User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Is the WHO’s HPV vaccination target within reach?

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

FROM PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

FDA scrutinizes cancer therapies granted accelerated approval

U.S. regulators are stepping up scrutiny of therapies that were granted an accelerated approval to treat cancers on the basis of surrogate endpoints but have failed to show clinical or survival benefits upon more extensive testing.

At issue are a number of cancer indications for immunotherapies. Four have already been withdrawn (voluntarily by the manufacturer), and six more will be reviewed at an upcoming meeting.

In recent years, the US Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approvals to oncology medicines on the basis of evidence that suggests a benefit for patients. Examples of such evidence relate to response rates and estimates of tumor shrinkage. But these approvals are granted on the condition that the manufacturer conducts larger clinical trials that show clinical benefit, including benefit in overall survival.

Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, has argued that the point of these conditional approvals is to find acceptable surrogate markers to allow people with “desperate illnesses” to have access to potentially helpful drugs while work continues to determine the drug’s actual benefit to patients.

Oncologists are now questioning whether the FDA has become too lenient in its approach, Daniel A. Goldstein, MD, a senior physician in medical oncology and internal medicine at the Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, told this news organization.

“The main two things you want from a cancer drug is to live longer and live a higher quality of life,” said Goldstein. “But these endpoints that they’ve been using over the past few years are not really giving us confidence that these drugs are actually going to help to live longer or better.”

Dr. Pazdur said the FDA will consider withdrawing its accelerated approvals when results of further studies do not confirm expected benefit for patients.

“This is like the pendulum has swung as far as it was going to swing and now is on the backswing,” said Dr. Goldstein, also of the department of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “You could call this a watershed moment.”

Although there’s near universal interest in allowing people with advanced cancer access to promising medicines, there’s also rising concern about exposing patients needlessly to costly drugs with potentially tough side effects. That may prompt a shift in the standards U.S. regulators apply to cancer medicines, Dr. Goldstein said.

Indications withdrawn and under review

In a meeting scheduled for April 27-29, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee will review indications granted through the accelerated approval process for three immunotherapies: pembrolizumab (Keytruda), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), and nivolumab (Opdivo).

It is part of an industry-wide evaluation of accelerated approvals for cancer indications in which confirmatory trials did not confirm clinical benefit, the FDA noted.

The process has already led to voluntary withdrawals of four cancer indications by the manufacturers, including one indication each for pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and nivolumab, and one for durvalumab (Imfinzi).

All of these immunotherapies are approved for numerous cancer indications, and they all remain on the market. It is only the U.S. approvals for particular cancer indications that have been withdrawn.

In the past, olaratumab (Lartruvo) was withdrawn from the market altogether. The FDA granted accelerated approval of the drug for soft tissue sarcoma, but clinical benefit was not confirmed in a phase 3 trial.

Issue highlighted by Dr. Prasad and Dr. Gyawali

In recent years, much of the attention on accelerated approvals was spurred by the work of a few researchers, particularly Vinay Prasad, MD, MPH, associate professor in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from Queen’s University Cancer Research Institute, Kingston, Ont. (Both are regular contributors to the oncology section of this news organization.)

Dr. Goldstein made this point in a tweet about the FDA’s announcement of the April ODAC meetings:

“Well done to @oncology_bg and @VPrasadMDMPH among others for highlighting in their papers that the FDA wasn’t properly evaluating accelerated approval drugs.

FDA have listened.

And I thought that the impact of academia was limited!”

Dr. Prasad has made the case for closer scrutiny of accelerated approvals in a number of journal articles and in his 2020 book, “Malignant: How Bad Policy and Bad Evidence Harm People with Cancer,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press.

The book includes highlights of a 2016 article published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings that focused on surrogate endpoints used for FDA approvals. In the article, Dr. Prasad and his coauthor report that they did not find formal analyses of the strength of the surrogate-survival correlation in 14 of 25 cases of accelerated approvals (56%) and in 11 of 30 traditional approvals (37%).

“Our results were concerning. They imply that many surrogates are based on little more than a gut feeling. You might rationalize that and argue a gut feeling is the same as ‘reasonably likely to predict,’ but no reasonable person could think a gut feeling means established,” Dr. Prasad writes in his book. “Our result suggests the FDA is using surrogate endpoints far beyond what may be fair or reasonable.”

Dr. Gyawali has argued that the process by which the FDA assesses cancer drugs for approvals has undergone a profound shift. He has most recently remarked on this in an October 2020 commentary on Medscape.

“Until the recent floodgate of approvals based on response rates from single-arm trials, the majority of cancer therapy decisions were supported by evidence generated from randomized controlled trials (RCTs),” Dr. Gyawali wrote. “The evidence base to support clinical decisions in managing therapeutic side effects has been comparatively sparse.”

Accelerated approval to improve access

The FDA has struggled for about 2 decades with questions of where to set the bar on evidence for promising cancer drugs.

The agency’s accelerated approval program for drugs began in 1992. During the first decade, the focus was largely on medicines related to HIV.

In the early 2000s, oncology drugs began to dominate the program.

Dr. Pazdur has presided over the FDA’s marked changes regarding the use of surrogate markers when weighing whether to allow sales of cancer medicines. Formerly a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Dr. Pazdur joined the FDA as director of the Division of Oncology Drug Products in 1999.

Soon after his appointment, he had to field inquiries from pharmaceutical companies about how much evidence they needed to receive accelerated approvals.

Early on, he publicly expressed impatience about the drugmakers’ approach. “The purpose of accelerated approval was not accelerated drug company profits,” Dr. Padzur said at a 2004 ODAC meeting.

Rather, the point is to allow access to potentially helpful drugs while work continues to determine their actual benefit to patients, he explained.

“It wasn’t a license to do less, less, less, and less to a point now that we may be getting companies that are coming in” intent on determining the minimum evidence the FDA will take, Dr. Pazdur said. “It shouldn’t be what is the lowest. It is what is a sufficient amount to give patients and physicians a real understanding of what their drug will do.”

