User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

A focus on women with diabetes and their offspring

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

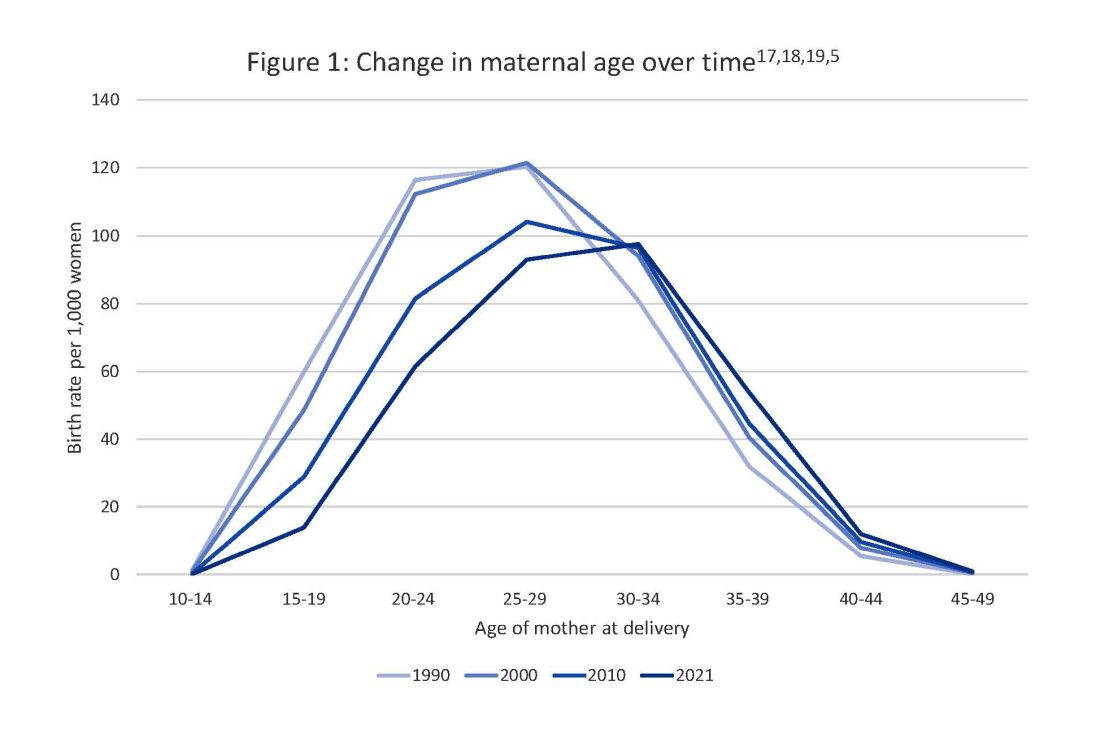

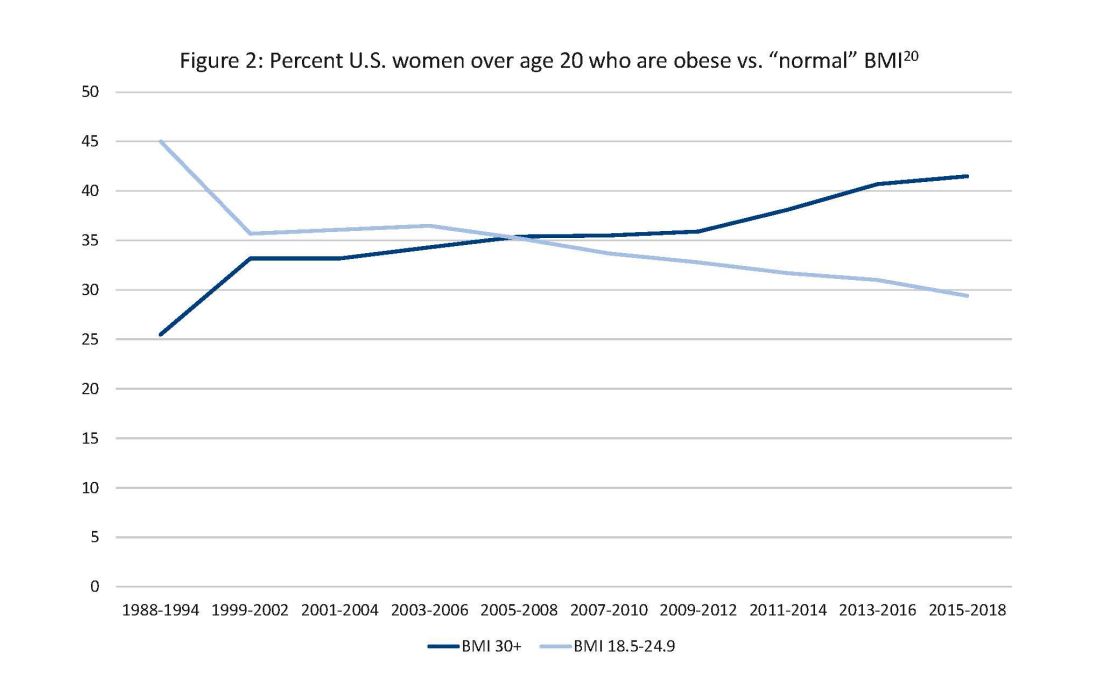

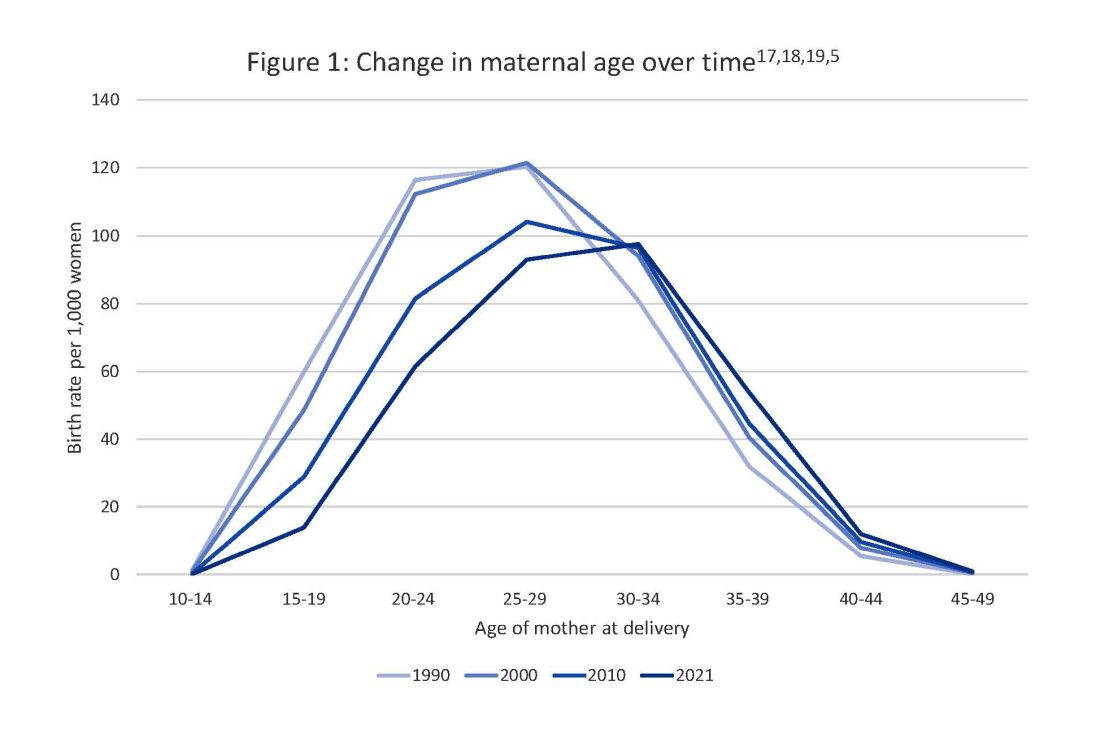

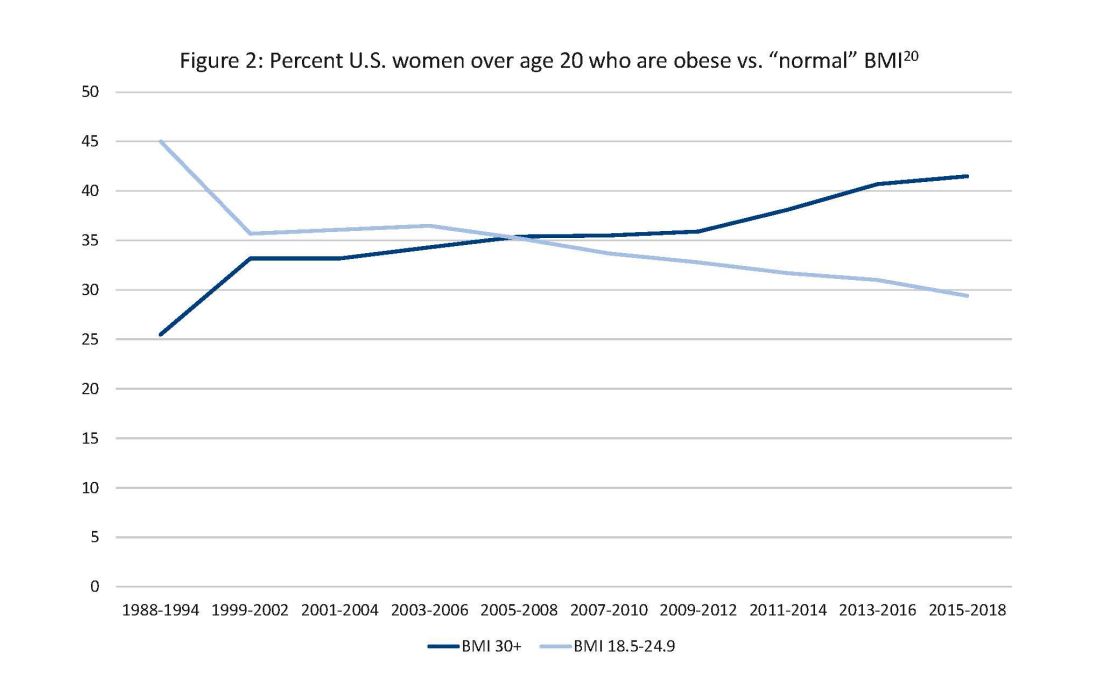

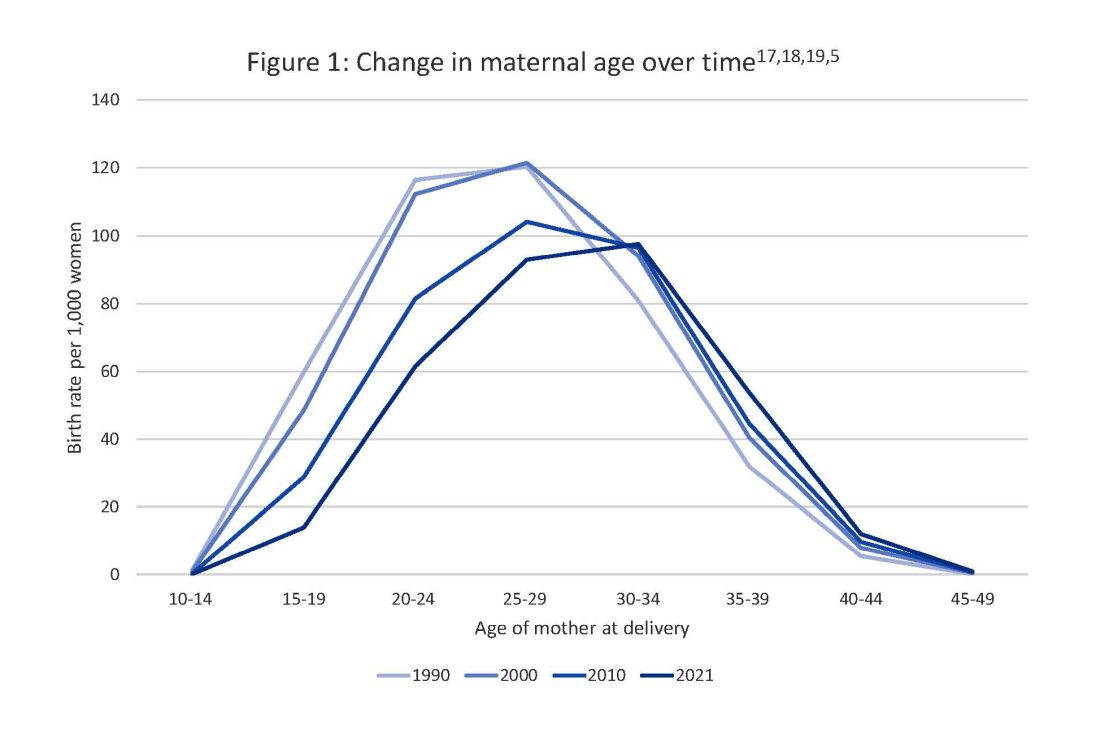

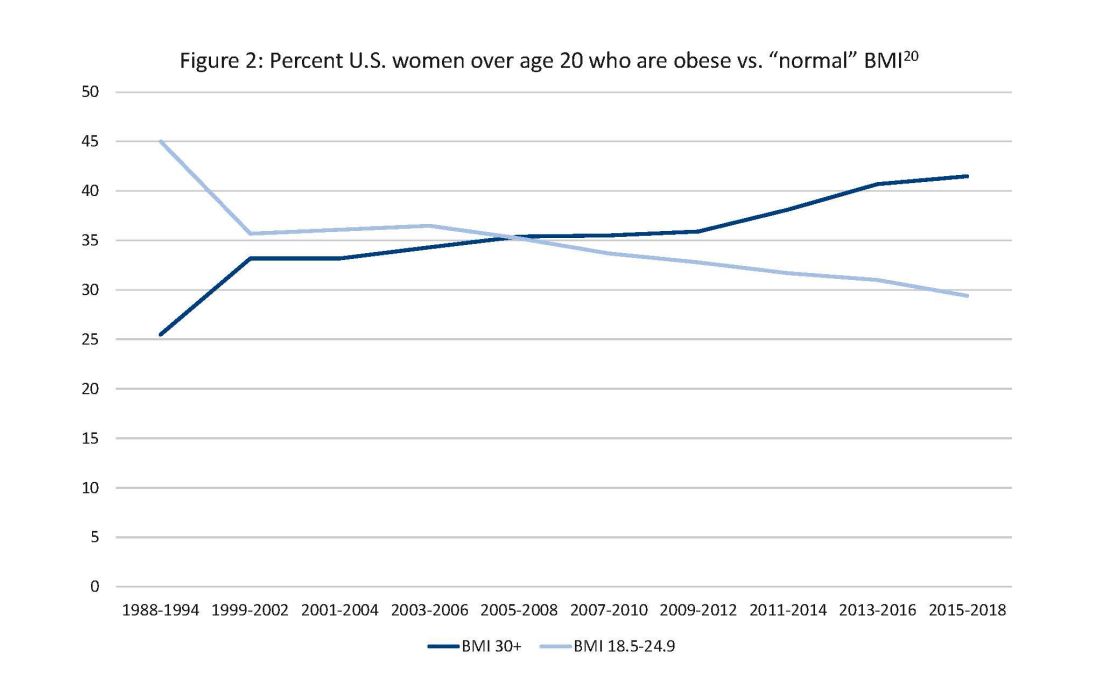

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.

5. Osterman MJK et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. PMID: 36723449.

6. Gregory ECW and Ely DM. Trends and characteristics in prepregnancy diabetes: United States, 2016-2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 May;72(6):1-13. PMID: 37256333.

7. QuickStats: Percentage of mothers with gestational diabetes, by maternal age – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Jan 6;72(1):16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a4.

8. Langer O et al. The Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America – Introduction and summary statement. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3(6):514-6.

9. Willhoite MB et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes. The experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993 Feb;16(2):450-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450.

10. McElvy SS et al. A focused preconceptional and early pregnancy program in women with type 1 diabetes reduces perinatal mortality and malformation rates to general population levels. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<14::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-K.

11. Rosen JA et al. The history and contributions of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (1997-2015). Am J Perinatol. 2016 Nov;33(13):1223-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1585082.

12. Driggers RW and Baschat A. The 12th meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA): Introduction and overview. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):3-4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.626917.

13. Langer O et al. The proceedings of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America 2009 conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Mar;23(3):196-8. doi: 10.3109/14767050903550634.

14. Reece EA et al. A consensus report of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America Conference, Little Rock, Ark., May 2002. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):362-4. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.362.364.

15. Reece EA and Maulik D. A consensus conference of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):361. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.361.361.

16. Gabbe SG. Summation of the second meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA). J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):3-9.

17. Vital Statistics of the United States 1990: Volume I – Natality.

18. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Feb 12;50(5):1-101. PMID: 11876093.

19. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012 Aug 28;61(1):1-72. PMID: 24974589.

20. CDC Website. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States.

21. Wang Y et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Jun 1;49(3):810-23. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273.

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.

5. Osterman MJK et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. PMID: 36723449.

6. Gregory ECW and Ely DM. Trends and characteristics in prepregnancy diabetes: United States, 2016-2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 May;72(6):1-13. PMID: 37256333.

7. QuickStats: Percentage of mothers with gestational diabetes, by maternal age – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Jan 6;72(1):16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a4.

8. Langer O et al. The Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America – Introduction and summary statement. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3(6):514-6.

9. Willhoite MB et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes. The experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993 Feb;16(2):450-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450.

10. McElvy SS et al. A focused preconceptional and early pregnancy program in women with type 1 diabetes reduces perinatal mortality and malformation rates to general population levels. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<14::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-K.

11. Rosen JA et al. The history and contributions of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (1997-2015). Am J Perinatol. 2016 Nov;33(13):1223-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1585082.

12. Driggers RW and Baschat A. The 12th meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA): Introduction and overview. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):3-4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.626917.

13. Langer O et al. The proceedings of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America 2009 conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Mar;23(3):196-8. doi: 10.3109/14767050903550634.

14. Reece EA et al. A consensus report of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America Conference, Little Rock, Ark., May 2002. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):362-4. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.362.364.

15. Reece EA and Maulik D. A consensus conference of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):361. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.361.361.

16. Gabbe SG. Summation of the second meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA). J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):3-9.

17. Vital Statistics of the United States 1990: Volume I – Natality.

18. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Feb 12;50(5):1-101. PMID: 11876093.

19. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012 Aug 28;61(1):1-72. PMID: 24974589.

20. CDC Website. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States.

21. Wang Y et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Jun 1;49(3):810-23. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273.

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.

5. Osterman MJK et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. PMID: 36723449.

6. Gregory ECW and Ely DM. Trends and characteristics in prepregnancy diabetes: United States, 2016-2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 May;72(6):1-13. PMID: 37256333.

7. QuickStats: Percentage of mothers with gestational diabetes, by maternal age – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Jan 6;72(1):16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a4.

8. Langer O et al. The Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America – Introduction and summary statement. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3(6):514-6.

9. Willhoite MB et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes. The experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993 Feb;16(2):450-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450.

10. McElvy SS et al. A focused preconceptional and early pregnancy program in women with type 1 diabetes reduces perinatal mortality and malformation rates to general population levels. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<14::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-K.

11. Rosen JA et al. The history and contributions of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (1997-2015). Am J Perinatol. 2016 Nov;33(13):1223-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1585082.

12. Driggers RW and Baschat A. The 12th meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA): Introduction and overview. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):3-4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.626917.

13. Langer O et al. The proceedings of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America 2009 conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Mar;23(3):196-8. doi: 10.3109/14767050903550634.

14. Reece EA et al. A consensus report of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America Conference, Little Rock, Ark., May 2002. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):362-4. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.362.364.

15. Reece EA and Maulik D. A consensus conference of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):361. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.361.361.

16. Gabbe SG. Summation of the second meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA). J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):3-9.

17. Vital Statistics of the United States 1990: Volume I – Natality.

18. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Feb 12;50(5):1-101. PMID: 11876093.

19. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012 Aug 28;61(1):1-72. PMID: 24974589.

20. CDC Website. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States.

21. Wang Y et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Jun 1;49(3):810-23. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273.

Taking a new obesity drug and birth control pills? Be careful

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Employed physicians: A survival guide

The strike by health care workers at Kaiser Permanente may not involve physicians (yet). But as more doctors in the United States are finding themselves working as salaried employees, physicians can – and probably will – become a powerful force for change in a health care system that has shown itself to be increasingly hostile to employee concerns over issues involving patient care, wages and benefits, safety, and well-being.

Salaried employment has its challenges. Physician-employees may have less autonomy and voice in decision-making that affects patients. They may splinter into fragmented work groups; feel isolated; and have different imperatives based on who they are, what they want, and where they work. They may feel more removed from their patients and struggle to build strong relationships, with their employers in the way.

Yet important opportunities exist for doctors when embracing their employee side. Examples of these interests include adequate compensation, wellness, job security, patient and worker safety, health care quality, reasonable workloads and schedules, and fair treatment by employers, including the need to exhibit a strong collective voice in organizational decision-making.

Some believe that physician-employees must be unionized to maximize their rights and power as employees. Many expect physician unionization to take hold more fully over time. Medical residents, the doctors of tomorrow, are already considering unionization in greater numbers. Some are also doing it in the same employment setting alongside other health professionals, such as nurses.

Having studied doctors and their employment situations for years, I am convinced that whether through unionization or another approach, physicians must also change how they think about control; train and learn alongside other health care workers who share similar interests; and elevate at an early career stage their knowledge of the business side of health care.

Adopt a more pragmatic definition of autonomy

Doctors must embrace an updated definition of autonomy – one that matches their status as highly paid labor.

When I have spoken to physicians in my research about what autonomy means to them, many seem unable to reconceptualize it from a vague and absolute form of their profession’s strategic control over their economic fates and technical skills toward an individualized control that is situation-specific, one centered on winning the daily fights about workplace bread-and-butter issues such as those mentioned above.

But a more pragmatic definition of autonomy could get doctors focused on influencing important issues of the patient-care day and enhance their negotiating power with employers. It would allow physicians to break out of what often seems a paralysis of inaction – waiting for employers, insurers, or the government to reinstate the profession’s idealized version of control by handing it back the keys to the health care system through major regulatory, structural, and reimbursement-related changes. This fantasy is unlikely to become reality.

