User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Postpartum HCV treatment rare in infected mothers with opioid use disorder

Despite the availability of effective direct-acting antivirals, very few a mothers with opioid use disorder (OUD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) during pregnancy received follow-up care or treatment for the infection within 6 months of giving birth, a retrospective study of Medicaid maternity patients found.

The study pooled data on 23,780 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD who had a live or stillbirth during 2016-2019 and were followed for 6 months after delivery. Among these women – drawn from six states in the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network – the pooled average probability of HCV testing during pregnancy was 70.3% (95% confidence interval, 61.5%-79.1%). Of these, 30.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-38%) tested positive. At 60 days postpartum, just 3.2% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.8%) had a follow-up visit or treatment for HCV. In a subset of patients followed for 6 months, only 5.9% (95% CI, 4.9%-6.9%) had any HCV follow-up visit or medication within 6 months of delivery.

While HCV screening and diagnosis rates varied across states, postpartum follow-up rates were universally low. The results suggest a need to improve the cascade of postpartum care for HCV and, ultimately perhaps, introduce antenatal HCV treatment, as is currently given safely for HIV, if current clinical research establishes safety, according to Marian P. Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. The study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

HCV infection has risen substantially in people of reproductive age in tandem with an increase in OUDs. HCV is transmitted from an infected mother to her baby in about 6% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in 2020 expanded its HCV screening recommendations to include all pregnant women. Currently no treatment for HCV during pregnancy has been approved.

In light of those recent recommendations, Dr. Jarlenski said in an interview that her group was “interested in looking at high-risk screened people and estimating what proportion received follow-up care and treatment for HCV. What is the promise of screening? The promise is that you can treat. Otherwise why screen?”

She acknowledged, however, that the postpartum period is a challenging time for a mother to seek health information or care for herself, whether she’s a new parent or has other children in the home. Nevertheless, the low rate of follow-up and treatment was unexpected. “Even the 70% rate of screening was low – we felt it should have been closer to 100% – but the follow-up rate was surprisingly low,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, medical director of Friends Research Institute in Baltimore, was not surprised at the low follow-up rate. “The cascade of care for hep C is demoralizing,” said Dr. Terplan, who was not involved in the study. “We know that hep C is syndemic with OUD and other opioid crises and we know that screening is effective for identifying hep C and that antiviral medications are now more effective and less toxic than ever before. But despite this, we’re failing pregnant women and their kids at every step along the cascade. We do a better job with initial testing than with the follow-up testing. We do a horrible job with postpartum medication initiation.”

He pointed to the systemic challenges mothers face in getting postpartum HCV care. “They may be transferred to a subspecialist for treatment, and this transfer is compounded by issues of insurance coverage and eligibility.” With the onus on new mothers to submit the paperwork, “the idea that mothers would be able to initiate much less continue postpartum treatment is absurd,” Dr. Terplan said.

He added that the children born to HCV-positive mothers need surveillance as well, but data suggest that the rates of newborn testing are also low. “There’s a preventable public health burden in all of this.”

The obvious way to increase eradicative therapy would be to treat women while they are getting antenatal care. A small phase 1 trial found that all pregnant participants who were HCV positive and given antivirals in their second trimester were safely treated and gave birth to healthy babies.

“If larger trials prove this treatment is safe and effective, then these results should be communicated to care providers and pregnant patients,” Dr. Jarlenski said. Otherwise, the public health potential of universal screening in pregnancy will not be realized.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and by the Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance and the University of Delaware, Center for Community Research & Service. Dr. Jarlenski disclosed no competing interests. One coauthor disclosed grant funding through her institution from Gilead Sciences and Organon unrelated to this work. Dr. Terplan reported no relevant competing interests.

Despite the availability of effective direct-acting antivirals, very few a mothers with opioid use disorder (OUD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) during pregnancy received follow-up care or treatment for the infection within 6 months of giving birth, a retrospective study of Medicaid maternity patients found.

The study pooled data on 23,780 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD who had a live or stillbirth during 2016-2019 and were followed for 6 months after delivery. Among these women – drawn from six states in the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network – the pooled average probability of HCV testing during pregnancy was 70.3% (95% confidence interval, 61.5%-79.1%). Of these, 30.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-38%) tested positive. At 60 days postpartum, just 3.2% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.8%) had a follow-up visit or treatment for HCV. In a subset of patients followed for 6 months, only 5.9% (95% CI, 4.9%-6.9%) had any HCV follow-up visit or medication within 6 months of delivery.

While HCV screening and diagnosis rates varied across states, postpartum follow-up rates were universally low. The results suggest a need to improve the cascade of postpartum care for HCV and, ultimately perhaps, introduce antenatal HCV treatment, as is currently given safely for HIV, if current clinical research establishes safety, according to Marian P. Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. The study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

HCV infection has risen substantially in people of reproductive age in tandem with an increase in OUDs. HCV is transmitted from an infected mother to her baby in about 6% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in 2020 expanded its HCV screening recommendations to include all pregnant women. Currently no treatment for HCV during pregnancy has been approved.

In light of those recent recommendations, Dr. Jarlenski said in an interview that her group was “interested in looking at high-risk screened people and estimating what proportion received follow-up care and treatment for HCV. What is the promise of screening? The promise is that you can treat. Otherwise why screen?”

She acknowledged, however, that the postpartum period is a challenging time for a mother to seek health information or care for herself, whether she’s a new parent or has other children in the home. Nevertheless, the low rate of follow-up and treatment was unexpected. “Even the 70% rate of screening was low – we felt it should have been closer to 100% – but the follow-up rate was surprisingly low,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, medical director of Friends Research Institute in Baltimore, was not surprised at the low follow-up rate. “The cascade of care for hep C is demoralizing,” said Dr. Terplan, who was not involved in the study. “We know that hep C is syndemic with OUD and other opioid crises and we know that screening is effective for identifying hep C and that antiviral medications are now more effective and less toxic than ever before. But despite this, we’re failing pregnant women and their kids at every step along the cascade. We do a better job with initial testing than with the follow-up testing. We do a horrible job with postpartum medication initiation.”

He pointed to the systemic challenges mothers face in getting postpartum HCV care. “They may be transferred to a subspecialist for treatment, and this transfer is compounded by issues of insurance coverage and eligibility.” With the onus on new mothers to submit the paperwork, “the idea that mothers would be able to initiate much less continue postpartum treatment is absurd,” Dr. Terplan said.

He added that the children born to HCV-positive mothers need surveillance as well, but data suggest that the rates of newborn testing are also low. “There’s a preventable public health burden in all of this.”

The obvious way to increase eradicative therapy would be to treat women while they are getting antenatal care. A small phase 1 trial found that all pregnant participants who were HCV positive and given antivirals in their second trimester were safely treated and gave birth to healthy babies.

“If larger trials prove this treatment is safe and effective, then these results should be communicated to care providers and pregnant patients,” Dr. Jarlenski said. Otherwise, the public health potential of universal screening in pregnancy will not be realized.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and by the Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance and the University of Delaware, Center for Community Research & Service. Dr. Jarlenski disclosed no competing interests. One coauthor disclosed grant funding through her institution from Gilead Sciences and Organon unrelated to this work. Dr. Terplan reported no relevant competing interests.

Despite the availability of effective direct-acting antivirals, very few a mothers with opioid use disorder (OUD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) during pregnancy received follow-up care or treatment for the infection within 6 months of giving birth, a retrospective study of Medicaid maternity patients found.

The study pooled data on 23,780 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD who had a live or stillbirth during 2016-2019 and were followed for 6 months after delivery. Among these women – drawn from six states in the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network – the pooled average probability of HCV testing during pregnancy was 70.3% (95% confidence interval, 61.5%-79.1%). Of these, 30.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-38%) tested positive. At 60 days postpartum, just 3.2% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.8%) had a follow-up visit or treatment for HCV. In a subset of patients followed for 6 months, only 5.9% (95% CI, 4.9%-6.9%) had any HCV follow-up visit or medication within 6 months of delivery.

