User login

The Official Newspaper of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery

Mitral valve disease often missed in pulmonary hypertension

LOS ANGELES – Dyspnea in pulmonary hypertension is caused by mitral valve disease until proven otherwise, according to Paul Forfia, MD, director of pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure, and pulmonary thromboendarterectomy at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Although mitral valve disease is a well-recognized cause of pulmonary hypertension, its significance is often underestimated in practice.

“Whether the valve is regurgitant or stenotic makes absolutely no difference. When you delay” repair or replacement, “the patient keeps getting sicker,” he said. In time, “everyone is standing around wringing their hands going, ‘Oh my god, what are we going to do? Are you serious? Fix the valve.’ We see this type of patient a couple times a month,” Dr. Forfia said at the American College of Chest Physicians annual meeting.

“I have seen lifesaving mitral valve surgery put off for many years in patients with pulmonary hypertension, when all they needed was to have their valve fixed,” he said.

Whatever the case, pulmonologists who want the valve fixed often end up playing patient ping pong with cardiologists who want the hypertension controlled beforehand, but “if I treat the pulmonary circulation first, all I am going to do is unmask the left heart failure. There will be no functional improvement whatsoever,” Dr. Forfia said.

Surgery is the best solution as long as patients are well enough to recover. “With pulmonary hypertension in the setting of severe mitral valve regurgitation or stenosis, whether the pulmonary hypertension is related to passive left heart congestion or associated with pulmonary arteriopathy, the only sensible option is to correct the underlying valvular abnormality,” he said. The surgery should be done at an institution capable of managing postop pulmonary arteriopathy, if present.

The ping pong solution is to send patients to an expert pulmonology center; the mitral valve problem will be spotted right away.

“There is no pulmonary pressure cutoff that should prohibit surgery” in patients able to recover. “There is no such thing as a pulmonary artery pressure too high to be explained by mitral valve disease. The pulmonary pressure can be as high as it wants to be. You will get nowhere by thinking the pressure is too high to address the valve,” Dr. Forfia said.

Often “you hear, ‘I’m afraid the person is going to die on the table.’ I always say ‘if the patient is not going to die on the table, they are going to die in their living room of progressive heart failure because you [didn’t] fix their valve. I have never had a patient with pulmonary hypertension not separate from cardiopulmonary bypass. It’s a myth,” he said.

When there’s a “question if the dyspnea is coming from the mitral valve, we routinely use exercise right heart catheterization to probe the situation. We have a recumbent bike in the cath lab. You’ll often provoke significant left heart congestion with a low workload. It’s very revealing to the significance of mitral valve disease,” he said.

Aortic valve disease is also missed in pulmonary hypertension. “It’s not [a] similar” problem; “it’s the same” problem, Dr. Forfia said.

Dr. Forfia is a consultant for Bayer, Actelion, and United Therapeutics.

LOS ANGELES – Dyspnea in pulmonary hypertension is caused by mitral valve disease until proven otherwise, according to Paul Forfia, MD, director of pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure, and pulmonary thromboendarterectomy at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Although mitral valve disease is a well-recognized cause of pulmonary hypertension, its significance is often underestimated in practice.

“Whether the valve is regurgitant or stenotic makes absolutely no difference. When you delay” repair or replacement, “the patient keeps getting sicker,” he said. In time, “everyone is standing around wringing their hands going, ‘Oh my god, what are we going to do? Are you serious? Fix the valve.’ We see this type of patient a couple times a month,” Dr. Forfia said at the American College of Chest Physicians annual meeting.

“I have seen lifesaving mitral valve surgery put off for many years in patients with pulmonary hypertension, when all they needed was to have their valve fixed,” he said.

Whatever the case, pulmonologists who want the valve fixed often end up playing patient ping pong with cardiologists who want the hypertension controlled beforehand, but “if I treat the pulmonary circulation first, all I am going to do is unmask the left heart failure. There will be no functional improvement whatsoever,” Dr. Forfia said.

Surgery is the best solution as long as patients are well enough to recover. “With pulmonary hypertension in the setting of severe mitral valve regurgitation or stenosis, whether the pulmonary hypertension is related to passive left heart congestion or associated with pulmonary arteriopathy, the only sensible option is to correct the underlying valvular abnormality,” he said. The surgery should be done at an institution capable of managing postop pulmonary arteriopathy, if present.

The ping pong solution is to send patients to an expert pulmonology center; the mitral valve problem will be spotted right away.

“There is no pulmonary pressure cutoff that should prohibit surgery” in patients able to recover. “There is no such thing as a pulmonary artery pressure too high to be explained by mitral valve disease. The pulmonary pressure can be as high as it wants to be. You will get nowhere by thinking the pressure is too high to address the valve,” Dr. Forfia said.

Often “you hear, ‘I’m afraid the person is going to die on the table.’ I always say ‘if the patient is not going to die on the table, they are going to die in their living room of progressive heart failure because you [didn’t] fix their valve. I have never had a patient with pulmonary hypertension not separate from cardiopulmonary bypass. It’s a myth,” he said.

When there’s a “question if the dyspnea is coming from the mitral valve, we routinely use exercise right heart catheterization to probe the situation. We have a recumbent bike in the cath lab. You’ll often provoke significant left heart congestion with a low workload. It’s very revealing to the significance of mitral valve disease,” he said.

Aortic valve disease is also missed in pulmonary hypertension. “It’s not [a] similar” problem; “it’s the same” problem, Dr. Forfia said.

Dr. Forfia is a consultant for Bayer, Actelion, and United Therapeutics.

LOS ANGELES – Dyspnea in pulmonary hypertension is caused by mitral valve disease until proven otherwise, according to Paul Forfia, MD, director of pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure, and pulmonary thromboendarterectomy at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Although mitral valve disease is a well-recognized cause of pulmonary hypertension, its significance is often underestimated in practice.

“Whether the valve is regurgitant or stenotic makes absolutely no difference. When you delay” repair or replacement, “the patient keeps getting sicker,” he said. In time, “everyone is standing around wringing their hands going, ‘Oh my god, what are we going to do? Are you serious? Fix the valve.’ We see this type of patient a couple times a month,” Dr. Forfia said at the American College of Chest Physicians annual meeting.

“I have seen lifesaving mitral valve surgery put off for many years in patients with pulmonary hypertension, when all they needed was to have their valve fixed,” he said.

Whatever the case, pulmonologists who want the valve fixed often end up playing patient ping pong with cardiologists who want the hypertension controlled beforehand, but “if I treat the pulmonary circulation first, all I am going to do is unmask the left heart failure. There will be no functional improvement whatsoever,” Dr. Forfia said.

Surgery is the best solution as long as patients are well enough to recover. “With pulmonary hypertension in the setting of severe mitral valve regurgitation or stenosis, whether the pulmonary hypertension is related to passive left heart congestion or associated with pulmonary arteriopathy, the only sensible option is to correct the underlying valvular abnormality,” he said. The surgery should be done at an institution capable of managing postop pulmonary arteriopathy, if present.

The ping pong solution is to send patients to an expert pulmonology center; the mitral valve problem will be spotted right away.

“There is no pulmonary pressure cutoff that should prohibit surgery” in patients able to recover. “There is no such thing as a pulmonary artery pressure too high to be explained by mitral valve disease. The pulmonary pressure can be as high as it wants to be. You will get nowhere by thinking the pressure is too high to address the valve,” Dr. Forfia said.

