User login

In critically ill patients, dalteparin is more cost-effective for VTE prevention

The low molecular weight heparin dalteparin and unfractionated heparin are associated with similar rates of thrombosis and major bleeding, but dalteparin is associated with lower rates of pulmonary embolus and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, based on results from a prospective randomized study.

Given for prevention of venous thromboembolism, median hospital costs per patient were $39,508 for dalteparin users and $40,805 for unfractionated heparin users. Dalteparin remained the least costly strategy until its acquisition costs rose from $8 per dose to $179, as reported online 1 November in the Journal of the American Medical Association [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15101].

The economic analysis—conducted alongside the multi-centre, randomized PROTECT trial in 2344 critically-ill medical-surgical patients— showed no matter how low the acquisition cost of unfractionated heparin, there was no threshold that favored that form of prophylaxis, according to data also presented at the Critical Care Canada Forum.

“From a health care payer perspective, VTE prophylaxis with the LMWH [low molecular weight heparin] dalteparin in critically ill medical-surgical patients was more effective and had similar or lower costs than the use of UFH [unfractionated heparin],” wrote Dr. Robert A. Fowler, from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, and colleagues.The E-PROTECT study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Ontario, Canada), the University of Toronto, and the Canadian Intensive Care Foundation. PROTECT was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Canada), and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anesthetists Research Foundation. Some authors reported fees, support, and consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry.

The low molecular weight heparin dalteparin and unfractionated heparin are associated with similar rates of thrombosis and major bleeding, but dalteparin is associated with lower rates of pulmonary embolus and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, based on results from a prospective randomized study.

Given for prevention of venous thromboembolism, median hospital costs per patient were $39,508 for dalteparin users and $40,805 for unfractionated heparin users. Dalteparin remained the least costly strategy until its acquisition costs rose from $8 per dose to $179, as reported online 1 November in the Journal of the American Medical Association [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15101].

The economic analysis—conducted alongside the multi-centre, randomized PROTECT trial in 2344 critically-ill medical-surgical patients— showed no matter how low the acquisition cost of unfractionated heparin, there was no threshold that favored that form of prophylaxis, according to data also presented at the Critical Care Canada Forum.

“From a health care payer perspective, VTE prophylaxis with the LMWH [low molecular weight heparin] dalteparin in critically ill medical-surgical patients was more effective and had similar or lower costs than the use of UFH [unfractionated heparin],” wrote Dr. Robert A. Fowler, from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, and colleagues.The E-PROTECT study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Ontario, Canada), the University of Toronto, and the Canadian Intensive Care Foundation. PROTECT was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Canada), and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anesthetists Research Foundation. Some authors reported fees, support, and consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry.

The low molecular weight heparin dalteparin and unfractionated heparin are associated with similar rates of thrombosis and major bleeding, but dalteparin is associated with lower rates of pulmonary embolus and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, based on results from a prospective randomized study.

Given for prevention of venous thromboembolism, median hospital costs per patient were $39,508 for dalteparin users and $40,805 for unfractionated heparin users. Dalteparin remained the least costly strategy until its acquisition costs rose from $8 per dose to $179, as reported online 1 November in the Journal of the American Medical Association [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15101].

The economic analysis—conducted alongside the multi-centre, randomized PROTECT trial in 2344 critically-ill medical-surgical patients— showed no matter how low the acquisition cost of unfractionated heparin, there was no threshold that favored that form of prophylaxis, according to data also presented at the Critical Care Canada Forum.

“From a health care payer perspective, VTE prophylaxis with the LMWH [low molecular weight heparin] dalteparin in critically ill medical-surgical patients was more effective and had similar or lower costs than the use of UFH [unfractionated heparin],” wrote Dr. Robert A. Fowler, from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, and colleagues.The E-PROTECT study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Ontario, Canada), the University of Toronto, and the Canadian Intensive Care Foundation. PROTECT was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Canada), and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anesthetists Research Foundation. Some authors reported fees, support, and consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Dalteparin is more cost-effective than unfractionated heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism.

Major finding: Dalteparin is as effective as unfractionated heparin in reducing thrombosis, for the same cost, but with less pulmonary embolus and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Data source: Economic analysis of a prospective randomized controlled trial of low molecular weight heparin dalteparin versus unfractionated heparin in 2344 critically-ill medical-surgical patients

Disclosures: The E-PROTECT study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Ontario, Canada), the University of Toronto, and the Canadian Intensive Care Foundation. PROTECT was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation (Canada), and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anesthetists Research Foundation. Some authors reported fees, support, and consultancies to the pharmaceutical industry.

How to avoid diagnostic errors

As a generalist specialty, family medicine faces more diagnostic challenges than any other specialty because we see so many undifferentiated problems. However, only 2 family physicians attended this meeting: I was one, because of my research interests in proper use of lab testing, and John Ely, MD, from the University of Iowa, was the other. He has been researching diagnostic errors for most of his career. Dr. Ely has been testing an idea borrowed from aviation: using a diagnostic checklist. He developed a packet of note cards that lists the top 10 to 20 diagnoses for complaints commonly seen in family medicine, such as headache and abdominal pain. Before the patient leaves the exam room, he pulls out the appropriate checklist and goes through it out loud, just like a pilot before takeoff. He says for most patients, this process is pretty quick and it reassures both them and him that he has not missed an important diagnosis. (You can download Dr. Ely’s checklists from http://www.improvediagnosis.org/resource/resmgr/docs/diffdx.doc.)

How are the rest of us avoiding diagnostic errors? Some day IBM’s Watson or another diagnostic software program embedded in the electronic health record will guide us to the right diagnosis. In the meantime, I have developed a list of 7 low-tech ways to arrive at the correct diagnosis (and to rapidly correct a diagnostic error, should one occur):

2. Find out what dreaded diagnosis the patient believes he or she has so you can rule it in or out.

3. Don’t forget the pertinent past history. It makes a big difference if this is the patient’s first bad headache or the latest in a string of them.

4. Don’t skip the physical exam; even a negative exam, if documented properly, may keep you out of court.

5. Negotiate the diagnosis and treatment plan with the patient. This often brings out new information and new concerns.

6. Follow up, follow up, follow up, and do so in a timely manner.

7. Quickly reconsider your diagnosis and/or get a consultation if things are not going as expected.

As a generalist specialty, family medicine faces more diagnostic challenges than any other specialty because we see so many undifferentiated problems. However, only 2 family physicians attended this meeting: I was one, because of my research interests in proper use of lab testing, and John Ely, MD, from the University of Iowa, was the other. He has been researching diagnostic errors for most of his career. Dr. Ely has been testing an idea borrowed from aviation: using a diagnostic checklist. He developed a packet of note cards that lists the top 10 to 20 diagnoses for complaints commonly seen in family medicine, such as headache and abdominal pain. Before the patient leaves the exam room, he pulls out the appropriate checklist and goes through it out loud, just like a pilot before takeoff. He says for most patients, this process is pretty quick and it reassures both them and him that he has not missed an important diagnosis. (You can download Dr. Ely’s checklists from http://www.improvediagnosis.org/resource/resmgr/docs/diffdx.doc.)

How are the rest of us avoiding diagnostic errors? Some day IBM’s Watson or another diagnostic software program embedded in the electronic health record will guide us to the right diagnosis. In the meantime, I have developed a list of 7 low-tech ways to arrive at the correct diagnosis (and to rapidly correct a diagnostic error, should one occur):

2. Find out what dreaded diagnosis the patient believes he or she has so you can rule it in or out.

3. Don’t forget the pertinent past history. It makes a big difference if this is the patient’s first bad headache or the latest in a string of them.

