User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Infant and maternal weight gain together amplify obesity risk

Rapid weight gain (RWG) in infants and the mother’s prepregnancy overweight have a synergistic effect in increasing the odds that a child will develop overweight or obesity, new research suggests.

Findings were published online in Pediatrics.

Each factor has independently been associated with higher risk of childhood obesity but whether the two factors together exacerbate the risk has not been well studied, according to the authors led by Stephanie Gilley, MD, PhD, department of pediatrics, section of nutrition, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“Pediatric providers should monitor infants for RWG, especially in the context of maternal obesity, to reduce future risk of obesity,” the authors conclude.

Dr. Gilley’s team studied mother-infant dyads (n = 414) from the Healthy Start Study, an observational prebirth cohort. RWG was defined as a weight-for-age z score increase of at least 0.67 from birth to 3-7 months.

They found that RWG boosted the link between prepregnancy body mass index (ppBMI) and BMI z score, especially in female infants. Females exposed to both maternal obesity with RWG had an average BMI at the 94th percentile (1.50 increase in childhood BMI z score) “nearly at the cutoff for classification of obesity,” compared with those exposed to normal ppBMI with no RWG, who had an average childhood BMI at the 51st percentile.

“Currently, our nutrition recommendations as pediatricians are that all children are fed the same, essentially, after they’re born. We don’t have different growth parameters or different trajectories or targets for children who may have had different in utero exposures,” Dr. Gilley said.

Do some children need more monitoring for RWG?

Though we can’t necessarily draw conclusions from this one study, she says, the findings raise the question of whether children who were exposed in utero to obesity should be monitored for RWG more closely.

Lydia Shook, MD, Mass General Brigham maternal-fetal specialist and codirector of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said she was struck by the finding in this study that with female infants, but not males, RWG significantly modified the association between ppBMI and early childhood BMI z scores.

“It’s an interesting finding and should be followed up with larger cohorts,” she said, noting that some previous studies have shown males are more vulnerable to maternal obesity and RWG.

“[Often] when we stratify by sex, you really need larger groups to be able to see the differences well,” Dr. Shook said.

She said she also found it interesting that when the researchers adjusted for breastfeeding status or caloric intake in childhood, the findings did not substantially change.

“That’s something that would warrant further investigation in an observational study or controlled trial,” Dr. Shook said.

Preventing rapid weight gain

The authors note that they did not consider possible interventions for preventing RGW in the study, although there are many, Dr. Gilley said.

Dr. Gilley also noted that a limitation of this study is that the population studied was primarily White.

Recent studies have shown the benefits of responsive parenting (RP) interventions, including a large study in 2022 geared toward Black families to teach better infant sleep practices as a way to prevent rapid weight gain.

That study, which tested the SAAF intervention, (Strong African American Families) found that “RP infants were nearly half as likely to experience upward crossing of two major weight-for-age percentile lines (14.1%), compared with control infants (24.2%); P = .09; odds ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.24-1.12.”

Along with sleep interventions, Dr. Gilley said, some researchers are studying the effects on RWG of better paternal engagement, or more involvement with the Women, Infants, and Children program, particularly with lower-income families.

Other studies have looked at breastfeeding vs. formula feeding – “but there have been mixed results there” – and responsive feeding practices, such as teaching families to recognize when a baby is full.

Dr. Gilley said she hopes this work will help broaden the thinking when it comes to infant weight gain.

“We spend a lot of time thinking about babies who are not growing fast enough and very little time thinking about babies who are growing too fast,” she said, “especially in those first 4-6 months of life.”

Dr. Gilley points to a study that illustrates that point. Pesch et al. concluded in a 2021 study based on interviews that pediatricians “are uncertain about the concept, definition, management, and long-term risks of rapid infant weight gain.”

Authors and Dr. Gilley declare no relevant financial relationships.

Rapid weight gain (RWG) in infants and the mother’s prepregnancy overweight have a synergistic effect in increasing the odds that a child will develop overweight or obesity, new research suggests.

Findings were published online in Pediatrics.

Each factor has independently been associated with higher risk of childhood obesity but whether the two factors together exacerbate the risk has not been well studied, according to the authors led by Stephanie Gilley, MD, PhD, department of pediatrics, section of nutrition, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“Pediatric providers should monitor infants for RWG, especially in the context of maternal obesity, to reduce future risk of obesity,” the authors conclude.

Dr. Gilley’s team studied mother-infant dyads (n = 414) from the Healthy Start Study, an observational prebirth cohort. RWG was defined as a weight-for-age z score increase of at least 0.67 from birth to 3-7 months.

They found that RWG boosted the link between prepregnancy body mass index (ppBMI) and BMI z score, especially in female infants. Females exposed to both maternal obesity with RWG had an average BMI at the 94th percentile (1.50 increase in childhood BMI z score) “nearly at the cutoff for classification of obesity,” compared with those exposed to normal ppBMI with no RWG, who had an average childhood BMI at the 51st percentile.

“Currently, our nutrition recommendations as pediatricians are that all children are fed the same, essentially, after they’re born. We don’t have different growth parameters or different trajectories or targets for children who may have had different in utero exposures,” Dr. Gilley said.

Do some children need more monitoring for RWG?

Though we can’t necessarily draw conclusions from this one study, she says, the findings raise the question of whether children who were exposed in utero to obesity should be monitored for RWG more closely.

Lydia Shook, MD, Mass General Brigham maternal-fetal specialist and codirector of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said she was struck by the finding in this study that with female infants, but not males, RWG significantly modified the association between ppBMI and early childhood BMI z scores.

“It’s an interesting finding and should be followed up with larger cohorts,” she said, noting that some previous studies have shown males are more vulnerable to maternal obesity and RWG.

“[Often] when we stratify by sex, you really need larger groups to be able to see the differences well,” Dr. Shook said.

She said she also found it interesting that when the researchers adjusted for breastfeeding status or caloric intake in childhood, the findings did not substantially change.

“That’s something that would warrant further investigation in an observational study or controlled trial,” Dr. Shook said.

Preventing rapid weight gain

The authors note that they did not consider possible interventions for preventing RGW in the study, although there are many, Dr. Gilley said.

Dr. Gilley also noted that a limitation of this study is that the population studied was primarily White.

Recent studies have shown the benefits of responsive parenting (RP) interventions, including a large study in 2022 geared toward Black families to teach better infant sleep practices as a way to prevent rapid weight gain.

That study, which tested the SAAF intervention, (Strong African American Families) found that “RP infants were nearly half as likely to experience upward crossing of two major weight-for-age percentile lines (14.1%), compared with control infants (24.2%); P = .09; odds ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.24-1.12.”

Along with sleep interventions, Dr. Gilley said, some researchers are studying the effects on RWG of better paternal engagement, or more involvement with the Women, Infants, and Children program, particularly with lower-income families.

Other studies have looked at breastfeeding vs. formula feeding – “but there have been mixed results there” – and responsive feeding practices, such as teaching families to recognize when a baby is full.

Dr. Gilley said she hopes this work will help broaden the thinking when it comes to infant weight gain.

“We spend a lot of time thinking about babies who are not growing fast enough and very little time thinking about babies who are growing too fast,” she said, “especially in those first 4-6 months of life.”

Dr. Gilley points to a study that illustrates that point. Pesch et al. concluded in a 2021 study based on interviews that pediatricians “are uncertain about the concept, definition, management, and long-term risks of rapid infant weight gain.”

Authors and Dr. Gilley declare no relevant financial relationships.

Rapid weight gain (RWG) in infants and the mother’s prepregnancy overweight have a synergistic effect in increasing the odds that a child will develop overweight or obesity, new research suggests.

Findings were published online in Pediatrics.

Each factor has independently been associated with higher risk of childhood obesity but whether the two factors together exacerbate the risk has not been well studied, according to the authors led by Stephanie Gilley, MD, PhD, department of pediatrics, section of nutrition, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“Pediatric providers should monitor infants for RWG, especially in the context of maternal obesity, to reduce future risk of obesity,” the authors conclude.

