User login

Preserving normal hematopoietic function in AML

Preclinical research has revealed a treatment that might preserve normal hematopoietic function in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found that AML suppresses adipocytes in the bone marrow, which leads to imbalanced regulation of endogenous hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and impaired myelo-erythroid maturation.

However, a PPARγ agonist can induce adipogenesis, which suppresses AML cells and stimulates the regeneration of healthy blood cells.

Researchers reported these findings in Nature Cell Biology.

The team found that adipocytes in the bone marrow support myelo-erythroid maturation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. But AML has a negative effect on the maturation of adipocytes, which explains why deficient myelo-erythropoiesis is “a consistent feature” of AML.

The researchers also found that pro-adipogenesis therapy—treatment with the PPARγ agonist GW1929—protects healthy myelo-erythropoiesis and limits leukemic self-renewal.

“Our approach represents a different way of looking at leukemia and considers the entire bone marrow as an ecosystem, rather than the traditional approach of studying and trying to directly kill the diseased cells themselves,” said study author Allison Boyd, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

“These traditional approaches have not delivered enough new therapeutic options for patients. The standard of care for this disease hasn’t changed in several decades.”

“The focus of chemotherapy and existing standard of care is on killing cancer cells, but, instead, we took a completely different approach, which changes the environment the cancer cells live in,” said study author Mick Bhatia, PhD, of McMaster University.

“This not only suppressed the ‘bad’ cancer cells but also bolstered the ‘good’ healthy cells, allowing them to regenerate in the new drug-induced environment. The fact that we can target one cell type in one tissue using an existing drug makes us excited about the possibilities of testing this in patients.”

“We can envision this becoming a potential new therapeutic approach that can either be added to existing treatments or even replace others in the near future. The fact that this drug activates blood regeneration may provide benefits for those waiting for bone marrow transplants by activating their own healthy cells.” ![]()

Preclinical research has revealed a treatment that might preserve normal hematopoietic function in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found that AML suppresses adipocytes in the bone marrow, which leads to imbalanced regulation of endogenous hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and impaired myelo-erythroid maturation.

However, a PPARγ agonist can induce adipogenesis, which suppresses AML cells and stimulates the regeneration of healthy blood cells.

Researchers reported these findings in Nature Cell Biology.

The team found that adipocytes in the bone marrow support myelo-erythroid maturation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. But AML has a negative effect on the maturation of adipocytes, which explains why deficient myelo-erythropoiesis is “a consistent feature” of AML.

The researchers also found that pro-adipogenesis therapy—treatment with the PPARγ agonist GW1929—protects healthy myelo-erythropoiesis and limits leukemic self-renewal.

“Our approach represents a different way of looking at leukemia and considers the entire bone marrow as an ecosystem, rather than the traditional approach of studying and trying to directly kill the diseased cells themselves,” said study author Allison Boyd, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

“These traditional approaches have not delivered enough new therapeutic options for patients. The standard of care for this disease hasn’t changed in several decades.”

“The focus of chemotherapy and existing standard of care is on killing cancer cells, but, instead, we took a completely different approach, which changes the environment the cancer cells live in,” said study author Mick Bhatia, PhD, of McMaster University.

“This not only suppressed the ‘bad’ cancer cells but also bolstered the ‘good’ healthy cells, allowing them to regenerate in the new drug-induced environment. The fact that we can target one cell type in one tissue using an existing drug makes us excited about the possibilities of testing this in patients.”

“We can envision this becoming a potential new therapeutic approach that can either be added to existing treatments or even replace others in the near future. The fact that this drug activates blood regeneration may provide benefits for those waiting for bone marrow transplants by activating their own healthy cells.” ![]()

Preclinical research has revealed a treatment that might preserve normal hematopoietic function in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found that AML suppresses adipocytes in the bone marrow, which leads to imbalanced regulation of endogenous hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and impaired myelo-erythroid maturation.

However, a PPARγ agonist can induce adipogenesis, which suppresses AML cells and stimulates the regeneration of healthy blood cells.

Researchers reported these findings in Nature Cell Biology.

The team found that adipocytes in the bone marrow support myelo-erythroid maturation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. But AML has a negative effect on the maturation of adipocytes, which explains why deficient myelo-erythropoiesis is “a consistent feature” of AML.

The researchers also found that pro-adipogenesis therapy—treatment with the PPARγ agonist GW1929—protects healthy myelo-erythropoiesis and limits leukemic self-renewal.

“Our approach represents a different way of looking at leukemia and considers the entire bone marrow as an ecosystem, rather than the traditional approach of studying and trying to directly kill the diseased cells themselves,” said study author Allison Boyd, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

“These traditional approaches have not delivered enough new therapeutic options for patients. The standard of care for this disease hasn’t changed in several decades.”

“The focus of chemotherapy and existing standard of care is on killing cancer cells, but, instead, we took a completely different approach, which changes the environment the cancer cells live in,” said study author Mick Bhatia, PhD, of McMaster University.

“This not only suppressed the ‘bad’ cancer cells but also bolstered the ‘good’ healthy cells, allowing them to regenerate in the new drug-induced environment. The fact that we can target one cell type in one tissue using an existing drug makes us excited about the possibilities of testing this in patients.”

“We can envision this becoming a potential new therapeutic approach that can either be added to existing treatments or even replace others in the near future. The fact that this drug activates blood regeneration may provide benefits for those waiting for bone marrow transplants by activating their own healthy cells.” ![]()

Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: Is ‘less is more’ the right approach?

Surgeons treated 95% of preoperatively diagnosed cases of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma with total thyroidectomy, compared with only 69% of postoperatively diagnosed cases, in to a single-center retrospective cohort study.

“During the study period, thyroid lobectomy was an acceptable alternative endorsed by the American Thyroid Association,” said Susan C. Pitt, MD, and her associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “Nonetheless, documentation rarely stated that [thyroid lobectomy] was discussed as an option. Whether this finding indicates a true lack of discussion or a deficit in documentation is unclear, but emphasizes the need to improve the quality of the [electronic health record] and capture all elements of shared decision-making.”

Papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMC) measure 1 cm or less, affect up to a third of adults, and explain about half of the recent rise in rates of papillary thyroid cancer, the investigators stated. Most cases are found incidentally and there is no evidence that they contribute to a rise in mortality, which stands at about 0.5 deaths per 100,000 diagnoses of thyroid carcinoma. Accordingly, in 2015, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) endorsed active surveillance and thyroid lobectomy as acceptable management strategies for most patients with PTMC (Thyroid. 2016 Jan 12;26[1]:1-133).

“The pendulum for the ATA guidelines has swung back and forth,” Dr. Pitt said in an interview. “I think the current 2015 ATA guidelines are still controversial – some surgeons and endocrinologists think we have swung too far [in the other direction]. Moving the field from total thyroidectomy to active surveillance is a big jump. Understanding the factors underlying current decisions will help us to implement less extensive management, like lobectomy and active surveillance.”

To do that, Dr. Pitt and her associates reviewed medical records from 125 patients with PTMC treated at the University of Wisconsin between 2008 and 2016. Most of the patients (90%) were white, 85% were female, average age was 50 years, and nearly all had classic or follicular-variant disease. Only 27% of patients underwent thyroid lobectomy; the rest underwent total thyroidectomy. Furthermore, among 19 patients diagnosed preoperatively, 95% underwent total thyroidectomy and 21% had a complication, including one (5%) case of permanent hypocalcemia that less extensive surgery might have avoided (J Surg Res. 2017;218:237-45).

“In all cases, documentation indicated that these preoperatively diagnosed patients followed the surgeon’s recommendation regarding the extent of surgery,” the researchers wrote. Surgeons cited various reasons for recommending total thyroidectomy, including – in about 20% of cases – a belief that it was the recommended treatment.

Only one of the 19 preoperatively diagnosed patients had a documented discussion of thyroid lobectomy, the researchers found.

