User login

Meaningful endometriosis treatment requires a holistic approach and an understanding of chronic pain

Although it has been more than 100 years since endometriosis was first described in the literature, deciphering the mechanisms that cause pain in women with this enigmatic disease is an ongoing pursuit.

Pain is the most debilitating symptom of endometriosis.1,2 In many cases, it has a profoundly negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, and contributes significantly to disease burden, as well as to personal and societal costs from lost productivity.3,4 Women with endometriosis often experience chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and subfertility.5 The majority of women with the disease also have one or more comorbidities, including adenomyosis, adhesive disease, and other pelvic pain conditions such as interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pelvic floor myalgia.6-8

Recent studies have yielded new insights into the development of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. The role of peritoneal inflammation, de novo innervation of endometriosis implants, and changes in the central nervous system are becoming increasingly clear.5,9,10 These discoveries have important treatment implications.

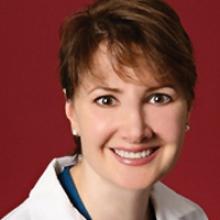

In this article, Andrea J. Rapkin, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Founder and Director of the UCLA Pelvic Pain Center, offers her expert opinion on the findings of key studies and their clinical implications, including the importance of a multidisciplinary treatment approach that focuses on the whole patient.

Q What mechanisms underlie the chronic pain that many women with endometriosis feel?

Although pain is the primary symptom experienced by women with endometriosis, the disease burden and symptom severity do not often correlate.11,12 “This was the first conundrum presented to clinicians,” noted Dr. Rapkin. “In fact, we do not know the true prevalence of endometriosis because women with endometriosis only come to diagnosis either based on pain or infertility. When infertility is the problem, very often we are surprised by how much disease is present in an individual with either no pain or minimal pain. Conversely, in other individuals with very severe pain, upon laparoscopic surgery, have minimal or mild endometriosis.”

Efforts to solve this clinical puzzle began decades ago. “Dr. Michael Vernon discovered that the small, red, endometriosis implants that looked like petechial hemorrhages produced more prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in vitro than the older black-brown lesions. PGE2 is a pain-producing (algesic) chemical produced after cytokines stimulation,” said Dr. Rapkin. “This was the first evidence that, yes, there is a reason for pain in many individuals with lower-stage disease.”

“Prostaglandins are known to be a major cause of dysmenorrhea. Prostaglandins induce uterine cramping, sensitize nerve endings, and promote other inflammatory factors responsible for attracting monocytes that become macrophages, further contributing to inflammation,” Dr. Rapkin continued. “PGE2 also stimulates the enzyme aromatase, which allows androgens to be converted to estrogen, which promotes growth of endometriotic lesions. This is a self-feeding aspect of endometriosis.”

Continue to: These discoveries were followed by the realization that deeply infiltrating endometriosis...

These discoveries were followed by the realization that deeply infiltrating endometriosis (defined by disease infiltration of more than 5 mm, often in the uterosacral ligaments) was more likely to be painful than superficial disease, said Dr. Rapkin. “In some women with endometriosis, the disease we see laparoscopically is really the tip of the iceberg.”

In 2005, landmark studies performed by Karen J. Berkley, PhD, were summarized in a paper coauthored by Dr. Berkley, Dr. Rapkin, and Raymond E. Papka, PhD.13 “In a rodent model where endometriosis was developed by suturing pieces of endometrium in the mesentery, the endometriosis implants developed a vascular supply and a nerve supply. These nerves were not just functioning to govern the dilation and contraction of the blood vessels (in other words the sympathetic type nerves), but these nerves stained for neurotransmitters associated with pain (algesic agents, such as substance P and CGRP),” said Dr. Rapkin. “At UCLA, we acquired tissue from women with endometriosis and analyzed in Dr. Papka’s lab. Those tissues also showed nerves staining for pain-producing chemicals.” Other studies performed worldwide also demonstrated nerve endings with neurotrophic and algesic chemicals in endometriotic tissues. In addition to prostaglandins and cytokines, increased expression of various neuropeptides, neurotrophins, and alterations in ion channels contribute to hypersensitivity and pain.

Q What other chronic pain conditions might women with endometriosis experience?

Overlapping chronic pain conditions are common in women with endometriosis. “There is a very high co-occurrence of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome,” said Dr. Rapkin. “Irritable bowel syndrome is more common in women with endometriosis, as is vulvodynia. Fibromyalgia, migraine headache, temporo-mandibular joint pain (TMJ), anxiety, and depression also commonly co-occur in women with endometriosis.”

“Two concepts may be relevant to why these overlapping pain conditions develop,” Dr. Rapkin continued. “First, visceral sensitization: If one organ or tissue is inflamed and becomes hyperalgesic then other organs in the adjacent region with shared thoracolumbar and sacral innervation can become sensitized through shared cell bodies in the spinal cord, cross-sensitization in the cord, or at higher regions of the CNS. In addition, visceral somatic conversion occurs, whereby somatic tissues such as muscles and subcutaneous tissues with the same nerve supply as the affected organs become sensitized. This process may explain why abdominal wall and pelvic floor muscles become painful. The involvement of surrounding musculature is an important contributor to the pain in many women with endometriosis.”

“Finally, genetic studies of alterations in genes that encode for chemicals affecting the sensitivity and perception of pain are shedding light on the development of chronic pain. Ultimately these studies will advance our understanding of pain related to endometriosis.”

Continue to: Q How have new understandings about the pain mechanisms...

Q How have new understandings about the pain mechanisms involved with endometriosis-caused pelvic pain improved treatment?

According to Dr. Rapkin, the increased understanding of the mechanisms involved in endometriosis-associated pain gained from these key studies led to a paradigm shift, with endometriosis being viewed not just as a condition with mechanical hypersensitivity due to altered anatomy and inflammation but also as a neurologic condition, or a nerve pain condition with peripheral and central sensitization. “This means there is upregulation or hyperactivity both in the periphery (in the pelvis) and centrally (in the spinal cord and brain),” said Dr. Rapkin.

“In the periphery, the endometriotic lesions develop an afferent sensory innervation and communicate with the brain. Stimulation of these nerves by the inflammatory milieu contributes to pain.” Dr. Rapkin noted research by Maria Adele Giamberardino, which demonstrated that women with endometriosis and pain have a lower threshold for feeling pain in the tissues overlying the pelvis (the abdominal wall and back).14 This also has been shown by Dr. Berkley in rodents given endometriosis.

“The muscles develop trigger points and tender hyperalgesic points as part of the sensitization process. In addition, distant sensitization develops—women with pelvic pain and endometriosis have a lower threshold for sensing experimental pain in areas outside the pelvis, for example the back, leg, or shoulder. These discoveries clearly reflect up regulation for pain processing in the central nervous system.”

Dr. Rapkin also pointed to research published in 2016 by Sawson As-Sanie, MD, MPH, that showed an association between endometriosis-associated pelvic pain and altered brain chemistry and function.16 “Dr. As-Sanie demonstrated a decrease in gray matter volume in key neural pain processing areas in the brain in women with pain with endometriosis. This was not found in women with endometriosis who did not have pain,” she said. “Altered connectivity in brain areas related to perception and inhibition of pain is important in maintaining pain. Dr. As-Sanie’s studies also found that these changes are correlated with anxiety, depression, and pain intensity in patients with endometriosis and chronic pain.”

Continue to: Q What are some newer treatment approaches to chronic pain with endometriosis?

Q What are some newer treatment approaches to chronic pain with endometriosis?

