User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Hyperlipidemia management: A calibrated approach

An elevated serum level of cholesterol has been recognized as a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) since the publication of the Framingham Study in 1961.1 Although clinical outcomes related to ASCVD have improved in recent decades, ASCVD remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality across the globe and remains, in the United States, the leading cause of death among most racial and ethnic groups. Much of this persistent disease burden can be attributed to inadequate control of ASCVD risk factors and suboptimal implementation of prevention strategies in the general population.2

The most recent (2019) iteration of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease emphasizes a comprehensive, patient-centered, team-based approach to the management of ASCVD risk factors.2 In this article, I review how, first, medication to reduce ASCVD risk should be considered only when a patient’s risk is sufficiently high and, second, shared decision-making and social determinants of health should, in all cases, guide and inform optimal implementation of treatment.2

- Use an alternative to the Friedewald equation, such as the Martin–Hopkins equation, to estimate the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) value; order direct measurement of LDL-C; or calculate non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to assess the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in patients who have a low LDL-C or a high triglycerides level. C

- Consider the impact of ASCVD riskenhancing factors and coronary artery calcium scoring in making a recommendation to begin lipid-lowering therapy in intermediate-risk patients. C

- Add ezetimibe if a statin does not sufficiently lower LDL-C or if a patient cannot tolerate an adequate dosage of the statin. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patientoriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Estimating risk for ASCVD by ascertaining LDL-C

- The Friedewald equation. Traditionally, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is estimated using the Friedewald equationa applied to a fasting lipid profile. In patients who have a low level of LDL-C (< 70 mg/dL), however, the Friedewald equation becomes less accurate; in patients with hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 400 mg/dL),estimation of LDL-C is invalid.

- The Martin–Hopkins equation offers a validated estimation of LDL-C when the LDL-C value is < 70 mg/dL.3 This equation—in which the fixed factor of 5 used in the Friedewald equation to estimate very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is replaced by an adjustable factor that is based on the patient’s non-HDL-C (ie, TC–HDL-C) and TG values—is preferred by the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines in this clinical circumstance.4

- National Institutes of Health equation. This newer equation provides an accurate estimate of the LDL-C level in patients whose TG value is ≤ 800 mg/dL. The equation has not been fully validated for clinical use, however.5

- Direct measurement obviates the need for an equation to estimate LDL-C, but the test is not available in all health care settings.

For adults ≥ 20 years of age who are not receiving lipid-lowering therapy, a nonfasting lipid profile can be used to estimate ASCVD risk and document the baseline LDL-C level. If the TG level is ≥ 400 mg/dL, the test should be administered in the fasting state.4

- Apolipoprotein B. Alternatively, apolipoprotein B (apoB) can be measured. Because each LDL-C particle contains 1 apoB molecule, the apoB level describes the LDL-C level more accurately than a calculation of LDL-C. Many patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome have a relatively low calculated LDL-C (thereby falsely reassuring the testing clinician) but have an elevated apoB level. An apoB level ≥ 130 mg/dL corresponds to an LDL-C level >160 mg/dL.4

- Calculation of non-HDL-C. Because the nonfasting state does not have a significant impact on a patient’s TC and HDL-C levels, the non-HDL-C level also can be calculated from the results of a nonfasting lipid profile.

Non-HDL-C and apoB are equivalent predictors of ASCVD risk. These 2 assessments might offer better risk estimation than other available tools in patients who have type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.6

Continue to: Applying the estimate of 10-year ASCVD risk...

Applying the estimate of 10-year ASCVD risk

Your recommendation for preventive intervention, such as lipid-lowering therapy, should be based on the estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD. Although multiple validated risk assessment tools are available, ACC/AHA recommends the pooled cohort risk equations (PCE), introduced in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guidelines. The Framingham Heart Study now recommends the ACC/AHA PCE for risk assessment as well.7

The PCE, developed from 5 large cohorts, is based on hard atherosclerotic events: nonfatal myocardial infarction, death from coronary artery disease, and stroke. The ACC/AHA PCE is the only risk assessment tool developed using a significant percentage of patients who self-identify as Black.8 Alternatives to the ACC/AHA PCE include:

- Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) 10-year ASCVD risk calculator, which incorporates the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score.

- Reynolds Risk Score, which incorporates high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurement and a family history of premature ASCVD.9

How much does lifestyle modification actually matter?

The absolute impact of diet and exercise on lipid parameters is relatively modest. No studies have demonstrated a reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes with specific interventions regarding diet or activity.

- Diet. Nevertheless, ACC/AHA recommends that at-risk patients follow a dietary pattern that (1) emphasizes vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and (2) limits sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meat.

Saturated fat should constitute no more than 5% or 6% of total calories. In controlled-feeding trials,10 for every 1% of calories from saturated fat that are replaced with carbohydrate or monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fat, the LDL-C level was found to decline by as much as 1.8 mg/dL. Evidence is insufficient to assert that lowering dietary cholesterol reduces LDL-C.11

- Activity. Trials of aerobic physical activity, compared with a more sedentary activity pattern, have demonstrated a reduction in the LDL-C level of as much as 6 mg/dL. All adult patients should be counseled to engage in aerobic physical activity of moderate or vigorous intensity—averaging ≥ 40 minutes per session, 3 or 4 sessions per week.11

Primary prevention: Stratification by age

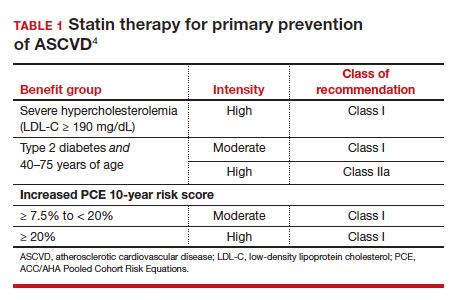

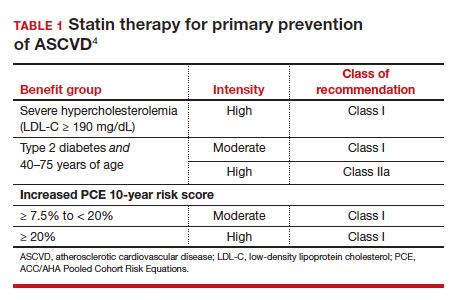

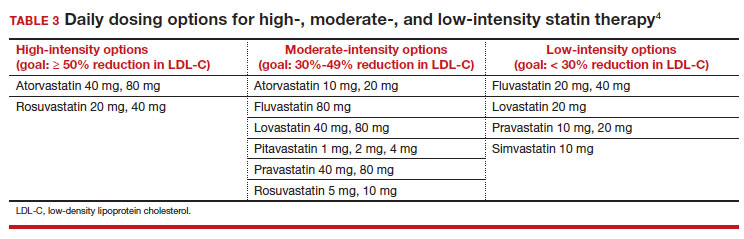

- 40 to 75 years. ACC/AHA recommends that you routinely assess traditional cardiovascular risk factors for these patients and calculate their 10-year risk for ASCVD using the PCE. Statin therapy as primary prevention is indicated for 3 major groups (TABLE 1).4 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 10%, in conjunction with 1 or more additional CVD risk factors (dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking), as the threshold for initiating low- or moderate-intensity statin therapy in this age group.12

