User login

Skin and soft-tissue infections: Classifying and treating a spectrum

Skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) are a common reason for presentation to outpatient practices, emergency rooms, and hospitals.1–5 They account for more than 14 million outpatient visits in the United States each year,1 and visits to the emergency room and admissions to the hospital for them are increasing.2,3 Hospital admissions for SSTIs increased by 29% from 2000 to 2004.3

MORE MRSA NOW, BUT STREPTOCOCCI ARE STILL COMMON

The increase in hospital admissions for SSTIs has been attributed to a rising number of infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).3–5

In addition, strains once seen mostly in the community and other strains that were associated with health care are now being seen more often in both settings. Clinical characteristics do not differ between community-acquired and health-care-associated MRSA, and therefore the distinction between the two is becoming less useful in guiding empiric therapy.6,7

After steadily increasing for several years, the incidence of MRSA has recently stabilized. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintains a surveillance program and a Web site on MRSA.8

COMPLICATED OR UNCOMPLICATED

The intent of the 1998 guideline was to provide not a clinical framework but rather a guide for industry in designing trials that would include similar groups of infections and therefore be relevant when compared with each other. In 2008, the Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee was convened,11 and subsequently, in August 2010, the FDA released a revision of the guide.12

The revised guidelines specifically exclude many diagnoses, such as bite wounds, bone and joint infections, necrotizing fasciitis, diabetic foot infections, decubitus ulcers, catheter site infections, myonecrosis, and ecthyma gangrenosum. Notably, the word “bacterial” in the title excludes mycobacterial and fungal infections from consideration. The diagnoses that are included include cellulitis, erysipelas, major cutaneous abscess, and burn infections. These are further specified to include 75 cm2 of redness, edema, or induration to standardize the extent of the infection—ie, the infection has to be at least this large or else it is not “complicated.”

The terms “complicated” and “uncomplicated” skin and skin structure infections persist and can be useful adjuncts in describing SSTIs.13–16 However, more specific descriptions of SSTIs based on pathogenesis are more useful to the clinician and are usually the basis for guidelines, such as for preventing surgical site infections or for reducing amputations in diabetic foot infections.

This review will focus on the general categories of SSTI and will not address surgical site infections, pressure ulcers, diabetic foot infections, perirectal wounds, or adjuvant therapies in severe SSTIs, such as negative pressure wound care (vacuum-assisted closure devices) and hyperbaric chambers.

OTHER DISEASES CAN MIMIC SSTIs

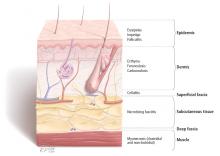

SSTIs vary broadly in their location and severity.

Although the classic presentation of erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness often signals infection, other diseases can mimic SSTIs. Common ones that should be included in the differential diagnosis include gout, thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis, contact dermatitis, carcinoma erysipeloides, drug eruption, and a foreign body reaction.17,18

CLUES FROM THE HISTORY

Wounds. Skin infections are usually precipitated by a break in the skin from a cut, laceration, excoriation, fungal infection, insect or animal bite, or puncture wound.

Impaired response. Patients with diabetes, renal failure, cirrhosis, chronic glucocorticoid use, history of organ transplantation, chronic immunosuppressive therapy, HIV infection, or malnourishment have impaired host responses to infection and are at risk for both more severe infections and recurrent infections. Immunocompromised hosts may also have atypical infections with opportunistic organisms such as Pseudomonas, Proteus, Serratia, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, and anaerobes. Close follow-up of these patients is warranted to ascertain appropriate response to therapy.19

Surgery that includes lymph node dissection or saphenous vein resection for coronary artery bypass can lead to impaired lymphatic drainage and edema, and therefore predisposes patients to SSTIs.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should include descriptions of the extent and location of erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness so that progression or resolution with treatment can be followed in detail.

Crepitus can be felt in gas-forming infections and raises the concern for necrotizing fasciitis and infection with anaerobic organisms such as Clostridium perfringens.

Necrosis can occur in brown recluse spider bites, venous snake bites, or group A streptococcal infections.

Fluctuance indicates fluid and a likely abscess that may need incision and drainage.

Purpura may be present in patients on anticoagulation therapy, but if it is accompanying an SSTI, it also raises the concern for the possibility of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, especially from streptococcal infections.

Bullae can be seen in impetigo caused by staphylococci or in infection with Vibrio vulnificus or Streptococcus pneumoniae.19

Systemic signs, in addition to fever, can include hypotension and tachycardia, which would prompt closer monitoring and possible hospitalization.

Lymphangitic spread also indicates severe infection.

LABORATORY STUDIES

Simple, localized SSTIs usually do not require laboratory evaluation. Jenkins et al21 recently demonstrated that by using an algorithm for the management of hospitalized patients with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, they could decrease resource utilization, including laboratory testing, without adversely affecting clinical outcome.

If patients have underlying disease or more extensive infection, then baseline chemistry values, a complete blood cell count, and the C-reactive protein level should be acquired.19 Laboratory findings that suggest more severe disease include low sodium, low bicarbonate (or an anion gap), and high creatinine levels; new anemia; a high or very low white blood cell count; and a high C-reactive protein level. A high C-reactive protein level has been associated with longer hospitalization.22

A score to estimate the risk of necrotizing fasciitis

This tool was developed retrospectively but has been validated prospectively. It has a high sensitivity and a positive predictive value of 92% in patients with a score of six points or more. Its specificity is also high, with a negative predictive value of 96%.20,24

Necrotizing fasciitis has a mortality rate of 23.5%, but this may be reduced to 10% with early detection and prompt surgical intervention.15 Since necrotizing fasciitis is very difficult to diagnose, clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion and use the LRINEC score to trigger early surgical evaluation. Surgical exploration is the only way to definitively diagnose necrotizing fasciitis.

Blood cultures in some cases

Blood cultures have a low yield and are usually not cost-effective, but they should be obtained in patients who have lymphedema, immune deficiency, fever, pain out of proportion to the findings on examination, tachycardia, or hypotension, as blood cultures are more likely to be positive in more serious infections and can help guide antimicrobial therapy. Blood cultures are also recommended in patients with infections involving specific anatomic sites, such as the mouth and eyes.19

Aspiration, swabs, incision and drainage

Fluid aspirated from abscesses and swabs of debrided ulcerated wounds should be sent for Gram stain and culture. Gram stain and culture have widely varying yields, from less than 5% to 40%, depending on the source and technique.19 Cultures were not routinely obtained before MRSA emerged, but knowing antimicrobial susceptibility is now important to guide antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, in cellulitis, swabs and aspirates of the leading edge have a low yield of around 10%.25 One prospective study of 25 hospitalized patients did report a higher yield of positive cultures in patients with fever or underlying disease,26 so aspirates may be used in selected cases. In small studies, the yield of punch biopsies was slightly better than that of needle aspirates and was as high as 20% to 30%.27

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging can be helpful in determining the depth of involvement. Plain radiography can reveal gas or periosteal inflammation and is especially helpful in diabetic foot infections. Ultrasonography can detect abscesses.

