User login

Hospital-Acquired Conditions & The Hospitalist

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

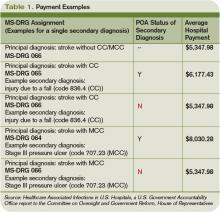

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.

“The rule changes regarding payment for HACs are only related to hospital payments, and to date, most physicians, including hospitalists, are not directly at financial risk,” says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine in the divisions of Health Care Policy Research and General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. “Although hospitalists have no financial skin in the game, there are plenty of reasons they would take an interest in addressing HACs in their hospital. In particular, they are often seen as the ‘go-to’ group for quality improvement in their hospitals.”

For example, some HM groups have been active in working with teams of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to address local policies and procedures on prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and DVT.

“This has certainly necessitated a team approach,” says Shaun Frost, MD, FHM, an SHM board member and regional medical director for Cogent Healthcare in St. Paul, Minn. “For many of the HACs that apply to our population of patients, the hospitalist alone cannot be expected to solely execute effective quality improvements. It takes a team effort in that regard, and one that includes many different disciplines.”

The Cogent-affiliated hospitalist group at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia formed a task force to address issues with catheter-associated UTI. One initiative focused on educating all providers involved in the proper care of the catheters and similar interventions. A secondary focus of the project was an inventory of current practices and procedures.

“It was discovered that we did not have an automatic stop order for Foley catheters, so in some situations, they were likely being left in longer than needed while nursing [staff] tried to contact a physician,” Dr. Frost explains. “We created standardized order sets that include criteria for continuing the catheter. Once the criteria are no longer applicable, nursing will be able to discontinue it.”

Although CMS has only recently turned the spotlight on HACs and never events, hospitalists have been heavily involved in the patient-safety arena for years. “It is not a new phenomenon that hospitalists work for healthcare delivery and healthcare system improvement,” Dr. Meddings says.

Hospital administration at Temple University Hospital recognized the HM group’s quality-improvement (QI) work, and has “specifically charged us with spreading the work we have done in patient safety to the entire house,” Dr. Frost says. “That speaks to the administration’s opinion of the power of the HM program to assist with institution-wide QI initiatives.”

Documentation Is Key

Beyond applying proven methods to avoid HACs, hospitalists can make a difference through documentation. If the hospitalist notes all conditions when the patient first presents to the hospital, additional comorbidity and complication payments should be made.

“The part that probably has the greatest impact on the day-to-day practice of a hospitalist is the increased importance of documentation throughout the hospital episode,” Dr. Meddings says. “If complications are occurring and they are not present in the chart, the coders may not recognize that it has occurred and will not know to include it in the bill. This can have an adverse impact on the hospital and its finances.”

Documentation issues can impact hospital payment in several ways:

- Hospitals might receive additional payment by default if certain HACs are described incorrectly or without sufficient detail (e.g., receiving overpayment because the physician did not indicate a UTI was in fact a catheter-associated UTI);

- As more attention is invested in documenting all conditions POA, hospitals might be coding more comorbidities overall than previously, which also will generate additional payment for hospitals as any POA condition is eligible for increased payment; and

- Hospitals might lose payment when admitting providers fail to adequately document the condition as POA (e.g., a pre-existing decubitus ulcer not detected until the second day of the hospital stay).

The descriptions to be used in coding are very detailed. UTIs, for example, have one code to document the POA assessment, another code to show that a UTI occurred, and a third code to indicate it was catheter-associated. Each code requires appropriate documentation in the chart (see Table 1, above).

The impact hospitalists have on care and payment is not the same across the HAC spectrum. For instance, documenting the presence of pressure ulcers might be easier than distinguishing colonization from infection in those admitted with in-dwelling urinary catheters. Others, such as DVT or vascular catheter-associated infections, are rarely POA unless they are part of the admitting diagnosis.

“This new focus on hospital-acquired conditions may work to the patient’s benefit,” Dr. Meddings says. “The inclusion of pressure ulcers has led to increased attention to skin exams on admission and preventive measures during hospitalizations. In the past, skin exams upon admission may have been given a lower priority, but that has changed.”

Dr. Meddings is concerned that the new rules could force the shifting of resources to areas where the hospital could lose money. If, when, and how many changes will actually take place is still up in the air. “Resource shifting is a concern whenever there is any sort of pay-for-performance attention directed toward one particular complication,” she says. “To balance this, many of the strategies hospitals used to prevent complications are not specific to just the diagnosis that is covered by the HAC.”

Dr. Meddings also hopes the new focus on preventable conditions will have a “halo effect” in the healthcare community. For instance, CMS mandating DVT prevention following orthopedic operations will, hopefully, result in a greater awareness of the problem in other susceptible patients.

POA Indicators

Since hospitalists often perform the initial patient history, physical, and other admission work, they are in the best position to find and document POA indicators (see Table 2, p. below). Proper notes on such things as UTIs present and the state of skin integrity are an important part of making sure the hospital is paid correctly for the care it provides.

Education on the specific definition of each potential HAC is required to help physicians avoid overtreatment of certain conditions, especially UTIs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines all UTIs as symptomatic. Therefore, the screening of all admitted patients, regardless of symptoms, is wasteful and unlikely to help the hospital’s bottom line.

“If you start screening everyone that comes through the door so you don’t miss any pre-existing UTIs, you are going to find a lot of asymptomatic colonization,” Dr. Wald says. “You are also going to spend a lot of money and time on studies and possibly treatments that may not yield many true infections. It is important that physicians know the definition of these HACs to help avoid needless interventions.”

Minimal Loss

Many hospital administrators and physicians were worried when the HAC program was first announced. Much of the stress and concern, however, seems to have dissipated. CMS estimated the HAC program would save Medicare $21 million in fiscal year 2009. Others, such as Peter McNair and colleagues writing in Health Affairs, suggest the actual impact is closer to $1.1 million.1 The CMS-projected impact of the HAC provision in fiscal-year 2009 was $21 million, out of more than $100 billion in payments.

“I think the HACs will not have a major impact because of the way payments are made,” says internist Robert Berenson, MD, a fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., who has studied Medicare policy issues extensively, and for two years was in charge of Medicare payment policies at the Health Care Finance Administration, the precursor to CMS. “Patients who have HACs often have another comorbidity that would kick them into a higher payment category regardless of the presence of a hospital-acquired complication. In the end, it is probably more symbolic and unlikely to make a major dent in hospital income—at least at this point.”

