User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Immunotherapy should not be withheld because of sex, age, or PS

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

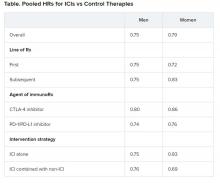

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Aspirin may accelerate cancer progression in older adults

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Tailored messaging needed to get cancer screening back on track

In late June, Lisa Richardson, MD, emerged from Atlanta, Georgia’s initial COVID-19 lockdown, and “got back out there” for some overdue doctor’s appointments, including a mammogram.

The mammogram was a particular priority for her, since she is director of the CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. But she knows that cancer screening is going to be a much tougher sell for the average person going forward in the pandemic era.

“It really is a challenge trying to get people to feel comfortable coming back in to be screened,” she said. Richardson was speaking recently at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer, a virtual symposium on cancer prevention and early detection in the COVID-19 pandemic organized by the American Association for Cancer Research.

While health service shutdowns and stay-at-home orders forced the country’s initial precipitous decline in cancer screening, fear of contracting COVID-19 is a big part of what is preventing patients from returning.

“We’ve known even pre-pandemic that people were hesitant to do cancer screening and in some ways this has really given them an out to say, ‘Well, I’m going to hold off on that colonoscopy,’ ” Amy Leader, MD, from Thomas Jefferson University’s Kimmel Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, said during the symposium.

Estimating the pandemic’s impact on cancer care

While the impact of the pandemic on cancer can only be estimated at the moment, the prospects are already daunting, said Richardson, speculating that the hard-won 26% drop in cancer mortality over the past two decades “may be put on hold or reversed” by COVID-19.

There could be as many as 10,000 excess deaths in the US from colorectal and breast cancer alone because of COVID-19 delays, predicted Norman E. Sharpless, director of the US National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

But even Sharpless acknowledges that his modeling gives a conservative estimate, “as it does not consider other cancer types, it does not account for the additional nonlethal morbidity from upstaging, and it assumes a moderate disruption in care that completely resolves after 6 months.”

With still no end to the pandemic in sight, the true scope of cancer screening and treatment disruptions will take a long time to assess, but several studies presented during the symposium revealed some early indications.

A national survey launched in mid-May, which involved 534 women either diagnosed with breast cancer or undergoing screening or diagnostic evaluation for it, found that delays in screening were reported by 31.7% of those with breast cancer, and 26.7% of those without. Additionally, 21% of those on active treatment for breast cancer reported treatment delays.

“It’s going to be really important to implement strategies to help patients return to care ... creating a culture and a feeling of safety among patients and communicating through the uncertainty that exists in the pandemic,” said study investigator Erica T. Warner, ScD MPH, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Screening for prostate cancer (via prostate-specific antigen testing) also declined, though not as dramatically as that for breast cancer, noted Mara Epstein, ScD, from The Meyers Primary Care Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. Her study at a large healthcare provider group compared rates of both screening and diagnostic mammographies, and also PSA testing, as well as breast and prostate biopsies in the first five months of 2020 vs the same months in 2019.

While a decrease from 2019 to 2020 was seen in all procedures over the entire study period, the greatest decline was seen in April for screening mammography (down 98%), and tomosynthesis (down 96%), as well as PSA testing (down 83%), she said.

More recent figures are hard to come by, but a recent weekly survey from the Primary Care Collaborative shows 46% of practices are offering preventive and chronic care management visits, but patients are not scheduling them, and 44% report that in-person visit volume is between 30%-50% below normal over the last 4 weeks.

Will COVID-19 exacerbate racial disparities in cancer?

Neither of the studies presented at the symposium analyzed cancer care disruptions by race, but there was concern among some panelists that cancer care disparities that existed before the pandemic will be magnified further.

“Over the next several months and into the next year there’s going to be some catch-up in screening and treatment, and one of my concerns is minority and underserved populations will not partake in that catch-up the way many middle-class Americans will,” said Otis Brawley, MD, from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

There is ample evidence that minority populations have been disproportionately hit by COVID-19, job losses, and lost health insurance, said the CDC’s Richardson, and all these factors could widen the cancer gap.

