User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Canadian guidance recommends reducing alcohol consumption

“Drinking less is better,” says the guidance, which replaces Canada’s 2011 Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs).

Developed in consultation with an executive committee from federal, provincial, and territorial governments; national organizations; three scientific expert panels; and an internal evidence review working group, the guidance presents the following findings:

- Consuming no drinks per week has benefits, such as better health and better sleep, and it’s the only safe option during pregnancy.

- Consuming one or two standard drinks weekly will likely not have alcohol-related consequences.

- Three to six drinks raise the risk of developing breast, colon, and other cancers.

- Seven or more increase the risk of heart disease or stroke.

- Each additional drink “radically increases” the risk of these health consequences.

“Alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought and is a key component of the health of your patients,” Adam Sherk, PhD, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria (B.C.), and a member of the scientific expert panel that contributed to the guidance, said in an interview. “Display and discuss the new guidance with your patients with the main message that drinking less is better.”

Peter Butt, MD, a clinical associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, and cochair of the guidance project, said in an interview: “The World Health Organization has identified over 200 ICD-coded conditions associated with alcohol use. This creates many opportunities to inquire into quantity and frequency of alcohol use, relate it to the patient’s health and well-being, and provide advice on reduction.”

“Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” and a related infographic were published online Jan. 17.

Continuum of risk

The impetus for the new guidance came from the fact that “our 2011 LRDGs were no longer current, and there was emerging evidence that people drinking within those levels were coming to harm,” said Dr. Butt.

That evidence indicates that alcohol causes at least seven types of cancer, mostly of the breast or colon; is a risk factor for most types of heart disease; and is a main cause of liver disease. Evidence also indicates that avoiding drinking to the point of intoxication will reduce people’s risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Responding to the need to accurately quantify the risk, the guidance defines a “standard” drink as 12 oz of beer, cooler, or cider (5% alcohol); 5 oz of wine (12% alcohol); and 1.5 oz of spirits such as whiskey, vodka, or gin (40% alcohol).

Using different mortality risk thresholds, the project’s experts developed the following continuum of risk:

- Low for individuals who consume two standard drinks or fewer per week

- Moderate for those who consume from three to six standard drinks per week

- Increasingly high for those who consume seven standard drinks or more per week

The guidance makes the following observations:

- Consuming more than two standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

- When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, no amount of alcohol is safe.

- When breastfeeding, not drinking is safest.

- Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone, health risks increase more steeply for females than males.

- Far more injuries, violence, and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially for per occasion drinking, than from women’s alcohol use.

- Young people should delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

- Individuals should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits.

- Any reduction in alcohol use is beneficial.

Other national guidelines

“Countries that haven’t updated their alcohol use guidelines recently should do so, as the evidence regarding alcohol and health has advanced considerably in the past 10 years,” said Dr. Sherk. He acknowledged that “any time health guidance changes substantially, it’s reasonable to expect a period of readjustment.”

“Some will be resistant,” Dr. Butt agreed. “Some professionals will need more education than others on the health effects of alcohol. Some patients will also be more invested in drinking than others. The harm-reduction, risk-zone approach should assist in the process of engaging patients and helping them reduce over time.

“Just as we benefited from the updates done in the United Kingdom, France, and especially Australia, so also researchers elsewhere will critique our work and our approach and make their own decisions on how best to communicate with their public,” Dr. Butt said. He noted that Canada’s contributions regarding the association between alcohol and violence, as well as their sex/gender approach to the evidence, “may influence the next country’s review.”

Commenting on whether the United States should consider changing its guidance, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services for the Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview, “A lot of people will be surprised at the recommended limits on alcohol. Most think that they can have one or two glasses of alcohol per day and not have any increased risk to their health. I think the Canadians deserve credit for putting themselves out there.”

Dr. Brennan said there will “certainly be pushback by the drinking lobby, which is very strong both in the U.S. and in Canada.” In fact, the national trade group Beer Canada was recently quoted as stating that it still supports the 2011 guidelines and that the updating process lacked full transparency and expert technical peer review.

Nevertheless, Dr. Brennan said, “it’s overwhelmingly clear that alcohol affects a ton of different parts of our body, so limiting the amount of alcohol we take in is always going to be a good thing. The Canadian graphic is great because it color-codes the risk. I recommend that clinicians put it up in their offices and begin quantifying the units of alcohol that are going into a patient’s body each day.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“Drinking less is better,” says the guidance, which replaces Canada’s 2011 Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs).

Developed in consultation with an executive committee from federal, provincial, and territorial governments; national organizations; three scientific expert panels; and an internal evidence review working group, the guidance presents the following findings:

- Consuming no drinks per week has benefits, such as better health and better sleep, and it’s the only safe option during pregnancy.

- Consuming one or two standard drinks weekly will likely not have alcohol-related consequences.

- Three to six drinks raise the risk of developing breast, colon, and other cancers.

- Seven or more increase the risk of heart disease or stroke.

- Each additional drink “radically increases” the risk of these health consequences.

“Alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought and is a key component of the health of your patients,” Adam Sherk, PhD, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria (B.C.), and a member of the scientific expert panel that contributed to the guidance, said in an interview. “Display and discuss the new guidance with your patients with the main message that drinking less is better.”

Peter Butt, MD, a clinical associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, and cochair of the guidance project, said in an interview: “The World Health Organization has identified over 200 ICD-coded conditions associated with alcohol use. This creates many opportunities to inquire into quantity and frequency of alcohol use, relate it to the patient’s health and well-being, and provide advice on reduction.”

“Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” and a related infographic were published online Jan. 17.

Continuum of risk

The impetus for the new guidance came from the fact that “our 2011 LRDGs were no longer current, and there was emerging evidence that people drinking within those levels were coming to harm,” said Dr. Butt.

That evidence indicates that alcohol causes at least seven types of cancer, mostly of the breast or colon; is a risk factor for most types of heart disease; and is a main cause of liver disease. Evidence also indicates that avoiding drinking to the point of intoxication will reduce people’s risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Responding to the need to accurately quantify the risk, the guidance defines a “standard” drink as 12 oz of beer, cooler, or cider (5% alcohol); 5 oz of wine (12% alcohol); and 1.5 oz of spirits such as whiskey, vodka, or gin (40% alcohol).

Using different mortality risk thresholds, the project’s experts developed the following continuum of risk:

- Low for individuals who consume two standard drinks or fewer per week

- Moderate for those who consume from three to six standard drinks per week

- Increasingly high for those who consume seven standard drinks or more per week

The guidance makes the following observations:

- Consuming more than two standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

- When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, no amount of alcohol is safe.

- When breastfeeding, not drinking is safest.

- Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone, health risks increase more steeply for females than males.

- Far more injuries, violence, and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially for per occasion drinking, than from women’s alcohol use.

- Young people should delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

- Individuals should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits.

- Any reduction in alcohol use is beneficial.

Other national guidelines

“Countries that haven’t updated their alcohol use guidelines recently should do so, as the evidence regarding alcohol and health has advanced considerably in the past 10 years,” said Dr. Sherk. He acknowledged that “any time health guidance changes substantially, it’s reasonable to expect a period of readjustment.”

“Some will be resistant,” Dr. Butt agreed. “Some professionals will need more education than others on the health effects of alcohol. Some patients will also be more invested in drinking than others. The harm-reduction, risk-zone approach should assist in the process of engaging patients and helping them reduce over time.

