User login

Feedback Needed to Help Guide Pediatric HM’s Certification Debate

I am decidedly anti-politics. The entire process seems fatally flawed. The vast majority of the public votes based on one or two emotional interests, such as religion or personal finances. The candidates’ responses are calculated, based on the millions of dollars they receive from competing interest groups and evidence-based analysis of what will garner the most votes. So for me at this time of year, watching debates and TV coverage of primaries is akin to watching an MTV reality show—lots of drama, little substance.

But there is one election (of sorts) this year that gives me hope: Our input has been solicited by the Strategic Planning (STP) Committee to help sort through the issue of certification in pediatric hospital medicine. What is potentially at stake here is how we define ourselves as a field. At one end is the traditional, three-year fellowship with certification as a subspecialty. At the other end is no change, or the status quo. In between are myriad options, each with unique pros and cons. It is all summarized at the STP blog (http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com), which allows for input.

This is a unique opportunity, as pediatric HM is at a crossroads. The STP Committee states that this solicitation of public comment is different from processes that other fields (pediatric emergency medicine, child abuse, adult hospital medicine) have used, and it will allow for more engagement of the pediatric hospitalist community at large. I agree. And I heartily endorse an open forum for this process.

What happens after this is somewhat less clear, but it involves synthesis of all of the input and presentation to the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (JCPHM). In addition, the American Pediatric Association (APA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and SHM representatives will solicit feedback from their leadership and membership. A minor drawback of this process is the fact that the JCPHM remains a somewhat mythical body to date, as it has not been publicly defined to my knowledge. But this will be the body that makes the final decision.

The Candidates

OK, enough of the sausage-making (“laws are like sausages: It is best not to see them being made”) and on to the actual candidates. I suppose we should begin with the “incumbent”—the status quo. I will not rehash the pros and cons that have been meticulously laid out by the STP Committee on the website. But I will add that this candidate has the benefit of being well-known and is the least complicated option. Unfortunately, it’s also the least sexy option, which I’m told is actually a factor in elections. Given the number of alternatives that the committee has laid out, I’m not going with this one, simply because there has to be a better one out there.

I also immediately discount the option on the other end of the spectrum: a full three-year fellowship (the current standard for subspecialists). We’re all familiar with the details of this option, but the year of research is, on average, a bigger waste of time than college calculus. I remember a lot of fellows who didn’t care about research; they were sleeping next to me in the clinical research classes, ones that I was taking in my spare time. They completed projects to get through the fellowship, and that was it for “research” in their careers. Now, I can’t exclude the fact that they learned something from those projects, but the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) clearly states that the “rationale for including a requirement for participation in scholarly activity flows from the belief that the principal goal of fellowship training should be the development of future academic pediatricians.”1 Practice in a community hospital is quite different from that of an academic pediatrician.

(This is not to say that we do not need a pipeline of future academic leaders, an absolute necessity for our young field. However, if we are to decide certification options for everyone, I think we should focus on a set of minimum requirements and have additional options, or tracks, for academicians. Thus, I would reframe the debate to focus on what every hospitalist needs.)

What is really needed to train effective pediatric hospitalists? I think we begin by acknowledging that additional clinical training is a priority for several reasons:

- Pediatric residents are receiving less and less inpatient training;

- Our patients are increasingly complex; and

- The hospital is a unique and complicated system within which to practice.

I was trained in the good ol’ days, before duty hours, and I was still pretty dumb when I started as an attending. While I don’t think it’s difficult for new grads to learn on the job, once you pay someone a full salary and give them billing as a full-fledged attending, you lose a lot of leeway—on both sides—to structure their education.

Some standard of quality and safety training should be included in this minimum requirement. One byproduct of the quality movement in medicine is that we now clearly understand that hospitals are complex systems with many moving parts. Interacting in that system, and providing safe and effective care within those confines, requires a certain set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills—particularly if we are to be leaders in hospital practice. It is no longer sufficient to be just a hospital-based doctor with no extramural involvement in improving the system. Strategically, this would be of value to both hospital administrators and academic institutions, our primary funding streams.

The Endorsement

So I vote for some set of minimum requirements. And I think that has to be the focus of our initial discussion. Once those are decided, the immediate next issue should be whether this is implemented as a fellowship or through focused practice. Here, I lean towards the former, as I think that a fellowship allows us to better control the quality of that training. The final issue is which option to choose, but I think that becomes a formality once minimum requirements are decided; in many instances, there may be more than one option that works.

So do your part, and contribute to the discussion. But don’t just pick an option. Describe what you think hospitalists of tomorrow need when they start their careers. And enjoy this refreshing process, one without the irrationalities of politics and something that we can all buy into for the future of pediatric HM.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist and medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas.

Reference

I am decidedly anti-politics. The entire process seems fatally flawed. The vast majority of the public votes based on one or two emotional interests, such as religion or personal finances. The candidates’ responses are calculated, based on the millions of dollars they receive from competing interest groups and evidence-based analysis of what will garner the most votes. So for me at this time of year, watching debates and TV coverage of primaries is akin to watching an MTV reality show—lots of drama, little substance.

But there is one election (of sorts) this year that gives me hope: Our input has been solicited by the Strategic Planning (STP) Committee to help sort through the issue of certification in pediatric hospital medicine. What is potentially at stake here is how we define ourselves as a field. At one end is the traditional, three-year fellowship with certification as a subspecialty. At the other end is no change, or the status quo. In between are myriad options, each with unique pros and cons. It is all summarized at the STP blog (http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com), which allows for input.

This is a unique opportunity, as pediatric HM is at a crossroads. The STP Committee states that this solicitation of public comment is different from processes that other fields (pediatric emergency medicine, child abuse, adult hospital medicine) have used, and it will allow for more engagement of the pediatric hospitalist community at large. I agree. And I heartily endorse an open forum for this process.

What happens after this is somewhat less clear, but it involves synthesis of all of the input and presentation to the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (JCPHM). In addition, the American Pediatric Association (APA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and SHM representatives will solicit feedback from their leadership and membership. A minor drawback of this process is the fact that the JCPHM remains a somewhat mythical body to date, as it has not been publicly defined to my knowledge. But this will be the body that makes the final decision.

The Candidates

OK, enough of the sausage-making (“laws are like sausages: It is best not to see them being made”) and on to the actual candidates. I suppose we should begin with the “incumbent”—the status quo. I will not rehash the pros and cons that have been meticulously laid out by the STP Committee on the website. But I will add that this candidate has the benefit of being well-known and is the least complicated option. Unfortunately, it’s also the least sexy option, which I’m told is actually a factor in elections. Given the number of alternatives that the committee has laid out, I’m not going with this one, simply because there has to be a better one out there.

I also immediately discount the option on the other end of the spectrum: a full three-year fellowship (the current standard for subspecialists). We’re all familiar with the details of this option, but the year of research is, on average, a bigger waste of time than college calculus. I remember a lot of fellows who didn’t care about research; they were sleeping next to me in the clinical research classes, ones that I was taking in my spare time. They completed projects to get through the fellowship, and that was it for “research” in their careers. Now, I can’t exclude the fact that they learned something from those projects, but the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) clearly states that the “rationale for including a requirement for participation in scholarly activity flows from the belief that the principal goal of fellowship training should be the development of future academic pediatricians.”1 Practice in a community hospital is quite different from that of an academic pediatrician.