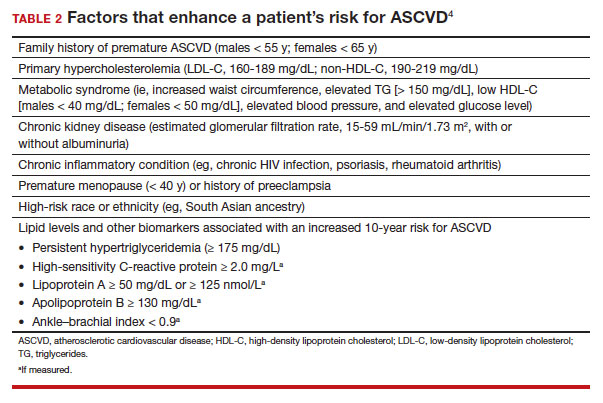

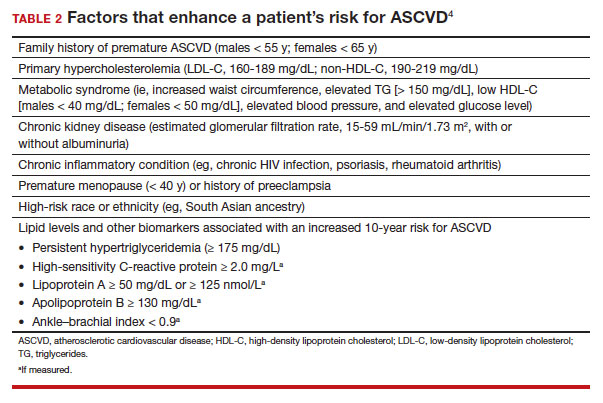

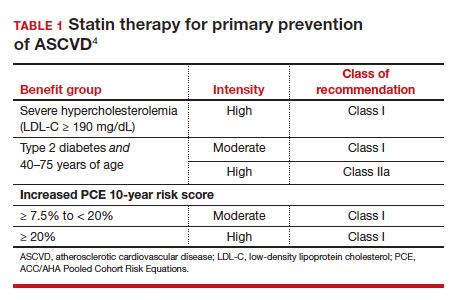

In adults at borderline risk (5% to < 7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk) or intermediate risk (≥ 7.5% to < 20% 10-year ASCVD risk), consider risk-enhancing factors to better inform your recommendation for preventive interventions. In these 2 groups, the presence of risk-enhancing factors might justify moderate-intensity statin therapy (TABLE 24).

If your decision regarding preventive intervention remains uncertain, measuring CAC might further guide your discussion with the patient.4 When the CAC score is:

- 0 Agatston units and higher-risk conditions (eg, diabetes, family history of premature coronary artery disease, smoking) are absent, statin therapy can be withheld; reassess ASCVD risk in 5 to 10 years.

- 1-99 Agatston units, statin therapy can be started, especially for patients ≥ 55 years of age.

- ≥ 100 Agatston units or ≥ 75th percentile, statin therapy is indicated for all patients, regardless of additional risk factors.4

Because statins promote progression from unstable, inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque to more stable, calcified plaque, CAC scoring is not valid in patients already on statin therapy.13

In primary prevention, patients who have been classified as having low or intermediate risk, based on ASCVD risk scoring, with a CAC score of 0 Agatston units, have an annual all-cause mortality < 1%, regardless of age and gender. Patients classified as being at high risk, based on ASCVD risk scoring, with a CAC score of 0 Agatston units, have a significantly lower annual mortality than low- or intermediate-risk patients with a CAC score > 0 Agatston units.14

- 20 to 39 years. Focus on evaluation of lifetime ASCVD risk, rather than short-term (10-year) risk. Lifestyle modification is the primary intervention for younger patients; for those with moderate hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C, 160-189 mg/dL) and a family history of premature ASCVD, however, consider statin therapy. For patients with LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL, lifetime ASCVD risk is markedly increased, and high-intensity statin therapy is recommended, regardless of age. In this group, reassess ASCVD risk factors every 4 to 6 years.4

- > 75 years, without ASCVD. In this group, the benefit of statin therapy is less clear and might be lessened by an increased potential for adverse effects. A meta-analysis of 28 trials demonstrated that people ages > 75 years had a 24% relative reduction in major coronary events for every 38.7 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C, which is comparable to the risk reduction seen in people ages 40 to 75 years.15

With increasing age, however, the relative reduction in major coronary events with statin therapy decreased,15 although other trials have not demonstrated age heterogeneity.16 Because people > 75 years of age have a significantly higher ASCVD event rate, a comparable relative rate reduction with statin therapy results in a larger absolute rate reduction (ARR) and, therefore, a smaller number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent an event, compared to the NNT in younger people.

Secondary prevention

ACC/AHA guidelines define clinical ASCVD as a history of:

- acute coronary syndrome

- myocardial infarction

- coronary or other arterial revascularization

- cerebrovascular event

- symptomatic peripheral artery disease, including aortic aneurysm.

High-intensity statin therapy is indicated for all patients ≤ 75 years who have clinical ASCVD. In patients > 75 years, consider a taper to moderate-intensity statin therapy. An upper age limit for seeing benefit from statin therapy in secondary prevention has not been identified.4

In high-risk patients, if LDL-C remains ≥ 70 mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, ezetimibe (discussed in the next section) can be added. In very-high-risk patients, if LDL-C remains ≥ 70 mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin therapy plus ezetimibe, a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor (also discussed next) can be added. Always precede initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor with a discussion of the net benefit, safety, and cost with the patient.4

Continue to: Options for lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy...

Options for lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy

- Statins (formally, hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) offer the most predictable reduction in ASCVD risk of any lipid-lowering therapy. The evidence report that accompanied the 2016 USPSTF guidelines on statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) stated that low- or moderate-dosage statin therapy is associated with approximately a 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and CVD deaths and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.17

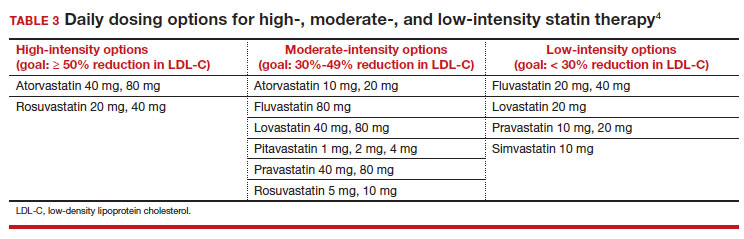

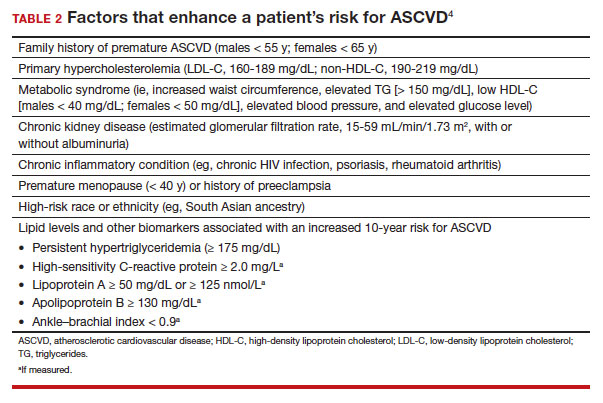

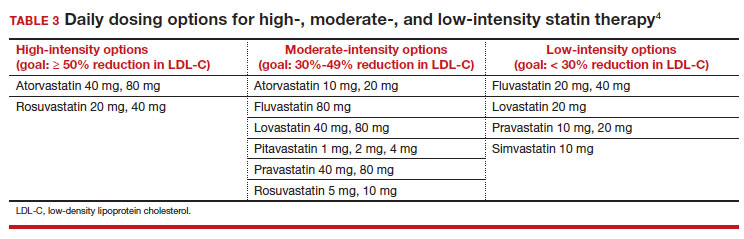

High-intensity statin therapy reduces LDL-C by ≥ 50%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy reduces LDL-C by 30% to 49% (TABLE 3).4

