User login

Predictors may help to spot risk for hydroxychloroquine nonadherence

who are newly prescribed the antimalarial, an administrative claims database study has revealed.

Investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, used prescription refill data to assess nonadherence, hoping to gain greater insight into predictors of nonadherence to HCQ than past studies of nonadherence to the drug, which have been limited by their small and cross-sectional nature and the fact that they often relied on self-reported measures of adherence that were unable to capture the dynamic nature of adherence behavior over time.

In the current study, Candace H. Feldman, MD, ScD, and her coinvestigators used Medicaid data from 28 U.S. states to identify 10,406 adult HCQ initiators with SLE during 2001-2010. Patients included in the study were required to have more than 365 days of continuous follow-up documented.

The researchers described four distinctive monthly patterns of behavior during the first year of use, in which they defined nonadherence as less than 80% of days covered per month by a HCQ prescription. Group 1 comprised 36% who were “persistent nonadherers” who had very few HCQ refills after the initial dispensing.

Almost half of the cohort (47%) formed two dynamic patterns of partial adherence (groups 2 and 3). The trajectories for these groups were similar until month 5, when they diverged: group 3 improved slightly and then reached a plateau, whereas group 2 became nearly completely nonadherent for the remainder of follow-up. At this 5-month point of divergence, belonging to group 2 was more likely among patients with younger age and antidepressant use. Also, patients in group 3 had more hospitalizations beginning at 4 months and longer hospitalizations at 5 months.

For these two “undecided” groups, 5 months may be a “critical juncture” for physicians to intervene, the authors said.

“Five months might also be the point at which patients feel that they have adequately trialed the medication, and if there is no symptomatic improvement, they discontinue. With the growing body of literature suggesting long-term preventive effects from HCQ, increased provider and patient education at this juncture may be beneficial,” they wrote.

Group 4 had persistent adherence and constituted 17% of the cohort, although this group also experienced a decline in adherence at 9 months.

The mean age of group 4 was about 40 years, which was significantly older than 37 years in groups 1-3. Blacks comprised the highest percentage of patients in groups 1-3 (43%-45%), whereas whites at 40% were the highest proportion in group 4. Individuals in group 4 also had slightly higher average income than did group 1 (mean $46,000 vs. $44,000). The index for SLE risk adjustment was highest for group 4 patients (1.3 vs. 0.9-1.1 for other groups), indicating they may have had more SLE-related comorbidities. Group 4 patients also had a greater average number of medications dispensed and a higher mean daily prednisone-equivalent dose.

Patients aged 18-50 or with black race or Hispanic ethnicity were significantly more likely to be in one of the nonadherent trajectory groups (1, 2, and 3), whereas Asians were less likely to be in group 1 than in group 4, compared with whites.

Diabetes made patients more likely to belong to group 1 than group 4, whereas each unit increase in the SLE risk-adjustment index increased the odds of belonging to group 1 vs. 4. Antidepressant use was associated with greater likelihood of belong to groups 1 or 2 vs. group 4.

Addressing potentially modifiable factors such as ensuring sustained access to health care, particularly for patients with severe disease, might go some way to improving adherence, suggested the researchers, who also noted that increased counseling and support at the time of the first HCQ prescription and throughout the first year of use are also needed in order to “promote more sustained patterns of adherence for all patients.”

The study was funded by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Investigator Award and individual grant awards from the National Institutes of Health. No relevant financial disclosures were declared by the authors.

SOURCE: Feldman C et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.002

who are newly prescribed the antimalarial, an administrative claims database study has revealed.

Investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, used prescription refill data to assess nonadherence, hoping to gain greater insight into predictors of nonadherence to HCQ than past studies of nonadherence to the drug, which have been limited by their small and cross-sectional nature and the fact that they often relied on self-reported measures of adherence that were unable to capture the dynamic nature of adherence behavior over time.

In the current study, Candace H. Feldman, MD, ScD, and her coinvestigators used Medicaid data from 28 U.S. states to identify 10,406 adult HCQ initiators with SLE during 2001-2010. Patients included in the study were required to have more than 365 days of continuous follow-up documented.

The researchers described four distinctive monthly patterns of behavior during the first year of use, in which they defined nonadherence as less than 80% of days covered per month by a HCQ prescription. Group 1 comprised 36% who were “persistent nonadherers” who had very few HCQ refills after the initial dispensing.

Almost half of the cohort (47%) formed two dynamic patterns of partial adherence (groups 2 and 3). The trajectories for these groups were similar until month 5, when they diverged: group 3 improved slightly and then reached a plateau, whereas group 2 became nearly completely nonadherent for the remainder of follow-up. At this 5-month point of divergence, belonging to group 2 was more likely among patients with younger age and antidepressant use. Also, patients in group 3 had more hospitalizations beginning at 4 months and longer hospitalizations at 5 months.

For these two “undecided” groups, 5 months may be a “critical juncture” for physicians to intervene, the authors said.

“Five months might also be the point at which patients feel that they have adequately trialed the medication, and if there is no symptomatic improvement, they discontinue. With the growing body of literature suggesting long-term preventive effects from HCQ, increased provider and patient education at this juncture may be beneficial,” they wrote.

Group 4 had persistent adherence and constituted 17% of the cohort, although this group also experienced a decline in adherence at 9 months.

The mean age of group 4 was about 40 years, which was significantly older than 37 years in groups 1-3. Blacks comprised the highest percentage of patients in groups 1-3 (43%-45%), whereas whites at 40% were the highest proportion in group 4. Individuals in group 4 also had slightly higher average income than did group 1 (mean $46,000 vs. $44,000). The index for SLE risk adjustment was highest for group 4 patients (1.3 vs. 0.9-1.1 for other groups), indicating they may have had more SLE-related comorbidities. Group 4 patients also had a greater average number of medications dispensed and a higher mean daily prednisone-equivalent dose.

Patients aged 18-50 or with black race or Hispanic ethnicity were significantly more likely to be in one of the nonadherent trajectory groups (1, 2, and 3), whereas Asians were less likely to be in group 1 than in group 4, compared with whites.

Diabetes made patients more likely to belong to group 1 than group 4, whereas each unit increase in the SLE risk-adjustment index increased the odds of belonging to group 1 vs. 4. Antidepressant use was associated with greater likelihood of belong to groups 1 or 2 vs. group 4.

Addressing potentially modifiable factors such as ensuring sustained access to health care, particularly for patients with severe disease, might go some way to improving adherence, suggested the researchers, who also noted that increased counseling and support at the time of the first HCQ prescription and throughout the first year of use are also needed in order to “promote more sustained patterns of adherence for all patients.”

The study was funded by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Investigator Award and individual grant awards from the National Institutes of Health. No relevant financial disclosures were declared by the authors.

SOURCE: Feldman C et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.002

who are newly prescribed the antimalarial, an administrative claims database study has revealed.

Investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, used prescription refill data to assess nonadherence, hoping to gain greater insight into predictors of nonadherence to HCQ than past studies of nonadherence to the drug, which have been limited by their small and cross-sectional nature and the fact that they often relied on self-reported measures of adherence that were unable to capture the dynamic nature of adherence behavior over time.

In the current study, Candace H. Feldman, MD, ScD, and her coinvestigators used Medicaid data from 28 U.S. states to identify 10,406 adult HCQ initiators with SLE during 2001-2010. Patients included in the study were required to have more than 365 days of continuous follow-up documented.

The researchers described four distinctive monthly patterns of behavior during the first year of use, in which they defined nonadherence as less than 80% of days covered per month by a HCQ prescription. Group 1 comprised 36% who were “persistent nonadherers” who had very few HCQ refills after the initial dispensing.