4. Don’t skip the physical exam; even a negative exam, if documented properly, may keep you out of court.

5. Negotiate the diagnosis and treatment plan with the patient. This often brings out new information and new concerns.

6. Follow up, follow up, follow up, and do so in a timely manner.

7. Quickly reconsider your diagnosis and/or get a consultation if things are not going as expected.

As a generalist specialty, family medicine faces more diagnostic challenges than any other specialty because we see so many undifferentiated problems. However, only 2 family physicians attended this meeting: I was one, because of my research interests in proper use of lab testing, and John Ely, MD, from the University of Iowa, was the other. He has been researching diagnostic errors for most of his career. Dr. Ely has been testing an idea borrowed from aviation: using a diagnostic checklist. He developed a packet of note cards that lists the top 10 to 20 diagnoses for complaints commonly seen in family medicine, such as headache and abdominal pain. Before the patient leaves the exam room, he pulls out the appropriate checklist and goes through it out loud, just like a pilot before takeoff. He says for most patients, this process is pretty quick and it reassures both them and him that he has not missed an important diagnosis. (You can download Dr. Ely’s checklists from http://www.improvediagnosis.org/resource/resmgr/docs/diffdx.doc.)

How are the rest of us avoiding diagnostic errors? Some day IBM’s Watson or another diagnostic software program embedded in the electronic health record will guide us to the right diagnosis. In the meantime, I have developed a list of 7 low-tech ways to arrive at the correct diagnosis (and to rapidly correct a diagnostic error, should one occur):

2. Find out what dreaded diagnosis the patient believes he or she has so you can rule it in or out.

3. Don’t forget the pertinent past history. It makes a big difference if this is the patient’s first bad headache or the latest in a string of them.

4. Don’t skip the physical exam; even a negative exam, if documented properly, may keep you out of court.

5. Negotiate the diagnosis and treatment plan with the patient. This often brings out new information and new concerns.

6. Follow up, follow up, follow up, and do so in a timely manner.

7. Quickly reconsider your diagnosis and/or get a consultation if things are not going as expected.

4 pregnant women with an unusual finding at delivery

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 32-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented for induction at 41 weeks and 2 days of gestation. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. A compound presentation and a prolonged second stage of labor made vacuum assistance necessary. The infant had both a true umbilical cord knot (TUCK) (FIGURE 1A) and double nuchal cord.

CASE 2 › A 46-year-old G3P0 at 38 weeks of gestation by in vitro fertilization underwent an uncomplicated primary low transverse cesarean (C-section) delivery of dichorionic/diamniotic twins. The C-section had been necessary because baby A had been in the breech position. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. Baby A had a velamentous cord insertion, and baby B had a succenturiate lobe and a TUCK.

CASE 3 › A 23-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course chose to have a repeat C-section and delivered at 41 weeks in active labor. Fetal heart monitoring showed no abnormalities. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK was noted at time of delivery.

CASE 4 › A 30-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented in active labor at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. At 7 cm cervical dilation, monitoring showed repeated deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations. The patient underwent an uncomplicated primary C-section. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK (FIGURE 1B) and double nuchal cord were found at time of delivery.

DISCUSSION

TUCKs are thought to occur when a fetus passes through a loop in the umbilical cord. They occur in <2% of term deliveries.1,2 TUCKs differ from false knots. False knots are exaggerated loops of cord vasculature.

Risk factors that have been independently associated with TUCK include advanced maternal age (AMA; >35 years), multiparity, diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polyhydramnios, and previous spontaneous abortion.1-3 In one study, 72% of women with a TUCK were multiparous.3 Hershkovitz et al2 suggested that laxity of uterine and abdominal musculature in multiparous patients may contribute to increased room for TUCK formation.

The adjusted odds ratio of having a TUCK is 2.53 in women with diabetes mellitus.3 Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased fetal movements, thereby increasing the risk of TUCK development.2 Polyhydramnios is often found in patients with diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes.3 The incidence is higher in monoamniotic twins.4

Being a male and having a longer umbilical cord may also increase the risk of TUCK. On average, male infants have longer cords than females, which may predispose them to TUCKs.3 Räisänen et al3 found that the mean cord length in TUCK infants was 16.9 cm longer than in infants without a TUCK.

Of our 4 patients, one was of AMA, 2 were multiparous, and 3 of the 4 infants who developed TUCK were male.

TUCK is usually diagnosed at delivery

Most cases of TUCK are found incidentally at the time of delivery. Antenatal diagnosis is difficult, because loops of cord lying together are easily mistaken for knots on ultrasound.5 Sepulveda et al6 evaluated the use of 3D power Doppler in 8 cases of suspected TUCK; only 63% were confirmed at delivery. Some researchers have found improved detection of TUCK with color Doppler and 4D ultrasound, which have demonstrated a “hanging noose sign” (a transverse section of umbilical cord surrounded by a loop of cord) as well as views of the cord under pressure.7-10

Outcomes associated with TUCK vary greatly. Neonates affected by TUCK have a 4% to 10% increased risk of stillbirth, usually attributed to knot tightening.2,4,11,12

In addition, there is an increased incidence of fetal heart rate abnormalities during labor.1,3,12,13

There is no increase in the incidence of assisted vaginal or C-section delivery.12 And as for whether TUCK affects an infant’s size or weight, one study found TUCK infants had a 3.2-fold higher risk of measuring small for gestational age, potentially due to chronic umbilical cord compromise; however, mean birth weight between study and control groups did not differ significantly.3

Outcomes for our patients and their infants. All 4 cases had good outcomes (TABLE). The umbilical cord knot produced no detectable fetal compromise in cases 1 through 3. In Case 4, electronic fetal monitoring showed repeated variable fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably associated with cord compression.

THE TAKEAWAY

Pregnant women who may be at risk for experiencing a TUCK include those who are older than age 35, multiparous, carrying a boy, or have diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, or polyhydramnios. While it is good to be aware of these risk factors, there are no recommended changes in management based on risk or ultrasound findings unless there is additional concern for fetal compromise.

Antenatal diagnosis of TUCK is challenging, but Doppler ultrasound may be able to identify the condition. Most cases of TUCK are noted on delivery, and outcomes are generally positive, although infants in whom the TUCK tightens may have an increased risk of heart rate abnormalities or stillbirth.

1. Joura EA, Zeisler H, Sator MO. Epidemiology and clinical value of true umbilical cord knots [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:232-235.

2. Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, et al. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:36-39.

3. Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, et al. True umbilical cord knot and obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122: 18-21.

4. Maher JT, Conti JA. A comparison of umbilical cord blood gas values between newborns with and without true knots. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:863-866.

5. Clerici G, Koutras I, Luzietti R, et al. Multiple true umbilical knots: a silent risk for intrauterine growth restriction with anomalous hemodynamic pattern. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:440-443.

6. Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, et al. True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:106-108.

7. Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1215-1220.

8. Rodriguez N, Angarita AM, Casasbuenas A, et al. Three-dimensional high-definition flow imaging in prenatal diagnosis of a true umbilical cord knot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:245-246.

9. Scioscia M, Fornalè M, Bruni F, et al. Four-dimensional and Doppler sonography in the diagnosis and surveillance of a true cord knot. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39: 157-159.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Zigalo A, et al. Power Doppler and 3-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of multiple separate true knots of the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24: 1321-1323.

11. Sørnes T. Umbilical cord knots. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:157-159.

12. Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:127-132.

13. Szczepanik ME, Wittich AC. True knot of the umbilical cord: a report of 13 cases. Mil Med. 2007;172:892-894.

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 32-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented for induction at 41 weeks and 2 days of gestation. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. A compound presentation and a prolonged second stage of labor made vacuum assistance necessary. The infant had both a true umbilical cord knot (TUCK) (FIGURE 1A) and double nuchal cord.

CASE 2 › A 46-year-old G3P0 at 38 weeks of gestation by in vitro fertilization underwent an uncomplicated primary low transverse cesarean (C-section) delivery of dichorionic/diamniotic twins. The C-section had been necessary because baby A had been in the breech position. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. Baby A had a velamentous cord insertion, and baby B had a succenturiate lobe and a TUCK.