Another limitation to CMS nonpayment for HACs is the issue of deciding which conditions are truly preventable. Dr. Berenson questions the ability of the current system to identify many additional complications for which this approach will be feasible.

“CMS has laid out its strategy, suggesting that we should be able to continue increasing the number of conditions for which providers would be paid differently based on quality,” he says. “Many observers question whether there will ever be measurement tools that are robust enough, and there will be a wide agreement on the preventability of enough conditions that this initiative will go very far.”

Although hospitalists might not face a direct financial risk, they still have their hospitals’ best interest—and their reputations—on the line. “Hospitalists care about preventing complications,” Dr. Wald says. “We are very engaged in working with our hospitals to improve care, maximize quality, and minimize cost.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- McNair PD, Luft HS, Bindman AB. Medicare’s policy not to pay for treating hospital-acquired conditions: the impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1485-1493.

TOP IMAGE SOURCE: KAREEM RIZKHALLA/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.

“The rule changes regarding payment for HACs are only related to hospital payments, and to date, most physicians, including hospitalists, are not directly at financial risk,” says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine in the divisions of Health Care Policy Research and General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. “Although hospitalists have no financial skin in the game, there are plenty of reasons they would take an interest in addressing HACs in their hospital. In particular, they are often seen as the ‘go-to’ group for quality improvement in their hospitals.”

For example, some HM groups have been active in working with teams of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to address local policies and procedures on prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and DVT.

“This has certainly necessitated a team approach,” says Shaun Frost, MD, FHM, an SHM board member and regional medical director for Cogent Healthcare in St. Paul, Minn. “For many of the HACs that apply to our population of patients, the hospitalist alone cannot be expected to solely execute effective quality improvements. It takes a team effort in that regard, and one that includes many different disciplines.”

The Cogent-affiliated hospitalist group at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia formed a task force to address issues with catheter-associated UTI. One initiative focused on educating all providers involved in the proper care of the catheters and similar interventions. A secondary focus of the project was an inventory of current practices and procedures.

“It was discovered that we did not have an automatic stop order for Foley catheters, so in some situations, they were likely being left in longer than needed while nursing [staff] tried to contact a physician,” Dr. Frost explains. “We created standardized order sets that include criteria for continuing the catheter. Once the criteria are no longer applicable, nursing will be able to discontinue it.”

Although CMS has only recently turned the spotlight on HACs and never events, hospitalists have been heavily involved in the patient-safety arena for years. “It is not a new phenomenon that hospitalists work for healthcare delivery and healthcare system improvement,” Dr. Meddings says.

Hospital administration at Temple University Hospital recognized the HM group’s quality-improvement (QI) work, and has “specifically charged us with spreading the work we have done in patient safety to the entire house,” Dr. Frost says. “That speaks to the administration’s opinion of the power of the HM program to assist with institution-wide QI initiatives.”

Documentation Is Key

Beyond applying proven methods to avoid HACs, hospitalists can make a difference through documentation. If the hospitalist notes all conditions when the patient first presents to the hospital, additional comorbidity and complication payments should be made.

“The part that probably has the greatest impact on the day-to-day practice of a hospitalist is the increased importance of documentation throughout the hospital episode,” Dr. Meddings says. “If complications are occurring and they are not present in the chart, the coders may not recognize that it has occurred and will not know to include it in the bill. This can have an adverse impact on the hospital and its finances.”

Documentation issues can impact hospital payment in several ways:

- Hospitals might receive additional payment by default if certain HACs are described incorrectly or without sufficient detail (e.g., receiving overpayment because the physician did not indicate a UTI was in fact a catheter-associated UTI);

- As more attention is invested in documenting all conditions POA, hospitals might be coding more comorbidities overall than previously, which also will generate additional payment for hospitals as any POA condition is eligible for increased payment; and

- Hospitals might lose payment when admitting providers fail to adequately document the condition as POA (e.g., a pre-existing decubitus ulcer not detected until the second day of the hospital stay).

The descriptions to be used in coding are very detailed. UTIs, for example, have one code to document the POA assessment, another code to show that a UTI occurred, and a third code to indicate it was catheter-associated. Each code requires appropriate documentation in the chart (see Table 1, above).

The impact hospitalists have on care and payment is not the same across the HAC spectrum. For instance, documenting the presence of pressure ulcers might be easier than distinguishing colonization from infection in those admitted with in-dwelling urinary catheters. Others, such as DVT or vascular catheter-associated infections, are rarely POA unless they are part of the admitting diagnosis.

“This new focus on hospital-acquired conditions may work to the patient’s benefit,” Dr. Meddings says. “The inclusion of pressure ulcers has led to increased attention to skin exams on admission and preventive measures during hospitalizations. In the past, skin exams upon admission may have been given a lower priority, but that has changed.”

Dr. Meddings is concerned that the new rules could force the shifting of resources to areas where the hospital could lose money. If, when, and how many changes will actually take place is still up in the air. “Resource shifting is a concern whenever there is any sort of pay-for-performance attention directed toward one particular complication,” she says. “To balance this, many of the strategies hospitals used to prevent complications are not specific to just the diagnosis that is covered by the HAC.”

Dr. Meddings also hopes the new focus on preventable conditions will have a “halo effect” in the healthcare community. For instance, CMS mandating DVT prevention following orthopedic operations will, hopefully, result in a greater awareness of the problem in other susceptible patients.

POA Indicators

Since hospitalists often perform the initial patient history, physical, and other admission work, they are in the best position to find and document POA indicators (see Table 2, p. below). Proper notes on such things as UTIs present and the state of skin integrity are an important part of making sure the hospital is paid correctly for the care it provides.

Education on the specific definition of each potential HAC is required to help physicians avoid overtreatment of certain conditions, especially UTIs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines all UTIs as symptomatic. Therefore, the screening of all admitted patients, regardless of symptoms, is wasteful and unlikely to help the hospital’s bottom line.

“If you start screening everyone that comes through the door so you don’t miss any pre-existing UTIs, you are going to find a lot of asymptomatic colonization,” Dr. Wald says. “You are also going to spend a lot of money and time on studies and possibly treatments that may not yield many true infections. It is important that physicians know the definition of these HACs to help avoid needless interventions.”