In a 2016 interview with The New York Times, Dr. Pazdur said that his views on cancer drug approvals have evolved with time. He described himself as being “on a jihad to streamline the review process and get things out the door faster.”

“I have evolved from regulator to regulator-advocate,” Dr. Pazdur told the newspaper.

His attitude reflected his personal experience in losing his wife to ovarian cancer in 2015, as well as shifts in science and law. In 2012, Congress passed a law that gave the FDA new resources to speed medicines for life-threatening diseases to market. In addition, advances in genetics appeared to be making some medications more effective and easier to test, Dr. Pazdur said in The New York Times interview.

Withdrawals seen as sign of success

Since the program’s inception, only 6% of accelerated approvals for oncology indications have been withdrawn, the FDA said.

It would be a sign that the program is working if the April meetings lead to further withdrawals of indications that have been granted accelerated approval, Julie R. Gralow, MD, chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, said in an interview with this news organization.

“It shouldn’t be seen as a failure,” Dr. Gralow said.

In her own practice at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, she has seen the value of emerging therapies for patients fighting advanced cancers. During her 25 years of clinical practice in an academic setting, she has gained access to drugs through single-patient investigative new drug applications.

However, this path is not an option for many patients who undergo treatment in facilities other than academic centers, she commented. She noted that the accelerated approval process is a way to expand access to emerging medicines, but she sees a need for caution in the use of drugs that have been given only this conditional approval. She emphasizes that such drugs may be suitable only for certain patients.

“I would say that, for metastatic patients, patients with incurable disease, we are willing to take some risk,” Dr. Gralow said. “We don’t have other options. They can’t wait the years that it would take to get a drug approved.”

One such patient is David Mitchell, who serves as the consumer representative on ODAC. He told this news organization that he is taking three drugs for multiple myeloma that received accelerated approvals: pomalidomide, bortezomib, and daratumumab.

“I want the FDA to have the option to approve drugs in an accelerated pathway, because as a patient taking three drugs granted accelerated approval, I’m benefiting – I’ve lived the benefit,” Mr. Mitchell said, “and I want other patients to have the opportunity to have that benefit.”

He believes that the FDA’s approach regarding accelerated approvals serves to get potentially beneficial medicines to patients who have few options and also fulfills the FDA’s mandate to protect the public from treatments that have little benefit but can cause harm.

Accelerated approval also offers needed flexibility to drugmakers as they develop more specifically targeted drugs for diseases that affect relatively few people, such as multiple myeloma, he said. “As the targeting of your therapies gets tighter and for smaller groups of patients, you have a harder time following the traditional model,” such as conducting large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that may indicate increased overall survival, he said.

“To me, this is the way the FDA intended it to work,” he added. “It’s going to offer the accelerated approval based on a surrogate endpoint for a safe drug, but it’s going to require the confirmatory trial, and if the confirmatory trial fails, it will pull the drug off the market.”

Some medicines that have received accelerated approvals may ultimately be found not to benefit patients, Mr. Mitchell acknowledged. But people in his situation, whose disease has progressed despite treatments, may want to take that risk, he added.

Four cancer indications recently withdrawn voluntarily by the manufacturer

- December 2020: Nivolumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer with progression after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy (Bristol Myers Squibb).

- February 2021: Durvalumab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease has progressed during or following platinum-based chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy (AstraZeneca).

- March 2021: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other prior line of therapy (Merck).

- March 2021: Atezolizumab for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing atezolizumab chemotherapy or disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy (Genentech).

Six cancer indications under review at the April 2021 ODAC meeting

- Atezolizumab indicated in combination with protein-bound for the treatment of adults with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative whose tumors express PD-L1 (PD-L1 stained tumor-infiltrating immune cells of any intensity covering ≥1% of the tumor area), as determined by an FDA-approved test.

- Atezolizumab indicated for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with recurrent locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma whose tumors express PD-L1 (Combined Positive Score ≥1), as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression on or after two or more prior lines of therapy including fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy and if appropriate, HER2/neu-targeted therapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with who have been previously treated with .

- Nivolumab indicated as a single agent for the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who have been previously treated with sorafenib.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. regulators are stepping up scrutiny of therapies that were granted an accelerated approval to treat cancers on the basis of surrogate endpoints but have failed to show clinical or survival benefits upon more extensive testing.

At issue are a number of cancer indications for immunotherapies. Four have already been withdrawn (voluntarily by the manufacturer), and six more will be reviewed at an upcoming meeting.

In recent years, the US Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approvals to oncology medicines on the basis of evidence that suggests a benefit for patients. Examples of such evidence relate to response rates and estimates of tumor shrinkage. But these approvals are granted on the condition that the manufacturer conducts larger clinical trials that show clinical benefit, including benefit in overall survival.

Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, has argued that the point of these conditional approvals is to find acceptable surrogate markers to allow people with “desperate illnesses” to have access to potentially helpful drugs while work continues to determine the drug’s actual benefit to patients.

Oncologists are now questioning whether the FDA has become too lenient in its approach, Daniel A. Goldstein, MD, a senior physician in medical oncology and internal medicine at the Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, told this news organization.

“The main two things you want from a cancer drug is to live longer and live a higher quality of life,” said Goldstein. “But these endpoints that they’ve been using over the past few years are not really giving us confidence that these drugs are actually going to help to live longer or better.”

Dr. Pazdur said the FDA will consider withdrawing its accelerated approvals when results of further studies do not confirm expected benefit for patients.

“This is like the pendulum has swung as far as it was going to swing and now is on the backswing,” said Dr. Goldstein, also of the department of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “You could call this a watershed moment.”

Although there’s near universal interest in allowing people with advanced cancer access to promising medicines, there’s also rising concern about exposing patients needlessly to costly drugs with potentially tough side effects. That may prompt a shift in the standards U.S. regulators apply to cancer medicines, Dr. Goldstein said.

