User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Ten-day methotrexate pause after COVID vaccine booster enhances immunity against Omicron variant

People taking methotrexate for immunomodulatory diseases can skip one or two scheduled doses after they get an mRNA-based vaccine booster for COVID-19 and achieve a level of immunity against Omicron variants that’s comparable to people who aren’t immunosuppressed, a small observational cohort study from Germany reported.

“In general, the data suggest that pausing methotrexate is feasible, and it’s sufficient if the last dose occurs 1-3 days before the vaccination,” study coauthor Gerd Burmester, MD, a senior professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Medicine Berlin, told this news organization. “In pragmatic terms: pausing the methotrexate injection just twice after the vaccine is finished and, interestingly, not prior to the vaccination.”

The study, published online in RMD Open, included a statistical analysis that determined that a 10-day pause after the vaccination would be optimal, Dr. Burmester said.

Dr. Burmester and coauthors claimed this is the first study to evaluate the antibody response in patients on methotrexate against Omicron variants – in this study, variants BA.1 and BA.2 – after getting a COVID-19 mRNA booster. The study compared neutralizing serum activity of 50 patients taking methotrexate – 24 of whom continued treatments uninterrupted and 26 of whom paused treatments after getting a second booster – with 25 nonimmunosuppressed patients who served as controls. A total of 24% of the patients taking methotrexate received the mRNA-1273 vaccine while the entire control group received the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine.

The researchers used SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays to evaluate post-vaccination antibody levels.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other government health agencies have recommended that immunocompromised patients get a fourth COVID-19 vaccination. But these vaccines can be problematic in patients taking methotrexate, which was linked to a reduced response after the second and third doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Previous studies reported that pausing methotrexate for 10 or 14 days after the first two vaccinations improved the production of neutralizing antibodies. A 2022 study found that a 2-week pause after a booster increased antibody response against S1 RBD (receptor binding domain) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein about twofold. Another recently published study of mRNA vaccines found that taking methotrexate with either a biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug reduces the efficacy of a third (booster) shot of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in older adults but not younger patients with RA.

“Our study and also the other studies suggested that you can pause methotrexate treatment safely from a point of view of disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Burmester said. “If you do the pause just twice or once only, it doesn’t lead to significant flares.”

Study results

The study found that serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron BA.1 variant, measured as geometric mean 50% inhibitory serum dilution (ID50s), wasn’t significantly different between the methotrexate and the nonimmunosuppressed groups before getting their mRNA booster (P = .657). However, 4 weeks after getting the booster, the nonimmunosuppressed group had a 68-fold increase in antibody activity versus a 20-fold increase in the methotrexate patients. After 12 weeks, ID50s in both groups decreased by about half (P = .001).

The methotrexate patients who continued therapy after the booster had significantly lower neutralization against Omicron BA.1 at both 4 weeks and 12 weeks than did their counterparts who paused therapy, as well as control patients.

The results were very similar in the same group comparisons of the serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron BA.2 variant at 4 and 12 weeks after booster vaccination.

Expert commentary

This study is noteworthy because it used SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays to evaluate antibody levels, Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, professor of infectious disease and public health at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in the study, said. “A lot of studies don’t look at neutralizing antibody titers, and that’s really what we care about,” Dr. Winthrop said. “What we want are functional antibodies that are doing something, and the only way to do that is to test them.”

The study is “confirmatory” of other studies that call for pausing methotrexate after vaccination, Dr. Winthrop said, including a study he coauthored, and which the German researchers cited, that found pausing methotrexate for a week or so after the influenza vaccination in RA patients improved vaccine immunogenicity. He added that the findings with the early Omicron variants are important because the newest boosters target the later Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

“The bottom line is that when someone comes in for a COVID-19 vaccination, tell them to be off of methotrexate for 7-10 days,” Dr. Winthrop said. “This is for the booster, but it raises the question: If you go out to three, four, or five vaccinations, does this matter anymore? With the flu vaccine, most people are out to 10 or 15 boosters, and we haven’t seen any significant increase in disease flares.”

The study received funding from Medac, Gilead/Galapagos, and Friends and Sponsors of Berlin Charity. Dr. Burmester reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Winthrop is a research consultant to Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People taking methotrexate for immunomodulatory diseases can skip one or two scheduled doses after they get an mRNA-based vaccine booster for COVID-19 and achieve a level of immunity against Omicron variants that’s comparable to people who aren’t immunosuppressed, a small observational cohort study from Germany reported.

“In general, the data suggest that pausing methotrexate is feasible, and it’s sufficient if the last dose occurs 1-3 days before the vaccination,” study coauthor Gerd Burmester, MD, a senior professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Medicine Berlin, told this news organization. “In pragmatic terms: pausing the methotrexate injection just twice after the vaccine is finished and, interestingly, not prior to the vaccination.”

The study, published online in RMD Open, included a statistical analysis that determined that a 10-day pause after the vaccination would be optimal, Dr. Burmester said.

Dr. Burmester and coauthors claimed this is the first study to evaluate the antibody response in patients on methotrexate against Omicron variants – in this study, variants BA.1 and BA.2 – after getting a COVID-19 mRNA booster. The study compared neutralizing serum activity of 50 patients taking methotrexate – 24 of whom continued treatments uninterrupted and 26 of whom paused treatments after getting a second booster – with 25 nonimmunosuppressed patients who served as controls. A total of 24% of the patients taking methotrexate received the mRNA-1273 vaccine while the entire control group received the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine.

The researchers used SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays to evaluate post-vaccination antibody levels.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other government health agencies have recommended that immunocompromised patients get a fourth COVID-19 vaccination. But these vaccines can be problematic in patients taking methotrexate, which was linked to a reduced response after the second and third doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Previous studies reported that pausing methotrexate for 10 or 14 days after the first two vaccinations improved the production of neutralizing antibodies. A 2022 study found that a 2-week pause after a booster increased antibody response against S1 RBD (receptor binding domain) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein about twofold. Another recently published study of mRNA vaccines found that taking methotrexate with either a biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug reduces the efficacy of a third (booster) shot of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in older adults but not younger patients with RA.

“Our study and also the other studies suggested that you can pause methotrexate treatment safely from a point of view of disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Burmester said. “If you do the pause just twice or once only, it doesn’t lead to significant flares.”

Study results

The study found that serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron BA.1 variant, measured as geometric mean 50% inhibitory serum dilution (ID50s), wasn’t significantly different between the methotrexate and the nonimmunosuppressed groups before getting their mRNA booster (P = .657). However, 4 weeks after getting the booster, the nonimmunosuppressed group had a 68-fold increase in antibody activity versus a 20-fold increase in the methotrexate patients. After 12 weeks, ID50s in both groups decreased by about half (P = .001).

The methotrexate patients who continued therapy after the booster had significantly lower neutralization against Omicron BA.1 at both 4 weeks and 12 weeks than did their counterparts who paused therapy, as well as control patients.

The results were very similar in the same group comparisons of the serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron BA.2 variant at 4 and 12 weeks after booster vaccination.

Expert commentary

This study is noteworthy because it used SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays to evaluate antibody levels, Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, professor of infectious disease and public health at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in the study, said. “A lot of studies don’t look at neutralizing antibody titers, and that’s really what we care about,” Dr. Winthrop said. “What we want are functional antibodies that are doing something, and the only way to do that is to test them.”

