User login

Dermatoporosis in Older Adults: A Condition That Requires Holistic, Creative Management

WASHINGTON — and conveys the skin’s vulnerability to serious medical complications, said Adam Friedman, MD, at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient.

Key features of dermatoporosis include atrophic skin, solar purpura, white pseudoscars, easily acquired skin lacerations and tears, bruises, and delayed healing. “We’re going to see more of this, and it will more and more be a chief complaint of patients,” said Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, and co-chair of the meeting. GWU hosted the conference, describing it as a first-of-its-kind meeting dedicated to improving dermatologic care for older adults.

Dermatoporosis was described in the literature in 2007 by dermatologists at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. “It is not only a cosmetic problem,” Dr. Friedman said. “This is a medical problem ... which can absolutely lead to comorbidities [such as deep dissecting hematomas] that are a huge strain on the healthcare system.”

Dermatologists can meet the moment with holistic, creative combination treatment and counseling approaches aimed at improving the mechanical strength of skin and preventing potential complications in older patients, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting.

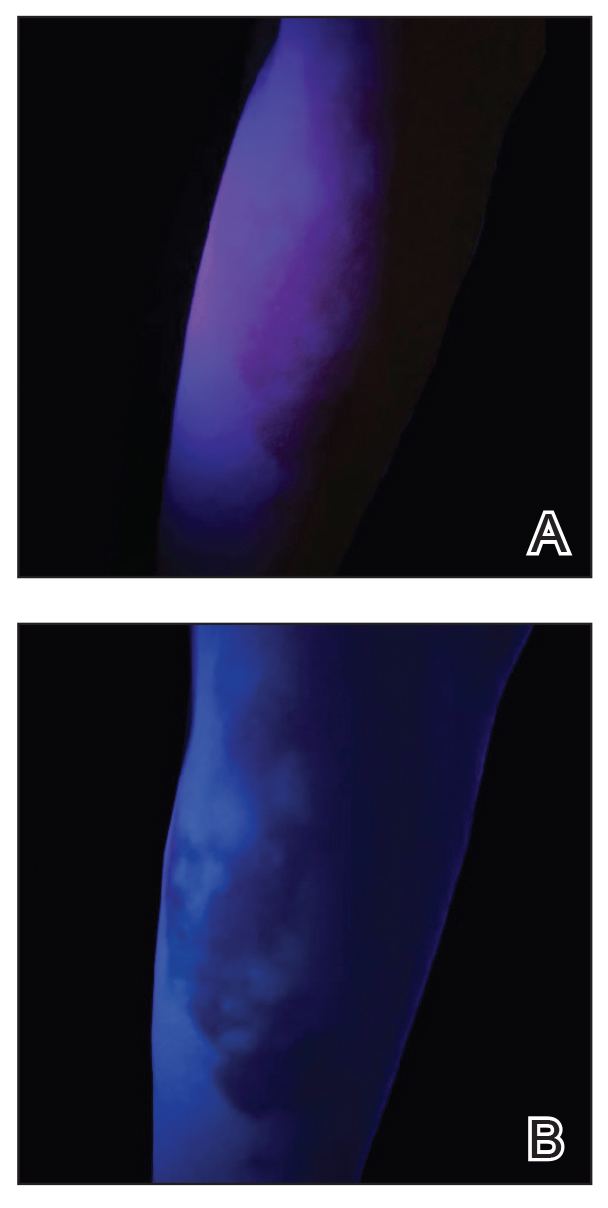

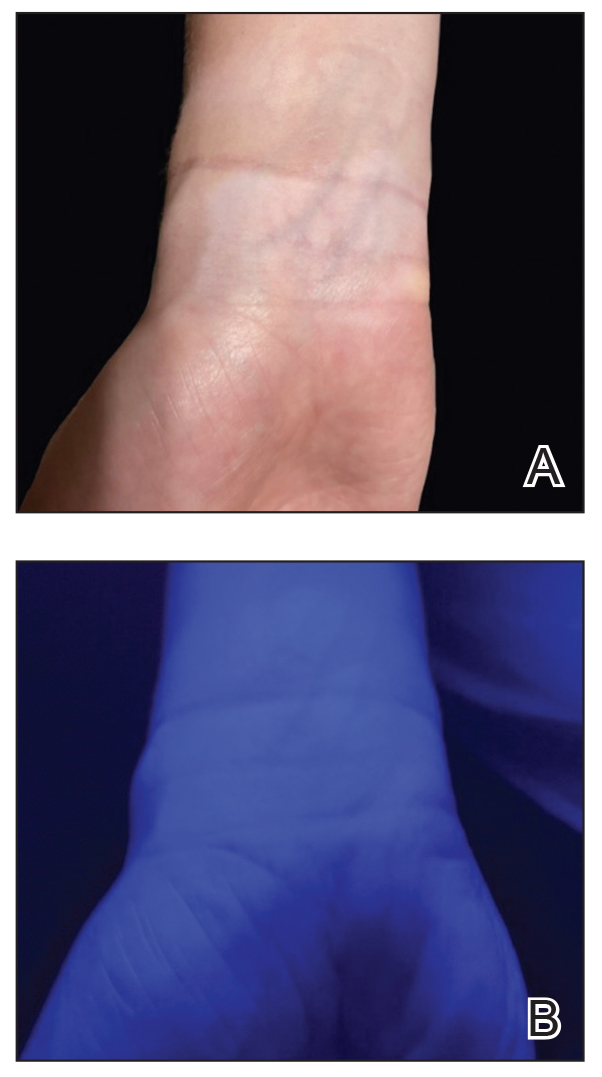

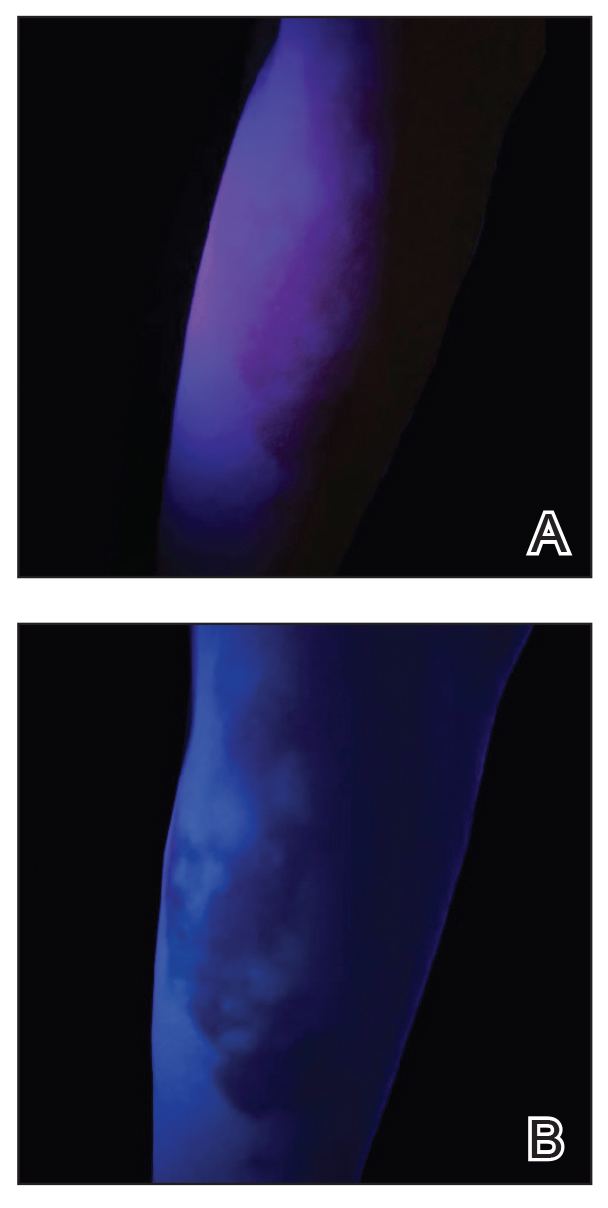

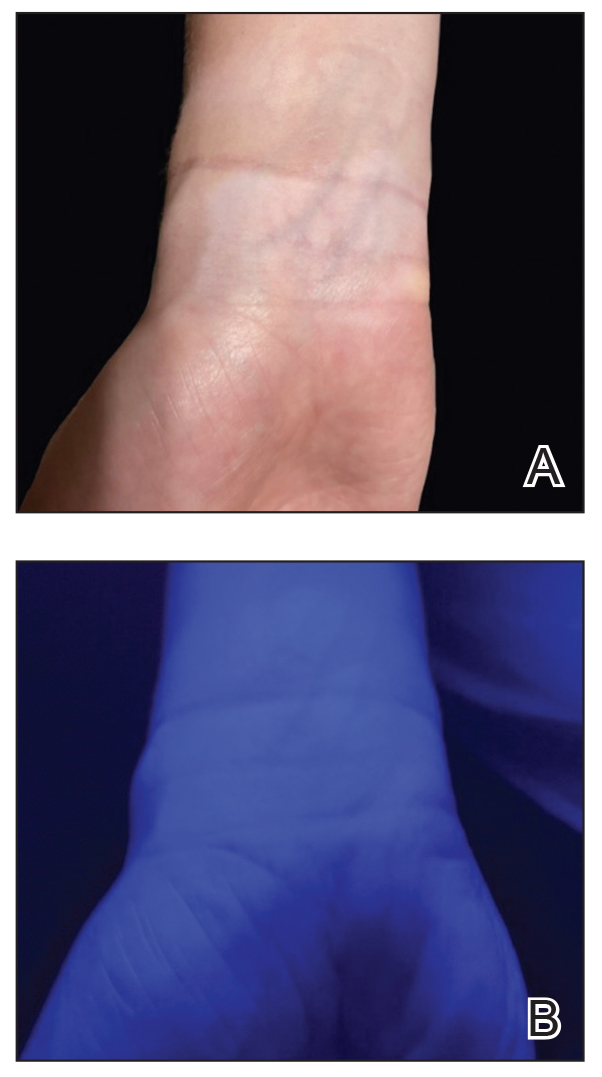

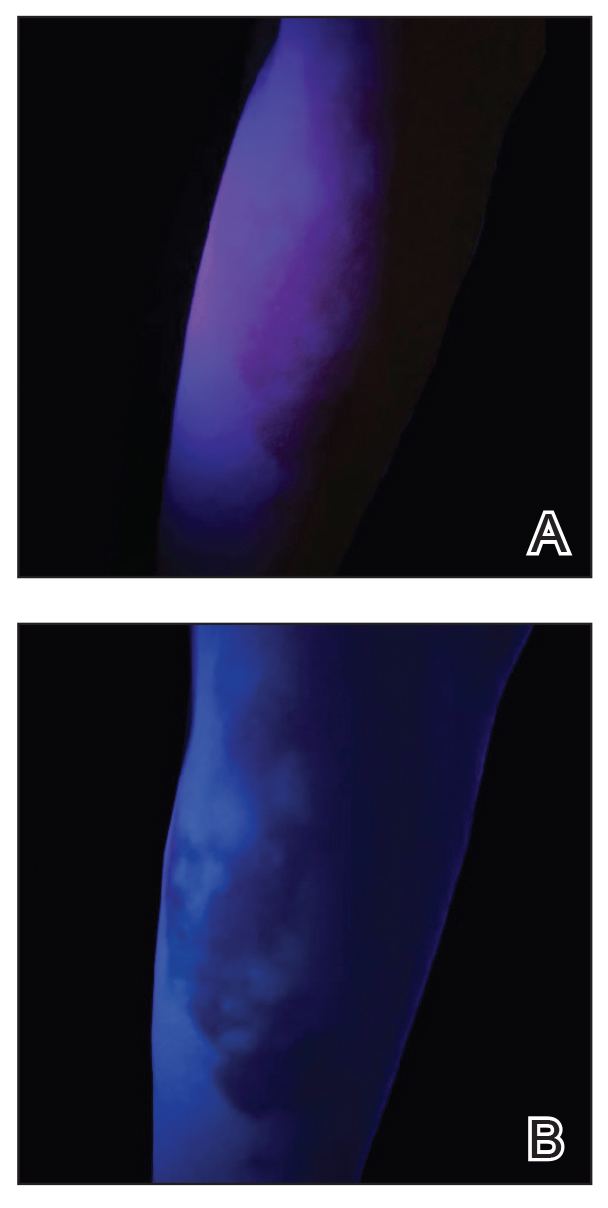

He described the case of a 76-year-old woman who presented with dermatoporosis on her arms involving pronounced skin atrophy, solar purpura, and a small covered laceration. “This was a patient who was both devastated by the appearance” and impacted by the pain and burden of dressing frequent wounds, said Dr. Friedman, who is also the director of the Residency Program, of Translational Research, and of Supportive Oncodermatology, all within the Department of Dermatology at GWU.

With 11 months of topical treatment that included daily application of calcipotriene 0.05% ointment and nightly application of tazarotene 0.045% lotion and oral supplementation with 1000-mg vitamin C twice daily and 1000-mg citrus bioflavonoid complex daily, as well as no changes to the medications she took for various comorbidities, the solar purpura improved significantly and “we made a huge difference in the integrity of her skin,” he said.

Dr. Friedman also described this case in a recently published article in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology titled “What’s Old Is New: An Emerging Focus on Dermatoporosis”.

Likely Pathophysiology

Advancing age and chronic ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure are the chief drivers of dermatoporosis. In addition to UVA and UVB light, other secondary drivers include genetic susceptibility, topical and systematic corticosteroid use, and anticoagulant treatment.

Its pathogenesis is not well described in the literature but is easy to envision, Dr. Friedman said. For one, both advancing age and exposure to UV light lead to a reduction in hygroscopic glycosaminoglycans, including hyaluronate (HA), and the impact of this diminishment is believed to go “beyond [the loss of] buoyancy,” he noted. Researchers have “been showing these are not just water-loving molecules, they also have some biologic properties” relating to keratinocyte production and epidermal turnover that appear to be intricately linked to the pathogenesis of dermatoporosis.

HAs have been shown to interact with the cell surface receptor CD44 to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation, and low levels of CD44 have been reported in skin with dermatoporosis compared with a younger control population. (A newly characterized organelle, the hyaluronosome, serves as an HA factory and contains CD44 and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, Dr. Friedman noted. Inadequate functioning may be involved in skin atrophy.)

Advancing age also brings an increase in matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)–1, –2, and –3, which are “the demolition workers of the skin,” and downregulation of a tissue inhibitor of MMPs, he said.

Adding insult to injury, dermis-penetrating UVA also activates MMPs, “obliterating collagen and elastin.” UVB generates DNA photoproducts, including oxidative stress and damaging skin cell DNA. “That UV light induces breakdown [of the skin] through different mechanisms and inhibits buildup is a simple concept I think our patients can understand,” Dr. Friedman said.

Multifaceted Treatment

For an older adult, “there is never a wrong time to start sun-protective measures” to prevent or try to halt the progression of dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman said, noting that “UV radiation is an immunosuppressant, so there are many good reasons to start” if the adult is not already taking measures on a regular basis.

Potential treatments for the syndrome of dermatoporosis are backed by few clinical studies, but dermatologists are skilled at translating the use of products from one disease state to another based on understandings of pathophysiology and mechanistic pathways, Dr. Friedman commented in an interview after the meeting.

For instance, “from decades of research, we know what retinoids will do to the skin,” he said in the interview. “We know they will turn on collagen-1 and -3 genes in the skin, and that they will increase the production of glycosaminoglycans ... By understanding the biology, we can translate this to dermatoporosis.” These changes were demonstrated, for instance, in a small study of topical retinol in older adults.

Studies of topical alpha hydroxy acid (AHA), moreover, have demonstrated epidermal thickening and firmness, and “some studies show they can limit steroid-induced atrophy,” Dr. Friedman said at the meeting. “And things like lactic acid and urea are super accessible.”

Topical dehydroepiandrosterone is backed by even less data than retinoids or AHAs are, “but it’s still something to consider” as part of a multimechanistic approach to dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman shared, noting that a small study demonstrated beneficial effects on epidermal atrophy in aging skin.

The use of vitamin D analogues such as calcipotriene, which is approved for the treatment of psoriasis, may also be promising. “One concept is that [vitamin D analogues] increase calcium concentrations in the epidermis, and calcium is so central to keratinocyte differentiation” and epidermal function that calcipotriene in combination with topical steroid therapy has been shown to limit skin atrophy, he noted.

Nutritionally, low protein intake is a known problem in the older population and is associated with increased skin fragility and poorer healing. From a prevention and treatment standpoint, therefore, patients can be counseled to be attentive to their diets, Dr. Friedman said. Experts have recommended a higher protein intake for older adults than for younger adults; in 2013, an international group recommended a protein intake of 1-1.5 g/kg/d for healthy older adults and more for those with acute or chronic illness.

“Patients love talking about diet and skin disease ... and they love over-the-counter nutraceuticals as well because they want something natural,” Dr. Friedman said. “I like using bioflavonoids in combination with vitamin C, which can be effective especially for solar purpura.”

A 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involving 67 patients with purpura associated with aging found a 50% reduction in purpura lesions among those took a particular citrus bioflavonoid blend twice daily. “I thought this was a pretty well-done study,” he said, noting that patient self-assessment and investigator global assessment were utilized.

Skin Injury and Wound Prevention

In addition to recommending gentle skin cleansers and daily moisturizing, dermatologists should talk to their older patients with dermatoporosis about their home environments. “What is it like? Is there furniture with sharp edges?” Dr. Friedman advised. If so, could they use sleeves or protectors on their arms or legs “to protect against injury?”

In a later meeting session about lower-extremity wounds on geriatric patients, Michael Stempel, DPM, assistant professor of medicine and surgery and chief of podiatry at GWU, said that he was happy to hear the term dermatoporosis being used because like diabetes, it’s a risk factor for developing lower-extremity wounds and poor wound healing.

He shared the case of an older woman with dermatoporosis who “tripped and skinned her knee against a step and then self-treated it for over a month by pouring hydrogen peroxide over it and letting air get to it.” The wound developed into “full-thickness tissue loss,” said Dr. Stempel, also medical director of the Wound Healing and Limb Preservation Center at GWU Hospital.

Misperceptions are common among older patients about how a simple wound should be managed; for instance, the adage “just let it get air” is not uncommon. This makes anticipatory guidance about basic wound care — such as the importance of a moist and occlusive environment and the safe use of hydrogen peroxide — especially important for patients with dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman commented after the meeting.

Dermatoporosis is quantifiable, Dr. Friedman said during the meeting, with a scoring system having been developed by the researchers in Switzerland who originally coined the term. Its use in practice is unnecessary, but its existence is “nice to share with patients who feel bothered because oftentimes, patients feel it’s been dismissed by other providers,” he said. “Telling your patients there’s an actual name for their problem, and that there are ways to quantify and measure changes over time, is validating.”

Its recognition as a medical condition, Dr. Friedman added, also enables the dermatologist to bring it up and counsel appropriately — without a patient feeling shame — when it is identified in the context of a skin excision, treatment of a primary inflammatory skin disease, or management of another dermatologic problem.

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for L’Oréal, La Roche-Posay, Galderma, and other companies; a speaker for Regeneron/Sanofi, Incyte, BMD, and Janssen; and has grants from Pfizer, Lilly, Incyte, and other companies. Dr. Stempel reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON — and conveys the skin’s vulnerability to serious medical complications, said Adam Friedman, MD, at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient.

Key features of dermatoporosis include atrophic skin, solar purpura, white pseudoscars, easily acquired skin lacerations and tears, bruises, and delayed healing. “We’re going to see more of this, and it will more and more be a chief complaint of patients,” said Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, and co-chair of the meeting. GWU hosted the conference, describing it as a first-of-its-kind meeting dedicated to improving dermatologic care for older adults.

Dermatoporosis was described in the literature in 2007 by dermatologists at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. “It is not only a cosmetic problem,” Dr. Friedman said. “This is a medical problem ... which can absolutely lead to comorbidities [such as deep dissecting hematomas] that are a huge strain on the healthcare system.”

Dermatologists can meet the moment with holistic, creative combination treatment and counseling approaches aimed at improving the mechanical strength of skin and preventing potential complications in older patients, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting.

He described the case of a 76-year-old woman who presented with dermatoporosis on her arms involving pronounced skin atrophy, solar purpura, and a small covered laceration. “This was a patient who was both devastated by the appearance” and impacted by the pain and burden of dressing frequent wounds, said Dr. Friedman, who is also the director of the Residency Program, of Translational Research, and of Supportive Oncodermatology, all within the Department of Dermatology at GWU.

With 11 months of topical treatment that included daily application of calcipotriene 0.05% ointment and nightly application of tazarotene 0.045% lotion and oral supplementation with 1000-mg vitamin C twice daily and 1000-mg citrus bioflavonoid complex daily, as well as no changes to the medications she took for various comorbidities, the solar purpura improved significantly and “we made a huge difference in the integrity of her skin,” he said.

Dr. Friedman also described this case in a recently published article in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology titled “What’s Old Is New: An Emerging Focus on Dermatoporosis”.

Likely Pathophysiology

Advancing age and chronic ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure are the chief drivers of dermatoporosis. In addition to UVA and UVB light, other secondary drivers include genetic susceptibility, topical and systematic corticosteroid use, and anticoagulant treatment.

Its pathogenesis is not well described in the literature but is easy to envision, Dr. Friedman said. For one, both advancing age and exposure to UV light lead to a reduction in hygroscopic glycosaminoglycans, including hyaluronate (HA), and the impact of this diminishment is believed to go “beyond [the loss of] buoyancy,” he noted. Researchers have “been showing these are not just water-loving molecules, they also have some biologic properties” relating to keratinocyte production and epidermal turnover that appear to be intricately linked to the pathogenesis of dermatoporosis.

HAs have been shown to interact with the cell surface receptor CD44 to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation, and low levels of CD44 have been reported in skin with dermatoporosis compared with a younger control population. (A newly characterized organelle, the hyaluronosome, serves as an HA factory and contains CD44 and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, Dr. Friedman noted. Inadequate functioning may be involved in skin atrophy.)

Advancing age also brings an increase in matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)–1, –2, and –3, which are “the demolition workers of the skin,” and downregulation of a tissue inhibitor of MMPs, he said.