While physicians might be concerned about recurrence or other “downstream” outcomes of a less-is-more approach to PTMC, Dr. Pitt noted that, in a recent large study, only 3.4% of these tumors metastasized over 10 years (World J Surg. 2010 Jan;34[1]:28-35).

“At the same time, I think that we have a better sense [that] patient-centered outcomes after thyroidectomy, such as health-related quality of life, swallowing, and voice outcomes, can be worse after a total thyroidectomy,” she added.

As surgical and medical therapies expand for PTMC and other nonmalignant diseases, it becomes increasingly vital that surgeons and patients undertake shared decision-making, she said. At the University of Wisconsin, physicians can enter free text in the EHR to document such discussions. She gave an example of how she does that: “‘Total thyroidectomy and lobectomy are both appropriate approaches for Ms. Smith. We discussed these options at length, including X, Y, and Z. Given Mrs. Smith’s (strong) preference to avoid X, we will proceed with a lobectomy.”

In her own practice, Dr. Pitt added, “when I look back at a note, I want to know what the decision was, and why it was made.”

Shared decision-making differs from informed consent by focusing on patient preferences, she noted. “I have used my notes in the operating room to help me decide what to do. I can look back and have a window into our conversation and what an individual patient values.” For PTMC, shared decisions should focus less on cancer risk and more on quality of life and outcomes a year later, she said.

“Patients don’t die from PTMC, and most live longer than the age-matched population. Given the risks of more extensive surgery and our current data on surgical and patient-centered outcomes, I think that thyroid lobectomy should be the initial treatment for most patients with PTMC, and surgeons should help their patients make informed decisions,” Dr. Pitt said.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Surgeons treated 95% of preoperatively diagnosed cases of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma with total thyroidectomy, compared with only 69% of postoperatively diagnosed cases, in to a single-center retrospective cohort study.

“During the study period, thyroid lobectomy was an acceptable alternative endorsed by the American Thyroid Association,” said Susan C. Pitt, MD, and her associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “Nonetheless, documentation rarely stated that [thyroid lobectomy] was discussed as an option. Whether this finding indicates a true lack of discussion or a deficit in documentation is unclear, but emphasizes the need to improve the quality of the [electronic health record] and capture all elements of shared decision-making.”

Papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMC) measure 1 cm or less, affect up to a third of adults, and explain about half of the recent rise in rates of papillary thyroid cancer, the investigators stated. Most cases are found incidentally and there is no evidence that they contribute to a rise in mortality, which stands at about 0.5 deaths per 100,000 diagnoses of thyroid carcinoma. Accordingly, in 2015, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) endorsed active surveillance and thyroid lobectomy as acceptable management strategies for most patients with PTMC (Thyroid. 2016 Jan 12;26[1]:1-133).

“The pendulum for the ATA guidelines has swung back and forth,” Dr. Pitt said in an interview. “I think the current 2015 ATA guidelines are still controversial – some surgeons and endocrinologists think we have swung too far [in the other direction]. Moving the field from total thyroidectomy to active surveillance is a big jump. Understanding the factors underlying current decisions will help us to implement less extensive management, like lobectomy and active surveillance.”

To do that, Dr. Pitt and her associates reviewed medical records from 125 patients with PTMC treated at the University of Wisconsin between 2008 and 2016. Most of the patients (90%) were white, 85% were female, average age was 50 years, and nearly all had classic or follicular-variant disease. Only 27% of patients underwent thyroid lobectomy; the rest underwent total thyroidectomy. Furthermore, among 19 patients diagnosed preoperatively, 95% underwent total thyroidectomy and 21% had a complication, including one (5%) case of permanent hypocalcemia that less extensive surgery might have avoided (J Surg Res. 2017;218:237-45).

“In all cases, documentation indicated that these preoperatively diagnosed patients followed the surgeon’s recommendation regarding the extent of surgery,” the researchers wrote. Surgeons cited various reasons for recommending total thyroidectomy, including – in about 20% of cases – a belief that it was the recommended treatment.

Only one of the 19 preoperatively diagnosed patients had a documented discussion of thyroid lobectomy, the researchers found.

While physicians might be concerned about recurrence or other “downstream” outcomes of a less-is-more approach to PTMC, Dr. Pitt noted that, in a recent large study, only 3.4% of these tumors metastasized over 10 years (World J Surg. 2010 Jan;34[1]:28-35).

“At the same time, I think that we have a better sense [that] patient-centered outcomes after thyroidectomy, such as health-related quality of life, swallowing, and voice outcomes, can be worse after a total thyroidectomy,” she added.

As surgical and medical therapies expand for PTMC and other nonmalignant diseases, it becomes increasingly vital that surgeons and patients undertake shared decision-making, she said. At the University of Wisconsin, physicians can enter free text in the EHR to document such discussions. She gave an example of how she does that: “‘Total thyroidectomy and lobectomy are both appropriate approaches for Ms. Smith. We discussed these options at length, including X, Y, and Z. Given Mrs. Smith’s (strong) preference to avoid X, we will proceed with a lobectomy.”

In her own practice, Dr. Pitt added, “when I look back at a note, I want to know what the decision was, and why it was made.”

Shared decision-making differs from informed consent by focusing on patient preferences, she noted. “I have used my notes in the operating room to help me decide what to do. I can look back and have a window into our conversation and what an individual patient values.” For PTMC, shared decisions should focus less on cancer risk and more on quality of life and outcomes a year later, she said.

“Patients don’t die from PTMC, and most live longer than the age-matched population. Given the risks of more extensive surgery and our current data on surgical and patient-centered outcomes, I think that thyroid lobectomy should be the initial treatment for most patients with PTMC, and surgeons should help their patients make informed decisions,” Dr. Pitt said.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Surgeons treated 95% of preoperatively diagnosed cases of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma with total thyroidectomy, compared with only 69% of postoperatively diagnosed cases, in to a single-center retrospective cohort study.

“During the study period, thyroid lobectomy was an acceptable alternative endorsed by the American Thyroid Association,” said Susan C. Pitt, MD, and her associates at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “Nonetheless, documentation rarely stated that [thyroid lobectomy] was discussed as an option. Whether this finding indicates a true lack of discussion or a deficit in documentation is unclear, but emphasizes the need to improve the quality of the [electronic health record] and capture all elements of shared decision-making.”

Papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMC) measure 1 cm or less, affect up to a third of adults, and explain about half of the recent rise in rates of papillary thyroid cancer, the investigators stated. Most cases are found incidentally and there is no evidence that they contribute to a rise in mortality, which stands at about 0.5 deaths per 100,000 diagnoses of thyroid carcinoma. Accordingly, in 2015, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) endorsed active surveillance and thyroid lobectomy as acceptable management strategies for most patients with PTMC (Thyroid. 2016 Jan 12;26[1]:1-133).

“The pendulum for the ATA guidelines has swung back and forth,” Dr. Pitt said in an interview. “I think the current 2015 ATA guidelines are still controversial – some surgeons and endocrinologists think we have swung too far [in the other direction]. Moving the field from total thyroidectomy to active surveillance is a big jump. Understanding the factors underlying current decisions will help us to implement less extensive management, like lobectomy and active surveillance.”

To do that, Dr. Pitt and her associates reviewed medical records from 125 patients with PTMC treated at the University of Wisconsin between 2008 and 2016. Most of the patients (90%) were white, 85% were female, average age was 50 years, and nearly all had classic or follicular-variant disease. Only 27% of patients underwent thyroid lobectomy; the rest underwent total thyroidectomy. Furthermore, among 19 patients diagnosed preoperatively, 95% underwent total thyroidectomy and 21% had a complication, including one (5%) case of permanent hypocalcemia that less extensive surgery might have avoided (J Surg Res. 2017;218:237-45).

“In all cases, documentation indicated that these preoperatively diagnosed patients followed the surgeon’s recommendation regarding the extent of surgery,” the researchers wrote. Surgeons cited various reasons for recommending total thyroidectomy, including – in about 20% of cases – a belief that it was the recommended treatment.