The study is “confirmatory” of other studies that call for pausing methotrexate after vaccination, Dr. Winthrop said, including a study he coauthored, and which the German researchers cited, that found pausing methotrexate for a week or so after the influenza vaccination in RA patients improved vaccine immunogenicity. He added that the findings with the early Omicron variants are important because the newest boosters target the later Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

“The bottom line is that when someone comes in for a COVID-19 vaccination, tell them to be off of methotrexate for 7-10 days,” Dr. Winthrop said. “This is for the booster, but it raises the question: If you go out to three, four, or five vaccinations, does this matter anymore? With the flu vaccine, most people are out to 10 or 15 boosters, and we haven’t seen any significant increase in disease flares.”

The study received funding from Medac, Gilead/Galapagos, and Friends and Sponsors of Berlin Charity. Dr. Burmester reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Winthrop is a research consultant to Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People taking methotrexate for immunomodulatory diseases can skip one or two scheduled doses after they get an mRNA-based vaccine booster for COVID-19 and achieve a level of immunity against Omicron variants that’s comparable to people who aren’t immunosuppressed, a small observational cohort study from Germany reported.

“In general, the data suggest that pausing methotrexate is feasible, and it’s sufficient if the last dose occurs 1-3 days before the vaccination,” study coauthor Gerd Burmester, MD, a senior professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Medicine Berlin, told this news organization. “In pragmatic terms: pausing the methotrexate injection just twice after the vaccine is finished and, interestingly, not prior to the vaccination.”

The study, published online in RMD Open, included a statistical analysis that determined that a 10-day pause after the vaccination would be optimal, Dr. Burmester said.

Dr. Burmester and coauthors claimed this is the first study to evaluate the antibody response in patients on methotrexate against Omicron variants – in this study, variants BA.1 and BA.2 – after getting a COVID-19 mRNA booster. The study compared neutralizing serum activity of 50 patients taking methotrexate – 24 of whom continued treatments uninterrupted and 26 of whom paused treatments after getting a second booster – with 25 nonimmunosuppressed patients who served as controls. A total of 24% of the patients taking methotrexate received the mRNA-1273 vaccine while the entire control group received the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine.

The researchers used SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays to evaluate post-vaccination antibody levels.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other government health agencies have recommended that immunocompromised patients get a fourth COVID-19 vaccination. But these vaccines can be problematic in patients taking methotrexate, which was linked to a reduced response after the second and third doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Previous studies reported that pausing methotrexate for 10 or 14 days after the first two vaccinations improved the production of neutralizing antibodies. A 2022 study found that a 2-week pause after a booster increased antibody response against S1 RBD (receptor binding domain) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein about twofold. Another recently published study of mRNA vaccines found that taking methotrexate with either a biologic or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug reduces the efficacy of a third (booster) shot of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in older adults but not younger patients with RA.

“Our study and also the other studies suggested that you can pause methotrexate treatment safely from a point of view of disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Burmester said. “If you do the pause just twice or once only, it doesn’t lead to significant flares.”

Study results

The study found that serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron BA.1 variant, measured as geometric mean 50% inhibitory serum dilution (ID50s), wasn’t significantly different between the methotrexate and the nonimmunosuppressed groups before getting their mRNA booster (P = .657). However, 4 weeks after getting the booster, the nonimmunosuppressed group had a 68-fold increase in antibody activity versus a 20-fold increase in the methotrexate patients. After 12 weeks, ID50s in both groups decreased by about half (P = .001).

The methotrexate patients who continued therapy after the booster had significantly lower neutralization against Omicron BA.1 at both 4 weeks and 12 weeks than did their counterparts who paused therapy, as well as control patients.

The results were very similar in the same group comparisons of the serum neutralizing activity against the Omicron BA.2 variant at 4 and 12 weeks after booster vaccination.

Expert commentary

This study is noteworthy because it used SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assays to evaluate antibody levels, Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, professor of infectious disease and public health at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in the study, said. “A lot of studies don’t look at neutralizing antibody titers, and that’s really what we care about,” Dr. Winthrop said. “What we want are functional antibodies that are doing something, and the only way to do that is to test them.”

The study is “confirmatory” of other studies that call for pausing methotrexate after vaccination, Dr. Winthrop said, including a study he coauthored, and which the German researchers cited, that found pausing methotrexate for a week or so after the influenza vaccination in RA patients improved vaccine immunogenicity. He added that the findings with the early Omicron variants are important because the newest boosters target the later Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

“The bottom line is that when someone comes in for a COVID-19 vaccination, tell them to be off of methotrexate for 7-10 days,” Dr. Winthrop said. “This is for the booster, but it raises the question: If you go out to three, four, or five vaccinations, does this matter anymore? With the flu vaccine, most people are out to 10 or 15 boosters, and we haven’t seen any significant increase in disease flares.”

The study received funding from Medac, Gilead/Galapagos, and Friends and Sponsors of Berlin Charity. Dr. Burmester reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Winthrop is a research consultant to Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM RMD OPEN

Why the 5-day isolation period for COVID makes no sense

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

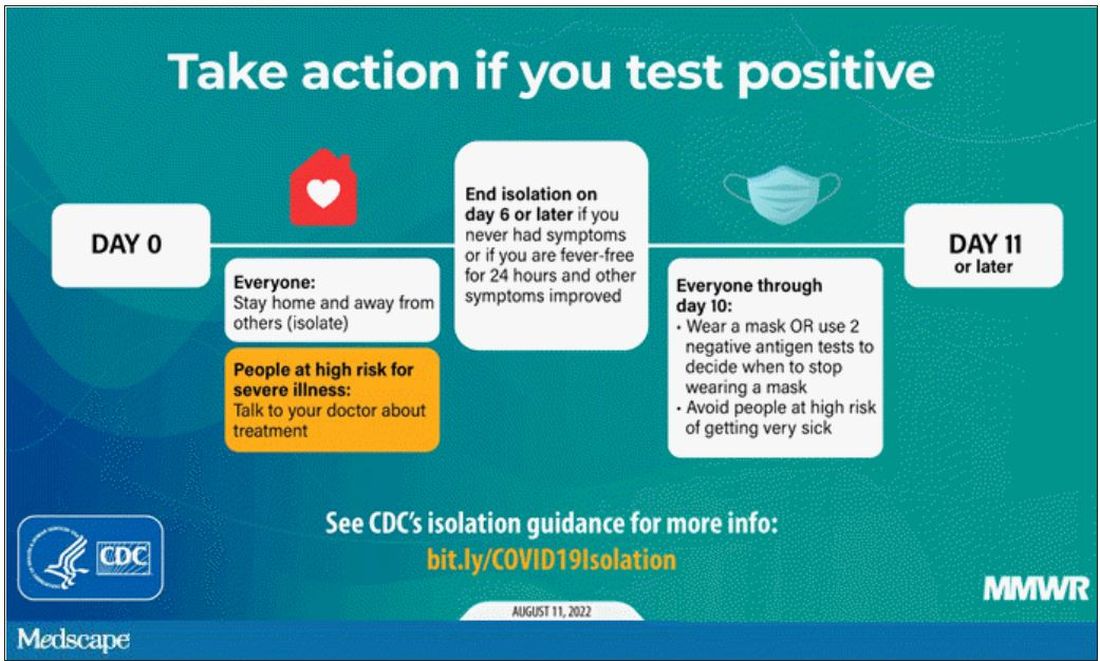

One of the more baffling decisions the CDC made during this pandemic was when they reduced the duration of isolation after a positive COVID test from 10 days to 5 days and did not require a negative antigen test to end isolation.