Statins are not without risk: A 2016 report18 estimated that treating 10,000 patients with a statin for 5 years would cause 1 case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 cases of hemorrhagic stroke. The same treatment would, however, avert approximately 1000 CVD events among patients with preexisting disease and approximately 500 CVD events among patients at elevated risk but without preexisting disease.18

- Ezetimibe, a selective cholesterol-absorption inhibitor, lowers LDL-C by 13% to 20% and typically is well tolerated. The use of ezetimibe in ASCVD risk reduction is supported by a single randomized controlled trial of more than 18,000 patients with recent acute coronary syndrome. Adding ezetimibe to simvastatin 40 mg resulted in a 2% absolute reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events over a median follow-up of 6 years (NNT = 50), compared to simvastatin alone.19 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend adding ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy in patients with clinical ASCVD who do not reach their goal LDL reduction with a statin alone. Ezetimibe also can be considered a statin alternative in patients who are statin intolerant.4

- PCSK9 inhibitors. When added to statin therapy, evolocumab and alirocumab—monoclonal antibodies that inhibit PCSK9—offer an incremental decrease in LDL-C of approximately 60%.20-22 In a meta-analysis of 35 trials evaluating the incremental benefit of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy, a significant reduction in cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction (ARR = 1.3%; NNT = 77), stroke (ARR = 0.4%; NNT = 250), and coronary revascularization (ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63) was reported. No significant difference was observed in all-cause or cardiovascular mortality.21,23

- Inclisiran, an injectable small-interfering RNA that inhibits PCSK9 synthesis, provides an incremental decrease in LDL-C of > 50% in patients already receiving statin therapy. Meta-analysis of 3 small cardiovascular outcomes trials revealed no significant difference in the rate of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality with inclisiran compared to placebo. Larger outcomes trials are underway and might offer additional insight into this agent’s role in ASCVD risk management.24

- Omega-3 fatty acids. Multiple trials have demonstrated that adding omega-3 fatty acids to usual lipid-lowering therapy does not offer a consistent reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes, despite providing a significant reduction in TG levels. In a high-risk population with persistently elevated TG despite statin therapy, icosapent ethyl, a purified eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester, reduced major ASCVD outcomes by 25% over a median 4.9 years (ARR = 4.8%; NNT = 21), and cardiovascular death by 20% (ARR = 0.9%; NNT = 111), compared with a mineral oil placebo.25 Subsequent trials, using a corn oil placebo, failed to duplicate these data26—raising concern that the mineral oil comparator might have altered results of the eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester study.27,28

- Bempedoic acid is a small-molecule inhibitor of ATP citrate lyase that increases LDL uptake by the liver. Pooled data from studies of bempedoic acid show, on average, a 15% reduction in TC, a 23% reduction in LDL-C, and a 6% increase in HDL-C, without a significant change in TG.29 In statin-intolerant patients, bempedoicacid reduced major ASCVD outcomes by 13% over a median 40 months (ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63), with no significant reduction in cardiovascular death.30

- Niacin. Two large trials failed to demonstrate improvement in major cardiovascular events or other clinical benefit when niacin is added to moderate-intensity statin therapy, despite a significant increase in the HDL-C level (on average, 6 mg/dL) and a decrease in the LDL-C level (10-12 mg/dL)and TG (42 mg/dL).31,32

- Fenofibrate lowers TG and increases HDL-C but does not consistently improve cardiovascular outcomes.33 In a trial of patients with type 2 diabetes and persistent dyslipidemia (serum TG > 204 mg/dL; HDL-C< 34 mg/dL) despite statin therapy, adding fenofibrate reduced CVD outcomes by 4.9%—although this absolute difference did not reach statistical significance.34

Neither niacin nor fenofibrate is considered useful for reducing ASCVD risk across broad populations.4

Follow-up to assess progress toward goals

Recheck the lipid profile 4 to 12 weeks after starting lipid-lowering therapy to verify adherence to medication and assess response. The primary goal is the percentage reduction in LDL-C based on ASCVD risk. An additional goal for very-high-risk patients is an LDL-C value ≤ 70 mg/dL. If the reduction in LDL-C is less than desired and adherence is assured, consider titrating the statin dosage or augmenting statin therapy with a nonstatin drug (eg, ezetimibe), or both.4 ●

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathon M. Firnhaber, MD, MAEd, MBA, East Carolina University, Family Medicine Center, 101 Heart Drive, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

- Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, et al. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease—six-year followup experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, American Geriatrics Society, American Society of Preventive Cardiology, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596-e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Elshazly MB, et al. Comparison of a novel method vs the Friedewald equation for estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels from the standard lipid profile. JAMA. 2013;310:2061-2068. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2013.280532

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/ AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/ NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-1143. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000625

- Sampson M, Ling C, Sun Q, et al. A new equation for calculation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with normolipidemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:540-548. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0013

- Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, et al. A meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:337-345. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959247

- Framingham Heart Study. Cardiovascular disease (10year risk). Accessed February 14, 2023. www.framing hamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/cardiovascular -disease-10-year-risk/

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(suppl 2):1-87. doi: 10.4158/EP171764.APPGL

- Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester ADM, et al. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a metaanalysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:11461155. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146

- Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S76-S99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:1997-2007. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.15450

- Lee S-E, Chang H-J, Sung JM, et al. Effects of statins on coronary atherosclerotic plaques: the PARADIGM study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1475-1484. doi: 10.1016/j. jcmg.2018.04.015

- Valenti V, O Hartaigh B, Heo R, et al. A 15-year warranty period for asymptomatic individuals without coronary artery calcium: a prospective follow-up of 9,715 individuals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:900-909. doi: 10.1016 /j.jcmg.2015.01.025

- Armitage J, Baigent C, Barnes E, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31942-1

- Ridker PM, Lonn E, Paynter NP, et al. Primary prevention with statin therapy in the elderly: new meta-analyses from the contemporary JUPITER and HOPE-3 randomized trials. Circulation. 2017;135:1979-1981. doi: 10.1161 /CIRCULATIONAHA. 117.028271

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008-2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629

- Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532-2561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

- Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:23732384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16951

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al; Open-Label Study of Long-Term Evaluation Against LDL Cholesterol (OSLER) Investigators. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500-1509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500858

- Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al; ODYSSEY LONG TERM Investigators. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489-1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031

- Karatasakis A, Danek BA, Karacsonyi J, et al. Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients with hypercholesterolemia: a meta‐analysis of 35 randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006910. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006910

- Khan SA, Naz A, Qamar Masood M, et al. Meta-analysis of inclisiran for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:69-73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.018

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812792

- Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, Garcia M, et al. Effect of highdose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: the STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:2268-2280. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22258

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Wolski K, et al. Association between achieved ω-3 fatty acid levels and major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with high cardiovascular risk. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1-8. doi: 10.1001 /jamacardio.2021.1157

- US Food and Drug Administration. Briefing document: Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting, November 14, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.fda.gov/media/132477/download

- Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Hernandez AV, et al. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2020;17:e1003121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003121

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Brennan D, et al; CLEAR Outcomes Investigators. Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statinintolerant patients. N Engl J Med. Published online March 4, 2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215024

- Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC, et al; HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203212. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300955

- Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, et al; AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579

- Elam MB, Ginsberg HN, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORDION Study Investigators. Association of fenofibrate therapy with long-term cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:370-380. doi: 10.1001 /jamacardio.2016.4828

- Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1563-1574. doi: 10.1056 /NEJMoa1001282

An elevated serum level of cholesterol has been recognized as a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) since the publication of the Framingham Study in 1961.1 Although clinical outcomes related to ASCVD have improved in recent decades, ASCVD remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality across the globe and remains, in the United States, the leading cause of death among most racial and ethnic groups. Much of this persistent disease burden can be attributed to inadequate control of ASCVD risk factors and suboptimal implementation of prevention strategies in the general population.2

The most recent (2019) iteration of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease emphasizes a comprehensive, patient-centered, team-based approach to the management of ASCVD risk factors.2 In this article, I review how, first, medication to reduce ASCVD risk should be considered only when a patient’s risk is sufficiently high and, second, shared decision-making and social determinants of health should, in all cases, guide and inform optimal implementation of treatment.2

- Use an alternative to the Friedewald equation, such as the Martin–Hopkins equation, to estimate the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) value; order direct measurement of LDL-C; or calculate non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to assess the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in patients who have a low LDL-C or a high triglycerides level. C

- Consider the impact of ASCVD riskenhancing factors and coronary artery calcium scoring in making a recommendation to begin lipid-lowering therapy in intermediate-risk patients. C

- Add ezetimibe if a statin does not sufficiently lower LDL-C or if a patient cannot tolerate an adequate dosage of the statin. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patientoriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Estimating risk for ASCVD by ascertaining LDL-C

- The Friedewald equation. Traditionally, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is estimated using the Friedewald equationa applied to a fasting lipid profile. In patients who have a low level of LDL-C (< 70 mg/dL), however, the Friedewald equation becomes less accurate; in patients with hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 400 mg/dL),estimation of LDL-C is invalid.

- The Martin–Hopkins equation offers a validated estimation of LDL-C when the LDL-C value is < 70 mg/dL.3 This equation—in which the fixed factor of 5 used in the Friedewald equation to estimate very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is replaced by an adjustable factor that is based on the patient’s non-HDL-C (ie, TC–HDL-C) and TG values—is preferred by the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines in this clinical circumstance.4

- National Institutes of Health equation. This newer equation provides an accurate estimate of the LDL-C level in patients whose TG value is ≤ 800 mg/dL. The equation has not been fully validated for clinical use, however.5

- Direct measurement obviates the need for an equation to estimate LDL-C, but the test is not available in all health care settings.

For adults ≥ 20 years of age who are not receiving lipid-lowering therapy, a nonfasting lipid profile can be used to estimate ASCVD risk and document the baseline LDL-C level. If the TG level is ≥ 400 mg/dL, the test should be administered in the fasting state.4

- Apolipoprotein B. Alternatively, apolipoprotein B (apoB) can be measured. Because each LDL-C particle contains 1 apoB molecule, the apoB level describes the LDL-C level more accurately than a calculation of LDL-C. Many patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome have a relatively low calculated LDL-C (thereby falsely reassuring the testing clinician) but have an elevated apoB level. An apoB level ≥ 130 mg/dL corresponds to an LDL-C level >160 mg/dL.4

- Calculation of non-HDL-C. Because the nonfasting state does not have a significant impact on a patient’s TC and HDL-C levels, the non-HDL-C level also can be calculated from the results of a nonfasting lipid profile.

Non-HDL-C and apoB are equivalent predictors of ASCVD risk. These 2 assessments might offer better risk estimation than other available tools in patients who have type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.6

Continue to: Applying the estimate of 10-year ASCVD risk...

Applying the estimate of 10-year ASCVD risk

Your recommendation for preventive intervention, such as lipid-lowering therapy, should be based on the estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD. Although multiple validated risk assessment tools are available, ACC/AHA recommends the pooled cohort risk equations (PCE), introduced in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guidelines. The Framingham Heart Study now recommends the ACC/AHA PCE for risk assessment as well.7

The PCE, developed from 5 large cohorts, is based on hard atherosclerotic events: nonfatal myocardial infarction, death from coronary artery disease, and stroke. The ACC/AHA PCE is the only risk assessment tool developed using a significant percentage of patients who self-identify as Black.8 Alternatives to the ACC/AHA PCE include:

- Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) 10-year ASCVD risk calculator, which incorporates the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score.

- Reynolds Risk Score, which incorporates high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurement and a family history of premature ASCVD.9

How much does lifestyle modification actually matter?

The absolute impact of diet and exercise on lipid parameters is relatively modest. No studies have demonstrated a reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes with specific interventions regarding diet or activity.

- Diet. Nevertheless, ACC/AHA recommends that at-risk patients follow a dietary pattern that (1) emphasizes vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and (2) limits sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meat.

Saturated fat should constitute no more than 5% or 6% of total calories. In controlled-feeding trials,10 for every 1% of calories from saturated fat that are replaced with carbohydrate or monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fat, the LDL-C level was found to decline by as much as 1.8 mg/dL. Evidence is insufficient to assert that lowering dietary cholesterol reduces LDL-C.11

- Activity. Trials of aerobic physical activity, compared with a more sedentary activity pattern, have demonstrated a reduction in the LDL-C level of as much as 6 mg/dL. All adult patients should be counseled to engage in aerobic physical activity of moderate or vigorous intensity—averaging ≥ 40 minutes per session, 3 or 4 sessions per week.11

Primary prevention: Stratification by age

- 40 to 75 years. ACC/AHA recommends that you routinely assess traditional cardiovascular risk factors for these patients and calculate their 10-year risk for ASCVD using the PCE. Statin therapy as primary prevention is indicated for 3 major groups (TABLE 1).4 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 10%, in conjunction with 1 or more additional CVD risk factors (dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking), as the threshold for initiating low- or moderate-intensity statin therapy in this age group.12

In adults at borderline risk (5% to < 7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk) or intermediate risk (≥ 7.5% to < 20% 10-year ASCVD risk), consider risk-enhancing factors to better inform your recommendation for preventive interventions. In these 2 groups, the presence of risk-enhancing factors might justify moderate-intensity statin therapy (TABLE 24).