Often “you hear, ‘I’m afraid the person is going to die on the table.’ I always say ‘if the patient is not going to die on the table, they are going to die in their living room of progressive heart failure because you [didn’t] fix their valve. I have never had a patient with pulmonary hypertension not separate from cardiopulmonary bypass. It’s a myth,” he said.

When there’s a “question if the dyspnea is coming from the mitral valve, we routinely use exercise right heart catheterization to probe the situation. We have a recumbent bike in the cath lab. You’ll often provoke significant left heart congestion with a low workload. It’s very revealing to the significance of mitral valve disease,” he said.

Aortic valve disease is also missed in pulmonary hypertension. “It’s not [a] similar” problem; “it’s the same” problem, Dr. Forfia said.

Dr. Forfia is a consultant for Bayer, Actelion, and United Therapeutics.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CHEST 2016

Blood assay rapidly identifies lung cancer mutations

LOS ANGELES – A newer blood test (GeneStrat from Biodesix) identified genetic mutations in lung tumors in about 24 hours, allowing for an early start of mutation-specific chemotherapy, in an investigation from Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wis.

Interventional pulmonologists drew blood samples when they performed biopsies on 84 patients with highly suspicious lung nodules and submitted both blood and tissue for mutation analysis. The blood was analyzed by Biodesix, the maker of GeneStrat, a commercially available digital droplet polymerase change reaction assay launched in 2015. The company sent the results back in an average of 24.1 hours, and all within 72 hours. The mutation results from tissue analysis took 2-3 weeks.

Fifteen patients (18%) had actionable epidermal growth factor receptor, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, or K-Ras protein gene mutations, and were candidates for targeted therapy. Compared with tissue testing, the blood assay had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 99%. The tissue testing picked up two mutations missed by blood testing. One of the two mutations is rare and was not included in the blood assay. Meanwhile, the assay caught a mutation missed on tissue analysis.

She and her colleagues are now routinely using GeneStrat to guide initial lung cancer therapy. “The turnaround time is fantastic. It allows us to have [the mutation status] when oncologists meet with patients for the very first time,” she said.

It “definitely” makes a difference. “If you have an actionable mutation and there’s a targeted chemotherapy” – such as erlotinib (Tarceva) for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patients – it can be started right out of the gate. “Time to treatment is very important,” not just psychologically for patients but also for them to have the best chance against the tumor. The sooner “we can start a targeted therapy,” the better outcomes are likely to be, Dr. Mattingley said.

When mutation status is delayed, patients might be started “on the wrong therapy upfront, and it’s really hard to back up and start over again,” she said.

“Once we give patients a diagnosis of lung cancer, the next thing they should hear right away is how we are going to attack it. We felt strongly [that there was a] need to look at this to see if we could truly expedite the time from diagnosis to treatment. We believe our patients should have no sleepless nights,” Dr. Mattingley said.

There’s also usually not much tissue left after genetic work-up to send into a clinical trial. Using blood to identify mutations “may allow us to conserve our tissue block for future trials, but still get the genetic information we need to start treatment plans for our patients,” she said.

There was no company funding for the work, but Dr. Mattingley is a speaker for GeneStrat’s maker, Biodesix.

The results of this study are very promising. The high concordance between liquid biopsies and tissue biopsies as well as the short turn-around time for the results of the liquid biopsies makes a big difference in terms of getting patients started on appropriate therapy sooner rather than later. We need additional studies to find out if liquid biopsies will be good for detection of other molecular alterations such as ROS-1 and EGFR acquired mutation T790M.

The results of this study are very promising. The high concordance between liquid biopsies and tissue biopsies as well as the short turn-around time for the results of the liquid biopsies makes a big difference in terms of getting patients started on appropriate therapy sooner rather than later. We need additional studies to find out if liquid biopsies will be good for detection of other molecular alterations such as ROS-1 and EGFR acquired mutation T790M.

The results of this study are very promising. The high concordance between liquid biopsies and tissue biopsies as well as the short turn-around time for the results of the liquid biopsies makes a big difference in terms of getting patients started on appropriate therapy sooner rather than later. We need additional studies to find out if liquid biopsies will be good for detection of other molecular alterations such as ROS-1 and EGFR acquired mutation T790M.

LOS ANGELES – A newer blood test (GeneStrat from Biodesix) identified genetic mutations in lung tumors in about 24 hours, allowing for an early start of mutation-specific chemotherapy, in an investigation from Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wis.

Interventional pulmonologists drew blood samples when they performed biopsies on 84 patients with highly suspicious lung nodules and submitted both blood and tissue for mutation analysis. The blood was analyzed by Biodesix, the maker of GeneStrat, a commercially available digital droplet polymerase change reaction assay launched in 2015. The company sent the results back in an average of 24.1 hours, and all within 72 hours. The mutation results from tissue analysis took 2-3 weeks.

Fifteen patients (18%) had actionable epidermal growth factor receptor, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, or K-Ras protein gene mutations, and were candidates for targeted therapy. Compared with tissue testing, the blood assay had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 99%. The tissue testing picked up two mutations missed by blood testing. One of the two mutations is rare and was not included in the blood assay. Meanwhile, the assay caught a mutation missed on tissue analysis.

She and her colleagues are now routinely using GeneStrat to guide initial lung cancer therapy. “The turnaround time is fantastic. It allows us to have [the mutation status] when oncologists meet with patients for the very first time,” she said.

It “definitely” makes a difference. “If you have an actionable mutation and there’s a targeted chemotherapy” – such as erlotinib (Tarceva) for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patients – it can be started right out of the gate. “Time to treatment is very important,” not just psychologically for patients but also for them to have the best chance against the tumor. The sooner “we can start a targeted therapy,” the better outcomes are likely to be, Dr. Mattingley said.

When mutation status is delayed, patients might be started “on the wrong therapy upfront, and it’s really hard to back up and start over again,” she said.

“Once we give patients a diagnosis of lung cancer, the next thing they should hear right away is how we are going to attack it. We felt strongly [that there was a] need to look at this to see if we could truly expedite the time from diagnosis to treatment. We believe our patients should have no sleepless nights,” Dr. Mattingley said.

There’s also usually not much tissue left after genetic work-up to send into a clinical trial. Using blood to identify mutations “may allow us to conserve our tissue block for future trials, but still get the genetic information we need to start treatment plans for our patients,” she said.

There was no company funding for the work, but Dr. Mattingley is a speaker for GeneStrat’s maker, Biodesix.

LOS ANGELES – A newer blood test (GeneStrat from Biodesix) identified genetic mutations in lung tumors in about 24 hours, allowing for an early start of mutation-specific chemotherapy, in an investigation from Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wis.

Interventional pulmonologists drew blood samples when they performed biopsies on 84 patients with highly suspicious lung nodules and submitted both blood and tissue for mutation analysis. The blood was analyzed by Biodesix, the maker of GeneStrat, a commercially available digital droplet polymerase change reaction assay launched in 2015. The company sent the results back in an average of 24.1 hours, and all within 72 hours. The mutation results from tissue analysis took 2-3 weeks.

Fifteen patients (18%) had actionable epidermal growth factor receptor, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, or K-Ras protein gene mutations, and were candidates for targeted therapy. Compared with tissue testing, the blood assay had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 99%. The tissue testing picked up two mutations missed by blood testing. One of the two mutations is rare and was not included in the blood assay. Meanwhile, the assay caught a mutation missed on tissue analysis.

She and her colleagues are now routinely using GeneStrat to guide initial lung cancer therapy. “The turnaround time is fantastic. It allows us to have [the mutation status] when oncologists meet with patients for the very first time,” she said.

