School of Medicine in Los Angeles. “And I think that makes all of us a little uncomfortable about whether this is an advanced therapeutic because it’s an oral medication rather than an intravenous medication,” he said during the panel’s deliberations.

“I think we have to be very careful about how we’re going to allow people to use this,” Dr. Hardy said.

Many who voted for authorization thought use of the drug should be restricted to unvaccinated people who were at high risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes, the same population enrolled in the clinical trial. People in the trial were considered at higher risk if they were over age 60, had cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were obese, or had heart disease or diabetes.

There are some significant limitations of the study that may affect how the drug is used. Vaccinated people couldn’t enroll in the study, so it’s not known if the medication would have any benefit for them. Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population is fully vaccinated. The study found no additional benefit of the medication compared to the placebo in people who had detectable antibodies, presumably from a prior infection.

Animal studies found that the drug — which kills the virus by forcing it to make errors as it copies its genetic material inside cells — could disrupt bone formation. For that reason, the manufacturer and the FDA agreed that it should not be used in anyone younger than age 18.

Animal studies also indicated that the drug could cause birth defects. For that reason, the company said the drug shouldn’t be given to women who are pregnant or breastfeeding and said doctors should make sure women of childbearing age aren’t pregnant before taking the medication.

Some members of the panel felt that pregnant women and their doctors should be given the choice of whether or not to use the drug, given that pregnant women are at high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and infused therapies may not be available in all settings.

Other members of the committee said they were uncomfortable authorizing the drug given its potential to mutate the virus.

The drug, which forces the virus to mutate as it copies its RNA, eventually causes the virus to make so many errors in its genetic material that it can no longer make more of itself and the immune system clears it out of the body.

But it takes a few days to work — the drug is designed to be taken for 5 consecutive days -- and studies of the viral loads of patients taking the drug show that through the first 2 days, viral loads remain detectable as these mutations occur.

Studies by the FDA show some of those mutations in the spike protein are the same ones that have helped the virus become more transmissible and escape the protection of vaccines.

So the question is whether someone taking the medication could develop a dangerous mutation and then infect someone else, sparking the spread of a new variant.

Nicholas Kartsonis, MD, a vice president at Merck, said that the company was still analyzing data.

“Even if the probability is very low — 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100,000 -- that this drug would induce an escape mutant for which the vaccines we have would not cover, that would be catastrophic for the whole world, actually,” said committee member James Hildreth, MD, an immunologist and president of Meharry Medical College, Nashville. “Do you have sufficient data on the likelihood of that happening?” he asked Dr. Kartsonis of Merck.

“So we don’t,” Dr. Kartsonis said.

He said, in theory, the risk of mutation with molnupiravir is the same as seen with the use of vaccines or monoclonal antibody therapies. Dr. Hildreth wasn’t satisfied with that answer.

“With all respect, the mechanism of your drug is to drive [genetic mutations], so it’s not the same as the vaccine. It’s not the same as monoclonal antibodies,” he said.

Dr. Hildreth later said he didn’t feel comfortable voting for authorization given the uncertainties around escape mutants. He voted no.

“It was an easy vote for me,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a panel of experts that advises the Food and Drug Administration on its regulatory decisions for these types of drugs.

The FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee narrowly voted to authorize the drug molnupiravir, voting 13 to 10 to support emergency use, which requires a medication to meet a lower standard of evidence than does full approval.

The FDA is not bound by the committee’s vote but typically follows its advice.

If authorized by the agency, molnupiravir would be the first antiviral agent available as a pill to treat COVID-19. Other therapies to treat the infection are available — monoclonal antibodies and the drug remdesivir — but they are given by infusion.

The United Kingdom has already authorized the use of Merck’s drug.

“This was clearly a difficult decision,” said committee member Michael Green, MD, a pediatric infectious disease expert at the University of Pittsburg School of Medicine.