Dr. Gilley’s team studied mother-infant dyads (n = 414) from the Healthy Start Study, an observational prebirth cohort. RWG was defined as a weight-for-age z score increase of at least 0.67 from birth to 3-7 months.

They found that RWG boosted the link between prepregnancy body mass index (ppBMI) and BMI z score, especially in female infants. Females exposed to both maternal obesity with RWG had an average BMI at the 94th percentile (1.50 increase in childhood BMI z score) “nearly at the cutoff for classification of obesity,” compared with those exposed to normal ppBMI with no RWG, who had an average childhood BMI at the 51st percentile.

“Currently, our nutrition recommendations as pediatricians are that all children are fed the same, essentially, after they’re born. We don’t have different growth parameters or different trajectories or targets for children who may have had different in utero exposures,” Dr. Gilley said.

Do some children need more monitoring for RWG?

Though we can’t necessarily draw conclusions from this one study, she says, the findings raise the question of whether children who were exposed in utero to obesity should be monitored for RWG more closely.

Lydia Shook, MD, Mass General Brigham maternal-fetal specialist and codirector of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said she was struck by the finding in this study that with female infants, but not males, RWG significantly modified the association between ppBMI and early childhood BMI z scores.

“It’s an interesting finding and should be followed up with larger cohorts,” she said, noting that some previous studies have shown males are more vulnerable to maternal obesity and RWG.

“[Often] when we stratify by sex, you really need larger groups to be able to see the differences well,” Dr. Shook said.

She said she also found it interesting that when the researchers adjusted for breastfeeding status or caloric intake in childhood, the findings did not substantially change.

“That’s something that would warrant further investigation in an observational study or controlled trial,” Dr. Shook said.

Preventing rapid weight gain

The authors note that they did not consider possible interventions for preventing RGW in the study, although there are many, Dr. Gilley said.

Dr. Gilley also noted that a limitation of this study is that the population studied was primarily White.

Recent studies have shown the benefits of responsive parenting (RP) interventions, including a large study in 2022 geared toward Black families to teach better infant sleep practices as a way to prevent rapid weight gain.

That study, which tested the SAAF intervention, (Strong African American Families) found that “RP infants were nearly half as likely to experience upward crossing of two major weight-for-age percentile lines (14.1%), compared with control infants (24.2%); P = .09; odds ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.24-1.12.”

Along with sleep interventions, Dr. Gilley said, some researchers are studying the effects on RWG of better paternal engagement, or more involvement with the Women, Infants, and Children program, particularly with lower-income families.

Other studies have looked at breastfeeding vs. formula feeding – “but there have been mixed results there” – and responsive feeding practices, such as teaching families to recognize when a baby is full.

Dr. Gilley said she hopes this work will help broaden the thinking when it comes to infant weight gain.

“We spend a lot of time thinking about babies who are not growing fast enough and very little time thinking about babies who are growing too fast,” she said, “especially in those first 4-6 months of life.”

Dr. Gilley points to a study that illustrates that point. Pesch et al. concluded in a 2021 study based on interviews that pediatricians “are uncertain about the concept, definition, management, and long-term risks of rapid infant weight gain.”

Authors and Dr. Gilley declare no relevant financial relationships.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Cervical screening often stops at 65, but should it?

“Did you love your wife?” asks a character in “Rose,” a book by Martin Cruz Smith.

“No, but she became a fact through perseverance,” the man replied.

Medicine also has such relationships, it seems – tentative ideas that turned into fact simply by existing long enough.

Age 65 as the cutoff for cervical screening may be one such example. It has existed for 27 years with limited science to back it up. That may soon change with the launch of a $3.3 million study that is being funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study is intended to provide a more solid foundation for the benefits and harms of cervical screening for women older than 65.

It’s an important issue: 20% of all cervical cancer cases are found in women who are older than 65. Most of these patients have late-stage disease, which can be fatal. In the United States, 35% of cervical cancer deaths occur after age 65. But women in this age group are usually no longer screened for cervical cancer.

Back in 1996, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that for women at average risk with adequate prior screening, cervical screening should stop at the age of 65. This recommendation has been carried forward year after year and has been incorporated into several other guidelines.

For example, current guidelines from the American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the USPSTF recommend that cervical screening stop at aged 65 for patients with adequate prior screening.

“Adequate screening” is defined as three consecutive normal Pap tests or two consecutive negative human papillomavirus tests or two consecutive negative co-tests within the prior 10 years, with the most recent screening within 5 years and with no precancerous lesions in the past 25 years.

This all sounds reasonable; however, for most women, medical records aren’t up to the task of providing a clean bill of cervical health over many decades.

Explained Sarah Feldman, MD, an associate professor in obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston: “You know, when a patient says to me at 65, ‘Should I continue screening?’ I say, ‘Do you have all your results?’ And they’ll say, ‘Well, I remember I had a sort of abnormal pap 15 years ago,’ and I say, ‘All right; well, who knows what that was?’ So I’ll continue screening.”

According to George Sawaya, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, up to 60% of women do not meet the criteria to end screening at age 65. This means that each year in the United States, approximately 1.7 million women turn 65 and should, in theory, continue to undergo screening for cervical cancer.

Unfortunately, the evidence base for the harms and benefits of cervical screening after age 65 is almost nonexistent – at least by the current standards of evidence-based medicine.

“We need to be clear that we don’t really know the appropriateness of the screening after 65,” said Dr. Sawaya, “which is ironic, because cervical cancer screening is probably the most commonly implemented cancer screening test in the country because it starts so early and ends so late and it’s applied so frequently.”

Dr. Feldman agrees that the age 65 cutoff is “somewhat arbitrary.” She said, “Why don’t they want to consider it continuing past 65? I don’t really understand, I have to be honest with you.”

So what’s the scientific evidence backing up the 27-year-old recommendation?

In 2018, the USPSTF’s cervical-screening guidelines concluded “with moderate certainty that the benefits of screening in women older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer do not outweigh the potential harms.”

This recommendation was based on a new decision model commissioned by the USPSTF. The model was needed because, as noted by the guidelines’ authors, “None of the screening trials enrolled women older than 65 years, so direct evidence on when to stop screening is not available.”

In 2020, the ACS carried out a fresh literature review and published its own recommendations. The ACS concluded that “the evidence for the effectiveness of screening beyond age 65 is limited, based solely on observational and modeling studies.”

As a result, the ACS assigned a “qualified recommendation” to the age-65 moratorium (defined as “less certainty about the balance of benefits and harms or about patients’ values and preferences”).

Most recently, the 2021 Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines, published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, endorsed the recommendations of the USPSTF.

Dr. Sawaya said, “The whole issue about screening over 65 is complicated from a lot of perspectives. We don’t know a lot about the safety. We don’t really know a lot about patients’ perceptions of it. But we do know that there has to be an upper age limit after which screening is just simply imprudent.”

Dr. Sawaya acknowledges that there exists a “heck-why-not” attitude toward cervical screening after 65 among some physicians, given that the tests are quick and cheap and could save a life, but he sounds a note of caution.

“It’s like when we used to use old cameras: the film was cheap, but the developing was really expensive,” Dr. Sawaya said. “So it’s not necessarily about the tests being cheap, it’s about the cascade of events [that follow].”

Follow-up for cervical cancer can be more hazardous for a postmenopausal patient than for a younger woman, explained Dr. Sawaya, because the transformation zone of the cervix may be difficult to see on colposcopy. Instead of a straightforward 5-minute procedure in the doctor’s office, the older patient may need the operating room simply to provide the first biopsy.

In addition, treatments such as cone biopsy, loop excision, or ablation are also more worrying for older women, said Dr. Sawaya, “So you start thinking about the risks of anesthesia, you start thinking about the risks of bleeding and infection, etc. And these have not been well described in older people.”

To add to the uncertainty about the merits and risks of hunting out cervical cancer in older women, a lot has changed in women’s health since 1996.

