User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention no longer under consideration by the FDA

Tosha Rogers, MD, is a one-woman HIV prevention evangelist. For nearly a decade now, the Atlanta-based ob/gyn has been on a mission to increase her gynecological colleagues’ awareness and prescribing of the oral HIV prevention pill. At the same time, she’s been tracking the development of a flexible vaginal ring loaded with a month’s worth of the HIV prevention medication dapivirine. That, she thought, would fit easily into women’s lives and into the toolbox of methods women already use to prevent pregnancy.

But now she’s not sure when – or if – the ring will find its way to her patients. In December, the ring’s maker, the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM), pulled its application for FDA approval for the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) ring. Now, one year after the World Health Organization recommended the ring for member nations, there appears to be no path forward in the United States for either the dapivirine-only ring or an approach Dr. Rogers said would change the game: a vaginal ring that supplies both contraception and HIV prevention.

“It would take things to a whole other level,” she said. “It sucks that this happened, and I do think it was not anything medical. I think it was everything political.”

That leaves cisgender women – especially the Black and Latinx women who make up the vast majority of women who acquire HIV every year – with two HIV prevention options. One is the daily pill, first approved in 2012. It’s now generic but previously sold as Truvada by Gilead Sciences. The other is monthly injectable cabotegravir long-acting (Apretude). Another HIV prevention pill, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy), is approved for gay men and transgender women but not cisgender women.

Vagina-specific protection from HIV

The WHO recommendation for the vaginal ring was followed last July by a positive opinion from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for women in low- and middle-income countries outside the European Union.

The flexible silicone ring, similar to the hormonal NuvaRing contraceptive, works by slowly releasing the antiretroviral dapivirine directly into the vaginal canal, thereby protecting women who might be exposed to the virus through vaginal sex only. Because the medicine stays where it’s delivered and doesn’t circulate through the body, it has been found to be extremely safe with few adverse events.

However, in initial studies, the ring was found to be just 27% effective overall. Later studies, where scientists divided women by how much drug was missing from the ring – a proxy for use – found that higher use was associated with higher protection (as much as 54%). By comparison, Truvada has been found to be up to 99% effective when used daily, though it can take up to 21 days to be available in the vagina in high enough concentrations to protect women from vaginal exposure. And the HIV prevention shot was found to be 90% more effective than that in a recent trial of the two methods conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network.

This, and an orientation away from topical HIV prevention drugs and toward systemic options, led the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) to discontinue funding for such projects under its Microbicide Trials Network.

“Clearly you want to counsel women to use the highest efficacy method, and that is part of our label,” Zeda Rosenberg, ScD, IPM’s founder and chief executive officer, told this news organization. “Women should not choose the ring if they can and will use oral PrEP, and I would argue it should be the same thing for [cabotegravir shots]. But if they can’t or don’t want to – and we know that especially many young women don’t want to use systemic methods – then the dapivirine ring is a great option.”

Still, Dr. Rosenberg said that the gap in efficacy, the relatively small number of women affected by HIV in the U.S. compared with gay and bisexual men, and the emergence of products like the HIV prevention shot cabotegravir, made it “very unlikely” that FDA regulators would approve the ring. And rather than be “distracted” by the FDA process, Dr. Rosenberg said IPM chose to concentrate on the countries where the ring has already been approved or where women make up the vast majority of people affected by HIV.

Zimbabwe publicly announced it has approved the ring, and three other countries may have approved it, according to Dr. Rosenberg. She declined to name them, saying they had requested silence while they formulate their new HIV prevention guidelines. Aside from Zimbabwe, the other countries where women participated in the ring clinical trials were South Africa, Malawi, and Uganda.

“The U.S. population ... has widespread access to oral PrEP, which is unlike countries in Africa, and which would have widespread access to injectable cabotegravir,” she said. “The U.S. FDA may not see choice in the same way that African women and African activists and advocates see the need for choice.”

But women’s rates of accessing HIV prevention medications in the U.S. continues to be frustratingly low. At the end of 2018, just 7% of women who could benefit from HIV prevention drugs were taking them, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

New CDC guidelines recommend clinicians talk to every sexually active adult and adolescent about HIV prevention medications at least once and prescribe it to anyone who asks for it, whether or not they understand their patients’ HIV risks. However, research continues to show that clinicians struggle with willingness to prescribe PrEP to Black women, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology’s committee opinion on managing women using HIV prevention drugs has not been updated to reflect the new guidelines. And while the HIV prevention shot is approved for women and its maker ViiV Healthcare is already initiating postmarket studies of the ring in key populations including women, there are lots of things that need to line up in order for clinicians to be willing to stock it and prescribe it to women.

From where Dázon Dixon Diallo, executive director of the nonprofit SisterLove, sits, the decision to withdraw the ring from FDA consideration and the FDA’s seeming argument that the epidemiology in the U.S. doesn’t warrant the ring’s approval is a slap in the face to the Black women who have led the movement to end HIV in the U.S. for decades.

“No matter how you slice it, we’re talking about Black women, and then we’re talking about brown women,” said Ms. Diallo. “The value [they place on us] from a government standpoint, from a political standpoint, from a public health standpoint is just woeful. It’s woeful and it’s disrespectful and it’s insulting and I’m sick of it.”

‘America sneezes and Africa catches a cold’

When she first heard the decision to pull the ring from FDA consideration, Yvette Raphael, the South Africa-based executive director of Advocates for the Prevention of HIV in Africa, started asking, “What can we do to help our sisters in America get this ring?” And then she started worrying about other women in her own country and those nearby.

“The FDA plays a big role,” she said. “You know, America sneezes and Africa catches a cold.”

She worries that IPM’s decision to withdraw the ring from FDA consideration will signal to regulators in other countries either (a) that they should not approve it or (b) in countries where it’s already been approved but guidelines have not been issued, that they won’t invest money in rolling it out to women in those countries – especially now with the U.S. approval of the prevention shot. In much of Africa, ministries of health prefer to provide injectable contraception, often giving women few or no other options. But women, she said, think about more than administration of the drug. They look at if it’s an easier option for them to manage.

“This is a long journey, an emotional one too, for women in South Africa, because the idea of a microbicide is one of the ideas that came directly from women in South Africa,” she said. “[The jab] can be seen as a solution to all. We can just give jabs to all the women. And after all, we know that women don’t adhere, so we can just grab them.”

Dr. Rosenberg pointed to the positive opinion from the EMA as another “rigorous review” process that she said ought to equally influence ministries of health in countries where women tested the ring. And she pointed to the WHO statement released last month, the same day as IPM’s announcement that it was withdrawing the ring from FDA considerations, recommitting the ring as a good option in sub-Saharan Africa: “The U.S. FDA decision is not based on any new or additional data on efficacy and safety,” it stated. “WHO will continue to support countries as they consider whether to include the [dapivirine vaginal ring]. WHO recognizes that country decisionmaking will vary based on their context and that women’s voices remain central to discussions about their prevention choices.”

Dual action ring on the horizon, but not in U.S.

What this means, though, is that the next step in the ring’s development – the combination dapivirine ring with contraceptive levonorgestrel (used in the Mirena intrauterine device) – may not come to the U.S., at least for a long while.

“It’s not out of the question,” Dr. Rosenberg said of conducting HIV/pregnancy prevention ring trials in the U.S. “But without the approval of the dapivirine-only ring by FDA, I imagine they would want to see new efficacy data on dapivirine. That is a very difficult hill to climb. There would have to be an active control group [using oral PrEP or injectable cabotegravir], and it would be very difficult for the dapivirine ring to be able to go head-to-head for either noninferiority and certainly for superiority.”

