User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Not so crazy: Pancreas transplants in type 2 diabetes rising

Simultaneous

Traditionally, recipients of pancreas transplants have been people with type 1 diabetes who also have either chronic kidney disease (CKD) or hypoglycemic unawareness. The former group could receive either a simultaneous pancreas-kidney or a pancreas after kidney transplant, while the latter – if they have normal kidney function – would be eligible for a pancreas transplant alone.

But increasingly in recent years, patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD have been receiving simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants, with similar success rates to those of people with type 1 diabetes.

Such candidates are typically sufficiently fit, not morbidly obese, and taking insulin regardless of their C-peptide status, said Jon S. Odorico, MD, professor of surgery and director of pancreas and islet transplantation at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Transplant Program.

“One might ask: Is it a crazy idea to do a pancreas transplant for patients with type 2 diabetes? Based on the known mechanisms of hyperglycemia in these patients, it might seem so,” he said, noting that while individuals with type 2 diabetes usually have insulin resistance, many also have relative or absolute deficiency of insulin production.

“So by replacing beta-cell mass, pancreas transplantation addresses this beta-cell defect mechanism,” he explained when discussing the topic during a symposium held June 26 at the virtual American Diabetes Association (ADA) 81st Scientific Sessions.

Arguments in favor of simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant in people with type 2 diabetes and CKD include the fact that type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of kidney disease in the United States – roughly 50-60% of candidates on the kidney transplant waiting list also have type 2 diabetes – and that kidney transplant alone tends to worsen diabetes control due to the required immunosuppression.

Moreover, due to a 2014 allocation policy change that separates simultaneous pancreas-kidney from kidney transplant–alone donor organs, waiting times are shorter for the former, and kidney quality is generally better than for kidney transplant alone, unless a living kidney donor is available.

And, Dr. Odorico added, “adding a pancreas to a kidney transplant does not appear to jeopardize patient survival or kidney graft survival in appropriately selected patients with diabetes.” However, he also noted that because type 2 diabetes is so heterogeneous, ideal candidates for simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant are not yet clear.

Currently, people with type 2 diabetes account for about 20% of those receiving simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants and about 50% of pancreas after kidney transplants. Few pancreas transplants alone are performed in type 2 diabetes because those individuals rarely experience severe life-threatening hypoglycemia, Dr. Odorico explained.

Criteria have shifted over time, C-peptide removed in 2019

In an interview, symposium moderator Peter G. Stock, MD, PhD, surgical director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Program at the University of California, San Francisco, said he agreed that “it’s a surprising trend. It doesn’t make intuitive sense. In type 1 diabetes, it makes sense to replace the beta cells. But type 2 is due to a whole cluster of etiologies ... The view in the public domain is that it’s not due to the lack of insulin but problems with insulin resistance and obesity. So it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to give you more insulin if it’s a receptor problem.”

But Dr. Stock noted that because in the past diabetes type wasn’t always rigorously assessed using C-peptide and antibody testing, which most centers measure today, “a number of transplants were done in people who turned out to have type 2. Our perception is that everybody who has type 2 is obese, but that’s not true anymore.”

Once it became apparent that some patients with type 2 diabetes who received pancreas transplants seemed to be doing well, the pancreas transplantation committee of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) established general criteria for the procedure in people with diabetes. They had to be taking insulin and have a C-peptide value of 2 ng/mL or below or taking insulin with a C-peptide greater than 2 ng/mL and a body mass index less than or equal to the maximum allowable BMI (28 kg/m2 at the time).

Dr. Stock, who chaired that committee from 2005 to 2007, said: “We thought it was risky to offer a scarce pool of donor pancreases to people with type 2 when we had people with type 1 who we know will benefit from it. So initially, the committee decided to limit pancreas transplantation to those with type 2 who have fairly low insulin requirements and BMIs that are more in the range of people with type 1. And lo and behold the results were comparable.”

Subsequent to Dr. Stock’s tenure as chair, the UNOS committee decided that the BMI and C-peptide criteria for simultaneous pancreas-kidney were no longer scientifically justifiable and were potentially discriminatory both to minority populations with type 2 diabetes and people with type 1 diabetes who have a high BMI, so in 2019, they removed them.

Individual transplant centers must follow UNOS rules, but they can also add their own criteria. Some don’t perform simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants in people with type 2 diabetes at all.

At Dr. Odorico’s center, which began doing so in 2012, patients with type 2 diabetes account for nearly 40% of all simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants. Indications there include age 20-60 years, insulin dependent with requirements less than 1 unit/kg/day, CKD stage 3-5, predialysis or on dialysis, and BMI <33 kg/m2.

“They are highly selected and a fairly fit group of patients,” Dr. Odorico noted.

Those who don’t meet all the requirements for simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants may still be eligible for kidney transplant alone, from either a living or deceased donor, he said.

Dr. Stock’s criteria at UCSF are even more stringent for both BMI and insulin requirements.

SPK outcomes similar for type 1 and type 2 diabetes: Emerging data

Data to guide this area are accumulating slowly. Thus far, all studies have been retrospective and have used variable definitions for diabetes type and for graft failure. However, they’re fairly consistent in showing similar outcomes by diabetes type and little impact of C-peptide level on patient survival or survival of either kidney or pancreas graft, particularly after adjustment for confounding factors between the two types.

In a study from Dr. Odorico’s center of 284 type 1 and 39 type 2 diabetes patients undergoing simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant between 2006 and 2017, pretransplant BMI and insulin requirements did not affect patient or graft survival in either type. There was a suggestion of greater risk for post-transplant diabetes with very high pretransplant insulin requirements (>75 units/day) but the numbers were too small to be definitive.

“It’s clear we will be doing more pancreas transplants in the future in this group of patients, and it’s ripe for further investigation,” Dr. Odorico concluded.

Beta cells for all?

Dr. Stock added one more aspect. While of course whole-organ transplantation is limited by the shortage of human donors, stem cell–derived beta cells could potentially produce an unlimited supply. Both Dr. Stock and Dr. Odorico are working on different approaches to this.

“We’re really close,” he said, noting, “the data we get for people with type 2 diabetes undergoing solid organ pancreas transplant could also be applied to cellular therapy ... We need to get a better understanding of which patients will benefit. The data we have so far are very promising.”

Dr. Odorico is scientific founder, stock equity holder, scientific advisory board chair, and a prior grant support recipient from Regenerative Medical Solutions. He has reported receiving clinical trial support from Veloxis Pharmaceuticals, CareDx, Natera, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Stock has reported being on the scientific advisory board of Encellin and receives funding from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine and National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Simultaneous

Traditionally, recipients of pancreas transplants have been people with type 1 diabetes who also have either chronic kidney disease (CKD) or hypoglycemic unawareness. The former group could receive either a simultaneous pancreas-kidney or a pancreas after kidney transplant, while the latter – if they have normal kidney function – would be eligible for a pancreas transplant alone.