Both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are useful to image fascial planes, although MRI is more sensitive. However, in cases of suspected necrotizing fasciitis, imaging should not delay surgical evaluation and debridement or be used as the definitive study. Therefore, the practicality of CT and MRI can be limited.15,16

ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT FOR SSTIs IN OUTPATIENTS

For minor skin infections such as impetigo and secondarily infected skin lesions such as eczema, ulcers, or lacerations, mupirocin 2% topical ointment (Bactroban) can be effective.27

For a simple abscess or boil, incision and drainage is the primary treatment, and antibiotics are not needed.

For a complicated abscess or boil. Patients should be given oral or intravenous antibiotic therapy to cover MRSA and, depending on the severity, should be considered for hospitalization if the abscess is associated with severe disease, rapid progression in the presence of associated cellulitis, septic phlebitis, constitutional symptoms, comorbidity (including immunosuppression), or an abscess or boil in an area difficult to drain, such as the face, hands, or genitalia.27

For purulent cellulitis in outpatients, empiric therapy for community-acquired MRSA is recommended, pending culture results. Empiric therapy for streptococcal infection is likely unnecessary. For empiric coverage of community-acquired MRSA in purulent cellulitis, oral antibiotic options include clindamycin (Cleocin), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), doxycycline (Doryx), minocycline (Minocin), and linezolid (Zyvox).

For nonpurulent cellulitis in outpatients, empiric coverage for beta-hemolytic streptococci is warranted. Coverage for community-acquired MRSA should subsequently be added for patients who do not respond to beta-lactam therapy within 48 to 72 hours or who have chills, fever, a new abscess, increasing erythema, or uncontrolled pain.

Options for coverage of both beta-hemolytic streptococci and community-acquired MRSA for outpatient therapy include clindamycin on its own, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a tetracycline in combination with a beta-lactam, or linezolid on its own.

Increasing rates of resistance to clindamycin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in community-acquired MRSA may limit empiric treatment. In areas where resistance is prevalent, culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing may be required before starting one of these antibiotics.

The use of rifampin (Rifadin) as a single agent is not recommended because resistance is likely to develop. Also, rifampin is not useful as adjunctive therapy, as evidence does not support its efficacy.19,27,29

ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT FOR SSTIs IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

For hospitalized patients with a complicated or severe SSTI, empiric therapy for MRSA should be started pending culture results. FDA-approved options are vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin (Cubicin), tigecycline (Tygacil), and telavancin (Vibativ). Data on clindamycin are very limited in this population. A beta-lactam antibiotic such as cefazolin (Ancef) may be considered in hospitalized patients with nonpurulent cellulitis, and the regimen can be modified to MRSA-active therapy if there is no clinical response. Linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, and telavancin have adequate streptococcal coverage in addition to MRSA coverage.

Clindamycin is approved by the FDA for treating serious infections due to S aureus. It has excellent tissue penetration, particularly in bone and abscesses.

Clindamycin resistance in staphylococci can be either constitutive or inducible, and clinicians must be watchful for signs of resistance.

Diarrhea is the most common adverse effect and occurs in up to 20% of patients. Clostridium difficile colitis may occur more frequently with clindamycin than with other oral agents, but it has also has been reported with fluoroquinolones and can be associated with any antibiotic therapy.30

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is not FDA-approved for treating any staphylococcal infection. However, because 95% to 100% of community-acquired MRSA strains are susceptible to it in vitro, it has become an important option in the outpatient treatment of SSTIs. Caution is advised when using it in elderly patients, particularly those with chronic renal insufficiency, because of an increased risk of hyperkalemia.

Tetracyclines. Doxycycline is FDA-approved for treating SSTIs due to S aureus, although not specifically for MRSA. Minocycline may be an option even when strains are resistant to doxycycline, since it does not induce its own resistance as doxycycline does.

Tigecycline is a glycylcycline (a tetracycline derivative) and is FDA-approved in adults for complicated SSTIs and intra-abdominal infections. It has a large volume of distribution and achieves high concentrations in tissues and low concentrations in serum.

The FDA recently issued a warning to consider alternative agents in patients with serious infections because of higher rates of all-cause mortality noted in phase III and phase IV clinical trials. Due to this warning and the availability of multiple alternatives active against MRSA, tigecycline was not included in the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines.31

Linezolid is a synthetic oxazolidinone and is FDA-approved for treating SSTIs and nosocomial pneumonia caused by MRSA. It has 100% oral bioavailability, so parenteral therapy should only be given if there are problems with gastrointestinal absorption or if the patient is unable to take oral medications.

Long-term use of linezolid (> 2 weeks) is limited by hematologic toxicity, especially thrombocytopenia, which occurs more frequently than anemia and neutropenia. Lactic acidosis and peripheral and optic neuropathy are also limiting toxicities. Although myelosuppression is generally reversible, peripheral and optic neuropathy may not be.

Linezolid should not used in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors if they cannot stop taking these antidepressant drugs during therapy, as the combination can lead to the serotonin syndrome.

Vancomycin is still the mainstay of parenteral therapy for MRSA infections. However, its efficacy has come into question, with concerns over its slow bactericidal activity and the emergence of resistant strains. The rate of treatment failure is high in those with infection caused by MRSA having minimum inhibitory concentrations of 1 μg/mL or greater. Vancomycin kills staphylococci more slowly than do beta-lactams in vitro and is clearly inferior to beta-lactams for methicillin-sensitive S aureus bacteremia.

Daptomycin is a lipopeptide antibiotic that is FDA-approved for adults with MRSA bacteremia, right-sided infective endocarditis, and complicated SSTI. Elevations in creatinine phosphokinase, which are rarely treatment-limiting, have occurred in patients receiving 6 mg/kg/day but not in those receiving 4 mg/kg/day. Patients should be observed for development of muscle pain or weakness and should have their creatine phosphokinase levels checked weekly, with more frequent monitoring in those with renal insufficiency or who are receiving concomitant statin therapy.

Telavancin is a parenteral lipoglycopeptide that is bactericidal against MRSA. It is FDA-approved for complicated SSTIs in adults. Creatinine levels should be monitored, and the dosage should be adjusted on the basis of creatinine clearance, because nephrotoxicity was more commonly reported among individuals treated with telavancin than among those treated with vancomycin.

Ceftaroline (Teflaro), a fifth-generation cephalosporin, was approved for SSTIs by the FDA in October 2010. It is active against MRSA and gram-negative pathogens.

Cost is a consideration

Cost is a consideration, as it may limit the availability of and access to treatment. In 2008, the expense for 10 days of treatment with generic vancomycin was $183, compared with $1,661 for daptomycin, $1,362 for tigecycline, and $1,560 for linezolid. For outpatient therapy, the contrast was even starker, as generic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole cost $9.40 and generic clindamycin cost $95.10.32

INDICATIONS FOR HOSPITALIZATION

Patients who have evidence of tissue necrosis, fever, hypotension, severe pain, altered mental status, an immunocompromised state, or organ failure (respiratory, renal, or hepatic) must be hospitalized.

Although therapy for MRSA is the mainstay of empiric therapy, polymicrobial infections are not uncommon, and gram-negative and anaerobic coverage should be added as appropriate. One study revealed a longer length of stay for hospitalized patients who had inadequate initial empiric coverage.33

Vigilance should be maintained for overlying cellulitis which can mask necrotizing fasciitis, septic joints, or osteomyelitis.