If your decision regarding preventive intervention remains uncertain, measuring CAC might further guide your discussion with the patient.4 When the CAC score is:

- 0 Agatston units and higher-risk conditions (eg, diabetes, family history of premature coronary artery disease, smoking) are absent, statin therapy can be withheld; reassess ASCVD risk in 5 to 10 years.

- 1-99 Agatston units, statin therapy can be started, especially for patients ≥ 55 years of age.

- ≥ 100 Agatston units or ≥ 75th percentile, statin therapy is indicated for all patients, regardless of additional risk factors.4

Because statins promote progression from unstable, inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque to more stable, calcified plaque, CAC scoring is not valid in patients already on statin therapy.13

In primary prevention, patients who have been classified as having low or intermediate risk, based on ASCVD risk scoring, with a CAC score of 0 Agatston units, have an annual all-cause mortality < 1%, regardless of age and gender. Patients classified as being at high risk, based on ASCVD risk scoring, with a CAC score of 0 Agatston units, have a significantly lower annual mortality than low- or intermediate-risk patients with a CAC score > 0 Agatston units.14

- 20 to 39 years. Focus on evaluation of lifetime ASCVD risk, rather than short-term (10-year) risk. Lifestyle modification is the primary intervention for younger patients; for those with moderate hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C, 160-189 mg/dL) and a family history of premature ASCVD, however, consider statin therapy. For patients with LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL, lifetime ASCVD risk is markedly increased, and high-intensity statin therapy is recommended, regardless of age. In this group, reassess ASCVD risk factors every 4 to 6 years.4

- > 75 years, without ASCVD. In this group, the benefit of statin therapy is less clear and might be lessened by an increased potential for adverse effects. A meta-analysis of 28 trials demonstrated that people ages > 75 years had a 24% relative reduction in major coronary events for every 38.7 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C, which is comparable to the risk reduction seen in people ages 40 to 75 years.15

With increasing age, however, the relative reduction in major coronary events with statin therapy decreased,15 although other trials have not demonstrated age heterogeneity.16 Because people > 75 years of age have a significantly higher ASCVD event rate, a comparable relative rate reduction with statin therapy results in a larger absolute rate reduction (ARR) and, therefore, a smaller number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent an event, compared to the NNT in younger people.

Secondary prevention

ACC/AHA guidelines define clinical ASCVD as a history of:

- acute coronary syndrome

- myocardial infarction

- coronary or other arterial revascularization

- cerebrovascular event

- symptomatic peripheral artery disease, including aortic aneurysm.

High-intensity statin therapy is indicated for all patients ≤ 75 years who have clinical ASCVD. In patients > 75 years, consider a taper to moderate-intensity statin therapy. An upper age limit for seeing benefit from statin therapy in secondary prevention has not been identified.4

In high-risk patients, if LDL-C remains ≥ 70 mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, ezetimibe (discussed in the next section) can be added. In very-high-risk patients, if LDL-C remains ≥ 70 mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin therapy plus ezetimibe, a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor (also discussed next) can be added. Always precede initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor with a discussion of the net benefit, safety, and cost with the patient.4

Continue to: Options for lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy...

Options for lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy

- Statins (formally, hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) offer the most predictable reduction in ASCVD risk of any lipid-lowering therapy. The evidence report that accompanied the 2016 USPSTF guidelines on statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) stated that low- or moderate-dosage statin therapy is associated with approximately a 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and CVD deaths and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.17

High-intensity statin therapy reduces LDL-C by ≥ 50%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy reduces LDL-C by 30% to 49% (TABLE 3).4

Statins are not without risk: A 2016 report18 estimated that treating 10,000 patients with a statin for 5 years would cause 1 case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 cases of hemorrhagic stroke. The same treatment would, however, avert approximately 1000 CVD events among patients with preexisting disease and approximately 500 CVD events among patients at elevated risk but without preexisting disease.18

- Ezetimibe, a selective cholesterol-absorption inhibitor, lowers LDL-C by 13% to 20% and typically is well tolerated. The use of ezetimibe in ASCVD risk reduction is supported by a single randomized controlled trial of more than 18,000 patients with recent acute coronary syndrome. Adding ezetimibe to simvastatin 40 mg resulted in a 2% absolute reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events over a median follow-up of 6 years (NNT = 50), compared to simvastatin alone.19 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend adding ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy in patients with clinical ASCVD who do not reach their goal LDL reduction with a statin alone. Ezetimibe also can be considered a statin alternative in patients who are statin intolerant.4

- PCSK9 inhibitors. When added to statin therapy, evolocumab and alirocumab—monoclonal antibodies that inhibit PCSK9—offer an incremental decrease in LDL-C of approximately 60%.20-22 In a meta-analysis of 35 trials evaluating the incremental benefit of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy, a significant reduction in cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction (ARR = 1.3%; NNT = 77), stroke (ARR = 0.4%; NNT = 250), and coronary revascularization (ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63) was reported. No significant difference was observed in all-cause or cardiovascular mortality.21,23

- Inclisiran, an injectable small-interfering RNA that inhibits PCSK9 synthesis, provides an incremental decrease in LDL-C of > 50% in patients already receiving statin therapy. Meta-analysis of 3 small cardiovascular outcomes trials revealed no significant difference in the rate of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality with inclisiran compared to placebo. Larger outcomes trials are underway and might offer additional insight into this agent’s role in ASCVD risk management.24

- Omega-3 fatty acids. Multiple trials have demonstrated that adding omega-3 fatty acids to usual lipid-lowering therapy does not offer a consistent reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes, despite providing a significant reduction in TG levels. In a high-risk population with persistently elevated TG despite statin therapy, icosapent ethyl, a purified eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester, reduced major ASCVD outcomes by 25% over a median 4.9 years (ARR = 4.8%; NNT = 21), and cardiovascular death by 20% (ARR = 0.9%; NNT = 111), compared with a mineral oil placebo.25 Subsequent trials, using a corn oil placebo, failed to duplicate these data26—raising concern that the mineral oil comparator might have altered results of the eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester study.27,28

- Bempedoic acid is a small-molecule inhibitor of ATP citrate lyase that increases LDL uptake by the liver. Pooled data from studies of bempedoic acid show, on average, a 15% reduction in TC, a 23% reduction in LDL-C, and a 6% increase in HDL-C, without a significant change in TG.29 In statin-intolerant patients, bempedoicacid reduced major ASCVD outcomes by 13% over a median 40 months (ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63), with no significant reduction in cardiovascular death.30

- Niacin. Two large trials failed to demonstrate improvement in major cardiovascular events or other clinical benefit when niacin is added to moderate-intensity statin therapy, despite a significant increase in the HDL-C level (on average, 6 mg/dL) and a decrease in the LDL-C level (10-12 mg/dL)and TG (42 mg/dL).31,32

- Fenofibrate lowers TG and increases HDL-C but does not consistently improve cardiovascular outcomes.33 In a trial of patients with type 2 diabetes and persistent dyslipidemia (serum TG > 204 mg/dL; HDL-C< 34 mg/dL) despite statin therapy, adding fenofibrate reduced CVD outcomes by 4.9%—although this absolute difference did not reach statistical significance.34