Indications withdrawn and under review

In a meeting scheduled for April 27-29, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee will review indications granted through the accelerated approval process for three immunotherapies: pembrolizumab (Keytruda), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), and nivolumab (Opdivo).

It is part of an industry-wide evaluation of accelerated approvals for cancer indications in which confirmatory trials did not confirm clinical benefit, the FDA noted.

The process has already led to voluntary withdrawals of four cancer indications by the manufacturers, including one indication each for pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and nivolumab, and one for durvalumab (Imfinzi).

All of these immunotherapies are approved for numerous cancer indications, and they all remain on the market. It is only the U.S. approvals for particular cancer indications that have been withdrawn.

In the past, olaratumab (Lartruvo) was withdrawn from the market altogether. The FDA granted accelerated approval of the drug for soft tissue sarcoma, but clinical benefit was not confirmed in a phase 3 trial.

Issue highlighted by Dr. Prasad and Dr. Gyawali

In recent years, much of the attention on accelerated approvals was spurred by the work of a few researchers, particularly Vinay Prasad, MD, MPH, associate professor in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from Queen’s University Cancer Research Institute, Kingston, Ont. (Both are regular contributors to the oncology section of this news organization.)

Dr. Goldstein made this point in a tweet about the FDA’s announcement of the April ODAC meetings:

“Well done to @oncology_bg and @VPrasadMDMPH among others for highlighting in their papers that the FDA wasn’t properly evaluating accelerated approval drugs.

FDA have listened.

And I thought that the impact of academia was limited!”

Dr. Prasad has made the case for closer scrutiny of accelerated approvals in a number of journal articles and in his 2020 book, “Malignant: How Bad Policy and Bad Evidence Harm People with Cancer,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press.

The book includes highlights of a 2016 article published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings that focused on surrogate endpoints used for FDA approvals. In the article, Dr. Prasad and his coauthor report that they did not find formal analyses of the strength of the surrogate-survival correlation in 14 of 25 cases of accelerated approvals (56%) and in 11 of 30 traditional approvals (37%).

“Our results were concerning. They imply that many surrogates are based on little more than a gut feeling. You might rationalize that and argue a gut feeling is the same as ‘reasonably likely to predict,’ but no reasonable person could think a gut feeling means established,” Dr. Prasad writes in his book. “Our result suggests the FDA is using surrogate endpoints far beyond what may be fair or reasonable.”

Dr. Gyawali has argued that the process by which the FDA assesses cancer drugs for approvals has undergone a profound shift. He has most recently remarked on this in an October 2020 commentary on Medscape.

“Until the recent floodgate of approvals based on response rates from single-arm trials, the majority of cancer therapy decisions were supported by evidence generated from randomized controlled trials (RCTs),” Dr. Gyawali wrote. “The evidence base to support clinical decisions in managing therapeutic side effects has been comparatively sparse.”

Accelerated approval to improve access

The FDA has struggled for about 2 decades with questions of where to set the bar on evidence for promising cancer drugs.

The agency’s accelerated approval program for drugs began in 1992. During the first decade, the focus was largely on medicines related to HIV.

In the early 2000s, oncology drugs began to dominate the program.

Dr. Pazdur has presided over the FDA’s marked changes regarding the use of surrogate markers when weighing whether to allow sales of cancer medicines. Formerly a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Dr. Pazdur joined the FDA as director of the Division of Oncology Drug Products in 1999.

Soon after his appointment, he had to field inquiries from pharmaceutical companies about how much evidence they needed to receive accelerated approvals.

Early on, he publicly expressed impatience about the drugmakers’ approach. “The purpose of accelerated approval was not accelerated drug company profits,” Dr. Padzur said at a 2004 ODAC meeting.

Rather, the point is to allow access to potentially helpful drugs while work continues to determine their actual benefit to patients, he explained.

“It wasn’t a license to do less, less, less, and less to a point now that we may be getting companies that are coming in” intent on determining the minimum evidence the FDA will take, Dr. Pazdur said. “It shouldn’t be what is the lowest. It is what is a sufficient amount to give patients and physicians a real understanding of what their drug will do.”

In a 2016 interview with The New York Times, Dr. Pazdur said that his views on cancer drug approvals have evolved with time. He described himself as being “on a jihad to streamline the review process and get things out the door faster.”

“I have evolved from regulator to regulator-advocate,” Dr. Pazdur told the newspaper.

His attitude reflected his personal experience in losing his wife to ovarian cancer in 2015, as well as shifts in science and law. In 2012, Congress passed a law that gave the FDA new resources to speed medicines for life-threatening diseases to market. In addition, advances in genetics appeared to be making some medications more effective and easier to test, Dr. Pazdur said in The New York Times interview.

Withdrawals seen as sign of success

Since the program’s inception, only 6% of accelerated approvals for oncology indications have been withdrawn, the FDA said.

It would be a sign that the program is working if the April meetings lead to further withdrawals of indications that have been granted accelerated approval, Julie R. Gralow, MD, chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, said in an interview with this news organization.

“It shouldn’t be seen as a failure,” Dr. Gralow said.

In her own practice at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, she has seen the value of emerging therapies for patients fighting advanced cancers. During her 25 years of clinical practice in an academic setting, she has gained access to drugs through single-patient investigative new drug applications.

However, this path is not an option for many patients who undergo treatment in facilities other than academic centers, she commented. She noted that the accelerated approval process is a way to expand access to emerging medicines, but she sees a need for caution in the use of drugs that have been given only this conditional approval. She emphasizes that such drugs may be suitable only for certain patients.

“I would say that, for metastatic patients, patients with incurable disease, we are willing to take some risk,” Dr. Gralow said. “We don’t have other options. They can’t wait the years that it would take to get a drug approved.”

