User login

Increased risk for IBS among women with endometriosis

Key clinical point: Endometriosis is associated with a 3-fold increase in the risk for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with 1 in every 5 women with endometriosis having IBS.

Major finding: The odds of IBS were significantly higher in women with endometriosis compared with healthy controls (odds ratio 2.97; 95% CI 2.17-4.06), and the pooled prevalence of IBS among women with endometriosis was 23.4% (95% CI 9.7%-37.2%).

Study details: This study evaluated the prevalence of IBS in endometriosis (meta-analysis of 6 studies) and association between endometriosis and IBS (meta-analysis of 11 studies involving 18,887 patients with endometriosis and 77,171 healthy controls).

Disclosures: This study did not report any source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Nabi MY et al. Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:914356 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.914356

Key clinical point: Endometriosis is associated with a 3-fold increase in the risk for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with 1 in every 5 women with endometriosis having IBS.

Major finding: The odds of IBS were significantly higher in women with endometriosis compared with healthy controls (odds ratio 2.97; 95% CI 2.17-4.06), and the pooled prevalence of IBS among women with endometriosis was 23.4% (95% CI 9.7%-37.2%).

Study details: This study evaluated the prevalence of IBS in endometriosis (meta-analysis of 6 studies) and association between endometriosis and IBS (meta-analysis of 11 studies involving 18,887 patients with endometriosis and 77,171 healthy controls).

Disclosures: This study did not report any source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Nabi MY et al. Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:914356 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.914356

Key clinical point: Endometriosis is associated with a 3-fold increase in the risk for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with 1 in every 5 women with endometriosis having IBS.

Major finding: The odds of IBS were significantly higher in women with endometriosis compared with healthy controls (odds ratio 2.97; 95% CI 2.17-4.06), and the pooled prevalence of IBS among women with endometriosis was 23.4% (95% CI 9.7%-37.2%).

Study details: This study evaluated the prevalence of IBS in endometriosis (meta-analysis of 6 studies) and association between endometriosis and IBS (meta-analysis of 11 studies involving 18,887 patients with endometriosis and 77,171 healthy controls).

Disclosures: This study did not report any source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Nabi MY et al. Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:914356 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.914356

IBS symptoms affecting more than two-thirds of patients with IBD

Key clinical point: More than two-thirds of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were affected by irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-type symptoms, which were associated with worse depression, anxiety, somatoform symptoms, and quality-of-life scores.

Major finding: Overall, 67.2% of patients reported IBS-type symptoms at least once during the follow-up, with anxiety, depression, and somatoform symptom scores being worse in patients with vs without IBS-type symptoms (P < .001).

Study details: The data come from a 6-year longitudinal follow-up study including 760 individuals with well-characterized IBD.

Disclosures: This study was funded by The Leeds Teaching Hospitals Charitable Foundation and Tillotts Pharma U.K. Ltd. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fairbrass KM et al. Natural history and impact of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease during 6 years of longitudinal follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 (Aug 22). Doi: 10.1111/apt.17193

Key clinical point: More than two-thirds of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were affected by irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-type symptoms, which were associated with worse depression, anxiety, somatoform symptoms, and quality-of-life scores.

Major finding: Overall, 67.2% of patients reported IBS-type symptoms at least once during the follow-up, with anxiety, depression, and somatoform symptom scores being worse in patients with vs without IBS-type symptoms (P < .001).

Study details: The data come from a 6-year longitudinal follow-up study including 760 individuals with well-characterized IBD.

Disclosures: This study was funded by The Leeds Teaching Hospitals Charitable Foundation and Tillotts Pharma U.K. Ltd. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fairbrass KM et al. Natural history and impact of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease during 6 years of longitudinal follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 (Aug 22). Doi: 10.1111/apt.17193

Key clinical point: More than two-thirds of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were affected by irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-type symptoms, which were associated with worse depression, anxiety, somatoform symptoms, and quality-of-life scores.

Major finding: Overall, 67.2% of patients reported IBS-type symptoms at least once during the follow-up, with anxiety, depression, and somatoform symptom scores being worse in patients with vs without IBS-type symptoms (P < .001).

Study details: The data come from a 6-year longitudinal follow-up study including 760 individuals with well-characterized IBD.

Disclosures: This study was funded by The Leeds Teaching Hospitals Charitable Foundation and Tillotts Pharma U.K. Ltd. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fairbrass KM et al. Natural history and impact of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease during 6 years of longitudinal follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 (Aug 22). Doi: 10.1111/apt.17193

High degree of fatty liver and NAFLD tied to increased incident IBS risk

Key clinical point: The risk for incident irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was significantly higher in individuals in the highest vs lowest quartile of nonalcoholic fatty liver index and in those with a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Major finding: The risk of developing IBS was 21% higher among individuals in the highest vs lowest quartile of fatty liver index (hazard ratio [HR] 1.21; Ptrend < .001) and 13% higher among patients with vs without NAFLD (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.05-1.17).

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 396,838 participants from a large-scale prospective cohort who were free from IBS, any cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, alcoholic liver disease, and celiac disease, of which 38.6% had an NAFLD diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu S et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver is associated with increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):262 (Aug 22). Doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02460-8

Key clinical point: The risk for incident irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was significantly higher in individuals in the highest vs lowest quartile of nonalcoholic fatty liver index and in those with a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Major finding: The risk of developing IBS was 21% higher among individuals in the highest vs lowest quartile of fatty liver index (hazard ratio [HR] 1.21; Ptrend < .001) and 13% higher among patients with vs without NAFLD (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.05-1.17).

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 396,838 participants from a large-scale prospective cohort who were free from IBS, any cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, alcoholic liver disease, and celiac disease, of which 38.6% had an NAFLD diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu S et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver is associated with increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):262 (Aug 22). Doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02460-8

Key clinical point: The risk for incident irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was significantly higher in individuals in the highest vs lowest quartile of nonalcoholic fatty liver index and in those with a diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Major finding: The risk of developing IBS was 21% higher among individuals in the highest vs lowest quartile of fatty liver index (hazard ratio [HR] 1.21; Ptrend < .001) and 13% higher among patients with vs without NAFLD (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.05-1.17).

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 396,838 participants from a large-scale prospective cohort who were free from IBS, any cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, alcoholic liver disease, and celiac disease, of which 38.6% had an NAFLD diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wu S et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver is associated with increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):262 (Aug 22). Doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02460-8