Multiple studies had suggested, after all, that positive antigen tests, while not perfect, were a decent proxy for infectivity. And if the purpose of isolation is to keep other community members safe, why not use a readily available test to know when it might be safe to go out in public again?

Also, 5 days just wasn’t that much time. Many individuals are symptomatic long after that point. Many people test positive long after that point. What exactly is the point of the 5-day isolation period?

We got some hard numbers this week to show just how good (or bad) an arbitrary-seeming 5-day isolation period is, thanks to this study from JAMA Network Open, which gives us a low-end estimate for the proportion of people who remain positive on antigen tests, which is to say infectious, after an isolation period.

This study estimates the low end of postisolation infectivity because of the study population: student athletes at an NCAA Division I school, which may or may not be Stanford. These athletes tested positive for COVID after having at least one dose of vaccine from January to May 2022. School protocol was to put the students in isolation for 7 days, at which time they could “test out” with a negative antigen test.

Put simply, these were healthy people. They were young. They were athletes. They were vaccinated. If anyone is going to have a brief, easy COVID course, it would be them. And they are doing at least a week of isolation, not 5 days.

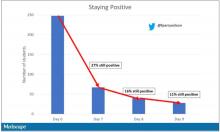

So – isolation for 7 days. Antigen testing on day 7. How many still tested positive? Of 248 individuals tested, 67 (27%) tested positive. One in four.

More than half of those positive on day 7 tested positive on day 8, and more than half of those tested positive again on day 9. By day 10, they were released from isolation without further testing.

So, right there .

There were some predictors of prolonged positivity.

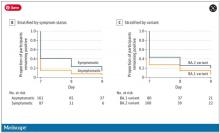

Symptomatic athletes were much more likely to test positive than asymptomatic athletes.

And the particular variant seemed to matter as well. In this time period, BA.1 and BA.2 were dominant, and it was pretty clear that BA.2 persisted longer than BA.1.

This brings me back to my original question: What is the point of the 5-day isolation period? On the basis of this study, you could imagine a guideline based on symptoms: Stay home until you feel better. You could imagine a guideline based on testing: Stay home until you test negative. A guideline based on time alone just doesn’t comport with the data. The benefit of policies based on symptoms or testing are obvious; some people would be out of isolation even before 5 days. But the downside, of course, is that some people would be stuck in isolation for much longer.

Maybe we should just say it. At this point, you could even imagine there being no recommendation at all – no isolation period. Like, you just stay home if you feel like you should stay home. I’m not entirely sure that such a policy would necessarily result in a greater number of infectious people out in the community.

In any case, as the arbitrariness of this particular 5-day isolation policy becomes more clear, the policy itself may be living on borrowed time.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

One of the more baffling decisions the CDC made during this pandemic was when they reduced the duration of isolation after a positive COVID test from 10 days to 5 days and did not require a negative antigen test to end isolation.

Multiple studies had suggested, after all, that positive antigen tests, while not perfect, were a decent proxy for infectivity. And if the purpose of isolation is to keep other community members safe, why not use a readily available test to know when it might be safe to go out in public again?

Also, 5 days just wasn’t that much time. Many individuals are symptomatic long after that point. Many people test positive long after that point. What exactly is the point of the 5-day isolation period?

We got some hard numbers this week to show just how good (or bad) an arbitrary-seeming 5-day isolation period is, thanks to this study from JAMA Network Open, which gives us a low-end estimate for the proportion of people who remain positive on antigen tests, which is to say infectious, after an isolation period.

This study estimates the low end of postisolation infectivity because of the study population: student athletes at an NCAA Division I school, which may or may not be Stanford. These athletes tested positive for COVID after having at least one dose of vaccine from January to May 2022. School protocol was to put the students in isolation for 7 days, at which time they could “test out” with a negative antigen test.

Put simply, these were healthy people. They were young. They were athletes. They were vaccinated. If anyone is going to have a brief, easy COVID course, it would be them. And they are doing at least a week of isolation, not 5 days.

So – isolation for 7 days. Antigen testing on day 7. How many still tested positive? Of 248 individuals tested, 67 (27%) tested positive. One in four.

More than half of those positive on day 7 tested positive on day 8, and more than half of those tested positive again on day 9. By day 10, they were released from isolation without further testing.

So, right there .

There were some predictors of prolonged positivity.

Symptomatic athletes were much more likely to test positive than asymptomatic athletes.

And the particular variant seemed to matter as well. In this time period, BA.1 and BA.2 were dominant, and it was pretty clear that BA.2 persisted longer than BA.1.

This brings me back to my original question: What is the point of the 5-day isolation period? On the basis of this study, you could imagine a guideline based on symptoms: Stay home until you feel better. You could imagine a guideline based on testing: Stay home until you test negative. A guideline based on time alone just doesn’t comport with the data. The benefit of policies based on symptoms or testing are obvious; some people would be out of isolation even before 5 days. But the downside, of course, is that some people would be stuck in isolation for much longer.

Maybe we should just say it. At this point, you could even imagine there being no recommendation at all – no isolation period. Like, you just stay home if you feel like you should stay home. I’m not entirely sure that such a policy would necessarily result in a greater number of infectious people out in the community.

In any case, as the arbitrariness of this particular 5-day isolation policy becomes more clear, the policy itself may be living on borrowed time.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

One of the more baffling decisions the CDC made during this pandemic was when they reduced the duration of isolation after a positive COVID test from 10 days to 5 days and did not require a negative antigen test to end isolation.

Multiple studies had suggested, after all, that positive antigen tests, while not perfect, were a decent proxy for infectivity. And if the purpose of isolation is to keep other community members safe, why not use a readily available test to know when it might be safe to go out in public again?

Also, 5 days just wasn’t that much time. Many individuals are symptomatic long after that point. Many people test positive long after that point. What exactly is the point of the 5-day isolation period?

We got some hard numbers this week to show just how good (or bad) an arbitrary-seeming 5-day isolation period is, thanks to this study from JAMA Network Open, which gives us a low-end estimate for the proportion of people who remain positive on antigen tests, which is to say infectious, after an isolation period.

This study estimates the low end of postisolation infectivity because of the study population: student athletes at an NCAA Division I school, which may or may not be Stanford. These athletes tested positive for COVID after having at least one dose of vaccine from January to May 2022. School protocol was to put the students in isolation for 7 days, at which time they could “test out” with a negative antigen test.

Put simply, these were healthy people. They were young. They were athletes. They were vaccinated. If anyone is going to have a brief, easy COVID course, it would be them. And they are doing at least a week of isolation, not 5 days.

So – isolation for 7 days. Antigen testing on day 7. How many still tested positive? Of 248 individuals tested, 67 (27%) tested positive. One in four.

More than half of those positive on day 7 tested positive on day 8, and more than half of those tested positive again on day 9. By day 10, they were released from isolation without further testing.

So, right there .

There were some predictors of prolonged positivity.

Symptomatic athletes were much more likely to test positive than asymptomatic athletes.

And the particular variant seemed to matter as well. In this time period, BA.1 and BA.2 were dominant, and it was pretty clear that BA.2 persisted longer than BA.1.

This brings me back to my original question: What is the point of the 5-day isolation period? On the basis of this study, you could imagine a guideline based on symptoms: Stay home until you feel better. You could imagine a guideline based on testing: Stay home until you test negative. A guideline based on time alone just doesn’t comport with the data. The benefit of policies based on symptoms or testing are obvious; some people would be out of isolation even before 5 days. But the downside, of course, is that some people would be stuck in isolation for much longer.

