User login

Other Pediatric Literature of Interest

1. Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, et al. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:499-502.

Kawasaki disease, a systemic vasculitis of childhood, is the most common cause of childhood acquired heart disease in developed countries and frequently a diagnosis made in the inpatient setting. Although the etiology of Kawasaki disease is not known, there is evidence to suggest the disease may be triggered by an infectious agent. This evidence includes wavelike spread in countries, seasonal epidemics, and the rarity of Kawasaki disease in adults and infants less than 3 months old. Even more compelling is the recent identification by Rowley et al. Of an antigen of unknown origin in respiratory epithelial cells and macrophages from children with Kawasaki disease (1).

Despite suggestion that retroviruses, Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, or chlamydia may be important in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease, no infectious etiology has been proven. In this brief report, Esper et al. document the interesting finding of a novel human coronavirus, “New Haven coronavirus” (HCoVNH), in the respiratory secretions of a 6-month old infant diagnosed with Kawasaki disease. Subsequently, the authors performed a retrospective, case-controlled study of 11 Kawasaki disease patients less than 5 years of age from whom respiratory secretions were archived but had tested negative for respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1–3, and adenovirus by direct fluorescent antibody assay. These patients were matched with 2 control subjects. Eight (72.7%) of 11 case subjects and 1 (4.5%) of the 22 control subjects tested positive for HCoVNH by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (p=.0015). Further studies are needed to determine the precise role this, or other infectious pathogens, may have in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Reference

- Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. Detection of antigen in bronchial epithelium and macrophages in acute Kawasaki disease by use of synthetic antibody. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:856-65.

2. Eyaid WM, AlNouri DM, Rashed MS, et al. An inborn error of metabolism presenting as hypoxicischemic insult. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:134-6.

Inborn error of metabolism is frequently on the “bottom” of many differential diagnoses lists for common pediatric presenting complaints. Relative infrequency coupled with the occasional difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis presents unique challenges. Nonetheless, the importance of making this diagnosis is essential, given the frequent opportunity for pharmacologic and/ or dietary intervention to be therapeutic.

These authors present an interesting case of siblings presenting with seizures and central nervous system imaging consistent with hypoxicischemic insult who were subsequently diagnosed with isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency.

1. Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, et al. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:499-502.

Kawasaki disease, a systemic vasculitis of childhood, is the most common cause of childhood acquired heart disease in developed countries and frequently a diagnosis made in the inpatient setting. Although the etiology of Kawasaki disease is not known, there is evidence to suggest the disease may be triggered by an infectious agent. This evidence includes wavelike spread in countries, seasonal epidemics, and the rarity of Kawasaki disease in adults and infants less than 3 months old. Even more compelling is the recent identification by Rowley et al. Of an antigen of unknown origin in respiratory epithelial cells and macrophages from children with Kawasaki disease (1).

Despite suggestion that retroviruses, Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, or chlamydia may be important in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease, no infectious etiology has been proven. In this brief report, Esper et al. document the interesting finding of a novel human coronavirus, “New Haven coronavirus” (HCoVNH), in the respiratory secretions of a 6-month old infant diagnosed with Kawasaki disease. Subsequently, the authors performed a retrospective, case-controlled study of 11 Kawasaki disease patients less than 5 years of age from whom respiratory secretions were archived but had tested negative for respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1–3, and adenovirus by direct fluorescent antibody assay. These patients were matched with 2 control subjects. Eight (72.7%) of 11 case subjects and 1 (4.5%) of the 22 control subjects tested positive for HCoVNH by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (p=.0015). Further studies are needed to determine the precise role this, or other infectious pathogens, may have in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Reference

- Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. Detection of antigen in bronchial epithelium and macrophages in acute Kawasaki disease by use of synthetic antibody. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:856-65.

2. Eyaid WM, AlNouri DM, Rashed MS, et al. An inborn error of metabolism presenting as hypoxicischemic insult. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:134-6.

Inborn error of metabolism is frequently on the “bottom” of many differential diagnoses lists for common pediatric presenting complaints. Relative infrequency coupled with the occasional difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis presents unique challenges. Nonetheless, the importance of making this diagnosis is essential, given the frequent opportunity for pharmacologic and/ or dietary intervention to be therapeutic.

These authors present an interesting case of siblings presenting with seizures and central nervous system imaging consistent with hypoxicischemic insult who were subsequently diagnosed with isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency.

1. Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, et al. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:499-502.

Kawasaki disease, a systemic vasculitis of childhood, is the most common cause of childhood acquired heart disease in developed countries and frequently a diagnosis made in the inpatient setting. Although the etiology of Kawasaki disease is not known, there is evidence to suggest the disease may be triggered by an infectious agent. This evidence includes wavelike spread in countries, seasonal epidemics, and the rarity of Kawasaki disease in adults and infants less than 3 months old. Even more compelling is the recent identification by Rowley et al. Of an antigen of unknown origin in respiratory epithelial cells and macrophages from children with Kawasaki disease (1).

Despite suggestion that retroviruses, Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, or chlamydia may be important in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease, no infectious etiology has been proven. In this brief report, Esper et al. document the interesting finding of a novel human coronavirus, “New Haven coronavirus” (HCoVNH), in the respiratory secretions of a 6-month old infant diagnosed with Kawasaki disease. Subsequently, the authors performed a retrospective, case-controlled study of 11 Kawasaki disease patients less than 5 years of age from whom respiratory secretions were archived but had tested negative for respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1–3, and adenovirus by direct fluorescent antibody assay. These patients were matched with 2 control subjects. Eight (72.7%) of 11 case subjects and 1 (4.5%) of the 22 control subjects tested positive for HCoVNH by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (p=.0015). Further studies are needed to determine the precise role this, or other infectious pathogens, may have in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Reference

- Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. Detection of antigen in bronchial epithelium and macrophages in acute Kawasaki disease by use of synthetic antibody. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:856-65.

2. Eyaid WM, AlNouri DM, Rashed MS, et al. An inborn error of metabolism presenting as hypoxicischemic insult. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:134-6.

Inborn error of metabolism is frequently on the “bottom” of many differential diagnoses lists for common pediatric presenting complaints. Relative infrequency coupled with the occasional difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis presents unique challenges. Nonetheless, the importance of making this diagnosis is essential, given the frequent opportunity for pharmacologic and/ or dietary intervention to be therapeutic.

These authors present an interesting case of siblings presenting with seizures and central nervous system imaging consistent with hypoxicischemic insult who were subsequently diagnosed with isolated sulfite oxidase deficiency.

Pediatric in the Literature

Calicitonin Precusors and IL-8 as a Screen Panel for Bacterial Sepsis

Stryjewski GR, Nylen ES, Bell MJ, et al. Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and a rapid and sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors for the determination of bacterial sepsis in febrile neutropenic children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:129-35.

Identification of sensitive and specific markers for serious bacterial infection (SBI) in children has commanded significant attention in recent literature. These researchers present a prospective cohort study of 56 children aged 5 months to 17 years (median 6.7 years) with fever (axillary temperature ≥37.5°C or oral temperature ≥38°C) and neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count ≤500/mm3) admitted to Children’s National Medical Center during a 15-month period. Researchers hypothesized that a highly sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors (CTpr) would detect levels of CTpr early in the course of illness, and that these levels in conjunction with measured levels of the cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 would provide a sensitive and specific set of markers for diagnosing bacterial sepsis in the study population. Markers were measured at admission, at 24 hours and at 48 hours. CTpr at 24 hours (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 1.8 [1.2–2.8], p=.001) and IL8 (at 48 hours 1.08 [1.2–2.8], p=.02) were found to have association with bacterial sepsis. The authors conclude that based on the data generated, using cutoff values of 500 pg/mL for CTpr at 24 hours and 20 pg/mL for IL-8 at 48 hours would provide a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 90%. Reliable biochemical markers that are highly associated with SBI and/or sepsis will likely improve the care of pediatric patients by guiding more specific therapy and potentially limiting exposure to unnecessary antibiotic . The results of this study cannot be generalized to all pediatric patients with fever and risk for SBI, due to the unique attributes of the study population. However, the study does provide information for future research into the development of markers and/or scoring systems to aid in the early diagnosis of SBI/sepsis in the general pediatric population.

