User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Does vitamin D benefit only those who are deficient?

, suggests a new large-scale analysis.

Data on more than 380,000 participants gathered from 35 studies showed that, overall, there is no significant relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations, a clinical indicator of vitamin D status, and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or all-cause death, in a Mendelian randomization analysis.

However, Stephen Burgess, PhD, and colleagues showed that, in vitamin D–deficient individuals, each 10 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentrations reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 31%.

The research, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, also suggests there was a nonsignificant link between 25(OH)D concentrations and stroke and CHD, but again, only in vitamin D deficient individuals.

In an accompanying editorial, Guillaume Butler-Laporte, MD, and J. Brent Richards, MD, praise the researchers on their study methodology.

They add that the results “could have important public health and clinical consequences” and will “allow clinicians to better weigh the potential benefits of supplementation against its risk,” such as financial cost, “for better patient care – particularly among those with frank vitamin D deficiency.”

They continue: “Given that vitamin D deficiency is relatively common and vitamin D supplementation is safe, the rationale exists to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation in those with deficiency in large-scale randomized controlled trials.”

However, Dr. Butler-Laporte and Dr. Richards, of the Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, also note the study has several limitations, including the fact that the lifetime exposure to lower vitamin D levels captured by Mendelian randomization may result in larger effect sizes than in conventional trials.

Prior RCTS underpowered to detect effects of vitamin D supplements

“There are several potential mechanisms by which vitamin D could be protective for cardiovascular mortality, including mechanisms linking low vitamin D status with hyperparathyroidism and low serum calcium and phosphate,” write Dr. Burgess of the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge (England), and coauthors.

They also highlight that vitamin D is “further implicated in endothelial cell function” and affects the transcription of genes linked to cell division and apoptosis, providing “potential mechanisms implicating vitamin D for cancer.”

The researchers note that, while epidemiologic studies have “consistently” found a link between 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and other chronic diseases, several large trials of vitamin D supplementation have reported “null results.”

They argue, however, that many of these trials have recruited individuals “irrespective of baseline 25(OH)D concentration” and have been underpowered to detect the effects of supplementation.

To overcome these limitations, the team gathered data from the UK Biobank, the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cardiovascular Disease (EPIC-CVD) study, 31 studies from the Vitamin D Studies Collaboration (VitDSC), and two Copenhagen population-based studies.

They first performed an observational study that included 384,721 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who had a valid 25(OH)D measurement and no previously known cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Researchers also included 67,992 participants from the VitDSC studies who did not have previously known cardiovascular disease. They analyzed 25(OH)D concentrations, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and major incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality using individual participant data.

The results showed that, at low 25(OH)D concentrations, there was an inverse association between 25(OH)D and incident CHD, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Next, the team conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis on 333,002 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who were of European ancestry and had both a valid 25(OH)D measurement and genetic data that passed quality-control steps.

Information on 31,362 participants in the Copenhagen population-based studies was also included, giving a total of 386,406 individuals, of whom 33,546 had CHD, 18,166 had a stroke, and 27,885 died.

The mean age of participants ranged from 54.8 to 57.5 years, and between 53.4% and 55.4% were female.

Up to 7% of study participants were vitamin D deficient

The 25(OH)D analysis indicated that 3.9% of UK Biobank and 3.7% of Copenhagen study participants were deficient, compared with 6.9% in EPIC-CVD.

Across the full range of 25(OH)D concentrations, there was no significant association between genetically predicted 25(OH)D levels and CHD, stroke, or all-cause mortality.

However, restricting the analysis to individuals deemed vitamin D deficient (25[OH]D concentration < 25 nmol/L) revealed there was “strong evidence” for an inverse association with all-cause mortality, at an odds ratio per 10 nmol/L increase in genetically predicted 25(OH)D concentration of 0.69 (P < .0001), the team notes.

There were also nonsignificant associations between being in the deficient stratum and CHD, at an odds ratio of 0.89 (P = .14), and stroke, at an odds ratio of 0.85 (P = .09).

Further analysis suggests the association between 25(OH)D concentrations and all-cause mortality has a “clear threshold shape,” the researchers say, with evidence of an inverse association at concentrations below 40 nmol/L and null associations above that threshold.

They acknowledge, however, that their study has several potential limitations, including the assumption in their Mendelian randomization that the “only causal pathway from the genetic variants to the outcome is via 25(OH)D concentrations.”

