User login

From the Washington Office

S…G…R (continued) – It is much to all of our collective delight and relief that the SGR has finally been relegated to the ash heap of history.

In the late evening of April 14, in an act of historic bipartisanship, the Senate voted 92-8 in favor of H.R. 2 thus completing legislative action about which I wrote last month. President Obama signed the bill into law on April 16. As I write, Dave Hoyt, ACS Executive Director, is attending an event at the White House, along with other leaders of the physician community, to celebrate the full and permanent repeal of the SGR.

In the coming months, I will use this column to inform surgeons about various components of the legislation and its attendant policy. To start this process, I would first like to cover the key provisions of what is now known as MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

For starters, MACRA fully and permanently repeals the sustainable growth rate (SGR), thus providing stability to the Medicare physician fee schedule. Such repeal averts a 21% SGR-induced cut scheduled for April 1, 2015. MACRA also provides modest but stable positive updates of 0.5%/year for 5 years. When the legislative template that ultimately became MACRA was negotiated in late 2013 and early 2014, no provision was initially made for a positive update to physician payment. However, as a direct result of objections made by the leadership of the ACS, the legislation was subsequently revised to include the 0.5%/year update.

In addition, MACRA provides for the elimination, in 2018, of the current-law penalties associated with the existing quality programs, namely the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Modifier (VBM) program, and the Electronic Health Record-Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. The monies expected from those penalties will be returned to the pool, thus increasing the amount of funds available for incentive updates.

Beginning in 2019, these three programs will be combined into a single program known as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). The MIPS makes it possible for all surgeons to receive an annual positive update based on their individual performance in four categories of Quality, Resource Use, Meaningful use of the electronic health record, and Clinical practice improvement activities. Surgeons will receive an annual, individual, single composite score based on their performance in these four categories. This score will be compared to a threshold score, defined as either the mean or median of composite scores from a prior performance period. Those with a score above the threshold will receive a positive adjustment and those with a score below the threshold will receive a negative adjustment.The legislation also provides the opportunity to receive a 5% bonus beginning in 2019 for participation in an Alternative Payment Model (APM). Surgeons who meet the full APM criteria will also be excluded from the MIPS assessment and most EHR-MU requirements. Those who participate in an APM at lower levels will receive credit toward their MIPS score. The bonus payment encourages the development of, testing of, and participation in an alternative payment model.

The passage of MACRA also represents a major victory relative to the College’s efforts to rescind the CMS policy transitioning 10- and 90-day global codes to zero-day global codes. ACS leadership and staff of the D.C. office had direct input into the specific language included in the legislation through multiple exchanges with congressional committee staff. In short, MACRA prohibits CMS from implementing its flawed plan relative to the transitioning of the global codes. Instead, beginning no later than 2017, CMS will collect samples of data on the number and level of postoperative visits furnished during the global period. Beginning in 2019, CMS will use this data to improve the accuracy of the valuation of surgical services. CMS is allowed to withhold 5% of the surgical payment until the sample information is reported at the end of the global period.

While MACRA does not implement broad medical liability reforms, it does include a provision which assures that MIPS participation cannot be used in a medical liability action. Specifically, the legislation specifies that the development, recognition or implementation of any guideline or other standard under any federal health care provision, including Medicare, cannot be construed as to establish the standard of care or duty of care owed by a surgeon to a patient in any medical malpractice claim.

Finally, and of particular interest to pediatric surgeons and other surgeons who care for children, MACRA includes two years of additional funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at the level provided under the Affordable Care Act.

Unfortunately, surgeons will need to become familiar with an entire new lexicon of acronyms associated with this new law and its policy. While this may initially seem daunting and confusing, it can be mastered with relative ease. It is my hope to continue to facilitate such with the content provided herein with the June edition of this column.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

S…G…R (continued) – It is much to all of our collective delight and relief that the SGR has finally been relegated to the ash heap of history.

In the late evening of April 14, in an act of historic bipartisanship, the Senate voted 92-8 in favor of H.R. 2 thus completing legislative action about which I wrote last month. President Obama signed the bill into law on April 16. As I write, Dave Hoyt, ACS Executive Director, is attending an event at the White House, along with other leaders of the physician community, to celebrate the full and permanent repeal of the SGR.

In the coming months, I will use this column to inform surgeons about various components of the legislation and its attendant policy. To start this process, I would first like to cover the key provisions of what is now known as MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

For starters, MACRA fully and permanently repeals the sustainable growth rate (SGR), thus providing stability to the Medicare physician fee schedule. Such repeal averts a 21% SGR-induced cut scheduled for April 1, 2015. MACRA also provides modest but stable positive updates of 0.5%/year for 5 years. When the legislative template that ultimately became MACRA was negotiated in late 2013 and early 2014, no provision was initially made for a positive update to physician payment. However, as a direct result of objections made by the leadership of the ACS, the legislation was subsequently revised to include the 0.5%/year update.

In addition, MACRA provides for the elimination, in 2018, of the current-law penalties associated with the existing quality programs, namely the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Modifier (VBM) program, and the Electronic Health Record-Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. The monies expected from those penalties will be returned to the pool, thus increasing the amount of funds available for incentive updates.

Beginning in 2019, these three programs will be combined into a single program known as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). The MIPS makes it possible for all surgeons to receive an annual positive update based on their individual performance in four categories of Quality, Resource Use, Meaningful use of the electronic health record, and Clinical practice improvement activities. Surgeons will receive an annual, individual, single composite score based on their performance in these four categories. This score will be compared to a threshold score, defined as either the mean or median of composite scores from a prior performance period. Those with a score above the threshold will receive a positive adjustment and those with a score below the threshold will receive a negative adjustment.The legislation also provides the opportunity to receive a 5% bonus beginning in 2019 for participation in an Alternative Payment Model (APM). Surgeons who meet the full APM criteria will also be excluded from the MIPS assessment and most EHR-MU requirements. Those who participate in an APM at lower levels will receive credit toward their MIPS score. The bonus payment encourages the development of, testing of, and participation in an alternative payment model.

The passage of MACRA also represents a major victory relative to the College’s efforts to rescind the CMS policy transitioning 10- and 90-day global codes to zero-day global codes. ACS leadership and staff of the D.C. office had direct input into the specific language included in the legislation through multiple exchanges with congressional committee staff. In short, MACRA prohibits CMS from implementing its flawed plan relative to the transitioning of the global codes. Instead, beginning no later than 2017, CMS will collect samples of data on the number and level of postoperative visits furnished during the global period. Beginning in 2019, CMS will use this data to improve the accuracy of the valuation of surgical services. CMS is allowed to withhold 5% of the surgical payment until the sample information is reported at the end of the global period.

While MACRA does not implement broad medical liability reforms, it does include a provision which assures that MIPS participation cannot be used in a medical liability action. Specifically, the legislation specifies that the development, recognition or implementation of any guideline or other standard under any federal health care provision, including Medicare, cannot be construed as to establish the standard of care or duty of care owed by a surgeon to a patient in any medical malpractice claim.

Finally, and of particular interest to pediatric surgeons and other surgeons who care for children, MACRA includes two years of additional funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at the level provided under the Affordable Care Act.

Unfortunately, surgeons will need to become familiar with an entire new lexicon of acronyms associated with this new law and its policy. While this may initially seem daunting and confusing, it can be mastered with relative ease. It is my hope to continue to facilitate such with the content provided herein with the June edition of this column.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

S…G…R (continued) – It is much to all of our collective delight and relief that the SGR has finally been relegated to the ash heap of history.