Explained Dr. Sawaya, “This stake was put in the ground in 1996, ... but since that time, life expectancy has gained 5 years. So a logical person would say, ‘Oh, well, let’s just say it should be 70 now, right?’ [But] can we even use old studies to inform the current cohort of women who are entering this 65-year-and-older age group?”

To answer all these questions, a 5-year, $3.3 million study funded by the NIH through the National Cancer Institute is now underway.

The project, named Comparative Effectiveness Research to Validate and Improve Cervical Cancer Screening (CERVICCS 2), will be led by Dr. Sawaya and Michael Silverberg, PhD, associate director of the Behavioral Health, Aging and Infectious Diseases Section of Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s Division of Research.

It’s not possible to conduct a true randomized controlled trial in this field of medicine for ethical reasons, so CERVICCS 2 will emulate a randomized study by following the fate of approximately 280,000 women older than 65 who were long-term members of two large health systems during 2005-2022. – both before and after the crucial age 65 cutoff.

The California study will also look at the downsides of diagnostic procedures and surgical interventions that follow a positive screening result after the age of 65 and the personal experiences of the women involved.

Dr. Sawaya and Dr. Silverberg’s team will use software that emulates a clinical trial by utilizing observational data to compare the benefits and risks of screening continuation or screening cessation after age 65.

In effect, after 27 years of loyalty to a recommendation supported by low-quality evidence, medicine will finally have a reliable answer to the question, Should we continue to look for cervical cancer in women over 65?

Dr. Sawaya concluded: “There’s very few things that are packaged away and thought to be just the truth. And this is why we always have to be vigilant. ... And that’s what keeps science so interesting and exciting.”

Dr. Sawaya has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Feldman writes for UpToDate and receives several NIH grants.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Did you love your wife?” asks a character in “Rose,” a book by Martin Cruz Smith.

“No, but she became a fact through perseverance,” the man replied.

Medicine also has such relationships, it seems – tentative ideas that turned into fact simply by existing long enough.

Age 65 as the cutoff for cervical screening may be one such example. It has existed for 27 years with limited science to back it up. That may soon change with the launch of a $3.3 million study that is being funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study is intended to provide a more solid foundation for the benefits and harms of cervical screening for women older than 65.

It’s an important issue: 20% of all cervical cancer cases are found in women who are older than 65. Most of these patients have late-stage disease, which can be fatal. In the United States, 35% of cervical cancer deaths occur after age 65. But women in this age group are usually no longer screened for cervical cancer.

Back in 1996, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that for women at average risk with adequate prior screening, cervical screening should stop at the age of 65. This recommendation has been carried forward year after year and has been incorporated into several other guidelines.

For example, current guidelines from the American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the USPSTF recommend that cervical screening stop at aged 65 for patients with adequate prior screening.

“Adequate screening” is defined as three consecutive normal Pap tests or two consecutive negative human papillomavirus tests or two consecutive negative co-tests within the prior 10 years, with the most recent screening within 5 years and with no precancerous lesions in the past 25 years.

This all sounds reasonable; however, for most women, medical records aren’t up to the task of providing a clean bill of cervical health over many decades.

Explained Sarah Feldman, MD, an associate professor in obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston: “You know, when a patient says to me at 65, ‘Should I continue screening?’ I say, ‘Do you have all your results?’ And they’ll say, ‘Well, I remember I had a sort of abnormal pap 15 years ago,’ and I say, ‘All right; well, who knows what that was?’ So I’ll continue screening.”

According to George Sawaya, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, up to 60% of women do not meet the criteria to end screening at age 65. This means that each year in the United States, approximately 1.7 million women turn 65 and should, in theory, continue to undergo screening for cervical cancer.

Unfortunately, the evidence base for the harms and benefits of cervical screening after age 65 is almost nonexistent – at least by the current standards of evidence-based medicine.

“We need to be clear that we don’t really know the appropriateness of the screening after 65,” said Dr. Sawaya, “which is ironic, because cervical cancer screening is probably the most commonly implemented cancer screening test in the country because it starts so early and ends so late and it’s applied so frequently.”

Dr. Feldman agrees that the age 65 cutoff is “somewhat arbitrary.” She said, “Why don’t they want to consider it continuing past 65? I don’t really understand, I have to be honest with you.”

So what’s the scientific evidence backing up the 27-year-old recommendation?

In 2018, the USPSTF’s cervical-screening guidelines concluded “with moderate certainty that the benefits of screening in women older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer do not outweigh the potential harms.”

This recommendation was based on a new decision model commissioned by the USPSTF. The model was needed because, as noted by the guidelines’ authors, “None of the screening trials enrolled women older than 65 years, so direct evidence on when to stop screening is not available.”

In 2020, the ACS carried out a fresh literature review and published its own recommendations. The ACS concluded that “the evidence for the effectiveness of screening beyond age 65 is limited, based solely on observational and modeling studies.”

As a result, the ACS assigned a “qualified recommendation” to the age-65 moratorium (defined as “less certainty about the balance of benefits and harms or about patients’ values and preferences”).

Most recently, the 2021 Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines, published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, endorsed the recommendations of the USPSTF.

Dr. Sawaya said, “The whole issue about screening over 65 is complicated from a lot of perspectives. We don’t know a lot about the safety. We don’t really know a lot about patients’ perceptions of it. But we do know that there has to be an upper age limit after which screening is just simply imprudent.”

Dr. Sawaya acknowledges that there exists a “heck-why-not” attitude toward cervical screening after 65 among some physicians, given that the tests are quick and cheap and could save a life, but he sounds a note of caution.

“It’s like when we used to use old cameras: the film was cheap, but the developing was really expensive,” Dr. Sawaya said. “So it’s not necessarily about the tests being cheap, it’s about the cascade of events [that follow].”

Follow-up for cervical cancer can be more hazardous for a postmenopausal patient than for a younger woman, explained Dr. Sawaya, because the transformation zone of the cervix may be difficult to see on colposcopy. Instead of a straightforward 5-minute procedure in the doctor’s office, the older patient may need the operating room simply to provide the first biopsy.

In addition, treatments such as cone biopsy, loop excision, or ablation are also more worrying for older women, said Dr. Sawaya, “So you start thinking about the risks of anesthesia, you start thinking about the risks of bleeding and infection, etc. And these have not been well described in older people.”

To add to the uncertainty about the merits and risks of hunting out cervical cancer in older women, a lot has changed in women’s health since 1996.

Explained Dr. Sawaya, “This stake was put in the ground in 1996, ... but since that time, life expectancy has gained 5 years. So a logical person would say, ‘Oh, well, let’s just say it should be 70 now, right?’ [But] can we even use old studies to inform the current cohort of women who are entering this 65-year-and-older age group?”

To answer all these questions, a 5-year, $3.3 million study funded by the NIH through the National Cancer Institute is now underway.

The project, named Comparative Effectiveness Research to Validate and Improve Cervical Cancer Screening (CERVICCS 2), will be led by Dr. Sawaya and Michael Silverberg, PhD, associate director of the Behavioral Health, Aging and Infectious Diseases Section of Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s Division of Research.

It’s not possible to conduct a true randomized controlled trial in this field of medicine for ethical reasons, so CERVICCS 2 will emulate a randomized study by following the fate of approximately 280,000 women older than 65 who were long-term members of two large health systems during 2005-2022. – both before and after the crucial age 65 cutoff.

The California study will also look at the downsides of diagnostic procedures and surgical interventions that follow a positive screening result after the age of 65 and the personal experiences of the women involved.

Dr. Sawaya and Dr. Silverberg’s team will use software that emulates a clinical trial by utilizing observational data to compare the benefits and risks of screening continuation or screening cessation after age 65.

In effect, after 27 years of loyalty to a recommendation supported by low-quality evidence, medicine will finally have a reliable answer to the question, Should we continue to look for cervical cancer in women over 65?

Dr. Sawaya concluded: “There’s very few things that are packaged away and thought to be just the truth. And this is why we always have to be vigilant. ... And that’s what keeps science so interesting and exciting.”