“Multidisciplinary approaches to endometriosis-related pain are important,” said Dr. Rapkin. “Although it is important to excise or cauterize endometriosis lesions, or debulk as much as can safely be removed during laparoscopic surgery, it is now standard of care that medical therapy, not surgery, is the first approach to treatment. Endometriosis is a chronic condition. Inflammatory factors will continue to proliferate in patients who menstruate and produce high levels of estrogen with ovulation. The goal of medical therapy is to decrease the levels of estrogen that contribute to maintenance and proliferation of the implants. We want to suppress estrogen in a way that is compatible with long-term quality of life for our patients. Wiping out estrogen and placing patients into a chemical or surgical menopause for most of their reproductive years is not desirable.”

Approaches to hormonally modulate endometriosis include combined hormonal contraceptives and progestin-only medications, such as the levonogestrol-containing IUD, progestin-containing contraceptive implants, injections, or tablets. Second-line medical therapy consists of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists that can be used for 6 months to 2 years and allows for further lowering of estrogen levels. These may not provide sufficient pain relief for some patients. “There is some evidence from Dr. Giamberadino’s studies that after women with dysmenorrhea were treated with oral contraceptives, the abdominal wall hyperalgesia decreased,” said Dr. Rapkin. “The question is, why don’t we see this in all patients? We come to the realization that endometriosis has to be treated as a neurologically mediated disorder. We have to treat the peripheral and central sensitization in a multidisciplinary way.”

A holistic approach to endometriosis is a new and exciting area for the field, said Dr. Rapkin. “We have to treat ‘bottom-up’, and ‘top-down.’ Bottom-up means we are addressing the peripheral factors that contribute to pain: endometriotic lesions, other pelvic organ pain, myofascial pain, trigger points, the tender points, and the muscle dysfunction in the abdominal wall, the back, and the pelvic floor. Pelvic floor physical therapists help women with pain and endometriosis. Often, women with endometriosis have myofascial pain and pain related to the other comorbid pain conditions they may have developed. Peripheral nerve blocks and medications used for neuropathic pain that alter nerve firing can be helpful in many situations. Pain can be augmented by cognitions and beliefs about pain, and by anxiety and depression. So the top-down approach addresses the cognitions, depression, and anxiety. We do not consider endometriosis a psychosomatic condition, but we know that if you do not address the central upregulation, including anxiety and depression, we may not get anywhere.”

“Interestingly, neurotransmitters and brain regions governing mood contribute to nerve pain. Medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants, and calcium channel blocking agents may prove fruitful. Cognitive behavioral therapy is another approach—to stimulate the prefrontal cortex, the area that is involved in pain inhibition, and other areas of the brain that may produce endogenous opioids to help with inhibiting pain. Bringing in complementary approaches is very important—for example, mindfulness-based meditation or yoga. There is growing evidence for acupuncture as well. Physical therapists, pain psychologists, anesthesiologists, or gynecologists who are facile with nerve blocks, to help tone down hyperalgesic tissues, in addition to medical and surgical therapy, have the possibility of really improving the lives of women with endometriosis.”

Q What key pearls would you like to share with readers?

“It is important to evaluate the entire individual,” she said. “Do not just viscerally focus on the uterus, the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the peritoneum; investigate the adjacent organs and somatic tissues. Think about the abdominal wall, think about the pelvic floor. Learn how to evaluate these structures. There are simple evaluation techniques that gynecologists can learn and should include with every patient with pelvic pain, whether or not they are suspected of having endometriosis. You also want to get a complete history to determine if there are other co-occurring pain conditions. If there are, it is already a sign that there may be central sensitization.”

“Very often, it is necessary to bring in a pain psychologist—not because the disease is psychosomatic but because therapy can help the patient to learn how to use their brain to erase pain memory, and of course to address the concomitant anxiety, depression, and social isolation that happens with pain.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Olive DL, Lindheim SR, Pritts EA. New medical treatments for endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):319-328.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447): 1789-1799.

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366-373.e8.

- Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1292–1299.

- Bruner-Tran KL, Mokshagundam S, Herington JL. Rodent models of experimental endometriosis: identifying mechanisms of disease and therapeutic targets. Curr Womens Health Rev. 2018;14(2):173-188.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2715-2724.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(2):164-185.

- Tirlapur SA, Kuhrt K, Chaliha C. The ‘evil twin syndrome’ in chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review of prevalence studies of bladder pain syndrome and endometriosis. Int J Surg. 2013;11(3):233-237.

- Coxon L, Horne AW, Vincent K. Pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated pain: a review of pelvic and central nervous system mechanisms. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Feb 15. pii: S1521-6934(18)30032-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.014. [Epub ahead of print]

- Yan D, Liu X, Guo SW. Nerve fibers and endometriotic lesions: partners in crime in inflicting pains in women with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:14-24.

- Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266-271.

- Fedele L, Parazzini F, Bianchi S. Stage and localization of pelvic endometriosis and pain. Fertil Steril. 1990;53(1):155-158.

- Berkley KJ, Rapkin AJ, Papka RE. The pains of endometriosis. Science. 2005;308(5728):1587-1589.

- Giamberardino MA, Tana C, Costantini R. Pain thresholds in women with chronic pelvic pain. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26(4):253-259.

- Giamberardino MA, Berkley KJ, Affaitati G. Influence of endometriosis on pain behaviors and muscle hyperalgesia induced by a ureteral calculosis in female rats. Pain. 2002;95(3):247-257.

- As-Sanie S, Kim J, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Functional connectivity is associated with altered brain chemistry in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(1):1-13.

Although it has been more than 100 years since endometriosis was first described in the literature, deciphering the mechanisms that cause pain in women with this enigmatic disease is an ongoing pursuit.

Pain is the most debilitating symptom of endometriosis.1,2 In many cases, it has a profoundly negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, and contributes significantly to disease burden, as well as to personal and societal costs from lost productivity.3,4 Women with endometriosis often experience chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and subfertility.5 The majority of women with the disease also have one or more comorbidities, including adenomyosis, adhesive disease, and other pelvic pain conditions such as interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pelvic floor myalgia.6-8

Recent studies have yielded new insights into the development of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. The role of peritoneal inflammation, de novo innervation of endometriosis implants, and changes in the central nervous system are becoming increasingly clear.5,9,10 These discoveries have important treatment implications.

In this article, Andrea J. Rapkin, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Founder and Director of the UCLA Pelvic Pain Center, offers her expert opinion on the findings of key studies and their clinical implications, including the importance of a multidisciplinary treatment approach that focuses on the whole patient.

Q What mechanisms underlie the chronic pain that many women with endometriosis feel?

Although pain is the primary symptom experienced by women with endometriosis, the disease burden and symptom severity do not often correlate.11,12 “This was the first conundrum presented to clinicians,” noted Dr. Rapkin. “In fact, we do not know the true prevalence of endometriosis because women with endometriosis only come to diagnosis either based on pain or infertility. When infertility is the problem, very often we are surprised by how much disease is present in an individual with either no pain or minimal pain. Conversely, in other individuals with very severe pain, upon laparoscopic surgery, have minimal or mild endometriosis.”

Efforts to solve this clinical puzzle began decades ago. “Dr. Michael Vernon discovered that the small, red, endometriosis implants that looked like petechial hemorrhages produced more prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in vitro than the older black-brown lesions. PGE2 is a pain-producing (algesic) chemical produced after cytokines stimulation,” said Dr. Rapkin. “This was the first evidence that, yes, there is a reason for pain in many individuals with lower-stage disease.”

“Prostaglandins are known to be a major cause of dysmenorrhea. Prostaglandins induce uterine cramping, sensitize nerve endings, and promote other inflammatory factors responsible for attracting monocytes that become macrophages, further contributing to inflammation,” Dr. Rapkin continued. “PGE2 also stimulates the enzyme aromatase, which allows androgens to be converted to estrogen, which promotes growth of endometriotic lesions. This is a self-feeding aspect of endometriosis.”