Maybe we should just say it. At this point, you could even imagine there being no recommendation at all – no isolation period. Like, you just stay home if you feel like you should stay home. I’m not entirely sure that such a policy would necessarily result in a greater number of infectious people out in the community.

In any case, as the arbitrariness of this particular 5-day isolation policy becomes more clear, the policy itself may be living on borrowed time.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaccine adherence hinges on improving science communication

“I’m not getting the vaccine. Nobody knows the long-term effects, and I heard that people are getting clots.”

We were screening patients at a low-cost clinic in Philadelphia for concerns surrounding social determinants of health. During one patient visit, in addition to concerns including housing, medication affordability, and transportation, we found that she had not received the COVID-19 vaccine, and we asked if she was interested in being immunized.

News reports have endlessly covered antivaccine sentiment, but this personal encounter hit home. From simple face masks to groundbreaking vaccines, we failed as physicians to encourage widespread uptake of health-protective measures despite strong scientific backing.

Large swaths of the public deny these tools’ importance or question their safety. This is ultimately rooted in the inability of community leaders and health care professionals to communicate with the public.

Science communication is inherently difficult. Scientists use complex language, and it is hard to evaluate the lay public’s baseline knowledge. Moreover, we are trained to speak with qualifications, encourage doubt, and accept change and evolution of fact. These qualities contrast the definitive messaging necessary in public settings. COVID-19 highlighted these gaps, where regardless of novel scientific solutions, poor communication led to a resistance to accept the tested scientific solution, which ultimately was the rate-limiting factor for overcoming the virus.

As directors of Physician Executive Leadership, an organization that trains future physicians at Thomas Jefferson University to tackle emerging health care issues, we hosted Paul Offit, MD, a national media figure and vaccine advocate. Dr. Offit shared his personal growth during the pandemic, from being abruptly thrown into the spotlight to eventually honing his communication skills. Dr. Offit discussed the challenges of sharing medical knowledge with laypeople and adaptations that are necessary. We found this transformative, realizing the importance of science communication training early in medical education.

Emphasizing the humanities and building soft skills will improve outcomes and benefit broader society by producing physician-leaders in public health and policy. We hope to improve our own communication skills and work in medical education to incorporate similar training into education paradigms for future students.

As seen in our patient interaction, strong science alone will not drive patient adherence; instead, we must work at personal and system levels to induce change. Physicians have a unique opportunity to generate trust and guide evidence-based policy. We must communicate, whether one-on-one with patients, or to millions of viewers via media or policymaker settings. We hope to not only be doctors, but to be advocates, leaders, and trusted advisers for the public.

Mr. Kieran and Mr. Shah are second-year medical students at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia. Neither disclosed any relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I’m not getting the vaccine. Nobody knows the long-term effects, and I heard that people are getting clots.”

We were screening patients at a low-cost clinic in Philadelphia for concerns surrounding social determinants of health. During one patient visit, in addition to concerns including housing, medication affordability, and transportation, we found that she had not received the COVID-19 vaccine, and we asked if she was interested in being immunized.

News reports have endlessly covered antivaccine sentiment, but this personal encounter hit home. From simple face masks to groundbreaking vaccines, we failed as physicians to encourage widespread uptake of health-protective measures despite strong scientific backing.

Large swaths of the public deny these tools’ importance or question their safety. This is ultimately rooted in the inability of community leaders and health care professionals to communicate with the public.

Science communication is inherently difficult. Scientists use complex language, and it is hard to evaluate the lay public’s baseline knowledge. Moreover, we are trained to speak with qualifications, encourage doubt, and accept change and evolution of fact. These qualities contrast the definitive messaging necessary in public settings. COVID-19 highlighted these gaps, where regardless of novel scientific solutions, poor communication led to a resistance to accept the tested scientific solution, which ultimately was the rate-limiting factor for overcoming the virus.

As directors of Physician Executive Leadership, an organization that trains future physicians at Thomas Jefferson University to tackle emerging health care issues, we hosted Paul Offit, MD, a national media figure and vaccine advocate. Dr. Offit shared his personal growth during the pandemic, from being abruptly thrown into the spotlight to eventually honing his communication skills. Dr. Offit discussed the challenges of sharing medical knowledge with laypeople and adaptations that are necessary. We found this transformative, realizing the importance of science communication training early in medical education.

Emphasizing the humanities and building soft skills will improve outcomes and benefit broader society by producing physician-leaders in public health and policy. We hope to improve our own communication skills and work in medical education to incorporate similar training into education paradigms for future students.

As seen in our patient interaction, strong science alone will not drive patient adherence; instead, we must work at personal and system levels to induce change. Physicians have a unique opportunity to generate trust and guide evidence-based policy. We must communicate, whether one-on-one with patients, or to millions of viewers via media or policymaker settings. We hope to not only be doctors, but to be advocates, leaders, and trusted advisers for the public.

Mr. Kieran and Mr. Shah are second-year medical students at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia. Neither disclosed any relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I’m not getting the vaccine. Nobody knows the long-term effects, and I heard that people are getting clots.”

We were screening patients at a low-cost clinic in Philadelphia for concerns surrounding social determinants of health. During one patient visit, in addition to concerns including housing, medication affordability, and transportation, we found that she had not received the COVID-19 vaccine, and we asked if she was interested in being immunized.

News reports have endlessly covered antivaccine sentiment, but this personal encounter hit home. From simple face masks to groundbreaking vaccines, we failed as physicians to encourage widespread uptake of health-protective measures despite strong scientific backing.

Large swaths of the public deny these tools’ importance or question their safety. This is ultimately rooted in the inability of community leaders and health care professionals to communicate with the public.

Science communication is inherently difficult. Scientists use complex language, and it is hard to evaluate the lay public’s baseline knowledge. Moreover, we are trained to speak with qualifications, encourage doubt, and accept change and evolution of fact. These qualities contrast the definitive messaging necessary in public settings. COVID-19 highlighted these gaps, where regardless of novel scientific solutions, poor communication led to a resistance to accept the tested scientific solution, which ultimately was the rate-limiting factor for overcoming the virus.

As directors of Physician Executive Leadership, an organization that trains future physicians at Thomas Jefferson University to tackle emerging health care issues, we hosted Paul Offit, MD, a national media figure and vaccine advocate. Dr. Offit shared his personal growth during the pandemic, from being abruptly thrown into the spotlight to eventually honing his communication skills. Dr. Offit discussed the challenges of sharing medical knowledge with laypeople and adaptations that are necessary. We found this transformative, realizing the importance of science communication training early in medical education.

Emphasizing the humanities and building soft skills will improve outcomes and benefit broader society by producing physician-leaders in public health and policy. We hope to improve our own communication skills and work in medical education to incorporate similar training into education paradigms for future students.

As seen in our patient interaction, strong science alone will not drive patient adherence; instead, we must work at personal and system levels to induce change. Physicians have a unique opportunity to generate trust and guide evidence-based policy. We must communicate, whether one-on-one with patients, or to millions of viewers via media or policymaker settings. We hope to not only be doctors, but to be advocates, leaders, and trusted advisers for the public.

Mr. Kieran and Mr. Shah are second-year medical students at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia. Neither disclosed any relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Iron deficiency may protect against bacterial pneumonia

Patients with iron deficiency anemia who developed bacterial pneumonia showed improved outcomes compared to those without iron deficiency anemia, based on data from more than 450,000 individuals in the National Inpatient Sample.