Green said he voted yes, and that the drug’s ability to prevent deaths in the study weighed heavily on his decision. He said given uncertainties around the drug both the company and FDA should keep a close eye on patients taking the drug going forward.

“Should an alternative oral agent become available that had a better safety profile and equal or better efficacy profile, the agency might reconsider its authorization,” he said.

Others didn’t agree that the drug should be allowed onto the market.

“I voted no,” said Jennifer Le, PharmD, a professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of California. Dr. Le said the modest benefit of the medication didn’t outweigh all the potential safety issues. “I think I just need more efficacy and safety data,” she said.

Initial results from the first half of people enrolled in the clinical trial found the pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 50% in patients at higher risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19.

But later results, released just days before the meeting, showed that the drug’s effectiveness had dropped to about 30%.

In the updated analysis, 48 patients out of the 709 who were taking the drug were hospitalized or died within 29 days compared to 68 out of 699 who randomly got the placebo. There was one death in the group that got molnupiravir compared to nine in the placebo group. Nearly all those deaths occurred during the first phase of the study.

On Nov. 30 Merck explained that the drug’s efficacy appeared to fall, in part, because the placebo group had experienced fewer hospitalizations and deaths than expected during the second half of the study, making the drug look less beneficial by comparison.

The company said it wasn’t sure why patients in the placebo group had fared so much better in later trial enrollments.

“The efficacy of this product is not overwhelmingly good,” said committee member David Hardy, MD, an infectious disease expert at Charles Drew University School of Medicine in Los Angeles. “And I think that makes all of us a little uncomfortable about whether this is an advanced therapeutic because it’s an oral medication rather than an intravenous medication,” he said during the panel’s deliberations.

“I think we have to be very careful about how we’re going to allow people to use this,” Dr. Hardy said.

Many who voted for authorization thought use of the drug should be restricted to unvaccinated people who were at high risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes, the same population enrolled in the clinical trial. People in the trial were considered at higher risk if they were over age 60, had cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were obese, or had heart disease or diabetes.

There are some significant limitations of the study that may affect how the drug is used. Vaccinated people couldn’t enroll in the study, so it’s not known if the medication would have any benefit for them. Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population is fully vaccinated. The study found no additional benefit of the medication compared to the placebo in people who had detectable antibodies, presumably from a prior infection.

Animal studies found that the drug — which kills the virus by forcing it to make errors as it copies its genetic material inside cells — could disrupt bone formation. For that reason, the manufacturer and the FDA agreed that it should not be used in anyone younger than age 18.

Animal studies also indicated that the drug could cause birth defects. For that reason, the company said the drug shouldn’t be given to women who are pregnant or breastfeeding and said doctors should make sure women of childbearing age aren’t pregnant before taking the medication.

Some members of the panel felt that pregnant women and their doctors should be given the choice of whether or not to use the drug, given that pregnant women are at high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and infused therapies may not be available in all settings.

Other members of the committee said they were uncomfortable authorizing the drug given its potential to mutate the virus.

The drug, which forces the virus to mutate as it copies its RNA, eventually causes the virus to make so many errors in its genetic material that it can no longer make more of itself and the immune system clears it out of the body.

But it takes a few days to work — the drug is designed to be taken for 5 consecutive days -- and studies of the viral loads of patients taking the drug show that through the first 2 days, viral loads remain detectable as these mutations occur.

Studies by the FDA show some of those mutations in the spike protein are the same ones that have helped the virus become more transmissible and escape the protection of vaccines.

So the question is whether someone taking the medication could develop a dangerous mutation and then infect someone else, sparking the spread of a new variant.

Nicholas Kartsonis, MD, a vice president at Merck, said that the company was still analyzing data.

“Even if the probability is very low — 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100,000 -- that this drug would induce an escape mutant for which the vaccines we have would not cover, that would be catastrophic for the whole world, actually,” said committee member James Hildreth, MD, an immunologist and president of Meharry Medical College, Nashville. “Do you have sufficient data on the likelihood of that happening?” he asked Dr. Kartsonis of Merck.