Continue to: These discoveries were followed by the realization that deeply infiltrating endometriosis...

These discoveries were followed by the realization that deeply infiltrating endometriosis (defined by disease infiltration of more than 5 mm, often in the uterosacral ligaments) was more likely to be painful than superficial disease, said Dr. Rapkin. “In some women with endometriosis, the disease we see laparoscopically is really the tip of the iceberg.”

In 2005, landmark studies performed by Karen J. Berkley, PhD, were summarized in a paper coauthored by Dr. Berkley, Dr. Rapkin, and Raymond E. Papka, PhD.13 “In a rodent model where endometriosis was developed by suturing pieces of endometrium in the mesentery, the endometriosis implants developed a vascular supply and a nerve supply. These nerves were not just functioning to govern the dilation and contraction of the blood vessels (in other words the sympathetic type nerves), but these nerves stained for neurotransmitters associated with pain (algesic agents, such as substance P and CGRP),” said Dr. Rapkin. “At UCLA, we acquired tissue from women with endometriosis and analyzed in Dr. Papka’s lab. Those tissues also showed nerves staining for pain-producing chemicals.” Other studies performed worldwide also demonstrated nerve endings with neurotrophic and algesic chemicals in endometriotic tissues. In addition to prostaglandins and cytokines, increased expression of various neuropeptides, neurotrophins, and alterations in ion channels contribute to hypersensitivity and pain.

Q What other chronic pain conditions might women with endometriosis experience?

Overlapping chronic pain conditions are common in women with endometriosis. “There is a very high co-occurrence of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome,” said Dr. Rapkin. “Irritable bowel syndrome is more common in women with endometriosis, as is vulvodynia. Fibromyalgia, migraine headache, temporo-mandibular joint pain (TMJ), anxiety, and depression also commonly co-occur in women with endometriosis.”

“Two concepts may be relevant to why these overlapping pain conditions develop,” Dr. Rapkin continued. “First, visceral sensitization: If one organ or tissue is inflamed and becomes hyperalgesic then other organs in the adjacent region with shared thoracolumbar and sacral innervation can become sensitized through shared cell bodies in the spinal cord, cross-sensitization in the cord, or at higher regions of the CNS. In addition, visceral somatic conversion occurs, whereby somatic tissues such as muscles and subcutaneous tissues with the same nerve supply as the affected organs become sensitized. This process may explain why abdominal wall and pelvic floor muscles become painful. The involvement of surrounding musculature is an important contributor to the pain in many women with endometriosis.”

“Finally, genetic studies of alterations in genes that encode for chemicals affecting the sensitivity and perception of pain are shedding light on the development of chronic pain. Ultimately these studies will advance our understanding of pain related to endometriosis.”

Continue to: Q How have new understandings about the pain mechanisms...

Q How have new understandings about the pain mechanisms involved with endometriosis-caused pelvic pain improved treatment?

According to Dr. Rapkin, the increased understanding of the mechanisms involved in endometriosis-associated pain gained from these key studies led to a paradigm shift, with endometriosis being viewed not just as a condition with mechanical hypersensitivity due to altered anatomy and inflammation but also as a neurologic condition, or a nerve pain condition with peripheral and central sensitization. “This means there is upregulation or hyperactivity both in the periphery (in the pelvis) and centrally (in the spinal cord and brain),” said Dr. Rapkin.

“In the periphery, the endometriotic lesions develop an afferent sensory innervation and communicate with the brain. Stimulation of these nerves by the inflammatory milieu contributes to pain.” Dr. Rapkin noted research by Maria Adele Giamberardino, which demonstrated that women with endometriosis and pain have a lower threshold for feeling pain in the tissues overlying the pelvis (the abdominal wall and back).14 This also has been shown by Dr. Berkley in rodents given endometriosis.

“The muscles develop trigger points and tender hyperalgesic points as part of the sensitization process. In addition, distant sensitization develops—women with pelvic pain and endometriosis have a lower threshold for sensing experimental pain in areas outside the pelvis, for example the back, leg, or shoulder. These discoveries clearly reflect up regulation for pain processing in the central nervous system.”

Dr. Rapkin also pointed to research published in 2016 by Sawson As-Sanie, MD, MPH, that showed an association between endometriosis-associated pelvic pain and altered brain chemistry and function.16 “Dr. As-Sanie demonstrated a decrease in gray matter volume in key neural pain processing areas in the brain in women with pain with endometriosis. This was not found in women with endometriosis who did not have pain,” she said. “Altered connectivity in brain areas related to perception and inhibition of pain is important in maintaining pain. Dr. As-Sanie’s studies also found that these changes are correlated with anxiety, depression, and pain intensity in patients with endometriosis and chronic pain.”

Continue to: Q What are some newer treatment approaches to chronic pain with endometriosis?

Q What are some newer treatment approaches to chronic pain with endometriosis?

“Multidisciplinary approaches to endometriosis-related pain are important,” said Dr. Rapkin. “Although it is important to excise or cauterize endometriosis lesions, or debulk as much as can safely be removed during laparoscopic surgery, it is now standard of care that medical therapy, not surgery, is the first approach to treatment. Endometriosis is a chronic condition. Inflammatory factors will continue to proliferate in patients who menstruate and produce high levels of estrogen with ovulation. The goal of medical therapy is to decrease the levels of estrogen that contribute to maintenance and proliferation of the implants. We want to suppress estrogen in a way that is compatible with long-term quality of life for our patients. Wiping out estrogen and placing patients into a chemical or surgical menopause for most of their reproductive years is not desirable.”

Approaches to hormonally modulate endometriosis include combined hormonal contraceptives and progestin-only medications, such as the levonogestrol-containing IUD, progestin-containing contraceptive implants, injections, or tablets. Second-line medical therapy consists of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists that can be used for 6 months to 2 years and allows for further lowering of estrogen levels. These may not provide sufficient pain relief for some patients. “There is some evidence from Dr. Giamberadino’s studies that after women with dysmenorrhea were treated with oral contraceptives, the abdominal wall hyperalgesia decreased,” said Dr. Rapkin. “The question is, why don’t we see this in all patients? We come to the realization that endometriosis has to be treated as a neurologically mediated disorder. We have to treat the peripheral and central sensitization in a multidisciplinary way.”

A holistic approach to endometriosis is a new and exciting area for the field, said Dr. Rapkin. “We have to treat ‘bottom-up’, and ‘top-down.’ Bottom-up means we are addressing the peripheral factors that contribute to pain: endometriotic lesions, other pelvic organ pain, myofascial pain, trigger points, the tender points, and the muscle dysfunction in the abdominal wall, the back, and the pelvic floor. Pelvic floor physical therapists help women with pain and endometriosis. Often, women with endometriosis have myofascial pain and pain related to the other comorbid pain conditions they may have developed. Peripheral nerve blocks and medications used for neuropathic pain that alter nerve firing can be helpful in many situations. Pain can be augmented by cognitions and beliefs about pain, and by anxiety and depression. So the top-down approach addresses the cognitions, depression, and anxiety. We do not consider endometriosis a psychosomatic condition, but we know that if you do not address the central upregulation, including anxiety and depression, we may not get anywhere.”

“Interestingly, neurotransmitters and brain regions governing mood contribute to nerve pain. Medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants, and calcium channel blocking agents may prove fruitful. Cognitive behavioral therapy is another approach—to stimulate the prefrontal cortex, the area that is involved in pain inhibition, and other areas of the brain that may produce endogenous opioids to help with inhibiting pain. Bringing in complementary approaches is very important—for example, mindfulness-based meditation or yoga. There is growing evidence for acupuncture as well. Physical therapists, pain psychologists, anesthesiologists, or gynecologists who are facile with nerve blocks, to help tone down hyperalgesic tissues, in addition to medical and surgical therapy, have the possibility of really improving the lives of women with endometriosis.”