Almost half of the cohort (47%) formed two dynamic patterns of partial adherence (groups 2 and 3). The trajectories for these groups were similar until month 5, when they diverged: group 3 improved slightly and then reached a plateau, whereas group 2 became nearly completely nonadherent for the remainder of follow-up. At this 5-month point of divergence, belonging to group 2 was more likely among patients with younger age and antidepressant use. Also, patients in group 3 had more hospitalizations beginning at 4 months and longer hospitalizations at 5 months.

For these two “undecided” groups, 5 months may be a “critical juncture” for physicians to intervene, the authors said.

“Five months might also be the point at which patients feel that they have adequately trialed the medication, and if there is no symptomatic improvement, they discontinue. With the growing body of literature suggesting long-term preventive effects from HCQ, increased provider and patient education at this juncture may be beneficial,” they wrote.

Group 4 had persistent adherence and constituted 17% of the cohort, although this group also experienced a decline in adherence at 9 months.

The mean age of group 4 was about 40 years, which was significantly older than 37 years in groups 1-3. Blacks comprised the highest percentage of patients in groups 1-3 (43%-45%), whereas whites at 40% were the highest proportion in group 4. Individuals in group 4 also had slightly higher average income than did group 1 (mean $46,000 vs. $44,000). The index for SLE risk adjustment was highest for group 4 patients (1.3 vs. 0.9-1.1 for other groups), indicating they may have had more SLE-related comorbidities. Group 4 patients also had a greater average number of medications dispensed and a higher mean daily prednisone-equivalent dose.

Patients aged 18-50 or with black race or Hispanic ethnicity were significantly more likely to be in one of the nonadherent trajectory groups (1, 2, and 3), whereas Asians were less likely to be in group 1 than in group 4, compared with whites.

Diabetes made patients more likely to belong to group 1 than group 4, whereas each unit increase in the SLE risk-adjustment index increased the odds of belonging to group 1 vs. 4. Antidepressant use was associated with greater likelihood of belong to groups 1 or 2 vs. group 4.

Addressing potentially modifiable factors such as ensuring sustained access to health care, particularly for patients with severe disease, might go some way to improving adherence, suggested the researchers, who also noted that increased counseling and support at the time of the first HCQ prescription and throughout the first year of use are also needed in order to “promote more sustained patterns of adherence for all patients.”

The study was funded by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Investigator Award and individual grant awards from the National Institutes of Health. No relevant financial disclosures were declared by the authors.

SOURCE: Feldman C et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.002

FROM SEMINARS IN ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Key clinical point: Five months after the first HCQ prescription might be a critical time point to review and educate patients on the importance of continuing treatment, particularly for patients who are “partial” adherers.

Major finding: Almost half of the cohort (47%) formed two dynamic patterns of partial adherence.

Data source: A longitudinal study of 10,406 Medicaid beneficiaries with SLE who were prescribed hydroxychloroquine for the first time.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Investigator Award and individual grant awards from the National Institutes of Health. No relevant financial disclosures were declared by the authors.

Source: Feldman C et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.002

Pulmonary Mucormycosis in a Patient With Uncontrolled Diabetes

Mucorales fungi are ubiquitous organisms commonly inhabiting soil and can cause opportunistic infections. The majority of infections are caused by 3 genera: Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor.1 Infection occurs by inhalation or by direct contact with damaged skin. Mucorales infections can have cutaneous, rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system manifestations. Pulmonary mucormycosis is often rapidly progressive with angioinvasion and fulminant necrosis causing acute dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. More indolent pulmonary Mucorales infections can mimic a pulmonary mass with occasional cavitation found on imaging studies similar to other fungal infections (eg, Aspergillus).2 Risk factors include severe uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM), recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), immunosuppression due to congenital or acquired causes, hematologic malignancies, and chronic renal failure.3 The authors present a case of a patient with recurrent DKA and pulmonary mucormycosis.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old male with DM and a more than 30-pack-year smoking history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and chest pain ongoing for about 1 week. The patient had a history of frequent admissions with DKA and medication nonadherence.

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable. His vital signs were: temperature 97.4° F, heart rate 89 bpm, respirations 24 breathes per minute, blood pressure 146/86 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 94% on ambient air. The patient appeared ill but the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 24,400 with neutrophilic predominance, blood glucose 658 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 2.16 mL/min/1.73 m2, sodium level 124 mEq/L, bicarbonate 6 mEq/L, anion gap 27 mEq/L, 6.8 pH, partial pressure of CO2 11 mm Hg, and lactic acid 2.3 mmol/L.

The patient admitted for DKA management and placed on an insulin drip. Although he did not have a fever or cough productive of sputum or hemoptysis, there was concern that pneumonia might have precipitated DKA. A chest X-ray revealed a patchy, right suprahilar opacity (Figure 1).

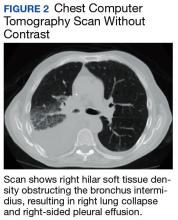

The patient was placed on vancomycin 1,000 mg every 12 hours and cefepime 2,000 mg every 12 hours for possible hospital-acquired pneumonia because of his history of recent DKA hospitalization. Once the patient’s anion gap was closed and metabolic acidosis was resolved, the insulin drip was discontinued, and the patient was transferred to the general medical ward for further management. There, he continued to report having chest pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast of the chest (contrast was held due to recent acute kidney injury) revealed right hilar soft tissue density obstructing the bronchus intermidius, which had resulted in a right-lung collapse and right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 2). The left lung was clear, and there was no evidence of nodularity.

Given the patient’s extensive smoking history, the initial concern was for pulmonary malignancy. The decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy. Endobronchial brushings and biopsies of R11, 7, right bronchus intermedius, and right upper lobe were obtained. Gross inspection of the airway revealed markedly abnormal-appearing mucosa involving the take off to the right upper lobe and the entire bronchus intermedius with friable, cobblestoned, and edematous mucosa. Biopsies and immunostaining for occult carcinoma markers, including CD-56, TTF-1, Synaptophysin A, chromogranin, AE1/AE3, and CK-5/6, were negative for malignancy. Final microbiologic analysis was positive for Mucor. There was no evidence of bacterial or mycobacterial growth.

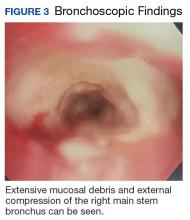

Due to continued suspicion for malignancy and lack of histologic yield, the patient underwent a repeat endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy. On this occasion, gross inspection revealed significant mucosal necrosis and extensive, extrinsic bronchial compression starting from the right bronchial division and notable throughout the right middle and lower lobes (Figure 3).

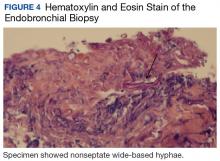

Bronchial washings revealed necrotic material with rare fungal hyphae present. Biopsies yielded necrotic material or lung tissue containing nonseptate hyphae with rare, right-angle branching consistent with Mucor (Figures 4 and 5). Malignancy was not present in the specimens obtained.

Based on the bronchoscopy results, thoracic surgery and infectious disease specialists were consulted. Surgical intervention was not recommended because of concerns for potential postoperative complications. The infectious disease specialists recommended initiation of liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg/d. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed parietal lobe enhancement with restricted diffusion most consistent with prior infarct. Paranasal sinus disease also was demonstrated. The latter findings prompted further evaluation. The patient underwent right and left endoscopic resection of concha bullosa as well as left maxillary endoscopic antrostomy. Gross examination showed thick mucosa in left concha bullosa, polypoid changes anterior to bulla ethmoidalis, and clear left maxillary sinus. The procedure had to be aborted when the patient experienced cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation; he was successfully resuscitated.

