User login

OCD undertreatment: Is Internet-based CBT the answer?

VIENNA – Christian Rück, MD, believes he has seen the future of treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it’s Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The numbers tell the tale. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 2% of the general population. It’s an often disabling condition marked by shame and stigma. Major practice guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as the evidence-based first-line nonpharmacologic therapy. Yet only 5%-10% of OCD patients ever receive conventional face-to-face CBT because of the severe shortage and geographic maldistribution of therapists trained in its use, the psychiatrist observed at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Thus, a huge unmet need exists for treatment access. And persuasive evidence now exists that Internet-based CBT (I-CBT) for OCD can be provided effectively, safely, and in an extremely cost-effective fashion. Indeed, it takes up very little therapist time – an average of 6-10 minutes per patient per week devoted to reading and answering participants’ emails. And since the therapist’s main role in this treatment approach is simply to encourage patient engagement in the structured online program, I-CBT readily lends itself to use by primary care physicians and other nonspecialists, according to Dr. Rück, a psychiatrist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

“The vast majority of OCD patients have access to nothing. To me, I-CBT provides us with a unique opportunity to sustain quality of care but still make it very widely available. It’s sort of like serving a top-notch lobster meal at McDonald’s prices,” he said.

Over the past 15 years, I-CBT programs have been developed and proven effective in more than 150 randomized controlled trials for a wide range of psychiatric and medical conditions, including depression, panic disorder, social phobia, severe health anxiety and other anxiety disorders, erectile dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and insomnia.

More recently, Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators have pioneered the development of I-CBT as an evidence-based treatment for OCD. They now are in the process of doing the same for body dysmorphic disorder, a related condition that’s often particularly challenging to treat successfully.

The investigators’ first large randomized controlled trial of I-CBT for OCD included 101 patients with a mean 18-year history of the disorder. They were assigned to 10 weeks of the online therapy or to an online supportive care control arm. Mean scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) improved from 21.4 at baseline to 12.9 upon completion of the I-CBT program and 12.6 at follow-up 4 months post treatment. Sixty percent of the I-CBT group demonstrated clinically significant improvement, compared with 6% of controls (Psychol Med. 2012 Oct;42[10]:2193-203).

The benefit proved durable, as demonstrated in an extension study with periodic follow-up out to 24 months post completion of the I-CBT program. The incorporation of an Internet-based booster program in one arm of the follow-up protocol protected against relapses (Psychol Med. 2014 Oct;44[13]2877-87).

Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators also have shown in a 128-patient, double-blind trial that d-cycloserine, a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate agonist that promotes fear extinction, augmented the response to I-CBT for OCD, but only in the subgroup not on concomitant antidepressant therapy. The remission rate was 60% at 3 months follow-up post I-CBT in antidepressant-free patients on d-cycloserine, compared with just 24% in d-cycloserine recipients taking antidepressants during I-CBT. Apparently, antidepressants blunt d-cycloserine’s fear-extinction effect (JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;72[7]:659-67).

The program content of I-CBT is the same as in conventional manualized CBT, but without the face-to-face contact. The I-CBT program consists of 10-15 weekly chapters or modules. There is homework, worksheets, and titrated exposures to fear-eliciting situations. Progress to the next module is contingent upon completion of the previous one, with the patient being required to successfully answer questions that show mastery of the material.

Most patients rate the program favorably. They like not having to show up in the therapist’s office week after week.

“One of the advantages of I-CBT is you can interact every day. If your exposure goes wrong you don’t have to wait 6 days until your next face-to-face appointment with your therapist; you can actually get treatment right away and in that way increase the speed of progress,” Dr. Rück observed.

Also, if the patient forgets a basic concept, he or she can go back and reread.

“Everything is saved. This makes it very easy to supervise. There’s nothing going on that can’t be seen. Isaac M. Marks, MD, an early OCD researcher at Imperial College London, once said that one of the greatest advantages of I-CBT is that the therapist can’t sleep with the patient,” Dr. Rück recalled.

His research group is now in the midst of a clinical trial designed to answer two key questions: Is I-CBT for OCD as effective as face-to-face CBT? And is the therapist really necessary in order to achieve optimal outcomes in I-CBT?

“It would be a kind of shock to us if all our therapist impact is for nothing, but we’ll find out soon,” he promised.

Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators recently developed a program for therapist-supervised I-CBT for patients with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). In a single-blind pilot clinical trial involving 94 adults with BDD, the clinical response rate at 6 months of follow-up as defined by at least a 30% reduction from baseline in scores on the BDD–Y-BOCS was 56% in the I-CBT arm and 13% in controls assigned to online supportive care. The number needed to treat was impressively low, at 2.3. And those results were achieved by clinical psychology students having no prior experience with BDD, although they were closely supervised by an experienced clinician (BMJ. 2016 Feb 2;352:i241.

Dr. Rück has been disappointed to find that physicians, psychotherapists, and health care systems have been slow to embrace I-CBT for the conditions where there is solid supportive randomized trial evidence. I-CBT has been implemented within health care systems only in Australia and Stockholm County, the places where most of the research has been conducted.

“The literature has been around for about 15 years now, and we are noticing that the rollout of this is terribly slow. I’m starting to think that the health care system itself is one of the most problematic roadblocks, especially with regard to reimbursement issues. Maybe I-CBT should be offered outside of the health care system. Sometimes I think Google would do this better than a nationalized health care system,” the psychiatrist mused.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

VIENNA – Christian Rück, MD, believes he has seen the future of treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it’s Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The numbers tell the tale. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 2% of the general population. It’s an often disabling condition marked by shame and stigma. Major practice guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as the evidence-based first-line nonpharmacologic therapy. Yet only 5%-10% of OCD patients ever receive conventional face-to-face CBT because of the severe shortage and geographic maldistribution of therapists trained in its use, the psychiatrist observed at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Thus, a huge unmet need exists for treatment access. And persuasive evidence now exists that Internet-based CBT (I-CBT) for OCD can be provided effectively, safely, and in an extremely cost-effective fashion. Indeed, it takes up very little therapist time – an average of 6-10 minutes per patient per week devoted to reading and answering participants’ emails. And since the therapist’s main role in this treatment approach is simply to encourage patient engagement in the structured online program, I-CBT readily lends itself to use by primary care physicians and other nonspecialists, according to Dr. Rück, a psychiatrist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

“The vast majority of OCD patients have access to nothing. To me, I-CBT provides us with a unique opportunity to sustain quality of care but still make it very widely available. It’s sort of like serving a top-notch lobster meal at McDonald’s prices,” he said.

Over the past 15 years, I-CBT programs have been developed and proven effective in more than 150 randomized controlled trials for a wide range of psychiatric and medical conditions, including depression, panic disorder, social phobia, severe health anxiety and other anxiety disorders, erectile dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and insomnia.

More recently, Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators have pioneered the development of I-CBT as an evidence-based treatment for OCD. They now are in the process of doing the same for body dysmorphic disorder, a related condition that’s often particularly challenging to treat successfully.

The investigators’ first large randomized controlled trial of I-CBT for OCD included 101 patients with a mean 18-year history of the disorder. They were assigned to 10 weeks of the online therapy or to an online supportive care control arm. Mean scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) improved from 21.4 at baseline to 12.9 upon completion of the I-CBT program and 12.6 at follow-up 4 months post treatment. Sixty percent of the I-CBT group demonstrated clinically significant improvement, compared with 6% of controls (Psychol Med. 2012 Oct;42[10]:2193-203).

The benefit proved durable, as demonstrated in an extension study with periodic follow-up out to 24 months post completion of the I-CBT program. The incorporation of an Internet-based booster program in one arm of the follow-up protocol protected against relapses (Psychol Med. 2014 Oct;44[13]2877-87).

Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators also have shown in a 128-patient, double-blind trial that d-cycloserine, a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate agonist that promotes fear extinction, augmented the response to I-CBT for OCD, but only in the subgroup not on concomitant antidepressant therapy. The remission rate was 60% at 3 months follow-up post I-CBT in antidepressant-free patients on d-cycloserine, compared with just 24% in d-cycloserine recipients taking antidepressants during I-CBT. Apparently, antidepressants blunt d-cycloserine’s fear-extinction effect (JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;72[7]:659-67).

The program content of I-CBT is the same as in conventional manualized CBT, but without the face-to-face contact. The I-CBT program consists of 10-15 weekly chapters or modules. There is homework, worksheets, and titrated exposures to fear-eliciting situations. Progress to the next module is contingent upon completion of the previous one, with the patient being required to successfully answer questions that show mastery of the material.

Most patients rate the program favorably. They like not having to show up in the therapist’s office week after week.

“One of the advantages of I-CBT is you can interact every day. If your exposure goes wrong you don’t have to wait 6 days until your next face-to-face appointment with your therapist; you can actually get treatment right away and in that way increase the speed of progress,” Dr. Rück observed.

Also, if the patient forgets a basic concept, he or she can go back and reread.

“Everything is saved. This makes it very easy to supervise. There’s nothing going on that can’t be seen. Isaac M. Marks, MD, an early OCD researcher at Imperial College London, once said that one of the greatest advantages of I-CBT is that the therapist can’t sleep with the patient,” Dr. Rück recalled.

His research group is now in the midst of a clinical trial designed to answer two key questions: Is I-CBT for OCD as effective as face-to-face CBT? And is the therapist really necessary in order to achieve optimal outcomes in I-CBT?

“It would be a kind of shock to us if all our therapist impact is for nothing, but we’ll find out soon,” he promised.

Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators recently developed a program for therapist-supervised I-CBT for patients with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). In a single-blind pilot clinical trial involving 94 adults with BDD, the clinical response rate at 6 months of follow-up as defined by at least a 30% reduction from baseline in scores on the BDD–Y-BOCS was 56% in the I-CBT arm and 13% in controls assigned to online supportive care. The number needed to treat was impressively low, at 2.3. And those results were achieved by clinical psychology students having no prior experience with BDD, although they were closely supervised by an experienced clinician (BMJ. 2016 Feb 2;352:i241.

Dr. Rück has been disappointed to find that physicians, psychotherapists, and health care systems have been slow to embrace I-CBT for the conditions where there is solid supportive randomized trial evidence. I-CBT has been implemented within health care systems only in Australia and Stockholm County, the places where most of the research has been conducted.

“The literature has been around for about 15 years now, and we are noticing that the rollout of this is terribly slow. I’m starting to think that the health care system itself is one of the most problematic roadblocks, especially with regard to reimbursement issues. Maybe I-CBT should be offered outside of the health care system. Sometimes I think Google would do this better than a nationalized health care system,” the psychiatrist mused.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

VIENNA – Christian Rück, MD, believes he has seen the future of treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it’s Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The numbers tell the tale. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 2% of the general population. It’s an often disabling condition marked by shame and stigma. Major practice guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as the evidence-based first-line nonpharmacologic therapy. Yet only 5%-10% of OCD patients ever receive conventional face-to-face CBT because of the severe shortage and geographic maldistribution of therapists trained in its use, the psychiatrist observed at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Thus, a huge unmet need exists for treatment access. And persuasive evidence now exists that Internet-based CBT (I-CBT) for OCD can be provided effectively, safely, and in an extremely cost-effective fashion. Indeed, it takes up very little therapist time – an average of 6-10 minutes per patient per week devoted to reading and answering participants’ emails. And since the therapist’s main role in this treatment approach is simply to encourage patient engagement in the structured online program, I-CBT readily lends itself to use by primary care physicians and other nonspecialists, according to Dr. Rück, a psychiatrist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

“The vast majority of OCD patients have access to nothing. To me, I-CBT provides us with a unique opportunity to sustain quality of care but still make it very widely available. It’s sort of like serving a top-notch lobster meal at McDonald’s prices,” he said.

Over the past 15 years, I-CBT programs have been developed and proven effective in more than 150 randomized controlled trials for a wide range of psychiatric and medical conditions, including depression, panic disorder, social phobia, severe health anxiety and other anxiety disorders, erectile dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and insomnia.

More recently, Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators have pioneered the development of I-CBT as an evidence-based treatment for OCD. They now are in the process of doing the same for body dysmorphic disorder, a related condition that’s often particularly challenging to treat successfully.

The investigators’ first large randomized controlled trial of I-CBT for OCD included 101 patients with a mean 18-year history of the disorder. They were assigned to 10 weeks of the online therapy or to an online supportive care control arm. Mean scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) improved from 21.4 at baseline to 12.9 upon completion of the I-CBT program and 12.6 at follow-up 4 months post treatment. Sixty percent of the I-CBT group demonstrated clinically significant improvement, compared with 6% of controls (Psychol Med. 2012 Oct;42[10]:2193-203).

The benefit proved durable, as demonstrated in an extension study with periodic follow-up out to 24 months post completion of the I-CBT program. The incorporation of an Internet-based booster program in one arm of the follow-up protocol protected against relapses (Psychol Med. 2014 Oct;44[13]2877-87).

Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators also have shown in a 128-patient, double-blind trial that d-cycloserine, a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate agonist that promotes fear extinction, augmented the response to I-CBT for OCD, but only in the subgroup not on concomitant antidepressant therapy. The remission rate was 60% at 3 months follow-up post I-CBT in antidepressant-free patients on d-cycloserine, compared with just 24% in d-cycloserine recipients taking antidepressants during I-CBT. Apparently, antidepressants blunt d-cycloserine’s fear-extinction effect (JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;72[7]:659-67).

The program content of I-CBT is the same as in conventional manualized CBT, but without the face-to-face contact. The I-CBT program consists of 10-15 weekly chapters or modules. There is homework, worksheets, and titrated exposures to fear-eliciting situations. Progress to the next module is contingent upon completion of the previous one, with the patient being required to successfully answer questions that show mastery of the material.

Most patients rate the program favorably. They like not having to show up in the therapist’s office week after week.

“One of the advantages of I-CBT is you can interact every day. If your exposure goes wrong you don’t have to wait 6 days until your next face-to-face appointment with your therapist; you can actually get treatment right away and in that way increase the speed of progress,” Dr. Rück observed.

Also, if the patient forgets a basic concept, he or she can go back and reread.

“Everything is saved. This makes it very easy to supervise. There’s nothing going on that can’t be seen. Isaac M. Marks, MD, an early OCD researcher at Imperial College London, once said that one of the greatest advantages of I-CBT is that the therapist can’t sleep with the patient,” Dr. Rück recalled.

His research group is now in the midst of a clinical trial designed to answer two key questions: Is I-CBT for OCD as effective as face-to-face CBT? And is the therapist really necessary in order to achieve optimal outcomes in I-CBT?

“It would be a kind of shock to us if all our therapist impact is for nothing, but we’ll find out soon,” he promised.

Dr. Rück and his coinvestigators recently developed a program for therapist-supervised I-CBT for patients with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). In a single-blind pilot clinical trial involving 94 adults with BDD, the clinical response rate at 6 months of follow-up as defined by at least a 30% reduction from baseline in scores on the BDD–Y-BOCS was 56% in the I-CBT arm and 13% in controls assigned to online supportive care. The number needed to treat was impressively low, at 2.3. And those results were achieved by clinical psychology students having no prior experience with BDD, although they were closely supervised by an experienced clinician (BMJ. 2016 Feb 2;352:i241.

