User login

These Old Lesions? She’s Had Them for Years …

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP; choice “a”). This condition, caused by an inherited defect of the SART3 gene, is seen mostly on the sun-exposed skin of middle-aged women.

Stasis dermatitis (choice “b”) can cause a number of skin changes, but not the discrete annular lesions seen with DSAP.

Seborrheic keratoses (choice “c”) are common on the legs. However, they don’t display this same morphology.

Nummular eczema (choice “d”) presents with annular papulosquamous lesions (as opposed to the fixed lesions seen with DSAP), often on the legs and lower trunk, but without the thready circumferential scaly border.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's discussion...

DISCUSSION

Leg skin is prey to an astonishing array of problems; many have to do with increased hydrostatic pressure (eg, venous stasis disease), with the almost complete lack of sebaceous glands (eg, nummular eczema), or with the simple fact of being “in harm’s way.” And there is no law that says a given patient can’t have more than one problem at a time, co-existing and serving to confuse the examiner. Such is the case with this patient.

Her concern about possible blood clots is misplaced but understandable. Deep vein thromboses would not present in multiples, would not be on the surface or scaly, and would almost certainly be painful.

The fixed nature of this patient’s scaly lesions is extremely significant—but only if you know about DSAP, which typically manifests in the third decade of life and slowly worsens. The lesions’ highly palpable and unique scaly border makes them hard to leave alone. This might not be a problem except for the warfarin, which makes otherwise minor trauma visible as purpuric macules. Chronic sun damage tends to accentuate them as well. The positive family history is nicely corroborative and quite common.

The brown macules on the patient’s legs are solar lentigines (sun-caused freckles), which many patients (and even younger providers) erroneously call “age spots.” When these individuals become “aged,” they’ll understand that there is no such thing as an age spot.

This patient could easily have had nummular eczema, but not for 30 years! Those lesions, treated or not, will come and go. But not DSAP, about which many questions remain: If they’re caused by sun exposure, why don’t we see them more often on the face and arms? And why don’t we see them on the sun-damaged skin of older men?

If needed, a biopsy could have been performed. It would have been confirmatory of the diagnosis and effectively would have ruled out the other items in the differential, including wart, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic or seborrheic keratosis.

A 65-year-old woman is referred to dermatology with discoloration of her legs that started several weeks ago. Her family suggested it might be “blood clots,” although she has been taking warfarin since she was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation several months ago. Her dermatologic condition is basically asymptomatic, but the patient admits to scratching her legs, saying it’s “hard to leave them alone.” On further questioning, she reveals that she has had “rough places” on her legs for at least 20 years and volunteers that her sister had the same problem, which was diagnosed years ago as “fungal infection.” Both she and her sister spent a great deal of time in the sun as children, long before sunscreen was invented. The patient is otherwise fairly healthy. She takes medication for her lipids, as well as daily vitamins. Her atrial fibrillation is under control and requires no medications other than the warfarin. A great deal of focal discoloration is seen on both legs, circumferentially distributed from well below the knees to just above the ankles. Many of the lesions are brown macules, but more are purplish-red, annular, and scaly. On closer examination, these lesions—the ones the patient says she has had for decades—have a very fine, thready, scaly border that palpation reveals to be tough and adherent. They average about 2 cm in diameter. There are no such lesions noted elsewhere on the patient’s skin. There is, however, abundant evidence of excessive sun exposure, characterized by a multitude of solar lentigines, many fine wrinkles, and extremely thin arm skin.

7 questions to ask when evaluating a noninferiority trial

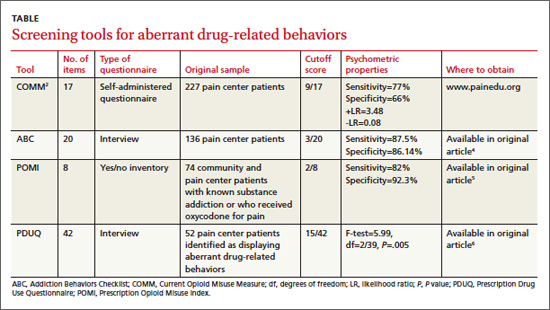

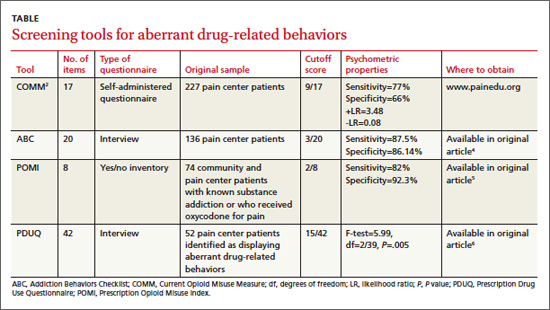

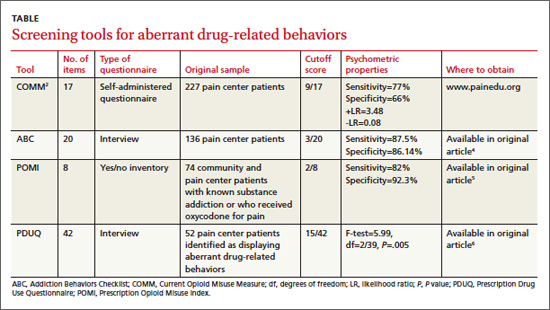

The traditional clinical trial, designed to test whether a new treatment is better than a placebo or another active treatment, is known as a “superiority” trial—although rarely labeled as such. In contrast, the goal of a noninferiority trial is simply to demonstrate that a new treatment is not substantially less effective than the standard therapy.

Such trials are useful when a new therapy is thought to be safer, easier to administer, or less costly than the existing treatment, but not necessarily more effective. And, because it would be unethical to randomize patients with a serious condition for which there already is an effective treatment to placebo, a noninferiority trial is another means of determining if the new treatment is effective.

Noninferiority trials have unique design features and methodology and require a different analysis than traditional superiority trials. Yet many physicians know far less about them; many investigators appear to be less than proficient, as well. A review of 116 noninferiority trials and 46 equivalence trials found that only 20% fulfilled generally accepted quality criteria.1 To improve the quality of noninferiority trials, the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Group has published a checklist for trial design and reporting standards.2,3 Based on this checklist, we came up with 7 key questions to consider when evaluating a noninferiority trial. In the pages that follow, you’ll also find an at-a-glance guide (TABLE) and a methodology review using a hypothetical case (page E7).

1. Is a noninferiority trial appropriate?

The introduction to a noninferiority trial should provide the rationale for this design and the absence of a placebo control group. Look for a review of the evidence of the efficacy of the reference treatment that placebo-controlled trials have revealed, along with the effect size. The advantages of the new treatment over the standard treatment—eg, fewer adverse effects, easier administration, or lower cost—should be discussed, as well.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY)—a prominent noninferiority trial—investigators compared the standard anticoagulant (warfarin) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at risk of stroke with a new agent, dabigatran.4 In the methods section of the abstract and the statistical analysis section of the main body, the authors clearly indicated that this was a noninferiority trial. They began by referring to the existing evidence of warfarin’s effectiveness, then detailed the qualities that make warfarin cumbersome to use, including the need for frequent laboratory monitoring. This was followed by evidence that many patients stop taking warfarin and that even for those who persist with treatment, adequate anticoagulation is difficult to maintain.