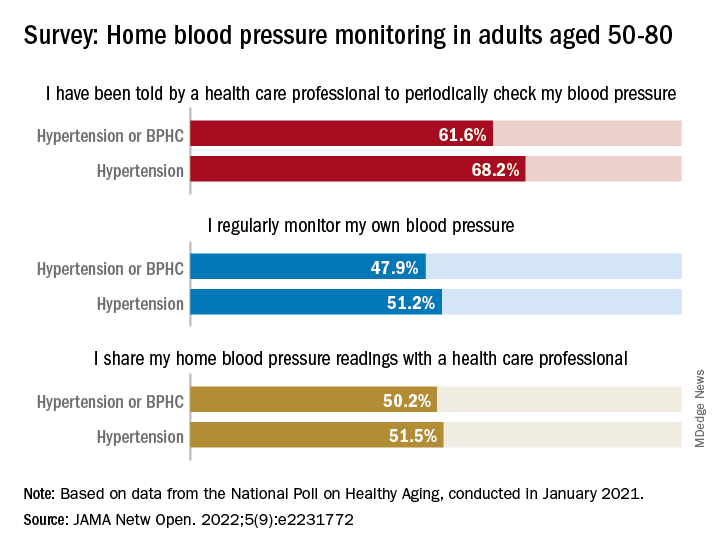

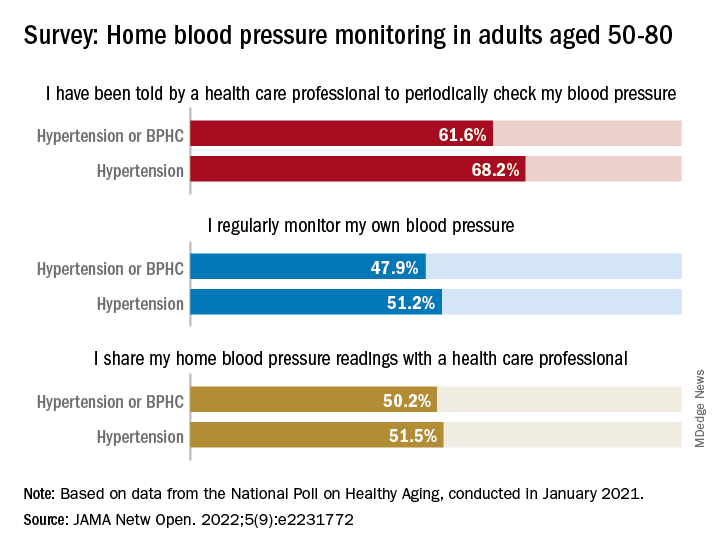

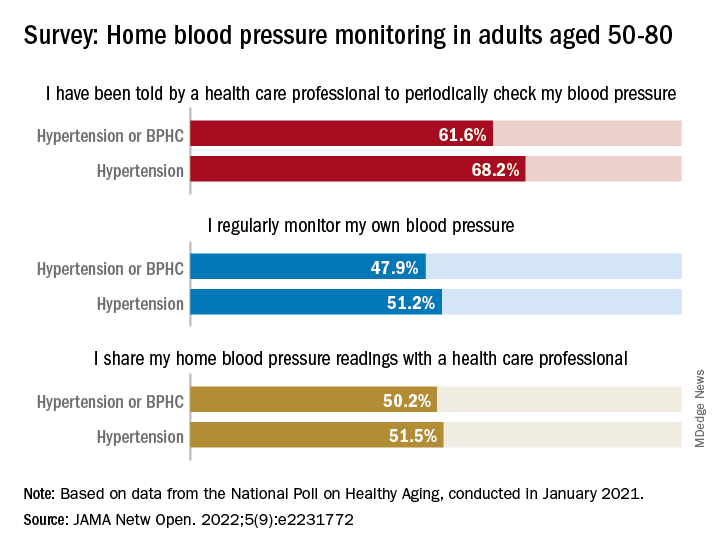

Home BP monitoring in older adults falls short of recommendations

Just over 51% of older hypertensive adults regularly check their own blood pressure, compared with 48% of those with blood pressure–related health conditions (BPHCs), based on a 2021 survey of individuals aged 50-80 years.

“Guidelines recommend that patients use self-measured blood pressure monitoring (SBPM) outside the clinic to diagnose and manage hypertension,” but just 61% of respondents with a BPHC and 68% of those with hypertension said that they had received such a recommendation from a physician, nurse, or other health care professional, Melanie V. Springer, MD, and associates said in JAMA Network Open.

The prevalence of regular monitoring among those with hypertension, 51.2%, does, however, compare favorably with an earlier study showing that 43% of adults aged 18 and older regularly monitored their BP in 2005 and 2008, “which is perhaps associated with our sample’s older age,” said Dr. Springer and associates of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The current study, they noted, is the first to report “SBPM prevalence in adults ages 50 to 80 years with hypertension or BPHCs, who have a higher risk of adverse outcomes from uncontrolled BP than younger adults.” The analysis is based on data from the National Poll on Healthy Aging, conducted by the University of Michigan in January 2021 and completed by 2,023 individuals.

The frequency of home monitoring varied among adults with BPHCs, as just under 15% reported daily checks and the largest proportion, about 28%, used their device one to three times per month. The results of home monitoring were shared with health care professionals by 50.2% of respondents with a BPHC and by 51.5% of those with hypertension, they said in the research letter.

Home monitoring’s less-than-universal recommendation by providers and use by patients “suggest that protocols should be developed to educate patients about the importance of SBPM and sharing readings with clinicians and the frequency that SBPM should be performed,” Dr. Springer and associates wrote.

The study was funded by AARP, Michigan Medicine, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. One investigator has received consulting fees or honoraria from SeeChange Health, HealthMine, the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AbilTo, Kansas City Area Life Sciences Institute, American Diabetes Association, Donaghue Foundation, and Luxembourg National Research Fund.

Just over 51% of older hypertensive adults regularly check their own blood pressure, compared with 48% of those with blood pressure–related health conditions (BPHCs), based on a 2021 survey of individuals aged 50-80 years.

“Guidelines recommend that patients use self-measured blood pressure monitoring (SBPM) outside the clinic to diagnose and manage hypertension,” but just 61% of respondents with a BPHC and 68% of those with hypertension said that they had received such a recommendation from a physician, nurse, or other health care professional, Melanie V. Springer, MD, and associates said in JAMA Network Open.

The prevalence of regular monitoring among those with hypertension, 51.2%, does, however, compare favorably with an earlier study showing that 43% of adults aged 18 and older regularly monitored their BP in 2005 and 2008, “which is perhaps associated with our sample’s older age,” said Dr. Springer and associates of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The current study, they noted, is the first to report “SBPM prevalence in adults ages 50 to 80 years with hypertension or BPHCs, who have a higher risk of adverse outcomes from uncontrolled BP than younger adults.” The analysis is based on data from the National Poll on Healthy Aging, conducted by the University of Michigan in January 2021 and completed by 2,023 individuals.

The frequency of home monitoring varied among adults with BPHCs, as just under 15% reported daily checks and the largest proportion, about 28%, used their device one to three times per month. The results of home monitoring were shared with health care professionals by 50.2% of respondents with a BPHC and by 51.5% of those with hypertension, they said in the research letter.

Home monitoring’s less-than-universal recommendation by providers and use by patients “suggest that protocols should be developed to educate patients about the importance of SBPM and sharing readings with clinicians and the frequency that SBPM should be performed,” Dr. Springer and associates wrote.

The study was funded by AARP, Michigan Medicine, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. One investigator has received consulting fees or honoraria from SeeChange Health, HealthMine, the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AbilTo, Kansas City Area Life Sciences Institute, American Diabetes Association, Donaghue Foundation, and Luxembourg National Research Fund.

Just over 51% of older hypertensive adults regularly check their own blood pressure, compared with 48% of those with blood pressure–related health conditions (BPHCs), based on a 2021 survey of individuals aged 50-80 years.

“Guidelines recommend that patients use self-measured blood pressure monitoring (SBPM) outside the clinic to diagnose and manage hypertension,” but just 61% of respondents with a BPHC and 68% of those with hypertension said that they had received such a recommendation from a physician, nurse, or other health care professional, Melanie V. Springer, MD, and associates said in JAMA Network Open.

The prevalence of regular monitoring among those with hypertension, 51.2%, does, however, compare favorably with an earlier study showing that 43% of adults aged 18 and older regularly monitored their BP in 2005 and 2008, “which is perhaps associated with our sample’s older age,” said Dr. Springer and associates of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The current study, they noted, is the first to report “SBPM prevalence in adults ages 50 to 80 years with hypertension or BPHCs, who have a higher risk of adverse outcomes from uncontrolled BP than younger adults.” The analysis is based on data from the National Poll on Healthy Aging, conducted by the University of Michigan in January 2021 and completed by 2,023 individuals.

The frequency of home monitoring varied among adults with BPHCs, as just under 15% reported daily checks and the largest proportion, about 28%, used their device one to three times per month. The results of home monitoring were shared with health care professionals by 50.2% of respondents with a BPHC and by 51.5% of those with hypertension, they said in the research letter.