Moreover, the genetic variants may affect 25(OH)D concentrations in a different way from “dietary supplementation or other clinical interventions.”

They also concede that their study was limited to middle-aged participants of European ancestries, which means the findings “might not be applicable to other populations.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Health Data Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and International Agency for Research on Cancer. Dr. Burgess has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggests a new large-scale analysis.

Data on more than 380,000 participants gathered from 35 studies showed that, overall, there is no significant relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations, a clinical indicator of vitamin D status, and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or all-cause death, in a Mendelian randomization analysis.

However, Stephen Burgess, PhD, and colleagues showed that, in vitamin D–deficient individuals, each 10 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentrations reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 31%.

The research, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, also suggests there was a nonsignificant link between 25(OH)D concentrations and stroke and CHD, but again, only in vitamin D deficient individuals.

In an accompanying editorial, Guillaume Butler-Laporte, MD, and J. Brent Richards, MD, praise the researchers on their study methodology.

They add that the results “could have important public health and clinical consequences” and will “allow clinicians to better weigh the potential benefits of supplementation against its risk,” such as financial cost, “for better patient care – particularly among those with frank vitamin D deficiency.”

They continue: “Given that vitamin D deficiency is relatively common and vitamin D supplementation is safe, the rationale exists to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation in those with deficiency in large-scale randomized controlled trials.”

However, Dr. Butler-Laporte and Dr. Richards, of the Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, also note the study has several limitations, including the fact that the lifetime exposure to lower vitamin D levels captured by Mendelian randomization may result in larger effect sizes than in conventional trials.

Prior RCTS underpowered to detect effects of vitamin D supplements

“There are several potential mechanisms by which vitamin D could be protective for cardiovascular mortality, including mechanisms linking low vitamin D status with hyperparathyroidism and low serum calcium and phosphate,” write Dr. Burgess of the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge (England), and coauthors.

They also highlight that vitamin D is “further implicated in endothelial cell function” and affects the transcription of genes linked to cell division and apoptosis, providing “potential mechanisms implicating vitamin D for cancer.”

The researchers note that, while epidemiologic studies have “consistently” found a link between 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and other chronic diseases, several large trials of vitamin D supplementation have reported “null results.”

They argue, however, that many of these trials have recruited individuals “irrespective of baseline 25(OH)D concentration” and have been underpowered to detect the effects of supplementation.

To overcome these limitations, the team gathered data from the UK Biobank, the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cardiovascular Disease (EPIC-CVD) study, 31 studies from the Vitamin D Studies Collaboration (VitDSC), and two Copenhagen population-based studies.

They first performed an observational study that included 384,721 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who had a valid 25(OH)D measurement and no previously known cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Researchers also included 67,992 participants from the VitDSC studies who did not have previously known cardiovascular disease. They analyzed 25(OH)D concentrations, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and major incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality using individual participant data.

The results showed that, at low 25(OH)D concentrations, there was an inverse association between 25(OH)D and incident CHD, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Next, the team conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis on 333,002 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who were of European ancestry and had both a valid 25(OH)D measurement and genetic data that passed quality-control steps.

Information on 31,362 participants in the Copenhagen population-based studies was also included, giving a total of 386,406 individuals, of whom 33,546 had CHD, 18,166 had a stroke, and 27,885 died.

The mean age of participants ranged from 54.8 to 57.5 years, and between 53.4% and 55.4% were female.

Up to 7% of study participants were vitamin D deficient

The 25(OH)D analysis indicated that 3.9% of UK Biobank and 3.7% of Copenhagen study participants were deficient, compared with 6.9% in EPIC-CVD.

Across the full range of 25(OH)D concentrations, there was no significant association between genetically predicted 25(OH)D levels and CHD, stroke, or all-cause mortality.

However, restricting the analysis to individuals deemed vitamin D deficient (25[OH]D concentration < 25 nmol/L) revealed there was “strong evidence” for an inverse association with all-cause mortality, at an odds ratio per 10 nmol/L increase in genetically predicted 25(OH)D concentration of 0.69 (P < .0001), the team notes.

There were also nonsignificant associations between being in the deficient stratum and CHD, at an odds ratio of 0.89 (P = .14), and stroke, at an odds ratio of 0.85 (P = .09).

Further analysis suggests the association between 25(OH)D concentrations and all-cause mortality has a “clear threshold shape,” the researchers say, with evidence of an inverse association at concentrations below 40 nmol/L and null associations above that threshold.