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide, and can lead to anemia, but iron also has been identified as essential to the survival and growth of pathogenic organisms, Mubarak Yusuf, MD, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

However, the specific impact of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) on outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute bacterial infections has not been explored, said Dr. Yusuf, a third-year internal medicine resident at Lincoln Medical Center in New York.

In the study, Dr. Yusuf and colleagues reviewed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database for 2016-2019. They identified 452,040 adults aged 18 or older with a primary diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia based on ICD-10 codes. Patients with a principal diagnosis other than bacterial pneumonia were excluded.

Of these, 5.5% had a secondary diagnosis of IDA. The mean age of the study population was similar between the IDA and non-IDA groups (68 years) and racial distribution was similar, with a White majority of approximately 77%. Slightly more patients in the IDA group were women (58.5% vs. 51.6%) and this difference was statistically significant (P < .00001). Most of the patients (94.6%) in the IDA group had at least three comorbidities, as did 78.1% of the non-IDA group.

The primary outcome was mortality, and the overall mortality in the study population was 2.89%. Although the mortality percentage was higher in the IDA group compared to the non-IDA group (3.25% vs. 2.87%), “when we adjusted for confounders, we noticed a decreased odds of mortality in the IDA group” with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.74 (P = .001), Dr. Yusuf said.

In addition, secondary outcomes of septic shock, acute respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest were lower in the IDA group in a regression analysis, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.71, 0.78, and 0.57, respectively.

The mean length of stay was 0.3 days higher in the IDA group, and the researchers found a nonsignificant increase in total hospital costs of $402.5 for IDA patients compared to those without IDA, said Dr. Yusuf.

The take-home message from the study is actually a question to the clinician, Dr. Yusuf said. “Should you consider a delay in treatment [of iron deficiency anemia] if the patient is not symptomatic?” he asked.

More research is needed to investigate the improved outcomes in the iron deficient population, but the large sample size supports an association that is worth exploring, he concluded.

“The findings of this research may suggest a protective effect of iron deficiency in acute bacterial pneumonia,” Dr. Yusuf said in a press release accompanying the meeting presentation. “More research is needed to elucidate the improved outcomes found in this population, but this research may lead clinicians to consider a delay in treatment of nonsymptomatic iron deficiency in acute bacterial infection,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Patients with iron deficiency anemia who developed bacterial pneumonia showed improved outcomes compared to those without iron deficiency anemia, based on data from more than 450,000 individuals in the National Inpatient Sample.

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide, and can lead to anemia, but iron also has been identified as essential to the survival and growth of pathogenic organisms, Mubarak Yusuf, MD, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

However, the specific impact of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) on outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute bacterial infections has not been explored, said Dr. Yusuf, a third-year internal medicine resident at Lincoln Medical Center in New York.

In the study, Dr. Yusuf and colleagues reviewed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database for 2016-2019. They identified 452,040 adults aged 18 or older with a primary diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia based on ICD-10 codes. Patients with a principal diagnosis other than bacterial pneumonia were excluded.

Of these, 5.5% had a secondary diagnosis of IDA. The mean age of the study population was similar between the IDA and non-IDA groups (68 years) and racial distribution was similar, with a White majority of approximately 77%. Slightly more patients in the IDA group were women (58.5% vs. 51.6%) and this difference was statistically significant (P < .00001). Most of the patients (94.6%) in the IDA group had at least three comorbidities, as did 78.1% of the non-IDA group.

The primary outcome was mortality, and the overall mortality in the study population was 2.89%. Although the mortality percentage was higher in the IDA group compared to the non-IDA group (3.25% vs. 2.87%), “when we adjusted for confounders, we noticed a decreased odds of mortality in the IDA group” with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.74 (P = .001), Dr. Yusuf said.

In addition, secondary outcomes of septic shock, acute respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest were lower in the IDA group in a regression analysis, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.71, 0.78, and 0.57, respectively.

The mean length of stay was 0.3 days higher in the IDA group, and the researchers found a nonsignificant increase in total hospital costs of $402.5 for IDA patients compared to those without IDA, said Dr. Yusuf.

The take-home message from the study is actually a question to the clinician, Dr. Yusuf said. “Should you consider a delay in treatment [of iron deficiency anemia] if the patient is not symptomatic?” he asked.

More research is needed to investigate the improved outcomes in the iron deficient population, but the large sample size supports an association that is worth exploring, he concluded.

“The findings of this research may suggest a protective effect of iron deficiency in acute bacterial pneumonia,” Dr. Yusuf said in a press release accompanying the meeting presentation. “More research is needed to elucidate the improved outcomes found in this population, but this research may lead clinicians to consider a delay in treatment of nonsymptomatic iron deficiency in acute bacterial infection,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Patients with iron deficiency anemia who developed bacterial pneumonia showed improved outcomes compared to those without iron deficiency anemia, based on data from more than 450,000 individuals in the National Inpatient Sample.

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide, and can lead to anemia, but iron also has been identified as essential to the survival and growth of pathogenic organisms, Mubarak Yusuf, MD, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

However, the specific impact of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) on outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute bacterial infections has not been explored, said Dr. Yusuf, a third-year internal medicine resident at Lincoln Medical Center in New York.

In the study, Dr. Yusuf and colleagues reviewed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database for 2016-2019. They identified 452,040 adults aged 18 or older with a primary diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia based on ICD-10 codes. Patients with a principal diagnosis other than bacterial pneumonia were excluded.

Of these, 5.5% had a secondary diagnosis of IDA. The mean age of the study population was similar between the IDA and non-IDA groups (68 years) and racial distribution was similar, with a White majority of approximately 77%. Slightly more patients in the IDA group were women (58.5% vs. 51.6%) and this difference was statistically significant (P < .00001). Most of the patients (94.6%) in the IDA group had at least three comorbidities, as did 78.1% of the non-IDA group.

The primary outcome was mortality, and the overall mortality in the study population was 2.89%. Although the mortality percentage was higher in the IDA group compared to the non-IDA group (3.25% vs. 2.87%), “when we adjusted for confounders, we noticed a decreased odds of mortality in the IDA group” with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.74 (P = .001), Dr. Yusuf said.

In addition, secondary outcomes of septic shock, acute respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest were lower in the IDA group in a regression analysis, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.71, 0.78, and 0.57, respectively.

The mean length of stay was 0.3 days higher in the IDA group, and the researchers found a nonsignificant increase in total hospital costs of $402.5 for IDA patients compared to those without IDA, said Dr. Yusuf.

The take-home message from the study is actually a question to the clinician, Dr. Yusuf said. “Should you consider a delay in treatment [of iron deficiency anemia] if the patient is not symptomatic?” he asked.

More research is needed to investigate the improved outcomes in the iron deficient population, but the large sample size supports an association that is worth exploring, he concluded.

“The findings of this research may suggest a protective effect of iron deficiency in acute bacterial pneumonia,” Dr. Yusuf said in a press release accompanying the meeting presentation. “More research is needed to elucidate the improved outcomes found in this population, but this research may lead clinicians to consider a delay in treatment of nonsymptomatic iron deficiency in acute bacterial infection,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM CHEST 2022

Reminder that COVID-19 and cancer can be a deadly combo

A new study underscores the importance of COVID-19 and regular COVID-19 testing among adults with a recent cancer diagnosis.

The Indiana statewide study, conducted at the beginning of the pandemic, found that

“This analysis provides additional empirical evidence on the magnitude of risk to patients with cancer whose immune systems are often weakened either by the disease or treatment,” the study team wrote.

The study was published online in JMIR Cancer.