Adding insult to injury, dermis-penetrating UVA also activates MMPs, “obliterating collagen and elastin.” UVB generates DNA photoproducts, including oxidative stress and damaging skin cell DNA. “That UV light induces breakdown [of the skin] through different mechanisms and inhibits buildup is a simple concept I think our patients can understand,” Dr. Friedman said.

Multifaceted Treatment

For an older adult, “there is never a wrong time to start sun-protective measures” to prevent or try to halt the progression of dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman said, noting that “UV radiation is an immunosuppressant, so there are many good reasons to start” if the adult is not already taking measures on a regular basis.

Potential treatments for the syndrome of dermatoporosis are backed by few clinical studies, but dermatologists are skilled at translating the use of products from one disease state to another based on understandings of pathophysiology and mechanistic pathways, Dr. Friedman commented in an interview after the meeting.

For instance, “from decades of research, we know what retinoids will do to the skin,” he said in the interview. “We know they will turn on collagen-1 and -3 genes in the skin, and that they will increase the production of glycosaminoglycans ... By understanding the biology, we can translate this to dermatoporosis.” These changes were demonstrated, for instance, in a small study of topical retinol in older adults.

Studies of topical alpha hydroxy acid (AHA), moreover, have demonstrated epidermal thickening and firmness, and “some studies show they can limit steroid-induced atrophy,” Dr. Friedman said at the meeting. “And things like lactic acid and urea are super accessible.”

Topical dehydroepiandrosterone is backed by even less data than retinoids or AHAs are, “but it’s still something to consider” as part of a multimechanistic approach to dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman shared, noting that a small study demonstrated beneficial effects on epidermal atrophy in aging skin.

The use of vitamin D analogues such as calcipotriene, which is approved for the treatment of psoriasis, may also be promising. “One concept is that [vitamin D analogues] increase calcium concentrations in the epidermis, and calcium is so central to keratinocyte differentiation” and epidermal function that calcipotriene in combination with topical steroid therapy has been shown to limit skin atrophy, he noted.

Nutritionally, low protein intake is a known problem in the older population and is associated with increased skin fragility and poorer healing. From a prevention and treatment standpoint, therefore, patients can be counseled to be attentive to their diets, Dr. Friedman said. Experts have recommended a higher protein intake for older adults than for younger adults; in 2013, an international group recommended a protein intake of 1-1.5 g/kg/d for healthy older adults and more for those with acute or chronic illness.

“Patients love talking about diet and skin disease ... and they love over-the-counter nutraceuticals as well because they want something natural,” Dr. Friedman said. “I like using bioflavonoids in combination with vitamin C, which can be effective especially for solar purpura.”

A 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involving 67 patients with purpura associated with aging found a 50% reduction in purpura lesions among those took a particular citrus bioflavonoid blend twice daily. “I thought this was a pretty well-done study,” he said, noting that patient self-assessment and investigator global assessment were utilized.

Skin Injury and Wound Prevention

In addition to recommending gentle skin cleansers and daily moisturizing, dermatologists should talk to their older patients with dermatoporosis about their home environments. “What is it like? Is there furniture with sharp edges?” Dr. Friedman advised. If so, could they use sleeves or protectors on their arms or legs “to protect against injury?”

In a later meeting session about lower-extremity wounds on geriatric patients, Michael Stempel, DPM, assistant professor of medicine and surgery and chief of podiatry at GWU, said that he was happy to hear the term dermatoporosis being used because like diabetes, it’s a risk factor for developing lower-extremity wounds and poor wound healing.

He shared the case of an older woman with dermatoporosis who “tripped and skinned her knee against a step and then self-treated it for over a month by pouring hydrogen peroxide over it and letting air get to it.” The wound developed into “full-thickness tissue loss,” said Dr. Stempel, also medical director of the Wound Healing and Limb Preservation Center at GWU Hospital.

Misperceptions are common among older patients about how a simple wound should be managed; for instance, the adage “just let it get air” is not uncommon. This makes anticipatory guidance about basic wound care — such as the importance of a moist and occlusive environment and the safe use of hydrogen peroxide — especially important for patients with dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman commented after the meeting.

Dermatoporosis is quantifiable, Dr. Friedman said during the meeting, with a scoring system having been developed by the researchers in Switzerland who originally coined the term. Its use in practice is unnecessary, but its existence is “nice to share with patients who feel bothered because oftentimes, patients feel it’s been dismissed by other providers,” he said. “Telling your patients there’s an actual name for their problem, and that there are ways to quantify and measure changes over time, is validating.”

Its recognition as a medical condition, Dr. Friedman added, also enables the dermatologist to bring it up and counsel appropriately — without a patient feeling shame — when it is identified in the context of a skin excision, treatment of a primary inflammatory skin disease, or management of another dermatologic problem.

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for L’Oréal, La Roche-Posay, Galderma, and other companies; a speaker for Regeneron/Sanofi, Incyte, BMD, and Janssen; and has grants from Pfizer, Lilly, Incyte, and other companies. Dr. Stempel reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON — and conveys the skin’s vulnerability to serious medical complications, said Adam Friedman, MD, at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient.

Key features of dermatoporosis include atrophic skin, solar purpura, white pseudoscars, easily acquired skin lacerations and tears, bruises, and delayed healing. “We’re going to see more of this, and it will more and more be a chief complaint of patients,” said Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, and co-chair of the meeting. GWU hosted the conference, describing it as a first-of-its-kind meeting dedicated to improving dermatologic care for older adults.

Dermatoporosis was described in the literature in 2007 by dermatologists at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. “It is not only a cosmetic problem,” Dr. Friedman said. “This is a medical problem ... which can absolutely lead to comorbidities [such as deep dissecting hematomas] that are a huge strain on the healthcare system.”

Dermatologists can meet the moment with holistic, creative combination treatment and counseling approaches aimed at improving the mechanical strength of skin and preventing potential complications in older patients, Dr. Friedman said at the meeting.

He described the case of a 76-year-old woman who presented with dermatoporosis on her arms involving pronounced skin atrophy, solar purpura, and a small covered laceration. “This was a patient who was both devastated by the appearance” and impacted by the pain and burden of dressing frequent wounds, said Dr. Friedman, who is also the director of the Residency Program, of Translational Research, and of Supportive Oncodermatology, all within the Department of Dermatology at GWU.

With 11 months of topical treatment that included daily application of calcipotriene 0.05% ointment and nightly application of tazarotene 0.045% lotion and oral supplementation with 1000-mg vitamin C twice daily and 1000-mg citrus bioflavonoid complex daily, as well as no changes to the medications she took for various comorbidities, the solar purpura improved significantly and “we made a huge difference in the integrity of her skin,” he said.

Dr. Friedman also described this case in a recently published article in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology titled “What’s Old Is New: An Emerging Focus on Dermatoporosis”.

Likely Pathophysiology

Advancing age and chronic ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure are the chief drivers of dermatoporosis. In addition to UVA and UVB light, other secondary drivers include genetic susceptibility, topical and systematic corticosteroid use, and anticoagulant treatment.

Its pathogenesis is not well described in the literature but is easy to envision, Dr. Friedman said. For one, both advancing age and exposure to UV light lead to a reduction in hygroscopic glycosaminoglycans, including hyaluronate (HA), and the impact of this diminishment is believed to go “beyond [the loss of] buoyancy,” he noted. Researchers have “been showing these are not just water-loving molecules, they also have some biologic properties” relating to keratinocyte production and epidermal turnover that appear to be intricately linked to the pathogenesis of dermatoporosis.

HAs have been shown to interact with the cell surface receptor CD44 to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation, and low levels of CD44 have been reported in skin with dermatoporosis compared with a younger control population. (A newly characterized organelle, the hyaluronosome, serves as an HA factory and contains CD44 and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, Dr. Friedman noted. Inadequate functioning may be involved in skin atrophy.)

Advancing age also brings an increase in matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)–1, –2, and –3, which are “the demolition workers of the skin,” and downregulation of a tissue inhibitor of MMPs, he said.

Adding insult to injury, dermis-penetrating UVA also activates MMPs, “obliterating collagen and elastin.” UVB generates DNA photoproducts, including oxidative stress and damaging skin cell DNA. “That UV light induces breakdown [of the skin] through different mechanisms and inhibits buildup is a simple concept I think our patients can understand,” Dr. Friedman said.

Multifaceted Treatment

For an older adult, “there is never a wrong time to start sun-protective measures” to prevent or try to halt the progression of dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman said, noting that “UV radiation is an immunosuppressant, so there are many good reasons to start” if the adult is not already taking measures on a regular basis.

Potential treatments for the syndrome of dermatoporosis are backed by few clinical studies, but dermatologists are skilled at translating the use of products from one disease state to another based on understandings of pathophysiology and mechanistic pathways, Dr. Friedman commented in an interview after the meeting.

For instance, “from decades of research, we know what retinoids will do to the skin,” he said in the interview. “We know they will turn on collagen-1 and -3 genes in the skin, and that they will increase the production of glycosaminoglycans ... By understanding the biology, we can translate this to dermatoporosis.” These changes were demonstrated, for instance, in a small study of topical retinol in older adults.

Studies of topical alpha hydroxy acid (AHA), moreover, have demonstrated epidermal thickening and firmness, and “some studies show they can limit steroid-induced atrophy,” Dr. Friedman said at the meeting. “And things like lactic acid and urea are super accessible.”

Topical dehydroepiandrosterone is backed by even less data than retinoids or AHAs are, “but it’s still something to consider” as part of a multimechanistic approach to dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman shared, noting that a small study demonstrated beneficial effects on epidermal atrophy in aging skin.

The use of vitamin D analogues such as calcipotriene, which is approved for the treatment of psoriasis, may also be promising. “One concept is that [vitamin D analogues] increase calcium concentrations in the epidermis, and calcium is so central to keratinocyte differentiation” and epidermal function that calcipotriene in combination with topical steroid therapy has been shown to limit skin atrophy, he noted.

Nutritionally, low protein intake is a known problem in the older population and is associated with increased skin fragility and poorer healing. From a prevention and treatment standpoint, therefore, patients can be counseled to be attentive to their diets, Dr. Friedman said. Experts have recommended a higher protein intake for older adults than for younger adults; in 2013, an international group recommended a protein intake of 1-1.5 g/kg/d for healthy older adults and more for those with acute or chronic illness.

“Patients love talking about diet and skin disease ... and they love over-the-counter nutraceuticals as well because they want something natural,” Dr. Friedman said. “I like using bioflavonoids in combination with vitamin C, which can be effective especially for solar purpura.”

A 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involving 67 patients with purpura associated with aging found a 50% reduction in purpura lesions among those took a particular citrus bioflavonoid blend twice daily. “I thought this was a pretty well-done study,” he said, noting that patient self-assessment and investigator global assessment were utilized.

Skin Injury and Wound Prevention

In addition to recommending gentle skin cleansers and daily moisturizing, dermatologists should talk to their older patients with dermatoporosis about their home environments. “What is it like? Is there furniture with sharp edges?” Dr. Friedman advised. If so, could they use sleeves or protectors on their arms or legs “to protect against injury?”

In a later meeting session about lower-extremity wounds on geriatric patients, Michael Stempel, DPM, assistant professor of medicine and surgery and chief of podiatry at GWU, said that he was happy to hear the term dermatoporosis being used because like diabetes, it’s a risk factor for developing lower-extremity wounds and poor wound healing.

He shared the case of an older woman with dermatoporosis who “tripped and skinned her knee against a step and then self-treated it for over a month by pouring hydrogen peroxide over it and letting air get to it.” The wound developed into “full-thickness tissue loss,” said Dr. Stempel, also medical director of the Wound Healing and Limb Preservation Center at GWU Hospital.

Misperceptions are common among older patients about how a simple wound should be managed; for instance, the adage “just let it get air” is not uncommon. This makes anticipatory guidance about basic wound care — such as the importance of a moist and occlusive environment and the safe use of hydrogen peroxide — especially important for patients with dermatoporosis, Dr. Friedman commented after the meeting.

Dermatoporosis is quantifiable, Dr. Friedman said during the meeting, with a scoring system having been developed by the researchers in Switzerland who originally coined the term. Its use in practice is unnecessary, but its existence is “nice to share with patients who feel bothered because oftentimes, patients feel it’s been dismissed by other providers,” he said. “Telling your patients there’s an actual name for their problem, and that there are ways to quantify and measure changes over time, is validating.”

Its recognition as a medical condition, Dr. Friedman added, also enables the dermatologist to bring it up and counsel appropriately — without a patient feeling shame — when it is identified in the context of a skin excision, treatment of a primary inflammatory skin disease, or management of another dermatologic problem.

Dr. Friedman disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for L’Oréal, La Roche-Posay, Galderma, and other companies; a speaker for Regeneron/Sanofi, Incyte, BMD, and Janssen; and has grants from Pfizer, Lilly, Incyte, and other companies. Dr. Stempel reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ELDERDERM 2024

‘Emerging Threat’ Xylazine Use Continues to Spread Across the United States

Illicit use of the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine continues to spread across the United States. The drug, which is increasingly mixed with fentanyl, often fails to respond to the opioid overdose reversal medication naloxone and can cause severe necrotic lesions.

A report released by Millennium Health, a specialty lab that provides medication monitoring for pain management, drug treatment, and behavioral and substance use disorder treatment centers across the country, showed the number of urine specimens collected and tested at the US drug treatment centers were positive for xylazine in the most recent 6 months.

As previously reported by this news organization, in late 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a communication alerting clinicians about the special management required for opioid overdoses tainted with xylazine, which is also known as “tranq” or “tranq dope.”

Subsequently, in early 2023, The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy designated xylazine combined with fentanyl as an emerging threat to the United States.

Both the FDA and the Drug Enforcement Administration have taken steps to try to stop trafficking of the combination. However, despite these efforts, xylazine use has continued to spread.

The Millennium Health Signals report showed that the greatest increase in xylazine use was largely in the western United States. In the first 6 months of 2023, 3% of urine drug tests (UDTs) in Washington, Oregon, California, Hawaii, and Alaska were positive for xylazine. From November 2023 to April 2024, this rose to 8%, a 147% increase. In the Mountain West, xylazine-positive UDTs increased from 2% in 2023 to 4% in 2024, an increase of 94%. In addition to growth in the West, the report showed that xylazine use increased by more than 100% in New England — from 14% in 2023 to 28% in 2024.

Nationally, 16% of all urine specimens were positive for xylazine from late 2023 to April 2024, up slightly from 14% from April to October 2023.

Xylazine use was highest in the East and in the mid-Atlantic United States. Still, positivity rates in the mid-Atlantic dropped from 44% to 33%. The states included in that group were New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. East North Central states (Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois) also experienced a decline in positive tests from 32% to 30%.

The South Atlantic states, which include Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, had a 17% increase in positivity — from 22% to 26%.

From April 2023 to April 2024 state-level UDT positivity rates were 40% in Pennsylvania, 37% in New York, and 35% in Ohio. But rates vary by locality. In Clermont and Hamilton counties in Ohio — both in the Cincinnati area — about 70% of specimens were positive for xylazine.

About one third of specimens in Maryland and South Carolina contained xylazine.

“Because xylazine exposure remains a significant challenge in the East and is a growing concern in the West, clinicians across the US need to be prepared to recognize and address the consequences of xylazine use — like diminished responses to naloxone and severe skin wounds that may lead to amputation — among people who use fentanyl,” Millennium Health Chief Clinical Officer Angela Huskey, PharmD, said in a press release.

The Health Signals Alert analyzed more than 50,000 fentanyl-positive UDT specimens collected between April 12, 2023, and April 11, 2024. Millennium Health researchers analyzed xylazine positivity rates in fentanyl-positive UDT specimens by the US Census Division and state.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Illicit use of the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine continues to spread across the United States. The drug, which is increasingly mixed with fentanyl, often fails to respond to the opioid overdose reversal medication naloxone and can cause severe necrotic lesions.

A report released by Millennium Health, a specialty lab that provides medication monitoring for pain management, drug treatment, and behavioral and substance use disorder treatment centers across the country, showed the number of urine specimens collected and tested at the US drug treatment centers were positive for xylazine in the most recent 6 months.

As previously reported by this news organization, in late 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a communication alerting clinicians about the special management required for opioid overdoses tainted with xylazine, which is also known as “tranq” or “tranq dope.”

Subsequently, in early 2023, The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy designated xylazine combined with fentanyl as an emerging threat to the United States.

Both the FDA and the Drug Enforcement Administration have taken steps to try to stop trafficking of the combination. However, despite these efforts, xylazine use has continued to spread.

The Millennium Health Signals report showed that the greatest increase in xylazine use was largely in the western United States. In the first 6 months of 2023, 3% of urine drug tests (UDTs) in Washington, Oregon, California, Hawaii, and Alaska were positive for xylazine. From November 2023 to April 2024, this rose to 8%, a 147% increase. In the Mountain West, xylazine-positive UDTs increased from 2% in 2023 to 4% in 2024, an increase of 94%. In addition to growth in the West, the report showed that xylazine use increased by more than 100% in New England — from 14% in 2023 to 28% in 2024.

Nationally, 16% of all urine specimens were positive for xylazine from late 2023 to April 2024, up slightly from 14% from April to October 2023.

Xylazine use was highest in the East and in the mid-Atlantic United States. Still, positivity rates in the mid-Atlantic dropped from 44% to 33%. The states included in that group were New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. East North Central states (Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois) also experienced a decline in positive tests from 32% to 30%.

The South Atlantic states, which include Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, had a 17% increase in positivity — from 22% to 26%.

From April 2023 to April 2024 state-level UDT positivity rates were 40% in Pennsylvania, 37% in New York, and 35% in Ohio. But rates vary by locality. In Clermont and Hamilton counties in Ohio — both in the Cincinnati area — about 70% of specimens were positive for xylazine.

About one third of specimens in Maryland and South Carolina contained xylazine.

“Because xylazine exposure remains a significant challenge in the East and is a growing concern in the West, clinicians across the US need to be prepared to recognize and address the consequences of xylazine use — like diminished responses to naloxone and severe skin wounds that may lead to amputation — among people who use fentanyl,” Millennium Health Chief Clinical Officer Angela Huskey, PharmD, said in a press release.

The Health Signals Alert analyzed more than 50,000 fentanyl-positive UDT specimens collected between April 12, 2023, and April 11, 2024. Millennium Health researchers analyzed xylazine positivity rates in fentanyl-positive UDT specimens by the US Census Division and state.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Illicit use of the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine continues to spread across the United States. The drug, which is increasingly mixed with fentanyl, often fails to respond to the opioid overdose reversal medication naloxone and can cause severe necrotic lesions.

A report released by Millennium Health, a specialty lab that provides medication monitoring for pain management, drug treatment, and behavioral and substance use disorder treatment centers across the country, showed the number of urine specimens collected and tested at the US drug treatment centers were positive for xylazine in the most recent 6 months.

As previously reported by this news organization, in late 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a communication alerting clinicians about the special management required for opioid overdoses tainted with xylazine, which is also known as “tranq” or “tranq dope.”

Subsequently, in early 2023, The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy designated xylazine combined with fentanyl as an emerging threat to the United States.

Both the FDA and the Drug Enforcement Administration have taken steps to try to stop trafficking of the combination. However, despite these efforts, xylazine use has continued to spread.

The Millennium Health Signals report showed that the greatest increase in xylazine use was largely in the western United States. In the first 6 months of 2023, 3% of urine drug tests (UDTs) in Washington, Oregon, California, Hawaii, and Alaska were positive for xylazine. From November 2023 to April 2024, this rose to 8%, a 147% increase. In the Mountain West, xylazine-positive UDTs increased from 2% in 2023 to 4% in 2024, an increase of 94%. In addition to growth in the West, the report showed that xylazine use increased by more than 100% in New England — from 14% in 2023 to 28% in 2024.

Nationally, 16% of all urine specimens were positive for xylazine from late 2023 to April 2024, up slightly from 14% from April to October 2023.

Xylazine use was highest in the East and in the mid-Atlantic United States. Still, positivity rates in the mid-Atlantic dropped from 44% to 33%. The states included in that group were New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. East North Central states (Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois) also experienced a decline in positive tests from 32% to 30%.

The South Atlantic states, which include Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, had a 17% increase in positivity — from 22% to 26%.

From April 2023 to April 2024 state-level UDT positivity rates were 40% in Pennsylvania, 37% in New York, and 35% in Ohio. But rates vary by locality. In Clermont and Hamilton counties in Ohio — both in the Cincinnati area — about 70% of specimens were positive for xylazine.

About one third of specimens in Maryland and South Carolina contained xylazine.

“Because xylazine exposure remains a significant challenge in the East and is a growing concern in the West, clinicians across the US need to be prepared to recognize and address the consequences of xylazine use — like diminished responses to naloxone and severe skin wounds that may lead to amputation — among people who use fentanyl,” Millennium Health Chief Clinical Officer Angela Huskey, PharmD, said in a press release.