The authors went on to state that because dabigatran requires no long-term monitoring, it is easier to use. Therefore, if dabigatran could be shown to be no worse than warfarin in preventing strokes, it would be a reasonable alternative, leaving no doubt that this was an appropriate noninferiority trial.

2. Is the noninferiority margin based on clinical judgment and statistical reasoning?

The noninferiority margin should be based on clinical judgment as to how effective a new treatment must be in order to be declared not clinically inferior to the standard treatment. This can be based on several factors, including the severity of the outcome and the expected advantages of the new treatment. The margin should also take into account the size of the standard treatment’s effect vs placebo. In RELY, for example, the authors noted that the noninferiority margin was based on the desire to preserve at least 50% of the lower limit of the confidence interval (CI) of warfarin’s estimated effect; this was done using data from a previously published meta-analysis of 6 trials comparing warfarin with placebo for stroke prevention in patients with AF.4-6

3. Are the hypothesis and statistical analysis formulated correctly?

The clinical hypothesis in a noninferiority trial is that the new treatment is not worse than the standard treatment by a prespecified margin; therefore, the statistical null hypothesis to be tested is that the new treatment is worse than the reference treatment by more than that margin. Rejecting a true null hypothesis (for example, because the P value is <.05) is known as a type l error. In this setting, making a type I error would mean accepting a new treatment that is truly worse than the standard by at least the specified margin. Failure to reject a false null hypothesis is known as a type II error, which in this case would mean failing to identify a new treatment that is truly noninferior to the standard.7

In RE-LY, the authors stated that the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of a stroke with dabigatran vs warfarin had to fall below 1.46.4 (This is the same as testing the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is ≥1.46.) Thus, the hypothesis was formulated correctly.

4. Is the sample size appropriate and justified?

The sample size in a noninferiority trial should provide high power to reject the null hypothesis that the difference (or relative risk) between groups is equal to or greater than the noninferiority margin under some clinically meaningful assumption about the true difference (or absolute risk reduction) between groups. A true difference of 0 (or a relative risk of 1) is typically assumed for sample size calculation. However, assuming that the new treatment is truly slightly better or slightly worse than the standard may be clinically appropriate in some cases. This would indicate a need for a smaller or larger sample size, respectively, than that required under the usual assumption of no difference.

When the justification for the sample size in a noninferiority trial is not provided or the number of participants is based on an inappropriate approach (eg, using superiority trial calculations for a noninferiority trial), questions about the quality of the trial arise. The primary concern is whether the noninferiority margin was actually selected before the trial began, as it should have been. And if the researchers used overly optimistic assumptions about the efficacy of the new treatment relative to the standard therapy, the failure to rule out the margin could be misleading. (As with superiority trials that fail to reject the null hypothesis, post hoc power calculations should be avoided.) After the study has ended, the resulting CIs should be used to evaluate whether the study was large enough to adequately assess the relative effectiveness of the treatments.

The RE-LY trial calculated the sample size that was expected to provide 84% power to rule out the prespecified hazard ratio of 1.46, assuming a true event rate of 1.6% per year (presumably for both groups), a recruitment period of 2 years, and at least one year of follow-up. The sample size was subsequently increased from 15,000 to 18,000 to maintain power in case of a low event rate.4,5

5. Is the noninferiority trial as similar as possible to the trial(s) comparing the standard treatment with placebo?

Characteristics of participants, setting, reference treatment, and outcomes used in a noninferiority trial should be as close as possible to those in the trial(s) comparing the treatment with placebo. This is known as the constancy assumption, and it is key to researchers’ ability to draw a conclusion about noninferiority.

The trials used to calculate the noninferiority margin and the RE-LY trial itself involved similar populations of patients with AF, and the outcome (stroke) was similar.

6. Is a per protocol analysis reported in the results?

In randomized controlled superiority trials, the participants should be analyzed in the groups to which they were originally allocated, regardless of whether they adhered to treatment during the entire follow-up period. Such intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is important because it provides a more conservative estimate of treatment effect—taking into account that some people who are offered treatment will not accept it and others will discontinue treatment. An ITT analysis therefore tends to minimize treatment effects compared with a “per protocol” analysis, in which participants are analyzed according to the treatment they actually received and are often removed from the analysis if they discontinue or do not adhere to treatment.

In noninferiority trials, if patients in the intervention group cross over to the standard treatment group or those in the standard treatment group have poor adherence, an ITT analysis can increase the risk of wrongly claiming noninferiority.7 Therefore, a per protocol analysis should be included—and indeed may be preferable.

In RE-LY, ITT analyses were reported, and complete follow-up data were available for 99.9% of patients. However, the rates of treatment discontinuation at one year were about 15% for those on dabigatran and 10% for the warfarin group, and 21% and 17%, respectively, at 2 years.4,5 If the new treatment were truly less efficacious than the standard treatment, these moderate discontinuation rates could lead to more similar rates of stroke in the 2 groups than would be expected with higher continuation rates, biasing results towards the alternative of noninferiority. Although the original publication of trial results did not include a per protocol analysis, the RE-LY authors later reported that a per protocol analysis yielded similar results to the ITT analysis.

7. Are the overall design and execution of the trial high quality?

Because a poor quality noninferiority trial can appear to demonstrate noninferiority, looking at such studies critically is crucial. Appropriate randomization, concealed allocation, masking, and careful attention to participant flow must all be assessed.2,3

To continue with our example, the RE-LY trial was well conducted. Randomization was performed centrally via an automated telephone system and 2 doses of dabigatran were administered in a masked fashion, while warfarin was open-label. Remarkably, follow-up was achieved for 99.9% of participants over a median of 2 years, and independent adjudicators masked to treatment group assessed outcomes.4,5

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, CB 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27590; [email protected]

1. Le Henanff A, Giraudeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295:1147-1151.

2. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594-2604.

3. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-1991.

4. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatran. Am Heart J. 2009;157:805-810, 810.e1-2.

6. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry non-inferiority clinical trials. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. March 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

The traditional clinical trial, designed to test whether a new treatment is better than a placebo or another active treatment, is known as a “superiority” trial—although rarely labeled as such. In contrast, the goal of a noninferiority trial is simply to demonstrate that a new treatment is not substantially less effective than the standard therapy.

Such trials are useful when a new therapy is thought to be safer, easier to administer, or less costly than the existing treatment, but not necessarily more effective. And, because it would be unethical to randomize patients with a serious condition for which there already is an effective treatment to placebo, a noninferiority trial is another means of determining if the new treatment is effective.