“It’s not a race thing, it’s a ‘what do you do thing,’ and an access to care thing, and what your socioeconomic status is,” Richardson said in an interview. “People who didn’t have sick leave before the pandemic still don’t have sick leave; if they didn’t have time to get their mammogram they still don’t have time.”

But she acknowledges that evidence is still lacking. Could some minority populations actually be less fearful of medical encounters because their work has already prevented them from sheltering in place? “It could go either way,” she said. “They might be less wary of venturing out into the clinic, but they also might reason that they’ve exposed themselves enough already at work and don’t want any additional exposure.”

In that regard, Richardson suggests population-specific messaging will be an important way of communicating with under-served populations to restart screening.

“We’re struggling at CDC with how to develop messages that resonate within different communities, because we’re missing the point of actually speaking to people within their culture and within the places that they live,” she said. “Just saying the same thing and putting a black face on it is not going to make a difference; you actually have to speak the language of the people you’re trying to reach — the same message in different packages.”

To that end, even before the pandemic, the CDC supported the development of Make It Your Own, a website that uses “evidence-based strategies” to assist healthcare organizations in customizing health information “by race, ethnicity, age, gender and location”, and target messages to “specific populations, cultural groups and languages”.

But Mass General’s Warner says she’s not sure she would argue for messages to be tailored by race, “at least not without evidence that values and priorities regarding returning to care differ between racial/ethnic groups.”

“Tailoring in the absence of data requires assumptions that may or may not be correct and ignores within-group heterogeneity,” Warner told Medscape Medical News. “However, I do believe that messaging about return to cancer screening and care should be multifaceted and use diverse imagery. This recognizes that some messages will resonate more or less with individuals based on their own characteristics, of which race may be one.”

Warner does believe in the power of tailored messaging though. “Part of the onus for healthcare institutions and providers is to make some decisions about who it is really important to bring back in soonest,” she said.

“Those are the ones we want to prioritize, as opposed to those who we want to get back into care but we don’t need to get them in right now,” Warner emphasized. “As they are balancing all the needs of their family and their community and their other needs, messaging that adds additional stress, worry, anxiety and shame is not what we want to do. So really we need to distinguish between these populations, identify the priorities, hit the hard message to people who really need it now, and encourage others to come back in as they can.”

Building trust

All the panelists agreed that building trust with the public will be key to getting cancer care back on track.

“I don’t think anyone trusts the healthcare community right now, but we already had this baseline distrust of healthcare among many minority communities, and now with COVID-19, the African American community in particular is seeing people go into the hospital and never come back,” said Richardson.

For Warner, the onus really falls on healthcare institutions. “We have to be proactive and not leave the burden of deciding when and how to return to care up to patients,” she said.

“What we need to focus on as much as possible is to get people to realize it is safe to come see the doctor,” said Johns Hopkins oncologist Brawley. “We have to make it safe for them to come see us, and then we have to convince them it is safe to come see us.”

Venturing out to her mammography appointment in early June, Richardson said she felt safe. “Everything was just the way it was supposed to be, everyone was masked, everyone was washing their hands,” she said.

Yet, by mid-June she had contracted COVID-19. “I don’t know where I got it,” she said. “No matter how careful you are, understand that if you’re in a total red spot, as I am, you can just get it.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In late June, Lisa Richardson, MD, emerged from Atlanta, Georgia’s initial COVID-19 lockdown, and “got back out there” for some overdue doctor’s appointments, including a mammogram.

The mammogram was a particular priority for her, since she is director of the CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. But she knows that cancer screening is going to be a much tougher sell for the average person going forward in the pandemic era.

“It really is a challenge trying to get people to feel comfortable coming back in to be screened,” she said. Richardson was speaking recently at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer, a virtual symposium on cancer prevention and early detection in the COVID-19 pandemic organized by the American Association for Cancer Research.

While health service shutdowns and stay-at-home orders forced the country’s initial precipitous decline in cancer screening, fear of contracting COVID-19 is a big part of what is preventing patients from returning.

“We’ve known even pre-pandemic that people were hesitant to do cancer screening and in some ways this has really given them an out to say, ‘Well, I’m going to hold off on that colonoscopy,’ ” Amy Leader, MD, from Thomas Jefferson University’s Kimmel Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, said during the symposium.