Minimal Loss

Many hospital administrators and physicians were worried when the HAC program was first announced. Much of the stress and concern, however, seems to have dissipated. CMS estimated the HAC program would save Medicare $21 million in fiscal year 2009. Others, such as Peter McNair and colleagues writing in Health Affairs, suggest the actual impact is closer to $1.1 million.1 The CMS-projected impact of the HAC provision in fiscal-year 2009 was $21 million, out of more than $100 billion in payments.

“I think the HACs will not have a major impact because of the way payments are made,” says internist Robert Berenson, MD, a fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., who has studied Medicare policy issues extensively, and for two years was in charge of Medicare payment policies at the Health Care Finance Administration, the precursor to CMS. “Patients who have HACs often have another comorbidity that would kick them into a higher payment category regardless of the presence of a hospital-acquired complication. In the end, it is probably more symbolic and unlikely to make a major dent in hospital income—at least at this point.”

Another limitation to CMS nonpayment for HACs is the issue of deciding which conditions are truly preventable. Dr. Berenson questions the ability of the current system to identify many additional complications for which this approach will be feasible.

“CMS has laid out its strategy, suggesting that we should be able to continue increasing the number of conditions for which providers would be paid differently based on quality,” he says. “Many observers question whether there will ever be measurement tools that are robust enough, and there will be a wide agreement on the preventability of enough conditions that this initiative will go very far.”

Although hospitalists might not face a direct financial risk, they still have their hospitals’ best interest—and their reputations—on the line. “Hospitalists care about preventing complications,” Dr. Wald says. “We are very engaged in working with our hospitals to improve care, maximize quality, and minimize cost.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- McNair PD, Luft HS, Bindman AB. Medicare’s policy not to pay for treating hospital-acquired conditions: the impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1485-1493.

TOP IMAGE SOURCE: KAREEM RIZKHALLA/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.

“The rule changes regarding payment for HACs are only related to hospital payments, and to date, most physicians, including hospitalists, are not directly at financial risk,” says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine in the divisions of Health Care Policy Research and General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. “Although hospitalists have no financial skin in the game, there are plenty of reasons they would take an interest in addressing HACs in their hospital. In particular, they are often seen as the ‘go-to’ group for quality improvement in their hospitals.”

For example, some HM groups have been active in working with teams of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to address local policies and procedures on prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and DVT.

“This has certainly necessitated a team approach,” says Shaun Frost, MD, FHM, an SHM board member and regional medical director for Cogent Healthcare in St. Paul, Minn. “For many of the HACs that apply to our population of patients, the hospitalist alone cannot be expected to solely execute effective quality improvements. It takes a team effort in that regard, and one that includes many different disciplines.”

The Cogent-affiliated hospitalist group at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia formed a task force to address issues with catheter-associated UTI. One initiative focused on educating all providers involved in the proper care of the catheters and similar interventions. A secondary focus of the project was an inventory of current practices and procedures.

“It was discovered that we did not have an automatic stop order for Foley catheters, so in some situations, they were likely being left in longer than needed while nursing [staff] tried to contact a physician,” Dr. Frost explains. “We created standardized order sets that include criteria for continuing the catheter. Once the criteria are no longer applicable, nursing will be able to discontinue it.”

Although CMS has only recently turned the spotlight on HACs and never events, hospitalists have been heavily involved in the patient-safety arena for years. “It is not a new phenomenon that hospitalists work for healthcare delivery and healthcare system improvement,” Dr. Meddings says.

Hospital administration at Temple University Hospital recognized the HM group’s quality-improvement (QI) work, and has “specifically charged us with spreading the work we have done in patient safety to the entire house,” Dr. Frost says. “That speaks to the administration’s opinion of the power of the HM program to assist with institution-wide QI initiatives.”

Documentation Is Key

Beyond applying proven methods to avoid HACs, hospitalists can make a difference through documentation. If the hospitalist notes all conditions when the patient first presents to the hospital, additional comorbidity and complication payments should be made.

“The part that probably has the greatest impact on the day-to-day practice of a hospitalist is the increased importance of documentation throughout the hospital episode,” Dr. Meddings says. “If complications are occurring and they are not present in the chart, the coders may not recognize that it has occurred and will not know to include it in the bill. This can have an adverse impact on the hospital and its finances.”

Documentation issues can impact hospital payment in several ways:

- Hospitals might receive additional payment by default if certain HACs are described incorrectly or without sufficient detail (e.g., receiving overpayment because the physician did not indicate a UTI was in fact a catheter-associated UTI);

- As more attention is invested in documenting all conditions POA, hospitals might be coding more comorbidities overall than previously, which also will generate additional payment for hospitals as any POA condition is eligible for increased payment; and

- Hospitals might lose payment when admitting providers fail to adequately document the condition as POA (e.g., a pre-existing decubitus ulcer not detected until the second day of the hospital stay).

The descriptions to be used in coding are very detailed. UTIs, for example, have one code to document the POA assessment, another code to show that a UTI occurred, and a third code to indicate it was catheter-associated. Each code requires appropriate documentation in the chart (see Table 1, above).

The impact hospitalists have on care and payment is not the same across the HAC spectrum. For instance, documenting the presence of pressure ulcers might be easier than distinguishing colonization from infection in those admitted with in-dwelling urinary catheters. Others, such as DVT or vascular catheter-associated infections, are rarely POA unless they are part of the admitting diagnosis.

“This new focus on hospital-acquired conditions may work to the patient’s benefit,” Dr. Meddings says. “The inclusion of pressure ulcers has led to increased attention to skin exams on admission and preventive measures during hospitalizations. In the past, skin exams upon admission may have been given a lower priority, but that has changed.”

Dr. Meddings is concerned that the new rules could force the shifting of resources to areas where the hospital could lose money. If, when, and how many changes will actually take place is still up in the air. “Resource shifting is a concern whenever there is any sort of pay-for-performance attention directed toward one particular complication,” she says. “To balance this, many of the strategies hospitals used to prevent complications are not specific to just the diagnosis that is covered by the HAC.”

Dr. Meddings also hopes the new focus on preventable conditions will have a “halo effect” in the healthcare community. For instance, CMS mandating DVT prevention following orthopedic operations will, hopefully, result in a greater awareness of the problem in other susceptible patients.

POA Indicators

Since hospitalists often perform the initial patient history, physical, and other admission work, they are in the best position to find and document POA indicators (see Table 2, p. below). Proper notes on such things as UTIs present and the state of skin integrity are an important part of making sure the hospital is paid correctly for the care it provides.

