User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Capivasertib/fulvestrant improves progression free survival in breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2–) breast cancers resistant to aromatase inhibitors, the combination of the investigational AKT inhibitor capivasertib with the selective estrogen receptor degrader fulvestrant (Faslodex) was associated with significant improvement in progression-free survival compared with fulvestrant alone in the CAPItelllo-291 study recently presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

, reported Nicholas Turner, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in London.

“Capivasertib plus fulvestrant has the potential to be a future treatment option for patients with hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer who have progressed on an endocrine-based regimen,” he said.

AKT alterations

Many HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancers have activation of the AKT pathway through alteration in PIK3CA, AKT1, and PTEN, but this activation can also occur in the absence of genetic alterations. AKT signaling is also a mechanism of resistance to endocrine therapy, Dr. Turner said.

Capivasertib, a select inhibitor of the AKT isoforms 1, 2, and 3, was combined with fulvestrant in the phase 2 FAKTION trial. The combination was associated with significant improvements in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with fulvestrant plus placebo in CDK4/6-naive postmenopausal women with aromatase inhibitor–resistant HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer. The clinical benefit in this trial was more pronounced among patients with tumors bearing AKT pathway alterations, he said.

In the phase 3 CAPItello study, Dr. Turner and colleagues enrolled men and both pre- and postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer who experienced recurrence either during therapy with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor or within 12 months of the end of therapy, or who had disease progression while on prior aromatase inhibitor therapy for advanced breast cancer.

The patients could have no more than two prior lines of endocrine therapy and no more than one prior line of chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer, and no prior selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD), mTOR inhibitor, PI3K inhibitor, or AKT inhibitor. Patients with hemoglobin A1c below 8% and with diabetes not requiring insulin were eligible for the study. After stratification for liver metastases, prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, and geographic region, 708 patients were randomized to either capivasertib 400 mg twice daily 4 days on and 3 days off plus fulvestrant 500 mg on days 1 and 15 of cycle 1 and then every 4 weeks, or to fulvestrant in the same dose and schedule plus placebo.

Results

The dual primary endpoint was investigator assessed PFS in both the overall population and in those with AKT pathway alterations. The median PFS in the overall population was 7.2 months with the combination, compared with 3.6 months for fulvestrant alone, translating into an adjusted hazard ratio for progression of 0.60 (P < .001).

In the pathway-altered population, the median PFS was 7.3 months with capivasertib/fulvestrant vs. 3.1 months with fulvestrant placebo, which translated into an adjusted hazard ratio for progression on the combination of 0.50 (P < .001).

An exploratory analysis of PFS among patients either without pathway alterations or unknown AKT status showed median PFS of 7.2 months and 3.7 months, respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.70.

An analysis of benefit by subgroups in the overall population showed that the balance tipped in favor of the combination in nearly all categories, including among patients with or without liver metastases and with or without prior CDK4/6 inhibitor use.

Among patients with measurable disease at baseline the combination was associated with objective response rates (ORR) of 22.9% in the overall population and 28.8% in the pathway-altered population. The respective ORR for fulvestrant/placebo were 12.2% and 9.7%.

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of data cutoff, but showed trends favoring capivasertib plus fulvestrant in both the overall and AKT-pathway-altered population.

There were four fatal adverse events in the combination arm (acute myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, pneumonia aspiration, and sepsis), and one in the fulvestrant alone arm (COVID-19).

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events among patients treated with the combination were rash (12.1%), diarrhea (9.3 %), and hyperglycemia (2.3%). In all, 13% of patients randomized to capivasertib/fulvestrant discontinued therapy due to adverse events, compared with 2.3% of patients assigned to fulvestrant/placebo.

Dr. Turner said that the overall adverse event profile with the combination was manageable and consistent with data from previous studies.

‘Clinically relevant benefit’

Invited discussant Fabrice André, MD, PhD, of Gustave Roussy Cancer Center in Villejuif, France, noted that the CAPItello-291 study is one of the first randomized trials enriched with patients whose tumors are resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors.

“What are the take-home messages? First, there is a clinically relevant benefit in the overall population and in the PIK3CA mutant/AKT/PTEN altered population,” he said.

He noted that the exploratory analysis showed a small clinical benefit with an impressive hazard ratio but broad confidence interval in patients with biomarker-negative tumors, and noted that the study lacked either circulating tumor DNA analysis or exploration of other mechanisms of AKT pathway alteration.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Turner has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca, and his institution has received research funding from the company. Dr. Andre disclosed fees to his hospital on his behalf from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Pfizer, Lilly, and Roche.

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2–) breast cancers resistant to aromatase inhibitors, the combination of the investigational AKT inhibitor capivasertib with the selective estrogen receptor degrader fulvestrant (Faslodex) was associated with significant improvement in progression-free survival compared with fulvestrant alone in the CAPItelllo-291 study recently presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

, reported Nicholas Turner, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in London.

“Capivasertib plus fulvestrant has the potential to be a future treatment option for patients with hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer who have progressed on an endocrine-based regimen,” he said.

AKT alterations

Many HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancers have activation of the AKT pathway through alteration in PIK3CA, AKT1, and PTEN, but this activation can also occur in the absence of genetic alterations. AKT signaling is also a mechanism of resistance to endocrine therapy, Dr. Turner said.

Capivasertib, a select inhibitor of the AKT isoforms 1, 2, and 3, was combined with fulvestrant in the phase 2 FAKTION trial. The combination was associated with significant improvements in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with fulvestrant plus placebo in CDK4/6-naive postmenopausal women with aromatase inhibitor–resistant HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer. The clinical benefit in this trial was more pronounced among patients with tumors bearing AKT pathway alterations, he said.

In the phase 3 CAPItello study, Dr. Turner and colleagues enrolled men and both pre- and postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer who experienced recurrence either during therapy with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor or within 12 months of the end of therapy, or who had disease progression while on prior aromatase inhibitor therapy for advanced breast cancer.

The patients could have no more than two prior lines of endocrine therapy and no more than one prior line of chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer, and no prior selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD), mTOR inhibitor, PI3K inhibitor, or AKT inhibitor. Patients with hemoglobin A1c below 8% and with diabetes not requiring insulin were eligible for the study. After stratification for liver metastases, prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, and geographic region, 708 patients were randomized to either capivasertib 400 mg twice daily 4 days on and 3 days off plus fulvestrant 500 mg on days 1 and 15 of cycle 1 and then every 4 weeks, or to fulvestrant in the same dose and schedule plus placebo.

Results

The dual primary endpoint was investigator assessed PFS in both the overall population and in those with AKT pathway alterations. The median PFS in the overall population was 7.2 months with the combination, compared with 3.6 months for fulvestrant alone, translating into an adjusted hazard ratio for progression of 0.60 (P < .001).

In the pathway-altered population, the median PFS was 7.3 months with capivasertib/fulvestrant vs. 3.1 months with fulvestrant placebo, which translated into an adjusted hazard ratio for progression on the combination of 0.50 (P < .001).

An exploratory analysis of PFS among patients either without pathway alterations or unknown AKT status showed median PFS of 7.2 months and 3.7 months, respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.70.

An analysis of benefit by subgroups in the overall population showed that the balance tipped in favor of the combination in nearly all categories, including among patients with or without liver metastases and with or without prior CDK4/6 inhibitor use.

Among patients with measurable disease at baseline the combination was associated with objective response rates (ORR) of 22.9% in the overall population and 28.8% in the pathway-altered population. The respective ORR for fulvestrant/placebo were 12.2% and 9.7%.

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of data cutoff, but showed trends favoring capivasertib plus fulvestrant in both the overall and AKT-pathway-altered population.

There were four fatal adverse events in the combination arm (acute myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, pneumonia aspiration, and sepsis), and one in the fulvestrant alone arm (COVID-19).