The study would need to be quite large to get enough results to prove anything, and IPM is a research organization, not a large pharmaceutical company with deep enough pockets to fund that, she said. Raising those funds “would be difficult.”

In addition to NIAID discontinuing its funding for the Microbicides Trials Network, a new 5-year, $85 million research collaboration through USAID hasn’t slated any money to fund trials of the combination HIV prevention and contraceptive ring, according to Dr. Rosenberg.

But that doesn’t mean avenues for its development are closed. NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) is currently funding a phase 1/2 trial of the combination ring, and IPM continues to receive funding from research agencies in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Ireland. And this means, she said, that the E.U. – not the U.S. – is where they would seek approval for a combination ring first.

That leaves Ms. Rafael and Ms. Diallo debating how to work together to push the FDA – and maybe IPM – to reconsider the ring. For instance, Ms. Diallo suggested that instead of seeking an indication for all women, the FDA might consider the ring for women with very high risk of HIV, such as sex workers or women with HIV positive partners not on treatment. And she said that this has to be bigger than HIV prevention. It has to be about the ways in which women’s health issues in general lag at the FDA. For instance, she pointed to the movement to get contraceptive pills available over the counter, fights against FDA rulings on hormone replacement therapy, and fights for emergency contraception.

In the meantime, ob/gyn Dr. Rogers is expecting access to the ring to follow a similar path as the copper IUD, which migrated to the U.S. from Europe, where it has been among the most popular contraceptive methods for women.

“Contrary to what we may think, we are not innovators, especially for something like this,” she said. “Once we see it is working and doing a good job – that women in Europe love it – then someone here is going to pick it up and make it as if it’s the greatest thing. But for now, I think we’re going to have to take a back seat to Europe.”

Ms. Diallo reports receiving fees from Johnson & Johnson, ViiV Healthcare, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Rosenberg and Dr. Rogers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tosha Rogers, MD, is a one-woman HIV prevention evangelist. For nearly a decade now, the Atlanta-based ob/gyn has been on a mission to increase her gynecological colleagues’ awareness and prescribing of the oral HIV prevention pill. At the same time, she’s been tracking the development of a flexible vaginal ring loaded with a month’s worth of the HIV prevention medication dapivirine. That, she thought, would fit easily into women’s lives and into the toolbox of methods women already use to prevent pregnancy.

But now she’s not sure when – or if – the ring will find its way to her patients. In December, the ring’s maker, the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM), pulled its application for FDA approval for the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) ring. Now, one year after the World Health Organization recommended the ring for member nations, there appears to be no path forward in the United States for either the dapivirine-only ring or an approach Dr. Rogers said would change the game: a vaginal ring that supplies both contraception and HIV prevention.

“It would take things to a whole other level,” she said. “It sucks that this happened, and I do think it was not anything medical. I think it was everything political.”

That leaves cisgender women – especially the Black and Latinx women who make up the vast majority of women who acquire HIV every year – with two HIV prevention options. One is the daily pill, first approved in 2012. It’s now generic but previously sold as Truvada by Gilead Sciences. The other is monthly injectable cabotegravir long-acting (Apretude). Another HIV prevention pill, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy), is approved for gay men and transgender women but not cisgender women.

Vagina-specific protection from HIV

The WHO recommendation for the vaginal ring was followed last July by a positive opinion from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for women in low- and middle-income countries outside the European Union.

The flexible silicone ring, similar to the hormonal NuvaRing contraceptive, works by slowly releasing the antiretroviral dapivirine directly into the vaginal canal, thereby protecting women who might be exposed to the virus through vaginal sex only. Because the medicine stays where it’s delivered and doesn’t circulate through the body, it has been found to be extremely safe with few adverse events.

However, in initial studies, the ring was found to be just 27% effective overall. Later studies, where scientists divided women by how much drug was missing from the ring – a proxy for use – found that higher use was associated with higher protection (as much as 54%). By comparison, Truvada has been found to be up to 99% effective when used daily, though it can take up to 21 days to be available in the vagina in high enough concentrations to protect women from vaginal exposure. And the HIV prevention shot was found to be 90% more effective than that in a recent trial of the two methods conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network.

This, and an orientation away from topical HIV prevention drugs and toward systemic options, led the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) to discontinue funding for such projects under its Microbicide Trials Network.

“Clearly you want to counsel women to use the highest efficacy method, and that is part of our label,” Zeda Rosenberg, ScD, IPM’s founder and chief executive officer, told this news organization. “Women should not choose the ring if they can and will use oral PrEP, and I would argue it should be the same thing for [cabotegravir shots]. But if they can’t or don’t want to – and we know that especially many young women don’t want to use systemic methods – then the dapivirine ring is a great option.”

Still, Dr. Rosenberg said that the gap in efficacy, the relatively small number of women affected by HIV in the U.S. compared with gay and bisexual men, and the emergence of products like the HIV prevention shot cabotegravir, made it “very unlikely” that FDA regulators would approve the ring. And rather than be “distracted” by the FDA process, Dr. Rosenberg said IPM chose to concentrate on the countries where the ring has already been approved or where women make up the vast majority of people affected by HIV.

Zimbabwe publicly announced it has approved the ring, and three other countries may have approved it, according to Dr. Rosenberg. She declined to name them, saying they had requested silence while they formulate their new HIV prevention guidelines. Aside from Zimbabwe, the other countries where women participated in the ring clinical trials were South Africa, Malawi, and Uganda.

“The U.S. population ... has widespread access to oral PrEP, which is unlike countries in Africa, and which would have widespread access to injectable cabotegravir,” she said. “The U.S. FDA may not see choice in the same way that African women and African activists and advocates see the need for choice.”

But women’s rates of accessing HIV prevention medications in the U.S. continues to be frustratingly low. At the end of 2018, just 7% of women who could benefit from HIV prevention drugs were taking them, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

New CDC guidelines recommend clinicians talk to every sexually active adult and adolescent about HIV prevention medications at least once and prescribe it to anyone who asks for it, whether or not they understand their patients’ HIV risks. However, research continues to show that clinicians struggle with willingness to prescribe PrEP to Black women, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology’s committee opinion on managing women using HIV prevention drugs has not been updated to reflect the new guidelines. And while the HIV prevention shot is approved for women and its maker ViiV Healthcare is already initiating postmarket studies of the ring in key populations including women, there are lots of things that need to line up in order for clinicians to be willing to stock it and prescribe it to women.

From where Dázon Dixon Diallo, executive director of the nonprofit SisterLove, sits, the decision to withdraw the ring from FDA consideration and the FDA’s seeming argument that the epidemiology in the U.S. doesn’t warrant the ring’s approval is a slap in the face to the Black women who have led the movement to end HIV in the U.S. for decades.

“No matter how you slice it, we’re talking about Black women, and then we’re talking about brown women,” said Ms. Diallo. “The value [they place on us] from a government standpoint, from a political standpoint, from a public health standpoint is just woeful. It’s woeful and it’s disrespectful and it’s insulting and I’m sick of it.”

‘America sneezes and Africa catches a cold’

When she first heard the decision to pull the ring from FDA consideration, Yvette Raphael, the South Africa-based executive director of Advocates for the Prevention of HIV in Africa, started asking, “What can we do to help our sisters in America get this ring?” And then she started worrying about other women in her own country and those nearby.