Samples from the contents of right and left sinuses as well as left concha bullosa were submitted to pathology, showing benign respiratory mucosa with chronic inflammation and foci of bone without fungal elements. There was no other evidence of disseminated mucormycosis. The patient had a prolonged hospital course complicated by progressive hypoxemia, acute kidney injury, and toxic metabolic encephalopathy. Three months after his original diagnosis, he sustained another cardiac arrest in the hospital. Shortly after achieving return of spontaneous circulation and initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation, the family elected to withdraw care. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

This article describes a case of subacute pulmonary mucormycosis in a patient with recurrent DKA. Although patients with poorly controlled DM commonly present with the rhinocerebral form of mucormycosis, pulmonary involvement with a subacute course has been described. Determining the final diagnosis for the current patient was challenging due to the subtlety of his respiratory symptoms and the inconsistent initial findings on chest radiography. A pulmonary disease was finally suspected when a mass was found on the CT scan. However, the middle mediastinal mass was more suspicious for malignancy, particularly given the patient’s smoking history and persistent hyponatremia. In fact, the lack of any neoplastic findings on the initial endobronchial biopsy prompted the health care team to pursue a second biopsy that was consistent with mucormycosis.

This case demonstrates the challenges of prompt diagnosis and treatment of this potentially fatal infection. Furthermore, the extent of the disease at diagnosis precluded this patient from having a surgical intervention, which has been associated with better outcomes than those of medical management alone. Finally, it remains unknown whether the patient had an underlying malignancy, which could have increased the likelihood of pulmonary mucormycosis; the biopsy yield may have been confounded by repeated sampling of necrotic material caused by mucormycosis. Further investigation of any potential pulmonary neoplasm was limited by the patient’s clinical condition and the poor prognosis due to the extent of infection.

Mucorales is an order of fungi comprised of 6 main families that have potential to cause a variety of infections. The genera Mucor, Rhizopus, and Rhizomucor cause the majority of infections.1 Mucormycosis (infection with Mucorales) is generally a rare fungal infection with an incidence of about 500 cases per year in the U.S. However, the incidence is increasing with an aging population, higher prevalence of DM and chronic kidney disease, and a growing population of immunocompromised patients due to advances in cancer therapy and transplantation. Risk factors for pulmonary mucormycosis include conditions associated with congenital and acquired immunodeficiency: hematologic malignancies, uncontrolled DM, solid tumors, and organ transplantation.2

Presentation

Notably, there seems to be an association between specific organ system involvement and predisposing conditions. Pulmonary mucormycosis occurs much less frequently than does the rhinocerebral form in patients with DKA but occurs more commonly in patients with neutropenia that is due to chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for the treatment of hematologic malignancies.2

The mechanisms for preferential site infection are not well understood with current knowledge of mucormycosis pathogenesis. Current research demonstrates monocytes and neutrophils may play a vital role in the body’s defense against Mucor by both phagocytosis and oxidative damage. Chemotaxis and oxidative cell lysis seem to be compromised in states of hyperglycemia and acidosis. Iron metabolism repeatedly has been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Specifically, patients receiving deferoxamine seem to have a predisposition to Mucorales infections, presumably due to the increased iron supply to the fungus.4 Notably, systemic acidosis also facilitates higher concentrations of available serum iron.

One of the main characteristics of mucormycosis is its ability to aggressively invade blood vessels, causing thrombosis and necrosis and subsequently disseminate hematogenously or through the lymphatic system. This property, at least in large part, depends on endothelial cell damage following phagocytosis of fungus by these cells.

Of note, some of the azole class of drugs (eg, voriconazole), which may be used for antifungal prophylaxis in patients with hematologic malignancies accompanied by neutropenia, have been implicated in predisposition to mucormycosis.2 It also is commonly seen in patients undergoing HSCT. Patients with DM and DKA also can present with pulmonary mucormycosis but generally have a more indolent course unless they develop pulmonary hemorrhage.3 Infection usually occurs by inhalation.

Patients may report dyspnea, cough, and chest pain, which is sometimes accompanied by a fever. Presentation is generally indistinguishable from other causes of pneumonia, and the routinely obtained sputum cultures are usually not diagnostically significant.

Radiographic findings are variable and may include pulmonary nodules, consolidations, masses, and cavitary lesions.1 Due to tissue invasion, a CT scan of the chest might demonstrate a mass crossing mediastinal tissue planes. Definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy with a demonstration of characteristic broad-based nonseptate hyphae with tissue invasion as well as a positive culture (Figures 4 and 5).5 Due to nonspecific symptoms as well as laboratory and imaging findings, a biopsy and, therefore, definitive diagnosis are often delayed. However, postponing medical and surgical therapy for mucormycosis has been associated with worse outcomes.6 With the absence of easily available serologic tests and unspecific symptoms in early disease, many mucormycosis cases are diagnosed postmortem.

Treatments

Recently described therapy advancements have indicated improved outcomes.7 Nevertheless, prognosis remains universally poor with 65% to 70% mortality for patients with cases of isolated pulmonary mucormycosis.8 Many of these patients succumb to sepsis, respiratory failure, and hemoptysis. Patients with pulmonary mucormycosis usually die of dissemination rather than of the sequelae of the pulmonary disease. In fact, pulmonary infection seems to have the highest incidence of dissemination in patients with neutropenia. Surgical therapy seems to have more favorable outcomes than treatment with antifungals alone, especially when considering infection primarily affecting 1 lung.8

Amphotericin B remains the first-line agent for treatment of pulmonary mucormycosis. Retrospective studies show that this agent remains one of the few with activity against Mucor with reported successful outcomes. Specifically, the liposomal formulation seems to have greater efficacy.9 Strong prospective data are lacking. An increasing body of evidence supports a potential benefit from adding echinocandins.10 Although these agents have minimal activity against mucormycosis in vitro, adjunctive therapy to amphotericin resulted in better survival. Alternative regimens include the combination of amphotericin with posaconazole or itraconazole. Both these agents seem to have in vitro activity against mucormycosis pathogens, although poor absorption of these agents puts the potential benefit of such combinations in question.

In patients unable to tolerate polyenes due to adverse effects (AEs), the use of posaconazole as monotherapy has been reported with positive results. One retrospective study reported treatment success in up to 60% and stable disease in 21% of patients at 12 weeks. This study included 24 out of 36 patients with pulmonary mucormycosis.11 Significantly fewer AEs and oral administration makes posaconazole an attractive alternative treatment for mucormycosis and needs further prospective evaluation.

Novel therapies have been attempted, though without success thus far. One randomized clinical trial conducted on patients with mucormycosis attempted to determine whether capitalizing on iron metabolism by Mucor by providing adjunctive deferasirox, an iron chelator, would lead to an initial improvement in mortality. However, outcomes did not improve and resulted in higher mortality rates at 90 days in the intervention group.12

Reversal of underlying conditions remains the cornerstone of successful therapy. If possible, it is important to cease immunosuppression by avoiding corticosteroids, correcting acidosis and hyperglycemia, and discontinuing aluminum and iron chelators.13 This approach becomes problematic in patients with DM with poor glucose control due to nonadherence or lack of resources and in situations where the underlying condition is difficult to treat or the treatment puts patients at risk for mucormycosis (eg, malignancies). Surgery in addition to antifungal therapy should be pursued wherever possible for definitive therapy.

1. Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(2):236-301.

2. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Pulmonary fungal infections. Respirology. 2012;17(6):913-926.

3. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(3):556-569.

4. Prokopowicz GP, Bradley SF, Kauffman CA. Indolent zygomycosis associated with deferoxamine chelation therapy. Mycoses. 1994;37(11-12):427-431.

5. Hamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. Pulmonary mucormycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32(6):693-702.

6. Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):503-509.

7. Parfrey NA. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis. A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986;65(2):113-1

8. Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP, Hegde SS, Tedder SD, Lowe JE. Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(4):1044-1050.

9.

10. Reed C, Bryant R, Ibrahim AS, et al. Combination polyene-caspofungin treatment of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(3):364-371.