Physician-employees I’ve talked to over the years understand their everyday challenges. But when it comes to engaging in localized and sustained action to overcome them, they often perform less well, leading to feelings of helplessness and burnout. Valuing tactical control over their jobs and work setting will yield smaller but more impactful wins as employees intent on making their everyday work lives better.

Train alongside other health care professionals

Physicians must accept that how they are trained no longer prepares them for the employee world into which most are dropped. For instance, unless doctors are trained collaboratively alongside other health care professionals – such as nurses – they are less likely to identify closely with these colleagues once in practice. There is strength in numbers, so this mutual identification empowers both groups of employees. Yet, medical education remains largely the same: training young medical students in isolation for the first couple of years, then placing them into clerkships and residencies where true interprofessional care opportunities remain stunted and secondary to the “physician as captain of the team” mantra.

Unfortunately, the “hidden curriculum” of medicine helps convince medical students and residents early in their careers that they are the unquestioned leaders in patient care settings. This hierarchy encourages some doctors to keep their psychological distance from other members of the health care team and to resist sharing power, concerns, or insights with less skilled health care workers. This socialization harms the ability of physicians to act in a unified fashion alongside these other workers. Having physicians learn and train alongside other health professionals yields positive benefits for collective advocacy, including a shared sense of purpose, positive views on collaboration with others in the health setting, and greater development of bonds with nonphysician coworkers.

Integrate business with medical training in real time

Medical students and residents generally lack exposure to the everyday business realities of the U.S. health care system. This gap hinders their ability to understand the employee world and push for the types of changes and work conditions that benefit all health care workers. Formal business and management training should be a required part of every U.S. medical school and residency curriculum from day one. If you see it at all in medical schools now, it is mostly by accident, or given separate treatment in the form of standalone MBA or MPH degrees that rarely integrate organically and in real time with actual medical training. Not every doctor needs an MBA or MPH degree. However, all of them require a stronger contextual understanding of how the medicine they wish to practice is shaped by the economic and fiscal circumstances surrounding it – circumstances they do not control.

This is another reason why young doctors are unhappy and burned out. They cannot push for specific changes or properly critique the pros and cons of how their work is structured because they have not been made aware, in real time as they learn clinical practice, how their jobs are shaped by realities such as insurance coverage and reimbursement, the fragmentation of the care delivery system, their employer’s financial health , and the socioeconomic circumstances of their patients. They aren’t given the methods and tools related to process and quality improvement, budgeting, negotiation, risk management, leadership, and talent management that might help them navigate these undermining forces. They also get little advance exposure in their training to important workplace “soft” skills in such areas as how to work in teams, networking, communication and listening, empathy, and problem-solving – all necessary foci for bringing them closer to other health care workers and advocating alongside them effectively with health care employers.

Now is the time for physicians to embrace their identity as employees. Doing so is in their own best interest as professionals. It will help others in the health care workforce as well as patients. Moreover, it provides a needed counterbalance to the powerful corporate ethos now ascendant in U.S. health care.

Timothy Hoff, PhD, is a professor of management and healthcare systems at Northeastern University, Boston, and an associate fellow at the University of Oxford, England. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The strike by health care workers at Kaiser Permanente may not involve physicians (yet). But as more doctors in the United States are finding themselves working as salaried employees, physicians can – and probably will – become a powerful force for change in a health care system that has shown itself to be increasingly hostile to employee concerns over issues involving patient care, wages and benefits, safety, and well-being.

Salaried employment has its challenges. Physician-employees may have less autonomy and voice in decision-making that affects patients. They may splinter into fragmented work groups; feel isolated; and have different imperatives based on who they are, what they want, and where they work. They may feel more removed from their patients and struggle to build strong relationships, with their employers in the way.

Yet important opportunities exist for doctors when embracing their employee side. Examples of these interests include adequate compensation, wellness, job security, patient and worker safety, health care quality, reasonable workloads and schedules, and fair treatment by employers, including the need to exhibit a strong collective voice in organizational decision-making.

Some believe that physician-employees must be unionized to maximize their rights and power as employees. Many expect physician unionization to take hold more fully over time. Medical residents, the doctors of tomorrow, are already considering unionization in greater numbers. Some are also doing it in the same employment setting alongside other health professionals, such as nurses.

Having studied doctors and their employment situations for years, I am convinced that whether through unionization or another approach, physicians must also change how they think about control; train and learn alongside other health care workers who share similar interests; and elevate at an early career stage their knowledge of the business side of health care.

Adopt a more pragmatic definition of autonomy

Doctors must embrace an updated definition of autonomy – one that matches their status as highly paid labor.

When I have spoken to physicians in my research about what autonomy means to them, many seem unable to reconceptualize it from a vague and absolute form of their profession’s strategic control over their economic fates and technical skills toward an individualized control that is situation-specific, one centered on winning the daily fights about workplace bread-and-butter issues such as those mentioned above.

But a more pragmatic definition of autonomy could get doctors focused on influencing important issues of the patient-care day and enhance their negotiating power with employers. It would allow physicians to break out of what often seems a paralysis of inaction – waiting for employers, insurers, or the government to reinstate the profession’s idealized version of control by handing it back the keys to the health care system through major regulatory, structural, and reimbursement-related changes. This fantasy is unlikely to become reality.

Physician-employees I’ve talked to over the years understand their everyday challenges. But when it comes to engaging in localized and sustained action to overcome them, they often perform less well, leading to feelings of helplessness and burnout. Valuing tactical control over their jobs and work setting will yield smaller but more impactful wins as employees intent on making their everyday work lives better.