Perianal abscesses and infections, infected decubitus ulcers, and moderate to severe diabetic foot infections are often polymicrobial and warrant coverage for streptococci, MRSA, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes until culture results can guide therapy.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL REFERRAL

Extensive perianal or multiple abscesses may require surgical drainage and debridement.

Surgical site infections should be referred for consideration of opening the incision for drainage.

Necrotizing infections warrant prompt aggressive surgical debridement. Strongly suggestive clinical signs include bullae, crepitus, gas on radiography, hypotension with systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, or skin necrosis. However, these are late findings, and fewer than 50% of these patients have one of these. Most cases of necrotizing fasciitis originally have an admitting diagnosis of cellulitis and cases of fasciitis are relatively rare, so the diagnosis is easy to miss.15,16 Patients with an LRINEC score of six or more should have prompt surgical evaluation.20,24,34,35

- Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:1585–1591.

- Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, Espinola JA, Hooper DC, Camargo CA. Increased US emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 51:291–298.

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1516–1518.

- Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:380–390.

- Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al; Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:1763–1771.

- Chua K, Laurent F, Coombs G, Grayson ML, Howden BP. Antimicrobial resistance: not community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA)! A clinician’s guide to community MRSA—its evolving antimicrobial resistance and implications for therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:99–114.

- Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics cannot distinguish community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection from methicillin-susceptible S. aureus infection: a prospective investigation. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:471–482.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MRSA Infections. http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/statistics/MRSA-Surveillance-Summary.html. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Stilwell MG, Fritsche TR. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007; 57:7–13.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Uncomplicated and Complicated Skin and Skin Structure Infections—Developing Antimicrobial Drugs for Treatment (draft guidance). July 1998. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/2566dft.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- US Food and Drug Administration. CDER 2008 Meeting Documents. Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cder08.html#AntiInfective. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infections: Developing Drugs for Treatment (draft guidance). August 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071185.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- Cornia PB, Davidson HL, Lipsky BA. The evaluation and treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008; 9:717–730.

- Ki V, Rotstein C. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections in adults: a review of their epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and site of care. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2008; 19:173–184.

- May AK, Stafford RE, Bulger EM, et al; Surgical Infection Society. Treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009; 10:467–499.

- Napolitano LM. Severe soft tissue infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009; 23:571–591.

- Papadavid E, Dalamaga M, Stavrianeas N, Papiris SA. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis masquerading as cellulitis. Dermatology 2008; 217:212–214.

- Falagas ME, Vergidis PI. Narrative review: diseases that masquerade as infectious cellulitis. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:47–55.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1373–1406.

- Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:1535–1541.

- Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1072–1079.

- Lazzarini L, Conti E, Tositti G, de Lalla F. Erysipelas and cellulitis: clinical and microbiological spectrum in an Italian tertiary care hospital. J Infect 2005; 51:383–389.

- Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:705–710.

- Hasham S, Matteucci P, Stanley PR, Hart NB. Necrotising fasciitis. BMJ 2005; 330:830–833.

- Newell PM, Norden CW. Value of needle aspiration in bacteriologic diagnosis of cellulitis in adults. J Clin Microbiol 1988; 26:401–404.

- Sachs MK. The optimum use of needle aspiration in the bacteriologic diagnosis of cellulitis in adults. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:1907–1912.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e18–e55.

- Hammond SP, Baden LR. Clinical decisions. Management of skin and soft-tissue infection—polling results. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:e20.

- Perlroth J, Kuo M, Tan J, Bayer AS, Miller LG. Adjunctive use of rifampin for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:805–819.

- Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 1998; 40:1–15.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: increased risk of death with Tygacil (tigecycline) compared to other antibiotics used to treat similar infections. September 2010. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm224370.htm. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- Moellering RC. A 39-year-old man with a skin infection. JAMA 2008; 299:79–87.

- Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Hospitalizations with healthcare-associated complicated skin and skin structure infections: impact of inappropriate empiric therapy on outcomes. J Hosp Med 2010; 5:535–540.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85:1454–1460.

- Hsiao CT, Weng HH, Yuan YD, Chen CT, Chen IC. Predictors of mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Emerg Med 2008; 26:170–175.

Skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) are a common reason for presentation to outpatient practices, emergency rooms, and hospitals.1–5 They account for more than 14 million outpatient visits in the United States each year,1 and visits to the emergency room and admissions to the hospital for them are increasing.2,3 Hospital admissions for SSTIs increased by 29% from 2000 to 2004.3

MORE MRSA NOW, BUT STREPTOCOCCI ARE STILL COMMON

The increase in hospital admissions for SSTIs has been attributed to a rising number of infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).3–5

In addition, strains once seen mostly in the community and other strains that were associated with health care are now being seen more often in both settings. Clinical characteristics do not differ between community-acquired and health-care-associated MRSA, and therefore the distinction between the two is becoming less useful in guiding empiric therapy.6,7

After steadily increasing for several years, the incidence of MRSA has recently stabilized. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintains a surveillance program and a Web site on MRSA.8

COMPLICATED OR UNCOMPLICATED

The intent of the 1998 guideline was to provide not a clinical framework but rather a guide for industry in designing trials that would include similar groups of infections and therefore be relevant when compared with each other. In 2008, the Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee was convened,11 and subsequently, in August 2010, the FDA released a revision of the guide.12

The revised guidelines specifically exclude many diagnoses, such as bite wounds, bone and joint infections, necrotizing fasciitis, diabetic foot infections, decubitus ulcers, catheter site infections, myonecrosis, and ecthyma gangrenosum. Notably, the word “bacterial” in the title excludes mycobacterial and fungal infections from consideration. The diagnoses that are included include cellulitis, erysipelas, major cutaneous abscess, and burn infections. These are further specified to include 75 cm2 of redness, edema, or induration to standardize the extent of the infection—ie, the infection has to be at least this large or else it is not “complicated.”

The terms “complicated” and “uncomplicated” skin and skin structure infections persist and can be useful adjuncts in describing SSTIs.13–16 However, more specific descriptions of SSTIs based on pathogenesis are more useful to the clinician and are usually the basis for guidelines, such as for preventing surgical site infections or for reducing amputations in diabetic foot infections.

This review will focus on the general categories of SSTI and will not address surgical site infections, pressure ulcers, diabetic foot infections, perirectal wounds, or adjuvant therapies in severe SSTIs, such as negative pressure wound care (vacuum-assisted closure devices) and hyperbaric chambers.

OTHER DISEASES CAN MIMIC SSTIs

SSTIs vary broadly in their location and severity.

Although the classic presentation of erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness often signals infection, other diseases can mimic SSTIs. Common ones that should be included in the differential diagnosis include gout, thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis, contact dermatitis, carcinoma erysipeloides, drug eruption, and a foreign body reaction.17,18

CLUES FROM THE HISTORY

Wounds. Skin infections are usually precipitated by a break in the skin from a cut, laceration, excoriation, fungal infection, insect or animal bite, or puncture wound.