11. van Burik JA, Hare RS, Solomon HF, Corrado ML, Kontoyiannis DP. Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):e61-e65.

12. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS, Chin-Hong PV, et al. The Deferasirox-AmBisome Therapy for Mucormycosis (DEFEAT Mucor) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(3):715-722.

13. de Locht M, Boelaert JR, Schneider YJ. Iron uptake from ferrioxamine and from ferrirhizoferrin by germinating spores of Rhizopus microsporus. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994; 47(10):1843-1850.

Mucorales fungi are ubiquitous organisms commonly inhabiting soil and can cause opportunistic infections. The majority of infections are caused by 3 genera: Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor.1 Infection occurs by inhalation or by direct contact with damaged skin. Mucorales infections can have cutaneous, rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system manifestations. Pulmonary mucormycosis is often rapidly progressive with angioinvasion and fulminant necrosis causing acute dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. More indolent pulmonary Mucorales infections can mimic a pulmonary mass with occasional cavitation found on imaging studies similar to other fungal infections (eg, Aspergillus).2 Risk factors include severe uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM), recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), immunosuppression due to congenital or acquired causes, hematologic malignancies, and chronic renal failure.3 The authors present a case of a patient with recurrent DKA and pulmonary mucormycosis.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old male with DM and a more than 30-pack-year smoking history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and chest pain ongoing for about 1 week. The patient had a history of frequent admissions with DKA and medication nonadherence.

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable. His vital signs were: temperature 97.4° F, heart rate 89 bpm, respirations 24 breathes per minute, blood pressure 146/86 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 94% on ambient air. The patient appeared ill but the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 24,400 with neutrophilic predominance, blood glucose 658 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 2.16 mL/min/1.73 m2, sodium level 124 mEq/L, bicarbonate 6 mEq/L, anion gap 27 mEq/L, 6.8 pH, partial pressure of CO2 11 mm Hg, and lactic acid 2.3 mmol/L.

The patient admitted for DKA management and placed on an insulin drip. Although he did not have a fever or cough productive of sputum or hemoptysis, there was concern that pneumonia might have precipitated DKA. A chest X-ray revealed a patchy, right suprahilar opacity (Figure 1).

The patient was placed on vancomycin 1,000 mg every 12 hours and cefepime 2,000 mg every 12 hours for possible hospital-acquired pneumonia because of his history of recent DKA hospitalization. Once the patient’s anion gap was closed and metabolic acidosis was resolved, the insulin drip was discontinued, and the patient was transferred to the general medical ward for further management. There, he continued to report having chest pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast of the chest (contrast was held due to recent acute kidney injury) revealed right hilar soft tissue density obstructing the bronchus intermidius, which had resulted in a right-lung collapse and right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 2). The left lung was clear, and there was no evidence of nodularity.

Given the patient’s extensive smoking history, the initial concern was for pulmonary malignancy. The decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy. Endobronchial brushings and biopsies of R11, 7, right bronchus intermedius, and right upper lobe were obtained. Gross inspection of the airway revealed markedly abnormal-appearing mucosa involving the take off to the right upper lobe and the entire bronchus intermedius with friable, cobblestoned, and edematous mucosa. Biopsies and immunostaining for occult carcinoma markers, including CD-56, TTF-1, Synaptophysin A, chromogranin, AE1/AE3, and CK-5/6, were negative for malignancy. Final microbiologic analysis was positive for Mucor. There was no evidence of bacterial or mycobacterial growth.

Due to continued suspicion for malignancy and lack of histologic yield, the patient underwent a repeat endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy. On this occasion, gross inspection revealed significant mucosal necrosis and extensive, extrinsic bronchial compression starting from the right bronchial division and notable throughout the right middle and lower lobes (Figure 3).

Bronchial washings revealed necrotic material with rare fungal hyphae present. Biopsies yielded necrotic material or lung tissue containing nonseptate hyphae with rare, right-angle branching consistent with Mucor (Figures 4 and 5). Malignancy was not present in the specimens obtained.

Based on the bronchoscopy results, thoracic surgery and infectious disease specialists were consulted. Surgical intervention was not recommended because of concerns for potential postoperative complications. The infectious disease specialists recommended initiation of liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg/d. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed parietal lobe enhancement with restricted diffusion most consistent with prior infarct. Paranasal sinus disease also was demonstrated. The latter findings prompted further evaluation. The patient underwent right and left endoscopic resection of concha bullosa as well as left maxillary endoscopic antrostomy. Gross examination showed thick mucosa in left concha bullosa, polypoid changes anterior to bulla ethmoidalis, and clear left maxillary sinus. The procedure had to be aborted when the patient experienced cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation; he was successfully resuscitated.

Samples from the contents of right and left sinuses as well as left concha bullosa were submitted to pathology, showing benign respiratory mucosa with chronic inflammation and foci of bone without fungal elements. There was no other evidence of disseminated mucormycosis. The patient had a prolonged hospital course complicated by progressive hypoxemia, acute kidney injury, and toxic metabolic encephalopathy. Three months after his original diagnosis, he sustained another cardiac arrest in the hospital. Shortly after achieving return of spontaneous circulation and initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation, the family elected to withdraw care. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

This article describes a case of subacute pulmonary mucormycosis in a patient with recurrent DKA. Although patients with poorly controlled DM commonly present with the rhinocerebral form of mucormycosis, pulmonary involvement with a subacute course has been described. Determining the final diagnosis for the current patient was challenging due to the subtlety of his respiratory symptoms and the inconsistent initial findings on chest radiography. A pulmonary disease was finally suspected when a mass was found on the CT scan. However, the middle mediastinal mass was more suspicious for malignancy, particularly given the patient’s smoking history and persistent hyponatremia. In fact, the lack of any neoplastic findings on the initial endobronchial biopsy prompted the health care team to pursue a second biopsy that was consistent with mucormycosis.

This case demonstrates the challenges of prompt diagnosis and treatment of this potentially fatal infection. Furthermore, the extent of the disease at diagnosis precluded this patient from having a surgical intervention, which has been associated with better outcomes than those of medical management alone. Finally, it remains unknown whether the patient had an underlying malignancy, which could have increased the likelihood of pulmonary mucormycosis; the biopsy yield may have been confounded by repeated sampling of necrotic material caused by mucormycosis. Further investigation of any potential pulmonary neoplasm was limited by the patient’s clinical condition and the poor prognosis due to the extent of infection.

Mucorales is an order of fungi comprised of 6 main families that have potential to cause a variety of infections. The genera Mucor, Rhizopus, and Rhizomucor cause the majority of infections.1 Mucormycosis (infection with Mucorales) is generally a rare fungal infection with an incidence of about 500 cases per year in the U.S. However, the incidence is increasing with an aging population, higher prevalence of DM and chronic kidney disease, and a growing population of immunocompromised patients due to advances in cancer therapy and transplantation. Risk factors for pulmonary mucormycosis include conditions associated with congenital and acquired immunodeficiency: hematologic malignancies, uncontrolled DM, solid tumors, and organ transplantation.2

Presentation

Notably, there seems to be an association between specific organ system involvement and predisposing conditions. Pulmonary mucormycosis occurs much less frequently than does the rhinocerebral form in patients with DKA but occurs more commonly in patients with neutropenia that is due to chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for the treatment of hematologic malignancies.2

The mechanisms for preferential site infection are not well understood with current knowledge of mucormycosis pathogenesis. Current research demonstrates monocytes and neutrophils may play a vital role in the body’s defense against Mucor by both phagocytosis and oxidative damage. Chemotaxis and oxidative cell lysis seem to be compromised in states of hyperglycemia and acidosis. Iron metabolism repeatedly has been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Specifically, patients receiving deferoxamine seem to have a predisposition to Mucorales infections, presumably due to the increased iron supply to the fungus.4 Notably, systemic acidosis also facilitates higher concentrations of available serum iron.