It “definitely” makes a difference. “If you have an actionable mutation and there’s a targeted chemotherapy” – such as erlotinib (Tarceva) for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation patients – it can be started right out of the gate. “Time to treatment is very important,” not just psychologically for patients but also for them to have the best chance against the tumor. The sooner “we can start a targeted therapy,” the better outcomes are likely to be, Dr. Mattingley said.

When mutation status is delayed, patients might be started “on the wrong therapy upfront, and it’s really hard to back up and start over again,” she said.

“Once we give patients a diagnosis of lung cancer, the next thing they should hear right away is how we are going to attack it. We felt strongly [that there was a] need to look at this to see if we could truly expedite the time from diagnosis to treatment. We believe our patients should have no sleepless nights,” Dr. Mattingley said.

There’s also usually not much tissue left after genetic work-up to send into a clinical trial. Using blood to identify mutations “may allow us to conserve our tissue block for future trials, but still get the genetic information we need to start treatment plans for our patients,” she said.

There was no company funding for the work, but Dr. Mattingley is a speaker for GeneStrat’s maker, Biodesix.

AT CHEST 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with tissue testing, the blood assay had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 99%.

Data source: Eighty-four patients with highly suspicious lung nodules.

Disclosures: There was no company funding for the work, but the presenter is a paid speaker for GeneStrat’s maker, Biodesix.

Prognostic scores helpful in subset of COPD patients

LOS ANGELES – The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) are simple, accurate tools for risk stratification of hospitalized patients with acute exacerbation of COPD, results from a single-center study showed.

“Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease often require hospitalization, may necessitate mechanical ventilation, and can be fatal,” Mohamed Metwally, MD, FCCP, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “There are currently no validated disease-specific scores that measure the severity of acute exacerbation. Prognostic tools are needed to assess acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.”

For the 2-year study, Dr. Metwally and his associates prospectively evaluated 250 critically ill ICU AECOPD patients, mean age 65 years, at Assiut University Hospital between December 2012 and December 2014. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality while the secondary endpoint was need for intubation and mechanical ventilation. The researchers excluded patients who died less than 24 hours after admission, those with underlying COPD who were admitted with another primary diagnosis such as an accident or a stroke, or for elective hospitalizations such as elective surgery or diagnostic procedures.

Dr. Metwally and his associates collected sociodemographic data, vital signs, and other clinical variables, and collected scores from five tools used to measure mortality prediction: the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II), the SOFA score, the Early Warning Score (EWS), the GCS, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). To assess performance of the scores, they used area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for logistic regression.

Of the 250 patients, 43 (17%) died during their hospital stay and 54% required mechanical ventilation. All recorded scores were significantly higher in nonsurvivors, compared with survivors, and the risk of clinical deterioration increased with increasing scores. The discriminatory power of each score varied as measured by AUC analysis. The AUC of APACHE II, SOFA, EWS, GCS, and CCI were 0.79, 0.81, 0.76, 0.69, and 0.68, respectively “and all these models had good calibration in mortality prediction,” Dr. Metwally said. The SOFA score was the best in predicting mortality (its predicted mortality was 16%, compared with the actual mortality of 17%), while the APACHE II score overestimated mortality by at least twofold (46% vs. 17%). In addition, the EWS outperformed the GCS in predicting mortality. “This may be due to EWS containing all vital signs plus level of consciousness,” he said in an interview.

The GCS was found to be the most useful in predicting need for mechanical ventilation, with an AUC of 0.81. The AUCs of APACHE II, SOFA, EWS, and CCI were 0.79, 0.80, 0.73, and 0.61, respectively. All of the scores had good calibration in mortality prediction, Dr. Metwally said, with the exception of SOFA.

As for the APACHE II, Dr. Metwally said that instrument “can be used as a tool to predict both mortality and intubation in a specific group of patients, but with low discriminatory power.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was limited to patients with AECOPD. “Future studies should include any critically ill respiratory patients,” he said.

He reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) are simple, accurate tools for risk stratification of hospitalized patients with acute exacerbation of COPD, results from a single-center study showed.

“Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease often require hospitalization, may necessitate mechanical ventilation, and can be fatal,” Mohamed Metwally, MD, FCCP, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “There are currently no validated disease-specific scores that measure the severity of acute exacerbation. Prognostic tools are needed to assess acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.”

For the 2-year study, Dr. Metwally and his associates prospectively evaluated 250 critically ill ICU AECOPD patients, mean age 65 years, at Assiut University Hospital between December 2012 and December 2014. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality while the secondary endpoint was need for intubation and mechanical ventilation. The researchers excluded patients who died less than 24 hours after admission, those with underlying COPD who were admitted with another primary diagnosis such as an accident or a stroke, or for elective hospitalizations such as elective surgery or diagnostic procedures.

Dr. Metwally and his associates collected sociodemographic data, vital signs, and other clinical variables, and collected scores from five tools used to measure mortality prediction: the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II), the SOFA score, the Early Warning Score (EWS), the GCS, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). To assess performance of the scores, they used area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for logistic regression.

Of the 250 patients, 43 (17%) died during their hospital stay and 54% required mechanical ventilation. All recorded scores were significantly higher in nonsurvivors, compared with survivors, and the risk of clinical deterioration increased with increasing scores. The discriminatory power of each score varied as measured by AUC analysis. The AUC of APACHE II, SOFA, EWS, GCS, and CCI were 0.79, 0.81, 0.76, 0.69, and 0.68, respectively “and all these models had good calibration in mortality prediction,” Dr. Metwally said. The SOFA score was the best in predicting mortality (its predicted mortality was 16%, compared with the actual mortality of 17%), while the APACHE II score overestimated mortality by at least twofold (46% vs. 17%). In addition, the EWS outperformed the GCS in predicting mortality. “This may be due to EWS containing all vital signs plus level of consciousness,” he said in an interview.

The GCS was found to be the most useful in predicting need for mechanical ventilation, with an AUC of 0.81. The AUCs of APACHE II, SOFA, EWS, and CCI were 0.79, 0.80, 0.73, and 0.61, respectively. All of the scores had good calibration in mortality prediction, Dr. Metwally said, with the exception of SOFA.

As for the APACHE II, Dr. Metwally said that instrument “can be used as a tool to predict both mortality and intubation in a specific group of patients, but with low discriminatory power.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was limited to patients with AECOPD. “Future studies should include any critically ill respiratory patients,” he said.

He reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) are simple, accurate tools for risk stratification of hospitalized patients with acute exacerbation of COPD, results from a single-center study showed.

“Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease often require hospitalization, may necessitate mechanical ventilation, and can be fatal,” Mohamed Metwally, MD, FCCP, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. “There are currently no validated disease-specific scores that measure the severity of acute exacerbation. Prognostic tools are needed to assess acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.”

For the 2-year study, Dr. Metwally and his associates prospectively evaluated 250 critically ill ICU AECOPD patients, mean age 65 years, at Assiut University Hospital between December 2012 and December 2014. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality while the secondary endpoint was need for intubation and mechanical ventilation. The researchers excluded patients who died less than 24 hours after admission, those with underlying COPD who were admitted with another primary diagnosis such as an accident or a stroke, or for elective hospitalizations such as elective surgery or diagnostic procedures.

Dr. Metwally and his associates collected sociodemographic data, vital signs, and other clinical variables, and collected scores from five tools used to measure mortality prediction: the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II), the SOFA score, the Early Warning Score (EWS), the GCS, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). To assess performance of the scores, they used area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for logistic regression.