Home monitoring’s less-than-universal recommendation by providers and use by patients “suggest that protocols should be developed to educate patients about the importance of SBPM and sharing readings with clinicians and the frequency that SBPM should be performed,” Dr. Springer and associates wrote.

The study was funded by AARP, Michigan Medicine, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. One investigator has received consulting fees or honoraria from SeeChange Health, HealthMine, the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, AbilTo, Kansas City Area Life Sciences Institute, American Diabetes Association, Donaghue Foundation, and Luxembourg National Research Fund.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Vibegron fails to improve IBS-symptoms in phase 2 trial

Key clinical point: Once-daily 75 mg vibegron was not associated with a clinically significant improvement in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-associated abdominal pain in women with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) or mixed diarrhea/constipation IBS (IBS-M).

Major finding: At week 12, the percentage of women with IBS-D (40.9% vs 42.9%; P = .8222) or IBS-M (28.9% vs 24.4%; P = .6151) experiencing ≥30% improvement in IBS-associated abdominal pain was not significantly different with vibegron vs placebo. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was comparable between the treatment groups.

Study details: The data come from a phase 2 randomized controlled trial including 222 adult women with IBS-D or IBS-M who were randomly assigned to receive 75 mg vibegron (n = 111) or placebo (n = 111).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Urovant Sciences. J King, D Shortino, C Schaumburg, and C Haag-Molkenteller declared being former employees of Urovant Sciences. Some authors declared receiving research grants or serving as consultants or on scientific advisory boards for various sources, including Urovant Sciences.

Source: Lacy BE et al. Efficacy and safety of vibegron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in women: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;e14448 (Aug 16). Doi: 10.1111/nmo.14448

Key clinical point: Once-daily 75 mg vibegron was not associated with a clinically significant improvement in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-associated abdominal pain in women with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) or mixed diarrhea/constipation IBS (IBS-M).

Major finding: At week 12, the percentage of women with IBS-D (40.9% vs 42.9%; P = .8222) or IBS-M (28.9% vs 24.4%; P = .6151) experiencing ≥30% improvement in IBS-associated abdominal pain was not significantly different with vibegron vs placebo. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was comparable between the treatment groups.

Study details: The data come from a phase 2 randomized controlled trial including 222 adult women with IBS-D or IBS-M who were randomly assigned to receive 75 mg vibegron (n = 111) or placebo (n = 111).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Urovant Sciences. J King, D Shortino, C Schaumburg, and C Haag-Molkenteller declared being former employees of Urovant Sciences. Some authors declared receiving research grants or serving as consultants or on scientific advisory boards for various sources, including Urovant Sciences.

Source: Lacy BE et al. Efficacy and safety of vibegron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in women: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;e14448 (Aug 16). Doi: 10.1111/nmo.14448

Key clinical point: Once-daily 75 mg vibegron was not associated with a clinically significant improvement in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-associated abdominal pain in women with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) or mixed diarrhea/constipation IBS (IBS-M).

Major finding: At week 12, the percentage of women with IBS-D (40.9% vs 42.9%; P = .8222) or IBS-M (28.9% vs 24.4%; P = .6151) experiencing ≥30% improvement in IBS-associated abdominal pain was not significantly different with vibegron vs placebo. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was comparable between the treatment groups.

Study details: The data come from a phase 2 randomized controlled trial including 222 adult women with IBS-D or IBS-M who were randomly assigned to receive 75 mg vibegron (n = 111) or placebo (n = 111).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Urovant Sciences. J King, D Shortino, C Schaumburg, and C Haag-Molkenteller declared being former employees of Urovant Sciences. Some authors declared receiving research grants or serving as consultants or on scientific advisory boards for various sources, including Urovant Sciences.

Source: Lacy BE et al. Efficacy and safety of vibegron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in women: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;e14448 (Aug 16). Doi: 10.1111/nmo.14448

Mesalazine not superior to placebo for global improvement of IBS symptoms

Key clinical point: An 8-week treatment with mesalazine offered no clear benefits over placebo for global improvement of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms.

Major finding: A similar proportion of patients receiving mesalazine vs placebo reported satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms during ≥50% of the treatment weeks (36% vs 30%; P = .40); however, the improvement in abdominal bloating was significantly greater in the mesalazine vs placebo group (P = .02).

Study details: The data come from a randomized controlled trial including 181 patients with IBS who were assigned to an 8-week treatment with 2400 mg mesalazine orally or placebo once daily.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eurostars project grant from Tillotts Pharma AB and by the Swedish state. Some authors declared receiving research grants or serving as consultants or on advisory boards for various sources, including Tillotts Pharma.

Source: Tejera VC et al. Randomised clinical trial and meta-analysis: Mesalazine treatment in irritable bowel syndrome—Effects on gastrointestinal symptoms and rectal biomarkers of immune activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(6):968-979 (Aug 8). Doi: 10.1111/apt.17182

Key clinical point: An 8-week treatment with mesalazine offered no clear benefits over placebo for global improvement of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms.

Major finding: A similar proportion of patients receiving mesalazine vs placebo reported satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms during ≥50% of the treatment weeks (36% vs 30%; P = .40); however, the improvement in abdominal bloating was significantly greater in the mesalazine vs placebo group (P = .02).

Study details: The data come from a randomized controlled trial including 181 patients with IBS who were assigned to an 8-week treatment with 2400 mg mesalazine orally or placebo once daily.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eurostars project grant from Tillotts Pharma AB and by the Swedish state. Some authors declared receiving research grants or serving as consultants or on advisory boards for various sources, including Tillotts Pharma.

Source: Tejera VC et al. Randomised clinical trial and meta-analysis: Mesalazine treatment in irritable bowel syndrome—Effects on gastrointestinal symptoms and rectal biomarkers of immune activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(6):968-979 (Aug 8). Doi: 10.1111/apt.17182

Key clinical point: An 8-week treatment with mesalazine offered no clear benefits over placebo for global improvement of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms.

Major finding: A similar proportion of patients receiving mesalazine vs placebo reported satisfactory relief of IBS symptoms during ≥50% of the treatment weeks (36% vs 30%; P = .40); however, the improvement in abdominal bloating was significantly greater in the mesalazine vs placebo group (P = .02).

Study details: The data come from a randomized controlled trial including 181 patients with IBS who were assigned to an 8-week treatment with 2400 mg mesalazine orally or placebo once daily.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eurostars project grant from Tillotts Pharma AB and by the Swedish state. Some authors declared receiving research grants or serving as consultants or on advisory boards for various sources, including Tillotts Pharma.

Source: Tejera VC et al. Randomised clinical trial and meta-analysis: Mesalazine treatment in irritable bowel syndrome—Effects on gastrointestinal symptoms and rectal biomarkers of immune activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(6):968-979 (Aug 8). Doi: 10.1111/apt.17182

Continuous cuffless monitoring may fuel lifestyle change to lower BP

Wearing a cuffless device on the wrist to continuously monitor blood pressure was associated with a significantly lower systolic BP at 6 months among hypertensive adults, real-world results from Europe show.

“We don’t know what they did to reduce their blood pressure,” Jay Shah, MD, Division of Cardiology, Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization.

“The idea is that because they were exposed to their data on a continual basis, that may have prompted them to do something that led to an improvement in their blood pressure, whether it be exercise more, go to their doctor, or change their medication,” said Dr. Shah, who is also chief medical officer for Aktiia.

Dr. Shah presented the study at the Hypertension Scientific Sessions, San Diego.

Empowering data

The study used the Aktiia 24/7 BP monitor; Atkiia funded the trial. The monitor passively and continually monitors BP values from photoplethysmography signals collected via optical sensors at the wrist.

After initial individualized calibration using a cuff-based reference, BP measurements are displayed on a smartphone app, allowing users to consistently monitor their own BP for long periods of time.