While HCV screening and diagnosis rates varied across states, postpartum follow-up rates were universally low. The results suggest a need to improve the cascade of postpartum care for HCV and, ultimately perhaps, introduce antenatal HCV treatment, as is currently given safely for HIV, if current clinical research establishes safety, according to Marian P. Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. The study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

HCV infection has risen substantially in people of reproductive age in tandem with an increase in OUDs. HCV is transmitted from an infected mother to her baby in about 6% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in 2020 expanded its HCV screening recommendations to include all pregnant women. Currently no treatment for HCV during pregnancy has been approved.

In light of those recent recommendations, Dr. Jarlenski said in an interview that her group was “interested in looking at high-risk screened people and estimating what proportion received follow-up care and treatment for HCV. What is the promise of screening? The promise is that you can treat. Otherwise why screen?”

She acknowledged, however, that the postpartum period is a challenging time for a mother to seek health information or care for herself, whether she’s a new parent or has other children in the home. Nevertheless, the low rate of follow-up and treatment was unexpected. “Even the 70% rate of screening was low – we felt it should have been closer to 100% – but the follow-up rate was surprisingly low,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, medical director of Friends Research Institute in Baltimore, was not surprised at the low follow-up rate. “The cascade of care for hep C is demoralizing,” said Dr. Terplan, who was not involved in the study. “We know that hep C is syndemic with OUD and other opioid crises and we know that screening is effective for identifying hep C and that antiviral medications are now more effective and less toxic than ever before. But despite this, we’re failing pregnant women and their kids at every step along the cascade. We do a better job with initial testing than with the follow-up testing. We do a horrible job with postpartum medication initiation.”

He pointed to the systemic challenges mothers face in getting postpartum HCV care. “They may be transferred to a subspecialist for treatment, and this transfer is compounded by issues of insurance coverage and eligibility.” With the onus on new mothers to submit the paperwork, “the idea that mothers would be able to initiate much less continue postpartum treatment is absurd,” Dr. Terplan said.

He added that the children born to HCV-positive mothers need surveillance as well, but data suggest that the rates of newborn testing are also low. “There’s a preventable public health burden in all of this.”

The obvious way to increase eradicative therapy would be to treat women while they are getting antenatal care. A small phase 1 trial found that all pregnant participants who were HCV positive and given antivirals in their second trimester were safely treated and gave birth to healthy babies.

“If larger trials prove this treatment is safe and effective, then these results should be communicated to care providers and pregnant patients,” Dr. Jarlenski said. Otherwise, the public health potential of universal screening in pregnancy will not be realized.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and by the Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance and the University of Delaware, Center for Community Research & Service. Dr. Jarlenski disclosed no competing interests. One coauthor disclosed grant funding through her institution from Gilead Sciences and Organon unrelated to this work. Dr. Terplan reported no relevant competing interests.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

How common is IUD perforation, expulsion, and malposition?

The medicated intrauterine devices (IUDs), including the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD) (Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta) and the copper IUD (Cu-IUD; Paragard), are remarkably effective contraceptives. For the 52-mg LNG-IUD (Mirena, Liletta) the pregnancy rate over 6 years of use averaged less than 0.2% per year.1,2 For the Cu-IUD, the pregnancy rate over 10 years of use averaged 0.5% per year for the first 3 years of use and 0.2% per year over the following 7 years of use.3 IUD perforation of the uterus, expulsion, and malposition are recognized complications of IUD use. Our understanding of the prevalence and management of malpositioned IUDs is evolving and the main focus of this editorial.

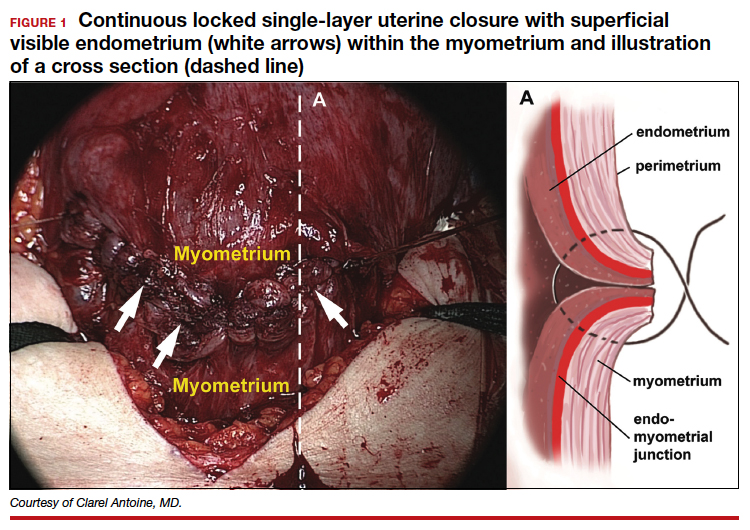

Complete and partial uterus perforation

A complete uterine perforation occurs when the entire IUD is outside the walls of the uterus. A partial uterine perforation occurs when the IUD is outside the uterine cavity, but a portion of the IUD remains in the myometrium. When uterine perforation is suspected, ultrasound can determine if the IUD is properly sited within the uterus. If ultrasonography does not detect the IUD within the uterus, an x-ray of the pelvis and abdomen should be obtained to determine if the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity. If both an ultrasound and a pelvic-abdominal x-ray do not detect the IUD, the IUD was probably expelled from the patient.

Uterine perforation is uncommon and occurs once in every 500 to 1,000 insertions in non-breastfeeding women.4-8 The most common symptoms reported by patients with a perforated IUD are pain and/or bleeding.8 Investigators in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices (EURAS) enrolled more than 60,000 patients who had an IUD insertion and followed them for 12 months with more than 39,000 followed for up to 60 months.7,8 The uterine perforation rate per 1,000 IUD insertions in non-breastfeeding women with 60 months of follow-up was 1.6 for the LNG-IUD and 0.8 for the Cu-IUD.8 The rate of uterine perforation was much higher in women who are breastfeeding or recently postpartum. In the EURAS study after 60 months of follow-up, the perforation rate per 1,000 insertions among breastfeeding women was 7.9 for the LNG-IUS and 4.7 for the Cu-IUD.8

Remarkably very few IUD perforations were detected at the time of insertion, including only 2% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 17% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Many perforations were not detected until more than 12 months following insertion, including 32% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 22% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Obviously, an IUD that has completely perforated the uterus and resides in the peritoneal cavity is not an effective contraceptive. For some patients, the IUD perforation was initially diagnosed after they became pregnant, and imaging studies to locate the IUD and assess the pregnancy were initiated. Complete perforation is usually treated with laparoscopy to remove the IUD and reduce the risk of injury to intra-abdominal organs.

Patients with an IUD partial perforation may present with pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding.9 An ultrasound study to explore the cause of the presenting symptom may detect the partial perforation. It is estimated that approximately 20% of cases of IUD perforation are partial perforation.9 Over time, a partial perforation may progress to a complete perforation. In some cases of partial perforation, the IUD string may still be visible in the cervix, and the IUD may be removed by pulling on the strings.8 Hysteroscopy and/or laparoscopy may be needed to remove a partially perforated IUD. Following a partial or complete IUD perforation, if the patient desires to continue with IUD contraception, it would be wise to insert a new IUD under ultrasound guidance or assess proper placement with a postplacement ultrasound.

Continue to: Expulsion...

Expulsion

IUD expulsion occurs in approximately 3% to 11% of patients.10-13 The age of the patient influences the rate of expulsion. In a study of 2,748 patients with a Cu-IUD, the rate of expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, and ≥35 years was 8.2%, 3.2%, 3.0%, 2.3%, and 1.8%, respectively.10 In this study, age did not influence the rate of IUD removal for pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding, which was 4% to 5% across all age groups.10 In a study of 5,403 patients with an IUD, the rate of IUD expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–29 years, and 30–45 years was 14.6%, 7.3%, and 7.2%, respectively.12 In this study, the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion was 10.2%.12 There was no statistically significant difference in the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion for the 52-mg LNG-IUD (10.1%) and Cu-IUD (10.7%).12

The majority of patients who have an IUD expulsion recognize the event and seek additional contraception care. A few patients first recognize the IUD expulsion when they become pregnant, and imaging studies detect no IUD in the uterus or the peritoneal cavity. In a study of more than 17,000 patients using an LNG-IUD, 108 pregnancies were reported. Seven pregnancies occurred in patients who did not realize their IUD was expelled.14 Patients who have had an IUD expulsion and receive a new IUD are at increased risk for re-expulsion. For these patients, reinsertion of an IUD could be performed under ultrasound guidance to ensure and document optimal initial IUD position within the uterus, or ultrasound can be obtained postinsertion to document appropriate IUD position.