“The FDA plays a big role,” she said. “You know, America sneezes and Africa catches a cold.”

She worries that IPM’s decision to withdraw the ring from FDA consideration will signal to regulators in other countries either (a) that they should not approve it or (b) in countries where it’s already been approved but guidelines have not been issued, that they won’t invest money in rolling it out to women in those countries – especially now with the U.S. approval of the prevention shot. In much of Africa, ministries of health prefer to provide injectable contraception, often giving women few or no other options. But women, she said, think about more than administration of the drug. They look at if it’s an easier option for them to manage.

“This is a long journey, an emotional one too, for women in South Africa, because the idea of a microbicide is one of the ideas that came directly from women in South Africa,” she said. “[The jab] can be seen as a solution to all. We can just give jabs to all the women. And after all, we know that women don’t adhere, so we can just grab them.”

Dr. Rosenberg pointed to the positive opinion from the EMA as another “rigorous review” process that she said ought to equally influence ministries of health in countries where women tested the ring. And she pointed to the WHO statement released last month, the same day as IPM’s announcement that it was withdrawing the ring from FDA considerations, recommitting the ring as a good option in sub-Saharan Africa: “The U.S. FDA decision is not based on any new or additional data on efficacy and safety,” it stated. “WHO will continue to support countries as they consider whether to include the [dapivirine vaginal ring]. WHO recognizes that country decisionmaking will vary based on their context and that women’s voices remain central to discussions about their prevention choices.”

Dual action ring on the horizon, but not in U.S.

What this means, though, is that the next step in the ring’s development – the combination dapivirine ring with contraceptive levonorgestrel (used in the Mirena intrauterine device) – may not come to the U.S., at least for a long while.

“It’s not out of the question,” Dr. Rosenberg said of conducting HIV/pregnancy prevention ring trials in the U.S. “But without the approval of the dapivirine-only ring by FDA, I imagine they would want to see new efficacy data on dapivirine. That is a very difficult hill to climb. There would have to be an active control group [using oral PrEP or injectable cabotegravir], and it would be very difficult for the dapivirine ring to be able to go head-to-head for either noninferiority and certainly for superiority.”

The study would need to be quite large to get enough results to prove anything, and IPM is a research organization, not a large pharmaceutical company with deep enough pockets to fund that, she said. Raising those funds “would be difficult.”

In addition to NIAID discontinuing its funding for the Microbicides Trials Network, a new 5-year, $85 million research collaboration through USAID hasn’t slated any money to fund trials of the combination HIV prevention and contraceptive ring, according to Dr. Rosenberg.

But that doesn’t mean avenues for its development are closed. NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) is currently funding a phase 1/2 trial of the combination ring, and IPM continues to receive funding from research agencies in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Ireland. And this means, she said, that the E.U. – not the U.S. – is where they would seek approval for a combination ring first.

That leaves Ms. Rafael and Ms. Diallo debating how to work together to push the FDA – and maybe IPM – to reconsider the ring. For instance, Ms. Diallo suggested that instead of seeking an indication for all women, the FDA might consider the ring for women with very high risk of HIV, such as sex workers or women with HIV positive partners not on treatment. And she said that this has to be bigger than HIV prevention. It has to be about the ways in which women’s health issues in general lag at the FDA. For instance, she pointed to the movement to get contraceptive pills available over the counter, fights against FDA rulings on hormone replacement therapy, and fights for emergency contraception.

In the meantime, ob/gyn Dr. Rogers is expecting access to the ring to follow a similar path as the copper IUD, which migrated to the U.S. from Europe, where it has been among the most popular contraceptive methods for women.

“Contrary to what we may think, we are not innovators, especially for something like this,” she said. “Once we see it is working and doing a good job – that women in Europe love it – then someone here is going to pick it up and make it as if it’s the greatest thing. But for now, I think we’re going to have to take a back seat to Europe.”

Ms. Diallo reports receiving fees from Johnson & Johnson, ViiV Healthcare, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Rosenberg and Dr. Rogers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tosha Rogers, MD, is a one-woman HIV prevention evangelist. For nearly a decade now, the Atlanta-based ob/gyn has been on a mission to increase her gynecological colleagues’ awareness and prescribing of the oral HIV prevention pill. At the same time, she’s been tracking the development of a flexible vaginal ring loaded with a month’s worth of the HIV prevention medication dapivirine. That, she thought, would fit easily into women’s lives and into the toolbox of methods women already use to prevent pregnancy.

But now she’s not sure when – or if – the ring will find its way to her patients. In December, the ring’s maker, the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM), pulled its application for FDA approval for the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) ring. Now, one year after the World Health Organization recommended the ring for member nations, there appears to be no path forward in the United States for either the dapivirine-only ring or an approach Dr. Rogers said would change the game: a vaginal ring that supplies both contraception and HIV prevention.

“It would take things to a whole other level,” she said. “It sucks that this happened, and I do think it was not anything medical. I think it was everything political.”

That leaves cisgender women – especially the Black and Latinx women who make up the vast majority of women who acquire HIV every year – with two HIV prevention options. One is the daily pill, first approved in 2012. It’s now generic but previously sold as Truvada by Gilead Sciences. The other is monthly injectable cabotegravir long-acting (Apretude). Another HIV prevention pill, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy), is approved for gay men and transgender women but not cisgender women.

Vagina-specific protection from HIV

The WHO recommendation for the vaginal ring was followed last July by a positive opinion from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for women in low- and middle-income countries outside the European Union.

The flexible silicone ring, similar to the hormonal NuvaRing contraceptive, works by slowly releasing the antiretroviral dapivirine directly into the vaginal canal, thereby protecting women who might be exposed to the virus through vaginal sex only. Because the medicine stays where it’s delivered and doesn’t circulate through the body, it has been found to be extremely safe with few adverse events.

However, in initial studies, the ring was found to be just 27% effective overall. Later studies, where scientists divided women by how much drug was missing from the ring – a proxy for use – found that higher use was associated with higher protection (as much as 54%). By comparison, Truvada has been found to be up to 99% effective when used daily, though it can take up to 21 days to be available in the vagina in high enough concentrations to protect women from vaginal exposure. And the HIV prevention shot was found to be 90% more effective than that in a recent trial of the two methods conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network.

This, and an orientation away from topical HIV prevention drugs and toward systemic options, led the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) to discontinue funding for such projects under its Microbicide Trials Network.

“Clearly you want to counsel women to use the highest efficacy method, and that is part of our label,” Zeda Rosenberg, ScD, IPM’s founder and chief executive officer, told this news organization. “Women should not choose the ring if they can and will use oral PrEP, and I would argue it should be the same thing for [cabotegravir shots]. But if they can’t or don’t want to – and we know that especially many young women don’t want to use systemic methods – then the dapivirine ring is a great option.”

Still, Dr. Rosenberg said that the gap in efficacy, the relatively small number of women affected by HIV in the U.S. compared with gay and bisexual men, and the emergence of products like the HIV prevention shot cabotegravir, made it “very unlikely” that FDA regulators would approve the ring. And rather than be “distracted” by the FDA process, Dr. Rosenberg said IPM chose to concentrate on the countries where the ring has already been approved or where women make up the vast majority of people affected by HIV.

Zimbabwe publicly announced it has approved the ring, and three other countries may have approved it, according to Dr. Rosenberg. She declined to name them, saying they had requested silence while they formulate their new HIV prevention guidelines. Aside from Zimbabwe, the other countries where women participated in the ring clinical trials were South Africa, Malawi, and Uganda.