Which Tests are Helpful and Cost-Effective in the Evaluation of Pediatric Syncope?

Steinberg LA, Knilans TK. Syncope in children: diagnostic tests have a high cost and low yield. J Pediatr. 2005;146:355-8.

Evaluation of syncope in children is not uncommon. This evaluation can often include multiple expensive tests, and evidence defining the most efficacious and cost-effective course of evaluation is lacking. Researchers from the Children’s Heart Center at St. Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis and the Division of Cardiology at Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati present a retrospective review of 169 patients aged 4.5 to 18.7 years (mean, 13.1 ± 3.6) presenting to a tertiary care center for evaluation of transient loss of consciousness associated with loss of postural tone to describe the cost and utility of testing used to make a diagnosis. Costs were based on hospital costs for 1999 and did not include professional fees, the cost of clinic evaluations, or hospital admissions. There are significant limitations in the study design, and these are adequately discussed by the authors. A diagnosis was established in 128 patients (76%), and neurocardiogenic syncope was the most common diagnosis occurring in 116 patients (68%). Other diagnoses included seizure disorder (3 patients), pseudoseizure (2), anxiety disorder (2), psychogenic syncope (2) and 1 patient each with breathholding spells, long QT syndrome, and exertonal ventricular tachycardia. Tilt-testing had the highest diagnostic yield, although the researchers aptly point out that in the literature the specificity of tilt-testing ranges from 48 to 100% and that this test is rarely required to diagnose neurocardiogenic syncope, the most frequent diagnosis in this review. Loop memory cardiac monitoring had the lowest cost per diagnostic result. Electrocardiography had the lowest diagnostic yield and highest cost per test. Echocardiogram, chest radiograph, cardiac catheterization, electrophysiology studies, and evaluation of serum and body fluids were not diagnostic in this series. This respective review highlights the need for a consistent, evidence-based approach to this common presenting problem while emphasizing the importance of judicious testing guided by a thorough history and physical exam.

An Increase in Severe Community Acquired MRSA Infections in Texas

Gonzales BE, Martinez-Aguilar G, Hulten KG, et al. Severe staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:642-8.

Gonzales et al. describe data prospectively gathered since August 1, 2001, showing an increase in the number of severely ill patients with community acquired (CA) Staphylococcus aureus infections. Fourteen patients with a mean age of 12.9 years (range: 10–15 years) were admitted to the PICU with sepsis. Twelve patients had CA methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CAMRSA). Thirteen patients (93%) had bone and joint infections. Thirteen patients had pulmonary involvement. Acute prerenal failure and peripheral vascular thrombosis were present in 50% and 29% of patients, respectively. Thirteen patients were bacteremic. All CAMRSA isolates were resistant to erythromycin, without inducible resistance to clindamycin. The review is interesting in light of the other literature reviewed by the authors suggesting a trend toward more severe infections caused by CAMRSA.

TheoPhylline vs. Terubutaline in Critically III Asthmatics

Wheeler DS, Jacobs BR, Kenreigh CA, et al. Theophylline versus terbutaline in treating critically ill children with status asthmaticus: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:142-7.

Status asthmaticus is a common diagnosis on the pediatric inpatient unit and in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Inhaled beta-2 agonists, systemic corticosteroids, and supplemental oxygen are accepted as the standard of care for children with status asthmaticus who require admission. For critically ill children who are poorly responsive to the aforementioned triad of therapy, both theophylline and terbutaline are considered possible adjunctive therapies. Wheeler et al. suggest that the many studies failing to demonstrate added benefit of theophylline in non–critically ill patients has decreased the use of theophylline in the critical care setting, but point out that recent studies involving critically ill populations with status asthmaticus treated with theophylline have suggested benefit with comparison to placebo. Therefore, these researchers present a randomized, prospective, controlled, double-blind trial comparing the efficacy of theophylline alone, terbutaline alone, and theophylline and terbutaline together in critically ill pediatric patients receiving continuous nebulized albuterol and intravenous steroids. Forty patients with impending respiratory failure between the ages of 3 and 15 years were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: theophylline plus placebo (group 1), terbutaline plus placebo (group 2), or theophylline and terbutaline together (group 3). Thirty-six patients completed the study; 3 patients from group 1 were withdrawn due to parental request secondary to agitation (2 patients) and being inadvertently placed on a terbutaline infusion (1 patient). One patient from group 3 was withdrawn by the treating physician due to lack of improvement. All study participants, with the exception of the study pharmacist, were blinded to group assignment. Adjunctive therapies, including magnesium, ipatropium bromide and ketamine, were utilized at the discretion of the treating physician and were not controlled for. The primary outcome variable was change in a clinical scoring tool. Secondary outcomes variables included time to a specific clinical score, length of stay in the PICU, progression to mechanical ventilation, and incidence of adverse events. In addition, a cost analysis was performed isolating the 3 groups based on fiscal year 2003 cost estimates for theophylline and terbutaline. Results demonstrated no difference in the primary or secondary clinical outcome measures, with the exception of a higher incidence of nausea in group 3. The hospital costs were significantly lower in group 1 compared with groups 2 and 3 ($280 vs. $3,908 vs. $4,045, respectively, p<.0001). Significant limitations to the study include the lack of control of adjunctive therapies, a small sample size that confounds the ability to conclude no clinical difference between groups, and a baseline Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) Score in group 3 compared with groups 1 and 2. Despite these limitations the researchers suggest that the addition of intravenous theophylline to continuous nebulized albuterol and corticosteroids in the management of critically ill children with status asthmaticus is as safe and effective as adding intravenous terbutaline while being more cost-effective. Subsequent larger, well-controlled studies are required to support this conclusion.

Can Computerized Physician Ordering Create Errors?

Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293:1197-203.

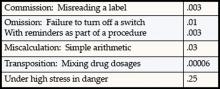

Adverse drug events are a frequent etiology of inpatient morbidity and prescribing errors are the most frequent source. Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is touted as a potential remedy for some types of adverse drug events. Few studies have investigated the potential for novel medication errors generated by a change to CPOE from conventional ordering. Koppel et al. present a quantitative and qualitative study of medication errors caused or exacerbated by a CPOE system. Interviews, surveys, and focus groups were the primary means of data collection. Housestaff who typically enter more than 9 orders per month were the primary study population, but data collection also included pharmacists, nursing staff , information technology managers, and attending physicians. The study was conducted in a tertiary-care teaching hospital between 2002 and 2004 utilizing a CPOE system in place since 1997. The CPOE system utilized is described as “monochromatic” and having “pre-Windows interfaces.” While not integrated with all hospital functions, the system was integrated with pharmacy and nursing medication lists. Researchers grouped errors into two broad categories: (1) information errors (fragmentation and systems integration failure) and (2) human-machine interface flaws (machine rules that do not correspond to work organization or usual behaviors). In total, 22 types of errors were recorded.

An example of an “information error” is assumed and incorrect dose information based on viewing doses intended only to describe pharmacy stocking practice―i.e. assuming that because the pharmacy stocks a 10mg dose of a medication, 10mg is an appropriate “minimally effective” dose. A “human-machine interface error” example is selecting an incorrect patient for ordering due to properties of the CPOE screen, such as the patient name not appearing on all screens. There are several important limitations to this study, but perhaps most important is the inability to generalize this data to other settings with potentially different physician users and software. Also important is a lack of description regarding physician user training and/or correlation of errors with amount of training or frequency of use, considering that the study population was defined as housestaff who may only use the system for 9 orders each . Despite these limitations, the study represents a requisite component to the growing trend toward the complete electronic record―namely, the use of objective investigations to study the safety and effectiveness of CPOE and the electronic record to promote the most optimal implementation and evolution of this new clinical tool.