Only one of the 19 preoperatively diagnosed patients had a documented discussion of thyroid lobectomy, the researchers found.

While physicians might be concerned about recurrence or other “downstream” outcomes of a less-is-more approach to PTMC, Dr. Pitt noted that, in a recent large study, only 3.4% of these tumors metastasized over 10 years (World J Surg. 2010 Jan;34[1]:28-35).

“At the same time, I think that we have a better sense [that] patient-centered outcomes after thyroidectomy, such as health-related quality of life, swallowing, and voice outcomes, can be worse after a total thyroidectomy,” she added.

As surgical and medical therapies expand for PTMC and other nonmalignant diseases, it becomes increasingly vital that surgeons and patients undertake shared decision-making, she said. At the University of Wisconsin, physicians can enter free text in the EHR to document such discussions. She gave an example of how she does that: “‘Total thyroidectomy and lobectomy are both appropriate approaches for Ms. Smith. We discussed these options at length, including X, Y, and Z. Given Mrs. Smith’s (strong) preference to avoid X, we will proceed with a lobectomy.”

In her own practice, Dr. Pitt added, “when I look back at a note, I want to know what the decision was, and why it was made.”

Shared decision-making differs from informed consent by focusing on patient preferences, she noted. “I have used my notes in the operating room to help me decide what to do. I can look back and have a window into our conversation and what an individual patient values.” For PTMC, shared decisions should focus less on cancer risk and more on quality of life and outcomes a year later, she said.

“Patients don’t die from PTMC, and most live longer than the age-matched population. Given the risks of more extensive surgery and our current data on surgical and patient-centered outcomes, I think that thyroid lobectomy should be the initial treatment for most patients with PTMC, and surgeons should help their patients make informed decisions,” Dr. Pitt said.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Nearly all patients with a preoperative diagnosis of PTMC underwent total thyroidectomy, usually at their surgeon’s recommendation.

Major finding: 95% of preoperatively diagnosed patients underwent total thyroidectomy, versus 69% of those diagnosed postoperatively (P = .02). A discussion of thyroid lobectomy was documented in only one preoperatively diagnosed case.

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 125 patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Reminder spurs flu vaccination of chronic disease patients

and because their parents are unaware influenza is risky for their children, reported Gilat Livni, MD, and Alina Wainstein, MD, of Tel Aviv University and their associates.

The investigators surveyed 186 parents of children attending a cardiology institute in Israel regarding flu vaccination. Over a third (37%) of the children had received a flu vaccine during the last flu season. Those who had been vaccinated were significantly more likely to have parents and siblings who were vaccinated (P less than .01).The mean age of the children was 8 years.

The main underlying cardiac diseases in the 186 children were left-to-right shunt defect in 31%, obstructive lesions in 30%, and cyanotic defect in 16%. Other cardiac abnormalities included valvular insufficiency in 11%, cardiomyopathy in 8%, and complete atrioventricular block in 4%.

More than half of parents (59%) reported that a pediatrician had recommended that their child get a flu vaccine; of these parents, 53% complied. Only 13% of parents who did not get such a recommendation had their children vaccinated – a statistically significant difference. Findings were similar regarding recommendations from pediatric cardiologists. “The failure of parents to receive information or advice from a physician regarding vaccination was strongly inversely related to vaccination of the child,” the investigators concluded.

“Our results emphasize the need to raise awareness among physicians and other medical health care personnel dealing with children with heart disease of the importance of properly counseling parents regarding influenza vaccination. Recommending the vaccine should be made part of routine patient visits in fall and winter,” concluded Dr. Livni, Dr. Wainstein, and associates.

The full text is available online (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017 Nov;36[11]: e268-71. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001579).

and because their parents are unaware influenza is risky for their children, reported Gilat Livni, MD, and Alina Wainstein, MD, of Tel Aviv University and their associates.

The investigators surveyed 186 parents of children attending a cardiology institute in Israel regarding flu vaccination. Over a third (37%) of the children had received a flu vaccine during the last flu season. Those who had been vaccinated were significantly more likely to have parents and siblings who were vaccinated (P less than .01).The mean age of the children was 8 years.

The main underlying cardiac diseases in the 186 children were left-to-right shunt defect in 31%, obstructive lesions in 30%, and cyanotic defect in 16%. Other cardiac abnormalities included valvular insufficiency in 11%, cardiomyopathy in 8%, and complete atrioventricular block in 4%.

More than half of parents (59%) reported that a pediatrician had recommended that their child get a flu vaccine; of these parents, 53% complied. Only 13% of parents who did not get such a recommendation had their children vaccinated – a statistically significant difference. Findings were similar regarding recommendations from pediatric cardiologists. “The failure of parents to receive information or advice from a physician regarding vaccination was strongly inversely related to vaccination of the child,” the investigators concluded.

“Our results emphasize the need to raise awareness among physicians and other medical health care personnel dealing with children with heart disease of the importance of properly counseling parents regarding influenza vaccination. Recommending the vaccine should be made part of routine patient visits in fall and winter,” concluded Dr. Livni, Dr. Wainstein, and associates.

The full text is available online (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017 Nov;36[11]: e268-71. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001579).

and because their parents are unaware influenza is risky for their children, reported Gilat Livni, MD, and Alina Wainstein, MD, of Tel Aviv University and their associates.

The investigators surveyed 186 parents of children attending a cardiology institute in Israel regarding flu vaccination. Over a third (37%) of the children had received a flu vaccine during the last flu season. Those who had been vaccinated were significantly more likely to have parents and siblings who were vaccinated (P less than .01).The mean age of the children was 8 years.

The main underlying cardiac diseases in the 186 children were left-to-right shunt defect in 31%, obstructive lesions in 30%, and cyanotic defect in 16%. Other cardiac abnormalities included valvular insufficiency in 11%, cardiomyopathy in 8%, and complete atrioventricular block in 4%.

More than half of parents (59%) reported that a pediatrician had recommended that their child get a flu vaccine; of these parents, 53% complied. Only 13% of parents who did not get such a recommendation had their children vaccinated – a statistically significant difference. Findings were similar regarding recommendations from pediatric cardiologists. “The failure of parents to receive information or advice from a physician regarding vaccination was strongly inversely related to vaccination of the child,” the investigators concluded.

“Our results emphasize the need to raise awareness among physicians and other medical health care personnel dealing with children with heart disease of the importance of properly counseling parents regarding influenza vaccination. Recommending the vaccine should be made part of routine patient visits in fall and winter,” concluded Dr. Livni, Dr. Wainstein, and associates.

The full text is available online (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017 Nov;36[11]: e268-71. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001579).

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

Low risk of bariatric surgery complications in IBD

Bariatric surgery is safe and feasible in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with a low risk of postoperative complications vs. controls, according to results of a recent cohort study.

Besides a significantly higher risk of perioperative small-bowel obstruction and a 1-day increase in hospital stay, outcomes were comparable between patients with IBD and controls (Obes Surg. 2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2955-4).

Limitations of the retrospective study, according to the authors, included a potential underestimation of short-term postoperative complications, since the data set used in the study was limited to in-hospital stays and would not include events occurring after discharge.

Nevertheless, “our data show that it is reasonable to carefully proceed with bariatric interventions in obese IBD patients, especially those who are at higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and drastic need for weight reduction, to accrue benefits of weight loss,” wrote Fateh Bazerbachi, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. and his coauthors.

Bariatric surgery is the “most effective solution” for obesity, and “appropriate candidates should not be deprived of this important, potentially life-saving procedure, if the intervention is deemed acceptably safe,” Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues noted.

Their cohort study included data for 314,864 adult patients in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample who underwent bariatric surgery between 2011 and 2013. Of that group, 790 patients had underlying IBD (459 Crohn’s disease, 331 ulcerative colitis). Remaining patients made up the comparator group.

