User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Strategic Initiatives for Veterans with Lung Cancer (FULL)

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilitates care for > 7,700 veterans with newly diagnosed lung cancer each year.1 This includes comprehensive clinical evaluations and management that are facilitated through interdisciplinary networks of pulmonologists, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. Veterans with lung cancer have access to advanced medical technologies at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs), including the latest US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved targeted radiation delivery systems and novel immunotherapies, as well as precision oncology-driven clinical trials.2

Despite access to high-quality care, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among VHA enrollees as well as the US population.3 About 15 veterans die of lung cancer each day; most are diagnosed with advanced stage III or stage IV disease. To address this issue, VHA launched 3 new initiatives between 2016 and 2017 to improve outcomes for veterans impacted by lung cancer. The VA Partnership to increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS) is a clinical implementation project to increase access to early detection lung screening scans at 10 VAMCs. The Veterans Affairs Lung cancer surgery Or stereotactic Radiotherapy (VALOR) is a phase 3 randomized trial that investigates the role of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) as a potential alternative to surgery for veterans with operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance program (VA-ROQS) established national expert-derived benchmarks for the quality assurance of lung cancer therapy.

VA-PALS

The central mission of VA-PALS is to reduce lung cancer mortality among veterans at risk by increasing access to low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung screening scans.4,5 The program was developed as a public-private partnership to introduce structured lung cancer screening programs at 10 VAMCs to safely manage large cohorts of veterans undergoing annual screening scans. The VA-PALS project brings together pulmonologists, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and computer scientists who have experience developing open-source electronic health record systems for VHA networks. The project was launched in 2017 after an earlier clinical demonstration project identified substantial variability and challenges with efforts to implement new lung cancer screening programs in the VA.6

Each of the 10 VA-PALS-designated lung cancer screening programs (Atlanta, Georgia; Phoenix, Arizona; Indianapolis, Indiana; Chicago, Illinois; Nashville, Tennessee; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; St. Louis, Missouri; Denver, Colorado; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Cleveland, Ohio) assumes a major responsibility for ordering and evaluating the results of LDCT scans to ensure appropriate follow-up care of veterans with abnormal radiographic findings. Lung cancer screening programs are supported with a full-time navigator (nurse practitioner or physician assistant) who has received training from the VA-PALS project team with direct supervision by a local site director who is a pulmonologist, thoracic surgeon, or medical oncologist. Lung cancer screening programs establish a centralized approach that aims to reduce the burden on primary care providers for remembering to order annual baseline and repeat LDCT scans. The lung screening programs also manage radiographic findings that usually are benign to facilitate appropriate decisions to minimize the risk of unnecessary tests and procedures. Program implementation across VA-PALS sites includes a strong connection among participants through meetings, newsletters, and attendance at conferences to create a collaborative learning network, which has been shown to improve dissemination of best practices across the VHA.7,8

The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP), which pioneered the use of LDCT to reduce lung cancer mortality, is a leading partner for VA-PALS.9 This group has > 25 years of experience overcoming many of the obstacles and challenges that new lung cancer screening programs face.10 The I-ELCAP has successfully implemented new lung cancer screening programs at > 70 health care institutions worldwide. Their implementation processes provide continuous oversight for each center. As a result, the I-ELCAP team has developed a large and detailed lung cancer screening registry with > 75,000 patients enrolled globally, comprising a vast database of clinical data that has produced > 270 scientific publications focusing on improving the quality and safety of lung cancer screening.11,12

These reports have helped guide evidence-based recommendations for lung cancer screening in several countries and include standardized processes for patient counseling and smoking cessation, data acquisition and interpretation of LDCT images, and clinical management of abnormal findings to facilitate timely transition from diagnosis to treatment.13-15 The I-ELCAP management system detects 10% abnormal findings in the baseline screening study, which declines to 6% in subsequent years.12 The scientific findings from this approach have provided additional insights into technical CT scanning errors that can affect tumor nodule measurements.16 The vast amount of clinical data and expertise have helped explore genetic markers.17 The I-ELCAP has facilitated cost-effectiveness investigations to determine the value of screening, and their research portfolio includes investigations into the longer-term outcomes after primary treatment for patients with screen-detected lung cancers.18,19

I-ELCAP gifted its comprehensive clinical software management system that has been in use for the above contributions for use in the VHA through an open source agreement without licensing fees. The I-ELCAP software management system was rewritten in MUMPS, the software programming language that is used by the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The newly adapted VA-PALS/I-ELCAP system underwent modifications with VHA clinicians’ input, and was successfully installed at the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona, which has assumed a leading role for the VA-PALS project.

The VA-PALS/I-ELCAP clinical management system currently is under review by the VA Office of Information and Technology for broad distribution across the VHA through the VA Enterprise Cloud. Once in use across the VHA, the VA-PALS/I-ELCAP clinical management system will offer a longitudinal central database that can support numerous quality improvement and quality assurance initiatives, as well as innovative research projects. Research opportunities include: (1) large-scale examination of LDCT images with artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques; (2) epidemiologic investigations of environmental and genetic risk factors to better understand the high percentage of veterans diagnosed with lung cancer who were never smokers or had quit many years ago; and (3) multisite clinical trials that explore early detection blood screening tests that are under development.

The VA-PALS project is sponsored by the VHA Office of Rural Health as an enterprise-wide initiative that focuses on reaching rural veterans at risk. The project received additional support through the VA Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships with a $5.8 million grant from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. The VistA (Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture) Expertise Network is an additional key partner that helped adapt the VAPALS-ELCAP system for use on VHA networks.

VALOR Trial

The VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #2005 VALOR study is a randomized phase 3 clinical trial that evaluates optimal treatment for participants with operable early-stage NSCLC.20 The trial is sponsored by the CSP, which is responsible for and provides resources for the planning and conduct of large multicenter surgical and clinical trials in VHA.21 The CSP #2005 VALOR study plans to enroll veterans with stage I NSCLC who will be treated with a surgical lobectomy or SBRT according to random assignment. An alternative surgical approach with a segmentectomy is acceptable, although patients in poor health who are only qualify for a wedge resection will not be enrolled. The CSP will follow each participant for at least 5 years to evaluate which treatment, if either, results in a higher overall survival rate. Secondary outcome measures are quality of life, pulmonary function, health state utilities, patterns of failure, and causes of death.

Although the study design of the VALOR trial is relatively straightforward, recruitment of participants to similar randomized trials of surgery vs SBRT for operable stage I NSCLC outside the VA has historically been very difficult. Three earlier phase 3 trials in the Netherlands and US closed prematurely after collectively enrolling only 4% of planned participants. Although a pooled analysis of 2 of these trials demonstrated a statistically significant difference of 95% vs 79% survival in favor of SBRT at a median follow-up of 40 months, the analysis was underpowered because only 58 of the planned 1,380 participants were enrolled.22,23

The CSP #2005 VALOR study team was keenly aware of these past challenges and addressed many of the obstacles to enrollment by optimizing eligibility criteria and follow-up requirements. Enrollment sites were carefully selected after confirming equipoise between the 2 treatments, and study coordinators at each enrollment site were empowered to provide a leading role with recruitment. Multiple communication channels were established for constant contact to disseminate new best practices for recruitment as they were identified. Furthermore, a veteran-centric educational recruitment video, approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board, was designed to help study participants better understand the purpose of participating in a clinical trial (www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2005/CSP_2005.asp).