Education on the specific definition of each potential HAC is required to help physicians avoid overtreatment of certain conditions, especially UTIs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines all UTIs as symptomatic. Therefore, the screening of all admitted patients, regardless of symptoms, is wasteful and unlikely to help the hospital’s bottom line.

“If you start screening everyone that comes through the door so you don’t miss any pre-existing UTIs, you are going to find a lot of asymptomatic colonization,” Dr. Wald says. “You are also going to spend a lot of money and time on studies and possibly treatments that may not yield many true infections. It is important that physicians know the definition of these HACs to help avoid needless interventions.”

Minimal Loss

Many hospital administrators and physicians were worried when the HAC program was first announced. Much of the stress and concern, however, seems to have dissipated. CMS estimated the HAC program would save Medicare $21 million in fiscal year 2009. Others, such as Peter McNair and colleagues writing in Health Affairs, suggest the actual impact is closer to $1.1 million.1 The CMS-projected impact of the HAC provision in fiscal-year 2009 was $21 million, out of more than $100 billion in payments.

“I think the HACs will not have a major impact because of the way payments are made,” says internist Robert Berenson, MD, a fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., who has studied Medicare policy issues extensively, and for two years was in charge of Medicare payment policies at the Health Care Finance Administration, the precursor to CMS. “Patients who have HACs often have another comorbidity that would kick them into a higher payment category regardless of the presence of a hospital-acquired complication. In the end, it is probably more symbolic and unlikely to make a major dent in hospital income—at least at this point.”

Another limitation to CMS nonpayment for HACs is the issue of deciding which conditions are truly preventable. Dr. Berenson questions the ability of the current system to identify many additional complications for which this approach will be feasible.

“CMS has laid out its strategy, suggesting that we should be able to continue increasing the number of conditions for which providers would be paid differently based on quality,” he says. “Many observers question whether there will ever be measurement tools that are robust enough, and there will be a wide agreement on the preventability of enough conditions that this initiative will go very far.”

Although hospitalists might not face a direct financial risk, they still have their hospitals’ best interest—and their reputations—on the line. “Hospitalists care about preventing complications,” Dr. Wald says. “We are very engaged in working with our hospitals to improve care, maximize quality, and minimize cost.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- McNair PD, Luft HS, Bindman AB. Medicare’s policy not to pay for treating hospital-acquired conditions: the impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1485-1493.

TOP IMAGE SOURCE: KAREEM RIZKHALLA/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

HM10 PREVIEW: Center Stage

Timing is everything, and SHM’s 13th annual conference—April 8-11 in Washington, D.C.—is happening at just the right time.

“It’s pretty exciting that we’re coming to Washington this year with all the activity in healthcare reform,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

SHM officials say HM10, at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just minutes outside the nation’s capital, is on track to be the best-attended meeting in the group’s history, a tough task given that HM09 in Chicago sold out to the tune of more than 2,000 hospitalists. HM10 will introduce new features for attendees: added pre-courses, the induction of the first classes of Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine and Master Fellows in Hospital Medicine, an expanded research and innovation platform, and a series of more than 90 educational sessions, including a new focus on limited-seating workshops.

“For the first time since we have been having an annual meeting, we will actually have what we call workshops that were actually peer-reviewed and selected as part of a competitive process,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “We had a competitive submission process for these workshops. We had over 90 submissions and we selected approximately 25 workshops to be presented.”

Paul Levy, president and CEO at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, will deliver HM10’s keynote address at 9 a.m. Friday, April 9. Levy has a national reputation as a quality-improvement (QI) and patient-safety innovator, and has titled his presentation “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Hospital of the Future.”

“It's a classic discussion on how you do process improvement,” Levy explains in an in-depth Q&A on p. 6. “How do you standardize care? Once you standardize care ... how do you measure that? Hospitalists are in an excellent position to do that because they work on all of the different floors of their hospitals.”

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com), will address the group—as has become custom—at noon Sunday. His focus will be “How Healthcare Reform Changes the Hospitalist Field … And Vice Versa.”

Attendees are encouraged to meet visiting professor Mark Zeidel, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel. Dr. Zeidel will be a featured part of the Best of the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) presentations. He will lead rounds during the poster sessions.

SHM officials say the speakers, educational opportunities, and new offerings continue to draw larger and larger crowds, despite the financial straits many HM groups face today.

“Even though there are travel budget cuts and education budget cuts, the one meeting that hospitalists continue to go to is SHM’s annual conference,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “That’s where they get their education, and, probably almost as importantly, is the networking aspect.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

Timing is everything, and SHM’s 13th annual conference—April 8-11 in Washington, D.C.—is happening at just the right time.

“It’s pretty exciting that we’re coming to Washington this year with all the activity in healthcare reform,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

SHM officials say HM10, at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just minutes outside the nation’s capital, is on track to be the best-attended meeting in the group’s history, a tough task given that HM09 in Chicago sold out to the tune of more than 2,000 hospitalists. HM10 will introduce new features for attendees: added pre-courses, the induction of the first classes of Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine and Master Fellows in Hospital Medicine, an expanded research and innovation platform, and a series of more than 90 educational sessions, including a new focus on limited-seating workshops.

“For the first time since we have been having an annual meeting, we will actually have what we call workshops that were actually peer-reviewed and selected as part of a competitive process,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “We had a competitive submission process for these workshops. We had over 90 submissions and we selected approximately 25 workshops to be presented.”

Paul Levy, president and CEO at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, will deliver HM10’s keynote address at 9 a.m. Friday, April 9. Levy has a national reputation as a quality-improvement (QI) and patient-safety innovator, and has titled his presentation “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Hospital of the Future.”

“It's a classic discussion on how you do process improvement,” Levy explains in an in-depth Q&A on p. 6. “How do you standardize care? Once you standardize care ... how do you measure that? Hospitalists are in an excellent position to do that because they work on all of the different floors of their hospitals.”

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com), will address the group—as has become custom—at noon Sunday. His focus will be “How Healthcare Reform Changes the Hospitalist Field … And Vice Versa.”

Attendees are encouraged to meet visiting professor Mark Zeidel, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel. Dr. Zeidel will be a featured part of the Best of the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) presentations. He will lead rounds during the poster sessions.

SHM officials say the speakers, educational opportunities, and new offerings continue to draw larger and larger crowds, despite the financial straits many HM groups face today.