They acknowledge, however, that their study has several potential limitations, including the assumption in their Mendelian randomization that the “only causal pathway from the genetic variants to the outcome is via 25(OH)D concentrations.”

Moreover, the genetic variants may affect 25(OH)D concentrations in a different way from “dietary supplementation or other clinical interventions.”

They also concede that their study was limited to middle-aged participants of European ancestries, which means the findings “might not be applicable to other populations.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Health Data Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and International Agency for Research on Cancer. Dr. Burgess has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggests a new large-scale analysis.

Data on more than 380,000 participants gathered from 35 studies showed that, overall, there is no significant relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations, a clinical indicator of vitamin D status, and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or all-cause death, in a Mendelian randomization analysis.

However, Stephen Burgess, PhD, and colleagues showed that, in vitamin D–deficient individuals, each 10 nmol/L increase in 25(OH)D concentrations reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 31%.

The research, published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, also suggests there was a nonsignificant link between 25(OH)D concentrations and stroke and CHD, but again, only in vitamin D deficient individuals.

In an accompanying editorial, Guillaume Butler-Laporte, MD, and J. Brent Richards, MD, praise the researchers on their study methodology.

They add that the results “could have important public health and clinical consequences” and will “allow clinicians to better weigh the potential benefits of supplementation against its risk,” such as financial cost, “for better patient care – particularly among those with frank vitamin D deficiency.”

They continue: “Given that vitamin D deficiency is relatively common and vitamin D supplementation is safe, the rationale exists to test the effect of vitamin D supplementation in those with deficiency in large-scale randomized controlled trials.”

However, Dr. Butler-Laporte and Dr. Richards, of the Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, also note the study has several limitations, including the fact that the lifetime exposure to lower vitamin D levels captured by Mendelian randomization may result in larger effect sizes than in conventional trials.

Prior RCTS underpowered to detect effects of vitamin D supplements

“There are several potential mechanisms by which vitamin D could be protective for cardiovascular mortality, including mechanisms linking low vitamin D status with hyperparathyroidism and low serum calcium and phosphate,” write Dr. Burgess of the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge (England), and coauthors.

They also highlight that vitamin D is “further implicated in endothelial cell function” and affects the transcription of genes linked to cell division and apoptosis, providing “potential mechanisms implicating vitamin D for cancer.”

The researchers note that, while epidemiologic studies have “consistently” found a link between 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and other chronic diseases, several large trials of vitamin D supplementation have reported “null results.”

They argue, however, that many of these trials have recruited individuals “irrespective of baseline 25(OH)D concentration” and have been underpowered to detect the effects of supplementation.

To overcome these limitations, the team gathered data from the UK Biobank, the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cardiovascular Disease (EPIC-CVD) study, 31 studies from the Vitamin D Studies Collaboration (VitDSC), and two Copenhagen population-based studies.

They first performed an observational study that included 384,721 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who had a valid 25(OH)D measurement and no previously known cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Researchers also included 67,992 participants from the VitDSC studies who did not have previously known cardiovascular disease. They analyzed 25(OH)D concentrations, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and major incident cardiovascular morbidity and mortality using individual participant data.

The results showed that, at low 25(OH)D concentrations, there was an inverse association between 25(OH)D and incident CHD, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

Next, the team conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis on 333,002 individuals from the UK Biobank and 26,336 from EPIC-CVD who were of European ancestry and had both a valid 25(OH)D measurement and genetic data that passed quality-control steps.

Information on 31,362 participants in the Copenhagen population-based studies was also included, giving a total of 386,406 individuals, of whom 33,546 had CHD, 18,166 had a stroke, and 27,885 died.

The mean age of participants ranged from 54.8 to 57.5 years, and between 53.4% and 55.4% were female.

Up to 7% of study participants were vitamin D deficient

The 25(OH)D analysis indicated that 3.9% of UK Biobank and 3.7% of Copenhagen study participants were deficient, compared with 6.9% in EPIC-CVD.

Across the full range of 25(OH)D concentrations, there was no significant association between genetically predicted 25(OH)D levels and CHD, stroke, or all-cause mortality.

However, restricting the analysis to individuals deemed vitamin D deficient (25[OH]D concentration < 25 nmol/L) revealed there was “strong evidence” for an inverse association with all-cause mortality, at an odds ratio per 10 nmol/L increase in genetically predicted 25(OH)D concentration of 0.69 (P < .0001), the team notes.