After the first year of recruitment, researchers identified individual clinician and patient preferences as the predominant difficulty with recruitment, which was not easy to address. The CSP #2005 VALOR study team opted to partner directly with the Qualitative Research Integrated within Trials (QuinteT) team in the United Kingdom to adopt its methods to successfully support randomized clinical trials with serious recruitment challenges.24,25 By working directly with the QuinteT director, the CSP #2005 VALOR team made a major revision to the informed consent forms by shifting focus away from disclosing potential harms of research to an informative document that emphasized the purpose of the study. The work with QuinteT also led to the creation of balanced narratives for study teams to use and for potential participants to read. These provide a more consistent message that describes why the study is important and why clinicians are no longer certain that surgery is the optimal treatment for all patients with operable stage I NSCLC.

The VALOR clinical trial, opened in 2017, remains open at only 9 VAMCs. As of early 2020, it has enrolled more participants than all previous phase 3 trials combined. Once completed, the results from CSP #2005 VALOR study will help clinicians and veterans with operable stage I NSCLC better understand the tradeoffs of surgery vs SBRT as an initial treatment option. Plans are under way to expand the scope of the trial and include investigations of pretreatment radiomic signatures and genetic markers from biopsy tissue and blood samples, to better predict when surgery or SBRT might be the best treatment option for an individual patient.

VA-ROQS

The VA-ROQS was created in 2016 to compare treatment of veterans with lung cancer in the VHA with quality standards recommended by nationally recognized experts in lung cancer care. Partnering with Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri and the American Society for Radiation Oncology, the VHA established a blue-ribbon panel of experts to review clinical trial data and medical literature to provide evidence-based quality metrics for lung cancer therapy. As a result, 26 metrics applicable to each patient’s case were developed, published, and used to assess lung cancer care in each VHA radiation oncology practice.26

By 2019, the resulting data led to a report on 773 lung cancer cases accumulated from all VHA radiation oncology practices. Performance data for each quality metric were compared for each practice within the VHA, which found that VHA practices met > 80% of all 1,278 metrics scored. Quality metrics included those documented within each patient health record and the specific radiation delivery parameters that reflected each health care provider’s treatment. After team investigators visited each center and recorded treatment data, VA-ROQS is now maturing to permit continuous, electronic monitoring of all lung cancer treatment delivered within VHA. As each veteran’s case is planned, the quality of the therapy is monitored, assessed, and reported to the treating physician. Each VHA radiation oncologist will receive up-to-date evaluation of each case compared with these evidence-based quality standards. The quality standards are reviewed by the blue-ribbon panel to keep the process current and valid.

Future of VHA Lung Cancer Care

As VHA continues to prioritize resources to improve and assure optimal outcomes for veterans with lung cancer, it is now looking to create a national network of Lung Cancer Centers of Excellence (LCCE) as described in the VA Budget Submission for fiscal year 2021. If Congress approves funding, LCCEs will soon be developed within the VA regional Veteran Integrated Service Network system to ensure that treatment decisions for veterans with lung cancer are based on all available molecular information, including data on pharmacogenomic profiles. Such a network would create more opportunities to leverage public–private partnerships similar to the VA-PALS project. Creation of LCCEs would help the VA leverage an even stronger learning network to support more research so that all veterans who are impacted by lung cancer have access to personalized care that optimizes safety, quality of life, and overall survival. The lessons learned, networks developed, and partnerships established through VA-PALS, VALOR, and VA-ROQS are instrumental toward achieving these goals.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-11-00434

2. Dawson GA, Cheuk AV, Lutz S, et al. The availability of advanced radiation oncology technology within the Veterans Health Administration radiation oncology centers. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 4):18S-22S.

3. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi:10.3322/caac.21551

4. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Lung cancer incidence and mortality with extended follow-up in the National Lung Screening Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

5. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT Screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-513. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

6. Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9022

7. Clancy C. Creating World-class care and service for our nation’s finest: how Veterans Health Administration Diffusion of Excellence Initiative Is innovating and transforming Veterans Affairs health care. Perm J. 2019;23:18.301. doi:10.7812/TPP/18.301

8. Elnahal SM, Clancy CM, Shulkin DJ. A framework for disseminating clinical best practices in the VA health system. JAMA. 2017;317(3):255-256. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.18764

9. Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354(9173):99-105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6

10. Mulshine JL, Henschke CI. Lung cancer screening: achieving more by intervening less. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1284-1285. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70418-8

11. Henschke CI, Li K, Yip R, Salvatore M, Yankelevitz DF. The importance of the regimen of screening in maximizing the benefit and minimizing the harms. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(8):153. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.04.06

12. Henschke CI, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Smith JP; International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators*. Definition of a positive test result in computed tomography screening for lung cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):246-252. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00004

13. Zeliadt SB, Heffner JL, Sayre G, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about smoking cessation in the context of lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1530-1537. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3558

14. Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, et al. Tumor volume measurement error using computed tomography imaging in a phase II clinical trial in lung cancer. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2016;3(3):035505. doi:10.1117/1.JMI.3.3.035505

15. Yip R, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Boffetta P, Smith JP; International Early Lung Cancer Investigators. The impact of the regimen of screening on lung cancer cure: a comparison of I-ELCAP and NLST. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(3):201-208. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000065

16. Armato SG 3rd, McLennan G, Bidaut L, et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): a completed reference database of lung nodules on CT scans. Med Phys. 2011;38(2):915-931. doi:10.1118/1.3528204

17. Gill RK, Vazquez MF, Kramer A, et al. The use of genetic markers to identify lung cancer in fine needle aspiration samples. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(22):7481-7487. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5242

18. Pyenson BS, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, Dec E. Offering lung cancer screening to high-risk medicare beneficiaries saves lives and is cost-effective: an actuarial analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(5):272-282.