The Health Signals Alert analyzed more than 50,000 fentanyl-positive UDT specimens collected between April 12, 2023, and April 11, 2024. Millennium Health researchers analyzed xylazine positivity rates in fentanyl-positive UDT specimens by the US Census Division and state.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

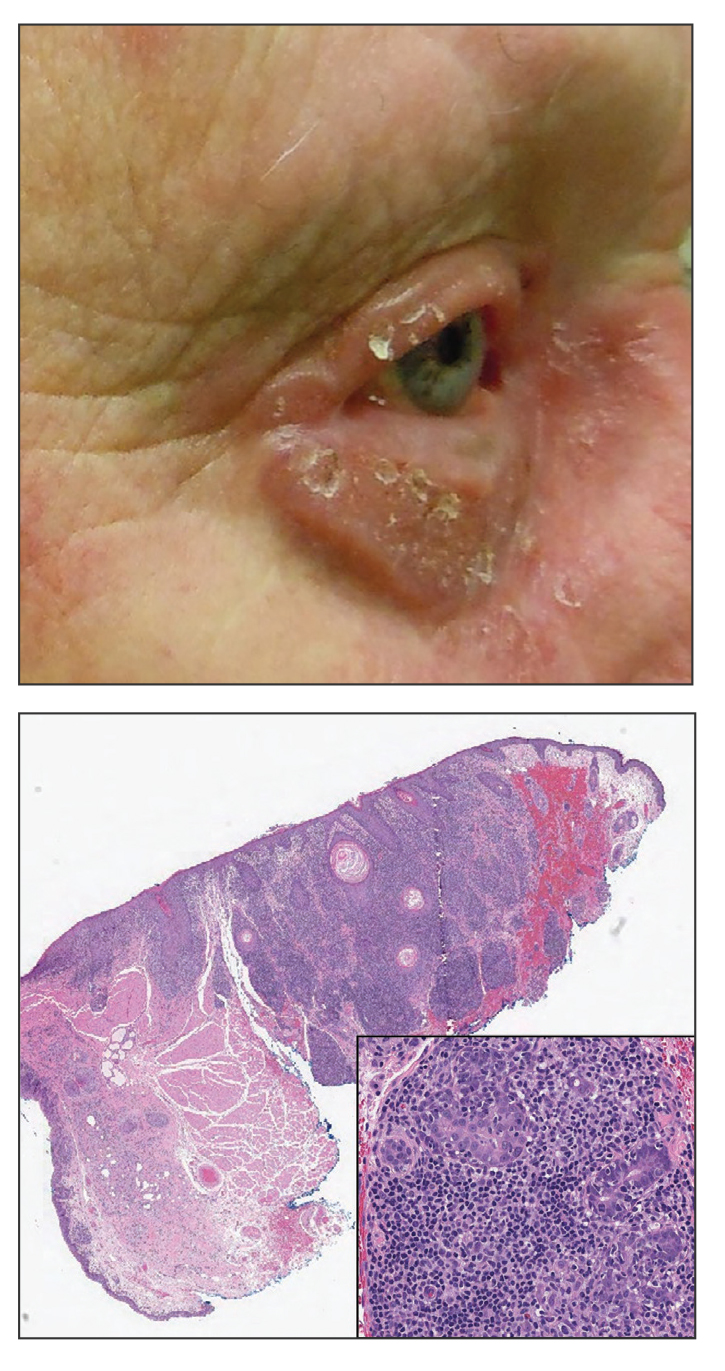

Progressive Eyelash Loss and Scale of the Right Eyelid

The Diagnosis: Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

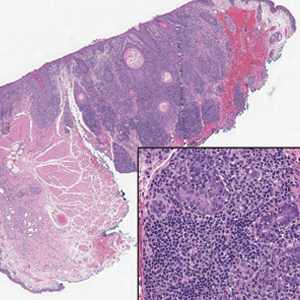

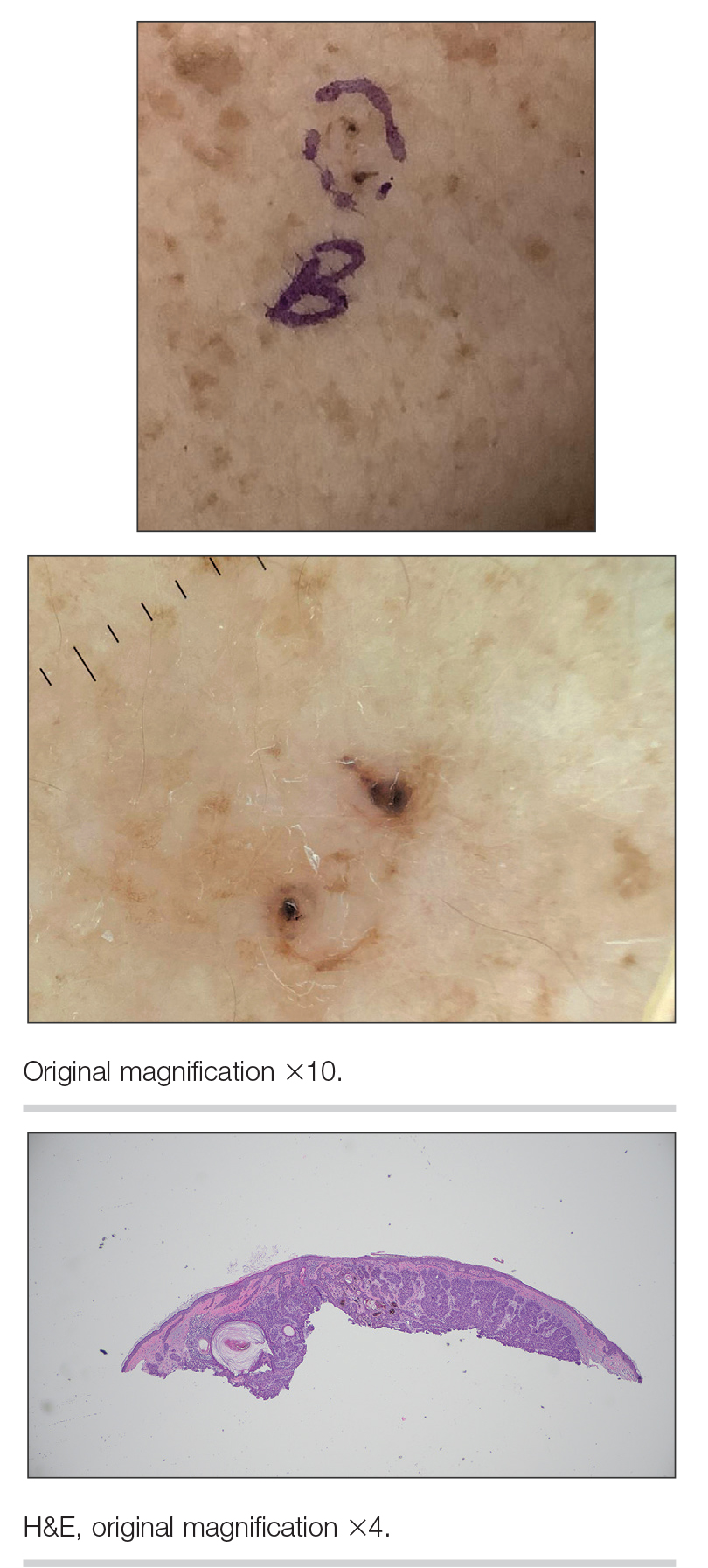

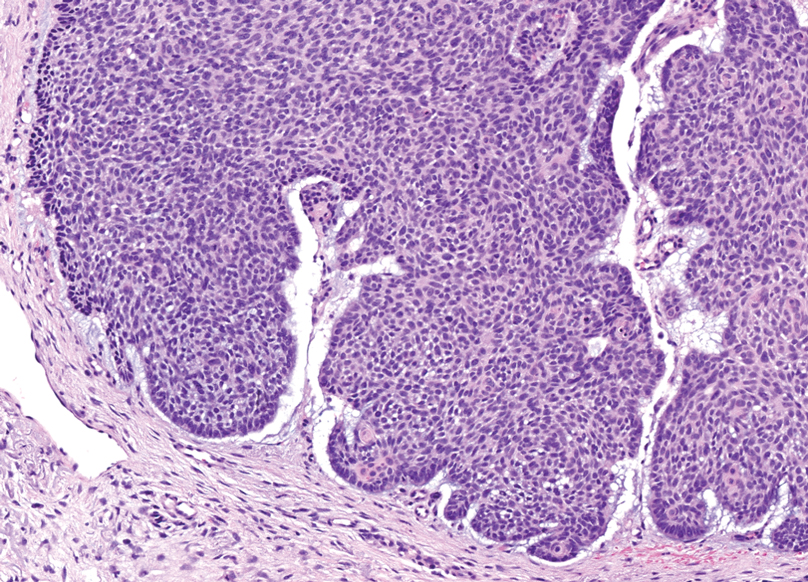

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) characterized by folliculotropism and follicular-based lesions. The clinical manifestation of FMF can vary and includes patches, plaques, or tumors resembling nonfolliculotropic MF; acneform lesions including comedones and pustules; or areas of alopecia. Lesions commonly involve the head and neck but also can be seen on the trunk or extremities. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides can be accompanied by pruritus or superimposed secondary infection.

Histologic features of FMF include follicular (perifollicular or intrafollicular) infiltration by atypical T cells showing cerebriform nuclei.1 In early lesions, there may be only mild superficial perivascular inflammation without notable lymphocyte atypia, making diagnosis challenging. 2,3 Mucinous degeneration of the follicles—termed follicular mucinosis—is a common histologic finding in FMF.1,2 Follicular mucinosis is not exclusive to FMF; it can be primary/idiopathic or secondary to underlying inflammatory or neoplastic disorders such as FMF. On immunohistochemistry, FMF most commonly demonstrates a helper T cell phenotype that is positive for CD3 and CD4 and negative for CD8, with aberrant loss of CD7 and variably CD5, which is similar to classic MF. Occasionally, larger CD30+ cells also can be present in the dermis. T-cell gene rearrangement studies will demonstrate T-cell receptor clonality in most cases.2

Many large retrospective cohort studies have suggested that patients with FMF have a worse prognosis than classic MF, with a 5-year survival rate of 62% to 87% for early-stage FMF vs more than 90% for classic patchand plaque-stage MF.4-7 However, a 2016 study suggested histologic evaluation may be able to further differentiate clinically identical cases into indolent and aggressive forms of FMF with considerably different outcomes based on the density of the perifollicular infiltrate.5 The presence of follicular mucinosis has no impact on prognosis compared to cases without follicular mucinosis.1,2