There were also nonsignificant associations between being in the deficient stratum and CHD, at an odds ratio of 0.89 (P = .14), and stroke, at an odds ratio of 0.85 (P = .09).

Further analysis suggests the association between 25(OH)D concentrations and all-cause mortality has a “clear threshold shape,” the researchers say, with evidence of an inverse association at concentrations below 40 nmol/L and null associations above that threshold.

They acknowledge, however, that their study has several potential limitations, including the assumption in their Mendelian randomization that the “only causal pathway from the genetic variants to the outcome is via 25(OH)D concentrations.”

Moreover, the genetic variants may affect 25(OH)D concentrations in a different way from “dietary supplementation or other clinical interventions.”

They also concede that their study was limited to middle-aged participants of European ancestries, which means the findings “might not be applicable to other populations.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Health Data Research UK, Cancer Research UK, and International Agency for Research on Cancer. Dr. Burgess has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. obesity rates soar in early adulthood

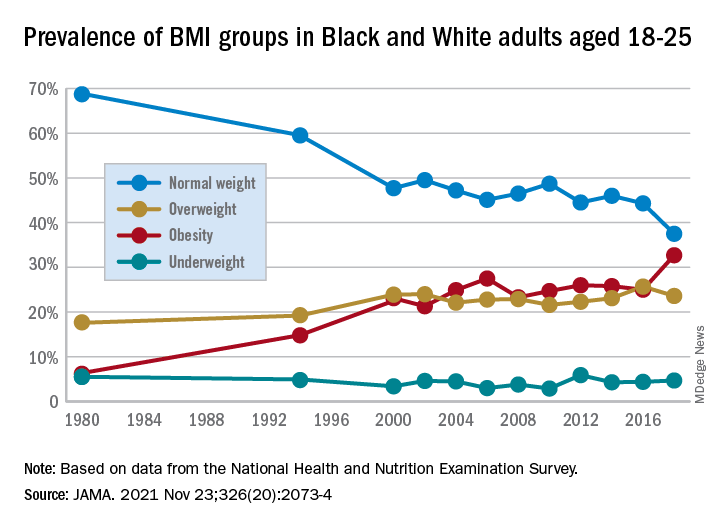

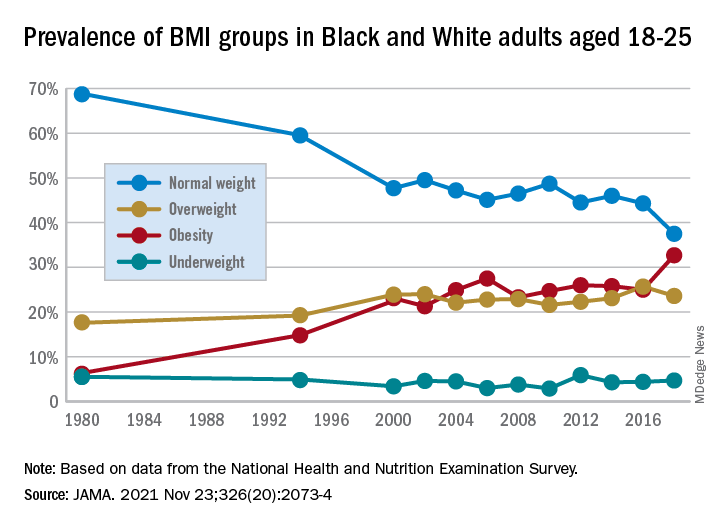

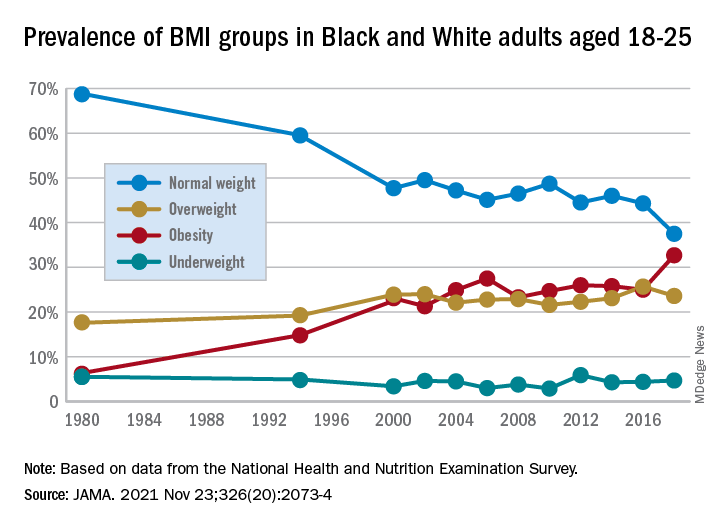

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fueling an ‘already raging fire’: Fifth COVID surge approaches

“A significant rise in cases just before Thanksgiving is not what we want to be seeing,” said Stephen Kissler, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher and data modeler at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

Dr. Kissler said he’d rather see increases in daily cases coming 2 weeks after busy travel periods, as that would mean they could come back down as people returned to their routines.