Impaired response. Patients with diabetes, renal failure, cirrhosis, chronic glucocorticoid use, history of organ transplantation, chronic immunosuppressive therapy, HIV infection, or malnourishment have impaired host responses to infection and are at risk for both more severe infections and recurrent infections. Immunocompromised hosts may also have atypical infections with opportunistic organisms such as Pseudomonas, Proteus, Serratia, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, and anaerobes. Close follow-up of these patients is warranted to ascertain appropriate response to therapy.19

Surgery that includes lymph node dissection or saphenous vein resection for coronary artery bypass can lead to impaired lymphatic drainage and edema, and therefore predisposes patients to SSTIs.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should include descriptions of the extent and location of erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness so that progression or resolution with treatment can be followed in detail.

Crepitus can be felt in gas-forming infections and raises the concern for necrotizing fasciitis and infection with anaerobic organisms such as Clostridium perfringens.

Necrosis can occur in brown recluse spider bites, venous snake bites, or group A streptococcal infections.

Fluctuance indicates fluid and a likely abscess that may need incision and drainage.

Purpura may be present in patients on anticoagulation therapy, but if it is accompanying an SSTI, it also raises the concern for the possibility of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, especially from streptococcal infections.

Bullae can be seen in impetigo caused by staphylococci or in infection with Vibrio vulnificus or Streptococcus pneumoniae.19

Systemic signs, in addition to fever, can include hypotension and tachycardia, which would prompt closer monitoring and possible hospitalization.

Lymphangitic spread also indicates severe infection.

LABORATORY STUDIES

Simple, localized SSTIs usually do not require laboratory evaluation. Jenkins et al21 recently demonstrated that by using an algorithm for the management of hospitalized patients with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, they could decrease resource utilization, including laboratory testing, without adversely affecting clinical outcome.

If patients have underlying disease or more extensive infection, then baseline chemistry values, a complete blood cell count, and the C-reactive protein level should be acquired.19 Laboratory findings that suggest more severe disease include low sodium, low bicarbonate (or an anion gap), and high creatinine levels; new anemia; a high or very low white blood cell count; and a high C-reactive protein level. A high C-reactive protein level has been associated with longer hospitalization.22

A score to estimate the risk of necrotizing fasciitis

This tool was developed retrospectively but has been validated prospectively. It has a high sensitivity and a positive predictive value of 92% in patients with a score of six points or more. Its specificity is also high, with a negative predictive value of 96%.20,24

Necrotizing fasciitis has a mortality rate of 23.5%, but this may be reduced to 10% with early detection and prompt surgical intervention.15 Since necrotizing fasciitis is very difficult to diagnose, clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion and use the LRINEC score to trigger early surgical evaluation. Surgical exploration is the only way to definitively diagnose necrotizing fasciitis.

Blood cultures in some cases

Blood cultures have a low yield and are usually not cost-effective, but they should be obtained in patients who have lymphedema, immune deficiency, fever, pain out of proportion to the findings on examination, tachycardia, or hypotension, as blood cultures are more likely to be positive in more serious infections and can help guide antimicrobial therapy. Blood cultures are also recommended in patients with infections involving specific anatomic sites, such as the mouth and eyes.19

Aspiration, swabs, incision and drainage

Fluid aspirated from abscesses and swabs of debrided ulcerated wounds should be sent for Gram stain and culture. Gram stain and culture have widely varying yields, from less than 5% to 40%, depending on the source and technique.19 Cultures were not routinely obtained before MRSA emerged, but knowing antimicrobial susceptibility is now important to guide antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, in cellulitis, swabs and aspirates of the leading edge have a low yield of around 10%.25 One prospective study of 25 hospitalized patients did report a higher yield of positive cultures in patients with fever or underlying disease,26 so aspirates may be used in selected cases. In small studies, the yield of punch biopsies was slightly better than that of needle aspirates and was as high as 20% to 30%.27

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging can be helpful in determining the depth of involvement. Plain radiography can reveal gas or periosteal inflammation and is especially helpful in diabetic foot infections. Ultrasonography can detect abscesses.

Both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are useful to image fascial planes, although MRI is more sensitive. However, in cases of suspected necrotizing fasciitis, imaging should not delay surgical evaluation and debridement or be used as the definitive study. Therefore, the practicality of CT and MRI can be limited.15,16

ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT FOR SSTIs IN OUTPATIENTS

For minor skin infections such as impetigo and secondarily infected skin lesions such as eczema, ulcers, or lacerations, mupirocin 2% topical ointment (Bactroban) can be effective.27

For a simple abscess or boil, incision and drainage is the primary treatment, and antibiotics are not needed.

For a complicated abscess or boil. Patients should be given oral or intravenous antibiotic therapy to cover MRSA and, depending on the severity, should be considered for hospitalization if the abscess is associated with severe disease, rapid progression in the presence of associated cellulitis, septic phlebitis, constitutional symptoms, comorbidity (including immunosuppression), or an abscess or boil in an area difficult to drain, such as the face, hands, or genitalia.27

For purulent cellulitis in outpatients, empiric therapy for community-acquired MRSA is recommended, pending culture results. Empiric therapy for streptococcal infection is likely unnecessary. For empiric coverage of community-acquired MRSA in purulent cellulitis, oral antibiotic options include clindamycin (Cleocin), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), doxycycline (Doryx), minocycline (Minocin), and linezolid (Zyvox).

For nonpurulent cellulitis in outpatients, empiric coverage for beta-hemolytic streptococci is warranted. Coverage for community-acquired MRSA should subsequently be added for patients who do not respond to beta-lactam therapy within 48 to 72 hours or who have chills, fever, a new abscess, increasing erythema, or uncontrolled pain.

Options for coverage of both beta-hemolytic streptococci and community-acquired MRSA for outpatient therapy include clindamycin on its own, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a tetracycline in combination with a beta-lactam, or linezolid on its own.

Increasing rates of resistance to clindamycin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in community-acquired MRSA may limit empiric treatment. In areas where resistance is prevalent, culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing may be required before starting one of these antibiotics.

The use of rifampin (Rifadin) as a single agent is not recommended because resistance is likely to develop. Also, rifampin is not useful as adjunctive therapy, as evidence does not support its efficacy.19,27,29

ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT FOR SSTIs IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

For hospitalized patients with a complicated or severe SSTI, empiric therapy for MRSA should be started pending culture results. FDA-approved options are vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin (Cubicin), tigecycline (Tygacil), and telavancin (Vibativ). Data on clindamycin are very limited in this population. A beta-lactam antibiotic such as cefazolin (Ancef) may be considered in hospitalized patients with nonpurulent cellulitis, and the regimen can be modified to MRSA-active therapy if there is no clinical response. Linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, and telavancin have adequate streptococcal coverage in addition to MRSA coverage.

Clindamycin is approved by the FDA for treating serious infections due to S aureus. It has excellent tissue penetration, particularly in bone and abscesses.

Clindamycin resistance in staphylococci can be either constitutive or inducible, and clinicians must be watchful for signs of resistance.