“Just as we benefited from the updates done in the United Kingdom, France, and especially Australia, so also researchers elsewhere will critique our work and our approach and make their own decisions on how best to communicate with their public,” Dr. Butt said. He noted that Canada’s contributions regarding the association between alcohol and violence, as well as their sex/gender approach to the evidence, “may influence the next country’s review.”

Commenting on whether the United States should consider changing its guidance, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services for the Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview, “A lot of people will be surprised at the recommended limits on alcohol. Most think that they can have one or two glasses of alcohol per day and not have any increased risk to their health. I think the Canadians deserve credit for putting themselves out there.”

Dr. Brennan said there will “certainly be pushback by the drinking lobby, which is very strong both in the U.S. and in Canada.” In fact, the national trade group Beer Canada was recently quoted as stating that it still supports the 2011 guidelines and that the updating process lacked full transparency and expert technical peer review.

Nevertheless, Dr. Brennan said, “it’s overwhelmingly clear that alcohol affects a ton of different parts of our body, so limiting the amount of alcohol we take in is always going to be a good thing. The Canadian graphic is great because it color-codes the risk. I recommend that clinicians put it up in their offices and begin quantifying the units of alcohol that are going into a patient’s body each day.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“Drinking less is better,” says the guidance, which replaces Canada’s 2011 Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs).

Developed in consultation with an executive committee from federal, provincial, and territorial governments; national organizations; three scientific expert panels; and an internal evidence review working group, the guidance presents the following findings:

- Consuming no drinks per week has benefits, such as better health and better sleep, and it’s the only safe option during pregnancy.

- Consuming one or two standard drinks weekly will likely not have alcohol-related consequences.

- Three to six drinks raise the risk of developing breast, colon, and other cancers.

- Seven or more increase the risk of heart disease or stroke.

- Each additional drink “radically increases” the risk of these health consequences.

“Alcohol is more harmful than was previously thought and is a key component of the health of your patients,” Adam Sherk, PhD, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research at the University of Victoria (B.C.), and a member of the scientific expert panel that contributed to the guidance, said in an interview. “Display and discuss the new guidance with your patients with the main message that drinking less is better.”

Peter Butt, MD, a clinical associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, and cochair of the guidance project, said in an interview: “The World Health Organization has identified over 200 ICD-coded conditions associated with alcohol use. This creates many opportunities to inquire into quantity and frequency of alcohol use, relate it to the patient’s health and well-being, and provide advice on reduction.”

“Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report” and a related infographic were published online Jan. 17.

Continuum of risk

The impetus for the new guidance came from the fact that “our 2011 LRDGs were no longer current, and there was emerging evidence that people drinking within those levels were coming to harm,” said Dr. Butt.

That evidence indicates that alcohol causes at least seven types of cancer, mostly of the breast or colon; is a risk factor for most types of heart disease; and is a main cause of liver disease. Evidence also indicates that avoiding drinking to the point of intoxication will reduce people’s risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Responding to the need to accurately quantify the risk, the guidance defines a “standard” drink as 12 oz of beer, cooler, or cider (5% alcohol); 5 oz of wine (12% alcohol); and 1.5 oz of spirits such as whiskey, vodka, or gin (40% alcohol).

Using different mortality risk thresholds, the project’s experts developed the following continuum of risk:

- Low for individuals who consume two standard drinks or fewer per week

- Moderate for those who consume from three to six standard drinks per week

- Increasingly high for those who consume seven standard drinks or more per week

The guidance makes the following observations:

- Consuming more than two standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

- When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, no amount of alcohol is safe.

- When breastfeeding, not drinking is safest.

- Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone, health risks increase more steeply for females than males.

- Far more injuries, violence, and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially for per occasion drinking, than from women’s alcohol use.

- Young people should delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

- Individuals should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits.

- Any reduction in alcohol use is beneficial.

Other national guidelines

“Countries that haven’t updated their alcohol use guidelines recently should do so, as the evidence regarding alcohol and health has advanced considerably in the past 10 years,” said Dr. Sherk. He acknowledged that “any time health guidance changes substantially, it’s reasonable to expect a period of readjustment.”

“Some will be resistant,” Dr. Butt agreed. “Some professionals will need more education than others on the health effects of alcohol. Some patients will also be more invested in drinking than others. The harm-reduction, risk-zone approach should assist in the process of engaging patients and helping them reduce over time.

“Just as we benefited from the updates done in the United Kingdom, France, and especially Australia, so also researchers elsewhere will critique our work and our approach and make their own decisions on how best to communicate with their public,” Dr. Butt said. He noted that Canada’s contributions regarding the association between alcohol and violence, as well as their sex/gender approach to the evidence, “may influence the next country’s review.”

Commenting on whether the United States should consider changing its guidance, Timothy Brennan, MD, MPH, chief of clinical services for the Addiction Institute of Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview, “A lot of people will be surprised at the recommended limits on alcohol. Most think that they can have one or two glasses of alcohol per day and not have any increased risk to their health. I think the Canadians deserve credit for putting themselves out there.”

Dr. Brennan said there will “certainly be pushback by the drinking lobby, which is very strong both in the U.S. and in Canada.” In fact, the national trade group Beer Canada was recently quoted as stating that it still supports the 2011 guidelines and that the updating process lacked full transparency and expert technical peer review.

Nevertheless, Dr. Brennan said, “it’s overwhelmingly clear that alcohol affects a ton of different parts of our body, so limiting the amount of alcohol we take in is always going to be a good thing. The Canadian graphic is great because it color-codes the risk. I recommend that clinicians put it up in their offices and begin quantifying the units of alcohol that are going into a patient’s body each day.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender people in rural America struggle to find doctors willing or able to provide care

For Tammy Rainey, finding a health care provider who knows about gender-affirming care has been a challenge in the rural northern Mississippi town where she lives.

As a transgender woman, Ms. Rainey needs the hormone estrogen, which allows her to physically transition by developing more feminine features. But when she asked her doctor for an estrogen prescription, he said he couldn’t provide that type of care.

“He’s generally a good guy and doesn’t act prejudiced. He gets my name and pronouns right,” said Ms. Rainey. “But when I asked him about hormones, he said, ‘I just don’t feel like I know enough about that. I don’t want to get involved in that.’ ”

So Ms. Rainey drives around 170 miles round trip every 6 months to get a supply of estrogen from a clinic in Memphis, Tenn., to take home with her.

The obstacles Ms. Rainey overcomes to access care illustrate a type of medical inequity that transgender people who live in the rural United States often face: A general lack of education about trans-related care among small-town health professionals who might also be reluctant to learn.

“Medical communities across the country are seeing clearly that there is a knowledge gap in the provision of gender-affirming care,” said Morissa Ladinsky, MD, a pediatrician who co-leads the Youth Multidisciplinary Gender Team at the University of Alabama–Birmingham (UAB).

Accurately counting the number of transgender people in rural America is hindered by a lack of U.S. census data and uniform state data. However, the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates for LGBTQ+ issues, used 2014-17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from selected ZIP codes in 35 states to estimate that roughly one in six transgender adults in the United States live in a rural area. When that report was released in 2019, there were an estimated 1.4 million transgender people 13 and older nationwide. That number is now at least 1.6 million, according to the Williams Institute, a nonprofit think tank at the UCLA School of Law.

One in three trans people in rural areas experienced discrimination by a health care provider in the year leading up to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey Report, according to an analysis by MAP. A third of all trans individuals report having to teach their doctors about their health care needs to receive appropriate care, and 62% worry about being negatively judged by a health care provider because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to data collected by the Williams Institute and other organizations.