Q What key pearls would you like to share with readers?

“It is important to evaluate the entire individual,” she said. “Do not just viscerally focus on the uterus, the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the peritoneum; investigate the adjacent organs and somatic tissues. Think about the abdominal wall, think about the pelvic floor. Learn how to evaluate these structures. There are simple evaluation techniques that gynecologists can learn and should include with every patient with pelvic pain, whether or not they are suspected of having endometriosis. You also want to get a complete history to determine if there are other co-occurring pain conditions. If there are, it is already a sign that there may be central sensitization.”

“Very often, it is necessary to bring in a pain psychologist—not because the disease is psychosomatic but because therapy can help the patient to learn how to use their brain to erase pain memory, and of course to address the concomitant anxiety, depression, and social isolation that happens with pain.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Although it has been more than 100 years since endometriosis was first described in the literature, deciphering the mechanisms that cause pain in women with this enigmatic disease is an ongoing pursuit.

Pain is the most debilitating symptom of endometriosis.1,2 In many cases, it has a profoundly negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, and contributes significantly to disease burden, as well as to personal and societal costs from lost productivity.3,4 Women with endometriosis often experience chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and subfertility.5 The majority of women with the disease also have one or more comorbidities, including adenomyosis, adhesive disease, and other pelvic pain conditions such as interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pelvic floor myalgia.6-8

Recent studies have yielded new insights into the development of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. The role of peritoneal inflammation, de novo innervation of endometriosis implants, and changes in the central nervous system are becoming increasingly clear.5,9,10 These discoveries have important treatment implications.

In this article, Andrea J. Rapkin, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Founder and Director of the UCLA Pelvic Pain Center, offers her expert opinion on the findings of key studies and their clinical implications, including the importance of a multidisciplinary treatment approach that focuses on the whole patient.

Q What mechanisms underlie the chronic pain that many women with endometriosis feel?

Although pain is the primary symptom experienced by women with endometriosis, the disease burden and symptom severity do not often correlate.11,12 “This was the first conundrum presented to clinicians,” noted Dr. Rapkin. “In fact, we do not know the true prevalence of endometriosis because women with endometriosis only come to diagnosis either based on pain or infertility. When infertility is the problem, very often we are surprised by how much disease is present in an individual with either no pain or minimal pain. Conversely, in other individuals with very severe pain, upon laparoscopic surgery, have minimal or mild endometriosis.”

Efforts to solve this clinical puzzle began decades ago. “Dr. Michael Vernon discovered that the small, red, endometriosis implants that looked like petechial hemorrhages produced more prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in vitro than the older black-brown lesions. PGE2 is a pain-producing (algesic) chemical produced after cytokines stimulation,” said Dr. Rapkin. “This was the first evidence that, yes, there is a reason for pain in many individuals with lower-stage disease.”

“Prostaglandins are known to be a major cause of dysmenorrhea. Prostaglandins induce uterine cramping, sensitize nerve endings, and promote other inflammatory factors responsible for attracting monocytes that become macrophages, further contributing to inflammation,” Dr. Rapkin continued. “PGE2 also stimulates the enzyme aromatase, which allows androgens to be converted to estrogen, which promotes growth of endometriotic lesions. This is a self-feeding aspect of endometriosis.”

Continue to: These discoveries were followed by the realization that deeply infiltrating endometriosis...

These discoveries were followed by the realization that deeply infiltrating endometriosis (defined by disease infiltration of more than 5 mm, often in the uterosacral ligaments) was more likely to be painful than superficial disease, said Dr. Rapkin. “In some women with endometriosis, the disease we see laparoscopically is really the tip of the iceberg.”

In 2005, landmark studies performed by Karen J. Berkley, PhD, were summarized in a paper coauthored by Dr. Berkley, Dr. Rapkin, and Raymond E. Papka, PhD.13 “In a rodent model where endometriosis was developed by suturing pieces of endometrium in the mesentery, the endometriosis implants developed a vascular supply and a nerve supply. These nerves were not just functioning to govern the dilation and contraction of the blood vessels (in other words the sympathetic type nerves), but these nerves stained for neurotransmitters associated with pain (algesic agents, such as substance P and CGRP),” said Dr. Rapkin. “At UCLA, we acquired tissue from women with endometriosis and analyzed in Dr. Papka’s lab. Those tissues also showed nerves staining for pain-producing chemicals.” Other studies performed worldwide also demonstrated nerve endings with neurotrophic and algesic chemicals in endometriotic tissues. In addition to prostaglandins and cytokines, increased expression of various neuropeptides, neurotrophins, and alterations in ion channels contribute to hypersensitivity and pain.

Q What other chronic pain conditions might women with endometriosis experience?

Overlapping chronic pain conditions are common in women with endometriosis. “There is a very high co-occurrence of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome,” said Dr. Rapkin. “Irritable bowel syndrome is more common in women with endometriosis, as is vulvodynia. Fibromyalgia, migraine headache, temporo-mandibular joint pain (TMJ), anxiety, and depression also commonly co-occur in women with endometriosis.”

“Two concepts may be relevant to why these overlapping pain conditions develop,” Dr. Rapkin continued. “First, visceral sensitization: If one organ or tissue is inflamed and becomes hyperalgesic then other organs in the adjacent region with shared thoracolumbar and sacral innervation can become sensitized through shared cell bodies in the spinal cord, cross-sensitization in the cord, or at higher regions of the CNS. In addition, visceral somatic conversion occurs, whereby somatic tissues such as muscles and subcutaneous tissues with the same nerve supply as the affected organs become sensitized. This process may explain why abdominal wall and pelvic floor muscles become painful. The involvement of surrounding musculature is an important contributor to the pain in many women with endometriosis.”

“Finally, genetic studies of alterations in genes that encode for chemicals affecting the sensitivity and perception of pain are shedding light on the development of chronic pain. Ultimately these studies will advance our understanding of pain related to endometriosis.”

Continue to: Q How have new understandings about the pain mechanisms...

Q How have new understandings about the pain mechanisms involved with endometriosis-caused pelvic pain improved treatment?

According to Dr. Rapkin, the increased understanding of the mechanisms involved in endometriosis-associated pain gained from these key studies led to a paradigm shift, with endometriosis being viewed not just as a condition with mechanical hypersensitivity due to altered anatomy and inflammation but also as a neurologic condition, or a nerve pain condition with peripheral and central sensitization. “This means there is upregulation or hyperactivity both in the periphery (in the pelvis) and centrally (in the spinal cord and brain),” said Dr. Rapkin.

“In the periphery, the endometriotic lesions develop an afferent sensory innervation and communicate with the brain. Stimulation of these nerves by the inflammatory milieu contributes to pain.” Dr. Rapkin noted research by Maria Adele Giamberardino, which demonstrated that women with endometriosis and pain have a lower threshold for feeling pain in the tissues overlying the pelvis (the abdominal wall and back).14 This also has been shown by Dr. Berkley in rodents given endometriosis.

“The muscles develop trigger points and tender hyperalgesic points as part of the sensitization process. In addition, distant sensitization develops—women with pelvic pain and endometriosis have a lower threshold for sensing experimental pain in areas outside the pelvis, for example the back, leg, or shoulder. These discoveries clearly reflect up regulation for pain processing in the central nervous system.”

Dr. Rapkin also pointed to research published in 2016 by Sawson As-Sanie, MD, MPH, that showed an association between endometriosis-associated pelvic pain and altered brain chemistry and function.16 “Dr. As-Sanie demonstrated a decrease in gray matter volume in key neural pain processing areas in the brain in women with pain with endometriosis. This was not found in women with endometriosis who did not have pain,” she said. “Altered connectivity in brain areas related to perception and inhibition of pain is important in maintaining pain. Dr. As-Sanie’s studies also found that these changes are correlated with anxiety, depression, and pain intensity in patients with endometriosis and chronic pain.”