“So we don’t,” Dr. Kartsonis said.

He said, in theory, the risk of mutation with molnupiravir is the same as seen with the use of vaccines or monoclonal antibody therapies. Dr. Hildreth wasn’t satisfied with that answer.

“With all respect, the mechanism of your drug is to drive [genetic mutations], so it’s not the same as the vaccine. It’s not the same as monoclonal antibodies,” he said.

Dr. Hildreth later said he didn’t feel comfortable voting for authorization given the uncertainties around escape mutants. He voted no.

“It was an easy vote for me,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study finds nadolol noninferior to propranolol for infantile hemangiomas

according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“In our experience, nadolol is preferable to propranolol given its observed efficacy and similar safety profile [and] its more predictable metabolism that does not involve the liver,” lead author Elena Pope, MD, told this news organization. “In addition, the fact that nadolol is less lipophilic than propranolol makes it less likely to cross the blood-brain barrier and potentially affect the central nervous system,” added Dr. Pope, who is head of the division of pediatric dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and professor of pediatric medicine at the University of Toronto.

The prospective double-blind, randomized noninferiority study was conducted between 2016 and 2020 at two tertiary academic pediatric dermatology clinics in Ontario, Canada. It included 71 infants with a corrected gestational age of 1-6 months whose hemangiomas were greater than 1.5 cm on the face or 3 cm or greater on another body part and had the potential to cause functional impairment or cosmetic disfigurement.

Patients were randomized to either nadolol (oral suspension, 10 mg/mL) or propranolol (oral suspension, 5 mg/mL) beginning at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg per day twice a day and titrated weekly by 0.5 mg/kg per day until the maximum dose of 2 mg/kg per day. The dose was then adjusted until week 24, based on patient weight and clinical response, after which parents could choose to continue the infant on the assigned medication or switch to the other one. Follow-up visits occurred every 2 months after that until week 52.

For the main study outcome, measured by visual analog scale (VAS) scores at week 24, the between-group differences of IH size and color from baseline were 8.8 and 17.1, respectively, in favor of the nadolol group, the researchers report, with similar results seen at week 52. Safety data were similar for both treatments, “demonstrating that nadolol was noninferior to propranolol,” they write.

Additionally, the mean size involution, compared with baseline was 97.9% in the nadolol group and 89.1% in the propranolol group, and the mean color fading was 94.5% in the nadolol group, compared with 80.5% in the propranolol group. During the study, nadolol was also “59% faster in achieving 75% shrinkage of IH, compared with propranolol (P = .02) and 105% faster in achieving 100% shrinkage (P = .07),” they add.

“A considerable portion of patients experienced at least one mild adverse event (77.1% vs. 94.4% at 0-24 weeks and 84.2% vs. 74.2% at 24-52 weeks in the nadolol group vs. the propranolol group, respectively), with a median of two in each intervention group,” they noted, adding that while these numbers are high, they are similar to those in previous clinical trials.

“The efficacy data coupled with a more predictable pharmacokinetic profile and lower chance of crossing the blood-brain barrier may make nadolol a favorable alternative intervention in patients with IHs,” the authors conclude. However, they add that “further studies are needed to prove superiority over propranolol.”

Asked to comment on the results, Ilona J. Frieden, MD, director of the Birthmarks & Vascular Anomalies Center at the University of California, San Francisco, said that while this is a “very interesting study and deserves further consideration,” the findings do not reach the level at which they would change guidelines. “The vast majority of patients being treated with a systemic medication for IH are in fact getting propranolol,” said Dr. Frieden, coauthor of the American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas.

“Though this study – designed as a noninferiority study – does seem to show slightly better outcomes from nadolol versus propranolol … it is a relatively small study,” she told this news organization. “Infantile hemangiomas are a very heterogeneous group, and larger studies and longer-term outcome data would be needed to truly compare the two modalities of treatment.”