Malposition—prevalence and management

Our understanding of the prevalence and management of a malpositioned IUD is evolving. For the purposes of this discussion a malpositioned IUD is defined as being in the uterus, but not properly positioned within the uterine cavity. Perforation into the peritoneal cavity and complete expulsion of an IUD are considered separate entities. However, a malpositioned IUD within the uterus may eventually perforate the uterus or be expelled from the body. For example, an IUD embedded in the uterine wall may eventually work its way through the wall and become perforated, residing in the peritoneal cavity. An IUD with the stem in the cervix below the internal os may eventually be expelled from the uterus and leave the body through the vagina.

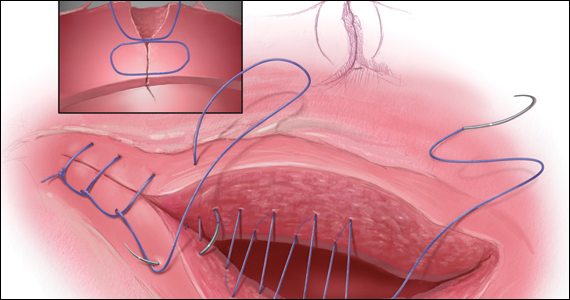

High-quality ultrasonography, including 2-dimensional (2-D) ultrasound with videoclips or 3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasound with coronal views, has greatly advanced our understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of a malpositioned IUD.15-18 Ultrasound features of an IUD correctly placed within the uterus include:

- the IUD is in the uterus

- the shaft is in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the shaft of the IUD is not in the endocervix

- the IUD arms are at a 90-degree angle from the shaft

- the top of the IUD is within 2 cm of the fundus

- the IUD is not rotated outside of the cornual plane, inverted or transverse.

Ultrasound imaging has identified multiple types of malpositioned IUDs, including:

- IUD embedded in the myometrium—a portion of the IUD is embedded in the uterine wall

- low-lying IUD—the IUD is low in the uterine cavity but not in the endocervix

- IUD in the endocervix—the stem is in the endocervical canal

- rotated—the IUD is rotated outside the cornual plane

- malpositioned arms—the arms are not at a 90-degree angle to the stem

- the IUD is inverted, transverse, or laterally displaced.

IUD malposition is highly prevalent and has been identified in 10% to 20% of convenience cohorts in which an ultrasound study was performed.15-18

Benacerraf, Shipp, and Bromley were among the first experts to use ultrasound to detect the high prevalence of malpositioned IUDs among a convenience sample of 167 patients with an IUD undergoing ultrasound for a variety of indications. Using 3-D ultrasound, including reconstructed coronal views, they identified 28 patients (17%) with a malpositioned IUD based on the detection of the IUD “poking into the substance of the uterus or cervix.” Among the patients with a malpositioned IUD, the principal indication for the ultrasound study was pelvic pain (39%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (36%). Among women with a normally sited IUD, pelvic pain (19%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (15%) were less often the principal indication for the ultrasound.15 The malpositioned IUD was removed in 21 of the 28 cases and the symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding resolved in 20 of the 21 patients.15

Other investigators have confirmed the observation that IUD malposition is common.16-18 In a retrospective study of 1,748 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was present, after excluding 13 patients who were determined to have expelled their IUD (13) and 13 patients with a perforated IUD, 156 patients (8.9%) were diagnosed as having a malpositioned IUD.16 IUD malposition was diagnosed when the IUD was in the uterus but positioned in the lower uterine segment, cervix, rotated or embedded in the uterus. An IUD in the lower uterine segment or cervix was detected in 133 patients, representing 85% of cases. Among these cases, 29 IUDs were also embedded and/or rotated, indicating that some IUDs have multiple causes of the malposition. Twenty-one IUDs were near the fundus but embedded and/or rotated. Controls with a normally-sited IUD were selected for comparison to the case group. Among IUD users, the identification of suspected adenomyosis on the ultrasound was associated with an increased risk of IUD malposition (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08-8.52).16 In this study, removal of a malpositioned LNG-IUD, without initiating a highly reliable contraceptive was associated with an increased risk of pregnancy. It is important to initiate a highly reliable form of contraception if the plan is to remove a malpositioned IUD.16,19

In a study of 1,253 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was identified in the uterus, 263 IUDs (19%) were determined to be malpositioned.17 In this study the location of the malpositioned IUDs included17:

- the lower uterine segment not extending into the cervix (38%)

- in the lower uterine segment extending into the cervix (22%)

- in the cervix (26%)

- rotated axis of the IUD (12%)

- other (2%).

Among the 236 malpositioned IUDs, 24% appeared to be embedded in the uterine wall.17 Compared with patients with a normally-sited IUD on ultrasound, patients with a malpositioned IUD more frequently reported vaginal bleeding (30% vs 19%; P<.005) and pelvic pain (43% vs 30%; P<.002), similar to the findings in the Benacerraf et al. study.14

Connolly and Fox18 designed an innovative study to determine the rate of malpositioned IUDs using 2-D ultrasound to ensure proper IUD placement at the time of insertion with a follow-up 3-D ultrasound 8 weeks after insertion to assess IUD position within the uterus. At the 8-week 3-D ultrasound, among 763 women, 16.6% of the IUDs were malpositioned.18 In this study, IUD position was determined to be correct if all the following features were identified:

- the IUD shaft was in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the IUD arms were at 90 degrees from the stem

- the top of the IUD was within 3 to 4 mm of the fundus

- the IUD was not rotated, inverted or transverse.

IUD malpositions were categorized as:

- embedded in the uterine wall

- low in the uterine cavity

- in the endocervical canal

- misaligned

- perforated

- expulsed.

At the 8-week follow-up, 636 patients (83.4%) had an IUD that was correctly positioned.18 In 127 patients (16.6%) IUD malposition was identified, with some patients having more than one type of malposition. The types of malposition identified were:

- embedded in the myometrium (54%)

- misaligned, including rotated, laterally displaced, inverted, transverse or arms not deployed (47%)

- low in the uterine cavity (39%)

- in the endocervical canal (14%)

- perforated (3%)

- expulsion (0%).

Recall that all of these patients had a 2-D ultrasound at the time of insertion that identified the IUD as correctly placed. This suggests that during the 8 weeks following IUD placement there were changes in the location of the IUD or that 2-D ultrasound has lower sensitivity than 3-D ultrasound to detect malposition. Of note, at the 8-week follow-up, bleeding or pain was reported by 36% of the patients with a malpositioned IUD and 20% of patients with a correctly positioned IUD.17 Sixty-seven of the 127 malpositioned IUDs “required” removal, but the precise reasons for the removals were not delineated. The investigators concluded that 3-D ultrasonography is useful for the detection of IUD malposition and could be considered as part of ongoing IUD care, if symptoms of pain or bleeding occur.18

Continue to: IUD malposition following postplacental insertion...

IUD malposition following postplacental insertion

IUD malposition is common in patients who have had a postplacental insertion. Ultrasound imaging plays an important role in detecting IUD expulsion and malposition in these cases. Postplacental IUD insertion is defined as the placement of an IUD within 10 minutes following delivery of the placenta. Postplacental IUD insertion can be performed following a vaginal or cesarean birth and with a Cu-IUD or LNG-IUD. The good news is that postplacental IUD insertion reduces the risk of unplanned pregnancy in the years following birth. However, postplacental IUD insertion is associated with a high rate of IUD malposition.