In the late evening of April 14, in an act of historic bipartisanship, the Senate voted 92-8 in favor of H.R. 2 thus completing legislative action about which I wrote last month. President Obama signed the bill into law on April 16. As I write, Dave Hoyt, ACS Executive Director, is attending an event at the White House, along with other leaders of the physician community, to celebrate the full and permanent repeal of the SGR.

In the coming months, I will use this column to inform surgeons about various components of the legislation and its attendant policy. To start this process, I would first like to cover the key provisions of what is now known as MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act.

For starters, MACRA fully and permanently repeals the sustainable growth rate (SGR), thus providing stability to the Medicare physician fee schedule. Such repeal averts a 21% SGR-induced cut scheduled for April 1, 2015. MACRA also provides modest but stable positive updates of 0.5%/year for 5 years. When the legislative template that ultimately became MACRA was negotiated in late 2013 and early 2014, no provision was initially made for a positive update to physician payment. However, as a direct result of objections made by the leadership of the ACS, the legislation was subsequently revised to include the 0.5%/year update.

In addition, MACRA provides for the elimination, in 2018, of the current-law penalties associated with the existing quality programs, namely the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Modifier (VBM) program, and the Electronic Health Record-Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. The monies expected from those penalties will be returned to the pool, thus increasing the amount of funds available for incentive updates.

Beginning in 2019, these three programs will be combined into a single program known as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). The MIPS makes it possible for all surgeons to receive an annual positive update based on their individual performance in four categories of Quality, Resource Use, Meaningful use of the electronic health record, and Clinical practice improvement activities. Surgeons will receive an annual, individual, single composite score based on their performance in these four categories. This score will be compared to a threshold score, defined as either the mean or median of composite scores from a prior performance period. Those with a score above the threshold will receive a positive adjustment and those with a score below the threshold will receive a negative adjustment.The legislation also provides the opportunity to receive a 5% bonus beginning in 2019 for participation in an Alternative Payment Model (APM). Surgeons who meet the full APM criteria will also be excluded from the MIPS assessment and most EHR-MU requirements. Those who participate in an APM at lower levels will receive credit toward their MIPS score. The bonus payment encourages the development of, testing of, and participation in an alternative payment model.

The passage of MACRA also represents a major victory relative to the College’s efforts to rescind the CMS policy transitioning 10- and 90-day global codes to zero-day global codes. ACS leadership and staff of the D.C. office had direct input into the specific language included in the legislation through multiple exchanges with congressional committee staff. In short, MACRA prohibits CMS from implementing its flawed plan relative to the transitioning of the global codes. Instead, beginning no later than 2017, CMS will collect samples of data on the number and level of postoperative visits furnished during the global period. Beginning in 2019, CMS will use this data to improve the accuracy of the valuation of surgical services. CMS is allowed to withhold 5% of the surgical payment until the sample information is reported at the end of the global period.

While MACRA does not implement broad medical liability reforms, it does include a provision which assures that MIPS participation cannot be used in a medical liability action. Specifically, the legislation specifies that the development, recognition or implementation of any guideline or other standard under any federal health care provision, including Medicare, cannot be construed as to establish the standard of care or duty of care owed by a surgeon to a patient in any medical malpractice claim.

Finally, and of particular interest to pediatric surgeons and other surgeons who care for children, MACRA includes two years of additional funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at the level provided under the Affordable Care Act.

Unfortunately, surgeons will need to become familiar with an entire new lexicon of acronyms associated with this new law and its policy. While this may initially seem daunting and confusing, it can be mastered with relative ease. It is my hope to continue to facilitate such with the content provided herein with the June edition of this column.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

Lessons from our dying patients

Dying patients teach us to think more carefully about whether or not our surgical interventions will be beneficial.

I work in palliative care, and my surgical colleagues, especially the residents, are often surprised when I call them and ask them to consult on my patients who are very ill and have a “Do Not Resuscitate” order in their charts. I’m also an anesthesiologist working in interventional pain management, and I regularly do procedures on patients who have prognoses that are extremely limited. For other patients, I recommend against any interventions at all.

How do we know when to intervene on patients who are dying? Perhaps more importantly, how do we know when NOT to intervene? Two recent cases of almost identical fractures illustrated for me the need to think beyond the anatomic problem when evaluating options for care.

Last year, I admitted a woman, “Donna,” with widely metastatic breast cancer to our inpatient palliative care service. She had fallen at home and hurt her arm about 2 months prior to admission. She had been confined to her bed for about 6 weeks. She was brought to the hospital because she was becoming delirious. She had many sources of pain that were relatively well controlled when she was lying down, but her worst pain was in her left arm. We found a fracture of her humerus. When her family learned that the fracture would not heal on its own because of the large metastasis there, they demanded surgery to fix it. Shortly thereafter, I re-admitted a patient, “Cindy,” with a very similar story. She also had widely metastatic breast cancer, and her pain had been very difficult to control. We had found a pain regimen that worked well for her on her previous admission, but she had fallen over her walker and broke her humerus after we had discharged her to a rehab facility. When I saw her back in the hospital, I told her that I thought she would need surgery to fix her arm. She was depressed by this setback, she was in pain again, and she told me that she would prefer not to have any intervention because she feared the additional pain that it would cause.

With Donna, we sat down with her and her family to hear what their hopes were for her care. They understood that she did not have further chemotherapy or radiation options for her cancer, but they thought if she got the surgery that at least she would be able to get out of bed and walk again. My colleague carefully explained that yes, he could fix the fracture and that this could mean that the pain in her left arm would improve. He went on to say, however, that he did not think that the surgery would allow her to walk again as she had not been able to walk for a few weeks after the injury. When the family heard that the surgery probably wouldn’t restore her mobility, they decided against the procedure. With Cindy, we had a very different conversation. She was not inclined to have the procedure, but I expressed my concern that she wouldn’t be able to walk again unless she had the procedure because she needed her arms to use her walker. Although she did not have any further chemotherapy or radiation options, her oncologist had told us that her prognosis could be several months. In this case, my surgical colleague explained that he could perform surgery for the fracture and that he thought that it would both help her pain and allow her to use her walker again. We recommended that she have the surgery given her hope to continue to live independently, as she had been, for as long as possible. She ultimately agreed to do so and was able to return home.

These two patients reminded me again of how important it is for us to understand what our patients’ hopes and expectations are for a procedure. It is very distressing for clinicians when desperate families want treatments that likely have little benefit. When patients have limited prognoses, aligning patient goals and procedure goals is especially important as the outcome of the procedure can define the patient’s remaining days.

Donna’s family demanded a surgery expecting a result that was very unlikely, and Cindy initially declined the same surgery that ultimately benefitted her greatly. Our job is to make and execute the medical recommendations that best fit with our patients’ goals and understanding. Sometimes this will mean performing procedures on patients who are extremely ill and have “Do Not Resuscitate” orders, and at other times, it will mean not doing procedures, even if a patient and family want them to be done.

Dr. Rickerson is an anesthesiologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Dying patients teach us to think more carefully about whether or not our surgical interventions will be beneficial.

I work in palliative care, and my surgical colleagues, especially the residents, are often surprised when I call them and ask them to consult on my patients who are very ill and have a “Do Not Resuscitate” order in their charts. I’m also an anesthesiologist working in interventional pain management, and I regularly do procedures on patients who have prognoses that are extremely limited. For other patients, I recommend against any interventions at all.