Dr. Sawaya has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Feldman writes for UpToDate and receives several NIH grants.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Did you love your wife?” asks a character in “Rose,” a book by Martin Cruz Smith.

“No, but she became a fact through perseverance,” the man replied.

Medicine also has such relationships, it seems – tentative ideas that turned into fact simply by existing long enough.

Age 65 as the cutoff for cervical screening may be one such example. It has existed for 27 years with limited science to back it up. That may soon change with the launch of a $3.3 million study that is being funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study is intended to provide a more solid foundation for the benefits and harms of cervical screening for women older than 65.

It’s an important issue: 20% of all cervical cancer cases are found in women who are older than 65. Most of these patients have late-stage disease, which can be fatal. In the United States, 35% of cervical cancer deaths occur after age 65. But women in this age group are usually no longer screened for cervical cancer.

Back in 1996, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that for women at average risk with adequate prior screening, cervical screening should stop at the age of 65. This recommendation has been carried forward year after year and has been incorporated into several other guidelines.

For example, current guidelines from the American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the USPSTF recommend that cervical screening stop at aged 65 for patients with adequate prior screening.

“Adequate screening” is defined as three consecutive normal Pap tests or two consecutive negative human papillomavirus tests or two consecutive negative co-tests within the prior 10 years, with the most recent screening within 5 years and with no precancerous lesions in the past 25 years.

This all sounds reasonable; however, for most women, medical records aren’t up to the task of providing a clean bill of cervical health over many decades.

Explained Sarah Feldman, MD, an associate professor in obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston: “You know, when a patient says to me at 65, ‘Should I continue screening?’ I say, ‘Do you have all your results?’ And they’ll say, ‘Well, I remember I had a sort of abnormal pap 15 years ago,’ and I say, ‘All right; well, who knows what that was?’ So I’ll continue screening.”

According to George Sawaya, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, up to 60% of women do not meet the criteria to end screening at age 65. This means that each year in the United States, approximately 1.7 million women turn 65 and should, in theory, continue to undergo screening for cervical cancer.

Unfortunately, the evidence base for the harms and benefits of cervical screening after age 65 is almost nonexistent – at least by the current standards of evidence-based medicine.

“We need to be clear that we don’t really know the appropriateness of the screening after 65,” said Dr. Sawaya, “which is ironic, because cervical cancer screening is probably the most commonly implemented cancer screening test in the country because it starts so early and ends so late and it’s applied so frequently.”

Dr. Feldman agrees that the age 65 cutoff is “somewhat arbitrary.” She said, “Why don’t they want to consider it continuing past 65? I don’t really understand, I have to be honest with you.”

So what’s the scientific evidence backing up the 27-year-old recommendation?

In 2018, the USPSTF’s cervical-screening guidelines concluded “with moderate certainty that the benefits of screening in women older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer do not outweigh the potential harms.”

This recommendation was based on a new decision model commissioned by the USPSTF. The model was needed because, as noted by the guidelines’ authors, “None of the screening trials enrolled women older than 65 years, so direct evidence on when to stop screening is not available.”

In 2020, the ACS carried out a fresh literature review and published its own recommendations. The ACS concluded that “the evidence for the effectiveness of screening beyond age 65 is limited, based solely on observational and modeling studies.”

As a result, the ACS assigned a “qualified recommendation” to the age-65 moratorium (defined as “less certainty about the balance of benefits and harms or about patients’ values and preferences”).

Most recently, the 2021 Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines, published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, endorsed the recommendations of the USPSTF.

Dr. Sawaya said, “The whole issue about screening over 65 is complicated from a lot of perspectives. We don’t know a lot about the safety. We don’t really know a lot about patients’ perceptions of it. But we do know that there has to be an upper age limit after which screening is just simply imprudent.”

Dr. Sawaya acknowledges that there exists a “heck-why-not” attitude toward cervical screening after 65 among some physicians, given that the tests are quick and cheap and could save a life, but he sounds a note of caution.

“It’s like when we used to use old cameras: the film was cheap, but the developing was really expensive,” Dr. Sawaya said. “So it’s not necessarily about the tests being cheap, it’s about the cascade of events [that follow].”

Follow-up for cervical cancer can be more hazardous for a postmenopausal patient than for a younger woman, explained Dr. Sawaya, because the transformation zone of the cervix may be difficult to see on colposcopy. Instead of a straightforward 5-minute procedure in the doctor’s office, the older patient may need the operating room simply to provide the first biopsy.

In addition, treatments such as cone biopsy, loop excision, or ablation are also more worrying for older women, said Dr. Sawaya, “So you start thinking about the risks of anesthesia, you start thinking about the risks of bleeding and infection, etc. And these have not been well described in older people.”

To add to the uncertainty about the merits and risks of hunting out cervical cancer in older women, a lot has changed in women’s health since 1996.

Explained Dr. Sawaya, “This stake was put in the ground in 1996, ... but since that time, life expectancy has gained 5 years. So a logical person would say, ‘Oh, well, let’s just say it should be 70 now, right?’ [But] can we even use old studies to inform the current cohort of women who are entering this 65-year-and-older age group?”

To answer all these questions, a 5-year, $3.3 million study funded by the NIH through the National Cancer Institute is now underway.

The project, named Comparative Effectiveness Research to Validate and Improve Cervical Cancer Screening (CERVICCS 2), will be led by Dr. Sawaya and Michael Silverberg, PhD, associate director of the Behavioral Health, Aging and Infectious Diseases Section of Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s Division of Research.

It’s not possible to conduct a true randomized controlled trial in this field of medicine for ethical reasons, so CERVICCS 2 will emulate a randomized study by following the fate of approximately 280,000 women older than 65 who were long-term members of two large health systems during 2005-2022. – both before and after the crucial age 65 cutoff.

The California study will also look at the downsides of diagnostic procedures and surgical interventions that follow a positive screening result after the age of 65 and the personal experiences of the women involved.

Dr. Sawaya and Dr. Silverberg’s team will use software that emulates a clinical trial by utilizing observational data to compare the benefits and risks of screening continuation or screening cessation after age 65.

In effect, after 27 years of loyalty to a recommendation supported by low-quality evidence, medicine will finally have a reliable answer to the question, Should we continue to look for cervical cancer in women over 65?

Dr. Sawaya concluded: “There’s very few things that are packaged away and thought to be just the truth. And this is why we always have to be vigilant. ... And that’s what keeps science so interesting and exciting.”

Dr. Sawaya has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Feldman writes for UpToDate and receives several NIH grants.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cesarean deliveries drop in women at low risk

Although clinically indicated cesarean deliveries may improve outcomes for mothers and infants, “when not clinically indicated, cesarean delivery is a major surgical intervention that increases risk for adverse outcomes,” wrote Anna M. Frappaolo of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and colleagues.

The Healthy People 2030 campaign includes the reduction of cesarean deliveries, but trends in these procedures, especially with regard to diagnoses of labor arrest, have not been well studied, the researchers said.

In an analysis published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed delivery hospitalizations using data from the National Inpatient Sample from 2000 to 2019.

Births deemed low risk for cesarean delivery were identified by using criteria of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and additional criteria, and joinpoint regression analysis was used to estimate changes.

The researchers examined overall trends in cesarean deliveries as well as trends for three specific diagnoses: nonreassuring fetal status, labor arrest, and obstructed labor.

The final analysis included 40,517,867 deliveries; of these, 4,885,716 (12.1%) were cesarean deliveries.

Overall, cesarean deliveries in patients deemed at low risk increased from 9.7% in 2000 to 13.9% in 2009, then plateaued and decreased from 13.0% in 2012 to 11.1% in 2019. The average annual percentage change (AAPC) for cesarean delivery was 6.4% for the years from 2000 to 2005, 1.2% from 2005 to 2009, and −2.2% from 2009 to 2019.

Cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal status increased over the entire study period, from 3.4% in 2000 to 5.1% in 2019. By contrast, overall cesarean delivery for labor arrest increased from 3.6% in 2000 to a high of 4.8% in 2009, then decreased to 2.7% in 2019. Cesarean deliveries with a diagnosis of obstructed labor decreased from 0.9% in 2008 to 0.3% in 2019.