In a study of 162 patients who had postplacental insertion of a Cu-IUD following a vaginal birth, ultrasound and physical examination at 6 months demonstrated complete IUD expulsion in 8%, partial expulsion in 16%, and malposition in 15%.20 The IUD was correctly sited in 56% of patients. Seven patients (4%) had the IUD removed, and 1 patient had a perforated IUD. Among the 25 malpositioned IUDs, 14 were not within 1 cm of the fundus, and 11 were rotated outside of the axis of the cornuas. In this study partial expulsion was defined as an IUD protruding from the external cervical os on physical exam or demonstration of the distal tip of the IUD below the internal os of the cervix on ultrasound. Malposition was defined as an IUD that was >1 cm from the fundus or in an abnormal location or axis, but not partially expelled.

In a study of 69 patients who had postplacental insertion of a Cu-IUD following a cesarean birth, ultrasound and physical examination at 6 months demonstrated complete IUD expulsion in 3%, partial expulsion (stem in the cervix below the internal os) in 4% and malposition in 30%.20 The IUD was correctly positioned in 59% of the patients.21 The IUD had been electively removed in 3%. Among the 21 patients with a malpositioned IUD, 10 were rotated within the uterine cavity, 6 were inverted (upside down), 3 were low-lying, and 2 were transverse.21 Given the relatively high rate of IUD malposition following postplacental insertion, it may be useful to perform a pelvic ultrasound at a postpartum visit to assess the location of the IUD, if ultrasonography is available.

Management of the malpositioned IUD

There are no consensus guidelines on how to care for a patient with a malpositioned IUD. Clinicians need to use their best judgment and engage the patient in joint decision making when managing a malpositioned IUD. When an IUD is malpositioned and the patient has bothersome symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding that have not responded to standard interventions, consideration may be given to a remove and replace strategy. When the stem of the IUD is below the level of the internal os on ultrasound or visible at the external os on physical examination, consideration should be given to removing and replacing the IUD. However, if the IUD is removed without replacement or the initiation of a highly reliable contraceptive, the risk of unplanned pregnancy is considerable.16,19

IUD totally or partially within the cervix or low-lying. When an IUD is in the cervix, the contraceptive efficacy of the IUD may be diminished, especially with a Cu-IUD.22 In these cases, removing and replacing the IUD is an option. In a survey of 20 expert clinicians, >80% recommended replacing an IUD that was totally or partially in the cervical canal.23 But most of the experts would not replace an IUD that was incidentally noted on ultrasound to be low-lying, being positioned more than 2 cm below the fundus, with no portion of the IUD in the cervical canal. In the same survey, for patients with a low-lying IUD and pelvic pain or bleeding, the majority of experts reported that they would explore other causes of bleeding and pelvic pain not related to the IUD itself and not replace the IUD, but 30% of the experts reported that they would remove and replace the device.23

IUD embedded in the myometrium with pelvic pain. Based on my clinical experience, when a patient has persistent pelvic pain following the insertion of an IUD and the pain does not resolve with standard measures including medication, an ultrasound study is warranted to assess the position of the IUD. If the ultrasound demonstrates that an arm of the IUD is embedded in the myometrium, removal of the IUD may be associated with resolution of the pain. Reinsertion of an IUD under ultrasound guidance may result in a correctly-sited IUD with no recurrence of pelvic pain.

IUD rotated within the uterus with no pain or abnormal bleeding. For an IUD that is near the fundus and rotated on its axis within the uterus, if the patient has no symptoms of pain or abnormal bleeding, my recommendation to the patient would be to leave the device in situ.

Without available guidelines, engage in clinician-patient discussion

It is clear that IUD malposition is common, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with an IUD. High-quality ultrasound imaging is helpful in detecting IUD malposition, including 2-D ultrasound with videoclips and/or 3-D ultrasound with coronal reconstruction. More data are needed to identify the best options for managing various types of malpositioned IUDs in patients with and without bothersome symptoms such as pain and bleeding. Until consensus guidelines are developed, clinicians need to engage the patient in a discussion of how to best manage the malpositioned IUD. Medicated IUDs and progestin subdermal implants are our two most effective reversible contraceptives. They are among the most important advances in health care over the past half-century. ●

- Mirena FDA approval. , 2022.

- Liletta [package insert]. Allergan USA: Irvine, California; 2019. .

- Paragard [package insert]. CooperSurgical Inc: Trumbull, Connecticut; 2019. .

- Harrison-Woolrych M, Ashton J, Coulter D. Uterine perforation on intrauterine device insertion: is the incidence higher than previously reported? Contraception. 2003;67:53-56.

- Van Houdenhoven K, van Kaam KJAF, van Grootheest AC, et al. Uterine perforation in women using a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2006;73:257-260.

- van Grootheest K, Sachs B, Harrison-Woolrych M, et al. Uterine perforation with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Analysis of reports from four national pharmacovigilance centres. Drug Saf. 2011;34:83-88.

- Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

- Barnett C, Moehner S, Do Minh T, et al. Perforation risk and intra-uterine devices: results of the EURAS-IUD 5-year extension study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22:424-428.

- Zakin D, Stern WZ, Rosenblatt R. Complete and partial uterine perforation and embedding following insertion of intrauterine devices. I. Classification, complications, mechanism, incidence and missing string. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1981;36:335-353.

- Rivera R, Chen-Mok M, McMullen S. Analysis of client characteristics that may affect early discontinuation of the TCu-380A IUD. Contraception. 1999;60:155-160.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Madden T, McNichols, Zhao Q, et al. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:718-726.

- Keenahan L, Bercaw-Pratt JL, Adeyemi O, et al. Rates of intrauterine device expulsion among adolescents and young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34:362-365.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

- Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

- Gerkowicz SA, Fiorentino DG, Kovacs AP, et al. Uterine structural abnormality and intrauterine device malposition: analysis of ultrasonographic and demographic variables of 517 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:183.e1-e8.

- Connolly CT, Fox NS. Incidence and risk factors for a malpositioned intrauterine device detected on three-dimensional ultrasound within eight weeks of placement. J Ultrasound Med. 2021 ePub Sept 27 2021.

- Golightly E, Gebbie AE. Low-lying or malpositioned intrauterine devices and systems. J Fam Plann Reprod health Care. 2014;40:108-112.

- Gurney EP, Sonalkar S, McAllister A, et al. Six-month expulsion of postplacental copper intrauterine devices placed after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:183.e1-e9.

- Gurney EP, McAllister A, Lang B, et al. Ultrasound assessment of postplacental copper intrauterine device position 6 months after placement during cesarean delivery. Contraception. 2020;2:100040.

- Anteby E, Revel A, Ben-Chetrit A, et al. Intrauterine device failure: relation to its location with the uterine cavity. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:112-114.

- Golightly E, Gebbie AE. Clinicians’ views on low-lying intrauterine devices or systems. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40:113-116.

The medicated intrauterine devices (IUDs), including the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD) (Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta) and the copper IUD (Cu-IUD; Paragard), are remarkably effective contraceptives. For the 52-mg LNG-IUD (Mirena, Liletta) the pregnancy rate over 6 years of use averaged less than 0.2% per year.1,2 For the Cu-IUD, the pregnancy rate over 10 years of use averaged 0.5% per year for the first 3 years of use and 0.2% per year over the following 7 years of use.3 IUD perforation of the uterus, expulsion, and malposition are recognized complications of IUD use. Our understanding of the prevalence and management of malpositioned IUDs is evolving and the main focus of this editorial.

Complete and partial uterus perforation

A complete uterine perforation occurs when the entire IUD is outside the walls of the uterus. A partial uterine perforation occurs when the IUD is outside the uterine cavity, but a portion of the IUD remains in the myometrium. When uterine perforation is suspected, ultrasound can determine if the IUD is properly sited within the uterus. If ultrasonography does not detect the IUD within the uterus, an x-ray of the pelvis and abdomen should be obtained to determine if the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity. If both an ultrasound and a pelvic-abdominal x-ray do not detect the IUD, the IUD was probably expelled from the patient.