Single-Dose Azithromycin for Acute Otitis Media

Arguedas A, Emparanza P, Schwartz RH, et al. A randomized, multicenter, double blind, double dummy trial of single dose azithromycin versus high dose amoxicillin for treatment of uncomplicated acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24: 153-61.

Acute otitis media is a common comorbid condition in pediatric inpatients. Patients at risk of having AOM with drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae can be treated with high-dose amoxicillin as a first-line therapy according to recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendations. Despite this recommendation, there is evidence of reduced in vitro activity of amoxicillin against β-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, as well as a lack of data from controlled and blinded studies demonstrating efficacy, adverse events and compliance for high-dose regimens. Azithromycin has in vitro activity against the 4 pathogens of clinical significance in AOM, and studies have shown that a single-dose regimen of azithromycin by the oral route is pharmacokinetically feasible, safe, and comparable in success rate to 3- and 5-day azithromycin regimens. With these considerations in mind, Arguedas et al. designed this study to compare single-dose (30 mg/kg) azithromycin with high-dose (90 mg/kg/day) amoxicillin in uncomplicated AOM.

In this double-blind, double-dummy, multinational, clinical trial, children between the ages of 6 and 30 months with uncomplicated AOM were randomized to treatment with single-dose azithromycin or high-dose amoxicillin (90 mg/kg/day, in 2 div doses) for 10 days. The primary outcome measure was clinical efficacy assessed at the end of treatment on the basis of a modified intent-to-treat (MITT) population. Secondary outcomes were analyses of safety and compliance. Three hundred thirteen patients were enrolled, of whom 83% were <2 years old, with 158 patients randomized to receive azithromycin and 154 to receive amoxicillin. Tympanocentesis was performed at baseline, and clinical responses were assessed at days 12–14 (end of therapy) and 25–28 (end of study). A middle-ear pathogen was detected in 212 patients (68%). H. Influenzae was the most common pathogen isolated (96 cases), followed by S. pneumoniae (92), M. catarrhalis (23), and S. pyogenes (23). At the end of therapy, clinical success rates for azithromycin and amoxicillin were comparable for all patients (84% and 84%, respectively) and for children <2 years of age (82% and 82%, respectively). At the end of the study, clinical efficacies among all microbiologic modified intent-to-treat evaluable subjects were comparable for patients treated with azithro(80%) and patients treated with amoxicillin (83%). The rates of adverse events for azithromycin and amoxicillin were 20% and 29%, respectively (p=.064). Diarrhea was more common in the amoxicillin group (17.5%) as compared to the azithromycin group (8.2%) (p=.017). Compliance, defined as completion of >80% of the study medications, was higher in the azithromycin group (100%) then in the amoxicillin group (90%) (p=.001). For practitioners ordering medications, compliance and efficacy are uppermost considerations. Single-dose azithromycin ensured 100% compliance, decreased adverse reactions, and equal efficacy, compared to high-dose amoxicillin in this well designed, randomized, controlled trial. (Jadad Score = 4/5) all patients (84% and 84%, respectively) and for children <2 years of age (82% and 82%, respectively). At the end of the study, clinical efficacies among all microbiologic modified intent-to-treat evaluable subjects were comparable for patients treated with azithromycin (80%) and patients treated with amoxicillin (83%). The rates of adverse events for azithromycin and amoxicillin were 20% and 29%, respectively

(p=.064). Diarrhea was more common in the amoxicillin group (17.5%) as compared to the azithromycin group (8.2%) (p=.017). Compliance, defined as completion of >80% of the study medications, was higher in the azithromycin group (100%) then in the amoxicillin group (90%) (p=.001). For practitioners ordering medications, compliance and efficacy are uppermost considerations. Single-dose azithromycin ensured 100% compliance, decreased adverse reactions, and equal efficacy, compared to high-dose amoxicillin in this well-designed, randomized, controlled trial. (Jadad Score = 4/5)

Calicitonin Precusors and IL-8 as a Screen Panel for Bacterial Sepsis

Stryjewski GR, Nylen ES, Bell MJ, et al. Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and a rapid and sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors for the determination of bacterial sepsis in febrile neutropenic children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:129-35.

Identification of sensitive and specific markers for serious bacterial infection (SBI) in children has commanded significant attention in recent literature. These researchers present a prospective cohort study of 56 children aged 5 months to 17 years (median 6.7 years) with fever (axillary temperature ≥37.5°C or oral temperature ≥38°C) and neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count ≤500/mm3) admitted to Children’s National Medical Center during a 15-month period. Researchers hypothesized that a highly sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors (CTpr) would detect levels of CTpr early in the course of illness, and that these levels in conjunction with measured levels of the cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 would provide a sensitive and specific set of markers for diagnosing bacterial sepsis in the study population. Markers were measured at admission, at 24 hours and at 48 hours. CTpr at 24 hours (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 1.8 [1.2–2.8], p=.001) and IL8 (at 48 hours 1.08 [1.2–2.8], p=.02) were found to have association with bacterial sepsis. The authors conclude that based on the data generated, using cutoff values of 500 pg/mL for CTpr at 24 hours and 20 pg/mL for IL-8 at 48 hours would provide a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 90%. Reliable biochemical markers that are highly associated with SBI and/or sepsis will likely improve the care of pediatric patients by guiding more specific therapy and potentially limiting exposure to unnecessary antibiotic . The results of this study cannot be generalized to all pediatric patients with fever and risk for SBI, due to the unique attributes of the study population. However, the study does provide information for future research into the development of markers and/or scoring systems to aid in the early diagnosis of SBI/sepsis in the general pediatric population.

Which Tests are Helpful and Cost-Effective in the Evaluation of Pediatric Syncope?

Steinberg LA, Knilans TK. Syncope in children: diagnostic tests have a high cost and low yield. J Pediatr. 2005;146:355-8.

Evaluation of syncope in children is not uncommon. This evaluation can often include multiple expensive tests, and evidence defining the most efficacious and cost-effective course of evaluation is lacking. Researchers from the Children’s Heart Center at St. Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis and the Division of Cardiology at Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati present a retrospective review of 169 patients aged 4.5 to 18.7 years (mean, 13.1 ± 3.6) presenting to a tertiary care center for evaluation of transient loss of consciousness associated with loss of postural tone to describe the cost and utility of testing used to make a diagnosis. Costs were based on hospital costs for 1999 and did not include professional fees, the cost of clinic evaluations, or hospital admissions. There are significant limitations in the study design, and these are adequately discussed by the authors. A diagnosis was established in 128 patients (76%), and neurocardiogenic syncope was the most common diagnosis occurring in 116 patients (68%). Other diagnoses included seizure disorder (3 patients), pseudoseizure (2), anxiety disorder (2), psychogenic syncope (2) and 1 patient each with breathholding spells, long QT syndrome, and exertonal ventricular tachycardia. Tilt-testing had the highest diagnostic yield, although the researchers aptly point out that in the literature the specificity of tilt-testing ranges from 48 to 100% and that this test is rarely required to diagnose neurocardiogenic syncope, the most frequent diagnosis in this review. Loop memory cardiac monitoring had the lowest cost per diagnostic result. Electrocardiography had the lowest diagnostic yield and highest cost per test. Echocardiogram, chest radiograph, cardiac catheterization, electrophysiology studies, and evaluation of serum and body fluids were not diagnostic in this series. This respective review highlights the need for a consistent, evidence-based approach to this common presenting problem while emphasizing the importance of judicious testing guided by a thorough history and physical exam.