(This is not to say that we do not need a pipeline of future academic leaders, an absolute necessity for our young field. However, if we are to decide certification options for everyone, I think we should focus on a set of minimum requirements and have additional options, or tracks, for academicians. Thus, I would reframe the debate to focus on what every hospitalist needs.)

What is really needed to train effective pediatric hospitalists? I think we begin by acknowledging that additional clinical training is a priority for several reasons:

- Pediatric residents are receiving less and less inpatient training;

- Our patients are increasingly complex; and

- The hospital is a unique and complicated system within which to practice.

I was trained in the good ol’ days, before duty hours, and I was still pretty dumb when I started as an attending. While I don’t think it’s difficult for new grads to learn on the job, once you pay someone a full salary and give them billing as a full-fledged attending, you lose a lot of leeway—on both sides—to structure their education.

Some standard of quality and safety training should be included in this minimum requirement. One byproduct of the quality movement in medicine is that we now clearly understand that hospitals are complex systems with many moving parts. Interacting in that system, and providing safe and effective care within those confines, requires a certain set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills—particularly if we are to be leaders in hospital practice. It is no longer sufficient to be just a hospital-based doctor with no extramural involvement in improving the system. Strategically, this would be of value to both hospital administrators and academic institutions, our primary funding streams.

The Endorsement

So I vote for some set of minimum requirements. And I think that has to be the focus of our initial discussion. Once those are decided, the immediate next issue should be whether this is implemented as a fellowship or through focused practice. Here, I lean towards the former, as I think that a fellowship allows us to better control the quality of that training. The final issue is which option to choose, but I think that becomes a formality once minimum requirements are decided; in many instances, there may be more than one option that works.

So do your part, and contribute to the discussion. But don’t just pick an option. Describe what you think hospitalists of tomorrow need when they start their careers. And enjoy this refreshing process, one without the irrationalities of politics and something that we can all buy into for the future of pediatric HM.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist and medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas.

Reference

I am decidedly anti-politics. The entire process seems fatally flawed. The vast majority of the public votes based on one or two emotional interests, such as religion or personal finances. The candidates’ responses are calculated, based on the millions of dollars they receive from competing interest groups and evidence-based analysis of what will garner the most votes. So for me at this time of year, watching debates and TV coverage of primaries is akin to watching an MTV reality show—lots of drama, little substance.

But there is one election (of sorts) this year that gives me hope: Our input has been solicited by the Strategic Planning (STP) Committee to help sort through the issue of certification in pediatric hospital medicine. What is potentially at stake here is how we define ourselves as a field. At one end is the traditional, three-year fellowship with certification as a subspecialty. At the other end is no change, or the status quo. In between are myriad options, each with unique pros and cons. It is all summarized at the STP blog (http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com), which allows for input.

This is a unique opportunity, as pediatric HM is at a crossroads. The STP Committee states that this solicitation of public comment is different from processes that other fields (pediatric emergency medicine, child abuse, adult hospital medicine) have used, and it will allow for more engagement of the pediatric hospitalist community at large. I agree. And I heartily endorse an open forum for this process.

What happens after this is somewhat less clear, but it involves synthesis of all of the input and presentation to the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (JCPHM). In addition, the American Pediatric Association (APA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and SHM representatives will solicit feedback from their leadership and membership. A minor drawback of this process is the fact that the JCPHM remains a somewhat mythical body to date, as it has not been publicly defined to my knowledge. But this will be the body that makes the final decision.

The Candidates

OK, enough of the sausage-making (“laws are like sausages: It is best not to see them being made”) and on to the actual candidates. I suppose we should begin with the “incumbent”—the status quo. I will not rehash the pros and cons that have been meticulously laid out by the STP Committee on the website. But I will add that this candidate has the benefit of being well-known and is the least complicated option. Unfortunately, it’s also the least sexy option, which I’m told is actually a factor in elections. Given the number of alternatives that the committee has laid out, I’m not going with this one, simply because there has to be a better one out there.

I also immediately discount the option on the other end of the spectrum: a full three-year fellowship (the current standard for subspecialists). We’re all familiar with the details of this option, but the year of research is, on average, a bigger waste of time than college calculus. I remember a lot of fellows who didn’t care about research; they were sleeping next to me in the clinical research classes, ones that I was taking in my spare time. They completed projects to get through the fellowship, and that was it for “research” in their careers. Now, I can’t exclude the fact that they learned something from those projects, but the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) clearly states that the “rationale for including a requirement for participation in scholarly activity flows from the belief that the principal goal of fellowship training should be the development of future academic pediatricians.”1 Practice in a community hospital is quite different from that of an academic pediatrician.

(This is not to say that we do not need a pipeline of future academic leaders, an absolute necessity for our young field. However, if we are to decide certification options for everyone, I think we should focus on a set of minimum requirements and have additional options, or tracks, for academicians. Thus, I would reframe the debate to focus on what every hospitalist needs.)

What is really needed to train effective pediatric hospitalists? I think we begin by acknowledging that additional clinical training is a priority for several reasons:

- Pediatric residents are receiving less and less inpatient training;

- Our patients are increasingly complex; and

- The hospital is a unique and complicated system within which to practice.

I was trained in the good ol’ days, before duty hours, and I was still pretty dumb when I started as an attending. While I don’t think it’s difficult for new grads to learn on the job, once you pay someone a full salary and give them billing as a full-fledged attending, you lose a lot of leeway—on both sides—to structure their education.

Some standard of quality and safety training should be included in this minimum requirement. One byproduct of the quality movement in medicine is that we now clearly understand that hospitals are complex systems with many moving parts. Interacting in that system, and providing safe and effective care within those confines, requires a certain set of knowledge, attitudes, and skills—particularly if we are to be leaders in hospital practice. It is no longer sufficient to be just a hospital-based doctor with no extramural involvement in improving the system. Strategically, this would be of value to both hospital administrators and academic institutions, our primary funding streams.

The Endorsement

So I vote for some set of minimum requirements. And I think that has to be the focus of our initial discussion. Once those are decided, the immediate next issue should be whether this is implemented as a fellowship or through focused practice. Here, I lean towards the former, as I think that a fellowship allows us to better control the quality of that training. The final issue is which option to choose, but I think that becomes a formality once minimum requirements are decided; in many instances, there may be more than one option that works.

So do your part, and contribute to the discussion. But don’t just pick an option. Describe what you think hospitalists of tomorrow need when they start their careers. And enjoy this refreshing process, one without the irrationalities of politics and something that we can all buy into for the future of pediatric HM.

Dr. Shen is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist and medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas.

Reference

Change Happens—Make Sure You Are Prepared

Change Happens—Make Sure You Are Prepared

My hospitalist group is imploding. What do I do?

—Concerned in Georgia

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Well, if there is one thing HM lacks, it’s certainty. When I first started out as a hospitalist oh-so-many years ago (it was the 1990s), our field was nascent, and we all figured we’d do this for a year or two, then be out of a job. Once it became clear that the work was here to stay, the day-to-day unpredictability of the job came to the fore. How would we ever get to level staffing? How was it possible to get 20 admissions one day and two the next? Why would you have a unit full of raging, naked, withdrawing alcoholics one week, and the next, your service would be sweet grandmas who broke their hips? I mean, variety can be delightful, but yeesh, this was nuts.