Uterine perforation is uncommon and occurs once in every 500 to 1,000 insertions in non-breastfeeding women.4-8 The most common symptoms reported by patients with a perforated IUD are pain and/or bleeding.8 Investigators in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices (EURAS) enrolled more than 60,000 patients who had an IUD insertion and followed them for 12 months with more than 39,000 followed for up to 60 months.7,8 The uterine perforation rate per 1,000 IUD insertions in non-breastfeeding women with 60 months of follow-up was 1.6 for the LNG-IUD and 0.8 for the Cu-IUD.8 The rate of uterine perforation was much higher in women who are breastfeeding or recently postpartum. In the EURAS study after 60 months of follow-up, the perforation rate per 1,000 insertions among breastfeeding women was 7.9 for the LNG-IUS and 4.7 for the Cu-IUD.8

Remarkably very few IUD perforations were detected at the time of insertion, including only 2% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 17% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Many perforations were not detected until more than 12 months following insertion, including 32% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 22% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Obviously, an IUD that has completely perforated the uterus and resides in the peritoneal cavity is not an effective contraceptive. For some patients, the IUD perforation was initially diagnosed after they became pregnant, and imaging studies to locate the IUD and assess the pregnancy were initiated. Complete perforation is usually treated with laparoscopy to remove the IUD and reduce the risk of injury to intra-abdominal organs.

Patients with an IUD partial perforation may present with pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding.9 An ultrasound study to explore the cause of the presenting symptom may detect the partial perforation. It is estimated that approximately 20% of cases of IUD perforation are partial perforation.9 Over time, a partial perforation may progress to a complete perforation. In some cases of partial perforation, the IUD string may still be visible in the cervix, and the IUD may be removed by pulling on the strings.8 Hysteroscopy and/or laparoscopy may be needed to remove a partially perforated IUD. Following a partial or complete IUD perforation, if the patient desires to continue with IUD contraception, it would be wise to insert a new IUD under ultrasound guidance or assess proper placement with a postplacement ultrasound.

Continue to: Expulsion...

Expulsion

IUD expulsion occurs in approximately 3% to 11% of patients.10-13 The age of the patient influences the rate of expulsion. In a study of 2,748 patients with a Cu-IUD, the rate of expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, and ≥35 years was 8.2%, 3.2%, 3.0%, 2.3%, and 1.8%, respectively.10 In this study, age did not influence the rate of IUD removal for pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding, which was 4% to 5% across all age groups.10 In a study of 5,403 patients with an IUD, the rate of IUD expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–29 years, and 30–45 years was 14.6%, 7.3%, and 7.2%, respectively.12 In this study, the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion was 10.2%.12 There was no statistically significant difference in the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion for the 52-mg LNG-IUD (10.1%) and Cu-IUD (10.7%).12

The majority of patients who have an IUD expulsion recognize the event and seek additional contraception care. A few patients first recognize the IUD expulsion when they become pregnant, and imaging studies detect no IUD in the uterus or the peritoneal cavity. In a study of more than 17,000 patients using an LNG-IUD, 108 pregnancies were reported. Seven pregnancies occurred in patients who did not realize their IUD was expelled.14 Patients who have had an IUD expulsion and receive a new IUD are at increased risk for re-expulsion. For these patients, reinsertion of an IUD could be performed under ultrasound guidance to ensure and document optimal initial IUD position within the uterus, or ultrasound can be obtained postinsertion to document appropriate IUD position.

Malposition—prevalence and management

Our understanding of the prevalence and management of a malpositioned IUD is evolving. For the purposes of this discussion a malpositioned IUD is defined as being in the uterus, but not properly positioned within the uterine cavity. Perforation into the peritoneal cavity and complete expulsion of an IUD are considered separate entities. However, a malpositioned IUD within the uterus may eventually perforate the uterus or be expelled from the body. For example, an IUD embedded in the uterine wall may eventually work its way through the wall and become perforated, residing in the peritoneal cavity. An IUD with the stem in the cervix below the internal os may eventually be expelled from the uterus and leave the body through the vagina.

High-quality ultrasonography, including 2-dimensional (2-D) ultrasound with videoclips or 3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasound with coronal views, has greatly advanced our understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of a malpositioned IUD.15-18 Ultrasound features of an IUD correctly placed within the uterus include:

- the IUD is in the uterus

- the shaft is in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the shaft of the IUD is not in the endocervix

- the IUD arms are at a 90-degree angle from the shaft

- the top of the IUD is within 2 cm of the fundus

- the IUD is not rotated outside of the cornual plane, inverted or transverse.

Ultrasound imaging has identified multiple types of malpositioned IUDs, including:

- IUD embedded in the myometrium—a portion of the IUD is embedded in the uterine wall

- low-lying IUD—the IUD is low in the uterine cavity but not in the endocervix

- IUD in the endocervix—the stem is in the endocervical canal

- rotated—the IUD is rotated outside the cornual plane

- malpositioned arms—the arms are not at a 90-degree angle to the stem

- the IUD is inverted, transverse, or laterally displaced.

IUD malposition is highly prevalent and has been identified in 10% to 20% of convenience cohorts in which an ultrasound study was performed.15-18

Benacerraf, Shipp, and Bromley were among the first experts to use ultrasound to detect the high prevalence of malpositioned IUDs among a convenience sample of 167 patients with an IUD undergoing ultrasound for a variety of indications. Using 3-D ultrasound, including reconstructed coronal views, they identified 28 patients (17%) with a malpositioned IUD based on the detection of the IUD “poking into the substance of the uterus or cervix.” Among the patients with a malpositioned IUD, the principal indication for the ultrasound study was pelvic pain (39%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (36%). Among women with a normally sited IUD, pelvic pain (19%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (15%) were less often the principal indication for the ultrasound.15 The malpositioned IUD was removed in 21 of the 28 cases and the symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding resolved in 20 of the 21 patients.15

Other investigators have confirmed the observation that IUD malposition is common.16-18 In a retrospective study of 1,748 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was present, after excluding 13 patients who were determined to have expelled their IUD (13) and 13 patients with a perforated IUD, 156 patients (8.9%) were diagnosed as having a malpositioned IUD.16 IUD malposition was diagnosed when the IUD was in the uterus but positioned in the lower uterine segment, cervix, rotated or embedded in the uterus. An IUD in the lower uterine segment or cervix was detected in 133 patients, representing 85% of cases. Among these cases, 29 IUDs were also embedded and/or rotated, indicating that some IUDs have multiple causes of the malposition. Twenty-one IUDs were near the fundus but embedded and/or rotated. Controls with a normally-sited IUD were selected for comparison to the case group. Among IUD users, the identification of suspected adenomyosis on the ultrasound was associated with an increased risk of IUD malposition (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08-8.52).16 In this study, removal of a malpositioned LNG-IUD, without initiating a highly reliable contraceptive was associated with an increased risk of pregnancy. It is important to initiate a highly reliable form of contraception if the plan is to remove a malpositioned IUD.16,19

In a study of 1,253 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was identified in the uterus, 263 IUDs (19%) were determined to be malpositioned.17 In this study the location of the malpositioned IUDs included17:

- the lower uterine segment not extending into the cervix (38%)

- in the lower uterine segment extending into the cervix (22%)

- in the cervix (26%)

- rotated axis of the IUD (12%)

- other (2%).

Among the 236 malpositioned IUDs, 24% appeared to be embedded in the uterine wall.17 Compared with patients with a normally-sited IUD on ultrasound, patients with a malpositioned IUD more frequently reported vaginal bleeding (30% vs 19%; P<.005) and pelvic pain (43% vs 30%; P<.002), similar to the findings in the Benacerraf et al. study.14

Connolly and Fox18 designed an innovative study to determine the rate of malpositioned IUDs using 2-D ultrasound to ensure proper IUD placement at the time of insertion with a follow-up 3-D ultrasound 8 weeks after insertion to assess IUD position within the uterus. At the 8-week 3-D ultrasound, among 763 women, 16.6% of the IUDs were malpositioned.18 In this study, IUD position was determined to be correct if all the following features were identified:

- the IUD shaft was in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the IUD arms were at 90 degrees from the stem

- the top of the IUD was within 3 to 4 mm of the fundus

- the IUD was not rotated, inverted or transverse.