A lack of local rural providers knowledgeable in trans care can mean long drives to gender-affirming clinics in metropolitan areas. Rural trans people are three times as likely as are all transgender adults to travel 25-49 miles for routine care.

In Colorado, for example, many trans people outside Denver struggle to find proper care. Those who do have a trans-inclusive provider are more likely to receive wellness exams, less likely to delay care due to discrimination, and less likely to attempt suicide, according to results from the Colorado Transgender Health Survey published in 2018.

Much of the lack of care experienced by trans people is linked to insufficient education on LGBTQ+ health in medical schools across the country. In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents 170 accredited medical schools in the United States and Canada, released its first curriculum guidelines on caring for LGBTQ+ patients. As of 2018, 76% of medical schools included LGBTQ health themes in their curriculum, with half providing three or fewer classes on this topic.

Perhaps because of this, almost 77% of students from 10 medical schools in New England felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” in treating gender minority patients, according to a 2018 pilot study. Another paper, published last year, found that even clinicians who work in trans-friendly clinics lack knowledge about hormones, gender-affirming surgical options, and how to use appropriate pronouns and trans-inclusive language.

Throughout medical school, trans care was only briefly mentioned in endocrinology class, said Justin Bailey, MD, who received his medical degree from UAB in 2021 and is now a resident there. “I don’t want to say the wrong thing or use the wrong pronouns, so I was hesitant and a little bit tepid in my approach to interviewing and treating this population of patients,” he said.

On top of insufficient medical school education, some practicing doctors don’t take the time to teach themselves about trans people, said Kathie Moehlig, founder of TransFamily Support Services, a nonprofit organization that offers a range of services to transgender people and their families. They are very well intentioned yet uneducated when it comes to transgender care, she said.

Some medical schools, like the one at UAB, have pushed for change. Since 2017, Dr. Ladinsky and her colleagues have worked to include trans people in their standardized patient program, which gives medical students hands-on experience and feedback by interacting with “patients” in simulated clinical environments.

For example, a trans individual acting as a patient will simulate acid reflux by pretending to have pain in their stomach and chest. Then, over the course of the examination, they will reveal that they are transgender.

In the early years of this program, some students’ bedside manner would change once the patient’s gender identity was revealed, said Elaine Stephens, a trans woman who participates in UAB’s standardized patient program. “Sometimes they would immediately start asking about sexual activity,” Stephens said.

Since UAB launched its program, students’ reactions have improved significantly, she said.

This progress is being replicated by other medical schools, said Ms. Moehlig. “But it’s a slow start, and these are large institutions that take a long time to move forward.”

Advocates also are working outside medical schools to improve care in rural areas. In Colorado, the nonprofit Extension for Community Health Outcomes, or ECHO Colorado, has been offering monthly virtual classes on gender-affirming care to rural providers since 2020. The classes became so popular that the organization created a 4-week boot camp in 2021 for providers to learn about hormone therapy management, proper terminologies, surgical options, and supporting patients’ mental health.

For many years, doctors failed to recognize the need to learn about gender-affirming care, said Caroline Kirsch, DO, director of osteopathic education at the University of Wyoming Family Medicine Residency Program–Casper. In Casper, this led to “a number of patients traveling to Colorado to access care, which is a large burden for them financially,” said Dr. Kirsch, who has participated in the ECHO Colorado program.

“Things that haven’t been as well taught historically in medical school are things that I think many physicians feel anxious about initially,” she said. “The earlier you learn about this type of care in your career, the more likely you are to see its potential and be less anxious about it.”

Educating more providers about trans-related care has become increasingly vital in recent years as gender-affirming clinics nationwide experience a rise in harassment and threats. For instance, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Clinic for Transgender Health became the target of far-right hate on social media last year. After growing pressure from Tennessee’s Republican lawmakers, the clinic paused gender-affirmation surgeries on patients younger than 18, potentially leaving many trans individuals without necessary care.

Stephens hopes to see more medical schools include coursework on trans health care. She also wishes for doctors to treat trans people as they would any other patient.

“Just provide quality health care,” she tells the medical students at UAB. “We need health care like everyone else does.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

For Tammy Rainey, finding a health care provider who knows about gender-affirming care has been a challenge in the rural northern Mississippi town where she lives.

As a transgender woman, Ms. Rainey needs the hormone estrogen, which allows her to physically transition by developing more feminine features. But when she asked her doctor for an estrogen prescription, he said he couldn’t provide that type of care.

“He’s generally a good guy and doesn’t act prejudiced. He gets my name and pronouns right,” said Ms. Rainey. “But when I asked him about hormones, he said, ‘I just don’t feel like I know enough about that. I don’t want to get involved in that.’ ”

So Ms. Rainey drives around 170 miles round trip every 6 months to get a supply of estrogen from a clinic in Memphis, Tenn., to take home with her.

The obstacles Ms. Rainey overcomes to access care illustrate a type of medical inequity that transgender people who live in the rural United States often face: A general lack of education about trans-related care among small-town health professionals who might also be reluctant to learn.

“Medical communities across the country are seeing clearly that there is a knowledge gap in the provision of gender-affirming care,” said Morissa Ladinsky, MD, a pediatrician who co-leads the Youth Multidisciplinary Gender Team at the University of Alabama–Birmingham (UAB).

Accurately counting the number of transgender people in rural America is hindered by a lack of U.S. census data and uniform state data. However, the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates for LGBTQ+ issues, used 2014-17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from selected ZIP codes in 35 states to estimate that roughly one in six transgender adults in the United States live in a rural area. When that report was released in 2019, there were an estimated 1.4 million transgender people 13 and older nationwide. That number is now at least 1.6 million, according to the Williams Institute, a nonprofit think tank at the UCLA School of Law.

One in three trans people in rural areas experienced discrimination by a health care provider in the year leading up to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey Report, according to an analysis by MAP. A third of all trans individuals report having to teach their doctors about their health care needs to receive appropriate care, and 62% worry about being negatively judged by a health care provider because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to data collected by the Williams Institute and other organizations.

A lack of local rural providers knowledgeable in trans care can mean long drives to gender-affirming clinics in metropolitan areas. Rural trans people are three times as likely as are all transgender adults to travel 25-49 miles for routine care.

In Colorado, for example, many trans people outside Denver struggle to find proper care. Those who do have a trans-inclusive provider are more likely to receive wellness exams, less likely to delay care due to discrimination, and less likely to attempt suicide, according to results from the Colorado Transgender Health Survey published in 2018.

Much of the lack of care experienced by trans people is linked to insufficient education on LGBTQ+ health in medical schools across the country. In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents 170 accredited medical schools in the United States and Canada, released its first curriculum guidelines on caring for LGBTQ+ patients. As of 2018, 76% of medical schools included LGBTQ health themes in their curriculum, with half providing three or fewer classes on this topic.

Perhaps because of this, almost 77% of students from 10 medical schools in New England felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” in treating gender minority patients, according to a 2018 pilot study. Another paper, published last year, found that even clinicians who work in trans-friendly clinics lack knowledge about hormones, gender-affirming surgical options, and how to use appropriate pronouns and trans-inclusive language.

Throughout medical school, trans care was only briefly mentioned in endocrinology class, said Justin Bailey, MD, who received his medical degree from UAB in 2021 and is now a resident there. “I don’t want to say the wrong thing or use the wrong pronouns, so I was hesitant and a little bit tepid in my approach to interviewing and treating this population of patients,” he said.