CASE 3 › A 23-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course chose to have a repeat C-section and delivered at 41 weeks in active labor. Fetal heart monitoring showed no abnormalities. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK was noted at time of delivery.

CASE 4 › A 30-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented in active labor at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. At 7 cm cervical dilation, monitoring showed repeated deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations. The patient underwent an uncomplicated primary C-section. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK (FIGURE 1B) and double nuchal cord were found at time of delivery.

DISCUSSION

TUCKs are thought to occur when a fetus passes through a loop in the umbilical cord. They occur in <2% of term deliveries.1,2 TUCKs differ from false knots. False knots are exaggerated loops of cord vasculature.

Risk factors that have been independently associated with TUCK include advanced maternal age (AMA; >35 years), multiparity, diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polyhydramnios, and previous spontaneous abortion.1-3 In one study, 72% of women with a TUCK were multiparous.3 Hershkovitz et al2 suggested that laxity of uterine and abdominal musculature in multiparous patients may contribute to increased room for TUCK formation.

The adjusted odds ratio of having a TUCK is 2.53 in women with diabetes mellitus.3 Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased fetal movements, thereby increasing the risk of TUCK development.2 Polyhydramnios is often found in patients with diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes.3 The incidence is higher in monoamniotic twins.4

Being a male and having a longer umbilical cord may also increase the risk of TUCK. On average, male infants have longer cords than females, which may predispose them to TUCKs.3 Räisänen et al3 found that the mean cord length in TUCK infants was 16.9 cm longer than in infants without a TUCK.

Of our 4 patients, one was of AMA, 2 were multiparous, and 3 of the 4 infants who developed TUCK were male.

TUCK is usually diagnosed at delivery

Most cases of TUCK are found incidentally at the time of delivery. Antenatal diagnosis is difficult, because loops of cord lying together are easily mistaken for knots on ultrasound.5 Sepulveda et al6 evaluated the use of 3D power Doppler in 8 cases of suspected TUCK; only 63% were confirmed at delivery. Some researchers have found improved detection of TUCK with color Doppler and 4D ultrasound, which have demonstrated a “hanging noose sign” (a transverse section of umbilical cord surrounded by a loop of cord) as well as views of the cord under pressure.7-10

Outcomes associated with TUCK vary greatly. Neonates affected by TUCK have a 4% to 10% increased risk of stillbirth, usually attributed to knot tightening.2,4,11,12

In addition, there is an increased incidence of fetal heart rate abnormalities during labor.1,3,12,13

There is no increase in the incidence of assisted vaginal or C-section delivery.12 And as for whether TUCK affects an infant’s size or weight, one study found TUCK infants had a 3.2-fold higher risk of measuring small for gestational age, potentially due to chronic umbilical cord compromise; however, mean birth weight between study and control groups did not differ significantly.3

Outcomes for our patients and their infants. All 4 cases had good outcomes (TABLE). The umbilical cord knot produced no detectable fetal compromise in cases 1 through 3. In Case 4, electronic fetal monitoring showed repeated variable fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably associated with cord compression.

THE TAKEAWAY

Pregnant women who may be at risk for experiencing a TUCK include those who are older than age 35, multiparous, carrying a boy, or have diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, or polyhydramnios. While it is good to be aware of these risk factors, there are no recommended changes in management based on risk or ultrasound findings unless there is additional concern for fetal compromise.

Antenatal diagnosis of TUCK is challenging, but Doppler ultrasound may be able to identify the condition. Most cases of TUCK are noted on delivery, and outcomes are generally positive, although infants in whom the TUCK tightens may have an increased risk of heart rate abnormalities or stillbirth.

THE CASES

CASE 1 › A 32-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented for induction at 41 weeks and 2 days of gestation. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. A compound presentation and a prolonged second stage of labor made vacuum assistance necessary. The infant had both a true umbilical cord knot (TUCK) (FIGURE 1A) and double nuchal cord.

CASE 2 › A 46-year-old G3P0 at 38 weeks of gestation by in vitro fertilization underwent an uncomplicated primary low transverse cesarean (C-section) delivery of dichorionic/diamniotic twins. The C-section had been necessary because baby A had been in the breech position. Fetal heart tracing showed no abnormalities. Baby A had a velamentous cord insertion, and baby B had a succenturiate lobe and a TUCK.

CASE 3 › A 23-year-old G2P1 with an uncomplicated prenatal course chose to have a repeat C-section and delivered at 41 weeks in active labor. Fetal heart monitoring showed no abnormalities. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK was noted at time of delivery.

CASE 4 › A 30-year-old G1P0 with an uncomplicated prenatal course presented in active labor at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. At 7 cm cervical dilation, monitoring showed repeated deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations. The patient underwent an uncomplicated primary C-section. Umbilical artery pH and venous pH were normal. A TUCK (FIGURE 1B) and double nuchal cord were found at time of delivery.

DISCUSSION

TUCKs are thought to occur when a fetus passes through a loop in the umbilical cord. They occur in <2% of term deliveries.1,2 TUCKs differ from false knots. False knots are exaggerated loops of cord vasculature.

Risk factors that have been independently associated with TUCK include advanced maternal age (AMA; >35 years), multiparity, diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, polyhydramnios, and previous spontaneous abortion.1-3 In one study, 72% of women with a TUCK were multiparous.3 Hershkovitz et al2 suggested that laxity of uterine and abdominal musculature in multiparous patients may contribute to increased room for TUCK formation.

The adjusted odds ratio of having a TUCK is 2.53 in women with diabetes mellitus.3 Hyperglycemia can contribute to increased fetal movements, thereby increasing the risk of TUCK development.2 Polyhydramnios is often found in patients with diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes.3 The incidence is higher in monoamniotic twins.4

Being a male and having a longer umbilical cord may also increase the risk of TUCK. On average, male infants have longer cords than females, which may predispose them to TUCKs.3 Räisänen et al3 found that the mean cord length in TUCK infants was 16.9 cm longer than in infants without a TUCK.

Of our 4 patients, one was of AMA, 2 were multiparous, and 3 of the 4 infants who developed TUCK were male.

TUCK is usually diagnosed at delivery

Most cases of TUCK are found incidentally at the time of delivery. Antenatal diagnosis is difficult, because loops of cord lying together are easily mistaken for knots on ultrasound.5 Sepulveda et al6 evaluated the use of 3D power Doppler in 8 cases of suspected TUCK; only 63% were confirmed at delivery. Some researchers have found improved detection of TUCK with color Doppler and 4D ultrasound, which have demonstrated a “hanging noose sign” (a transverse section of umbilical cord surrounded by a loop of cord) as well as views of the cord under pressure.7-10

Outcomes associated with TUCK vary greatly. Neonates affected by TUCK have a 4% to 10% increased risk of stillbirth, usually attributed to knot tightening.2,4,11,12

In addition, there is an increased incidence of fetal heart rate abnormalities during labor.1,3,12,13

There is no increase in the incidence of assisted vaginal or C-section delivery.12 And as for whether TUCK affects an infant’s size or weight, one study found TUCK infants had a 3.2-fold higher risk of measuring small for gestational age, potentially due to chronic umbilical cord compromise; however, mean birth weight between study and control groups did not differ significantly.3

Outcomes for our patients and their infants. All 4 cases had good outcomes (TABLE). The umbilical cord knot produced no detectable fetal compromise in cases 1 through 3. In Case 4, electronic fetal monitoring showed repeated variable fetal heart rate decelerations, presumably associated with cord compression.

THE TAKEAWAY

Pregnant women who may be at risk for experiencing a TUCK include those who are older than age 35, multiparous, carrying a boy, or have diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes, or polyhydramnios. While it is good to be aware of these risk factors, there are no recommended changes in management based on risk or ultrasound findings unless there is additional concern for fetal compromise.