Dr. Rück has been disappointed to find that physicians, psychotherapists, and health care systems have been slow to embrace I-CBT for the conditions where there is solid supportive randomized trial evidence. I-CBT has been implemented within health care systems only in Australia and Stockholm County, the places where most of the research has been conducted.

“The literature has been around for about 15 years now, and we are noticing that the rollout of this is terribly slow. I’m starting to think that the health care system itself is one of the most problematic roadblocks, especially with regard to reimbursement issues. Maybe I-CBT should be offered outside of the health care system. Sometimes I think Google would do this better than a nationalized health care system,” the psychiatrist mused.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS At THE ECNP CONGRESS

Metabolic dysregulation may predict remission failure in late-life depression

SAN FRANCISCO – Metabolic dysregulation and particularly abdominal obesity lead to failure to remit in late-life depression, according to a multicenter, prospective cohort study.

The finding highlights the need for comprehensive interventions for comorbid late-life depression and metabolic syndrome, Radboud M. Marijnissen, MD, said during an oral presentation at the 2016 congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association..

Late-life depression is notoriously refractory to antidepressant monotherapy, he said. Metabolic syndrome becomes more common with age and is reciprocally related to depression, but few studies have examined links between these two conditions, said Dr. Marijnissen of the department of old age psychiatry at the Pro Persona Medical Center in Wolfheze, the Netherlands. Therefore, he and his associates examined Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) scores and metabolic data from 285 patients aged 60 years and older who met DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders. The patients were participants in the observational, prospective multicenter Netherlands study of depression in older persons (NESDO), which assessed patients every 6 months for 2 years. The researchers defined metabolic syndrome based on National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATP III) criteria, which include measures for central obesity, hypertension, and elevated blood levels of glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Dr. Marijnissen said. In his study, most patients were receiving regular mental health care, including antidepressants and psychotherapy.

At 2 years, patients were significantly less likely to have achieved complete remission from depression when they had components of metabolic syndrome than otherwise (42% vs. 58%; P = .01). Furthermore, each additional component of metabolic syndrome increased the odds of failure to remit by 27% (odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.58; P = .028), even after the investigators controlled for multiple potential confounders, including age, sex, marital status, tobacco and alcohol use, level of education, physical activity, comorbidities, the presence of cognitive impairment, and the use of psychotropic and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Interestingly, specific components of metabolic syndrome seemed to exert different effects on the likelihood of remission, Dr. Marijnissen said. Increased waist circumference and HDL cholesterol each independently predicted failure to achieve remission, with odds ratios of 1.96 (95% CI, 1.15-3.32; P = .013) and 2.35 (1.21-4.53; P = .011), respectively. In contrast, elevated triglycerides predicted remission failure, but the link did not reach statistical significance, and hypertension and elevated fasting blood glucose levels showed no trend in either direction.

Further analyses of scores on the three subscales of the IDS again linked abdominal obesity, as well as elevated fasting blood glucose, with persistent somatic features of depression (P = .046 and .02, respectively). In contrast, neither the total number of metabolic syndrome components nor the presence or absence of any individual component predicted persistently elevated scores on the mood or motivation subscales of the IDS (P greater than .4 for each association). In addition, neither metabolic syndrome nor its individual components predicted depression severity.

These findings suggest that metabolic dysregulation leads to remission failure with persistent somatic symptoms in late-life depression, and that central obesity drives this relationship, Dr. Marijnissen concluded. “Metabolic depression calls for specific interventions,” he added. “People who are suffering from this subtype of depression may benefit from vascular disease management, healthy nutrition, and programs that emphasize exercise, including resistance training to help turn white fat into brown fat, which lowers metabolic risk as well as depressive symptoms.”

Dr. Marijnissen reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – Metabolic dysregulation and particularly abdominal obesity lead to failure to remit in late-life depression, according to a multicenter, prospective cohort study.

The finding highlights the need for comprehensive interventions for comorbid late-life depression and metabolic syndrome, Radboud M. Marijnissen, MD, said during an oral presentation at the 2016 congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association..

Late-life depression is notoriously refractory to antidepressant monotherapy, he said. Metabolic syndrome becomes more common with age and is reciprocally related to depression, but few studies have examined links between these two conditions, said Dr. Marijnissen of the department of old age psychiatry at the Pro Persona Medical Center in Wolfheze, the Netherlands. Therefore, he and his associates examined Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) scores and metabolic data from 285 patients aged 60 years and older who met DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders. The patients were participants in the observational, prospective multicenter Netherlands study of depression in older persons (NESDO), which assessed patients every 6 months for 2 years. The researchers defined metabolic syndrome based on National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATP III) criteria, which include measures for central obesity, hypertension, and elevated blood levels of glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Dr. Marijnissen said. In his study, most patients were receiving regular mental health care, including antidepressants and psychotherapy.

At 2 years, patients were significantly less likely to have achieved complete remission from depression when they had components of metabolic syndrome than otherwise (42% vs. 58%; P = .01). Furthermore, each additional component of metabolic syndrome increased the odds of failure to remit by 27% (odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.58; P = .028), even after the investigators controlled for multiple potential confounders, including age, sex, marital status, tobacco and alcohol use, level of education, physical activity, comorbidities, the presence of cognitive impairment, and the use of psychotropic and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Interestingly, specific components of metabolic syndrome seemed to exert different effects on the likelihood of remission, Dr. Marijnissen said. Increased waist circumference and HDL cholesterol each independently predicted failure to achieve remission, with odds ratios of 1.96 (95% CI, 1.15-3.32; P = .013) and 2.35 (1.21-4.53; P = .011), respectively. In contrast, elevated triglycerides predicted remission failure, but the link did not reach statistical significance, and hypertension and elevated fasting blood glucose levels showed no trend in either direction.

Further analyses of scores on the three subscales of the IDS again linked abdominal obesity, as well as elevated fasting blood glucose, with persistent somatic features of depression (P = .046 and .02, respectively). In contrast, neither the total number of metabolic syndrome components nor the presence or absence of any individual component predicted persistently elevated scores on the mood or motivation subscales of the IDS (P greater than .4 for each association). In addition, neither metabolic syndrome nor its individual components predicted depression severity.

These findings suggest that metabolic dysregulation leads to remission failure with persistent somatic symptoms in late-life depression, and that central obesity drives this relationship, Dr. Marijnissen concluded. “Metabolic depression calls for specific interventions,” he added. “People who are suffering from this subtype of depression may benefit from vascular disease management, healthy nutrition, and programs that emphasize exercise, including resistance training to help turn white fat into brown fat, which lowers metabolic risk as well as depressive symptoms.”

Dr. Marijnissen reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – Metabolic dysregulation and particularly abdominal obesity lead to failure to remit in late-life depression, according to a multicenter, prospective cohort study.

The finding highlights the need for comprehensive interventions for comorbid late-life depression and metabolic syndrome, Radboud M. Marijnissen, MD, said during an oral presentation at the 2016 congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association..

Late-life depression is notoriously refractory to antidepressant monotherapy, he said. Metabolic syndrome becomes more common with age and is reciprocally related to depression, but few studies have examined links between these two conditions, said Dr. Marijnissen of the department of old age psychiatry at the Pro Persona Medical Center in Wolfheze, the Netherlands. Therefore, he and his associates examined Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) scores and metabolic data from 285 patients aged 60 years and older who met DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders. The patients were participants in the observational, prospective multicenter Netherlands study of depression in older persons (NESDO), which assessed patients every 6 months for 2 years. The researchers defined metabolic syndrome based on National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATP III) criteria, which include measures for central obesity, hypertension, and elevated blood levels of glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Dr. Marijnissen said. In his study, most patients were receiving regular mental health care, including antidepressants and psychotherapy.