Estimating the pandemic’s impact on cancer care

While the impact of the pandemic on cancer can only be estimated at the moment, the prospects are already daunting, said Richardson, speculating that the hard-won 26% drop in cancer mortality over the past two decades “may be put on hold or reversed” by COVID-19.

There could be as many as 10,000 excess deaths in the US from colorectal and breast cancer alone because of COVID-19 delays, predicted Norman E. Sharpless, director of the US National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

But even Sharpless acknowledges that his modeling gives a conservative estimate, “as it does not consider other cancer types, it does not account for the additional nonlethal morbidity from upstaging, and it assumes a moderate disruption in care that completely resolves after 6 months.”

With still no end to the pandemic in sight, the true scope of cancer screening and treatment disruptions will take a long time to assess, but several studies presented during the symposium revealed some early indications.

A national survey launched in mid-May, which involved 534 women either diagnosed with breast cancer or undergoing screening or diagnostic evaluation for it, found that delays in screening were reported by 31.7% of those with breast cancer, and 26.7% of those without. Additionally, 21% of those on active treatment for breast cancer reported treatment delays.

“It’s going to be really important to implement strategies to help patients return to care ... creating a culture and a feeling of safety among patients and communicating through the uncertainty that exists in the pandemic,” said study investigator Erica T. Warner, ScD MPH, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Screening for prostate cancer (via prostate-specific antigen testing) also declined, though not as dramatically as that for breast cancer, noted Mara Epstein, ScD, from The Meyers Primary Care Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. Her study at a large healthcare provider group compared rates of both screening and diagnostic mammographies, and also PSA testing, as well as breast and prostate biopsies in the first five months of 2020 vs the same months in 2019.

While a decrease from 2019 to 2020 was seen in all procedures over the entire study period, the greatest decline was seen in April for screening mammography (down 98%), and tomosynthesis (down 96%), as well as PSA testing (down 83%), she said.

More recent figures are hard to come by, but a recent weekly survey from the Primary Care Collaborative shows 46% of practices are offering preventive and chronic care management visits, but patients are not scheduling them, and 44% report that in-person visit volume is between 30%-50% below normal over the last 4 weeks.

Will COVID-19 exacerbate racial disparities in cancer?

Neither of the studies presented at the symposium analyzed cancer care disruptions by race, but there was concern among some panelists that cancer care disparities that existed before the pandemic will be magnified further.

“Over the next several months and into the next year there’s going to be some catch-up in screening and treatment, and one of my concerns is minority and underserved populations will not partake in that catch-up the way many middle-class Americans will,” said Otis Brawley, MD, from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

There is ample evidence that minority populations have been disproportionately hit by COVID-19, job losses, and lost health insurance, said the CDC’s Richardson, and all these factors could widen the cancer gap.

“It’s not a race thing, it’s a ‘what do you do thing,’ and an access to care thing, and what your socioeconomic status is,” Richardson said in an interview. “People who didn’t have sick leave before the pandemic still don’t have sick leave; if they didn’t have time to get their mammogram they still don’t have time.”

But she acknowledges that evidence is still lacking. Could some minority populations actually be less fearful of medical encounters because their work has already prevented them from sheltering in place? “It could go either way,” she said. “They might be less wary of venturing out into the clinic, but they also might reason that they’ve exposed themselves enough already at work and don’t want any additional exposure.”

In that regard, Richardson suggests population-specific messaging will be an important way of communicating with under-served populations to restart screening.

“We’re struggling at CDC with how to develop messages that resonate within different communities, because we’re missing the point of actually speaking to people within their culture and within the places that they live,” she said. “Just saying the same thing and putting a black face on it is not going to make a difference; you actually have to speak the language of the people you’re trying to reach — the same message in different packages.”

To that end, even before the pandemic, the CDC supported the development of Make It Your Own, a website that uses “evidence-based strategies” to assist healthcare organizations in customizing health information “by race, ethnicity, age, gender and location”, and target messages to “specific populations, cultural groups and languages”.

But Mass General’s Warner says she’s not sure she would argue for messages to be tailored by race, “at least not without evidence that values and priorities regarding returning to care differ between racial/ethnic groups.”