19. Schwartz RM, Yip R, Olkin I, et al. Impact of surgery for stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer on patient quality of life. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14(1):37-44. doi:10.12788/jcso.0205

20. Moghanaki D, Chang JY. Is surgery still the optimal treatment for stage I non-small cell lung cancer? Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(2):183-189. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2016.04.05

21. Bakaeen FG, Reda DJ, Gelijns AC, et al. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program network of dedicated enrollment sites: implications for surgical trials [published correction appears in JAMA Surg. 2014 Sep;149(9):961]. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):507-513. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4150

22. Chang JY, Senan S, Paul MA, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2015 Sep;16(9):e427]. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):630-637. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70168-3

23. Samson P, Keogan K, Crabtree T, et al. Interpreting survival data from clinical trials of surgery versus stereotactic body radiation therapy in operable Stage I non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2017;103:6-10. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.005

24. Donovan JL, Rooshenas L, Jepson M, et al. Optimising recruitment and informed consent in randomised controlled trials: the development and implementation of the Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI). Trials. 2016;17(1):283. Published 2016 Jun 8. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1391-4

25. Rooshenas L, Scott LJ, Blazeby JM, et al. The QuinteT Recruitment Intervention supported five randomized trials to recruit to target: a mixed-methods evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;106:108-120. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.10.004

26. Hagan M, Kapoor R, Michalski J, et al. VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(3):639-647. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.064

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilitates care for > 7,700 veterans with newly diagnosed lung cancer each year.1 This includes comprehensive clinical evaluations and management that are facilitated through interdisciplinary networks of pulmonologists, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. Veterans with lung cancer have access to advanced medical technologies at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs), including the latest US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved targeted radiation delivery systems and novel immunotherapies, as well as precision oncology-driven clinical trials.2

Despite access to high-quality care, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among VHA enrollees as well as the US population.3 About 15 veterans die of lung cancer each day; most are diagnosed with advanced stage III or stage IV disease. To address this issue, VHA launched 3 new initiatives between 2016 and 2017 to improve outcomes for veterans impacted by lung cancer. The VA Partnership to increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS) is a clinical implementation project to increase access to early detection lung screening scans at 10 VAMCs. The Veterans Affairs Lung cancer surgery Or stereotactic Radiotherapy (VALOR) is a phase 3 randomized trial that investigates the role of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) as a potential alternative to surgery for veterans with operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance program (VA-ROQS) established national expert-derived benchmarks for the quality assurance of lung cancer therapy.

VA-PALS

The central mission of VA-PALS is to reduce lung cancer mortality among veterans at risk by increasing access to low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung screening scans.4,5 The program was developed as a public-private partnership to introduce structured lung cancer screening programs at 10 VAMCs to safely manage large cohorts of veterans undergoing annual screening scans. The VA-PALS project brings together pulmonologists, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and computer scientists who have experience developing open-source electronic health record systems for VHA networks. The project was launched in 2017 after an earlier clinical demonstration project identified substantial variability and challenges with efforts to implement new lung cancer screening programs in the VA.6

Each of the 10 VA-PALS-designated lung cancer screening programs (Atlanta, Georgia; Phoenix, Arizona; Indianapolis, Indiana; Chicago, Illinois; Nashville, Tennessee; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; St. Louis, Missouri; Denver, Colorado; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Cleveland, Ohio) assumes a major responsibility for ordering and evaluating the results of LDCT scans to ensure appropriate follow-up care of veterans with abnormal radiographic findings. Lung cancer screening programs are supported with a full-time navigator (nurse practitioner or physician assistant) who has received training from the VA-PALS project team with direct supervision by a local site director who is a pulmonologist, thoracic surgeon, or medical oncologist. Lung cancer screening programs establish a centralized approach that aims to reduce the burden on primary care providers for remembering to order annual baseline and repeat LDCT scans. The lung screening programs also manage radiographic findings that usually are benign to facilitate appropriate decisions to minimize the risk of unnecessary tests and procedures. Program implementation across VA-PALS sites includes a strong connection among participants through meetings, newsletters, and attendance at conferences to create a collaborative learning network, which has been shown to improve dissemination of best practices across the VHA.7,8

The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP), which pioneered the use of LDCT to reduce lung cancer mortality, is a leading partner for VA-PALS.9 This group has > 25 years of experience overcoming many of the obstacles and challenges that new lung cancer screening programs face.10 The I-ELCAP has successfully implemented new lung cancer screening programs at > 70 health care institutions worldwide. Their implementation processes provide continuous oversight for each center. As a result, the I-ELCAP team has developed a large and detailed lung cancer screening registry with > 75,000 patients enrolled globally, comprising a vast database of clinical data that has produced > 270 scientific publications focusing on improving the quality and safety of lung cancer screening.11,12

These reports have helped guide evidence-based recommendations for lung cancer screening in several countries and include standardized processes for patient counseling and smoking cessation, data acquisition and interpretation of LDCT images, and clinical management of abnormal findings to facilitate timely transition from diagnosis to treatment.13-15 The I-ELCAP management system detects 10% abnormal findings in the baseline screening study, which declines to 6% in subsequent years.12 The scientific findings from this approach have provided additional insights into technical CT scanning errors that can affect tumor nodule measurements.16 The vast amount of clinical data and expertise have helped explore genetic markers.17 The I-ELCAP has facilitated cost-effectiveness investigations to determine the value of screening, and their research portfolio includes investigations into the longer-term outcomes after primary treatment for patients with screen-detected lung cancers.18,19

I-ELCAP gifted its comprehensive clinical software management system that has been in use for the above contributions for use in the VHA through an open source agreement without licensing fees. The I-ELCAP software management system was rewritten in MUMPS, the software programming language that is used by the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The newly adapted VA-PALS/I-ELCAP system underwent modifications with VHA clinicians’ input, and was successfully installed at the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona, which has assumed a leading role for the VA-PALS project.

The VA-PALS/I-ELCAP clinical management system currently is under review by the VA Office of Information and Technology for broad distribution across the VHA through the VA Enterprise Cloud. Once in use across the VHA, the VA-PALS/I-ELCAP clinical management system will offer a longitudinal central database that can support numerous quality improvement and quality assurance initiatives, as well as innovative research projects. Research opportunities include: (1) large-scale examination of LDCT images with artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques; (2) epidemiologic investigations of environmental and genetic risk factors to better understand the high percentage of veterans diagnosed with lung cancer who were never smokers or had quit many years ago; and (3) multisite clinical trials that explore early detection blood screening tests that are under development.

The VA-PALS project is sponsored by the VHA Office of Rural Health as an enterprise-wide initiative that focuses on reaching rural veterans at risk. The project received additional support through the VA Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships with a $5.8 million grant from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. The VistA (Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture) Expertise Network is an additional key partner that helped adapt the VAPALS-ELCAP system for use on VHA networks.

VALOR Trial

The VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #2005 VALOR study is a randomized phase 3 clinical trial that evaluates optimal treatment for participants with operable early-stage NSCLC.20 The trial is sponsored by the CSP, which is responsible for and provides resources for the planning and conduct of large multicenter surgical and clinical trials in VHA.21 The CSP #2005 VALOR study plans to enroll veterans with stage I NSCLC who will be treated with a surgical lobectomy or SBRT according to random assignment. An alternative surgical approach with a segmentectomy is acceptable, although patients in poor health who are only qualify for a wedge resection will not be enrolled. The CSP will follow each participant for at least 5 years to evaluate which treatment, if either, results in a higher overall survival rate. Secondary outcome measures are quality of life, pulmonary function, health state utilities, patterns of failure, and causes of death.