The primary outcomes evaluated in the study included risks of systemic and technical complications. Risk of perioperative small-bowel obstruction was significantly higher in the IBD group (adjusted odds ratio, 4.0; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-7.4). However, the rates of other complications were similar between the two groups, data show.

Secondary outcomes in the study included length of hospital stay and mortality. Mean length of hospital stay was 3.4 days for IBD patients, vs. 2.5 days for the comparison group (P = .01), according to the report. Mortality was 0.25% for controls, while no deaths were reported in the IBD group.

In the future, bariatric surgeons may face increasing demand to treat IBD patients, given the increasing prevalence of obesity in the IBD patient population, Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues said.

Some surgeons may believe that bariatric intervention is more challenging in IBD patients, in part because of the underlying inflammatory state that might interfere with healing of wounds and recovery of bowel motility, they said. Bariatric surgery, however, can reduce body mass index, which in turn might make future IBD surgeries less challenging.

Another potential advantage is reduction in cardiovascular risk, which is elevated in IBD patients both due to obesity as well as the IBD condition, they added.

“Further studies are certainly needed to examine long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery on IBD and to determine whether cardiovascular mortality is reduced from these interventions in this susceptible cohort of obese IBD patients,” Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues wrote.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

Bariatric surgery is safe and feasible in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with a low risk of postoperative complications vs. controls, according to results of a recent cohort study.

Besides a significantly higher risk of perioperative small-bowel obstruction and a 1-day increase in hospital stay, outcomes were comparable between patients with IBD and controls (Obes Surg. 2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2955-4).

Limitations of the retrospective study, according to the authors, included a potential underestimation of short-term postoperative complications, since the data set used in the study was limited to in-hospital stays and would not include events occurring after discharge.

Nevertheless, “our data show that it is reasonable to carefully proceed with bariatric interventions in obese IBD patients, especially those who are at higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and drastic need for weight reduction, to accrue benefits of weight loss,” wrote Fateh Bazerbachi, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. and his coauthors.

Bariatric surgery is the “most effective solution” for obesity, and “appropriate candidates should not be deprived of this important, potentially life-saving procedure, if the intervention is deemed acceptably safe,” Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues noted.

Their cohort study included data for 314,864 adult patients in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample who underwent bariatric surgery between 2011 and 2013. Of that group, 790 patients had underlying IBD (459 Crohn’s disease, 331 ulcerative colitis). Remaining patients made up the comparator group.

The primary outcomes evaluated in the study included risks of systemic and technical complications. Risk of perioperative small-bowel obstruction was significantly higher in the IBD group (adjusted odds ratio, 4.0; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-7.4). However, the rates of other complications were similar between the two groups, data show.

Secondary outcomes in the study included length of hospital stay and mortality. Mean length of hospital stay was 3.4 days for IBD patients, vs. 2.5 days for the comparison group (P = .01), according to the report. Mortality was 0.25% for controls, while no deaths were reported in the IBD group.

In the future, bariatric surgeons may face increasing demand to treat IBD patients, given the increasing prevalence of obesity in the IBD patient population, Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues said.

Some surgeons may believe that bariatric intervention is more challenging in IBD patients, in part because of the underlying inflammatory state that might interfere with healing of wounds and recovery of bowel motility, they said. Bariatric surgery, however, can reduce body mass index, which in turn might make future IBD surgeries less challenging.

Another potential advantage is reduction in cardiovascular risk, which is elevated in IBD patients both due to obesity as well as the IBD condition, they added.

“Further studies are certainly needed to examine long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery on IBD and to determine whether cardiovascular mortality is reduced from these interventions in this susceptible cohort of obese IBD patients,” Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues wrote.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

Bariatric surgery is safe and feasible in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with a low risk of postoperative complications vs. controls, according to results of a recent cohort study.

Besides a significantly higher risk of perioperative small-bowel obstruction and a 1-day increase in hospital stay, outcomes were comparable between patients with IBD and controls (Obes Surg. 2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2955-4).

Limitations of the retrospective study, according to the authors, included a potential underestimation of short-term postoperative complications, since the data set used in the study was limited to in-hospital stays and would not include events occurring after discharge.

Nevertheless, “our data show that it is reasonable to carefully proceed with bariatric interventions in obese IBD patients, especially those who are at higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and drastic need for weight reduction, to accrue benefits of weight loss,” wrote Fateh Bazerbachi, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. and his coauthors.

Bariatric surgery is the “most effective solution” for obesity, and “appropriate candidates should not be deprived of this important, potentially life-saving procedure, if the intervention is deemed acceptably safe,” Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues noted.

Their cohort study included data for 314,864 adult patients in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample who underwent bariatric surgery between 2011 and 2013. Of that group, 790 patients had underlying IBD (459 Crohn’s disease, 331 ulcerative colitis). Remaining patients made up the comparator group.

The primary outcomes evaluated in the study included risks of systemic and technical complications. Risk of perioperative small-bowel obstruction was significantly higher in the IBD group (adjusted odds ratio, 4.0; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-7.4). However, the rates of other complications were similar between the two groups, data show.

Secondary outcomes in the study included length of hospital stay and mortality. Mean length of hospital stay was 3.4 days for IBD patients, vs. 2.5 days for the comparison group (P = .01), according to the report. Mortality was 0.25% for controls, while no deaths were reported in the IBD group.

In the future, bariatric surgeons may face increasing demand to treat IBD patients, given the increasing prevalence of obesity in the IBD patient population, Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues said.

Some surgeons may believe that bariatric intervention is more challenging in IBD patients, in part because of the underlying inflammatory state that might interfere with healing of wounds and recovery of bowel motility, they said. Bariatric surgery, however, can reduce body mass index, which in turn might make future IBD surgeries less challenging.

Another potential advantage is reduction in cardiovascular risk, which is elevated in IBD patients both due to obesity as well as the IBD condition, they added.

“Further studies are certainly needed to examine long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery on IBD and to determine whether cardiovascular mortality is reduced from these interventions in this susceptible cohort of obese IBD patients,” Dr. Bazerbachi and his colleagues wrote.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM OBESITY SURGERY

Key clinical point: Watch for perioperative small-bowel obstruction in IBD patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

Major finding: IBD patients had a higher risk of perioperative small bowel obstruction (adjusted odds ratio, 4.0; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-7.4) and a 1-day increase in hospital stay (P = .01), compared with controls.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of Nationwide Inpatient Sample data including 790 patients with underlying IBD.