Aktiia received CE mark in Europe in January 2021 and is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Shah and colleagues analyzed systolic BP (SBP) trends among 838 real-world Aktiia users in Europe (age 57 ± 11 years; 14% women) who consistently used the monitor for 6 months.

Altogether, they had data on 375 (± 287) app interactions, 3,646 (± 1,417) cuffless readings per user, and 9 (± 7) cuff readings per user.

Traditional cuff SBP averages were calculated monthly and compared with the SBP average of the first month. A t-test analysis was used to detect the difference in SBP between the first and successive months.

On the basis of the mean SBP calculated over 6 months, 136 participants were hypertensive (SBP > 140 mm Hg) and the rest had SBP less than 140 mm Hg.

Hypertensive users saw a statistically significant reduction in SBP of –3.2 mm Hg (95% CI, –0.70 to –5.59; P < .02), beginning at 3 months of continual cuffless BP monitoring, which was sustained through 6 months.

Among users with SBP less than 140 mm Hg, the mean SBP remained unchanged.

“The magnitude of improvement might look modest, but even a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP correlates to a 10% decrease in cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Shah told this news organization.

He noted that “one of the major hurdles is that people may not be aware they have high blood pressure because they don’t feel it. And with a regular cuff, they’ll only see that number when they actually check their blood pressure, which is extremely rare, even for people who have hypertension.”

“Having the ability to show someone their continual blood pressure picture really empowers them to do something to make changes and to be aware, [as well as] to be a more active participant in their health,” Dr. Shah said.

He said that a good analogy is diabetes management, which has transitioned from single finger-stick glucose monitoring to continuous glucose monitoring that provides a complete 24/7 picture of glucose levels.

Transforming technology

Offering perspective on the study, Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, with Yale New Haven Hospital and Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said that having an accurate, affordable, unobtrusive cuffless continuous BP monitor would “transform” BP management.

“This could unlock an era of precision BP management with empowerment of patients to view and act on their numbers,” Dr. Krumholz said in an interview.

“We need data to be confident in the devices – and then research to best leverage the streams of information – and strategies to optimize its use in practice,” Dr. Krumholz added.

“Like any new innovation, we need to mitigate risks and monitor for unintended adverse consequences, but I am bullish on the future of cuffless continuous BP monitors,” Dr. Krumholz said.

Dr. Krumholz said that he “applauds Aktiia for doing studies that assess the effect of the information they are producing on BP over time. We need to know that new approaches not only generate valid information but that they can improve health.”

Ready for prime time?

In June, the European Society of Hypertension issued a statement noting that cuffless BP measurement is a fast-growing and promising field with considerable potential for improving hypertension awareness, management, and control, but because the accuracy of these new devices has not yet been validated, they are not yet suitable for clinical use.

Also providing perspective, Stephen Juraschek, MD, PhD, research director, Hypertension Center of Excellence at Healthcare Associates, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said that “there is a lot of interest in cuffless BP monitors due to their ease of measurement, comfort, and ability to obtain BP measurements in multiple settings and environments, and this study showed that the monitoring improved BP over time.”

“It is believed that the increased awareness and feedback may promote healthier behaviors aimed at lowering BP. However, this result should not be conflated with the accuracy of these monitors,” Dr. Juraschek cautioned.

He also noted that there is still no formally approved validation protocol by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.

“While a number of cuffless devices are cleared by the FDA through its 510k mechanism (that is, demonstration of device equivalence), there is no formal stamp of approval or attestation that the measurements are accurate,” Dr. Juraschek said in an interview.

In his view, “more work is needed to understand the validity of these devices. For now, validated, cuff-based home devices are recommended for BP measurement at home, while further work is done to determine the accuracy of these cuffless technologies.”

The study was funded by Aktiia. Dr. Shah is an employee of the company. Dr. Krumholz has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Juraschek is a member of the Validate BP review committee and the AAMI sphygmomanometer committee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Wearing a cuffless device on the wrist to continuously monitor blood pressure was associated with a significantly lower systolic BP at 6 months among hypertensive adults, real-world results from Europe show.

“We don’t know what they did to reduce their blood pressure,” Jay Shah, MD, Division of Cardiology, Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization.

“The idea is that because they were exposed to their data on a continual basis, that may have prompted them to do something that led to an improvement in their blood pressure, whether it be exercise more, go to their doctor, or change their medication,” said Dr. Shah, who is also chief medical officer for Aktiia.

Dr. Shah presented the study at the Hypertension Scientific Sessions, San Diego.

Empowering data

The study used the Aktiia 24/7 BP monitor; Atkiia funded the trial. The monitor passively and continually monitors BP values from photoplethysmography signals collected via optical sensors at the wrist.

After initial individualized calibration using a cuff-based reference, BP measurements are displayed on a smartphone app, allowing users to consistently monitor their own BP for long periods of time.

Aktiia received CE mark in Europe in January 2021 and is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Shah and colleagues analyzed systolic BP (SBP) trends among 838 real-world Aktiia users in Europe (age 57 ± 11 years; 14% women) who consistently used the monitor for 6 months.

Altogether, they had data on 375 (± 287) app interactions, 3,646 (± 1,417) cuffless readings per user, and 9 (± 7) cuff readings per user.

Traditional cuff SBP averages were calculated monthly and compared with the SBP average of the first month. A t-test analysis was used to detect the difference in SBP between the first and successive months.

On the basis of the mean SBP calculated over 6 months, 136 participants were hypertensive (SBP > 140 mm Hg) and the rest had SBP less than 140 mm Hg.

Hypertensive users saw a statistically significant reduction in SBP of –3.2 mm Hg (95% CI, –0.70 to –5.59; P < .02), beginning at 3 months of continual cuffless BP monitoring, which was sustained through 6 months.

Among users with SBP less than 140 mm Hg, the mean SBP remained unchanged.

“The magnitude of improvement might look modest, but even a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP correlates to a 10% decrease in cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Shah told this news organization.

He noted that “one of the major hurdles is that people may not be aware they have high blood pressure because they don’t feel it. And with a regular cuff, they’ll only see that number when they actually check their blood pressure, which is extremely rare, even for people who have hypertension.”

“Having the ability to show someone their continual blood pressure picture really empowers them to do something to make changes and to be aware, [as well as] to be a more active participant in their health,” Dr. Shah said.

He said that a good analogy is diabetes management, which has transitioned from single finger-stick glucose monitoring to continuous glucose monitoring that provides a complete 24/7 picture of glucose levels.

Transforming technology

Offering perspective on the study, Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, with Yale New Haven Hospital and Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said that having an accurate, affordable, unobtrusive cuffless continuous BP monitor would “transform” BP management.

“This could unlock an era of precision BP management with empowerment of patients to view and act on their numbers,” Dr. Krumholz said in an interview.

“We need data to be confident in the devices – and then research to best leverage the streams of information – and strategies to optimize its use in practice,” Dr. Krumholz added.

“Like any new innovation, we need to mitigate risks and monitor for unintended adverse consequences, but I am bullish on the future of cuffless continuous BP monitors,” Dr. Krumholz said.

Dr. Krumholz said that he “applauds Aktiia for doing studies that assess the effect of the information they are producing on BP over time. We need to know that new approaches not only generate valid information but that they can improve health.”

Ready for prime time?

In June, the European Society of Hypertension issued a statement noting that cuffless BP measurement is a fast-growing and promising field with considerable potential for improving hypertension awareness, management, and control, but because the accuracy of these new devices has not yet been validated, they are not yet suitable for clinical use.

Also providing perspective, Stephen Juraschek, MD, PhD, research director, Hypertension Center of Excellence at Healthcare Associates, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said that “there is a lot of interest in cuffless BP monitors due to their ease of measurement, comfort, and ability to obtain BP measurements in multiple settings and environments, and this study showed that the monitoring improved BP over time.”