“Tailoring in the absence of data requires assumptions that may or may not be correct and ignores within-group heterogeneity,” Warner told Medscape Medical News. “However, I do believe that messaging about return to cancer screening and care should be multifaceted and use diverse imagery. This recognizes that some messages will resonate more or less with individuals based on their own characteristics, of which race may be one.”

Warner does believe in the power of tailored messaging though. “Part of the onus for healthcare institutions and providers is to make some decisions about who it is really important to bring back in soonest,” she said.

“Those are the ones we want to prioritize, as opposed to those who we want to get back into care but we don’t need to get them in right now,” Warner emphasized. “As they are balancing all the needs of their family and their community and their other needs, messaging that adds additional stress, worry, anxiety and shame is not what we want to do. So really we need to distinguish between these populations, identify the priorities, hit the hard message to people who really need it now, and encourage others to come back in as they can.”

Building trust

All the panelists agreed that building trust with the public will be key to getting cancer care back on track.

“I don’t think anyone trusts the healthcare community right now, but we already had this baseline distrust of healthcare among many minority communities, and now with COVID-19, the African American community in particular is seeing people go into the hospital and never come back,” said Richardson.

For Warner, the onus really falls on healthcare institutions. “We have to be proactive and not leave the burden of deciding when and how to return to care up to patients,” she said.

“What we need to focus on as much as possible is to get people to realize it is safe to come see the doctor,” said Johns Hopkins oncologist Brawley. “We have to make it safe for them to come see us, and then we have to convince them it is safe to come see us.”

Venturing out to her mammography appointment in early June, Richardson said she felt safe. “Everything was just the way it was supposed to be, everyone was masked, everyone was washing their hands,” she said.

Yet, by mid-June she had contracted COVID-19. “I don’t know where I got it,” she said. “No matter how careful you are, understand that if you’re in a total red spot, as I am, you can just get it.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In late June, Lisa Richardson, MD, emerged from Atlanta, Georgia’s initial COVID-19 lockdown, and “got back out there” for some overdue doctor’s appointments, including a mammogram.

The mammogram was a particular priority for her, since she is director of the CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. But she knows that cancer screening is going to be a much tougher sell for the average person going forward in the pandemic era.

“It really is a challenge trying to get people to feel comfortable coming back in to be screened,” she said. Richardson was speaking recently at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer, a virtual symposium on cancer prevention and early detection in the COVID-19 pandemic organized by the American Association for Cancer Research.

While health service shutdowns and stay-at-home orders forced the country’s initial precipitous decline in cancer screening, fear of contracting COVID-19 is a big part of what is preventing patients from returning.

“We’ve known even pre-pandemic that people were hesitant to do cancer screening and in some ways this has really given them an out to say, ‘Well, I’m going to hold off on that colonoscopy,’ ” Amy Leader, MD, from Thomas Jefferson University’s Kimmel Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, said during the symposium.

Estimating the pandemic’s impact on cancer care

While the impact of the pandemic on cancer can only be estimated at the moment, the prospects are already daunting, said Richardson, speculating that the hard-won 26% drop in cancer mortality over the past two decades “may be put on hold or reversed” by COVID-19.

There could be as many as 10,000 excess deaths in the US from colorectal and breast cancer alone because of COVID-19 delays, predicted Norman E. Sharpless, director of the US National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

But even Sharpless acknowledges that his modeling gives a conservative estimate, “as it does not consider other cancer types, it does not account for the additional nonlethal morbidity from upstaging, and it assumes a moderate disruption in care that completely resolves after 6 months.”

With still no end to the pandemic in sight, the true scope of cancer screening and treatment disruptions will take a long time to assess, but several studies presented during the symposium revealed some early indications.

A national survey launched in mid-May, which involved 534 women either diagnosed with breast cancer or undergoing screening or diagnostic evaluation for it, found that delays in screening were reported by 31.7% of those with breast cancer, and 26.7% of those without. Additionally, 21% of those on active treatment for breast cancer reported treatment delays.