At 2 years, patients were significantly less likely to have achieved complete remission from depression when they had components of metabolic syndrome than otherwise (42% vs. 58%; P = .01). Furthermore, each additional component of metabolic syndrome increased the odds of failure to remit by 27% (odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.58; P = .028), even after the investigators controlled for multiple potential confounders, including age, sex, marital status, tobacco and alcohol use, level of education, physical activity, comorbidities, the presence of cognitive impairment, and the use of psychotropic and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Interestingly, specific components of metabolic syndrome seemed to exert different effects on the likelihood of remission, Dr. Marijnissen said. Increased waist circumference and HDL cholesterol each independently predicted failure to achieve remission, with odds ratios of 1.96 (95% CI, 1.15-3.32; P = .013) and 2.35 (1.21-4.53; P = .011), respectively. In contrast, elevated triglycerides predicted remission failure, but the link did not reach statistical significance, and hypertension and elevated fasting blood glucose levels showed no trend in either direction.

Further analyses of scores on the three subscales of the IDS again linked abdominal obesity, as well as elevated fasting blood glucose, with persistent somatic features of depression (P = .046 and .02, respectively). In contrast, neither the total number of metabolic syndrome components nor the presence or absence of any individual component predicted persistently elevated scores on the mood or motivation subscales of the IDS (P greater than .4 for each association). In addition, neither metabolic syndrome nor its individual components predicted depression severity.

These findings suggest that metabolic dysregulation leads to remission failure with persistent somatic symptoms in late-life depression, and that central obesity drives this relationship, Dr. Marijnissen concluded. “Metabolic depression calls for specific interventions,” he added. “People who are suffering from this subtype of depression may benefit from vascular disease management, healthy nutrition, and programs that emphasize exercise, including resistance training to help turn white fat into brown fat, which lowers metabolic risk as well as depressive symptoms.”

Dr. Marijnissen reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

AT IPA 2016

Key clinical point: Patients with late-life depression are less likely to achieve complete remission if they have components of metabolic syndrome.

Major finding: Higher waist circumference and cholesterol levels both predicted failure to remit at 2-year follow-up, with statistically significant odds ratios of 1.96 and 2.35, respectively.

Data source: A prospective, multicenter cohort study of 285 adults aged 60 years and up who met DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders.

Disclosures: Dr. Marijnissen reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Artificial intelligence beats standard algorithms for diagnosing lung disease

LONDON – In a proof-of-principle study, artificial intelligence (AI) led more frequently to the correct diagnosis of underlying lung disease than did physicians’ use of standard algorithms, such as those recommended by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society, according to late-breaker data presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“The beauty of this approach is that artificial intelligence can simulate the complex reasoning that clinicians use to reach their diagnosis but in a more standardized and objective fashion, so it removes any bias,” reported Wim Janssens, MD, PhD, of the division of medicine and respiratory rehabilitation at University of Leuven (Belgium).

The AI employed in this study was based on a subfield of computer science that relies on patterns within statistics to build decision trees. Often called machine learning, this type of AI grows smarter as it learns from the patterns it finds in the data provided.

In this case, the AI was designed to provide diagnoses for lung diseases based on patterns drawn from clinical and lung function data. The computer-based choices were compared to diagnoses reached by clinicians. The final diagnoses were validated by a consensus of expert clinicians.

“The computer-based choices were in almost all cases better than the choices made by standard diagnostic algorithms,” reported Marko Topalovic, PhD, a researcher in AI who is affiliated with the University of Leuven. Dr. Topalovic presented the data at the ERS.

The study involved 968 patients presenting with lung symptoms to a pulmonary clinic for the first time. Standard clinical data, such as smoking history, body mass index, and age, were collected. Lung function studies conducted in all patients included spirometry, body plethysmography, and airway diffusion, although participating clinicians were permitted to order additional tests at their own discretion. Clinical diagnoses were separated into 10 predefined disease groups.

The average accuracy of clinicians’ diagnoses was 38%. The clinicians were best at identifying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), having accurately diagnosed 74% of the cases of this disease. For other disease groups, the clinician’s accuracy rarely exceeded 50%.

The diagnoses made by AI, on the other hand, on average, were 68% accurate. For diagnosing COPD, the AI achieved a positive predictive value of 83% and a sensitivity of 78%. The positive predictive value and sensitivity of AI for asthma (66% and 82%, respectively) and interstitial lung disease (52% and 59%) were both significantly greater than those achieved by the clinicians.

When findings are ambiguous or there are anomalies in the clinical picture, a final clinical diagnosis can be challenging, according to Dr. Janssens. He suggested that automation eliminates the potential for bias, which often occurs when clinicians inadvertently give more weight to one clinical variable relative to another.

The decision-making system tested in this study was characterized as “a first step to automated interpretation of lung function,” Dr. Topalovic said. He added that he expects the AI to improve as it receives more data.

“Not only do we think this system can help nonexperienced clinicians, but it will help experts reach a diagnosis more quickly,” Dr. Topalovic said. Noting that this same approach is being pursued in other fields of medicine, he said he thinks adding AI to respiratory medicine will reduce the number of redundant tests and, in other ways, introduce opportunities for efficiencies and reduced costs.

Dr. Topalovic and Dr. Janssens reported no relevant financial relationships.

LONDON – In a proof-of-principle study, artificial intelligence (AI) led more frequently to the correct diagnosis of underlying lung disease than did physicians’ use of standard algorithms, such as those recommended by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society, according to late-breaker data presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“The beauty of this approach is that artificial intelligence can simulate the complex reasoning that clinicians use to reach their diagnosis but in a more standardized and objective fashion, so it removes any bias,” reported Wim Janssens, MD, PhD, of the division of medicine and respiratory rehabilitation at University of Leuven (Belgium).

The AI employed in this study was based on a subfield of computer science that relies on patterns within statistics to build decision trees. Often called machine learning, this type of AI grows smarter as it learns from the patterns it finds in the data provided.

In this case, the AI was designed to provide diagnoses for lung diseases based on patterns drawn from clinical and lung function data. The computer-based choices were compared to diagnoses reached by clinicians. The final diagnoses were validated by a consensus of expert clinicians.

“The computer-based choices were in almost all cases better than the choices made by standard diagnostic algorithms,” reported Marko Topalovic, PhD, a researcher in AI who is affiliated with the University of Leuven. Dr. Topalovic presented the data at the ERS.

The study involved 968 patients presenting with lung symptoms to a pulmonary clinic for the first time. Standard clinical data, such as smoking history, body mass index, and age, were collected. Lung function studies conducted in all patients included spirometry, body plethysmography, and airway diffusion, although participating clinicians were permitted to order additional tests at their own discretion. Clinical diagnoses were separated into 10 predefined disease groups.

The average accuracy of clinicians’ diagnoses was 38%. The clinicians were best at identifying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), having accurately diagnosed 74% of the cases of this disease. For other disease groups, the clinician’s accuracy rarely exceeded 50%.

The diagnoses made by AI, on the other hand, on average, were 68% accurate. For diagnosing COPD, the AI achieved a positive predictive value of 83% and a sensitivity of 78%. The positive predictive value and sensitivity of AI for asthma (66% and 82%, respectively) and interstitial lung disease (52% and 59%) were both significantly greater than those achieved by the clinicians.

When findings are ambiguous or there are anomalies in the clinical picture, a final clinical diagnosis can be challenging, according to Dr. Janssens. He suggested that automation eliminates the potential for bias, which often occurs when clinicians inadvertently give more weight to one clinical variable relative to another.