But increasingly in recent years, patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD have been receiving simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants, with similar success rates to those of people with type 1 diabetes.

Such candidates are typically sufficiently fit, not morbidly obese, and taking insulin regardless of their C-peptide status, said Jon S. Odorico, MD, professor of surgery and director of pancreas and islet transplantation at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Transplant Program.

“One might ask: Is it a crazy idea to do a pancreas transplant for patients with type 2 diabetes? Based on the known mechanisms of hyperglycemia in these patients, it might seem so,” he said, noting that while individuals with type 2 diabetes usually have insulin resistance, many also have relative or absolute deficiency of insulin production.

“So by replacing beta-cell mass, pancreas transplantation addresses this beta-cell defect mechanism,” he explained when discussing the topic during a symposium held June 26 at the virtual American Diabetes Association (ADA) 81st Scientific Sessions.

Arguments in favor of simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant in people with type 2 diabetes and CKD include the fact that type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of kidney disease in the United States – roughly 50-60% of candidates on the kidney transplant waiting list also have type 2 diabetes – and that kidney transplant alone tends to worsen diabetes control due to the required immunosuppression.

Moreover, due to a 2014 allocation policy change that separates simultaneous pancreas-kidney from kidney transplant–alone donor organs, waiting times are shorter for the former, and kidney quality is generally better than for kidney transplant alone, unless a living kidney donor is available.

And, Dr. Odorico added, “adding a pancreas to a kidney transplant does not appear to jeopardize patient survival or kidney graft survival in appropriately selected patients with diabetes.” However, he also noted that because type 2 diabetes is so heterogeneous, ideal candidates for simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant are not yet clear.

Currently, people with type 2 diabetes account for about 20% of those receiving simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants and about 50% of pancreas after kidney transplants. Few pancreas transplants alone are performed in type 2 diabetes because those individuals rarely experience severe life-threatening hypoglycemia, Dr. Odorico explained.

Criteria have shifted over time, C-peptide removed in 2019

In an interview, symposium moderator Peter G. Stock, MD, PhD, surgical director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Program at the University of California, San Francisco, said he agreed that “it’s a surprising trend. It doesn’t make intuitive sense. In type 1 diabetes, it makes sense to replace the beta cells. But type 2 is due to a whole cluster of etiologies ... The view in the public domain is that it’s not due to the lack of insulin but problems with insulin resistance and obesity. So it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to give you more insulin if it’s a receptor problem.”

But Dr. Stock noted that because in the past diabetes type wasn’t always rigorously assessed using C-peptide and antibody testing, which most centers measure today, “a number of transplants were done in people who turned out to have type 2. Our perception is that everybody who has type 2 is obese, but that’s not true anymore.”

Once it became apparent that some patients with type 2 diabetes who received pancreas transplants seemed to be doing well, the pancreas transplantation committee of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) established general criteria for the procedure in people with diabetes. They had to be taking insulin and have a C-peptide value of 2 ng/mL or below or taking insulin with a C-peptide greater than 2 ng/mL and a body mass index less than or equal to the maximum allowable BMI (28 kg/m2 at the time).

Dr. Stock, who chaired that committee from 2005 to 2007, said: “We thought it was risky to offer a scarce pool of donor pancreases to people with type 2 when we had people with type 1 who we know will benefit from it. So initially, the committee decided to limit pancreas transplantation to those with type 2 who have fairly low insulin requirements and BMIs that are more in the range of people with type 1. And lo and behold the results were comparable.”

Subsequent to Dr. Stock’s tenure as chair, the UNOS committee decided that the BMI and C-peptide criteria for simultaneous pancreas-kidney were no longer scientifically justifiable and were potentially discriminatory both to minority populations with type 2 diabetes and people with type 1 diabetes who have a high BMI, so in 2019, they removed them.

Individual transplant centers must follow UNOS rules, but they can also add their own criteria. Some don’t perform simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants in people with type 2 diabetes at all.

At Dr. Odorico’s center, which began doing so in 2012, patients with type 2 diabetes account for nearly 40% of all simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants. Indications there include age 20-60 years, insulin dependent with requirements less than 1 unit/kg/day, CKD stage 3-5, predialysis or on dialysis, and BMI <33 kg/m2.

“They are highly selected and a fairly fit group of patients,” Dr. Odorico noted.

Those who don’t meet all the requirements for simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants may still be eligible for kidney transplant alone, from either a living or deceased donor, he said.

Dr. Stock’s criteria at UCSF are even more stringent for both BMI and insulin requirements.

SPK outcomes similar for type 1 and type 2 diabetes: Emerging data

Data to guide this area are accumulating slowly. Thus far, all studies have been retrospective and have used variable definitions for diabetes type and for graft failure. However, they’re fairly consistent in showing similar outcomes by diabetes type and little impact of C-peptide level on patient survival or survival of either kidney or pancreas graft, particularly after adjustment for confounding factors between the two types.

In a study from Dr. Odorico’s center of 284 type 1 and 39 type 2 diabetes patients undergoing simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant between 2006 and 2017, pretransplant BMI and insulin requirements did not affect patient or graft survival in either type. There was a suggestion of greater risk for post-transplant diabetes with very high pretransplant insulin requirements (>75 units/day) but the numbers were too small to be definitive.

“It’s clear we will be doing more pancreas transplants in the future in this group of patients, and it’s ripe for further investigation,” Dr. Odorico concluded.

Beta cells for all?

Dr. Stock added one more aspect. While of course whole-organ transplantation is limited by the shortage of human donors, stem cell–derived beta cells could potentially produce an unlimited supply. Both Dr. Stock and Dr. Odorico are working on different approaches to this.

“We’re really close,” he said, noting, “the data we get for people with type 2 diabetes undergoing solid organ pancreas transplant could also be applied to cellular therapy ... We need to get a better understanding of which patients will benefit. The data we have so far are very promising.”

Dr. Odorico is scientific founder, stock equity holder, scientific advisory board chair, and a prior grant support recipient from Regenerative Medical Solutions. He has reported receiving clinical trial support from Veloxis Pharmaceuticals, CareDx, Natera, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Stock has reported being on the scientific advisory board of Encellin and receives funding from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine and National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Simultaneous

Traditionally, recipients of pancreas transplants have been people with type 1 diabetes who also have either chronic kidney disease (CKD) or hypoglycemic unawareness. The former group could receive either a simultaneous pancreas-kidney or a pancreas after kidney transplant, while the latter – if they have normal kidney function – would be eligible for a pancreas transplant alone.