One such patient is David Mitchell, who serves as the consumer representative on ODAC. He told this news organization that he is taking three drugs for multiple myeloma that received accelerated approvals: pomalidomide, bortezomib, and daratumumab.

“I want the FDA to have the option to approve drugs in an accelerated pathway, because as a patient taking three drugs granted accelerated approval, I’m benefiting – I’ve lived the benefit,” Mr. Mitchell said, “and I want other patients to have the opportunity to have that benefit.”

He believes that the FDA’s approach regarding accelerated approvals serves to get potentially beneficial medicines to patients who have few options and also fulfills the FDA’s mandate to protect the public from treatments that have little benefit but can cause harm.

Accelerated approval also offers needed flexibility to drugmakers as they develop more specifically targeted drugs for diseases that affect relatively few people, such as multiple myeloma, he said. “As the targeting of your therapies gets tighter and for smaller groups of patients, you have a harder time following the traditional model,” such as conducting large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that may indicate increased overall survival, he said.

“To me, this is the way the FDA intended it to work,” he added. “It’s going to offer the accelerated approval based on a surrogate endpoint for a safe drug, but it’s going to require the confirmatory trial, and if the confirmatory trial fails, it will pull the drug off the market.”

Some medicines that have received accelerated approvals may ultimately be found not to benefit patients, Mr. Mitchell acknowledged. But people in his situation, whose disease has progressed despite treatments, may want to take that risk, he added.

Four cancer indications recently withdrawn voluntarily by the manufacturer

- December 2020: Nivolumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer with progression after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy (Bristol Myers Squibb).

- February 2021: Durvalumab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease has progressed during or following platinum-based chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy (AstraZeneca).

- March 2021: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other prior line of therapy (Merck).

- March 2021: Atezolizumab for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing atezolizumab chemotherapy or disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy (Genentech).

Six cancer indications under review at the April 2021 ODAC meeting

- Atezolizumab indicated in combination with protein-bound for the treatment of adults with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative whose tumors express PD-L1 (PD-L1 stained tumor-infiltrating immune cells of any intensity covering ≥1% of the tumor area), as determined by an FDA-approved test.

- Atezolizumab indicated for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with recurrent locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma whose tumors express PD-L1 (Combined Positive Score ≥1), as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression on or after two or more prior lines of therapy including fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy and if appropriate, HER2/neu-targeted therapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with who have been previously treated with .

- Nivolumab indicated as a single agent for the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who have been previously treated with sorafenib.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. regulators are stepping up scrutiny of therapies that were granted an accelerated approval to treat cancers on the basis of surrogate endpoints but have failed to show clinical or survival benefits upon more extensive testing.

At issue are a number of cancer indications for immunotherapies. Four have already been withdrawn (voluntarily by the manufacturer), and six more will be reviewed at an upcoming meeting.

In recent years, the US Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approvals to oncology medicines on the basis of evidence that suggests a benefit for patients. Examples of such evidence relate to response rates and estimates of tumor shrinkage. But these approvals are granted on the condition that the manufacturer conducts larger clinical trials that show clinical benefit, including benefit in overall survival.

Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, has argued that the point of these conditional approvals is to find acceptable surrogate markers to allow people with “desperate illnesses” to have access to potentially helpful drugs while work continues to determine the drug’s actual benefit to patients.

Oncologists are now questioning whether the FDA has become too lenient in its approach, Daniel A. Goldstein, MD, a senior physician in medical oncology and internal medicine at the Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, told this news organization.

“The main two things you want from a cancer drug is to live longer and live a higher quality of life,” said Goldstein. “But these endpoints that they’ve been using over the past few years are not really giving us confidence that these drugs are actually going to help to live longer or better.”

Dr. Pazdur said the FDA will consider withdrawing its accelerated approvals when results of further studies do not confirm expected benefit for patients.

“This is like the pendulum has swung as far as it was going to swing and now is on the backswing,” said Dr. Goldstein, also of the department of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “You could call this a watershed moment.”

Although there’s near universal interest in allowing people with advanced cancer access to promising medicines, there’s also rising concern about exposing patients needlessly to costly drugs with potentially tough side effects. That may prompt a shift in the standards U.S. regulators apply to cancer medicines, Dr. Goldstein said.

Indications withdrawn and under review

In a meeting scheduled for April 27-29, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee will review indications granted through the accelerated approval process for three immunotherapies: pembrolizumab (Keytruda), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), and nivolumab (Opdivo).

It is part of an industry-wide evaluation of accelerated approvals for cancer indications in which confirmatory trials did not confirm clinical benefit, the FDA noted.

The process has already led to voluntary withdrawals of four cancer indications by the manufacturers, including one indication each for pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and nivolumab, and one for durvalumab (Imfinzi).

All of these immunotherapies are approved for numerous cancer indications, and they all remain on the market. It is only the U.S. approvals for particular cancer indications that have been withdrawn.

In the past, olaratumab (Lartruvo) was withdrawn from the market altogether. The FDA granted accelerated approval of the drug for soft tissue sarcoma, but clinical benefit was not confirmed in a phase 3 trial.

Issue highlighted by Dr. Prasad and Dr. Gyawali

In recent years, much of the attention on accelerated approvals was spurred by the work of a few researchers, particularly Vinay Prasad, MD, MPH, associate professor in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, and Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, from Queen’s University Cancer Research Institute, Kingston, Ont. (Both are regular contributors to the oncology section of this news organization.)

Dr. Goldstein made this point in a tweet about the FDA’s announcement of the April ODAC meetings:

“Well done to @oncology_bg and @VPrasadMDMPH among others for highlighting in their papers that the FDA wasn’t properly evaluating accelerated approval drugs.

FDA have listened.

And I thought that the impact of academia was limited!”

Dr. Prasad has made the case for closer scrutiny of accelerated approvals in a number of journal articles and in his 2020 book, “Malignant: How Bad Policy and Bad Evidence Harm People with Cancer,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press.