Train alongside other health care professionals

Physicians must accept that how they are trained no longer prepares them for the employee world into which most are dropped. For instance, unless doctors are trained collaboratively alongside other health care professionals – such as nurses – they are less likely to identify closely with these colleagues once in practice. There is strength in numbers, so this mutual identification empowers both groups of employees. Yet, medical education remains largely the same: training young medical students in isolation for the first couple of years, then placing them into clerkships and residencies where true interprofessional care opportunities remain stunted and secondary to the “physician as captain of the team” mantra.

Unfortunately, the “hidden curriculum” of medicine helps convince medical students and residents early in their careers that they are the unquestioned leaders in patient care settings. This hierarchy encourages some doctors to keep their psychological distance from other members of the health care team and to resist sharing power, concerns, or insights with less skilled health care workers. This socialization harms the ability of physicians to act in a unified fashion alongside these other workers. Having physicians learn and train alongside other health professionals yields positive benefits for collective advocacy, including a shared sense of purpose, positive views on collaboration with others in the health setting, and greater development of bonds with nonphysician coworkers.

Integrate business with medical training in real time

Medical students and residents generally lack exposure to the everyday business realities of the U.S. health care system. This gap hinders their ability to understand the employee world and push for the types of changes and work conditions that benefit all health care workers. Formal business and management training should be a required part of every U.S. medical school and residency curriculum from day one. If you see it at all in medical schools now, it is mostly by accident, or given separate treatment in the form of standalone MBA or MPH degrees that rarely integrate organically and in real time with actual medical training. Not every doctor needs an MBA or MPH degree. However, all of them require a stronger contextual understanding of how the medicine they wish to practice is shaped by the economic and fiscal circumstances surrounding it – circumstances they do not control.

This is another reason why young doctors are unhappy and burned out. They cannot push for specific changes or properly critique the pros and cons of how their work is structured because they have not been made aware, in real time as they learn clinical practice, how their jobs are shaped by realities such as insurance coverage and reimbursement, the fragmentation of the care delivery system, their employer’s financial health , and the socioeconomic circumstances of their patients. They aren’t given the methods and tools related to process and quality improvement, budgeting, negotiation, risk management, leadership, and talent management that might help them navigate these undermining forces. They also get little advance exposure in their training to important workplace “soft” skills in such areas as how to work in teams, networking, communication and listening, empathy, and problem-solving – all necessary foci for bringing them closer to other health care workers and advocating alongside them effectively with health care employers.

Now is the time for physicians to embrace their identity as employees. Doing so is in their own best interest as professionals. It will help others in the health care workforce as well as patients. Moreover, it provides a needed counterbalance to the powerful corporate ethos now ascendant in U.S. health care.

Timothy Hoff, PhD, is a professor of management and healthcare systems at Northeastern University, Boston, and an associate fellow at the University of Oxford, England. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The strike by health care workers at Kaiser Permanente may not involve physicians (yet). But as more doctors in the United States are finding themselves working as salaried employees, physicians can – and probably will – become a powerful force for change in a health care system that has shown itself to be increasingly hostile to employee concerns over issues involving patient care, wages and benefits, safety, and well-being.

Salaried employment has its challenges. Physician-employees may have less autonomy and voice in decision-making that affects patients. They may splinter into fragmented work groups; feel isolated; and have different imperatives based on who they are, what they want, and where they work. They may feel more removed from their patients and struggle to build strong relationships, with their employers in the way.

Yet important opportunities exist for doctors when embracing their employee side. Examples of these interests include adequate compensation, wellness, job security, patient and worker safety, health care quality, reasonable workloads and schedules, and fair treatment by employers, including the need to exhibit a strong collective voice in organizational decision-making.

Some believe that physician-employees must be unionized to maximize their rights and power as employees. Many expect physician unionization to take hold more fully over time. Medical residents, the doctors of tomorrow, are already considering unionization in greater numbers. Some are also doing it in the same employment setting alongside other health professionals, such as nurses.

Having studied doctors and their employment situations for years, I am convinced that whether through unionization or another approach, physicians must also change how they think about control; train and learn alongside other health care workers who share similar interests; and elevate at an early career stage their knowledge of the business side of health care.

Adopt a more pragmatic definition of autonomy

Doctors must embrace an updated definition of autonomy – one that matches their status as highly paid labor.

When I have spoken to physicians in my research about what autonomy means to them, many seem unable to reconceptualize it from a vague and absolute form of their profession’s strategic control over their economic fates and technical skills toward an individualized control that is situation-specific, one centered on winning the daily fights about workplace bread-and-butter issues such as those mentioned above.

But a more pragmatic definition of autonomy could get doctors focused on influencing important issues of the patient-care day and enhance their negotiating power with employers. It would allow physicians to break out of what often seems a paralysis of inaction – waiting for employers, insurers, or the government to reinstate the profession’s idealized version of control by handing it back the keys to the health care system through major regulatory, structural, and reimbursement-related changes. This fantasy is unlikely to become reality.

Physician-employees I’ve talked to over the years understand their everyday challenges. But when it comes to engaging in localized and sustained action to overcome them, they often perform less well, leading to feelings of helplessness and burnout. Valuing tactical control over their jobs and work setting will yield smaller but more impactful wins as employees intent on making their everyday work lives better.

Train alongside other health care professionals

Physicians must accept that how they are trained no longer prepares them for the employee world into which most are dropped. For instance, unless doctors are trained collaboratively alongside other health care professionals – such as nurses – they are less likely to identify closely with these colleagues once in practice. There is strength in numbers, so this mutual identification empowers both groups of employees. Yet, medical education remains largely the same: training young medical students in isolation for the first couple of years, then placing them into clerkships and residencies where true interprofessional care opportunities remain stunted and secondary to the “physician as captain of the team” mantra.