How do we know when to intervene on patients who are dying? Perhaps more importantly, how do we know when NOT to intervene? Two recent cases of almost identical fractures illustrated for me the need to think beyond the anatomic problem when evaluating options for care.

Last year, I admitted a woman, “Donna,” with widely metastatic breast cancer to our inpatient palliative care service. She had fallen at home and hurt her arm about 2 months prior to admission. She had been confined to her bed for about 6 weeks. She was brought to the hospital because she was becoming delirious. She had many sources of pain that were relatively well controlled when she was lying down, but her worst pain was in her left arm. We found a fracture of her humerus. When her family learned that the fracture would not heal on its own because of the large metastasis there, they demanded surgery to fix it. Shortly thereafter, I re-admitted a patient, “Cindy,” with a very similar story. She also had widely metastatic breast cancer, and her pain had been very difficult to control. We had found a pain regimen that worked well for her on her previous admission, but she had fallen over her walker and broke her humerus after we had discharged her to a rehab facility. When I saw her back in the hospital, I told her that I thought she would need surgery to fix her arm. She was depressed by this setback, she was in pain again, and she told me that she would prefer not to have any intervention because she feared the additional pain that it would cause.

With Donna, we sat down with her and her family to hear what their hopes were for her care. They understood that she did not have further chemotherapy or radiation options for her cancer, but they thought if she got the surgery that at least she would be able to get out of bed and walk again. My colleague carefully explained that yes, he could fix the fracture and that this could mean that the pain in her left arm would improve. He went on to say, however, that he did not think that the surgery would allow her to walk again as she had not been able to walk for a few weeks after the injury. When the family heard that the surgery probably wouldn’t restore her mobility, they decided against the procedure. With Cindy, we had a very different conversation. She was not inclined to have the procedure, but I expressed my concern that she wouldn’t be able to walk again unless she had the procedure because she needed her arms to use her walker. Although she did not have any further chemotherapy or radiation options, her oncologist had told us that her prognosis could be several months. In this case, my surgical colleague explained that he could perform surgery for the fracture and that he thought that it would both help her pain and allow her to use her walker again. We recommended that she have the surgery given her hope to continue to live independently, as she had been, for as long as possible. She ultimately agreed to do so and was able to return home.

These two patients reminded me again of how important it is for us to understand what our patients’ hopes and expectations are for a procedure. It is very distressing for clinicians when desperate families want treatments that likely have little benefit. When patients have limited prognoses, aligning patient goals and procedure goals is especially important as the outcome of the procedure can define the patient’s remaining days.

Donna’s family demanded a surgery expecting a result that was very unlikely, and Cindy initially declined the same surgery that ultimately benefitted her greatly. Our job is to make and execute the medical recommendations that best fit with our patients’ goals and understanding. Sometimes this will mean performing procedures on patients who are extremely ill and have “Do Not Resuscitate” orders, and at other times, it will mean not doing procedures, even if a patient and family want them to be done.

Dr. Rickerson is an anesthesiologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Dying patients teach us to think more carefully about whether or not our surgical interventions will be beneficial.

I work in palliative care, and my surgical colleagues, especially the residents, are often surprised when I call them and ask them to consult on my patients who are very ill and have a “Do Not Resuscitate” order in their charts. I’m also an anesthesiologist working in interventional pain management, and I regularly do procedures on patients who have prognoses that are extremely limited. For other patients, I recommend against any interventions at all.

How do we know when to intervene on patients who are dying? Perhaps more importantly, how do we know when NOT to intervene? Two recent cases of almost identical fractures illustrated for me the need to think beyond the anatomic problem when evaluating options for care.

Last year, I admitted a woman, “Donna,” with widely metastatic breast cancer to our inpatient palliative care service. She had fallen at home and hurt her arm about 2 months prior to admission. She had been confined to her bed for about 6 weeks. She was brought to the hospital because she was becoming delirious. She had many sources of pain that were relatively well controlled when she was lying down, but her worst pain was in her left arm. We found a fracture of her humerus. When her family learned that the fracture would not heal on its own because of the large metastasis there, they demanded surgery to fix it. Shortly thereafter, I re-admitted a patient, “Cindy,” with a very similar story. She also had widely metastatic breast cancer, and her pain had been very difficult to control. We had found a pain regimen that worked well for her on her previous admission, but she had fallen over her walker and broke her humerus after we had discharged her to a rehab facility. When I saw her back in the hospital, I told her that I thought she would need surgery to fix her arm. She was depressed by this setback, she was in pain again, and she told me that she would prefer not to have any intervention because she feared the additional pain that it would cause.

With Donna, we sat down with her and her family to hear what their hopes were for her care. They understood that she did not have further chemotherapy or radiation options for her cancer, but they thought if she got the surgery that at least she would be able to get out of bed and walk again. My colleague carefully explained that yes, he could fix the fracture and that this could mean that the pain in her left arm would improve. He went on to say, however, that he did not think that the surgery would allow her to walk again as she had not been able to walk for a few weeks after the injury. When the family heard that the surgery probably wouldn’t restore her mobility, they decided against the procedure. With Cindy, we had a very different conversation. She was not inclined to have the procedure, but I expressed my concern that she wouldn’t be able to walk again unless she had the procedure because she needed her arms to use her walker. Although she did not have any further chemotherapy or radiation options, her oncologist had told us that her prognosis could be several months. In this case, my surgical colleague explained that he could perform surgery for the fracture and that he thought that it would both help her pain and allow her to use her walker again. We recommended that she have the surgery given her hope to continue to live independently, as she had been, for as long as possible. She ultimately agreed to do so and was able to return home.

These two patients reminded me again of how important it is for us to understand what our patients’ hopes and expectations are for a procedure. It is very distressing for clinicians when desperate families want treatments that likely have little benefit. When patients have limited prognoses, aligning patient goals and procedure goals is especially important as the outcome of the procedure can define the patient’s remaining days.

Donna’s family demanded a surgery expecting a result that was very unlikely, and Cindy initially declined the same surgery that ultimately benefitted her greatly. Our job is to make and execute the medical recommendations that best fit with our patients’ goals and understanding. Sometimes this will mean performing procedures on patients who are extremely ill and have “Do Not Resuscitate” orders, and at other times, it will mean not doing procedures, even if a patient and family want them to be done.

Dr. Rickerson is an anesthesiologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Malaria vaccine proves partially protective

Photo by James Gathany

A new malaria vaccine candidate proved partially effective in adult males living in an area of low malaria transmission.

The T-cell vaccine consists of the recombinant viral vectors chimpanzee adenovirus 63 (ChAd63) and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), both encoding the multiple epitope string and thrombospondin-related adhesion protein (ME-TRAP), a fusion of protein fragments found on the surface of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

In what’s known as a prime-boost strategy, an initial dose of the vaccine “primes” the immune system by exposing it to the malaria antigen and is followed by a vaccine booster, which re-stimulates the immune system to further solidify immunity.

Caroline Ogwang, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute–Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya, and her colleagues described their trial of the vaccine in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers tested the vaccine in an area of low malaria transmission in Kenya. They enrolled 121 healthy adult men and randomized them to receive the malaria vaccine or a control rabies vaccine.

The subjects were also treated with antimalarial drugs to clear any previous infection and were closely monitored for 8 weeks for P falciparum infection.