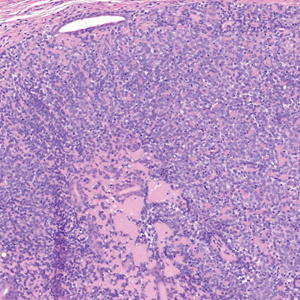

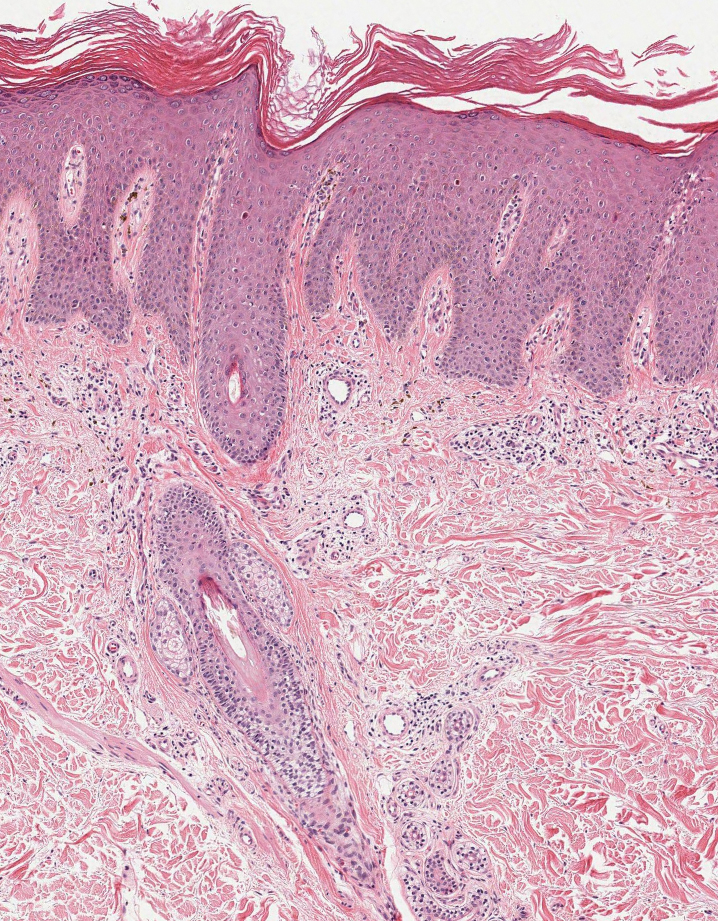

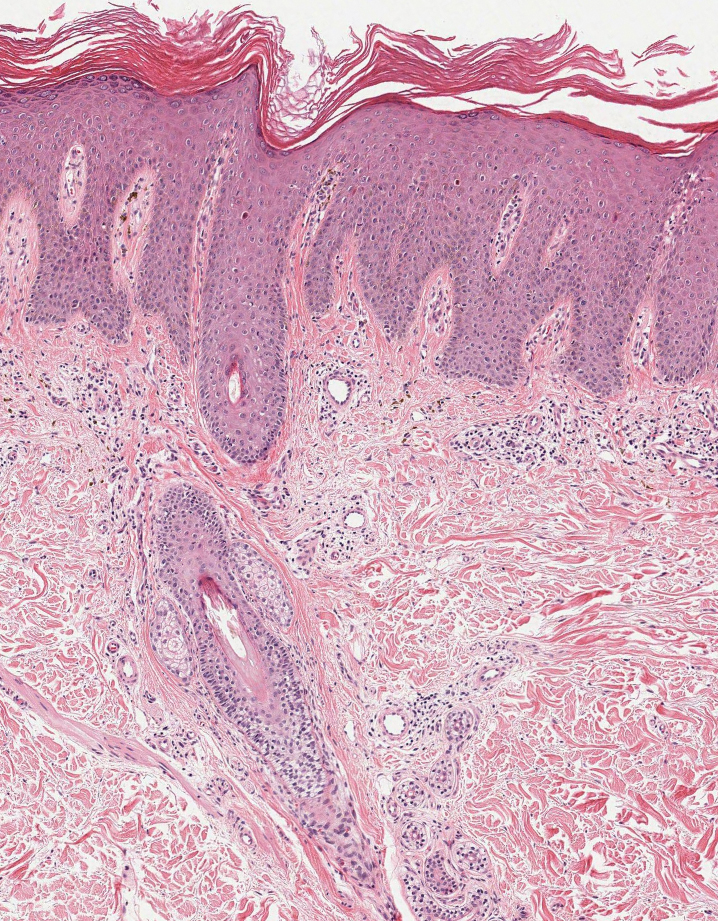

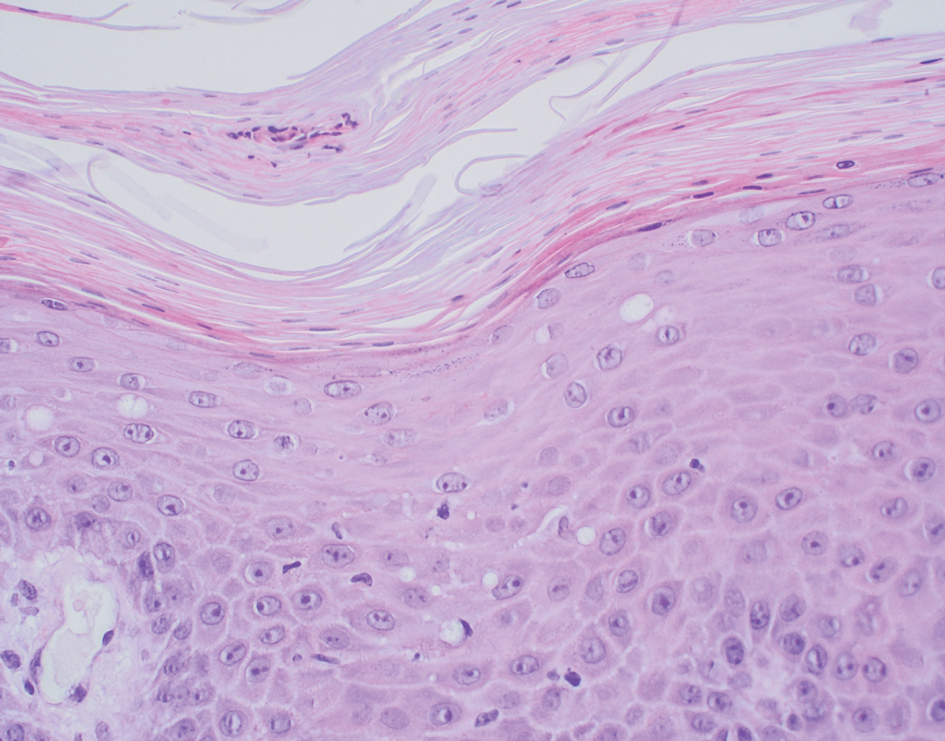

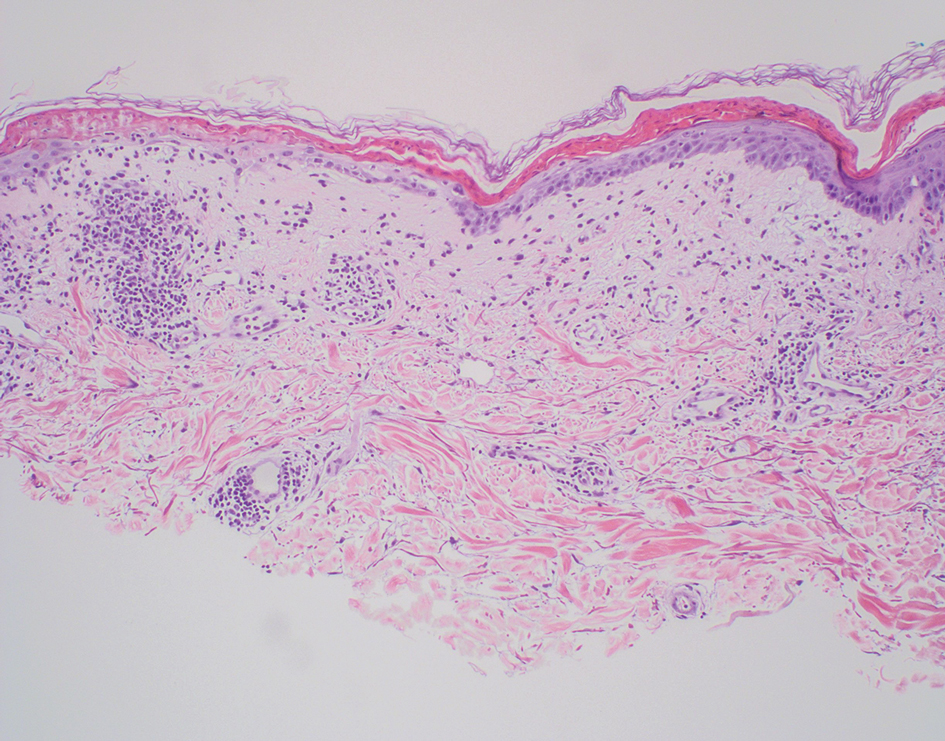

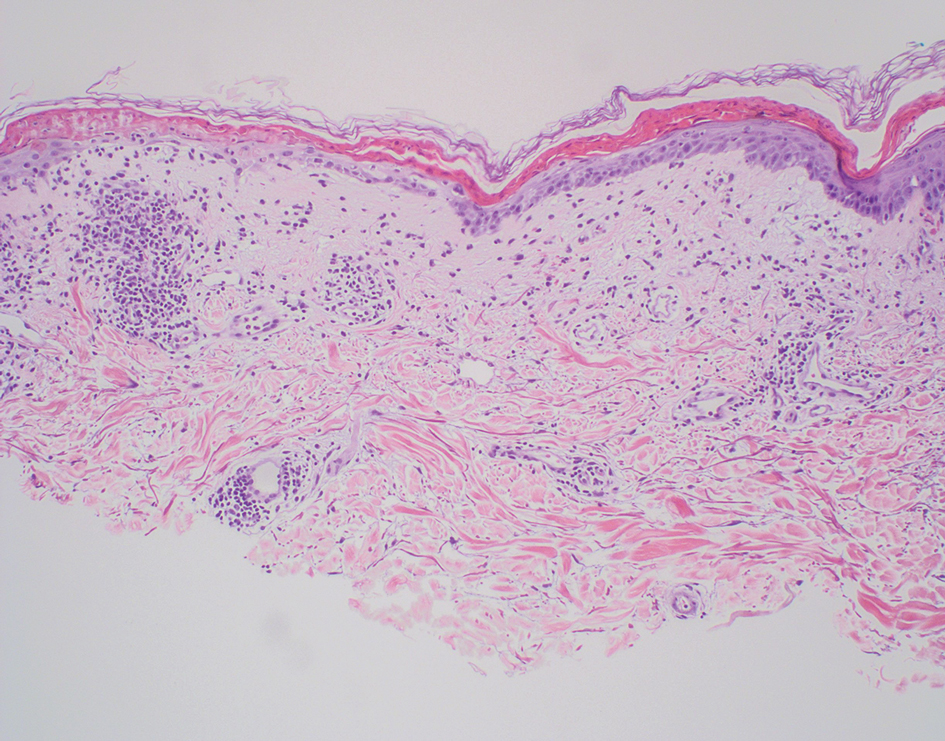

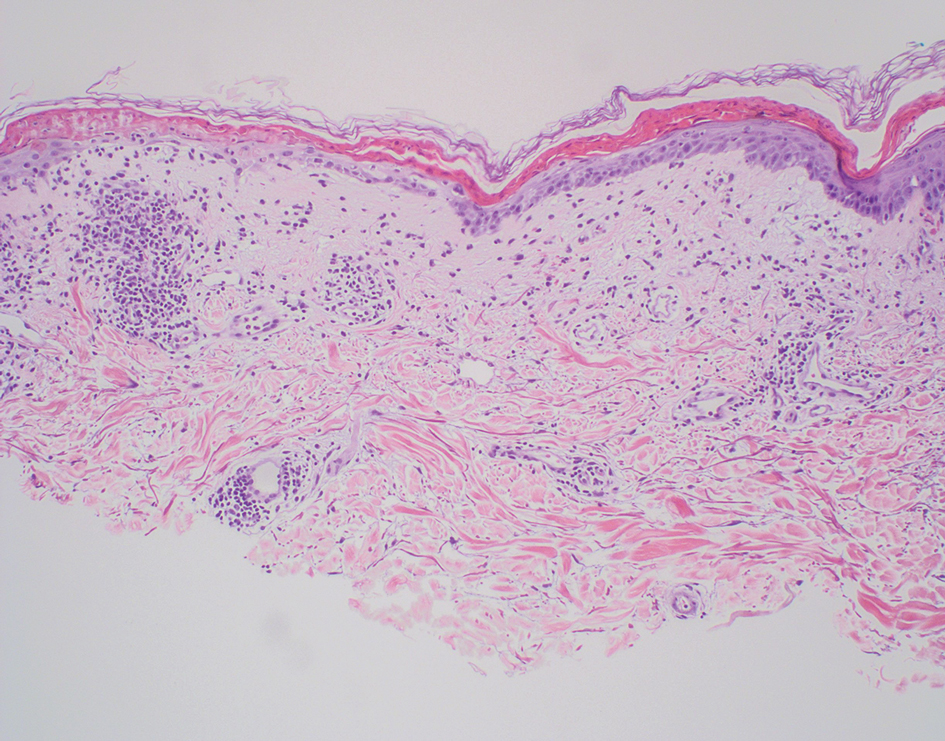

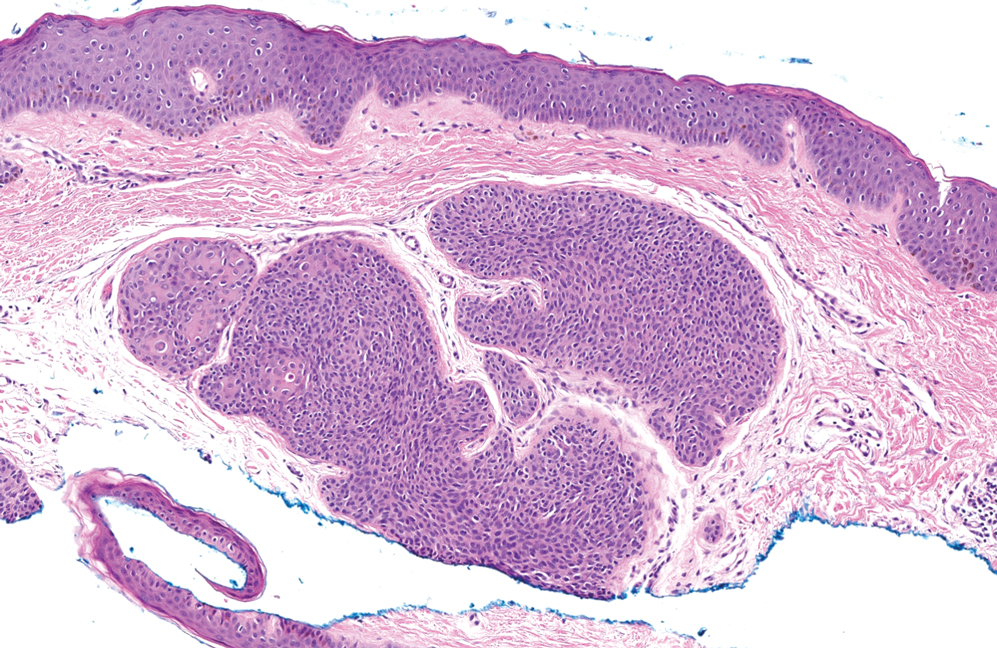

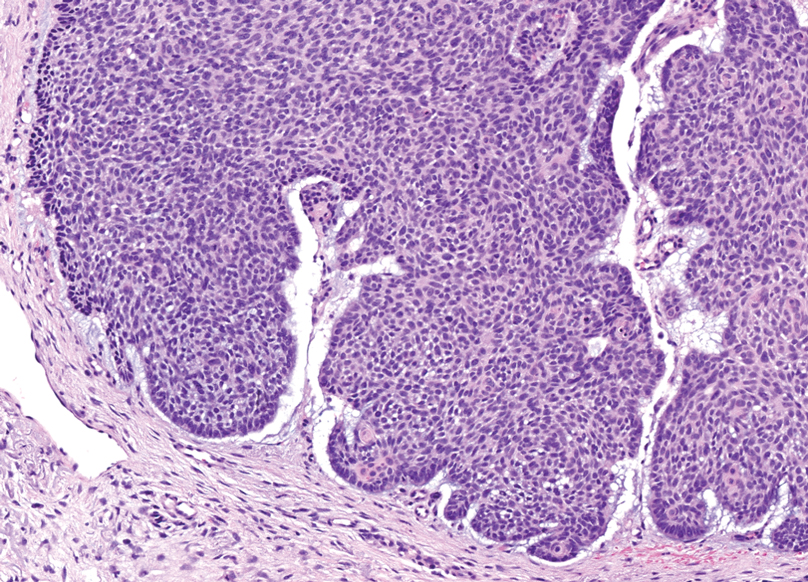

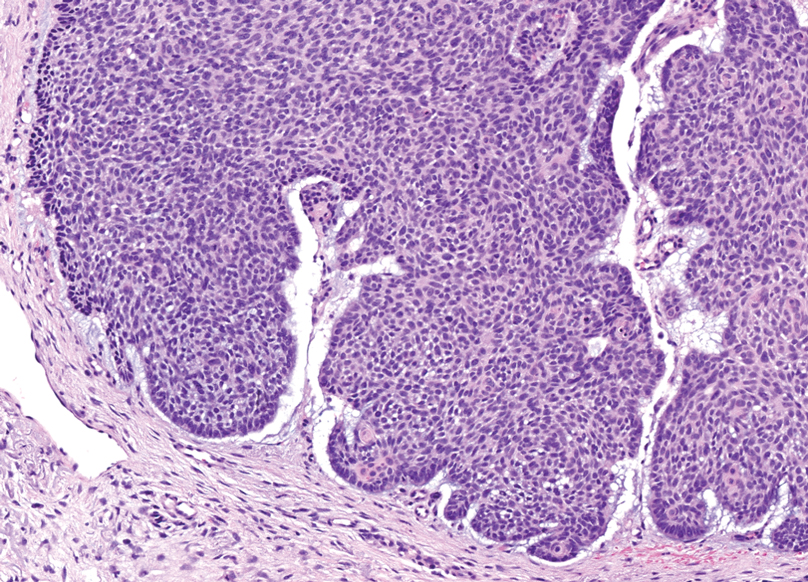

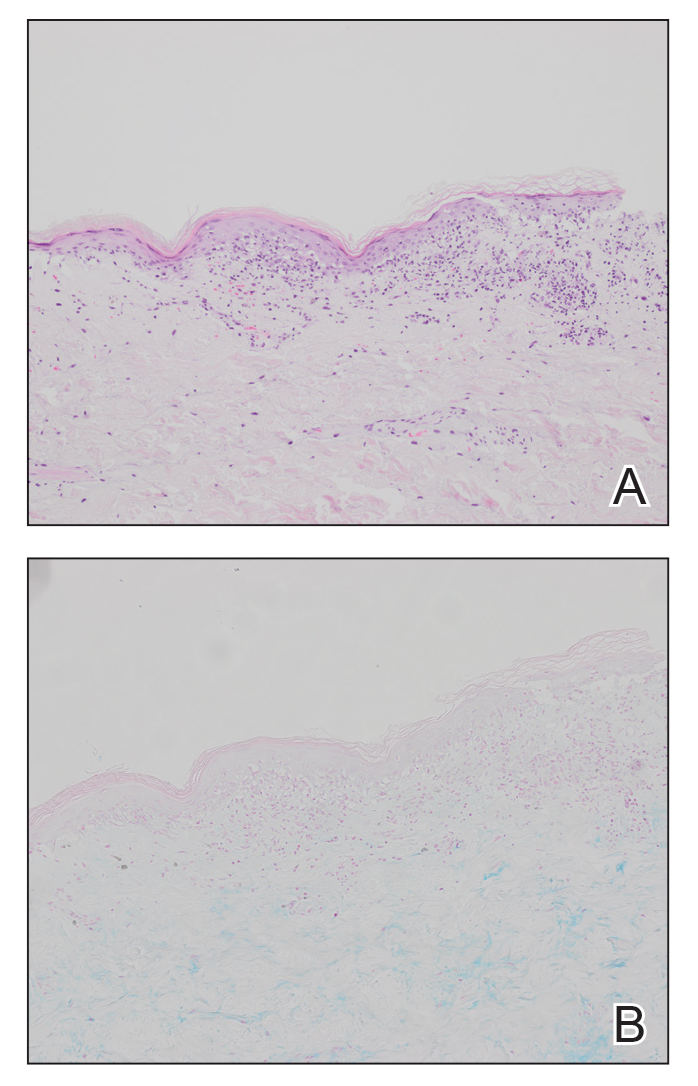

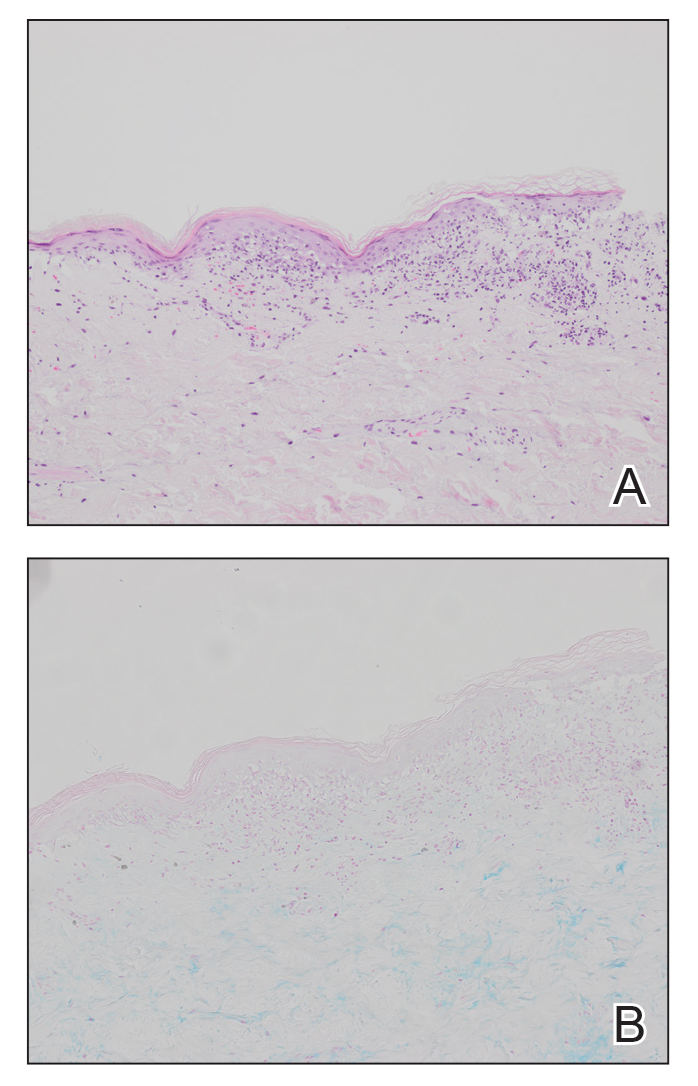

Alopecia mucinosa is characterized by infiltrating, erythematous, scaling plaques localized to the head and neck.8 It is diagnosed clinically, and histopathology shows follicular mucinosis. The terms alopecia mucinosa and follicular mucinosis often are used interchangeably. Over the past few decades, 3 variants have been categorized: primary acute, primary chronic, and secondary. The primary acute form manifests in children and young adults as solitary lesions, which often resolve spontaneously. In contrast, the primary chronic form manifests in older adults as multiple disseminated lesions with a chronic relapsing course.8,9 The secondary form can occur in the setting of other disorders, including lupus erythematosus, hypertrophic lichen planus, alopecia areata, and neoplasms such as MF or Hodgkin lymphoma.9 The histopathologic findings are similar for all types of alopecia mucinosa, with cystic pools of mucin deposition in the sebaceous glands and external root sheath of the follicles as well as associated inflammation composed of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1).9,10 The inflammatory infiltrate rarely extends into the epidermis or upper portion of the hair follicle. Although histopathology alone cannot reliably distinguish between primary and secondary forms of alopecia mucinosa, MF (including follicular MF) or another underlying cutaneous T-cell lymphoma should be considered if inflammation extends into the upper dermis, epidermis, or follicles or is in a dense bandlike distribution.11 On immunohistochemistry, lymphocytes should show positivity for CD3, CD4, and CD8. The CD4:CD8 ratio often is 1:1 in alopecia mucinosa, while in FMF it is approximately 3:1.10 CD7 commonly is negative but can be present in a small percentage of cases.12 T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies have detected clonality in both primary and secondary alopecia mucinosa and thus cannot be used alone to distinguish between the two.10 Given the overlap in histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of primary and secondary alopecia mucinosa, definitive diagnosis cannot be made with any single modality and should be based on correlating clinical presentation, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analyses.