Unfortunately, the “hidden curriculum” of medicine helps convince medical students and residents early in their careers that they are the unquestioned leaders in patient care settings. This hierarchy encourages some doctors to keep their psychological distance from other members of the health care team and to resist sharing power, concerns, or insights with less skilled health care workers. This socialization harms the ability of physicians to act in a unified fashion alongside these other workers. Having physicians learn and train alongside other health professionals yields positive benefits for collective advocacy, including a shared sense of purpose, positive views on collaboration with others in the health setting, and greater development of bonds with nonphysician coworkers.

Integrate business with medical training in real time

Medical students and residents generally lack exposure to the everyday business realities of the U.S. health care system. This gap hinders their ability to understand the employee world and push for the types of changes and work conditions that benefit all health care workers. Formal business and management training should be a required part of every U.S. medical school and residency curriculum from day one. If you see it at all in medical schools now, it is mostly by accident, or given separate treatment in the form of standalone MBA or MPH degrees that rarely integrate organically and in real time with actual medical training. Not every doctor needs an MBA or MPH degree. However, all of them require a stronger contextual understanding of how the medicine they wish to practice is shaped by the economic and fiscal circumstances surrounding it – circumstances they do not control.

This is another reason why young doctors are unhappy and burned out. They cannot push for specific changes or properly critique the pros and cons of how their work is structured because they have not been made aware, in real time as they learn clinical practice, how their jobs are shaped by realities such as insurance coverage and reimbursement, the fragmentation of the care delivery system, their employer’s financial health , and the socioeconomic circumstances of their patients. They aren’t given the methods and tools related to process and quality improvement, budgeting, negotiation, risk management, leadership, and talent management that might help them navigate these undermining forces. They also get little advance exposure in their training to important workplace “soft” skills in such areas as how to work in teams, networking, communication and listening, empathy, and problem-solving – all necessary foci for bringing them closer to other health care workers and advocating alongside them effectively with health care employers.

Now is the time for physicians to embrace their identity as employees. Doing so is in their own best interest as professionals. It will help others in the health care workforce as well as patients. Moreover, it provides a needed counterbalance to the powerful corporate ethos now ascendant in U.S. health care.

Timothy Hoff, PhD, is a professor of management and healthcare systems at Northeastern University, Boston, and an associate fellow at the University of Oxford, England. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why legal pot makes this physician sick

Last year, my husband and I took a 16-day road trip from Kentucky through Massachusetts to Maine. On our first morning in Boston, we exited the Park Street Station en route to Boston Common, but instead of being greeted by the aroma of molasses, we were hit full-on with a pungent, repulsive odor. “That’s skunk weed,” my husband chuckled as we stepped right into the middle of the Boston Freedom Rally, a celebration of all things cannabis.

As we boarded a hop-on-hop-off bus, we learned that this was the one week of the year that the city skips testing tour bus drivers for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), “because we all test positive,” the driver quipped. As our open-air bus circled the Common, a crowd of pot enthusiasts displayed signs in support of relaxed regulation for public consumption.

The 34-year-old Boston Freedom Rally is a sign that U.S. culture has transformed forever. Mary Jane is no friend of emergency physicians nor of staff on hospital wards and offices.

Toking boomers and millennials

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego, looked at cannabis-related emergency department visits from all acute-care hospitals in the state from 2005 to 2019 and found an 1,808% increase in patients aged 65 or older (that is not a typo) who were there for complications from cannabis use.

The lead author said in an interview that, “older patients taking marijuana or related products may have dizziness and falls, heart palpitations, panic attacks, confusion, anxiety or worsening of underlying lung diseases, such as asthma or [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].”

A recent study from Canada suggests that commercialization has been associated with an increase in related hospitalizations, including cannabis-induced psychosis.

According to a National Study of Drug Use and Health, marijuana use in young adults reached an all-time high (pun intended) in 2021. Nearly 10% of eighth graders and 20% of 10th graders reported using marijuana this past year.

The full downside of any drug, legal or illegal, is largely unknown until it infiltrates the mainstream market, but these are the typical cases we see:

Let’s start with the demotivated high school honors student who dropped out of college to work at the local cinema. He stumbled and broke his clavicle outside a bar at 2 AM, but he wasn’t sure if he passed out, so a cardiology consult was requested to “rule out” arrhythmia associated with syncope. He related that his plan to become a railway conductor had been upended because he knew he would be drug tested and just couldn’t give up pot. After a normal cardiac exam, ECG, labs, a Holter, and an echocardiogram were also requested and normal at a significant cost.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

One of my Midwest colleagues related her encounter with two middle-aged pot users with ventricular tachycardia (VT). These episodes coincided with potassium levels less than 3.0 mEq/L in the setting of repetitive vomiting. The QTc interval didn’t normalize despite a corrected potassium level in one patient. They were both informed that they should never smoke pot because vomiting would predictably drop their K+ levels again and prolong their QTc intervals. Then began “the circular argument,” as my friend described it. The patient claims, “I smoke pot to relieve my nausea,” to which she explains that “in many folks, pot use induces nausea.” Of course, the classic reply is, “Not me.” Predictably one of these stoners soon returned with more VT, more puking, and more hypokalemia. “Consider yourself ‘allergic’ to pot smoke,” my friend advised, but “was met with no meaningful hint of understanding or hope for transformative change,” she told me.

I’ve seen cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome several times in the past few years. It occurs in daily to weekly pot users. Very rarely, it can cause cerebral edema, but it is also associated with seizures and dehydration that can lead to hypovolemic shock and kidney failure.