An Increase in Severe Community Acquired MRSA Infections in Texas

Gonzales BE, Martinez-Aguilar G, Hulten KG, et al. Severe staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:642-8.

Gonzales et al. describe data prospectively gathered since August 1, 2001, showing an increase in the number of severely ill patients with community acquired (CA) Staphylococcus aureus infections. Fourteen patients with a mean age of 12.9 years (range: 10–15 years) were admitted to the PICU with sepsis. Twelve patients had CA methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CAMRSA). Thirteen patients (93%) had bone and joint infections. Thirteen patients had pulmonary involvement. Acute prerenal failure and peripheral vascular thrombosis were present in 50% and 29% of patients, respectively. Thirteen patients were bacteremic. All CAMRSA isolates were resistant to erythromycin, without inducible resistance to clindamycin. The review is interesting in light of the other literature reviewed by the authors suggesting a trend toward more severe infections caused by CAMRSA.

TheoPhylline vs. Terubutaline in Critically III Asthmatics

Wheeler DS, Jacobs BR, Kenreigh CA, et al. Theophylline versus terbutaline in treating critically ill children with status asthmaticus: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:142-7.

Status asthmaticus is a common diagnosis on the pediatric inpatient unit and in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Inhaled beta-2 agonists, systemic corticosteroids, and supplemental oxygen are accepted as the standard of care for children with status asthmaticus who require admission. For critically ill children who are poorly responsive to the aforementioned triad of therapy, both theophylline and terbutaline are considered possible adjunctive therapies. Wheeler et al. suggest that the many studies failing to demonstrate added benefit of theophylline in non–critically ill patients has decreased the use of theophylline in the critical care setting, but point out that recent studies involving critically ill populations with status asthmaticus treated with theophylline have suggested benefit with comparison to placebo. Therefore, these researchers present a randomized, prospective, controlled, double-blind trial comparing the efficacy of theophylline alone, terbutaline alone, and theophylline and terbutaline together in critically ill pediatric patients receiving continuous nebulized albuterol and intravenous steroids. Forty patients with impending respiratory failure between the ages of 3 and 15 years were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: theophylline plus placebo (group 1), terbutaline plus placebo (group 2), or theophylline and terbutaline together (group 3). Thirty-six patients completed the study; 3 patients from group 1 were withdrawn due to parental request secondary to agitation (2 patients) and being inadvertently placed on a terbutaline infusion (1 patient). One patient from group 3 was withdrawn by the treating physician due to lack of improvement. All study participants, with the exception of the study pharmacist, were blinded to group assignment. Adjunctive therapies, including magnesium, ipatropium bromide and ketamine, were utilized at the discretion of the treating physician and were not controlled for. The primary outcome variable was change in a clinical scoring tool. Secondary outcomes variables included time to a specific clinical score, length of stay in the PICU, progression to mechanical ventilation, and incidence of adverse events. In addition, a cost analysis was performed isolating the 3 groups based on fiscal year 2003 cost estimates for theophylline and terbutaline. Results demonstrated no difference in the primary or secondary clinical outcome measures, with the exception of a higher incidence of nausea in group 3. The hospital costs were significantly lower in group 1 compared with groups 2 and 3 ($280 vs. $3,908 vs. $4,045, respectively, p<.0001). Significant limitations to the study include the lack of control of adjunctive therapies, a small sample size that confounds the ability to conclude no clinical difference between groups, and a baseline Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) Score in group 3 compared with groups 1 and 2. Despite these limitations the researchers suggest that the addition of intravenous theophylline to continuous nebulized albuterol and corticosteroids in the management of critically ill children with status asthmaticus is as safe and effective as adding intravenous terbutaline while being more cost-effective. Subsequent larger, well-controlled studies are required to support this conclusion.

Can Computerized Physician Ordering Create Errors?

Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293:1197-203.

Adverse drug events are a frequent etiology of inpatient morbidity and prescribing errors are the most frequent source. Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is touted as a potential remedy for some types of adverse drug events. Few studies have investigated the potential for novel medication errors generated by a change to CPOE from conventional ordering. Koppel et al. present a quantitative and qualitative study of medication errors caused or exacerbated by a CPOE system. Interviews, surveys, and focus groups were the primary means of data collection. Housestaff who typically enter more than 9 orders per month were the primary study population, but data collection also included pharmacists, nursing staff , information technology managers, and attending physicians. The study was conducted in a tertiary-care teaching hospital between 2002 and 2004 utilizing a CPOE system in place since 1997. The CPOE system utilized is described as “monochromatic” and having “pre-Windows interfaces.” While not integrated with all hospital functions, the system was integrated with pharmacy and nursing medication lists. Researchers grouped errors into two broad categories: (1) information errors (fragmentation and systems integration failure) and (2) human-machine interface flaws (machine rules that do not correspond to work organization or usual behaviors). In total, 22 types of errors were recorded.

An example of an “information error” is assumed and incorrect dose information based on viewing doses intended only to describe pharmacy stocking practice―i.e. assuming that because the pharmacy stocks a 10mg dose of a medication, 10mg is an appropriate “minimally effective” dose. A “human-machine interface error” example is selecting an incorrect patient for ordering due to properties of the CPOE screen, such as the patient name not appearing on all screens. There are several important limitations to this study, but perhaps most important is the inability to generalize this data to other settings with potentially different physician users and software. Also important is a lack of description regarding physician user training and/or correlation of errors with amount of training or frequency of use, considering that the study population was defined as housestaff who may only use the system for 9 orders each . Despite these limitations, the study represents a requisite component to the growing trend toward the complete electronic record―namely, the use of objective investigations to study the safety and effectiveness of CPOE and the electronic record to promote the most optimal implementation and evolution of this new clinical tool.

Single-Dose Azithromycin for Acute Otitis Media

Arguedas A, Emparanza P, Schwartz RH, et al. A randomized, multicenter, double blind, double dummy trial of single dose azithromycin versus high dose amoxicillin for treatment of uncomplicated acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24: 153-61.

Acute otitis media is a common comorbid condition in pediatric inpatients. Patients at risk of having AOM with drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae can be treated with high-dose amoxicillin as a first-line therapy according to recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendations. Despite this recommendation, there is evidence of reduced in vitro activity of amoxicillin against β-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, as well as a lack of data from controlled and blinded studies demonstrating efficacy, adverse events and compliance for high-dose regimens. Azithromycin has in vitro activity against the 4 pathogens of clinical significance in AOM, and studies have shown that a single-dose regimen of azithromycin by the oral route is pharmacokinetically feasible, safe, and comparable in success rate to 3- and 5-day azithromycin regimens. With these considerations in mind, Arguedas et al. designed this study to compare single-dose (30 mg/kg) azithromycin with high-dose (90 mg/kg/day) amoxicillin in uncomplicated AOM.