The book includes highlights of a 2016 article published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings that focused on surrogate endpoints used for FDA approvals. In the article, Dr. Prasad and his coauthor report that they did not find formal analyses of the strength of the surrogate-survival correlation in 14 of 25 cases of accelerated approvals (56%) and in 11 of 30 traditional approvals (37%).

“Our results were concerning. They imply that many surrogates are based on little more than a gut feeling. You might rationalize that and argue a gut feeling is the same as ‘reasonably likely to predict,’ but no reasonable person could think a gut feeling means established,” Dr. Prasad writes in his book. “Our result suggests the FDA is using surrogate endpoints far beyond what may be fair or reasonable.”

Dr. Gyawali has argued that the process by which the FDA assesses cancer drugs for approvals has undergone a profound shift. He has most recently remarked on this in an October 2020 commentary on Medscape.

“Until the recent floodgate of approvals based on response rates from single-arm trials, the majority of cancer therapy decisions were supported by evidence generated from randomized controlled trials (RCTs),” Dr. Gyawali wrote. “The evidence base to support clinical decisions in managing therapeutic side effects has been comparatively sparse.”

Accelerated approval to improve access

The FDA has struggled for about 2 decades with questions of where to set the bar on evidence for promising cancer drugs.

The agency’s accelerated approval program for drugs began in 1992. During the first decade, the focus was largely on medicines related to HIV.

In the early 2000s, oncology drugs began to dominate the program.

Dr. Pazdur has presided over the FDA’s marked changes regarding the use of surrogate markers when weighing whether to allow sales of cancer medicines. Formerly a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Dr. Pazdur joined the FDA as director of the Division of Oncology Drug Products in 1999.

Soon after his appointment, he had to field inquiries from pharmaceutical companies about how much evidence they needed to receive accelerated approvals.

Early on, he publicly expressed impatience about the drugmakers’ approach. “The purpose of accelerated approval was not accelerated drug company profits,” Dr. Padzur said at a 2004 ODAC meeting.

Rather, the point is to allow access to potentially helpful drugs while work continues to determine their actual benefit to patients, he explained.

“It wasn’t a license to do less, less, less, and less to a point now that we may be getting companies that are coming in” intent on determining the minimum evidence the FDA will take, Dr. Pazdur said. “It shouldn’t be what is the lowest. It is what is a sufficient amount to give patients and physicians a real understanding of what their drug will do.”

In a 2016 interview with The New York Times, Dr. Pazdur said that his views on cancer drug approvals have evolved with time. He described himself as being “on a jihad to streamline the review process and get things out the door faster.”

“I have evolved from regulator to regulator-advocate,” Dr. Pazdur told the newspaper.

His attitude reflected his personal experience in losing his wife to ovarian cancer in 2015, as well as shifts in science and law. In 2012, Congress passed a law that gave the FDA new resources to speed medicines for life-threatening diseases to market. In addition, advances in genetics appeared to be making some medications more effective and easier to test, Dr. Pazdur said in The New York Times interview.

Withdrawals seen as sign of success

Since the program’s inception, only 6% of accelerated approvals for oncology indications have been withdrawn, the FDA said.

It would be a sign that the program is working if the April meetings lead to further withdrawals of indications that have been granted accelerated approval, Julie R. Gralow, MD, chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, said in an interview with this news organization.

“It shouldn’t be seen as a failure,” Dr. Gralow said.

In her own practice at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, she has seen the value of emerging therapies for patients fighting advanced cancers. During her 25 years of clinical practice in an academic setting, she has gained access to drugs through single-patient investigative new drug applications.

However, this path is not an option for many patients who undergo treatment in facilities other than academic centers, she commented. She noted that the accelerated approval process is a way to expand access to emerging medicines, but she sees a need for caution in the use of drugs that have been given only this conditional approval. She emphasizes that such drugs may be suitable only for certain patients.

“I would say that, for metastatic patients, patients with incurable disease, we are willing to take some risk,” Dr. Gralow said. “We don’t have other options. They can’t wait the years that it would take to get a drug approved.”

One such patient is David Mitchell, who serves as the consumer representative on ODAC. He told this news organization that he is taking three drugs for multiple myeloma that received accelerated approvals: pomalidomide, bortezomib, and daratumumab.

“I want the FDA to have the option to approve drugs in an accelerated pathway, because as a patient taking three drugs granted accelerated approval, I’m benefiting – I’ve lived the benefit,” Mr. Mitchell said, “and I want other patients to have the opportunity to have that benefit.”

He believes that the FDA’s approach regarding accelerated approvals serves to get potentially beneficial medicines to patients who have few options and also fulfills the FDA’s mandate to protect the public from treatments that have little benefit but can cause harm.

Accelerated approval also offers needed flexibility to drugmakers as they develop more specifically targeted drugs for diseases that affect relatively few people, such as multiple myeloma, he said. “As the targeting of your therapies gets tighter and for smaller groups of patients, you have a harder time following the traditional model,” such as conducting large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that may indicate increased overall survival, he said.

“To me, this is the way the FDA intended it to work,” he added. “It’s going to offer the accelerated approval based on a surrogate endpoint for a safe drug, but it’s going to require the confirmatory trial, and if the confirmatory trial fails, it will pull the drug off the market.”

Some medicines that have received accelerated approvals may ultimately be found not to benefit patients, Mr. Mitchell acknowledged. But people in his situation, whose disease has progressed despite treatments, may want to take that risk, he added.

Four cancer indications recently withdrawn voluntarily by the manufacturer

- December 2020: Nivolumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer with progression after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other line of therapy (Bristol Myers Squibb).

- February 2021: Durvalumab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease has progressed during or following platinum-based chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy (AstraZeneca).

- March 2021: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy and at least one other prior line of therapy (Merck).

- March 2021: Atezolizumab for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing atezolizumab chemotherapy or disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy (Genentech).