One of the main characteristics of mucormycosis is its ability to aggressively invade blood vessels, causing thrombosis and necrosis and subsequently disseminate hematogenously or through the lymphatic system. This property, at least in large part, depends on endothelial cell damage following phagocytosis of fungus by these cells.

Of note, some of the azole class of drugs (eg, voriconazole), which may be used for antifungal prophylaxis in patients with hematologic malignancies accompanied by neutropenia, have been implicated in predisposition to mucormycosis.2 It also is commonly seen in patients undergoing HSCT. Patients with DM and DKA also can present with pulmonary mucormycosis but generally have a more indolent course unless they develop pulmonary hemorrhage.3 Infection usually occurs by inhalation.

Patients may report dyspnea, cough, and chest pain, which is sometimes accompanied by a fever. Presentation is generally indistinguishable from other causes of pneumonia, and the routinely obtained sputum cultures are usually not diagnostically significant.

Radiographic findings are variable and may include pulmonary nodules, consolidations, masses, and cavitary lesions.1 Due to tissue invasion, a CT scan of the chest might demonstrate a mass crossing mediastinal tissue planes. Definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy with a demonstration of characteristic broad-based nonseptate hyphae with tissue invasion as well as a positive culture (Figures 4 and 5).5 Due to nonspecific symptoms as well as laboratory and imaging findings, a biopsy and, therefore, definitive diagnosis are often delayed. However, postponing medical and surgical therapy for mucormycosis has been associated with worse outcomes.6 With the absence of easily available serologic tests and unspecific symptoms in early disease, many mucormycosis cases are diagnosed postmortem.

Treatments

Recently described therapy advancements have indicated improved outcomes.7 Nevertheless, prognosis remains universally poor with 65% to 70% mortality for patients with cases of isolated pulmonary mucormycosis.8 Many of these patients succumb to sepsis, respiratory failure, and hemoptysis. Patients with pulmonary mucormycosis usually die of dissemination rather than of the sequelae of the pulmonary disease. In fact, pulmonary infection seems to have the highest incidence of dissemination in patients with neutropenia. Surgical therapy seems to have more favorable outcomes than treatment with antifungals alone, especially when considering infection primarily affecting 1 lung.8

Amphotericin B remains the first-line agent for treatment of pulmonary mucormycosis. Retrospective studies show that this agent remains one of the few with activity against Mucor with reported successful outcomes. Specifically, the liposomal formulation seems to have greater efficacy.9 Strong prospective data are lacking. An increasing body of evidence supports a potential benefit from adding echinocandins.10 Although these agents have minimal activity against mucormycosis in vitro, adjunctive therapy to amphotericin resulted in better survival. Alternative regimens include the combination of amphotericin with posaconazole or itraconazole. Both these agents seem to have in vitro activity against mucormycosis pathogens, although poor absorption of these agents puts the potential benefit of such combinations in question.

In patients unable to tolerate polyenes due to adverse effects (AEs), the use of posaconazole as monotherapy has been reported with positive results. One retrospective study reported treatment success in up to 60% and stable disease in 21% of patients at 12 weeks. This study included 24 out of 36 patients with pulmonary mucormycosis.11 Significantly fewer AEs and oral administration makes posaconazole an attractive alternative treatment for mucormycosis and needs further prospective evaluation.

Novel therapies have been attempted, though without success thus far. One randomized clinical trial conducted on patients with mucormycosis attempted to determine whether capitalizing on iron metabolism by Mucor by providing adjunctive deferasirox, an iron chelator, would lead to an initial improvement in mortality. However, outcomes did not improve and resulted in higher mortality rates at 90 days in the intervention group.12

Reversal of underlying conditions remains the cornerstone of successful therapy. If possible, it is important to cease immunosuppression by avoiding corticosteroids, correcting acidosis and hyperglycemia, and discontinuing aluminum and iron chelators.13 This approach becomes problematic in patients with DM with poor glucose control due to nonadherence or lack of resources and in situations where the underlying condition is difficult to treat or the treatment puts patients at risk for mucormycosis (eg, malignancies). Surgery in addition to antifungal therapy should be pursued wherever possible for definitive therapy.

Mucorales fungi are ubiquitous organisms commonly inhabiting soil and can cause opportunistic infections. The majority of infections are caused by 3 genera: Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor.1 Infection occurs by inhalation or by direct contact with damaged skin. Mucorales infections can have cutaneous, rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system manifestations. Pulmonary mucormycosis is often rapidly progressive with angioinvasion and fulminant necrosis causing acute dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. More indolent pulmonary Mucorales infections can mimic a pulmonary mass with occasional cavitation found on imaging studies similar to other fungal infections (eg, Aspergillus).2 Risk factors include severe uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (DM), recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), immunosuppression due to congenital or acquired causes, hematologic malignancies, and chronic renal failure.3 The authors present a case of a patient with recurrent DKA and pulmonary mucormycosis.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old male with DM and a more than 30-pack-year smoking history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and chest pain ongoing for about 1 week. The patient had a history of frequent admissions with DKA and medication nonadherence.

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable. His vital signs were: temperature 97.4° F, heart rate 89 bpm, respirations 24 breathes per minute, blood pressure 146/86 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 94% on ambient air. The patient appeared ill but the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 24,400 with neutrophilic predominance, blood glucose 658 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 2.16 mL/min/1.73 m2, sodium level 124 mEq/L, bicarbonate 6 mEq/L, anion gap 27 mEq/L, 6.8 pH, partial pressure of CO2 11 mm Hg, and lactic acid 2.3 mmol/L.

The patient admitted for DKA management and placed on an insulin drip. Although he did not have a fever or cough productive of sputum or hemoptysis, there was concern that pneumonia might have precipitated DKA. A chest X-ray revealed a patchy, right suprahilar opacity (Figure 1).

The patient was placed on vancomycin 1,000 mg every 12 hours and cefepime 2,000 mg every 12 hours for possible hospital-acquired pneumonia because of his history of recent DKA hospitalization. Once the patient’s anion gap was closed and metabolic acidosis was resolved, the insulin drip was discontinued, and the patient was transferred to the general medical ward for further management. There, he continued to report having chest pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast of the chest (contrast was held due to recent acute kidney injury) revealed right hilar soft tissue density obstructing the bronchus intermidius, which had resulted in a right-lung collapse and right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 2). The left lung was clear, and there was no evidence of nodularity.

Given the patient’s extensive smoking history, the initial concern was for pulmonary malignancy. The decision was made to proceed with bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy. Endobronchial brushings and biopsies of R11, 7, right bronchus intermedius, and right upper lobe were obtained. Gross inspection of the airway revealed markedly abnormal-appearing mucosa involving the take off to the right upper lobe and the entire bronchus intermedius with friable, cobblestoned, and edematous mucosa. Biopsies and immunostaining for occult carcinoma markers, including CD-56, TTF-1, Synaptophysin A, chromogranin, AE1/AE3, and CK-5/6, were negative for malignancy. Final microbiologic analysis was positive for Mucor. There was no evidence of bacterial or mycobacterial growth.

Due to continued suspicion for malignancy and lack of histologic yield, the patient underwent a repeat endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy. On this occasion, gross inspection revealed significant mucosal necrosis and extensive, extrinsic bronchial compression starting from the right bronchial division and notable throughout the right middle and lower lobes (Figure 3).

Bronchial washings revealed necrotic material with rare fungal hyphae present. Biopsies yielded necrotic material or lung tissue containing nonseptate hyphae with rare, right-angle branching consistent with Mucor (Figures 4 and 5). Malignancy was not present in the specimens obtained.