“Even though there are travel budget cuts and education budget cuts, the one meeting that hospitalists continue to go to is SHM’s annual conference,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “That’s where they get their education, and, probably almost as importantly, is the networking aspect.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

Timing is everything, and SHM’s 13th annual conference—April 8-11 in Washington, D.C.—is happening at just the right time.

“It’s pretty exciting that we’re coming to Washington this year with all the activity in healthcare reform,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

SHM officials say HM10, at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just minutes outside the nation’s capital, is on track to be the best-attended meeting in the group’s history, a tough task given that HM09 in Chicago sold out to the tune of more than 2,000 hospitalists. HM10 will introduce new features for attendees: added pre-courses, the induction of the first classes of Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine and Master Fellows in Hospital Medicine, an expanded research and innovation platform, and a series of more than 90 educational sessions, including a new focus on limited-seating workshops.

“For the first time since we have been having an annual meeting, we will actually have what we call workshops that were actually peer-reviewed and selected as part of a competitive process,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “We had a competitive submission process for these workshops. We had over 90 submissions and we selected approximately 25 workshops to be presented.”

Paul Levy, president and CEO at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, will deliver HM10’s keynote address at 9 a.m. Friday, April 9. Levy has a national reputation as a quality-improvement (QI) and patient-safety innovator, and has titled his presentation “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Hospital of the Future.”

“It's a classic discussion on how you do process improvement,” Levy explains in an in-depth Q&A on p. 6. “How do you standardize care? Once you standardize care ... how do you measure that? Hospitalists are in an excellent position to do that because they work on all of the different floors of their hospitals.”

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachtersworld.com), will address the group—as has become custom—at noon Sunday. His focus will be “How Healthcare Reform Changes the Hospitalist Field … And Vice Versa.”

Attendees are encouraged to meet visiting professor Mark Zeidel, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel. Dr. Zeidel will be a featured part of the Best of the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) presentations. He will lead rounds during the poster sessions.

SHM officials say the speakers, educational opportunities, and new offerings continue to draw larger and larger crowds, despite the financial straits many HM groups face today.

“Even though there are travel budget cuts and education budget cuts, the one meeting that hospitalists continue to go to is SHM’s annual conference,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “That’s where they get their education, and, probably almost as importantly, is the networking aspect.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

Perioperative Medicine Summit 2010

Summit Director:

Amir K. Jaffer, MD

Contents

Abstract 1: Venous thromboembolism after total hip and knee replacement in older adults with single and co-occurring comorbidities

Alok Kapoor, MD, MSc; A. Labonte; M. Winter; J.B. Segal; R.A. Silliman; J.N. Katz; E. Losina; and D.R. Berlowitz

Abstract 2: Are there consequences of discontinuing angiotensin system inhibitors preoperatively in ambulatory and same-day admission patients?

Vasudha Goel, MBBS; David Rahmani, BS; Roy Braid, BS; Dmitry Rozin, BS; and Rebecca Twersky, MD, MPH

Abstract 3: Residents’ knowledge of ACC/AHA guidelines for preoperative cardiac evaluation is limited

BobbieJean Sweitzer, MD; Michael Vigoda, MD, MBA; Nikola Milokjic; Ben Boedeker, DVM, MD, PhD, MBA; Kip D. Robinson, MD, FACP; Michael A. Pilla, MD; Robert Gaiser, MD; Angela F. Edwards, MD; Ronald P. Olson, MD; Matthew D. Caldwell, MD; Shawn T. Beaman, MD; Jeffrey A. Green, MD; Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH; Marsha L. Wakefield, MD; Praveen Kalra, MD; David M. Feinstein, MD; Deborah C. Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA); Gail Van Norman; Gary E. Loyd, MD, MMM; Paul W. Kranner, MD; Stevin Dubin, MD; Sunil Eappen, MD; Sergio D. Bergese, MD; Suzanne Karan, MD; James R. Rowbottom, MD, FCCP; and Keith Candiotti, MD

Abstract 4: Descriptive perioperative BNP and CRP in vascular surgery patients

Thomas Barrett, MD, MCR, and Rebecca Duby, BS

Abstract 5: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of intraoperative bleeding

Adriana Oprea, MD, and Paula Zimbrean, MD

Abstract 6: Incidence and nature of postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing noncardiac surgery

Roop Kaw, MD; Vinay Pasupuleti, MBBS, PhD; Esteban Walker, PhD; Anuradha Ramaswamy, MD; Thadeo Catacutan, MD; and Nancy Foldvary, DO

Abstract 7: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism in joint replacement surgery

William Ho, MBBS; Brendan Flaim, MBBS, FRACP; and Andrea Chan, MBBS, FRACP

Abstract 8: Risk prediction models for cardiac morbidity and mortality in noncardiac surgery: A systematic review of the literature

Ramani Moonesinghe, MBBS, MRCP, FRCA; Kathy Rowan, PhD; Judith Hulf, CBE, FRCA; Michael G. Mythen, MD, FRCA; and Michael P.W. Grocott, MD, FRCA

Abstract 9: Economic aspects of preoperative testing

Gerhard Fritsch, MD; Maria Flamm, MD; Josef Seer, MD; and Andreas Soennichsen, MD

Abstract 10: Postoperative myocardial infarction and in-hospital mortality predictors in patients undergoing rlective noncardiac surgery

Anitha Rajamanickam, MD; Ali Usmani, MD; Jelica Janicijevic, MD; Preethi Patel, MD; Eric Hixson; Omeed Zardkoohi, MD; Michael Pecic; Changhong Yu; Michael Kattan, PhD; Sagar Kalahasti, MD; and Mina K. Chung, MD

Abstract 11: Incidence and predictors of postoperative heart failure in patients undergoing elective noncardiac surgery

Anitha Rajamanickam, MD; Ali Usmani, MD; Jelica Janicijevic, MD; Preethi Patel, MD; Eric Hixson; Omeed Zardkoohi, MD; Michael Pecic; Changhong Yu; Michael Kattan, PhD; Sagar Kalahasti, MD; and Mina K. Chung, MD

Abstract 12: Predictors of length of stay in patients undergoing total knee replacement surgery

Vishal Sehgal, MD; Pardeep Bansal, MD; Praveen Reddy, MD; Vishal Sharma, MD; Rajendra Palepu, MD; Linda Thomas, MD; and Jeremiah Eagan, MD