In this double-blind, double-dummy, multinational, clinical trial, children between the ages of 6 and 30 months with uncomplicated AOM were randomized to treatment with single-dose azithromycin or high-dose amoxicillin (90 mg/kg/day, in 2 div doses) for 10 days. The primary outcome measure was clinical efficacy assessed at the end of treatment on the basis of a modified intent-to-treat (MITT) population. Secondary outcomes were analyses of safety and compliance. Three hundred thirteen patients were enrolled, of whom 83% were <2 years old, with 158 patients randomized to receive azithromycin and 154 to receive amoxicillin. Tympanocentesis was performed at baseline, and clinical responses were assessed at days 12–14 (end of therapy) and 25–28 (end of study). A middle-ear pathogen was detected in 212 patients (68%). H. Influenzae was the most common pathogen isolated (96 cases), followed by S. pneumoniae (92), M. catarrhalis (23), and S. pyogenes (23). At the end of therapy, clinical success rates for azithromycin and amoxicillin were comparable for all patients (84% and 84%, respectively) and for children <2 years of age (82% and 82%, respectively). At the end of the study, clinical efficacies among all microbiologic modified intent-to-treat evaluable subjects were comparable for patients treated with azithro(80%) and patients treated with amoxicillin (83%). The rates of adverse events for azithromycin and amoxicillin were 20% and 29%, respectively (p=.064). Diarrhea was more common in the amoxicillin group (17.5%) as compared to the azithromycin group (8.2%) (p=.017). Compliance, defined as completion of >80% of the study medications, was higher in the azithromycin group (100%) then in the amoxicillin group (90%) (p=.001). For practitioners ordering medications, compliance and efficacy are uppermost considerations. Single-dose azithromycin ensured 100% compliance, decreased adverse reactions, and equal efficacy, compared to high-dose amoxicillin in this well designed, randomized, controlled trial. (Jadad Score = 4/5) all patients (84% and 84%, respectively) and for children <2 years of age (82% and 82%, respectively). At the end of the study, clinical efficacies among all microbiologic modified intent-to-treat evaluable subjects were comparable for patients treated with azithromycin (80%) and patients treated with amoxicillin (83%). The rates of adverse events for azithromycin and amoxicillin were 20% and 29%, respectively

(p=.064). Diarrhea was more common in the amoxicillin group (17.5%) as compared to the azithromycin group (8.2%) (p=.017). Compliance, defined as completion of >80% of the study medications, was higher in the azithromycin group (100%) then in the amoxicillin group (90%) (p=.001). For practitioners ordering medications, compliance and efficacy are uppermost considerations. Single-dose azithromycin ensured 100% compliance, decreased adverse reactions, and equal efficacy, compared to high-dose amoxicillin in this well-designed, randomized, controlled trial. (Jadad Score = 4/5)

Calicitonin Precusors and IL-8 as a Screen Panel for Bacterial Sepsis

Stryjewski GR, Nylen ES, Bell MJ, et al. Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and a rapid and sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors for the determination of bacterial sepsis in febrile neutropenic children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:129-35.

Identification of sensitive and specific markers for serious bacterial infection (SBI) in children has commanded significant attention in recent literature. These researchers present a prospective cohort study of 56 children aged 5 months to 17 years (median 6.7 years) with fever (axillary temperature ≥37.5°C or oral temperature ≥38°C) and neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count ≤500/mm3) admitted to Children’s National Medical Center during a 15-month period. Researchers hypothesized that a highly sensitive assay for calcitonin precursors (CTpr) would detect levels of CTpr early in the course of illness, and that these levels in conjunction with measured levels of the cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 would provide a sensitive and specific set of markers for diagnosing bacterial sepsis in the study population. Markers were measured at admission, at 24 hours and at 48 hours. CTpr at 24 hours (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 1.8 [1.2–2.8], p=.001) and IL8 (at 48 hours 1.08 [1.2–2.8], p=.02) were found to have association with bacterial sepsis. The authors conclude that based on the data generated, using cutoff values of 500 pg/mL for CTpr at 24 hours and 20 pg/mL for IL-8 at 48 hours would provide a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 90%. Reliable biochemical markers that are highly associated with SBI and/or sepsis will likely improve the care of pediatric patients by guiding more specific therapy and potentially limiting exposure to unnecessary antibiotic . The results of this study cannot be generalized to all pediatric patients with fever and risk for SBI, due to the unique attributes of the study population. However, the study does provide information for future research into the development of markers and/or scoring systems to aid in the early diagnosis of SBI/sepsis in the general pediatric population.

Which Tests are Helpful and Cost-Effective in the Evaluation of Pediatric Syncope?

Steinberg LA, Knilans TK. Syncope in children: diagnostic tests have a high cost and low yield. J Pediatr. 2005;146:355-8.

Evaluation of syncope in children is not uncommon. This evaluation can often include multiple expensive tests, and evidence defining the most efficacious and cost-effective course of evaluation is lacking. Researchers from the Children’s Heart Center at St. Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis and the Division of Cardiology at Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati present a retrospective review of 169 patients aged 4.5 to 18.7 years (mean, 13.1 ± 3.6) presenting to a tertiary care center for evaluation of transient loss of consciousness associated with loss of postural tone to describe the cost and utility of testing used to make a diagnosis. Costs were based on hospital costs for 1999 and did not include professional fees, the cost of clinic evaluations, or hospital admissions. There are significant limitations in the study design, and these are adequately discussed by the authors. A diagnosis was established in 128 patients (76%), and neurocardiogenic syncope was the most common diagnosis occurring in 116 patients (68%). Other diagnoses included seizure disorder (3 patients), pseudoseizure (2), anxiety disorder (2), psychogenic syncope (2) and 1 patient each with breathholding spells, long QT syndrome, and exertonal ventricular tachycardia. Tilt-testing had the highest diagnostic yield, although the researchers aptly point out that in the literature the specificity of tilt-testing ranges from 48 to 100% and that this test is rarely required to diagnose neurocardiogenic syncope, the most frequent diagnosis in this review. Loop memory cardiac monitoring had the lowest cost per diagnostic result. Electrocardiography had the lowest diagnostic yield and highest cost per test. Echocardiogram, chest radiograph, cardiac catheterization, electrophysiology studies, and evaluation of serum and body fluids were not diagnostic in this series. This respective review highlights the need for a consistent, evidence-based approach to this common presenting problem while emphasizing the importance of judicious testing guided by a thorough history and physical exam.

An Increase in Severe Community Acquired MRSA Infections in Texas

Gonzales BE, Martinez-Aguilar G, Hulten KG, et al. Severe staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:642-8.

Gonzales et al. describe data prospectively gathered since August 1, 2001, showing an increase in the number of severely ill patients with community acquired (CA) Staphylococcus aureus infections. Fourteen patients with a mean age of 12.9 years (range: 10–15 years) were admitted to the PICU with sepsis. Twelve patients had CA methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CAMRSA). Thirteen patients (93%) had bone and joint infections. Thirteen patients had pulmonary involvement. Acute prerenal failure and peripheral vascular thrombosis were present in 50% and 29% of patients, respectively. Thirteen patients were bacteremic. All CAMRSA isolates were resistant to erythromycin, without inducible resistance to clindamycin. The review is interesting in light of the other literature reviewed by the authors suggesting a trend toward more severe infections caused by CAMRSA.

TheoPhylline vs. Terubutaline in Critically III Asthmatics

Wheeler DS, Jacobs BR, Kenreigh CA, et al. Theophylline versus terbutaline in treating critically ill children with status asthmaticus: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:142-7.

Status asthmaticus is a common diagnosis on the pediatric inpatient unit and in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Inhaled beta-2 agonists, systemic corticosteroids, and supplemental oxygen are accepted as the standard of care for children with status asthmaticus who require admission. For critically ill children who are poorly responsive to the aforementioned triad of therapy, both theophylline and terbutaline are considered possible adjunctive therapies. Wheeler et al. suggest that the many studies failing to demonstrate added benefit of theophylline in non–critically ill patients has decreased the use of theophylline in the critical care setting, but point out that recent studies involving critically ill populations with status asthmaticus treated with theophylline have suggested benefit with comparison to placebo. Therefore, these researchers present a randomized, prospective, controlled, double-blind trial comparing the efficacy of theophylline alone, terbutaline alone, and theophylline and terbutaline together in critically ill pediatric patients receiving continuous nebulized albuterol and intravenous steroids. Forty patients with impending respiratory failure between the ages of 3 and 15 years were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: theophylline plus placebo (group 1), terbutaline plus placebo (group 2), or theophylline and terbutaline together (group 3). Thirty-six patients completed the study; 3 patients from group 1 were withdrawn due to parental request secondary to agitation (2 patients) and being inadvertently placed on a terbutaline infusion (1 patient). One patient from group 3 was withdrawn by the treating physician due to lack of improvement. All study participants, with the exception of the study pharmacist, were blinded to group assignment. Adjunctive therapies, including magnesium, ipatropium bromide and ketamine, were utilized at the discretion of the treating physician and were not controlled for. The primary outcome variable was change in a clinical scoring tool. Secondary outcomes variables included time to a specific clinical score, length of stay in the PICU, progression to mechanical ventilation, and incidence of adverse events. In addition, a cost analysis was performed isolating the 3 groups based on fiscal year 2003 cost estimates for theophylline and terbutaline. Results demonstrated no difference in the primary or secondary clinical outcome measures, with the exception of a higher incidence of nausea in group 3. The hospital costs were significantly lower in group 1 compared with groups 2 and 3 ($280 vs. $3,908 vs. $4,045, respectively, p<.0001). Significant limitations to the study include the lack of control of adjunctive therapies, a small sample size that confounds the ability to conclude no clinical difference between groups, and a baseline Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) Score in group 3 compared with groups 1 and 2. Despite these limitations the researchers suggest that the addition of intravenous theophylline to continuous nebulized albuterol and corticosteroids in the management of critically ill children with status asthmaticus is as safe and effective as adding intravenous terbutaline while being more cost-effective. Subsequent larger, well-controlled studies are required to support this conclusion.