Of the 250 patients, 43 (17%) died during their hospital stay and 54% required mechanical ventilation. All recorded scores were significantly higher in nonsurvivors, compared with survivors, and the risk of clinical deterioration increased with increasing scores. The discriminatory power of each score varied as measured by AUC analysis. The AUC of APACHE II, SOFA, EWS, GCS, and CCI were 0.79, 0.81, 0.76, 0.69, and 0.68, respectively “and all these models had good calibration in mortality prediction,” Dr. Metwally said. The SOFA score was the best in predicting mortality (its predicted mortality was 16%, compared with the actual mortality of 17%), while the APACHE II score overestimated mortality by at least twofold (46% vs. 17%). In addition, the EWS outperformed the GCS in predicting mortality. “This may be due to EWS containing all vital signs plus level of consciousness,” he said in an interview.

The GCS was found to be the most useful in predicting need for mechanical ventilation, with an AUC of 0.81. The AUCs of APACHE II, SOFA, EWS, and CCI were 0.79, 0.80, 0.73, and 0.61, respectively. All of the scores had good calibration in mortality prediction, Dr. Metwally said, with the exception of SOFA.

As for the APACHE II, Dr. Metwally said that instrument “can be used as a tool to predict both mortality and intubation in a specific group of patients, but with low discriminatory power.” He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it was limited to patients with AECOPD. “Future studies should include any critically ill respiratory patients,” he said.

He reported having no financial disclosures.

AT CHEST 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was the best in predicting mortality of patients with acute exacerbation of COPD (its predicted mortality was 16%, compared with the actual mortality of 17%).

Data source: A prospective evaluation of 250 critically ill ICU patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD.

Disclosures: Dr. Metwally reported having no financial disclosures.

Balancing speed, safety in device approvals

WASHINGTON – Regulators from two continents are slowly inching toward more common ground when it comes to device approvals, a move that should strike a better balance between the time to approval and safety of the products.

It is no surprise that for devices to be approved in the United States, a much more rigorous evidence standard exists than it does in Europe, but the Food and Drug Administration is looking for ways to make changes to allow for quicker approval times without compromising safety.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, European regulators are looking for increased evidence requirements that will not stifle innovation.

However, health information technology may help relieve some inefficiencies going forward.

“If we combine quality registries, claims data, the evolving improving electronic health records, and the data warehouses that all of our health systems have, we can conduct prospective, observational, and clinical trials at a dramatically lower cost, answering many more questions per unit of time,” Dr. Califf added.

Other areas that will help improve the efficiency of the U.S. approval process is the work on developing a framework to bring feasibility studies back to America.

“I want to really accelerate that because we are hearing from a lot of people that they want to access the technology early; it’s the right thing to do, and we are hearing from industry that they’d like to work in the United States,” he said.

However, that is going to require one group that is generally more risk adverse to be willing to participate more in the process.

“The main limiting factors at this point in time are the health systems that we are all working in,” Dr. Califf noted. “They are very risk adverse. So while it is nice to argue and advertise that your interventional cardiologists are the best in town on your billboard, protecting those interventional cardiologists to do the high-risk, early studies that are really needed to develop devices is a different matter.”

He called on doctors to go back to their health systems to help better develop those early feasibility pathways to help bring some of that innovation back the United States.

Finally, Dr. Califf addressed the idea of developing evidence that can function not only for device approval, but for payment as well, especially as reimbursement systems are becoming more value driven.

“We are going to move to a system where reimbursement will increasingly move away from fee for service and increasingly gravitate to payment for value,” Dr. Califf said. “In order for this to work, we’ve got to develop the kinds of clinical trials [that include] the calculation of value, so the winners can be promoted on a wider scale and the procedures and technologies that don’t provide incremental value are left behind.”

He continued: “We need your help in figuring out the common source of information so that the FDA can make its decision – which is different from CMS’s decision – but where there’s a continuum of knowledge that allows for products to be approved if they are worthwhile, and then to be paid for and allowed to be marketed.”

Meanwhile, developers are facing a different situation in Europe, where more regulation and more stringent evidence standards could be coming down the pike.

Dr. Fraser noted research that has shown that devices first approved in Europe, compared with their U.S. counterparts, are associated with an increased incidence of recalls or safety alerts.

That being said, he noted that there are several proposed regulations that would increase the evidence requirements related to regulatory approval that manufacturers could face in the coming year, a challenge as it will require some level of harmonization across countries and regulatory systems within each country.

“In Europe, we are on the dawn of a new era regarding medical device assessment, but it is going to pose a very large challenge for our colleagues in the regulatory agencies because of their personnel, funding, and the integration between all these bodies and national systems. There are also tremendous challenges for us as physicians to ensure that we seek the evidence, we assess and contribute to it, and particularly now, that we also routinely take part in new systems for postmarket surveillance,” he said.

WASHINGTON – Regulators from two continents are slowly inching toward more common ground when it comes to device approvals, a move that should strike a better balance between the time to approval and safety of the products.

It is no surprise that for devices to be approved in the United States, a much more rigorous evidence standard exists than it does in Europe, but the Food and Drug Administration is looking for ways to make changes to allow for quicker approval times without compromising safety.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, European regulators are looking for increased evidence requirements that will not stifle innovation.

However, health information technology may help relieve some inefficiencies going forward.

“If we combine quality registries, claims data, the evolving improving electronic health records, and the data warehouses that all of our health systems have, we can conduct prospective, observational, and clinical trials at a dramatically lower cost, answering many more questions per unit of time,” Dr. Califf added.

Other areas that will help improve the efficiency of the U.S. approval process is the work on developing a framework to bring feasibility studies back to America.

“I want to really accelerate that because we are hearing from a lot of people that they want to access the technology early; it’s the right thing to do, and we are hearing from industry that they’d like to work in the United States,” he said.

However, that is going to require one group that is generally more risk adverse to be willing to participate more in the process.

“The main limiting factors at this point in time are the health systems that we are all working in,” Dr. Califf noted. “They are very risk adverse. So while it is nice to argue and advertise that your interventional cardiologists are the best in town on your billboard, protecting those interventional cardiologists to do the high-risk, early studies that are really needed to develop devices is a different matter.”

He called on doctors to go back to their health systems to help better develop those early feasibility pathways to help bring some of that innovation back the United States.

Finally, Dr. Califf addressed the idea of developing evidence that can function not only for device approval, but for payment as well, especially as reimbursement systems are becoming more value driven.

“We are going to move to a system where reimbursement will increasingly move away from fee for service and increasingly gravitate to payment for value,” Dr. Califf said. “In order for this to work, we’ve got to develop the kinds of clinical trials [that include] the calculation of value, so the winners can be promoted on a wider scale and the procedures and technologies that don’t provide incremental value are left behind.”

He continued: “We need your help in figuring out the common source of information so that the FDA can make its decision – which is different from CMS’s decision – but where there’s a continuum of knowledge that allows for products to be approved if they are worthwhile, and then to be paid for and allowed to be marketed.”

Meanwhile, developers are facing a different situation in Europe, where more regulation and more stringent evidence standards could be coming down the pike.

Dr. Fraser noted research that has shown that devices first approved in Europe, compared with their U.S. counterparts, are associated with an increased incidence of recalls or safety alerts.

That being said, he noted that there are several proposed regulations that would increase the evidence requirements related to regulatory approval that manufacturers could face in the coming year, a challenge as it will require some level of harmonization across countries and regulatory systems within each country.