On top of insufficient medical school education, some practicing doctors don’t take the time to teach themselves about trans people, said Kathie Moehlig, founder of TransFamily Support Services, a nonprofit organization that offers a range of services to transgender people and their families. They are very well intentioned yet uneducated when it comes to transgender care, she said.

Some medical schools, like the one at UAB, have pushed for change. Since 2017, Dr. Ladinsky and her colleagues have worked to include trans people in their standardized patient program, which gives medical students hands-on experience and feedback by interacting with “patients” in simulated clinical environments.

For example, a trans individual acting as a patient will simulate acid reflux by pretending to have pain in their stomach and chest. Then, over the course of the examination, they will reveal that they are transgender.

In the early years of this program, some students’ bedside manner would change once the patient’s gender identity was revealed, said Elaine Stephens, a trans woman who participates in UAB’s standardized patient program. “Sometimes they would immediately start asking about sexual activity,” Stephens said.

Since UAB launched its program, students’ reactions have improved significantly, she said.

This progress is being replicated by other medical schools, said Ms. Moehlig. “But it’s a slow start, and these are large institutions that take a long time to move forward.”

Advocates also are working outside medical schools to improve care in rural areas. In Colorado, the nonprofit Extension for Community Health Outcomes, or ECHO Colorado, has been offering monthly virtual classes on gender-affirming care to rural providers since 2020. The classes became so popular that the organization created a 4-week boot camp in 2021 for providers to learn about hormone therapy management, proper terminologies, surgical options, and supporting patients’ mental health.

For many years, doctors failed to recognize the need to learn about gender-affirming care, said Caroline Kirsch, DO, director of osteopathic education at the University of Wyoming Family Medicine Residency Program–Casper. In Casper, this led to “a number of patients traveling to Colorado to access care, which is a large burden for them financially,” said Dr. Kirsch, who has participated in the ECHO Colorado program.

“Things that haven’t been as well taught historically in medical school are things that I think many physicians feel anxious about initially,” she said. “The earlier you learn about this type of care in your career, the more likely you are to see its potential and be less anxious about it.”

Educating more providers about trans-related care has become increasingly vital in recent years as gender-affirming clinics nationwide experience a rise in harassment and threats. For instance, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Clinic for Transgender Health became the target of far-right hate on social media last year. After growing pressure from Tennessee’s Republican lawmakers, the clinic paused gender-affirmation surgeries on patients younger than 18, potentially leaving many trans individuals without necessary care.

Stephens hopes to see more medical schools include coursework on trans health care. She also wishes for doctors to treat trans people as they would any other patient.

“Just provide quality health care,” she tells the medical students at UAB. “We need health care like everyone else does.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

For Tammy Rainey, finding a health care provider who knows about gender-affirming care has been a challenge in the rural northern Mississippi town where she lives.

As a transgender woman, Ms. Rainey needs the hormone estrogen, which allows her to physically transition by developing more feminine features. But when she asked her doctor for an estrogen prescription, he said he couldn’t provide that type of care.

“He’s generally a good guy and doesn’t act prejudiced. He gets my name and pronouns right,” said Ms. Rainey. “But when I asked him about hormones, he said, ‘I just don’t feel like I know enough about that. I don’t want to get involved in that.’ ”

So Ms. Rainey drives around 170 miles round trip every 6 months to get a supply of estrogen from a clinic in Memphis, Tenn., to take home with her.

The obstacles Ms. Rainey overcomes to access care illustrate a type of medical inequity that transgender people who live in the rural United States often face: A general lack of education about trans-related care among small-town health professionals who might also be reluctant to learn.

“Medical communities across the country are seeing clearly that there is a knowledge gap in the provision of gender-affirming care,” said Morissa Ladinsky, MD, a pediatrician who co-leads the Youth Multidisciplinary Gender Team at the University of Alabama–Birmingham (UAB).

Accurately counting the number of transgender people in rural America is hindered by a lack of U.S. census data and uniform state data. However, the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates for LGBTQ+ issues, used 2014-17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from selected ZIP codes in 35 states to estimate that roughly one in six transgender adults in the United States live in a rural area. When that report was released in 2019, there were an estimated 1.4 million transgender people 13 and older nationwide. That number is now at least 1.6 million, according to the Williams Institute, a nonprofit think tank at the UCLA School of Law.

One in three trans people in rural areas experienced discrimination by a health care provider in the year leading up to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey Report, according to an analysis by MAP. A third of all trans individuals report having to teach their doctors about their health care needs to receive appropriate care, and 62% worry about being negatively judged by a health care provider because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to data collected by the Williams Institute and other organizations.

A lack of local rural providers knowledgeable in trans care can mean long drives to gender-affirming clinics in metropolitan areas. Rural trans people are three times as likely as are all transgender adults to travel 25-49 miles for routine care.

In Colorado, for example, many trans people outside Denver struggle to find proper care. Those who do have a trans-inclusive provider are more likely to receive wellness exams, less likely to delay care due to discrimination, and less likely to attempt suicide, according to results from the Colorado Transgender Health Survey published in 2018.

Much of the lack of care experienced by trans people is linked to insufficient education on LGBTQ+ health in medical schools across the country. In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents 170 accredited medical schools in the United States and Canada, released its first curriculum guidelines on caring for LGBTQ+ patients. As of 2018, 76% of medical schools included LGBTQ health themes in their curriculum, with half providing three or fewer classes on this topic.

Perhaps because of this, almost 77% of students from 10 medical schools in New England felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” in treating gender minority patients, according to a 2018 pilot study. Another paper, published last year, found that even clinicians who work in trans-friendly clinics lack knowledge about hormones, gender-affirming surgical options, and how to use appropriate pronouns and trans-inclusive language.

Throughout medical school, trans care was only briefly mentioned in endocrinology class, said Justin Bailey, MD, who received his medical degree from UAB in 2021 and is now a resident there. “I don’t want to say the wrong thing or use the wrong pronouns, so I was hesitant and a little bit tepid in my approach to interviewing and treating this population of patients,” he said.

On top of insufficient medical school education, some practicing doctors don’t take the time to teach themselves about trans people, said Kathie Moehlig, founder of TransFamily Support Services, a nonprofit organization that offers a range of services to transgender people and their families. They are very well intentioned yet uneducated when it comes to transgender care, she said.

Some medical schools, like the one at UAB, have pushed for change. Since 2017, Dr. Ladinsky and her colleagues have worked to include trans people in their standardized patient program, which gives medical students hands-on experience and feedback by interacting with “patients” in simulated clinical environments.

For example, a trans individual acting as a patient will simulate acid reflux by pretending to have pain in their stomach and chest. Then, over the course of the examination, they will reveal that they are transgender.

In the early years of this program, some students’ bedside manner would change once the patient’s gender identity was revealed, said Elaine Stephens, a trans woman who participates in UAB’s standardized patient program. “Sometimes they would immediately start asking about sexual activity,” Stephens said.

Since UAB launched its program, students’ reactions have improved significantly, she said.

This progress is being replicated by other medical schools, said Ms. Moehlig. “But it’s a slow start, and these are large institutions that take a long time to move forward.”

Advocates also are working outside medical schools to improve care in rural areas. In Colorado, the nonprofit Extension for Community Health Outcomes, or ECHO Colorado, has been offering monthly virtual classes on gender-affirming care to rural providers since 2020. The classes became so popular that the organization created a 4-week boot camp in 2021 for providers to learn about hormone therapy management, proper terminologies, surgical options, and supporting patients’ mental health.