“The U.S. population ... has widespread access to oral PrEP, which is unlike countries in Africa, and which would have widespread access to injectable cabotegravir,” she said. “The U.S. FDA may not see choice in the same way that African women and African activists and advocates see the need for choice.”

But women’s rates of accessing HIV prevention medications in the U.S. continues to be frustratingly low. At the end of 2018, just 7% of women who could benefit from HIV prevention drugs were taking them, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

New CDC guidelines recommend clinicians talk to every sexually active adult and adolescent about HIV prevention medications at least once and prescribe it to anyone who asks for it, whether or not they understand their patients’ HIV risks. However, research continues to show that clinicians struggle with willingness to prescribe PrEP to Black women, and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology’s committee opinion on managing women using HIV prevention drugs has not been updated to reflect the new guidelines. And while the HIV prevention shot is approved for women and its maker ViiV Healthcare is already initiating postmarket studies of the ring in key populations including women, there are lots of things that need to line up in order for clinicians to be willing to stock it and prescribe it to women.

From where Dázon Dixon Diallo, executive director of the nonprofit SisterLove, sits, the decision to withdraw the ring from FDA consideration and the FDA’s seeming argument that the epidemiology in the U.S. doesn’t warrant the ring’s approval is a slap in the face to the Black women who have led the movement to end HIV in the U.S. for decades.

“No matter how you slice it, we’re talking about Black women, and then we’re talking about brown women,” said Ms. Diallo. “The value [they place on us] from a government standpoint, from a political standpoint, from a public health standpoint is just woeful. It’s woeful and it’s disrespectful and it’s insulting and I’m sick of it.”

‘America sneezes and Africa catches a cold’

When she first heard the decision to pull the ring from FDA consideration, Yvette Raphael, the South Africa-based executive director of Advocates for the Prevention of HIV in Africa, started asking, “What can we do to help our sisters in America get this ring?” And then she started worrying about other women in her own country and those nearby.

“The FDA plays a big role,” she said. “You know, America sneezes and Africa catches a cold.”

She worries that IPM’s decision to withdraw the ring from FDA consideration will signal to regulators in other countries either (a) that they should not approve it or (b) in countries where it’s already been approved but guidelines have not been issued, that they won’t invest money in rolling it out to women in those countries – especially now with the U.S. approval of the prevention shot. In much of Africa, ministries of health prefer to provide injectable contraception, often giving women few or no other options. But women, she said, think about more than administration of the drug. They look at if it’s an easier option for them to manage.

“This is a long journey, an emotional one too, for women in South Africa, because the idea of a microbicide is one of the ideas that came directly from women in South Africa,” she said. “[The jab] can be seen as a solution to all. We can just give jabs to all the women. And after all, we know that women don’t adhere, so we can just grab them.”

Dr. Rosenberg pointed to the positive opinion from the EMA as another “rigorous review” process that she said ought to equally influence ministries of health in countries where women tested the ring. And she pointed to the WHO statement released last month, the same day as IPM’s announcement that it was withdrawing the ring from FDA considerations, recommitting the ring as a good option in sub-Saharan Africa: “The U.S. FDA decision is not based on any new or additional data on efficacy and safety,” it stated. “WHO will continue to support countries as they consider whether to include the [dapivirine vaginal ring]. WHO recognizes that country decisionmaking will vary based on their context and that women’s voices remain central to discussions about their prevention choices.”

Dual action ring on the horizon, but not in U.S.

What this means, though, is that the next step in the ring’s development – the combination dapivirine ring with contraceptive levonorgestrel (used in the Mirena intrauterine device) – may not come to the U.S., at least for a long while.

“It’s not out of the question,” Dr. Rosenberg said of conducting HIV/pregnancy prevention ring trials in the U.S. “But without the approval of the dapivirine-only ring by FDA, I imagine they would want to see new efficacy data on dapivirine. That is a very difficult hill to climb. There would have to be an active control group [using oral PrEP or injectable cabotegravir], and it would be very difficult for the dapivirine ring to be able to go head-to-head for either noninferiority and certainly for superiority.”

The study would need to be quite large to get enough results to prove anything, and IPM is a research organization, not a large pharmaceutical company with deep enough pockets to fund that, she said. Raising those funds “would be difficult.”

In addition to NIAID discontinuing its funding for the Microbicides Trials Network, a new 5-year, $85 million research collaboration through USAID hasn’t slated any money to fund trials of the combination HIV prevention and contraceptive ring, according to Dr. Rosenberg.

But that doesn’t mean avenues for its development are closed. NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) is currently funding a phase 1/2 trial of the combination ring, and IPM continues to receive funding from research agencies in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Ireland. And this means, she said, that the E.U. – not the U.S. – is where they would seek approval for a combination ring first.

That leaves Ms. Rafael and Ms. Diallo debating how to work together to push the FDA – and maybe IPM – to reconsider the ring. For instance, Ms. Diallo suggested that instead of seeking an indication for all women, the FDA might consider the ring for women with very high risk of HIV, such as sex workers or women with HIV positive partners not on treatment. And she said that this has to be bigger than HIV prevention. It has to be about the ways in which women’s health issues in general lag at the FDA. For instance, she pointed to the movement to get contraceptive pills available over the counter, fights against FDA rulings on hormone replacement therapy, and fights for emergency contraception.

In the meantime, ob/gyn Dr. Rogers is expecting access to the ring to follow a similar path as the copper IUD, which migrated to the U.S. from Europe, where it has been among the most popular contraceptive methods for women.

“Contrary to what we may think, we are not innovators, especially for something like this,” she said. “Once we see it is working and doing a good job – that women in Europe love it – then someone here is going to pick it up and make it as if it’s the greatest thing. But for now, I think we’re going to have to take a back seat to Europe.”

Ms. Diallo reports receiving fees from Johnson & Johnson, ViiV Healthcare, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Rosenberg and Dr. Rogers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Watch, but don’t worry yet, about new Omicron subvariant

In the meantime, it’s worth watching BA.2, the World Health Organization said. The subvariant has been identified across at least 40 countries, including three cases reported in Houston and several in Washington state.

BA.2 accounts for only a small minority of reported cases so far, including 5% in India, 4% of those in the United Kingdom, and 2% each of cases in Sweden and Singapore.

The one exception is Denmark, a country with robust genetic sequencing abilities, where estimates range from 50% to 81% of cases.

The news throws a little more uncertainty into an already uncertain situation, including how close the world might be to a less life-altering infectious disease.

For example, the world is at an ideal point for a new variant to emerge, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, said during a Jan. 24 meeting of the WHO executive board. He also said it’s too early to call an “end game” to the pandemic.

Similarly, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said on Jan. 19 that it remained “an open question” whether the Omicron variant could hasten endemic COVID-19, a situation where the virus still circulates but is much less disruptive to everyday life.

No Pi for you

This could be the first time a coronavirus subvariant rises to the level of a household name, or – if previous variants of the moment have shown us – it could recede from the spotlight.

For example, a lot of focus on the potential of the Mu variant to wreak havoc fizzled out a few weeks after the WHO listed it as a variant of interest on Aug. 30.

Subvariants can feature mutations and other small differences but are not distinct enough from an existing strain to be called a variant on their own and be named after the next letter in the Greek alphabet. That’s why BA.2 is not called the “Pi variant.”