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events among patients treated with the combination were rash (12.1%), diarrhea (9.3 %), and hyperglycemia (2.3%). In all, 13% of patients randomized to capivasertib/fulvestrant discontinued therapy due to adverse events, compared with 2.3% of patients assigned to fulvestrant/placebo.

Dr. Turner said that the overall adverse event profile with the combination was manageable and consistent with data from previous studies.

‘Clinically relevant benefit’

Invited discussant Fabrice André, MD, PhD, of Gustave Roussy Cancer Center in Villejuif, France, noted that the CAPItello-291 study is one of the first randomized trials enriched with patients whose tumors are resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors.

“What are the take-home messages? First, there is a clinically relevant benefit in the overall population and in the PIK3CA mutant/AKT/PTEN altered population,” he said.

He noted that the exploratory analysis showed a small clinical benefit with an impressive hazard ratio but broad confidence interval in patients with biomarker-negative tumors, and noted that the study lacked either circulating tumor DNA analysis or exploration of other mechanisms of AKT pathway alteration.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Turner has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca, and his institution has received research funding from the company. Dr. Andre disclosed fees to his hospital on his behalf from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Pfizer, Lilly, and Roche.

SAN ANTONIO – For patients with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2–) breast cancers resistant to aromatase inhibitors, the combination of the investigational AKT inhibitor capivasertib with the selective estrogen receptor degrader fulvestrant (Faslodex) was associated with significant improvement in progression-free survival compared with fulvestrant alone in the CAPItelllo-291 study recently presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

, reported Nicholas Turner, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in London.

“Capivasertib plus fulvestrant has the potential to be a future treatment option for patients with hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer who have progressed on an endocrine-based regimen,” he said.

AKT alterations

Many HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancers have activation of the AKT pathway through alteration in PIK3CA, AKT1, and PTEN, but this activation can also occur in the absence of genetic alterations. AKT signaling is also a mechanism of resistance to endocrine therapy, Dr. Turner said.

Capivasertib, a select inhibitor of the AKT isoforms 1, 2, and 3, was combined with fulvestrant in the phase 2 FAKTION trial. The combination was associated with significant improvements in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with fulvestrant plus placebo in CDK4/6-naive postmenopausal women with aromatase inhibitor–resistant HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer. The clinical benefit in this trial was more pronounced among patients with tumors bearing AKT pathway alterations, he said.

In the phase 3 CAPItello study, Dr. Turner and colleagues enrolled men and both pre- and postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer who experienced recurrence either during therapy with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor or within 12 months of the end of therapy, or who had disease progression while on prior aromatase inhibitor therapy for advanced breast cancer.

The patients could have no more than two prior lines of endocrine therapy and no more than one prior line of chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer, and no prior selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD), mTOR inhibitor, PI3K inhibitor, or AKT inhibitor. Patients with hemoglobin A1c below 8% and with diabetes not requiring insulin were eligible for the study. After stratification for liver metastases, prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, and geographic region, 708 patients were randomized to either capivasertib 400 mg twice daily 4 days on and 3 days off plus fulvestrant 500 mg on days 1 and 15 of cycle 1 and then every 4 weeks, or to fulvestrant in the same dose and schedule plus placebo.

Results

The dual primary endpoint was investigator assessed PFS in both the overall population and in those with AKT pathway alterations. The median PFS in the overall population was 7.2 months with the combination, compared with 3.6 months for fulvestrant alone, translating into an adjusted hazard ratio for progression of 0.60 (P < .001).

In the pathway-altered population, the median PFS was 7.3 months with capivasertib/fulvestrant vs. 3.1 months with fulvestrant placebo, which translated into an adjusted hazard ratio for progression on the combination of 0.50 (P < .001).

An exploratory analysis of PFS among patients either without pathway alterations or unknown AKT status showed median PFS of 7.2 months and 3.7 months, respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.70.

An analysis of benefit by subgroups in the overall population showed that the balance tipped in favor of the combination in nearly all categories, including among patients with or without liver metastases and with or without prior CDK4/6 inhibitor use.

Among patients with measurable disease at baseline the combination was associated with objective response rates (ORR) of 22.9% in the overall population and 28.8% in the pathway-altered population. The respective ORR for fulvestrant/placebo were 12.2% and 9.7%.

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of data cutoff, but showed trends favoring capivasertib plus fulvestrant in both the overall and AKT-pathway-altered population.

There were four fatal adverse events in the combination arm (acute myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, pneumonia aspiration, and sepsis), and one in the fulvestrant alone arm (COVID-19).

The most common grade 3 or greater adverse events among patients treated with the combination were rash (12.1%), diarrhea (9.3 %), and hyperglycemia (2.3%). In all, 13% of patients randomized to capivasertib/fulvestrant discontinued therapy due to adverse events, compared with 2.3% of patients assigned to fulvestrant/placebo.

Dr. Turner said that the overall adverse event profile with the combination was manageable and consistent with data from previous studies.

‘Clinically relevant benefit’

Invited discussant Fabrice André, MD, PhD, of Gustave Roussy Cancer Center in Villejuif, France, noted that the CAPItello-291 study is one of the first randomized trials enriched with patients whose tumors are resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors.

“What are the take-home messages? First, there is a clinically relevant benefit in the overall population and in the PIK3CA mutant/AKT/PTEN altered population,” he said.

He noted that the exploratory analysis showed a small clinical benefit with an impressive hazard ratio but broad confidence interval in patients with biomarker-negative tumors, and noted that the study lacked either circulating tumor DNA analysis or exploration of other mechanisms of AKT pathway alteration.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Turner has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca, and his institution has received research funding from the company. Dr. Andre disclosed fees to his hospital on his behalf from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Pfizer, Lilly, and Roche.

AT SABCS 2022

Gene signature may spare some breast cancer patients from radiation

San Antonio – as well as those who can be safely spared from breast radiation following breast-conserving surgery, an international team of investigators said.

In combined data from three independent randomized trials grouped into a meta-analysis, patients who had low scores on the messenger RNA–based signature, dubbed “Profile for the Omission of Local Adjuvant Radiotherapy” (POLAR), derived only minimal benefit from radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery. In contrast, patients with high POLAR scores had significant clinical benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy, reported Per Karlsson, MD, chief physician with the Sahlgrenska Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). Dr. Karlsson reported his findings at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“To our knowledge, POLAR is the first genomic classifier that is not only prognostic but also predictive of radiotherapy benefit, showing a significant interaction between radiotherapy and the classifier,” he said. “These important retrospective findings warrant further investigation, including in contemporary clinical studies.”

Investigators with the Swedish SweBCG91RT trial (Swedish Breast Cancer Group 91 Radiotherapy), the Scottish Conservation (radiotherapy) Trial (SCT), and a trial from the Princess Margaret Cancer Hospital in Toronto, collaborated on improving and validating the POLAR signature, which was originally developed for use in the SweBCG91RT trial in patients with lymph node–negative breast cancer who underwent breast-conserving surgery. The patients were randomized to whole breast irradiation or no radiotherapy.

To develop the signature, researchers collected tumor blocks from 1,004 patients, and extracted RNA from the samples. Gene expression data were obtained from primary tumors of 764 patients. The subset of 597 patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative tumors (ER+/HER2–) who did not receive systemic therapy were divided into a training set with 243 patients, and a validation cohort with 354 patients.

They identified a total of 16 genes involved in cellular proliferation and immune response, and then validated the signature using retrospective data from three clinical trials of patients randomized to radiotherapy or no radiation following breast-conserving surgery.