IUD malpositions were categorized as:

- embedded in the uterine wall

- low in the uterine cavity

- in the endocervical canal

- misaligned

- perforated

- expulsed.

At the 8-week follow-up, 636 patients (83.4%) had an IUD that was correctly positioned.18 In 127 patients (16.6%) IUD malposition was identified, with some patients having more than one type of malposition. The types of malposition identified were:

- embedded in the myometrium (54%)

- misaligned, including rotated, laterally displaced, inverted, transverse or arms not deployed (47%)

- low in the uterine cavity (39%)

- in the endocervical canal (14%)

- perforated (3%)

- expulsion (0%).

Recall that all of these patients had a 2-D ultrasound at the time of insertion that identified the IUD as correctly placed. This suggests that during the 8 weeks following IUD placement there were changes in the location of the IUD or that 2-D ultrasound has lower sensitivity than 3-D ultrasound to detect malposition. Of note, at the 8-week follow-up, bleeding or pain was reported by 36% of the patients with a malpositioned IUD and 20% of patients with a correctly positioned IUD.17 Sixty-seven of the 127 malpositioned IUDs “required” removal, but the precise reasons for the removals were not delineated. The investigators concluded that 3-D ultrasonography is useful for the detection of IUD malposition and could be considered as part of ongoing IUD care, if symptoms of pain or bleeding occur.18

Continue to: IUD malposition following postplacental insertion...

IUD malposition following postplacental insertion

IUD malposition is common in patients who have had a postplacental insertion. Ultrasound imaging plays an important role in detecting IUD expulsion and malposition in these cases. Postplacental IUD insertion is defined as the placement of an IUD within 10 minutes following delivery of the placenta. Postplacental IUD insertion can be performed following a vaginal or cesarean birth and with a Cu-IUD or LNG-IUD. The good news is that postplacental IUD insertion reduces the risk of unplanned pregnancy in the years following birth. However, postplacental IUD insertion is associated with a high rate of IUD malposition.

In a study of 162 patients who had postplacental insertion of a Cu-IUD following a vaginal birth, ultrasound and physical examination at 6 months demonstrated complete IUD expulsion in 8%, partial expulsion in 16%, and malposition in 15%.20 The IUD was correctly sited in 56% of patients. Seven patients (4%) had the IUD removed, and 1 patient had a perforated IUD. Among the 25 malpositioned IUDs, 14 were not within 1 cm of the fundus, and 11 were rotated outside of the axis of the cornuas. In this study partial expulsion was defined as an IUD protruding from the external cervical os on physical exam or demonstration of the distal tip of the IUD below the internal os of the cervix on ultrasound. Malposition was defined as an IUD that was >1 cm from the fundus or in an abnormal location or axis, but not partially expelled.

In a study of 69 patients who had postplacental insertion of a Cu-IUD following a cesarean birth, ultrasound and physical examination at 6 months demonstrated complete IUD expulsion in 3%, partial expulsion (stem in the cervix below the internal os) in 4% and malposition in 30%.20 The IUD was correctly positioned in 59% of the patients.21 The IUD had been electively removed in 3%. Among the 21 patients with a malpositioned IUD, 10 were rotated within the uterine cavity, 6 were inverted (upside down), 3 were low-lying, and 2 were transverse.21 Given the relatively high rate of IUD malposition following postplacental insertion, it may be useful to perform a pelvic ultrasound at a postpartum visit to assess the location of the IUD, if ultrasonography is available.

Management of the malpositioned IUD

There are no consensus guidelines on how to care for a patient with a malpositioned IUD. Clinicians need to use their best judgment and engage the patient in joint decision making when managing a malpositioned IUD. When an IUD is malpositioned and the patient has bothersome symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding that have not responded to standard interventions, consideration may be given to a remove and replace strategy. When the stem of the IUD is below the level of the internal os on ultrasound or visible at the external os on physical examination, consideration should be given to removing and replacing the IUD. However, if the IUD is removed without replacement or the initiation of a highly reliable contraceptive, the risk of unplanned pregnancy is considerable.16,19

IUD totally or partially within the cervix or low-lying. When an IUD is in the cervix, the contraceptive efficacy of the IUD may be diminished, especially with a Cu-IUD.22 In these cases, removing and replacing the IUD is an option. In a survey of 20 expert clinicians, >80% recommended replacing an IUD that was totally or partially in the cervical canal.23 But most of the experts would not replace an IUD that was incidentally noted on ultrasound to be low-lying, being positioned more than 2 cm below the fundus, with no portion of the IUD in the cervical canal. In the same survey, for patients with a low-lying IUD and pelvic pain or bleeding, the majority of experts reported that they would explore other causes of bleeding and pelvic pain not related to the IUD itself and not replace the IUD, but 30% of the experts reported that they would remove and replace the device.23

IUD embedded in the myometrium with pelvic pain. Based on my clinical experience, when a patient has persistent pelvic pain following the insertion of an IUD and the pain does not resolve with standard measures including medication, an ultrasound study is warranted to assess the position of the IUD. If the ultrasound demonstrates that an arm of the IUD is embedded in the myometrium, removal of the IUD may be associated with resolution of the pain. Reinsertion of an IUD under ultrasound guidance may result in a correctly-sited IUD with no recurrence of pelvic pain.

IUD rotated within the uterus with no pain or abnormal bleeding. For an IUD that is near the fundus and rotated on its axis within the uterus, if the patient has no symptoms of pain or abnormal bleeding, my recommendation to the patient would be to leave the device in situ.

Without available guidelines, engage in clinician-patient discussion

It is clear that IUD malposition is common, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with an IUD. High-quality ultrasound imaging is helpful in detecting IUD malposition, including 2-D ultrasound with videoclips and/or 3-D ultrasound with coronal reconstruction. More data are needed to identify the best options for managing various types of malpositioned IUDs in patients with and without bothersome symptoms such as pain and bleeding. Until consensus guidelines are developed, clinicians need to engage the patient in a discussion of how to best manage the malpositioned IUD. Medicated IUDs and progestin subdermal implants are our two most effective reversible contraceptives. They are among the most important advances in health care over the past half-century. ●

The medicated intrauterine devices (IUDs), including the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD) (Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta) and the copper IUD (Cu-IUD; Paragard), are remarkably effective contraceptives. For the 52-mg LNG-IUD (Mirena, Liletta) the pregnancy rate over 6 years of use averaged less than 0.2% per year.1,2 For the Cu-IUD, the pregnancy rate over 10 years of use averaged 0.5% per year for the first 3 years of use and 0.2% per year over the following 7 years of use.3 IUD perforation of the uterus, expulsion, and malposition are recognized complications of IUD use. Our understanding of the prevalence and management of malpositioned IUDs is evolving and the main focus of this editorial.

Complete and partial uterus perforation

A complete uterine perforation occurs when the entire IUD is outside the walls of the uterus. A partial uterine perforation occurs when the IUD is outside the uterine cavity, but a portion of the IUD remains in the myometrium. When uterine perforation is suspected, ultrasound can determine if the IUD is properly sited within the uterus. If ultrasonography does not detect the IUD within the uterus, an x-ray of the pelvis and abdomen should be obtained to determine if the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity. If both an ultrasound and a pelvic-abdominal x-ray do not detect the IUD, the IUD was probably expelled from the patient.