But increasingly in recent years, patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD have been receiving simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants, with similar success rates to those of people with type 1 diabetes.

Such candidates are typically sufficiently fit, not morbidly obese, and taking insulin regardless of their C-peptide status, said Jon S. Odorico, MD, professor of surgery and director of pancreas and islet transplantation at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Transplant Program.

“One might ask: Is it a crazy idea to do a pancreas transplant for patients with type 2 diabetes? Based on the known mechanisms of hyperglycemia in these patients, it might seem so,” he said, noting that while individuals with type 2 diabetes usually have insulin resistance, many also have relative or absolute deficiency of insulin production.

“So by replacing beta-cell mass, pancreas transplantation addresses this beta-cell defect mechanism,” he explained when discussing the topic during a symposium held June 26 at the virtual American Diabetes Association (ADA) 81st Scientific Sessions.

Arguments in favor of simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant in people with type 2 diabetes and CKD include the fact that type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of kidney disease in the United States – roughly 50-60% of candidates on the kidney transplant waiting list also have type 2 diabetes – and that kidney transplant alone tends to worsen diabetes control due to the required immunosuppression.

Moreover, due to a 2014 allocation policy change that separates simultaneous pancreas-kidney from kidney transplant–alone donor organs, waiting times are shorter for the former, and kidney quality is generally better than for kidney transplant alone, unless a living kidney donor is available.

And, Dr. Odorico added, “adding a pancreas to a kidney transplant does not appear to jeopardize patient survival or kidney graft survival in appropriately selected patients with diabetes.” However, he also noted that because type 2 diabetes is so heterogeneous, ideal candidates for simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant are not yet clear.

Currently, people with type 2 diabetes account for about 20% of those receiving simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants and about 50% of pancreas after kidney transplants. Few pancreas transplants alone are performed in type 2 diabetes because those individuals rarely experience severe life-threatening hypoglycemia, Dr. Odorico explained.

Criteria have shifted over time, C-peptide removed in 2019

In an interview, symposium moderator Peter G. Stock, MD, PhD, surgical director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Program at the University of California, San Francisco, said he agreed that “it’s a surprising trend. It doesn’t make intuitive sense. In type 1 diabetes, it makes sense to replace the beta cells. But type 2 is due to a whole cluster of etiologies ... The view in the public domain is that it’s not due to the lack of insulin but problems with insulin resistance and obesity. So it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to give you more insulin if it’s a receptor problem.”

But Dr. Stock noted that because in the past diabetes type wasn’t always rigorously assessed using C-peptide and antibody testing, which most centers measure today, “a number of transplants were done in people who turned out to have type 2. Our perception is that everybody who has type 2 is obese, but that’s not true anymore.”

Once it became apparent that some patients with type 2 diabetes who received pancreas transplants seemed to be doing well, the pancreas transplantation committee of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) established general criteria for the procedure in people with diabetes. They had to be taking insulin and have a C-peptide value of 2 ng/mL or below or taking insulin with a C-peptide greater than 2 ng/mL and a body mass index less than or equal to the maximum allowable BMI (28 kg/m2 at the time).

Dr. Stock, who chaired that committee from 2005 to 2007, said: “We thought it was risky to offer a scarce pool of donor pancreases to people with type 2 when we had people with type 1 who we know will benefit from it. So initially, the committee decided to limit pancreas transplantation to those with type 2 who have fairly low insulin requirements and BMIs that are more in the range of people with type 1. And lo and behold the results were comparable.”

Subsequent to Dr. Stock’s tenure as chair, the UNOS committee decided that the BMI and C-peptide criteria for simultaneous pancreas-kidney were no longer scientifically justifiable and were potentially discriminatory both to minority populations with type 2 diabetes and people with type 1 diabetes who have a high BMI, so in 2019, they removed them.

Individual transplant centers must follow UNOS rules, but they can also add their own criteria. Some don’t perform simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants in people with type 2 diabetes at all.

At Dr. Odorico’s center, which began doing so in 2012, patients with type 2 diabetes account for nearly 40% of all simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants. Indications there include age 20-60 years, insulin dependent with requirements less than 1 unit/kg/day, CKD stage 3-5, predialysis or on dialysis, and BMI <33 kg/m2.

“They are highly selected and a fairly fit group of patients,” Dr. Odorico noted.

Those who don’t meet all the requirements for simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants may still be eligible for kidney transplant alone, from either a living or deceased donor, he said.

Dr. Stock’s criteria at UCSF are even more stringent for both BMI and insulin requirements.

SPK outcomes similar for type 1 and type 2 diabetes: Emerging data

Data to guide this area are accumulating slowly. Thus far, all studies have been retrospective and have used variable definitions for diabetes type and for graft failure. However, they’re fairly consistent in showing similar outcomes by diabetes type and little impact of C-peptide level on patient survival or survival of either kidney or pancreas graft, particularly after adjustment for confounding factors between the two types.

In a study from Dr. Odorico’s center of 284 type 1 and 39 type 2 diabetes patients undergoing simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant between 2006 and 2017, pretransplant BMI and insulin requirements did not affect patient or graft survival in either type. There was a suggestion of greater risk for post-transplant diabetes with very high pretransplant insulin requirements (>75 units/day) but the numbers were too small to be definitive.

“It’s clear we will be doing more pancreas transplants in the future in this group of patients, and it’s ripe for further investigation,” Dr. Odorico concluded.

Beta cells for all?

Dr. Stock added one more aspect. While of course whole-organ transplantation is limited by the shortage of human donors, stem cell–derived beta cells could potentially produce an unlimited supply. Both Dr. Stock and Dr. Odorico are working on different approaches to this.

“We’re really close,” he said, noting, “the data we get for people with type 2 diabetes undergoing solid organ pancreas transplant could also be applied to cellular therapy ... We need to get a better understanding of which patients will benefit. The data we have so far are very promising.”

Dr. Odorico is scientific founder, stock equity holder, scientific advisory board chair, and a prior grant support recipient from Regenerative Medical Solutions. He has reported receiving clinical trial support from Veloxis Pharmaceuticals, CareDx, Natera, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Stock has reported being on the scientific advisory board of Encellin and receives funding from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine and National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Limited English proficiency linked with less health care in U.S.

Jessica Himmelstein, MD, a Harvard research fellow and primary care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass., led a study of more than 120,000 adults published July 6, 2021. The study population included 17,776 Hispanic adults with limited English proficiency, 14,936 Hispanic adults proficient in English and 87,834 non-Hispanic, English-proficient adults.

Researchers compared several measures of care usage from information in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 1998 to 2018.