Abstract 13: Analysis of surgeon utilization of the Preoperative Assessment Communication Education (PACE) center in the pediatric population

Lisa Price Stevens, MD, and Ezinne Akamiro, BA, MD/MHA

Abstract 14: Use of the BATHE method to increase satisfaction amongst patients undergoing cardiac and major vascular operations

Samuel DeMaria, MD; Anthony P. DeMaria, MA; Menachem Weiner, MD; and George Silvay, MD

Abstract 15: Indication for surgery predicts long-term but not in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing lower extremity bypass vascular surgery

Brigid C. Flynn, MD; Michael Mazzeffi , MD; Carol Bodian, PhD; and Vivek Moitra, MD

Abstract 16: Research and outcomes on analgesia and nociception during surgery

Jinu Kim, MD; Tehila Adams, MD; Deepak Sreedharan, MD; Shanti Raju, MD; and Henry Bennett, PhD

Abstract 17: A snapshot survey of fluid prescribing

Helen Grote, MD; Luke Evans, MRCS; Abdel Omer, MD, PhD, FRCS; and Rob Lewis, MD, FRCA

Abstract 18: Predictors of difficult intubation with the video laryngoscope

Dario Galante, MD

Abstract 19: Use of technology to improve operational efficiency

Lucy Duffy, RN, MA, and Rita Lanaras, RN, BS, CNOR

Abstract 20: The ASA physical status score for the nonanesthesiologist

Adriana Oprea, MD, and David Silverman, MD

Abstract 21: Development of a shared multidisciplinary electronic preanesthetic record

Meghan Tadel, MD; R. Boyer, DO, MS; N. Smith; and P. Kallas, MD

Abstract 22: Development of a patient selection protocol prior to robotic radical prostatectomy (RRP) in the Preoperative Assessment Unit (PAU)

James Dyer, MD

Abstract 23: Protocol-driven preoperative testing in the Preoperative Assessment Unit (PAU): Which patients should receive a resting transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) prior to elective noncardiac surgery?

James Dyer, MD

Abstract 24: High-risk preoperative assessment for elective orthopedic surgery patients

Terrence Adam, MD, PhD; Connie Parenti, MD; Terence Gioe, MD; Karen Ringsred, MD; and Joseph Wels, MD

Abstract 25: A novel use of web-based software to efficiently triage presurgical patients based on perioperative risk: A pilot

Alicia Kalamas, MD

Abstract 26: Value of a specialized clinic for day admission surgery for cardiac and major vascular operations

George Silvay, MD, PhD; Samuel DeMaria, MD; Marietta dePerio, NP, CCRN; Ellen Hughes, MA, RN; Samantha Silvay; Marina Krol, PhD; Brigid C. Flynn, MD; and David L. Reich, MD

Abstract 27: Preoperative evaluation for parathyroidectomy—rule out pheochromocytoma

Rubin Bahuva, MD; Sudhir Manda, MD; and Saurabh Kandpal, MD

Abstract 28: Should we stop the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene prior to surgery?

Vesselin Dimov, MD; Tarek Hamieh, MD; and Ajay Kumar, MD

Abstract 29: Should mesalamine be stopped prior to noncardiac surgery to avoid bleeding complications?

Vesselin Dimov, MD; Tarek Hamieh, MD; and Ajay Kumar, MD

Abstract 30: Thyroidectomy: Perioperative management of acute thyroid storm

Stephen VanHaerents, MD, and Aashish A. Shah, MD

Abstract 31: Core competencies: Not just for the ACGME—but for successful and ethical perioperative management of a young respiratory cripple

Deborah Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA); Misako P. Sakamaki, MD; and Slawomir P. Oleszak, MD

Abstract 32: ‘If I have to be transfused I only want my wwn blood, or blood from family members’—what is best-practice advice to be given in the preoperative clinic?

Deborah Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA), and Joseph L. Conrad, MD

Abstract 33: Prolonged QTc and hypokalemia: A bad combination before surgery

Chadi Alraies, MD, and Abdul Hamid Alraiyes, MD

Abstract 34: Perioperative management of a parturient with neuromyelitis optica

Neeti Sadana, MD; Michael Orosco, MD; Michaela Farber, MD; and Scott Segal, MD

Abstract 35: ‘High’-pertension

Anuradha Ramaswamy, MD, and Franklin A. Michota, Jr., MD

Abstract 36: Perioperative care in neuromuscular scoliosis

Saurabh Basu Kandpal, MD, and Priya Baronia, MD

Summit Director:

Amir K. Jaffer, MD

Contents

Abstract 1: Venous thromboembolism after total hip and knee replacement in older adults with single and co-occurring comorbidities

Alok Kapoor, MD, MSc; A. Labonte; M. Winter; J.B. Segal; R.A. Silliman; J.N. Katz; E. Losina; and D.R. Berlowitz

Abstract 2: Are there consequences of discontinuing angiotensin system inhibitors preoperatively in ambulatory and same-day admission patients?

Vasudha Goel, MBBS; David Rahmani, BS; Roy Braid, BS; Dmitry Rozin, BS; and Rebecca Twersky, MD, MPH

Abstract 3: Residents’ knowledge of ACC/AHA guidelines for preoperative cardiac evaluation is limited

BobbieJean Sweitzer, MD; Michael Vigoda, MD, MBA; Nikola Milokjic; Ben Boedeker, DVM, MD, PhD, MBA; Kip D. Robinson, MD, FACP; Michael A. Pilla, MD; Robert Gaiser, MD; Angela F. Edwards, MD; Ronald P. Olson, MD; Matthew D. Caldwell, MD; Shawn T. Beaman, MD; Jeffrey A. Green, MD; Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH; Marsha L. Wakefield, MD; Praveen Kalra, MD; David M. Feinstein, MD; Deborah C. Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA); Gail Van Norman; Gary E. Loyd, MD, MMM; Paul W. Kranner, MD; Stevin Dubin, MD; Sunil Eappen, MD; Sergio D. Bergese, MD; Suzanne Karan, MD; James R. Rowbottom, MD, FCCP; and Keith Candiotti, MD

Abstract 4: Descriptive perioperative BNP and CRP in vascular surgery patients

Thomas Barrett, MD, MCR, and Rebecca Duby, BS

Abstract 5: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of intraoperative bleeding