Although the study design of the VALOR trial is relatively straightforward, recruitment of participants to similar randomized trials of surgery vs SBRT for operable stage I NSCLC outside the VA has historically been very difficult. Three earlier phase 3 trials in the Netherlands and US closed prematurely after collectively enrolling only 4% of planned participants. Although a pooled analysis of 2 of these trials demonstrated a statistically significant difference of 95% vs 79% survival in favor of SBRT at a median follow-up of 40 months, the analysis was underpowered because only 58 of the planned 1,380 participants were enrolled.22,23

The CSP #2005 VALOR study team was keenly aware of these past challenges and addressed many of the obstacles to enrollment by optimizing eligibility criteria and follow-up requirements. Enrollment sites were carefully selected after confirming equipoise between the 2 treatments, and study coordinators at each enrollment site were empowered to provide a leading role with recruitment. Multiple communication channels were established for constant contact to disseminate new best practices for recruitment as they were identified. Furthermore, a veteran-centric educational recruitment video, approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board, was designed to help study participants better understand the purpose of participating in a clinical trial (www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2005/CSP_2005.asp).

After the first year of recruitment, researchers identified individual clinician and patient preferences as the predominant difficulty with recruitment, which was not easy to address. The CSP #2005 VALOR study team opted to partner directly with the Qualitative Research Integrated within Trials (QuinteT) team in the United Kingdom to adopt its methods to successfully support randomized clinical trials with serious recruitment challenges.24,25 By working directly with the QuinteT director, the CSP #2005 VALOR team made a major revision to the informed consent forms by shifting focus away from disclosing potential harms of research to an informative document that emphasized the purpose of the study. The work with QuinteT also led to the creation of balanced narratives for study teams to use and for potential participants to read. These provide a more consistent message that describes why the study is important and why clinicians are no longer certain that surgery is the optimal treatment for all patients with operable stage I NSCLC.

The VALOR clinical trial, opened in 2017, remains open at only 9 VAMCs. As of early 2020, it has enrolled more participants than all previous phase 3 trials combined. Once completed, the results from CSP #2005 VALOR study will help clinicians and veterans with operable stage I NSCLC better understand the tradeoffs of surgery vs SBRT as an initial treatment option. Plans are under way to expand the scope of the trial and include investigations of pretreatment radiomic signatures and genetic markers from biopsy tissue and blood samples, to better predict when surgery or SBRT might be the best treatment option for an individual patient.

VA-ROQS

The VA-ROQS was created in 2016 to compare treatment of veterans with lung cancer in the VHA with quality standards recommended by nationally recognized experts in lung cancer care. Partnering with Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri and the American Society for Radiation Oncology, the VHA established a blue-ribbon panel of experts to review clinical trial data and medical literature to provide evidence-based quality metrics for lung cancer therapy. As a result, 26 metrics applicable to each patient’s case were developed, published, and used to assess lung cancer care in each VHA radiation oncology practice.26

By 2019, the resulting data led to a report on 773 lung cancer cases accumulated from all VHA radiation oncology practices. Performance data for each quality metric were compared for each practice within the VHA, which found that VHA practices met > 80% of all 1,278 metrics scored. Quality metrics included those documented within each patient health record and the specific radiation delivery parameters that reflected each health care provider’s treatment. After team investigators visited each center and recorded treatment data, VA-ROQS is now maturing to permit continuous, electronic monitoring of all lung cancer treatment delivered within VHA. As each veteran’s case is planned, the quality of the therapy is monitored, assessed, and reported to the treating physician. Each VHA radiation oncologist will receive up-to-date evaluation of each case compared with these evidence-based quality standards. The quality standards are reviewed by the blue-ribbon panel to keep the process current and valid.

Future of VHA Lung Cancer Care

As VHA continues to prioritize resources to improve and assure optimal outcomes for veterans with lung cancer, it is now looking to create a national network of Lung Cancer Centers of Excellence (LCCE) as described in the VA Budget Submission for fiscal year 2021. If Congress approves funding, LCCEs will soon be developed within the VA regional Veteran Integrated Service Network system to ensure that treatment decisions for veterans with lung cancer are based on all available molecular information, including data on pharmacogenomic profiles. Such a network would create more opportunities to leverage public–private partnerships similar to the VA-PALS project. Creation of LCCEs would help the VA leverage an even stronger learning network to support more research so that all veterans who are impacted by lung cancer have access to personalized care that optimizes safety, quality of life, and overall survival. The lessons learned, networks developed, and partnerships established through VA-PALS, VALOR, and VA-ROQS are instrumental toward achieving these goals.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilitates care for > 7,700 veterans with newly diagnosed lung cancer each year.1 This includes comprehensive clinical evaluations and management that are facilitated through interdisciplinary networks of pulmonologists, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. Veterans with lung cancer have access to advanced medical technologies at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs), including the latest US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved targeted radiation delivery systems and novel immunotherapies, as well as precision oncology-driven clinical trials.2

Despite access to high-quality care, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among VHA enrollees as well as the US population.3 About 15 veterans die of lung cancer each day; most are diagnosed with advanced stage III or stage IV disease. To address this issue, VHA launched 3 new initiatives between 2016 and 2017 to improve outcomes for veterans impacted by lung cancer. The VA Partnership to increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS) is a clinical implementation project to increase access to early detection lung screening scans at 10 VAMCs. The Veterans Affairs Lung cancer surgery Or stereotactic Radiotherapy (VALOR) is a phase 3 randomized trial that investigates the role of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) as a potential alternative to surgery for veterans with operable stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance program (VA-ROQS) established national expert-derived benchmarks for the quality assurance of lung cancer therapy.

VA-PALS

The central mission of VA-PALS is to reduce lung cancer mortality among veterans at risk by increasing access to low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung screening scans.4,5 The program was developed as a public-private partnership to introduce structured lung cancer screening programs at 10 VAMCs to safely manage large cohorts of veterans undergoing annual screening scans. The VA-PALS project brings together pulmonologists, radiologists, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and computer scientists who have experience developing open-source electronic health record systems for VHA networks. The project was launched in 2017 after an earlier clinical demonstration project identified substantial variability and challenges with efforts to implement new lung cancer screening programs in the VA.6

Each of the 10 VA-PALS-designated lung cancer screening programs (Atlanta, Georgia; Phoenix, Arizona; Indianapolis, Indiana; Chicago, Illinois; Nashville, Tennessee; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; St. Louis, Missouri; Denver, Colorado; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Cleveland, Ohio) assumes a major responsibility for ordering and evaluating the results of LDCT scans to ensure appropriate follow-up care of veterans with abnormal radiographic findings. Lung cancer screening programs are supported with a full-time navigator (nurse practitioner or physician assistant) who has received training from the VA-PALS project team with direct supervision by a local site director who is a pulmonologist, thoracic surgeon, or medical oncologist. Lung cancer screening programs establish a centralized approach that aims to reduce the burden on primary care providers for remembering to order annual baseline and repeat LDCT scans. The lung screening programs also manage radiographic findings that usually are benign to facilitate appropriate decisions to minimize the risk of unnecessary tests and procedures. Program implementation across VA-PALS sites includes a strong connection among participants through meetings, newsletters, and attendance at conferences to create a collaborative learning network, which has been shown to improve dissemination of best practices across the VHA.7,8