For many years, doctors failed to recognize the need to learn about gender-affirming care, said Caroline Kirsch, DO, director of osteopathic education at the University of Wyoming Family Medicine Residency Program–Casper. In Casper, this led to “a number of patients traveling to Colorado to access care, which is a large burden for them financially,” said Dr. Kirsch, who has participated in the ECHO Colorado program.

“Things that haven’t been as well taught historically in medical school are things that I think many physicians feel anxious about initially,” she said. “The earlier you learn about this type of care in your career, the more likely you are to see its potential and be less anxious about it.”

Educating more providers about trans-related care has become increasingly vital in recent years as gender-affirming clinics nationwide experience a rise in harassment and threats. For instance, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Clinic for Transgender Health became the target of far-right hate on social media last year. After growing pressure from Tennessee’s Republican lawmakers, the clinic paused gender-affirmation surgeries on patients younger than 18, potentially leaving many trans individuals without necessary care.

Stephens hopes to see more medical schools include coursework on trans health care. She also wishes for doctors to treat trans people as they would any other patient.

“Just provide quality health care,” she tells the medical students at UAB. “We need health care like everyone else does.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Ospemifene and HT boost vaginal microbiome in vulvovaginal atrophy

The selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene appears to improve the vaginal microbiome of postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), according to results from a small Italian case-control study in the journal Menopause.

The study sheds microbiological light on the mechanisms of ospemifene and low-dose systemic hormone therapy, which are widely used to treat genitourinary symptoms. Both had a positive effect on vaginal well-being, likely by reducing potentially harmful bacteria and increasing health-promoting acid-friendly microorganisms, writes a group led by M. Cristina Meriggiola, MD, PhD, of the gynecology and physiopathology of human reproduction unit at the University of Bologna, Italy.

VVA occurs in about 50% of postmenopausal women and produces a less favorable, less acidic vaginal microbiome profile than that of unaffected women. “The loss of estrogen leads to lower concentrations of Lactobacilli, bacteria that lower the pH. As a result, other bacterial species fill in the void,” explained Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health in Jacksonville, Fla., and medical director of the North American Menopause Society.

Added Tina Murphy, APN, a NAMS-certified menopause practitioner at Northwestern Medicine Orland Park in Illinois, “When this protective flora declines, then pathogenic bacteria can predominate the microbiome, which can contribute to vaginal irritation, infection, UTI’s, dyspareunia, and discomfort. Balancing and restoring the microbiome can mitigate the effects of estrogen depletion on the vaginal tissue and prevent the untoward effects of the hypoestrogenic state.” While ospemifene and hormone therapy are common therapies for the genitourinary symptoms of menopause, the focus has been on their treatment efficacy, not their effect on the microbiome profile, added Dr. Faubion. Only about 9% of women with menopause-related genitourinary symptoms receive prescription treatment, she added.

The study

Of 67 eligible postmenopausal participants in their mid-50s enrolled at a gynecology clinic from April 2019 to February 2020, 39 were diagnosed with VVA and 28 were considered healthy controls. In the atrophic group, 20 were prescribed ospemifene and 19 received hormone treatment.

Only those women with VVA but no menopausal vasomotor symptoms received ospemifene (60 mg/day); symptomatic women received hormone therapy according to guidelines.

The researchers calculated the women’s vaginal health index (VHI) based on elasticity, secretions, pH level, epithelial mucosa, and hydration. They used swabs to assess vaginal maturation index (VMI) by percentages of superficial, intermediate, and parabasal cells. Evaluation of the vaginal microbiome was done with 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and clinical and microbiological analyses were repeated after 3 months.

The vaginal microbiome of atrophic women was characterized by a significant reduction of benign Lactobacillus bacteria (P = .002) and an increase of potentially pathogenic Streptococcus (P = .008) and Sneathia (P = .02) bacteria.

The vaginal microbiome of women with VVA was depleted, within the Lactobacillus genus, in the L. crispatus species, a hallmark of vaginal health that has significant antimicrobial activity against endogenous and exogenous pathogens.

Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between the VHI/VMI and Lactobacillus abundance (P = .002 and P = 0.035, respectively).

While the lactic acid–producing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera were strongly associated with healthy controls, the characteristics of VVA patients were strongly associated with Streptococcus, Prevotella, Alloscardovia, and Staphylococcus.

Both therapeutic approaches effectively improved vaginal indices but by different routes. Systemic hormone treatment induced changes in minority bacterial groups in the vaginal microbiome, whereas ospemifene eliminated specific harmful bacterial taxa, such as Staphylococcus (P = .04) and Clostridium (P = .01). Both treatments induced a trend in the increase of beneficial Bifidobacteria.

A 2022 study reported that vaginal estradiol tablets significantly changed the vaginal microbiota in postmenopausal women compared with vaginal moisturizer or placebo, but the reductions in bothersome symptoms were similar.

The future

“Areas for future study include the assessment of changes in the vaginal microbiome, proteomic profiles, and immunologic markers with various treatments and the associations between these changes and genitourinary symptoms,” Dr. Faubion said. She added that, while there may be a role at some point for oral or topical probiotics, “Thus far, probiotics have not demonstrated significant benefits.”

Meanwhile, said Ms. Murphy, “There are many options available that may benefit our patients. As a provider, meeting with your patient, discussing her concerns and individual risk factors is the most important part of choosing the correct treatment plan.”

The authors call for further studies to confirm the observed modifications of the vaginal ecosystem. In the meantime, Dr. Meriggiola said in an interview, “My best advice to physicians is to ask women if they have this problem. Do not ignore it; be proactive and treat. There are many options on the market for genitourinary symptoms – not just for postmenopausal women but breast cancer survivors as well.”

Dr. Meriggiola’s group is planning to study ospemifene in cancer patients, whose quality of life is severely affected by VVA.

This study received no financial support. Dr. Meriggiola reported past financial relationships with Shionogi Limited, Teramex, Organon, Italfarmaco, MDS Italia, and Bayer. Coauthor Dr. Baldassarre disclosed past financial relationships with Shionogi. Ms. Murphy disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest with respect to her comments. Dr. Faubion is medical director of the North American Menopause Society and editor of the journal Menopause.

The selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene appears to improve the vaginal microbiome of postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), according to results from a small Italian case-control study in the journal Menopause.

The study sheds microbiological light on the mechanisms of ospemifene and low-dose systemic hormone therapy, which are widely used to treat genitourinary symptoms. Both had a positive effect on vaginal well-being, likely by reducing potentially harmful bacteria and increasing health-promoting acid-friendly microorganisms, writes a group led by M. Cristina Meriggiola, MD, PhD, of the gynecology and physiopathology of human reproduction unit at the University of Bologna, Italy.

VVA occurs in about 50% of postmenopausal women and produces a less favorable, less acidic vaginal microbiome profile than that of unaffected women. “The loss of estrogen leads to lower concentrations of Lactobacilli, bacteria that lower the pH. As a result, other bacterial species fill in the void,” explained Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health in Jacksonville, Fla., and medical director of the North American Menopause Society.

Added Tina Murphy, APN, a NAMS-certified menopause practitioner at Northwestern Medicine Orland Park in Illinois, “When this protective flora declines, then pathogenic bacteria can predominate the microbiome, which can contribute to vaginal irritation, infection, UTI’s, dyspareunia, and discomfort. Balancing and restoring the microbiome can mitigate the effects of estrogen depletion on the vaginal tissue and prevent the untoward effects of the hypoestrogenic state.” While ospemifene and hormone therapy are common therapies for the genitourinary symptoms of menopause, the focus has been on their treatment efficacy, not their effect on the microbiome profile, added Dr. Faubion. Only about 9% of women with menopause-related genitourinary symptoms receive prescription treatment, she added.