Fast-forward to 2012, and HM is here to stay. The volumes may vary, but the work isn’t going away—and primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t coming back to make rounds. The uncertainty still exists, but it centers more around insurance payments (27% pay cut narrowly avoided!), hospital contracts, and employment models. This scenario is by no means unique to hospitalists. Just look at the wrenching changes that the cardiologists have gone through in the past few years with the cut in outpatient procedure payments. For better or for worse, even in HM Year 15+, change is the only constant.

Your group is imploding. There are a few scenarios there:

- Maybe you’ve been mismanaged (been there);

- Perhaps the hospital decided not to renew your contract (been there, too);

- Your group was acquired by a larger group; or

- Another local group just took a big chunk of your business, and that means staffing cuts.

My point is, whether all or none of these situations have ever happened to you as a hospitalist, they all exist. I just don’t think you can safely look at any physician job in 2012 and say, “Yeah, this job will be good for the next 10 years.” We have way too much uncertainty in the business model. This is not to say that the profession is going to deteriorate, but that you need to be prepared for ongoing evolution.

If luck is the product of preparation and opportunity, then disaster comes from complacency and assumption. So keep your CV updated. No need to broadcast it; just pull up the file once a year and make the needed changes. Expand your skill set. FCCS certification might make sense if you do a lot of ICU work. Document your committee experience (don’t tell me your hospital committees are all full).

Apply for Fellow in Hospital Medicine designation (www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellow). Maintain your certification through the Focused Practice in HM pathway (www.abim.org).

Maintain your connections, whether it’s through local chapter meetings and CME or attending SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine.org/events).

Know the work environment in your community: Which job would you take if your current one went away?

Even if you are reading this thinking, “There is just no way this kind of change could happen to my group,” trust me, it can. And quickly. You should expect change, and know what your options are when it comes along.

Change Happens—Make Sure You Are Prepared

My hospitalist group is imploding. What do I do?

—Concerned in Georgia

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Well, if there is one thing HM lacks, it’s certainty. When I first started out as a hospitalist oh-so-many years ago (it was the 1990s), our field was nascent, and we all figured we’d do this for a year or two, then be out of a job. Once it became clear that the work was here to stay, the day-to-day unpredictability of the job came to the fore. How would we ever get to level staffing? How was it possible to get 20 admissions one day and two the next? Why would you have a unit full of raging, naked, withdrawing alcoholics one week, and the next, your service would be sweet grandmas who broke their hips? I mean, variety can be delightful, but yeesh, this was nuts.

Fast-forward to 2012, and HM is here to stay. The volumes may vary, but the work isn’t going away—and primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t coming back to make rounds. The uncertainty still exists, but it centers more around insurance payments (27% pay cut narrowly avoided!), hospital contracts, and employment models. This scenario is by no means unique to hospitalists. Just look at the wrenching changes that the cardiologists have gone through in the past few years with the cut in outpatient procedure payments. For better or for worse, even in HM Year 15+, change is the only constant.

Your group is imploding. There are a few scenarios there:

- Maybe you’ve been mismanaged (been there);

- Perhaps the hospital decided not to renew your contract (been there, too);

- Your group was acquired by a larger group; or

- Another local group just took a big chunk of your business, and that means staffing cuts.

My point is, whether all or none of these situations have ever happened to you as a hospitalist, they all exist. I just don’t think you can safely look at any physician job in 2012 and say, “Yeah, this job will be good for the next 10 years.” We have way too much uncertainty in the business model. This is not to say that the profession is going to deteriorate, but that you need to be prepared for ongoing evolution.

If luck is the product of preparation and opportunity, then disaster comes from complacency and assumption. So keep your CV updated. No need to broadcast it; just pull up the file once a year and make the needed changes. Expand your skill set. FCCS certification might make sense if you do a lot of ICU work. Document your committee experience (don’t tell me your hospital committees are all full).

Apply for Fellow in Hospital Medicine designation (www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellow). Maintain your certification through the Focused Practice in HM pathway (www.abim.org).

Maintain your connections, whether it’s through local chapter meetings and CME or attending SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine.org/events).

Know the work environment in your community: Which job would you take if your current one went away?

Even if you are reading this thinking, “There is just no way this kind of change could happen to my group,” trust me, it can. And quickly. You should expect change, and know what your options are when it comes along.

Change Happens—Make Sure You Are Prepared

My hospitalist group is imploding. What do I do?

—Concerned in Georgia

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Well, if there is one thing HM lacks, it’s certainty. When I first started out as a hospitalist oh-so-many years ago (it was the 1990s), our field was nascent, and we all figured we’d do this for a year or two, then be out of a job. Once it became clear that the work was here to stay, the day-to-day unpredictability of the job came to the fore. How would we ever get to level staffing? How was it possible to get 20 admissions one day and two the next? Why would you have a unit full of raging, naked, withdrawing alcoholics one week, and the next, your service would be sweet grandmas who broke their hips? I mean, variety can be delightful, but yeesh, this was nuts.

Fast-forward to 2012, and HM is here to stay. The volumes may vary, but the work isn’t going away—and primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t coming back to make rounds. The uncertainty still exists, but it centers more around insurance payments (27% pay cut narrowly avoided!), hospital contracts, and employment models. This scenario is by no means unique to hospitalists. Just look at the wrenching changes that the cardiologists have gone through in the past few years with the cut in outpatient procedure payments. For better or for worse, even in HM Year 15+, change is the only constant.

Your group is imploding. There are a few scenarios there:

- Maybe you’ve been mismanaged (been there);

- Perhaps the hospital decided not to renew your contract (been there, too);

- Your group was acquired by a larger group; or

- Another local group just took a big chunk of your business, and that means staffing cuts.

My point is, whether all or none of these situations have ever happened to you as a hospitalist, they all exist. I just don’t think you can safely look at any physician job in 2012 and say, “Yeah, this job will be good for the next 10 years.” We have way too much uncertainty in the business model. This is not to say that the profession is going to deteriorate, but that you need to be prepared for ongoing evolution.

If luck is the product of preparation and opportunity, then disaster comes from complacency and assumption. So keep your CV updated. No need to broadcast it; just pull up the file once a year and make the needed changes. Expand your skill set. FCCS certification might make sense if you do a lot of ICU work. Document your committee experience (don’t tell me your hospital committees are all full).

Apply for Fellow in Hospital Medicine designation (www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellow). Maintain your certification through the Focused Practice in HM pathway (www.abim.org).

Maintain your connections, whether it’s through local chapter meetings and CME or attending SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine.org/events).

Know the work environment in your community: Which job would you take if your current one went away?

Even if you are reading this thinking, “There is just no way this kind of change could happen to my group,” trust me, it can. And quickly. You should expect change, and know what your options are when it comes along.