They found that, in adjusted analyses, total use of care per capita from 2014-2018, measured by health care expenditures, was $1,463 lower (98% confidence interval, $1,030-$1,897), or 35% lower for primary-Spanish speakers than for Hispanic adults who were English proficient and $2,802 lower (98% CI, $2,356-$3,247), or 42% lower versus non-Hispanic adults who were English proficient.

Spanish speakers also had 36% fewer outpatient visits and 48% fewer prescription medications than non-Hispanic adults, and 35% fewer outpatient visits and 37% fewer prescription medications than English-proficient Hispanic adults.

Even when accounting for differences in health, age, sex, income and insurance, adults with language barriers fared worse.

Gaps span all types of care

The services that those with limited English skills are missing are “the types of care people need to lead a healthy life,” from routine visits and medications to urgent or emergency care, Dr. Himmelstein said in an interview.

She said the gaps were greater in outpatient care and in medication use, compared with emergency department visits and inpatient care, but the inequities were present in all the categories she and her coinvestigators studied.

Underlying causes for having less care may include that people who struggle with English may not feel comfortable accessing the health system or may feel unwelcome or discriminated against.

“An undercurrent of biases, including racism, could also be contributing,” she said.

The data show that, despite several federal policy changes aimed at promoting language services in hospitals and clinics, several language-based disparities have not improved over 2 decades.

Some of the changes have included an executive order in 2000 requiring interpreters to be available in federally funded health facilities. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act enhanced the definition of meaningful access to language services and setting standards for qualified interpreters.

Gap widened over 2 decades

The adjusted gap in annual health care expenditures per capita between adults with limited English skills and non-Hispanic, English-proficient adults widened by $1,596 (98% CI, $837-$2,356) between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, after accounting for inflation.

Dr. Himmelstein said that though this study period predated COVID-19, its findings may help explain the disproportionate burden the pandemic placed on the Hispanic population.

“This is a community that traditionally wasn’t getting access to care and then suddenly something like COVID-19 comes and they were even more devastated,” she noted.

Telehealth, which proved an important way to access care during the pandemic, also added a degree of communication difficulty for those with fewer English skills, she said.

Many of the telehealth changes are here to stay, and it will be important to ask: “Are we ensuring equity in telehealth use for individuals who face language barriers?” Dr. Himmelstein said.

Olga Garcia-Bedoya, MD, an associate professor at University of Illinois at Chicago’s department of medicine and medical director of UIC’s Institute for Minority Health Research, said having access to interpreters with high accuracy is key to narrowing the gaps.

“The literature is very clear that access to professional medical interpreters is associated with decreased health disparities for patients with limited English proficiency,” she said.

More cultural training for clinicians is needed surrounding beliefs about illness and that some care may be declined not because of a person’s limited English proficiency, but because their beliefs may keep them from getting care, Dr. Garcia-Bedoya added. When it comes to getting a flu shot, for example, sometimes belief systems, rather than English proficiency, keep people from accessing care.

What can be done?

Addressing barriers caused by lack of English proficiency will likely take change in policies, including one related reimbursement for medical interpreters, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Currently, only 15 states’ Medicaid programs or Children’s Health Insurance Programs reimburse providers for language services, the paper notes, and neither Medicare nor private insurers routinely pay for those services.

Recruiting bilingual providers and staff at health care facilities and in medical and nursing schools will also be important to narrow the gaps, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Strengthening standards for interpreters also will help. “Currently such standards vary by state or by institution and are not necessarily enforced,” she explained.

It will also be important to make sure patients know that they are entitled by law to care, free of discriminatory practices and to have certain language services including qualified interpreters, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Dr. Garcia-Bedoya said changes need to come from health systems working in combination with clinicians, providing resources so that quality interpreters can be accessed and making sure that equipment supports clear communication in telehealth. Patients’ language preferences should also be noted as soon as they make the appointment.

The findings of the study may have large significance as one in seven people in the United States speak Spanish at home, and 25 million people in the United States have limited English proficiency, the authors noted.

Dr. Himmelstein receives funding support from an Institutional National Research Service Award. Dr. Garcia-Bedoya reports no relevant financial relationships.

Jessica Himmelstein, MD, a Harvard research fellow and primary care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass., led a study of more than 120,000 adults published July 6, 2021. The study population included 17,776 Hispanic adults with limited English proficiency, 14,936 Hispanic adults proficient in English and 87,834 non-Hispanic, English-proficient adults.

Researchers compared several measures of care usage from information in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 1998 to 2018.

They found that, in adjusted analyses, total use of care per capita from 2014-2018, measured by health care expenditures, was $1,463 lower (98% confidence interval, $1,030-$1,897), or 35% lower for primary-Spanish speakers than for Hispanic adults who were English proficient and $2,802 lower (98% CI, $2,356-$3,247), or 42% lower versus non-Hispanic adults who were English proficient.

Spanish speakers also had 36% fewer outpatient visits and 48% fewer prescription medications than non-Hispanic adults, and 35% fewer outpatient visits and 37% fewer prescription medications than English-proficient Hispanic adults.

Even when accounting for differences in health, age, sex, income and insurance, adults with language barriers fared worse.

Gaps span all types of care

The services that those with limited English skills are missing are “the types of care people need to lead a healthy life,” from routine visits and medications to urgent or emergency care, Dr. Himmelstein said in an interview.

She said the gaps were greater in outpatient care and in medication use, compared with emergency department visits and inpatient care, but the inequities were present in all the categories she and her coinvestigators studied.

Underlying causes for having less care may include that people who struggle with English may not feel comfortable accessing the health system or may feel unwelcome or discriminated against.

“An undercurrent of biases, including racism, could also be contributing,” she said.

The data show that, despite several federal policy changes aimed at promoting language services in hospitals and clinics, several language-based disparities have not improved over 2 decades.

Some of the changes have included an executive order in 2000 requiring interpreters to be available in federally funded health facilities. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act enhanced the definition of meaningful access to language services and setting standards for qualified interpreters.

Gap widened over 2 decades

The adjusted gap in annual health care expenditures per capita between adults with limited English skills and non-Hispanic, English-proficient adults widened by $1,596 (98% CI, $837-$2,356) between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, after accounting for inflation.

Dr. Himmelstein said that though this study period predated COVID-19, its findings may help explain the disproportionate burden the pandemic placed on the Hispanic population.

“This is a community that traditionally wasn’t getting access to care and then suddenly something like COVID-19 comes and they were even more devastated,” she noted.

Telehealth, which proved an important way to access care during the pandemic, also added a degree of communication difficulty for those with fewer English skills, she said.

Many of the telehealth changes are here to stay, and it will be important to ask: “Are we ensuring equity in telehealth use for individuals who face language barriers?” Dr. Himmelstein said.