The study

Of 67 eligible postmenopausal participants in their mid-50s enrolled at a gynecology clinic from April 2019 to February 2020, 39 were diagnosed with VVA and 28 were considered healthy controls. In the atrophic group, 20 were prescribed ospemifene and 19 received hormone treatment.

Only those women with VVA but no menopausal vasomotor symptoms received ospemifene (60 mg/day); symptomatic women received hormone therapy according to guidelines.

The researchers calculated the women’s vaginal health index (VHI) based on elasticity, secretions, pH level, epithelial mucosa, and hydration. They used swabs to assess vaginal maturation index (VMI) by percentages of superficial, intermediate, and parabasal cells. Evaluation of the vaginal microbiome was done with 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and clinical and microbiological analyses were repeated after 3 months.

The vaginal microbiome of atrophic women was characterized by a significant reduction of benign Lactobacillus bacteria (P = .002) and an increase of potentially pathogenic Streptococcus (P = .008) and Sneathia (P = .02) bacteria.

The vaginal microbiome of women with VVA was depleted, within the Lactobacillus genus, in the L. crispatus species, a hallmark of vaginal health that has significant antimicrobial activity against endogenous and exogenous pathogens.

Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between the VHI/VMI and Lactobacillus abundance (P = .002 and P = 0.035, respectively).

While the lactic acid–producing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera were strongly associated with healthy controls, the characteristics of VVA patients were strongly associated with Streptococcus, Prevotella, Alloscardovia, and Staphylococcus.

Both therapeutic approaches effectively improved vaginal indices but by different routes. Systemic hormone treatment induced changes in minority bacterial groups in the vaginal microbiome, whereas ospemifene eliminated specific harmful bacterial taxa, such as Staphylococcus (P = .04) and Clostridium (P = .01). Both treatments induced a trend in the increase of beneficial Bifidobacteria.

A 2022 study reported that vaginal estradiol tablets significantly changed the vaginal microbiota in postmenopausal women compared with vaginal moisturizer or placebo, but the reductions in bothersome symptoms were similar.

The future

“Areas for future study include the assessment of changes in the vaginal microbiome, proteomic profiles, and immunologic markers with various treatments and the associations between these changes and genitourinary symptoms,” Dr. Faubion said. She added that, while there may be a role at some point for oral or topical probiotics, “Thus far, probiotics have not demonstrated significant benefits.”

Meanwhile, said Ms. Murphy, “There are many options available that may benefit our patients. As a provider, meeting with your patient, discussing her concerns and individual risk factors is the most important part of choosing the correct treatment plan.”

The authors call for further studies to confirm the observed modifications of the vaginal ecosystem. In the meantime, Dr. Meriggiola said in an interview, “My best advice to physicians is to ask women if they have this problem. Do not ignore it; be proactive and treat. There are many options on the market for genitourinary symptoms – not just for postmenopausal women but breast cancer survivors as well.”

Dr. Meriggiola’s group is planning to study ospemifene in cancer patients, whose quality of life is severely affected by VVA.

This study received no financial support. Dr. Meriggiola reported past financial relationships with Shionogi Limited, Teramex, Organon, Italfarmaco, MDS Italia, and Bayer. Coauthor Dr. Baldassarre disclosed past financial relationships with Shionogi. Ms. Murphy disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest with respect to her comments. Dr. Faubion is medical director of the North American Menopause Society and editor of the journal Menopause.

The selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene appears to improve the vaginal microbiome of postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), according to results from a small Italian case-control study in the journal Menopause.

The study sheds microbiological light on the mechanisms of ospemifene and low-dose systemic hormone therapy, which are widely used to treat genitourinary symptoms. Both had a positive effect on vaginal well-being, likely by reducing potentially harmful bacteria and increasing health-promoting acid-friendly microorganisms, writes a group led by M. Cristina Meriggiola, MD, PhD, of the gynecology and physiopathology of human reproduction unit at the University of Bologna, Italy.

VVA occurs in about 50% of postmenopausal women and produces a less favorable, less acidic vaginal microbiome profile than that of unaffected women. “The loss of estrogen leads to lower concentrations of Lactobacilli, bacteria that lower the pH. As a result, other bacterial species fill in the void,” explained Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health in Jacksonville, Fla., and medical director of the North American Menopause Society.

Added Tina Murphy, APN, a NAMS-certified menopause practitioner at Northwestern Medicine Orland Park in Illinois, “When this protective flora declines, then pathogenic bacteria can predominate the microbiome, which can contribute to vaginal irritation, infection, UTI’s, dyspareunia, and discomfort. Balancing and restoring the microbiome can mitigate the effects of estrogen depletion on the vaginal tissue and prevent the untoward effects of the hypoestrogenic state.” While ospemifene and hormone therapy are common therapies for the genitourinary symptoms of menopause, the focus has been on their treatment efficacy, not their effect on the microbiome profile, added Dr. Faubion. Only about 9% of women with menopause-related genitourinary symptoms receive prescription treatment, she added.

The study

Of 67 eligible postmenopausal participants in their mid-50s enrolled at a gynecology clinic from April 2019 to February 2020, 39 were diagnosed with VVA and 28 were considered healthy controls. In the atrophic group, 20 were prescribed ospemifene and 19 received hormone treatment.

Only those women with VVA but no menopausal vasomotor symptoms received ospemifene (60 mg/day); symptomatic women received hormone therapy according to guidelines.

The researchers calculated the women’s vaginal health index (VHI) based on elasticity, secretions, pH level, epithelial mucosa, and hydration. They used swabs to assess vaginal maturation index (VMI) by percentages of superficial, intermediate, and parabasal cells. Evaluation of the vaginal microbiome was done with 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and clinical and microbiological analyses were repeated after 3 months.

The vaginal microbiome of atrophic women was characterized by a significant reduction of benign Lactobacillus bacteria (P = .002) and an increase of potentially pathogenic Streptococcus (P = .008) and Sneathia (P = .02) bacteria.

The vaginal microbiome of women with VVA was depleted, within the Lactobacillus genus, in the L. crispatus species, a hallmark of vaginal health that has significant antimicrobial activity against endogenous and exogenous pathogens.

Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between the VHI/VMI and Lactobacillus abundance (P = .002 and P = 0.035, respectively).

While the lactic acid–producing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera were strongly associated with healthy controls, the characteristics of VVA patients were strongly associated with Streptococcus, Prevotella, Alloscardovia, and Staphylococcus.

Both therapeutic approaches effectively improved vaginal indices but by different routes. Systemic hormone treatment induced changes in minority bacterial groups in the vaginal microbiome, whereas ospemifene eliminated specific harmful bacterial taxa, such as Staphylococcus (P = .04) and Clostridium (P = .01). Both treatments induced a trend in the increase of beneficial Bifidobacteria.

A 2022 study reported that vaginal estradiol tablets significantly changed the vaginal microbiota in postmenopausal women compared with vaginal moisturizer or placebo, but the reductions in bothersome symptoms were similar.

The future

“Areas for future study include the assessment of changes in the vaginal microbiome, proteomic profiles, and immunologic markers with various treatments and the associations between these changes and genitourinary symptoms,” Dr. Faubion said. She added that, while there may be a role at some point for oral or topical probiotics, “Thus far, probiotics have not demonstrated significant benefits.”