Disclosures: The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

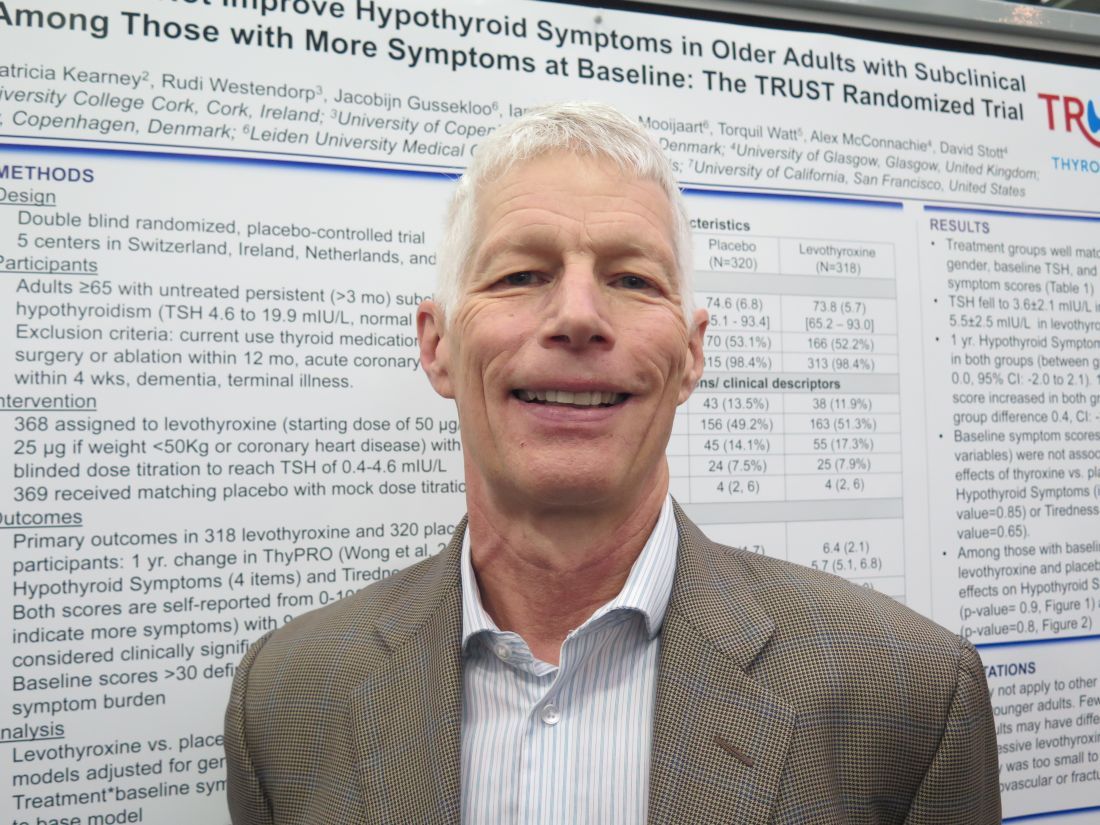

Symptoms fail to predict benefit of hormone therapy in older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism

VICTORIA, B.C. – , according to findings from a study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

“In the U.S., individuals are frequently treated either for just a number – just because their thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated – or for nonspecific hypothyroid-type symptoms, such as weight gain, cold intolerance, and such. It’s extremely common,” lead investigator Douglas Bauer, MD, professor and internist at the University of California, San Francisco, commented in an interview.

“On average, this study suggests that you shouldn’t be using hypothyroid-type symptomatology to treat subclinical hypothyroidism,” he said, while also acknowledging that not writing that prescription can be challenging. “It’s hard to do nothing, I know.”

Dr. Bauer and his coinvestigators performed a subgroup analysis of the randomized controlled TRUST trial (Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Subclinical Hypothyroidism), conducted in Switzerland, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. In the trial, 737 adults aged 65 years or older with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level, 4.60-19.99 mIU/L, with normal free thyroxine level) were given either levothyroxine or placebo on a double-blind basis.

Results for the entire trial population, previously reported, showed that at 1 year, patient-reported symptoms on a thyroid-specific quality-of-life questionnaire had improved by a similar extent in both groups, with no significant differences between them (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2534-44).

The new analysis focused on two subgroups that might be especially expected to benefit: 132 patients with a hypothyroid symptoms score greater than 30 on a 100-point scale and 209 patients with a tiredness score greater than 30 on a 100-point scale.

Results reported in a poster session showed that at 1 year, scores had improved by about 10 points with levothyroxine and placebo alike, with no significant difference, in both the group with higher hypothyroid symptoms scores (P = .90) and the group with higher tiredness scores (P = .80).

“This provides additional evidence that it’s unlikely that the treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, at least in this population, is going to lead to symptomatic improvement,” Dr. Bauer commented.

“I would speculate that we’ve overestimated the benefit [of thyroid hormone therapy] on symptoms based on the fact that previous studies haven’t been blinded,” he said, noting that the TRUST trial used a rigorous blinding protocol, even going so far as to change the appearance of placebo pills to convince patients in the placebo group that their dose was being titrated.

A potential criticism is that the treatment was not aggressive enough, with patients in the levothyroxine group achieving a mean TSH level of 3.6 mIU/L, according to Dr. Bauer. “I think many people treating with thyroxine would like to see this TSH fall into the 2 mIU/L to 3 mIU/L range,” he acknowledged.

Taken together, the trial’s overall and subgroup findings do not rule out potential benefit for certain patients, he cautioned. For example, patients with very high symptom burden and patients with baseline TSH levels greater than 10 mIU/L were too few for separate analysis, and younger adults were not included at all.

Additionally, treatment impact on other important clinical outcomes – cardiovascular events and fractures – could not be assessed in TRUST because of insufficient enrollment.

Dr. Bauer disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was funded by the European Union, Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Heart Foundation, and Velux Stiftung. Merck supplied study drug.

VICTORIA, B.C. – , according to findings from a study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

“In the U.S., individuals are frequently treated either for just a number – just because their thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated – or for nonspecific hypothyroid-type symptoms, such as weight gain, cold intolerance, and such. It’s extremely common,” lead investigator Douglas Bauer, MD, professor and internist at the University of California, San Francisco, commented in an interview.

“On average, this study suggests that you shouldn’t be using hypothyroid-type symptomatology to treat subclinical hypothyroidism,” he said, while also acknowledging that not writing that prescription can be challenging. “It’s hard to do nothing, I know.”

Dr. Bauer and his coinvestigators performed a subgroup analysis of the randomized controlled TRUST trial (Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Subclinical Hypothyroidism), conducted in Switzerland, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. In the trial, 737 adults aged 65 years or older with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level, 4.60-19.99 mIU/L, with normal free thyroxine level) were given either levothyroxine or placebo on a double-blind basis.

Results for the entire trial population, previously reported, showed that at 1 year, patient-reported symptoms on a thyroid-specific quality-of-life questionnaire had improved by a similar extent in both groups, with no significant differences between them (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2534-44).

The new analysis focused on two subgroups that might be especially expected to benefit: 132 patients with a hypothyroid symptoms score greater than 30 on a 100-point scale and 209 patients with a tiredness score greater than 30 on a 100-point scale.

Results reported in a poster session showed that at 1 year, scores had improved by about 10 points with levothyroxine and placebo alike, with no significant difference, in both the group with higher hypothyroid symptoms scores (P = .90) and the group with higher tiredness scores (P = .80).

“This provides additional evidence that it’s unlikely that the treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, at least in this population, is going to lead to symptomatic improvement,” Dr. Bauer commented.

“I would speculate that we’ve overestimated the benefit [of thyroid hormone therapy] on symptoms based on the fact that previous studies haven’t been blinded,” he said, noting that the TRUST trial used a rigorous blinding protocol, even going so far as to change the appearance of placebo pills to convince patients in the placebo group that their dose was being titrated.

A potential criticism is that the treatment was not aggressive enough, with patients in the levothyroxine group achieving a mean TSH level of 3.6 mIU/L, according to Dr. Bauer. “I think many people treating with thyroxine would like to see this TSH fall into the 2 mIU/L to 3 mIU/L range,” he acknowledged.

Taken together, the trial’s overall and subgroup findings do not rule out potential benefit for certain patients, he cautioned. For example, patients with very high symptom burden and patients with baseline TSH levels greater than 10 mIU/L were too few for separate analysis, and younger adults were not included at all.

Additionally, treatment impact on other important clinical outcomes – cardiovascular events and fractures – could not be assessed in TRUST because of insufficient enrollment.

Dr. Bauer disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was funded by the European Union, Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Heart Foundation, and Velux Stiftung. Merck supplied study drug.

VICTORIA, B.C. – , according to findings from a study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

“In the U.S., individuals are frequently treated either for just a number – just because their thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated – or for nonspecific hypothyroid-type symptoms, such as weight gain, cold intolerance, and such. It’s extremely common,” lead investigator Douglas Bauer, MD, professor and internist at the University of California, San Francisco, commented in an interview.

“On average, this study suggests that you shouldn’t be using hypothyroid-type symptomatology to treat subclinical hypothyroidism,” he said, while also acknowledging that not writing that prescription can be challenging. “It’s hard to do nothing, I know.”