HHS Delays ICD-10 Compliance Date

According to a CMS statement regarding part of President Obama’s “commitment to reducing regulatory burden,” Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius announced that HHS will initiate a process to “postpone the date” by which certain healthcare entities have to comply with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10).1

The final rule adopting ICD-10 as a standard was published in January 2009; it set a compliance date of Oct. 1, 2013 (a two-year delay from the 2008 proposed rule). HHS will announce a new compliance date moving forward.

“ICD-10 codes are important to many positive improvements in our healthcare system,” Sebelius said in the statement. “We have heard from many in the provider community who have concerns about the administrative burdens they face in the years ahead. We are committing to work with the provider community to re-examine the pace at which HHS and the nation implement these important improvements to our healthcare system.”

ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our healthcare data with that of the rest of the world, much of which has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes.

All that said, do not postpone any activities toward ICD-10 implementation until further clarification comes from CMS.

—Carol Pohlig

Reference

According to a CMS statement regarding part of President Obama’s “commitment to reducing regulatory burden,” Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius announced that HHS will initiate a process to “postpone the date” by which certain healthcare entities have to comply with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10).1

The final rule adopting ICD-10 as a standard was published in January 2009; it set a compliance date of Oct. 1, 2013 (a two-year delay from the 2008 proposed rule). HHS will announce a new compliance date moving forward.

“ICD-10 codes are important to many positive improvements in our healthcare system,” Sebelius said in the statement. “We have heard from many in the provider community who have concerns about the administrative burdens they face in the years ahead. We are committing to work with the provider community to re-examine the pace at which HHS and the nation implement these important improvements to our healthcare system.”

ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our healthcare data with that of the rest of the world, much of which has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes.

All that said, do not postpone any activities toward ICD-10 implementation until further clarification comes from CMS.

—Carol Pohlig

Reference

According to a CMS statement regarding part of President Obama’s “commitment to reducing regulatory burden,” Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen G. Sebelius announced that HHS will initiate a process to “postpone the date” by which certain healthcare entities have to comply with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition diagnosis and procedure codes (ICD-10).1

The final rule adopting ICD-10 as a standard was published in January 2009; it set a compliance date of Oct. 1, 2013 (a two-year delay from the 2008 proposed rule). HHS will announce a new compliance date moving forward.

“ICD-10 codes are important to many positive improvements in our healthcare system,” Sebelius said in the statement. “We have heard from many in the provider community who have concerns about the administrative burdens they face in the years ahead. We are committing to work with the provider community to re-examine the pace at which HHS and the nation implement these important improvements to our healthcare system.”

ICD-10 codes provide more robust and specific data that will help improve patient care and enable the exchange of our healthcare data with that of the rest of the world, much of which has long been using ICD-10. Entities covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) will be required to use the ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes.

All that said, do not postpone any activities toward ICD-10 implementation until further clarification comes from CMS.

—Carol Pohlig

Reference

A Brief Look at Stroke Research

Aggressive medical management: thumbs up

Among stroke patients with intracranial stenosis, or the narrowing of arteries within the brain, researchers found that aggressive medical therapy and attention to risk factors outperformed a combination of drugs and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting (PTAS) in preventing stroke recurrence.11 The immediate conclusions might apply to a specific condition and be due in part to a tricky surgical stenting procedure, but experts including Dr. Likosky say it’s also indicative of the power of medical management when done appropriately. Doctors can readily adopt core elements of this therapeutic intervention, including adding clopidogrel to aspirin for the first three months, and helping patients lower their blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

Neuroimaging: thumbs up

Advanced imaging techniques like diffusion-weighted MRI (which uses the movement of water as a lens to produce a detailed map of stroke-damaged brain tissues and vessels) are helping doctors determine the best course of therapy. Evidence of a salvageable ischemic brain, Dr. Jensen says, can help make the case for interarterial removal of the obstruction. And finer resolution can help differentiate between a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and a true stroke.

Neuroprotective agents: thumbs down

Researchers have examined the potential for a range of medications to limit the amount of neurological damage after a stroke. So far, at least, none have proven to be very effective. “We just haven’t found the magic bullet,” Dr. Jensen says. “Of course, that would be the most wonderful thing in the world because you could put them in people’s houses and say, ‘If you think you’re having a stroke, start taking these pills,’ but we’re just not there yet.”

“Stent on a stick”: thumbs up

The standard FDA-approved mechanical clot remover, a helical-shaped device called the Merci Retriever, acts like a corkscrew to spear and dislodge clots, while a machine known as Penumbra does its job through suction. After showing promise in Europe, two next-generation stent retrievers, the Trevo and the Solitaire, could give the established techniques a run for their money in the U.S.

At February’s International Stroke Conference in New Orleans, researchers reported that the Solitaire (sometimes called a concentric retriever, or a “stent on a stick”) significantly outperformed the Merci in several measures of patient outcomes. The randomized, controlled SWIFT clinical trial, in fact, ended earlier than planned because the results were so promising. Clinicians recorded a three-month mortality rate of 17.2% for patients treated with Solitaire, compared with a 38.2% rate among Merci-treated patients. In addition, the trial recorded good mental and motor functions among 58.2% of Solitaire patients at three months, but only among 33.3% of the Merci cohort. At the same conference, researchers reported that a prospective European trial of the Trevo system yielded similarly encouraging results.

Aggressive medical management: thumbs up

Among stroke patients with intracranial stenosis, or the narrowing of arteries within the brain, researchers found that aggressive medical therapy and attention to risk factors outperformed a combination of drugs and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting (PTAS) in preventing stroke recurrence.11 The immediate conclusions might apply to a specific condition and be due in part to a tricky surgical stenting procedure, but experts including Dr. Likosky say it’s also indicative of the power of medical management when done appropriately. Doctors can readily adopt core elements of this therapeutic intervention, including adding clopidogrel to aspirin for the first three months, and helping patients lower their blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

Neuroimaging: thumbs up

Advanced imaging techniques like diffusion-weighted MRI (which uses the movement of water as a lens to produce a detailed map of stroke-damaged brain tissues and vessels) are helping doctors determine the best course of therapy. Evidence of a salvageable ischemic brain, Dr. Jensen says, can help make the case for interarterial removal of the obstruction. And finer resolution can help differentiate between a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and a true stroke.

Neuroprotective agents: thumbs down

Researchers have examined the potential for a range of medications to limit the amount of neurological damage after a stroke. So far, at least, none have proven to be very effective. “We just haven’t found the magic bullet,” Dr. Jensen says. “Of course, that would be the most wonderful thing in the world because you could put them in people’s houses and say, ‘If you think you’re having a stroke, start taking these pills,’ but we’re just not there yet.”

“Stent on a stick”: thumbs up

The standard FDA-approved mechanical clot remover, a helical-shaped device called the Merci Retriever, acts like a corkscrew to spear and dislodge clots, while a machine known as Penumbra does its job through suction. After showing promise in Europe, two next-generation stent retrievers, the Trevo and the Solitaire, could give the established techniques a run for their money in the U.S.

At February’s International Stroke Conference in New Orleans, researchers reported that the Solitaire (sometimes called a concentric retriever, or a “stent on a stick”) significantly outperformed the Merci in several measures of patient outcomes. The randomized, controlled SWIFT clinical trial, in fact, ended earlier than planned because the results were so promising. Clinicians recorded a three-month mortality rate of 17.2% for patients treated with Solitaire, compared with a 38.2% rate among Merci-treated patients. In addition, the trial recorded good mental and motor functions among 58.2% of Solitaire patients at three months, but only among 33.3% of the Merci cohort. At the same conference, researchers reported that a prospective European trial of the Trevo system yielded similarly encouraging results.