The malaria vaccine appeared to be safe, prompting no serious adverse events. The most common local adverse event associated with both ChAd63 ME-TRAP and MVA ME-TRAP was mild to moderate pain that lasted from a few hours to 3 days.

Subjects also experienced various systemic adverse events of mild to moderate intensity that lasted from a few hours to 5 days. Other events were reported within 30 days of vaccination as well, but these were not considered vaccine-related.

As for efficacy, blood tests revealed that the vaccine activated a strong immune response from T cells. For at least 2 weeks after vaccination, the vaccine showed partial efficacy in protecting against malaria infection.

The vaccine reduced subjects’ risk of infection by 67% (P=0.002) during the 8-week monitoring period. And the researchers said T-cell responses to TRAP peptides 21 to 30 were significantly associated with protection (hazard ratio=0.24, P=0.016).

The team is continuing clinical testing of the vaccine, including possible combinations with other vaccination strategies to increase efficacy. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

A new malaria vaccine candidate proved partially effective in adult males living in an area of low malaria transmission.

The T-cell vaccine consists of the recombinant viral vectors chimpanzee adenovirus 63 (ChAd63) and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), both encoding the multiple epitope string and thrombospondin-related adhesion protein (ME-TRAP), a fusion of protein fragments found on the surface of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

In what’s known as a prime-boost strategy, an initial dose of the vaccine “primes” the immune system by exposing it to the malaria antigen and is followed by a vaccine booster, which re-stimulates the immune system to further solidify immunity.

Caroline Ogwang, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute–Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya, and her colleagues described their trial of the vaccine in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers tested the vaccine in an area of low malaria transmission in Kenya. They enrolled 121 healthy adult men and randomized them to receive the malaria vaccine or a control rabies vaccine.

The subjects were also treated with antimalarial drugs to clear any previous infection and were closely monitored for 8 weeks for P falciparum infection.

The malaria vaccine appeared to be safe, prompting no serious adverse events. The most common local adverse event associated with both ChAd63 ME-TRAP and MVA ME-TRAP was mild to moderate pain that lasted from a few hours to 3 days.

Subjects also experienced various systemic adverse events of mild to moderate intensity that lasted from a few hours to 5 days. Other events were reported within 30 days of vaccination as well, but these were not considered vaccine-related.

As for efficacy, blood tests revealed that the vaccine activated a strong immune response from T cells. For at least 2 weeks after vaccination, the vaccine showed partial efficacy in protecting against malaria infection.

The vaccine reduced subjects’ risk of infection by 67% (P=0.002) during the 8-week monitoring period. And the researchers said T-cell responses to TRAP peptides 21 to 30 were significantly associated with protection (hazard ratio=0.24, P=0.016).

The team is continuing clinical testing of the vaccine, including possible combinations with other vaccination strategies to increase efficacy. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

A new malaria vaccine candidate proved partially effective in adult males living in an area of low malaria transmission.

The T-cell vaccine consists of the recombinant viral vectors chimpanzee adenovirus 63 (ChAd63) and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), both encoding the multiple epitope string and thrombospondin-related adhesion protein (ME-TRAP), a fusion of protein fragments found on the surface of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

In what’s known as a prime-boost strategy, an initial dose of the vaccine “primes” the immune system by exposing it to the malaria antigen and is followed by a vaccine booster, which re-stimulates the immune system to further solidify immunity.

Caroline Ogwang, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute–Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya, and her colleagues described their trial of the vaccine in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers tested the vaccine in an area of low malaria transmission in Kenya. They enrolled 121 healthy adult men and randomized them to receive the malaria vaccine or a control rabies vaccine.

The subjects were also treated with antimalarial drugs to clear any previous infection and were closely monitored for 8 weeks for P falciparum infection.

The malaria vaccine appeared to be safe, prompting no serious adverse events. The most common local adverse event associated with both ChAd63 ME-TRAP and MVA ME-TRAP was mild to moderate pain that lasted from a few hours to 3 days.

Subjects also experienced various systemic adverse events of mild to moderate intensity that lasted from a few hours to 5 days. Other events were reported within 30 days of vaccination as well, but these were not considered vaccine-related.

As for efficacy, blood tests revealed that the vaccine activated a strong immune response from T cells. For at least 2 weeks after vaccination, the vaccine showed partial efficacy in protecting against malaria infection.

The vaccine reduced subjects’ risk of infection by 67% (P=0.002) during the 8-week monitoring period. And the researchers said T-cell responses to TRAP peptides 21 to 30 were significantly associated with protection (hazard ratio=0.24, P=0.016).

The team is continuing clinical testing of the vaccine, including possible combinations with other vaccination strategies to increase efficacy. ![]()

Protein linked to leukemia, breast cancer

Photo courtesy of

The Scripps Research Institute

Overexpression of the cyclin E protein may cause leukemia and breast cancer, according to research published in Current Biology.

The study suggested that overexpression of cyclin E slows down DNA replication and introduces potentially harmful oncogenic mutations when cells divide.

“Overexpression of cyclin E is one route to cancer,” said study author Steven Reed, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Dr Reed and his colleagues originally discovered cyclin E, and their previous studies showed that abnormally high levels of cyclin E are associated with chromosome instability, increasing the chances that a chromosome will acquire more mutations as it divides.

The researchers found that cyclin E is frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, and that overexpression is linked to a decreased survival rate for breast cancer patients.

However, until they conducted the current study, the team didn’t know exactly how cyclin E introduces chromosome instability and errors into DNA.

DNA ‘tug-of-war’

The researchers investigated the role of cyclin E by comparing normal human mammary cells with mammary cells forced to overexpress cyclin E at the same levels seen in some breast cancer cells.

They found that DNA replication took significantly longer in the cyclin E-deregulated cells. In fact, the cells seemed to enter the next stage of cell division before the DNA was even done replicating. A small number (n=16) of very specific regions on the chromosomes frequently failed to complete replication.

The researchers then screened the cyclin E-deregulated cells for errors later in the cell division process. And they found that chromosomes of the deregulated cells’ daughter cells stuck together in the spots where replication had not finished.

“You could see a tug-of-war going on,” Dr Reed said. “That would cause either the chromosome to tear or both chromosomes to go to one side.”

The researchers spotted abnormal DNA “bridges” tying daughter cells together, as well as cells in which chunks of chromosomes ripped away and floated nearby. After these abnormal divisions took place, a third of the cyclin E-deregulated cells showed DNA deletions at the previously identified regions where replication failed.

The link to cancers

Next, the researchers investigated how the genetic instability from DNA deletions in cyclin E-deregulated cells could contribute to cancer. Many of the sites with DNA deletions were areas in which DNA was already known to be fragile or difficult to replicate.

Using a database of tumor DNA sequences, the team found that 6 of the 16 DNA regions they had identified in their cell-based studies showed damage in breast tumors that could be directly linked to cyclin E overexpression.

In addition, an area commonly damaged in cyclin E-deregulated cells matched up with an area commonly rearranged in mixed-lineage leukemia, where cyclin E had already been shown to be a contributing factor.

One of the unanswered questions posed by this work is how cells are allowed to divide before all the chromosomes are completely replicated. It was believed that “checkpoints” exist to prevent this from happening.

Dr Reed thinks these unreplicated regions are small enough to bypass the cellular checkpoints and keep cells dividing and accumulating potentially harmful mutations.