Predicting what’s next for the coronavirus has puzzled many experts throughout the pandemic. That is why many public health officials wait for the WHO to officially designate a strain as a variant of interest or variant of concern before taking action.

At the moment with BA.2, it seems close monitoring is warranted.

Because it’s too early to call, expert predictions about BA.2 vary widely, from worry to cautious optimism.

For example, early data indicates that BA.2 could be more worrisome than original Omicron, Eric Feigl-Ding, ScD, an epidemiologist and health economist, said on Twitter.

Information from Denmark seems to show BA.2 either has “much faster transmission or it evades immunity even more,” he said.

The same day, Jan. 23, Dr. Feigl-Ding tweeted that other data shows the subvariant can spread twice as fast as Omicron, which was already much more contagious than previous versions of the virus.

At the same time, other experts appear less concerned. Robert Garry, PhD, a virologist at Tulane University, New Orleans, told the Washington Post that there is no reason to think BA.2 will be any worse than the original Omicron strain.

So which expert predictions will come closer to BA.2’s potential? For now, it’s just a watch-and-see situation.

For updated information, the website outbreak.info tracks BA.2’s average daily and cumulative prevalence in the United States and in other locations.

Also, if and when WHO experts decide to elevate BA.2 to a variant of interest or a variant of concern, it will be noted on its coronavirus variant tracking website.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In the meantime, it’s worth watching BA.2, the World Health Organization said. The subvariant has been identified across at least 40 countries, including three cases reported in Houston and several in Washington state.

BA.2 accounts for only a small minority of reported cases so far, including 5% in India, 4% of those in the United Kingdom, and 2% each of cases in Sweden and Singapore.

The one exception is Denmark, a country with robust genetic sequencing abilities, where estimates range from 50% to 81% of cases.

The news throws a little more uncertainty into an already uncertain situation, including how close the world might be to a less life-altering infectious disease.

For example, the world is at an ideal point for a new variant to emerge, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, said during a Jan. 24 meeting of the WHO executive board. He also said it’s too early to call an “end game” to the pandemic.

Similarly, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said on Jan. 19 that it remained “an open question” whether the Omicron variant could hasten endemic COVID-19, a situation where the virus still circulates but is much less disruptive to everyday life.

No Pi for you

This could be the first time a coronavirus subvariant rises to the level of a household name, or – if previous variants of the moment have shown us – it could recede from the spotlight.

For example, a lot of focus on the potential of the Mu variant to wreak havoc fizzled out a few weeks after the WHO listed it as a variant of interest on Aug. 30.

Subvariants can feature mutations and other small differences but are not distinct enough from an existing strain to be called a variant on their own and be named after the next letter in the Greek alphabet. That’s why BA.2 is not called the “Pi variant.”

Predicting what’s next for the coronavirus has puzzled many experts throughout the pandemic. That is why many public health officials wait for the WHO to officially designate a strain as a variant of interest or variant of concern before taking action.

At the moment with BA.2, it seems close monitoring is warranted.

Because it’s too early to call, expert predictions about BA.2 vary widely, from worry to cautious optimism.

For example, early data indicates that BA.2 could be more worrisome than original Omicron, Eric Feigl-Ding, ScD, an epidemiologist and health economist, said on Twitter.

Information from Denmark seems to show BA.2 either has “much faster transmission or it evades immunity even more,” he said.

The same day, Jan. 23, Dr. Feigl-Ding tweeted that other data shows the subvariant can spread twice as fast as Omicron, which was already much more contagious than previous versions of the virus.

At the same time, other experts appear less concerned. Robert Garry, PhD, a virologist at Tulane University, New Orleans, told the Washington Post that there is no reason to think BA.2 will be any worse than the original Omicron strain.

So which expert predictions will come closer to BA.2’s potential? For now, it’s just a watch-and-see situation.

For updated information, the website outbreak.info tracks BA.2’s average daily and cumulative prevalence in the United States and in other locations.

Also, if and when WHO experts decide to elevate BA.2 to a variant of interest or a variant of concern, it will be noted on its coronavirus variant tracking website.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In the meantime, it’s worth watching BA.2, the World Health Organization said. The subvariant has been identified across at least 40 countries, including three cases reported in Houston and several in Washington state.

BA.2 accounts for only a small minority of reported cases so far, including 5% in India, 4% of those in the United Kingdom, and 2% each of cases in Sweden and Singapore.

The one exception is Denmark, a country with robust genetic sequencing abilities, where estimates range from 50% to 81% of cases.

The news throws a little more uncertainty into an already uncertain situation, including how close the world might be to a less life-altering infectious disease.

For example, the world is at an ideal point for a new variant to emerge, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, said during a Jan. 24 meeting of the WHO executive board. He also said it’s too early to call an “end game” to the pandemic.

Similarly, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said on Jan. 19 that it remained “an open question” whether the Omicron variant could hasten endemic COVID-19, a situation where the virus still circulates but is much less disruptive to everyday life.

No Pi for you

This could be the first time a coronavirus subvariant rises to the level of a household name, or – if previous variants of the moment have shown us – it could recede from the spotlight.

For example, a lot of focus on the potential of the Mu variant to wreak havoc fizzled out a few weeks after the WHO listed it as a variant of interest on Aug. 30.

Subvariants can feature mutations and other small differences but are not distinct enough from an existing strain to be called a variant on their own and be named after the next letter in the Greek alphabet. That’s why BA.2 is not called the “Pi variant.”

Predicting what’s next for the coronavirus has puzzled many experts throughout the pandemic. That is why many public health officials wait for the WHO to officially designate a strain as a variant of interest or variant of concern before taking action.

At the moment with BA.2, it seems close monitoring is warranted.

Because it’s too early to call, expert predictions about BA.2 vary widely, from worry to cautious optimism.

For example, early data indicates that BA.2 could be more worrisome than original Omicron, Eric Feigl-Ding, ScD, an epidemiologist and health economist, said on Twitter.

Information from Denmark seems to show BA.2 either has “much faster transmission or it evades immunity even more,” he said.

The same day, Jan. 23, Dr. Feigl-Ding tweeted that other data shows the subvariant can spread twice as fast as Omicron, which was already much more contagious than previous versions of the virus.

At the same time, other experts appear less concerned. Robert Garry, PhD, a virologist at Tulane University, New Orleans, told the Washington Post that there is no reason to think BA.2 will be any worse than the original Omicron strain.

So which expert predictions will come closer to BA.2’s potential? For now, it’s just a watch-and-see situation.

For updated information, the website outbreak.info tracks BA.2’s average daily and cumulative prevalence in the United States and in other locations.

Also, if and when WHO experts decide to elevate BA.2 to a variant of interest or a variant of concern, it will be noted on its coronavirus variant tracking website.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Digital algorithm better predicts risk for postpartum hemorrhage

A digital algorithm using 24 patient characteristics identifies far more women who are likely to develop a postpartum hemorrhage than currently used tools to predict the risk for bleeding after delivery, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

About 1 in 10 of the roughly 700 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These deaths disproportionately occur among Black women, for whom studies show the risk of dying from a postpartum hemorrhage is fivefold greater than that of White women.

“Postpartum hemorrhage is a preventable medical emergency but remains the leading cause of maternal mortality globally,” the study’s senior author Li Li, MD, senior vice president of clinical informatics at Sema4, a company that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop data-based clinical tools, told this news organization. “Early intervention is critical for reducing postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality.”