Neither niacin nor fenofibrate is considered useful for reducing ASCVD risk across broad populations.4

Follow-up to assess progress toward goals

Recheck the lipid profile 4 to 12 weeks after starting lipid-lowering therapy to verify adherence to medication and assess response. The primary goal is the percentage reduction in LDL-C based on ASCVD risk. An additional goal for very-high-risk patients is an LDL-C value ≤ 70 mg/dL. If the reduction in LDL-C is less than desired and adherence is assured, consider titrating the statin dosage or augmenting statin therapy with a nonstatin drug (eg, ezetimibe), or both.4 ●

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathon M. Firnhaber, MD, MAEd, MBA, East Carolina University, Family Medicine Center, 101 Heart Drive, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

An elevated serum level of cholesterol has been recognized as a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) since the publication of the Framingham Study in 1961.1 Although clinical outcomes related to ASCVD have improved in recent decades, ASCVD remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality across the globe and remains, in the United States, the leading cause of death among most racial and ethnic groups. Much of this persistent disease burden can be attributed to inadequate control of ASCVD risk factors and suboptimal implementation of prevention strategies in the general population.2

The most recent (2019) iteration of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease emphasizes a comprehensive, patient-centered, team-based approach to the management of ASCVD risk factors.2 In this article, I review how, first, medication to reduce ASCVD risk should be considered only when a patient’s risk is sufficiently high and, second, shared decision-making and social determinants of health should, in all cases, guide and inform optimal implementation of treatment.2

- Use an alternative to the Friedewald equation, such as the Martin–Hopkins equation, to estimate the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) value; order direct measurement of LDL-C; or calculate non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to assess the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in patients who have a low LDL-C or a high triglycerides level. C

- Consider the impact of ASCVD riskenhancing factors and coronary artery calcium scoring in making a recommendation to begin lipid-lowering therapy in intermediate-risk patients. C

- Add ezetimibe if a statin does not sufficiently lower LDL-C or if a patient cannot tolerate an adequate dosage of the statin. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A. Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B. Inconsistent or limited-quality patientoriented evidence

C. Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Estimating risk for ASCVD by ascertaining LDL-C

- The Friedewald equation. Traditionally, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is estimated using the Friedewald equationa applied to a fasting lipid profile. In patients who have a low level of LDL-C (< 70 mg/dL), however, the Friedewald equation becomes less accurate; in patients with hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 400 mg/dL),estimation of LDL-C is invalid.

- The Martin–Hopkins equation offers a validated estimation of LDL-C when the LDL-C value is < 70 mg/dL.3 This equation—in which the fixed factor of 5 used in the Friedewald equation to estimate very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is replaced by an adjustable factor that is based on the patient’s non-HDL-C (ie, TC–HDL-C) and TG values—is preferred by the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines in this clinical circumstance.4

- National Institutes of Health equation. This newer equation provides an accurate estimate of the LDL-C level in patients whose TG value is ≤ 800 mg/dL. The equation has not been fully validated for clinical use, however.5

- Direct measurement obviates the need for an equation to estimate LDL-C, but the test is not available in all health care settings.

For adults ≥ 20 years of age who are not receiving lipid-lowering therapy, a nonfasting lipid profile can be used to estimate ASCVD risk and document the baseline LDL-C level. If the TG level is ≥ 400 mg/dL, the test should be administered in the fasting state.4

- Apolipoprotein B. Alternatively, apolipoprotein B (apoB) can be measured. Because each LDL-C particle contains 1 apoB molecule, the apoB level describes the LDL-C level more accurately than a calculation of LDL-C. Many patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome have a relatively low calculated LDL-C (thereby falsely reassuring the testing clinician) but have an elevated apoB level. An apoB level ≥ 130 mg/dL corresponds to an LDL-C level >160 mg/dL.4

- Calculation of non-HDL-C. Because the nonfasting state does not have a significant impact on a patient’s TC and HDL-C levels, the non-HDL-C level also can be calculated from the results of a nonfasting lipid profile.

Non-HDL-C and apoB are equivalent predictors of ASCVD risk. These 2 assessments might offer better risk estimation than other available tools in patients who have type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.6

Continue to: Applying the estimate of 10-year ASCVD risk...

Applying the estimate of 10-year ASCVD risk

Your recommendation for preventive intervention, such as lipid-lowering therapy, should be based on the estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD. Although multiple validated risk assessment tools are available, ACC/AHA recommends the pooled cohort risk equations (PCE), introduced in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guidelines. The Framingham Heart Study now recommends the ACC/AHA PCE for risk assessment as well.7

The PCE, developed from 5 large cohorts, is based on hard atherosclerotic events: nonfatal myocardial infarction, death from coronary artery disease, and stroke. The ACC/AHA PCE is the only risk assessment tool developed using a significant percentage of patients who self-identify as Black.8 Alternatives to the ACC/AHA PCE include:

- Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) 10-year ASCVD risk calculator, which incorporates the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score.

- Reynolds Risk Score, which incorporates high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurement and a family history of premature ASCVD.9

How much does lifestyle modification actually matter?

The absolute impact of diet and exercise on lipid parameters is relatively modest. No studies have demonstrated a reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes with specific interventions regarding diet or activity.

- Diet. Nevertheless, ACC/AHA recommends that at-risk patients follow a dietary pattern that (1) emphasizes vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and (2) limits sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meat.

Saturated fat should constitute no more than 5% or 6% of total calories. In controlled-feeding trials,10 for every 1% of calories from saturated fat that are replaced with carbohydrate or monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fat, the LDL-C level was found to decline by as much as 1.8 mg/dL. Evidence is insufficient to assert that lowering dietary cholesterol reduces LDL-C.11

- Activity. Trials of aerobic physical activity, compared with a more sedentary activity pattern, have demonstrated a reduction in the LDL-C level of as much as 6 mg/dL. All adult patients should be counseled to engage in aerobic physical activity of moderate or vigorous intensity—averaging ≥ 40 minutes per session, 3 or 4 sessions per week.11

Primary prevention: Stratification by age

- 40 to 75 years. ACC/AHA recommends that you routinely assess traditional cardiovascular risk factors for these patients and calculate their 10-year risk for ASCVD using the PCE. Statin therapy as primary prevention is indicated for 3 major groups (TABLE 1).4 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 10%, in conjunction with 1 or more additional CVD risk factors (dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking), as the threshold for initiating low- or moderate-intensity statin therapy in this age group.12

In adults at borderline risk (5% to < 7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk) or intermediate risk (≥ 7.5% to < 20% 10-year ASCVD risk), consider risk-enhancing factors to better inform your recommendation for preventive interventions. In these 2 groups, the presence of risk-enhancing factors might justify moderate-intensity statin therapy (TABLE 24).

If your decision regarding preventive intervention remains uncertain, measuring CAC might further guide your discussion with the patient.4 When the CAC score is:

- 0 Agatston units and higher-risk conditions (eg, diabetes, family history of premature coronary artery disease, smoking) are absent, statin therapy can be withheld; reassess ASCVD risk in 5 to 10 years.