His team’s next step is to sequence the entire genomes of cells that undergo damage from cyclin E overexpression to understand exactly how the deletions contribute to cancer. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

The Scripps Research Institute

Overexpression of the cyclin E protein may cause leukemia and breast cancer, according to research published in Current Biology.

The study suggested that overexpression of cyclin E slows down DNA replication and introduces potentially harmful oncogenic mutations when cells divide.

“Overexpression of cyclin E is one route to cancer,” said study author Steven Reed, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Dr Reed and his colleagues originally discovered cyclin E, and their previous studies showed that abnormally high levels of cyclin E are associated with chromosome instability, increasing the chances that a chromosome will acquire more mutations as it divides.

The researchers found that cyclin E is frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, and that overexpression is linked to a decreased survival rate for breast cancer patients.

However, until they conducted the current study, the team didn’t know exactly how cyclin E introduces chromosome instability and errors into DNA.

DNA ‘tug-of-war’

The researchers investigated the role of cyclin E by comparing normal human mammary cells with mammary cells forced to overexpress cyclin E at the same levels seen in some breast cancer cells.

They found that DNA replication took significantly longer in the cyclin E-deregulated cells. In fact, the cells seemed to enter the next stage of cell division before the DNA was even done replicating. A small number (n=16) of very specific regions on the chromosomes frequently failed to complete replication.

The researchers then screened the cyclin E-deregulated cells for errors later in the cell division process. And they found that chromosomes of the deregulated cells’ daughter cells stuck together in the spots where replication had not finished.

“You could see a tug-of-war going on,” Dr Reed said. “That would cause either the chromosome to tear or both chromosomes to go to one side.”

The researchers spotted abnormal DNA “bridges” tying daughter cells together, as well as cells in which chunks of chromosomes ripped away and floated nearby. After these abnormal divisions took place, a third of the cyclin E-deregulated cells showed DNA deletions at the previously identified regions where replication failed.

The link to cancers

Next, the researchers investigated how the genetic instability from DNA deletions in cyclin E-deregulated cells could contribute to cancer. Many of the sites with DNA deletions were areas in which DNA was already known to be fragile or difficult to replicate.

Using a database of tumor DNA sequences, the team found that 6 of the 16 DNA regions they had identified in their cell-based studies showed damage in breast tumors that could be directly linked to cyclin E overexpression.

In addition, an area commonly damaged in cyclin E-deregulated cells matched up with an area commonly rearranged in mixed-lineage leukemia, where cyclin E had already been shown to be a contributing factor.

One of the unanswered questions posed by this work is how cells are allowed to divide before all the chromosomes are completely replicated. It was believed that “checkpoints” exist to prevent this from happening.

Dr Reed thinks these unreplicated regions are small enough to bypass the cellular checkpoints and keep cells dividing and accumulating potentially harmful mutations.

His team’s next step is to sequence the entire genomes of cells that undergo damage from cyclin E overexpression to understand exactly how the deletions contribute to cancer. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

The Scripps Research Institute

Overexpression of the cyclin E protein may cause leukemia and breast cancer, according to research published in Current Biology.

The study suggested that overexpression of cyclin E slows down DNA replication and introduces potentially harmful oncogenic mutations when cells divide.

“Overexpression of cyclin E is one route to cancer,” said study author Steven Reed, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Dr Reed and his colleagues originally discovered cyclin E, and their previous studies showed that abnormally high levels of cyclin E are associated with chromosome instability, increasing the chances that a chromosome will acquire more mutations as it divides.

The researchers found that cyclin E is frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, and that overexpression is linked to a decreased survival rate for breast cancer patients.

However, until they conducted the current study, the team didn’t know exactly how cyclin E introduces chromosome instability and errors into DNA.

DNA ‘tug-of-war’

The researchers investigated the role of cyclin E by comparing normal human mammary cells with mammary cells forced to overexpress cyclin E at the same levels seen in some breast cancer cells.

They found that DNA replication took significantly longer in the cyclin E-deregulated cells. In fact, the cells seemed to enter the next stage of cell division before the DNA was even done replicating. A small number (n=16) of very specific regions on the chromosomes frequently failed to complete replication.

The researchers then screened the cyclin E-deregulated cells for errors later in the cell division process. And they found that chromosomes of the deregulated cells’ daughter cells stuck together in the spots where replication had not finished.

“You could see a tug-of-war going on,” Dr Reed said. “That would cause either the chromosome to tear or both chromosomes to go to one side.”

The researchers spotted abnormal DNA “bridges” tying daughter cells together, as well as cells in which chunks of chromosomes ripped away and floated nearby. After these abnormal divisions took place, a third of the cyclin E-deregulated cells showed DNA deletions at the previously identified regions where replication failed.

The link to cancers

Next, the researchers investigated how the genetic instability from DNA deletions in cyclin E-deregulated cells could contribute to cancer. Many of the sites with DNA deletions were areas in which DNA was already known to be fragile or difficult to replicate.

Using a database of tumor DNA sequences, the team found that 6 of the 16 DNA regions they had identified in their cell-based studies showed damage in breast tumors that could be directly linked to cyclin E overexpression.

In addition, an area commonly damaged in cyclin E-deregulated cells matched up with an area commonly rearranged in mixed-lineage leukemia, where cyclin E had already been shown to be a contributing factor.

One of the unanswered questions posed by this work is how cells are allowed to divide before all the chromosomes are completely replicated. It was believed that “checkpoints” exist to prevent this from happening.

Dr Reed thinks these unreplicated regions are small enough to bypass the cellular checkpoints and keep cells dividing and accumulating potentially harmful mutations.

His team’s next step is to sequence the entire genomes of cells that undergo damage from cyclin E overexpression to understand exactly how the deletions contribute to cancer. ![]()

GIST patients have higher risk of NHL, other cancers

Photo courtesy of CDC

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) have an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and other cancers, a new study suggests.

About 1 in 6 of the patients studied were diagnosed with an additional malignancy.

The patients had an increased risk of other sarcomas, NHL, carcinoid tumors, melanoma, and colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, non-small cell lung, prostate, and renal cell cancers.

“Only 5% of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a hereditary disorder that predisposes them to develop multiple benign and malignant tumors,” said study author Jason K. Sicklick, MD, of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

“The research indicates that these patients may develop cancers outside of these syndromes, but the exact mechanisms are not yet known.”

Dr Sicklick and his colleagues described their research in Cancer.

The team analyzed 6112 GIST patients and found that 1047 of them (17.1%) had additional cancers.

When compared to the general US population, patients had a 44% increased prevalence of cancers occurring before a GIST diagnosis and a 66% higher risk of developing cancers after GIST diagnosis.

That corresponds to a standardized prevalence ratio (SPR) of 1.44 (risk before GIST diagnosis) and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.66 (risk after GIST diagnosis).

Both before and after GIST diagnosis, patients had a significantly increased risk of NHL (SPR=1.69, SIR=1.76), other sarcomas (SPR=5.24, SIR=4.02), neuroendocrine-carcinoid tumors (SPR=3.56, SIR=4.79), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.51, SIR=2.16).

Before GIST diagnosis, patients had an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (SPR=12.0), bladder adenocarcinoma (SPR=7.51), melanoma (SPR=1.46), and prostate adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.20).