Porous predictors

Existing tools for risk prediction are not particularly effective, Dr. Li said. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative offers checklists of clinical characteristics to classify women as low, medium, or high risk. However, 40% of the women classified as low risk based on this type of tool experience a hemorrhage.

ACOG also recommends quantifying blood loss during delivery or immediately after to identify women who are hemorrhaging, because imprecise estimates from clinicians may delay urgently needed care. Yet many hospitals have not implemented methods for measuring bleeding, said Dr. Li, who also is an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

To develop a more precise way of identifying women at risk, Dr. Li and colleagues turned to artificial intelligence technology to create a “digital phenotype” based on approximately 72,000 births in the Mount Sinai Health System.

The digital tool retrospectively identified about 6,600 cases of postpartum hemorrhage, about 3.8 times the roughly 1,700 cases that would have been predicted based on methods that estimate blood loss. A blinded physician review of a subset of 45 patient charts – including 26 patients who experienced a hemorrhage, 11 who didn’t, and 6 with unclear outcomes – found that the digital approach was 89% percent accurate at identifying cases, whereas blood loss–based methods were accurate 67% of the time.

Several of the 24 characteristics included in the model appear in other risk predictors, including whether a woman has had a previous cesarean delivery or prior postdelivery bleeding and whether she has anemia or related blood disorders. Among the rest were risk factors that have been identified in the literature, including maternal blood pressure, time from admission to delivery, and average pulse during hospitalization. Five more features were new: red blood cell count and distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count, and white blood cell count.

“These [new] values are easily obtainable from standard blood draws in the hospital but are not currently used in clinical practice to estimate postpartum hemorrhage risk,” Dr. Li said.

In a related retrospective study, Dr. Li and her colleagues used the new tool to classify women into high, low, or medium risk categories. They found that 28% of the women the algorithm classified as high risk experienced a postpartum hemorrhage compared with 15% to 19% of the women classified as high risk by standard predictive tools. They also identified potential “inflection points” where changes in vital signs may suggest a substantial increase in risk. For example, women whose median blood pressure during labor and delivery was above 132 mm Hg had an 11% average increase in their risk for bleeding.

By more precisely identifying women at risk, the new method “could be used to pre-emptively allocate resources that can ultimately reduce postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Li said. Sema4 is launching a prospective clinical trial to further assess the algorithm, she added.

Finding the continuum of risk

Holly Ende, MD, an obstetric anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said approaches that leverage electronic health records to identify women at risk for hemorrhage have many advantages over currently used tools.

“Machine learning models or statistical models are able to take into account many more risk factors and weigh each of those risk factors based on how much they contribute to risk,” Dr. Ende, who was not involved in the new studies, told this news organization. “We can stratify women more on a continuum.”

But digital approaches have potential downsides.

“Machine learning algorithms can be developed in such a way that perpetuates racial bias, and it’s important to be aware of potential biases in coded algorithms,” Dr. Li said. To help reduce such bias, they used a database that included a racially and ethnically diverse patient population, but she acknowledged that additional research is needed.

Dr. Ende, the coauthor of a commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology on risk assessment for postpartum hemorrhage, said algorithm developers must be sensitive to pre-existing disparities in health care that may affect the data they use to build the software.

She pointed to uterine atony – a known risk factor for hemorrhage – as an example. In her own research, she and her colleagues identified women with atony by searching their medical records for medications used to treat the condition. But when they ran their model, Black women were less likely to develop uterine atony, which the team knew wasn’t true in the real world. They traced the problem to an existing disparity in obstetric care: Black women with uterine atony were less likely than women of other races to receive medications for the condition.

“People need to be cognizant as they are developing these types of prediction models and be extremely careful to avoid perpetuating any disparities in care,” Dr. Ende cautioned. On the other hand, if carefully developed, these tools might also help reduce disparities in health care by standardizing risk stratification and clinical practices, she said.

In addition to independent validation of data-based risk prediction tools, Dr. Ende said ensuring that clinicians are properly trained to use these tools is crucial.

“Implementation may be the biggest limitation,” she said.

Dr. Ende and Dr. Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A digital algorithm using 24 patient characteristics identifies far more women who are likely to develop a postpartum hemorrhage than currently used tools to predict the risk for bleeding after delivery, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

About 1 in 10 of the roughly 700 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These deaths disproportionately occur among Black women, for whom studies show the risk of dying from a postpartum hemorrhage is fivefold greater than that of White women.

“Postpartum hemorrhage is a preventable medical emergency but remains the leading cause of maternal mortality globally,” the study’s senior author Li Li, MD, senior vice president of clinical informatics at Sema4, a company that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop data-based clinical tools, told this news organization. “Early intervention is critical for reducing postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality.”

Porous predictors

Existing tools for risk prediction are not particularly effective, Dr. Li said. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative offers checklists of clinical characteristics to classify women as low, medium, or high risk. However, 40% of the women classified as low risk based on this type of tool experience a hemorrhage.

ACOG also recommends quantifying blood loss during delivery or immediately after to identify women who are hemorrhaging, because imprecise estimates from clinicians may delay urgently needed care. Yet many hospitals have not implemented methods for measuring bleeding, said Dr. Li, who also is an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

To develop a more precise way of identifying women at risk, Dr. Li and colleagues turned to artificial intelligence technology to create a “digital phenotype” based on approximately 72,000 births in the Mount Sinai Health System.

The digital tool retrospectively identified about 6,600 cases of postpartum hemorrhage, about 3.8 times the roughly 1,700 cases that would have been predicted based on methods that estimate blood loss. A blinded physician review of a subset of 45 patient charts – including 26 patients who experienced a hemorrhage, 11 who didn’t, and 6 with unclear outcomes – found that the digital approach was 89% percent accurate at identifying cases, whereas blood loss–based methods were accurate 67% of the time.

Several of the 24 characteristics included in the model appear in other risk predictors, including whether a woman has had a previous cesarean delivery or prior postdelivery bleeding and whether she has anemia or related blood disorders. Among the rest were risk factors that have been identified in the literature, including maternal blood pressure, time from admission to delivery, and average pulse during hospitalization. Five more features were new: red blood cell count and distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count, and white blood cell count.

“These [new] values are easily obtainable from standard blood draws in the hospital but are not currently used in clinical practice to estimate postpartum hemorrhage risk,” Dr. Li said.

In a related retrospective study, Dr. Li and her colleagues used the new tool to classify women into high, low, or medium risk categories. They found that 28% of the women the algorithm classified as high risk experienced a postpartum hemorrhage compared with 15% to 19% of the women classified as high risk by standard predictive tools. They also identified potential “inflection points” where changes in vital signs may suggest a substantial increase in risk. For example, women whose median blood pressure during labor and delivery was above 132 mm Hg had an 11% average increase in their risk for bleeding.

By more precisely identifying women at risk, the new method “could be used to pre-emptively allocate resources that can ultimately reduce postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Li said. Sema4 is launching a prospective clinical trial to further assess the algorithm, she added.

Finding the continuum of risk

Holly Ende, MD, an obstetric anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said approaches that leverage electronic health records to identify women at risk for hemorrhage have many advantages over currently used tools.

“Machine learning models or statistical models are able to take into account many more risk factors and weigh each of those risk factors based on how much they contribute to risk,” Dr. Ende, who was not involved in the new studies, told this news organization. “We can stratify women more on a continuum.”

But digital approaches have potential downsides.

“Machine learning algorithms can be developed in such a way that perpetuates racial bias, and it’s important to be aware of potential biases in coded algorithms,” Dr. Li said. To help reduce such bias, they used a database that included a racially and ethnically diverse patient population, but she acknowledged that additional research is needed.