“It is believed that the increased awareness and feedback may promote healthier behaviors aimed at lowering BP. However, this result should not be conflated with the accuracy of these monitors,” Dr. Juraschek cautioned.

He also noted that there is still no formally approved validation protocol by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.

“While a number of cuffless devices are cleared by the FDA through its 510k mechanism (that is, demonstration of device equivalence), there is no formal stamp of approval or attestation that the measurements are accurate,” Dr. Juraschek said in an interview.

In his view, “more work is needed to understand the validity of these devices. For now, validated, cuff-based home devices are recommended for BP measurement at home, while further work is done to determine the accuracy of these cuffless technologies.”

The study was funded by Aktiia. Dr. Shah is an employee of the company. Dr. Krumholz has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Juraschek is a member of the Validate BP review committee and the AAMI sphygmomanometer committee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Wearing a cuffless device on the wrist to continuously monitor blood pressure was associated with a significantly lower systolic BP at 6 months among hypertensive adults, real-world results from Europe show.

“We don’t know what they did to reduce their blood pressure,” Jay Shah, MD, Division of Cardiology, Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization.

“The idea is that because they were exposed to their data on a continual basis, that may have prompted them to do something that led to an improvement in their blood pressure, whether it be exercise more, go to their doctor, or change their medication,” said Dr. Shah, who is also chief medical officer for Aktiia.

Dr. Shah presented the study at the Hypertension Scientific Sessions, San Diego.

Empowering data

The study used the Aktiia 24/7 BP monitor; Atkiia funded the trial. The monitor passively and continually monitors BP values from photoplethysmography signals collected via optical sensors at the wrist.

After initial individualized calibration using a cuff-based reference, BP measurements are displayed on a smartphone app, allowing users to consistently monitor their own BP for long periods of time.

Aktiia received CE mark in Europe in January 2021 and is currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Shah and colleagues analyzed systolic BP (SBP) trends among 838 real-world Aktiia users in Europe (age 57 ± 11 years; 14% women) who consistently used the monitor for 6 months.

Altogether, they had data on 375 (± 287) app interactions, 3,646 (± 1,417) cuffless readings per user, and 9 (± 7) cuff readings per user.

Traditional cuff SBP averages were calculated monthly and compared with the SBP average of the first month. A t-test analysis was used to detect the difference in SBP between the first and successive months.

On the basis of the mean SBP calculated over 6 months, 136 participants were hypertensive (SBP > 140 mm Hg) and the rest had SBP less than 140 mm Hg.

Hypertensive users saw a statistically significant reduction in SBP of –3.2 mm Hg (95% CI, –0.70 to –5.59; P < .02), beginning at 3 months of continual cuffless BP monitoring, which was sustained through 6 months.

Among users with SBP less than 140 mm Hg, the mean SBP remained unchanged.

“The magnitude of improvement might look modest, but even a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP correlates to a 10% decrease in cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Shah told this news organization.

He noted that “one of the major hurdles is that people may not be aware they have high blood pressure because they don’t feel it. And with a regular cuff, they’ll only see that number when they actually check their blood pressure, which is extremely rare, even for people who have hypertension.”

“Having the ability to show someone their continual blood pressure picture really empowers them to do something to make changes and to be aware, [as well as] to be a more active participant in their health,” Dr. Shah said.

He said that a good analogy is diabetes management, which has transitioned from single finger-stick glucose monitoring to continuous glucose monitoring that provides a complete 24/7 picture of glucose levels.

Transforming technology

Offering perspective on the study, Harlan Krumholz, MD, SM, with Yale New Haven Hospital and Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said that having an accurate, affordable, unobtrusive cuffless continuous BP monitor would “transform” BP management.

“This could unlock an era of precision BP management with empowerment of patients to view and act on their numbers,” Dr. Krumholz said in an interview.

“We need data to be confident in the devices – and then research to best leverage the streams of information – and strategies to optimize its use in practice,” Dr. Krumholz added.

“Like any new innovation, we need to mitigate risks and monitor for unintended adverse consequences, but I am bullish on the future of cuffless continuous BP monitors,” Dr. Krumholz said.

Dr. Krumholz said that he “applauds Aktiia for doing studies that assess the effect of the information they are producing on BP over time. We need to know that new approaches not only generate valid information but that they can improve health.”

Ready for prime time?

In June, the European Society of Hypertension issued a statement noting that cuffless BP measurement is a fast-growing and promising field with considerable potential for improving hypertension awareness, management, and control, but because the accuracy of these new devices has not yet been validated, they are not yet suitable for clinical use.

Also providing perspective, Stephen Juraschek, MD, PhD, research director, Hypertension Center of Excellence at Healthcare Associates, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said that “there is a lot of interest in cuffless BP monitors due to their ease of measurement, comfort, and ability to obtain BP measurements in multiple settings and environments, and this study showed that the monitoring improved BP over time.”

“It is believed that the increased awareness and feedback may promote healthier behaviors aimed at lowering BP. However, this result should not be conflated with the accuracy of these monitors,” Dr. Juraschek cautioned.

He also noted that there is still no formally approved validation protocol by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.

“While a number of cuffless devices are cleared by the FDA through its 510k mechanism (that is, demonstration of device equivalence), there is no formal stamp of approval or attestation that the measurements are accurate,” Dr. Juraschek said in an interview.

In his view, “more work is needed to understand the validity of these devices. For now, validated, cuff-based home devices are recommended for BP measurement at home, while further work is done to determine the accuracy of these cuffless technologies.”

The study was funded by Aktiia. Dr. Shah is an employee of the company. Dr. Krumholz has no relevant disclosures. Dr. Juraschek is a member of the Validate BP review committee and the AAMI sphygmomanometer committee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA HYPERTENSION 2022

House passes prior authorization bill, Senate path unclear

The path through the U.S. Senate is not yet certain for a bill intended to speed the prior authorization process of insurer-run Medicare Advantage plans, despite the measure having breezed through the House.

House leaders opted to move the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021 (HR 3173) without requiring a roll-call vote. The measure was passed on Sept. 14 by a voice vote, an approach used in general with only uncontroversial measures that have broad support. The bill has 191 Democratic and 135 Republican sponsors, representing about three-quarters of the members of the House.

“There is no reason that patients should be waiting for medically appropriate care, especially when we know that this can lead to worse outcomes,” Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) said in a Sept. 14 speech on the House floor. “The fundamental promise of Medicare Advantage is undermined when people are delaying care, getting sicker, and ultimately costing Medicare more money.”

Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-N.C.), spoke on the House floor that day as well, bringing up cases he has seen in his own urology practice in which prior authorization delays disrupted medical care. One patient wound up in the hospital with abscess after an insurer denied an antibiotic prescription, Rep. Murphy said.

But the Senate appears unlikely at this time to move the prior authorization bill as a standalone measure. Instead, the bill may become part of a larger legislative package focused on health care that the Senate Finance Committee intends to prepare later this year.

The House-passed bill would require insurer-run Medicare plans to respond to expedited requests for prior authorization of services within 24 hours and to other requests within 7 days. This bill also would establish an electronic program for prior authorizations and mandate increased transparency as to how insurers use this tool.

CBO: Cost of change would be billions

In seeking to mandate changes in prior authorization, lawmakers likely will need to contend with the issue of a $16 billion cumulative cost estimate for the bill from the Congressional Budget Office. Members of Congress often seek to offset new spending by pairing bills that add to expected costs for the federal government with ones expected to produce savings.

Unlike Rep. Blumenauer, Rep. Murphy, and other backers of the prior authorization streamlining bill, CBO staff estimates that making the mandated changes would raise federal spending, inasmuch as there would be “a greater use of services.”

On Sept. 14, CBO issued a one-page report on the costs of the bill. The CBO report concerns only the bill in question, as is common practice with the office’s estimates.