“It’s going to be really important to implement strategies to help patients return to care ... creating a culture and a feeling of safety among patients and communicating through the uncertainty that exists in the pandemic,” said study investigator Erica T. Warner, ScD MPH, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Screening for prostate cancer (via prostate-specific antigen testing) also declined, though not as dramatically as that for breast cancer, noted Mara Epstein, ScD, from The Meyers Primary Care Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. Her study at a large healthcare provider group compared rates of both screening and diagnostic mammographies, and also PSA testing, as well as breast and prostate biopsies in the first five months of 2020 vs the same months in 2019.

While a decrease from 2019 to 2020 was seen in all procedures over the entire study period, the greatest decline was seen in April for screening mammography (down 98%), and tomosynthesis (down 96%), as well as PSA testing (down 83%), she said.

More recent figures are hard to come by, but a recent weekly survey from the Primary Care Collaborative shows 46% of practices are offering preventive and chronic care management visits, but patients are not scheduling them, and 44% report that in-person visit volume is between 30%-50% below normal over the last 4 weeks.

Will COVID-19 exacerbate racial disparities in cancer?

Neither of the studies presented at the symposium analyzed cancer care disruptions by race, but there was concern among some panelists that cancer care disparities that existed before the pandemic will be magnified further.

“Over the next several months and into the next year there’s going to be some catch-up in screening and treatment, and one of my concerns is minority and underserved populations will not partake in that catch-up the way many middle-class Americans will,” said Otis Brawley, MD, from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

There is ample evidence that minority populations have been disproportionately hit by COVID-19, job losses, and lost health insurance, said the CDC’s Richardson, and all these factors could widen the cancer gap.

“It’s not a race thing, it’s a ‘what do you do thing,’ and an access to care thing, and what your socioeconomic status is,” Richardson said in an interview. “People who didn’t have sick leave before the pandemic still don’t have sick leave; if they didn’t have time to get their mammogram they still don’t have time.”

But she acknowledges that evidence is still lacking. Could some minority populations actually be less fearful of medical encounters because their work has already prevented them from sheltering in place? “It could go either way,” she said. “They might be less wary of venturing out into the clinic, but they also might reason that they’ve exposed themselves enough already at work and don’t want any additional exposure.”

In that regard, Richardson suggests population-specific messaging will be an important way of communicating with under-served populations to restart screening.

“We’re struggling at CDC with how to develop messages that resonate within different communities, because we’re missing the point of actually speaking to people within their culture and within the places that they live,” she said. “Just saying the same thing and putting a black face on it is not going to make a difference; you actually have to speak the language of the people you’re trying to reach — the same message in different packages.”

To that end, even before the pandemic, the CDC supported the development of Make It Your Own, a website that uses “evidence-based strategies” to assist healthcare organizations in customizing health information “by race, ethnicity, age, gender and location”, and target messages to “specific populations, cultural groups and languages”.

But Mass General’s Warner says she’s not sure she would argue for messages to be tailored by race, “at least not without evidence that values and priorities regarding returning to care differ between racial/ethnic groups.”

“Tailoring in the absence of data requires assumptions that may or may not be correct and ignores within-group heterogeneity,” Warner told Medscape Medical News. “However, I do believe that messaging about return to cancer screening and care should be multifaceted and use diverse imagery. This recognizes that some messages will resonate more or less with individuals based on their own characteristics, of which race may be one.”

Warner does believe in the power of tailored messaging though. “Part of the onus for healthcare institutions and providers is to make some decisions about who it is really important to bring back in soonest,” she said.

“Those are the ones we want to prioritize, as opposed to those who we want to get back into care but we don’t need to get them in right now,” Warner emphasized. “As they are balancing all the needs of their family and their community and their other needs, messaging that adds additional stress, worry, anxiety and shame is not what we want to do. So really we need to distinguish between these populations, identify the priorities, hit the hard message to people who really need it now, and encourage others to come back in as they can.”

Building trust

All the panelists agreed that building trust with the public will be key to getting cancer care back on track.

“I don’t think anyone trusts the healthcare community right now, but we already had this baseline distrust of healthcare among many minority communities, and now with COVID-19, the African American community in particular is seeing people go into the hospital and never come back,” said Richardson.