The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP), which pioneered the use of LDCT to reduce lung cancer mortality, is a leading partner for VA-PALS.9 This group has > 25 years of experience overcoming many of the obstacles and challenges that new lung cancer screening programs face.10 The I-ELCAP has successfully implemented new lung cancer screening programs at > 70 health care institutions worldwide. Their implementation processes provide continuous oversight for each center. As a result, the I-ELCAP team has developed a large and detailed lung cancer screening registry with > 75,000 patients enrolled globally, comprising a vast database of clinical data that has produced > 270 scientific publications focusing on improving the quality and safety of lung cancer screening.11,12

These reports have helped guide evidence-based recommendations for lung cancer screening in several countries and include standardized processes for patient counseling and smoking cessation, data acquisition and interpretation of LDCT images, and clinical management of abnormal findings to facilitate timely transition from diagnosis to treatment.13-15 The I-ELCAP management system detects 10% abnormal findings in the baseline screening study, which declines to 6% in subsequent years.12 The scientific findings from this approach have provided additional insights into technical CT scanning errors that can affect tumor nodule measurements.16 The vast amount of clinical data and expertise have helped explore genetic markers.17 The I-ELCAP has facilitated cost-effectiveness investigations to determine the value of screening, and their research portfolio includes investigations into the longer-term outcomes after primary treatment for patients with screen-detected lung cancers.18,19

I-ELCAP gifted its comprehensive clinical software management system that has been in use for the above contributions for use in the VHA through an open source agreement without licensing fees. The I-ELCAP software management system was rewritten in MUMPS, the software programming language that is used by the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The newly adapted VA-PALS/I-ELCAP system underwent modifications with VHA clinicians’ input, and was successfully installed at the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona, which has assumed a leading role for the VA-PALS project.

The VA-PALS/I-ELCAP clinical management system currently is under review by the VA Office of Information and Technology for broad distribution across the VHA through the VA Enterprise Cloud. Once in use across the VHA, the VA-PALS/I-ELCAP clinical management system will offer a longitudinal central database that can support numerous quality improvement and quality assurance initiatives, as well as innovative research projects. Research opportunities include: (1) large-scale examination of LDCT images with artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques; (2) epidemiologic investigations of environmental and genetic risk factors to better understand the high percentage of veterans diagnosed with lung cancer who were never smokers or had quit many years ago; and (3) multisite clinical trials that explore early detection blood screening tests that are under development.

The VA-PALS project is sponsored by the VHA Office of Rural Health as an enterprise-wide initiative that focuses on reaching rural veterans at risk. The project received additional support through the VA Secretary’s Center for Strategic Partnerships with a $5.8 million grant from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. The VistA (Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture) Expertise Network is an additional key partner that helped adapt the VAPALS-ELCAP system for use on VHA networks.

VALOR Trial

The VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #2005 VALOR study is a randomized phase 3 clinical trial that evaluates optimal treatment for participants with operable early-stage NSCLC.20 The trial is sponsored by the CSP, which is responsible for and provides resources for the planning and conduct of large multicenter surgical and clinical trials in VHA.21 The CSP #2005 VALOR study plans to enroll veterans with stage I NSCLC who will be treated with a surgical lobectomy or SBRT according to random assignment. An alternative surgical approach with a segmentectomy is acceptable, although patients in poor health who are only qualify for a wedge resection will not be enrolled. The CSP will follow each participant for at least 5 years to evaluate which treatment, if either, results in a higher overall survival rate. Secondary outcome measures are quality of life, pulmonary function, health state utilities, patterns of failure, and causes of death.

Although the study design of the VALOR trial is relatively straightforward, recruitment of participants to similar randomized trials of surgery vs SBRT for operable stage I NSCLC outside the VA has historically been very difficult. Three earlier phase 3 trials in the Netherlands and US closed prematurely after collectively enrolling only 4% of planned participants. Although a pooled analysis of 2 of these trials demonstrated a statistically significant difference of 95% vs 79% survival in favor of SBRT at a median follow-up of 40 months, the analysis was underpowered because only 58 of the planned 1,380 participants were enrolled.22,23

The CSP #2005 VALOR study team was keenly aware of these past challenges and addressed many of the obstacles to enrollment by optimizing eligibility criteria and follow-up requirements. Enrollment sites were carefully selected after confirming equipoise between the 2 treatments, and study coordinators at each enrollment site were empowered to provide a leading role with recruitment. Multiple communication channels were established for constant contact to disseminate new best practices for recruitment as they were identified. Furthermore, a veteran-centric educational recruitment video, approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board, was designed to help study participants better understand the purpose of participating in a clinical trial (www.vacsp.research.va.gov/CSP_2005/CSP_2005.asp).

After the first year of recruitment, researchers identified individual clinician and patient preferences as the predominant difficulty with recruitment, which was not easy to address. The CSP #2005 VALOR study team opted to partner directly with the Qualitative Research Integrated within Trials (QuinteT) team in the United Kingdom to adopt its methods to successfully support randomized clinical trials with serious recruitment challenges.24,25 By working directly with the QuinteT director, the CSP #2005 VALOR team made a major revision to the informed consent forms by shifting focus away from disclosing potential harms of research to an informative document that emphasized the purpose of the study. The work with QuinteT also led to the creation of balanced narratives for study teams to use and for potential participants to read. These provide a more consistent message that describes why the study is important and why clinicians are no longer certain that surgery is the optimal treatment for all patients with operable stage I NSCLC.

The VALOR clinical trial, opened in 2017, remains open at only 9 VAMCs. As of early 2020, it has enrolled more participants than all previous phase 3 trials combined. Once completed, the results from CSP #2005 VALOR study will help clinicians and veterans with operable stage I NSCLC better understand the tradeoffs of surgery vs SBRT as an initial treatment option. Plans are under way to expand the scope of the trial and include investigations of pretreatment radiomic signatures and genetic markers from biopsy tissue and blood samples, to better predict when surgery or SBRT might be the best treatment option for an individual patient.

VA-ROQS

The VA-ROQS was created in 2016 to compare treatment of veterans with lung cancer in the VHA with quality standards recommended by nationally recognized experts in lung cancer care. Partnering with Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri and the American Society for Radiation Oncology, the VHA established a blue-ribbon panel of experts to review clinical trial data and medical literature to provide evidence-based quality metrics for lung cancer therapy. As a result, 26 metrics applicable to each patient’s case were developed, published, and used to assess lung cancer care in each VHA radiation oncology practice.26

By 2019, the resulting data led to a report on 773 lung cancer cases accumulated from all VHA radiation oncology practices. Performance data for each quality metric were compared for each practice within the VHA, which found that VHA practices met > 80% of all 1,278 metrics scored. Quality metrics included those documented within each patient health record and the specific radiation delivery parameters that reflected each health care provider’s treatment. After team investigators visited each center and recorded treatment data, VA-ROQS is now maturing to permit continuous, electronic monitoring of all lung cancer treatment delivered within VHA. As each veteran’s case is planned, the quality of the therapy is monitored, assessed, and reported to the treating physician. Each VHA radiation oncologist will receive up-to-date evaluation of each case compared with these evidence-based quality standards. The quality standards are reviewed by the blue-ribbon panel to keep the process current and valid.