Prior authorization changes would begin in fiscal 2025 and would add $899 million in spending, or outlays, that year, CBO said. The annual costs from the streamlined prior authorization practices through fiscal 2026 to 2032 range from $1.6 billion to $2.7 billion.

Looking at the CBO estimate against a backdrop of total Medicare Advantage costs, though, may provide important context.

The increases in spending estimated by CBO may suggest that there would be little change in federal spending as a result of streamlining prior authorization practices. These estimates of increased annual spending of $1.6 billion–$2.7 billion are only a small fraction of the current annual cost of insurer-run Medicare, and they represent an even smaller share of the projected expense.

The federal government last year spent about $350 billion on insurer-run plans, excluding Part D drug plan payments, according to the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission (MedPAC).

As of 2021, about 27 million people were enrolled in these plans, accounting for about 46% of the total Medicare population. Enrollment has doubled since 2010, MedPAC said, and it is expected to continue to grow. By 2027, insurer-run Medicare could cover 50% of the program’s population, a figure that may reach 53% by 2031.

Federal payments to these plans will accelerate in the years ahead as insurers attract more people eligible for Medicare as customers. Payments to these private health plans could rise from an expected $418 billion this year to $940.6 billion by 2031, according to the most recent Medicare trustees report.

Good intentions, poor implementation?

Insurer-run Medicare has long enjoyed deep bipartisan support in Congress. That’s due in part to its potential for reducing spending on what are considered low-value treatments, or ones considered unlikely to provide a significant medical benefit, but Rep. Blumenauer is among the members of Congress who see insurer-run Medicare as a path for preserving the giant federal health program. Traditional Medicare has far fewer restrictions on services, which sometimes opens a path for tests and treatments that offer less value for patients.

“I believe that the way traditional fee-for-service Medicare operates is not sustainable and that Medicare Advantage is one of the tools we can use to demonstrate how we can incentivize value,” Rep. Blumenauer said on the House floor. “But this is only possible when the program operates as intended. I have been deeply concerned about the reports of delays in care” caused by the clunky prior authorization processes.

He highlighted a recent report from the internal watchdog group for the Department of Health & Human Services that raises concerns about denials of appropriate care. About 18% of a set of payment denials examined by the Office of Inspector General of HHS in April actually met Medicare coverage rules and plan billing rules.

“For patients and their families, being told that you need to wait longer for care that your doctor tells you that you need is incredibly frustrating and frightening,” Rep. Blumenauer said. “There’s no comfort to be found in the fact that your insurance company needs time to decide if your doctor is right.”

Trends in prior authorization

The CBO report does not provide detail on what kind of medical spending would increase under a streamlined prior authorization process in insurer-run Medicare plans.

From trends reported in prior authorization, though, two factors could be at play in what appear to be relatively small estimated increases in Medicare spending from streamlined prior authorization.

One is the work already underway to create less burdensome electronic systems for these requests, such as the Fast Prior Authorization Technology Highway initiative run by the trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The other factor could be the number of cases in which prior authorization merely causes delays in treatments and tests and thus simply postpones spending while adding to clinicians’ administrative work.

An analysis of prior authorization requests for dermatologic practices affiliated with the University of Utah may represent an extreme example. In a report published in JAMA Dermatology in 2020, researchers described what happened with requests made during 1 month, September 2016.

The approval rate for procedures was 99.6% – 100% (95 of 95) for Mohs surgery, and 96% (130 of 131, with 4 additional cases pending) for excisions. These findings supported calls for simplifying prior authorization procedures, “perhaps first by eliminating unnecessary PAs [prior authorizations] and appeals,” Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and coauthors wrote in the article.

Still, there is some evidence that insurer-run Medicare policies reduce the use of low-value care.

In a study published in JAMA Health Forum, Emily Boudreau, PhD, of insurer Humana Inc, and coauthors from Tufts University, Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia investigated whether insurer-run Medicare could do a better job in reducing the amount of low-value care delivered than the traditional program. They analyzed a set of claims data from 2017 to 2019 for people enrolled in insurer-run and traditional Medicare.

They reported a rate of 23.07 low-value services provided per 100 people in insurer-run Medicare, compared with 25.39 for those in traditional Medicare. Some of the biggest differences reported in the article were in cancer screenings for older people.

As an example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women older than 65 years not be screened for cervical cancer if they have undergone adequate screening in the past and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. There was an annual count of 1.76 screenings for cervical cancer per 100 women older than 65 in the insurer-run Medicare group versus 3.18 for those in traditional Medicare.

The Better Medicare Alliance issued a statement in favor of the House passage of the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act.

In it, the group said the measure would “modernize prior authorization while protecting its essential function in facilitating safe, high-value, evidence-based care.” The alliance promotes use of insurer-run Medicare. The board of the Better Medicare Alliance includes executives who serve with firms that run Advantage plans as well as medical organizations and universities.

“With studies showing that up to one-quarter of all health care expenditures are wasted on services with no benefit to the patient, we need a robust, next-generation prior authorization program to deter low-value, and even harmful, care while protecting access to needed treatment and effective therapies,” said A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Value-Based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor, in a statement issued by the Better Medicare Alliance. He is a member of the group’s council of scholars.

On the House floor on September 14, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), said he has heard from former colleagues and his medical school classmates that they now spend as much as 40% of their time on administrative work. These distractions from patient care are helping drive physicians away from the practice of medicine.

Still, the internist defended the basic premise of prior authorization while strongly appealing for better systems of handling it.

“Yes, there is a role for prior authorization in limited cases. There is also a role to go back and retrospectively look at how care is being delivered,” Rep. Bera said. “But what is happening today is a travesty. It wasn’t the intention of prior authorization. It is a prior authorization process gone awry.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The path through the U.S. Senate is not yet certain for a bill intended to speed the prior authorization process of insurer-run Medicare Advantage plans, despite the measure having breezed through the House.

House leaders opted to move the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021 (HR 3173) without requiring a roll-call vote. The measure was passed on Sept. 14 by a voice vote, an approach used in general with only uncontroversial measures that have broad support. The bill has 191 Democratic and 135 Republican sponsors, representing about three-quarters of the members of the House.

“There is no reason that patients should be waiting for medically appropriate care, especially when we know that this can lead to worse outcomes,” Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) said in a Sept. 14 speech on the House floor. “The fundamental promise of Medicare Advantage is undermined when people are delaying care, getting sicker, and ultimately costing Medicare more money.”

Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-N.C.), spoke on the House floor that day as well, bringing up cases he has seen in his own urology practice in which prior authorization delays disrupted medical care. One patient wound up in the hospital with abscess after an insurer denied an antibiotic prescription, Rep. Murphy said.

But the Senate appears unlikely at this time to move the prior authorization bill as a standalone measure. Instead, the bill may become part of a larger legislative package focused on health care that the Senate Finance Committee intends to prepare later this year.

The House-passed bill would require insurer-run Medicare plans to respond to expedited requests for prior authorization of services within 24 hours and to other requests within 7 days. This bill also would establish an electronic program for prior authorizations and mandate increased transparency as to how insurers use this tool.

CBO: Cost of change would be billions

In seeking to mandate changes in prior authorization, lawmakers likely will need to contend with the issue of a $16 billion cumulative cost estimate for the bill from the Congressional Budget Office. Members of Congress often seek to offset new spending by pairing bills that add to expected costs for the federal government with ones expected to produce savings.

Unlike Rep. Blumenauer, Rep. Murphy, and other backers of the prior authorization streamlining bill, CBO staff estimates that making the mandated changes would raise federal spending, inasmuch as there would be “a greater use of services.”

On Sept. 14, CBO issued a one-page report on the costs of the bill. The CBO report concerns only the bill in question, as is common practice with the office’s estimates.

Prior authorization changes would begin in fiscal 2025 and would add $899 million in spending, or outlays, that year, CBO said. The annual costs from the streamlined prior authorization practices through fiscal 2026 to 2032 range from $1.6 billion to $2.7 billion.