Of 623 patients with node-negative ER+/HER2– tumors who were included in the meta-analysis, 429 patients were found to have high POLAR scores. These patients benefited from adjuvant radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery with a 10-year cumulative incidence of low risk of locoregional recurrence ranging from 15% to 26% for those who were not treated with radiation therapy, compared with only 4%-11% percent for those who received radiation therapy (hazard ratio, 0.37; P < .001).

In contrast, among the 194 patients whose tumors had POLAR low scores, there was no apparent benefit from radiation therapy with a nonsignificant HR of 0.92 (P = .832).

In Cox proportional hazard models for time to locoregional recurrences for 309 patients who did not undergo radiation, POLAR scores were significantly prognostic for recurrence, with a HR of 1.53 (P < .001) in univariable analysis, and 1.43 (P = .005) in multivariable analysis controlling for age, tumor size, tumor grade and molecular groupings.

New modalities may make findings less relevant

Alphonse Taghian, MD, PhD, a breast radiation oncologist with Mass General Cancer Center, Boston, who was not involved in the study, said there have been major changes in radiation therapy since the studies used for development of the POLAR signature were performed. For example, the Scottish Conservation Trial ran from 1985 to 1991, while the SweBCGR91RT trial and Princess Margaret trial were both conducted in the 1990s.

He noted that patients in those studies would likely experience more morbidities from radiation than patients treated with more recent modalities such as intensity modulated radiation therapy, and that patients treated 30 years ago would have to put up with lengthy fractionation schedules that required daily trips to the hospital over as long as 6 weeks, whereas a majority of patients can now be treated with hypofractionated radiation that can be performed in a much shorter time and with minimal comorbidities.

He acknowledged, however, that “it will help to have a signature proved, confirmed, or validated retrospectively with a different set of data.”

Dr. Taghian also said that it would be helpful to have more data about the age of patients, because omitting radiation is more common for elderly patients than it is for younger patients.

“It will maybe be beneficial to look at this signature in patients that we think might not need radiation,” he said.

The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council, King Gustav 5 Jubilee Clinic Foundation, the ALF Agreement of the Swedish government, PFS Genomics, and Exact Sciences. Dr. Karlsson has pending patents with and receives royalties from Exact Sciences and PreludeDX. Dr. Taghian reported having no relevant disclosures.

San Antonio – as well as those who can be safely spared from breast radiation following breast-conserving surgery, an international team of investigators said.

In combined data from three independent randomized trials grouped into a meta-analysis, patients who had low scores on the messenger RNA–based signature, dubbed “Profile for the Omission of Local Adjuvant Radiotherapy” (POLAR), derived only minimal benefit from radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery. In contrast, patients with high POLAR scores had significant clinical benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy, reported Per Karlsson, MD, chief physician with the Sahlgrenska Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). Dr. Karlsson reported his findings at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“To our knowledge, POLAR is the first genomic classifier that is not only prognostic but also predictive of radiotherapy benefit, showing a significant interaction between radiotherapy and the classifier,” he said. “These important retrospective findings warrant further investigation, including in contemporary clinical studies.”

Investigators with the Swedish SweBCG91RT trial (Swedish Breast Cancer Group 91 Radiotherapy), the Scottish Conservation (radiotherapy) Trial (SCT), and a trial from the Princess Margaret Cancer Hospital in Toronto, collaborated on improving and validating the POLAR signature, which was originally developed for use in the SweBCG91RT trial in patients with lymph node–negative breast cancer who underwent breast-conserving surgery. The patients were randomized to whole breast irradiation or no radiotherapy.

To develop the signature, researchers collected tumor blocks from 1,004 patients, and extracted RNA from the samples. Gene expression data were obtained from primary tumors of 764 patients. The subset of 597 patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative tumors (ER+/HER2–) who did not receive systemic therapy were divided into a training set with 243 patients, and a validation cohort with 354 patients.

They identified a total of 16 genes involved in cellular proliferation and immune response, and then validated the signature using retrospective data from three clinical trials of patients randomized to radiotherapy or no radiation following breast-conserving surgery.

Of 623 patients with node-negative ER+/HER2– tumors who were included in the meta-analysis, 429 patients were found to have high POLAR scores. These patients benefited from adjuvant radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery with a 10-year cumulative incidence of low risk of locoregional recurrence ranging from 15% to 26% for those who were not treated with radiation therapy, compared with only 4%-11% percent for those who received radiation therapy (hazard ratio, 0.37; P < .001).

In contrast, among the 194 patients whose tumors had POLAR low scores, there was no apparent benefit from radiation therapy with a nonsignificant HR of 0.92 (P = .832).

In Cox proportional hazard models for time to locoregional recurrences for 309 patients who did not undergo radiation, POLAR scores were significantly prognostic for recurrence, with a HR of 1.53 (P < .001) in univariable analysis, and 1.43 (P = .005) in multivariable analysis controlling for age, tumor size, tumor grade and molecular groupings.

New modalities may make findings less relevant

Alphonse Taghian, MD, PhD, a breast radiation oncologist with Mass General Cancer Center, Boston, who was not involved in the study, said there have been major changes in radiation therapy since the studies used for development of the POLAR signature were performed. For example, the Scottish Conservation Trial ran from 1985 to 1991, while the SweBCGR91RT trial and Princess Margaret trial were both conducted in the 1990s.

He noted that patients in those studies would likely experience more morbidities from radiation than patients treated with more recent modalities such as intensity modulated radiation therapy, and that patients treated 30 years ago would have to put up with lengthy fractionation schedules that required daily trips to the hospital over as long as 6 weeks, whereas a majority of patients can now be treated with hypofractionated radiation that can be performed in a much shorter time and with minimal comorbidities.

He acknowledged, however, that “it will help to have a signature proved, confirmed, or validated retrospectively with a different set of data.”

Dr. Taghian also said that it would be helpful to have more data about the age of patients, because omitting radiation is more common for elderly patients than it is for younger patients.

“It will maybe be beneficial to look at this signature in patients that we think might not need radiation,” he said.

The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council, King Gustav 5 Jubilee Clinic Foundation, the ALF Agreement of the Swedish government, PFS Genomics, and Exact Sciences. Dr. Karlsson has pending patents with and receives royalties from Exact Sciences and PreludeDX. Dr. Taghian reported having no relevant disclosures.

San Antonio – as well as those who can be safely spared from breast radiation following breast-conserving surgery, an international team of investigators said.

In combined data from three independent randomized trials grouped into a meta-analysis, patients who had low scores on the messenger RNA–based signature, dubbed “Profile for the Omission of Local Adjuvant Radiotherapy” (POLAR), derived only minimal benefit from radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery. In contrast, patients with high POLAR scores had significant clinical benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy, reported Per Karlsson, MD, chief physician with the Sahlgrenska Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). Dr. Karlsson reported his findings at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“To our knowledge, POLAR is the first genomic classifier that is not only prognostic but also predictive of radiotherapy benefit, showing a significant interaction between radiotherapy and the classifier,” he said. “These important retrospective findings warrant further investigation, including in contemporary clinical studies.”

Investigators with the Swedish SweBCG91RT trial (Swedish Breast Cancer Group 91 Radiotherapy), the Scottish Conservation (radiotherapy) Trial (SCT), and a trial from the Princess Margaret Cancer Hospital in Toronto, collaborated on improving and validating the POLAR signature, which was originally developed for use in the SweBCG91RT trial in patients with lymph node–negative breast cancer who underwent breast-conserving surgery. The patients were randomized to whole breast irradiation or no radiotherapy.

To develop the signature, researchers collected tumor blocks from 1,004 patients, and extracted RNA from the samples. Gene expression data were obtained from primary tumors of 764 patients. The subset of 597 patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative tumors (ER+/HER2–) who did not receive systemic therapy were divided into a training set with 243 patients, and a validation cohort with 354 patients.