Antenatal diagnosis of TUCK is challenging, but Doppler ultrasound may be able to identify the condition. Most cases of TUCK are noted on delivery, and outcomes are generally positive, although infants in whom the TUCK tightens may have an increased risk of heart rate abnormalities or stillbirth.

1. Joura EA, Zeisler H, Sator MO. Epidemiology and clinical value of true umbilical cord knots [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:232-235.

2. Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, et al. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:36-39.

3. Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, et al. True umbilical cord knot and obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122: 18-21.

4. Maher JT, Conti JA. A comparison of umbilical cord blood gas values between newborns with and without true knots. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:863-866.

5. Clerici G, Koutras I, Luzietti R, et al. Multiple true umbilical knots: a silent risk for intrauterine growth restriction with anomalous hemodynamic pattern. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:440-443.

6. Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, et al. True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:106-108.

7. Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1215-1220.

8. Rodriguez N, Angarita AM, Casasbuenas A, et al. Three-dimensional high-definition flow imaging in prenatal diagnosis of a true umbilical cord knot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:245-246.

9. Scioscia M, Fornalè M, Bruni F, et al. Four-dimensional and Doppler sonography in the diagnosis and surveillance of a true cord knot. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39: 157-159.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Zigalo A, et al. Power Doppler and 3-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of multiple separate true knots of the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24: 1321-1323.

11. Sørnes T. Umbilical cord knots. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:157-159.

12. Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:127-132.

13. Szczepanik ME, Wittich AC. True knot of the umbilical cord: a report of 13 cases. Mil Med. 2007;172:892-894.

1. Joura EA, Zeisler H, Sator MO. Epidemiology and clinical value of true umbilical cord knots [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;110:232-235.

2. Hershkovitz R, Silberstein T, Sheiner E, et al. Risk factors associated with true knots of the umbilical cord. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:36-39.

3. Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, et al. True umbilical cord knot and obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122: 18-21.

4. Maher JT, Conti JA. A comparison of umbilical cord blood gas values between newborns with and without true knots. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:863-866.

5. Clerici G, Koutras I, Luzietti R, et al. Multiple true umbilical knots: a silent risk for intrauterine growth restriction with anomalous hemodynamic pattern. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2007;22:440-443.

6. Sepulveda W, Shennan AH, Bower S, et al. True knot of the umbilical cord: a difficult prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;5:106-108.

7. Hasbun J, Alcalde JL, Sepulveda W. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography in the prenatal diagnosis of a true knot of the umbilical cord: value and limitations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1215-1220.

8. Rodriguez N, Angarita AM, Casasbuenas A, et al. Three-dimensional high-definition flow imaging in prenatal diagnosis of a true umbilical cord knot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:245-246.

9. Scioscia M, Fornalè M, Bruni F, et al. Four-dimensional and Doppler sonography in the diagnosis and surveillance of a true cord knot. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011;39: 157-159.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Zigalo A, et al. Power Doppler and 3-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of multiple separate true knots of the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24: 1321-1323.

11. Sørnes T. Umbilical cord knots. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:157-159.

12. Airas U, Heinonen S. Clinical significance of true umbilical knots: a population-based analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:127-132.

13. Szczepanik ME, Wittich AC. True knot of the umbilical cord: a report of 13 cases. Mil Med. 2007;172:892-894.

Radiating low back pain • history of urinary symptoms • past surgery for scoliosis • Dx?

THE CASE

A 23-year-old immunocompetent woman was referred to our spinal clinic with a 6-month history of low back pain that radiated to her right flank, buttock, and groin. She’d had intermittent urinary problems, including mild dysuria and frequency, and had been treated with antibiotics for a presumed urinary tract infection on 3 previous occasions, but her pain gradually increased and eventually became constant.

The patient had no history of fever, malaise, or weight loss. She denied consuming unpasteurized milk or undercooked poultry, and hadn’t recently experienced diarrhea or vomiting.

Eight years earlier, she had undergone anterior fusion of her spine for idiopathic scoliosis. At that time, she was at Risser grade 1, and her Cobb angle was 50°; metallic instrumentation was implanted at T10 to L3 to prevent progression of the scoliosis. Her recovery had been uneventful.

During examination, her temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and nervous system were all normal. Her hips appeared normal, as well, and a straight leg raise was negative bilaterally. The patient had mild midline lumbar tenderness. Spinal range of movement revealed decreased flexion and mild pain.

X-rays (FIGURE 1) showed no changes in the previous metalwork in her spine. There was decreased disk height at the L3/4 level, but no significant bony erosion or soft-tissue shadows. Laboratory testing revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 240 mg/dL (normal, <1 mg/dL) and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 102 mm/h—more than 5 times higher than it should have been.1 The patient had a normal peripheral white cell count (WCC). Midstream urine cultures were negative.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine showed gross abnormality at the L3-L4 disk level with erosion of the end plates, fluid in the disk space, marked enhancing edema, and mild surrounding soft-tissue edematous changes, but no evidence of any epidural abscess (FIGURE 2). The patient had a fluoroscopy-guided needle biopsy of the disk on the same day and received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g twice a day. Blood and urine cultures were negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We suspected our patient had spondylodiscitis, an infection of the spine that includes spondylitis (inflammation of the vertebrae) and discitis (inflammation of the vertebral disk space). After 48 hours, the biopsy sample grew Salmonella typhimurium and confirmed the diagnosis. The organism was sensitive to ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin; parenteral ceftriaxone was continued and the patient wore a thoracolumbar brace for immobilization. For 3 days, her inflammatory marker levels were checked daily, then every other day for the rest of that first week, and then 2 more times in the following week.

DISCUSSION

Thoracic and lumbar vertebrae are the most common sites of spondylodiscitis.2 Spondylodiscitis accounts for 3% to 5% of pyogenic osteomyelitis in patients in developed countries.3 The incidence of pyogenic spondylodiscitis may be rising due to an increase in the number of elderly and immunocompromised patients, as well as a rise in invasive medical procedures.4-6

If left untreated, spondylodiscitis can spread longitudinally (involving the adjacent levels), posteriorly (causing bacterial meningitis, abscess formation, and cord compromise), or anteriorly (causing paravertebral abscess). Untreated spondylodiscitis can also send distant infective emboli and cause endocarditis7-9 or mycotic abdominal aneurysm.10

Historically, mortality in patients with vertebral osteomyelitis has been as high as 25%.11 The combination of earlier diagnosis, antibiotics, and surgical debridement and stabilization has decreased mortality to less than 15%.12-14

Risk factors for spondylodiscitis include male sex, IV drug abuse, diabetes, morbid obesity, having had a genitourinary or spinal procedure, and being immunocompromised (eg, from alcohol abuse, malignancy, organ transplantation, chemotherapy, or corticosteroid use).12,15,16

Gram-positive organisms cause most spine infections in both adults and children, with 40% to 90% caused by Staphylococcus aureus.17 Gram-negative organisms (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, and Proteus), which can also cause spondylodiscitis, typically occur after genitourinary infections or procedures. IV drug abusers are prone to Pseudomonas infections.18 Anaerobic infections may be seen in patients with diabetes or after penetrating trauma.15 Salmonella species can cause spondylodiscitis, especially in patients with sickle cell disease from an intestinal source.19

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common nonpyogenic infecting agent that also can cause spondylodiscitis. Infection caused by tuberculosis (TB) has had a recent resurgence with resistant strains, especially in patients with human immunodeficiency virus.15 Although less than 10% of patients with TB have skeletal involvement, 50% of the skeletal involvement occurs in the spine.15

The clinical presentation of spondylodiscitis depends on the location of the infection, the virulence of the organism, and the immune status of the patient. Discitis can present as pain in the back, hip, abdomen (especially in children20) and, occasionally, with meningeal involvement.11 Patients with discitis often have a normal temperature.15,21 In patients with discitis, the patient’s WCC will be normal, but the ESR is almost always elevated.15,22 Suspect spondylodiscitis in patients who present with persistent or increasing pain 3 to 4 weeks after back surgery. For such patients, measure inflammatory markers and order imaging of the spine.