More specifically, cesarean deliveries for labor arrest in the active phase, latent phase, and second stage of labor increased from 1.5% to 2.1%, 1.1% to 1.5%, and 0.9% to 1.3%, respectively, from 2000 to 2009, and decreased from 2.1% to 1.7% for the active phase, from 1.5% to 1.2% for the latent phase, and from 1.2% to 0.9% for the second stage between 2010 and 2019.

Patients with increased odds of cesarean delivery were older (aged 35-39 years vs. 25-29 years, adjusted odds ratio 1.27), delivered in a hospital in the South vs. the Northeast of the United States (aOR 1.11), and were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White (OR 1.23).

Notably, changes in nomenclature and interpretation of intrapartum electronic fetal heart monitoring occurred during the study period, with recommendations for the adoption of a three-tiered system for fetal heart rate patterns in 2008. “It is possible that current evidence and nomenclature related to intrapartum FHR interpretation may result in identification of a larger number of fetuses deemed at indeterminate risk for abnormal acid-base status,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of administrative discharge data rather than clinical records, the exclusion of patients with chronic conditions associated with cesarean delivery, changes in billing codes during the study period, and the inability to account for the effect of health factors, maternal age, and use of assisted reproductive technology, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and 20-year study period, as well as the stratification of labor arrest by stage, and suggest uptake of newer recommendations, they said. “Future reductions in cesarean deliveries among patients at low risk for cesarean delivery may be dependent on improved assessment of intrapartum fetal status,” they concluded.

Consider populations and outcomes in cesarean risk assessment

The decreasing rates of cesarean deliveries in the current study can be seen as positive, but more research is needed to examine maternal and neonatal outcomes, and to consider other conditions that affect risk for cesarean delivery, Paolo Ivo Cavoretto, MD, and Massimo Candiani, MD, of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, and Antonio Farina, MD, of the University of Bologna, Italy, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Notably, the study authors identified a population aged 15-39 years as low risk, and an increased risk for cesarean delivery within this range increased with age. “Maternal age remains a major risk factor associated with the risk of cesarean delivery, both from results of this study and those of previous analyses assessing its independence from other related risk factors,” the editorialists said.

The study findings also reflect the changes in standards for labor duration during the study period, they noted. The longer duration of labor may reduce cesarean delivery rates, but it is not without maternal and fetal-neonatal risks, they wrote.

“To be sure that the described trend of cesarean delivery rate reduction can be considered positive, there would be the theoretical need to analyze other maternal-fetal-neonatal outcomes (e.g., rates of operative deliveries, neonatal acidemia, intensive care unit use, maternal hemorrhage, pelvic floor trauma and dysfunction, and psychological distress),” the editorialists concluded.

More research needed to explore clinical decisions

“Reducing the cesarean delivery rate is a top priority, but evidence is lacking on an optimal rate that improves maternal and neonatal outcomes,” Iris Krishna, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Hospital quality and safety committees have been working to decrease cesarean deliveries amongst low-risk women, and identifying contemporary trends gives us insight on whether some of these efforts have translated to a lower cesarean delivery rate,” she said.

Dr. Krishna said she was not surprised by the higher cesarean section rate in the South. “The decision for cesarean delivery is multifaceted, and although this study was not able to assess clinical indications for cesarean delivery or maternal and fetal outcomes, we cannot ignore that social determinants of health contribute greatly to overall health outcomes,” she said. The trends in the current study further underscore the geographic disparities in access to health care present in the South, she added.

“This study notes that cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal status increased; however, nonreassuring fetal status as an indication for cesarean delivery can be subjective,” Dr. Krishna said. “Hospital quality and safety committees should consider reviewing the clinical scenarios that led to this decision to identify opportunities for improvement and further education,” she said.

“Defining contemporary trends in cesarean delivery for low-risk patients has merit, but the study findings should be interpreted with caution,” said Dr. Krishna, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News advisory board. More research is needed to define an optimal cesarean section rate that promotes positive maternal and fetal outcomes, and to determine whether identifying an optimal rate should be based on patient risk profiles, she said.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Ms. Frappaolo had no financial conflicts to disclose; nor did the editorial authors or Dr. Krishna.

Although clinically indicated cesarean deliveries may improve outcomes for mothers and infants, “when not clinically indicated, cesarean delivery is a major surgical intervention that increases risk for adverse outcomes,” wrote Anna M. Frappaolo of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and colleagues.

The Healthy People 2030 campaign includes the reduction of cesarean deliveries, but trends in these procedures, especially with regard to diagnoses of labor arrest, have not been well studied, the researchers said.

In an analysis published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed delivery hospitalizations using data from the National Inpatient Sample from 2000 to 2019.

Births deemed low risk for cesarean delivery were identified by using criteria of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and additional criteria, and joinpoint regression analysis was used to estimate changes.

The researchers examined overall trends in cesarean deliveries as well as trends for three specific diagnoses: nonreassuring fetal status, labor arrest, and obstructed labor.

The final analysis included 40,517,867 deliveries; of these, 4,885,716 (12.1%) were cesarean deliveries.

Overall, cesarean deliveries in patients deemed at low risk increased from 9.7% in 2000 to 13.9% in 2009, then plateaued and decreased from 13.0% in 2012 to 11.1% in 2019. The average annual percentage change (AAPC) for cesarean delivery was 6.4% for the years from 2000 to 2005, 1.2% from 2005 to 2009, and −2.2% from 2009 to 2019.

Cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal status increased over the entire study period, from 3.4% in 2000 to 5.1% in 2019. By contrast, overall cesarean delivery for labor arrest increased from 3.6% in 2000 to a high of 4.8% in 2009, then decreased to 2.7% in 2019. Cesarean deliveries with a diagnosis of obstructed labor decreased from 0.9% in 2008 to 0.3% in 2019.

More specifically, cesarean deliveries for labor arrest in the active phase, latent phase, and second stage of labor increased from 1.5% to 2.1%, 1.1% to 1.5%, and 0.9% to 1.3%, respectively, from 2000 to 2009, and decreased from 2.1% to 1.7% for the active phase, from 1.5% to 1.2% for the latent phase, and from 1.2% to 0.9% for the second stage between 2010 and 2019.

Patients with increased odds of cesarean delivery were older (aged 35-39 years vs. 25-29 years, adjusted odds ratio 1.27), delivered in a hospital in the South vs. the Northeast of the United States (aOR 1.11), and were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White (OR 1.23).

Notably, changes in nomenclature and interpretation of intrapartum electronic fetal heart monitoring occurred during the study period, with recommendations for the adoption of a three-tiered system for fetal heart rate patterns in 2008. “It is possible that current evidence and nomenclature related to intrapartum FHR interpretation may result in identification of a larger number of fetuses deemed at indeterminate risk for abnormal acid-base status,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of administrative discharge data rather than clinical records, the exclusion of patients with chronic conditions associated with cesarean delivery, changes in billing codes during the study period, and the inability to account for the effect of health factors, maternal age, and use of assisted reproductive technology, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and 20-year study period, as well as the stratification of labor arrest by stage, and suggest uptake of newer recommendations, they said. “Future reductions in cesarean deliveries among patients at low risk for cesarean delivery may be dependent on improved assessment of intrapartum fetal status,” they concluded.

Consider populations and outcomes in cesarean risk assessment

The decreasing rates of cesarean deliveries in the current study can be seen as positive, but more research is needed to examine maternal and neonatal outcomes, and to consider other conditions that affect risk for cesarean delivery, Paolo Ivo Cavoretto, MD, and Massimo Candiani, MD, of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, and Antonio Farina, MD, of the University of Bologna, Italy, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Notably, the study authors identified a population aged 15-39 years as low risk, and an increased risk for cesarean delivery within this range increased with age. “Maternal age remains a major risk factor associated with the risk of cesarean delivery, both from results of this study and those of previous analyses assessing its independence from other related risk factors,” the editorialists said.