Heart and brain harm

Then there are the young patients who for various reasons have developed heart failure. Unfortunately, some are repetitively tox screen positive with varying trifectas of methamphetamine (meth), cocaine, and THC; opiates, meth, and THC; alcohol, meth, and THC; or heroin, meth, and THC. THC, the ever present and essential third leg of the stool of stupor. These unfortunate patients often need heart failure medications that they can’t afford or won’t take because illicit drug use is expensive and dulls their ability to prioritize their health. Some desperately need a heart transplant, but the necessary negative drug screen is a pipe dream.

And it’s not just the heart that is affected. There are data linking cannabis use to a higher risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. A retrospective study published in Stroke, of more than 1,000 people diagnosed with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, found that more than half of the 46 who tested positive for THC at admission developed delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI), which increases the risk for disability or early death. This was after adjusting for several patient characteristics as well as recent exposure to other illicit substances; cocaine, meth, and tobacco use were not associated with DCI.

Natural my ...

I’m certain my anti-cannabis stance will strike a nerve with those who love their recreational THC and push for its legal sale; after all, “It’s perfectly natural.” But I counter with the fact that tornadoes, earthquakes, cyanide, and appendicitis are all natural but certainly not optimal. And what we are seeing in the vascular specialties is completely unnatural. We are treating a different mix of complications than before pot was readily accessible across several states.

Our most effective action is to educate our patients. We should encourage those who don’t currently smoke cannabis to never start and those who do to quit. People who require marijuana for improved quality of life for terminal care or true (not supposed) disorders that mainstream medicine fails should be approached with empathy and caution.

A good rule of thumb is to never breathe anything you can see. Never put anything in your body that comes off the street: Drug dealers who sell cannabis cut with fentanyl will be ecstatic to take someone’s money then merely keep scrolling when their obituary comes up.

Let’s try to reverse the rise of vascular complications, orthopedic injuries, and vomiting across America. We can start by encouraging our patients to avoid “skunk weed” and get back to the sweet smells of nature in our cities and parks.

Some details have been changed to protect the patients’ identities, but the essence of their diagnoses has been preserved.

Dr. Walton-Shirley is a retired clinical cardiologist from Nashville, Tenn. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year, my husband and I took a 16-day road trip from Kentucky through Massachusetts to Maine. On our first morning in Boston, we exited the Park Street Station en route to Boston Common, but instead of being greeted by the aroma of molasses, we were hit full-on with a pungent, repulsive odor. “That’s skunk weed,” my husband chuckled as we stepped right into the middle of the Boston Freedom Rally, a celebration of all things cannabis.

As we boarded a hop-on-hop-off bus, we learned that this was the one week of the year that the city skips testing tour bus drivers for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), “because we all test positive,” the driver quipped. As our open-air bus circled the Common, a crowd of pot enthusiasts displayed signs in support of relaxed regulation for public consumption.

The 34-year-old Boston Freedom Rally is a sign that U.S. culture has transformed forever. Mary Jane is no friend of emergency physicians nor of staff on hospital wards and offices.

Toking boomers and millennials

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego, looked at cannabis-related emergency department visits from all acute-care hospitals in the state from 2005 to 2019 and found an 1,808% increase in patients aged 65 or older (that is not a typo) who were there for complications from cannabis use.

The lead author said in an interview that, “older patients taking marijuana or related products may have dizziness and falls, heart palpitations, panic attacks, confusion, anxiety or worsening of underlying lung diseases, such as asthma or [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].”

A recent study from Canada suggests that commercialization has been associated with an increase in related hospitalizations, including cannabis-induced psychosis.

According to a National Study of Drug Use and Health, marijuana use in young adults reached an all-time high (pun intended) in 2021. Nearly 10% of eighth graders and 20% of 10th graders reported using marijuana this past year.

The full downside of any drug, legal or illegal, is largely unknown until it infiltrates the mainstream market, but these are the typical cases we see:

Let’s start with the demotivated high school honors student who dropped out of college to work at the local cinema. He stumbled and broke his clavicle outside a bar at 2 AM, but he wasn’t sure if he passed out, so a cardiology consult was requested to “rule out” arrhythmia associated with syncope. He related that his plan to become a railway conductor had been upended because he knew he would be drug tested and just couldn’t give up pot. After a normal cardiac exam, ECG, labs, a Holter, and an echocardiogram were also requested and normal at a significant cost.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

One of my Midwest colleagues related her encounter with two middle-aged pot users with ventricular tachycardia (VT). These episodes coincided with potassium levels less than 3.0 mEq/L in the setting of repetitive vomiting. The QTc interval didn’t normalize despite a corrected potassium level in one patient. They were both informed that they should never smoke pot because vomiting would predictably drop their K+ levels again and prolong their QTc intervals. Then began “the circular argument,” as my friend described it. The patient claims, “I smoke pot to relieve my nausea,” to which she explains that “in many folks, pot use induces nausea.” Of course, the classic reply is, “Not me.” Predictably one of these stoners soon returned with more VT, more puking, and more hypokalemia. “Consider yourself ‘allergic’ to pot smoke,” my friend advised, but “was met with no meaningful hint of understanding or hope for transformative change,” she told me.

I’ve seen cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome several times in the past few years. It occurs in daily to weekly pot users. Very rarely, it can cause cerebral edema, but it is also associated with seizures and dehydration that can lead to hypovolemic shock and kidney failure.

Heart and brain harm

Then there are the young patients who for various reasons have developed heart failure. Unfortunately, some are repetitively tox screen positive with varying trifectas of methamphetamine (meth), cocaine, and THC; opiates, meth, and THC; alcohol, meth, and THC; or heroin, meth, and THC. THC, the ever present and essential third leg of the stool of stupor. These unfortunate patients often need heart failure medications that they can’t afford or won’t take because illicit drug use is expensive and dulls their ability to prioritize their health. Some desperately need a heart transplant, but the necessary negative drug screen is a pipe dream.