Six cancer indications under review at the April 2021 ODAC meeting

- Atezolizumab indicated in combination with protein-bound for the treatment of adults with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative whose tumors express PD-L1 (PD-L1 stained tumor-infiltrating immune cells of any intensity covering ≥1% of the tumor area), as determined by an FDA-approved test.

- Atezolizumab indicated for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with recurrent locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma whose tumors express PD-L1 (Combined Positive Score ≥1), as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression on or after two or more prior lines of therapy including fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy and if appropriate, HER2/neu-targeted therapy.

- Pembrolizumab indicated for the treatment of patients with who have been previously treated with .

- Nivolumab indicated as a single agent for the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who have been previously treated with sorafenib.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

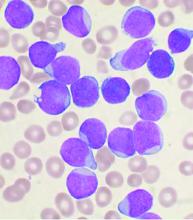

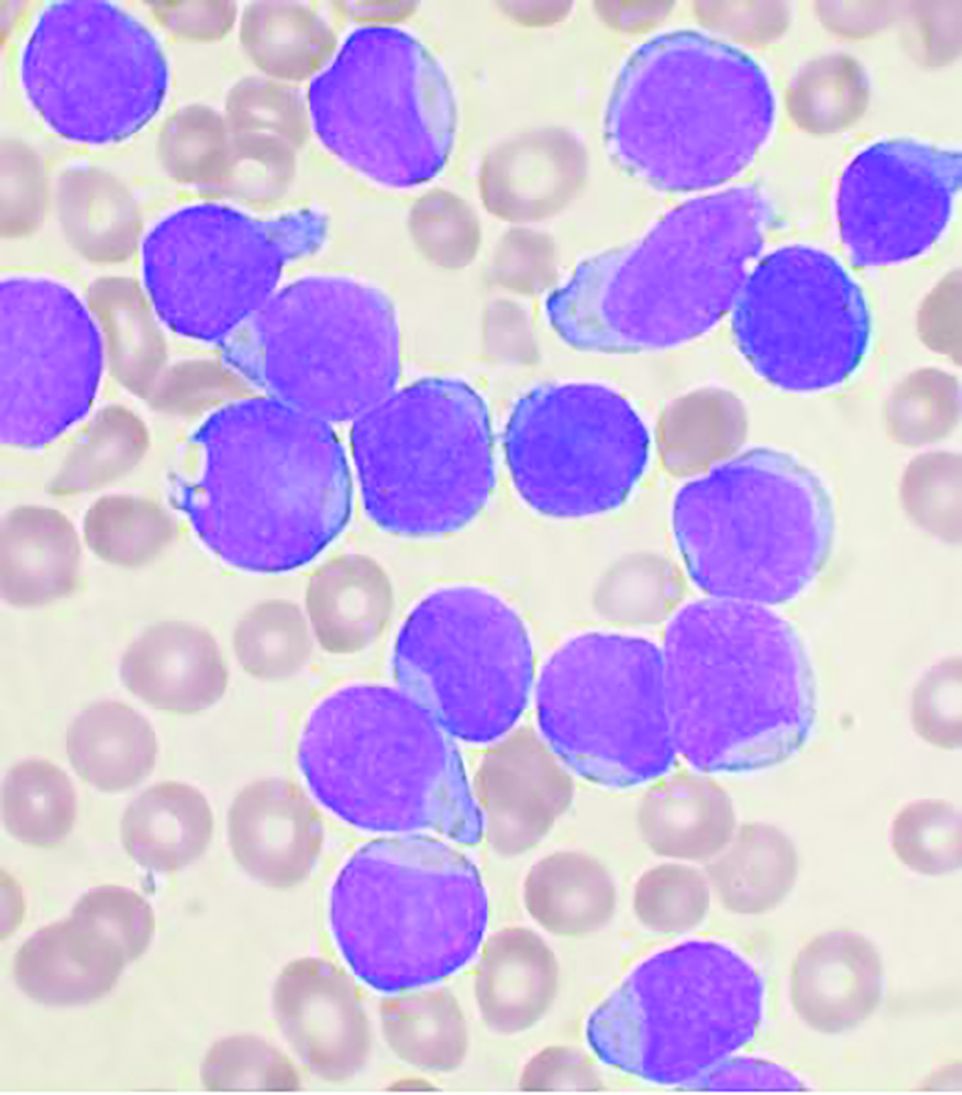

Updated recommendations released on COVID-19 and pediatric ALL

The main threat to the vast majority of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia still remains the ALL itself, according to updated recommendations released by the Leukemia Committee of the French Society for the Fight Against Cancers and Leukemias in Children and Adolescents (SFCE).

“The situation of the current COVID-19 pandemic is continuously evolving. We thus have taken the more recent knowledge into account to update the previous recommendations from the Leukemia Committee,” Jérémie Rouger-Gaudichon, MD, of Pediatric Hemato-Immuno-Oncology Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen (France), and colleagues wrote on behalf of the SFCE.

The updated recommendations are based on data collected in a real-time prospective survey among the 30 SFCE centers since April 2020. As of December 2020, 127 cases of COVID-19 were reported, most of them being enrolled in the PEDONCOVID study (NCT04433871) according to the report. Of these, eight patients required hospitalization in intensive care unit and one patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) died from ARDS with multiorgan failure. This confirms earlier reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be severe in some children with cancer and/or having hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), according to the report, which was published online in Bulletin du Cancer.

Recommendations

General recommendations were provided in the report, including the following:

- Test for SARS-CoV-2 (preferably by PCR or at least by immunological tests, on nasopharyngeal swab) before starting intensive induction chemotherapy or other intensive phase of treatment, for ALL patients, with or without symptoms.

- Delay systemic treatment if possible (e.g., absence of major hyperleukocytosis) in positive patients. During later phases, if patients test positive, tests should be repeated over time until negativity, especially before the beginning of an intensive course.