The decision-making system tested in this study was characterized as “a first step to automated interpretation of lung function,” Dr. Topalovic said. He added that he expects the AI to improve as it receives more data.

“Not only do we think this system can help nonexperienced clinicians, but it will help experts reach a diagnosis more quickly,” Dr. Topalovic said. Noting that this same approach is being pursued in other fields of medicine, he said he thinks adding AI to respiratory medicine will reduce the number of redundant tests and, in other ways, introduce opportunities for efficiencies and reduced costs.

Dr. Topalovic and Dr. Janssens reported no relevant financial relationships.

LONDON – In a proof-of-principle study, artificial intelligence (AI) led more frequently to the correct diagnosis of underlying lung disease than did physicians’ use of standard algorithms, such as those recommended by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society, according to late-breaker data presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“The beauty of this approach is that artificial intelligence can simulate the complex reasoning that clinicians use to reach their diagnosis but in a more standardized and objective fashion, so it removes any bias,” reported Wim Janssens, MD, PhD, of the division of medicine and respiratory rehabilitation at University of Leuven (Belgium).

The AI employed in this study was based on a subfield of computer science that relies on patterns within statistics to build decision trees. Often called machine learning, this type of AI grows smarter as it learns from the patterns it finds in the data provided.

In this case, the AI was designed to provide diagnoses for lung diseases based on patterns drawn from clinical and lung function data. The computer-based choices were compared to diagnoses reached by clinicians. The final diagnoses were validated by a consensus of expert clinicians.

“The computer-based choices were in almost all cases better than the choices made by standard diagnostic algorithms,” reported Marko Topalovic, PhD, a researcher in AI who is affiliated with the University of Leuven. Dr. Topalovic presented the data at the ERS.

The study involved 968 patients presenting with lung symptoms to a pulmonary clinic for the first time. Standard clinical data, such as smoking history, body mass index, and age, were collected. Lung function studies conducted in all patients included spirometry, body plethysmography, and airway diffusion, although participating clinicians were permitted to order additional tests at their own discretion. Clinical diagnoses were separated into 10 predefined disease groups.

The average accuracy of clinicians’ diagnoses was 38%. The clinicians were best at identifying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), having accurately diagnosed 74% of the cases of this disease. For other disease groups, the clinician’s accuracy rarely exceeded 50%.

The diagnoses made by AI, on the other hand, on average, were 68% accurate. For diagnosing COPD, the AI achieved a positive predictive value of 83% and a sensitivity of 78%. The positive predictive value and sensitivity of AI for asthma (66% and 82%, respectively) and interstitial lung disease (52% and 59%) were both significantly greater than those achieved by the clinicians.

When findings are ambiguous or there are anomalies in the clinical picture, a final clinical diagnosis can be challenging, according to Dr. Janssens. He suggested that automation eliminates the potential for bias, which often occurs when clinicians inadvertently give more weight to one clinical variable relative to another.

The decision-making system tested in this study was characterized as “a first step to automated interpretation of lung function,” Dr. Topalovic said. He added that he expects the AI to improve as it receives more data.

“Not only do we think this system can help nonexperienced clinicians, but it will help experts reach a diagnosis more quickly,” Dr. Topalovic said. Noting that this same approach is being pursued in other fields of medicine, he said he thinks adding AI to respiratory medicine will reduce the number of redundant tests and, in other ways, introduce opportunities for efficiencies and reduced costs.

Dr. Topalovic and Dr. Janssens reported no relevant financial relationships.

AT THE ERS CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: When given the same clinical information, artificial intelligence is more likely than are clinicians to diagnose lung diseases correctly.

Major finding: The diagnostic label was correct in 38% of cases with standard algorithms, versus 68% with artificial intelligence.

Data source: Prospective study.

Disclosures: Dr. Marko Topalovic and Dr. Wim Janssens reported no relevant financial relationships.

Baseline extrapyramidal signs predicted non-Alzheimer’s dementia in patients with MCI

SAN FRANCISCO – Among patients with mild cognitive impairment, those with extrapyramidal signs were about six times more likely to develop non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia than those without baseline extrapyramidal signs, according to a prospective multicenter analysis.

The study is among the first to examine the link between extrapyramidal signs and dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease, said Woojae Myung, MD, of Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea, and his associates. “Our results suggest that careful assessment of extrapyramidal signs in patients with incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) can yield important clinical information for prognosis,” the researchers wrote in a poster presented at the 2016 congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.

The study included 882 adults who were enrolled in the Clinical Research Center for Dementia of Korea (CREDOS) registry between 2006 and 2012. All participants met criteria for mild cognitive impairment based on the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and also underwent standardized neurologic examinations, magnetic resonance imaging, and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) at baseline, Dr. Myung and his coinvestigators reported.

In all, 234 patients (26%) converted to dementia over a median follow-up time of 1.44 years (interquartile range, 1.02-2.24 years). Most (92%, or 216) patients who developed dementia had probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 9 had vascular dementia, 4 had Lewy body dementia, 3 had frontotemporal dementia, 1 had progressive supranuclear palsy, and 1 had dementia associated with normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Baseline extrapyramidal signs were the only significant factor associated with progression to non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia (hazard ratio, 6.33; 95% confidence interval, 2.30-13.39; P less than .001) after controlling for age, gender, educational level, diabetes, hypertension, MRI evidence of matter hyperintensity, GDS-15 score, and level of cognitive impairment at baseline, the researchers reported. Furthermore, patients with baseline extrapyramidal signs were about 30% less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than were patients who did not have extrapyramidal signs at baseline.

Significant predictors of Alzheimer’s disease included older age, higher educational level, absence of hypertension, and a lower K-MMSE score, as well as the presence of amnestic mild cognitive impairment, the investigators noted.

They disclosed no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – Among patients with mild cognitive impairment, those with extrapyramidal signs were about six times more likely to develop non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia than those without baseline extrapyramidal signs, according to a prospective multicenter analysis.

The study is among the first to examine the link between extrapyramidal signs and dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease, said Woojae Myung, MD, of Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea, and his associates. “Our results suggest that careful assessment of extrapyramidal signs in patients with incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) can yield important clinical information for prognosis,” the researchers wrote in a poster presented at the 2016 congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.

The study included 882 adults who were enrolled in the Clinical Research Center for Dementia of Korea (CREDOS) registry between 2006 and 2012. All participants met criteria for mild cognitive impairment based on the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and also underwent standardized neurologic examinations, magnetic resonance imaging, and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) at baseline, Dr. Myung and his coinvestigators reported.

In all, 234 patients (26%) converted to dementia over a median follow-up time of 1.44 years (interquartile range, 1.02-2.24 years). Most (92%, or 216) patients who developed dementia had probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 9 had vascular dementia, 4 had Lewy body dementia, 3 had frontotemporal dementia, 1 had progressive supranuclear palsy, and 1 had dementia associated with normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Baseline extrapyramidal signs were the only significant factor associated with progression to non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia (hazard ratio, 6.33; 95% confidence interval, 2.30-13.39; P less than .001) after controlling for age, gender, educational level, diabetes, hypertension, MRI evidence of matter hyperintensity, GDS-15 score, and level of cognitive impairment at baseline, the researchers reported. Furthermore, patients with baseline extrapyramidal signs were about 30% less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than were patients who did not have extrapyramidal signs at baseline.

Significant predictors of Alzheimer’s disease included older age, higher educational level, absence of hypertension, and a lower K-MMSE score, as well as the presence of amnestic mild cognitive impairment, the investigators noted.

They disclosed no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – Among patients with mild cognitive impairment, those with extrapyramidal signs were about six times more likely to develop non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia than those without baseline extrapyramidal signs, according to a prospective multicenter analysis.