Aggressive medical management: thumbs up

Among stroke patients with intracranial stenosis, or the narrowing of arteries within the brain, researchers found that aggressive medical therapy and attention to risk factors outperformed a combination of drugs and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting (PTAS) in preventing stroke recurrence.11 The immediate conclusions might apply to a specific condition and be due in part to a tricky surgical stenting procedure, but experts including Dr. Likosky say it’s also indicative of the power of medical management when done appropriately. Doctors can readily adopt core elements of this therapeutic intervention, including adding clopidogrel to aspirin for the first three months, and helping patients lower their blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

Neuroimaging: thumbs up

Advanced imaging techniques like diffusion-weighted MRI (which uses the movement of water as a lens to produce a detailed map of stroke-damaged brain tissues and vessels) are helping doctors determine the best course of therapy. Evidence of a salvageable ischemic brain, Dr. Jensen says, can help make the case for interarterial removal of the obstruction. And finer resolution can help differentiate between a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and a true stroke.

Neuroprotective agents: thumbs down

Researchers have examined the potential for a range of medications to limit the amount of neurological damage after a stroke. So far, at least, none have proven to be very effective. “We just haven’t found the magic bullet,” Dr. Jensen says. “Of course, that would be the most wonderful thing in the world because you could put them in people’s houses and say, ‘If you think you’re having a stroke, start taking these pills,’ but we’re just not there yet.”

“Stent on a stick”: thumbs up

The standard FDA-approved mechanical clot remover, a helical-shaped device called the Merci Retriever, acts like a corkscrew to spear and dislodge clots, while a machine known as Penumbra does its job through suction. After showing promise in Europe, two next-generation stent retrievers, the Trevo and the Solitaire, could give the established techniques a run for their money in the U.S.

At February’s International Stroke Conference in New Orleans, researchers reported that the Solitaire (sometimes called a concentric retriever, or a “stent on a stick”) significantly outperformed the Merci in several measures of patient outcomes. The randomized, controlled SWIFT clinical trial, in fact, ended earlier than planned because the results were so promising. Clinicians recorded a three-month mortality rate of 17.2% for patients treated with Solitaire, compared with a 38.2% rate among Merci-treated patients. In addition, the trial recorded good mental and motor functions among 58.2% of Solitaire patients at three months, but only among 33.3% of the Merci cohort. At the same conference, researchers reported that a prospective European trial of the Trevo system yielded similarly encouraging results.

Communication Vital to End-of-Life Care

A year ago in March, I looked my father in the eyes for the last time as he mouthed the words "help me" from his ICU bed. But despite being surrounded by teams of medical personnel and the latest healthcare technology, I felt utterly powerless to make a clear decision—and unclear to whom to turn for sound advice.

After 30 days of care in a well-known teaching hospital in the Northeast, my father was about to succumb to Stage 4 lung cancer, a tumor invading his spine. Moments before his plea, the ICU team had conducted a breathing test that apparently went awry—beginning the trial while my mother and I were downstairs receiving the latest round of conflicting information from a pair of doctors debating his outlook for discharge, physical rehabilitation, and hospice care. They casually informed us that a breathing test was about to occur; we rushed back to my father's side to learn the unfortunate outcome.

Prior to the episode that led to his being moved to the ICU, my father had been residing in a room directly across from a small hospitalist oncology office. What ensued was dizzying to behold: an endless parade of consultations; a narrowly averted million-dollar-plus spinal surgery in the wee hours; a too-zealous resident's further injuring of my father's right leg, which had already been compromised by a tumor degrading the femur.

My mother, my wife, and I struggled to maintain Dad's always-indomitable spirit while parsing the barrage of input regarding his potential for quality of life outside the hospital. We sat in numerous meetings, often with a pair of doctors espousing diametrically opposed outlooks. We tried to keep track of whom we were speaking with and who was in charge at any given moment; the lists we kept looked like the roster of a sports team, amply covered in scribbled-out names, phone numbers—and question marks.

It was only after my father tried feebly to speak his last words to me that the doctor who'd appeared to be most in charge pulled me aside at the door of the ICU. My mother and I hemmed and hawed in trying to decide whether to accede to another round of heroic measures. I was surprised by the somewhat terse tone of voice this senior physician used in dissuading us from allowing further life-extending efforts. I would have welcomed such honesty wholeheartedly far earlier in the process.

One of the value propositions hospitalists tout to their employers and patients is their expertise in coordinating care and facilitating communication among caregivers. Of course, there are nearly as many methods for doing so as there are hospitalist teams.

As the medical process grows more complex and specialized, with more "stakeholders" weighing in on the conversation, the hospitalist's role in taking charge of and energetically managing the flow of information for the benefit of beleaguered kin is more vital than ever. I can't speak for all loved ones who must witness the passage of a parent, a child, or a spouse, but for me, a hospitalist's firm hand would have made a world of difference in how we navigated this inevitable event.

Geoff Giordano was editor of The Hospitalist from 2007 to 2008. His father, Thomas, a lifelong journalist, wrote several articles for the magazine during that period.

A year ago in March, I looked my father in the eyes for the last time as he mouthed the words "help me" from his ICU bed. But despite being surrounded by teams of medical personnel and the latest healthcare technology, I felt utterly powerless to make a clear decision—and unclear to whom to turn for sound advice.

After 30 days of care in a well-known teaching hospital in the Northeast, my father was about to succumb to Stage 4 lung cancer, a tumor invading his spine. Moments before his plea, the ICU team had conducted a breathing test that apparently went awry—beginning the trial while my mother and I were downstairs receiving the latest round of conflicting information from a pair of doctors debating his outlook for discharge, physical rehabilitation, and hospice care. They casually informed us that a breathing test was about to occur; we rushed back to my father's side to learn the unfortunate outcome.

Prior to the episode that led to his being moved to the ICU, my father had been residing in a room directly across from a small hospitalist oncology office. What ensued was dizzying to behold: an endless parade of consultations; a narrowly averted million-dollar-plus spinal surgery in the wee hours; a too-zealous resident's further injuring of my father's right leg, which had already been compromised by a tumor degrading the femur.

My mother, my wife, and I struggled to maintain Dad's always-indomitable spirit while parsing the barrage of input regarding his potential for quality of life outside the hospital. We sat in numerous meetings, often with a pair of doctors espousing diametrically opposed outlooks. We tried to keep track of whom we were speaking with and who was in charge at any given moment; the lists we kept looked like the roster of a sports team, amply covered in scribbled-out names, phone numbers—and question marks.

It was only after my father tried feebly to speak his last words to me that the doctor who'd appeared to be most in charge pulled me aside at the door of the ICU. My mother and I hemmed and hawed in trying to decide whether to accede to another round of heroic measures. I was surprised by the somewhat terse tone of voice this senior physician used in dissuading us from allowing further life-extending efforts. I would have welcomed such honesty wholeheartedly far earlier in the process.