“In Europe, we are on the dawn of a new era regarding medical device assessment, but it is going to pose a very large challenge for our colleagues in the regulatory agencies because of their personnel, funding, and the integration between all these bodies and national systems. There are also tremendous challenges for us as physicians to ensure that we seek the evidence, we assess and contribute to it, and particularly now, that we also routinely take part in new systems for postmarket surveillance,” he said.

WASHINGTON – Regulators from two continents are slowly inching toward more common ground when it comes to device approvals, a move that should strike a better balance between the time to approval and safety of the products.

It is no surprise that for devices to be approved in the United States, a much more rigorous evidence standard exists than it does in Europe, but the Food and Drug Administration is looking for ways to make changes to allow for quicker approval times without compromising safety.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, European regulators are looking for increased evidence requirements that will not stifle innovation.

However, health information technology may help relieve some inefficiencies going forward.

“If we combine quality registries, claims data, the evolving improving electronic health records, and the data warehouses that all of our health systems have, we can conduct prospective, observational, and clinical trials at a dramatically lower cost, answering many more questions per unit of time,” Dr. Califf added.

Other areas that will help improve the efficiency of the U.S. approval process is the work on developing a framework to bring feasibility studies back to America.

“I want to really accelerate that because we are hearing from a lot of people that they want to access the technology early; it’s the right thing to do, and we are hearing from industry that they’d like to work in the United States,” he said.

However, that is going to require one group that is generally more risk adverse to be willing to participate more in the process.

“The main limiting factors at this point in time are the health systems that we are all working in,” Dr. Califf noted. “They are very risk adverse. So while it is nice to argue and advertise that your interventional cardiologists are the best in town on your billboard, protecting those interventional cardiologists to do the high-risk, early studies that are really needed to develop devices is a different matter.”

He called on doctors to go back to their health systems to help better develop those early feasibility pathways to help bring some of that innovation back the United States.

Finally, Dr. Califf addressed the idea of developing evidence that can function not only for device approval, but for payment as well, especially as reimbursement systems are becoming more value driven.

“We are going to move to a system where reimbursement will increasingly move away from fee for service and increasingly gravitate to payment for value,” Dr. Califf said. “In order for this to work, we’ve got to develop the kinds of clinical trials [that include] the calculation of value, so the winners can be promoted on a wider scale and the procedures and technologies that don’t provide incremental value are left behind.”

He continued: “We need your help in figuring out the common source of information so that the FDA can make its decision – which is different from CMS’s decision – but where there’s a continuum of knowledge that allows for products to be approved if they are worthwhile, and then to be paid for and allowed to be marketed.”

Meanwhile, developers are facing a different situation in Europe, where more regulation and more stringent evidence standards could be coming down the pike.

Dr. Fraser noted research that has shown that devices first approved in Europe, compared with their U.S. counterparts, are associated with an increased incidence of recalls or safety alerts.

That being said, he noted that there are several proposed regulations that would increase the evidence requirements related to regulatory approval that manufacturers could face in the coming year, a challenge as it will require some level of harmonization across countries and regulatory systems within each country.

“In Europe, we are on the dawn of a new era regarding medical device assessment, but it is going to pose a very large challenge for our colleagues in the regulatory agencies because of their personnel, funding, and the integration between all these bodies and national systems. There are also tremendous challenges for us as physicians to ensure that we seek the evidence, we assess and contribute to it, and particularly now, that we also routinely take part in new systems for postmarket surveillance,” he said.

AT TCT 2016

Comorbidities common in COPD patients

LOS ANGELES – Comorbidities are common in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, especially cardiovascular disease, diabetes, anemia, and osteoporosis, results from a single-center analysis showed.

“These affect the course and outcome of COPD, so identification and treatment of these comorbidities is very important,” Hamdy Mohammadien, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In an effort to estimate the presence of comorbidities in patients with COPD and to assess the relationship of comorbid diseases with age, sex, C-reactive protein, and COPD severity, Dr. Mohammadien and his associates at Sohag (Egypt) University, retrospectively evaluated 400 COPD patients who were at least 40 years of age. Those who presented with bronchial asthma or other lung diseases were excluded from the analysis. The mean age of patients was 62 years, 69% were male, and 36% were current smokers. Their mean FEV1/FVC ratio (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity) was 48%, and 57% had two or more exacerbations in the previous year.

Dr. Mohammadien reported that all patients had at least one comorbidity. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases (85%), diabetes (35%), dyslipidemia (23%), osteopenia (11%), anemia (10%), muscle wasting (9%), pneumonia (7%), osteoporosis (6%), GERD (2%), and lung cancer (2%). He also noted that the association between cardiovascular events, dyslipidemia, diabetes, osteoporosis, muscle wasting, and anemia was highly significant in COPD patients aged 60 years and older, in men, and in patients with stage III and IV COPD. In addition, a significant relationship was observed between a positive CRP level and each comorbidity, with the exception of gastroesophageal reflux disease and lung cancer. The three comorbidities with the greatest significance were ischemic heart disease (P = .0001), dyslipidemia (P = .0001), and pneumonia (P = .0003). Finally, frequent exacerbators were significantly more likely to have two or more comorbidities (odds ratio 2; P = .04) and to have more hospitalizations in the past year (P less than .01).

“Comorbidities are common in patients with COPD, and have a significant impact on health status and prognosis, thus justifying the need for a comprehensive and integrating therapeutic approach,” Dr. Mohammadien said at the meeting. “In the management of COPD all these conditions need to be carefully evaluated and treated.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that bone density was measured by sonar and not by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Dr. Mohammadien reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Comorbidities are common in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, especially cardiovascular disease, diabetes, anemia, and osteoporosis, results from a single-center analysis showed.

“These affect the course and outcome of COPD, so identification and treatment of these comorbidities is very important,” Hamdy Mohammadien, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In an effort to estimate the presence of comorbidities in patients with COPD and to assess the relationship of comorbid diseases with age, sex, C-reactive protein, and COPD severity, Dr. Mohammadien and his associates at Sohag (Egypt) University, retrospectively evaluated 400 COPD patients who were at least 40 years of age. Those who presented with bronchial asthma or other lung diseases were excluded from the analysis. The mean age of patients was 62 years, 69% were male, and 36% were current smokers. Their mean FEV1/FVC ratio (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity) was 48%, and 57% had two or more exacerbations in the previous year.

Dr. Mohammadien reported that all patients had at least one comorbidity. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases (85%), diabetes (35%), dyslipidemia (23%), osteopenia (11%), anemia (10%), muscle wasting (9%), pneumonia (7%), osteoporosis (6%), GERD (2%), and lung cancer (2%). He also noted that the association between cardiovascular events, dyslipidemia, diabetes, osteoporosis, muscle wasting, and anemia was highly significant in COPD patients aged 60 years and older, in men, and in patients with stage III and IV COPD. In addition, a significant relationship was observed between a positive CRP level and each comorbidity, with the exception of gastroesophageal reflux disease and lung cancer. The three comorbidities with the greatest significance were ischemic heart disease (P = .0001), dyslipidemia (P = .0001), and pneumonia (P = .0003). Finally, frequent exacerbators were significantly more likely to have two or more comorbidities (odds ratio 2; P = .04) and to have more hospitalizations in the past year (P less than .01).

“Comorbidities are common in patients with COPD, and have a significant impact on health status and prognosis, thus justifying the need for a comprehensive and integrating therapeutic approach,” Dr. Mohammadien said at the meeting. “In the management of COPD all these conditions need to be carefully evaluated and treated.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that bone density was measured by sonar and not by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Dr. Mohammadien reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Comorbidities are common in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, especially cardiovascular disease, diabetes, anemia, and osteoporosis, results from a single-center analysis showed.