Noninferiority trials have unique design features and methodology and require a different analysis than traditional superiority trials. Yet many physicians know far less about them; many investigators appear to be less than proficient, as well. A review of 116 noninferiority trials and 46 equivalence trials found that only 20% fulfilled generally accepted quality criteria.1 To improve the quality of noninferiority trials, the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Group has published a checklist for trial design and reporting standards.2,3 Based on this checklist, we came up with 7 key questions to consider when evaluating a noninferiority trial. In the pages that follow, you’ll also find an at-a-glance guide (TABLE) and a methodology review using a hypothetical case (page E7).

1. Is a noninferiority trial appropriate?

The introduction to a noninferiority trial should provide the rationale for this design and the absence of a placebo control group. Look for a review of the evidence of the efficacy of the reference treatment that placebo-controlled trials have revealed, along with the effect size. The advantages of the new treatment over the standard treatment—eg, fewer adverse effects, easier administration, or lower cost—should be discussed, as well.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY)—a prominent noninferiority trial—investigators compared the standard anticoagulant (warfarin) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at risk of stroke with a new agent, dabigatran.4 In the methods section of the abstract and the statistical analysis section of the main body, the authors clearly indicated that this was a noninferiority trial. They began by referring to the existing evidence of warfarin’s effectiveness, then detailed the qualities that make warfarin cumbersome to use, including the need for frequent laboratory monitoring. This was followed by evidence that many patients stop taking warfarin and that even for those who persist with treatment, adequate anticoagulation is difficult to maintain.

The authors went on to state that because dabigatran requires no long-term monitoring, it is easier to use. Therefore, if dabigatran could be shown to be no worse than warfarin in preventing strokes, it would be a reasonable alternative, leaving no doubt that this was an appropriate noninferiority trial.

2. Is the noninferiority margin based on clinical judgment and statistical reasoning?

The noninferiority margin should be based on clinical judgment as to how effective a new treatment must be in order to be declared not clinically inferior to the standard treatment. This can be based on several factors, including the severity of the outcome and the expected advantages of the new treatment. The margin should also take into account the size of the standard treatment’s effect vs placebo. In RELY, for example, the authors noted that the noninferiority margin was based on the desire to preserve at least 50% of the lower limit of the confidence interval (CI) of warfarin’s estimated effect; this was done using data from a previously published meta-analysis of 6 trials comparing warfarin with placebo for stroke prevention in patients with AF.4-6

3. Are the hypothesis and statistical analysis formulated correctly?

The clinical hypothesis in a noninferiority trial is that the new treatment is not worse than the standard treatment by a prespecified margin; therefore, the statistical null hypothesis to be tested is that the new treatment is worse than the reference treatment by more than that margin. Rejecting a true null hypothesis (for example, because the P value is <.05) is known as a type l error. In this setting, making a type I error would mean accepting a new treatment that is truly worse than the standard by at least the specified margin. Failure to reject a false null hypothesis is known as a type II error, which in this case would mean failing to identify a new treatment that is truly noninferior to the standard.7

In RE-LY, the authors stated that the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of a stroke with dabigatran vs warfarin had to fall below 1.46.4 (This is the same as testing the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is ≥1.46.) Thus, the hypothesis was formulated correctly.

4. Is the sample size appropriate and justified?

The sample size in a noninferiority trial should provide high power to reject the null hypothesis that the difference (or relative risk) between groups is equal to or greater than the noninferiority margin under some clinically meaningful assumption about the true difference (or absolute risk reduction) between groups. A true difference of 0 (or a relative risk of 1) is typically assumed for sample size calculation. However, assuming that the new treatment is truly slightly better or slightly worse than the standard may be clinically appropriate in some cases. This would indicate a need for a smaller or larger sample size, respectively, than that required under the usual assumption of no difference.

When the justification for the sample size in a noninferiority trial is not provided or the number of participants is based on an inappropriate approach (eg, using superiority trial calculations for a noninferiority trial), questions about the quality of the trial arise. The primary concern is whether the noninferiority margin was actually selected before the trial began, as it should have been. And if the researchers used overly optimistic assumptions about the efficacy of the new treatment relative to the standard therapy, the failure to rule out the margin could be misleading. (As with superiority trials that fail to reject the null hypothesis, post hoc power calculations should be avoided.) After the study has ended, the resulting CIs should be used to evaluate whether the study was large enough to adequately assess the relative effectiveness of the treatments.

The RE-LY trial calculated the sample size that was expected to provide 84% power to rule out the prespecified hazard ratio of 1.46, assuming a true event rate of 1.6% per year (presumably for both groups), a recruitment period of 2 years, and at least one year of follow-up. The sample size was subsequently increased from 15,000 to 18,000 to maintain power in case of a low event rate.4,5

5. Is the noninferiority trial as similar as possible to the trial(s) comparing the standard treatment with placebo?

Characteristics of participants, setting, reference treatment, and outcomes used in a noninferiority trial should be as close as possible to those in the trial(s) comparing the treatment with placebo. This is known as the constancy assumption, and it is key to researchers’ ability to draw a conclusion about noninferiority.

The trials used to calculate the noninferiority margin and the RE-LY trial itself involved similar populations of patients with AF, and the outcome (stroke) was similar.

6. Is a per protocol analysis reported in the results?

In randomized controlled superiority trials, the participants should be analyzed in the groups to which they were originally allocated, regardless of whether they adhered to treatment during the entire follow-up period. Such intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is important because it provides a more conservative estimate of treatment effect—taking into account that some people who are offered treatment will not accept it and others will discontinue treatment. An ITT analysis therefore tends to minimize treatment effects compared with a “per protocol” analysis, in which participants are analyzed according to the treatment they actually received and are often removed from the analysis if they discontinue or do not adhere to treatment.

In noninferiority trials, if patients in the intervention group cross over to the standard treatment group or those in the standard treatment group have poor adherence, an ITT analysis can increase the risk of wrongly claiming noninferiority.7 Therefore, a per protocol analysis should be included—and indeed may be preferable.

In RE-LY, ITT analyses were reported, and complete follow-up data were available for 99.9% of patients. However, the rates of treatment discontinuation at one year were about 15% for those on dabigatran and 10% for the warfarin group, and 21% and 17%, respectively, at 2 years.4,5 If the new treatment were truly less efficacious than the standard treatment, these moderate discontinuation rates could lead to more similar rates of stroke in the 2 groups than would be expected with higher continuation rates, biasing results towards the alternative of noninferiority. Although the original publication of trial results did not include a per protocol analysis, the RE-LY authors later reported that a per protocol analysis yielded similar results to the ITT analysis.

7. Are the overall design and execution of the trial high quality?

Because a poor quality noninferiority trial can appear to demonstrate noninferiority, looking at such studies critically is crucial. Appropriate randomization, concealed allocation, masking, and careful attention to participant flow must all be assessed.2,3

To continue with our example, the RE-LY trial was well conducted. Randomization was performed centrally via an automated telephone system and 2 doses of dabigatran were administered in a masked fashion, while warfarin was open-label. Remarkably, follow-up was achieved for 99.9% of participants over a median of 2 years, and independent adjudicators masked to treatment group assessed outcomes.4,5

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, CB 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27590; [email protected]

The traditional clinical trial, designed to test whether a new treatment is better than a placebo or another active treatment, is known as a “superiority” trial—although rarely labeled as such. In contrast, the goal of a noninferiority trial is simply to demonstrate that a new treatment is not substantially less effective than the standard therapy.