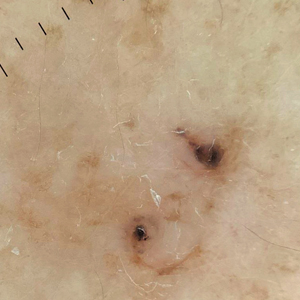

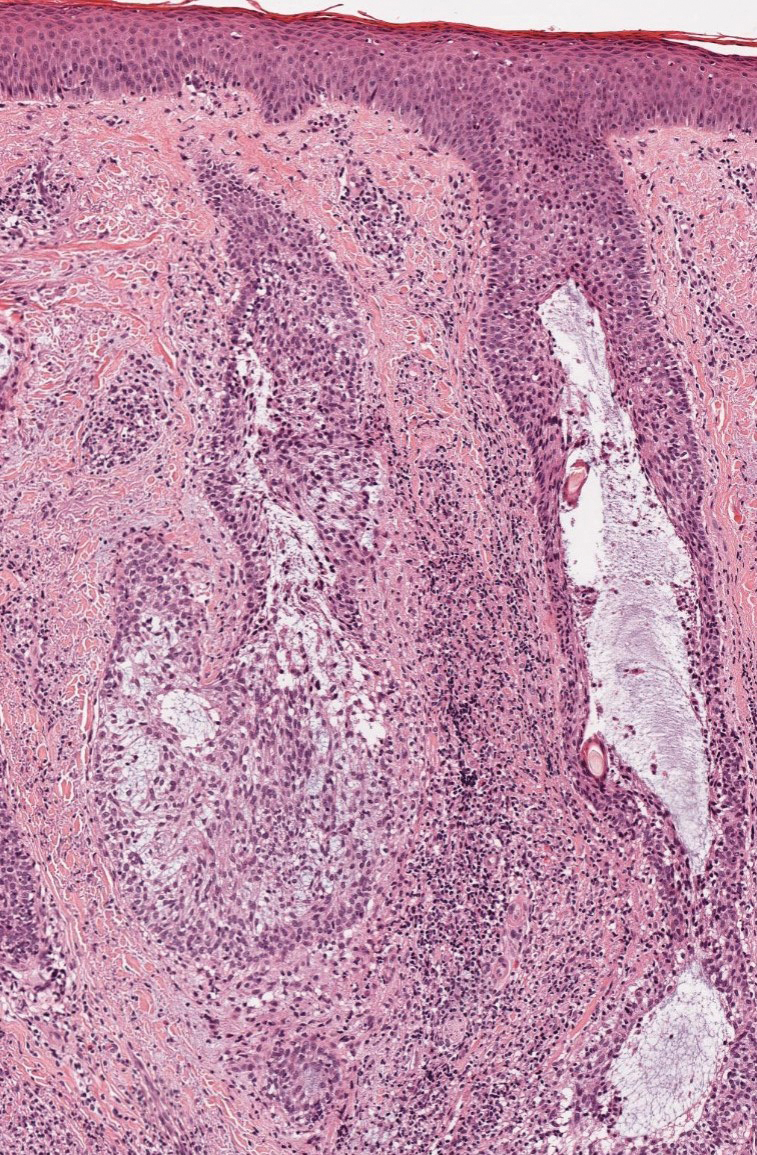

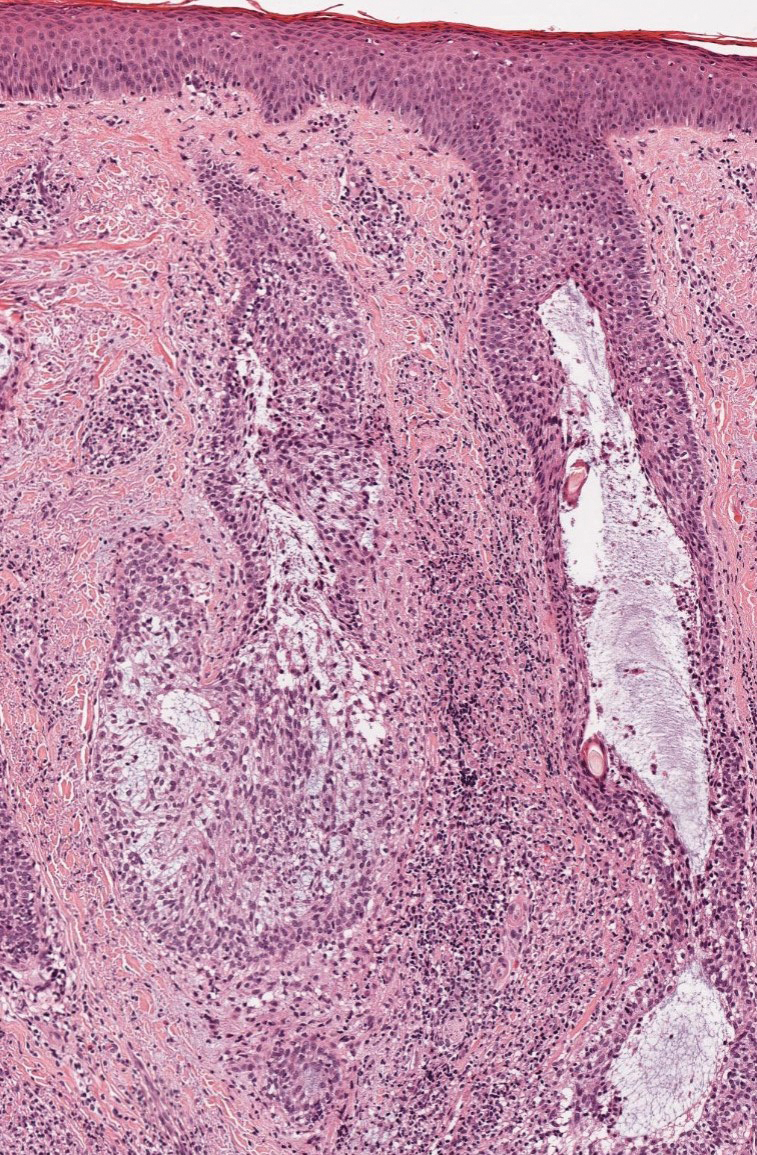

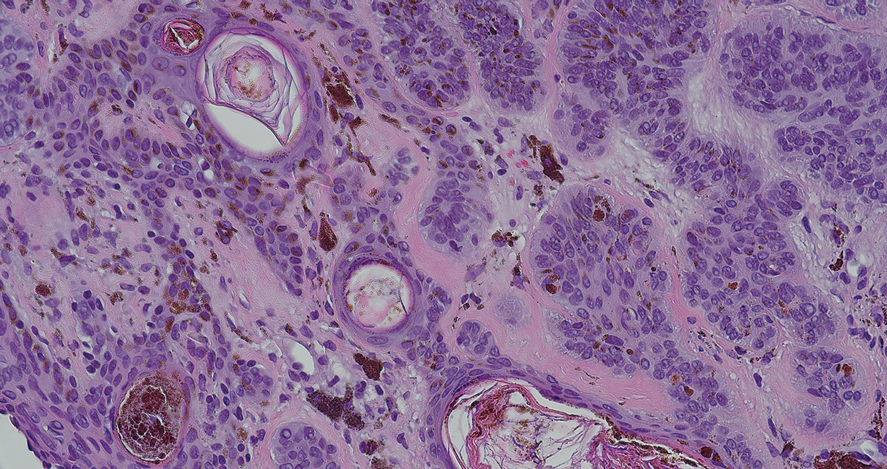

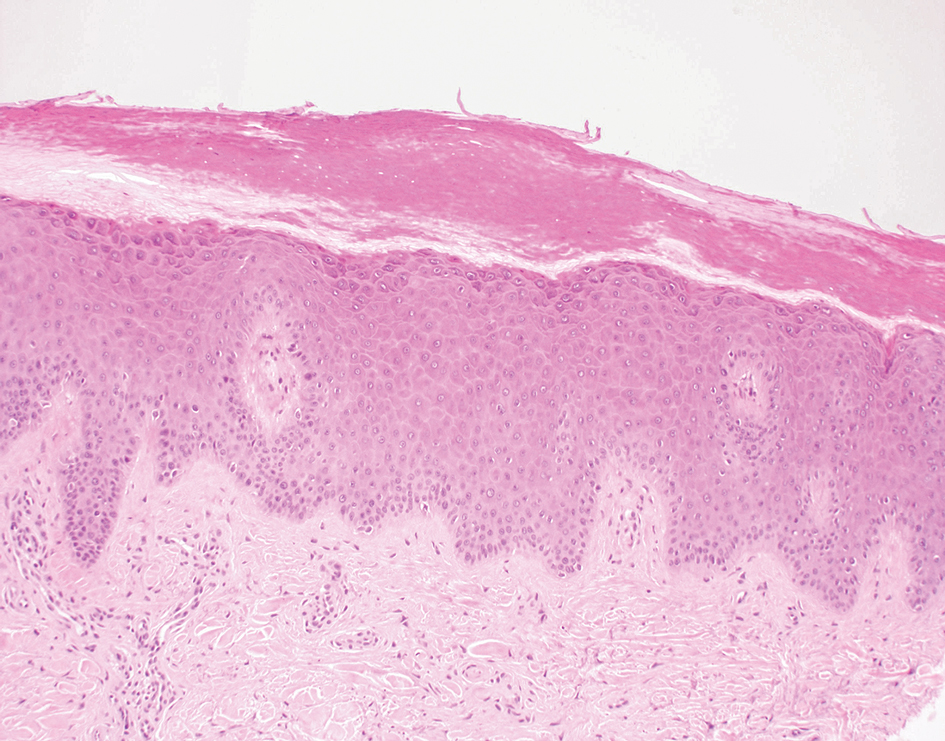

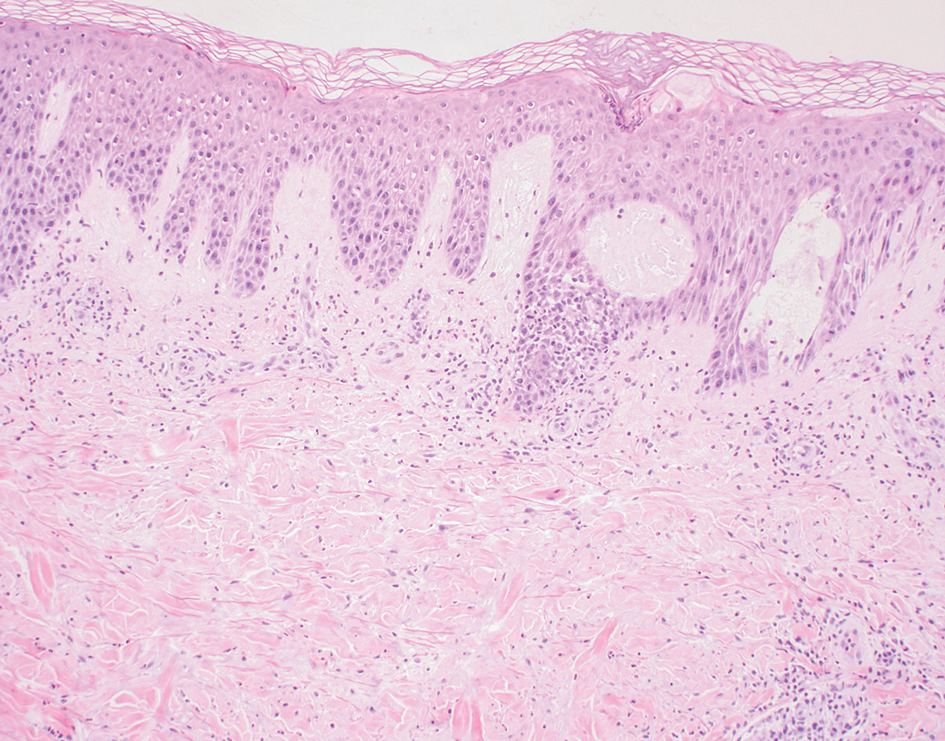

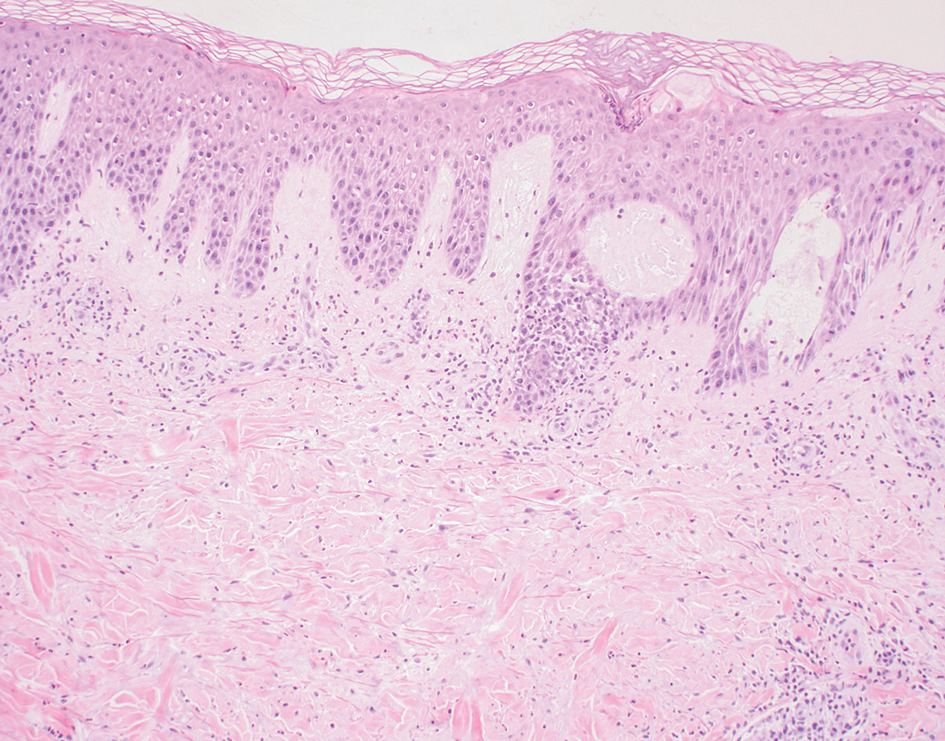

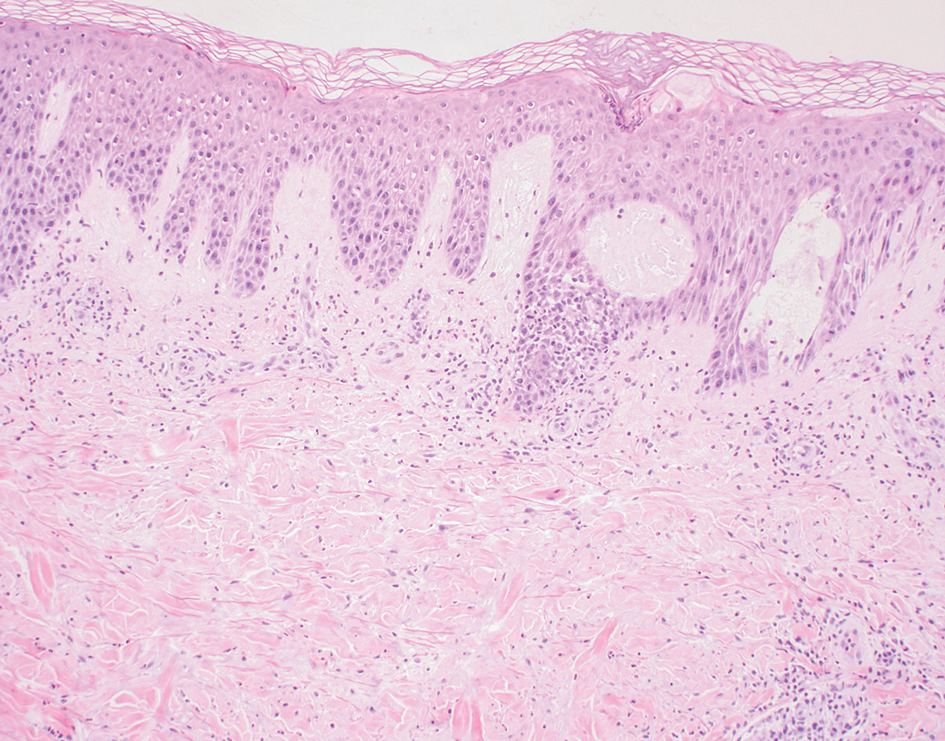

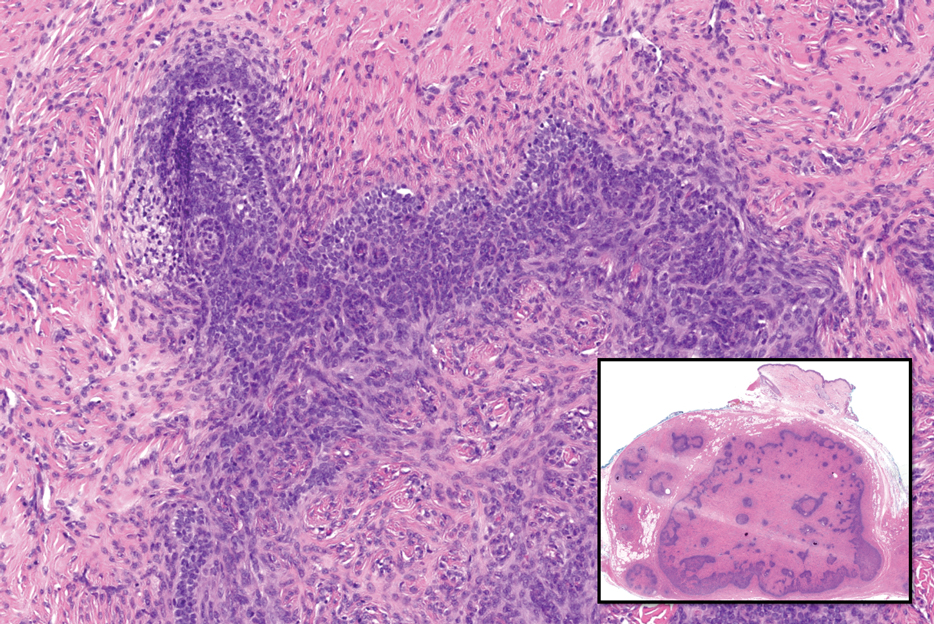

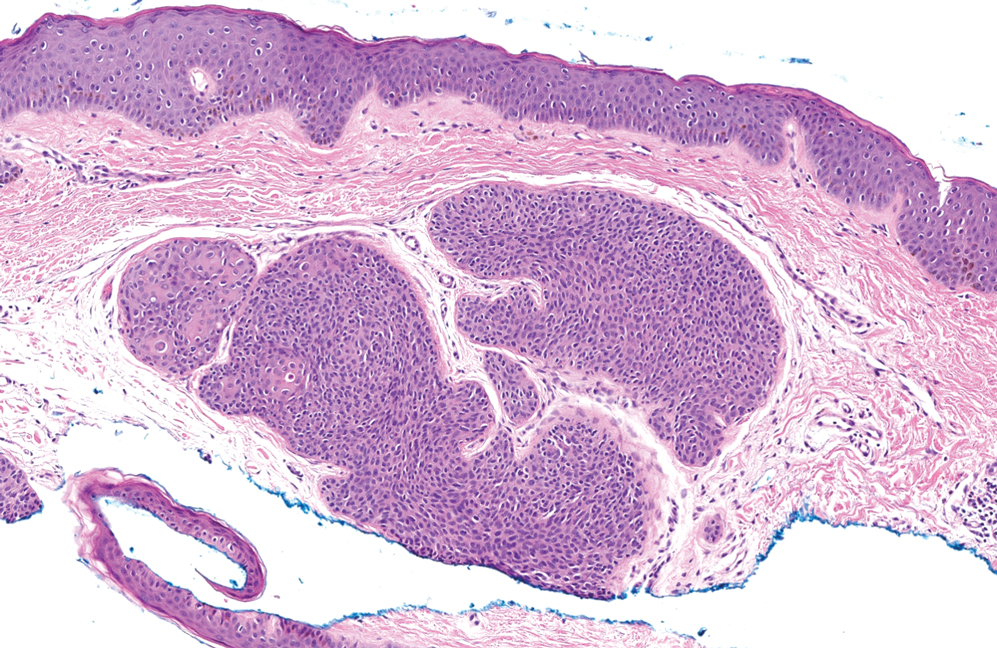

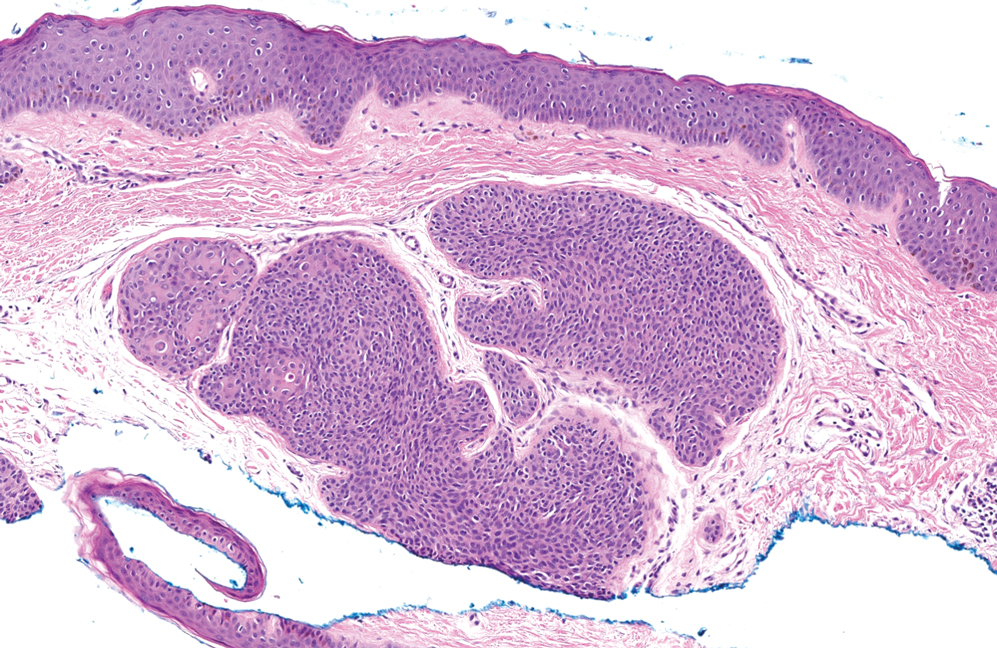

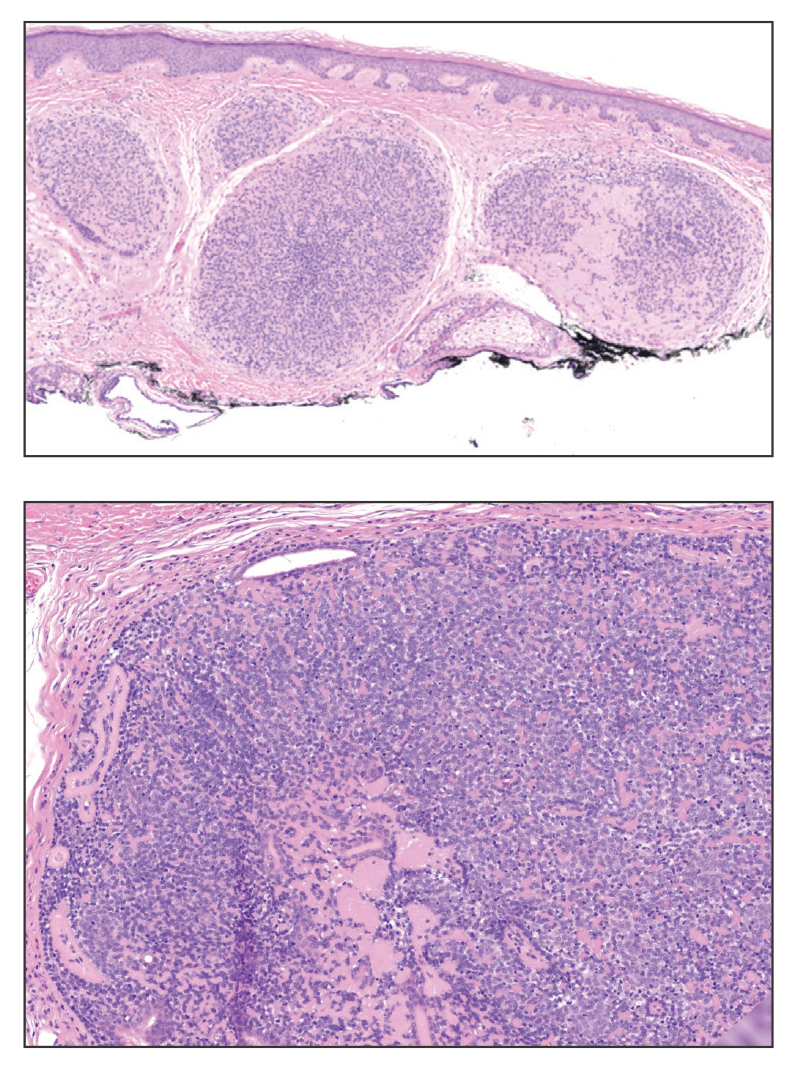

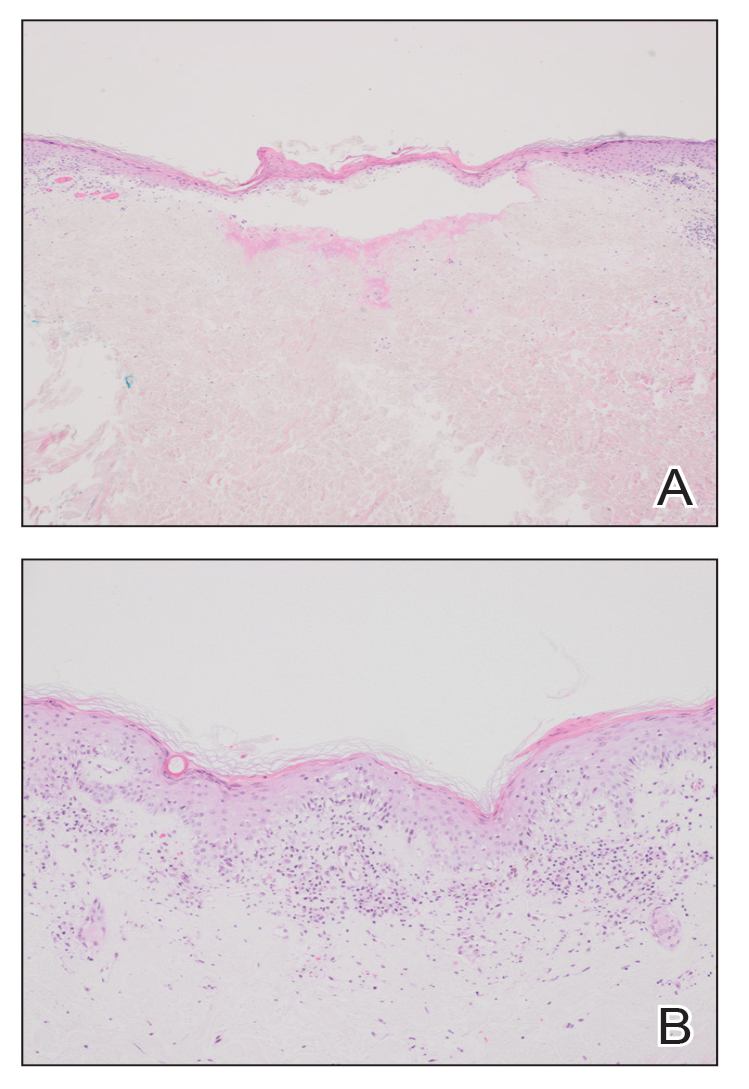

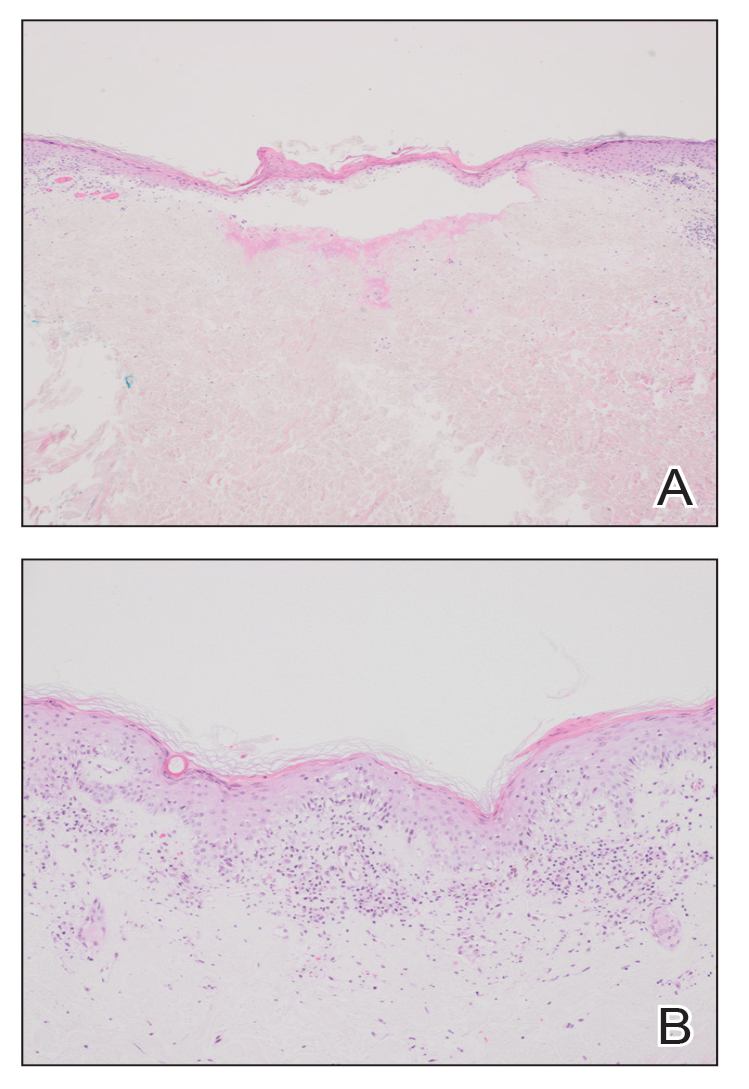

Inflammatory dermatoses including seborrheic dermatitis also are in the differential diagnosis for FMF. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting 1% to 3% of the general population. 13 Patients usually present with scaly and greasy plaques and papules localized to areas with increased sebaceous glands and high sebum production such as the face, scalp, and intertriginous regions. The distribution often is symmetrical, and the severity of disease can vary substantially.13 Sebopsoriasis is an entity with overlapping features of seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis, including thicker, more erythematous plaques that are more elevated. Histopathology of seborrheic dermatitis reveals spongiotic inflammation in the epidermis characterized by rounding of the keratinocytes, widening of the intercellular spaces, and accumulation of intracellular edema, causing the formation of clear spaces in the epidermis (Figure 2). Focal parakeratosis, usually in the follicular ostia, and mounds of scaly crust often are present. 14 A periodic acid–Schiff stain should be performed to rule out infectious dermatophytes, which can show similar clinical and histologic features. More chronic cases of seborrheic dermatitis often can take on histologic features of psoriasis, namely epidermal hyperplasia with thinning over dermal papillae, though the hyperplasia in psoriasis is more regular.