Future of VHA Lung Cancer Care

As VHA continues to prioritize resources to improve and assure optimal outcomes for veterans with lung cancer, it is now looking to create a national network of Lung Cancer Centers of Excellence (LCCE) as described in the VA Budget Submission for fiscal year 2021. If Congress approves funding, LCCEs will soon be developed within the VA regional Veteran Integrated Service Network system to ensure that treatment decisions for veterans with lung cancer are based on all available molecular information, including data on pharmacogenomic profiles. Such a network would create more opportunities to leverage public–private partnerships similar to the VA-PALS project. Creation of LCCEs would help the VA leverage an even stronger learning network to support more research so that all veterans who are impacted by lung cancer have access to personalized care that optimizes safety, quality of life, and overall survival. The lessons learned, networks developed, and partnerships established through VA-PALS, VALOR, and VA-ROQS are instrumental toward achieving these goals.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-11-00434

2. Dawson GA, Cheuk AV, Lutz S, et al. The availability of advanced radiation oncology technology within the Veterans Health Administration radiation oncology centers. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 4):18S-22S.

3. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi:10.3322/caac.21551

4. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Lung cancer incidence and mortality with extended follow-up in the National Lung Screening Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

5. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT Screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-513. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

6. Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9022

7. Clancy C. Creating World-class care and service for our nation’s finest: how Veterans Health Administration Diffusion of Excellence Initiative Is innovating and transforming Veterans Affairs health care. Perm J. 2019;23:18.301. doi:10.7812/TPP/18.301

8. Elnahal SM, Clancy CM, Shulkin DJ. A framework for disseminating clinical best practices in the VA health system. JAMA. 2017;317(3):255-256. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.18764

9. Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354(9173):99-105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6

10. Mulshine JL, Henschke CI. Lung cancer screening: achieving more by intervening less. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1284-1285. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70418-8

11. Henschke CI, Li K, Yip R, Salvatore M, Yankelevitz DF. The importance of the regimen of screening in maximizing the benefit and minimizing the harms. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(8):153. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.04.06

12. Henschke CI, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Smith JP; International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators*. Definition of a positive test result in computed tomography screening for lung cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):246-252. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00004

13. Zeliadt SB, Heffner JL, Sayre G, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about smoking cessation in the context of lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1530-1537. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3558

14. Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, et al. Tumor volume measurement error using computed tomography imaging in a phase II clinical trial in lung cancer. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2016;3(3):035505. doi:10.1117/1.JMI.3.3.035505

15. Yip R, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Boffetta P, Smith JP; International Early Lung Cancer Investigators. The impact of the regimen of screening on lung cancer cure: a comparison of I-ELCAP and NLST. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(3):201-208. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000065

16. Armato SG 3rd, McLennan G, Bidaut L, et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): a completed reference database of lung nodules on CT scans. Med Phys. 2011;38(2):915-931. doi:10.1118/1.3528204

17. Gill RK, Vazquez MF, Kramer A, et al. The use of genetic markers to identify lung cancer in fine needle aspiration samples. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(22):7481-7487. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5242

18. Pyenson BS, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, Dec E. Offering lung cancer screening to high-risk medicare beneficiaries saves lives and is cost-effective: an actuarial analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(5):272-282.

19. Schwartz RM, Yip R, Olkin I, et al. Impact of surgery for stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer on patient quality of life. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14(1):37-44. doi:10.12788/jcso.0205

20. Moghanaki D, Chang JY. Is surgery still the optimal treatment for stage I non-small cell lung cancer? Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(2):183-189. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2016.04.05

21. Bakaeen FG, Reda DJ, Gelijns AC, et al. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program network of dedicated enrollment sites: implications for surgical trials [published correction appears in JAMA Surg. 2014 Sep;149(9):961]. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):507-513. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4150

22. Chang JY, Senan S, Paul MA, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2015 Sep;16(9):e427]. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):630-637. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70168-3

23. Samson P, Keogan K, Crabtree T, et al. Interpreting survival data from clinical trials of surgery versus stereotactic body radiation therapy in operable Stage I non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2017;103:6-10. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.005

24. Donovan JL, Rooshenas L, Jepson M, et al. Optimising recruitment and informed consent in randomised controlled trials: the development and implementation of the Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI). Trials. 2016;17(1):283. Published 2016 Jun 8. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1391-4

25. Rooshenas L, Scott LJ, Blazeby JM, et al. The QuinteT Recruitment Intervention supported five randomized trials to recruit to target: a mixed-methods evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;106:108-120. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.10.004

26. Hagan M, Kapoor R, Michalski J, et al. VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(3):639-647. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.064

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-11-00434

2. Dawson GA, Cheuk AV, Lutz S, et al. The availability of advanced radiation oncology technology within the Veterans Health Administration radiation oncology centers. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 4):18S-22S.

3. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi:10.3322/caac.21551

4. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Lung cancer incidence and mortality with extended follow-up in the National Lung Screening Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

5. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT Screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-513. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

6. Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9022

7. Clancy C. Creating World-class care and service for our nation’s finest: how Veterans Health Administration Diffusion of Excellence Initiative Is innovating and transforming Veterans Affairs health care. Perm J. 2019;23:18.301. doi:10.7812/TPP/18.301

8. Elnahal SM, Clancy CM, Shulkin DJ. A framework for disseminating clinical best practices in the VA health system. JAMA. 2017;317(3):255-256. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.18764

9. Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354(9173):99-105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6

10. Mulshine JL, Henschke CI. Lung cancer screening: achieving more by intervening less. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1284-1285. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70418-8

11. Henschke CI, Li K, Yip R, Salvatore M, Yankelevitz DF. The importance of the regimen of screening in maximizing the benefit and minimizing the harms. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(8):153. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.04.06

12. Henschke CI, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Smith JP; International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators*. Definition of a positive test result in computed tomography screening for lung cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):246-252. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00004

13. Zeliadt SB, Heffner JL, Sayre G, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about smoking cessation in the context of lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1530-1537. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3558

14. Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, et al. Tumor volume measurement error using computed tomography imaging in a phase II clinical trial in lung cancer. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2016;3(3):035505. doi:10.1117/1.JMI.3.3.035505

15. Yip R, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Boffetta P, Smith JP; International Early Lung Cancer Investigators. The impact of the regimen of screening on lung cancer cure: a comparison of I-ELCAP and NLST. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(3):201-208. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000065

16. Armato SG 3rd, McLennan G, Bidaut L, et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): a completed reference database of lung nodules on CT scans. Med Phys. 2011;38(2):915-931. doi:10.1118/1.3528204

17. Gill RK, Vazquez MF, Kramer A, et al. The use of genetic markers to identify lung cancer in fine needle aspiration samples. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(22):7481-7487. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5242

18. Pyenson BS, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, Dec E. Offering lung cancer screening to high-risk medicare beneficiaries saves lives and is cost-effective: an actuarial analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(5):272-282.