The study findings also reflect the changes in standards for labor duration during the study period, they noted. The longer duration of labor may reduce cesarean delivery rates, but it is not without maternal and fetal-neonatal risks, they wrote.

“To be sure that the described trend of cesarean delivery rate reduction can be considered positive, there would be the theoretical need to analyze other maternal-fetal-neonatal outcomes (e.g., rates of operative deliveries, neonatal acidemia, intensive care unit use, maternal hemorrhage, pelvic floor trauma and dysfunction, and psychological distress),” the editorialists concluded.

More research needed to explore clinical decisions

“Reducing the cesarean delivery rate is a top priority, but evidence is lacking on an optimal rate that improves maternal and neonatal outcomes,” Iris Krishna, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Hospital quality and safety committees have been working to decrease cesarean deliveries amongst low-risk women, and identifying contemporary trends gives us insight on whether some of these efforts have translated to a lower cesarean delivery rate,” she said.

Dr. Krishna said she was not surprised by the higher cesarean section rate in the South. “The decision for cesarean delivery is multifaceted, and although this study was not able to assess clinical indications for cesarean delivery or maternal and fetal outcomes, we cannot ignore that social determinants of health contribute greatly to overall health outcomes,” she said. The trends in the current study further underscore the geographic disparities in access to health care present in the South, she added.

“This study notes that cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal status increased; however, nonreassuring fetal status as an indication for cesarean delivery can be subjective,” Dr. Krishna said. “Hospital quality and safety committees should consider reviewing the clinical scenarios that led to this decision to identify opportunities for improvement and further education,” she said.

“Defining contemporary trends in cesarean delivery for low-risk patients has merit, but the study findings should be interpreted with caution,” said Dr. Krishna, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News advisory board. More research is needed to define an optimal cesarean section rate that promotes positive maternal and fetal outcomes, and to determine whether identifying an optimal rate should be based on patient risk profiles, she said.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Ms. Frappaolo had no financial conflicts to disclose; nor did the editorial authors or Dr. Krishna.

Although clinically indicated cesarean deliveries may improve outcomes for mothers and infants, “when not clinically indicated, cesarean delivery is a major surgical intervention that increases risk for adverse outcomes,” wrote Anna M. Frappaolo of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and colleagues.

The Healthy People 2030 campaign includes the reduction of cesarean deliveries, but trends in these procedures, especially with regard to diagnoses of labor arrest, have not been well studied, the researchers said.

In an analysis published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed delivery hospitalizations using data from the National Inpatient Sample from 2000 to 2019.

Births deemed low risk for cesarean delivery were identified by using criteria of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and additional criteria, and joinpoint regression analysis was used to estimate changes.

The researchers examined overall trends in cesarean deliveries as well as trends for three specific diagnoses: nonreassuring fetal status, labor arrest, and obstructed labor.

The final analysis included 40,517,867 deliveries; of these, 4,885,716 (12.1%) were cesarean deliveries.

Overall, cesarean deliveries in patients deemed at low risk increased from 9.7% in 2000 to 13.9% in 2009, then plateaued and decreased from 13.0% in 2012 to 11.1% in 2019. The average annual percentage change (AAPC) for cesarean delivery was 6.4% for the years from 2000 to 2005, 1.2% from 2005 to 2009, and −2.2% from 2009 to 2019.

Cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal status increased over the entire study period, from 3.4% in 2000 to 5.1% in 2019. By contrast, overall cesarean delivery for labor arrest increased from 3.6% in 2000 to a high of 4.8% in 2009, then decreased to 2.7% in 2019. Cesarean deliveries with a diagnosis of obstructed labor decreased from 0.9% in 2008 to 0.3% in 2019.

More specifically, cesarean deliveries for labor arrest in the active phase, latent phase, and second stage of labor increased from 1.5% to 2.1%, 1.1% to 1.5%, and 0.9% to 1.3%, respectively, from 2000 to 2009, and decreased from 2.1% to 1.7% for the active phase, from 1.5% to 1.2% for the latent phase, and from 1.2% to 0.9% for the second stage between 2010 and 2019.

Patients with increased odds of cesarean delivery were older (aged 35-39 years vs. 25-29 years, adjusted odds ratio 1.27), delivered in a hospital in the South vs. the Northeast of the United States (aOR 1.11), and were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White (OR 1.23).

Notably, changes in nomenclature and interpretation of intrapartum electronic fetal heart monitoring occurred during the study period, with recommendations for the adoption of a three-tiered system for fetal heart rate patterns in 2008. “It is possible that current evidence and nomenclature related to intrapartum FHR interpretation may result in identification of a larger number of fetuses deemed at indeterminate risk for abnormal acid-base status,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of administrative discharge data rather than clinical records, the exclusion of patients with chronic conditions associated with cesarean delivery, changes in billing codes during the study period, and the inability to account for the effect of health factors, maternal age, and use of assisted reproductive technology, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and 20-year study period, as well as the stratification of labor arrest by stage, and suggest uptake of newer recommendations, they said. “Future reductions in cesarean deliveries among patients at low risk for cesarean delivery may be dependent on improved assessment of intrapartum fetal status,” they concluded.

Consider populations and outcomes in cesarean risk assessment

The decreasing rates of cesarean deliveries in the current study can be seen as positive, but more research is needed to examine maternal and neonatal outcomes, and to consider other conditions that affect risk for cesarean delivery, Paolo Ivo Cavoretto, MD, and Massimo Candiani, MD, of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, and Antonio Farina, MD, of the University of Bologna, Italy, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Notably, the study authors identified a population aged 15-39 years as low risk, and an increased risk for cesarean delivery within this range increased with age. “Maternal age remains a major risk factor associated with the risk of cesarean delivery, both from results of this study and those of previous analyses assessing its independence from other related risk factors,” the editorialists said.

The study findings also reflect the changes in standards for labor duration during the study period, they noted. The longer duration of labor may reduce cesarean delivery rates, but it is not without maternal and fetal-neonatal risks, they wrote.

“To be sure that the described trend of cesarean delivery rate reduction can be considered positive, there would be the theoretical need to analyze other maternal-fetal-neonatal outcomes (e.g., rates of operative deliveries, neonatal acidemia, intensive care unit use, maternal hemorrhage, pelvic floor trauma and dysfunction, and psychological distress),” the editorialists concluded.

More research needed to explore clinical decisions

“Reducing the cesarean delivery rate is a top priority, but evidence is lacking on an optimal rate that improves maternal and neonatal outcomes,” Iris Krishna, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Hospital quality and safety committees have been working to decrease cesarean deliveries amongst low-risk women, and identifying contemporary trends gives us insight on whether some of these efforts have translated to a lower cesarean delivery rate,” she said.

Dr. Krishna said she was not surprised by the higher cesarean section rate in the South. “The decision for cesarean delivery is multifaceted, and although this study was not able to assess clinical indications for cesarean delivery or maternal and fetal outcomes, we cannot ignore that social determinants of health contribute greatly to overall health outcomes,” she said. The trends in the current study further underscore the geographic disparities in access to health care present in the South, she added.

“This study notes that cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal status increased; however, nonreassuring fetal status as an indication for cesarean delivery can be subjective,” Dr. Krishna said. “Hospital quality and safety committees should consider reviewing the clinical scenarios that led to this decision to identify opportunities for improvement and further education,” she said.