Dr. Ende, the coauthor of a commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology on risk assessment for postpartum hemorrhage, said algorithm developers must be sensitive to pre-existing disparities in health care that may affect the data they use to build the software.

She pointed to uterine atony – a known risk factor for hemorrhage – as an example. In her own research, she and her colleagues identified women with atony by searching their medical records for medications used to treat the condition. But when they ran their model, Black women were less likely to develop uterine atony, which the team knew wasn’t true in the real world. They traced the problem to an existing disparity in obstetric care: Black women with uterine atony were less likely than women of other races to receive medications for the condition.

“People need to be cognizant as they are developing these types of prediction models and be extremely careful to avoid perpetuating any disparities in care,” Dr. Ende cautioned. On the other hand, if carefully developed, these tools might also help reduce disparities in health care by standardizing risk stratification and clinical practices, she said.

In addition to independent validation of data-based risk prediction tools, Dr. Ende said ensuring that clinicians are properly trained to use these tools is crucial.

“Implementation may be the biggest limitation,” she said.

Dr. Ende and Dr. Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A digital algorithm using 24 patient characteristics identifies far more women who are likely to develop a postpartum hemorrhage than currently used tools to predict the risk for bleeding after delivery, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

About 1 in 10 of the roughly 700 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These deaths disproportionately occur among Black women, for whom studies show the risk of dying from a postpartum hemorrhage is fivefold greater than that of White women.

“Postpartum hemorrhage is a preventable medical emergency but remains the leading cause of maternal mortality globally,” the study’s senior author Li Li, MD, senior vice president of clinical informatics at Sema4, a company that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop data-based clinical tools, told this news organization. “Early intervention is critical for reducing postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality.”

Porous predictors

Existing tools for risk prediction are not particularly effective, Dr. Li said. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative offers checklists of clinical characteristics to classify women as low, medium, or high risk. However, 40% of the women classified as low risk based on this type of tool experience a hemorrhage.

ACOG also recommends quantifying blood loss during delivery or immediately after to identify women who are hemorrhaging, because imprecise estimates from clinicians may delay urgently needed care. Yet many hospitals have not implemented methods for measuring bleeding, said Dr. Li, who also is an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

To develop a more precise way of identifying women at risk, Dr. Li and colleagues turned to artificial intelligence technology to create a “digital phenotype” based on approximately 72,000 births in the Mount Sinai Health System.

The digital tool retrospectively identified about 6,600 cases of postpartum hemorrhage, about 3.8 times the roughly 1,700 cases that would have been predicted based on methods that estimate blood loss. A blinded physician review of a subset of 45 patient charts – including 26 patients who experienced a hemorrhage, 11 who didn’t, and 6 with unclear outcomes – found that the digital approach was 89% percent accurate at identifying cases, whereas blood loss–based methods were accurate 67% of the time.

Several of the 24 characteristics included in the model appear in other risk predictors, including whether a woman has had a previous cesarean delivery or prior postdelivery bleeding and whether she has anemia or related blood disorders. Among the rest were risk factors that have been identified in the literature, including maternal blood pressure, time from admission to delivery, and average pulse during hospitalization. Five more features were new: red blood cell count and distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count, and white blood cell count.

“These [new] values are easily obtainable from standard blood draws in the hospital but are not currently used in clinical practice to estimate postpartum hemorrhage risk,” Dr. Li said.

In a related retrospective study, Dr. Li and her colleagues used the new tool to classify women into high, low, or medium risk categories. They found that 28% of the women the algorithm classified as high risk experienced a postpartum hemorrhage compared with 15% to 19% of the women classified as high risk by standard predictive tools. They also identified potential “inflection points” where changes in vital signs may suggest a substantial increase in risk. For example, women whose median blood pressure during labor and delivery was above 132 mm Hg had an 11% average increase in their risk for bleeding.

By more precisely identifying women at risk, the new method “could be used to pre-emptively allocate resources that can ultimately reduce postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Li said. Sema4 is launching a prospective clinical trial to further assess the algorithm, she added.

Finding the continuum of risk

Holly Ende, MD, an obstetric anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said approaches that leverage electronic health records to identify women at risk for hemorrhage have many advantages over currently used tools.

“Machine learning models or statistical models are able to take into account many more risk factors and weigh each of those risk factors based on how much they contribute to risk,” Dr. Ende, who was not involved in the new studies, told this news organization. “We can stratify women more on a continuum.”

But digital approaches have potential downsides.

“Machine learning algorithms can be developed in such a way that perpetuates racial bias, and it’s important to be aware of potential biases in coded algorithms,” Dr. Li said. To help reduce such bias, they used a database that included a racially and ethnically diverse patient population, but she acknowledged that additional research is needed.

Dr. Ende, the coauthor of a commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology on risk assessment for postpartum hemorrhage, said algorithm developers must be sensitive to pre-existing disparities in health care that may affect the data they use to build the software.

She pointed to uterine atony – a known risk factor for hemorrhage – as an example. In her own research, she and her colleagues identified women with atony by searching their medical records for medications used to treat the condition. But when they ran their model, Black women were less likely to develop uterine atony, which the team knew wasn’t true in the real world. They traced the problem to an existing disparity in obstetric care: Black women with uterine atony were less likely than women of other races to receive medications for the condition.

“People need to be cognizant as they are developing these types of prediction models and be extremely careful to avoid perpetuating any disparities in care,” Dr. Ende cautioned. On the other hand, if carefully developed, these tools might also help reduce disparities in health care by standardizing risk stratification and clinical practices, she said.

In addition to independent validation of data-based risk prediction tools, Dr. Ende said ensuring that clinicians are properly trained to use these tools is crucial.

“Implementation may be the biggest limitation,” she said.

Dr. Ende and Dr. Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This doc still supports NP/PA-led care ... with caveats

Two years ago, I argued that independent care from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) would not have ill effects on health outcomes. To the surprise of no one, NPs and PAs embraced the argument; physicians clobbered it.

My case had three pegs: One was that medicine isn’t rocket science and clinicians control a lot less than we think we do. The second peg was that technology levels the playing field of clinical care. High-sensitivity troponin assays, for instance, make missing MI a lot less likely. The third peg was empirical: Studies have found little difference in MD versus non–MD-led care. Looking back, I now see empiricism as the weakest part of the argument because the studies had so many limitations.

I update this viewpoint now because health care is increasingly delivered by NPs and PAs. And there are two concerning trends regarding NP education and experience. First is that nurses are turning to advanced practitioner training earlier in their careers – without gathering much bedside experience. And these training programs are increasingly likely to be online, with minimal hands-on clinical tutoring.

Education and experience pop in my head often. Not every day, but many days I think back to my lucky 7 years in Indiana learning under the supervision of master clinicians – at a time when trainees were allowed the leeway to make decisions ... and mistakes. Then, when I joined private practice, I continued to learn from experienced practitioners.

It would be foolish to argue that training and experience aren’t important.

But here’s the thing:

I will make three points: First, I will bolster two of my old arguments as to why we shouldn’t be worried about non-MD clinicians, then I will propose some ideas to increase confidence in NP and PA care.

Health care does not equal health

On the matter of how much clinicians affect outcomes, a recently published randomized controlled trial performed in India found that subsidizing insurance care led to increased utilization of hospital services but had no significant effect on health outcomes. This follows the RAND and Oregon Health Insurance studies in the United States, which largely reported similar results.