Such trials are useful when a new therapy is thought to be safer, easier to administer, or less costly than the existing treatment, but not necessarily more effective. And, because it would be unethical to randomize patients with a serious condition for which there already is an effective treatment to placebo, a noninferiority trial is another means of determining if the new treatment is effective.

Noninferiority trials have unique design features and methodology and require a different analysis than traditional superiority trials. Yet many physicians know far less about them; many investigators appear to be less than proficient, as well. A review of 116 noninferiority trials and 46 equivalence trials found that only 20% fulfilled generally accepted quality criteria.1 To improve the quality of noninferiority trials, the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Group has published a checklist for trial design and reporting standards.2,3 Based on this checklist, we came up with 7 key questions to consider when evaluating a noninferiority trial. In the pages that follow, you’ll also find an at-a-glance guide (TABLE) and a methodology review using a hypothetical case (page E7).

1. Is a noninferiority trial appropriate?

The introduction to a noninferiority trial should provide the rationale for this design and the absence of a placebo control group. Look for a review of the evidence of the efficacy of the reference treatment that placebo-controlled trials have revealed, along with the effect size. The advantages of the new treatment over the standard treatment—eg, fewer adverse effects, easier administration, or lower cost—should be discussed, as well.

In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY)—a prominent noninferiority trial—investigators compared the standard anticoagulant (warfarin) for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) at risk of stroke with a new agent, dabigatran.4 In the methods section of the abstract and the statistical analysis section of the main body, the authors clearly indicated that this was a noninferiority trial. They began by referring to the existing evidence of warfarin’s effectiveness, then detailed the qualities that make warfarin cumbersome to use, including the need for frequent laboratory monitoring. This was followed by evidence that many patients stop taking warfarin and that even for those who persist with treatment, adequate anticoagulation is difficult to maintain.

The authors went on to state that because dabigatran requires no long-term monitoring, it is easier to use. Therefore, if dabigatran could be shown to be no worse than warfarin in preventing strokes, it would be a reasonable alternative, leaving no doubt that this was an appropriate noninferiority trial.

2. Is the noninferiority margin based on clinical judgment and statistical reasoning?

The noninferiority margin should be based on clinical judgment as to how effective a new treatment must be in order to be declared not clinically inferior to the standard treatment. This can be based on several factors, including the severity of the outcome and the expected advantages of the new treatment. The margin should also take into account the size of the standard treatment’s effect vs placebo. In RELY, for example, the authors noted that the noninferiority margin was based on the desire to preserve at least 50% of the lower limit of the confidence interval (CI) of warfarin’s estimated effect; this was done using data from a previously published meta-analysis of 6 trials comparing warfarin with placebo for stroke prevention in patients with AF.4-6

3. Are the hypothesis and statistical analysis formulated correctly?

The clinical hypothesis in a noninferiority trial is that the new treatment is not worse than the standard treatment by a prespecified margin; therefore, the statistical null hypothesis to be tested is that the new treatment is worse than the reference treatment by more than that margin. Rejecting a true null hypothesis (for example, because the P value is <.05) is known as a type l error. In this setting, making a type I error would mean accepting a new treatment that is truly worse than the standard by at least the specified margin. Failure to reject a false null hypothesis is known as a type II error, which in this case would mean failing to identify a new treatment that is truly noninferior to the standard.7

In RE-LY, the authors stated that the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of a stroke with dabigatran vs warfarin had to fall below 1.46.4 (This is the same as testing the null hypothesis that the hazard ratio is ≥1.46.) Thus, the hypothesis was formulated correctly.

4. Is the sample size appropriate and justified?

The sample size in a noninferiority trial should provide high power to reject the null hypothesis that the difference (or relative risk) between groups is equal to or greater than the noninferiority margin under some clinically meaningful assumption about the true difference (or absolute risk reduction) between groups. A true difference of 0 (or a relative risk of 1) is typically assumed for sample size calculation. However, assuming that the new treatment is truly slightly better or slightly worse than the standard may be clinically appropriate in some cases. This would indicate a need for a smaller or larger sample size, respectively, than that required under the usual assumption of no difference.

When the justification for the sample size in a noninferiority trial is not provided or the number of participants is based on an inappropriate approach (eg, using superiority trial calculations for a noninferiority trial), questions about the quality of the trial arise. The primary concern is whether the noninferiority margin was actually selected before the trial began, as it should have been. And if the researchers used overly optimistic assumptions about the efficacy of the new treatment relative to the standard therapy, the failure to rule out the margin could be misleading. (As with superiority trials that fail to reject the null hypothesis, post hoc power calculations should be avoided.) After the study has ended, the resulting CIs should be used to evaluate whether the study was large enough to adequately assess the relative effectiveness of the treatments.

The RE-LY trial calculated the sample size that was expected to provide 84% power to rule out the prespecified hazard ratio of 1.46, assuming a true event rate of 1.6% per year (presumably for both groups), a recruitment period of 2 years, and at least one year of follow-up. The sample size was subsequently increased from 15,000 to 18,000 to maintain power in case of a low event rate.4,5

5. Is the noninferiority trial as similar as possible to the trial(s) comparing the standard treatment with placebo?

Characteristics of participants, setting, reference treatment, and outcomes used in a noninferiority trial should be as close as possible to those in the trial(s) comparing the treatment with placebo. This is known as the constancy assumption, and it is key to researchers’ ability to draw a conclusion about noninferiority.

The trials used to calculate the noninferiority margin and the RE-LY trial itself involved similar populations of patients with AF, and the outcome (stroke) was similar.

6. Is a per protocol analysis reported in the results?

In randomized controlled superiority trials, the participants should be analyzed in the groups to which they were originally allocated, regardless of whether they adhered to treatment during the entire follow-up period. Such intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis is important because it provides a more conservative estimate of treatment effect—taking into account that some people who are offered treatment will not accept it and others will discontinue treatment. An ITT analysis therefore tends to minimize treatment effects compared with a “per protocol” analysis, in which participants are analyzed according to the treatment they actually received and are often removed from the analysis if they discontinue or do not adhere to treatment.

In noninferiority trials, if patients in the intervention group cross over to the standard treatment group or those in the standard treatment group have poor adherence, an ITT analysis can increase the risk of wrongly claiming noninferiority.7 Therefore, a per protocol analysis should be included—and indeed may be preferable.

In RE-LY, ITT analyses were reported, and complete follow-up data were available for 99.9% of patients. However, the rates of treatment discontinuation at one year were about 15% for those on dabigatran and 10% for the warfarin group, and 21% and 17%, respectively, at 2 years.4,5 If the new treatment were truly less efficacious than the standard treatment, these moderate discontinuation rates could lead to more similar rates of stroke in the 2 groups than would be expected with higher continuation rates, biasing results towards the alternative of noninferiority. Although the original publication of trial results did not include a per protocol analysis, the RE-LY authors later reported that a per protocol analysis yielded similar results to the ITT analysis.