X-ray findings for patients with spondylodiscitis will include osteolysis and end plate erosions (early) and narrowing and collapse of the disk space (late). (In TB, relative preservation of the disk spaces is seen, with significant vertebral destruction.)

MRI is the modality of choice for diagnosis and assessment of suspected spondylodiscitis because it can provide imaging of the soft tissue, neural elements, and bony changes with a high sensitivity and specificity.23 Once infection is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by fluoroscopic- or computed tomography-guided biopsy before starting antibiotic treatment.

Long-term antibiotics are required to prevent recurrence

IV antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for spondylodiscitis;24 the specific drug used will depend upon the organism identified. Patients typically receive 2 to 6 weeks of IV therapy. Then, once the patient improves and inflammatory markers return to normal levels, the patient receives a course of oral antibiotics for 2 to 6 more weeks. Grados et al19 found recurrence rates of 10% to 15% for patients who were treated 4 to 8 weeks compared to 3.9% in those treated for 12 weeks or longer; therefore, a total duration of 12 weeks is commonly chosen.25-28

To minimize the risk of spondylolisthesis, kyphosis, and fractures of the infected bone, patients are advised to rest and the spine is often immobilized with a spinal brace. Surgery may be needed if antibiotics are not effective, or for patients who develop complications such as fluid collection, neurologic deficits, or deformity.

Our patient’s pain improved after 2 weeks and she became more comfortable wearing the thoracolumbar brace. Her CRP and ESR also improved and there was no radiologic evidence of fluid collection. The patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter in place and received IV ceftriaxone for 6 more weeks at home. This was followed by 4 weeks of oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily, thereby completing a 12-week course of antibiotics.

Our patient’s response to treatment was monitored clinically and the inflammatory markers were checked weekly after discharge until the end of treatment and at 6 and 12 months after start of treatment. At 12 months, our patient’s CRP was <1 mg/dL and ESR was 22 mm/h. One year later, our patient remained asymptomatic with normal inflammatory marker levels and no evidence of recurrence.

THE TAKEAWAY

Spondylodiscitis is an important differential diagnosis of lower back, flank, groin, and buttock pain. It’s important to be aware of this diagnosis, especially in patients who have risk factors such as IV drug abuse, diabetes, and morbid obesity. Although previous spinal surgery is a risk factor, spondylodiscitis should be considered in patients with persistent back pain even if they haven’t had spinal surgery. It can be present even when there is no tenderness over the spinous process or any fever.

Checking inflammatory markers is a reasonable next step if a patient’s pain does not resolve after at least 4 weeks. If levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP and ESR are elevated and symptoms continue, MRI can confirm or rule out the presence of spondylodiscitis. Treatments include orthotic support, antibiotics, and surgical intervention when complications arise.

1. Miller A, Green M, Robinson D. Simple rule for calculating normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Br Med J. 1983;286:266.

2. Calhoun JH, Manring MM. Adult osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:765-786.

3. Sobottke R, Seifert H, Fätkenheuer G, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:181-187.

4. Beronius M, Bergman B, Andersson R. Vertebral osteomyelitis in Göteborg, Sweden: a retrospective study of patients during 1990-95. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:527-532.

5. Digby JM, Kersley JB. Pyogenic non-tuberculous spinal infection: an analysis of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61: 47-55.

6. Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65 suppl 3:iii11-iii24.

7. Aoki K, Watanabe M, Ohzeki H. Successful surgical treatment of tricuspid valve endocarditis associated with vertebral osteomyelitis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:207-209.

8. Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Testa-Fernandez A, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Septic discitis as initial manifestation of streptococcus bovis endocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:128-129.

9. Morelli S, Carmenini E, Caporossi AP, et al. Spondylodiscitis and infective endocarditis: case studies and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:499-500.

10. Learch TJ, Sakamoto B, Ling AC, et al. Salmonella spondylodiscitis associated with a mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm and paravertebral abscess. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:147-150.

11. Guri JP. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1946;28:29-39.

12. Carragee EJ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:874-880.

13. Garcia A Jr, Grantham SA. Hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42-A:429-436.

14. Eismont FJ, Bohlman HH, Soni PL, et al. Pyogenic and fungal vertebral osteomyelitis with paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:19-29.

15. Tay BK, Deckey J, Hu SS. Spinal infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:188-197.

16. Krogsgaard MR, Wagn P, Bengtsson J. Epidemiology of acute vertebral osteomyelitis in Denmark: 137 cases in Denmark 1978-1982, compared to cases reported to the National Patient Register 1991-1993. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:513-517.

17. Francis X. Infections of spine. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 11th ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:2241.

18. Roca RP, Yoshikawa TT. Primary skeletal infections in heroin users: a clinical characterization, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(144):238-248.

19. Grados F, Lescure FX, Senneville E, et al. Suggestions for managing pyogenic (non-tuberculous) discitis in adults. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:133-139.

20. Cheyne G, Runau F, Lloyd DM. Right upper quadrant pain and raised alkaline phosphatase is not always a hepatobiliary problem. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:118E-120E.

21. Varma R, Lander P, Assaf A. Imaging of pyogenic infectious spondylodiskitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39: 203-213.

22. Lehovsky J. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis/disc infection. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13:59-75.

23. Modic MT, Feiglin DH, Piraino DW, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: assessment using MR. Radiology. 1985;157:157-166.

24. Amritanand R, Venkatesh K, Sundararaj GD. Salmonella spondylodiscitis in the immunocompetent: our experience with eleven patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1317-E1321.

25. Govender S. Spinal infections. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1454-1458.

26. Lam KS, Webb JK. Discitis. Hosp Med. 2004;65:280-286.

27. Gasbarrini AL, Bertoldi E, Mazzetti M, et al. Clinical features, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to haematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9: 53-66.

28. Cottle L, Riordan T. Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Infect. 2008;56:401-412.

THE CASE

A 23-year-old immunocompetent woman was referred to our spinal clinic with a 6-month history of low back pain that radiated to her right flank, buttock, and groin. She’d had intermittent urinary problems, including mild dysuria and frequency, and had been treated with antibiotics for a presumed urinary tract infection on 3 previous occasions, but her pain gradually increased and eventually became constant.

The patient had no history of fever, malaise, or weight loss. She denied consuming unpasteurized milk or undercooked poultry, and hadn’t recently experienced diarrhea or vomiting.

Eight years earlier, she had undergone anterior fusion of her spine for idiopathic scoliosis. At that time, she was at Risser grade 1, and her Cobb angle was 50°; metallic instrumentation was implanted at T10 to L3 to prevent progression of the scoliosis. Her recovery had been uneventful.

During examination, her temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and nervous system were all normal. Her hips appeared normal, as well, and a straight leg raise was negative bilaterally. The patient had mild midline lumbar tenderness. Spinal range of movement revealed decreased flexion and mild pain.

X-rays (FIGURE 1) showed no changes in the previous metalwork in her spine. There was decreased disk height at the L3/4 level, but no significant bony erosion or soft-tissue shadows. Laboratory testing revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 240 mg/dL (normal, <1 mg/dL) and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 102 mm/h—more than 5 times higher than it should have been.1 The patient had a normal peripheral white cell count (WCC). Midstream urine cultures were negative.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine showed gross abnormality at the L3-L4 disk level with erosion of the end plates, fluid in the disk space, marked enhancing edema, and mild surrounding soft-tissue edematous changes, but no evidence of any epidural abscess (FIGURE 2). The patient had a fluoroscopy-guided needle biopsy of the disk on the same day and received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g twice a day. Blood and urine cultures were negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We suspected our patient had spondylodiscitis, an infection of the spine that includes spondylitis (inflammation of the vertebrae) and discitis (inflammation of the vertebral disk space). After 48 hours, the biopsy sample grew Salmonella typhimurium and confirmed the diagnosis. The organism was sensitive to ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin; parenteral ceftriaxone was continued and the patient wore a thoracolumbar brace for immobilization. For 3 days, her inflammatory marker levels were checked daily, then every other day for the rest of that first week, and then 2 more times in the following week.