Olga Garcia-Bedoya, MD, an associate professor at University of Illinois at Chicago’s department of medicine and medical director of UIC’s Institute for Minority Health Research, said having access to interpreters with high accuracy is key to narrowing the gaps.

“The literature is very clear that access to professional medical interpreters is associated with decreased health disparities for patients with limited English proficiency,” she said.

More cultural training for clinicians is needed surrounding beliefs about illness and that some care may be declined not because of a person’s limited English proficiency, but because their beliefs may keep them from getting care, Dr. Garcia-Bedoya added. When it comes to getting a flu shot, for example, sometimes belief systems, rather than English proficiency, keep people from accessing care.

What can be done?

Addressing barriers caused by lack of English proficiency will likely take change in policies, including one related reimbursement for medical interpreters, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Currently, only 15 states’ Medicaid programs or Children’s Health Insurance Programs reimburse providers for language services, the paper notes, and neither Medicare nor private insurers routinely pay for those services.

Recruiting bilingual providers and staff at health care facilities and in medical and nursing schools will also be important to narrow the gaps, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Strengthening standards for interpreters also will help. “Currently such standards vary by state or by institution and are not necessarily enforced,” she explained.

It will also be important to make sure patients know that they are entitled by law to care, free of discriminatory practices and to have certain language services including qualified interpreters, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Dr. Garcia-Bedoya said changes need to come from health systems working in combination with clinicians, providing resources so that quality interpreters can be accessed and making sure that equipment supports clear communication in telehealth. Patients’ language preferences should also be noted as soon as they make the appointment.

The findings of the study may have large significance as one in seven people in the United States speak Spanish at home, and 25 million people in the United States have limited English proficiency, the authors noted.

Dr. Himmelstein receives funding support from an Institutional National Research Service Award. Dr. Garcia-Bedoya reports no relevant financial relationships.

Jessica Himmelstein, MD, a Harvard research fellow and primary care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass., led a study of more than 120,000 adults published July 6, 2021. The study population included 17,776 Hispanic adults with limited English proficiency, 14,936 Hispanic adults proficient in English and 87,834 non-Hispanic, English-proficient adults.

Researchers compared several measures of care usage from information in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 1998 to 2018.

They found that, in adjusted analyses, total use of care per capita from 2014-2018, measured by health care expenditures, was $1,463 lower (98% confidence interval, $1,030-$1,897), or 35% lower for primary-Spanish speakers than for Hispanic adults who were English proficient and $2,802 lower (98% CI, $2,356-$3,247), or 42% lower versus non-Hispanic adults who were English proficient.

Spanish speakers also had 36% fewer outpatient visits and 48% fewer prescription medications than non-Hispanic adults, and 35% fewer outpatient visits and 37% fewer prescription medications than English-proficient Hispanic adults.

Even when accounting for differences in health, age, sex, income and insurance, adults with language barriers fared worse.

Gaps span all types of care

The services that those with limited English skills are missing are “the types of care people need to lead a healthy life,” from routine visits and medications to urgent or emergency care, Dr. Himmelstein said in an interview.

She said the gaps were greater in outpatient care and in medication use, compared with emergency department visits and inpatient care, but the inequities were present in all the categories she and her coinvestigators studied.

Underlying causes for having less care may include that people who struggle with English may not feel comfortable accessing the health system or may feel unwelcome or discriminated against.

“An undercurrent of biases, including racism, could also be contributing,” she said.

The data show that, despite several federal policy changes aimed at promoting language services in hospitals and clinics, several language-based disparities have not improved over 2 decades.

Some of the changes have included an executive order in 2000 requiring interpreters to be available in federally funded health facilities. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act enhanced the definition of meaningful access to language services and setting standards for qualified interpreters.

Gap widened over 2 decades

The adjusted gap in annual health care expenditures per capita between adults with limited English skills and non-Hispanic, English-proficient adults widened by $1,596 (98% CI, $837-$2,356) between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, after accounting for inflation.

Dr. Himmelstein said that though this study period predated COVID-19, its findings may help explain the disproportionate burden the pandemic placed on the Hispanic population.

“This is a community that traditionally wasn’t getting access to care and then suddenly something like COVID-19 comes and they were even more devastated,” she noted.

Telehealth, which proved an important way to access care during the pandemic, also added a degree of communication difficulty for those with fewer English skills, she said.

Many of the telehealth changes are here to stay, and it will be important to ask: “Are we ensuring equity in telehealth use for individuals who face language barriers?” Dr. Himmelstein said.

Olga Garcia-Bedoya, MD, an associate professor at University of Illinois at Chicago’s department of medicine and medical director of UIC’s Institute for Minority Health Research, said having access to interpreters with high accuracy is key to narrowing the gaps.

“The literature is very clear that access to professional medical interpreters is associated with decreased health disparities for patients with limited English proficiency,” she said.

More cultural training for clinicians is needed surrounding beliefs about illness and that some care may be declined not because of a person’s limited English proficiency, but because their beliefs may keep them from getting care, Dr. Garcia-Bedoya added. When it comes to getting a flu shot, for example, sometimes belief systems, rather than English proficiency, keep people from accessing care.

What can be done?

Addressing barriers caused by lack of English proficiency will likely take change in policies, including one related reimbursement for medical interpreters, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Currently, only 15 states’ Medicaid programs or Children’s Health Insurance Programs reimburse providers for language services, the paper notes, and neither Medicare nor private insurers routinely pay for those services.

Recruiting bilingual providers and staff at health care facilities and in medical and nursing schools will also be important to narrow the gaps, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Strengthening standards for interpreters also will help. “Currently such standards vary by state or by institution and are not necessarily enforced,” she explained.

It will also be important to make sure patients know that they are entitled by law to care, free of discriminatory practices and to have certain language services including qualified interpreters, Dr. Himmelstein said.

Dr. Garcia-Bedoya said changes need to come from health systems working in combination with clinicians, providing resources so that quality interpreters can be accessed and making sure that equipment supports clear communication in telehealth. Patients’ language preferences should also be noted as soon as they make the appointment.

The findings of the study may have large significance as one in seven people in the United States speak Spanish at home, and 25 million people in the United States have limited English proficiency, the authors noted.