Can Computerized Physician Ordering Create Errors?

Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293:1197-203.

Adverse drug events are a frequent etiology of inpatient morbidity and prescribing errors are the most frequent source. Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is touted as a potential remedy for some types of adverse drug events. Few studies have investigated the potential for novel medication errors generated by a change to CPOE from conventional ordering. Koppel et al. present a quantitative and qualitative study of medication errors caused or exacerbated by a CPOE system. Interviews, surveys, and focus groups were the primary means of data collection. Housestaff who typically enter more than 9 orders per month were the primary study population, but data collection also included pharmacists, nursing staff , information technology managers, and attending physicians. The study was conducted in a tertiary-care teaching hospital between 2002 and 2004 utilizing a CPOE system in place since 1997. The CPOE system utilized is described as “monochromatic” and having “pre-Windows interfaces.” While not integrated with all hospital functions, the system was integrated with pharmacy and nursing medication lists. Researchers grouped errors into two broad categories: (1) information errors (fragmentation and systems integration failure) and (2) human-machine interface flaws (machine rules that do not correspond to work organization or usual behaviors). In total, 22 types of errors were recorded.

An example of an “information error” is assumed and incorrect dose information based on viewing doses intended only to describe pharmacy stocking practice―i.e. assuming that because the pharmacy stocks a 10mg dose of a medication, 10mg is an appropriate “minimally effective” dose. A “human-machine interface error” example is selecting an incorrect patient for ordering due to properties of the CPOE screen, such as the patient name not appearing on all screens. There are several important limitations to this study, but perhaps most important is the inability to generalize this data to other settings with potentially different physician users and software. Also important is a lack of description regarding physician user training and/or correlation of errors with amount of training or frequency of use, considering that the study population was defined as housestaff who may only use the system for 9 orders each . Despite these limitations, the study represents a requisite component to the growing trend toward the complete electronic record―namely, the use of objective investigations to study the safety and effectiveness of CPOE and the electronic record to promote the most optimal implementation and evolution of this new clinical tool.

Single-Dose Azithromycin for Acute Otitis Media

Arguedas A, Emparanza P, Schwartz RH, et al. A randomized, multicenter, double blind, double dummy trial of single dose azithromycin versus high dose amoxicillin for treatment of uncomplicated acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24: 153-61.

Acute otitis media is a common comorbid condition in pediatric inpatients. Patients at risk of having AOM with drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae can be treated with high-dose amoxicillin as a first-line therapy according to recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendations. Despite this recommendation, there is evidence of reduced in vitro activity of amoxicillin against β-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, as well as a lack of data from controlled and blinded studies demonstrating efficacy, adverse events and compliance for high-dose regimens. Azithromycin has in vitro activity against the 4 pathogens of clinical significance in AOM, and studies have shown that a single-dose regimen of azithromycin by the oral route is pharmacokinetically feasible, safe, and comparable in success rate to 3- and 5-day azithromycin regimens. With these considerations in mind, Arguedas et al. designed this study to compare single-dose (30 mg/kg) azithromycin with high-dose (90 mg/kg/day) amoxicillin in uncomplicated AOM.

In this double-blind, double-dummy, multinational, clinical trial, children between the ages of 6 and 30 months with uncomplicated AOM were randomized to treatment with single-dose azithromycin or high-dose amoxicillin (90 mg/kg/day, in 2 div doses) for 10 days. The primary outcome measure was clinical efficacy assessed at the end of treatment on the basis of a modified intent-to-treat (MITT) population. Secondary outcomes were analyses of safety and compliance. Three hundred thirteen patients were enrolled, of whom 83% were <2 years old, with 158 patients randomized to receive azithromycin and 154 to receive amoxicillin. Tympanocentesis was performed at baseline, and clinical responses were assessed at days 12–14 (end of therapy) and 25–28 (end of study). A middle-ear pathogen was detected in 212 patients (68%). H. Influenzae was the most common pathogen isolated (96 cases), followed by S. pneumoniae (92), M. catarrhalis (23), and S. pyogenes (23). At the end of therapy, clinical success rates for azithromycin and amoxicillin were comparable for all patients (84% and 84%, respectively) and for children <2 years of age (82% and 82%, respectively). At the end of the study, clinical efficacies among all microbiologic modified intent-to-treat evaluable subjects were comparable for patients treated with azithro(80%) and patients treated with amoxicillin (83%). The rates of adverse events for azithromycin and amoxicillin were 20% and 29%, respectively (p=.064). Diarrhea was more common in the amoxicillin group (17.5%) as compared to the azithromycin group (8.2%) (p=.017). Compliance, defined as completion of >80% of the study medications, was higher in the azithromycin group (100%) then in the amoxicillin group (90%) (p=.001). For practitioners ordering medications, compliance and efficacy are uppermost considerations. Single-dose azithromycin ensured 100% compliance, decreased adverse reactions, and equal efficacy, compared to high-dose amoxicillin in this well designed, randomized, controlled trial. (Jadad Score = 4/5) all patients (84% and 84%, respectively) and for children <2 years of age (82% and 82%, respectively). At the end of the study, clinical efficacies among all microbiologic modified intent-to-treat evaluable subjects were comparable for patients treated with azithromycin (80%) and patients treated with amoxicillin (83%). The rates of adverse events for azithromycin and amoxicillin were 20% and 29%, respectively

(p=.064). Diarrhea was more common in the amoxicillin group (17.5%) as compared to the azithromycin group (8.2%) (p=.017). Compliance, defined as completion of >80% of the study medications, was higher in the azithromycin group (100%) then in the amoxicillin group (90%) (p=.001). For practitioners ordering medications, compliance and efficacy are uppermost considerations. Single-dose azithromycin ensured 100% compliance, decreased adverse reactions, and equal efficacy, compared to high-dose amoxicillin in this well-designed, randomized, controlled trial. (Jadad Score = 4/5)

In the Literature

Coronary-Artery Revascularization Before Elective Major Vascular Sugery

McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2861-3.

Cardiac risk stratification and treatment prior to non-cardiac surgery is a frequent reason for medical consultation, and yet the optimal approach to managing these patients remains controversial. National guidelines, based on expert opinion and inferred from published data, suggest that preoperative cardiac revascularization be reserved for patients with unstable coronary syndromes or for whom coronary artery bypass grad ing has been shown to improve mortality. Despite these recommendations, there remains considerable variability in clinical practice, which is compounded by a paucity of prospective randomized trials to validate one approach over another.