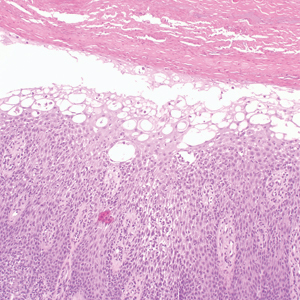

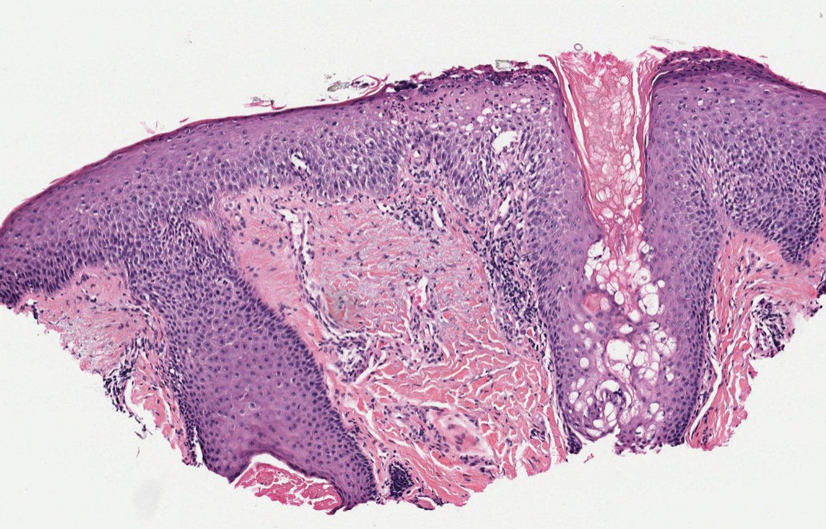

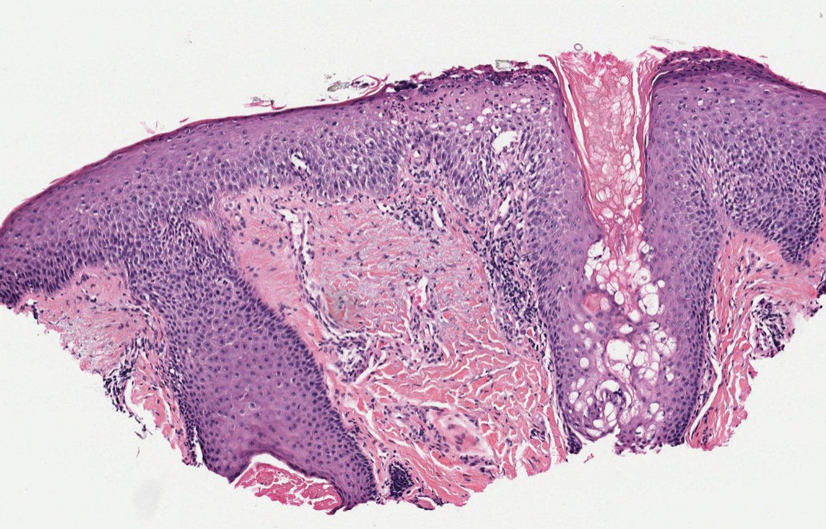

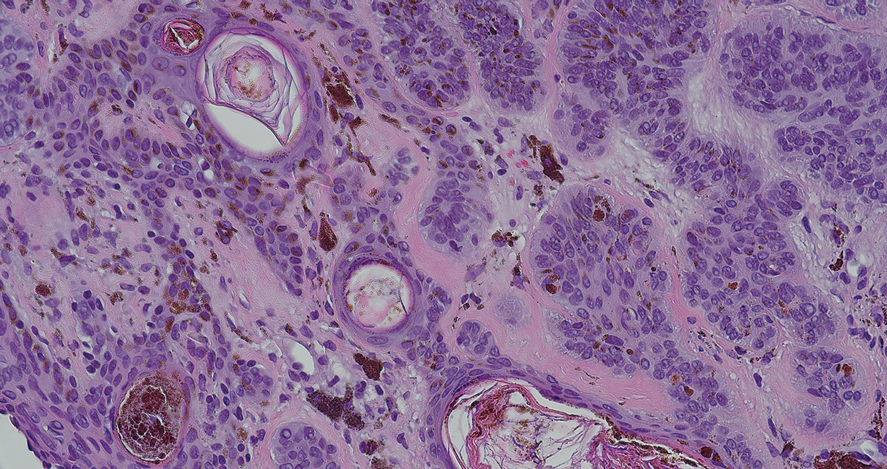

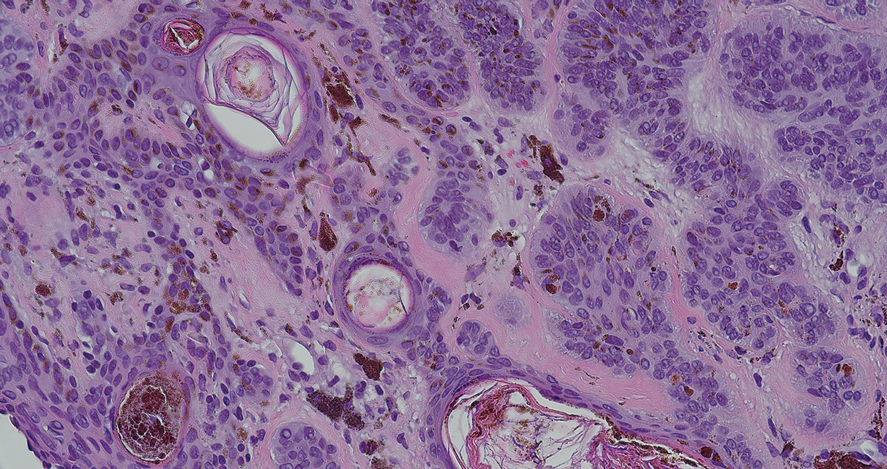

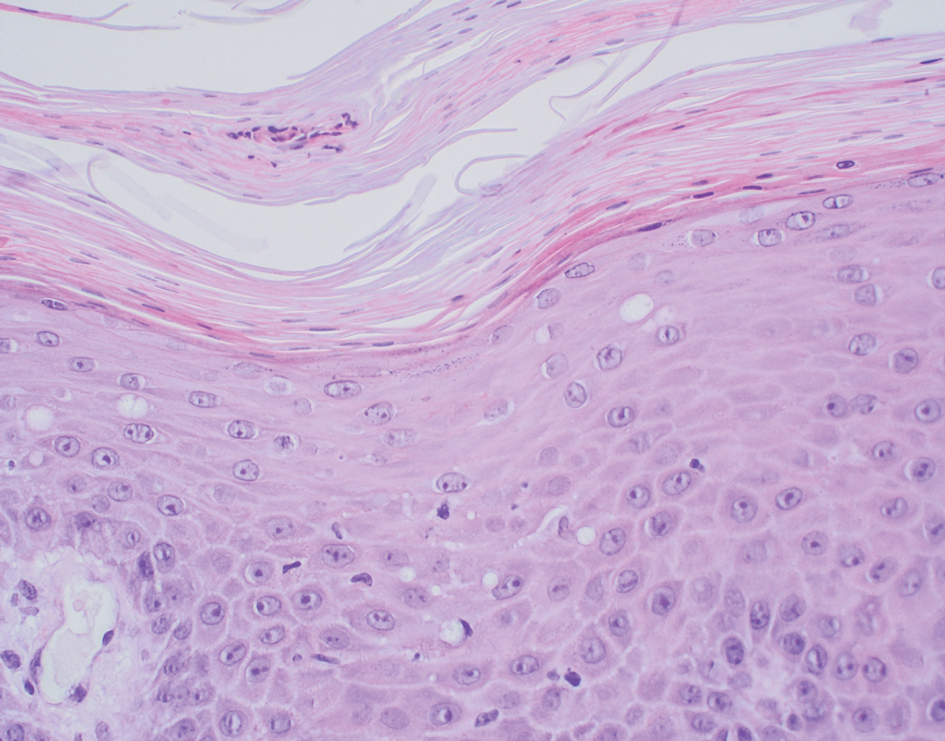

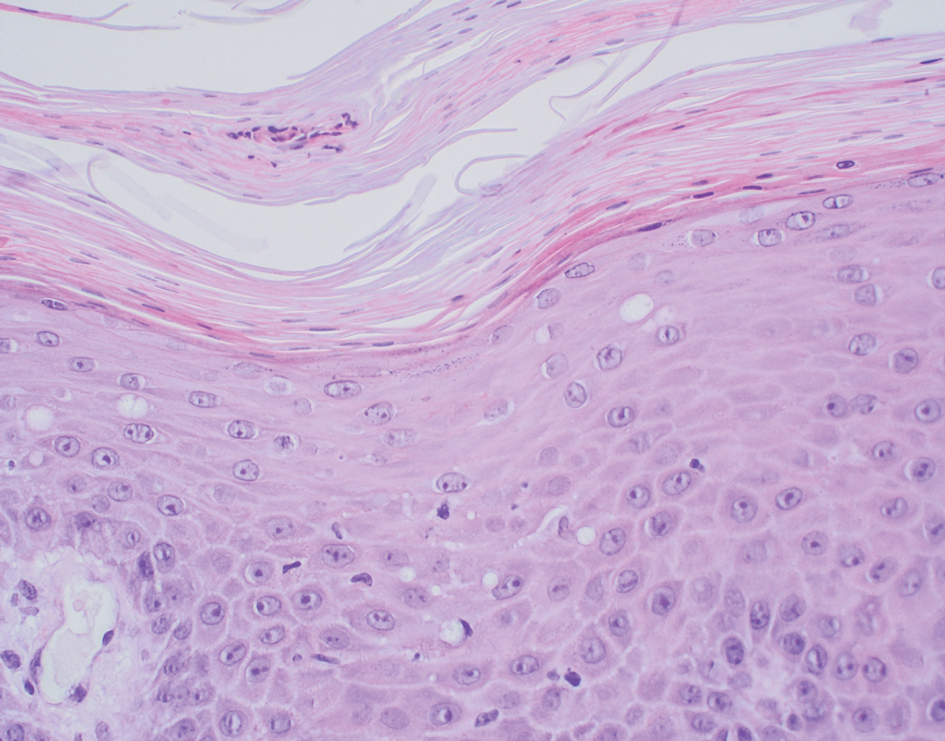

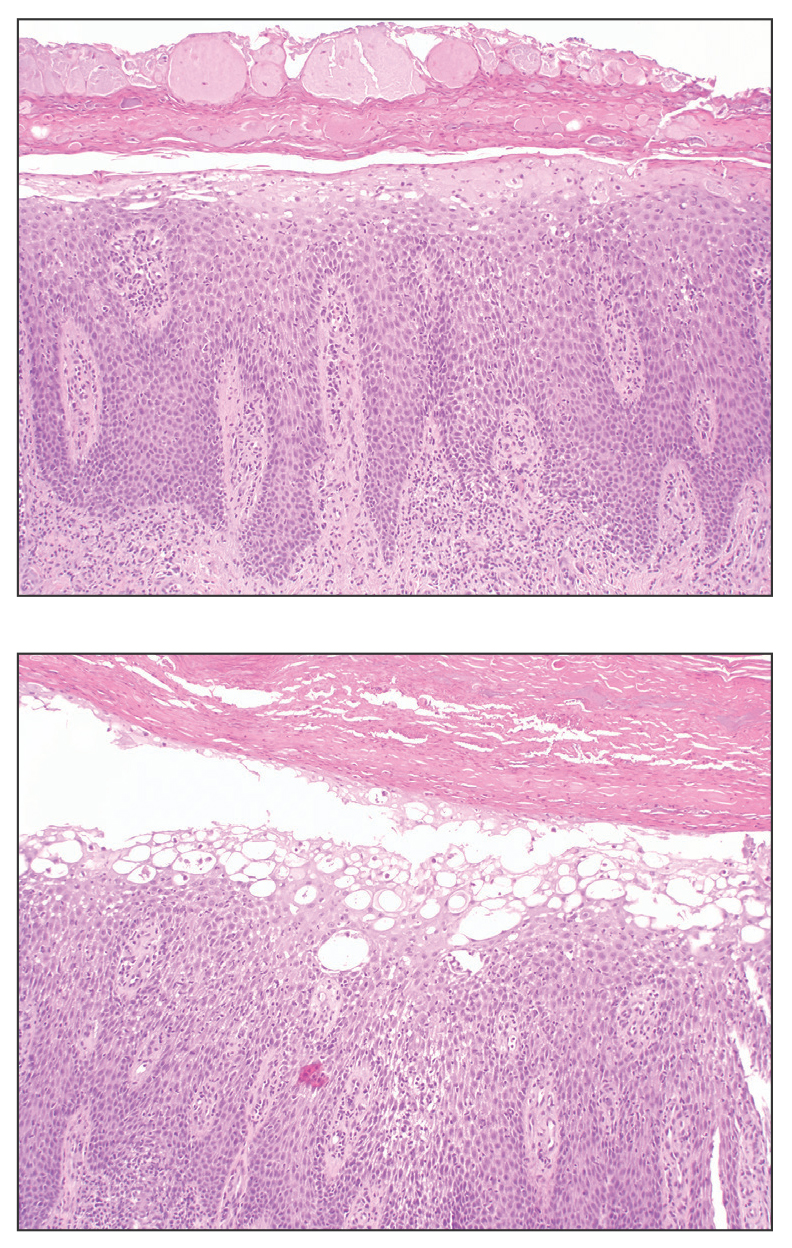

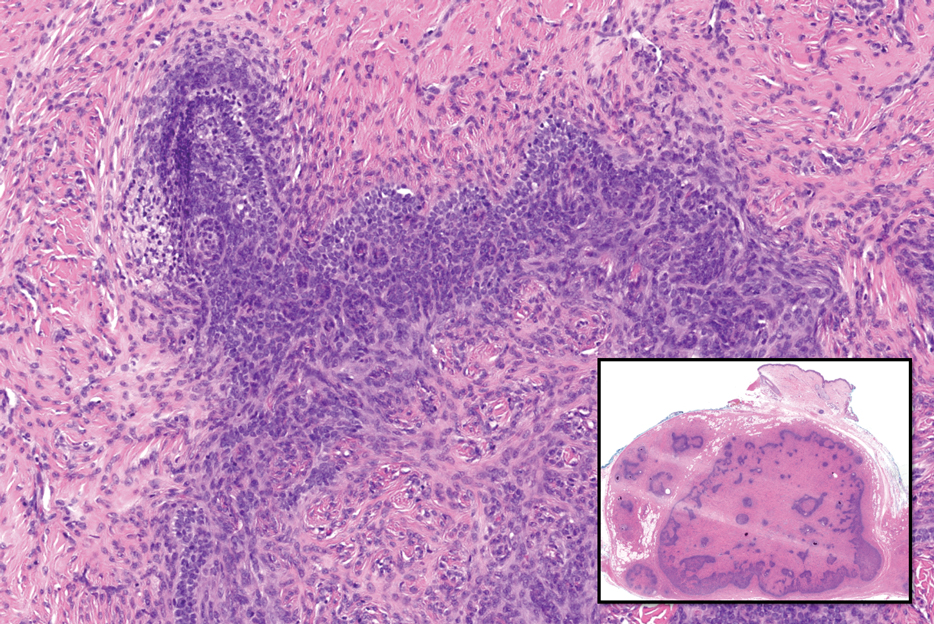

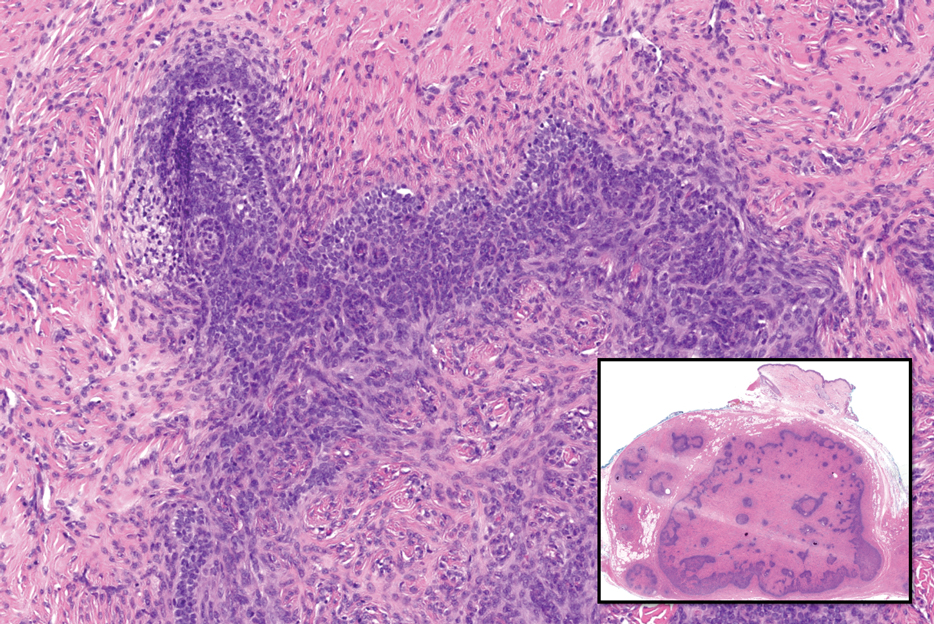

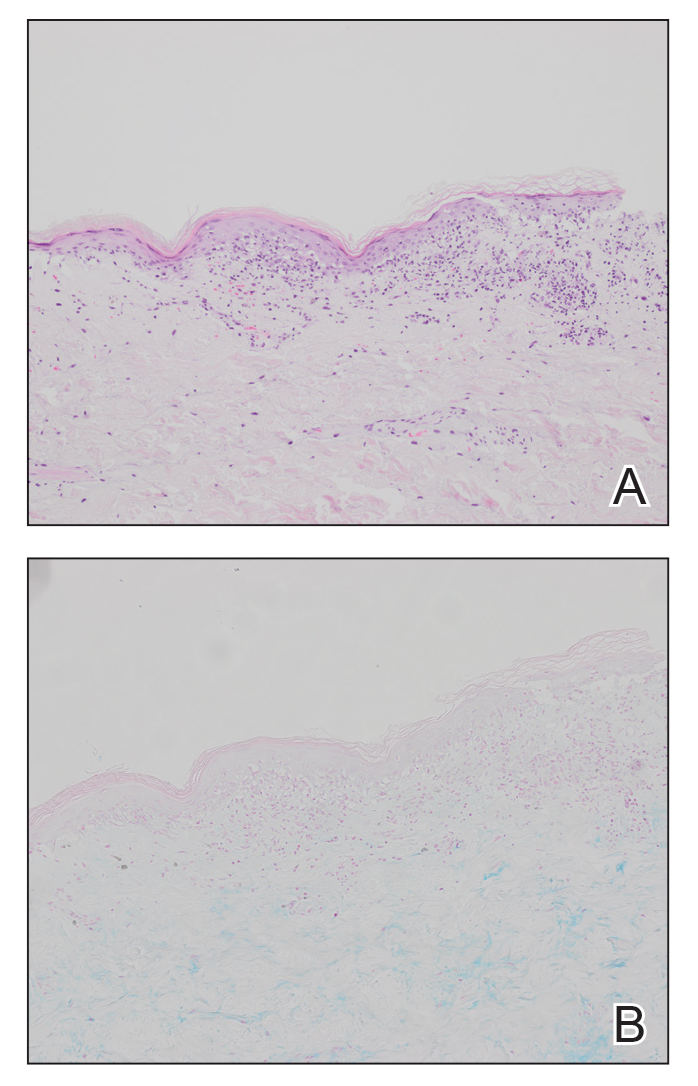

Alopecia areata is an immune-mediated disorder characterized by nonscarring hair loss; it affects approximately 0.1% to 0.2% of the general population.15 The pathogenesis involves the premature transition of hair follicles in the anagen (growth) phase to the catagen ( nonproliferative/involution) and telogen (resting) phases, resulting in sudden hair shedding and decreased regrowth. Clinically, it is characterized by asymptomatic hair loss that occurs most frequently on the scalp and other areas of the head, including eyelashes, eyebrows, and facial hair, but also can occur on the extremities. There are several variants; the most common is patchy alopecia, which features smooth circular areas of hair loss that progress over several weeks. Some patients can progress to loss of all scalp hairs (alopecia totalis) or all hairs throughout the body (alopecia universalis). 15 Patients typically will have spontaneous regrowth of hair, with up to 50% of those with limited hair loss recovering within a year.16 The disease has a chronic/ relapsing course, and patients often will have multiple episodes of hair loss. Histopathologic features can vary depending on the stage of disease. In acute cases, a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate preferentially involving anagen-stage hair follicles is seen, with associated necrosis, edema, and pigment incontinence (Figure 3).16 In chronic alopecia areata, the inflammation may be less brisk, and follicular miniaturization often is seen. Additionally, increased proportions of catagen- or telogen-stage follicles are present.16,17 On immunohistochemistry, lymphocytes express both CD4 and CD8, with a slightly increased CD4:CD8 ratio in active disease.18