7. Are the overall design and execution of the trial high quality?

Because a poor quality noninferiority trial can appear to demonstrate noninferiority, looking at such studies critically is crucial. Appropriate randomization, concealed allocation, masking, and careful attention to participant flow must all be assessed.2,3

To continue with our example, the RE-LY trial was well conducted. Randomization was performed centrally via an automated telephone system and 2 doses of dabigatran were administered in a masked fashion, while warfarin was open-label. Remarkably, follow-up was achieved for 99.9% of participants over a median of 2 years, and independent adjudicators masked to treatment group assessed outcomes.4,5

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Mounsey, MD, UNC Chapel Hill Department of Family Medicine, 590 Manning Drive, CB 7595, Chapel Hill, NC 27590; [email protected]

1. Le Henanff A, Giraudeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295:1147-1151.

2. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594-2604.

3. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-1991.

4. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatran. Am Heart J. 2009;157:805-810, 810.e1-2.

6. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry non-inferiority clinical trials. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. March 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

1. Le Henanff A, Giraudeau B, Baron G, et al. Quality of reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295:1147-1151.

2. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594-2604.

3. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987-1991.

4. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Connolly S, Parekh A, et al. Rationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatran. Am Heart J. 2009;157:805-810, 810.e1-2.

6. Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry non-inferiority clinical trials. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. March 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

Team uses light to measure coagulation

Credit: Максим Кукушкин

Researchers have developed an optical device that requires only a few drops of blood and a few minutes to measure coagulation parameters that can guide blood transfusions and anticoagulant therapy.

The team described their device in Biomedical Optics Express.

“Currently, the most comprehensive measures of coagulation are a battery of lab tests that are expensive and can take hours to perform,” said study author Seemantini Nadkarni, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

She noted that other systems have been developed that provide clotting measurements at the point of care, but the systems can be big and expensive or have other limitations, such as requiring significant amounts of blood or only measuring clotting time.

“Our goal is to provide as much information as a lab test, but to provide it quickly and cheaply at a patient’s bedside,” Dr Nadkarni said.

To reach this goal, she and her colleagues turned to an optical technique they pioneered called laser speckle rheology. The technique involves shining a laser into a sample and monitoring the patterns of light that bounce back.

The researchers had previously used the technique to measure the mechanical properties of a range of different tissue types and found that it was extremely sensitive to the coagulation of blood.

When light hits a blood sample, blood cells and platelets scatter the light. In unclotted blood, these light-scattering particles move easily about, making the pattern of scattered light, a speckle pattern, fluctuate rapidly.

“It’s almost like looking at a starry night sky, with twinkling stars,” Dr Nadkarni said. “But as the blood starts to coagulate, blood cells and platelets come together within a fibrin network to form a clot. The motion is restricted as the sample gets stiffer, and the ‘twinkling’ of the speckle pattern is reduced significantly.”

Dr Nadkarni and her colleagues used a miniature high-speed camera to record the fluctuating speckle pattern and then correlated the intensity of changes in the pattern with 2 blood sample measurements: clotting time and fibrinogen concentration.

The team noted that physicians could use the measurements to make decisions about how much blood to give a bleeding patient and what type of blood product is needed most.

“The timely detection of clotting defects followed by the appropriate blood product transfusion is critical in managing bleeding patients,” Dr Nadkarni said. “If you transfuse too much, there could be further coagulation defects that occur, but if you don’t transfuse enough, bleeding continues.”

On the other end of the spectrum, the device could help patients on anticoagulant therapy. Having a small device that can analyze their blood in a doctor’s office or at home could reduce the cost and inconvenience of blood tests, while increasing the safety of anticoagulation treatment, Dr Nadkarni said.

At present, her team’s device is about the size of a tissue box and is connected to a computer. The researchers are working to further miniaturize the system and aim to perform clinical studies with a version smaller than a cell phone within the next year. ![]()

Credit: Максим Кукушкин

Researchers have developed an optical device that requires only a few drops of blood and a few minutes to measure coagulation parameters that can guide blood transfusions and anticoagulant therapy.

The team described their device in Biomedical Optics Express.

“Currently, the most comprehensive measures of coagulation are a battery of lab tests that are expensive and can take hours to perform,” said study author Seemantini Nadkarni, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

She noted that other systems have been developed that provide clotting measurements at the point of care, but the systems can be big and expensive or have other limitations, such as requiring significant amounts of blood or only measuring clotting time.

“Our goal is to provide as much information as a lab test, but to provide it quickly and cheaply at a patient’s bedside,” Dr Nadkarni said.

To reach this goal, she and her colleagues turned to an optical technique they pioneered called laser speckle rheology. The technique involves shining a laser into a sample and monitoring the patterns of light that bounce back.

The researchers had previously used the technique to measure the mechanical properties of a range of different tissue types and found that it was extremely sensitive to the coagulation of blood.

When light hits a blood sample, blood cells and platelets scatter the light. In unclotted blood, these light-scattering particles move easily about, making the pattern of scattered light, a speckle pattern, fluctuate rapidly.

“It’s almost like looking at a starry night sky, with twinkling stars,” Dr Nadkarni said. “But as the blood starts to coagulate, blood cells and platelets come together within a fibrin network to form a clot. The motion is restricted as the sample gets stiffer, and the ‘twinkling’ of the speckle pattern is reduced significantly.”

Dr Nadkarni and her colleagues used a miniature high-speed camera to record the fluctuating speckle pattern and then correlated the intensity of changes in the pattern with 2 blood sample measurements: clotting time and fibrinogen concentration.

The team noted that physicians could use the measurements to make decisions about how much blood to give a bleeding patient and what type of blood product is needed most.

“The timely detection of clotting defects followed by the appropriate blood product transfusion is critical in managing bleeding patients,” Dr Nadkarni said. “If you transfuse too much, there could be further coagulation defects that occur, but if you don’t transfuse enough, bleeding continues.”

On the other end of the spectrum, the device could help patients on anticoagulant therapy. Having a small device that can analyze their blood in a doctor’s office or at home could reduce the cost and inconvenience of blood tests, while increasing the safety of anticoagulation treatment, Dr Nadkarni said.

At present, her team’s device is about the size of a tissue box and is connected to a computer. The researchers are working to further miniaturize the system and aim to perform clinical studies with a version smaller than a cell phone within the next year. ![]()

Credit: Максим Кукушкин

Researchers have developed an optical device that requires only a few drops of blood and a few minutes to measure coagulation parameters that can guide blood transfusions and anticoagulant therapy.

The team described their device in Biomedical Optics Express.

“Currently, the most comprehensive measures of coagulation are a battery of lab tests that are expensive and can take hours to perform,” said study author Seemantini Nadkarni, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

She noted that other systems have been developed that provide clotting measurements at the point of care, but the systems can be big and expensive or have other limitations, such as requiring significant amounts of blood or only measuring clotting time.