“These affect the course and outcome of COPD, so identification and treatment of these comorbidities is very important,” Hamdy Mohammadien, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In an effort to estimate the presence of comorbidities in patients with COPD and to assess the relationship of comorbid diseases with age, sex, C-reactive protein, and COPD severity, Dr. Mohammadien and his associates at Sohag (Egypt) University, retrospectively evaluated 400 COPD patients who were at least 40 years of age. Those who presented with bronchial asthma or other lung diseases were excluded from the analysis. The mean age of patients was 62 years, 69% were male, and 36% were current smokers. Their mean FEV1/FVC ratio (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity) was 48%, and 57% had two or more exacerbations in the previous year.

Dr. Mohammadien reported that all patients had at least one comorbidity. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases (85%), diabetes (35%), dyslipidemia (23%), osteopenia (11%), anemia (10%), muscle wasting (9%), pneumonia (7%), osteoporosis (6%), GERD (2%), and lung cancer (2%). He also noted that the association between cardiovascular events, dyslipidemia, diabetes, osteoporosis, muscle wasting, and anemia was highly significant in COPD patients aged 60 years and older, in men, and in patients with stage III and IV COPD. In addition, a significant relationship was observed between a positive CRP level and each comorbidity, with the exception of gastroesophageal reflux disease and lung cancer. The three comorbidities with the greatest significance were ischemic heart disease (P = .0001), dyslipidemia (P = .0001), and pneumonia (P = .0003). Finally, frequent exacerbators were significantly more likely to have two or more comorbidities (odds ratio 2; P = .04) and to have more hospitalizations in the past year (P less than .01).

“Comorbidities are common in patients with COPD, and have a significant impact on health status and prognosis, thus justifying the need for a comprehensive and integrating therapeutic approach,” Dr. Mohammadien said at the meeting. “In the management of COPD all these conditions need to be carefully evaluated and treated.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that bone density was measured by sonar and not by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Dr. Mohammadien reported having no financial disclosures.

AT CHEST 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The three most common comorbidities in COPD patients were cardiovascular diseases (85%), diabetes (35%), and dyslipidemia (23%).

Data source: A retrospective study of 400 patients with COPD.

Disclosures: Dr. Mohammadien reported having no financial disclosures.

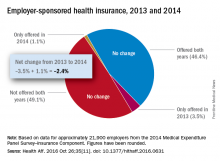

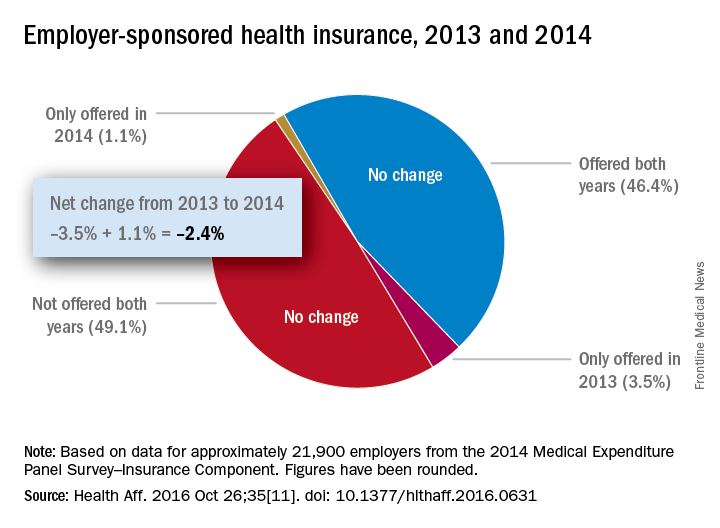

Employer-provided insurance stable after ACA implementation

Concerns that Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions implemented in 2014 would lead large numbers of employers to drop health insurance coverage appear to have been unfounded, according to a study published in the journal Health Affairs.

More than 95% of employers did not change their insurance coverage policy between 2013 and 2014: 46.4% offered coverage in 2013 and continued it in 2014 and 49.1% did not offer coverage either year. Of the 21,900 private-sector employers included in the analysis, 3.5% provided coverage in 2013 but not in 2014 and 1.1% did not offer it in 2013 but did in 2014, reported Jean Abraham, PhD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and her associates (Health Aff. 2016 Oct 26;35[11]. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0631).

The analysis of data from the 2014 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Insurance Component, however, did show associations between coverage changes and several workforce and employer characteristics. “Small firms were more likely to drop coverage compared to large ones, as were those with more low-wage workers compared to those with fewer such workers, newer establishments compared to older ones, and those in the service sector compared to those in blue- and white-collar industries,” Dr. Abraham and her associates wrote.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Access Reform Evaluation program supported the study. No other financial disclosures were provided.

Concerns that Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions implemented in 2014 would lead large numbers of employers to drop health insurance coverage appear to have been unfounded, according to a study published in the journal Health Affairs.

More than 95% of employers did not change their insurance coverage policy between 2013 and 2014: 46.4% offered coverage in 2013 and continued it in 2014 and 49.1% did not offer coverage either year. Of the 21,900 private-sector employers included in the analysis, 3.5% provided coverage in 2013 but not in 2014 and 1.1% did not offer it in 2013 but did in 2014, reported Jean Abraham, PhD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and her associates (Health Aff. 2016 Oct 26;35[11]. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0631).

The analysis of data from the 2014 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Insurance Component, however, did show associations between coverage changes and several workforce and employer characteristics. “Small firms were more likely to drop coverage compared to large ones, as were those with more low-wage workers compared to those with fewer such workers, newer establishments compared to older ones, and those in the service sector compared to those in blue- and white-collar industries,” Dr. Abraham and her associates wrote.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Access Reform Evaluation program supported the study. No other financial disclosures were provided.

Concerns that Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions implemented in 2014 would lead large numbers of employers to drop health insurance coverage appear to have been unfounded, according to a study published in the journal Health Affairs.

More than 95% of employers did not change their insurance coverage policy between 2013 and 2014: 46.4% offered coverage in 2013 and continued it in 2014 and 49.1% did not offer coverage either year. Of the 21,900 private-sector employers included in the analysis, 3.5% provided coverage in 2013 but not in 2014 and 1.1% did not offer it in 2013 but did in 2014, reported Jean Abraham, PhD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and her associates (Health Aff. 2016 Oct 26;35[11]. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0631).

The analysis of data from the 2014 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Insurance Component, however, did show associations between coverage changes and several workforce and employer characteristics. “Small firms were more likely to drop coverage compared to large ones, as were those with more low-wage workers compared to those with fewer such workers, newer establishments compared to older ones, and those in the service sector compared to those in blue- and white-collar industries,” Dr. Abraham and her associates wrote.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Access Reform Evaluation program supported the study. No other financial disclosures were provided.

7 tips for successful value-based care contracts

During a recent webinar presented by the American Bar Association, legal experts provided guidance on how doctors can successfully draft pay-for-performance contracts and prevent disputes with payers.

1. Clearly define terms

Contract terms and definitions should be clearly outlined and understood by both parties before value-based agreements are signed, said Melissa J. Hulke, a director in the Berkeley Research Group, LLC health analytics practice.

“Contract terms become central to resolving differences, so it’s important the contract is well defined, especially when moving away from fee for service,” she said. “These are more complex arrangements.”

Another area that needs thorough definition surrounds referral volume. Contracts can include the phrases, “predominately refer” or “primarily refer,” without defining the meaning of “predominately” or “primarily,” Ms. Hulke said.