Seeing big increases in cases ahead of the holidays, he said, “is sort of like adding fuel to an already raging fire.”

Last winter, vaccines hadn’t been rolled out as the nation prepared for Thanksgiving. COVID-19 was burning through family gatherings.

But now that two-thirds of Americans over age 5 are fully vaccinated and booster doses are approved for all adults, will a rise in cases translate, once again, into a strain on our still thinly stretched healthcare system?

Experts say the vaccines are keeping people out of the hospital, which will help. And new antiviral pills are coming that seem to be able to cut a COVID-19 infection off at the knees, at least according to early data. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration panel meets next week to discuss the first application for a pill by Merck.

But experts caution that the coming surge will almost certainly tax hospitals again, especially in areas with lower vaccination rates.

And even states where blood testing shows that significant numbers of people have antibodies after a COVID-19 infection aren’t out of the woods, in part because we still don’t know how long the immunity generated by infection may last.

“Erosion of immunity”

“It’s hard to know how much risk is out there,” said Jeffrey Shaman, PhD, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, who has been modeling the trajectory of the pandemic.

“We’re estimating, unfortunately, and we have for many weeks now, that there is an erosion of immunity,” Dr. Shaman said. “I think it could get bad. How bad? I’m not sure.”

Ali Mokdad, PhD, a professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, agrees.

Because there are so few studies on how long immunity from natural infection lasts, Dr. Mokdad and his colleagues are assuming that waning immunity after infection happens at least as quickly as it does after vaccination.

Their model is predicting that the average number of daily cases will peak at around 100,000, with another 100,000 going undetected, and will stay at that level until the end of January, as some states recover from their surges and others pick up steam.

While the number of daily deaths won’t climb to the heights seen during the summer surge, Dr. Mokdad said their model is predicting that daily deaths will climb again to about 1,200 a day.

“We are almost there right now, and it will be with us for a while,” he said. “We are predicting 881,000 deaths by March 1.”

The United States has currently recorded 773,000 COVID-19 deaths, so Dr. Mokdad is predicting about 120,000 more deaths between now and then.

He said his model shows that more than half of those deaths could be prevented if 95% of Americans wore their masks while in close proximity to strangers.

Currently, only about 36% of Americans are consistently wearing masks, according to surveys. While people are moving around more now, mobility is at prepandemic levels in some states.

“The rise that you are seeing right now is high mobility and low mask wearing in the United States,” Dr. Mokdad said.

The solution, he said, is for all adults to get another dose of vaccine — he doesn’t like calling it a booster.

“Because they’re vaccinated and they have two doses they have a false sense of security that they are protected. We needed to come ahead of it immediately and say you need a third dose, and we were late to do so,” Dr. Mokdad said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“A significant rise in cases just before Thanksgiving is not what we want to be seeing,” said Stephen Kissler, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher and data modeler at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

Dr. Kissler said he’d rather see increases in daily cases coming 2 weeks after busy travel periods, as that would mean they could come back down as people returned to their routines.

Seeing big increases in cases ahead of the holidays, he said, “is sort of like adding fuel to an already raging fire.”

Last winter, vaccines hadn’t been rolled out as the nation prepared for Thanksgiving. COVID-19 was burning through family gatherings.

But now that two-thirds of Americans over age 5 are fully vaccinated and booster doses are approved for all adults, will a rise in cases translate, once again, into a strain on our still thinly stretched healthcare system?

Experts say the vaccines are keeping people out of the hospital, which will help. And new antiviral pills are coming that seem to be able to cut a COVID-19 infection off at the knees, at least according to early data. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration panel meets next week to discuss the first application for a pill by Merck.

But experts caution that the coming surge will almost certainly tax hospitals again, especially in areas with lower vaccination rates.

And even states where blood testing shows that significant numbers of people have antibodies after a COVID-19 infection aren’t out of the woods, in part because we still don’t know how long the immunity generated by infection may last.