“Our goal is to provide as much information as a lab test, but to provide it quickly and cheaply at a patient’s bedside,” Dr Nadkarni said.

To reach this goal, she and her colleagues turned to an optical technique they pioneered called laser speckle rheology. The technique involves shining a laser into a sample and monitoring the patterns of light that bounce back.

The researchers had previously used the technique to measure the mechanical properties of a range of different tissue types and found that it was extremely sensitive to the coagulation of blood.

When light hits a blood sample, blood cells and platelets scatter the light. In unclotted blood, these light-scattering particles move easily about, making the pattern of scattered light, a speckle pattern, fluctuate rapidly.

“It’s almost like looking at a starry night sky, with twinkling stars,” Dr Nadkarni said. “But as the blood starts to coagulate, blood cells and platelets come together within a fibrin network to form a clot. The motion is restricted as the sample gets stiffer, and the ‘twinkling’ of the speckle pattern is reduced significantly.”

Dr Nadkarni and her colleagues used a miniature high-speed camera to record the fluctuating speckle pattern and then correlated the intensity of changes in the pattern with 2 blood sample measurements: clotting time and fibrinogen concentration.

The team noted that physicians could use the measurements to make decisions about how much blood to give a bleeding patient and what type of blood product is needed most.

“The timely detection of clotting defects followed by the appropriate blood product transfusion is critical in managing bleeding patients,” Dr Nadkarni said. “If you transfuse too much, there could be further coagulation defects that occur, but if you don’t transfuse enough, bleeding continues.”

On the other end of the spectrum, the device could help patients on anticoagulant therapy. Having a small device that can analyze their blood in a doctor’s office or at home could reduce the cost and inconvenience of blood tests, while increasing the safety of anticoagulation treatment, Dr Nadkarni said.

At present, her team’s device is about the size of a tissue box and is connected to a computer. The researchers are working to further miniaturize the system and aim to perform clinical studies with a version smaller than a cell phone within the next year. ![]()

Mutation responsible for insecticide resistance

spray insecticide

Credit: Morgana Wingard

A single genetic mutation can cause resistance to the main insecticides used to combat malaria, according to a study published in Genome Biology.

Researchers identified a mutation in the gene GSTe2 that allows mosquitoes to break down the insecticide DDT into non-toxic substances.

The mutation also makes mosquitoes resistant to pyrethroids, an insecticide class used in mosquito nets.

“We found a population of mosquitoes fully resistant to DDT but also to pyrethroids,” said study author Charles Wondji, PhD, of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“So we wanted to elucidate the molecular basis of that resistance in the population and design a field-applicable diagnostic assay for its monitoring.”

To that end, the researchers did a genome-wide comparison on mosquitoes that were fully susceptible to insecticides and Anopheles funestus mosquitoes from the Republic of Benin in Africa, which were resistant to DDT and the pyrethroid permethrin.

The team found the GSTe2 gene was upregulated in the resistant mosquitoes. And a single mutation (L119F) changed a non-resistant version of the gene to an insecticide-resistant version.

The researchers then designed a DNA-based diagnostic test for this metabolic resistance and confirmed that this mutation was found in mosquitoes from other areas of the world with DDT resistance, but it was completely absent in regions without resistance.

X-ray crystallography of the protein coded by the gene illustrated exactly how the mutation conferred resistance—by opening up the active site where DDT molecules bind to the protein so that more can be broken down. In other words, the mosquito can survive by breaking down the poison into non-toxic substances.

The researchers also introduced the gene into Drosophila melanogaster and found the flies became resistant to DDT and pyrethroids, whereas control flies did not. The team said this confirms that a single mutation is enough to make insects resistant to both DDT and pyrethroids.

“For the first time, we have been able to identify a molecular marker for metabolic resistance in a mosquito population and to design a DNA-based diagnostic assay,” Dr Wondji said.

“Such tools will allow control programs to detect and track resistance at an early stage in the field, which is an essential requirement to successfully tackle the growing problem of insecticide resistance in vector control. This significant progress opens the door for us to do this with other forms of resistance as well and in other vector species.” ![]()

spray insecticide

Credit: Morgana Wingard

A single genetic mutation can cause resistance to the main insecticides used to combat malaria, according to a study published in Genome Biology.

Researchers identified a mutation in the gene GSTe2 that allows mosquitoes to break down the insecticide DDT into non-toxic substances.

The mutation also makes mosquitoes resistant to pyrethroids, an insecticide class used in mosquito nets.

“We found a population of mosquitoes fully resistant to DDT but also to pyrethroids,” said study author Charles Wondji, PhD, of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“So we wanted to elucidate the molecular basis of that resistance in the population and design a field-applicable diagnostic assay for its monitoring.”

To that end, the researchers did a genome-wide comparison on mosquitoes that were fully susceptible to insecticides and Anopheles funestus mosquitoes from the Republic of Benin in Africa, which were resistant to DDT and the pyrethroid permethrin.

The team found the GSTe2 gene was upregulated in the resistant mosquitoes. And a single mutation (L119F) changed a non-resistant version of the gene to an insecticide-resistant version.

The researchers then designed a DNA-based diagnostic test for this metabolic resistance and confirmed that this mutation was found in mosquitoes from other areas of the world with DDT resistance, but it was completely absent in regions without resistance.

X-ray crystallography of the protein coded by the gene illustrated exactly how the mutation conferred resistance—by opening up the active site where DDT molecules bind to the protein so that more can be broken down. In other words, the mosquito can survive by breaking down the poison into non-toxic substances.

The researchers also introduced the gene into Drosophila melanogaster and found the flies became resistant to DDT and pyrethroids, whereas control flies did not. The team said this confirms that a single mutation is enough to make insects resistant to both DDT and pyrethroids.

“For the first time, we have been able to identify a molecular marker for metabolic resistance in a mosquito population and to design a DNA-based diagnostic assay,” Dr Wondji said.

“Such tools will allow control programs to detect and track resistance at an early stage in the field, which is an essential requirement to successfully tackle the growing problem of insecticide resistance in vector control. This significant progress opens the door for us to do this with other forms of resistance as well and in other vector species.” ![]()

spray insecticide

Credit: Morgana Wingard

A single genetic mutation can cause resistance to the main insecticides used to combat malaria, according to a study published in Genome Biology.

Researchers identified a mutation in the gene GSTe2 that allows mosquitoes to break down the insecticide DDT into non-toxic substances.

The mutation also makes mosquitoes resistant to pyrethroids, an insecticide class used in mosquito nets.

“We found a population of mosquitoes fully resistant to DDT but also to pyrethroids,” said study author Charles Wondji, PhD, of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“So we wanted to elucidate the molecular basis of that resistance in the population and design a field-applicable diagnostic assay for its monitoring.”

To that end, the researchers did a genome-wide comparison on mosquitoes that were fully susceptible to insecticides and Anopheles funestus mosquitoes from the Republic of Benin in Africa, which were resistant to DDT and the pyrethroid permethrin.

The team found the GSTe2 gene was upregulated in the resistant mosquitoes. And a single mutation (L119F) changed a non-resistant version of the gene to an insecticide-resistant version.