“If that’s not defined in the contract, it’s hard to establish a benchmark to not only project the provider’s performance under the arrangement and how much revenue they can expect to receive, but it’s hard to know if you’re meeting that benchmark, as well,” she said. “I strongly encourage that if [a term states] “primarily, predominately, [or] mostly refer,” that you have a specific percentage benchmark included. That will help to avoid any disagreement later on.”

2. Review payment calculations

Ensure that payment formulas are examined and agreed upon.

“I think that should be baked into the contracts of today because they are so complex and there is so much money at stake,” she said. “Walk through that compensation exhibit, walk through the examples of what’s supposed to happen.

If not in agreement with calculations, talk to the payer’s financial personnel about how the numbers were reached and try to resolve any differences.

3. Monitor results

Actively monitor projected-to-actual financial performance under the contract. If performance is not being monitored and results are not being tested, it’s impossible to tell whether the contract is succeeding or failing, Ms. Hulke said.

It’s a good idea to monitor projected-to-actual financial performance monthly or at least quarterly, she advised.

“Tracking budget to actual performance and investigating successes and failures are important if the contracts are material to the provider’s business,” Ms. Hulke said.

4. Institute time frames for government methodologies

Be specific about when contracts are linked to Medicare reimbursement methodologies.

If commercial payers are tying payment rates to government programs, which often occurs, contracts should include whether the reimbursement is based on Medicare rates and methodologies as of a particular date and time, according to Ms. Hulke. For instance, the contract could specify that rates are tied to Medicare methodologies at the time the contract was executed. Alternatively, contracts could allow the physician payment rate to fluctuate depending on changes the government makes to Medicare rates and methodologies during the span of the contract.

“If this is not defined, when Medicare makes a change, the parties may have differing opinions on the appropriate rate of reimbursement that’s being paid,” she said.

5. Structure around state and federal laws

Conduct a regulatory analysis before inking any value based payment arrangement/transaction, and structure and document around potential legal constraints, Ms. Hanna said.

Know the laws in your state, she advised. Some states have requirements for provider incentive programs, while others may have rules for provider organizations or intermediaries that assume certain financial risk. When working with federal health care payers, review the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback regulations and ensure that if triggered by the arrangement, the venture falls within an exception of the statutes. Other legal considerations when drafting contracts include:

• HIPAA and state privacy laws.

• Antitrust laws.

• Telemedicine and telehealth laws.

• Medicare Advantage benefit guidelines for programs designed for specific Medicare Advantage populations.

• Scope of practice laws applicable to mid-level medical providers.

6. Design a dispute-resolution strategy

Include a thorough dispute-resolution strategy within the contract. The strategies help facilitate an orderly process for resolving disputes cost effectively, Ms. Hanna said. She suggested that policies start with an informal dispute-resolution process that sends unresolved matters to senior executives at each organization.

“This allows business leaders – and not the lawyers – to find a business solution to a thorny and potentially costly problem before each party gets entrenched in its own position and own sense of having been wronged,” she said in an interview. “The business solution may or may not rely on contract language but may be tailored to keep the relationship moving forward. However, if the informal process proves unsuccessful, then the process gets punted to the legal system – whether in a court proceeding or arbitration.”

7. Have an exit strategy

Include an exit strategy that ensures an end to the arrangement goes as smoothly and fairly as possible. The strategy will depend on the nature and structure of the payer-provider alignment and the value-based payment arrangement, Ms. Hanna said in an interview.

For example, in a true, corporate joint venture, the exit strategy may include buyout rights of the newly formed entity. In this case, it’s important to consider and negotiate the price of the buyout and what circumstances that will trigger the buyout. Termination rights should also be included in an exit strategy, Ms. Hanna said. One option is to allow termination “without case,” by either party.

“Clients often do not like this approach because the intention of the parties going in is to build a strong, long-term relationship where provider and payer benefit,” she said. “A ‘without cause’ termination rights gives the parties a safety valve if circumstances change or the relationship is just not successful.”

An alternative is to allow the relationship time to mature and grow before either party can exercise a without cause termination. A related approach is to develop triggering events that would give one or both parties the right to terminate the agreement, without the other party “having committed a bad act,” Ms. Hanna said in the interview.

“For instance, if the relationship does not meet certain financial or other benchmarks within an agreed-upon time frame, this may be a sufficient reason to terminate the relationship, abandon, or renegotiate the value-based purchasing payment formula or, perhaps, end an exclusive or other preferential relationship,” she said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

During a recent webinar presented by the American Bar Association, legal experts provided guidance on how doctors can successfully draft pay-for-performance contracts and prevent disputes with payers.

1. Clearly define terms

Contract terms and definitions should be clearly outlined and understood by both parties before value-based agreements are signed, said Melissa J. Hulke, a director in the Berkeley Research Group, LLC health analytics practice.

“Contract terms become central to resolving differences, so it’s important the contract is well defined, especially when moving away from fee for service,” she said. “These are more complex arrangements.”

Another area that needs thorough definition surrounds referral volume. Contracts can include the phrases, “predominately refer” or “primarily refer,” without defining the meaning of “predominately” or “primarily,” Ms. Hulke said.

“If that’s not defined in the contract, it’s hard to establish a benchmark to not only project the provider’s performance under the arrangement and how much revenue they can expect to receive, but it’s hard to know if you’re meeting that benchmark, as well,” she said. “I strongly encourage that if [a term states] “primarily, predominately, [or] mostly refer,” that you have a specific percentage benchmark included. That will help to avoid any disagreement later on.”

2. Review payment calculations

Ensure that payment formulas are examined and agreed upon.

“I think that should be baked into the contracts of today because they are so complex and there is so much money at stake,” she said. “Walk through that compensation exhibit, walk through the examples of what’s supposed to happen.

If not in agreement with calculations, talk to the payer’s financial personnel about how the numbers were reached and try to resolve any differences.

3. Monitor results

Actively monitor projected-to-actual financial performance under the contract. If performance is not being monitored and results are not being tested, it’s impossible to tell whether the contract is succeeding or failing, Ms. Hulke said.

It’s a good idea to monitor projected-to-actual financial performance monthly or at least quarterly, she advised.

“Tracking budget to actual performance and investigating successes and failures are important if the contracts are material to the provider’s business,” Ms. Hulke said.

4. Institute time frames for government methodologies

Be specific about when contracts are linked to Medicare reimbursement methodologies.

If commercial payers are tying payment rates to government programs, which often occurs, contracts should include whether the reimbursement is based on Medicare rates and methodologies as of a particular date and time, according to Ms. Hulke. For instance, the contract could specify that rates are tied to Medicare methodologies at the time the contract was executed. Alternatively, contracts could allow the physician payment rate to fluctuate depending on changes the government makes to Medicare rates and methodologies during the span of the contract.

“If this is not defined, when Medicare makes a change, the parties may have differing opinions on the appropriate rate of reimbursement that’s being paid,” she said.

5. Structure around state and federal laws

Conduct a regulatory analysis before inking any value based payment arrangement/transaction, and structure and document around potential legal constraints, Ms. Hanna said.

Know the laws in your state, she advised. Some states have requirements for provider incentive programs, while others may have rules for provider organizations or intermediaries that assume certain financial risk. When working with federal health care payers, review the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback regulations and ensure that if triggered by the arrangement, the venture falls within an exception of the statutes. Other legal considerations when drafting contracts include:

• HIPAA and state privacy laws.