Diarrhea is the most common adverse effect and occurs in up to 20% of patients. Clostridium difficile colitis may occur more frequently with clindamycin than with other oral agents, but it has also has been reported with fluoroquinolones and can be associated with any antibiotic therapy.30

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is not FDA-approved for treating any staphylococcal infection. However, because 95% to 100% of community-acquired MRSA strains are susceptible to it in vitro, it has become an important option in the outpatient treatment of SSTIs. Caution is advised when using it in elderly patients, particularly those with chronic renal insufficiency, because of an increased risk of hyperkalemia.

Tetracyclines. Doxycycline is FDA-approved for treating SSTIs due to S aureus, although not specifically for MRSA. Minocycline may be an option even when strains are resistant to doxycycline, since it does not induce its own resistance as doxycycline does.

Tigecycline is a glycylcycline (a tetracycline derivative) and is FDA-approved in adults for complicated SSTIs and intra-abdominal infections. It has a large volume of distribution and achieves high concentrations in tissues and low concentrations in serum.

The FDA recently issued a warning to consider alternative agents in patients with serious infections because of higher rates of all-cause mortality noted in phase III and phase IV clinical trials. Due to this warning and the availability of multiple alternatives active against MRSA, tigecycline was not included in the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines.31

Linezolid is a synthetic oxazolidinone and is FDA-approved for treating SSTIs and nosocomial pneumonia caused by MRSA. It has 100% oral bioavailability, so parenteral therapy should only be given if there are problems with gastrointestinal absorption or if the patient is unable to take oral medications.

Long-term use of linezolid (> 2 weeks) is limited by hematologic toxicity, especially thrombocytopenia, which occurs more frequently than anemia and neutropenia. Lactic acidosis and peripheral and optic neuropathy are also limiting toxicities. Although myelosuppression is generally reversible, peripheral and optic neuropathy may not be.

Linezolid should not used in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors if they cannot stop taking these antidepressant drugs during therapy, as the combination can lead to the serotonin syndrome.

Vancomycin is still the mainstay of parenteral therapy for MRSA infections. However, its efficacy has come into question, with concerns over its slow bactericidal activity and the emergence of resistant strains. The rate of treatment failure is high in those with infection caused by MRSA having minimum inhibitory concentrations of 1 μg/mL or greater. Vancomycin kills staphylococci more slowly than do beta-lactams in vitro and is clearly inferior to beta-lactams for methicillin-sensitive S aureus bacteremia.

Daptomycin is a lipopeptide antibiotic that is FDA-approved for adults with MRSA bacteremia, right-sided infective endocarditis, and complicated SSTI. Elevations in creatinine phosphokinase, which are rarely treatment-limiting, have occurred in patients receiving 6 mg/kg/day but not in those receiving 4 mg/kg/day. Patients should be observed for development of muscle pain or weakness and should have their creatine phosphokinase levels checked weekly, with more frequent monitoring in those with renal insufficiency or who are receiving concomitant statin therapy.

Telavancin is a parenteral lipoglycopeptide that is bactericidal against MRSA. It is FDA-approved for complicated SSTIs in adults. Creatinine levels should be monitored, and the dosage should be adjusted on the basis of creatinine clearance, because nephrotoxicity was more commonly reported among individuals treated with telavancin than among those treated with vancomycin.

Ceftaroline (Teflaro), a fifth-generation cephalosporin, was approved for SSTIs by the FDA in October 2010. It is active against MRSA and gram-negative pathogens.

Cost is a consideration

Cost is a consideration, as it may limit the availability of and access to treatment. In 2008, the expense for 10 days of treatment with generic vancomycin was $183, compared with $1,661 for daptomycin, $1,362 for tigecycline, and $1,560 for linezolid. For outpatient therapy, the contrast was even starker, as generic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole cost $9.40 and generic clindamycin cost $95.10.32

INDICATIONS FOR HOSPITALIZATION

Patients who have evidence of tissue necrosis, fever, hypotension, severe pain, altered mental status, an immunocompromised state, or organ failure (respiratory, renal, or hepatic) must be hospitalized.

Although therapy for MRSA is the mainstay of empiric therapy, polymicrobial infections are not uncommon, and gram-negative and anaerobic coverage should be added as appropriate. One study revealed a longer length of stay for hospitalized patients who had inadequate initial empiric coverage.33

Vigilance should be maintained for overlying cellulitis which can mask necrotizing fasciitis, septic joints, or osteomyelitis.

Perianal abscesses and infections, infected decubitus ulcers, and moderate to severe diabetic foot infections are often polymicrobial and warrant coverage for streptococci, MRSA, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes until culture results can guide therapy.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL REFERRAL

Extensive perianal or multiple abscesses may require surgical drainage and debridement.

Surgical site infections should be referred for consideration of opening the incision for drainage.

Necrotizing infections warrant prompt aggressive surgical debridement. Strongly suggestive clinical signs include bullae, crepitus, gas on radiography, hypotension with systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, or skin necrosis. However, these are late findings, and fewer than 50% of these patients have one of these. Most cases of necrotizing fasciitis originally have an admitting diagnosis of cellulitis and cases of fasciitis are relatively rare, so the diagnosis is easy to miss.15,16 Patients with an LRINEC score of six or more should have prompt surgical evaluation.20,24,34,35

Skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) are a common reason for presentation to outpatient practices, emergency rooms, and hospitals.1–5 They account for more than 14 million outpatient visits in the United States each year,1 and visits to the emergency room and admissions to the hospital for them are increasing.2,3 Hospital admissions for SSTIs increased by 29% from 2000 to 2004.3

MORE MRSA NOW, BUT STREPTOCOCCI ARE STILL COMMON

The increase in hospital admissions for SSTIs has been attributed to a rising number of infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).3–5

In addition, strains once seen mostly in the community and other strains that were associated with health care are now being seen more often in both settings. Clinical characteristics do not differ between community-acquired and health-care-associated MRSA, and therefore the distinction between the two is becoming less useful in guiding empiric therapy.6,7

After steadily increasing for several years, the incidence of MRSA has recently stabilized. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintains a surveillance program and a Web site on MRSA.8

COMPLICATED OR UNCOMPLICATED

The intent of the 1998 guideline was to provide not a clinical framework but rather a guide for industry in designing trials that would include similar groups of infections and therefore be relevant when compared with each other. In 2008, the Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee was convened,11 and subsequently, in August 2010, the FDA released a revision of the guide.12

The revised guidelines specifically exclude many diagnoses, such as bite wounds, bone and joint infections, necrotizing fasciitis, diabetic foot infections, decubitus ulcers, catheter site infections, myonecrosis, and ecthyma gangrenosum. Notably, the word “bacterial” in the title excludes mycobacterial and fungal infections from consideration. The diagnoses that are included include cellulitis, erysipelas, major cutaneous abscess, and burn infections. These are further specified to include 75 cm2 of redness, edema, or induration to standardize the extent of the infection—ie, the infection has to be at least this large or else it is not “complicated.”

The terms “complicated” and “uncomplicated” skin and skin structure infections persist and can be useful adjuncts in describing SSTIs.13–16 However, more specific descriptions of SSTIs based on pathogenesis are more useful to the clinician and are usually the basis for guidelines, such as for preventing surgical site infections or for reducing amputations in diabetic foot infections.