They identified a total of 16 genes involved in cellular proliferation and immune response, and then validated the signature using retrospective data from three clinical trials of patients randomized to radiotherapy or no radiation following breast-conserving surgery.

Of 623 patients with node-negative ER+/HER2– tumors who were included in the meta-analysis, 429 patients were found to have high POLAR scores. These patients benefited from adjuvant radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery with a 10-year cumulative incidence of low risk of locoregional recurrence ranging from 15% to 26% for those who were not treated with radiation therapy, compared with only 4%-11% percent for those who received radiation therapy (hazard ratio, 0.37; P < .001).

In contrast, among the 194 patients whose tumors had POLAR low scores, there was no apparent benefit from radiation therapy with a nonsignificant HR of 0.92 (P = .832).

In Cox proportional hazard models for time to locoregional recurrences for 309 patients who did not undergo radiation, POLAR scores were significantly prognostic for recurrence, with a HR of 1.53 (P < .001) in univariable analysis, and 1.43 (P = .005) in multivariable analysis controlling for age, tumor size, tumor grade and molecular groupings.

New modalities may make findings less relevant

Alphonse Taghian, MD, PhD, a breast radiation oncologist with Mass General Cancer Center, Boston, who was not involved in the study, said there have been major changes in radiation therapy since the studies used for development of the POLAR signature were performed. For example, the Scottish Conservation Trial ran from 1985 to 1991, while the SweBCGR91RT trial and Princess Margaret trial were both conducted in the 1990s.

He noted that patients in those studies would likely experience more morbidities from radiation than patients treated with more recent modalities such as intensity modulated radiation therapy, and that patients treated 30 years ago would have to put up with lengthy fractionation schedules that required daily trips to the hospital over as long as 6 weeks, whereas a majority of patients can now be treated with hypofractionated radiation that can be performed in a much shorter time and with minimal comorbidities.

He acknowledged, however, that “it will help to have a signature proved, confirmed, or validated retrospectively with a different set of data.”

Dr. Taghian also said that it would be helpful to have more data about the age of patients, because omitting radiation is more common for elderly patients than it is for younger patients.

“It will maybe be beneficial to look at this signature in patients that we think might not need radiation,” he said.

The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council, King Gustav 5 Jubilee Clinic Foundation, the ALF Agreement of the Swedish government, PFS Genomics, and Exact Sciences. Dr. Karlsson has pending patents with and receives royalties from Exact Sciences and PreludeDX. Dr. Taghian reported having no relevant disclosures.

AT SABCS 2022

Endometrial receptivity testing before IVF seen as unnecessary

Endometrial receptivity testing (ERT) did not increase the chances of achieving live birth in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization.

The study was promoted by widespread use of the tests in reproductive medicine and earlier conflicting studies regarding its effectiveness. The procedure, in which doctors extract cells from a woman’s endometrial lining in an effort to determine the best day to perform in vitro fertilization, requires a biopsy, can take a month to generate results, and costs up to $1,000.

But the new study, published online December 6 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that embryo transfer based on the timing of ERT was no better than that based on the standard protocol.

“Endometrial receptivity testing ended up not being beneficial in the population of interest, a good-prognosis IVF patient population,” said Nicole Doyle, MD, PhD, of Shady Grove Fertility, in Arlington, Va., who led the study. “For this particular patient population I would not recommend ERT based on the results of the trial.”

“Unfortunately, as is our history in reproductive medicine, we may embrace technology prematurely given patient desperation and physician eagerness to improve pregnancy outcomes,” said Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center in Orlando, who was not involved in the new research.

The double-blind, randomized clinical trial enrolled 726 women treated at Dr. Doyle’s clinic between May 2018 and September 2020.

All the women underwent ERT. Of those who received adjusted progesterone exposure after the test, live birth occurred in 58.5% of transfers (223 of 381). Among those in a control group who did not have their progesterone adjusted after ERT and underwent IVF on a standardized schedule, 61.9% of transfers (239 of 386) resulted in live birth, according to the researchers.

The differences in rates of clinical (77.2% vs. 79.5% [95% confidence interval, −10.4% to 2.4%]) and biochemical pregnancy (68.8% vs. 72.8% [95% CI, −8.2% to 3.5%]) were not statistically significant between the two groups, Dr. Doyle and her colleagues reported.

Women who experienced recurrent implantation failure (RIF), defined as more than two failed embryo transfers, were excluded from the study. “We can’t assess the benefit of an endometrial receptivity testing in this particular patient population,” Dr. Doyle said.

However, she noted that the number of women who undergo RIF is “a very small fraction of all IVF patients, less than 5%.” Of those, half are expected to have embryos that are not suitable for implantation, Dr. Doyle said.

As a result, she said, “it’s really only about 2.5% of IVF patients for which we don’t yet have an answer regarding the utility of ERT.”

Dr. Trolice, also a professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, expressed certainty that the “one-size-fits-all approach” for ERT has been disproven by the study’s failure to find a benefit from the procedure in women with a “good prognosis.” But, he added, whether ERT is of value in a subset of patients, such as those with recurrent implantation failure, remains “a question of vital importance.”

Dr. Doyle and Dr. Trolice reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endometrial receptivity testing (ERT) did not increase the chances of achieving live birth in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization.

The study was promoted by widespread use of the tests in reproductive medicine and earlier conflicting studies regarding its effectiveness. The procedure, in which doctors extract cells from a woman’s endometrial lining in an effort to determine the best day to perform in vitro fertilization, requires a biopsy, can take a month to generate results, and costs up to $1,000.

But the new study, published online December 6 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that embryo transfer based on the timing of ERT was no better than that based on the standard protocol.

“Endometrial receptivity testing ended up not being beneficial in the population of interest, a good-prognosis IVF patient population,” said Nicole Doyle, MD, PhD, of Shady Grove Fertility, in Arlington, Va., who led the study. “For this particular patient population I would not recommend ERT based on the results of the trial.”

“Unfortunately, as is our history in reproductive medicine, we may embrace technology prematurely given patient desperation and physician eagerness to improve pregnancy outcomes,” said Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center in Orlando, who was not involved in the new research.

The double-blind, randomized clinical trial enrolled 726 women treated at Dr. Doyle’s clinic between May 2018 and September 2020.

All the women underwent ERT. Of those who received adjusted progesterone exposure after the test, live birth occurred in 58.5% of transfers (223 of 381). Among those in a control group who did not have their progesterone adjusted after ERT and underwent IVF on a standardized schedule, 61.9% of transfers (239 of 386) resulted in live birth, according to the researchers.

The differences in rates of clinical (77.2% vs. 79.5% [95% confidence interval, −10.4% to 2.4%]) and biochemical pregnancy (68.8% vs. 72.8% [95% CI, −8.2% to 3.5%]) were not statistically significant between the two groups, Dr. Doyle and her colleagues reported.

Women who experienced recurrent implantation failure (RIF), defined as more than two failed embryo transfers, were excluded from the study. “We can’t assess the benefit of an endometrial receptivity testing in this particular patient population,” Dr. Doyle said.

However, she noted that the number of women who undergo RIF is “a very small fraction of all IVF patients, less than 5%.” Of those, half are expected to have embryos that are not suitable for implantation, Dr. Doyle said.

As a result, she said, “it’s really only about 2.5% of IVF patients for which we don’t yet have an answer regarding the utility of ERT.”

Dr. Trolice, also a professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, expressed certainty that the “one-size-fits-all approach” for ERT has been disproven by the study’s failure to find a benefit from the procedure in women with a “good prognosis.” But, he added, whether ERT is of value in a subset of patients, such as those with recurrent implantation failure, remains “a question of vital importance.”

Dr. Doyle and Dr. Trolice reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Endometrial receptivity testing (ERT) did not increase the chances of achieving live birth in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization.