Uterine perforation is uncommon and occurs once in every 500 to 1,000 insertions in non-breastfeeding women.4-8 The most common symptoms reported by patients with a perforated IUD are pain and/or bleeding.8 Investigators in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices (EURAS) enrolled more than 60,000 patients who had an IUD insertion and followed them for 12 months with more than 39,000 followed for up to 60 months.7,8 The uterine perforation rate per 1,000 IUD insertions in non-breastfeeding women with 60 months of follow-up was 1.6 for the LNG-IUD and 0.8 for the Cu-IUD.8 The rate of uterine perforation was much higher in women who are breastfeeding or recently postpartum. In the EURAS study after 60 months of follow-up, the perforation rate per 1,000 insertions among breastfeeding women was 7.9 for the LNG-IUS and 4.7 for the Cu-IUD.8

Remarkably very few IUD perforations were detected at the time of insertion, including only 2% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 17% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Many perforations were not detected until more than 12 months following insertion, including 32% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 22% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Obviously, an IUD that has completely perforated the uterus and resides in the peritoneal cavity is not an effective contraceptive. For some patients, the IUD perforation was initially diagnosed after they became pregnant, and imaging studies to locate the IUD and assess the pregnancy were initiated. Complete perforation is usually treated with laparoscopy to remove the IUD and reduce the risk of injury to intra-abdominal organs.

Patients with an IUD partial perforation may present with pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding.9 An ultrasound study to explore the cause of the presenting symptom may detect the partial perforation. It is estimated that approximately 20% of cases of IUD perforation are partial perforation.9 Over time, a partial perforation may progress to a complete perforation. In some cases of partial perforation, the IUD string may still be visible in the cervix, and the IUD may be removed by pulling on the strings.8 Hysteroscopy and/or laparoscopy may be needed to remove a partially perforated IUD. Following a partial or complete IUD perforation, if the patient desires to continue with IUD contraception, it would be wise to insert a new IUD under ultrasound guidance or assess proper placement with a postplacement ultrasound.

Continue to: Expulsion...

Expulsion

IUD expulsion occurs in approximately 3% to 11% of patients.10-13 The age of the patient influences the rate of expulsion. In a study of 2,748 patients with a Cu-IUD, the rate of expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, and ≥35 years was 8.2%, 3.2%, 3.0%, 2.3%, and 1.8%, respectively.10 In this study, age did not influence the rate of IUD removal for pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding, which was 4% to 5% across all age groups.10 In a study of 5,403 patients with an IUD, the rate of IUD expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–29 years, and 30–45 years was 14.6%, 7.3%, and 7.2%, respectively.12 In this study, the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion was 10.2%.12 There was no statistically significant difference in the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion for the 52-mg LNG-IUD (10.1%) and Cu-IUD (10.7%).12

The majority of patients who have an IUD expulsion recognize the event and seek additional contraception care. A few patients first recognize the IUD expulsion when they become pregnant, and imaging studies detect no IUD in the uterus or the peritoneal cavity. In a study of more than 17,000 patients using an LNG-IUD, 108 pregnancies were reported. Seven pregnancies occurred in patients who did not realize their IUD was expelled.14 Patients who have had an IUD expulsion and receive a new IUD are at increased risk for re-expulsion. For these patients, reinsertion of an IUD could be performed under ultrasound guidance to ensure and document optimal initial IUD position within the uterus, or ultrasound can be obtained postinsertion to document appropriate IUD position.

Malposition—prevalence and management

Our understanding of the prevalence and management of a malpositioned IUD is evolving. For the purposes of this discussion a malpositioned IUD is defined as being in the uterus, but not properly positioned within the uterine cavity. Perforation into the peritoneal cavity and complete expulsion of an IUD are considered separate entities. However, a malpositioned IUD within the uterus may eventually perforate the uterus or be expelled from the body. For example, an IUD embedded in the uterine wall may eventually work its way through the wall and become perforated, residing in the peritoneal cavity. An IUD with the stem in the cervix below the internal os may eventually be expelled from the uterus and leave the body through the vagina.

High-quality ultrasonography, including 2-dimensional (2-D) ultrasound with videoclips or 3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasound with coronal views, has greatly advanced our understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of a malpositioned IUD.15-18 Ultrasound features of an IUD correctly placed within the uterus include:

- the IUD is in the uterus

- the shaft is in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the shaft of the IUD is not in the endocervix

- the IUD arms are at a 90-degree angle from the shaft

- the top of the IUD is within 2 cm of the fundus

- the IUD is not rotated outside of the cornual plane, inverted or transverse.

Ultrasound imaging has identified multiple types of malpositioned IUDs, including:

- IUD embedded in the myometrium—a portion of the IUD is embedded in the uterine wall

- low-lying IUD—the IUD is low in the uterine cavity but not in the endocervix

- IUD in the endocervix—the stem is in the endocervical canal

- rotated—the IUD is rotated outside the cornual plane

- malpositioned arms—the arms are not at a 90-degree angle to the stem

- the IUD is inverted, transverse, or laterally displaced.

IUD malposition is highly prevalent and has been identified in 10% to 20% of convenience cohorts in which an ultrasound study was performed.15-18

Benacerraf, Shipp, and Bromley were among the first experts to use ultrasound to detect the high prevalence of malpositioned IUDs among a convenience sample of 167 patients with an IUD undergoing ultrasound for a variety of indications. Using 3-D ultrasound, including reconstructed coronal views, they identified 28 patients (17%) with a malpositioned IUD based on the detection of the IUD “poking into the substance of the uterus or cervix.” Among the patients with a malpositioned IUD, the principal indication for the ultrasound study was pelvic pain (39%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (36%). Among women with a normally sited IUD, pelvic pain (19%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (15%) were less often the principal indication for the ultrasound.15 The malpositioned IUD was removed in 21 of the 28 cases and the symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding resolved in 20 of the 21 patients.15

Other investigators have confirmed the observation that IUD malposition is common.16-18 In a retrospective study of 1,748 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was present, after excluding 13 patients who were determined to have expelled their IUD (13) and 13 patients with a perforated IUD, 156 patients (8.9%) were diagnosed as having a malpositioned IUD.16 IUD malposition was diagnosed when the IUD was in the uterus but positioned in the lower uterine segment, cervix, rotated or embedded in the uterus. An IUD in the lower uterine segment or cervix was detected in 133 patients, representing 85% of cases. Among these cases, 29 IUDs were also embedded and/or rotated, indicating that some IUDs have multiple causes of the malposition. Twenty-one IUDs were near the fundus but embedded and/or rotated. Controls with a normally-sited IUD were selected for comparison to the case group. Among IUD users, the identification of suspected adenomyosis on the ultrasound was associated with an increased risk of IUD malposition (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08-8.52).16 In this study, removal of a malpositioned LNG-IUD, without initiating a highly reliable contraceptive was associated with an increased risk of pregnancy. It is important to initiate a highly reliable form of contraception if the plan is to remove a malpositioned IUD.16,19

In a study of 1,253 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was identified in the uterus, 263 IUDs (19%) were determined to be malpositioned.17 In this study the location of the malpositioned IUDs included17:

- the lower uterine segment not extending into the cervix (38%)

- in the lower uterine segment extending into the cervix (22%)

- in the cervix (26%)

- rotated axis of the IUD (12%)

- other (2%).

Among the 236 malpositioned IUDs, 24% appeared to be embedded in the uterine wall.17 Compared with patients with a normally-sited IUD on ultrasound, patients with a malpositioned IUD more frequently reported vaginal bleeding (30% vs 19%; P<.005) and pelvic pain (43% vs 30%; P<.002), similar to the findings in the Benacerraf et al. study.14

Connolly and Fox18 designed an innovative study to determine the rate of malpositioned IUDs using 2-D ultrasound to ensure proper IUD placement at the time of insertion with a follow-up 3-D ultrasound 8 weeks after insertion to assess IUD position within the uterus. At the 8-week 3-D ultrasound, among 763 women, 16.6% of the IUDs were malpositioned.18 In this study, IUD position was determined to be correct if all the following features were identified:

- the IUD shaft was in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the IUD arms were at 90 degrees from the stem

- the top of the IUD was within 3 to 4 mm of the fundus

- the IUD was not rotated, inverted or transverse.

IUD malpositions were categorized as:

- embedded in the uterine wall

- low in the uterine cavity

- in the endocervical canal

- misaligned

- perforated

- expulsed.