- Isolate any COVID-19–negative child or adolescent to allow treatment to continue (facial mask, social distancing, barrier measures, no contact with individuals suspected of COVID-19 or COVID-19–positive), in particular for patients to be allografted.

- Limit visitation to parents and potentially siblings in patients slated for HSCT and follow all necessary sanitary procedures for those visits.

The report provides a lengthy discussion of more detailed recommendations, including the following for first-line treatment of ALL:

- For patients with high-risk ALL, an individualized decision regarding transplantation and its timing should weigh the risks of transplantation in an epidemic context of COVID-19 against the risk linked to ALL.

- Minimizing hospital visits by the use of home blood tests and partial use of telemedicine may be considered.

- A physical examination should be performed regularly to avoid any delay in the diagnosis of treatment complications or relapse and preventative measures for SARS-CoV-2 should be applied in the home.

Patients with relapsed ALL may be at more risk from the effects of COVID-19 disease, according to the others, so for ALL patients receiving second-line or more treatment the recommendations include the following:

- Testing must be performed before starting a chemotherapy block, and postponing chemotherapy in case of positive test should be discussed in accordance with each specific situation and benefits/risks ratio regarding the leukemia.

- First-relapse patients should follow the INTREALL treatment protocol as much as possible and those who reach appropriate complete remission should be considered promptly for allogeneic transplantation, despite the pandemic.

- Second relapse and refractory relapses require testing and negative results for inclusion in phase I-II trials being conducted by most if not all academic or industrial promoters.

- The indication for treatment with CAR-T cells must be weighed with the center that would perform the procedure to determine the feasibility of performing all necessary procedures including apheresis and manufacturing.

In the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis during the treatment of ALL, discussions should occur with regard to stopping and/or postponing all chemotherapies, according to the severity of the ALL, the stage of treatment and the severity of clinical and/or radiological signs. In addition, any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment must be discussed with the infectious diseases team, according to the report.

“Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 infection appears nevertheless to be mild in most children with cancer/ALL. Thus, the main threat to the vast majority of children with ALL still remains the ALL itself. Long-term data including well-matched case-control studies will tell if treatment delays/modifications due to COVID-19 have impacted the outcome if children with ALL,” the authors stated. However, “despite extremely rapid advances obtained in less than one year, our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and its complications is still incomplete,” they concluded, adding that the recommendations will likely need to be updated within another few months.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

The main threat to the vast majority of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia still remains the ALL itself, according to updated recommendations released by the Leukemia Committee of the French Society for the Fight Against Cancers and Leukemias in Children and Adolescents (SFCE).

“The situation of the current COVID-19 pandemic is continuously evolving. We thus have taken the more recent knowledge into account to update the previous recommendations from the Leukemia Committee,” Jérémie Rouger-Gaudichon, MD, of Pediatric Hemato-Immuno-Oncology Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen (France), and colleagues wrote on behalf of the SFCE.

The updated recommendations are based on data collected in a real-time prospective survey among the 30 SFCE centers since April 2020. As of December 2020, 127 cases of COVID-19 were reported, most of them being enrolled in the PEDONCOVID study (NCT04433871) according to the report. Of these, eight patients required hospitalization in intensive care unit and one patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) died from ARDS with multiorgan failure. This confirms earlier reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be severe in some children with cancer and/or having hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), according to the report, which was published online in Bulletin du Cancer.

Recommendations

General recommendations were provided in the report, including the following:

- Test for SARS-CoV-2 (preferably by PCR or at least by immunological tests, on nasopharyngeal swab) before starting intensive induction chemotherapy or other intensive phase of treatment, for ALL patients, with or without symptoms.

- Delay systemic treatment if possible (e.g., absence of major hyperleukocytosis) in positive patients. During later phases, if patients test positive, tests should be repeated over time until negativity, especially before the beginning of an intensive course.

- Isolate any COVID-19–negative child or adolescent to allow treatment to continue (facial mask, social distancing, barrier measures, no contact with individuals suspected of COVID-19 or COVID-19–positive), in particular for patients to be allografted.

- Limit visitation to parents and potentially siblings in patients slated for HSCT and follow all necessary sanitary procedures for those visits.

The report provides a lengthy discussion of more detailed recommendations, including the following for first-line treatment of ALL:

- For patients with high-risk ALL, an individualized decision regarding transplantation and its timing should weigh the risks of transplantation in an epidemic context of COVID-19 against the risk linked to ALL.

- Minimizing hospital visits by the use of home blood tests and partial use of telemedicine may be considered.

- A physical examination should be performed regularly to avoid any delay in the diagnosis of treatment complications or relapse and preventative measures for SARS-CoV-2 should be applied in the home.

Patients with relapsed ALL may be at more risk from the effects of COVID-19 disease, according to the others, so for ALL patients receiving second-line or more treatment the recommendations include the following:

- Testing must be performed before starting a chemotherapy block, and postponing chemotherapy in case of positive test should be discussed in accordance with each specific situation and benefits/risks ratio regarding the leukemia.

- First-relapse patients should follow the INTREALL treatment protocol as much as possible and those who reach appropriate complete remission should be considered promptly for allogeneic transplantation, despite the pandemic.

- Second relapse and refractory relapses require testing and negative results for inclusion in phase I-II trials being conducted by most if not all academic or industrial promoters.

- The indication for treatment with CAR-T cells must be weighed with the center that would perform the procedure to determine the feasibility of performing all necessary procedures including apheresis and manufacturing.

In the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis during the treatment of ALL, discussions should occur with regard to stopping and/or postponing all chemotherapies, according to the severity of the ALL, the stage of treatment and the severity of clinical and/or radiological signs. In addition, any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment must be discussed with the infectious diseases team, according to the report.

“Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 infection appears nevertheless to be mild in most children with cancer/ALL. Thus, the main threat to the vast majority of children with ALL still remains the ALL itself. Long-term data including well-matched case-control studies will tell if treatment delays/modifications due to COVID-19 have impacted the outcome if children with ALL,” the authors stated. However, “despite extremely rapid advances obtained in less than one year, our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and its complications is still incomplete,” they concluded, adding that the recommendations will likely need to be updated within another few months.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

The main threat to the vast majority of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia still remains the ALL itself, according to updated recommendations released by the Leukemia Committee of the French Society for the Fight Against Cancers and Leukemias in Children and Adolescents (SFCE).

“The situation of the current COVID-19 pandemic is continuously evolving. We thus have taken the more recent knowledge into account to update the previous recommendations from the Leukemia Committee,” Jérémie Rouger-Gaudichon, MD, of Pediatric Hemato-Immuno-Oncology Unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Caen (France), and colleagues wrote on behalf of the SFCE.

The updated recommendations are based on data collected in a real-time prospective survey among the 30 SFCE centers since April 2020. As of December 2020, 127 cases of COVID-19 were reported, most of them being enrolled in the PEDONCOVID study (NCT04433871) according to the report. Of these, eight patients required hospitalization in intensive care unit and one patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) died from ARDS with multiorgan failure. This confirms earlier reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection can be severe in some children with cancer and/or having hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), according to the report, which was published online in Bulletin du Cancer.

Recommendations

General recommendations were provided in the report, including the following:

- Test for SARS-CoV-2 (preferably by PCR or at least by immunological tests, on nasopharyngeal swab) before starting intensive induction chemotherapy or other intensive phase of treatment, for ALL patients, with or without symptoms.

- Delay systemic treatment if possible (e.g., absence of major hyperleukocytosis) in positive patients. During later phases, if patients test positive, tests should be repeated over time until negativity, especially before the beginning of an intensive course.

- Isolate any COVID-19–negative child or adolescent to allow treatment to continue (facial mask, social distancing, barrier measures, no contact with individuals suspected of COVID-19 or COVID-19–positive), in particular for patients to be allografted.

- Limit visitation to parents and potentially siblings in patients slated for HSCT and follow all necessary sanitary procedures for those visits.

The report provides a lengthy discussion of more detailed recommendations, including the following for first-line treatment of ALL:

- For patients with high-risk ALL, an individualized decision regarding transplantation and its timing should weigh the risks of transplantation in an epidemic context of COVID-19 against the risk linked to ALL.

- Minimizing hospital visits by the use of home blood tests and partial use of telemedicine may be considered.

- A physical examination should be performed regularly to avoid any delay in the diagnosis of treatment complications or relapse and preventative measures for SARS-CoV-2 should be applied in the home.

Patients with relapsed ALL may be at more risk from the effects of COVID-19 disease, according to the others, so for ALL patients receiving second-line or more treatment the recommendations include the following:

- Testing must be performed before starting a chemotherapy block, and postponing chemotherapy in case of positive test should be discussed in accordance with each specific situation and benefits/risks ratio regarding the leukemia.

- First-relapse patients should follow the INTREALL treatment protocol as much as possible and those who reach appropriate complete remission should be considered promptly for allogeneic transplantation, despite the pandemic.

- Second relapse and refractory relapses require testing and negative results for inclusion in phase I-II trials being conducted by most if not all academic or industrial promoters.

- The indication for treatment with CAR-T cells must be weighed with the center that would perform the procedure to determine the feasibility of performing all necessary procedures including apheresis and manufacturing.

In the case of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis during the treatment of ALL, discussions should occur with regard to stopping and/or postponing all chemotherapies, according to the severity of the ALL, the stage of treatment and the severity of clinical and/or radiological signs. In addition, any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment must be discussed with the infectious diseases team, according to the report.

“Fortunately, SARS-CoV-2 infection appears nevertheless to be mild in most children with cancer/ALL. Thus, the main threat to the vast majority of children with ALL still remains the ALL itself. Long-term data including well-matched case-control studies will tell if treatment delays/modifications due to COVID-19 have impacted the outcome if children with ALL,” the authors stated. However, “despite extremely rapid advances obtained in less than one year, our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and its complications is still incomplete,” they concluded, adding that the recommendations will likely need to be updated within another few months.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM BULLETIN DU CANCER

Type 2 diabetes linked to increased risk for Parkinson’s

New analyses of both observational and genetic data have provided “convincing evidence” that type 2 diabetes is associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease.

“The fact that we see the same effects in both types of analysis separately makes it more likely that these results are real – that type 2 diabetes really is a driver of Parkinson’s disease risk,” Alastair Noyce, PhD, senior author of the new studies, said in an interview.

The two analyses are reported in one paper published online March 8 in the journal Movement Disorders.

Dr. Noyce, clinical senior lecturer in the preventive neurology unit at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, explained that his group is interested in risk factors for Parkinson’s disease, particularly those relevant at the population level and which might be modifiable.

“Several studies have looked at diabetes as a risk factor for Parkinson’s but very few have focused on type 2 diabetes, and, as this is such a growing health issue, we wanted to look at that in more detail,” he said.

The researchers performed two different analyses: a meta-analysis of observational studies investigating an association between type 2 diabetes and Parkinson’s; and a separate Mendelian randomization analysis of genetic data on the two conditions.

They found similar results in both studies, with the observational data suggesting type 2 diabetes was associated with a 21% increased risk for Parkinson’s disease and the genetic data suggesting an 8% increased risk. There were also hints that type 2 diabetes might also be associated with faster progression of Parkinson’s symptoms.

“I don’t think type 2 diabetes is a major cause of Parkinson’s, but it probably makes some contribution and may increase the risk of a more aggressive form of the condition,” Dr. Noyce said.

“I would say the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease attributable to type 2 diabetes may be similar to that of head injury or pesticide exposure, but it is important, as type 2 diabetes is very prevalent and is increasing,” he added. “As we see the growth in type 2 diabetes, this could lead to a later increase in Parkinson’s, which is already one of the fastest-growing diseases worldwide.”