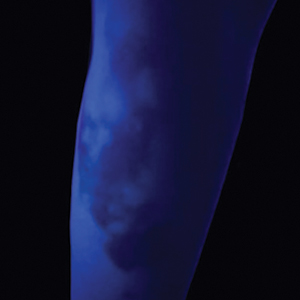

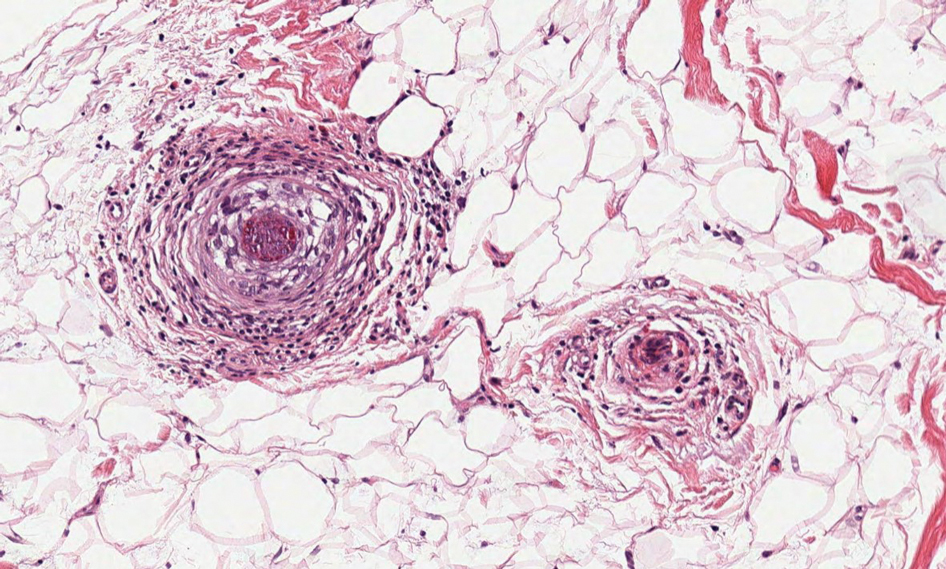

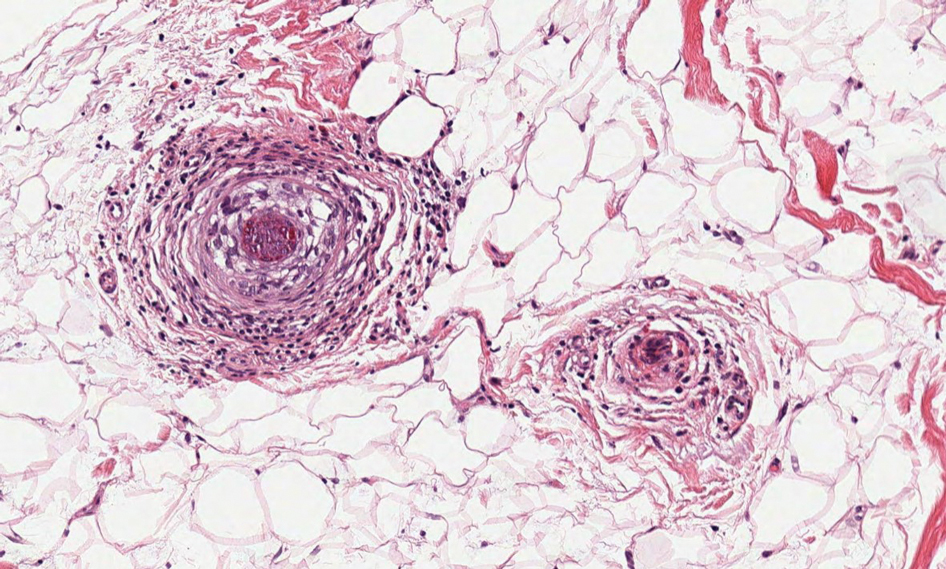

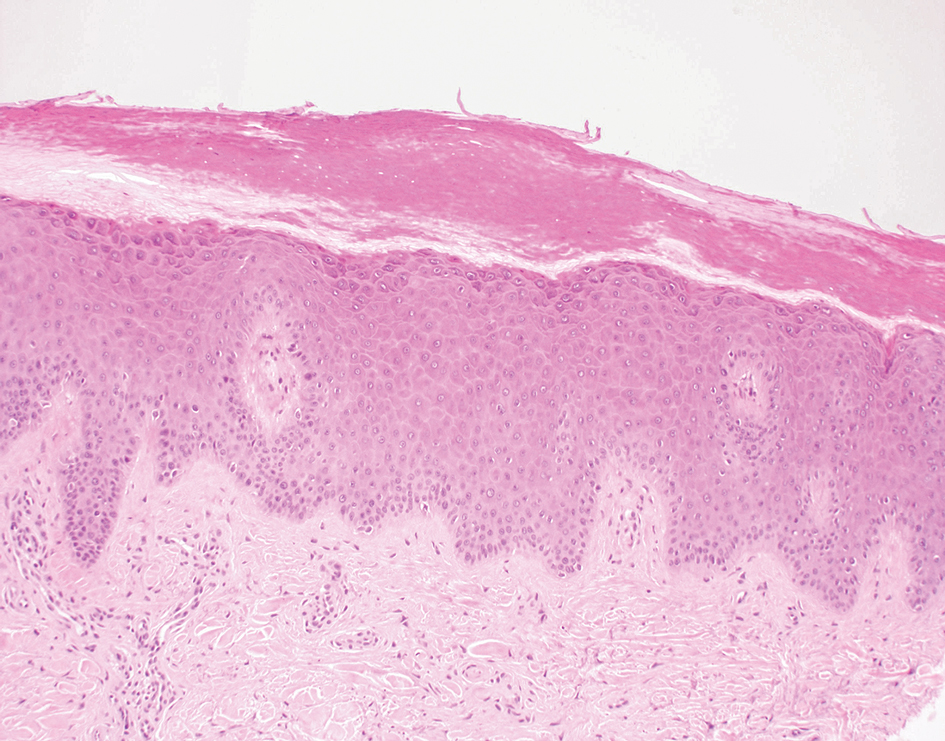

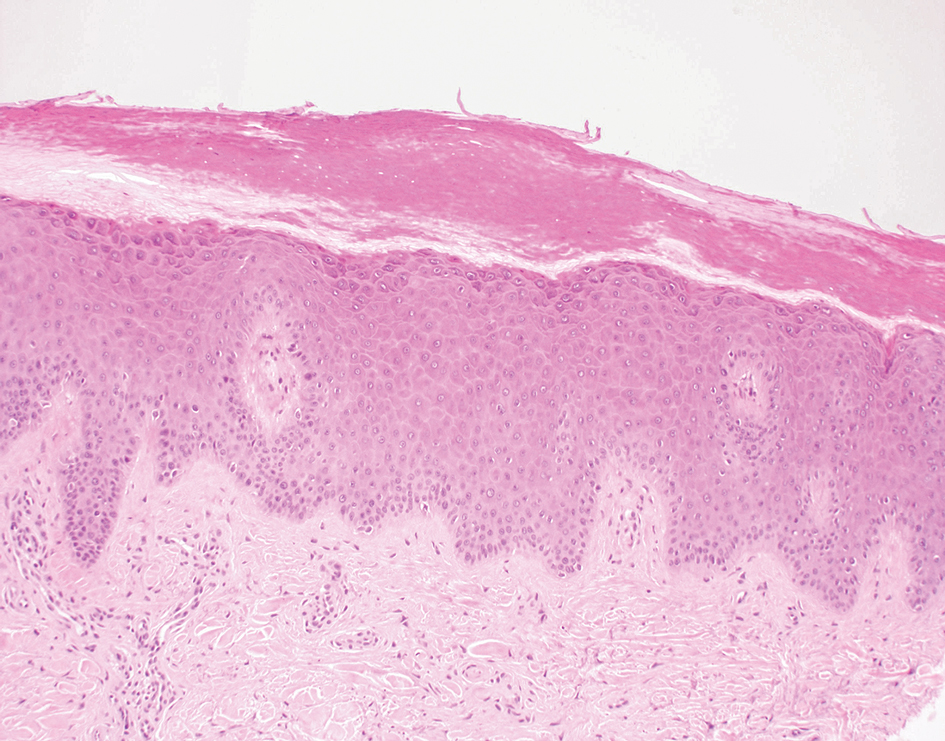

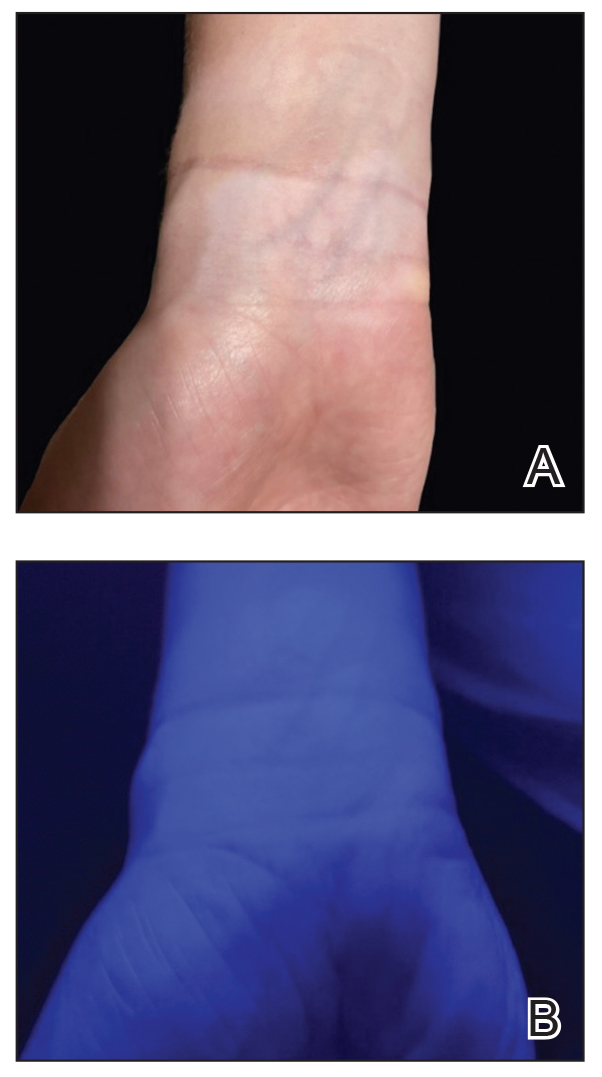

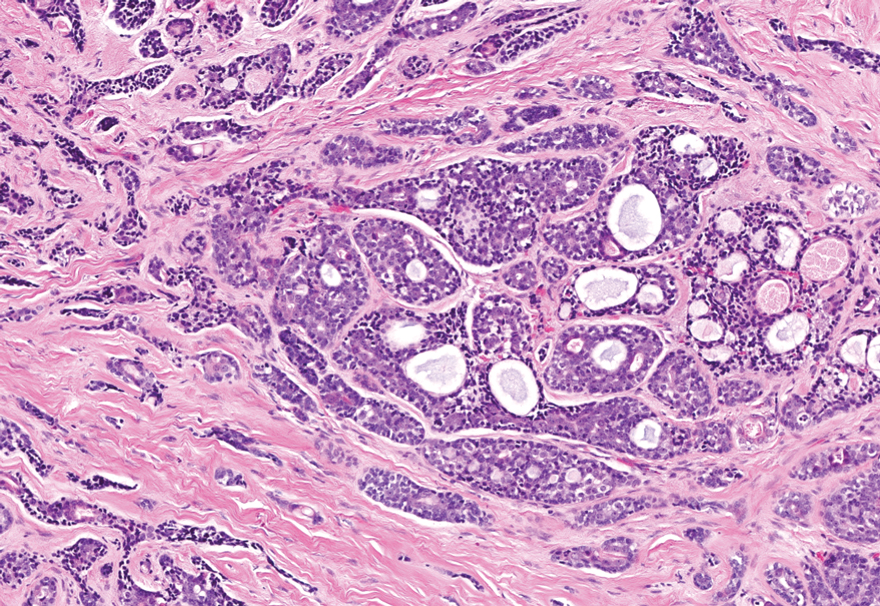

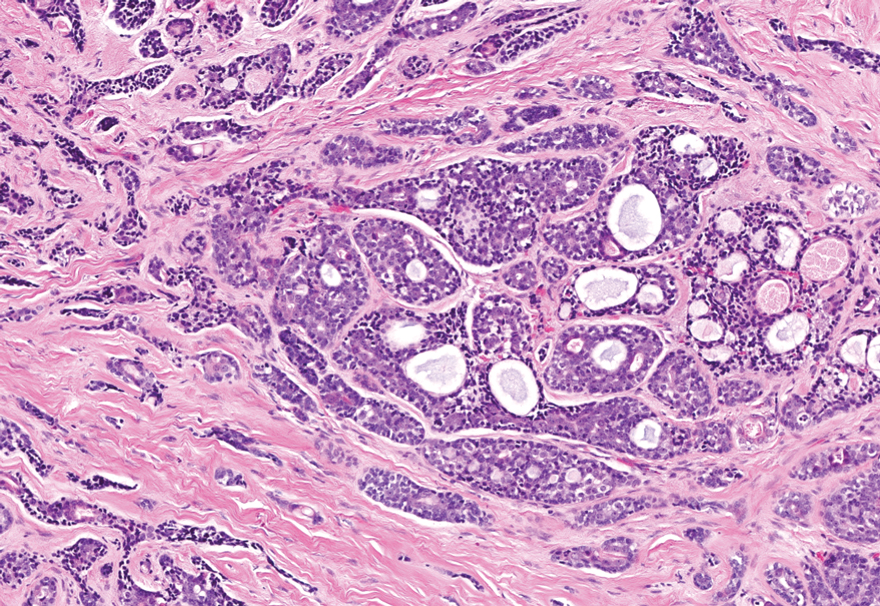

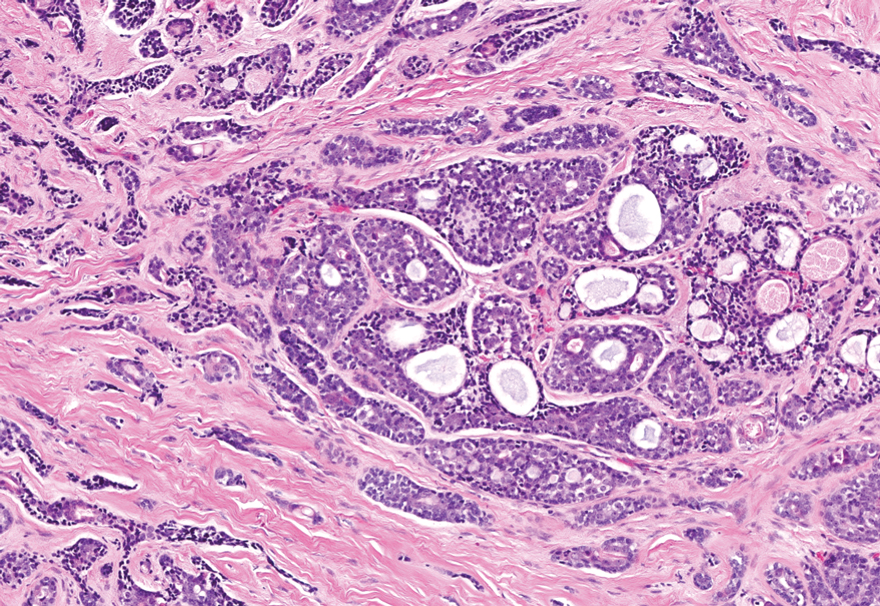

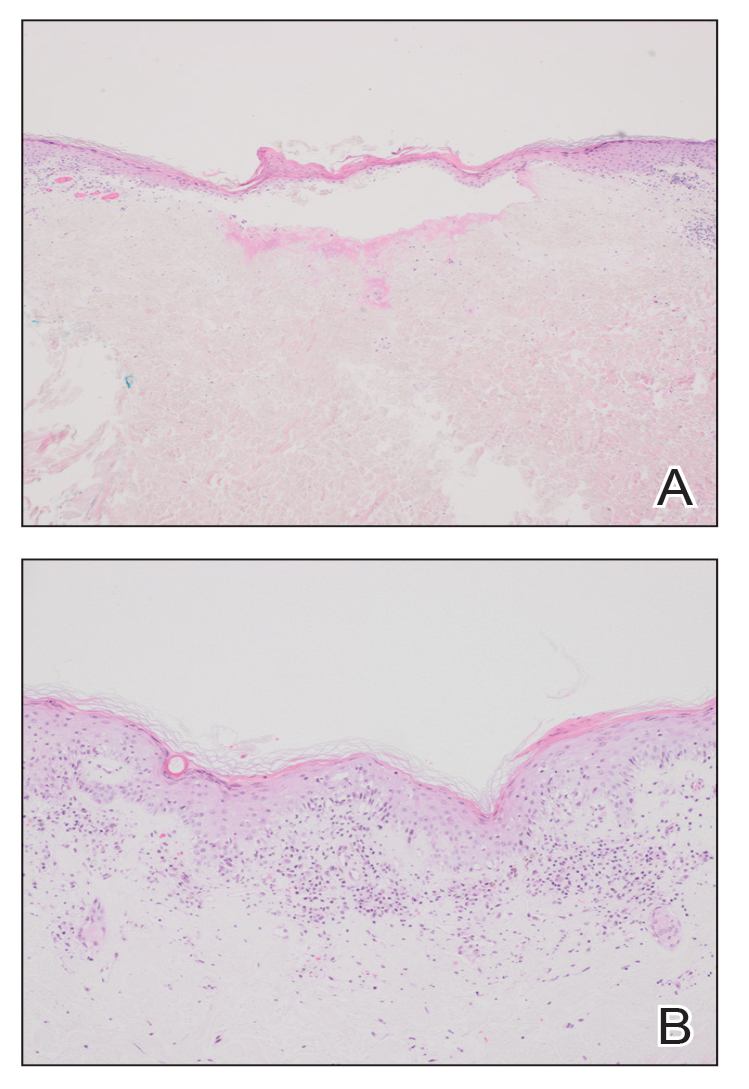

Psoriatic alopecia describes hair loss that occurs in patients with psoriasis. Patients present with scaly, erythematous, psoriasiform plaques or patches, as well as decreased hair density, finer hairs, and increased dystrophic hair bulbs within the psoriatic plaques.19 It often is nonscarring and resolves with therapy, though scarring may occur with secondary infection. Psoriatic alopecia may occur in the setting of classic psoriasis and also may occur in psoriasiform drug eruptions, including those caused by tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.20,21 Histologic features include atrophy of sebaceous glands, epidermal changes with hypogranulosis and psoriasiform hyperplasia, decreased hair follicle density, and neutrophils in the stratum spinosum (Figure 4). There often is associated perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation with small lymphocytes that do not have notable morphologic abnormalities.

- Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133:1703-1714. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268

- Malveira MIB, Pascoal G, Gamonal SBL, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: challenging clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):73-75. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175634

- Flaig MJ, Cerroni L, Schuhmann K, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a histopathologic analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:525- 530. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.281006.x

- van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:191-198. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.2.191

- van Santen S, Roach REJ, van Doorn R, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic factors in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:992-1000. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1597

- Lehman JS, Cook-Norris RH, Weed BR, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: single-center study and systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:607-613. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.101

- Gerami P, Rosen S, Kuzel T, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: an aggressive variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:738-746. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.6.738

- Büchner SA, Meier M, Rufli TH. Follicular mucinosis associated with mycosis fungoides. Dermatology. 1991;183:66-67. doi:10.1159/000247639

- Akinsanya AO, Tschen JA. Follicular mucinosis: a case report. Cureus. 2019;11:E4746. doi:10.7759/cureus.4746

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:15-19. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01338.x

- Khalil J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Follicular mucinosis: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:159-165. doi:10.1111/ijd.15165

- Zvulunov A, Shkalim V, Ben-Amitai D, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of alopecia mucinosa/follicular mucinosis and its natural history in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1174-1181. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.015

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:343-351. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001

- Gupta AK, Bluhm R. Seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:13-26; quiz 19-20. doi:10.1111/j .1468-3083.2004.00693.x

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1-12. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2017.04.1141

- Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, et al. Alopecia areata update: part I. clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177-88, quiz 189-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032

- Whiting DA. Histopathologic features of alopecia areata: a new look. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1555-1559. doi:10.1001/archderm .139.12.1555

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 pt 1):216-223. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(84)70152-6

- George SM, Taylor MR, Farrant PB. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721. doi:10.1111/ced.12715

- Afaasiev OK, Zhang CZ, Ruhoy SM. TNF-inhibitor associated psoriatic alopecia: diagnostic utility of sebaceous lobule atrophy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:563-539. doi:10.1111/cup.12932

- Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, et al. Psoriatic alopecia—fact or fiction? A clinicohistologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:611-619. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.100574

The Diagnosis: Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) characterized by folliculotropism and follicular-based lesions. The clinical manifestation of FMF can vary and includes patches, plaques, or tumors resembling nonfolliculotropic MF; acneform lesions including comedones and pustules; or areas of alopecia. Lesions commonly involve the head and neck but also can be seen on the trunk or extremities. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides can be accompanied by pruritus or superimposed secondary infection.

Histologic features of FMF include follicular (perifollicular or intrafollicular) infiltration by atypical T cells showing cerebriform nuclei.1 In early lesions, there may be only mild superficial perivascular inflammation without notable lymphocyte atypia, making diagnosis challenging. 2,3 Mucinous degeneration of the follicles—termed follicular mucinosis—is a common histologic finding in FMF.1,2 Follicular mucinosis is not exclusive to FMF; it can be primary/idiopathic or secondary to underlying inflammatory or neoplastic disorders such as FMF. On immunohistochemistry, FMF most commonly demonstrates a helper T cell phenotype that is positive for CD3 and CD4 and negative for CD8, with aberrant loss of CD7 and variably CD5, which is similar to classic MF. Occasionally, larger CD30+ cells also can be present in the dermis. T-cell gene rearrangement studies will demonstrate T-cell receptor clonality in most cases.2

Many large retrospective cohort studies have suggested that patients with FMF have a worse prognosis than classic MF, with a 5-year survival rate of 62% to 87% for early-stage FMF vs more than 90% for classic patchand plaque-stage MF.4-7 However, a 2016 study suggested histologic evaluation may be able to further differentiate clinically identical cases into indolent and aggressive forms of FMF with considerably different outcomes based on the density of the perifollicular infiltrate.5 The presence of follicular mucinosis has no impact on prognosis compared to cases without follicular mucinosis.1,2

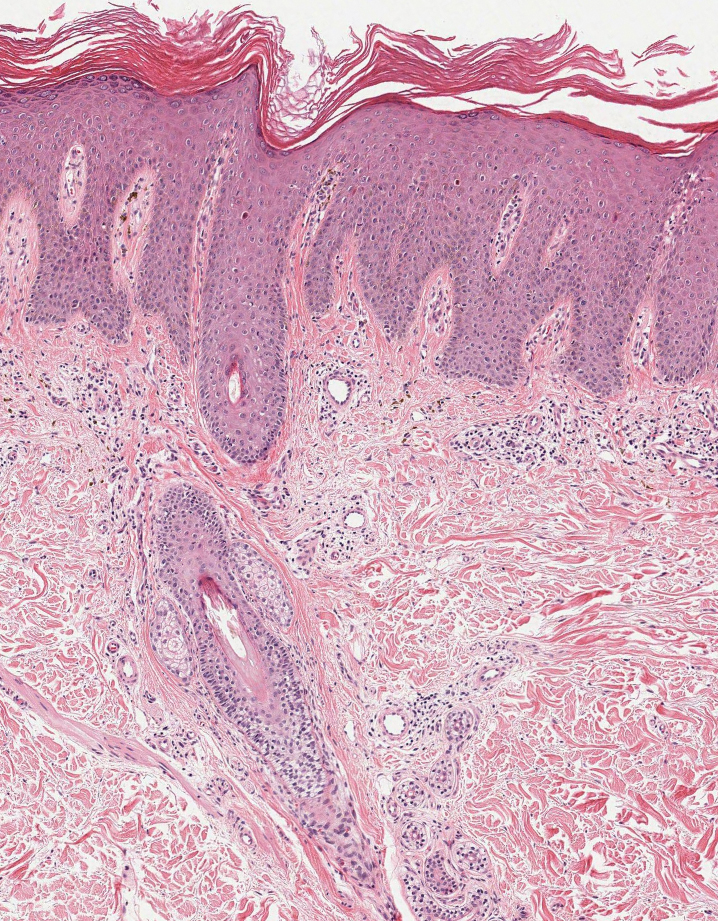

Alopecia mucinosa is characterized by infiltrating, erythematous, scaling plaques localized to the head and neck.8 It is diagnosed clinically, and histopathology shows follicular mucinosis. The terms alopecia mucinosa and follicular mucinosis often are used interchangeably. Over the past few decades, 3 variants have been categorized: primary acute, primary chronic, and secondary. The primary acute form manifests in children and young adults as solitary lesions, which often resolve spontaneously. In contrast, the primary chronic form manifests in older adults as multiple disseminated lesions with a chronic relapsing course.8,9 The secondary form can occur in the setting of other disorders, including lupus erythematosus, hypertrophic lichen planus, alopecia areata, and neoplasms such as MF or Hodgkin lymphoma.9 The histopathologic findings are similar for all types of alopecia mucinosa, with cystic pools of mucin deposition in the sebaceous glands and external root sheath of the follicles as well as associated inflammation composed of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1).9,10 The inflammatory infiltrate rarely extends into the epidermis or upper portion of the hair follicle. Although histopathology alone cannot reliably distinguish between primary and secondary forms of alopecia mucinosa, MF (including follicular MF) or another underlying cutaneous T-cell lymphoma should be considered if inflammation extends into the upper dermis, epidermis, or follicles or is in a dense bandlike distribution.11 On immunohistochemistry, lymphocytes should show positivity for CD3, CD4, and CD8. The CD4:CD8 ratio often is 1:1 in alopecia mucinosa, while in FMF it is approximately 3:1.10 CD7 commonly is negative but can be present in a small percentage of cases.12 T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies have detected clonality in both primary and secondary alopecia mucinosa and thus cannot be used alone to distinguish between the two.10 Given the overlap in histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of primary and secondary alopecia mucinosa, definitive diagnosis cannot be made with any single modality and should be based on correlating clinical presentation, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analyses.