Dr. Bauer and his coinvestigators performed a subgroup analysis of the randomized controlled TRUST trial (Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Subclinical Hypothyroidism), conducted in Switzerland, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. In the trial, 737 adults aged 65 years or older with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level, 4.60-19.99 mIU/L, with normal free thyroxine level) were given either levothyroxine or placebo on a double-blind basis.

Results for the entire trial population, previously reported, showed that at 1 year, patient-reported symptoms on a thyroid-specific quality-of-life questionnaire had improved by a similar extent in both groups, with no significant differences between them (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2534-44).

The new analysis focused on two subgroups that might be especially expected to benefit: 132 patients with a hypothyroid symptoms score greater than 30 on a 100-point scale and 209 patients with a tiredness score greater than 30 on a 100-point scale.

Results reported in a poster session showed that at 1 year, scores had improved by about 10 points with levothyroxine and placebo alike, with no significant difference, in both the group with higher hypothyroid symptoms scores (P = .90) and the group with higher tiredness scores (P = .80).

“This provides additional evidence that it’s unlikely that the treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism, at least in this population, is going to lead to symptomatic improvement,” Dr. Bauer commented.

“I would speculate that we’ve overestimated the benefit [of thyroid hormone therapy] on symptoms based on the fact that previous studies haven’t been blinded,” he said, noting that the TRUST trial used a rigorous blinding protocol, even going so far as to change the appearance of placebo pills to convince patients in the placebo group that their dose was being titrated.

A potential criticism is that the treatment was not aggressive enough, with patients in the levothyroxine group achieving a mean TSH level of 3.6 mIU/L, according to Dr. Bauer. “I think many people treating with thyroxine would like to see this TSH fall into the 2 mIU/L to 3 mIU/L range,” he acknowledged.

Taken together, the trial’s overall and subgroup findings do not rule out potential benefit for certain patients, he cautioned. For example, patients with very high symptom burden and patients with baseline TSH levels greater than 10 mIU/L were too few for separate analysis, and younger adults were not included at all.

Additionally, treatment impact on other important clinical outcomes – cardiovascular events and fractures – could not be assessed in TRUST because of insufficient enrollment.

Dr. Bauer disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was funded by the European Union, Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Heart Foundation, and Velux Stiftung. Merck supplied study drug.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point: Hypothyroid-type symptoms do not predict treatment benefit in older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism.

Major finding: Patients had statistically indistinguishable improvements at 1 year in hypothyroid symptoms scores (P = .90) and Tiredness scores (P = .80) whether given levothyroxine or placebo.

Data source: A subgroup analysis of older adults with subclinical hypothyroidism having higher baseline levels of overall hypothyroid symptoms (n = 132) or tiredness (n = 209) (TRUST trial).

Disclosures: Dr. Bauer disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. The trial was funded by the European Union, Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Heart Foundation, and Velux Stiftung. Merck supplied study drug.

Abnormal potassium plus suspected ACS spell trouble

BARCELONA – A serum potassium level of at least 5.0 mmol/L or 3.5 mmol/L or less at admission for suspected acute coronary syndrome is a red flag for increased risk of in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrest, according to a Swedish study of nearly 33,000 consecutive patients.

That’s true even if, as so often ultimately proves to be the case, the patient turns out not to have ACS, Jonas Faxén, MD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“This study highlights that, if you have a patient in the emergency department with a possible ACS and potassium imbalance, you should really be cautious,” Dr. Faxén said.

He reported on 32,955 consecutive patients admitted to Stockholm County hospitals for suspected ACS during 2006-2011 and thereby enrolled in the SWEDEHEART (Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) registry.

Overall in-hospital mortality was 2.7%. In-hospital cardiac arrest occurred in 1.5% of patients. New-onset atrial fibrillation occurred in 2.4% of patients. These key outcomes were compared between the reference group – defined as patients with an admission serum potassium of 3.5 to less than 4.0 mmol/L – and patients with an admission serum potassium above or below those cutoffs.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for 24 potential confounders, including demographics, presentation characteristics, main diagnosis, comorbid conditions, medications on admission, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, patients with a serum potassium of 5.0 to less than 5.5 mmol/L were at 1.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital mortality. Those with a potassium of 5.5 mmol/L or greater were at 2.3-fold increased risk.

In contrast, a low rather than a high serum potassium was an independent risk factor cardiac arrest. An admission potassium of 3.0 to less than 3.5 mmol/L carried a 1.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital cardiac arrest, while a potassium of less than 3.0 was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk.

A serum potassium below 3.0 mmol/L at admission also was associated with a 1.7-fold increased risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation.

These elevated risks of bad outcomes didn’t differ significantly between patients with ST-elevation MI, non-STEMI ACS, and those whose final diagnosis was not ACS, Dr. Faxén noted.

Session cochair David W. Walker, MD, medical director of the East Sussex (England) Healthcare NHS Trust, observed, “When I was a junior doctor I was always taught that when patients came onto coronary care we had to get their potassium to 4.5-5.0 mmol/L. I think you might want to change that advice now.”

“The implication would be that, if you intervene quickly in a patient with an abnormal potassium level, you might make a difference. Clearly, a potassium that’s too high is much worse than too low, since patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest can often be resuscitated,” Dr. Walker commented.

Dr. Faxén reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation and the Stockholm County Council.

BARCELONA – A serum potassium level of at least 5.0 mmol/L or 3.5 mmol/L or less at admission for suspected acute coronary syndrome is a red flag for increased risk of in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrest, according to a Swedish study of nearly 33,000 consecutive patients.

That’s true even if, as so often ultimately proves to be the case, the patient turns out not to have ACS, Jonas Faxén, MD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“This study highlights that, if you have a patient in the emergency department with a possible ACS and potassium imbalance, you should really be cautious,” Dr. Faxén said.

He reported on 32,955 consecutive patients admitted to Stockholm County hospitals for suspected ACS during 2006-2011 and thereby enrolled in the SWEDEHEART (Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) registry.

Overall in-hospital mortality was 2.7%. In-hospital cardiac arrest occurred in 1.5% of patients. New-onset atrial fibrillation occurred in 2.4% of patients. These key outcomes were compared between the reference group – defined as patients with an admission serum potassium of 3.5 to less than 4.0 mmol/L – and patients with an admission serum potassium above or below those cutoffs.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for 24 potential confounders, including demographics, presentation characteristics, main diagnosis, comorbid conditions, medications on admission, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, patients with a serum potassium of 5.0 to less than 5.5 mmol/L were at 1.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital mortality. Those with a potassium of 5.5 mmol/L or greater were at 2.3-fold increased risk.

In contrast, a low rather than a high serum potassium was an independent risk factor cardiac arrest. An admission potassium of 3.0 to less than 3.5 mmol/L carried a 1.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital cardiac arrest, while a potassium of less than 3.0 was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk.

A serum potassium below 3.0 mmol/L at admission also was associated with a 1.7-fold increased risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation.

These elevated risks of bad outcomes didn’t differ significantly between patients with ST-elevation MI, non-STEMI ACS, and those whose final diagnosis was not ACS, Dr. Faxén noted.

Session cochair David W. Walker, MD, medical director of the East Sussex (England) Healthcare NHS Trust, observed, “When I was a junior doctor I was always taught that when patients came onto coronary care we had to get their potassium to 4.5-5.0 mmol/L. I think you might want to change that advice now.”

“The implication would be that, if you intervene quickly in a patient with an abnormal potassium level, you might make a difference. Clearly, a potassium that’s too high is much worse than too low, since patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest can often be resuscitated,” Dr. Walker commented.

Dr. Faxén reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation and the Stockholm County Council.

BARCELONA – A serum potassium level of at least 5.0 mmol/L or 3.5 mmol/L or less at admission for suspected acute coronary syndrome is a red flag for increased risk of in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrest, according to a Swedish study of nearly 33,000 consecutive patients.