The researchers then designed a DNA-based diagnostic test for this metabolic resistance and confirmed that this mutation was found in mosquitoes from other areas of the world with DDT resistance, but it was completely absent in regions without resistance.

X-ray crystallography of the protein coded by the gene illustrated exactly how the mutation conferred resistance—by opening up the active site where DDT molecules bind to the protein so that more can be broken down. In other words, the mosquito can survive by breaking down the poison into non-toxic substances.

The researchers also introduced the gene into Drosophila melanogaster and found the flies became resistant to DDT and pyrethroids, whereas control flies did not. The team said this confirms that a single mutation is enough to make insects resistant to both DDT and pyrethroids.

“For the first time, we have been able to identify a molecular marker for metabolic resistance in a mosquito population and to design a DNA-based diagnostic assay,” Dr Wondji said.

“Such tools will allow control programs to detect and track resistance at an early stage in the field, which is an essential requirement to successfully tackle the growing problem of insecticide resistance in vector control. This significant progress opens the door for us to do this with other forms of resistance as well and in other vector species.” ![]()

Actionability of TPAD Results

Effective communication between inpatient and primary care physicians (PCPs) is essential for safe, high‐quality transitions. Unfortunately, PCPs are often not meaningfully engaged in this process; communication is frequently challenging or nonexistent.[1, 2] Instead, information is suboptimally conveyed via lengthy, disorganized discharge summaries.[3] Consequently, timely knowledge is not transferred to PCPs, who instead must seek out and identify actionable information themselves. These deficiencies can lead to misinterpretation of information and patient harm.[4]

An important component of ideal transitions[5] is timely communication of results of tests pending at discharge (TPADs). TPADs are variably documented in discharge summaries, and physician awareness about them is strikingly poor.[3, 6, 7] Communication about TPADs should convey rationales for ordering tests and necessary actions to take in response to finalized results. Most often, this knowledge resides with the inpatient team.

Health information technology (HIT) is an effective strategy for improving test‐result management. We implemented an automated system that notifies inpatient attendings and PCPs of TPAD results via email and demonstrated increased awareness by these physicians at the time of required action.[8, 9] Nevertheless, without timely knowledge transfer, attendings and PCPs may have differing opinions regarding which TPAD results require action. We conducted a secondary analysis of survey respondents from our original clustered randomized controlled trial to measure the degree of agreement between inpatient and ambulatory physicians regarding actionability of TPAD results.

METHODS

The methods of our original study are described elsewhere.[9] In that study, the attending and PCP of each patient were independently surveyed (via email and then by fax if the electronic survey was not completed) to determine their awareness of finalized TPAD results, and to identify actionable results and the types of actions taken (or that would need to be taken). Discharge summaries were available in our electronic medical record (EMR) within 24 hours of discharge. Network physicians (affiliated with Partners HealthCare, Inc.) had access to all components of the EMR, including the discharge summary and test results. Non‐network PCPs were faxed discharge summaries within 48 hours of discharge per institutional policies. For this study, we identified all patients for whom the attending and PCP completed the survey and answered questions about TPAD actionability. We then compared the identified TPADs listed by the attending and PCP in that survey.

RESULTS

We enrolled 441 patients in our original study. We sent 441 surveys to 117 attendings and 353 surveys to 273 PCPs. Eighty‐eight patients did not have an identified PCP. We received 275 responses from 83 attendings (62% response rate), and 152 responses from 112 PCPs (43% response rate). Patient and physician characteristics are reported elsewhere.[9]

For this analysis, we identified the 98 patients (aged 6018 years, 44 male, 52 Caucasian, 46 non‐Caucasian, 85 network, 13 non‐network) cared for by 46 attendings (aged 4411 years, 33 male, 22 hospitalists, 24 nonhospitalists) and 79 PCPs (aged 4512.5, 33 male, 66 network, 13 non‐network) for whom we received completed surveys from both physicians. For 59 patients, both thought none of the TPAD results were actionable. For 12 patients, both thought at least 1 was actionable, and they identified the same actionable TPAD result for all 12. Overall, attendings and PCPs agreed on actionability in 72.5% (71/98) (Kappa 0.29, 95% confidence interval: 0.09‐0.50). Table 1 shows the type of action taken by responsible providers. There were 9 patients (9%) for whom the attending alone thought at least 1 TPAD result was actionable; of these, subsequent attending‐initiated communication occurred in 77.8% (7/9). There were 18 patients (18%) for whom the PCP alone thought at least 1 TPAD result was actionable; of these, subsequent PCP‐initiated communication occurred in 77.8% (14/18). Table 2 shows concordance of actionable TPAD by type. In instances of disagreement, the attending frequently reported microbiology TPADs (eg, culture data, viral serologies) as actionable, whereas the PCP reported all TPAD types (eg, culture data, colon biopsy, vitamin D, magnetic resonance imaging) as actionable.

| Inpatient Attending‐Initiated Action(s)a | PCP‐Initiated Action(s)a | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Patient was notifiedb | 11.1% (1/9) | 66.7% (12/18) |

| Subspecialist was contacted | 33.3% (3/9) | 16.7% (3/18) |

| PCP or inpatient team contacted | 33.3% (3/9) | 16.7% (3/18) |

| Further testing/modified treatment | 11.1% (1/9) | 33.3% (6/18) |

| Referred to ambulatory visit/emergency room | 0% (0/9) | 11.1% (2/18) |

| Documentation | 11.1% (1/9) | 16.7% (3/18) |

| Type of TPAD | Attending and PCP Agreed on Identity of Actionable TPADa | Attending and PCP Disagreed on Identity of Actionable TPADa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPAD Identified | No TPAD Identified, n=59 | TPAD Identified by Attending Only | TPAD Identified by PCP Only | |

| ||||

| Microbiologyb | 25% (3/12) | N/A | 56% (5/9) | 17% (3/18) |

| Pathologyc | 17% (2/12) | N/A | 0% (0/9) | 17% (3/18) |

| Chemistry and hematologyd | 58% (7/12) | N/A | 11% (1/9) | 22% (4/18) |

| Radiologye | 0% (0/12) | N/A | 11% (1/9) | 39% (5/18) |

| Unclassified (left blank) | 0% (0/12) | N/A | 22% (1/9) | 17% (3/18) |

DISCUSSION

We found fair agreement between attendings and PCPs regarding actionability of TPAD results. In 27 patients (27.5%), either the attending or PCP considered TPAD results actionable when the other did not. Possible explanations for this include different thresholds for taking action (eg, inpatient physicians may view vitamin D levels as acceptable within broader ranges than PCPs, and PCPs may view negative results as actionable if they need to contact the patient whereas attendings may not), varying clinical context (eg, rationale for why microbiology culture data is actionable), and varying practices for escalating care (eg, referring patients back to the hospital).

Our study was limited by small sample size and low PCP response rate. Nonetheless, the findings suggest that poor concordance between inpatient and ambulatory physicians will persist without tools that promote more effective communication. Greater awareness alone may be insufficient to mitigate consequences of missed TPAD results if physicians are not on the same page regarding which results require action.