In this multicenter randomized controlled trial, McFalls et al. studied whether coronary artery revascularization prior to elective vascular surgery would reduce mortality among a cohort of patients with angiographically documented stable coronary artery disease. The investigators evaluated 5859 patients from 18 centers scheduled for abdominal aortic aneurysm or lower extremity vascular surgery. Patients felt to be at high risk for perioperative cardiac complications based on cardiology consultation, established clinical criteria, or the presence of ischemia on stress imaging studies were referred for coronary angiography. Of this cohort, 4669 (80%) were excluded due to subsequent determination of insufficient cardiac risk (28%), urgent need for vascular surgery (18%), severe comorbid illness (13%), patient preference (11%), or prior revascularization without new ischemia (11%). Of the 1190 patients who underwent angiography, 680 were excluded due to protocol criteria including: the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (54%), coronary disease not amenable to revascularization (32%), led main artery stenosis ≥ 50% (8%), led ventricular ejection fraction <20% (2%), or severe aortic stenosis (AVA<1.0 cm2) (1%).

Of the 510 patients who remained, 252 were randomized to proceed with vascular surgery with optimal medical management, of which 9 crossed over due to the need for urgent cardiac revascularization. Two hundred fifty-eight patients were randomized to elective preoperative revascularization; 99 underwent CABG, 141 underwent PCI, and 18 were excluded due to need for urgent vascular surgery, patient preference, or in one case, stroke. Both groups were similar with respect to baseline clinical variables, including the incidence of previous myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, led ventricular ejection fraction, and 3vessel coronary artery disease. They were also similar in the use of perioperative betablockers (~ 85%), statins, and aspirin.

At 2.7 years after randomization, mortality was 22% in the revascularization group and 22% in the medical management group, the relative risk was 0.98 (95% CI 0.7-1.37; p=.92), which was not statistically significant. The median time from randomization to vascular surgery was 54 days in the revascularization group and 18 days in the medical management group not undergoing revascularization (p<.001). Although not designed to address short-term outcomes, there were no differences in the rates of early postoperative myocardial infarction, death, or hospital length of stay. It is also worth noting that 316 of the 510 patients who were ultimately randomized had undergone nuclear imaging studies, of which 226 (72%) had moderate to large reversible perfusion defects detected. These outcome data suggest that the presence of reversible perfusions defects is not in itself a reason for preoperative revascularization.

This well-designed study demonstrates that in the absence of unstable coronary syndromes, led main disease, severe aortic stenosis, or severely depressed led ventricular ejection fraction, there is no morbidity or mortality benefit to revascularization among patients with stable coronary artery disease prior to vascular surgery. Because vascular surgery is the highest risk category among non-cardiac procedures, it may be reasonable to extend these findings to lower risk surgeries as well, and in this sense this study is particularly relevant to consultative practice. While this study provides clear evidence on how to manage this cohort of patients, it remains unclear what the optimal strategy is to identify and manage those patients who were excluded from the trial. (DF)

Amiodarone or a Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrilator for Congestive Heart Failure

Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005 20;352:225-37.

Ventricular arrhythmias are the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in patients with systolic heart failure. Treatment with antiarrhythmic drug therapy has failed to improve survival in these patients, due to their proarrhythmic effects. Unlike other antiarrhythmics, amiodarone is a drug with low proarrhythmic effects. Some studies have suggested that amiodarone may be beneficial in patients with systolic heart failure. Conversely, several primary and secondary prevention trials have demonstrated that placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) confers a survival benefit in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. However, the role of ICDs in nonischemic heart failure remained unproven.

Bardy and colleagues developed the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCDHeFT) to evaluate the hypothesis that treatment with amiodarone or a shock-only, single-lead ICD would decrease death from any cause in a population of patients with mild to moderate heart failure. They randomly assigned 2521 patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or II heart failure (and a led ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less to conventional medical therapy plus placebo, conventional therapy plus treatment with amiodarone or conventional therapy plus a conservatively programmed, shock-only, single-lead ICD.

Fifty-two percent of patients had ischemic heart failure and 48% had nonischemic heart failure. Placebo and amiodarone were given in double-blind fashion. The primary endpoint was death from any cause with a median followup of 45.5 months. The results were as follows:

Placebo Group - 244 deaths (29% Death Rate)

Amiodarone Group - 240 deaths (28% Death Rate)

ICD Group - 182 deaths (22% Death Rate)

Patients treated with amiodarone had a similar risk of death as those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 1.06; 97.5% CI: 0.86–1.30; p=0.53). Patients implanted with an ICD had a 23% decreased risk of death when compared with those who received placebo (0.77; 97.5% CI: 0.62–0.96; p=.007). This resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 7.2% at 5 years. The authors concluded that in patients with NYHA class II or III heart failure and a LVEF of 35% or less, implantation of a single-lead, shock-only ICD reduced overall mortality by 23%, while treatment with amiodarone had no effect on survival. The benefit of ICD placement reached or approached significance in both the ischemic (hazard ratio .79, CI: 0.60–1.04, p= .05) and nonischemic (hazard ratio 0.73, CI: 0.50–1.07, p= 0.06) subgroups.

It is important to note that an additional subgroup analysis showed that ICD therapy had a significant survival benefit only in NYHA class II patients but not in NYHA class III patients. Amiodarone therapy had no benefit in class II patients and actually decreased survival in class III patients compared to those receiving placebo. In light of results from previous trials that demonstrated a greater survival benefit from ICD placement with worsening ejection fraction in patients with ischemic heart failure, the authors were unable to explain whether the differences in subclasses were biologically plausible.

This study is important for several reasons. First, it suggested that patients with systolic heart failure due to either ischemic or non ischemic causes would benefit from placement of an ICD. Second, these results support the conclusions of previous trials that demonstrate a survival advantage of ICD placement in patients with ischemic heart failure. Finally, this study also demonstrates that amiodarone therapy offers no survival benefit in this population of patients. (JL)

Clopidogrel versus Aspirin and Esomeprazole to Prevent Recurrent Ulcer Bleeding

Chan F, Ching J, Hung L, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to prevent recurrent ulcer bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:238-44.

The optimal choice of antiplatelet therapy for patients with coronary heart disease who have had a recent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage has not been well studied. Clopidogrel has been shown to cause fewer episodes of gastrointestinal hemorrhage than aspirin, but it is unknown whether clopidogrel monotherapy is in fact superior to aspirin plus a protonpump inhibitor. In this prospective, randomized, doubleblind trial, Chan and colleagues hypothesize that clopidogrel monotherapy would “not be inferior” to aspirin plus esomeprazole in a population of patients who had recovered from aspirin-induced hemorrhagic ulcers.

The study population was drawn from patients taking aspirin who were evaluated for an upper gastrointestinal bleed and had ulcer disease documented on endoscopy. Patients with documented Helicobacter pylori infection were treated with a 1-week course of a standard triple-drug regimen. All subjects, regardless of H. pylori status, were treated with an 8-week course of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI). Inclusion criteria included endoscopic confirmation of ulcer healing and successful eradication of H. pylori, if it was present. The location of the ulcers was not specified in the study.

Exclusion criteria included use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, anticoagulant drugs, corticosteroids, or other anti-platelet agents; history of gastric surgery; presence of erosive esophagitis; gastric outlet obstruction; cancer; need for dialysis; or terminal illness.

Subjects who met the inclusion criteria were randomized to receive either 75 mg of clopidogrel and placebo or 80 mg of aspirin daily plus 20 mg of esomeprazole twice a day for a 12 months. Patients returned for evaluation every 3 months during the 1-year study period. The primary endpoint was recurrence of ulcer bleeding, which was predefined as clinical or laboratory evidence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage with a documented recurrence of ulcers on endoscopy. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding was a secondary endpoint.