For Warner, the onus really falls on healthcare institutions. “We have to be proactive and not leave the burden of deciding when and how to return to care up to patients,” she said.

“What we need to focus on as much as possible is to get people to realize it is safe to come see the doctor,” said Johns Hopkins oncologist Brawley. “We have to make it safe for them to come see us, and then we have to convince them it is safe to come see us.”

Venturing out to her mammography appointment in early June, Richardson said she felt safe. “Everything was just the way it was supposed to be, everyone was masked, everyone was washing their hands,” she said.

Yet, by mid-June she had contracted COVID-19. “I don’t know where I got it,” she said. “No matter how careful you are, understand that if you’re in a total red spot, as I am, you can just get it.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Diabetes plus weight loss equals increased risk of pancreatic cancer

A new study has linked recent-onset diabetes and subsequent weight loss to an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, indicating a distinct group of individuals to screen early for this deadly disease.

“The likelihood of a pancreatic cancer diagnosis was even further elevated among individuals with older age, healthy weight before weight loss, and unintentional weight loss,” wrote Chen Yuan, ScD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. The study was published in JAMA Oncology.

To determine whether an association exists between diabetes plus weight change and pancreatic cancer, the researchers analyzed decades of medical history data from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS). The study population from the NHS included 112,818 women with a mean age of 59 years; the population from the HPFS included 46,207 men with a mean age of 65 years. Since enrollment – the baseline was 1978 for the NHS and 1988 for the HPFS – participants have provided follow-up information via biennial questionnaires.

Recent diabetes onset, weight loss boost cancer risk

From those combined groups, 1,116 incident cases of pancreatic cancer (0.7%) were identified. Compared with patients with no diabetes, patients with recent-onset diabetes had triple the risk of pancreatic cancer (age-adjusted hazard ratio, 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.31-3.82) and patients with longstanding diabetes had more than double the risk (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.78-2.60). Patients with longer disease duration also had more than twice the risk of pancreatic cancer, with HRs of 2.25 for those with diabetes for 4-10 years (95% CI, 1.74-2.92) and 2.07 for more than 10 years (95% CI, 1.61-2.66).

Compared with patients who hadn’t lost any weight, patients who reported a 1- to 4-pound weight loss (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.03-1.52), a 5- to 8-pound weight loss (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.06-1.66), and a more than 8-pound weight loss (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.58-2.32) had higher risks of pancreatic cancer. Patients with recent-onset diabetes and a 1- to 8-pound weight loss (91 incident cases per 100,000 person-years; 95% CI, 55-151) or a weight loss of more than 8 pounds (164 incident cases per 100,000 person years; 95% CI, 114-238) had a much higher incidence of pancreatic cancer, compared with patients with neither (16 incident cases per 100,000 person-years; 95% CI, 14-17).

After stratified analyses of patients with both recent-onset diabetes and weight loss, rates of pancreatic cancer were also notably high in those 70 years or older (234 cases per 100,000 person years), those with a body mass index of less than 25 kg/m2 before weight loss (400 cases per 100,000 person years), and those with a low likelihood of intentional weight loss (334 cases per 100,000 person years).

“I like the study because it reminds us of the importance of not thinking everyone that presents with type 2 diabetes necessarily has garden-variety diabetes,” Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes and Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla., said in an interview. “I have always been concerned when a new-onset diabetic individual presents with no family history of diabetes or prediabetes, especially if they’re neither overweight nor obese. I have sometimes screened those individuals for pancreatic abnormalities.”

A call for screening

“This study highlights the consideration for further screening to those with weight loss at the time of diabetes diagnosis, which is very sensible given how unusual weight loss is as a presenting symptom at the time of diagnosis of typical type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Jellinger added. “The combination of weight loss and no family history of diabetes at the time of diagnosis should be an even stronger signal for pancreatic cancer screening and potential detection at a much earlier stage.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including some patients with pancreatic cancer not returning their questionnaires and the timing of the questionnaires meaning that patients could’ve developed diabetes after returning it. In addition, they recognized that the participants were “predominantly White health professionals” and recommended a study of “additional patient populations” in the future.

The authors noted numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants and personal fees from various initiatives, organizations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Yuan C et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2948.