One of the value propositions hospitalists tout to their employers and patients is their expertise in coordinating care and facilitating communication among caregivers. Of course, there are nearly as many methods for doing so as there are hospitalist teams.

As the medical process grows more complex and specialized, with more "stakeholders" weighing in on the conversation, the hospitalist's role in taking charge of and energetically managing the flow of information for the benefit of beleaguered kin is more vital than ever. I can't speak for all loved ones who must witness the passage of a parent, a child, or a spouse, but for me, a hospitalist's firm hand would have made a world of difference in how we navigated this inevitable event.

Geoff Giordano was editor of The Hospitalist from 2007 to 2008. His father, Thomas, a lifelong journalist, wrote several articles for the magazine during that period.

A year ago in March, I looked my father in the eyes for the last time as he mouthed the words "help me" from his ICU bed. But despite being surrounded by teams of medical personnel and the latest healthcare technology, I felt utterly powerless to make a clear decision—and unclear to whom to turn for sound advice.

After 30 days of care in a well-known teaching hospital in the Northeast, my father was about to succumb to Stage 4 lung cancer, a tumor invading his spine. Moments before his plea, the ICU team had conducted a breathing test that apparently went awry—beginning the trial while my mother and I were downstairs receiving the latest round of conflicting information from a pair of doctors debating his outlook for discharge, physical rehabilitation, and hospice care. They casually informed us that a breathing test was about to occur; we rushed back to my father's side to learn the unfortunate outcome.

Prior to the episode that led to his being moved to the ICU, my father had been residing in a room directly across from a small hospitalist oncology office. What ensued was dizzying to behold: an endless parade of consultations; a narrowly averted million-dollar-plus spinal surgery in the wee hours; a too-zealous resident's further injuring of my father's right leg, which had already been compromised by a tumor degrading the femur.

My mother, my wife, and I struggled to maintain Dad's always-indomitable spirit while parsing the barrage of input regarding his potential for quality of life outside the hospital. We sat in numerous meetings, often with a pair of doctors espousing diametrically opposed outlooks. We tried to keep track of whom we were speaking with and who was in charge at any given moment; the lists we kept looked like the roster of a sports team, amply covered in scribbled-out names, phone numbers—and question marks.

It was only after my father tried feebly to speak his last words to me that the doctor who'd appeared to be most in charge pulled me aside at the door of the ICU. My mother and I hemmed and hawed in trying to decide whether to accede to another round of heroic measures. I was surprised by the somewhat terse tone of voice this senior physician used in dissuading us from allowing further life-extending efforts. I would have welcomed such honesty wholeheartedly far earlier in the process.

One of the value propositions hospitalists tout to their employers and patients is their expertise in coordinating care and facilitating communication among caregivers. Of course, there are nearly as many methods for doing so as there are hospitalist teams.

As the medical process grows more complex and specialized, with more "stakeholders" weighing in on the conversation, the hospitalist's role in taking charge of and energetically managing the flow of information for the benefit of beleaguered kin is more vital than ever. I can't speak for all loved ones who must witness the passage of a parent, a child, or a spouse, but for me, a hospitalist's firm hand would have made a world of difference in how we navigated this inevitable event.

Geoff Giordano was editor of The Hospitalist from 2007 to 2008. His father, Thomas, a lifelong journalist, wrote several articles for the magazine during that period.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: TK

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: TK

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Weighing the Pros and Cons of ACOs

Regardless of the fate of federal health reform, accountable care organizations will continue to develop because the current system is completely unsustainable.

These organizations are emerging because of the necessity to shift the unsustainable payment for volume in today’s fee-for-service health care delivery system to one that rewards value. ACOs will be judged on the delivery of quality health care while controlling overall costs. In general, ACOs will usually receive about half of the savings if quality standards are met.

This will necessitate a transformative shift from fragmented, episodic care to care that is delivered by teams following best practices across the continuum. Providers will thus be "accountable" to each other to achieve value (defined as the highest quality at the lowest cost), because they must work together to generate a sizable savings pool and to improve a patient population’s health status.

Why are ACOs empowering to primary care physicians?

ACOs will target the following key drivers of value:

• Prevention and wellness.

• Chronic disease management.

• Reduced hospitalizations.

• Improved care transitions.

• Multispecialty comanagement of complex patients.

Primary care physicians play a central role in each of these categories.

As Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform once said: "In order to be accountable for the health and health care of a broad population of patients, an accountable care organization must have one or more primary care practices playing a central role."

In fact, primary care providers are the only type of provider mandated for inclusion in the ACO Shared Savings Program under the Affordable Care Act.

But are ACOs likely to be favorable situations for primary care physicians?

First, let’s consider the pros. Many physicians find that the ACO movement’s emphasis on primary care to be a validation of the reasons they went to medical school. Being asked to guide the health care delivery system and being given the tools to do so is empowering. Leading change that will save lives and improve patient access to care would be deeply fulfilling. There also is, of course, the potential for financial gain. Unlike physicians in other specialties, primary care physicians have many opportunities in ACOs.

On the con side, you are not alone if you feel overworked or burned out, or that you simply do not have the time, resources, or remaining intellectual bandwidth to get involved.

Many have already weathered promises from the "next big thing" that in the end did not work out as advertised. And equal numbers have little capital and no business or legal consultants on retainer, as do other health care stakeholders. Time is stretched tight in many areas of the country that are already feeling the effects of a primary care workforce shortage – and now the ACO model is asking that you take on more responsibility?

But here’s the thing: If primary care physicians do not recognize the magnitude of their role in time, the opportunity for ACO success will pass them by and be replaced by dismal alternatives.

And there are already success stories. Starting with several simple Medicaid initiatives, North Carolina primary care physicians created a statewide confederation of 14 medical home ACO networks. Although the work involved is plentiful, so have been the rewards.

Among them is a renewed empowerment and leverage for their interests when they contract with payers and facilities. In interviews with the networks’ physicians, the consensus is that although much is uncertain, the primary care physicians feel much more prepared to face the changes in health care, having first created the medical home networks that lead to medical home–centric ACOs.

For those primary care physicians who choose to join a hospital, the same pros and cons generally apply. By being on the "inside," employed physicians may actually have more influence to shape a successful ACO that fairly values the role of primary care. However, they may have more difficulty freely associating with an ACO outside of the hospital’s ACO.

Whether you are inside or outside the hospital setting, there is tremendous financial opportunity for primary care providers. Shared savings is based on all costs, including those for hospitalization and drugs. The distribution of the shared savings will be proportional to the relative contribution to the savings. Thus, the percentage going to primary care stands to be considerable.

America cannot afford its current health care system. It is asking physicians to run a new health care system, with primary care at its core. There is a dramatic change of focus, from cost centers in health care to savings centers in health care.

Empowerment is being offered, but primary care must step up in order to enjoy it.

Regardless of the fate of federal health reform, accountable care organizations will continue to develop because the current system is completely unsustainable.

These organizations are emerging because of the necessity to shift the unsustainable payment for volume in today’s fee-for-service health care delivery system to one that rewards value. ACOs will be judged on the delivery of quality health care while controlling overall costs. In general, ACOs will usually receive about half of the savings if quality standards are met.