And after GIST diagnosis, they had an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma (SIR=8.72), small intestine adenocarcinoma (SIR=5.89), papillary thyroid cancer (SIR=5.16), renal cell carcinoma (SIR=4.46), hepatobiliary adenocarcinoma (SIR=3.10), gastric adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.70), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.03), uterine adenocarcinoma (SIR=1.96), non-small cell lung cancer (SIR=1.74), and transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (SIR=1.65).

The researchers said further studies are needed to understand the connection between GIST and other cancers, but these findings may have clinical implications.

“Patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumors may warrant consideration for additional screenings based on the other cancers that they are most susceptible to contract,” said James D. Murphy, MD, also of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) have an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and other cancers, a new study suggests.

About 1 in 6 of the patients studied were diagnosed with an additional malignancy.

The patients had an increased risk of other sarcomas, NHL, carcinoid tumors, melanoma, and colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, non-small cell lung, prostate, and renal cell cancers.

“Only 5% of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a hereditary disorder that predisposes them to develop multiple benign and malignant tumors,” said study author Jason K. Sicklick, MD, of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

“The research indicates that these patients may develop cancers outside of these syndromes, but the exact mechanisms are not yet known.”

Dr Sicklick and his colleagues described their research in Cancer.

The team analyzed 6112 GIST patients and found that 1047 of them (17.1%) had additional cancers.

When compared to the general US population, patients had a 44% increased prevalence of cancers occurring before a GIST diagnosis and a 66% higher risk of developing cancers after GIST diagnosis.

That corresponds to a standardized prevalence ratio (SPR) of 1.44 (risk before GIST diagnosis) and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.66 (risk after GIST diagnosis).

Both before and after GIST diagnosis, patients had a significantly increased risk of NHL (SPR=1.69, SIR=1.76), other sarcomas (SPR=5.24, SIR=4.02), neuroendocrine-carcinoid tumors (SPR=3.56, SIR=4.79), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.51, SIR=2.16).

Before GIST diagnosis, patients had an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (SPR=12.0), bladder adenocarcinoma (SPR=7.51), melanoma (SPR=1.46), and prostate adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.20).

And after GIST diagnosis, they had an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma (SIR=8.72), small intestine adenocarcinoma (SIR=5.89), papillary thyroid cancer (SIR=5.16), renal cell carcinoma (SIR=4.46), hepatobiliary adenocarcinoma (SIR=3.10), gastric adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.70), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.03), uterine adenocarcinoma (SIR=1.96), non-small cell lung cancer (SIR=1.74), and transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (SIR=1.65).

The researchers said further studies are needed to understand the connection between GIST and other cancers, but these findings may have clinical implications.

“Patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumors may warrant consideration for additional screenings based on the other cancers that they are most susceptible to contract,” said James D. Murphy, MD, also of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) have an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and other cancers, a new study suggests.

About 1 in 6 of the patients studied were diagnosed with an additional malignancy.

The patients had an increased risk of other sarcomas, NHL, carcinoid tumors, melanoma, and colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, non-small cell lung, prostate, and renal cell cancers.

“Only 5% of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a hereditary disorder that predisposes them to develop multiple benign and malignant tumors,” said study author Jason K. Sicklick, MD, of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

“The research indicates that these patients may develop cancers outside of these syndromes, but the exact mechanisms are not yet known.”

Dr Sicklick and his colleagues described their research in Cancer.

The team analyzed 6112 GIST patients and found that 1047 of them (17.1%) had additional cancers.

When compared to the general US population, patients had a 44% increased prevalence of cancers occurring before a GIST diagnosis and a 66% higher risk of developing cancers after GIST diagnosis.

That corresponds to a standardized prevalence ratio (SPR) of 1.44 (risk before GIST diagnosis) and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.66 (risk after GIST diagnosis).

Both before and after GIST diagnosis, patients had a significantly increased risk of NHL (SPR=1.69, SIR=1.76), other sarcomas (SPR=5.24, SIR=4.02), neuroendocrine-carcinoid tumors (SPR=3.56, SIR=4.79), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.51, SIR=2.16).

Before GIST diagnosis, patients had an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (SPR=12.0), bladder adenocarcinoma (SPR=7.51), melanoma (SPR=1.46), and prostate adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.20).

And after GIST diagnosis, they had an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma (SIR=8.72), small intestine adenocarcinoma (SIR=5.89), papillary thyroid cancer (SIR=5.16), renal cell carcinoma (SIR=4.46), hepatobiliary adenocarcinoma (SIR=3.10), gastric adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.70), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.03), uterine adenocarcinoma (SIR=1.96), non-small cell lung cancer (SIR=1.74), and transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (SIR=1.65).

The researchers said further studies are needed to understand the connection between GIST and other cancers, but these findings may have clinical implications.

“Patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumors may warrant consideration for additional screenings based on the other cancers that they are most susceptible to contract,” said James D. Murphy, MD, also of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center. ![]()

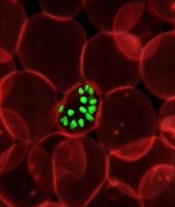

Study reveals ‘doorway’ into RBCs

infecting an RBC

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A protein on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs) serves as an essential entry point for malaria parasite invasion, according to researchers.

They found the presence of this protein, CD55, was critical to the Plasmodium falciparum parasite’s ability to attach itself to the RBC surface.

The team believes this discovery, published in Science, opens up a promising new avenue for developing therapies to treat and prevent malaria.

“Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites have evolved several key-like molecules to enter into human red blood cells through different door-like host receptors,” said study author Manoj Duraisingh, PhD, of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Hence, if one red blood cell door is blocked, the parasite finds another way to enter. We have now identified an essential host factor which, when removed, prevents all parasite strains from entering red blood cells.”

The researchers accomplished this by developing a new technique to tap into a relatively unexplored area: identifying characteristics of a host RBC that make it susceptible to parasites. RBCs are difficult targets for such efforts as they lack a nucleus, which makes genetic manipulation impossible.

So the team transformed stem cells into RBCs, which allowed them to conduct a genetic screen for host determinants of P falciparum infection. They found that malaria parasites failed to attach properly to the surface of RBCs that lacked CD55.

The protein was required for invasion in all tested strains of the parasite, including those developed in a lab and those isolated from patients. This makes CD55 a primary candidate for intervention, the researchers said.

“The discovery of CD55 as an essential host factor for P falciparum raises the intriguing possibility of host-directed therapeutics for malaria, as is used in HIV,” said study author Elizabeth Egan, MD, PhD, also of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

“CD55 also gives us a hook with which to search for new parasite proteins important for invasion, which could serve as vaccine targets.” ![]()

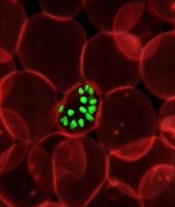

infecting an RBC

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A protein on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs) serves as an essential entry point for malaria parasite invasion, according to researchers.

They found the presence of this protein, CD55, was critical to the Plasmodium falciparum parasite’s ability to attach itself to the RBC surface.

The team believes this discovery, published in Science, opens up a promising new avenue for developing therapies to treat and prevent malaria.

“Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites have evolved several key-like molecules to enter into human red blood cells through different door-like host receptors,” said study author Manoj Duraisingh, PhD, of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Hence, if one red blood cell door is blocked, the parasite finds another way to enter. We have now identified an essential host factor which, when removed, prevents all parasite strains from entering red blood cells.”