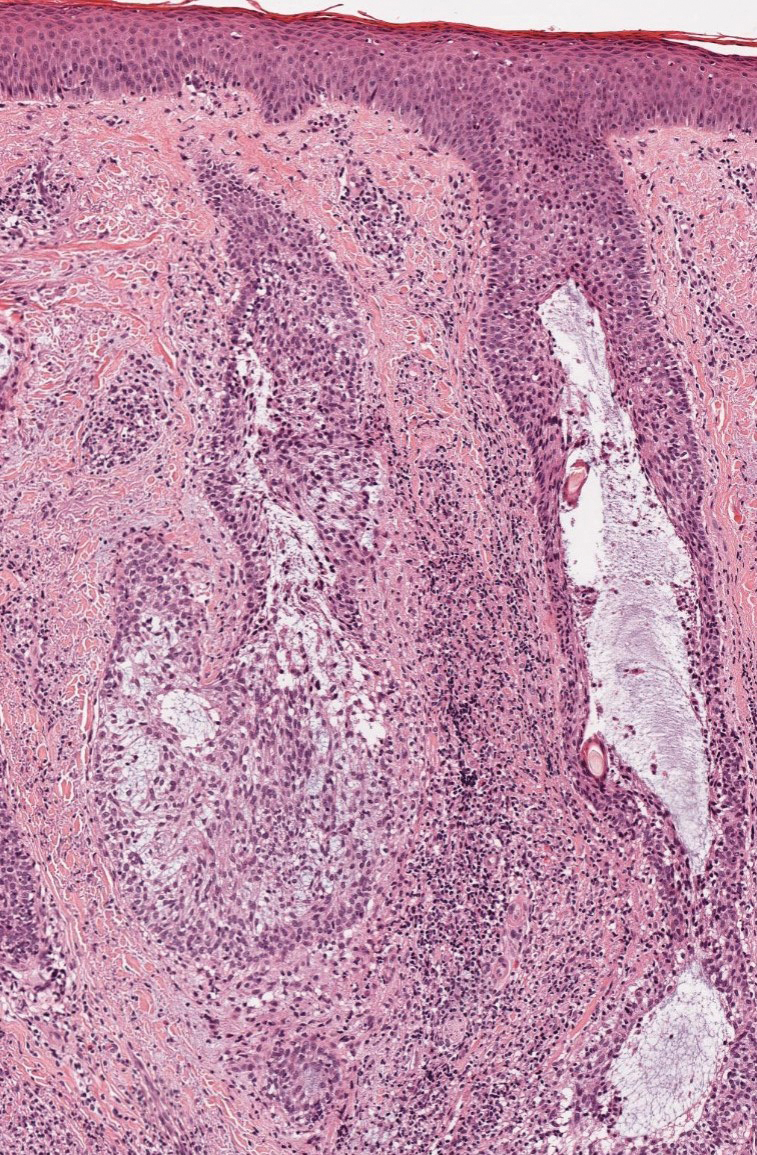

Inflammatory dermatoses including seborrheic dermatitis also are in the differential diagnosis for FMF. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting 1% to 3% of the general population. 13 Patients usually present with scaly and greasy plaques and papules localized to areas with increased sebaceous glands and high sebum production such as the face, scalp, and intertriginous regions. The distribution often is symmetrical, and the severity of disease can vary substantially.13 Sebopsoriasis is an entity with overlapping features of seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis, including thicker, more erythematous plaques that are more elevated. Histopathology of seborrheic dermatitis reveals spongiotic inflammation in the epidermis characterized by rounding of the keratinocytes, widening of the intercellular spaces, and accumulation of intracellular edema, causing the formation of clear spaces in the epidermis (Figure 2). Focal parakeratosis, usually in the follicular ostia, and mounds of scaly crust often are present. 14 A periodic acid–Schiff stain should be performed to rule out infectious dermatophytes, which can show similar clinical and histologic features. More chronic cases of seborrheic dermatitis often can take on histologic features of psoriasis, namely epidermal hyperplasia with thinning over dermal papillae, though the hyperplasia in psoriasis is more regular.

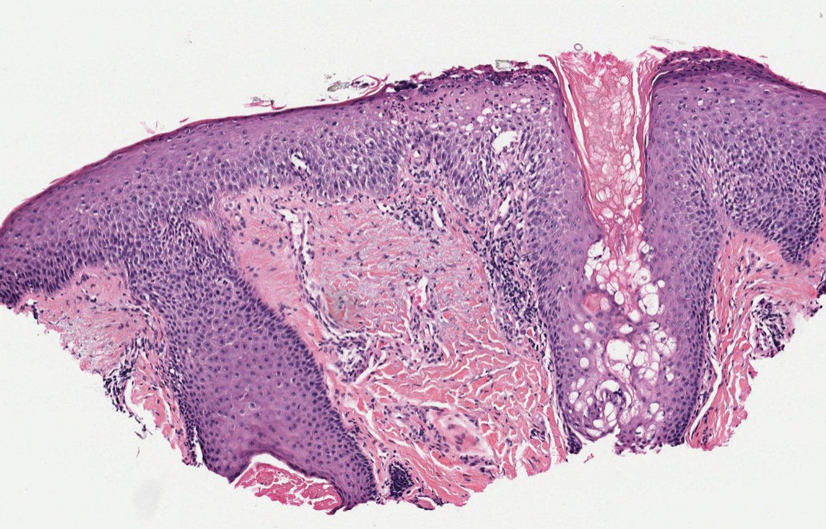

Alopecia areata is an immune-mediated disorder characterized by nonscarring hair loss; it affects approximately 0.1% to 0.2% of the general population.15 The pathogenesis involves the premature transition of hair follicles in the anagen (growth) phase to the catagen ( nonproliferative/involution) and telogen (resting) phases, resulting in sudden hair shedding and decreased regrowth. Clinically, it is characterized by asymptomatic hair loss that occurs most frequently on the scalp and other areas of the head, including eyelashes, eyebrows, and facial hair, but also can occur on the extremities. There are several variants; the most common is patchy alopecia, which features smooth circular areas of hair loss that progress over several weeks. Some patients can progress to loss of all scalp hairs (alopecia totalis) or all hairs throughout the body (alopecia universalis). 15 Patients typically will have spontaneous regrowth of hair, with up to 50% of those with limited hair loss recovering within a year.16 The disease has a chronic/ relapsing course, and patients often will have multiple episodes of hair loss. Histopathologic features can vary depending on the stage of disease. In acute cases, a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate preferentially involving anagen-stage hair follicles is seen, with associated necrosis, edema, and pigment incontinence (Figure 3).16 In chronic alopecia areata, the inflammation may be less brisk, and follicular miniaturization often is seen. Additionally, increased proportions of catagen- or telogen-stage follicles are present.16,17 On immunohistochemistry, lymphocytes express both CD4 and CD8, with a slightly increased CD4:CD8 ratio in active disease.18

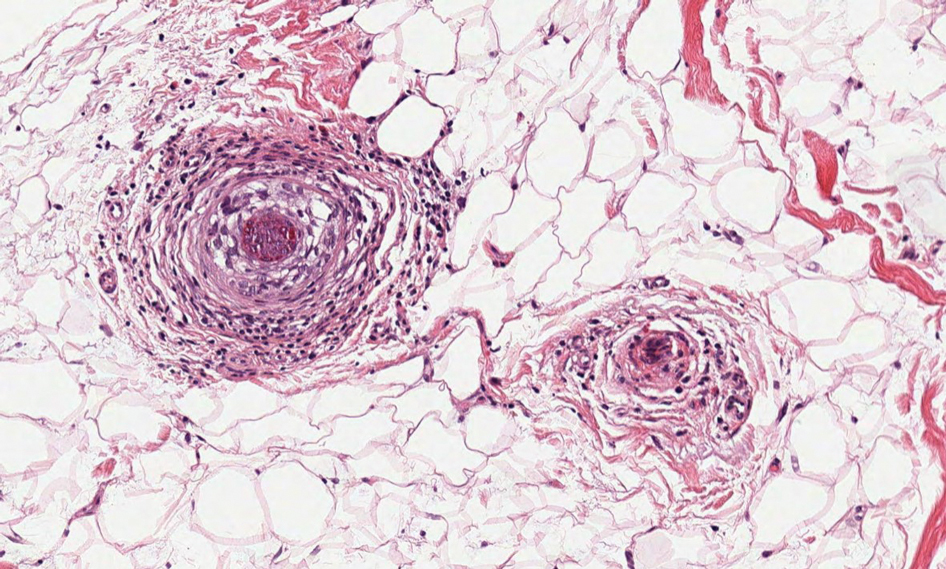

Psoriatic alopecia describes hair loss that occurs in patients with psoriasis. Patients present with scaly, erythematous, psoriasiform plaques or patches, as well as decreased hair density, finer hairs, and increased dystrophic hair bulbs within the psoriatic plaques.19 It often is nonscarring and resolves with therapy, though scarring may occur with secondary infection. Psoriatic alopecia may occur in the setting of classic psoriasis and also may occur in psoriasiform drug eruptions, including those caused by tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.20,21 Histologic features include atrophy of sebaceous glands, epidermal changes with hypogranulosis and psoriasiform hyperplasia, decreased hair follicle density, and neutrophils in the stratum spinosum (Figure 4). There often is associated perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation with small lymphocytes that do not have notable morphologic abnormalities.

The Diagnosis: Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) characterized by folliculotropism and follicular-based lesions. The clinical manifestation of FMF can vary and includes patches, plaques, or tumors resembling nonfolliculotropic MF; acneform lesions including comedones and pustules; or areas of alopecia. Lesions commonly involve the head and neck but also can be seen on the trunk or extremities. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides can be accompanied by pruritus or superimposed secondary infection.

Histologic features of FMF include follicular (perifollicular or intrafollicular) infiltration by atypical T cells showing cerebriform nuclei.1 In early lesions, there may be only mild superficial perivascular inflammation without notable lymphocyte atypia, making diagnosis challenging. 2,3 Mucinous degeneration of the follicles—termed follicular mucinosis—is a common histologic finding in FMF.1,2 Follicular mucinosis is not exclusive to FMF; it can be primary/idiopathic or secondary to underlying inflammatory or neoplastic disorders such as FMF. On immunohistochemistry, FMF most commonly demonstrates a helper T cell phenotype that is positive for CD3 and CD4 and negative for CD8, with aberrant loss of CD7 and variably CD5, which is similar to classic MF. Occasionally, larger CD30+ cells also can be present in the dermis. T-cell gene rearrangement studies will demonstrate T-cell receptor clonality in most cases.2

Many large retrospective cohort studies have suggested that patients with FMF have a worse prognosis than classic MF, with a 5-year survival rate of 62% to 87% for early-stage FMF vs more than 90% for classic patchand plaque-stage MF.4-7 However, a 2016 study suggested histologic evaluation may be able to further differentiate clinically identical cases into indolent and aggressive forms of FMF with considerably different outcomes based on the density of the perifollicular infiltrate.5 The presence of follicular mucinosis has no impact on prognosis compared to cases without follicular mucinosis.1,2

Alopecia mucinosa is characterized by infiltrating, erythematous, scaling plaques localized to the head and neck.8 It is diagnosed clinically, and histopathology shows follicular mucinosis. The terms alopecia mucinosa and follicular mucinosis often are used interchangeably. Over the past few decades, 3 variants have been categorized: primary acute, primary chronic, and secondary. The primary acute form manifests in children and young adults as solitary lesions, which often resolve spontaneously. In contrast, the primary chronic form manifests in older adults as multiple disseminated lesions with a chronic relapsing course.8,9 The secondary form can occur in the setting of other disorders, including lupus erythematosus, hypertrophic lichen planus, alopecia areata, and neoplasms such as MF or Hodgkin lymphoma.9 The histopathologic findings are similar for all types of alopecia mucinosa, with cystic pools of mucin deposition in the sebaceous glands and external root sheath of the follicles as well as associated inflammation composed of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1).9,10 The inflammatory infiltrate rarely extends into the epidermis or upper portion of the hair follicle. Although histopathology alone cannot reliably distinguish between primary and secondary forms of alopecia mucinosa, MF (including follicular MF) or another underlying cutaneous T-cell lymphoma should be considered if inflammation extends into the upper dermis, epidermis, or follicles or is in a dense bandlike distribution.11 On immunohistochemistry, lymphocytes should show positivity for CD3, CD4, and CD8. The CD4:CD8 ratio often is 1:1 in alopecia mucinosa, while in FMF it is approximately 3:1.10 CD7 commonly is negative but can be present in a small percentage of cases.12 T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies have detected clonality in both primary and secondary alopecia mucinosa and thus cannot be used alone to distinguish between the two.10 Given the overlap in histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of primary and secondary alopecia mucinosa, definitive diagnosis cannot be made with any single modality and should be based on correlating clinical presentation, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analyses.

Inflammatory dermatoses including seborrheic dermatitis also are in the differential diagnosis for FMF. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting 1% to 3% of the general population. 13 Patients usually present with scaly and greasy plaques and papules localized to areas with increased sebaceous glands and high sebum production such as the face, scalp, and intertriginous regions. The distribution often is symmetrical, and the severity of disease can vary substantially.13 Sebopsoriasis is an entity with overlapping features of seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis, including thicker, more erythematous plaques that are more elevated. Histopathology of seborrheic dermatitis reveals spongiotic inflammation in the epidermis characterized by rounding of the keratinocytes, widening of the intercellular spaces, and accumulation of intracellular edema, causing the formation of clear spaces in the epidermis (Figure 2). Focal parakeratosis, usually in the follicular ostia, and mounds of scaly crust often are present. 14 A periodic acid–Schiff stain should be performed to rule out infectious dermatophytes, which can show similar clinical and histologic features. More chronic cases of seborrheic dermatitis often can take on histologic features of psoriasis, namely epidermal hyperplasia with thinning over dermal papillae, though the hyperplasia in psoriasis is more regular.

Alopecia areata is an immune-mediated disorder characterized by nonscarring hair loss; it affects approximately 0.1% to 0.2% of the general population.15 The pathogenesis involves the premature transition of hair follicles in the anagen (growth) phase to the catagen ( nonproliferative/involution) and telogen (resting) phases, resulting in sudden hair shedding and decreased regrowth. Clinically, it is characterized by asymptomatic hair loss that occurs most frequently on the scalp and other areas of the head, including eyelashes, eyebrows, and facial hair, but also can occur on the extremities. There are several variants; the most common is patchy alopecia, which features smooth circular areas of hair loss that progress over several weeks. Some patients can progress to loss of all scalp hairs (alopecia totalis) or all hairs throughout the body (alopecia universalis). 15 Patients typically will have spontaneous regrowth of hair, with up to 50% of those with limited hair loss recovering within a year.16 The disease has a chronic/ relapsing course, and patients often will have multiple episodes of hair loss. Histopathologic features can vary depending on the stage of disease. In acute cases, a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate preferentially involving anagen-stage hair follicles is seen, with associated necrosis, edema, and pigment incontinence (Figure 3).16 In chronic alopecia areata, the inflammation may be less brisk, and follicular miniaturization often is seen. Additionally, increased proportions of catagen- or telogen-stage follicles are present.16,17 On immunohistochemistry, lymphocytes express both CD4 and CD8, with a slightly increased CD4:CD8 ratio in active disease.18

Psoriatic alopecia describes hair loss that occurs in patients with psoriasis. Patients present with scaly, erythematous, psoriasiform plaques or patches, as well as decreased hair density, finer hairs, and increased dystrophic hair bulbs within the psoriatic plaques.19 It often is nonscarring and resolves with therapy, though scarring may occur with secondary infection. Psoriatic alopecia may occur in the setting of classic psoriasis and also may occur in psoriasiform drug eruptions, including those caused by tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.20,21 Histologic features include atrophy of sebaceous glands, epidermal changes with hypogranulosis and psoriasiform hyperplasia, decreased hair follicle density, and neutrophils in the stratum spinosum (Figure 4). There often is associated perifollicular lymphocytic inflammation with small lymphocytes that do not have notable morphologic abnormalities.

- Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133:1703-1714. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268

- Malveira MIB, Pascoal G, Gamonal SBL, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: challenging clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):73-75. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175634

- Flaig MJ, Cerroni L, Schuhmann K, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a histopathologic analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:525- 530. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.281006.x

- van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:191-198. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.2.191

- van Santen S, Roach REJ, van Doorn R, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic factors in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:992-1000. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1597

- Lehman JS, Cook-Norris RH, Weed BR, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: single-center study and systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:607-613. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.101

- Gerami P, Rosen S, Kuzel T, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: an aggressive variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:738-746. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.6.738

- Büchner SA, Meier M, Rufli TH. Follicular mucinosis associated with mycosis fungoides. Dermatology. 1991;183:66-67. doi:10.1159/000247639

- Akinsanya AO, Tschen JA. Follicular mucinosis: a case report. Cureus. 2019;11:E4746. doi:10.7759/cureus.4746

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:15-19. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01338.x

- Khalil J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Follicular mucinosis: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:159-165. doi:10.1111/ijd.15165

- Zvulunov A, Shkalim V, Ben-Amitai D, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of alopecia mucinosa/follicular mucinosis and its natural history in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1174-1181. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.015

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:343-351. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001

- Gupta AK, Bluhm R. Seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:13-26; quiz 19-20. doi:10.1111/j .1468-3083.2004.00693.x

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1-12. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2017.04.1141

- Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, et al. Alopecia areata update: part I. clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177-88, quiz 189-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032

- Whiting DA. Histopathologic features of alopecia areata: a new look. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1555-1559. doi:10.1001/archderm .139.12.1555

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 pt 1):216-223. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(84)70152-6

- George SM, Taylor MR, Farrant PB. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721. doi:10.1111/ced.12715

- Afaasiev OK, Zhang CZ, Ruhoy SM. TNF-inhibitor associated psoriatic alopecia: diagnostic utility of sebaceous lobule atrophy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:563-539. doi:10.1111/cup.12932

- Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, et al. Psoriatic alopecia—fact or fiction? A clinicohistologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:611-619. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.100574

- Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133:1703-1714. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268

- Malveira MIB, Pascoal G, Gamonal SBL, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: challenging clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):73-75. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175634

- Flaig MJ, Cerroni L, Schuhmann K, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a histopathologic analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:525- 530. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.281006.x

- van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides: a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:191-198. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.2.191

- van Santen S, Roach REJ, van Doorn R, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic factors in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:992-1000. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1597

- Lehman JS, Cook-Norris RH, Weed BR, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: single-center study and systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:607-613. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.101

- Gerami P, Rosen S, Kuzel T, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: an aggressive variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:738-746. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.6.738

- Büchner SA, Meier M, Rufli TH. Follicular mucinosis associated with mycosis fungoides. Dermatology. 1991;183:66-67. doi:10.1159/000247639

- Akinsanya AO, Tschen JA. Follicular mucinosis: a case report. Cureus. 2019;11:E4746. doi:10.7759/cureus.4746

- Rongioletti F, De Lucchi S, Meyes D, et al. Follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic, histochemical, immunohistochemical and molecular study comparing the primary benign form and the mycosis fungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:15-19. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01338.x

- Khalil J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Follicular mucinosis: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:159-165. doi:10.1111/ijd.15165

- Zvulunov A, Shkalim V, Ben-Amitai D, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of alopecia mucinosa/follicular mucinosis and its natural history in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1174-1181. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.015

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:343-351. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001

- Gupta AK, Bluhm R. Seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:13-26; quiz 19-20. doi:10.1111/j .1468-3083.2004.00693.x

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1-12. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2017.04.1141

- Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, et al. Alopecia areata update: part I. clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177-88, quiz 189-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032

- Whiting DA. Histopathologic features of alopecia areata: a new look. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1555-1559. doi:10.1001/archderm .139.12.1555

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 pt 1):216-223. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(84)70152-6

- George SM, Taylor MR, Farrant PB. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:717-721. doi:10.1111/ced.12715

- Afaasiev OK, Zhang CZ, Ruhoy SM. TNF-inhibitor associated psoriatic alopecia: diagnostic utility of sebaceous lobule atrophy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:563-539. doi:10.1111/cup.12932

- Silva CY, Brown KL, Kurban AK, et al. Psoriatic alopecia—fact or fiction? A clinicohistologic reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:611-619. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.100574