The study was promoted by widespread use of the tests in reproductive medicine and earlier conflicting studies regarding its effectiveness. The procedure, in which doctors extract cells from a woman’s endometrial lining in an effort to determine the best day to perform in vitro fertilization, requires a biopsy, can take a month to generate results, and costs up to $1,000.

But the new study, published online December 6 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that embryo transfer based on the timing of ERT was no better than that based on the standard protocol.

“Endometrial receptivity testing ended up not being beneficial in the population of interest, a good-prognosis IVF patient population,” said Nicole Doyle, MD, PhD, of Shady Grove Fertility, in Arlington, Va., who led the study. “For this particular patient population I would not recommend ERT based on the results of the trial.”

“Unfortunately, as is our history in reproductive medicine, we may embrace technology prematurely given patient desperation and physician eagerness to improve pregnancy outcomes,” said Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center in Orlando, who was not involved in the new research.

The double-blind, randomized clinical trial enrolled 726 women treated at Dr. Doyle’s clinic between May 2018 and September 2020.

All the women underwent ERT. Of those who received adjusted progesterone exposure after the test, live birth occurred in 58.5% of transfers (223 of 381). Among those in a control group who did not have their progesterone adjusted after ERT and underwent IVF on a standardized schedule, 61.9% of transfers (239 of 386) resulted in live birth, according to the researchers.

The differences in rates of clinical (77.2% vs. 79.5% [95% confidence interval, −10.4% to 2.4%]) and biochemical pregnancy (68.8% vs. 72.8% [95% CI, −8.2% to 3.5%]) were not statistically significant between the two groups, Dr. Doyle and her colleagues reported.

Women who experienced recurrent implantation failure (RIF), defined as more than two failed embryo transfers, were excluded from the study. “We can’t assess the benefit of an endometrial receptivity testing in this particular patient population,” Dr. Doyle said.

However, she noted that the number of women who undergo RIF is “a very small fraction of all IVF patients, less than 5%.” Of those, half are expected to have embryos that are not suitable for implantation, Dr. Doyle said.

As a result, she said, “it’s really only about 2.5% of IVF patients for which we don’t yet have an answer regarding the utility of ERT.”

Dr. Trolice, also a professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, expressed certainty that the “one-size-fits-all approach” for ERT has been disproven by the study’s failure to find a benefit from the procedure in women with a “good prognosis.” But, he added, whether ERT is of value in a subset of patients, such as those with recurrent implantation failure, remains “a question of vital importance.”

Dr. Doyle and Dr. Trolice reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

How to advocate in a post-Roe world, no matter your zip code

For many, the recent Supreme Court decision in the Dobbs v Jackson case that removed the constitutional right to an abortion has introduced outrage, fear, and confusion throughout the country. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clearly has established that abortion is essential health care and has published resources regarding the issue (www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential), and many providers know what to do medically, they do not know what they can do legally. In a country where 45% of pregnancies are unplanned and 25% of women will access abortion services in their lifetime, this decision will completely change the landscape of providing and receiving abortion care. This decision will affect every provider and their patients and will affect them differently in each state. The country likely will be divided into 24 destination states that will protect the right to abortion and another 26 states that have or will soon ban abortion or severely restrict access to it.

Regardless of the state you practice in, it is clear that our voices, actions, and advocacy are essential during these challenging times. It can feel difficult to find ways to advocate, especially if you are in a state or have an employer that supports anti-abortion legislation or has been silent after the Dobbs decision was released. We have created a guide to help and encourage all ObGyn providers to find ways to advocate, no matter their zip code.

1. Donate

Many of our patients will need to travel out of state to seek abortion care. The cost of abortion care can be expensive, and travel, child care, and time off of work add to the costs of the procedure itself, making access to abortion care financially out of reach for some. There are many well-established abortion funds throughout the country; consider donating to one of them or organizing a fundraiser in your community. Go to abortionfunds.org/funds to find an abortion fund that will support patients in your community, or donate generally to support them all.

2. Save your stories

We already are hearing the devastating impact abortion bans have on patient care around the country. If you had to deny or delay care because of the new legal landscape surrounding abortion, write down or record the experience. Your stories can be critical in discussing the impact of legislation. If you choose to share on social media, ask the involved patients if they are comfortable with their story being shared online (as long as their identity is protected).

3. Talk about it

Talking about abortion is a critical step in destigmatizing it and supporting our patients as well as our field. These conversations can be challenging, but ACOG has provided an important guide that includes key phrases and statements to help shape the conversation and avoid polarizing language (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/come-prepared). This guide also can be helpful to keep in mind when talking to members of the media.

Continue to: 4. Write about it...

4. Write about it

There are many opportunities to write about the impact of the Dobbs decision, especially locally. As a clinician and trusted member of the community, you can uniquely share your and your patients’ experiences. Your article does not have to appear in a major publication; you can still have an important impact in your local paper. See resources on how to write an op-ed and letter to the editor (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/connect-in-your-community/legislative-rx-op-eds-and-letters-to-the-editor).

5. Teach about it

These legislative changes uniquely impact our ObGyn residents; 44% of residents likely will be in a training program in a state that will ban or severely restrict abortion access. Abortion is health care, and a vast majority of our residents could graduate without important skills to save lives. As we strategize to ensure all ObGyn residents are able to receive this important training, work on incorporating an advocacy curriculum into your residents’ educational experience. Teaching about how to advocate is an important skill for supporting our patients and ensuring critical health policy. ACOG has published guides focused on education and training (www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/education-and-training). We also have included our own medical center’s advocacy curriculum (https://docs.google.com/document/d/1STxLzE0j55mlDEbF0_wZbo9O QryAcs6RpfZ47Mwfs4I/edit).

6. Get involved and seek out allies

It’s important that ObGyns be at the table for all discussions surrounding abortion care and reproductive health. Join hospital committees and help influence policy within your own institution. Refer back to those abortion talking points—this will help in some of these challenging conversations.

7. Get on social media

Using social media can be a powerful tool for advocacy. You can help elevate issues and encourage others to get active as well. Using a common hashtag, such as #AbortionisHealthcare, on different platforms can help connect you to other advocates. Share simple and important graphics provided by ACOG on important topics in our field (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/advocate-in-your-state/social-media) and review ACOG’s recommendation for professionalism in social media (https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/10/professional-use-of-digital-and-social-media).

8. Get active locally

We have seen the introduction of hundreds of bills in states around the country not only on abortion but also on other legislation that directly impacts the care we provide. It is critical that we get involved in advocating for important reproductive health legislation and against bills that cause harm and interfere with the doctor-patient relationship. Stay up to date on legislative issues with your local ACOG and medical chapters (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/advocate-in-your-state). Consider testifying at your State house, providing written or oral testimony. Connect with ACOG or your state medical chapter to help with talking points!

9. Read up

There have been many new policies at the federal level that could impact the care you provide. Take some time to read up on these new changes. Patients also may ask you about self-managed abortion. There are guides and resources (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/practice-management) for patients that may seek medication online, and we want to ensure that patients have the resources to make informed decisions.

10. Hit the Capitol

Consider making time to come to the annual Congressional Leadership Conference in Washington, DC (https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/meetings/acog-congressional-leadership-conference), or other advocacy events offered through the American Medical Association or other subspecialty organizations. When we all come together as an organization, a field, and a community, it sends a powerful message that we are standing up together for our patients and our colleagues.