This review will focus on the general categories of SSTI and will not address surgical site infections, pressure ulcers, diabetic foot infections, perirectal wounds, or adjuvant therapies in severe SSTIs, such as negative pressure wound care (vacuum-assisted closure devices) and hyperbaric chambers.

OTHER DISEASES CAN MIMIC SSTIs

SSTIs vary broadly in their location and severity.

Although the classic presentation of erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness often signals infection, other diseases can mimic SSTIs. Common ones that should be included in the differential diagnosis include gout, thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis, contact dermatitis, carcinoma erysipeloides, drug eruption, and a foreign body reaction.17,18

CLUES FROM THE HISTORY

Wounds. Skin infections are usually precipitated by a break in the skin from a cut, laceration, excoriation, fungal infection, insect or animal bite, or puncture wound.

Impaired response. Patients with diabetes, renal failure, cirrhosis, chronic glucocorticoid use, history of organ transplantation, chronic immunosuppressive therapy, HIV infection, or malnourishment have impaired host responses to infection and are at risk for both more severe infections and recurrent infections. Immunocompromised hosts may also have atypical infections with opportunistic organisms such as Pseudomonas, Proteus, Serratia, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, and anaerobes. Close follow-up of these patients is warranted to ascertain appropriate response to therapy.19

Surgery that includes lymph node dissection or saphenous vein resection for coronary artery bypass can lead to impaired lymphatic drainage and edema, and therefore predisposes patients to SSTIs.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should include descriptions of the extent and location of erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness so that progression or resolution with treatment can be followed in detail.

Crepitus can be felt in gas-forming infections and raises the concern for necrotizing fasciitis and infection with anaerobic organisms such as Clostridium perfringens.

Necrosis can occur in brown recluse spider bites, venous snake bites, or group A streptococcal infections.

Fluctuance indicates fluid and a likely abscess that may need incision and drainage.

Purpura may be present in patients on anticoagulation therapy, but if it is accompanying an SSTI, it also raises the concern for the possibility of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, especially from streptococcal infections.

Bullae can be seen in impetigo caused by staphylococci or in infection with Vibrio vulnificus or Streptococcus pneumoniae.19

Systemic signs, in addition to fever, can include hypotension and tachycardia, which would prompt closer monitoring and possible hospitalization.

Lymphangitic spread also indicates severe infection.

LABORATORY STUDIES

Simple, localized SSTIs usually do not require laboratory evaluation. Jenkins et al21 recently demonstrated that by using an algorithm for the management of hospitalized patients with cellulitis or cutaneous abscess, they could decrease resource utilization, including laboratory testing, without adversely affecting clinical outcome.

If patients have underlying disease or more extensive infection, then baseline chemistry values, a complete blood cell count, and the C-reactive protein level should be acquired.19 Laboratory findings that suggest more severe disease include low sodium, low bicarbonate (or an anion gap), and high creatinine levels; new anemia; a high or very low white blood cell count; and a high C-reactive protein level. A high C-reactive protein level has been associated with longer hospitalization.22

A score to estimate the risk of necrotizing fasciitis

This tool was developed retrospectively but has been validated prospectively. It has a high sensitivity and a positive predictive value of 92% in patients with a score of six points or more. Its specificity is also high, with a negative predictive value of 96%.20,24

Necrotizing fasciitis has a mortality rate of 23.5%, but this may be reduced to 10% with early detection and prompt surgical intervention.15 Since necrotizing fasciitis is very difficult to diagnose, clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion and use the LRINEC score to trigger early surgical evaluation. Surgical exploration is the only way to definitively diagnose necrotizing fasciitis.

Blood cultures in some cases

Blood cultures have a low yield and are usually not cost-effective, but they should be obtained in patients who have lymphedema, immune deficiency, fever, pain out of proportion to the findings on examination, tachycardia, or hypotension, as blood cultures are more likely to be positive in more serious infections and can help guide antimicrobial therapy. Blood cultures are also recommended in patients with infections involving specific anatomic sites, such as the mouth and eyes.19

Aspiration, swabs, incision and drainage

Fluid aspirated from abscesses and swabs of debrided ulcerated wounds should be sent for Gram stain and culture. Gram stain and culture have widely varying yields, from less than 5% to 40%, depending on the source and technique.19 Cultures were not routinely obtained before MRSA emerged, but knowing antimicrobial susceptibility is now important to guide antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, in cellulitis, swabs and aspirates of the leading edge have a low yield of around 10%.25 One prospective study of 25 hospitalized patients did report a higher yield of positive cultures in patients with fever or underlying disease,26 so aspirates may be used in selected cases. In small studies, the yield of punch biopsies was slightly better than that of needle aspirates and was as high as 20% to 30%.27

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging can be helpful in determining the depth of involvement. Plain radiography can reveal gas or periosteal inflammation and is especially helpful in diabetic foot infections. Ultrasonography can detect abscesses.

Both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are useful to image fascial planes, although MRI is more sensitive. However, in cases of suspected necrotizing fasciitis, imaging should not delay surgical evaluation and debridement or be used as the definitive study. Therefore, the practicality of CT and MRI can be limited.15,16

ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT FOR SSTIs IN OUTPATIENTS

For minor skin infections such as impetigo and secondarily infected skin lesions such as eczema, ulcers, or lacerations, mupirocin 2% topical ointment (Bactroban) can be effective.27

For a simple abscess or boil, incision and drainage is the primary treatment, and antibiotics are not needed.

For a complicated abscess or boil. Patients should be given oral or intravenous antibiotic therapy to cover MRSA and, depending on the severity, should be considered for hospitalization if the abscess is associated with severe disease, rapid progression in the presence of associated cellulitis, septic phlebitis, constitutional symptoms, comorbidity (including immunosuppression), or an abscess or boil in an area difficult to drain, such as the face, hands, or genitalia.27

For purulent cellulitis in outpatients, empiric therapy for community-acquired MRSA is recommended, pending culture results. Empiric therapy for streptococcal infection is likely unnecessary. For empiric coverage of community-acquired MRSA in purulent cellulitis, oral antibiotic options include clindamycin (Cleocin), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), doxycycline (Doryx), minocycline (Minocin), and linezolid (Zyvox).

For nonpurulent cellulitis in outpatients, empiric coverage for beta-hemolytic streptococci is warranted. Coverage for community-acquired MRSA should subsequently be added for patients who do not respond to beta-lactam therapy within 48 to 72 hours or who have chills, fever, a new abscess, increasing erythema, or uncontrolled pain.

Options for coverage of both beta-hemolytic streptococci and community-acquired MRSA for outpatient therapy include clindamycin on its own, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a tetracycline in combination with a beta-lactam, or linezolid on its own.

Increasing rates of resistance to clindamycin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in community-acquired MRSA may limit empiric treatment. In areas where resistance is prevalent, culture with antimicrobial susceptibility testing may be required before starting one of these antibiotics.