Continue to: Q What are some newer treatment approaches to chronic pain with endometriosis?

Q What are some newer treatment approaches to chronic pain with endometriosis?

“Multidisciplinary approaches to endometriosis-related pain are important,” said Dr. Rapkin. “Although it is important to excise or cauterize endometriosis lesions, or debulk as much as can safely be removed during laparoscopic surgery, it is now standard of care that medical therapy, not surgery, is the first approach to treatment. Endometriosis is a chronic condition. Inflammatory factors will continue to proliferate in patients who menstruate and produce high levels of estrogen with ovulation. The goal of medical therapy is to decrease the levels of estrogen that contribute to maintenance and proliferation of the implants. We want to suppress estrogen in a way that is compatible with long-term quality of life for our patients. Wiping out estrogen and placing patients into a chemical or surgical menopause for most of their reproductive years is not desirable.”

Approaches to hormonally modulate endometriosis include combined hormonal contraceptives and progestin-only medications, such as the levonogestrol-containing IUD, progestin-containing contraceptive implants, injections, or tablets. Second-line medical therapy consists of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists that can be used for 6 months to 2 years and allows for further lowering of estrogen levels. These may not provide sufficient pain relief for some patients. “There is some evidence from Dr. Giamberadino’s studies that after women with dysmenorrhea were treated with oral contraceptives, the abdominal wall hyperalgesia decreased,” said Dr. Rapkin. “The question is, why don’t we see this in all patients? We come to the realization that endometriosis has to be treated as a neurologically mediated disorder. We have to treat the peripheral and central sensitization in a multidisciplinary way.”

A holistic approach to endometriosis is a new and exciting area for the field, said Dr. Rapkin. “We have to treat ‘bottom-up’, and ‘top-down.’ Bottom-up means we are addressing the peripheral factors that contribute to pain: endometriotic lesions, other pelvic organ pain, myofascial pain, trigger points, the tender points, and the muscle dysfunction in the abdominal wall, the back, and the pelvic floor. Pelvic floor physical therapists help women with pain and endometriosis. Often, women with endometriosis have myofascial pain and pain related to the other comorbid pain conditions they may have developed. Peripheral nerve blocks and medications used for neuropathic pain that alter nerve firing can be helpful in many situations. Pain can be augmented by cognitions and beliefs about pain, and by anxiety and depression. So the top-down approach addresses the cognitions, depression, and anxiety. We do not consider endometriosis a psychosomatic condition, but we know that if you do not address the central upregulation, including anxiety and depression, we may not get anywhere.”

“Interestingly, neurotransmitters and brain regions governing mood contribute to nerve pain. Medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants, and calcium channel blocking agents may prove fruitful. Cognitive behavioral therapy is another approach—to stimulate the prefrontal cortex, the area that is involved in pain inhibition, and other areas of the brain that may produce endogenous opioids to help with inhibiting pain. Bringing in complementary approaches is very important—for example, mindfulness-based meditation or yoga. There is growing evidence for acupuncture as well. Physical therapists, pain psychologists, anesthesiologists, or gynecologists who are facile with nerve blocks, to help tone down hyperalgesic tissues, in addition to medical and surgical therapy, have the possibility of really improving the lives of women with endometriosis.”

Q What key pearls would you like to share with readers?

“It is important to evaluate the entire individual,” she said. “Do not just viscerally focus on the uterus, the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the peritoneum; investigate the adjacent organs and somatic tissues. Think about the abdominal wall, think about the pelvic floor. Learn how to evaluate these structures. There are simple evaluation techniques that gynecologists can learn and should include with every patient with pelvic pain, whether or not they are suspected of having endometriosis. You also want to get a complete history to determine if there are other co-occurring pain conditions. If there are, it is already a sign that there may be central sensitization.”

“Very often, it is necessary to bring in a pain psychologist—not because the disease is psychosomatic but because therapy can help the patient to learn how to use their brain to erase pain memory, and of course to address the concomitant anxiety, depression, and social isolation that happens with pain.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Olive DL, Lindheim SR, Pritts EA. New medical treatments for endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):319-328.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447): 1789-1799.

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366-373.e8.

- Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1292–1299.

- Bruner-Tran KL, Mokshagundam S, Herington JL. Rodent models of experimental endometriosis: identifying mechanisms of disease and therapeutic targets. Curr Womens Health Rev. 2018;14(2):173-188.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2715-2724.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(2):164-185.

- Tirlapur SA, Kuhrt K, Chaliha C. The ‘evil twin syndrome’ in chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review of prevalence studies of bladder pain syndrome and endometriosis. Int J Surg. 2013;11(3):233-237.

- Coxon L, Horne AW, Vincent K. Pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated pain: a review of pelvic and central nervous system mechanisms. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Feb 15. pii: S1521-6934(18)30032-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.014. [Epub ahead of print]

- Yan D, Liu X, Guo SW. Nerve fibers and endometriotic lesions: partners in crime in inflicting pains in women with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:14-24.

- Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266-271.

- Fedele L, Parazzini F, Bianchi S. Stage and localization of pelvic endometriosis and pain. Fertil Steril. 1990;53(1):155-158.

- Berkley KJ, Rapkin AJ, Papka RE. The pains of endometriosis. Science. 2005;308(5728):1587-1589.

- Giamberardino MA, Tana C, Costantini R. Pain thresholds in women with chronic pelvic pain. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26(4):253-259.

- Giamberardino MA, Berkley KJ, Affaitati G. Influence of endometriosis on pain behaviors and muscle hyperalgesia induced by a ureteral calculosis in female rats. Pain. 2002;95(3):247-257.

- As-Sanie S, Kim J, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Functional connectivity is associated with altered brain chemistry in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(1):1-13.

- Olive DL, Lindheim SR, Pritts EA. New medical treatments for endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):319-328.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447): 1789-1799.

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366-373.e8.

- Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1292–1299.

- Bruner-Tran KL, Mokshagundam S, Herington JL. Rodent models of experimental endometriosis: identifying mechanisms of disease and therapeutic targets. Curr Womens Health Rev. 2018;14(2):173-188.

- Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(10):2715-2724.

- Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(2):164-185.

- Tirlapur SA, Kuhrt K, Chaliha C. The ‘evil twin syndrome’ in chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review of prevalence studies of bladder pain syndrome and endometriosis. Int J Surg. 2013;11(3):233-237.

- Coxon L, Horne AW, Vincent K. Pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated pain: a review of pelvic and central nervous system mechanisms. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Feb 15. pii: S1521-6934(18)30032-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.014. [Epub ahead of print]

- Yan D, Liu X, Guo SW. Nerve fibers and endometriotic lesions: partners in crime in inflicting pains in women with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:14-24.

- Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266-271.

- Fedele L, Parazzini F, Bianchi S. Stage and localization of pelvic endometriosis and pain. Fertil Steril. 1990;53(1):155-158.

- Berkley KJ, Rapkin AJ, Papka RE. The pains of endometriosis. Science. 2005;308(5728):1587-1589.

- Giamberardino MA, Tana C, Costantini R. Pain thresholds in women with chronic pelvic pain. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26(4):253-259.

- Giamberardino MA, Berkley KJ, Affaitati G. Influence of endometriosis on pain behaviors and muscle hyperalgesia induced by a ureteral calculosis in female rats. Pain. 2002;95(3):247-257.

- As-Sanie S, Kim J, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Functional connectivity is associated with altered brain chemistry in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(1):1-13.