Make a difference

There is no advocacy too big or too small. It is critical that we continue to use our voices and our platforms to stand up for health care and access to critical services, including abortion care. ●

For many, the recent Supreme Court decision in the Dobbs v Jackson case that removed the constitutional right to an abortion has introduced outrage, fear, and confusion throughout the country. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clearly has established that abortion is essential health care and has published resources regarding the issue (www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential), and many providers know what to do medically, they do not know what they can do legally. In a country where 45% of pregnancies are unplanned and 25% of women will access abortion services in their lifetime, this decision will completely change the landscape of providing and receiving abortion care. This decision will affect every provider and their patients and will affect them differently in each state. The country likely will be divided into 24 destination states that will protect the right to abortion and another 26 states that have or will soon ban abortion or severely restrict access to it.

Regardless of the state you practice in, it is clear that our voices, actions, and advocacy are essential during these challenging times. It can feel difficult to find ways to advocate, especially if you are in a state or have an employer that supports anti-abortion legislation or has been silent after the Dobbs decision was released. We have created a guide to help and encourage all ObGyn providers to find ways to advocate, no matter their zip code.

1. Donate

Many of our patients will need to travel out of state to seek abortion care. The cost of abortion care can be expensive, and travel, child care, and time off of work add to the costs of the procedure itself, making access to abortion care financially out of reach for some. There are many well-established abortion funds throughout the country; consider donating to one of them or organizing a fundraiser in your community. Go to abortionfunds.org/funds to find an abortion fund that will support patients in your community, or donate generally to support them all.

2. Save your stories

We already are hearing the devastating impact abortion bans have on patient care around the country. If you had to deny or delay care because of the new legal landscape surrounding abortion, write down or record the experience. Your stories can be critical in discussing the impact of legislation. If you choose to share on social media, ask the involved patients if they are comfortable with their story being shared online (as long as their identity is protected).

3. Talk about it

Talking about abortion is a critical step in destigmatizing it and supporting our patients as well as our field. These conversations can be challenging, but ACOG has provided an important guide that includes key phrases and statements to help shape the conversation and avoid polarizing language (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/come-prepared). This guide also can be helpful to keep in mind when talking to members of the media.

Continue to: 4. Write about it...

4. Write about it

There are many opportunities to write about the impact of the Dobbs decision, especially locally. As a clinician and trusted member of the community, you can uniquely share your and your patients’ experiences. Your article does not have to appear in a major publication; you can still have an important impact in your local paper. See resources on how to write an op-ed and letter to the editor (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/connect-in-your-community/legislative-rx-op-eds-and-letters-to-the-editor).

5. Teach about it

These legislative changes uniquely impact our ObGyn residents; 44% of residents likely will be in a training program in a state that will ban or severely restrict abortion access. Abortion is health care, and a vast majority of our residents could graduate without important skills to save lives. As we strategize to ensure all ObGyn residents are able to receive this important training, work on incorporating an advocacy curriculum into your residents’ educational experience. Teaching about how to advocate is an important skill for supporting our patients and ensuring critical health policy. ACOG has published guides focused on education and training (www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/education-and-training). We also have included our own medical center’s advocacy curriculum (https://docs.google.com/document/d/1STxLzE0j55mlDEbF0_wZbo9O QryAcs6RpfZ47Mwfs4I/edit).

6. Get involved and seek out allies

It’s important that ObGyns be at the table for all discussions surrounding abortion care and reproductive health. Join hospital committees and help influence policy within your own institution. Refer back to those abortion talking points—this will help in some of these challenging conversations.

7. Get on social media

Using social media can be a powerful tool for advocacy. You can help elevate issues and encourage others to get active as well. Using a common hashtag, such as #AbortionisHealthcare, on different platforms can help connect you to other advocates. Share simple and important graphics provided by ACOG on important topics in our field (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/advocate-in-your-state/social-media) and review ACOG’s recommendation for professionalism in social media (https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/10/professional-use-of-digital-and-social-media).

8. Get active locally

We have seen the introduction of hundreds of bills in states around the country not only on abortion but also on other legislation that directly impacts the care we provide. It is critical that we get involved in advocating for important reproductive health legislation and against bills that cause harm and interfere with the doctor-patient relationship. Stay up to date on legislative issues with your local ACOG and medical chapters (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/advocate-in-your-state). Consider testifying at your State house, providing written or oral testimony. Connect with ACOG or your state medical chapter to help with talking points!

9. Read up

There have been many new policies at the federal level that could impact the care you provide. Take some time to read up on these new changes. Patients also may ask you about self-managed abortion. There are guides and resources (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/practice-management) for patients that may seek medication online, and we want to ensure that patients have the resources to make informed decisions.

10. Hit the Capitol

Consider making time to come to the annual Congressional Leadership Conference in Washington, DC (https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/meetings/acog-congressional-leadership-conference), or other advocacy events offered through the American Medical Association or other subspecialty organizations. When we all come together as an organization, a field, and a community, it sends a powerful message that we are standing up together for our patients and our colleagues.

Make a difference

There is no advocacy too big or too small. It is critical that we continue to use our voices and our platforms to stand up for health care and access to critical services, including abortion care. ●

For many, the recent Supreme Court decision in the Dobbs v Jackson case that removed the constitutional right to an abortion has introduced outrage, fear, and confusion throughout the country. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clearly has established that abortion is essential health care and has published resources regarding the issue (www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential), and many providers know what to do medically, they do not know what they can do legally. In a country where 45% of pregnancies are unplanned and 25% of women will access abortion services in their lifetime, this decision will completely change the landscape of providing and receiving abortion care. This decision will affect every provider and their patients and will affect them differently in each state. The country likely will be divided into 24 destination states that will protect the right to abortion and another 26 states that have or will soon ban abortion or severely restrict access to it.

Regardless of the state you practice in, it is clear that our voices, actions, and advocacy are essential during these challenging times. It can feel difficult to find ways to advocate, especially if you are in a state or have an employer that supports anti-abortion legislation or has been silent after the Dobbs decision was released. We have created a guide to help and encourage all ObGyn providers to find ways to advocate, no matter their zip code.

1. Donate

Many of our patients will need to travel out of state to seek abortion care. The cost of abortion care can be expensive, and travel, child care, and time off of work add to the costs of the procedure itself, making access to abortion care financially out of reach for some. There are many well-established abortion funds throughout the country; consider donating to one of them or organizing a fundraiser in your community. Go to abortionfunds.org/funds to find an abortion fund that will support patients in your community, or donate generally to support them all.

2. Save your stories

We already are hearing the devastating impact abortion bans have on patient care around the country. If you had to deny or delay care because of the new legal landscape surrounding abortion, write down or record the experience. Your stories can be critical in discussing the impact of legislation. If you choose to share on social media, ask the involved patients if they are comfortable with their story being shared online (as long as their identity is protected).

3. Talk about it

Talking about abortion is a critical step in destigmatizing it and supporting our patients as well as our field. These conversations can be challenging, but ACOG has provided an important guide that includes key phrases and statements to help shape the conversation and avoid polarizing language (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/come-prepared). This guide also can be helpful to keep in mind when talking to members of the media.

Continue to: 4. Write about it...

4. Write about it

There are many opportunities to write about the impact of the Dobbs decision, especially locally. As a clinician and trusted member of the community, you can uniquely share your and your patients’ experiences. Your article does not have to appear in a major publication; you can still have an important impact in your local paper. See resources on how to write an op-ed and letter to the editor (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/connect-in-your-community/legislative-rx-op-eds-and-letters-to-the-editor).

5. Teach about it

These legislative changes uniquely impact our ObGyn residents; 44% of residents likely will be in a training program in a state that will ban or severely restrict abortion access. Abortion is health care, and a vast majority of our residents could graduate without important skills to save lives. As we strategize to ensure all ObGyn residents are able to receive this important training, work on incorporating an advocacy curriculum into your residents’ educational experience. Teaching about how to advocate is an important skill for supporting our patients and ensuring critical health policy. ACOG has published guides focused on education and training (www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/education-and-training). We also have included our own medical center’s advocacy curriculum (https://docs.google.com/document/d/1STxLzE0j55mlDEbF0_wZbo9O QryAcs6RpfZ47Mwfs4I/edit).