That’s true even if, as so often ultimately proves to be the case, the patient turns out not to have ACS, Jonas Faxén, MD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“This study highlights that, if you have a patient in the emergency department with a possible ACS and potassium imbalance, you should really be cautious,” Dr. Faxén said.

He reported on 32,955 consecutive patients admitted to Stockholm County hospitals for suspected ACS during 2006-2011 and thereby enrolled in the SWEDEHEART (Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies) registry.

Overall in-hospital mortality was 2.7%. In-hospital cardiac arrest occurred in 1.5% of patients. New-onset atrial fibrillation occurred in 2.4% of patients. These key outcomes were compared between the reference group – defined as patients with an admission serum potassium of 3.5 to less than 4.0 mmol/L – and patients with an admission serum potassium above or below those cutoffs.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for 24 potential confounders, including demographics, presentation characteristics, main diagnosis, comorbid conditions, medications on admission, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, patients with a serum potassium of 5.0 to less than 5.5 mmol/L were at 1.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital mortality. Those with a potassium of 5.5 mmol/L or greater were at 2.3-fold increased risk.

In contrast, a low rather than a high serum potassium was an independent risk factor cardiac arrest. An admission potassium of 3.0 to less than 3.5 mmol/L carried a 1.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital cardiac arrest, while a potassium of less than 3.0 was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk.

A serum potassium below 3.0 mmol/L at admission also was associated with a 1.7-fold increased risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation.

These elevated risks of bad outcomes didn’t differ significantly between patients with ST-elevation MI, non-STEMI ACS, and those whose final diagnosis was not ACS, Dr. Faxén noted.

Session cochair David W. Walker, MD, medical director of the East Sussex (England) Healthcare NHS Trust, observed, “When I was a junior doctor I was always taught that when patients came onto coronary care we had to get their potassium to 4.5-5.0 mmol/L. I think you might want to change that advice now.”

“The implication would be that, if you intervene quickly in a patient with an abnormal potassium level, you might make a difference. Clearly, a potassium that’s too high is much worse than too low, since patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest can often be resuscitated,” Dr. Walker commented.

Dr. Faxén reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation and the Stockholm County Council.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hyperkalemia of 5.0 to less than 5.5 mmol/L at admission for suspected ACS was associated with close to a twofold increased risk of in-hospital mortality.

Data source: The SWEDEHEART study is an ongoing prospective registry of patients with cardiovascular disease admitted to Stockholm County hospitals.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation and the Stockholm County Council.

From cells to socioeconomics, meth worsens HIV outcomes

BERLIN – From cellular pathology to socioeconomics, methamphetamine and HIV are a devastating combination.

Either one is enough to ruin a life on its own. But together they can become a fatal ouroboros, Jordi Blanch, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Congress. The drug sparks dangerous sexual behavior that ups HIV risk. It increases HIV-vulnerable receptors on immune cells, priming them for viral invasion. It interferes with the metabolism of antiretroviral drugs and grinds medication adherence into the dust.

And even when faced with the facts about these interactions with a serious disease, meth users find it almost impossible to leave the drug behind.

Methamphetamine was once almost exclusively a North American problem, said Dr. Blanch of the University of Barcelona. But in the last decade, the drug has jumped the pond, storming the beaches of Western Europe. Bolstered by imports from Asia, it’s now spreading eastward and down into Africa. Meth is challenging and surpassing alcohol as the drug of choice for HIV high-risk groups (particularly men who have sex with men). Like alcohol, it’s cheap and easy to find. Unlike alcohol, it delivers an incredibly potent, nearly instantaneous brain hit that amps up sexual desire and capacity while decreasing inhibition and executive function.

“When we look at the use of meth in the context of sexual relationships, it’s not hard to understand how it leads to all kinds of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV,” Dr. Blanch said.

A potent dopamine agonist, meth not only increases the neurotransmitter’s release, it blocks reuptake. It reduces the expression of dopamine transporters on the cell surface. At the same time, meth inhibits monoamine oxidase, normally a prime metabolizer. It even creates more dopamine: Methamphetamine increases the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine into the dopamine precursor, l-dopa.

The neurologic response to smoking crystal meth – still the most popular way of ingesting the drug – is practically instantaneous. “It’s a very fast and intense euphoric high that, as we know, can have a lot of really bad side effects, like anxiety, restlessness, and even psychosis,” Dr. Blanch said. Its other side effects, though, are what make meth such a potent driver of risky sexual behavior.

“Men who have sex with men use it because it dramatically facilitates sexual functioning. It allows them to have sex for much longer. It decreases pain sensation, so this makes it easier to engage in anal sex, which is likely to be unprotected,” Dr. Blanch said. At the same time, the drug decreases higher-order thinking and increases impulsivity, driving even more behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, including group sex and the use of alcohol and injectable drugs together.

It is not just a cognitive-behavioral problem, though. Animal studies have found some intriguing pathophysiologic links between HIV viral activity and meth.

“Meth actually facilitates the infection,” Dr. Blanch said. “The risk of getting it is much higher, and the risk of it progressing with a high viral load is much higher.”

A 2015 review paper by Ryan Colby Passaro and his associates touches on some of these animal models (J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 Sep;10[3]:477-86). One of the most intriguing is a mouse study, which found that methamphetamine upregulated the HIV-1 coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, not only on CD4+ T cells, but on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and, to some extent, astrocytes.

Cat and rhesus monkey data implicated this meth-related effect on CXCR4 and CCR5 as well. But the drug also was implicated in other cellular pathways – all of which serve to make immune cells more vulnerable to HIV attack. These findings support the observation that methamphetamine users with the disease frequently have higher viral loads than nonusers.

After a diagnosis, users may continue to use as a way of avoiding confronting their illness, or even to combat the accompanying physical fatigue, Dr. Blanch said. Like many illicit drug users, meth users often show poor compliance with medical follow-up and poor medication adherence. But even if they do take their antiretroviral medications, methamphetamine still has a way of exerting its power. Ritonavir and cobicistat both inhibit the metabolic pathway that breaks down methamphetamine; using meth with either of those drugs can increase meth concentrations by up to 10-fold, a combination that has killed many patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Blanch said, it’s terribly difficult for users to give up meth, even in the face of contracting such a serious illness.

“In the beginning, after a diagnosis, they may stop using for a while. But then many start again,” he said. “We see this in study after study. But we have not so many studies on how to treat these patients.”

Trials of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and of replacement therapy with amphetamines or methylphenidate, have had mixed results.

“In my own clinic, we try to explain these problems of the interaction of meth and HIV. We have tried even to motivate our patients to use just on the weekend, for example, but they didn’t accept that,” he said. “Usually, we end up trying to make an agreement that the patient will use as little as possible and let them know how much it interferes with their treatment. But in my clinical experience, it’s not so easy. It’s hard to make any change. … very difficult.”

Dr. Blanch had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – From cellular pathology to socioeconomics, methamphetamine and HIV are a devastating combination.

Either one is enough to ruin a life on its own. But together they can become a fatal ouroboros, Jordi Blanch, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Congress. The drug sparks dangerous sexual behavior that ups HIV risk. It increases HIV-vulnerable receptors on immune cells, priming them for viral invasion. It interferes with the metabolism of antiretroviral drugs and grinds medication adherence into the dust.

And even when faced with the facts about these interactions with a serious disease, meth users find it almost impossible to leave the drug behind.

Methamphetamine was once almost exclusively a North American problem, said Dr. Blanch of the University of Barcelona. But in the last decade, the drug has jumped the pond, storming the beaches of Western Europe. Bolstered by imports from Asia, it’s now spreading eastward and down into Africa. Meth is challenging and surpassing alcohol as the drug of choice for HIV high-risk groups (particularly men who have sex with men). Like alcohol, it’s cheap and easy to find. Unlike alcohol, it delivers an incredibly potent, nearly instantaneous brain hit that amps up sexual desire and capacity while decreasing inhibition and executive function.