- 1-99 Agatston units, statin therapy can be started, especially for patients ≥ 55 years of age.

- ≥ 100 Agatston units or ≥ 75th percentile, statin therapy is indicated for all patients, regardless of additional risk factors.4

Because statins promote progression from unstable, inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque to more stable, calcified plaque, CAC scoring is not valid in patients already on statin therapy.13

In primary prevention, patients who have been classified as having low or intermediate risk, based on ASCVD risk scoring, with a CAC score of 0 Agatston units, have an annual all-cause mortality < 1%, regardless of age and gender. Patients classified as being at high risk, based on ASCVD risk scoring, with a CAC score of 0 Agatston units, have a significantly lower annual mortality than low- or intermediate-risk patients with a CAC score > 0 Agatston units.14

- 20 to 39 years. Focus on evaluation of lifetime ASCVD risk, rather than short-term (10-year) risk. Lifestyle modification is the primary intervention for younger patients; for those with moderate hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C, 160-189 mg/dL) and a family history of premature ASCVD, however, consider statin therapy. For patients with LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL, lifetime ASCVD risk is markedly increased, and high-intensity statin therapy is recommended, regardless of age. In this group, reassess ASCVD risk factors every 4 to 6 years.4

- > 75 years, without ASCVD. In this group, the benefit of statin therapy is less clear and might be lessened by an increased potential for adverse effects. A meta-analysis of 28 trials demonstrated that people ages > 75 years had a 24% relative reduction in major coronary events for every 38.7 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C, which is comparable to the risk reduction seen in people ages 40 to 75 years.15

With increasing age, however, the relative reduction in major coronary events with statin therapy decreased,15 although other trials have not demonstrated age heterogeneity.16 Because people > 75 years of age have a significantly higher ASCVD event rate, a comparable relative rate reduction with statin therapy results in a larger absolute rate reduction (ARR) and, therefore, a smaller number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent an event, compared to the NNT in younger people.

Secondary prevention

ACC/AHA guidelines define clinical ASCVD as a history of:

- acute coronary syndrome

- myocardial infarction

- coronary or other arterial revascularization

- cerebrovascular event

- symptomatic peripheral artery disease, including aortic aneurysm.

High-intensity statin therapy is indicated for all patients ≤ 75 years who have clinical ASCVD. In patients > 75 years, consider a taper to moderate-intensity statin therapy. An upper age limit for seeing benefit from statin therapy in secondary prevention has not been identified.4

In high-risk patients, if LDL-C remains ≥ 70 mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, ezetimibe (discussed in the next section) can be added. In very-high-risk patients, if LDL-C remains ≥ 70 mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin therapy plus ezetimibe, a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor (also discussed next) can be added. Always precede initiation of a PCSK9 inhibitor with a discussion of the net benefit, safety, and cost with the patient.4

Continue to: Options for lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy...

Options for lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy

- Statins (formally, hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) offer the most predictable reduction in ASCVD risk of any lipid-lowering therapy. The evidence report that accompanied the 2016 USPSTF guidelines on statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) stated that low- or moderate-dosage statin therapy is associated with approximately a 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and CVD deaths and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.17

High-intensity statin therapy reduces LDL-C by ≥ 50%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy reduces LDL-C by 30% to 49% (TABLE 3).4

Statins are not without risk: A 2016 report18 estimated that treating 10,000 patients with a statin for 5 years would cause 1 case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 cases of hemorrhagic stroke. The same treatment would, however, avert approximately 1000 CVD events among patients with preexisting disease and approximately 500 CVD events among patients at elevated risk but without preexisting disease.18

- Ezetimibe, a selective cholesterol-absorption inhibitor, lowers LDL-C by 13% to 20% and typically is well tolerated. The use of ezetimibe in ASCVD risk reduction is supported by a single randomized controlled trial of more than 18,000 patients with recent acute coronary syndrome. Adding ezetimibe to simvastatin 40 mg resulted in a 2% absolute reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events over a median follow-up of 6 years (NNT = 50), compared to simvastatin alone.19 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend adding ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy in patients with clinical ASCVD who do not reach their goal LDL reduction with a statin alone. Ezetimibe also can be considered a statin alternative in patients who are statin intolerant.4

- PCSK9 inhibitors. When added to statin therapy, evolocumab and alirocumab—monoclonal antibodies that inhibit PCSK9—offer an incremental decrease in LDL-C of approximately 60%.20-22 In a meta-analysis of 35 trials evaluating the incremental benefit of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy, a significant reduction in cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction (ARR = 1.3%; NNT = 77), stroke (ARR = 0.4%; NNT = 250), and coronary revascularization (ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63) was reported. No significant difference was observed in all-cause or cardiovascular mortality.21,23

- Inclisiran, an injectable small-interfering RNA that inhibits PCSK9 synthesis, provides an incremental decrease in LDL-C of > 50% in patients already receiving statin therapy. Meta-analysis of 3 small cardiovascular outcomes trials revealed no significant difference in the rate of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality with inclisiran compared to placebo. Larger outcomes trials are underway and might offer additional insight into this agent’s role in ASCVD risk management.24

- Omega-3 fatty acids. Multiple trials have demonstrated that adding omega-3 fatty acids to usual lipid-lowering therapy does not offer a consistent reduction in adverse cardiovascular outcomes, despite providing a significant reduction in TG levels. In a high-risk population with persistently elevated TG despite statin therapy, icosapent ethyl, a purified eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester, reduced major ASCVD outcomes by 25% over a median 4.9 years (ARR = 4.8%; NNT = 21), and cardiovascular death by 20% (ARR = 0.9%; NNT = 111), compared with a mineral oil placebo.25 Subsequent trials, using a corn oil placebo, failed to duplicate these data26—raising concern that the mineral oil comparator might have altered results of the eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester study.27,28

- Bempedoic acid is a small-molecule inhibitor of ATP citrate lyase that increases LDL uptake by the liver. Pooled data from studies of bempedoic acid show, on average, a 15% reduction in TC, a 23% reduction in LDL-C, and a 6% increase in HDL-C, without a significant change in TG.29 In statin-intolerant patients, bempedoicacid reduced major ASCVD outcomes by 13% over a median 40 months (ARR = 1.6%; NNT = 63), with no significant reduction in cardiovascular death.30

- Niacin. Two large trials failed to demonstrate improvement in major cardiovascular events or other clinical benefit when niacin is added to moderate-intensity statin therapy, despite a significant increase in the HDL-C level (on average, 6 mg/dL) and a decrease in the LDL-C level (10-12 mg/dL)and TG (42 mg/dL).31,32

- Fenofibrate lowers TG and increases HDL-C but does not consistently improve cardiovascular outcomes.33 In a trial of patients with type 2 diabetes and persistent dyslipidemia (serum TG > 204 mg/dL; HDL-C< 34 mg/dL) despite statin therapy, adding fenofibrate reduced CVD outcomes by 4.9%—although this absolute difference did not reach statistical significance.34

Neither niacin nor fenofibrate is considered useful for reducing ASCVD risk across broad populations.4