Although evidence has consistently revealed similar findings, the risk of death among unvaccinated people with cancer and COVID-19 has not been nearly as high in previous studies, lead author Brian E. Dixon, PhD, MBA, with Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health, Indianapolis, said in a statement. Previous studies from China, for instance, reported a two- to threefold greater risk of all-cause mortality among unvaccinated adults with cancer and COVID-19.

A potential reason for this discrepancy, Dr. Dixon noted, is that earlier studies were “generally smaller and made calculations based on data from a single cancer center or health system.”

Another reason is testing for COVID-19 early in the pandemic was limited to symptomatic individuals who may have had more severe infections, possibly leading to an overestimate of the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, cancer, and all-cause mortality.

In the current analysis, researchers used electronic health records linked to Indiana’s statewide SARS-CoV-2 testing database and state vital records to evaluate the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and all-cause mortality among 41,924 adults newly diagnosed with cancer between Jan. 1, 2019, and Dec. 31, 2020.

Most people with cancer were White (78.4%) and about half were male. At the time of diagnosis, 17% had one comorbid condition and about 10% had two or more. Most patients had breast cancer (14%), prostate cancer (13%), or melanoma (13%).

During the study period, 2,894 patients (7%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

In multivariate adjusted analysis, the risk of death among those newly diagnosed with cancer increased by 91% (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.91) during the first year of the pandemic before vaccines were available, compared with the year before (January 2019 to Jan. 14, 2020).

During the pandemic period, the risk of death was roughly threefold higher among adults 65 years old and older, compared with adults 18-44 years old (aHR, 3.35).

When looking at the time from a cancer diagnosis to SARS-CoV-2 infection, infection was associated with an almost sevenfold increase in all-cause mortality (aHR, 6.91). Adults 65 years old and older had an almost threefold increased risk of dying, compared with their younger peers (aHR, 2.74).

Dr. Dixon and colleagues also observed an increased risk of death in men with cancer and COVID, compared with women (aHR, 1.23) and those with at least two comorbid conditions versus none (aHR, 2.12). In addition, the risk of dying was 9% higher among Indiana’s rural population than urban dwellers.

Compared with other cancer types, individuals with lung cancer and other digestive cancers had the highest risk of death after SARS-CoV-2 infection (aHR, 1.45 and 1.80, respectively).

“Our findings highlight the increased risk of death for adult cancer patients who test positive for COVID and underscore the importance to cancer patients – including those in remission – of vaccinations, boosters, and regular COVID testing,” Dr. Dixon commented.

“Our results should encourage individuals diagnosed with cancer not only to take preventive action, but also to expeditiously seek out treatments available in the marketplace should they test positive for COVID,” he added.

Support for the study was provided by Indiana University Simon Cancer Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study underscores the importance of COVID-19 and regular COVID-19 testing among adults with a recent cancer diagnosis.

The Indiana statewide study, conducted at the beginning of the pandemic, found that

“This analysis provides additional empirical evidence on the magnitude of risk to patients with cancer whose immune systems are often weakened either by the disease or treatment,” the study team wrote.

The study was published online in JMIR Cancer.

Although evidence has consistently revealed similar findings, the risk of death among unvaccinated people with cancer and COVID-19 has not been nearly as high in previous studies, lead author Brian E. Dixon, PhD, MBA, with Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health, Indianapolis, said in a statement. Previous studies from China, for instance, reported a two- to threefold greater risk of all-cause mortality among unvaccinated adults with cancer and COVID-19.

A potential reason for this discrepancy, Dr. Dixon noted, is that earlier studies were “generally smaller and made calculations based on data from a single cancer center or health system.”

Another reason is testing for COVID-19 early in the pandemic was limited to symptomatic individuals who may have had more severe infections, possibly leading to an overestimate of the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, cancer, and all-cause mortality.

In the current analysis, researchers used electronic health records linked to Indiana’s statewide SARS-CoV-2 testing database and state vital records to evaluate the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and all-cause mortality among 41,924 adults newly diagnosed with cancer between Jan. 1, 2019, and Dec. 31, 2020.

Most people with cancer were White (78.4%) and about half were male. At the time of diagnosis, 17% had one comorbid condition and about 10% had two or more. Most patients had breast cancer (14%), prostate cancer (13%), or melanoma (13%).

During the study period, 2,894 patients (7%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

In multivariate adjusted analysis, the risk of death among those newly diagnosed with cancer increased by 91% (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.91) during the first year of the pandemic before vaccines were available, compared with the year before (January 2019 to Jan. 14, 2020).

During the pandemic period, the risk of death was roughly threefold higher among adults 65 years old and older, compared with adults 18-44 years old (aHR, 3.35).

When looking at the time from a cancer diagnosis to SARS-CoV-2 infection, infection was associated with an almost sevenfold increase in all-cause mortality (aHR, 6.91). Adults 65 years old and older had an almost threefold increased risk of dying, compared with their younger peers (aHR, 2.74).

Dr. Dixon and colleagues also observed an increased risk of death in men with cancer and COVID, compared with women (aHR, 1.23) and those with at least two comorbid conditions versus none (aHR, 2.12). In addition, the risk of dying was 9% higher among Indiana’s rural population than urban dwellers.

Compared with other cancer types, individuals with lung cancer and other digestive cancers had the highest risk of death after SARS-CoV-2 infection (aHR, 1.45 and 1.80, respectively).

“Our findings highlight the increased risk of death for adult cancer patients who test positive for COVID and underscore the importance to cancer patients – including those in remission – of vaccinations, boosters, and regular COVID testing,” Dr. Dixon commented.

“Our results should encourage individuals diagnosed with cancer not only to take preventive action, but also to expeditiously seek out treatments available in the marketplace should they test positive for COVID,” he added.

Support for the study was provided by Indiana University Simon Cancer Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study underscores the importance of COVID-19 and regular COVID-19 testing among adults with a recent cancer diagnosis.

The Indiana statewide study, conducted at the beginning of the pandemic, found that

“This analysis provides additional empirical evidence on the magnitude of risk to patients with cancer whose immune systems are often weakened either by the disease or treatment,” the study team wrote.

The study was published online in JMIR Cancer.

Although evidence has consistently revealed similar findings, the risk of death among unvaccinated people with cancer and COVID-19 has not been nearly as high in previous studies, lead author Brian E. Dixon, PhD, MBA, with Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health, Indianapolis, said in a statement. Previous studies from China, for instance, reported a two- to threefold greater risk of all-cause mortality among unvaccinated adults with cancer and COVID-19.

A potential reason for this discrepancy, Dr. Dixon noted, is that earlier studies were “generally smaller and made calculations based on data from a single cancer center or health system.”

Another reason is testing for COVID-19 early in the pandemic was limited to symptomatic individuals who may have had more severe infections, possibly leading to an overestimate of the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, cancer, and all-cause mortality.

In the current analysis, researchers used electronic health records linked to Indiana’s statewide SARS-CoV-2 testing database and state vital records to evaluate the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and all-cause mortality among 41,924 adults newly diagnosed with cancer between Jan. 1, 2019, and Dec. 31, 2020.

Most people with cancer were White (78.4%) and about half were male. At the time of diagnosis, 17% had one comorbid condition and about 10% had two or more. Most patients had breast cancer (14%), prostate cancer (13%), or melanoma (13%).

During the study period, 2,894 patients (7%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

In multivariate adjusted analysis, the risk of death among those newly diagnosed with cancer increased by 91% (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.91) during the first year of the pandemic before vaccines were available, compared with the year before (January 2019 to Jan. 14, 2020).