Looking at the CBO estimate against a backdrop of total Medicare Advantage costs, though, may provide important context.

The increases in spending estimated by CBO may suggest that there would be little change in federal spending as a result of streamlining prior authorization practices. These estimates of increased annual spending of $1.6 billion–$2.7 billion are only a small fraction of the current annual cost of insurer-run Medicare, and they represent an even smaller share of the projected expense.

The federal government last year spent about $350 billion on insurer-run plans, excluding Part D drug plan payments, according to the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission (MedPAC).

As of 2021, about 27 million people were enrolled in these plans, accounting for about 46% of the total Medicare population. Enrollment has doubled since 2010, MedPAC said, and it is expected to continue to grow. By 2027, insurer-run Medicare could cover 50% of the program’s population, a figure that may reach 53% by 2031.

Federal payments to these plans will accelerate in the years ahead as insurers attract more people eligible for Medicare as customers. Payments to these private health plans could rise from an expected $418 billion this year to $940.6 billion by 2031, according to the most recent Medicare trustees report.

Good intentions, poor implementation?

Insurer-run Medicare has long enjoyed deep bipartisan support in Congress. That’s due in part to its potential for reducing spending on what are considered low-value treatments, or ones considered unlikely to provide a significant medical benefit, but Rep. Blumenauer is among the members of Congress who see insurer-run Medicare as a path for preserving the giant federal health program. Traditional Medicare has far fewer restrictions on services, which sometimes opens a path for tests and treatments that offer less value for patients.

“I believe that the way traditional fee-for-service Medicare operates is not sustainable and that Medicare Advantage is one of the tools we can use to demonstrate how we can incentivize value,” Rep. Blumenauer said on the House floor. “But this is only possible when the program operates as intended. I have been deeply concerned about the reports of delays in care” caused by the clunky prior authorization processes.

He highlighted a recent report from the internal watchdog group for the Department of Health & Human Services that raises concerns about denials of appropriate care. About 18% of a set of payment denials examined by the Office of Inspector General of HHS in April actually met Medicare coverage rules and plan billing rules.

“For patients and their families, being told that you need to wait longer for care that your doctor tells you that you need is incredibly frustrating and frightening,” Rep. Blumenauer said. “There’s no comfort to be found in the fact that your insurance company needs time to decide if your doctor is right.”

Trends in prior authorization

The CBO report does not provide detail on what kind of medical spending would increase under a streamlined prior authorization process in insurer-run Medicare plans.

From trends reported in prior authorization, though, two factors could be at play in what appear to be relatively small estimated increases in Medicare spending from streamlined prior authorization.

One is the work already underway to create less burdensome electronic systems for these requests, such as the Fast Prior Authorization Technology Highway initiative run by the trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The other factor could be the number of cases in which prior authorization merely causes delays in treatments and tests and thus simply postpones spending while adding to clinicians’ administrative work.

An analysis of prior authorization requests for dermatologic practices affiliated with the University of Utah may represent an extreme example. In a report published in JAMA Dermatology in 2020, researchers described what happened with requests made during 1 month, September 2016.

The approval rate for procedures was 99.6% – 100% (95 of 95) for Mohs surgery, and 96% (130 of 131, with 4 additional cases pending) for excisions. These findings supported calls for simplifying prior authorization procedures, “perhaps first by eliminating unnecessary PAs [prior authorizations] and appeals,” Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and coauthors wrote in the article.

Still, there is some evidence that insurer-run Medicare policies reduce the use of low-value care.

In a study published in JAMA Health Forum, Emily Boudreau, PhD, of insurer Humana Inc, and coauthors from Tufts University, Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia investigated whether insurer-run Medicare could do a better job in reducing the amount of low-value care delivered than the traditional program. They analyzed a set of claims data from 2017 to 2019 for people enrolled in insurer-run and traditional Medicare.

They reported a rate of 23.07 low-value services provided per 100 people in insurer-run Medicare, compared with 25.39 for those in traditional Medicare. Some of the biggest differences reported in the article were in cancer screenings for older people.

As an example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women older than 65 years not be screened for cervical cancer if they have undergone adequate screening in the past and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. There was an annual count of 1.76 screenings for cervical cancer per 100 women older than 65 in the insurer-run Medicare group versus 3.18 for those in traditional Medicare.

The Better Medicare Alliance issued a statement in favor of the House passage of the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act.

In it, the group said the measure would “modernize prior authorization while protecting its essential function in facilitating safe, high-value, evidence-based care.” The alliance promotes use of insurer-run Medicare. The board of the Better Medicare Alliance includes executives who serve with firms that run Advantage plans as well as medical organizations and universities.

“With studies showing that up to one-quarter of all health care expenditures are wasted on services with no benefit to the patient, we need a robust, next-generation prior authorization program to deter low-value, and even harmful, care while protecting access to needed treatment and effective therapies,” said A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Value-Based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor, in a statement issued by the Better Medicare Alliance. He is a member of the group’s council of scholars.

On the House floor on September 14, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), said he has heard from former colleagues and his medical school classmates that they now spend as much as 40% of their time on administrative work. These distractions from patient care are helping drive physicians away from the practice of medicine.

Still, the internist defended the basic premise of prior authorization while strongly appealing for better systems of handling it.

“Yes, there is a role for prior authorization in limited cases. There is also a role to go back and retrospectively look at how care is being delivered,” Rep. Bera said. “But what is happening today is a travesty. It wasn’t the intention of prior authorization. It is a prior authorization process gone awry.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The path through the U.S. Senate is not yet certain for a bill intended to speed the prior authorization process of insurer-run Medicare Advantage plans, despite the measure having breezed through the House.

House leaders opted to move the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021 (HR 3173) without requiring a roll-call vote. The measure was passed on Sept. 14 by a voice vote, an approach used in general with only uncontroversial measures that have broad support. The bill has 191 Democratic and 135 Republican sponsors, representing about three-quarters of the members of the House.

“There is no reason that patients should be waiting for medically appropriate care, especially when we know that this can lead to worse outcomes,” Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) said in a Sept. 14 speech on the House floor. “The fundamental promise of Medicare Advantage is undermined when people are delaying care, getting sicker, and ultimately costing Medicare more money.”

Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-N.C.), spoke on the House floor that day as well, bringing up cases he has seen in his own urology practice in which prior authorization delays disrupted medical care. One patient wound up in the hospital with abscess after an insurer denied an antibiotic prescription, Rep. Murphy said.

But the Senate appears unlikely at this time to move the prior authorization bill as a standalone measure. Instead, the bill may become part of a larger legislative package focused on health care that the Senate Finance Committee intends to prepare later this year.

The House-passed bill would require insurer-run Medicare plans to respond to expedited requests for prior authorization of services within 24 hours and to other requests within 7 days. This bill also would establish an electronic program for prior authorizations and mandate increased transparency as to how insurers use this tool.

CBO: Cost of change would be billions

In seeking to mandate changes in prior authorization, lawmakers likely will need to contend with the issue of a $16 billion cumulative cost estimate for the bill from the Congressional Budget Office. Members of Congress often seek to offset new spending by pairing bills that add to expected costs for the federal government with ones expected to produce savings.

Unlike Rep. Blumenauer, Rep. Murphy, and other backers of the prior authorization streamlining bill, CBO staff estimates that making the mandated changes would raise federal spending, inasmuch as there would be “a greater use of services.”

On Sept. 14, CBO issued a one-page report on the costs of the bill. The CBO report concerns only the bill in question, as is common practice with the office’s estimates.

Prior authorization changes would begin in fiscal 2025 and would add $899 million in spending, or outlays, that year, CBO said. The annual costs from the streamlined prior authorization practices through fiscal 2026 to 2032 range from $1.6 billion to $2.7 billion.