6. Get involved and seek out allies

It’s important that ObGyns be at the table for all discussions surrounding abortion care and reproductive health. Join hospital committees and help influence policy within your own institution. Refer back to those abortion talking points—this will help in some of these challenging conversations.

7. Get on social media

Using social media can be a powerful tool for advocacy. You can help elevate issues and encourage others to get active as well. Using a common hashtag, such as #AbortionisHealthcare, on different platforms can help connect you to other advocates. Share simple and important graphics provided by ACOG on important topics in our field (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/advocate-in-your-state/social-media) and review ACOG’s recommendation for professionalism in social media (https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/10/professional-use-of-digital-and-social-media).

8. Get active locally

We have seen the introduction of hundreds of bills in states around the country not only on abortion but also on other legislation that directly impacts the care we provide. It is critical that we get involved in advocating for important reproductive health legislation and against bills that cause harm and interfere with the doctor-patient relationship. Stay up to date on legislative issues with your local ACOG and medical chapters (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/advocate-in-your-state). Consider testifying at your State house, providing written or oral testimony. Connect with ACOG or your state medical chapter to help with talking points!

9. Read up

There have been many new policies at the federal level that could impact the care you provide. Take some time to read up on these new changes. Patients also may ask you about self-managed abortion. There are guides and resources (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/practice-management) for patients that may seek medication online, and we want to ensure that patients have the resources to make informed decisions.

10. Hit the Capitol

Consider making time to come to the annual Congressional Leadership Conference in Washington, DC (https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/meetings/acog-congressional-leadership-conference), or other advocacy events offered through the American Medical Association or other subspecialty organizations. When we all come together as an organization, a field, and a community, it sends a powerful message that we are standing up together for our patients and our colleagues.

Make a difference

There is no advocacy too big or too small. It is critical that we continue to use our voices and our platforms to stand up for health care and access to critical services, including abortion care. ●

Simplify your approach to the diagnosis and treatment of PCOS

PCOS is a common problem, with a prevalence of 6% to 10% among women of reproductive age.1 Patients with PCOS often present with hirsutism, acne, female androgenetic alopecia, oligomenorrhea (also known as infrequent menstrual bleeding), amenorrhea, infertility, overweight, or obesity. In addition, many patients with PCOS have insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and an increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM).2 A simplified approach to the diagnosis of PCOS will save health care resources by reducing the use of low-value diagnostic tests. A simplified approach to the treatment of PCOS will support patient medication adherence and improve health outcomes.

Simplify the diagnosis of PCOS

Simplify PCOS diagnosis by focusing on the core criteria of hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation. There are 3 major approaches to diagnosis:

- the 1990 National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria3

- the 2003 Rotterdam criteria4,5

- the 2008 Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES) criteria.6

Using the 1990 NIH approach, the diagnosis of PCOS is made by the presence of 2 core criteria: hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation, typically manifested as oligomenorrhea. In addition, other causes of hyperandrogenism should be excluded, including nonclassical adrenal hyperplasia (NCAH) due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency.3 Using the 1990 NIH criteria, PCOS can be diagnosed based on history (oligomenorrhea) and physical examination (assessment of the severity of hirsutism), but laboratory tests including total testosterone are often ordered.7

The Rotterdam approach to the diagnosis added a third criteria, the detection by ultrasonography of a multifollicular ovary and/or increased ovarian volume.4,5 Using the Rotterdam approach, PCOS is diagnosed in the presence of any 2 of the following 3 criteria: hyperandrogenism, oligo-ovulation, or ultrasound imaging showing the presence of a multifollicular ovary, identified by ≥ 12 antral follicles (2 to 9 mm in diameter) in each ovary or increased ovarian volume (> 10 mL).4,5

The Rotterdam approach using ovarian ultrasound as a criterion to diagnose PCOS is rife with serious problems, including:

- The number of small antral follicles in the normal ovary is age dependent, and many ovulatory and nonhirsute patients have ≥ 12 small antral follicles in each ovary.8,9

- There is no consensus on the number of small antral follicles needed to diagnose a multifollicular ovary, with recommendations to use thresholds of 124,5 or 20 follicles10 as the diagnostic cut-off.

- Accurate counting of the number of small ovarian follicles requires transvaginal ultrasound, which is not appropriate for many young adolescent patients.

- The process of counting ovarian follicles is operator-dependent.

- The high cost of ultrasound assessment of ovarian follicles (≥ $500 per examination).

The Rotterdam approach supports the diagnosis of PCOS in a patient with oligo-ovulation plus an ultrasound showing a multifollicular ovary in the absence of any clinical or laboratory evidence of hyperandrogenism.3,4,5 This approach to the diagnosis of PCOS is rejected by both the 1990 NIH3 and AES6 recommendations, which require the presence of hyperandrogenism as the sine qua non in the diagnosis of PCOS. I recommend against diagnosing PCOS in a non-hyperandrogenic patient with oligo-ovulation and a multifollicular ovary because other diagnoses are also possible, such as functional hypothalamic oligo-ovulation, especially in young patients. The Rotterdam approach also supports the diagnosis of PCOS in a patient with hyperandrogenism, an ultrasound showing a multifollicular ovary, and normal ovulation and menses.3,4 For most patients with normal, regular ovulation and menses, the testosterone concentration is normal and the only evidence of hyperandrogenism is hirsutism. Patients with normal, regular ovulation and menses plus hirsutism usually have idiopathic hirsutism. Idiopathic hirsutism is a problem caused by excessive 5-alpha-reductase activity in the hair pilosebaceous unit, which catalyzes the conversion of weak androgens into dihydrotestosterone, a potent intracellular androgen that stimulates terminal hair growth.11 In my opinion, the Rotterdam approach to diagnosing PCOS has created unnecessary confusion and complexity for both clinicians and patients. I believe we should simplify the diagnosis of PCOS and return to the 1990 NIH criteria.3