DISCUSSION

Thoracic and lumbar vertebrae are the most common sites of spondylodiscitis.2 Spondylodiscitis accounts for 3% to 5% of pyogenic osteomyelitis in patients in developed countries.3 The incidence of pyogenic spondylodiscitis may be rising due to an increase in the number of elderly and immunocompromised patients, as well as a rise in invasive medical procedures.4-6

If left untreated, spondylodiscitis can spread longitudinally (involving the adjacent levels), posteriorly (causing bacterial meningitis, abscess formation, and cord compromise), or anteriorly (causing paravertebral abscess). Untreated spondylodiscitis can also send distant infective emboli and cause endocarditis7-9 or mycotic abdominal aneurysm.10

Historically, mortality in patients with vertebral osteomyelitis has been as high as 25%.11 The combination of earlier diagnosis, antibiotics, and surgical debridement and stabilization has decreased mortality to less than 15%.12-14

Risk factors for spondylodiscitis include male sex, IV drug abuse, diabetes, morbid obesity, having had a genitourinary or spinal procedure, and being immunocompromised (eg, from alcohol abuse, malignancy, organ transplantation, chemotherapy, or corticosteroid use).12,15,16

Gram-positive organisms cause most spine infections in both adults and children, with 40% to 90% caused by Staphylococcus aureus.17 Gram-negative organisms (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, and Proteus), which can also cause spondylodiscitis, typically occur after genitourinary infections or procedures. IV drug abusers are prone to Pseudomonas infections.18 Anaerobic infections may be seen in patients with diabetes or after penetrating trauma.15 Salmonella species can cause spondylodiscitis, especially in patients with sickle cell disease from an intestinal source.19

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common nonpyogenic infecting agent that also can cause spondylodiscitis. Infection caused by tuberculosis (TB) has had a recent resurgence with resistant strains, especially in patients with human immunodeficiency virus.15 Although less than 10% of patients with TB have skeletal involvement, 50% of the skeletal involvement occurs in the spine.15

The clinical presentation of spondylodiscitis depends on the location of the infection, the virulence of the organism, and the immune status of the patient. Discitis can present as pain in the back, hip, abdomen (especially in children20) and, occasionally, with meningeal involvement.11 Patients with discitis often have a normal temperature.15,21 In patients with discitis, the patient’s WCC will be normal, but the ESR is almost always elevated.15,22 Suspect spondylodiscitis in patients who present with persistent or increasing pain 3 to 4 weeks after back surgery. For such patients, measure inflammatory markers and order imaging of the spine.

X-ray findings for patients with spondylodiscitis will include osteolysis and end plate erosions (early) and narrowing and collapse of the disk space (late). (In TB, relative preservation of the disk spaces is seen, with significant vertebral destruction.)

MRI is the modality of choice for diagnosis and assessment of suspected spondylodiscitis because it can provide imaging of the soft tissue, neural elements, and bony changes with a high sensitivity and specificity.23 Once infection is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by fluoroscopic- or computed tomography-guided biopsy before starting antibiotic treatment.

Long-term antibiotics are required to prevent recurrence

IV antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for spondylodiscitis;24 the specific drug used will depend upon the organism identified. Patients typically receive 2 to 6 weeks of IV therapy. Then, once the patient improves and inflammatory markers return to normal levels, the patient receives a course of oral antibiotics for 2 to 6 more weeks. Grados et al19 found recurrence rates of 10% to 15% for patients who were treated 4 to 8 weeks compared to 3.9% in those treated for 12 weeks or longer; therefore, a total duration of 12 weeks is commonly chosen.25-28

To minimize the risk of spondylolisthesis, kyphosis, and fractures of the infected bone, patients are advised to rest and the spine is often immobilized with a spinal brace. Surgery may be needed if antibiotics are not effective, or for patients who develop complications such as fluid collection, neurologic deficits, or deformity.

Our patient’s pain improved after 2 weeks and she became more comfortable wearing the thoracolumbar brace. Her CRP and ESR also improved and there was no radiologic evidence of fluid collection. The patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter in place and received IV ceftriaxone for 6 more weeks at home. This was followed by 4 weeks of oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily, thereby completing a 12-week course of antibiotics.

Our patient’s response to treatment was monitored clinically and the inflammatory markers were checked weekly after discharge until the end of treatment and at 6 and 12 months after start of treatment. At 12 months, our patient’s CRP was <1 mg/dL and ESR was 22 mm/h. One year later, our patient remained asymptomatic with normal inflammatory marker levels and no evidence of recurrence.

THE TAKEAWAY

Spondylodiscitis is an important differential diagnosis of lower back, flank, groin, and buttock pain. It’s important to be aware of this diagnosis, especially in patients who have risk factors such as IV drug abuse, diabetes, and morbid obesity. Although previous spinal surgery is a risk factor, spondylodiscitis should be considered in patients with persistent back pain even if they haven’t had spinal surgery. It can be present even when there is no tenderness over the spinous process or any fever.

Checking inflammatory markers is a reasonable next step if a patient’s pain does not resolve after at least 4 weeks. If levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP and ESR are elevated and symptoms continue, MRI can confirm or rule out the presence of spondylodiscitis. Treatments include orthotic support, antibiotics, and surgical intervention when complications arise.

THE CASE

A 23-year-old immunocompetent woman was referred to our spinal clinic with a 6-month history of low back pain that radiated to her right flank, buttock, and groin. She’d had intermittent urinary problems, including mild dysuria and frequency, and had been treated with antibiotics for a presumed urinary tract infection on 3 previous occasions, but her pain gradually increased and eventually became constant.

The patient had no history of fever, malaise, or weight loss. She denied consuming unpasteurized milk or undercooked poultry, and hadn’t recently experienced diarrhea or vomiting.

Eight years earlier, she had undergone anterior fusion of her spine for idiopathic scoliosis. At that time, she was at Risser grade 1, and her Cobb angle was 50°; metallic instrumentation was implanted at T10 to L3 to prevent progression of the scoliosis. Her recovery had been uneventful.

During examination, her temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and nervous system were all normal. Her hips appeared normal, as well, and a straight leg raise was negative bilaterally. The patient had mild midline lumbar tenderness. Spinal range of movement revealed decreased flexion and mild pain.

X-rays (FIGURE 1) showed no changes in the previous metalwork in her spine. There was decreased disk height at the L3/4 level, but no significant bony erosion or soft-tissue shadows. Laboratory testing revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 240 mg/dL (normal, <1 mg/dL) and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 102 mm/h—more than 5 times higher than it should have been.1 The patient had a normal peripheral white cell count (WCC). Midstream urine cultures were negative.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine showed gross abnormality at the L3-L4 disk level with erosion of the end plates, fluid in the disk space, marked enhancing edema, and mild surrounding soft-tissue edematous changes, but no evidence of any epidural abscess (FIGURE 2). The patient had a fluoroscopy-guided needle biopsy of the disk on the same day and received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g twice a day. Blood and urine cultures were negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We suspected our patient had spondylodiscitis, an infection of the spine that includes spondylitis (inflammation of the vertebrae) and discitis (inflammation of the vertebral disk space). After 48 hours, the biopsy sample grew Salmonella typhimurium and confirmed the diagnosis. The organism was sensitive to ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin; parenteral ceftriaxone was continued and the patient wore a thoracolumbar brace for immobilization. For 3 days, her inflammatory marker levels were checked daily, then every other day for the rest of that first week, and then 2 more times in the following week.