This will necessitate a transformative shift from fragmented, episodic care to care that is delivered by teams following best practices across the continuum. Providers will thus be "accountable" to each other to achieve value (defined as the highest quality at the lowest cost), because they must work together to generate a sizable savings pool and to improve a patient population’s health status.

Why are ACOs empowering to primary care physicians?

ACOs will target the following key drivers of value:

• Prevention and wellness.

• Chronic disease management.

• Reduced hospitalizations.

• Improved care transitions.

• Multispecialty comanagement of complex patients.

Primary care physicians play a central role in each of these categories.

As Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform once said: "In order to be accountable for the health and health care of a broad population of patients, an accountable care organization must have one or more primary care practices playing a central role."

In fact, primary care providers are the only type of provider mandated for inclusion in the ACO Shared Savings Program under the Affordable Care Act.

But are ACOs likely to be favorable situations for primary care physicians?

First, let’s consider the pros. Many physicians find that the ACO movement’s emphasis on primary care to be a validation of the reasons they went to medical school. Being asked to guide the health care delivery system and being given the tools to do so is empowering. Leading change that will save lives and improve patient access to care would be deeply fulfilling. There also is, of course, the potential for financial gain. Unlike physicians in other specialties, primary care physicians have many opportunities in ACOs.

On the con side, you are not alone if you feel overworked or burned out, or that you simply do not have the time, resources, or remaining intellectual bandwidth to get involved.

Many have already weathered promises from the "next big thing" that in the end did not work out as advertised. And equal numbers have little capital and no business or legal consultants on retainer, as do other health care stakeholders. Time is stretched tight in many areas of the country that are already feeling the effects of a primary care workforce shortage – and now the ACO model is asking that you take on more responsibility?

But here’s the thing: If primary care physicians do not recognize the magnitude of their role in time, the opportunity for ACO success will pass them by and be replaced by dismal alternatives.

And there are already success stories. Starting with several simple Medicaid initiatives, North Carolina primary care physicians created a statewide confederation of 14 medical home ACO networks. Although the work involved is plentiful, so have been the rewards.

Among them is a renewed empowerment and leverage for their interests when they contract with payers and facilities. In interviews with the networks’ physicians, the consensus is that although much is uncertain, the primary care physicians feel much more prepared to face the changes in health care, having first created the medical home networks that lead to medical home–centric ACOs.

For those primary care physicians who choose to join a hospital, the same pros and cons generally apply. By being on the "inside," employed physicians may actually have more influence to shape a successful ACO that fairly values the role of primary care. However, they may have more difficulty freely associating with an ACO outside of the hospital’s ACO.

Whether you are inside or outside the hospital setting, there is tremendous financial opportunity for primary care providers. Shared savings is based on all costs, including those for hospitalization and drugs. The distribution of the shared savings will be proportional to the relative contribution to the savings. Thus, the percentage going to primary care stands to be considerable.

America cannot afford its current health care system. It is asking physicians to run a new health care system, with primary care at its core. There is a dramatic change of focus, from cost centers in health care to savings centers in health care.

Empowerment is being offered, but primary care must step up in order to enjoy it.

Regardless of the fate of federal health reform, accountable care organizations will continue to develop because the current system is completely unsustainable.

These organizations are emerging because of the necessity to shift the unsustainable payment for volume in today’s fee-for-service health care delivery system to one that rewards value. ACOs will be judged on the delivery of quality health care while controlling overall costs. In general, ACOs will usually receive about half of the savings if quality standards are met.

This will necessitate a transformative shift from fragmented, episodic care to care that is delivered by teams following best practices across the continuum. Providers will thus be "accountable" to each other to achieve value (defined as the highest quality at the lowest cost), because they must work together to generate a sizable savings pool and to improve a patient population’s health status.

Why are ACOs empowering to primary care physicians?

ACOs will target the following key drivers of value:

• Prevention and wellness.

• Chronic disease management.

• Reduced hospitalizations.

• Improved care transitions.

• Multispecialty comanagement of complex patients.

Primary care physicians play a central role in each of these categories.

As Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform once said: "In order to be accountable for the health and health care of a broad population of patients, an accountable care organization must have one or more primary care practices playing a central role."

In fact, primary care providers are the only type of provider mandated for inclusion in the ACO Shared Savings Program under the Affordable Care Act.

But are ACOs likely to be favorable situations for primary care physicians?

First, let’s consider the pros. Many physicians find that the ACO movement’s emphasis on primary care to be a validation of the reasons they went to medical school. Being asked to guide the health care delivery system and being given the tools to do so is empowering. Leading change that will save lives and improve patient access to care would be deeply fulfilling. There also is, of course, the potential for financial gain. Unlike physicians in other specialties, primary care physicians have many opportunities in ACOs.

On the con side, you are not alone if you feel overworked or burned out, or that you simply do not have the time, resources, or remaining intellectual bandwidth to get involved.

Many have already weathered promises from the "next big thing" that in the end did not work out as advertised. And equal numbers have little capital and no business or legal consultants on retainer, as do other health care stakeholders. Time is stretched tight in many areas of the country that are already feeling the effects of a primary care workforce shortage – and now the ACO model is asking that you take on more responsibility?

But here’s the thing: If primary care physicians do not recognize the magnitude of their role in time, the opportunity for ACO success will pass them by and be replaced by dismal alternatives.

And there are already success stories. Starting with several simple Medicaid initiatives, North Carolina primary care physicians created a statewide confederation of 14 medical home ACO networks. Although the work involved is plentiful, so have been the rewards.

Among them is a renewed empowerment and leverage for their interests when they contract with payers and facilities. In interviews with the networks’ physicians, the consensus is that although much is uncertain, the primary care physicians feel much more prepared to face the changes in health care, having first created the medical home networks that lead to medical home–centric ACOs.

For those primary care physicians who choose to join a hospital, the same pros and cons generally apply. By being on the "inside," employed physicians may actually have more influence to shape a successful ACO that fairly values the role of primary care. However, they may have more difficulty freely associating with an ACO outside of the hospital’s ACO.

Whether you are inside or outside the hospital setting, there is tremendous financial opportunity for primary care providers. Shared savings is based on all costs, including those for hospitalization and drugs. The distribution of the shared savings will be proportional to the relative contribution to the savings. Thus, the percentage going to primary care stands to be considerable.

America cannot afford its current health care system. It is asking physicians to run a new health care system, with primary care at its core. There is a dramatic change of focus, from cost centers in health care to savings centers in health care.

Empowerment is being offered, but primary care must step up in order to enjoy it.

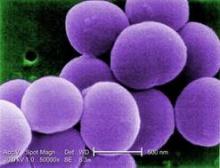

Chlorhexidine-Resistant S. aureus Infections on the Rise

BOSTON – It’s no surprise that antibiotic resistance continues to grow, but now some Staphylococcus aureus are showing off a new trick – resistance to chlorhexidine, the antiseptic relied upon to prevent staph infections.

In a review of isolates from pediatric cancer patients, an increasing number of S. aureus became resistant to the antiseptic, Dr. J. Chase McNeil said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The jump from susceptible to resistant occurred around 2006 – 2 years after the Texas Children’s Hospital began using chlorhexidine in the weekly central line dressing changes for its cancer patients, and a year after the facility introduced chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

"It’s very interesting to see this upward trend [in resistance]," he said in an interview. "Before 2007, we had none, and since then we’ve seen an increase every year."