Coding and reimbursement 101: How to maximize your payments

While reimbursement for ObGyn services seemingly should be a simple matter of putting codes on a claim form, the reality is that it is complex, and it requires a team approach to accomplish timely filing to receive fair and accurate reimbursement.

Reimbursement occurs over the length of the revenue cycle for a patient encounter and involves many steps. It starts when the patient makes an appointment for services and ends when the practice receives payment. Along the way, there must be good clinician documentation and sound knowledge about the billing process (including the Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes for services), the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes that establish medical necessity, the modifiers that alter the meaning of the codes, and, of course, the bundling issues that now accompany many coding situations.

In addition, ObGyn practices must contend with a multitude of payers—from federal to commercial—and must understand and adhere to each payer’s rules and policies to maximize and retain reimbursement.

In this article, I detail stumbling blocks to maximizing reimbursement and how to avoid them.

Coding considerations for office services

Good documentation before, during, and after a patient’s office visit is essential, along with accurate codes, modifiers, and order of services on the claims you submit.

Prep paperwork before the patient encounter

Once a patient makes an appointment, the front-end staff can handle some of the tasks in the cycle. This includes ensuring that the patient’s insurance coverage information is current, informing the patient of any additional information to bring at the time of the visit (such as a patient history form for a new patient visit or a list of current prescriptions), or, if an established patient will be having a procedure, making sure that prior authorization is complete. This streamlines the process, assists the clinician with documentation housekeeping, and ensures that incorrect or missing information does not cause a claim to be denied or not be filed in a timely manner (many payers require submission of an initial claim 30 days from the date of service).

Continue to: Document details of the clinician-patient interaction

Document details of the clinician-patient interaction

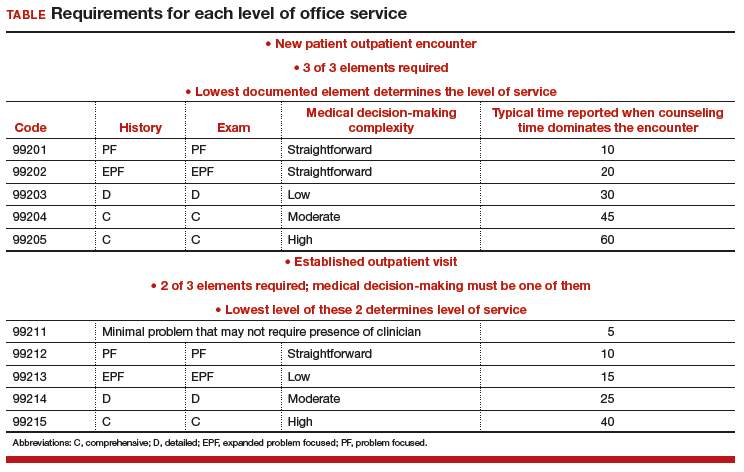

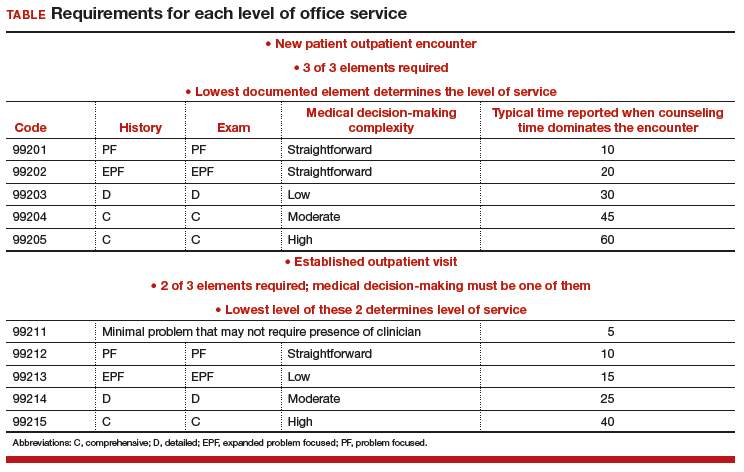

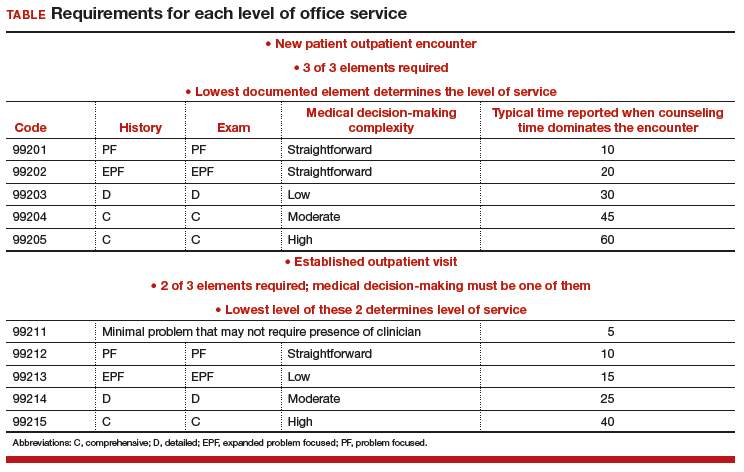

At the time of the encounter, you are responsible for documenting your contact with the patient in enough detail to support billing a CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code at the level selected and/or any procedures or other services performed. The TABLE provides an overview of the requirements for each level of office service.

If both an E/M and a procedure are performed on the same date of service, the E/M must be documented to show it was separate from the procedure and that the work was significantly more than would be required to accomplish the procedure. Documentation of the procedure should include the indication, steps performed, findings, the patient’s condition afterward, and instructions for aftercare or follow-up.

If you use an electronic health record for reporting, you may be the one responsible for selecting both the CPT code for services performed and an ICD-10-CM code(s) to establish the medical need for them. Select the most accurate CPT codes, and clearly link them to a supporting diagnosis for each service that will be billed. If more than one diagnosis is applicable, the first one linked to any given service should represent the most important justification, as not all payers will accept more than one diagnosis code on the claim per service billed.

If the billing staff is assigned the task of selecting the CPT and/or ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes based on your documentation, they should be well versed in the services, procedures, and diagnoses reported for their ObGyn practice.

The actual code selection may end up being a joint venture between the clinician and the staff to ensure that accurate information will be entered on the claim. Good and frequent clinician-staff communication on billing of services can transform average reimbursement into maximized reimbursement.

Be aware of bundles

Sometimes more than one service or procedure is listed on a claim on the same date of service. However, it is important to identify all potential bundles before billing to ensure correct payment. For instance, payers like to bundle an E/M service and a procedure, or you may be in the global period (defined below) of a surgery but need to report an unrelated service.

You and your staff must work together to ensure the claim is submitted with the correct modifiers; on the other hand, you may decide that a better method of coding is in order. Some payers, for example, will not reimburse both an insertion and a removal of an intrauterine device (IUD) on the same date of service. If that does happen, a modifier on the removal code might save the day, rather than billing 2 codes.

Continue to: Manage the modifiers

Manage the modifiers

Sometimes the code billed requires a modifier to ensure payment. Typical modifiers used in an ObGyn office setting include the following:

- 22, Increased procedural services (the clinician must assign a fee that is higher than the usual fee for the procedure and be able to document CPT equivalents to the work involved)

- 24, Unrelated E/M during the postoperative period (note that this modifier does not apply during the antepartum period for pregnancy)

- 25, Significant and separate E/M on the same date as another service or minor procedure

- 52, Reduced services (generally, the payer will expect an explanation of the reduced service and will determine payment accordingly)

- 57, Decision to perform major surgery the day of or the day before the surgery

- 59, Distinct procedural service (used when 2 procedures are bundled and a modifier is allowed). Note that payment reductions for multiple procedures will still apply.

- 79, Unrelated procedure during the postoperative period (usually paid at the full allowable).