A new study has linked recent-onset diabetes and subsequent weight loss to an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, indicating a distinct group of individuals to screen early for this deadly disease.

“The likelihood of a pancreatic cancer diagnosis was even further elevated among individuals with older age, healthy weight before weight loss, and unintentional weight loss,” wrote Chen Yuan, ScD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. The study was published in JAMA Oncology.

To determine whether an association exists between diabetes plus weight change and pancreatic cancer, the researchers analyzed decades of medical history data from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS). The study population from the NHS included 112,818 women with a mean age of 59 years; the population from the HPFS included 46,207 men with a mean age of 65 years. Since enrollment – the baseline was 1978 for the NHS and 1988 for the HPFS – participants have provided follow-up information via biennial questionnaires.

Recent diabetes onset, weight loss boost cancer risk

From those combined groups, 1,116 incident cases of pancreatic cancer (0.7%) were identified. Compared with patients with no diabetes, patients with recent-onset diabetes had triple the risk of pancreatic cancer (age-adjusted hazard ratio, 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.31-3.82) and patients with longstanding diabetes had more than double the risk (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.78-2.60). Patients with longer disease duration also had more than twice the risk of pancreatic cancer, with HRs of 2.25 for those with diabetes for 4-10 years (95% CI, 1.74-2.92) and 2.07 for more than 10 years (95% CI, 1.61-2.66).

Compared with patients who hadn’t lost any weight, patients who reported a 1- to 4-pound weight loss (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.03-1.52), a 5- to 8-pound weight loss (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.06-1.66), and a more than 8-pound weight loss (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.58-2.32) had higher risks of pancreatic cancer. Patients with recent-onset diabetes and a 1- to 8-pound weight loss (91 incident cases per 100,000 person-years; 95% CI, 55-151) or a weight loss of more than 8 pounds (164 incident cases per 100,000 person years; 95% CI, 114-238) had a much higher incidence of pancreatic cancer, compared with patients with neither (16 incident cases per 100,000 person-years; 95% CI, 14-17).

After stratified analyses of patients with both recent-onset diabetes and weight loss, rates of pancreatic cancer were also notably high in those 70 years or older (234 cases per 100,000 person years), those with a body mass index of less than 25 kg/m2 before weight loss (400 cases per 100,000 person years), and those with a low likelihood of intentional weight loss (334 cases per 100,000 person years).

“I like the study because it reminds us of the importance of not thinking everyone that presents with type 2 diabetes necessarily has garden-variety diabetes,” Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes and Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla., said in an interview. “I have always been concerned when a new-onset diabetic individual presents with no family history of diabetes or prediabetes, especially if they’re neither overweight nor obese. I have sometimes screened those individuals for pancreatic abnormalities.”

A call for screening

“This study highlights the consideration for further screening to those with weight loss at the time of diabetes diagnosis, which is very sensible given how unusual weight loss is as a presenting symptom at the time of diagnosis of typical type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Jellinger added. “The combination of weight loss and no family history of diabetes at the time of diagnosis should be an even stronger signal for pancreatic cancer screening and potential detection at a much earlier stage.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including some patients with pancreatic cancer not returning their questionnaires and the timing of the questionnaires meaning that patients could’ve developed diabetes after returning it. In addition, they recognized that the participants were “predominantly White health professionals” and recommended a study of “additional patient populations” in the future.

The authors noted numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants and personal fees from various initiatives, organizations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Yuan C et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2948.

A new study has linked recent-onset diabetes and subsequent weight loss to an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, indicating a distinct group of individuals to screen early for this deadly disease.

“The likelihood of a pancreatic cancer diagnosis was even further elevated among individuals with older age, healthy weight before weight loss, and unintentional weight loss,” wrote Chen Yuan, ScD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. The study was published in JAMA Oncology.

To determine whether an association exists between diabetes plus weight change and pancreatic cancer, the researchers analyzed decades of medical history data from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS). The study population from the NHS included 112,818 women with a mean age of 59 years; the population from the HPFS included 46,207 men with a mean age of 65 years. Since enrollment – the baseline was 1978 for the NHS and 1988 for the HPFS – participants have provided follow-up information via biennial questionnaires.