The use of rifampin (Rifadin) as a single agent is not recommended because resistance is likely to develop. Also, rifampin is not useful as adjunctive therapy, as evidence does not support its efficacy.19,27,29

ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT FOR SSTIs IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

For hospitalized patients with a complicated or severe SSTI, empiric therapy for MRSA should be started pending culture results. FDA-approved options are vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin (Cubicin), tigecycline (Tygacil), and telavancin (Vibativ). Data on clindamycin are very limited in this population. A beta-lactam antibiotic such as cefazolin (Ancef) may be considered in hospitalized patients with nonpurulent cellulitis, and the regimen can be modified to MRSA-active therapy if there is no clinical response. Linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, and telavancin have adequate streptococcal coverage in addition to MRSA coverage.

Clindamycin is approved by the FDA for treating serious infections due to S aureus. It has excellent tissue penetration, particularly in bone and abscesses.

Clindamycin resistance in staphylococci can be either constitutive or inducible, and clinicians must be watchful for signs of resistance.

Diarrhea is the most common adverse effect and occurs in up to 20% of patients. Clostridium difficile colitis may occur more frequently with clindamycin than with other oral agents, but it has also has been reported with fluoroquinolones and can be associated with any antibiotic therapy.30

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is not FDA-approved for treating any staphylococcal infection. However, because 95% to 100% of community-acquired MRSA strains are susceptible to it in vitro, it has become an important option in the outpatient treatment of SSTIs. Caution is advised when using it in elderly patients, particularly those with chronic renal insufficiency, because of an increased risk of hyperkalemia.

Tetracyclines. Doxycycline is FDA-approved for treating SSTIs due to S aureus, although not specifically for MRSA. Minocycline may be an option even when strains are resistant to doxycycline, since it does not induce its own resistance as doxycycline does.

Tigecycline is a glycylcycline (a tetracycline derivative) and is FDA-approved in adults for complicated SSTIs and intra-abdominal infections. It has a large volume of distribution and achieves high concentrations in tissues and low concentrations in serum.

The FDA recently issued a warning to consider alternative agents in patients with serious infections because of higher rates of all-cause mortality noted in phase III and phase IV clinical trials. Due to this warning and the availability of multiple alternatives active against MRSA, tigecycline was not included in the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines.31

Linezolid is a synthetic oxazolidinone and is FDA-approved for treating SSTIs and nosocomial pneumonia caused by MRSA. It has 100% oral bioavailability, so parenteral therapy should only be given if there are problems with gastrointestinal absorption or if the patient is unable to take oral medications.

Long-term use of linezolid (> 2 weeks) is limited by hematologic toxicity, especially thrombocytopenia, which occurs more frequently than anemia and neutropenia. Lactic acidosis and peripheral and optic neuropathy are also limiting toxicities. Although myelosuppression is generally reversible, peripheral and optic neuropathy may not be.

Linezolid should not used in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors if they cannot stop taking these antidepressant drugs during therapy, as the combination can lead to the serotonin syndrome.

Vancomycin is still the mainstay of parenteral therapy for MRSA infections. However, its efficacy has come into question, with concerns over its slow bactericidal activity and the emergence of resistant strains. The rate of treatment failure is high in those with infection caused by MRSA having minimum inhibitory concentrations of 1 μg/mL or greater. Vancomycin kills staphylococci more slowly than do beta-lactams in vitro and is clearly inferior to beta-lactams for methicillin-sensitive S aureus bacteremia.

Daptomycin is a lipopeptide antibiotic that is FDA-approved for adults with MRSA bacteremia, right-sided infective endocarditis, and complicated SSTI. Elevations in creatinine phosphokinase, which are rarely treatment-limiting, have occurred in patients receiving 6 mg/kg/day but not in those receiving 4 mg/kg/day. Patients should be observed for development of muscle pain or weakness and should have their creatine phosphokinase levels checked weekly, with more frequent monitoring in those with renal insufficiency or who are receiving concomitant statin therapy.

Telavancin is a parenteral lipoglycopeptide that is bactericidal against MRSA. It is FDA-approved for complicated SSTIs in adults. Creatinine levels should be monitored, and the dosage should be adjusted on the basis of creatinine clearance, because nephrotoxicity was more commonly reported among individuals treated with telavancin than among those treated with vancomycin.

Ceftaroline (Teflaro), a fifth-generation cephalosporin, was approved for SSTIs by the FDA in October 2010. It is active against MRSA and gram-negative pathogens.

Cost is a consideration

Cost is a consideration, as it may limit the availability of and access to treatment. In 2008, the expense for 10 days of treatment with generic vancomycin was $183, compared with $1,661 for daptomycin, $1,362 for tigecycline, and $1,560 for linezolid. For outpatient therapy, the contrast was even starker, as generic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole cost $9.40 and generic clindamycin cost $95.10.32

INDICATIONS FOR HOSPITALIZATION

Patients who have evidence of tissue necrosis, fever, hypotension, severe pain, altered mental status, an immunocompromised state, or organ failure (respiratory, renal, or hepatic) must be hospitalized.

Although therapy for MRSA is the mainstay of empiric therapy, polymicrobial infections are not uncommon, and gram-negative and anaerobic coverage should be added as appropriate. One study revealed a longer length of stay for hospitalized patients who had inadequate initial empiric coverage.33

Vigilance should be maintained for overlying cellulitis which can mask necrotizing fasciitis, septic joints, or osteomyelitis.

Perianal abscesses and infections, infected decubitus ulcers, and moderate to severe diabetic foot infections are often polymicrobial and warrant coverage for streptococci, MRSA, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes until culture results can guide therapy.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL REFERRAL

Extensive perianal or multiple abscesses may require surgical drainage and debridement.

Surgical site infections should be referred for consideration of opening the incision for drainage.

Necrotizing infections warrant prompt aggressive surgical debridement. Strongly suggestive clinical signs include bullae, crepitus, gas on radiography, hypotension with systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, or skin necrosis. However, these are late findings, and fewer than 50% of these patients have one of these. Most cases of necrotizing fasciitis originally have an admitting diagnosis of cellulitis and cases of fasciitis are relatively rare, so the diagnosis is easy to miss.15,16 Patients with an LRINEC score of six or more should have prompt surgical evaluation.20,24,34,35

- Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:1585–1591.

- Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, Espinola JA, Hooper DC, Camargo CA. Increased US emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 51:291–298.

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1516–1518.

- Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:380–390.

- Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al; Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:1763–1771.

- Chua K, Laurent F, Coombs G, Grayson ML, Howden BP. Antimicrobial resistance: not community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA)! A clinician’s guide to community MRSA—its evolving antimicrobial resistance and implications for therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:99–114.

- Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics cannot distinguish community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection from methicillin-susceptible S. aureus infection: a prospective investigation. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:471–482.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MRSA Infections. http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/statistics/MRSA-Surveillance-Summary.html. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Stilwell MG, Fritsche TR. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007; 57:7–13.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Uncomplicated and Complicated Skin and Skin Structure Infections—Developing Antimicrobial Drugs for Treatment (draft guidance). July 1998. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/2566dft.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- US Food and Drug Administration. CDER 2008 Meeting Documents. Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cder08.html#AntiInfective. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infections: Developing Drugs for Treatment (draft guidance). August 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071185.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- Cornia PB, Davidson HL, Lipsky BA. The evaluation and treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008; 9:717–730.

- Ki V, Rotstein C. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections in adults: a review of their epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and site of care. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2008; 19:173–184.