During the pandemic period, the risk of death was roughly threefold higher among adults 65 years old and older, compared with adults 18-44 years old (aHR, 3.35).

When looking at the time from a cancer diagnosis to SARS-CoV-2 infection, infection was associated with an almost sevenfold increase in all-cause mortality (aHR, 6.91). Adults 65 years old and older had an almost threefold increased risk of dying, compared with their younger peers (aHR, 2.74).

Dr. Dixon and colleagues also observed an increased risk of death in men with cancer and COVID, compared with women (aHR, 1.23) and those with at least two comorbid conditions versus none (aHR, 2.12). In addition, the risk of dying was 9% higher among Indiana’s rural population than urban dwellers.

Compared with other cancer types, individuals with lung cancer and other digestive cancers had the highest risk of death after SARS-CoV-2 infection (aHR, 1.45 and 1.80, respectively).

“Our findings highlight the increased risk of death for adult cancer patients who test positive for COVID and underscore the importance to cancer patients – including those in remission – of vaccinations, boosters, and regular COVID testing,” Dr. Dixon commented.

“Our results should encourage individuals diagnosed with cancer not only to take preventive action, but also to expeditiously seek out treatments available in the marketplace should they test positive for COVID,” he added.

Support for the study was provided by Indiana University Simon Cancer Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JMIR CANCER

This brain surgery was BYOS: Bring your own saxophone

Tumor vs. saxophone: The surgical grudge match

Brain surgery is a notoriously difficult task. There’s a reason we say, “Well, at least it’s not brain surgery” when we’re trying to convince someone that a task isn’t that tough. Make one wrong incision, cut the wrong neuron, and it’s goodbye higher cognitive function. And most people appreciate thinking. Crazy, right?

One would imagine that the act of brain surgery would become even more difficult when the patient brings his saxophone and plays it randomly throughout the operation. It’s a hospital, after all, not a jazz club. Patients don’t get to play musical instruments during other surgeries. Why should brain surgery patients get special treatment?

As it turns out, the musical performance was actually quite helpful. A man in Italy had a brain tumor in a particularly complex area, and he’s left-handed, which apparently makes the brain’s neural pathways much more complicated. Plus, he insisted that he retain his musical ability after the surgery. So he and his medical team had a crazy thought: Why not play the saxophone throughout the surgery? After all, according to head surgeon Christian Brogna, MD, playing an instrument means you understand music, which tests many higher cognitive functions such as coordination, mathematics, and memory.

And so, at various points throughout the 9-hour surgery, the patient played his saxophone for his doctors. Doing so allowed the surgeons to map the patient’s brain in a more complete and personalized fashion. With that extra knowledge, they were able to successfully remove the tumor while maintaining the patient’s musical ability, and the patient was discharged on Oct. 13, just 3 days after his operation.

While we’re happy the patient recovered, we do have to question his choice of music. During the surgery, he played the theme to the 1970 movie “Love Story” and the Italian national anthem. Perfectly fine pieces, no doubt, but the saxophone solo in “Jungleland” exists. And we could listen to that for 9 hours straight. In fact, we do that every Friday in the LOTME office.

Basketball has the Big Dance. Mosquitoes get the Big Sniff

In this week’s installment of our seemingly never-ending series, “Mosquitoes and the scientists who love them,” we visit The Rockefeller University in New York, where the olfactory capabilities of Aedes Aegypti – the primary vector species for Zika, dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya – became the subject of a round robin–style tournament.

First things first, though. If you’re going to test mosquito noses, you have to give them something to smell. The researchers enrolled eight humans who were willing to wear nylon stockings on their forearms for 6 hours a day for multiple days. “Over the next few years, the researchers tested the nylons against each other in all possible pairings,” Leslie B. Vosshall, PhD, and associates said in a statement from the university. In other words, mosquito March Madness.

Nylons from different participants were hooked up in pairs to an olfactometer assay consisting of a plexiglass chamber divided into two tubes, each ending in a box that held a stocking. The mosquitoes were placed in the main chamber and observed as they flew down the tubes toward one stocking or the other.

Eventually, the “winner” of the “tournament” was Subject 33. And no, we don’t know why there was a Subject 33 since the study involved only eight participants. We do know that the nylons worn by Subject 33 were “four times more attractive to the mosquitoes than the next most-attractive study participant, and an astonishing 100 times more appealing than the least attractive, Subject 19,” according to the written statement.

Chemical analysis identified 50 molecular compounds that were elevated in the sebum of the high-attracting participants, and eventually the investigators discovered that mosquito magnets produced carboxylic acids at much higher levels than the less-attractive volunteers.

We could go on about the research team genetically engineering mosquitoes without odor receptors, but we have to save something for later. Tune in again next week for another exciting episode of “Mosquitoes and the scientists who love them.”

Are women better with words?

Men vs. Women is probably the oldest argument in the book, but there may now be movement. Researchers have been able not only to shift the advantage toward women, but also to use that knowledge to medical advantage.

When it comes to the matter of words and remembering them, women apparently have men beat. The margin is small, said lead author Marco Hirnstein, PhD, of the University of Bergen, Norway, but, after performing a meta-analysis of 168 published studies and PhD theses involving more than 350,000 participants, it’s pretty clear. The research supports women’s advantage over men in recall, verbal fluency (categorical and phonemic), and recognition.

So how is this information useful from a medical standpoint?

Dr. Hirnstein and colleagues suggested that this information can help in interpreting diagnostic assessment results. The example given was dementia diagnosis. Since women are underdiagnosed because their baseline exceeds average while men are overdiagnosed, taking gender and performance into account could clear up or catch cases that might otherwise slip through the cracks.

Now, let’s just put this part of the debate to rest and take this not only as a win for women but for science as well.

Tumor vs. saxophone: The surgical grudge match

Brain surgery is a notoriously difficult task. There’s a reason we say, “Well, at least it’s not brain surgery” when we’re trying to convince someone that a task isn’t that tough. Make one wrong incision, cut the wrong neuron, and it’s goodbye higher cognitive function. And most people appreciate thinking. Crazy, right?

One would imagine that the act of brain surgery would become even more difficult when the patient brings his saxophone and plays it randomly throughout the operation. It’s a hospital, after all, not a jazz club. Patients don’t get to play musical instruments during other surgeries. Why should brain surgery patients get special treatment?

As it turns out, the musical performance was actually quite helpful. A man in Italy had a brain tumor in a particularly complex area, and he’s left-handed, which apparently makes the brain’s neural pathways much more complicated. Plus, he insisted that he retain his musical ability after the surgery. So he and his medical team had a crazy thought: Why not play the saxophone throughout the surgery? After all, according to head surgeon Christian Brogna, MD, playing an instrument means you understand music, which tests many higher cognitive functions such as coordination, mathematics, and memory.

And so, at various points throughout the 9-hour surgery, the patient played his saxophone for his doctors. Doing so allowed the surgeons to map the patient’s brain in a more complete and personalized fashion. With that extra knowledge, they were able to successfully remove the tumor while maintaining the patient’s musical ability, and the patient was discharged on Oct. 13, just 3 days after his operation.

While we’re happy the patient recovered, we do have to question his choice of music. During the surgery, he played the theme to the 1970 movie “Love Story” and the Italian national anthem. Perfectly fine pieces, no doubt, but the saxophone solo in “Jungleland” exists. And we could listen to that for 9 hours straight. In fact, we do that every Friday in the LOTME office.