Looking at the CBO estimate against a backdrop of total Medicare Advantage costs, though, may provide important context.

The increases in spending estimated by CBO may suggest that there would be little change in federal spending as a result of streamlining prior authorization practices. These estimates of increased annual spending of $1.6 billion–$2.7 billion are only a small fraction of the current annual cost of insurer-run Medicare, and they represent an even smaller share of the projected expense.

The federal government last year spent about $350 billion on insurer-run plans, excluding Part D drug plan payments, according to the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission (MedPAC).

As of 2021, about 27 million people were enrolled in these plans, accounting for about 46% of the total Medicare population. Enrollment has doubled since 2010, MedPAC said, and it is expected to continue to grow. By 2027, insurer-run Medicare could cover 50% of the program’s population, a figure that may reach 53% by 2031.

Federal payments to these plans will accelerate in the years ahead as insurers attract more people eligible for Medicare as customers. Payments to these private health plans could rise from an expected $418 billion this year to $940.6 billion by 2031, according to the most recent Medicare trustees report.

Good intentions, poor implementation?

Insurer-run Medicare has long enjoyed deep bipartisan support in Congress. That’s due in part to its potential for reducing spending on what are considered low-value treatments, or ones considered unlikely to provide a significant medical benefit, but Rep. Blumenauer is among the members of Congress who see insurer-run Medicare as a path for preserving the giant federal health program. Traditional Medicare has far fewer restrictions on services, which sometimes opens a path for tests and treatments that offer less value for patients.

“I believe that the way traditional fee-for-service Medicare operates is not sustainable and that Medicare Advantage is one of the tools we can use to demonstrate how we can incentivize value,” Rep. Blumenauer said on the House floor. “But this is only possible when the program operates as intended. I have been deeply concerned about the reports of delays in care” caused by the clunky prior authorization processes.

He highlighted a recent report from the internal watchdog group for the Department of Health & Human Services that raises concerns about denials of appropriate care. About 18% of a set of payment denials examined by the Office of Inspector General of HHS in April actually met Medicare coverage rules and plan billing rules.

“For patients and their families, being told that you need to wait longer for care that your doctor tells you that you need is incredibly frustrating and frightening,” Rep. Blumenauer said. “There’s no comfort to be found in the fact that your insurance company needs time to decide if your doctor is right.”

Trends in prior authorization

The CBO report does not provide detail on what kind of medical spending would increase under a streamlined prior authorization process in insurer-run Medicare plans.

From trends reported in prior authorization, though, two factors could be at play in what appear to be relatively small estimated increases in Medicare spending from streamlined prior authorization.

One is the work already underway to create less burdensome electronic systems for these requests, such as the Fast Prior Authorization Technology Highway initiative run by the trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The other factor could be the number of cases in which prior authorization merely causes delays in treatments and tests and thus simply postpones spending while adding to clinicians’ administrative work.

An analysis of prior authorization requests for dermatologic practices affiliated with the University of Utah may represent an extreme example. In a report published in JAMA Dermatology in 2020, researchers described what happened with requests made during 1 month, September 2016.

The approval rate for procedures was 99.6% – 100% (95 of 95) for Mohs surgery, and 96% (130 of 131, with 4 additional cases pending) for excisions. These findings supported calls for simplifying prior authorization procedures, “perhaps first by eliminating unnecessary PAs [prior authorizations] and appeals,” Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and coauthors wrote in the article.

Still, there is some evidence that insurer-run Medicare policies reduce the use of low-value care.

In a study published in JAMA Health Forum, Emily Boudreau, PhD, of insurer Humana Inc, and coauthors from Tufts University, Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia investigated whether insurer-run Medicare could do a better job in reducing the amount of low-value care delivered than the traditional program. They analyzed a set of claims data from 2017 to 2019 for people enrolled in insurer-run and traditional Medicare.

They reported a rate of 23.07 low-value services provided per 100 people in insurer-run Medicare, compared with 25.39 for those in traditional Medicare. Some of the biggest differences reported in the article were in cancer screenings for older people.

As an example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women older than 65 years not be screened for cervical cancer if they have undergone adequate screening in the past and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. There was an annual count of 1.76 screenings for cervical cancer per 100 women older than 65 in the insurer-run Medicare group versus 3.18 for those in traditional Medicare.

The Better Medicare Alliance issued a statement in favor of the House passage of the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act.

In it, the group said the measure would “modernize prior authorization while protecting its essential function in facilitating safe, high-value, evidence-based care.” The alliance promotes use of insurer-run Medicare. The board of the Better Medicare Alliance includes executives who serve with firms that run Advantage plans as well as medical organizations and universities.

“With studies showing that up to one-quarter of all health care expenditures are wasted on services with no benefit to the patient, we need a robust, next-generation prior authorization program to deter low-value, and even harmful, care while protecting access to needed treatment and effective therapies,” said A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Value-Based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor, in a statement issued by the Better Medicare Alliance. He is a member of the group’s council of scholars.

On the House floor on September 14, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), said he has heard from former colleagues and his medical school classmates that they now spend as much as 40% of their time on administrative work. These distractions from patient care are helping drive physicians away from the practice of medicine.

Still, the internist defended the basic premise of prior authorization while strongly appealing for better systems of handling it.

“Yes, there is a role for prior authorization in limited cases. There is also a role to go back and retrospectively look at how care is being delivered,” Rep. Bera said. “But what is happening today is a travesty. It wasn’t the intention of prior authorization. It is a prior authorization process gone awry.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WHO releases six ‘action steps’ to combat global disparities in Parkinson’s disease

Since 2000, Parkinson’s disease has increased 81% and related deaths have increased 100% globally. In addition, many patients affected by Parkinson’s disease live in low- and middle-income countries and experience large inequalities in access to neurologic care and essential medicines.

To address these issues, the Brain Health Unit at the WHO developed six “action steps” it says are urgently required to combat global disparities in Parkinson’s disease.

The need for action is great, said lead author Nicoline Schiess, MD, MPH, a neurologist and technical officer in the WHO’s Brain Health Unit in Geneva.

“In adults, disorders of the nervous system are the leading cause of disability adjusted life years, or DALYs, and the second leading cause of death globally, accounting for 9 million deaths per year,” Dr. Schiess said.

The WHO’s recommendations were published online recently as a “Special Communication” in JAMA Neurology.

Serious public health challenge

Parkinson’s disease is the fastest growing disorder in terms of death and disability, and it is estimated that it caused 329,000 deaths in 2019 – an increase of more than 100% since 2000.

“The rise in cases is thought to be multifactorial and is likely affected by factors such as aging populations and environmental exposures, such as certain pesticides. With these rapidly increasing numbers, compounded by a lack of specialists and medicines in low- and middle-income countries, Parkinson’s disease presents a serious public health challenge,” Dr. Schiess said.

The publication of the six action steps is targeted toward clinicians and researchers who work in Parkinson’s disease, she added. The steps address the following areas:

- 1. Disease burden

- 2. Advocacy and awareness

- 3. Prevention and risk reduction

- 4. Diagnosis, treatment, and care

- 5. Caregiver support

- 6. Research

Dr. Schiess noted that data on disease burden are lacking in certain areas of the world, such as low- and middle-income countries, and information “based on race and ethnicity are inconsistent. Studies are needed to establish more representative epidemiological data.”

She said that advocacy and awareness are particularly important since young people may not be aware they can also develop Parkinson’s disease, and sex and race differences can factor in to the potential for delays in diagnosis and care. “This is often due to the incorrect perception that Parkinson’s disease only affects older people,” she noted.

In addition, “a substantial need exists to identify risks for Parkinson’s disease – in particular the risks we can mitigate,” said Dr. Schiess, citing pesticide exposure as one example. “The evidence linking pesticide exposure, for example paraquat and chlorpyrifos, with the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease is substantial. And yet in many countries, these products are still being used.”