While the clinical significance of this phenomenon remains unclear, it’s very clear that the bacteria are changing, he added.

Dr. Chase reported a review of a prospectively acquired data set, which includes all children treated at the university’s pediatric oncology facility. He and his coinvestigators looked for infections caused by S. aureus and their related complications. They also assessed the emergence of staph isolates showing the qacA/B gene, which confers a higher minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration to chlorhexidine and other quaternary ammonium compound (QAC) antiseptics. The study also examined rates of methicillin resistance.

From 2001 through 2011, 213 S. aureus infections developed in 179 patients. Infections were most commonly associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (43%). Other cancers were primary central nervous system malignancies (11%), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients (16%). Among the infections were bacteremias (40%), skin and soft tissue infections (36%) and surgical site infections (15%).

Most of the infections were methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (147); the remaining infections were methicillin resistant. Most of the methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates were also the USA300 strain, a particularly resistant strain associated with serious, rapidly progressing infections. The USA300 isolates were responsible for 59% of the skin/soft tissue infections and 25% of the bacteremias.

Overall, 8% of the isolates were also qacA/B positive. These were more likely to be resistant to ciprofloxacin than the qacA/B-negative isolates (50% vs. 15%).

Chlorhexidine-cleansed dressing changes and catheter cleansings began in 2004 in response to a sharp increase in staph infections in AML and HSCT patients, Dr. McNeil said. These infections did drop precipitously in the following years. In 2005, AML patients began using a chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day.

However, in 2006, just as the staph infection rate was improving, qacA/B resistance suddenly appeared. By 2009, 10% of infections were positive for qacA/B, and by 2011, this had risen to about 22%.

"We can’t say if the change in the microbiology of these is caused by anything, or causing anything significant, but there is definitely a temporal association," he said.

Chlorhexidine continues to be relied upon in the oncology ward, he said. By 2011, daily chlorhexidine baths became part of the standard care for neutropenic AML patients.

Among the entire group of patients with infections, 19% (37) developed a total of 58 complications. Bacteremias were associated with most of the complications (70%). A multivariate analysis showed a significant association between complicated bacteremias and AMC patients with a low lymphocyte count.

Thirteen patients with bacteremia also developed pulmonary nodules. All of these were associated with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates. The nodules developed rapidly, appearing a median of 5 days after bacteremia onset. Six patients were biopsied, with S. aureus cultured from five. One nodule was a metastatic tumor. One other patient with nodules died before culture. This patient had an invasive pulmonary fungal infection.

Dr. McNeil said several factors were significantly associated with staph infections and pulmonary nodules, including HSCT, a low lymphocyte count, and low platelets.

"This isn’t surprising because it’s well known that children with malignancies are at a high risk for staph disease because of their immune compromise and a high exposure to empiric antibiotics and antiseptics."

Dr. McNeil said he had no financial declarations.

BOSTON – It’s no surprise that antibiotic resistance continues to grow, but now some Staphylococcus aureus are showing off a new trick – resistance to chlorhexidine, the antiseptic relied upon to prevent staph infections.

In a review of isolates from pediatric cancer patients, an increasing number of S. aureus became resistant to the antiseptic, Dr. J. Chase McNeil said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The jump from susceptible to resistant occurred around 2006 – 2 years after the Texas Children’s Hospital began using chlorhexidine in the weekly central line dressing changes for its cancer patients, and a year after the facility introduced chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

"It’s very interesting to see this upward trend [in resistance]," he said in an interview. "Before 2007, we had none, and since then we’ve seen an increase every year."

While the clinical significance of this phenomenon remains unclear, it’s very clear that the bacteria are changing, he added.

Dr. Chase reported a review of a prospectively acquired data set, which includes all children treated at the university’s pediatric oncology facility. He and his coinvestigators looked for infections caused by S. aureus and their related complications. They also assessed the emergence of staph isolates showing the qacA/B gene, which confers a higher minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration to chlorhexidine and other quaternary ammonium compound (QAC) antiseptics. The study also examined rates of methicillin resistance.

From 2001 through 2011, 213 S. aureus infections developed in 179 patients. Infections were most commonly associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (43%). Other cancers were primary central nervous system malignancies (11%), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients (16%). Among the infections were bacteremias (40%), skin and soft tissue infections (36%) and surgical site infections (15%).

Most of the infections were methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (147); the remaining infections were methicillin resistant. Most of the methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates were also the USA300 strain, a particularly resistant strain associated with serious, rapidly progressing infections. The USA300 isolates were responsible for 59% of the skin/soft tissue infections and 25% of the bacteremias.

Overall, 8% of the isolates were also qacA/B positive. These were more likely to be resistant to ciprofloxacin than the qacA/B-negative isolates (50% vs. 15%).

Chlorhexidine-cleansed dressing changes and catheter cleansings began in 2004 in response to a sharp increase in staph infections in AML and HSCT patients, Dr. McNeil said. These infections did drop precipitously in the following years. In 2005, AML patients began using a chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day.

However, in 2006, just as the staph infection rate was improving, qacA/B resistance suddenly appeared. By 2009, 10% of infections were positive for qacA/B, and by 2011, this had risen to about 22%.

"We can’t say if the change in the microbiology of these is caused by anything, or causing anything significant, but there is definitely a temporal association," he said.

Chlorhexidine continues to be relied upon in the oncology ward, he said. By 2011, daily chlorhexidine baths became part of the standard care for neutropenic AML patients.

Among the entire group of patients with infections, 19% (37) developed a total of 58 complications. Bacteremias were associated with most of the complications (70%). A multivariate analysis showed a significant association between complicated bacteremias and AMC patients with a low lymphocyte count.

Thirteen patients with bacteremia also developed pulmonary nodules. All of these were associated with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates. The nodules developed rapidly, appearing a median of 5 days after bacteremia onset. Six patients were biopsied, with S. aureus cultured from five. One nodule was a metastatic tumor. One other patient with nodules died before culture. This patient had an invasive pulmonary fungal infection.

Dr. McNeil said several factors were significantly associated with staph infections and pulmonary nodules, including HSCT, a low lymphocyte count, and low platelets.

"This isn’t surprising because it’s well known that children with malignancies are at a high risk for staph disease because of their immune compromise and a high exposure to empiric antibiotics and antiseptics."

Dr. McNeil said he had no financial declarations.

BOSTON – It’s no surprise that antibiotic resistance continues to grow, but now some Staphylococcus aureus are showing off a new trick – resistance to chlorhexidine, the antiseptic relied upon to prevent staph infections.

In a review of isolates from pediatric cancer patients, an increasing number of S. aureus became resistant to the antiseptic, Dr. J. Chase McNeil said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The jump from susceptible to resistant occurred around 2006 – 2 years after the Texas Children’s Hospital began using chlorhexidine in the weekly central line dressing changes for its cancer patients, and a year after the facility introduced chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

"It’s very interesting to see this upward trend [in resistance]," he said in an interview. "Before 2007, we had none, and since then we’ve seen an increase every year."

While the clinical significance of this phenomenon remains unclear, it’s very clear that the bacteria are changing, he added.