Recent diabetes onset, weight loss boost cancer risk

From those combined groups, 1,116 incident cases of pancreatic cancer (0.7%) were identified. Compared with patients with no diabetes, patients with recent-onset diabetes had triple the risk of pancreatic cancer (age-adjusted hazard ratio, 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.31-3.82) and patients with longstanding diabetes had more than double the risk (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.78-2.60). Patients with longer disease duration also had more than twice the risk of pancreatic cancer, with HRs of 2.25 for those with diabetes for 4-10 years (95% CI, 1.74-2.92) and 2.07 for more than 10 years (95% CI, 1.61-2.66).

Compared with patients who hadn’t lost any weight, patients who reported a 1- to 4-pound weight loss (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.03-1.52), a 5- to 8-pound weight loss (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.06-1.66), and a more than 8-pound weight loss (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.58-2.32) had higher risks of pancreatic cancer. Patients with recent-onset diabetes and a 1- to 8-pound weight loss (91 incident cases per 100,000 person-years; 95% CI, 55-151) or a weight loss of more than 8 pounds (164 incident cases per 100,000 person years; 95% CI, 114-238) had a much higher incidence of pancreatic cancer, compared with patients with neither (16 incident cases per 100,000 person-years; 95% CI, 14-17).

After stratified analyses of patients with both recent-onset diabetes and weight loss, rates of pancreatic cancer were also notably high in those 70 years or older (234 cases per 100,000 person years), those with a body mass index of less than 25 kg/m2 before weight loss (400 cases per 100,000 person years), and those with a low likelihood of intentional weight loss (334 cases per 100,000 person years).

“I like the study because it reminds us of the importance of not thinking everyone that presents with type 2 diabetes necessarily has garden-variety diabetes,” Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes and Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla., said in an interview. “I have always been concerned when a new-onset diabetic individual presents with no family history of diabetes or prediabetes, especially if they’re neither overweight nor obese. I have sometimes screened those individuals for pancreatic abnormalities.”

A call for screening

“This study highlights the consideration for further screening to those with weight loss at the time of diabetes diagnosis, which is very sensible given how unusual weight loss is as a presenting symptom at the time of diagnosis of typical type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Jellinger added. “The combination of weight loss and no family history of diabetes at the time of diagnosis should be an even stronger signal for pancreatic cancer screening and potential detection at a much earlier stage.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including some patients with pancreatic cancer not returning their questionnaires and the timing of the questionnaires meaning that patients could’ve developed diabetes after returning it. In addition, they recognized that the participants were “predominantly White health professionals” and recommended a study of “additional patient populations” in the future.

The authors noted numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants and personal fees from various initiatives, organizations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Yuan C et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2948.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Incidence, prognosis of second lung cancers support long-term surveillance

Second lung cancers occurring up to a decade after the first are on the rise, but their prognosis is similar – especially when detected early – which supports long-term surveillance in survivors, finds a large population-based study.

Although guidelines recommend continued annual low-dose CT scan surveillance extending beyond 4 years for this population based on expert consensus, long-term evidence of benefit is lacking.

Investigators led by John M. Varlotto, MD, a radiation oncologist at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, analyzed Surveillance, Epidemiology & End Results (SEER) data for more than 58,000 patients with first and sometimes second non–small cell lung cancers initially treated by surgical resection.

Study results reported in Lung Cancer showed that the age-adjusted incidence of second lung cancers occurring 4-10 years after the first lung cancer rose sharply during the 1985-2014 study period, driven by a large uptick in women patients.

Among all patients, second lung cancers had similar overall survival as first lung cancers, but poorer lung cancer–specific survival. However, among the subset of patients having early-stage resectable disease (tumors measuring less than 4 cm with negative nodes), both outcomes were statistically indistinguishable.

“Because our investigation noted that the overall survival of patients undergoing a second lung cancer operation was similar to those patients undergoing a first operation, and because there is a rising rate of second lung cancer in lung cancer survivors, we feel that continued surveillance beyond the 4-year interval as recommended by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery as well as the [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines would be beneficial to long-term survivors of early-stage lung cancer,” Dr. Varlotto and coinvestigators wrote.