Adriana Oprea, MD, and Paula Zimbrean, MD

Abstract 6: Incidence and nature of postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing noncardiac surgery

Roop Kaw, MD; Vinay Pasupuleti, MBBS, PhD; Esteban Walker, PhD; Anuradha Ramaswamy, MD; Thadeo Catacutan, MD; and Nancy Foldvary, DO

Abstract 7: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism in joint replacement surgery

William Ho, MBBS; Brendan Flaim, MBBS, FRACP; and Andrea Chan, MBBS, FRACP

Abstract 8: Risk prediction models for cardiac morbidity and mortality in noncardiac surgery: A systematic review of the literature

Ramani Moonesinghe, MBBS, MRCP, FRCA; Kathy Rowan, PhD; Judith Hulf, CBE, FRCA; Michael G. Mythen, MD, FRCA; and Michael P.W. Grocott, MD, FRCA

Abstract 9: Economic aspects of preoperative testing

Gerhard Fritsch, MD; Maria Flamm, MD; Josef Seer, MD; and Andreas Soennichsen, MD

Abstract 10: Postoperative myocardial infarction and in-hospital mortality predictors in patients undergoing rlective noncardiac surgery

Anitha Rajamanickam, MD; Ali Usmani, MD; Jelica Janicijevic, MD; Preethi Patel, MD; Eric Hixson; Omeed Zardkoohi, MD; Michael Pecic; Changhong Yu; Michael Kattan, PhD; Sagar Kalahasti, MD; and Mina K. Chung, MD

Abstract 11: Incidence and predictors of postoperative heart failure in patients undergoing elective noncardiac surgery

Anitha Rajamanickam, MD; Ali Usmani, MD; Jelica Janicijevic, MD; Preethi Patel, MD; Eric Hixson; Omeed Zardkoohi, MD; Michael Pecic; Changhong Yu; Michael Kattan, PhD; Sagar Kalahasti, MD; and Mina K. Chung, MD

Abstract 12: Predictors of length of stay in patients undergoing total knee replacement surgery

Vishal Sehgal, MD; Pardeep Bansal, MD; Praveen Reddy, MD; Vishal Sharma, MD; Rajendra Palepu, MD; Linda Thomas, MD; and Jeremiah Eagan, MD

Abstract 13: Analysis of surgeon utilization of the Preoperative Assessment Communication Education (PACE) center in the pediatric population

Lisa Price Stevens, MD, and Ezinne Akamiro, BA, MD/MHA

Abstract 14: Use of the BATHE method to increase satisfaction amongst patients undergoing cardiac and major vascular operations

Samuel DeMaria, MD; Anthony P. DeMaria, MA; Menachem Weiner, MD; and George Silvay, MD

Abstract 15: Indication for surgery predicts long-term but not in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing lower extremity bypass vascular surgery

Brigid C. Flynn, MD; Michael Mazzeffi , MD; Carol Bodian, PhD; and Vivek Moitra, MD

Abstract 16: Research and outcomes on analgesia and nociception during surgery

Jinu Kim, MD; Tehila Adams, MD; Deepak Sreedharan, MD; Shanti Raju, MD; and Henry Bennett, PhD

Abstract 17: A snapshot survey of fluid prescribing

Helen Grote, MD; Luke Evans, MRCS; Abdel Omer, MD, PhD, FRCS; and Rob Lewis, MD, FRCA

Abstract 18: Predictors of difficult intubation with the video laryngoscope

Dario Galante, MD

Abstract 19: Use of technology to improve operational efficiency

Lucy Duffy, RN, MA, and Rita Lanaras, RN, BS, CNOR

Abstract 20: The ASA physical status score for the nonanesthesiologist

Adriana Oprea, MD, and David Silverman, MD

Abstract 21: Development of a shared multidisciplinary electronic preanesthetic record

Meghan Tadel, MD; R. Boyer, DO, MS; N. Smith; and P. Kallas, MD

Abstract 22: Development of a patient selection protocol prior to robotic radical prostatectomy (RRP) in the Preoperative Assessment Unit (PAU)

James Dyer, MD

Abstract 23: Protocol-driven preoperative testing in the Preoperative Assessment Unit (PAU): Which patients should receive a resting transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) prior to elective noncardiac surgery?

James Dyer, MD

Abstract 24: High-risk preoperative assessment for elective orthopedic surgery patients

Terrence Adam, MD, PhD; Connie Parenti, MD; Terence Gioe, MD; Karen Ringsred, MD; and Joseph Wels, MD

Abstract 25: A novel use of web-based software to efficiently triage presurgical patients based on perioperative risk: A pilot

Alicia Kalamas, MD

Abstract 26: Value of a specialized clinic for day admission surgery for cardiac and major vascular operations

George Silvay, MD, PhD; Samuel DeMaria, MD; Marietta dePerio, NP, CCRN; Ellen Hughes, MA, RN; Samantha Silvay; Marina Krol, PhD; Brigid C. Flynn, MD; and David L. Reich, MD

Abstract 27: Preoperative evaluation for parathyroidectomy—rule out pheochromocytoma

Rubin Bahuva, MD; Sudhir Manda, MD; and Saurabh Kandpal, MD

Abstract 28: Should we stop the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene prior to surgery?

Vesselin Dimov, MD; Tarek Hamieh, MD; and Ajay Kumar, MD

Abstract 29: Should mesalamine be stopped prior to noncardiac surgery to avoid bleeding complications?

Vesselin Dimov, MD; Tarek Hamieh, MD; and Ajay Kumar, MD

Abstract 30: Thyroidectomy: Perioperative management of acute thyroid storm

Stephen VanHaerents, MD, and Aashish A. Shah, MD

Abstract 31: Core competencies: Not just for the ACGME—but for successful and ethical perioperative management of a young respiratory cripple

Deborah Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA); Misako P. Sakamaki, MD; and Slawomir P. Oleszak, MD

Abstract 32: ‘If I have to be transfused I only want my wwn blood, or blood from family members’—what is best-practice advice to be given in the preoperative clinic?