Organize the order of services on the claim

For an outpatient claim that includes both an E/M service and procedures, the order of the services—not the order in which they were performed—may be important to obtaining maximum reimbursement. In general, payers will pay in full for a supported E/M service no matter where it appears on the claim, but they apply reductions only for multiple procedures.

For instance, if you insert levonorgestrel implants on the same date as you remove a large polyp from the cervix, you would want to report the code with the highest relative value unit (RVU) first. In this case, it would be 11981 (4.05 RVUs), 57500 (3.61 RVUs).

In the IUD case mentioned earlier (removal and insertion of IUDs on the same date), the order of the codes, assuming the payer reimburses for both, will be even more important since removal usually has a higher payment: 58301 (2.70 RUVs), 58300 (1.54 RVUs).

Coding considerations for surgical services

Surgical services performed in a hospital or ambulatory surgical center present another set of must-dos to ensure timely and fair reimbursement.

Grasp the ‘global package’ concept

Understanding this concept can be crucial to getting paid for additional services during this time period and correct billing for any E/M services performed prior to surgery. In general, the routine history and physical examination performed prior to a major surgery is considered included in the work and should not be billed separately. Surgical clearance for a patient’s condition, such as hypertension, a heart condition, or lung issues, can be billed separately, but these generally are performed by someone other than the operating surgeon.

Procedures performed in the hospital setting generally will have a 10- or 90-day global period. During this time, any related E/M service should not be billed separately, and the use of modifiers becomes even more important than with office services.

Applicable modifiers for use with hospital surgery can include all those for outpatient services plus:

- 50, Bilateral procedure (for which you may be paid up to 150% of the allowable)

- 58, Staged or related procedure during the postoperative period (this may be paid at the full allowable)

- 62, Co-surgeons (both surgeons bill the same CPT code and both document their involvement in the surgery). Medicare will reimburse each surgeon 62.5% of the allowable.

- 78, Return to the operating room for an unplanned related procedure (the full allowable may be reduced by some payers owing to their belief that this is soon after the original procedure so intraoperative time only is considered).

Be savvy about surgical bundles

Here, it is important to understand all published bundling edits for multiple procedures performed by the same surgeon at the same surgical session. If a code combination is never allowed but the surgery is more intense due to additional work required, a modifier -22 may be your only option. Again, clear, concise documentation of the additional work is imperative to receive the additional payment.

When a modifier is allowed, it generally will be one that denotes a procedure done on bilateral organs (such as the ovaries) when there is no extensive code to cover all of the work or when the additional procedure is “distinct” and meets the criteria for using a modifier 59.

Medicare has expanded the modifier -59 into additional modifiers to further explain the situation. These additional modifiers are:

- XE, A service that is distinct because it occurred during a separate encounter on the same date of service

- XS, A service that is distinct because it was performed on a separate organ/structure

- XP, A service that is distinct because it was performed by a different practitioner

- XU, The use of a service that is distinct because it does not overlap usual components of the main service.

Standards of care: Some steps are inherent to the surgery

Expect to receive claim denials if you bill separately for adhesiolysis during a surgical procedure. Every payer considers this procedure related to access to the surgical site and will deny separate coding. If the lysis was truly significant in terms of work, try reporting the modifier 22 and provide adequate documentation.

Other procedures at the time of surgery that generally are not paid for include 1) examination under anesthesia, 2) any procedure done to check the surgeon’s work (for example, cystoscopy, especially when done after urinary or pelvic reconstruction procedures, or chromotubation following extensive ovariolysis), 3) placement of catheters, and 4) placement of devices to alleviate postsurgical pain.

Bottom line

Maximizing reimbursement involves good documentation, correct CPT codes linked to specific and accurate medical indications, the use of appropriate modifiers, and listing codes in order of their relative values from highest to lowest.

Should a denial or unfair reduction in payment come your way, analyze the rejection to determine the cause and make billing and reporting changes as needed to improve your future reimbursements.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

While reimbursement for ObGyn services seemingly should be a simple matter of putting codes on a claim form, the reality is that it is complex, and it requires a team approach to accomplish timely filing to receive fair and accurate reimbursement.

Reimbursement occurs over the length of the revenue cycle for a patient encounter and involves many steps. It starts when the patient makes an appointment for services and ends when the practice receives payment. Along the way, there must be good clinician documentation and sound knowledge about the billing process (including the Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes for services), the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes that establish medical necessity, the modifiers that alter the meaning of the codes, and, of course, the bundling issues that now accompany many coding situations.

In addition, ObGyn practices must contend with a multitude of payers—from federal to commercial—and must understand and adhere to each payer’s rules and policies to maximize and retain reimbursement.

In this article, I detail stumbling blocks to maximizing reimbursement and how to avoid them.

Coding considerations for office services

Good documentation before, during, and after a patient’s office visit is essential, along with accurate codes, modifiers, and order of services on the claims you submit.

Prep paperwork before the patient encounter

Once a patient makes an appointment, the front-end staff can handle some of the tasks in the cycle. This includes ensuring that the patient’s insurance coverage information is current, informing the patient of any additional information to bring at the time of the visit (such as a patient history form for a new patient visit or a list of current prescriptions), or, if an established patient will be having a procedure, making sure that prior authorization is complete. This streamlines the process, assists the clinician with documentation housekeeping, and ensures that incorrect or missing information does not cause a claim to be denied or not be filed in a timely manner (many payers require submission of an initial claim 30 days from the date of service).

Continue to: Document details of the clinician-patient interaction

Document details of the clinician-patient interaction

At the time of the encounter, you are responsible for documenting your contact with the patient in enough detail to support billing a CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code at the level selected and/or any procedures or other services performed. The TABLE provides an overview of the requirements for each level of office service.

If both an E/M and a procedure are performed on the same date of service, the E/M must be documented to show it was separate from the procedure and that the work was significantly more than would be required to accomplish the procedure. Documentation of the procedure should include the indication, steps performed, findings, the patient’s condition afterward, and instructions for aftercare or follow-up.

If you use an electronic health record for reporting, you may be the one responsible for selecting both the CPT code for services performed and an ICD-10-CM code(s) to establish the medical need for them. Select the most accurate CPT codes, and clearly link them to a supporting diagnosis for each service that will be billed. If more than one diagnosis is applicable, the first one linked to any given service should represent the most important justification, as not all payers will accept more than one diagnosis code on the claim per service billed.

If the billing staff is assigned the task of selecting the CPT and/or ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes based on your documentation, they should be well versed in the services, procedures, and diagnoses reported for their ObGyn practice.

The actual code selection may end up being a joint venture between the clinician and the staff to ensure that accurate information will be entered on the claim. Good and frequent clinician-staff communication on billing of services can transform average reimbursement into maximized reimbursement.

Be aware of bundles

Sometimes more than one service or procedure is listed on a claim on the same date of service. However, it is important to identify all potential bundles before billing to ensure correct payment. For instance, payers like to bundle an E/M service and a procedure, or you may be in the global period (defined below) of a surgery but need to report an unrelated service.

You and your staff must work together to ensure the claim is submitted with the correct modifiers; on the other hand, you may decide that a better method of coding is in order. Some payers, for example, will not reimburse both an insertion and a removal of an intrauterine device (IUD) on the same date of service. If that does happen, a modifier on the removal code might save the day, rather than billing 2 codes.

Continue to: Manage the modifiers

Manage the modifiers

Sometimes the code billed requires a modifier to ensure payment. Typical modifiers used in an ObGyn office setting include the following:

- 22, Increased procedural services (the clinician must assign a fee that is higher than the usual fee for the procedure and be able to document CPT equivalents to the work involved)

- 24, Unrelated E/M during the postoperative period (note that this modifier does not apply during the antepartum period for pregnancy)

- 25, Significant and separate E/M on the same date as another service or minor procedure

- 52, Reduced services (generally, the payer will expect an explanation of the reduced service and will determine payment accordingly)

- 57, Decision to perform major surgery the day of or the day before the surgery

- 59, Distinct procedural service (used when 2 procedures are bundled and a modifier is allowed). Note that payment reductions for multiple procedures will still apply.