DISCUSSION

Thoracic and lumbar vertebrae are the most common sites of spondylodiscitis.2 Spondylodiscitis accounts for 3% to 5% of pyogenic osteomyelitis in patients in developed countries.3 The incidence of pyogenic spondylodiscitis may be rising due to an increase in the number of elderly and immunocompromised patients, as well as a rise in invasive medical procedures.4-6

If left untreated, spondylodiscitis can spread longitudinally (involving the adjacent levels), posteriorly (causing bacterial meningitis, abscess formation, and cord compromise), or anteriorly (causing paravertebral abscess). Untreated spondylodiscitis can also send distant infective emboli and cause endocarditis7-9 or mycotic abdominal aneurysm.10

Historically, mortality in patients with vertebral osteomyelitis has been as high as 25%.11 The combination of earlier diagnosis, antibiotics, and surgical debridement and stabilization has decreased mortality to less than 15%.12-14

Risk factors for spondylodiscitis include male sex, IV drug abuse, diabetes, morbid obesity, having had a genitourinary or spinal procedure, and being immunocompromised (eg, from alcohol abuse, malignancy, organ transplantation, chemotherapy, or corticosteroid use).12,15,16

Gram-positive organisms cause most spine infections in both adults and children, with 40% to 90% caused by Staphylococcus aureus.17 Gram-negative organisms (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, and Proteus), which can also cause spondylodiscitis, typically occur after genitourinary infections or procedures. IV drug abusers are prone to Pseudomonas infections.18 Anaerobic infections may be seen in patients with diabetes or after penetrating trauma.15 Salmonella species can cause spondylodiscitis, especially in patients with sickle cell disease from an intestinal source.19

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common nonpyogenic infecting agent that also can cause spondylodiscitis. Infection caused by tuberculosis (TB) has had a recent resurgence with resistant strains, especially in patients with human immunodeficiency virus.15 Although less than 10% of patients with TB have skeletal involvement, 50% of the skeletal involvement occurs in the spine.15

The clinical presentation of spondylodiscitis depends on the location of the infection, the virulence of the organism, and the immune status of the patient. Discitis can present as pain in the back, hip, abdomen (especially in children20) and, occasionally, with meningeal involvement.11 Patients with discitis often have a normal temperature.15,21 In patients with discitis, the patient’s WCC will be normal, but the ESR is almost always elevated.15,22 Suspect spondylodiscitis in patients who present with persistent or increasing pain 3 to 4 weeks after back surgery. For such patients, measure inflammatory markers and order imaging of the spine.

X-ray findings for patients with spondylodiscitis will include osteolysis and end plate erosions (early) and narrowing and collapse of the disk space (late). (In TB, relative preservation of the disk spaces is seen, with significant vertebral destruction.)

MRI is the modality of choice for diagnosis and assessment of suspected spondylodiscitis because it can provide imaging of the soft tissue, neural elements, and bony changes with a high sensitivity and specificity.23 Once infection is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by fluoroscopic- or computed tomography-guided biopsy before starting antibiotic treatment.

Long-term antibiotics are required to prevent recurrence

IV antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for spondylodiscitis;24 the specific drug used will depend upon the organism identified. Patients typically receive 2 to 6 weeks of IV therapy. Then, once the patient improves and inflammatory markers return to normal levels, the patient receives a course of oral antibiotics for 2 to 6 more weeks. Grados et al19 found recurrence rates of 10% to 15% for patients who were treated 4 to 8 weeks compared to 3.9% in those treated for 12 weeks or longer; therefore, a total duration of 12 weeks is commonly chosen.25-28

To minimize the risk of spondylolisthesis, kyphosis, and fractures of the infected bone, patients are advised to rest and the spine is often immobilized with a spinal brace. Surgery may be needed if antibiotics are not effective, or for patients who develop complications such as fluid collection, neurologic deficits, or deformity.

Our patient’s pain improved after 2 weeks and she became more comfortable wearing the thoracolumbar brace. Her CRP and ESR also improved and there was no radiologic evidence of fluid collection. The patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter in place and received IV ceftriaxone for 6 more weeks at home. This was followed by 4 weeks of oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily, thereby completing a 12-week course of antibiotics.

Our patient’s response to treatment was monitored clinically and the inflammatory markers were checked weekly after discharge until the end of treatment and at 6 and 12 months after start of treatment. At 12 months, our patient’s CRP was <1 mg/dL and ESR was 22 mm/h. One year later, our patient remained asymptomatic with normal inflammatory marker levels and no evidence of recurrence.

THE TAKEAWAY

Spondylodiscitis is an important differential diagnosis of lower back, flank, groin, and buttock pain. It’s important to be aware of this diagnosis, especially in patients who have risk factors such as IV drug abuse, diabetes, and morbid obesity. Although previous spinal surgery is a risk factor, spondylodiscitis should be considered in patients with persistent back pain even if they haven’t had spinal surgery. It can be present even when there is no tenderness over the spinous process or any fever.

Checking inflammatory markers is a reasonable next step if a patient’s pain does not resolve after at least 4 weeks. If levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP and ESR are elevated and symptoms continue, MRI can confirm or rule out the presence of spondylodiscitis. Treatments include orthotic support, antibiotics, and surgical intervention when complications arise.

1. Miller A, Green M, Robinson D. Simple rule for calculating normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Br Med J. 1983;286:266.

2. Calhoun JH, Manring MM. Adult osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:765-786.

3. Sobottke R, Seifert H, Fätkenheuer G, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:181-187.

4. Beronius M, Bergman B, Andersson R. Vertebral osteomyelitis in Göteborg, Sweden: a retrospective study of patients during 1990-95. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:527-532.

5. Digby JM, Kersley JB. Pyogenic non-tuberculous spinal infection: an analysis of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61: 47-55.

6. Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65 suppl 3:iii11-iii24.

7. Aoki K, Watanabe M, Ohzeki H. Successful surgical treatment of tricuspid valve endocarditis associated with vertebral osteomyelitis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:207-209.

8. Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Testa-Fernandez A, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Septic discitis as initial manifestation of streptococcus bovis endocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:128-129.

9. Morelli S, Carmenini E, Caporossi AP, et al. Spondylodiscitis and infective endocarditis: case studies and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:499-500.

10. Learch TJ, Sakamoto B, Ling AC, et al. Salmonella spondylodiscitis associated with a mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm and paravertebral abscess. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:147-150.

11. Guri JP. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1946;28:29-39.

12. Carragee EJ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:874-880.

13. Garcia A Jr, Grantham SA. Hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42-A:429-436.

14. Eismont FJ, Bohlman HH, Soni PL, et al. Pyogenic and fungal vertebral osteomyelitis with paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:19-29.

15. Tay BK, Deckey J, Hu SS. Spinal infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:188-197.

16. Krogsgaard MR, Wagn P, Bengtsson J. Epidemiology of acute vertebral osteomyelitis in Denmark: 137 cases in Denmark 1978-1982, compared to cases reported to the National Patient Register 1991-1993. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:513-517.

17. Francis X. Infections of spine. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 11th ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:2241.

18. Roca RP, Yoshikawa TT. Primary skeletal infections in heroin users: a clinical characterization, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(144):238-248.

19. Grados F, Lescure FX, Senneville E, et al. Suggestions for managing pyogenic (non-tuberculous) discitis in adults. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:133-139.

20. Cheyne G, Runau F, Lloyd DM. Right upper quadrant pain and raised alkaline phosphatase is not always a hepatobiliary problem. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:118E-120E.

21. Varma R, Lander P, Assaf A. Imaging of pyogenic infectious spondylodiskitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39: 203-213.

22. Lehovsky J. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis/disc infection. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13:59-75.