“Defining contemporary trends in cesarean delivery for low-risk patients has merit, but the study findings should be interpreted with caution,” said Dr. Krishna, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News advisory board. More research is needed to define an optimal cesarean section rate that promotes positive maternal and fetal outcomes, and to determine whether identifying an optimal rate should be based on patient risk profiles, she said.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Ms. Frappaolo had no financial conflicts to disclose; nor did the editorial authors or Dr. Krishna.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

2023 Update on fertility

Total fertility rate and fertility care: Demographic shifts and changing demands

Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

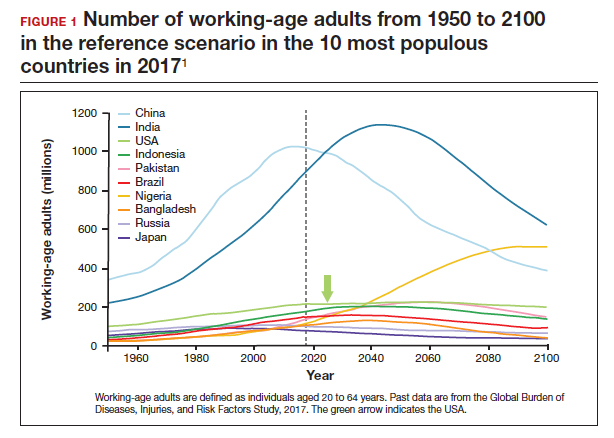

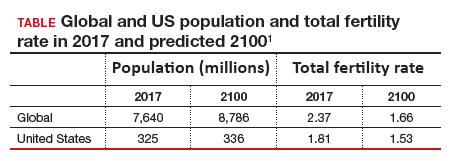

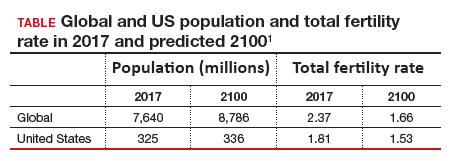

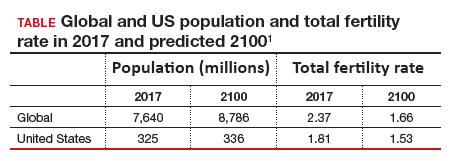

The total fertility rate (TFR) globally is decreasing rapidly, and in the United States it is now 1.8 births per woman, well below the required replacement rate of 2.1 that maintains the population.1 These reduced TFRs result in significant demographic shifts that affect the economy, workforce, society, health care needs, environment, and geopolitical standing of every country. These changes also will shift demands for the volume and type of services delivered by women’s health care clinicians.

In addition to the TFR, mortality rates and migration rates play essential roles in determining a country’s population.2 Anticipation and planning for these population and health care service changes by each country’s government, business, professionals, and other stakeholders are imperative to manage their impact and optimize quality of life.

US standings in projected population and economic growth

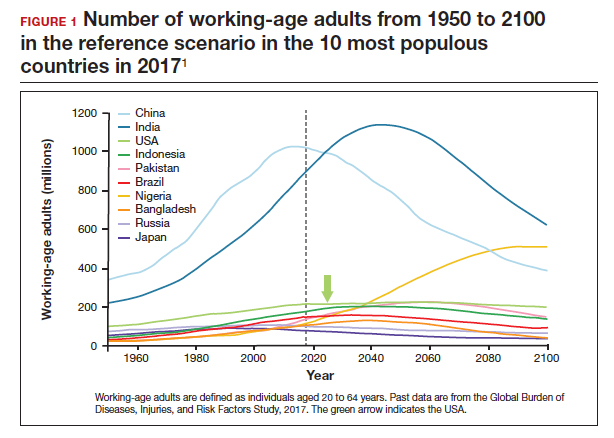

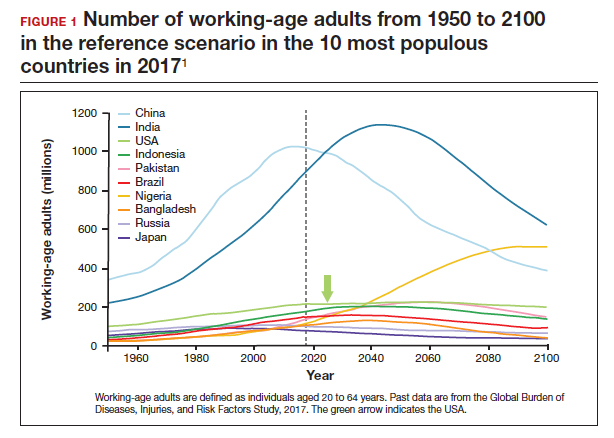

The US population is predicted to peak at 364 million in 2062 and decrease to 336 million in 2100, at which time it will be the fourth largest country in the world, according to a forecasting analysis by Vollset and colleagues.1 China is expected to become the biggest economy in the world in 2035, but this is predicted to change because of its decreasing population so that by 2098 the United States will again be the country with the largest economy (FIGURE 1).1

For the United States to maintain its economic and geopolitical standing, it is important to have policies that promote families. Other countries, especially in northern Europe, have implemented such policies. These include education of the population,economic incentives to create families, extended day care, and favorable tax policies.3 They also include increased access to family-forming fertility care. Such policies in Denmark have resulted in approximately 10% of all children being born from assisted reproductive technology (ART), compared with about 1.5% in the United States. Other countries have similar policies and success in increasing the number of children born from ART.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), RESOLVE: the National Infertility Association, the American Medical Women’s Association (AMWA), and others are promoting the need for increased access to fertility care and family-forming resources, primarily through family-forming benefits provided by companies.4 Such benefits are critical since the primary reason most people do not undergo fertility care is a lack of affordability. Only 1 person in 4 in the United States who needs fertility care receives treatment. Increased access would result in more babies being born to help address the reduced TFR.

Educational access, contraceptive goals, and access to fertility care

Continued trends in women’s educational attainment and access to contraception will hasten declines in the fertility rate and slow population growth (TABLE).1 These educational and contraceptive goals also must be pursued so that every person can achieve their individual reproductive life goals of having a family if and when they want to have a family. In addition to helping address the decreasing TFR, there is a fundamental right to found a family, as stated in the United Nations charter. It is a matter of social justice and equity that everyone who wants to have a family can access reproductive care on a nondiscriminatory basis when needed.

While the need for more and better insurance coverage for infertility has been well documented for many years, the decreasing TFR in the United States is an additional compelling reason that government, business, and other stakeholders should continue to increase access to fertility benefits and care. Women’s health care clinicians are encouraged to support these initiatives that also improve quality of life, equity, and social justice.

The decreasing global and US total fertility rate causes significant demographic changes, with major socioeconomic and health care consequences. The reduced TFR impacts women’s health care services, including the need for increased access to fertility care. Government and corporate policies, including those that improve access to fertility care, will help society adapt to these changes.

Continue to: A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO...

A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO

Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

Ovulatory disorders are well-recognized and common causes of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). Ovulatory disorders occur on a spectrum, with the most severe form being anovulation, and comprise a heterogeneous group that has been classically categorized based on an initial monograph published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1973. That classification was based on gonadotropin levels and categorized these disorders into 3 groups: 1) hypogonadotropic (such as hypothalamic amenorrhea), 2) eugonadotropic (such as polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), and 3) hypergonadotropic (such as primary ovarian insufficiency). This initial classification was the subject of several subsequent iterations and modifications over the past 50 years; for example, at one point, ovulatory disorder caused by hyperprolactinemia was added as a separate fourth category. However, due to advances in endocrine assays, imaging technology, and genetics, our understanding of ovulatory disorders has expanded remarkably over the past several decades.

Previous FIGO classifications

Considering the emergent complexity of these disorders and the limitations of the original WHO classification to capture these subtleties adequately, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recently developed and published a new classification system for ovulatory disorders.5 This new system was designed using a meticulously followed Delphi process with inputs from a diverse group of national and international professional organizations, subspecialty societies, specialty journals, recognized experts in the field, and lay individuals interested in the subject matter.

Of note, FIGO had previously published classification systems for nongestational normal and abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years (FIGO AUB System 1),as well as a subsequent classification system that described potential causes of AUB symptoms (FIGO AUB System 2), with the 9 categories arranged under the acronym PALM-COEIN (Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy–Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial disorders, Iatrogenic, and Not otherwise classified). This new FIGO classification of ovulatory disorders can be viewed as a continuation of the previous initiatives and aims to further categorize the subgroup of AUB-O (AUB with ovulatory disorders). However, it is important to recognize that while most ovulatory disorders manifest with the symptoms of AUB, the absence of AUB symptoms does not necessarily preclude ovulatory disorders.