- 79, Unrelated procedure during the postoperative period (usually paid at the full allowable).

Organize the order of services on the claim

For an outpatient claim that includes both an E/M service and procedures, the order of the services—not the order in which they were performed—may be important to obtaining maximum reimbursement. In general, payers will pay in full for a supported E/M service no matter where it appears on the claim, but they apply reductions only for multiple procedures.

For instance, if you insert levonorgestrel implants on the same date as you remove a large polyp from the cervix, you would want to report the code with the highest relative value unit (RVU) first. In this case, it would be 11981 (4.05 RVUs), 57500 (3.61 RVUs).

In the IUD case mentioned earlier (removal and insertion of IUDs on the same date), the order of the codes, assuming the payer reimburses for both, will be even more important since removal usually has a higher payment: 58301 (2.70 RUVs), 58300 (1.54 RVUs).

Coding considerations for surgical services

Surgical services performed in a hospital or ambulatory surgical center present another set of must-dos to ensure timely and fair reimbursement.

Grasp the ‘global package’ concept

Understanding this concept can be crucial to getting paid for additional services during this time period and correct billing for any E/M services performed prior to surgery. In general, the routine history and physical examination performed prior to a major surgery is considered included in the work and should not be billed separately. Surgical clearance for a patient’s condition, such as hypertension, a heart condition, or lung issues, can be billed separately, but these generally are performed by someone other than the operating surgeon.

Procedures performed in the hospital setting generally will have a 10- or 90-day global period. During this time, any related E/M service should not be billed separately, and the use of modifiers becomes even more important than with office services.

Applicable modifiers for use with hospital surgery can include all those for outpatient services plus:

- 50, Bilateral procedure (for which you may be paid up to 150% of the allowable)

- 58, Staged or related procedure during the postoperative period (this may be paid at the full allowable)

- 62, Co-surgeons (both surgeons bill the same CPT code and both document their involvement in the surgery). Medicare will reimburse each surgeon 62.5% of the allowable.

- 78, Return to the operating room for an unplanned related procedure (the full allowable may be reduced by some payers owing to their belief that this is soon after the original procedure so intraoperative time only is considered).

Be savvy about surgical bundles

Here, it is important to understand all published bundling edits for multiple procedures performed by the same surgeon at the same surgical session. If a code combination is never allowed but the surgery is more intense due to additional work required, a modifier -22 may be your only option. Again, clear, concise documentation of the additional work is imperative to receive the additional payment.

When a modifier is allowed, it generally will be one that denotes a procedure done on bilateral organs (such as the ovaries) when there is no extensive code to cover all of the work or when the additional procedure is “distinct” and meets the criteria for using a modifier 59.

Medicare has expanded the modifier -59 into additional modifiers to further explain the situation. These additional modifiers are:

- XE, A service that is distinct because it occurred during a separate encounter on the same date of service

- XS, A service that is distinct because it was performed on a separate organ/structure

- XP, A service that is distinct because it was performed by a different practitioner

- XU, The use of a service that is distinct because it does not overlap usual components of the main service.

Standards of care: Some steps are inherent to the surgery

Expect to receive claim denials if you bill separately for adhesiolysis during a surgical procedure. Every payer considers this procedure related to access to the surgical site and will deny separate coding. If the lysis was truly significant in terms of work, try reporting the modifier 22 and provide adequate documentation.

Other procedures at the time of surgery that generally are not paid for include 1) examination under anesthesia, 2) any procedure done to check the surgeon’s work (for example, cystoscopy, especially when done after urinary or pelvic reconstruction procedures, or chromotubation following extensive ovariolysis), 3) placement of catheters, and 4) placement of devices to alleviate postsurgical pain.

Bottom line

Maximizing reimbursement involves good documentation, correct CPT codes linked to specific and accurate medical indications, the use of appropriate modifiers, and listing codes in order of their relative values from highest to lowest.

Should a denial or unfair reduction in payment come your way, analyze the rejection to determine the cause and make billing and reporting changes as needed to improve your future reimbursements.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

While reimbursement for ObGyn services seemingly should be a simple matter of putting codes on a claim form, the reality is that it is complex, and it requires a team approach to accomplish timely filing to receive fair and accurate reimbursement.

Reimbursement occurs over the length of the revenue cycle for a patient encounter and involves many steps. It starts when the patient makes an appointment for services and ends when the practice receives payment. Along the way, there must be good clinician documentation and sound knowledge about the billing process (including the Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes for services), the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes that establish medical necessity, the modifiers that alter the meaning of the codes, and, of course, the bundling issues that now accompany many coding situations.

In addition, ObGyn practices must contend with a multitude of payers—from federal to commercial—and must understand and adhere to each payer’s rules and policies to maximize and retain reimbursement.

In this article, I detail stumbling blocks to maximizing reimbursement and how to avoid them.

Coding considerations for office services

Good documentation before, during, and after a patient’s office visit is essential, along with accurate codes, modifiers, and order of services on the claims you submit.

Prep paperwork before the patient encounter

Once a patient makes an appointment, the front-end staff can handle some of the tasks in the cycle. This includes ensuring that the patient’s insurance coverage information is current, informing the patient of any additional information to bring at the time of the visit (such as a patient history form for a new patient visit or a list of current prescriptions), or, if an established patient will be having a procedure, making sure that prior authorization is complete. This streamlines the process, assists the clinician with documentation housekeeping, and ensures that incorrect or missing information does not cause a claim to be denied or not be filed in a timely manner (many payers require submission of an initial claim 30 days from the date of service).

Continue to: Document details of the clinician-patient interaction

Document details of the clinician-patient interaction

At the time of the encounter, you are responsible for documenting your contact with the patient in enough detail to support billing a CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code at the level selected and/or any procedures or other services performed. The TABLE provides an overview of the requirements for each level of office service.

If both an E/M and a procedure are performed on the same date of service, the E/M must be documented to show it was separate from the procedure and that the work was significantly more than would be required to accomplish the procedure. Documentation of the procedure should include the indication, steps performed, findings, the patient’s condition afterward, and instructions for aftercare or follow-up.

If you use an electronic health record for reporting, you may be the one responsible for selecting both the CPT code for services performed and an ICD-10-CM code(s) to establish the medical need for them. Select the most accurate CPT codes, and clearly link them to a supporting diagnosis for each service that will be billed. If more than one diagnosis is applicable, the first one linked to any given service should represent the most important justification, as not all payers will accept more than one diagnosis code on the claim per service billed.

If the billing staff is assigned the task of selecting the CPT and/or ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes based on your documentation, they should be well versed in the services, procedures, and diagnoses reported for their ObGyn practice.

The actual code selection may end up being a joint venture between the clinician and the staff to ensure that accurate information will be entered on the claim. Good and frequent clinician-staff communication on billing of services can transform average reimbursement into maximized reimbursement.

Be aware of bundles

Sometimes more than one service or procedure is listed on a claim on the same date of service. However, it is important to identify all potential bundles before billing to ensure correct payment. For instance, payers like to bundle an E/M service and a procedure, or you may be in the global period (defined below) of a surgery but need to report an unrelated service.

You and your staff must work together to ensure the claim is submitted with the correct modifiers; on the other hand, you may decide that a better method of coding is in order. Some payers, for example, will not reimburse both an insertion and a removal of an intrauterine device (IUD) on the same date of service. If that does happen, a modifier on the removal code might save the day, rather than billing 2 codes.

Continue to: Manage the modifiers

Manage the modifiers