The researchers accomplished this by developing a new technique to tap into a relatively unexplored area: identifying characteristics of a host RBC that make it susceptible to parasites. RBCs are difficult targets for such efforts as they lack a nucleus, which makes genetic manipulation impossible.

So the team transformed stem cells into RBCs, which allowed them to conduct a genetic screen for host determinants of P falciparum infection. They found that malaria parasites failed to attach properly to the surface of RBCs that lacked CD55.

The protein was required for invasion in all tested strains of the parasite, including those developed in a lab and those isolated from patients. This makes CD55 a primary candidate for intervention, the researchers said.

“The discovery of CD55 as an essential host factor for P falciparum raises the intriguing possibility of host-directed therapeutics for malaria, as is used in HIV,” said study author Elizabeth Egan, MD, PhD, also of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

“CD55 also gives us a hook with which to search for new parasite proteins important for invasion, which could serve as vaccine targets.” ![]()

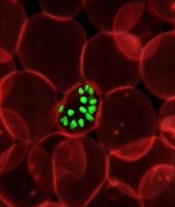

infecting an RBC

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A protein on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs) serves as an essential entry point for malaria parasite invasion, according to researchers.

They found the presence of this protein, CD55, was critical to the Plasmodium falciparum parasite’s ability to attach itself to the RBC surface.

The team believes this discovery, published in Science, opens up a promising new avenue for developing therapies to treat and prevent malaria.

“Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites have evolved several key-like molecules to enter into human red blood cells through different door-like host receptors,” said study author Manoj Duraisingh, PhD, of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Hence, if one red blood cell door is blocked, the parasite finds another way to enter. We have now identified an essential host factor which, when removed, prevents all parasite strains from entering red blood cells.”

The researchers accomplished this by developing a new technique to tap into a relatively unexplored area: identifying characteristics of a host RBC that make it susceptible to parasites. RBCs are difficult targets for such efforts as they lack a nucleus, which makes genetic manipulation impossible.

So the team transformed stem cells into RBCs, which allowed them to conduct a genetic screen for host determinants of P falciparum infection. They found that malaria parasites failed to attach properly to the surface of RBCs that lacked CD55.

The protein was required for invasion in all tested strains of the parasite, including those developed in a lab and those isolated from patients. This makes CD55 a primary candidate for intervention, the researchers said.

“The discovery of CD55 as an essential host factor for P falciparum raises the intriguing possibility of host-directed therapeutics for malaria, as is used in HIV,” said study author Elizabeth Egan, MD, PhD, also of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

“CD55 also gives us a hook with which to search for new parasite proteins important for invasion, which could serve as vaccine targets.” ![]()

Fear of “Contagion” Keeps Man’s Girlfriend Away

A 25-year-old man presents to dermatology with a “yeast infection” at the corners of his mouth that has failed to respond to anti-yeast creams (nystatin, clotrimazole) and oral medications (fluconazole). He has also tried a variety of “home remedies,” including hydrogen peroxide, rubbing alcohol, mouthwash, diaper cream, triple-antibiotic ointment, and tea tree oil. If anything, these seemed to worsen the problem.

He is fairly sure the problem developed because, several weeks ago, he shaved too close in the affected area. Soon after, he went to the dentist, who suggested the problem might be caused by a vitamin deficiency—but several weeks of taking a multivitamin produced no discernable result.

The affected area is irritated and sometimes painful, and he has a hard time leaving it alone. Several times a day, despite knowing how counterproductive it is, he finds himself picking at it. But worst of all, to the patient, is the fact that his girlfriend refuses to let him near her, citing fears of contagion.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise, although his history includes seasonal allergies and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The corners of the patient’s mouth are quite macerated, eroded, and focally scaly, with modest erythema. There is no edema or tenderness on palpation. Examination of the inside of his mouth is within normal limits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical clinical and historical snapshot of a very common problem: angular stomatitis (AS), also known as perleche or angular cheilitis (among others). A rather simple problem, it nonetheless causes confusion in primary care settings.

Virtually every AS patient I’ve seen was referred to dermatology after trying at least half a dozen different treatments. These attempts rarely work—and even if one of them did, the average AS patient wouldn’t realize it, because he’s almost always using several medications simultaneously.

AS, in its usual form, is not a complex problem. Thin tissue at the corner of the mouth is traumatized (shaving is one method, but another is holding the mouth open for two hours while at the dentist), and then the patient often picks at the resulting scale, making it worse. During sleep, saliva may flow onto the affected area, causing maceration and further damaging already irritated skin. The saliva introduces a multitude of bacteria, yeast, and other micro-organisms to this damaged tissue, further contributing to the inflammation.

At this point, some patients will panic, compounding the problem by throwing anything and everything they can think of at it: lip balm, peroxide, alcohol, triple-antibiotic ointment. If they seek professional help, they are often given a prescription for an oral anti-yeast medication (eg, fluconazole). Seldom does this help, and for a very good reason: Even though Candida is almost always present in and around the mouth—and may well contribute to the problem—only rarely is the issue a “yeast infection.” In the rare instances I’ve seen this, the patient was immunosuppressed.

In its simplest and most common form, AS is a form of intertrigo, in which inflammation is perpetuated by moist skin on skin—in this case, by the little channel created by the labial commissures. We see essentially the same thing under the breasts, in the axillae, in the folds of the abdomen, and in the groin. These manifestations are almost always diagnosed as “yeast infection,” even though treatment for such usually fails.

Patients who might find themselves particularly susceptible to AS include those with poorly fitting dentures, which allow overclosure of the mouth, accentuating the labial folds; those with atopy, whose skin is already thin and easily irritated; and those with seasonal allergies, who mouth-breathe while sleeping, drying out their lips while drooling from the corners of the mouth. Select patients may have true vitamin or mineral deficiencies (eg, zinc) due to poor dietary intake.

The majority of AS patients respond quite well to a combination of a topical imidazole cream or ointment (eg, miconazole or oxiconazole) and a mid-strength topical steroid ointment (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), mixed half and half by hand and applied twice a day. The patient must be persuaded to stop using all other contactants, since these often perpetuate the problem. Once the condition is under control (usually within a week), the application of petroleum jelly will help to prevent recurrences.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Angular stomatitis (AS) typically represents inflammation of thin, sensitive lip skin; the irritation is perpetuated by saliva, which causes maceration and makes the tissue vulnerable to the normal flora present in every human mouth.

• Though AS is not an infection, it can be worsened by micro-organisms, especially yeast—but monotherapy with anti-yeast medication almost always fails.

• Effective treatment must address the inflammation, via the application of a topical steroid and cessation of all other topical treatments in case they’re contributory.

• Prevention of recurrences may require the patient to address a chronic dental problem, or the provider to rule out less typical causes (eg, dietary deficiencies).

A 25-year-old man presents to dermatology with a “yeast infection” at the corners of his mouth that has failed to respond to anti-yeast creams (nystatin, clotrimazole) and oral medications (fluconazole). He has also tried a variety of “home remedies,” including hydrogen peroxide, rubbing alcohol, mouthwash, diaper cream, triple-antibiotic ointment, and tea tree oil. If anything, these seemed to worsen the problem.

He is fairly sure the problem developed because, several weeks ago, he shaved too close in the affected area. Soon after, he went to the dentist, who suggested the problem might be caused by a vitamin deficiency—but several weeks of taking a multivitamin produced no discernable result.