Dr. Himmelstein receives funding support from an Institutional National Research Service Award. Dr. Garcia-Bedoya reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Married docs remove girl’s lethal facial tumor in ‘excruciatingly difficult’ procedure

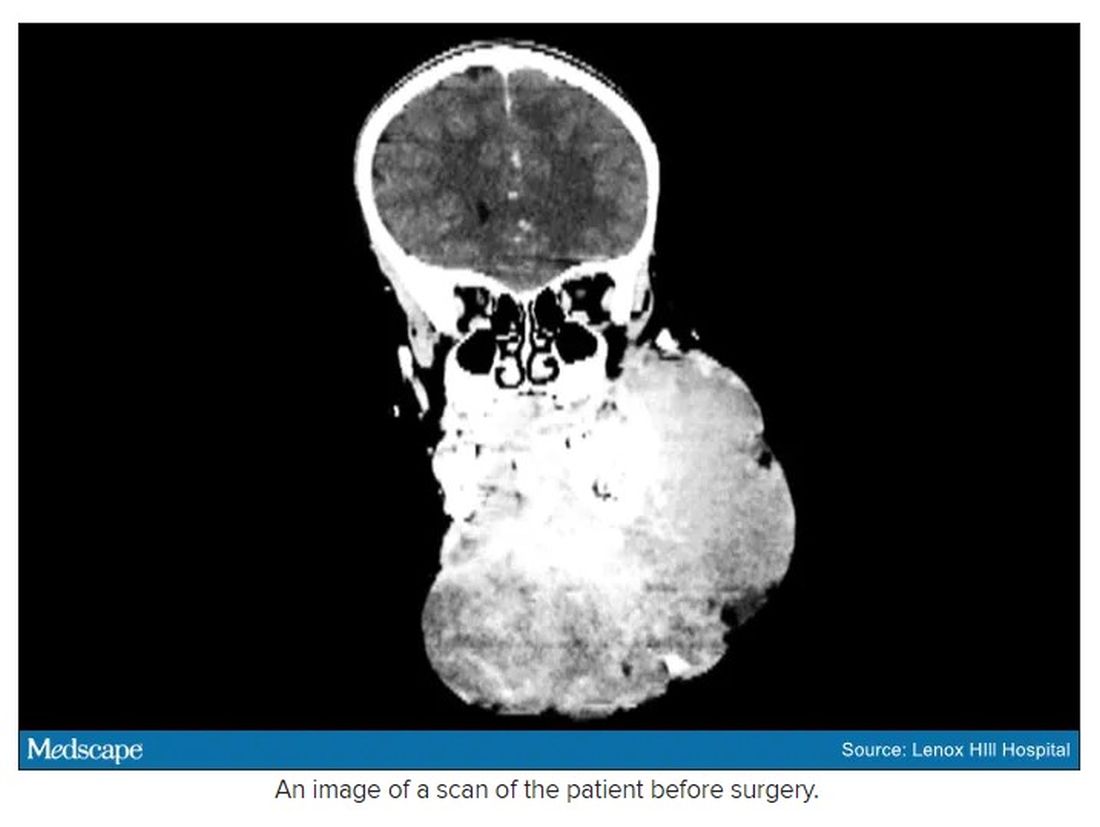

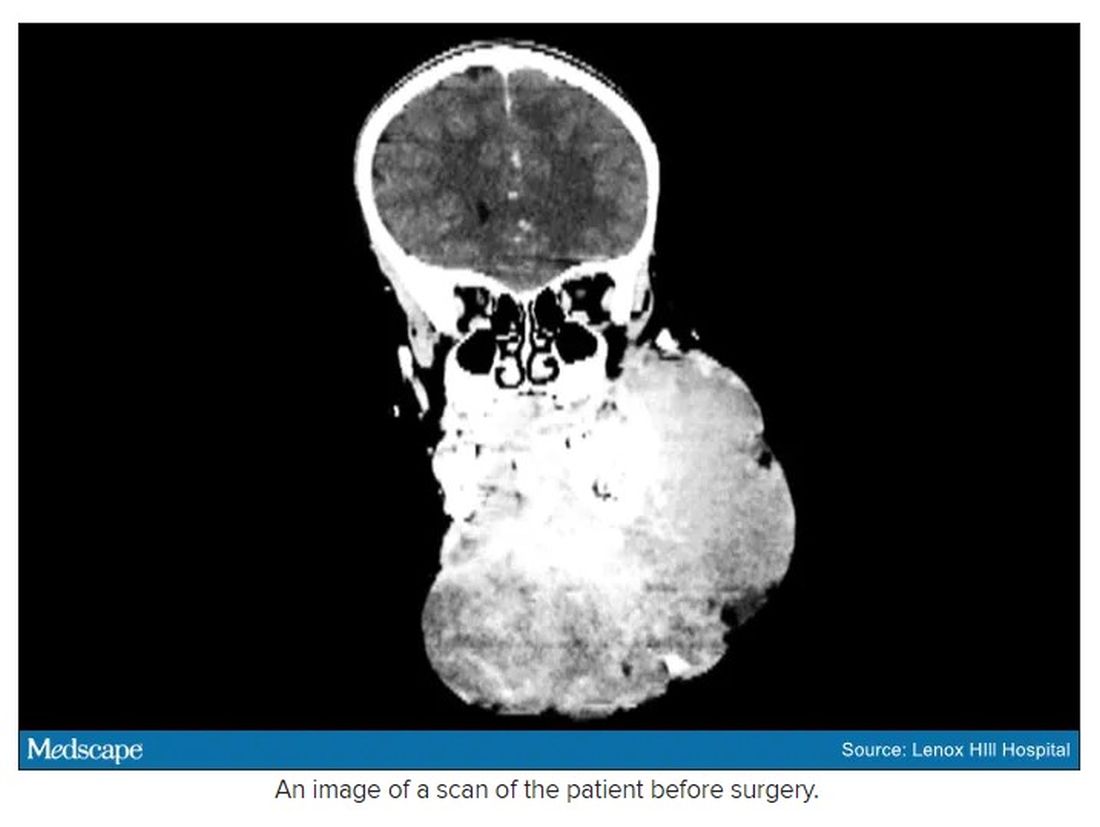

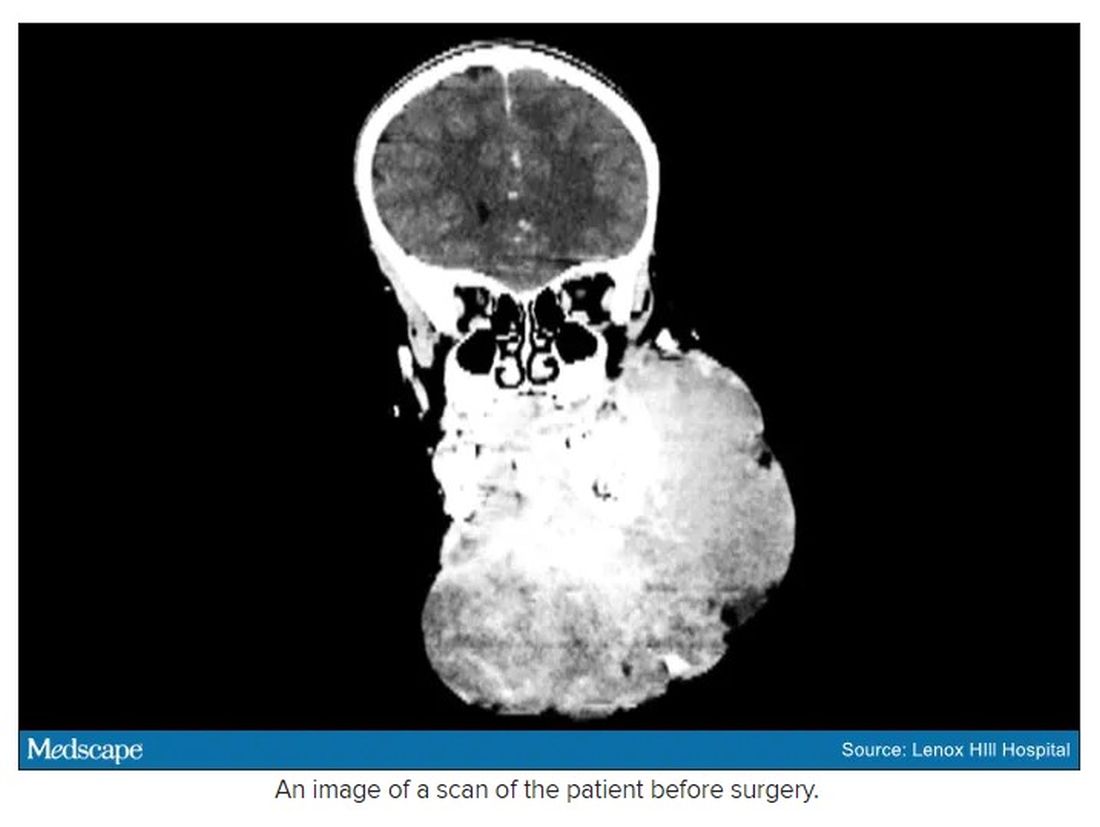

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

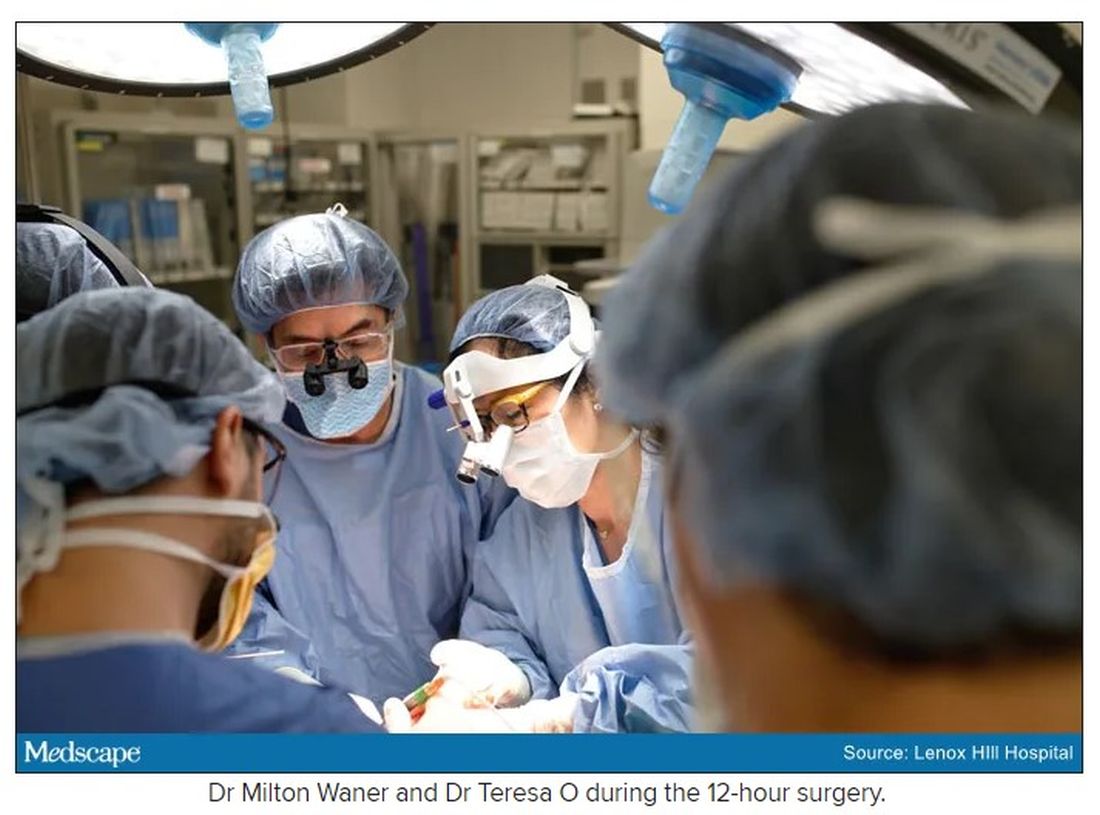

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Extra COVID-19 vaccine could help immunocompromised people

People whose immune systems are compromised by therapy or disease may benefit from additional doses of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, researchers say.

In a study involving 101 people with solid-organ transplants, there was a significant boost in antibodies after the patients received third doses of the Pfizer vaccine, said Nassim Kamar, MD, PhD, professor of nephrology at Toulouse University Hospital, France.

None of the transplant patients had antibodies against the virus before their first dose of the vaccine, and only 4% produced antibodies after the first dose. That proportion rose to 40% after the second dose and to 68% after the third dose.

The effect is so strong that Dr. Kamar and colleagues at Toulouse University Hospital routinely administer three doses of mRNA vaccines to patients with solid-organ transplant without testing them for antibodies.

“When we observed that the second dose was not sufficient to have an immune response, the Francophone Society of Transplantation asked the National Health Authority to allow the third dose,” he told this news organization.

That agency on April 11 approved third doses of mRNA vaccines not only for people with solid-organ transplants but also for those with recent bone marrow transplants, those undergoing dialysis, and those with autoimmune diseases who were receiving strong immunosuppressive treatment, such as anti-CD20 or antimetabolites. Contrary to their procedure for people with solid-organ transplants, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital test these patients for antibodies and administer third doses of vaccine only to those who test negative or have very low titers.

The researchers’ findings, published on June 23 as a letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, come as other researchers document more and more categories of patients whose responses to the vaccines typically fall short.

A study at the University of Pittsburgh that was published as a preprint on MedRxiv compared people with various health conditions to healthy health care workers. People with HIV who were taking antivirals against that virus responded almost as well as did the health care workers, said John Mellors, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the university. But people whose immune systems were compromised for other reasons fared less well.

“The areas of concern are hematological malignancy and solid-organ transplants, with the most nonresponsive groups being those who have had lung transplantation,” he said in an interview.