Of 492 consecutive patients who were evaluated, 320 met inclusion criteria and were evenly divided into the clopidogrel plus placebo or the aspirin plus esomeprazole arms. Only 3 patients were lost to followup. During the study period, 34 cases of suspected gastrointestinal hemorrhage (defined as hematemesis, melena, or 2 g/dL decrease of hemoglobin) were identified. During endoscopy,14 cases were confirmed to be due to recurrent ulcer bleeding. Of these, 13 ulcers were in the clopidogrel arm (6 gastric ulcers, 5 duodenal, and 2 both) and 1 ulcer (duodenal) in the aspirin plus esomeprazole arm, a statistically significant difference (p=.001).

Fourteen patients were determined to have a lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Interestingly, these cases were evenly divided between the clopidogrel group (7 cases) and the aspirin plus esomeprazole (7 cases). This finding suggests the effect of esomeprazole in this study may be specific in preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal ulcer formation and hemorrhage. The 2 groups had equivalent rates of recurrent ischemic events.

This study addresses an important clinical question, frequently encountered by hospitalists. The recommendation that clopidogrel be used instead of aspirin in patients who require antiplatelet therapy but have a history of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage is based on studies using high-dose (325 mg) aspirin and excluded patients on acid-suppressing therapy. However, this study failed to prove noninferiority of clopidogrel to aspirin and esomeprazole for this indication. Although this study was not designed to show superiority of aspirin and esomeprazole over clopidogrel, these results indicate that this may be the case, and such a study would be timely. (CG)

Coronary-Artery Revascularization Before Elective Major Vascular Sugery

McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2861-3.

Cardiac risk stratification and treatment prior to non-cardiac surgery is a frequent reason for medical consultation, and yet the optimal approach to managing these patients remains controversial. National guidelines, based on expert opinion and inferred from published data, suggest that preoperative cardiac revascularization be reserved for patients with unstable coronary syndromes or for whom coronary artery bypass grad ing has been shown to improve mortality. Despite these recommendations, there remains considerable variability in clinical practice, which is compounded by a paucity of prospective randomized trials to validate one approach over another.

In this multicenter randomized controlled trial, McFalls et al. studied whether coronary artery revascularization prior to elective vascular surgery would reduce mortality among a cohort of patients with angiographically documented stable coronary artery disease. The investigators evaluated 5859 patients from 18 centers scheduled for abdominal aortic aneurysm or lower extremity vascular surgery. Patients felt to be at high risk for perioperative cardiac complications based on cardiology consultation, established clinical criteria, or the presence of ischemia on stress imaging studies were referred for coronary angiography. Of this cohort, 4669 (80%) were excluded due to subsequent determination of insufficient cardiac risk (28%), urgent need for vascular surgery (18%), severe comorbid illness (13%), patient preference (11%), or prior revascularization without new ischemia (11%). Of the 1190 patients who underwent angiography, 680 were excluded due to protocol criteria including: the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (54%), coronary disease not amenable to revascularization (32%), led main artery stenosis ≥ 50% (8%), led ventricular ejection fraction <20% (2%), or severe aortic stenosis (AVA<1.0 cm2) (1%).

Of the 510 patients who remained, 252 were randomized to proceed with vascular surgery with optimal medical management, of which 9 crossed over due to the need for urgent cardiac revascularization. Two hundred fifty-eight patients were randomized to elective preoperative revascularization; 99 underwent CABG, 141 underwent PCI, and 18 were excluded due to need for urgent vascular surgery, patient preference, or in one case, stroke. Both groups were similar with respect to baseline clinical variables, including the incidence of previous myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, led ventricular ejection fraction, and 3vessel coronary artery disease. They were also similar in the use of perioperative betablockers (~ 85%), statins, and aspirin.

At 2.7 years after randomization, mortality was 22% in the revascularization group and 22% in the medical management group, the relative risk was 0.98 (95% CI 0.7-1.37; p=.92), which was not statistically significant. The median time from randomization to vascular surgery was 54 days in the revascularization group and 18 days in the medical management group not undergoing revascularization (p<.001). Although not designed to address short-term outcomes, there were no differences in the rates of early postoperative myocardial infarction, death, or hospital length of stay. It is also worth noting that 316 of the 510 patients who were ultimately randomized had undergone nuclear imaging studies, of which 226 (72%) had moderate to large reversible perfusion defects detected. These outcome data suggest that the presence of reversible perfusions defects is not in itself a reason for preoperative revascularization.

This well-designed study demonstrates that in the absence of unstable coronary syndromes, led main disease, severe aortic stenosis, or severely depressed led ventricular ejection fraction, there is no morbidity or mortality benefit to revascularization among patients with stable coronary artery disease prior to vascular surgery. Because vascular surgery is the highest risk category among non-cardiac procedures, it may be reasonable to extend these findings to lower risk surgeries as well, and in this sense this study is particularly relevant to consultative practice. While this study provides clear evidence on how to manage this cohort of patients, it remains unclear what the optimal strategy is to identify and manage those patients who were excluded from the trial. (DF)

Amiodarone or a Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrilator for Congestive Heart Failure

Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005 20;352:225-37.

Ventricular arrhythmias are the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in patients with systolic heart failure. Treatment with antiarrhythmic drug therapy has failed to improve survival in these patients, due to their proarrhythmic effects. Unlike other antiarrhythmics, amiodarone is a drug with low proarrhythmic effects. Some studies have suggested that amiodarone may be beneficial in patients with systolic heart failure. Conversely, several primary and secondary prevention trials have demonstrated that placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) confers a survival benefit in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. However, the role of ICDs in nonischemic heart failure remained unproven.

Bardy and colleagues developed the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCDHeFT) to evaluate the hypothesis that treatment with amiodarone or a shock-only, single-lead ICD would decrease death from any cause in a population of patients with mild to moderate heart failure. They randomly assigned 2521 patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or II heart failure (and a led ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less to conventional medical therapy plus placebo, conventional therapy plus treatment with amiodarone or conventional therapy plus a conservatively programmed, shock-only, single-lead ICD.

Fifty-two percent of patients had ischemic heart failure and 48% had nonischemic heart failure. Placebo and amiodarone were given in double-blind fashion. The primary endpoint was death from any cause with a median followup of 45.5 months. The results were as follows:

Placebo Group - 244 deaths (29% Death Rate)

Amiodarone Group - 240 deaths (28% Death Rate)

ICD Group - 182 deaths (22% Death Rate)

Patients treated with amiodarone had a similar risk of death as those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 1.06; 97.5% CI: 0.86–1.30; p=0.53). Patients implanted with an ICD had a 23% decreased risk of death when compared with those who received placebo (0.77; 97.5% CI: 0.62–0.96; p=.007). This resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 7.2% at 5 years. The authors concluded that in patients with NYHA class II or III heart failure and a LVEF of 35% or less, implantation of a single-lead, shock-only ICD reduced overall mortality by 23%, while treatment with amiodarone had no effect on survival. The benefit of ICD placement reached or approached significance in both the ischemic (hazard ratio .79, CI: 0.60–1.04, p= .05) and nonischemic (hazard ratio 0.73, CI: 0.50–1.07, p= 0.06) subgroups.

It is important to note that an additional subgroup analysis showed that ICD therapy had a significant survival benefit only in NYHA class II patients but not in NYHA class III patients. Amiodarone therapy had no benefit in class II patients and actually decreased survival in class III patients compared to those receiving placebo. In light of results from previous trials that demonstrated a greater survival benefit from ICD placement with worsening ejection fraction in patients with ischemic heart failure, the authors were unable to explain whether the differences in subclasses were biologically plausible.

This study is important for several reasons. First, it suggested that patients with systolic heart failure due to either ischemic or non ischemic causes would benefit from placement of an ICD. Second, these results support the conclusions of previous trials that demonstrate a survival advantage of ICD placement in patients with ischemic heart failure. Finally, this study also demonstrates that amiodarone therapy offers no survival benefit in this population of patients. (JL)

Clopidogrel versus Aspirin and Esomeprazole to Prevent Recurrent Ulcer Bleeding