The study is among the first to examine the link between extrapyramidal signs and dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease, said Woojae Myung, MD, of Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea, and his associates. “Our results suggest that careful assessment of extrapyramidal signs in patients with incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) can yield important clinical information for prognosis,” the researchers wrote in a poster presented at the 2016 congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.

The study included 882 adults who were enrolled in the Clinical Research Center for Dementia of Korea (CREDOS) registry between 2006 and 2012. All participants met criteria for mild cognitive impairment based on the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and also underwent standardized neurologic examinations, magnetic resonance imaging, and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) at baseline, Dr. Myung and his coinvestigators reported.

In all, 234 patients (26%) converted to dementia over a median follow-up time of 1.44 years (interquartile range, 1.02-2.24 years). Most (92%, or 216) patients who developed dementia had probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 9 had vascular dementia, 4 had Lewy body dementia, 3 had frontotemporal dementia, 1 had progressive supranuclear palsy, and 1 had dementia associated with normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Baseline extrapyramidal signs were the only significant factor associated with progression to non-Alzheimer’s forms of dementia (hazard ratio, 6.33; 95% confidence interval, 2.30-13.39; P less than .001) after controlling for age, gender, educational level, diabetes, hypertension, MRI evidence of matter hyperintensity, GDS-15 score, and level of cognitive impairment at baseline, the researchers reported. Furthermore, patients with baseline extrapyramidal signs were about 30% less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than were patients who did not have extrapyramidal signs at baseline.

Significant predictors of Alzheimer’s disease included older age, higher educational level, absence of hypertension, and a lower K-MMSE score, as well as the presence of amnestic mild cognitive impairment, the investigators noted.

They disclosed no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

AT IPA 2016

Key clinical point: In patients with mild cognitive impairment, extrapyramidal signs predicted progression to non-Alzheimer’s dementia.

Major finding: Over a median of 1.4 years, patients with baseline extrapyramidal signs were about 30% less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease but six times more likely to develop other forms of dementia, compared with patients without such signs.

Data source: A prospective multicenter study of 882 adults with mild cognitive impairment.

Disclosures: The researchers disclosed no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

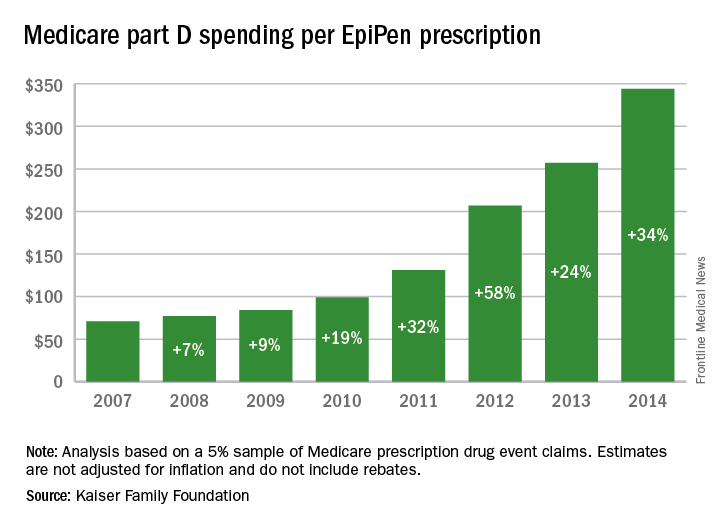

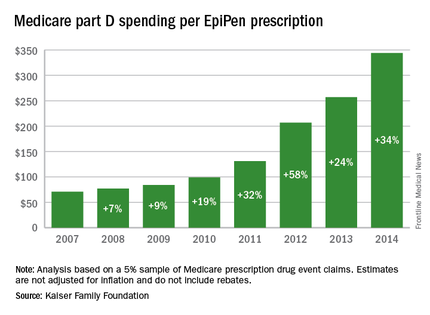

EpiPen cost increases far exceed overall medical inflation

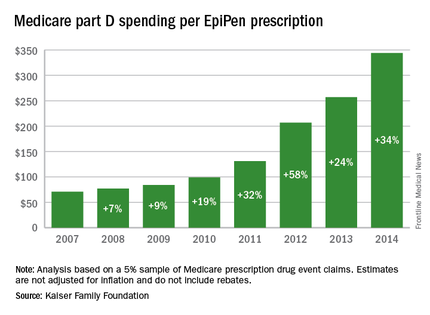

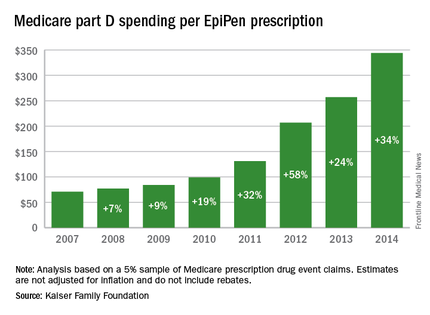

Total Medicare part D spending on EpiPen auto-injectors rose from $7.0 million in 2007 to $87.9 million in 2014 – an increase of 1,151%, according to an analysis released Sept. 20 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number of EpiPen users also increased over that time, however, bringing with it a commensurate 159% rise in the number of prescriptions. Those two trends took the average cost of a single EpiPen prescription from $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014, the Kaiser analysis showed.

That increase in cost per prescription did not fail to at least double overall medical care price inflation for each year from 2008 to 2014. In 2008, when the two trends were closest together, the EpiPen cost per prescription rose 7.4% from the year before, compared with 3.7% for overall medical spending. In 2014, Medicare part D’s cost for an EpiPen prescription rose 34% from the year before, which was 14 times higher than the 2.4% increase in total medical spending, Kaiser noted.

The analysis was based on a 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug event claims and included beneficiaries who had a least 1 month of part D coverage and one EpiPen prescription during the year. Estimates are not adjusted for inflation and do not include any possible manufacturer discounts, Kaiser said.

Total Medicare part D spending on EpiPen auto-injectors rose from $7.0 million in 2007 to $87.9 million in 2014 – an increase of 1,151%, according to an analysis released Sept. 20 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number of EpiPen users also increased over that time, however, bringing with it a commensurate 159% rise in the number of prescriptions. Those two trends took the average cost of a single EpiPen prescription from $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014, the Kaiser analysis showed.

That increase in cost per prescription did not fail to at least double overall medical care price inflation for each year from 2008 to 2014. In 2008, when the two trends were closest together, the EpiPen cost per prescription rose 7.4% from the year before, compared with 3.7% for overall medical spending. In 2014, Medicare part D’s cost for an EpiPen prescription rose 34% from the year before, which was 14 times higher than the 2.4% increase in total medical spending, Kaiser noted.

The analysis was based on a 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug event claims and included beneficiaries who had a least 1 month of part D coverage and one EpiPen prescription during the year. Estimates are not adjusted for inflation and do not include any possible manufacturer discounts, Kaiser said.

Total Medicare part D spending on EpiPen auto-injectors rose from $7.0 million in 2007 to $87.9 million in 2014 – an increase of 1,151%, according to an analysis released Sept. 20 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number of EpiPen users also increased over that time, however, bringing with it a commensurate 159% rise in the number of prescriptions. Those two trends took the average cost of a single EpiPen prescription from $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014, the Kaiser analysis showed.

That increase in cost per prescription did not fail to at least double overall medical care price inflation for each year from 2008 to 2014. In 2008, when the two trends were closest together, the EpiPen cost per prescription rose 7.4% from the year before, compared with 3.7% for overall medical spending. In 2014, Medicare part D’s cost for an EpiPen prescription rose 34% from the year before, which was 14 times higher than the 2.4% increase in total medical spending, Kaiser noted.