For patients with liver disease, mixed news came from the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021 annual meeting.

In a study involving patients with liver disease who had received the Pfizer vaccine at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, antibody titers were lower in patients who had received liver transplants or who had advanced liver fibrosis, as reported by this news organization.

A multicenter study in China that was presented at the ILC meeting and that was also published in the Journal of Hepatology, provided a more optimistic picture. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were immunized against SARS-CoV-2 with the Sinopharm vaccine, 95.5% had neutralizing antibodies; the median neutralizing antibody titer was 32.

In the Toulouse University Hospital study, for the 40 patients who were seropositive after the second dose, antibody titers increased from 36 before the third dose to 2,676 a month after the third dose, a statistically significant result (P < .001).

For patients whose immune systems are compromised for reasons other than having received a transplant, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital use a titer of 14 as the threshold below which they administer a third dose of mRNA vaccines. But Dr. Kamar acknowledged that the threshold is arbitrary and that the assays for antibodies with different vaccines in different populations can’t be compared head to head.

“We can’t tell you simply on the basis of the amount of antibody in your laboratory report how protected you are,” agreed William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who is a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Not enough research has been done to establish that relationship, and results vary from one laboratory to another, he said.

That doesn’t mean that antibody tests don’t help, Dr. Schaffner said. On the basis of views of other experts he has consulted, Dr. Schaffner recommends that people who are immunocompromised undergo an antibody test. If the test is positive – meaning they have some antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, however low the titers – patients can take fewer precautions than before they were vaccinated.

But they should still be more cautious than people with healthy immune systems, he said. “Would I be going to large indoor gatherings without a mask? No. Would I be outside without a mask? Yes. Would I gather with three other people who are vaccinated to play a game of bridge? Yes. You have to titrate things a little and use some common sense,” he added.

If the results are negative, such patients may still be protected. Much research remains to be done on T-cell immunity, a second line of defense against the virus. And the current assays often produce false negative results. But to be on the safe side, people with this result should assume that their vaccine is not protecting them, Dr. Schaffner said.

That suggestion contradicts the Food and Drug Administration, which issued a recommendation on May 19 against using antibody tests to check the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

The studies so far suggest that vaccines are safe for people whose immune systems are compromised, Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Kamar agreed. Dr. Kamar is aware of only two case reports of transplant patients rejecting their transplants after vaccination. One of these was his own patient, and the rejection occurred after her second dose. She has not needed dialysis, although her kidney function was impaired.

But the FDA has not approved additional doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to treat patients who are immunocompromised, and Dr. Kamar has not heard of any other national regulatory agencies that have.

In the United States, it may be difficult for anyone to obtain a third dose of vaccine outside of a clinical trial, Dr. Schaffner said, because vaccinators are likely to check databases and deny vaccination to anyone who has already received the recommended number.

Dr. Kamar, Dr. Mellors, and Dr. Schaffner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People whose immune systems are compromised by therapy or disease may benefit from additional doses of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, researchers say.

In a study involving 101 people with solid-organ transplants, there was a significant boost in antibodies after the patients received third doses of the Pfizer vaccine, said Nassim Kamar, MD, PhD, professor of nephrology at Toulouse University Hospital, France.

None of the transplant patients had antibodies against the virus before their first dose of the vaccine, and only 4% produced antibodies after the first dose. That proportion rose to 40% after the second dose and to 68% after the third dose.

The effect is so strong that Dr. Kamar and colleagues at Toulouse University Hospital routinely administer three doses of mRNA vaccines to patients with solid-organ transplant without testing them for antibodies.

“When we observed that the second dose was not sufficient to have an immune response, the Francophone Society of Transplantation asked the National Health Authority to allow the third dose,” he told this news organization.

That agency on April 11 approved third doses of mRNA vaccines not only for people with solid-organ transplants but also for those with recent bone marrow transplants, those undergoing dialysis, and those with autoimmune diseases who were receiving strong immunosuppressive treatment, such as anti-CD20 or antimetabolites. Contrary to their procedure for people with solid-organ transplants, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital test these patients for antibodies and administer third doses of vaccine only to those who test negative or have very low titers.

The researchers’ findings, published on June 23 as a letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, come as other researchers document more and more categories of patients whose responses to the vaccines typically fall short.

A study at the University of Pittsburgh that was published as a preprint on MedRxiv compared people with various health conditions to healthy health care workers. People with HIV who were taking antivirals against that virus responded almost as well as did the health care workers, said John Mellors, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the university. But people whose immune systems were compromised for other reasons fared less well.

“The areas of concern are hematological malignancy and solid-organ transplants, with the most nonresponsive groups being those who have had lung transplantation,” he said in an interview.

For patients with liver disease, mixed news came from the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021 annual meeting.

In a study involving patients with liver disease who had received the Pfizer vaccine at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, antibody titers were lower in patients who had received liver transplants or who had advanced liver fibrosis, as reported by this news organization.

A multicenter study in China that was presented at the ILC meeting and that was also published in the Journal of Hepatology, provided a more optimistic picture. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were immunized against SARS-CoV-2 with the Sinopharm vaccine, 95.5% had neutralizing antibodies; the median neutralizing antibody titer was 32.

In the Toulouse University Hospital study, for the 40 patients who were seropositive after the second dose, antibody titers increased from 36 before the third dose to 2,676 a month after the third dose, a statistically significant result (P < .001).

For patients whose immune systems are compromised for reasons other than having received a transplant, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital use a titer of 14 as the threshold below which they administer a third dose of mRNA vaccines. But Dr. Kamar acknowledged that the threshold is arbitrary and that the assays for antibodies with different vaccines in different populations can’t be compared head to head.

“We can’t tell you simply on the basis of the amount of antibody in your laboratory report how protected you are,” agreed William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who is a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Not enough research has been done to establish that relationship, and results vary from one laboratory to another, he said.

That doesn’t mean that antibody tests don’t help, Dr. Schaffner said. On the basis of views of other experts he has consulted, Dr. Schaffner recommends that people who are immunocompromised undergo an antibody test. If the test is positive – meaning they have some antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, however low the titers – patients can take fewer precautions than before they were vaccinated.

But they should still be more cautious than people with healthy immune systems, he said. “Would I be going to large indoor gatherings without a mask? No. Would I be outside without a mask? Yes. Would I gather with three other people who are vaccinated to play a game of bridge? Yes. You have to titrate things a little and use some common sense,” he added.

If the results are negative, such patients may still be protected. Much research remains to be done on T-cell immunity, a second line of defense against the virus. And the current assays often produce false negative results. But to be on the safe side, people with this result should assume that their vaccine is not protecting them, Dr. Schaffner said.