23. Modic MT, Feiglin DH, Piraino DW, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: assessment using MR. Radiology. 1985;157:157-166.

24. Amritanand R, Venkatesh K, Sundararaj GD. Salmonella spondylodiscitis in the immunocompetent: our experience with eleven patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1317-E1321.

25. Govender S. Spinal infections. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1454-1458.

26. Lam KS, Webb JK. Discitis. Hosp Med. 2004;65:280-286.

27. Gasbarrini AL, Bertoldi E, Mazzetti M, et al. Clinical features, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to haematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9: 53-66.

28. Cottle L, Riordan T. Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Infect. 2008;56:401-412.

1. Miller A, Green M, Robinson D. Simple rule for calculating normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Br Med J. 1983;286:266.

2. Calhoun JH, Manring MM. Adult osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:765-786.

3. Sobottke R, Seifert H, Fätkenheuer G, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:181-187.

4. Beronius M, Bergman B, Andersson R. Vertebral osteomyelitis in Göteborg, Sweden: a retrospective study of patients during 1990-95. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:527-532.

5. Digby JM, Kersley JB. Pyogenic non-tuberculous spinal infection: an analysis of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61: 47-55.

6. Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65 suppl 3:iii11-iii24.

7. Aoki K, Watanabe M, Ohzeki H. Successful surgical treatment of tricuspid valve endocarditis associated with vertebral osteomyelitis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:207-209.

8. Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Testa-Fernandez A, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Septic discitis as initial manifestation of streptococcus bovis endocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:128-129.

9. Morelli S, Carmenini E, Caporossi AP, et al. Spondylodiscitis and infective endocarditis: case studies and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:499-500.

10. Learch TJ, Sakamoto B, Ling AC, et al. Salmonella spondylodiscitis associated with a mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm and paravertebral abscess. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:147-150.

11. Guri JP. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1946;28:29-39.

12. Carragee EJ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:874-880.

13. Garcia A Jr, Grantham SA. Hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42-A:429-436.

14. Eismont FJ, Bohlman HH, Soni PL, et al. Pyogenic and fungal vertebral osteomyelitis with paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:19-29.

15. Tay BK, Deckey J, Hu SS. Spinal infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:188-197.

16. Krogsgaard MR, Wagn P, Bengtsson J. Epidemiology of acute vertebral osteomyelitis in Denmark: 137 cases in Denmark 1978-1982, compared to cases reported to the National Patient Register 1991-1993. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:513-517.

17. Francis X. Infections of spine. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 11th ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:2241.

18. Roca RP, Yoshikawa TT. Primary skeletal infections in heroin users: a clinical characterization, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(144):238-248.

19. Grados F, Lescure FX, Senneville E, et al. Suggestions for managing pyogenic (non-tuberculous) discitis in adults. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:133-139.

20. Cheyne G, Runau F, Lloyd DM. Right upper quadrant pain and raised alkaline phosphatase is not always a hepatobiliary problem. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:118E-120E.

21. Varma R, Lander P, Assaf A. Imaging of pyogenic infectious spondylodiskitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39: 203-213.

22. Lehovsky J. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis/disc infection. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13:59-75.

23. Modic MT, Feiglin DH, Piraino DW, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: assessment using MR. Radiology. 1985;157:157-166.

24. Amritanand R, Venkatesh K, Sundararaj GD. Salmonella spondylodiscitis in the immunocompetent: our experience with eleven patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1317-E1321.

25. Govender S. Spinal infections. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1454-1458.

26. Lam KS, Webb JK. Discitis. Hosp Med. 2004;65:280-286.

27. Gasbarrini AL, Bertoldi E, Mazzetti M, et al. Clinical features, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to haematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9: 53-66.

28. Cottle L, Riordan T. Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Infect. 2008;56:401-412.

Suspect myopathy? Take this approach to the work-up

› Categorize patients with muscle complaints into suspected myositic, intrinsic, or toxic myopathy to help guide subsequent work-up. C

› Look for diffusely painful, swollen, or boggy-feeling muscles—as well as weakness and pain with exertion—in patients you suspect may have viral myopathy. C

› Consider electromyography and muscle biopsy for patients you suspect may have dermatomyositis. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Marie C, a 75-year-old Asian woman, reports weakness in her legs and arms with unsteadiness when walking. She has a vague but persistent ache in her large muscles. Her symptoms have developed slowly over the past 3 months. She denies recent signs or symptoms of infection or other illness. Her medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteopenia, and obesity. Ms. C takes lisinopril 10 mg/d and atorvastatin, which was recently increased from 10 to 20 mg/d.

What would your next steps be in caring for this patient?

Patients who experience muscle-related symptoms such as pain, fatigue, or weakness often seek help from their family physician (FP). The list of possible causes of these complaints can be lengthy and vary greatly, from nonmyopathic conditions such as fibromyalgia to worrisome forms of myopathy such as inclusion body myositis or polymyositis. This article will help you to quickly identify which patients with muscle-related complaints should be evaluated for myopathy and what your work-up should include.

Myopathy or not?

Distinguishing between myopathy and nonmyopathic muscle pain or weakness is the first step in evaluating patients with muscle-related complaints. Many conditions share muscle-related symptoms, but actual muscle damage is not always present (eg, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and chronic fatigue syndromes).1 While there is some overlap in presentation between patients with myopathy and nonmyopathic conditions, there are important differences in symptoms, physical exam findings, and lab test results (TABLE 11-4). Notably, in myopathic disease, patients’ symptoms are usually progressive, vital signs are abnormal, and weakness is common, whereas patients with nonmyopathic disease typically have remitting and relapsing symptoms, normal vital signs, and no weakness.

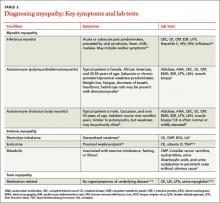

Myopathy itself is divided into 3 categories—myositic, intrinsic, and toxic—which reflect the condition, or medication, that brought on the muscle damage (TABLE 22,4-15). Placing patients into one of these categories based on their risk factors, history, and physical exam findings can help to focus the diagnostic work-up on areas most likely to provide useful information.

Myositic myopathy can be caused by infection or autoimmunity

Myositic myopathies result in inflammatory destruction of muscle tissue. Patients with myositic myopathy often exhibit fever, malaise, weight loss, and general fatigue. Though weakness and pain are common, both can be variable or even absent in myositic myopathy.2,5 Myositic myopathy can be caused by infectious agents or can develop from an autoimmune disease.

Infectious myositic myopathy is one of the more common types of myopathy that FPs will encounter.2 Viruses such as influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackievirus, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, echovirus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr, and hepatitis C are common causes.2,4,16 Bacterial and fungal myositides are relatively rare. Both most often occur as the result of penetrating trauma or immunocompromise, and are generally not subtle.2 Parasitic myopathy can occur from the invasion of skeletal muscle by trichinella after ingesting undercooked, infected meat.2 Although previously a more common problem, currently only 10 to 20 cases of trichinellosis are reported in the United States each year.17 Due to their rarity, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic myositides are not reviewed here.

Patients with a viral myositis often report prodromal symptoms such as fever, upper respiratory illness, or gastrointestinal distress one to 2 weeks before the onset of muscle complaints. Muscle pain is usually multifocal, involving larger, bilateral muscle groups, and may be associated with swelling.

Patients with viral myositis may exhibit diffusely painful, swollen, or boggy-feeling muscles as well as weakness and pain with exertion. Other signs of viral infection such as rash, fever, upper respiratory symptoms, or meningeal signs may be present. Severe signs include arrhythmia or respiratory failure due to cardiac muscle or diaphragm involvement, or signs of renal failure due to precipitation of myoglobin in the renal system (ie, rhabdomyolysis).2 If the infection affects the heart, patients may develop palpitations, pleuritic chest pain, or shortness of breath.2