The affected area is irritated and sometimes painful, and he has a hard time leaving it alone. Several times a day, despite knowing how counterproductive it is, he finds himself picking at it. But worst of all, to the patient, is the fact that his girlfriend refuses to let him near her, citing fears of contagion.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise, although his history includes seasonal allergies and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The corners of the patient’s mouth are quite macerated, eroded, and focally scaly, with modest erythema. There is no edema or tenderness on palpation. Examination of the inside of his mouth is within normal limits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical clinical and historical snapshot of a very common problem: angular stomatitis (AS), also known as perleche or angular cheilitis (among others). A rather simple problem, it nonetheless causes confusion in primary care settings.

Virtually every AS patient I’ve seen was referred to dermatology after trying at least half a dozen different treatments. These attempts rarely work—and even if one of them did, the average AS patient wouldn’t realize it, because he’s almost always using several medications simultaneously.

AS, in its usual form, is not a complex problem. Thin tissue at the corner of the mouth is traumatized (shaving is one method, but another is holding the mouth open for two hours while at the dentist), and then the patient often picks at the resulting scale, making it worse. During sleep, saliva may flow onto the affected area, causing maceration and further damaging already irritated skin. The saliva introduces a multitude of bacteria, yeast, and other micro-organisms to this damaged tissue, further contributing to the inflammation.

At this point, some patients will panic, compounding the problem by throwing anything and everything they can think of at it: lip balm, peroxide, alcohol, triple-antibiotic ointment. If they seek professional help, they are often given a prescription for an oral anti-yeast medication (eg, fluconazole). Seldom does this help, and for a very good reason: Even though Candida is almost always present in and around the mouth—and may well contribute to the problem—only rarely is the issue a “yeast infection.” In the rare instances I’ve seen this, the patient was immunosuppressed.

In its simplest and most common form, AS is a form of intertrigo, in which inflammation is perpetuated by moist skin on skin—in this case, by the little channel created by the labial commissures. We see essentially the same thing under the breasts, in the axillae, in the folds of the abdomen, and in the groin. These manifestations are almost always diagnosed as “yeast infection,” even though treatment for such usually fails.

Patients who might find themselves particularly susceptible to AS include those with poorly fitting dentures, which allow overclosure of the mouth, accentuating the labial folds; those with atopy, whose skin is already thin and easily irritated; and those with seasonal allergies, who mouth-breathe while sleeping, drying out their lips while drooling from the corners of the mouth. Select patients may have true vitamin or mineral deficiencies (eg, zinc) due to poor dietary intake.

The majority of AS patients respond quite well to a combination of a topical imidazole cream or ointment (eg, miconazole or oxiconazole) and a mid-strength topical steroid ointment (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), mixed half and half by hand and applied twice a day. The patient must be persuaded to stop using all other contactants, since these often perpetuate the problem. Once the condition is under control (usually within a week), the application of petroleum jelly will help to prevent recurrences.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Angular stomatitis (AS) typically represents inflammation of thin, sensitive lip skin; the irritation is perpetuated by saliva, which causes maceration and makes the tissue vulnerable to the normal flora present in every human mouth.

• Though AS is not an infection, it can be worsened by micro-organisms, especially yeast—but monotherapy with anti-yeast medication almost always fails.

• Effective treatment must address the inflammation, via the application of a topical steroid and cessation of all other topical treatments in case they’re contributory.

• Prevention of recurrences may require the patient to address a chronic dental problem, or the provider to rule out less typical causes (eg, dietary deficiencies).

A 25-year-old man presents to dermatology with a “yeast infection” at the corners of his mouth that has failed to respond to anti-yeast creams (nystatin, clotrimazole) and oral medications (fluconazole). He has also tried a variety of “home remedies,” including hydrogen peroxide, rubbing alcohol, mouthwash, diaper cream, triple-antibiotic ointment, and tea tree oil. If anything, these seemed to worsen the problem.

He is fairly sure the problem developed because, several weeks ago, he shaved too close in the affected area. Soon after, he went to the dentist, who suggested the problem might be caused by a vitamin deficiency—but several weeks of taking a multivitamin produced no discernable result.

The affected area is irritated and sometimes painful, and he has a hard time leaving it alone. Several times a day, despite knowing how counterproductive it is, he finds himself picking at it. But worst of all, to the patient, is the fact that his girlfriend refuses to let him near her, citing fears of contagion.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise, although his history includes seasonal allergies and eczema.

EXAMINATION

The corners of the patient’s mouth are quite macerated, eroded, and focally scaly, with modest erythema. There is no edema or tenderness on palpation. Examination of the inside of his mouth is within normal limits.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical clinical and historical snapshot of a very common problem: angular stomatitis (AS), also known as perleche or angular cheilitis (among others). A rather simple problem, it nonetheless causes confusion in primary care settings.

Virtually every AS patient I’ve seen was referred to dermatology after trying at least half a dozen different treatments. These attempts rarely work—and even if one of them did, the average AS patient wouldn’t realize it, because he’s almost always using several medications simultaneously.

AS, in its usual form, is not a complex problem. Thin tissue at the corner of the mouth is traumatized (shaving is one method, but another is holding the mouth open for two hours while at the dentist), and then the patient often picks at the resulting scale, making it worse. During sleep, saliva may flow onto the affected area, causing maceration and further damaging already irritated skin. The saliva introduces a multitude of bacteria, yeast, and other micro-organisms to this damaged tissue, further contributing to the inflammation.

At this point, some patients will panic, compounding the problem by throwing anything and everything they can think of at it: lip balm, peroxide, alcohol, triple-antibiotic ointment. If they seek professional help, they are often given a prescription for an oral anti-yeast medication (eg, fluconazole). Seldom does this help, and for a very good reason: Even though Candida is almost always present in and around the mouth—and may well contribute to the problem—only rarely is the issue a “yeast infection.” In the rare instances I’ve seen this, the patient was immunosuppressed.

In its simplest and most common form, AS is a form of intertrigo, in which inflammation is perpetuated by moist skin on skin—in this case, by the little channel created by the labial commissures. We see essentially the same thing under the breasts, in the axillae, in the folds of the abdomen, and in the groin. These manifestations are almost always diagnosed as “yeast infection,” even though treatment for such usually fails.

Patients who might find themselves particularly susceptible to AS include those with poorly fitting dentures, which allow overclosure of the mouth, accentuating the labial folds; those with atopy, whose skin is already thin and easily irritated; and those with seasonal allergies, who mouth-breathe while sleeping, drying out their lips while drooling from the corners of the mouth. Select patients may have true vitamin or mineral deficiencies (eg, zinc) due to poor dietary intake.

The majority of AS patients respond quite well to a combination of a topical imidazole cream or ointment (eg, miconazole or oxiconazole) and a mid-strength topical steroid ointment (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), mixed half and half by hand and applied twice a day. The patient must be persuaded to stop using all other contactants, since these often perpetuate the problem. Once the condition is under control (usually within a week), the application of petroleum jelly will help to prevent recurrences.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Angular stomatitis (AS) typically represents inflammation of thin, sensitive lip skin; the irritation is perpetuated by saliva, which causes maceration and makes the tissue vulnerable to the normal flora present in every human mouth.

• Though AS is not an infection, it can be worsened by micro-organisms, especially yeast—but monotherapy with anti-yeast medication almost always fails.

• Effective treatment must address the inflammation, via the application of a topical steroid and cessation of all other topical treatments in case they’re contributory.