Basketball has the Big Dance. Mosquitoes get the Big Sniff

In this week’s installment of our seemingly never-ending series, “Mosquitoes and the scientists who love them,” we visit The Rockefeller University in New York, where the olfactory capabilities of Aedes Aegypti – the primary vector species for Zika, dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya – became the subject of a round robin–style tournament.

First things first, though. If you’re going to test mosquito noses, you have to give them something to smell. The researchers enrolled eight humans who were willing to wear nylon stockings on their forearms for 6 hours a day for multiple days. “Over the next few years, the researchers tested the nylons against each other in all possible pairings,” Leslie B. Vosshall, PhD, and associates said in a statement from the university. In other words, mosquito March Madness.

Nylons from different participants were hooked up in pairs to an olfactometer assay consisting of a plexiglass chamber divided into two tubes, each ending in a box that held a stocking. The mosquitoes were placed in the main chamber and observed as they flew down the tubes toward one stocking or the other.

Eventually, the “winner” of the “tournament” was Subject 33. And no, we don’t know why there was a Subject 33 since the study involved only eight participants. We do know that the nylons worn by Subject 33 were “four times more attractive to the mosquitoes than the next most-attractive study participant, and an astonishing 100 times more appealing than the least attractive, Subject 19,” according to the written statement.

Chemical analysis identified 50 molecular compounds that were elevated in the sebum of the high-attracting participants, and eventually the investigators discovered that mosquito magnets produced carboxylic acids at much higher levels than the less-attractive volunteers.

We could go on about the research team genetically engineering mosquitoes without odor receptors, but we have to save something for later. Tune in again next week for another exciting episode of “Mosquitoes and the scientists who love them.”

Are women better with words?

Men vs. Women is probably the oldest argument in the book, but there may now be movement. Researchers have been able not only to shift the advantage toward women, but also to use that knowledge to medical advantage.

When it comes to the matter of words and remembering them, women apparently have men beat. The margin is small, said lead author Marco Hirnstein, PhD, of the University of Bergen, Norway, but, after performing a meta-analysis of 168 published studies and PhD theses involving more than 350,000 participants, it’s pretty clear. The research supports women’s advantage over men in recall, verbal fluency (categorical and phonemic), and recognition.

So how is this information useful from a medical standpoint?

Dr. Hirnstein and colleagues suggested that this information can help in interpreting diagnostic assessment results. The example given was dementia diagnosis. Since women are underdiagnosed because their baseline exceeds average while men are overdiagnosed, taking gender and performance into account could clear up or catch cases that might otherwise slip through the cracks.

Now, let’s just put this part of the debate to rest and take this not only as a win for women but for science as well.

Tumor vs. saxophone: The surgical grudge match

Brain surgery is a notoriously difficult task. There’s a reason we say, “Well, at least it’s not brain surgery” when we’re trying to convince someone that a task isn’t that tough. Make one wrong incision, cut the wrong neuron, and it’s goodbye higher cognitive function. And most people appreciate thinking. Crazy, right?

One would imagine that the act of brain surgery would become even more difficult when the patient brings his saxophone and plays it randomly throughout the operation. It’s a hospital, after all, not a jazz club. Patients don’t get to play musical instruments during other surgeries. Why should brain surgery patients get special treatment?

As it turns out, the musical performance was actually quite helpful. A man in Italy had a brain tumor in a particularly complex area, and he’s left-handed, which apparently makes the brain’s neural pathways much more complicated. Plus, he insisted that he retain his musical ability after the surgery. So he and his medical team had a crazy thought: Why not play the saxophone throughout the surgery? After all, according to head surgeon Christian Brogna, MD, playing an instrument means you understand music, which tests many higher cognitive functions such as coordination, mathematics, and memory.

And so, at various points throughout the 9-hour surgery, the patient played his saxophone for his doctors. Doing so allowed the surgeons to map the patient’s brain in a more complete and personalized fashion. With that extra knowledge, they were able to successfully remove the tumor while maintaining the patient’s musical ability, and the patient was discharged on Oct. 13, just 3 days after his operation.

While we’re happy the patient recovered, we do have to question his choice of music. During the surgery, he played the theme to the 1970 movie “Love Story” and the Italian national anthem. Perfectly fine pieces, no doubt, but the saxophone solo in “Jungleland” exists. And we could listen to that for 9 hours straight. In fact, we do that every Friday in the LOTME office.

Basketball has the Big Dance. Mosquitoes get the Big Sniff

In this week’s installment of our seemingly never-ending series, “Mosquitoes and the scientists who love them,” we visit The Rockefeller University in New York, where the olfactory capabilities of Aedes Aegypti – the primary vector species for Zika, dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya – became the subject of a round robin–style tournament.

First things first, though. If you’re going to test mosquito noses, you have to give them something to smell. The researchers enrolled eight humans who were willing to wear nylon stockings on their forearms for 6 hours a day for multiple days. “Over the next few years, the researchers tested the nylons against each other in all possible pairings,” Leslie B. Vosshall, PhD, and associates said in a statement from the university. In other words, mosquito March Madness.

Nylons from different participants were hooked up in pairs to an olfactometer assay consisting of a plexiglass chamber divided into two tubes, each ending in a box that held a stocking. The mosquitoes were placed in the main chamber and observed as they flew down the tubes toward one stocking or the other.

Eventually, the “winner” of the “tournament” was Subject 33. And no, we don’t know why there was a Subject 33 since the study involved only eight participants. We do know that the nylons worn by Subject 33 were “four times more attractive to the mosquitoes than the next most-attractive study participant, and an astonishing 100 times more appealing than the least attractive, Subject 19,” according to the written statement.

Chemical analysis identified 50 molecular compounds that were elevated in the sebum of the high-attracting participants, and eventually the investigators discovered that mosquito magnets produced carboxylic acids at much higher levels than the less-attractive volunteers.

We could go on about the research team genetically engineering mosquitoes without odor receptors, but we have to save something for later. Tune in again next week for another exciting episode of “Mosquitoes and the scientists who love them.”

Are women better with words?

Men vs. Women is probably the oldest argument in the book, but there may now be movement. Researchers have been able not only to shift the advantage toward women, but also to use that knowledge to medical advantage.

When it comes to the matter of words and remembering them, women apparently have men beat. The margin is small, said lead author Marco Hirnstein, PhD, of the University of Bergen, Norway, but, after performing a meta-analysis of 168 published studies and PhD theses involving more than 350,000 participants, it’s pretty clear. The research supports women’s advantage over men in recall, verbal fluency (categorical and phonemic), and recognition.

So how is this information useful from a medical standpoint?

Dr. Hirnstein and colleagues suggested that this information can help in interpreting diagnostic assessment results. The example given was dementia diagnosis. Since women are underdiagnosed because their baseline exceeds average while men are overdiagnosed, taking gender and performance into account could clear up or catch cases that might otherwise slip through the cracks.

Now, let’s just put this part of the debate to rest and take this not only as a win for women but for science as well.

People of color more likely to be hospitalized for influenza, CDC report finds

Black Americans are 80% more likely to be hospitalized for the flu, compared with White Americans, according to new federal data.

Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults in the United States also have had lower influenza vaccination rates, compared with their White counterparts, since 2010, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed in a report.

The inequalities are the result of barriers to care, distrust of the medical system, and misinformation, the report said.

“We have many of the tools we need to address inequities and flu vaccination coverage and outcomes,” said CDC Acting Principal Deputy Director Debra Houry, MD, MPH, in a press call; “however, we must acknowledge that inequities in access to care continue to exist. To improve vaccine uptake, we must address the root causes of these ongoing disparities.”