Based on the bronchoscopy results, thoracic surgery and infectious disease specialists were consulted. Surgical intervention was not recommended because of concerns for potential postoperative complications. The infectious disease specialists recommended initiation of liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg/d. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed parietal lobe enhancement with restricted diffusion most consistent with prior infarct. Paranasal sinus disease also was demonstrated. The latter findings prompted further evaluation. The patient underwent right and left endoscopic resection of concha bullosa as well as left maxillary endoscopic antrostomy. Gross examination showed thick mucosa in left concha bullosa, polypoid changes anterior to bulla ethmoidalis, and clear left maxillary sinus. The procedure had to be aborted when the patient experienced cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular fibrillation; he was successfully resuscitated.

Samples from the contents of right and left sinuses as well as left concha bullosa were submitted to pathology, showing benign respiratory mucosa with chronic inflammation and foci of bone without fungal elements. There was no other evidence of disseminated mucormycosis. The patient had a prolonged hospital course complicated by progressive hypoxemia, acute kidney injury, and toxic metabolic encephalopathy. Three months after his original diagnosis, he sustained another cardiac arrest in the hospital. Shortly after achieving return of spontaneous circulation and initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation, the family elected to withdraw care. The family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

This article describes a case of subacute pulmonary mucormycosis in a patient with recurrent DKA. Although patients with poorly controlled DM commonly present with the rhinocerebral form of mucormycosis, pulmonary involvement with a subacute course has been described. Determining the final diagnosis for the current patient was challenging due to the subtlety of his respiratory symptoms and the inconsistent initial findings on chest radiography. A pulmonary disease was finally suspected when a mass was found on the CT scan. However, the middle mediastinal mass was more suspicious for malignancy, particularly given the patient’s smoking history and persistent hyponatremia. In fact, the lack of any neoplastic findings on the initial endobronchial biopsy prompted the health care team to pursue a second biopsy that was consistent with mucormycosis.

This case demonstrates the challenges of prompt diagnosis and treatment of this potentially fatal infection. Furthermore, the extent of the disease at diagnosis precluded this patient from having a surgical intervention, which has been associated with better outcomes than those of medical management alone. Finally, it remains unknown whether the patient had an underlying malignancy, which could have increased the likelihood of pulmonary mucormycosis; the biopsy yield may have been confounded by repeated sampling of necrotic material caused by mucormycosis. Further investigation of any potential pulmonary neoplasm was limited by the patient’s clinical condition and the poor prognosis due to the extent of infection.

Mucorales is an order of fungi comprised of 6 main families that have potential to cause a variety of infections. The genera Mucor, Rhizopus, and Rhizomucor cause the majority of infections.1 Mucormycosis (infection with Mucorales) is generally a rare fungal infection with an incidence of about 500 cases per year in the U.S. However, the incidence is increasing with an aging population, higher prevalence of DM and chronic kidney disease, and a growing population of immunocompromised patients due to advances in cancer therapy and transplantation. Risk factors for pulmonary mucormycosis include conditions associated with congenital and acquired immunodeficiency: hematologic malignancies, uncontrolled DM, solid tumors, and organ transplantation.2

Presentation

Notably, there seems to be an association between specific organ system involvement and predisposing conditions. Pulmonary mucormycosis occurs much less frequently than does the rhinocerebral form in patients with DKA but occurs more commonly in patients with neutropenia that is due to chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for the treatment of hematologic malignancies.2

The mechanisms for preferential site infection are not well understood with current knowledge of mucormycosis pathogenesis. Current research demonstrates monocytes and neutrophils may play a vital role in the body’s defense against Mucor by both phagocytosis and oxidative damage. Chemotaxis and oxidative cell lysis seem to be compromised in states of hyperglycemia and acidosis. Iron metabolism repeatedly has been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Specifically, patients receiving deferoxamine seem to have a predisposition to Mucorales infections, presumably due to the increased iron supply to the fungus.4 Notably, systemic acidosis also facilitates higher concentrations of available serum iron.

One of the main characteristics of mucormycosis is its ability to aggressively invade blood vessels, causing thrombosis and necrosis and subsequently disseminate hematogenously or through the lymphatic system. This property, at least in large part, depends on endothelial cell damage following phagocytosis of fungus by these cells.

Of note, some of the azole class of drugs (eg, voriconazole), which may be used for antifungal prophylaxis in patients with hematologic malignancies accompanied by neutropenia, have been implicated in predisposition to mucormycosis.2 It also is commonly seen in patients undergoing HSCT. Patients with DM and DKA also can present with pulmonary mucormycosis but generally have a more indolent course unless they develop pulmonary hemorrhage.3 Infection usually occurs by inhalation.

Patients may report dyspnea, cough, and chest pain, which is sometimes accompanied by a fever. Presentation is generally indistinguishable from other causes of pneumonia, and the routinely obtained sputum cultures are usually not diagnostically significant.

Radiographic findings are variable and may include pulmonary nodules, consolidations, masses, and cavitary lesions.1 Due to tissue invasion, a CT scan of the chest might demonstrate a mass crossing mediastinal tissue planes. Definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy with a demonstration of characteristic broad-based nonseptate hyphae with tissue invasion as well as a positive culture (Figures 4 and 5).5 Due to nonspecific symptoms as well as laboratory and imaging findings, a biopsy and, therefore, definitive diagnosis are often delayed. However, postponing medical and surgical therapy for mucormycosis has been associated with worse outcomes.6 With the absence of easily available serologic tests and unspecific symptoms in early disease, many mucormycosis cases are diagnosed postmortem.

Treatments

Recently described therapy advancements have indicated improved outcomes.7 Nevertheless, prognosis remains universally poor with 65% to 70% mortality for patients with cases of isolated pulmonary mucormycosis.8 Many of these patients succumb to sepsis, respiratory failure, and hemoptysis. Patients with pulmonary mucormycosis usually die of dissemination rather than of the sequelae of the pulmonary disease. In fact, pulmonary infection seems to have the highest incidence of dissemination in patients with neutropenia. Surgical therapy seems to have more favorable outcomes than treatment with antifungals alone, especially when considering infection primarily affecting 1 lung.8

Amphotericin B remains the first-line agent for treatment of pulmonary mucormycosis. Retrospective studies show that this agent remains one of the few with activity against Mucor with reported successful outcomes. Specifically, the liposomal formulation seems to have greater efficacy.9 Strong prospective data are lacking. An increasing body of evidence supports a potential benefit from adding echinocandins.10 Although these agents have minimal activity against mucormycosis in vitro, adjunctive therapy to amphotericin resulted in better survival. Alternative regimens include the combination of amphotericin with posaconazole or itraconazole. Both these agents seem to have in vitro activity against mucormycosis pathogens, although poor absorption of these agents puts the potential benefit of such combinations in question.

In patients unable to tolerate polyenes due to adverse effects (AEs), the use of posaconazole as monotherapy has been reported with positive results. One retrospective study reported treatment success in up to 60% and stable disease in 21% of patients at 12 weeks. This study included 24 out of 36 patients with pulmonary mucormycosis.11 Significantly fewer AEs and oral administration makes posaconazole an attractive alternative treatment for mucormycosis and needs further prospective evaluation.

Novel therapies have been attempted, though without success thus far. One randomized clinical trial conducted on patients with mucormycosis attempted to determine whether capitalizing on iron metabolism by Mucor by providing adjunctive deferasirox, an iron chelator, would lead to an initial improvement in mortality. However, outcomes did not improve and resulted in higher mortality rates at 90 days in the intervention group.12

Reversal of underlying conditions remains the cornerstone of successful therapy. If possible, it is important to cease immunosuppression by avoiding corticosteroids, correcting acidosis and hyperglycemia, and discontinuing aluminum and iron chelators.13 This approach becomes problematic in patients with DM with poor glucose control due to nonadherence or lack of resources and in situations where the underlying condition is difficult to treat or the treatment puts patients at risk for mucormycosis (eg, malignancies). Surgery in addition to antifungal therapy should be pursued wherever possible for definitive therapy.

1. Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(2):236-301.

2. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Pulmonary fungal infections. Respirology. 2012;17(6):913-926.

3. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(3):556-569.

4. Prokopowicz GP, Bradley SF, Kauffman CA. Indolent zygomycosis associated with deferoxamine chelation therapy. Mycoses. 1994;37(11-12):427-431.

5. Hamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. Pulmonary mucormycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32(6):693-702.

6. Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):503-509.

7. Parfrey NA. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis. A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986;65(2):113-1

8. Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP, Hegde SS, Tedder SD, Lowe JE. Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(4):1044-1050.

9.

10. Reed C, Bryant R, Ibrahim AS, et al. Combination polyene-caspofungin treatment of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(3):364-371.

11. van Burik JA, Hare RS, Solomon HF, Corrado ML, Kontoyiannis DP. Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):e61-e65.

12. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS, Chin-Hong PV, et al. The Deferasirox-AmBisome Therapy for Mucormycosis (DEFEAT Mucor) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(3):715-722.

13. de Locht M, Boelaert JR, Schneider YJ. Iron uptake from ferrioxamine and from ferrirhizoferrin by germinating spores of Rhizopus microsporus. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994; 47(10):1843-1850.

1. Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(2):236-301.

2. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Pulmonary fungal infections. Respirology. 2012;17(6):913-926.

3. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(3):556-569.

4. Prokopowicz GP, Bradley SF, Kauffman CA. Indolent zygomycosis associated with deferoxamine chelation therapy. Mycoses. 1994;37(11-12):427-431.

5. Hamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. Pulmonary mucormycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32(6):693-702.

6. Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):503-509.

7. Parfrey NA. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis. A clinicopathologic study of 33 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986;65(2):113-1

8. Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP, Hegde SS, Tedder SD, Lowe JE. Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(4):1044-1050.

9.

10. Reed C, Bryant R, Ibrahim AS, et al. Combination polyene-caspofungin treatment of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(3):364-371.

11. van Burik JA, Hare RS, Solomon HF, Corrado ML, Kontoyiannis DP. Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(7):e61-e65.

12. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS, Chin-Hong PV, et al. The Deferasirox-AmBisome Therapy for Mucormycosis (DEFEAT Mucor) study: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(3):715-722.

13. de Locht M, Boelaert JR, Schneider YJ. Iron uptake from ferrioxamine and from ferrirhizoferrin by germinating spores of Rhizopus microsporus. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994; 47(10):1843-1850.

KRd improves OS in relapsed/refractory MM

Adding carfilzomib (K) to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) can improve overall survival (OS) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Final results from the phase 3 ASPIRE trial showed that KRd reduced the risk of death by 21% and extended OS by 7.9 months, when compared to Rd.

In patients at first relapse, KRd was associated with an OS improvement of 11.4 months.

“Results from the final analysis of the phase 3 ASPIRE trial . . . are significant, as they further validate carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone as a standard-of-care regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said study author Keith Stewart, MBChB, of Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“Furthermore, these data showed that early use of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone at first relapse provided nearly 1 additional year of survival for patients, regardless of prior treatment with bortezomib or transplant.”

ASPIRE enrolled 792 MM patients who had received a median of 2 prior therapies (range, 1-3). They were randomized to receive KRd (n=396) or Rd (n=396). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms.

Details on patients and treatment, as well as interim results from ASPIRE, were reported at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting and published in NEJM in January 2015.

Treatment update

In the final analysis, there were 340 patients in the KRd arm and 358 in the Rd arm who stopped study treatment.

Reasons for discontinuation (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) were disease progression (n=188 and 224), adverse events (AEs, n=79 and 85), other reasons (n=61 and 35), withdrawn consent (n=10 and 12), and noncompliance (n=2 and 1).

A total of 182 patients in the KRd arm and 211 in the Rd arm received subsequent treatment for MM. These treatments were generally balanced between the KRd and Rd arms.

The median time to next treatment from the time of randomization was 39.0 months in the KRd arm and 24.4 months in the Rd arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.65 P<0.001).

Survival

Interim ASPIRE data had shown a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and a trend toward improved OS in patients who received KRd. Now, researchers have observed a significant improvement in both endpoints with KRd.

The data cutoff for the final analysis was April 28, 2017. For PFS, the median follow-up was 48.8 months in the KRd arm and 48.0 months in the Rd arm.

The median PFS was 26.1 months in the KRd arm and 16.6 months in the Rd arm (9.5-month improvement, HR=0.66; P<0.001). The 3-year PFS rates were 38.2% and 28.4%, respectively. And the 5-year PFS rates were 25.6% and 17.3%, respectively.

The median follow-up for OS was 67.1 months. The median OS was 48.3 months in the KRd arm and 40.4 months in the Rd arm (7.9-month improvement, HR=0.79, P=0.0045).

The researchers also performed subgroup analyses according to prior lines of therapy, prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, and prior transplant at first relapse.

In patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy, the median OS was 47.3 months in the KRd arm and 35.9 months in the Rd arm (11.4-month improvement, HR=0.81). For patients with 2 or more prior lines of therapy, the median OS was 48.8 months and 42.3 months, respectively (6.5-month improvement, HR=0.79).

Among patients with prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, the median OS was 45.9 months in the KRd arm and 33.9 months in the Rd arm (12-month improvement, HR=0.82). Among patients without prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, the median OS was 48.3 months and 40.4 months, respectively (7.9-month improvement, HR=0.80).

Among patients with prior transplant at first relapse, the median OS was 57.2 months in the KRd arm and 38.6 months in the Rd arm (18.6-month improvement, HR=0.71).

Safety

The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs was 98% in the KRd arm and 97.9% in the Rd arm. The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was 87% and 83.3%, respectively. The incidence of serious AEs was 65.3% and 56.8%, respectively.

Treatment discontinuation due to an AE occurred in 19.9% of patients in the KRd arm and 21.5% of patients in the Rd arm.

AEs of interest (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) included acute renal failure (9.2% and 7.7%), cardiac failure (7.1% and 4.1%), ischemic heart disease (6.9% and 4.6%), hypertension (17.1% and 8.7%), hematopoietic thrombocytopenia (32.7% and 26.2%), and peripheral neuropathy (18.9% and 17.2%).

Fatal AEs were reported in 11.5% of patients in the KRd arm and 10.8% of those in the Rd arm.

Fatal AEs reported in at least 2 patients in the KRd arm included (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) cardiac disorders (2.6% and 2.3%), pneumonia (1.5% and 0.8%), sepsis (0.8% for both), myocardial infarction (0.8% and 0.5%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (0.8% and 0%), death (0.5% for both), and cardiac arrest (0.5% and 0.3%).

This trial was funded by Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Adding carfilzomib (K) to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) can improve overall survival (OS) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Final results from the phase 3 ASPIRE trial showed that KRd reduced the risk of death by 21% and extended OS by 7.9 months, when compared to Rd.

In patients at first relapse, KRd was associated with an OS improvement of 11.4 months.

“Results from the final analysis of the phase 3 ASPIRE trial . . . are significant, as they further validate carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone as a standard-of-care regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said study author Keith Stewart, MBChB, of Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“Furthermore, these data showed that early use of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone at first relapse provided nearly 1 additional year of survival for patients, regardless of prior treatment with bortezomib or transplant.”

ASPIRE enrolled 792 MM patients who had received a median of 2 prior therapies (range, 1-3). They were randomized to receive KRd (n=396) or Rd (n=396). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms.

Details on patients and treatment, as well as interim results from ASPIRE, were reported at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting and published in NEJM in January 2015.