Meanwhile, said Ms. Murphy, “There are many options available that may benefit our patients. As a provider, meeting with your patient, discussing her concerns and individual risk factors is the most important part of choosing the correct treatment plan.”

The authors call for further studies to confirm the observed modifications of the vaginal ecosystem. In the meantime, Dr. Meriggiola said in an interview, “My best advice to physicians is to ask women if they have this problem. Do not ignore it; be proactive and treat. There are many options on the market for genitourinary symptoms – not just for postmenopausal women but breast cancer survivors as well.”

Dr. Meriggiola’s group is planning to study ospemifene in cancer patients, whose quality of life is severely affected by VVA.

This study received no financial support. Dr. Meriggiola reported past financial relationships with Shionogi Limited, Teramex, Organon, Italfarmaco, MDS Italia, and Bayer. Coauthor Dr. Baldassarre disclosed past financial relationships with Shionogi. Ms. Murphy disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest with respect to her comments. Dr. Faubion is medical director of the North American Menopause Society and editor of the journal Menopause.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Update on secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer

Recurrent ovarian cancer is difficult to treat; it has high recurrence rates and poor targeted treatment options. Between 60% and 75% of patients initially diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer will relapse within 2-3 years.1 Survival for these patients is poor, with an average overall survival (OS) of 30-40 months from the time of recurrence.2 Historically, immunotherapy has shown poor efficacy for recurrent ovarian malignancy, leaving few options for patients and their providers. Given the lack of effective treatment options, secondary cytoreductive surgery (surgery at the time of recurrence) has been heavily studied as a potential therapeutic option.

The initial rationale for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer focused on palliation of symptoms from large, bulky disease that frequently caused obstructive symptoms and pain. Now, cytoreduction is a critical part of therapy. It decreases chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells, improves the immune response, and is thought to optimize perfusion of the residual cancer for systemic therapy. The survival benefit of surgery in the frontline setting, either with primary or interval debulking, is well established, and much of the data now demonstrate that complete resection of all macroscopic disease (also known as an R0 resection) has the greatest survival benefit.3 Given the benefits of an initial debulking surgery, secondary cytoreduction has been studied since the 1980s with mixed results. These data have demonstrated that the largest barrier to care has been appropriate patient selection for this often complex surgical procedure.

The 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines list secondary CRS as a treatment option; however, the procedure should only be considered in patients who have platinum sensitive disease, a performance status of 0-1, no ascites, and an isolated focus or limited focus of disease that is amenable to complete resection. Numerous retrospective studies have suggested that secondary CRS is beneficial to patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, especially if complete cytoreduction can be accomplished. Many of these studies have similarly concluded that there are benefits, such as less ascites at the time of recurrence, smaller disease burden, and a longer disease-free interval. From that foundation, multiple groups used retrospective data to investigate prognostic models to determine who would benefit most from secondary cytoreduction.

The DESKTOP Group initially published their retrospective study in 2006 and created a scoring system assessing who would benefit from secondary CRS.4 Data demonstrated that a performance status of 0, FIGO stage of I/II at the time of initial diagnosis, no residual tumor after primary surgery, and ascites less than 500 mL were associated with improved survival after secondary cytoreduction. They created the AGO score out of these data, which is positive only if three criteria are met: a performance status of 0, R0 after primary debulk, and ascites less than 500 mL at the time of recurrence.

They prospectively tested this score in DESKTOP II, which validated their findings and showed that complete secondary CRS could be achieved in 76% of those with a positive AGO score.5 Many believed that the AGO score was too restrictive, and a second retrospective study performed by a group at Memorial Sloan Kettering showed that optimal secondary cytoreduction could be achieved to prolong survival by a median of 30 months in patients with a longer disease-free interval, a single site of recurrence, and residual disease measuring less than 5 mm at time of initial/first-line surgery.6 Many individuals now use this scoring system to determine candidacy for secondary debulking: disease-free interval, number of sites of recurrence (ideally oligometastatic disease), and residual disease less than 5 mm at the time of primary debulking.

Finally, the iMODEL was developed by a group from China and found that complete R0 secondary CRS was associated with a low initial FIGO stage, no residual disease after primary surgery, longer platinum-free interval, better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, lower CA-125 levels, as well as no ascites at the time of recurrence. Based on these criteria, individuals received either high or low iMODEL scores, and those with a low score were said to be candidates for secondary CRS. Overall, these models demonstrate that the strongest predictive factor that suggests a survival benefit from secondary CRS is the ability to achieve a complete R0 resection at the time of surgery.

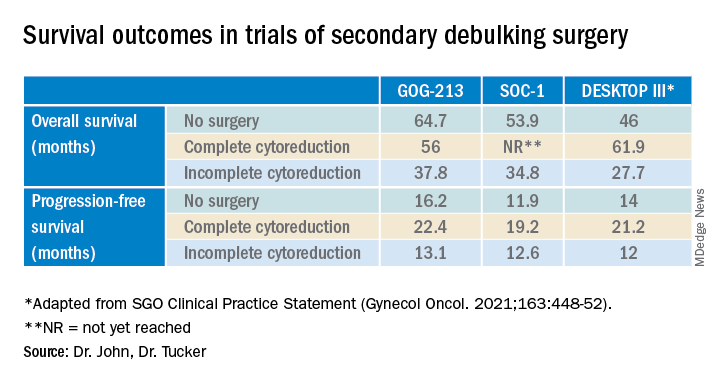

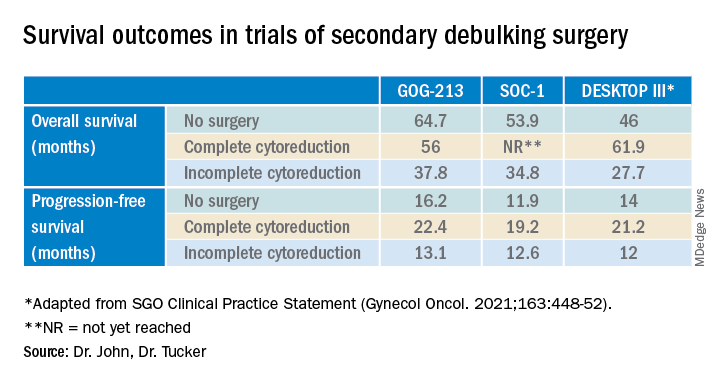

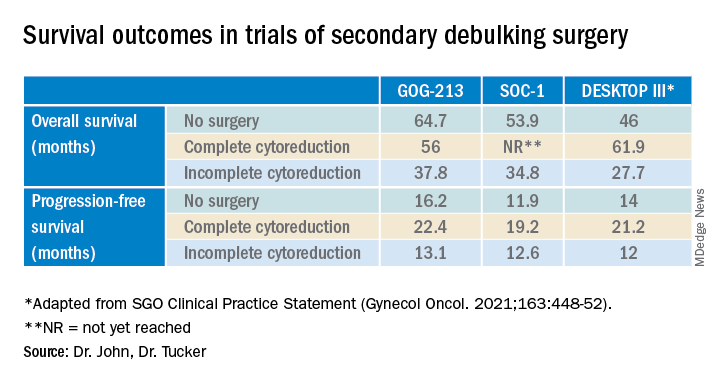

Secondary debulking surgery has been tested in three large randomized controlled trials. The DESKTOP investigators and the SOC-1 trial have been the most successful groups to publish on this topic with positive results. Both groups use prognostic models for their inclusion criteria to select candidates in whom an R0 resection is believed to be most feasible. The first randomized controlled trial to publish on this topic was GOG-213,7 which did not use prognostic modeling for their inclusion criteria. Patients were randomized to secondary cytoreduction followed by platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab versus chemotherapy alone. The median OS was 50.6 months in the surgery group and 64.7 months in the no-surgery group (P = .08), suggesting no survival benefit to secondary cytoreduction; however, an ad hoc exploratory analysis of the surgery arm showed that both overall and progression-free survival were significantly improved in the complete cytoreduction group, compared with those with residual disease at time of surgery.