• Antitrust laws.

• Telemedicine and telehealth laws.

• Medicare Advantage benefit guidelines for programs designed for specific Medicare Advantage populations.

• Scope of practice laws applicable to mid-level medical providers.

6. Design a dispute-resolution strategy

Include a thorough dispute-resolution strategy within the contract. The strategies help facilitate an orderly process for resolving disputes cost effectively, Ms. Hanna said. She suggested that policies start with an informal dispute-resolution process that sends unresolved matters to senior executives at each organization.

“This allows business leaders – and not the lawyers – to find a business solution to a thorny and potentially costly problem before each party gets entrenched in its own position and own sense of having been wronged,” she said in an interview. “The business solution may or may not rely on contract language but may be tailored to keep the relationship moving forward. However, if the informal process proves unsuccessful, then the process gets punted to the legal system – whether in a court proceeding or arbitration.”

7. Have an exit strategy

Include an exit strategy that ensures an end to the arrangement goes as smoothly and fairly as possible. The strategy will depend on the nature and structure of the payer-provider alignment and the value-based payment arrangement, Ms. Hanna said in an interview.

For example, in a true, corporate joint venture, the exit strategy may include buyout rights of the newly formed entity. In this case, it’s important to consider and negotiate the price of the buyout and what circumstances that will trigger the buyout. Termination rights should also be included in an exit strategy, Ms. Hanna said. One option is to allow termination “without case,” by either party.

“Clients often do not like this approach because the intention of the parties going in is to build a strong, long-term relationship where provider and payer benefit,” she said. “A ‘without cause’ termination rights gives the parties a safety valve if circumstances change or the relationship is just not successful.”

An alternative is to allow the relationship time to mature and grow before either party can exercise a without cause termination. A related approach is to develop triggering events that would give one or both parties the right to terminate the agreement, without the other party “having committed a bad act,” Ms. Hanna said in the interview.

“For instance, if the relationship does not meet certain financial or other benchmarks within an agreed-upon time frame, this may be a sufficient reason to terminate the relationship, abandon, or renegotiate the value-based purchasing payment formula or, perhaps, end an exclusive or other preferential relationship,” she said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

During a recent webinar presented by the American Bar Association, legal experts provided guidance on how doctors can successfully draft pay-for-performance contracts and prevent disputes with payers.

1. Clearly define terms

Contract terms and definitions should be clearly outlined and understood by both parties before value-based agreements are signed, said Melissa J. Hulke, a director in the Berkeley Research Group, LLC health analytics practice.

“Contract terms become central to resolving differences, so it’s important the contract is well defined, especially when moving away from fee for service,” she said. “These are more complex arrangements.”

Another area that needs thorough definition surrounds referral volume. Contracts can include the phrases, “predominately refer” or “primarily refer,” without defining the meaning of “predominately” or “primarily,” Ms. Hulke said.

“If that’s not defined in the contract, it’s hard to establish a benchmark to not only project the provider’s performance under the arrangement and how much revenue they can expect to receive, but it’s hard to know if you’re meeting that benchmark, as well,” she said. “I strongly encourage that if [a term states] “primarily, predominately, [or] mostly refer,” that you have a specific percentage benchmark included. That will help to avoid any disagreement later on.”

2. Review payment calculations

Ensure that payment formulas are examined and agreed upon.

“I think that should be baked into the contracts of today because they are so complex and there is so much money at stake,” she said. “Walk through that compensation exhibit, walk through the examples of what’s supposed to happen.

If not in agreement with calculations, talk to the payer’s financial personnel about how the numbers were reached and try to resolve any differences.

3. Monitor results

Actively monitor projected-to-actual financial performance under the contract. If performance is not being monitored and results are not being tested, it’s impossible to tell whether the contract is succeeding or failing, Ms. Hulke said.

It’s a good idea to monitor projected-to-actual financial performance monthly or at least quarterly, she advised.

“Tracking budget to actual performance and investigating successes and failures are important if the contracts are material to the provider’s business,” Ms. Hulke said.

4. Institute time frames for government methodologies

Be specific about when contracts are linked to Medicare reimbursement methodologies.

If commercial payers are tying payment rates to government programs, which often occurs, contracts should include whether the reimbursement is based on Medicare rates and methodologies as of a particular date and time, according to Ms. Hulke. For instance, the contract could specify that rates are tied to Medicare methodologies at the time the contract was executed. Alternatively, contracts could allow the physician payment rate to fluctuate depending on changes the government makes to Medicare rates and methodologies during the span of the contract.

“If this is not defined, when Medicare makes a change, the parties may have differing opinions on the appropriate rate of reimbursement that’s being paid,” she said.

5. Structure around state and federal laws

Conduct a regulatory analysis before inking any value based payment arrangement/transaction, and structure and document around potential legal constraints, Ms. Hanna said.

Know the laws in your state, she advised. Some states have requirements for provider incentive programs, while others may have rules for provider organizations or intermediaries that assume certain financial risk. When working with federal health care payers, review the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback regulations and ensure that if triggered by the arrangement, the venture falls within an exception of the statutes. Other legal considerations when drafting contracts include:

• HIPAA and state privacy laws.

• Antitrust laws.

• Telemedicine and telehealth laws.

• Medicare Advantage benefit guidelines for programs designed for specific Medicare Advantage populations.

• Scope of practice laws applicable to mid-level medical providers.

6. Design a dispute-resolution strategy

Include a thorough dispute-resolution strategy within the contract. The strategies help facilitate an orderly process for resolving disputes cost effectively, Ms. Hanna said. She suggested that policies start with an informal dispute-resolution process that sends unresolved matters to senior executives at each organization.

“This allows business leaders – and not the lawyers – to find a business solution to a thorny and potentially costly problem before each party gets entrenched in its own position and own sense of having been wronged,” she said in an interview. “The business solution may or may not rely on contract language but may be tailored to keep the relationship moving forward. However, if the informal process proves unsuccessful, then the process gets punted to the legal system – whether in a court proceeding or arbitration.”

7. Have an exit strategy

Include an exit strategy that ensures an end to the arrangement goes as smoothly and fairly as possible. The strategy will depend on the nature and structure of the payer-provider alignment and the value-based payment arrangement, Ms. Hanna said in an interview.

For example, in a true, corporate joint venture, the exit strategy may include buyout rights of the newly formed entity. In this case, it’s important to consider and negotiate the price of the buyout and what circumstances that will trigger the buyout. Termination rights should also be included in an exit strategy, Ms. Hanna said. One option is to allow termination “without case,” by either party.

“Clients often do not like this approach because the intention of the parties going in is to build a strong, long-term relationship where provider and payer benefit,” she said. “A ‘without cause’ termination rights gives the parties a safety valve if circumstances change or the relationship is just not successful.”

An alternative is to allow the relationship time to mature and grow before either party can exercise a without cause termination. A related approach is to develop triggering events that would give one or both parties the right to terminate the agreement, without the other party “having committed a bad act,” Ms. Hanna said in the interview.

“For instance, if the relationship does not meet certain financial or other benchmarks within an agreed-upon time frame, this may be a sufficient reason to terminate the relationship, abandon, or renegotiate the value-based purchasing payment formula or, perhaps, end an exclusive or other preferential relationship,” she said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Optimal management of GERD in IPF unknown

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CHEST 2016

LOS ANGELES – The optimal management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis has yet to be determined, according to Joyce S. Lee, MD.

“We need strong randomized clinical trial data to tell us whether or not medical or surgical treatment of GERD in IPF is indicated,” she said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.