At the 8-week follow-up, 636 patients (83.4%) had an IUD that was correctly positioned.18 In 127 patients (16.6%) IUD malposition was identified, with some patients having more than one type of malposition. The types of malposition identified were:

- embedded in the myometrium (54%)

- misaligned, including rotated, laterally displaced, inverted, transverse or arms not deployed (47%)

- low in the uterine cavity (39%)

- in the endocervical canal (14%)

- perforated (3%)

- expulsion (0%).

Recall that all of these patients had a 2-D ultrasound at the time of insertion that identified the IUD as correctly placed. This suggests that during the 8 weeks following IUD placement there were changes in the location of the IUD or that 2-D ultrasound has lower sensitivity than 3-D ultrasound to detect malposition. Of note, at the 8-week follow-up, bleeding or pain was reported by 36% of the patients with a malpositioned IUD and 20% of patients with a correctly positioned IUD.17 Sixty-seven of the 127 malpositioned IUDs “required” removal, but the precise reasons for the removals were not delineated. The investigators concluded that 3-D ultrasonography is useful for the detection of IUD malposition and could be considered as part of ongoing IUD care, if symptoms of pain or bleeding occur.18

Continue to: IUD malposition following postplacental insertion...

IUD malposition following postplacental insertion

IUD malposition is common in patients who have had a postplacental insertion. Ultrasound imaging plays an important role in detecting IUD expulsion and malposition in these cases. Postplacental IUD insertion is defined as the placement of an IUD within 10 minutes following delivery of the placenta. Postplacental IUD insertion can be performed following a vaginal or cesarean birth and with a Cu-IUD or LNG-IUD. The good news is that postplacental IUD insertion reduces the risk of unplanned pregnancy in the years following birth. However, postplacental IUD insertion is associated with a high rate of IUD malposition.

In a study of 162 patients who had postplacental insertion of a Cu-IUD following a vaginal birth, ultrasound and physical examination at 6 months demonstrated complete IUD expulsion in 8%, partial expulsion in 16%, and malposition in 15%.20 The IUD was correctly sited in 56% of patients. Seven patients (4%) had the IUD removed, and 1 patient had a perforated IUD. Among the 25 malpositioned IUDs, 14 were not within 1 cm of the fundus, and 11 were rotated outside of the axis of the cornuas. In this study partial expulsion was defined as an IUD protruding from the external cervical os on physical exam or demonstration of the distal tip of the IUD below the internal os of the cervix on ultrasound. Malposition was defined as an IUD that was >1 cm from the fundus or in an abnormal location or axis, but not partially expelled.

In a study of 69 patients who had postplacental insertion of a Cu-IUD following a cesarean birth, ultrasound and physical examination at 6 months demonstrated complete IUD expulsion in 3%, partial expulsion (stem in the cervix below the internal os) in 4% and malposition in 30%.20 The IUD was correctly positioned in 59% of the patients.21 The IUD had been electively removed in 3%. Among the 21 patients with a malpositioned IUD, 10 were rotated within the uterine cavity, 6 were inverted (upside down), 3 were low-lying, and 2 were transverse.21 Given the relatively high rate of IUD malposition following postplacental insertion, it may be useful to perform a pelvic ultrasound at a postpartum visit to assess the location of the IUD, if ultrasonography is available.

Management of the malpositioned IUD

There are no consensus guidelines on how to care for a patient with a malpositioned IUD. Clinicians need to use their best judgment and engage the patient in joint decision making when managing a malpositioned IUD. When an IUD is malpositioned and the patient has bothersome symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding that have not responded to standard interventions, consideration may be given to a remove and replace strategy. When the stem of the IUD is below the level of the internal os on ultrasound or visible at the external os on physical examination, consideration should be given to removing and replacing the IUD. However, if the IUD is removed without replacement or the initiation of a highly reliable contraceptive, the risk of unplanned pregnancy is considerable.16,19

IUD totally or partially within the cervix or low-lying. When an IUD is in the cervix, the contraceptive efficacy of the IUD may be diminished, especially with a Cu-IUD.22 In these cases, removing and replacing the IUD is an option. In a survey of 20 expert clinicians, >80% recommended replacing an IUD that was totally or partially in the cervical canal.23 But most of the experts would not replace an IUD that was incidentally noted on ultrasound to be low-lying, being positioned more than 2 cm below the fundus, with no portion of the IUD in the cervical canal. In the same survey, for patients with a low-lying IUD and pelvic pain or bleeding, the majority of experts reported that they would explore other causes of bleeding and pelvic pain not related to the IUD itself and not replace the IUD, but 30% of the experts reported that they would remove and replace the device.23

IUD embedded in the myometrium with pelvic pain. Based on my clinical experience, when a patient has persistent pelvic pain following the insertion of an IUD and the pain does not resolve with standard measures including medication, an ultrasound study is warranted to assess the position of the IUD. If the ultrasound demonstrates that an arm of the IUD is embedded in the myometrium, removal of the IUD may be associated with resolution of the pain. Reinsertion of an IUD under ultrasound guidance may result in a correctly-sited IUD with no recurrence of pelvic pain.

IUD rotated within the uterus with no pain or abnormal bleeding. For an IUD that is near the fundus and rotated on its axis within the uterus, if the patient has no symptoms of pain or abnormal bleeding, my recommendation to the patient would be to leave the device in situ.

Without available guidelines, engage in clinician-patient discussion

It is clear that IUD malposition is common, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients with an IUD. High-quality ultrasound imaging is helpful in detecting IUD malposition, including 2-D ultrasound with videoclips and/or 3-D ultrasound with coronal reconstruction. More data are needed to identify the best options for managing various types of malpositioned IUDs in patients with and without bothersome symptoms such as pain and bleeding. Until consensus guidelines are developed, clinicians need to engage the patient in a discussion of how to best manage the malpositioned IUD. Medicated IUDs and progestin subdermal implants are our two most effective reversible contraceptives. They are among the most important advances in health care over the past half-century. ●

- Mirena FDA approval. , 2022.

- Liletta [package insert]. Allergan USA: Irvine, California; 2019. .

- Paragard [package insert]. CooperSurgical Inc: Trumbull, Connecticut; 2019. .

- Harrison-Woolrych M, Ashton J, Coulter D. Uterine perforation on intrauterine device insertion: is the incidence higher than previously reported? Contraception. 2003;67:53-56.

- Van Houdenhoven K, van Kaam KJAF, van Grootheest AC, et al. Uterine perforation in women using a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2006;73:257-260.

- van Grootheest K, Sachs B, Harrison-Woolrych M, et al. Uterine perforation with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Analysis of reports from four national pharmacovigilance centres. Drug Saf. 2011;34:83-88.

- Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

- Barnett C, Moehner S, Do Minh T, et al. Perforation risk and intra-uterine devices: results of the EURAS-IUD 5-year extension study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22:424-428.

- Zakin D, Stern WZ, Rosenblatt R. Complete and partial uterine perforation and embedding following insertion of intrauterine devices. I. Classification, complications, mechanism, incidence and missing string. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1981;36:335-353.

- Rivera R, Chen-Mok M, McMullen S. Analysis of client characteristics that may affect early discontinuation of the TCu-380A IUD. Contraception. 1999;60:155-160.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Madden T, McNichols, Zhao Q, et al. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:718-726.

- Keenahan L, Bercaw-Pratt JL, Adeyemi O, et al. Rates of intrauterine device expulsion among adolescents and young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34:362-365.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

- Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

- Gerkowicz SA, Fiorentino DG, Kovacs AP, et al. Uterine structural abnormality and intrauterine device malposition: analysis of ultrasonographic and demographic variables of 517 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:183.e1-e8.

- Connolly CT, Fox NS. Incidence and risk factors for a malpositioned intrauterine device detected on three-dimensional ultrasound within eight weeks of placement. J Ultrasound Med. 2021 ePub Sept 27 2021.

- Golightly E, Gebbie AE. Low-lying or malpositioned intrauterine devices and systems. J Fam Plann Reprod health Care. 2014;40:108-112.