Follow-up to assess progress toward goals

Recheck the lipid profile 4 to 12 weeks after starting lipid-lowering therapy to verify adherence to medication and assess response. The primary goal is the percentage reduction in LDL-C based on ASCVD risk. An additional goal for very-high-risk patients is an LDL-C value ≤ 70 mg/dL. If the reduction in LDL-C is less than desired and adherence is assured, consider titrating the statin dosage or augmenting statin therapy with a nonstatin drug (eg, ezetimibe), or both.4 ●

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathon M. Firnhaber, MD, MAEd, MBA, East Carolina University, Family Medicine Center, 101 Heart Drive, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

- Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, et al. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease—six-year followup experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, American Geriatrics Society, American Society of Preventive Cardiology, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596-e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Elshazly MB, et al. Comparison of a novel method vs the Friedewald equation for estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels from the standard lipid profile. JAMA. 2013;310:2061-2068. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2013.280532

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/ AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/ NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-1143. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000625

- Sampson M, Ling C, Sun Q, et al. A new equation for calculation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with normolipidemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:540-548. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0013

- Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, et al. A meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:337-345. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959247

- Framingham Heart Study. Cardiovascular disease (10year risk). Accessed February 14, 2023. www.framing hamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/cardiovascular -disease-10-year-risk/

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(suppl 2):1-87. doi: 10.4158/EP171764.APPGL

- Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester ADM, et al. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a metaanalysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:11461155. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146

- Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S76-S99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:1997-2007. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.15450

- Lee S-E, Chang H-J, Sung JM, et al. Effects of statins on coronary atherosclerotic plaques: the PARADIGM study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1475-1484. doi: 10.1016/j. jcmg.2018.04.015

- Valenti V, O Hartaigh B, Heo R, et al. A 15-year warranty period for asymptomatic individuals without coronary artery calcium: a prospective follow-up of 9,715 individuals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:900-909. doi: 10.1016 /j.jcmg.2015.01.025

- Armitage J, Baigent C, Barnes E, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31942-1

- Ridker PM, Lonn E, Paynter NP, et al. Primary prevention with statin therapy in the elderly: new meta-analyses from the contemporary JUPITER and HOPE-3 randomized trials. Circulation. 2017;135:1979-1981. doi: 10.1161 /CIRCULATIONAHA. 117.028271

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008-2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629

- Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532-2561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

- Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:23732384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16951

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al; Open-Label Study of Long-Term Evaluation Against LDL Cholesterol (OSLER) Investigators. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500-1509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500858

- Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al; ODYSSEY LONG TERM Investigators. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489-1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031

- Karatasakis A, Danek BA, Karacsonyi J, et al. Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients with hypercholesterolemia: a meta‐analysis of 35 randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006910. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006910

- Khan SA, Naz A, Qamar Masood M, et al. Meta-analysis of inclisiran for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:69-73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.018

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812792

- Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, Garcia M, et al. Effect of highdose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: the STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:2268-2280. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22258

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Wolski K, et al. Association between achieved ω-3 fatty acid levels and major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with high cardiovascular risk. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1-8. doi: 10.1001 /jamacardio.2021.1157

- US Food and Drug Administration. Briefing document: Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting, November 14, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.fda.gov/media/132477/download

- Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Hernandez AV, et al. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2020;17:e1003121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003121

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Brennan D, et al; CLEAR Outcomes Investigators. Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statinintolerant patients. N Engl J Med. Published online March 4, 2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215024

- Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC, et al; HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203212. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300955

- Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, et al; AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579

- Elam MB, Ginsberg HN, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORDION Study Investigators. Association of fenofibrate therapy with long-term cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:370-380. doi: 10.1001 /jamacardio.2016.4828

- Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1563-1574. doi: 10.1056 /NEJMoa1001282

- Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, et al. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease—six-year followup experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, American Geriatrics Society, American Society of Preventive Cardiology, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596-e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Elshazly MB, et al. Comparison of a novel method vs the Friedewald equation for estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels from the standard lipid profile. JAMA. 2013;310:2061-2068. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2013.280532

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/ AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/ NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-1143. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000625

- Sampson M, Ling C, Sun Q, et al. A new equation for calculation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with normolipidemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:540-548. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0013

- Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, et al. A meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:337-345. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959247

- Framingham Heart Study. Cardiovascular disease (10year risk). Accessed February 14, 2023. www.framing hamheartstudy.org/fhs-risk-functions/cardiovascular -disease-10-year-risk/

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(suppl 2):1-87. doi: 10.4158/EP171764.APPGL

- Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester ADM, et al. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a metaanalysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:11461155. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146

- Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S76-S99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:1997-2007. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.15450

- Lee S-E, Chang H-J, Sung JM, et al. Effects of statins on coronary atherosclerotic plaques: the PARADIGM study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1475-1484. doi: 10.1016/j. jcmg.2018.04.015

- Valenti V, O Hartaigh B, Heo R, et al. A 15-year warranty period for asymptomatic individuals without coronary artery calcium: a prospective follow-up of 9,715 individuals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:900-909. doi: 10.1016 /j.jcmg.2015.01.025

- Armitage J, Baigent C, Barnes E, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407415. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31942-1

- Ridker PM, Lonn E, Paynter NP, et al. Primary prevention with statin therapy in the elderly: new meta-analyses from the contemporary JUPITER and HOPE-3 randomized trials. Circulation. 2017;135:1979-1981. doi: 10.1161 /CIRCULATIONAHA. 117.028271

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008-2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629

- Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532-2561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

- Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:23732384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16951

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al; Open-Label Study of Long-Term Evaluation Against LDL Cholesterol (OSLER) Investigators. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500-1509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500858

- Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al; ODYSSEY LONG TERM Investigators. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489-1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501031

- Karatasakis A, Danek BA, Karacsonyi J, et al. Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients with hypercholesterolemia: a meta‐analysis of 35 randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006910. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006910

- Khan SA, Naz A, Qamar Masood M, et al. Meta-analysis of inclisiran for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:69-73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.018

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812792

- Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, Garcia M, et al. Effect of highdose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: the STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:2268-2280. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22258

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Wolski K, et al. Association between achieved ω-3 fatty acid levels and major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with high cardiovascular risk. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1-8. doi: 10.1001 /jamacardio.2021.1157

- US Food and Drug Administration. Briefing document: Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting, November 14, 2019. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.fda.gov/media/132477/download

- Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Hernandez AV, et al. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2020;17:e1003121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003121

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Brennan D, et al; CLEAR Outcomes Investigators. Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statinintolerant patients. N Engl J Med. Published online March 4, 2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215024

- Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC, et al; HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203212. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300955

- Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, et al; AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579

- Elam MB, Ginsberg HN, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORDION Study Investigators. Association of fenofibrate therapy with long-term cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:370-380. doi: 10.1001 /jamacardio.2016.4828

- Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1563-1574. doi: 10.1056 /NEJMoa1001282

First prospective study finds pregnancies with Sjögren’s to be largely safe

Women with Sjögren’s syndrome have pregnancy outcomes similar to those of the general population, according to the first study to prospectively track pregnancy outcomes among people with the autoimmune condition.

“Most early studies of pregnancy in rheumatic disease patients were retrospective and included only small numbers, making it difficult to know how generalizable the reported results were,” said Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a rheumatologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, in an email interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the research.