Treatment update

In the final analysis, there were 340 patients in the KRd arm and 358 in the Rd arm who stopped study treatment.

Reasons for discontinuation (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) were disease progression (n=188 and 224), adverse events (AEs, n=79 and 85), other reasons (n=61 and 35), withdrawn consent (n=10 and 12), and noncompliance (n=2 and 1).

A total of 182 patients in the KRd arm and 211 in the Rd arm received subsequent treatment for MM. These treatments were generally balanced between the KRd and Rd arms.

The median time to next treatment from the time of randomization was 39.0 months in the KRd arm and 24.4 months in the Rd arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.65 P<0.001).

Survival

Interim ASPIRE data had shown a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and a trend toward improved OS in patients who received KRd. Now, researchers have observed a significant improvement in both endpoints with KRd.

The data cutoff for the final analysis was April 28, 2017. For PFS, the median follow-up was 48.8 months in the KRd arm and 48.0 months in the Rd arm.

The median PFS was 26.1 months in the KRd arm and 16.6 months in the Rd arm (9.5-month improvement, HR=0.66; P<0.001). The 3-year PFS rates were 38.2% and 28.4%, respectively. And the 5-year PFS rates were 25.6% and 17.3%, respectively.

The median follow-up for OS was 67.1 months. The median OS was 48.3 months in the KRd arm and 40.4 months in the Rd arm (7.9-month improvement, HR=0.79, P=0.0045).

The researchers also performed subgroup analyses according to prior lines of therapy, prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, and prior transplant at first relapse.

In patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy, the median OS was 47.3 months in the KRd arm and 35.9 months in the Rd arm (11.4-month improvement, HR=0.81). For patients with 2 or more prior lines of therapy, the median OS was 48.8 months and 42.3 months, respectively (6.5-month improvement, HR=0.79).

Among patients with prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, the median OS was 45.9 months in the KRd arm and 33.9 months in the Rd arm (12-month improvement, HR=0.82). Among patients without prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, the median OS was 48.3 months and 40.4 months, respectively (7.9-month improvement, HR=0.80).

Among patients with prior transplant at first relapse, the median OS was 57.2 months in the KRd arm and 38.6 months in the Rd arm (18.6-month improvement, HR=0.71).

Safety

The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs was 98% in the KRd arm and 97.9% in the Rd arm. The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was 87% and 83.3%, respectively. The incidence of serious AEs was 65.3% and 56.8%, respectively.

Treatment discontinuation due to an AE occurred in 19.9% of patients in the KRd arm and 21.5% of patients in the Rd arm.

AEs of interest (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) included acute renal failure (9.2% and 7.7%), cardiac failure (7.1% and 4.1%), ischemic heart disease (6.9% and 4.6%), hypertension (17.1% and 8.7%), hematopoietic thrombocytopenia (32.7% and 26.2%), and peripheral neuropathy (18.9% and 17.2%).

Fatal AEs were reported in 11.5% of patients in the KRd arm and 10.8% of those in the Rd arm.

Fatal AEs reported in at least 2 patients in the KRd arm included (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) cardiac disorders (2.6% and 2.3%), pneumonia (1.5% and 0.8%), sepsis (0.8% for both), myocardial infarction (0.8% and 0.5%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (0.8% and 0%), death (0.5% for both), and cardiac arrest (0.5% and 0.3%).

This trial was funded by Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Adding carfilzomib (K) to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) can improve overall survival (OS) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Final results from the phase 3 ASPIRE trial showed that KRd reduced the risk of death by 21% and extended OS by 7.9 months, when compared to Rd.

In patients at first relapse, KRd was associated with an OS improvement of 11.4 months.

“Results from the final analysis of the phase 3 ASPIRE trial . . . are significant, as they further validate carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone as a standard-of-care regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said study author Keith Stewart, MBChB, of Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“Furthermore, these data showed that early use of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone at first relapse provided nearly 1 additional year of survival for patients, regardless of prior treatment with bortezomib or transplant.”

ASPIRE enrolled 792 MM patients who had received a median of 2 prior therapies (range, 1-3). They were randomized to receive KRd (n=396) or Rd (n=396). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms.

Details on patients and treatment, as well as interim results from ASPIRE, were reported at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting and published in NEJM in January 2015.

Treatment update

In the final analysis, there were 340 patients in the KRd arm and 358 in the Rd arm who stopped study treatment.

Reasons for discontinuation (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) were disease progression (n=188 and 224), adverse events (AEs, n=79 and 85), other reasons (n=61 and 35), withdrawn consent (n=10 and 12), and noncompliance (n=2 and 1).

A total of 182 patients in the KRd arm and 211 in the Rd arm received subsequent treatment for MM. These treatments were generally balanced between the KRd and Rd arms.

The median time to next treatment from the time of randomization was 39.0 months in the KRd arm and 24.4 months in the Rd arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.65 P<0.001).

Survival

Interim ASPIRE data had shown a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and a trend toward improved OS in patients who received KRd. Now, researchers have observed a significant improvement in both endpoints with KRd.

The data cutoff for the final analysis was April 28, 2017. For PFS, the median follow-up was 48.8 months in the KRd arm and 48.0 months in the Rd arm.

The median PFS was 26.1 months in the KRd arm and 16.6 months in the Rd arm (9.5-month improvement, HR=0.66; P<0.001). The 3-year PFS rates were 38.2% and 28.4%, respectively. And the 5-year PFS rates were 25.6% and 17.3%, respectively.

The median follow-up for OS was 67.1 months. The median OS was 48.3 months in the KRd arm and 40.4 months in the Rd arm (7.9-month improvement, HR=0.79, P=0.0045).

The researchers also performed subgroup analyses according to prior lines of therapy, prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, and prior transplant at first relapse.

In patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy, the median OS was 47.3 months in the KRd arm and 35.9 months in the Rd arm (11.4-month improvement, HR=0.81). For patients with 2 or more prior lines of therapy, the median OS was 48.8 months and 42.3 months, respectively (6.5-month improvement, HR=0.79).

Among patients with prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, the median OS was 45.9 months in the KRd arm and 33.9 months in the Rd arm (12-month improvement, HR=0.82). Among patients without prior bortezomib exposure at first relapse, the median OS was 48.3 months and 40.4 months, respectively (7.9-month improvement, HR=0.80).

Among patients with prior transplant at first relapse, the median OS was 57.2 months in the KRd arm and 38.6 months in the Rd arm (18.6-month improvement, HR=0.71).

Safety

The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs was 98% in the KRd arm and 97.9% in the Rd arm. The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was 87% and 83.3%, respectively. The incidence of serious AEs was 65.3% and 56.8%, respectively.

Treatment discontinuation due to an AE occurred in 19.9% of patients in the KRd arm and 21.5% of patients in the Rd arm.

AEs of interest (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) included acute renal failure (9.2% and 7.7%), cardiac failure (7.1% and 4.1%), ischemic heart disease (6.9% and 4.6%), hypertension (17.1% and 8.7%), hematopoietic thrombocytopenia (32.7% and 26.2%), and peripheral neuropathy (18.9% and 17.2%).

Fatal AEs were reported in 11.5% of patients in the KRd arm and 10.8% of those in the Rd arm.

Fatal AEs reported in at least 2 patients in the KRd arm included (in the KRd and Rd arms, respectively) cardiac disorders (2.6% and 2.3%), pneumonia (1.5% and 0.8%), sepsis (0.8% for both), myocardial infarction (0.8% and 0.5%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (0.8% and 0%), death (0.5% for both), and cardiac arrest (0.5% and 0.3%).

This trial was funded by Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

FDA surveillance shows how rivaroxaban compares to warfarin

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Mini-Sentinel surveillance system has revealed no new safety concerns associated with rivaroxaban use in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.