The analysis was based on a 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug event claims and included beneficiaries who had a least 1 month of part D coverage and one EpiPen prescription during the year. Estimates are not adjusted for inflation and do not include any possible manufacturer discounts, Kaiser said.

Legislators: Investigate Medicare fraud before paying doctors

Republican leaders in Congress are calling on CMS to impose stricter safeguards against fraudulent Medicare billing by physicians.

The chairmen of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees, and the chairmen of key House subcommittees said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services relies too heavily on the “outdated” pay and chase method and should focus more energy on preventing payment for potential fraudulent claims.

“Improper payments remain an enormous problem for the Medicare program,” the chairmen wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt. “In 2015, the Medicare program had an error rate of 12.1% or $43.3 billion dollars. The billions of dollars lost to Medicare fraud each year underscore the importance of stopping potentially fraudulent payments before they’re made,”

Some health law experts, however, argue that CMS already has a process for in place for pre-identifying inaccurate claims via prepayment audits and reviews. Such efforts can be devastating for physicians who come under scrutiny for unintentional mistakes, said Daniel F. Shay, a Philadelphia health law attorney.

“I can understand why, particularly in an election year, elected officials might send a letter reiterating the need to curb ‘waste, fraud, and abuse,’” Mr. Shay said in an interview. “It’s true that it’s more efficient for the government to investigate a physician’s claim for reimbursement first, and then pay. However, I think we have to take into account the physicians’ perspective, especially physicians in smaller, independent practices.”

The legislators’ letter acknowledges that CMS has taken some proactive steps to prevent health fraud, including creation of the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), which highlights questionable billing patterns and identifies providers who pose high risk to the program. FPS runs analytics on 4.5 million claims daily and has led to more than $820 million in savings, according to CMS. However, legislators said they are still concerned that CMS too often pays claims before investigating whether they’re false. The letter requests that CMS clarify its implementation of the FPS program, including details on fraud investigations and how the agency monitors FPS’s effectiveness.

Houston, Tex.–based health law attorney Michael E. Clark disagrees that CMS is overusing the pay-and-chase method. Quite the contrary, he said.

“The federal government cannot seem to find the right balance on how to address program fraud,” Mr. Clark said in an interview. “While ‘pay and chase’ once was a problem, now the government can effectively destroy health care service providers under a very low threshold without the businesses having a meaningful right to appeal that determination.”

Specifically, CMS can withhold Medicare reimbursement from health providers under an amended 2011 law that permits payments to be suppressed when “credible” allegations of fraud have been made, but are disputed. The term “credible” is a new, lower standard for the administrative action, which was meant to address the pay-and-chase problem, Mr. Clark said. The law defines a “credible allegation of fraud” as an allegation from any source, including but not limited to fraud hotline complaints, data mining of claims, patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations.

“That standard is easy to meet and agencies have every incentive to claim they’ve got so-called credible allegations of fraud in order to avoid being criticized later on for not preventing the monies from being dissipated,” he said. Because the law precludes health providers from appealing the fraud allegation to a federal court until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, “a health care services provider can quickly be put out of business, even if it turns out that the investigation proves not to be actionable.”

Prepayment reviews of claims can drag on for months, severely impacting a physician’s income, Mr. Shay added. In his experience, the majority of physicians under investigation are not trying to game the system, but rather don’t understand all of the administrative requirements related to filing claims. In some cases, the physicians’ notes are not complete, their bills are too high for services provided, or not enough documentation exists to support medical necessity.

“In the midst of that, you have doctors who are likely well-meaning, who have provided a service to a patient in need, and who are facing real economic hardship without an effective mechanism to challenge or end the prepayment review process,” he said.

Rather than more prepayment investigations, Mr. Shay would like to see CMS focus on physician education.

There needs to be “more emphasis on provider education in terms of compliance with program requirements,” he said. “It shouldn’t require a lawyer getting involved to find out what specifically [CMS] wants them to do. That should be part of the process as a standard.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Republican leaders in Congress are calling on CMS to impose stricter safeguards against fraudulent Medicare billing by physicians.

The chairmen of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees, and the chairmen of key House subcommittees said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services relies too heavily on the “outdated” pay and chase method and should focus more energy on preventing payment for potential fraudulent claims.

“Improper payments remain an enormous problem for the Medicare program,” the chairmen wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt. “In 2015, the Medicare program had an error rate of 12.1% or $43.3 billion dollars. The billions of dollars lost to Medicare fraud each year underscore the importance of stopping potentially fraudulent payments before they’re made,”

Some health law experts, however, argue that CMS already has a process for in place for pre-identifying inaccurate claims via prepayment audits and reviews. Such efforts can be devastating for physicians who come under scrutiny for unintentional mistakes, said Daniel F. Shay, a Philadelphia health law attorney.

“I can understand why, particularly in an election year, elected officials might send a letter reiterating the need to curb ‘waste, fraud, and abuse,’” Mr. Shay said in an interview. “It’s true that it’s more efficient for the government to investigate a physician’s claim for reimbursement first, and then pay. However, I think we have to take into account the physicians’ perspective, especially physicians in smaller, independent practices.”

The legislators’ letter acknowledges that CMS has taken some proactive steps to prevent health fraud, including creation of the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), which highlights questionable billing patterns and identifies providers who pose high risk to the program. FPS runs analytics on 4.5 million claims daily and has led to more than $820 million in savings, according to CMS. However, legislators said they are still concerned that CMS too often pays claims before investigating whether they’re false. The letter requests that CMS clarify its implementation of the FPS program, including details on fraud investigations and how the agency monitors FPS’s effectiveness.

Houston, Tex.–based health law attorney Michael E. Clark disagrees that CMS is overusing the pay-and-chase method. Quite the contrary, he said.

“The federal government cannot seem to find the right balance on how to address program fraud,” Mr. Clark said in an interview. “While ‘pay and chase’ once was a problem, now the government can effectively destroy health care service providers under a very low threshold without the businesses having a meaningful right to appeal that determination.”

Specifically, CMS can withhold Medicare reimbursement from health providers under an amended 2011 law that permits payments to be suppressed when “credible” allegations of fraud have been made, but are disputed. The term “credible” is a new, lower standard for the administrative action, which was meant to address the pay-and-chase problem, Mr. Clark said. The law defines a “credible allegation of fraud” as an allegation from any source, including but not limited to fraud hotline complaints, data mining of claims, patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations.

“That standard is easy to meet and agencies have every incentive to claim they’ve got so-called credible allegations of fraud in order to avoid being criticized later on for not preventing the monies from being dissipated,” he said. Because the law precludes health providers from appealing the fraud allegation to a federal court until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, “a health care services provider can quickly be put out of business, even if it turns out that the investigation proves not to be actionable.”

Prepayment reviews of claims can drag on for months, severely impacting a physician’s income, Mr. Shay added. In his experience, the majority of physicians under investigation are not trying to game the system, but rather don’t understand all of the administrative requirements related to filing claims. In some cases, the physicians’ notes are not complete, their bills are too high for services provided, or not enough documentation exists to support medical necessity.

“In the midst of that, you have doctors who are likely well-meaning, who have provided a service to a patient in need, and who are facing real economic hardship without an effective mechanism to challenge or end the prepayment review process,” he said.

Rather than more prepayment investigations, Mr. Shay would like to see CMS focus on physician education.

There needs to be “more emphasis on provider education in terms of compliance with program requirements,” he said. “It shouldn’t require a lawyer getting involved to find out what specifically [CMS] wants them to do. That should be part of the process as a standard.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Republican leaders in Congress are calling on CMS to impose stricter safeguards against fraudulent Medicare billing by physicians.