New system uses a 3-tier approach

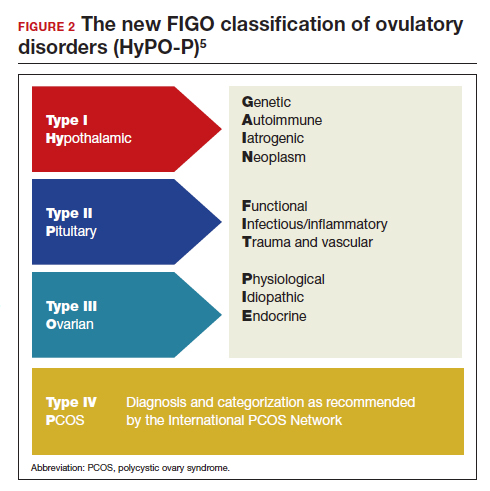

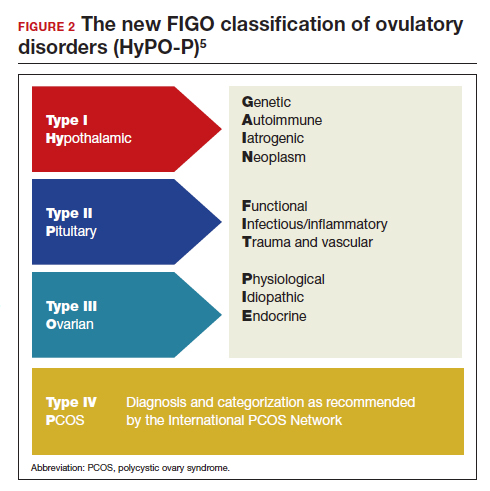

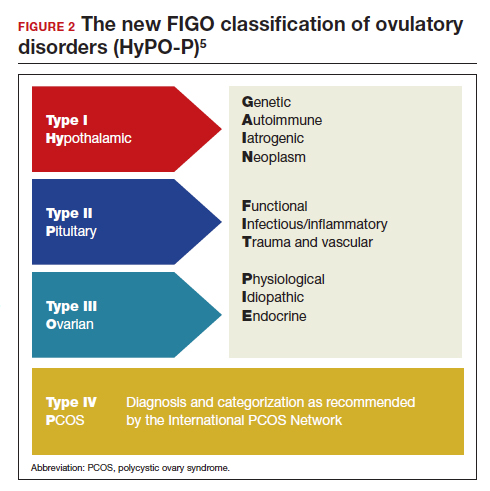

The new FIGO classification system for ovulatory disorders has adopted a 3-tier system.

The first tier is based on the anatomic components of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and is referred to with the acronym HyPO, for Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian. Recognizing that PCOS refers to a distinct spectrum of conditions that share a variable combination of signs and symptoms caused to varying degrees by different pathophysiologic mechanisms that involve inherent ovarian follicular dysfunction, neuroendocrine dysfunction, insulin resistance, and androgen excess, it is categorized in a separate class of its own in the first tier, referred to with the letter P.

Adding PCOS to the anatomical categories referred to by HyPO, the first tier is overall referred to with the acronym HyPO-P (FIGURE 2).5

The second tier of stratification provides further etiologic details for any of the primary 3 anatomic classifications of hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian. These etiologies are arranged in 10 distinct groups under the mnemonic GAIN-FIT-PIE, which stands for Genetic, Autoimmune, Iatrogenic, Neoplasm; Functional, Infectious/inflammatory, Trauma and vascular; and Physiological, Idiopathic, Endocrine.

The third tier of the system refers to the specific clinical diagnosis. For example, an individual with Kallmann syndrome would be categorized as having type I (hypothalamic), Genetic, Kallmann syndrome, and an individual with PCOS would be categorized simply as having type IV, PCOS.

Our understanding of the etiology of ovulatory disorders has substantially increased over the past several decades. This progress has prompted the need to develop a more comprehensive classification system for these disorders. FIGO recently published a 3-tier classification system for ovulatory disorders that can be remembered with 2 mnemonics: HyPO-P and GAIN-FIT-PIE.

It is hoped that widespread adoption of this new classification system results in better and more concise communication between clinicians, researchers, and patients, ultimately leading to continued improvement in our understanding of the pathophysiology and management of ovulatory disorders.

Continue to: Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A...

Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A

Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is increasingly used in many in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles in the United States. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 43.8% of embryo transfers in the United States in 2019 included at least 1 PGT-A–tested embryo.6 Despite this widespread use, however, there are still no robust clinical data for PGT-A’s efficacy and safety, and the guidelines published by the ASRM do not recommend its routine use in all IVF cycles.7 In the past 2 to 3 years, several large studies have raised questions about the reported benefit of this technology.8,9

Details of the trial

In a multicenter, controlled, noninferiority trial conducted by Yan and colleagues, 1,212 subfertile women were randomly assigned to either conventional IVF with embryo selection based on morphology or embryo selection based on PGT-A with next-generation sequencing. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of subfertility, undergoing their first IVF cycle, female age of 20 to 37, and the availability of 3 or more good-quality blastocysts.

On day 5 of embryo culture, patients with 3 or more blastocysts were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the PGT-A group or conventional IVF. All embryos were then frozen, and patients subsequently underwent frozen embryo transfer of a single blastocyst, selected based on either morphology or euploid result by PGT-A. If the initial transfer did not result in a live birth, and there were remaining transferable embryos (either a euploid embryo in the PGT-A group or a morphologically transferable embryo in the conventional IVF group), patients underwent successive frozen embryo transfers until either there was a live birth or no more embryos were available for transfer.

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative live birth rate per randomly assigned patient that resulted from up to 3 frozen embryo transfer cycles within 1 year. There were 606 patients randomly assigned to the PGT-A group and 606 randomly assigned to the conventional IVF group.

In the PGT-A group, 468 women (77.2%) had live births; in the conventional IVF group, 496 women (81.8%) had live births. Women in the PGT-A group had a lower incidence of pregnancy loss compared with the conventional IVF group: 8.7% versus 12.6% (absolute difference of -3.9%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -7.5 to -0.2). There was no difference in obstetric and neonatal outcomes between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that among women with 3 or more good-quality blastocysts, conventional IVF resulted in a cumulative live birth rate that was noninferior to that of the PGT-A group.

Some benefit shown with PGT-A

Although the study by Yan and colleagues did not show any benefit, and even a possible reduction, with regard to cumulative live birth rate for PGT-A, it did show a 4% reduction in clinical pregnancy loss when PGT-A was used. Furthermore, the study design has been criticized for performing PGT-A on only 3 blastocysts in the PGT-A group. It is quite conceivable that the PGT-A group would have had more euploid embryos available for transfer if the study design had included all the available embryos instead of only 3. On the other hand, one could argue that if the authors had extended the study to include all the available embryos, the conventional group would have also had more embryos for transfer and, therefore, more chances for pregnancy and live birth.

It is also important to recognize that only patients who had at least 3 embryos available for biopsy were included in this study, and therefore the results of this study cannot be extended to patients with fewer embryos, such as those with diminished ovarian reserve.

In summary, based on this study’s results, we may conclude that for the good-prognosis patients in the age group of 20 to 37 who have at least 3 embryos available for biopsy, PGT-A may reduce the miscarriage rate by about 4%, but this benefit comes at the expense of about a 4% reduction in the cumulative live birth rate. ●

Despite the lack of robust evidence for efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness, PGT-A has been widely adopted into clinical IVF practice in the United States over the past several years. A large randomized controlled trial has suggested that, compared with conventional IVF, PGT-A application may actually result in a slightly lower cumulative live birth rate, while the miscarriage rate may be slightly higher with conventional IVF.

PGT-A is a novel and evolving technology with the potential to improve embryo selection in IVF; however, at this juncture, there is not enough clinical data for its universal and routine use in all IVF cycles. PGT-A can potentially be more helpful in older women (>38–40) with good ovarian reserve who are likely to have a larger cohort of embryos to select from. Patients must clearly understand this technology’s pros and cons before agreeing to incorporate it into their care plan.