To better engage PCPs, healthcare systems require HIT infrastructure that facilitates seamless care team communication across care settings.[2] When optimally configured, HIT can facilitate greater PCP involvement in postdischarge communication. For example, our system promoted subsequent postdischarge communication in 78% of initial discordance in TPAD actionability; however, most of it was not between the attending and the PCP. Thus, improvements could be made to facilitate more effective communication among key inpatient and ambulatory providers. Furthermore, when configured to facilitate conversation among these providers regarding the discharge care plan throughout a patient's entire hospital course, HIT can promote effective knowledge transfer by virtue of adding clinical context to test ordering and follow‐up. Additional work is needed to understand whether such communication clarifies contingencies and facilitates appropriate postdischarge action. Nevertheless, current electronic solutions (eg, passive placement into results in‐baskets) will likely be ineffective because they do not reliably improve awareness and active communication about context, rationale, interpretation, suggested action, or transfer of responsibility.

In summary, discrepancies in TPAD actionability by inpatient and ambulatory providers still exist, even when awareness of TPAD results is improved by HIT. By fostering more effective communication among key care‐team members across care settings, HIT could mitigate the consequences of suboptimal care transitions. With regard to TPAD results, this may favorably impact unnecessary testing, diagnostic and therapeutic delays, and medical errors.

Disclosures: This article is based on research funded through AHRQ grant #R21HS018229; the authors have no other disclosures or conflicts or interest.

- , , , et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:385–391.

- . A primary care physician's ideal transitions of care—where's the evidence? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):472–477.

- , , , et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167.

- , , , . Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2012;8(2):102–109.

- , , , et al. Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow‐up providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1002–1006.

- , , , et al. Patient safety concerns rising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121–128.

- , , , et al. Design and implementation of an automated email notification system for results of tests pending at discharge. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(4):523–528.

- , , , et al. Impact of an automated email notification system for results of rest pending at discharge: a cluster‐randomized controlled trial [published online ahead of print October 23, 2013]. J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi:10.1136/amiajnl‐2013‐002030.

Effective communication between inpatient and primary care physicians (PCPs) is essential for safe, high‐quality transitions. Unfortunately, PCPs are often not meaningfully engaged in this process; communication is frequently challenging or nonexistent.[1, 2] Instead, information is suboptimally conveyed via lengthy, disorganized discharge summaries.[3] Consequently, timely knowledge is not transferred to PCPs, who instead must seek out and identify actionable information themselves. These deficiencies can lead to misinterpretation of information and patient harm.[4]

An important component of ideal transitions[5] is timely communication of results of tests pending at discharge (TPADs). TPADs are variably documented in discharge summaries, and physician awareness about them is strikingly poor.[3, 6, 7] Communication about TPADs should convey rationales for ordering tests and necessary actions to take in response to finalized results. Most often, this knowledge resides with the inpatient team.

Health information technology (HIT) is an effective strategy for improving test‐result management. We implemented an automated system that notifies inpatient attendings and PCPs of TPAD results via email and demonstrated increased awareness by these physicians at the time of required action.[8, 9] Nevertheless, without timely knowledge transfer, attendings and PCPs may have differing opinions regarding which TPAD results require action. We conducted a secondary analysis of survey respondents from our original clustered randomized controlled trial to measure the degree of agreement between inpatient and ambulatory physicians regarding actionability of TPAD results.

METHODS

The methods of our original study are described elsewhere.[9] In that study, the attending and PCP of each patient were independently surveyed (via email and then by fax if the electronic survey was not completed) to determine their awareness of finalized TPAD results, and to identify actionable results and the types of actions taken (or that would need to be taken). Discharge summaries were available in our electronic medical record (EMR) within 24 hours of discharge. Network physicians (affiliated with Partners HealthCare, Inc.) had access to all components of the EMR, including the discharge summary and test results. Non‐network PCPs were faxed discharge summaries within 48 hours of discharge per institutional policies. For this study, we identified all patients for whom the attending and PCP completed the survey and answered questions about TPAD actionability. We then compared the identified TPADs listed by the attending and PCP in that survey.

RESULTS

We enrolled 441 patients in our original study. We sent 441 surveys to 117 attendings and 353 surveys to 273 PCPs. Eighty‐eight patients did not have an identified PCP. We received 275 responses from 83 attendings (62% response rate), and 152 responses from 112 PCPs (43% response rate). Patient and physician characteristics are reported elsewhere.[9]

For this analysis, we identified the 98 patients (aged 6018 years, 44 male, 52 Caucasian, 46 non‐Caucasian, 85 network, 13 non‐network) cared for by 46 attendings (aged 4411 years, 33 male, 22 hospitalists, 24 nonhospitalists) and 79 PCPs (aged 4512.5, 33 male, 66 network, 13 non‐network) for whom we received completed surveys from both physicians. For 59 patients, both thought none of the TPAD results were actionable. For 12 patients, both thought at least 1 was actionable, and they identified the same actionable TPAD result for all 12. Overall, attendings and PCPs agreed on actionability in 72.5% (71/98) (Kappa 0.29, 95% confidence interval: 0.09‐0.50). Table 1 shows the type of action taken by responsible providers. There were 9 patients (9%) for whom the attending alone thought at least 1 TPAD result was actionable; of these, subsequent attending‐initiated communication occurred in 77.8% (7/9). There were 18 patients (18%) for whom the PCP alone thought at least 1 TPAD result was actionable; of these, subsequent PCP‐initiated communication occurred in 77.8% (14/18). Table 2 shows concordance of actionable TPAD by type. In instances of disagreement, the attending frequently reported microbiology TPADs (eg, culture data, viral serologies) as actionable, whereas the PCP reported all TPAD types (eg, culture data, colon biopsy, vitamin D, magnetic resonance imaging) as actionable.

| Inpatient Attending‐Initiated Action(s)a | PCP‐Initiated Action(s)a | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Patient was notifiedb | 11.1% (1/9) | 66.7% (12/18) |

| Subspecialist was contacted | 33.3% (3/9) | 16.7% (3/18) |

| PCP or inpatient team contacted | 33.3% (3/9) | 16.7% (3/18) |

| Further testing/modified treatment | 11.1% (1/9) | 33.3% (6/18) |

| Referred to ambulatory visit/emergency room | 0% (0/9) | 11.1% (2/18) |

| Documentation | 11.1% (1/9) | 16.7% (3/18) |

| Type of TPAD | Attending and PCP Agreed on Identity of Actionable TPADa | Attending and PCP Disagreed on Identity of Actionable TPADa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPAD Identified | No TPAD Identified, n=59 | TPAD Identified by Attending Only | TPAD Identified by PCP Only | |

| ||||

| Microbiologyb | 25% (3/12) | N/A | 56% (5/9) | 17% (3/18) |

| Pathologyc | 17% (2/12) | N/A | 0% (0/9) | 17% (3/18) |

| Chemistry and hematologyd | 58% (7/12) | N/A | 11% (1/9) | 22% (4/18) |