The chairmen of the Senate Finance Committee, the House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce Committees, and the chairmen of key House subcommittees said that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services relies too heavily on the “outdated” pay and chase method and should focus more energy on preventing payment for potential fraudulent claims.

“Improper payments remain an enormous problem for the Medicare program,” the chairmen wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt. “In 2015, the Medicare program had an error rate of 12.1% or $43.3 billion dollars. The billions of dollars lost to Medicare fraud each year underscore the importance of stopping potentially fraudulent payments before they’re made,”

Some health law experts, however, argue that CMS already has a process for in place for pre-identifying inaccurate claims via prepayment audits and reviews. Such efforts can be devastating for physicians who come under scrutiny for unintentional mistakes, said Daniel F. Shay, a Philadelphia health law attorney.

“I can understand why, particularly in an election year, elected officials might send a letter reiterating the need to curb ‘waste, fraud, and abuse,’” Mr. Shay said in an interview. “It’s true that it’s more efficient for the government to investigate a physician’s claim for reimbursement first, and then pay. However, I think we have to take into account the physicians’ perspective, especially physicians in smaller, independent practices.”

The legislators’ letter acknowledges that CMS has taken some proactive steps to prevent health fraud, including creation of the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), which highlights questionable billing patterns and identifies providers who pose high risk to the program. FPS runs analytics on 4.5 million claims daily and has led to more than $820 million in savings, according to CMS. However, legislators said they are still concerned that CMS too often pays claims before investigating whether they’re false. The letter requests that CMS clarify its implementation of the FPS program, including details on fraud investigations and how the agency monitors FPS’s effectiveness.

Houston, Tex.–based health law attorney Michael E. Clark disagrees that CMS is overusing the pay-and-chase method. Quite the contrary, he said.

“The federal government cannot seem to find the right balance on how to address program fraud,” Mr. Clark said in an interview. “While ‘pay and chase’ once was a problem, now the government can effectively destroy health care service providers under a very low threshold without the businesses having a meaningful right to appeal that determination.”

Specifically, CMS can withhold Medicare reimbursement from health providers under an amended 2011 law that permits payments to be suppressed when “credible” allegations of fraud have been made, but are disputed. The term “credible” is a new, lower standard for the administrative action, which was meant to address the pay-and-chase problem, Mr. Clark said. The law defines a “credible allegation of fraud” as an allegation from any source, including but not limited to fraud hotline complaints, data mining of claims, patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations.

“That standard is easy to meet and agencies have every incentive to claim they’ve got so-called credible allegations of fraud in order to avoid being criticized later on for not preventing the monies from being dissipated,” he said. Because the law precludes health providers from appealing the fraud allegation to a federal court until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, “a health care services provider can quickly be put out of business, even if it turns out that the investigation proves not to be actionable.”

Prepayment reviews of claims can drag on for months, severely impacting a physician’s income, Mr. Shay added. In his experience, the majority of physicians under investigation are not trying to game the system, but rather don’t understand all of the administrative requirements related to filing claims. In some cases, the physicians’ notes are not complete, their bills are too high for services provided, or not enough documentation exists to support medical necessity.

“In the midst of that, you have doctors who are likely well-meaning, who have provided a service to a patient in need, and who are facing real economic hardship without an effective mechanism to challenge or end the prepayment review process,” he said.

Rather than more prepayment investigations, Mr. Shay would like to see CMS focus on physician education.

There needs to be “more emphasis on provider education in terms of compliance with program requirements,” he said. “It shouldn’t require a lawyer getting involved to find out what specifically [CMS] wants them to do. That should be part of the process as a standard.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Innovation and Cancer Moonshot Highlight AVAHO Conference

The 12th annual Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) Meeting, which begins Friday, September 23 in Dallas, Texas, will present a broad range of topics that focus on innovations in both treatment and patient care. “Innovations are not a one-trick pony,” as William Wachsman, MD, PhD, AVAHO program chair pointed out. “We are broadening how we approach innovations for the entire AVAHO constituency.”

Geoffrey Ling, MD, PhD, director, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office will be the opening keynote speaker and will offer a peak into the future of the health care technologies being pioneered by the Department of Defense’s advanced research program. Dr. Lin is the office’s founding director and leads a group of scientists working to transform health care, synthetic biology, neuroscience, and other critical biological areas.

In the second keynote address, Deborah Mayer, RN, PhD, AOCN; professor, School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center will discuss cancer survivorship and how it fits into the cancer moonshot initiative. Dr. Mayer was named to the Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel earlier this year. Listen to an exclusive interview with Dr. Mayer below.

Click here for more information on the meeting and the complete agenda.

The 12th annual Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) Meeting, which begins Friday, September 23 in Dallas, Texas, will present a broad range of topics that focus on innovations in both treatment and patient care. “Innovations are not a one-trick pony,” as William Wachsman, MD, PhD, AVAHO program chair pointed out. “We are broadening how we approach innovations for the entire AVAHO constituency.”

Geoffrey Ling, MD, PhD, director, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office will be the opening keynote speaker and will offer a peak into the future of the health care technologies being pioneered by the Department of Defense’s advanced research program. Dr. Lin is the office’s founding director and leads a group of scientists working to transform health care, synthetic biology, neuroscience, and other critical biological areas.

In the second keynote address, Deborah Mayer, RN, PhD, AOCN; professor, School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center will discuss cancer survivorship and how it fits into the cancer moonshot initiative. Dr. Mayer was named to the Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel earlier this year. Listen to an exclusive interview with Dr. Mayer below.

Click here for more information on the meeting and the complete agenda.

The 12th annual Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) Meeting, which begins Friday, September 23 in Dallas, Texas, will present a broad range of topics that focus on innovations in both treatment and patient care. “Innovations are not a one-trick pony,” as William Wachsman, MD, PhD, AVAHO program chair pointed out. “We are broadening how we approach innovations for the entire AVAHO constituency.”

Geoffrey Ling, MD, PhD, director, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office will be the opening keynote speaker and will offer a peak into the future of the health care technologies being pioneered by the Department of Defense’s advanced research program. Dr. Lin is the office’s founding director and leads a group of scientists working to transform health care, synthetic biology, neuroscience, and other critical biological areas.

In the second keynote address, Deborah Mayer, RN, PhD, AOCN; professor, School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center will discuss cancer survivorship and how it fits into the cancer moonshot initiative. Dr. Mayer was named to the Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel earlier this year. Listen to an exclusive interview with Dr. Mayer below.

Click here for more information on the meeting and the complete agenda.

President Anita Aggarwal Welcomes Members to the 12th Annual Meeting of AVAHO

I’d like to personally welcome each of you to the 12th Annual Meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO). It’s an exciting time for AVAHO as we continue to grow and adapt, remaining always receptive, motivated and responsive to our member’s needs.

With more than 630 members nationwide, AVAHO is a membership-driven association. AVAHO members make a difference in the lives of their Veteran patients as an integral part of the health care team. Our current membership includes advanced practice nurses, cancer registrars, medical hematologists and oncologists, pharmacists, physician assistants, registered nurses, radiation oncologists, social workers, surgical oncologists, and other allied health professionals. Our focus on the whole health care team is unique and remains a core aspect of our mission.

The explosion of new technologies for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer is why we chose the 2016 Annual Meeting theme “Innovation in Hematology and Cancer Care.” By sharing new insights, we can make faster strides against cancer and take better care of our unique Veteran population. Now is the time when we need to adopt new technologies and design studies with new models of providing cancer care to Veterans. Change is inevitable, let’s get out in front and lead.

Data presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting will highlight innovation and technological advances that can improve every aspect of the patient experience—from prevention to diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.