19. Schwartz RM, Yip R, Olkin I, et al. Impact of surgery for stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer on patient quality of life. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14(1):37-44. doi:10.12788/jcso.0205

20. Moghanaki D, Chang JY. Is surgery still the optimal treatment for stage I non-small cell lung cancer? Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5(2):183-189. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2016.04.05

21. Bakaeen FG, Reda DJ, Gelijns AC, et al. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program network of dedicated enrollment sites: implications for surgical trials [published correction appears in JAMA Surg. 2014 Sep;149(9):961]. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):507-513. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4150

22. Chang JY, Senan S, Paul MA, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2015 Sep;16(9):e427]. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):630-637. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70168-3

23. Samson P, Keogan K, Crabtree T, et al. Interpreting survival data from clinical trials of surgery versus stereotactic body radiation therapy in operable Stage I non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2017;103:6-10. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.005

24. Donovan JL, Rooshenas L, Jepson M, et al. Optimising recruitment and informed consent in randomised controlled trials: the development and implementation of the Quintet Recruitment Intervention (QRI). Trials. 2016;17(1):283. Published 2016 Jun 8. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1391-4

25. Rooshenas L, Scott LJ, Blazeby JM, et al. The QuinteT Recruitment Intervention supported five randomized trials to recruit to target: a mixed-methods evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;106:108-120. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.10.004

26. Hagan M, Kapoor R, Michalski J, et al. VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(3):639-647. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.064

Leveraging Veterans Health Administration Clinical and Research Resources to Accelerate Discovery and Testing in Precision Oncology(FULL)

In May 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first 2 targeted treatments for prostate cancer, specifically, the poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors rucaparib and olaparib.1,2 For these medications to work, the tumor must have a homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), which is a form of DNA repair deficiency. The PARP pathway is important for DNA repair, and PARP inhibition leads to “synthetic lethality” in cancer cells that already are deficient in DNA repair mechanisms.3 Now, there is evidence that patients with prostate cancer who have HRD tumors and receive PARP inhibitors live longer when compared with those who receive standard of care options.4 These findings offer hope for patients with prostate cancer. They also demonstrate the process and potential benefits of precision oncology efforts; namely, targeted treatments for specific tumor types in cancer patients.

This article discusses the challenges and opportunities of precision oncology for US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA). First, the article will discuss working with relatively rare mutations. Second, the article will examine how the trials of olaparib and rucaparib illuminate the VHA contribution to research on new therapies for patients with cancer. Finally, the article will explore the ways in which VHA is becoming a major national contributor in drug discovery and approval of precision medications.

Precision Oncology

Despite advances in screening and treatment, an estimated 600,000 people in the US will die of cancer in 2020.5 Meaningful advances in cancer care depend on both laboratory and clinical research. This combination, known as translational research, takes discoveries in the laboratory and applies them to patients and vice versa. Successful translational research requires many components. These include talented scientists to form hypotheses and perform the work; money for supplies and equipment; platforms for timely dissemination of knowledge; well-trained clinicians to treat patients and lead research teams; and patients to participate in clinical trials. In precision oncology, the ability to find patients for the trials can be daunting, particularly in cases where the frequency of the mutation of interest is low.

During the 20th century, with few exceptions, physicians caring for patients with cancer had blunt instruments at their disposal. Surgery and radiation could lead to survival if the cancer was caught early enough. Systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy, rarely cured but could prolong life in some patients. However, chemotherapy is imprecise and targets any cell growing rapidly, including blood, hair, and gastrointestinal tract cells, which often leads to adverse effects. Sometimes complications from chemotherapy may shorten a person’s life, and certainly the quality of life during and after these treatments could be diminished. The improvements in cancer care occurred more rapidly once scientists had the tools to learn about individual tumors.

In the summer of 2000, researchers announced that the human genome had been sequenced.6 The genome (ie, DNA) consists of introns and exons that form a map for human development. Exons can be converted to proteins that carry out specific actions, such as helping in cell growth, cell death, or DNA repair. Solving the human genome itself did not lead directly to cures, but it did represent a huge advance in medical research. As time passed, sequencing genomes became more affordable, and sequencing just the exome alone was even cheaper.7 Treatments for cancer began to expand with the help of these tools, but questions as to the true benefit of targeted therapy also grew.8

Physicians and scientists have amassed more information about cancer cells and have applied this knowledge to active drug development. In 2001, the FDA approved the first targeted therapy, imatinib, for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). This rapidly improved patient survival through targeting the mutated protein that leads to CML, rather than just aiming for rapidly dividing cells.9 Those mutations for which there is a drug to target, such as the BCR-ABL translocation in CML, are called actionable mutations.

Precision Oncology Program for Prostate Cancer

In 2016, the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) established the Precision Oncology Program for Prostate Cancer (POPCaP) Centers of Excellence (COE). This partnership was formed to accelerate treatment and cure for veterans with prostate cancer. The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in California and VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Washington led this effort, and their principal investigators continue to co-lead POPCaP. Since its inception, 9 additional funded POPCaP COEs have joined, each with a mandate to sequence the tumors of men with metastatic prostate cancer.

The more that is learned about a tumor, the more likely it is that researchers can find mutations that are that tumor’s Achilles heel and defeat it. In fact, many drugs that can target mutations are already available. For example, BRCA2 is an actionable mutation that can be exploited by knocking out another key DNA repair mechanism in the cell, PARP. Today, the effort of sequencing has led to a rich database of mutations present in men with metastatic prostate cancer.

Although there are many targeted therapies, most have not been studied formally in prostate cancer. Occasionally, clinicians treating patients will use these drugs in an unapproved way, hoping that there will be anticancer activity. It is difficult to estimate the likelihood of success with a drug in this situation, and the safety profile may not be well described in that setting. Treatment decisions for incurable cancers must be made knowing the risks and benefits. This helps in shared decision making between the clinician and patient and informs choices concerning which laboratory tests to order and how often to see the patient. However, treatment decisions are sometimes made with the hope of activity when a cancer is known to be incurable. Very little data, which are critical to determine whether this helps or hurts patients, support this approach.

Some data suggest that sequencing and giving a drug for an actionable mutation may lead to better outcomes for patients. Sequencing of pancreatic tumors by Pishvaian and colleagues revealed that 282 of 1,082 (26%) samples harbored actionable mutations.10 Those patients who received a drug that targeted their actionable mutation (n = 46; 24%) lived longer when compared with those who had an actionable mutation but did not receive a drug that targeted it (hazard ratio [HR] 0.42 [95% CI, 0.26-0.68; P = .0004]). Additionally, those who received therapy for an actionable mutation lived longer when compared with those who did not have an actionable mutation (HR 0.34 [95% CI, 0.22-0.53; P < .001]). While this finding is intriguing, it does not mean that treating actionable mutations outside of a clinical trial should be done. To this end, VA established Prostate cancer Analysis for Therapy CHoice (PATCH) as a clinical trials network within POPCaP.

Prostate Cancer Analysis

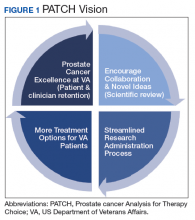

The overall PATCH vision is designed for clinical care and research work to together toward improved care for those with prostate cancer (Figure 1). The resources necessary for successful translational research are substantial, and PATCH aims to streamline those resources. PATCH will support innovative, precision-based clinical research at the POPCaP COEs through its 5 arms.