Concern over the safety of nadolol was raised in a case report published in Pediatrics, which described the death of a 10-week-old girl 7 weeks after starting nadolol for IH. The infant was found to have an elevated postmortem cardiac blood nadolol level of 0.94 mg/L. “Although we debated the conclusion of that report in terms of death attribution to nadolol, one practical pearl is to instruct the parents to discontinue nadolol if the baby has no bowel movements for more than 3 days,” Dr. Pope advised.

The author of that case report, Eric McGillis, MD, program director of clinical pharmacology and toxicology and an emergency physician at Alberta Health Services, in Calgary, Alt., said the conclusion of his report has been taken out of context. “We acknowledge that our case report, like any case report, cannot prove causation,” he told this news organization. “We hypothesized that nadolol may have contributed to the death of the infant based on the limited pharmacokinetic data currently available for nadolol in infants. Nadolol is largely eliminated in the feces and infants may have infrequent stooling based on diet and other factors; therefore, nadolol may accumulate,” he noted.

The infant in the case report did not have a bowel movement for 10 days “and had an elevated postmortem cardiac nadolol concentration in the absence of another obvious cause of death. More pharmacokinetic studies on nadolol in this population are needed to substantiate our hypothesis. However, in the meantime, we agree that having parents monitor stool output for dose adjustments makes practical sense and can potentially reduce harm.”

Dr. Pope presented the results of the study earlier this year at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

The study was supported by Physician Services, Ont. Dr. Pope has reported serving as an advisory board member for Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, and Timber. Other authors have reported receiving personal fees from Pierre Fabre during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees from Amgen, Ipsen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi Genzyme; grants from AbbVie, Clementia, Mayne Pharma, and Sanofi Genzyme; and grants and personal fees from Venthera. One author has a patent for a new topical treatment of IH. Dr. Frieden has reported being a consultant for Pfizer (data safety board), Novartis, and Venthera. Dr. McGillis has reported no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Lawrence W. Eichenfield, MD

The treatment of functionally significant and deforming hemangiomas has been revolutionized by propranolol, developed after the observation by Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, that a child who developed hypertension as a side effect of systemic steroids for a nasal hemangioma and was prescribed propranolol for the hypertension had rapid shrinkage of the hemangioma. The study by Pope and colleagues assesses nadolol as an alternative to propranolol, showing noninferiority and in some parameters improved outcomes and speed of response. The drug appeared to be fairly well tolerated in the study, though there is a prior published case report of a death from nadolol use for hemangioma treatment from a different Canadian center. Nadolol may be an important alternative to propranolol; however, propranolol remains the only FDA-approved medication for infantile hemangiomas and the generally recommended medication in the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for management of infantile hemangiomas.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. He disclosed that he has served as an investigator and/or consultant to AbbVie, Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“In our experience, nadolol is preferable to propranolol given its observed efficacy and similar safety profile [and] its more predictable metabolism that does not involve the liver,” lead author Elena Pope, MD, told this news organization. “In addition, the fact that nadolol is less lipophilic than propranolol makes it less likely to cross the blood-brain barrier and potentially affect the central nervous system,” added Dr. Pope, who is head of the division of pediatric dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and professor of pediatric medicine at the University of Toronto.

The prospective double-blind, randomized noninferiority study was conducted between 2016 and 2020 at two tertiary academic pediatric dermatology clinics in Ontario, Canada. It included 71 infants with a corrected gestational age of 1-6 months whose hemangiomas were greater than 1.5 cm on the face or 3 cm or greater on another body part and had the potential to cause functional impairment or cosmetic disfigurement.

Patients were randomized to either nadolol (oral suspension, 10 mg/mL) or propranolol (oral suspension, 5 mg/mL) beginning at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg per day twice a day and titrated weekly by 0.5 mg/kg per day until the maximum dose of 2 mg/kg per day. The dose was then adjusted until week 24, based on patient weight and clinical response, after which parents could choose to continue the infant on the assigned medication or switch to the other one. Follow-up visits occurred every 2 months after that until week 52.