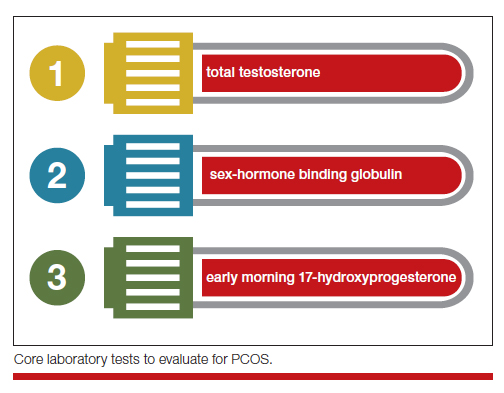

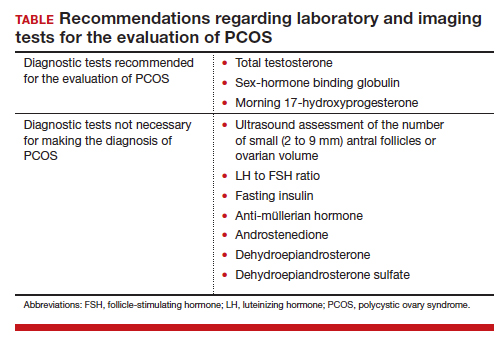

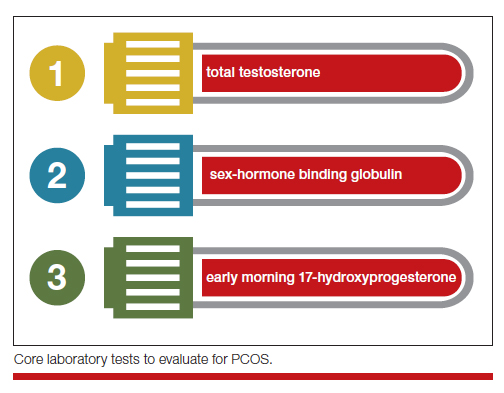

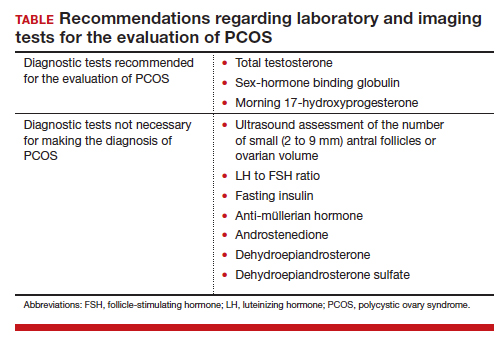

On occasion, a patient presents for a consultation and has already had an ovarian ultrasound to assess for a multifollicular ovary. I carefully read the report and, if a multifollicular ovary has been identified, I consider it as a secondary supporting finding of PCOS in my clinical assessment. But I do not base my diagnosis on the ultrasound finding. Patients often present with other laboratory tests that are secondary supporting findings of PCOS, which I carefully consider but do not use to make a diagnosis of PCOS. Secondary supporting laboratory findings consistent with PCOS include: 1) a markedly elevated anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) level,12 2) an elevated fasting insulin level,2,13 and 3) an elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio.13,14 But it is not necessary to measure AMH, fasting insulin, LH, and FSH levels. To conserve health care resources, I recommend against measuring those analytes to diagnose PCOS.

Continue to: Simplify the core laboratory tests...

Simplify the core laboratory tests

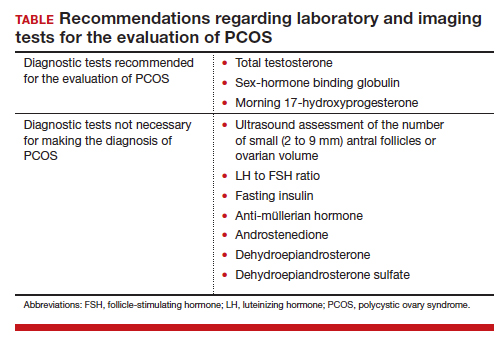

Simplify the testing used to support the diagnosis of PCOS by measuring total testosterone, sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and early morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OH Prog).

The core criteria for diagnosis of PCOS are hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation, typically manifested as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea. Hyperandrogenism can be clinically diagnosed by assessing for the presence of hirsutism.7 Elevated levels of total testosterone, free testosterone, androstenedione, and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) suggest the presence of hyperandrogenism. In clinical practice, the laboratory approach to the diagnosis of hyperandrogenism can be simplified to the measurement of total testosterone, SHBG, and 17-OH Prog. By measuring total testosterone and SHBG, an estimate of free testosterone can be made. If the total testosterone is elevated, it is highly likely that the free testosterone is elevated. If the SHBG is abnormally low and the total testosterone level is in the upper limit of the normal range, the free testosterone is likely to be elevated.15 Using this approach, either an elevated total testosterone or an abnormally low SHBG indicate elevated free testosterone. For patients with hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation, an early morning (8 to 9 AM) 17-OH Prog level ≤ 2 ng/mL rules out the presence of NCAH due to a 21-hydroxylase deficiency.16 In my practice, the core laboratory tests I order when considering the diagnosis of PCOS are a total testosterone, SHBG, and 17-OH Prog.

Additional laboratory tests may be warranted to assess the patient diagnosed with PCOS. For example, if the patient has amenorrhea due to anovulation, tests for prolactin, FSH, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are warranted to assess for the presence of a prolactinoma, primary ovarian insufficiency, or thyroid disease, respectively. If the patient has a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2, a hemoglobin A1c concentration is warranted to assess for the presence of prediabetes or DM.2 Many patients with PCOS have dyslipidemia, manifested through low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and a lipid panel assessment may be indicated. Among patients with PCOS, the most common lipid abnormality is a low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level.17

Simplify the treatment of PCOS

Simplify treatment by counseling about lifestyle changes and prescribing an estrogen-progestin contraceptive, spironolactone, and metformin.

Most patients with PCOS have dysfunction in reproductive, metabolic, and dermatologic systems. For patients who are overweight or obese, lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, that result in a 5% to 10% decrease in weight can improve metabolic balance, reduce circulating androgens, and increase menstrual frequency.18 For patients with PCOS and weight issues, referral to nutrition counseling or a full-service weight loss program can be very beneficial. In addition to lifestyle changes, patients with PCOS benefit from treatment with estrogen-progestin medications, spironolactone, and metformin.

Combination estrogen-progestin medications will lower LH secretion, decrease ovarian androgen production, increase SHBG production, decrease free testosterone levels and, if given cyclically, cause regular withdrawal bleeding.19 Spironolactone is an antiandrogen, which blocks the intracellular action of dihydrotestosterone and improves hirsutism and acne. Spironolactone also modestly decreases circulating levels of testosterone and DHEAS.20 For patients with metabolic problems, including insulin resistance and obesity, weight loss and/or treatment with metformin can help improve metabolic balance, which may result in restoration of ovulatory menses.21,22 Metformin can be effective in restoring ovulatory menses in both obese and lean patients with PCOS.22 The most common dermatologic problem caused by PCOS are hirsutism and acne. Both combination estrogen-progestin medications and spironolactone are effective treatments for hirsutism and acne.23

Estrogen-progestin hormones, spironolactone, and metformin are low-cost medications for the treatment of PCOS. Additional high-cost options for treatment of PCOS in obese patients include bariatric surgery and glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonist medications (liraglutide and exenatide). For patients with PCOS and a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2, bariatric surgery often results in sufficient weight loss to resolve the patient’s hyperandrogenism and oligo-ovulation, restoring spontaneous ovulatory cycles.24 In a study of more than 1,000 patients with: PCOS; mean BMI, 44 kg/m2; mean age, 31 years who were followed post-bariatric surgery for 5 years, > 90% of patients reported reductions in hirsutism and resumption of regular menses.25 For patients with PCOS seeking fertility, bariatric surgery often results in spontaneous pregnancy and live birth.26 GLP-1 agonists, including liraglutide or exenatide with or without metformin are effective in reducing weight, decreasing androgen levels, and restoring ovulatory menses.27,28

In my practice, I often prescribe 2 or 3 core medications for a patient with PCOS: 1) combination estrogen-progestin used cyclically or continuously, 2) spironolactone, and 3) metformin.19 Any estrogen-progestin contraceptive will suppress LH and ovarian androgen production; however, in the treatment of patients with PCOS, I prefer to use an estrogen-progestin combination that does not contain the androgenic progestin levonorgestrel.29 For the treatment of PCOS, I prefer to use an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with a non-androgenic progestin such as drospirenone, desogestrel, or gestodene. I routinely prescribe spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg, once daily, a dose near the top of the dose-response curve. A daily dose ≤ 50 mg of spironolactone is subtherapeutic for the treatment of hirsutism. A daily dose of 200 mg of spironolactone may cause bothersome breakthrough bleeding. When prescribing metformin, I usually recommend the extended-release formulation, at a dose of 750 mg with dinner. If well tolerated, I will increase the dose to 1,500 mg with dinner. Most of my patients with PCOS are taking a combination of 2 medications, either an estrogen-progestin contraceptive plus spironolactone or an estrogen-progestin contraceptive plus metformin.19 Some of my patients are taking all 3 medications. All 3 medications are very low cost.

For patients with PCOS and anovulatory infertility, letrozole treatment often results in ovulatory cycles and pregnancy with live birth. In obese PCOS patients, compared with clomiphene, letrozole results in superior live birth rates.30 Unlike clomiphene, letrozole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of anovulatory infertility.