Arm 1. Dedicated personnel ensure veteran access to trials in PATCH by giving patients and providers accurate information about available trial options; aiding veterans in traveling from home VA to a POPCaP COE for participation on a study; and maintaining the Committee for Veteran Participation in PATCH, where veterans will be represented and asked to provide input into the PATCH process.

Arm 2. Coordinators at the coordinating COE in Portland, Orgeon, train investigators and study staff at the local POPCaP COEs to ensure research can be performed in a safe and responsible way.

Arm 3. Personnel experienced in conducting clinical trials liaise with investigators at VA Central Institutional Review Board, monitor trials, build databases for appropriate and efficient data collection, and manage high-risk studies conducted under an Investigational New Drug application. This group works closely with biostatisticians to choose appropriate trial designs, estimate numbers of patients needed, and interpret data once they are collected.

Arm 4. Protocol development and data dissemination is coordinated by a group to assist investigators in drafting protocols and reviewing abstracts and manuscripts.

Arm 5. A core group manages contracts and budgets, as well as relationships between VA and industry, where funding and drugs may be obtained.

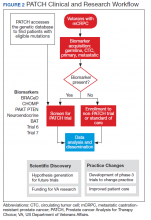

Perhaps most importantly, PATCH leverages the genetic data collected by POPCaP COEs to find patients for clinical trials. For example, the trials that examined olaparib and rucaparib assumed that the prevalence of HRD was about 25% in men with advanced prostate cancer.11 As these trials began enrollment, however, researchers discovered that the prevalence was < 20%. In fact, the study of olaparib screened 4,425 patients at 206 sites in 20 countries to identify 778 (18% of screened) patients with HRD.4 With widespread sequencing within VA, it could be possible to identify a substantial number of patients who are already known to have the mutation of interest (Figure 2).

Clinical Trials

There are currently 2 clinical trials in PATCH; 4 additional trials await funding decisions, and more trials are in the concept stage. BRACeD (NCT04038502) is a phase 2 trial examining platinum and taxane chemotherapy in tumors with HRD (specifically, BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2). About 15% to 20% of men with advanced prostate cancer will have a DNA repair defect in the tumor that could make them eligible for this study. The primary endpoint is progression-free survival.

A second study, CHOMP (NCT04104893), is a phase 2 trial examining the efficacy of immunotherapy (PD-1 inhibition) in tumors having mismatch repair deficiency or CDK12-/-. Each of those is found in about 7% of men with metastatic prostate cancer, and full accrual of a trial with rare mutations could take 5 to 10 years without a systematic approach of sequencing and identifying potential participants. The primary endpoint is a composite of radiographic response by iRECIST (immune response evaluation criteria in solid tumors), progression-free survival at 6 months and prostate specific antigen reduction by ≥ 50% in ≤ 12 weeks. With 11 POPCaP COEs sequencing the tumors of every man with metastatic prostate cancer, identifying men with the appropriate mutation is possible. PATCH will aid the sites in recruitment through outreach and coordination of travel.

Industry Partnerships

PATCH depends upon pharmaceutical industry partners, as clinical trials of even 40 patients can require significant funding and trial resources to operate. Furthermore, many drugs of interest are not available outside of a clinical trial, and partnerships enable VA researchers to access these medications. PATCH also benefits greatly from foundation partners, such as the PCF, which has made POPCaP possible and will continue to connect talented researchers with VA resources. Finally, access to other publicly available research funds, such as those from VA Office of Research and Development, National Institutes of Health, and US Department of Defense (DoD) Congressionally Directed Research Program are needed for trials.

Funding for these trials remains limited despite public health and broader interests in addressing important questions. Accelerated accrual through PATCH may be an attractive partnership opportunity for companies, foundations and government funding agencies to support the PATCH efforts.

Both POPCaP and PATCH highlight the potential promise of precision oncology within the nation’s largest integrated health care system. The VHA patient population enables prostate cancer researchers to serve an important early target. It also provides a foundational platform for a broader set of activities. These include a tailored approach to identifying tumor profiles and other patient characteristics that may help to elevate standard of care for other common cancers including ones affecting the lungs and/or head and neck.

To this end, VA has been working with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and DoD to establish a national infrastructure for precision oncology across multiple cancer types.12 In addition to clinical capabilities and the ability to run clinical trials that can accrue sufficient patients to answer key questions, we have developed capabilities for data collection and sharing, and analytical tools to support a learning health care system approach as a core element to precision oncology.

Besides having a research-specific context, such informatics and information technology systems enable clinicians to obtain and apply decision-making data rapidly for a specific patient and cancer type. These systems take particular advantage of the extensive electronic health record that underlies the VHA system, integrating real-world evidence into rigorous trials for precision oncology and other diseases. This is important for facilitating prerequisite activities for quality assessments for incorporation into databases (with appropriate permissions) to enhance treatment options. These activities are a key focus of the APOLLO initiative.13 While a more in-depth discussion of the importance of informatics is beyond the scope of this article, the field represents an important investment that is needed to achieve the goals of precision oncology.

In addition to informatics and data handling capabilities, VA has a longstanding tradition of designing and coordinating multisite clinical trials. This dates to the time of World War II when returning veterans had a high prevalence of tuberculosis. Since then, VA has contributed extensively to landmark findings in cardiovascular disease and surgery, mental health, infectious disease, and cancer. It was a VA study that helped establish colonoscopy as a standard for colorectal cancer screening by detecting colonic neoplasms in asymptomatic patients.14

From such investigations, the VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) has developed many strategies to conduct multisite clinical trials. But, CSP also has organized its sites methodically for operational efficiency and the ability to maintain institutional knowledge that crosses different types of studies and diseases. Using its Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) model, VA partnered with NCI to more effectively address administrative and regulatory requirements for initiating trials and recruiting veterans into cancer clinical trials.15 This partnership—the NCI And VA Interagency Group to Accelerate Trials Enrollment (NAVIGATE)—supports 12 sites with a central CSP Coordinating Center (CSPCC).

CSPCC provides support, shares best practices and provides organizational commitment at the senior levels of both agencies to overcome potential barriers. The goals and strategies are described by Schiller and colleagues.16 While still in its early stage as a cancer research network, NAVIGATE may be integrated with POPCaP and other parts of VA clinical research enterprise. This would allow us to specialize in advancing oncology care and to leverage capabilities more specifically to precision oncology. With an emphasis on recruitment, NAVIGATE has established capabilities with VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure to quickly identify patients who may be eligible for particular clinical trials. We envision further refining these capabilities for precision oncology trials that incorporate genetic and other information for individual patients. VA also hopes to inform trial sponsors about design considerations. This is important since networked investigators will have direct insights into patient-level factors, which may help with more effectively identifying and enrolling them into trials for their particular cancers.

Conclusions

VA may have an opportunity to reach out to veterans who may not have immediate access to facilities running clinical trials. As it develops capabilities to bring the trial to the veteran, VA could have more virtual and/or centralized recruitment strategies. This would broaden opportunities for considering novel approaches that may not rely on a more traditional facility-based recruitment approach.