“When we look at the use of meth in the context of sexual relationships, it’s not hard to understand how it leads to all kinds of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV,” Dr. Blanch said.

A potent dopamine agonist, meth not only increases the neurotransmitter’s release, it blocks reuptake. It reduces the expression of dopamine transporters on the cell surface. At the same time, meth inhibits monoamine oxidase, normally a prime metabolizer. It even creates more dopamine: Methamphetamine increases the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine into the dopamine precursor, l-dopa.

The neurologic response to smoking crystal meth – still the most popular way of ingesting the drug – is practically instantaneous. “It’s a very fast and intense euphoric high that, as we know, can have a lot of really bad side effects, like anxiety, restlessness, and even psychosis,” Dr. Blanch said. Its other side effects, though, are what make meth such a potent driver of risky sexual behavior.

“Men who have sex with men use it because it dramatically facilitates sexual functioning. It allows them to have sex for much longer. It decreases pain sensation, so this makes it easier to engage in anal sex, which is likely to be unprotected,” Dr. Blanch said. At the same time, the drug decreases higher-order thinking and increases impulsivity, driving even more behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, including group sex and the use of alcohol and injectable drugs together.

It is not just a cognitive-behavioral problem, though. Animal studies have found some intriguing pathophysiologic links between HIV viral activity and meth.

“Meth actually facilitates the infection,” Dr. Blanch said. “The risk of getting it is much higher, and the risk of it progressing with a high viral load is much higher.”

A 2015 review paper by Ryan Colby Passaro and his associates touches on some of these animal models (J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 Sep;10[3]:477-86). One of the most intriguing is a mouse study, which found that methamphetamine upregulated the HIV-1 coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, not only on CD4+ T cells, but on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and, to some extent, astrocytes.

Cat and rhesus monkey data implicated this meth-related effect on CXCR4 and CCR5 as well. But the drug also was implicated in other cellular pathways – all of which serve to make immune cells more vulnerable to HIV attack. These findings support the observation that methamphetamine users with the disease frequently have higher viral loads than nonusers.

After a diagnosis, users may continue to use as a way of avoiding confronting their illness, or even to combat the accompanying physical fatigue, Dr. Blanch said. Like many illicit drug users, meth users often show poor compliance with medical follow-up and poor medication adherence. But even if they do take their antiretroviral medications, methamphetamine still has a way of exerting its power. Ritonavir and cobicistat both inhibit the metabolic pathway that breaks down methamphetamine; using meth with either of those drugs can increase meth concentrations by up to 10-fold, a combination that has killed many patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Blanch said, it’s terribly difficult for users to give up meth, even in the face of contracting such a serious illness.

“In the beginning, after a diagnosis, they may stop using for a while. But then many start again,” he said. “We see this in study after study. But we have not so many studies on how to treat these patients.”

Trials of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and of replacement therapy with amphetamines or methylphenidate, have had mixed results.

“In my own clinic, we try to explain these problems of the interaction of meth and HIV. We have tried even to motivate our patients to use just on the weekend, for example, but they didn’t accept that,” he said. “Usually, we end up trying to make an agreement that the patient will use as little as possible and let them know how much it interferes with their treatment. But in my clinical experience, it’s not so easy. It’s hard to make any change. … very difficult.”

Dr. Blanch had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – From cellular pathology to socioeconomics, methamphetamine and HIV are a devastating combination.

Either one is enough to ruin a life on its own. But together they can become a fatal ouroboros, Jordi Blanch, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Congress. The drug sparks dangerous sexual behavior that ups HIV risk. It increases HIV-vulnerable receptors on immune cells, priming them for viral invasion. It interferes with the metabolism of antiretroviral drugs and grinds medication adherence into the dust.

And even when faced with the facts about these interactions with a serious disease, meth users find it almost impossible to leave the drug behind.

Methamphetamine was once almost exclusively a North American problem, said Dr. Blanch of the University of Barcelona. But in the last decade, the drug has jumped the pond, storming the beaches of Western Europe. Bolstered by imports from Asia, it’s now spreading eastward and down into Africa. Meth is challenging and surpassing alcohol as the drug of choice for HIV high-risk groups (particularly men who have sex with men). Like alcohol, it’s cheap and easy to find. Unlike alcohol, it delivers an incredibly potent, nearly instantaneous brain hit that amps up sexual desire and capacity while decreasing inhibition and executive function.

“When we look at the use of meth in the context of sexual relationships, it’s not hard to understand how it leads to all kinds of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV,” Dr. Blanch said.

A potent dopamine agonist, meth not only increases the neurotransmitter’s release, it blocks reuptake. It reduces the expression of dopamine transporters on the cell surface. At the same time, meth inhibits monoamine oxidase, normally a prime metabolizer. It even creates more dopamine: Methamphetamine increases the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine into the dopamine precursor, l-dopa.

The neurologic response to smoking crystal meth – still the most popular way of ingesting the drug – is practically instantaneous. “It’s a very fast and intense euphoric high that, as we know, can have a lot of really bad side effects, like anxiety, restlessness, and even psychosis,” Dr. Blanch said. Its other side effects, though, are what make meth such a potent driver of risky sexual behavior.

“Men who have sex with men use it because it dramatically facilitates sexual functioning. It allows them to have sex for much longer. It decreases pain sensation, so this makes it easier to engage in anal sex, which is likely to be unprotected,” Dr. Blanch said. At the same time, the drug decreases higher-order thinking and increases impulsivity, driving even more behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, including group sex and the use of alcohol and injectable drugs together.

It is not just a cognitive-behavioral problem, though. Animal studies have found some intriguing pathophysiologic links between HIV viral activity and meth.

“Meth actually facilitates the infection,” Dr. Blanch said. “The risk of getting it is much higher, and the risk of it progressing with a high viral load is much higher.”

A 2015 review paper by Ryan Colby Passaro and his associates touches on some of these animal models (J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 Sep;10[3]:477-86). One of the most intriguing is a mouse study, which found that methamphetamine upregulated the HIV-1 coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, not only on CD4+ T cells, but on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and, to some extent, astrocytes.

Cat and rhesus monkey data implicated this meth-related effect on CXCR4 and CCR5 as well. But the drug also was implicated in other cellular pathways – all of which serve to make immune cells more vulnerable to HIV attack. These findings support the observation that methamphetamine users with the disease frequently have higher viral loads than nonusers.

After a diagnosis, users may continue to use as a way of avoiding confronting their illness, or even to combat the accompanying physical fatigue, Dr. Blanch said. Like many illicit drug users, meth users often show poor compliance with medical follow-up and poor medication adherence. But even if they do take their antiretroviral medications, methamphetamine still has a way of exerting its power. Ritonavir and cobicistat both inhibit the metabolic pathway that breaks down methamphetamine; using meth with either of those drugs can increase meth concentrations by up to 10-fold, a combination that has killed many patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Blanch said, it’s terribly difficult for users to give up meth, even in the face of contracting such a serious illness.

“In the beginning, after a diagnosis, they may stop using for a while. But then many start again,” he said. “We see this in study after study. But we have not so many studies on how to treat these patients.”

Trials of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and of replacement therapy with amphetamines or methylphenidate, have had mixed results.

“In my own clinic, we try to explain these problems of the interaction of meth and HIV. We have tried even to motivate our patients to use just on the weekend, for example, but they didn’t accept that,” he said. “Usually, we end up trying to make an agreement that the patient will use as little as possible and let them know how much it interferes with their treatment. But in my clinical experience, it’s not so easy. It’s hard to make any change. … very difficult.”

Dr. Blanch had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WPA 2017

Many women have unprotected sex in year after bariatric surgery

More than 40% of reproductive-age women reported having unprotected sex in the year after undergoing bariatric surgery, despite recommendations to avoid pregnancy for at least a year, a new study finds. Another 4% of women reported trying to conceive in the 12 months after surgery.