Deborah Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA), and Joseph L. Conrad, MD

Abstract 33: Prolonged QTc and hypokalemia: A bad combination before surgery

Chadi Alraies, MD, and Abdul Hamid Alraiyes, MD

Abstract 34: Perioperative management of a parturient with neuromyelitis optica

Neeti Sadana, MD; Michael Orosco, MD; Michaela Farber, MD; and Scott Segal, MD

Abstract 35: ‘High’-pertension

Anuradha Ramaswamy, MD, and Franklin A. Michota, Jr., MD

Abstract 36: Perioperative care in neuromuscular scoliosis

Saurabh Basu Kandpal, MD, and Priya Baronia, MD

Summit Director:

Amir K. Jaffer, MD

Contents

Abstract 1: Venous thromboembolism after total hip and knee replacement in older adults with single and co-occurring comorbidities

Alok Kapoor, MD, MSc; A. Labonte; M. Winter; J.B. Segal; R.A. Silliman; J.N. Katz; E. Losina; and D.R. Berlowitz

Abstract 2: Are there consequences of discontinuing angiotensin system inhibitors preoperatively in ambulatory and same-day admission patients?

Vasudha Goel, MBBS; David Rahmani, BS; Roy Braid, BS; Dmitry Rozin, BS; and Rebecca Twersky, MD, MPH

Abstract 3: Residents’ knowledge of ACC/AHA guidelines for preoperative cardiac evaluation is limited

BobbieJean Sweitzer, MD; Michael Vigoda, MD, MBA; Nikola Milokjic; Ben Boedeker, DVM, MD, PhD, MBA; Kip D. Robinson, MD, FACP; Michael A. Pilla, MD; Robert Gaiser, MD; Angela F. Edwards, MD; Ronald P. Olson, MD; Matthew D. Caldwell, MD; Shawn T. Beaman, MD; Jeffrey A. Green, MD; Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH; Marsha L. Wakefield, MD; Praveen Kalra, MD; David M. Feinstein, MD; Deborah C. Richman, MBChB, FFA(SA); Gail Van Norman; Gary E. Loyd, MD, MMM; Paul W. Kranner, MD; Stevin Dubin, MD; Sunil Eappen, MD; Sergio D. Bergese, MD; Suzanne Karan, MD; James R. Rowbottom, MD, FCCP; and Keith Candiotti, MD

Abstract 4: Descriptive perioperative BNP and CRP in vascular surgery patients

Thomas Barrett, MD, MCR, and Rebecca Duby, BS

Abstract 5: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of intraoperative bleeding

Adriana Oprea, MD, and Paula Zimbrean, MD

Abstract 6: Incidence and nature of postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing noncardiac surgery

Roop Kaw, MD; Vinay Pasupuleti, MBBS, PhD; Esteban Walker, PhD; Anuradha Ramaswamy, MD; Thadeo Catacutan, MD; and Nancy Foldvary, DO

Abstract 7: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism in joint replacement surgery

William Ho, MBBS; Brendan Flaim, MBBS, FRACP; and Andrea Chan, MBBS, FRACP

Abstract 8: Risk prediction models for cardiac morbidity and mortality in noncardiac surgery: A systematic review of the literature

Ramani Moonesinghe, MBBS, MRCP, FRCA; Kathy Rowan, PhD; Judith Hulf, CBE, FRCA; Michael G. Mythen, MD, FRCA; and Michael P.W. Grocott, MD, FRCA

Abstract 9: Economic aspects of preoperative testing

Gerhard Fritsch, MD; Maria Flamm, MD; Josef Seer, MD; and Andreas Soennichsen, MD

Abstract 10: Postoperative myocardial infarction and in-hospital mortality predictors in patients undergoing rlective noncardiac surgery

Anitha Rajamanickam, MD; Ali Usmani, MD; Jelica Janicijevic, MD; Preethi Patel, MD; Eric Hixson; Omeed Zardkoohi, MD; Michael Pecic; Changhong Yu; Michael Kattan, PhD; Sagar Kalahasti, MD; and Mina K. Chung, MD

Abstract 11: Incidence and predictors of postoperative heart failure in patients undergoing elective noncardiac surgery

Anitha Rajamanickam, MD; Ali Usmani, MD; Jelica Janicijevic, MD; Preethi Patel, MD; Eric Hixson; Omeed Zardkoohi, MD; Michael Pecic; Changhong Yu; Michael Kattan, PhD; Sagar Kalahasti, MD; and Mina K. Chung, MD

Abstract 12: Predictors of length of stay in patients undergoing total knee replacement surgery

Vishal Sehgal, MD; Pardeep Bansal, MD; Praveen Reddy, MD; Vishal Sharma, MD; Rajendra Palepu, MD; Linda Thomas, MD; and Jeremiah Eagan, MD

Abstract 13: Analysis of surgeon utilization of the Preoperative Assessment Communication Education (PACE) center in the pediatric population

Lisa Price Stevens, MD, and Ezinne Akamiro, BA, MD/MHA

Abstract 14: Use of the BATHE method to increase satisfaction amongst patients undergoing cardiac and major vascular operations

Samuel DeMaria, MD; Anthony P. DeMaria, MA; Menachem Weiner, MD; and George Silvay, MD

Abstract 15: Indication for surgery predicts long-term but not in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing lower extremity bypass vascular surgery

Brigid C. Flynn, MD; Michael Mazzeffi , MD; Carol Bodian, PhD; and Vivek Moitra, MD

Abstract 16: Research and outcomes on analgesia and nociception during surgery

Jinu Kim, MD; Tehila Adams, MD; Deepak Sreedharan, MD; Shanti Raju, MD; and Henry Bennett, PhD

Abstract 17: A snapshot survey of fluid prescribing

Helen Grote, MD; Luke Evans, MRCS; Abdel Omer, MD, PhD, FRCS; and Rob Lewis, MD, FRCA

Abstract 18: Predictors of difficult intubation with the video laryngoscope

Dario Galante, MD

Abstract 19: Use of technology to improve operational efficiency

Lucy Duffy, RN, MA, and Rita Lanaras, RN, BS, CNOR

Abstract 20: The ASA physical status score for the nonanesthesiologist

Adriana Oprea, MD, and David Silverman, MD

Abstract 21: Development of a shared multidisciplinary electronic preanesthetic record

Meghan Tadel, MD; R. Boyer, DO, MS; N. Smith; and P. Kallas, MD

Abstract 22: Development of a patient selection protocol prior to robotic radical prostatectomy (RRP) in the Preoperative Assessment Unit (PAU)

James Dyer, MD

Abstract 23: Protocol-driven preoperative testing in the Preoperative Assessment Unit (PAU): Which patients should receive a resting transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) prior to elective noncardiac surgery?

James Dyer, MD