The results from the GOG-213 group suggested that improved survival from secondary debulking might be achieved when prognostic modeling is used to select optimal surgical candidates. The SOC-1 trial, published in 2021, was a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial that used the iMODEL scoring system combined with PET/CT imaging for patient selection.8 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Complete cytoreduction was achieved in 73% of patients with a low iMODEL score, and these data showed improved OS in the surgery group of 58.1 months versus 53.9 months (P < .05) in the no-surgery group. Lastly, the DESKTOP group most recently published results on this topic in a large randomized, controlled trial.9 Patients were again randomized to surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Inclusion criteria were only met in patients with a positive AGO score. An improved OS of 7.7 months (53.7 vs. 46 months; P < .05) was demonstrated in patients that underwent surgery versus those exposed to only chemotherapy. Again, this group showed that overall survival was further improved when complete cytoreduction was achieved.

Given the results of these three trials, the Society for Gynecologic Oncology has released a statement on secondary cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer (see Table).10 While it is important to use caution when comparing the three studies as study populations differed substantially, the most important takeaway the difference in survival outcomes in patients in whom complete gross resection was achieved versus no complete gross resection versus no surgery. This comparison highlights the benefit of complete cytoreduction as well as the potential harms of secondary debulking when an R0 resection cannot be achieved. Although not yet evaluated in this clinical setting, laparoscopic exploration may be useful to augment assessment of disease extent and possibility of disease resection, just as it is in frontline ovarian cancer surgery.

The importance of bevacizumab use in recurrent ovarian cancer is also highlighted in the SGO statement. In GOG-213, 84% of the total study population (in both the surgery and no surgery cohort) were treated with concurrent followed by maintenance bevacizumab with an improved survival outcome, which may suggest that this trial generalizes better than the others to contemporary management of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer.

Overall, given the mixed data, the recommendation is for surgeons to consider all available data to guide them in treatment planning with a strong emphasis on using all available technology to assess whether complete cytoreduction can be achieved in the setting of recurrence so as to not delay the patient’s ability to receive chemotherapy.

Dr. John is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

1. du Bois A et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1320-9.

2. Wagner U et al. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:588-91.

3. Vergote I et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-53.

4. Harter P et al. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702-10.

5. Harter P et al. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:289-95.

6. Chi DS et al. Cancer. 2006 106:1933-9.

7. Coleman RL et al. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:779-1.

8. Shi T et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:439-49.

9. Harter P et al. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2123-31.

10. Harrison R, et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:448-52.

Recurrent ovarian cancer is difficult to treat; it has high recurrence rates and poor targeted treatment options. Between 60% and 75% of patients initially diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer will relapse within 2-3 years.1 Survival for these patients is poor, with an average overall survival (OS) of 30-40 months from the time of recurrence.2 Historically, immunotherapy has shown poor efficacy for recurrent ovarian malignancy, leaving few options for patients and their providers. Given the lack of effective treatment options, secondary cytoreductive surgery (surgery at the time of recurrence) has been heavily studied as a potential therapeutic option.

The initial rationale for cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in patients with advanced ovarian cancer focused on palliation of symptoms from large, bulky disease that frequently caused obstructive symptoms and pain. Now, cytoreduction is a critical part of therapy. It decreases chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells, improves the immune response, and is thought to optimize perfusion of the residual cancer for systemic therapy. The survival benefit of surgery in the frontline setting, either with primary or interval debulking, is well established, and much of the data now demonstrate that complete resection of all macroscopic disease (also known as an R0 resection) has the greatest survival benefit.3 Given the benefits of an initial debulking surgery, secondary cytoreduction has been studied since the 1980s with mixed results. These data have demonstrated that the largest barrier to care has been appropriate patient selection for this often complex surgical procedure.

The 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines list secondary CRS as a treatment option; however, the procedure should only be considered in patients who have platinum sensitive disease, a performance status of 0-1, no ascites, and an isolated focus or limited focus of disease that is amenable to complete resection. Numerous retrospective studies have suggested that secondary CRS is beneficial to patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, especially if complete cytoreduction can be accomplished. Many of these studies have similarly concluded that there are benefits, such as less ascites at the time of recurrence, smaller disease burden, and a longer disease-free interval. From that foundation, multiple groups used retrospective data to investigate prognostic models to determine who would benefit most from secondary cytoreduction.

The DESKTOP Group initially published their retrospective study in 2006 and created a scoring system assessing who would benefit from secondary CRS.4 Data demonstrated that a performance status of 0, FIGO stage of I/II at the time of initial diagnosis, no residual tumor after primary surgery, and ascites less than 500 mL were associated with improved survival after secondary cytoreduction. They created the AGO score out of these data, which is positive only if three criteria are met: a performance status of 0, R0 after primary debulk, and ascites less than 500 mL at the time of recurrence.

They prospectively tested this score in DESKTOP II, which validated their findings and showed that complete secondary CRS could be achieved in 76% of those with a positive AGO score.5 Many believed that the AGO score was too restrictive, and a second retrospective study performed by a group at Memorial Sloan Kettering showed that optimal secondary cytoreduction could be achieved to prolong survival by a median of 30 months in patients with a longer disease-free interval, a single site of recurrence, and residual disease measuring less than 5 mm at time of initial/first-line surgery.6 Many individuals now use this scoring system to determine candidacy for secondary debulking: disease-free interval, number of sites of recurrence (ideally oligometastatic disease), and residual disease less than 5 mm at the time of primary debulking.

Finally, the iMODEL was developed by a group from China and found that complete R0 secondary CRS was associated with a low initial FIGO stage, no residual disease after primary surgery, longer platinum-free interval, better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, lower CA-125 levels, as well as no ascites at the time of recurrence. Based on these criteria, individuals received either high or low iMODEL scores, and those with a low score were said to be candidates for secondary CRS. Overall, these models demonstrate that the strongest predictive factor that suggests a survival benefit from secondary CRS is the ability to achieve a complete R0 resection at the time of surgery.

Secondary debulking surgery has been tested in three large randomized controlled trials. The DESKTOP investigators and the SOC-1 trial have been the most successful groups to publish on this topic with positive results. Both groups use prognostic models for their inclusion criteria to select candidates in whom an R0 resection is believed to be most feasible. The first randomized controlled trial to publish on this topic was GOG-213,7 which did not use prognostic modeling for their inclusion criteria. Patients were randomized to secondary cytoreduction followed by platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab versus chemotherapy alone. The median OS was 50.6 months in the surgery group and 64.7 months in the no-surgery group (P = .08), suggesting no survival benefit to secondary cytoreduction; however, an ad hoc exploratory analysis of the surgery arm showed that both overall and progression-free survival were significantly improved in the complete cytoreduction group, compared with those with residual disease at time of surgery.