- May AK, Stafford RE, Bulger EM, et al; Surgical Infection Society. Treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009; 10:467–499.

- Napolitano LM. Severe soft tissue infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009; 23:571–591.

- Papadavid E, Dalamaga M, Stavrianeas N, Papiris SA. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis masquerading as cellulitis. Dermatology 2008; 217:212–214.

- Falagas ME, Vergidis PI. Narrative review: diseases that masquerade as infectious cellulitis. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:47–55.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1373–1406.

- Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:1535–1541.

- Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1072–1079.

- Lazzarini L, Conti E, Tositti G, de Lalla F. Erysipelas and cellulitis: clinical and microbiological spectrum in an Italian tertiary care hospital. J Infect 2005; 51:383–389.

- Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:705–710.

- Hasham S, Matteucci P, Stanley PR, Hart NB. Necrotising fasciitis. BMJ 2005; 330:830–833.

- Newell PM, Norden CW. Value of needle aspiration in bacteriologic diagnosis of cellulitis in adults. J Clin Microbiol 1988; 26:401–404.

- Sachs MK. The optimum use of needle aspiration in the bacteriologic diagnosis of cellulitis in adults. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:1907–1912.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e18–e55.

- Hammond SP, Baden LR. Clinical decisions. Management of skin and soft-tissue infection—polling results. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:e20.

- Perlroth J, Kuo M, Tan J, Bayer AS, Miller LG. Adjunctive use of rifampin for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:805–819.

- Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 1998; 40:1–15.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: increased risk of death with Tygacil (tigecycline) compared to other antibiotics used to treat similar infections. September 2010. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm224370.htm. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- Moellering RC. A 39-year-old man with a skin infection. JAMA 2008; 299:79–87.

- Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Hospitalizations with healthcare-associated complicated skin and skin structure infections: impact of inappropriate empiric therapy on outcomes. J Hosp Med 2010; 5:535–540.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85:1454–1460.

- Hsiao CT, Weng HH, Yuan YD, Chen CT, Chen IC. Predictors of mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Emerg Med 2008; 26:170–175.

- Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:1585–1591.

- Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, Espinola JA, Hooper DC, Camargo CA. Increased US emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 51:291–298.

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1516–1518.

- Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:380–390.

- Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al; Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:1763–1771.

- Chua K, Laurent F, Coombs G, Grayson ML, Howden BP. Antimicrobial resistance: not community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA)! A clinician’s guide to community MRSA—its evolving antimicrobial resistance and implications for therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:99–114.

- Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics cannot distinguish community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection from methicillin-susceptible S. aureus infection: a prospective investigation. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:471–482.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MRSA Infections. http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/statistics/MRSA-Surveillance-Summary.html. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- Moet GJ, Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Stilwell MG, Fritsche TR. Contemporary causes of skin and soft tissue infections in North America, Latin America, and Europe: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1998–2004). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007; 57:7–13.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Uncomplicated and Complicated Skin and Skin Structure Infections—Developing Antimicrobial Drugs for Treatment (draft guidance). July 1998. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/2566dft.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- US Food and Drug Administration. CDER 2008 Meeting Documents. Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cder08.html#AntiInfective. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infections: Developing Drugs for Treatment (draft guidance). August 2010. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm071185.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- Cornia PB, Davidson HL, Lipsky BA. The evaluation and treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008; 9:717–730.

- Ki V, Rotstein C. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections in adults: a review of their epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and site of care. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2008; 19:173–184.

- May AK, Stafford RE, Bulger EM, et al; Surgical Infection Society. Treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009; 10:467–499.

- Napolitano LM. Severe soft tissue infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009; 23:571–591.

- Papadavid E, Dalamaga M, Stavrianeas N, Papiris SA. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis masquerading as cellulitis. Dermatology 2008; 217:212–214.

- Falagas ME, Vergidis PI. Narrative review: diseases that masquerade as infectious cellulitis. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:47–55.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1373–1406.

- Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:1535–1541.

- Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1072–1079.

- Lazzarini L, Conti E, Tositti G, de Lalla F. Erysipelas and cellulitis: clinical and microbiological spectrum in an Italian tertiary care hospital. J Infect 2005; 51:383–389.

- Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:705–710.

- Hasham S, Matteucci P, Stanley PR, Hart NB. Necrotising fasciitis. BMJ 2005; 330:830–833.

- Newell PM, Norden CW. Value of needle aspiration in bacteriologic diagnosis of cellulitis in adults. J Clin Microbiol 1988; 26:401–404.

- Sachs MK. The optimum use of needle aspiration in the bacteriologic diagnosis of cellulitis in adults. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:1907–1912.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e18–e55.

- Hammond SP, Baden LR. Clinical decisions. Management of skin and soft-tissue infection—polling results. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:e20.

- Perlroth J, Kuo M, Tan J, Bayer AS, Miller LG. Adjunctive use of rifampin for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:805–819.

- Bignardi GE. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 1998; 40:1–15.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: increased risk of death with Tygacil (tigecycline) compared to other antibiotics used to treat similar infections. September 2010. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm224370.htm. Accessed September 7, 2011.

- Moellering RC. A 39-year-old man with a skin infection. JAMA 2008; 299:79–87.

- Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Hospitalizations with healthcare-associated complicated skin and skin structure infections: impact of inappropriate empiric therapy on outcomes. J Hosp Med 2010; 5:535–540.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85:1454–1460.

- Hsiao CT, Weng HH, Yuan YD, Chen CT, Chen IC. Predictors of mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Emerg Med 2008; 26:170–175.

KEY POINTS

- Categories and definitions of specific subtypes of infections are evolving and have implications for treatment.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and streptococci continue to be the predominant organisms in SSTIs.

- A careful history and examination along with clinical attention are needed to elucidate atypical and severe infections.

- Laboratory data can help characterize the severity of disease and determine the probability of necrotizing fasciitis.

- Although cultures are unfortunately not reliably positive, their yield is higher in severe disease and they should be obtained, given the importance of antimicrobial susceptibility.

- The Infectious Diseases Society of America has recently released guidelines on MRSA, and additional guidelines addressing the spectrum of SSTIs are expected within a year.

Correction: Measles

Simple Answers to Complex Mental Health Concerns

Effects of Psychosocial Issues on Medication Adherence Among HIV/AIDS Patients

Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus With Lupus Nephritis: A Rare Case of a Subepidermal Bullous Disorder in a Child

Contact Allergy to Dimethacrylate

Knee OA: Which patients are unlikely to benefit from manual PT and exercise?

Background The combination of manual physical therapy and exercise provides important benefit for more than 80% of patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA). Our objective was to determine predictor variables for patients unlikely to respond to these interventions.

Methods We used a retrospective combined cohort study design to develop a preliminary clinical prediction rule (CPR). To determine useful predictors of nonsuccess, we used an extensive set of 167 baseline variables. These variables were extracted from standardized examination forms used with 101 patients (64 women and 37 men with a mean age of 60.5±11.8 and 63.6±9.3 years, respectively) in 2 previously published clinical trials. We classified patients based on whether they achieved a clinically meaningful benefit of at least 12% improvement in Western Ontario MacMaster (WOMAC) scores after 4 weeks of treatment using the smallest and most efficient subset of predictors.