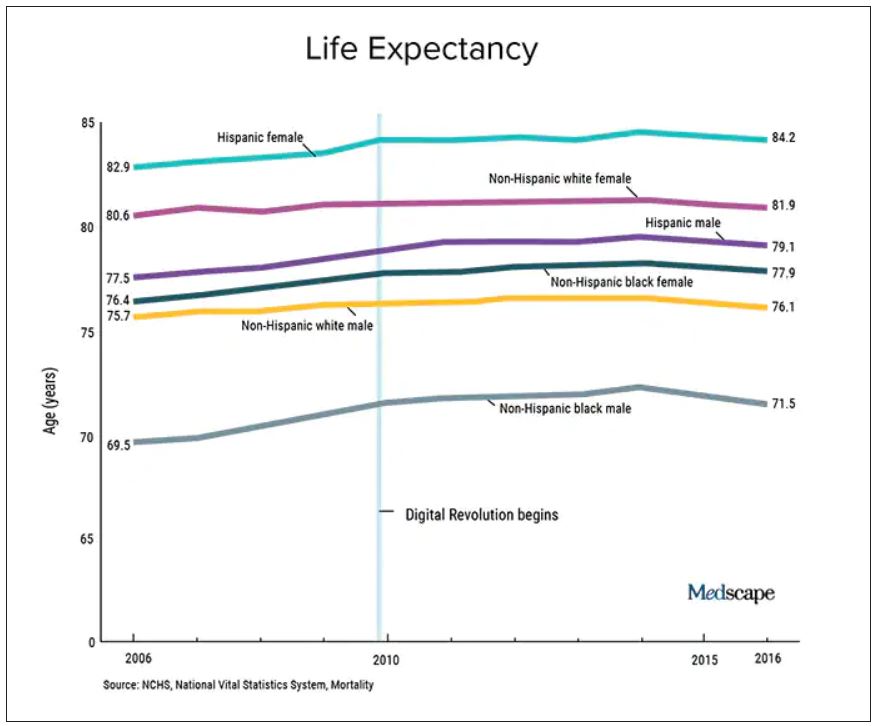

We should also not dismiss the fact that – despite the massive technology gains over the past half-century in digital health and artificial intelligence and increased use of quality measures, new drugs and procedures, and mega-medical centers – the average lifespan of Americans is flat to declining (in most ethnic and racial groups). Worse than no gains in longevity, perhaps, is that death from diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s disease are on the rise.

A neutral Martian would look down and wonder why all this health care hasn’t translated to longer and better lives. The causes of this paradox remain speculative, and are for another column, but the point remains that – on average – more health care is clearly not delivering more health. And if that is true, one may deduce that much of U.S. health care is marginal when it comes to affecting major outcomes.

It’s about the delta

Logos trumps pathos. Sure, my physician colleagues can tell scary anecdotes of bad outcomes caused by an inexperienced NP or PA. I would counter that by saying I have sat on our hospital’s peer review committee for 2 decades, including the era before NPs or PAs were practicing, and I have plenty of stories of physician errors. These include, of course, my own errors.

Logos: We must consider the difference between non–MD-led care and MD-led care.

My arguments from 2020 remain relevant today. Most medical problems are not engineering puzzles. Many, perhaps most, patients fall into an easy protocol – say, chest pain, dyspnea, or atrial fibrillation. With basic training, a motivated serious person quickly gains skill in recognizing and treating everyday problems.

And just 2 years on, technology further levels the playing field. Consider radiology in 2022 – it’s easy to take for granted the speed of the CT scan, the fidelity of the MRI, and the easy access to both in the U.S. hospital system. Less experienced clinicians have never had more tools to assist with diagnostics and therapeutics.

The expansion of team-based care has also mitigated the effects of inexperience. It took Americans longer than Canadians to figure out how helpful pharmacists could be. Pharmacists in my hospital now help us dose complicated medicines and protect us against prescribing errors.

Then there is the immediate access to online information. Gone are the days when you had to memorize long-QT syndromes. Book knowledge – that I spent years acquiring – now comes in seconds. The other day an NP corrected me. I asked, Are you sure? Boom, she took out her phone and showed me the evidence.

In sum, if it were even possible to measure the clinical competence of care from NP and PA versus physicians, there would be two bell-shaped curves with a tremendous amount of overlap. And that overlap would steadily increase as a given NP or PA gathered experience. (The NP in our electrophysiology division has more than 25 years’ experience in heart rhythm care, and it is common for colleagues to call her before one of us docs. Rightly so.)

Three basic proposals regarding NP and PA care

To ensure quality of care, I have three proposals.

It has always seemed strange to me that an NP or PA can flip from one field to another without a period of training. I can’t just change practice from electrophysiology to dermatology without doing a residency. But NPs and PAs can.

My first proposal would be that NPs and PAs spend a substantial period of training in a field before practice – a legit apprenticeship. The duration of this period is a matter of debate, but it ought to be standardized.

My second proposal is that, if physicians are required to pass certification exams, so should NPs. (PAs have an exam every 10 years.) The exam should be the same as (or very similar to) the physician exam, and it should be specific to their field of practice.

While I have argued (and still feel) that the American Board of Internal Medicine brand of certification is dubious, the fact remains that physicians must maintain proficiency in their field. Requiring NPs and PAs to do the same would help foster specialization. And while I can’t cite empirical evidence, specialization seems super-important. We have NPs at my hospital who have been in the same area for years, and they exude clinical competence.

Finally, I have come to believe that the best way for nearly any clinician to practice medicine is as part of a team. (The exception being primary care in rural areas where there are clinician shortages.)

On the matter of team care, I’ve practiced for a long time, but nearly every day I run situations by a colleague; often this person is an NP. The economist Friedrich Hayek proposed that dispersed knowledge always outpaces the wisdom of any individual. That notion pertains well to the increasing complexities and specialization of modern medical practice.

A person who commits to learning one area of medicine, enjoys helping people, asks often for help, and has the support of colleagues is set up to be a successful clinician – whether the letters after their name are APRN, PA, DO, or MD.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years ago, I argued that independent care from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) would not have ill effects on health outcomes. To the surprise of no one, NPs and PAs embraced the argument; physicians clobbered it.

My case had three pegs: One was that medicine isn’t rocket science and clinicians control a lot less than we think we do. The second peg was that technology levels the playing field of clinical care. High-sensitivity troponin assays, for instance, make missing MI a lot less likely. The third peg was empirical: Studies have found little difference in MD versus non–MD-led care. Looking back, I now see empiricism as the weakest part of the argument because the studies had so many limitations.

I update this viewpoint now because health care is increasingly delivered by NPs and PAs. And there are two concerning trends regarding NP education and experience. First is that nurses are turning to advanced practitioner training earlier in their careers – without gathering much bedside experience. And these training programs are increasingly likely to be online, with minimal hands-on clinical tutoring.

Education and experience pop in my head often. Not every day, but many days I think back to my lucky 7 years in Indiana learning under the supervision of master clinicians – at a time when trainees were allowed the leeway to make decisions ... and mistakes. Then, when I joined private practice, I continued to learn from experienced practitioners.

It would be foolish to argue that training and experience aren’t important.

But here’s the thing:

I will make three points: First, I will bolster two of my old arguments as to why we shouldn’t be worried about non-MD clinicians, then I will propose some ideas to increase confidence in NP and PA care.

Health care does not equal health