“Erosion of immunity”

“It’s hard to know how much risk is out there,” said Jeffrey Shaman, PhD, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, who has been modeling the trajectory of the pandemic.

“We’re estimating, unfortunately, and we have for many weeks now, that there is an erosion of immunity,” Dr. Shaman said. “I think it could get bad. How bad? I’m not sure.”

Ali Mokdad, PhD, a professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, agrees.

Because there are so few studies on how long immunity from natural infection lasts, Dr. Mokdad and his colleagues are assuming that waning immunity after infection happens at least as quickly as it does after vaccination.

Their model is predicting that the average number of daily cases will peak at around 100,000, with another 100,000 going undetected, and will stay at that level until the end of January, as some states recover from their surges and others pick up steam.

While the number of daily deaths won’t climb to the heights seen during the summer surge, Dr. Mokdad said their model is predicting that daily deaths will climb again to about 1,200 a day.

“We are almost there right now, and it will be with us for a while,” he said. “We are predicting 881,000 deaths by March 1.”

The United States has currently recorded 773,000 COVID-19 deaths, so Dr. Mokdad is predicting about 120,000 more deaths between now and then.

He said his model shows that more than half of those deaths could be prevented if 95% of Americans wore their masks while in close proximity to strangers.

Currently, only about 36% of Americans are consistently wearing masks, according to surveys. While people are moving around more now, mobility is at prepandemic levels in some states.

“The rise that you are seeing right now is high mobility and low mask wearing in the United States,” Dr. Mokdad said.

The solution, he said, is for all adults to get another dose of vaccine — he doesn’t like calling it a booster.

“Because they’re vaccinated and they have two doses they have a false sense of security that they are protected. We needed to come ahead of it immediately and say you need a third dose, and we were late to do so,” Dr. Mokdad said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“A significant rise in cases just before Thanksgiving is not what we want to be seeing,” said Stephen Kissler, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher and data modeler at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

Dr. Kissler said he’d rather see increases in daily cases coming 2 weeks after busy travel periods, as that would mean they could come back down as people returned to their routines.

Seeing big increases in cases ahead of the holidays, he said, “is sort of like adding fuel to an already raging fire.”

Last winter, vaccines hadn’t been rolled out as the nation prepared for Thanksgiving. COVID-19 was burning through family gatherings.

But now that two-thirds of Americans over age 5 are fully vaccinated and booster doses are approved for all adults, will a rise in cases translate, once again, into a strain on our still thinly stretched healthcare system?

Experts say the vaccines are keeping people out of the hospital, which will help. And new antiviral pills are coming that seem to be able to cut a COVID-19 infection off at the knees, at least according to early data. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration panel meets next week to discuss the first application for a pill by Merck.

But experts caution that the coming surge will almost certainly tax hospitals again, especially in areas with lower vaccination rates.

And even states where blood testing shows that significant numbers of people have antibodies after a COVID-19 infection aren’t out of the woods, in part because we still don’t know how long the immunity generated by infection may last.

“Erosion of immunity”

“It’s hard to know how much risk is out there,” said Jeffrey Shaman, PhD, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, who has been modeling the trajectory of the pandemic.

“We’re estimating, unfortunately, and we have for many weeks now, that there is an erosion of immunity,” Dr. Shaman said. “I think it could get bad. How bad? I’m not sure.”

Ali Mokdad, PhD, a professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, agrees.

Because there are so few studies on how long immunity from natural infection lasts, Dr. Mokdad and his colleagues are assuming that waning immunity after infection happens at least as quickly as it does after vaccination.

Their model is predicting that the average number of daily cases will peak at around 100,000, with another 100,000 going undetected, and will stay at that level until the end of January, as some states recover from their surges and others pick up steam.

While the number of daily deaths won’t climb to the heights seen during the summer surge, Dr. Mokdad said their model is predicting that daily deaths will climb again to about 1,200 a day.

“We are almost there right now, and it will be with us for a while,” he said. “We are predicting 881,000 deaths by March 1.”

The United States has currently recorded 773,000 COVID-19 deaths, so Dr. Mokdad is predicting about 120,000 more deaths between now and then.

He said his model shows that more than half of those deaths could be prevented if 95% of Americans wore their masks while in close proximity to strangers.

Currently, only about 36% of Americans are consistently wearing masks, according to surveys. While people are moving around more now, mobility is at prepandemic levels in some states.

“The rise that you are seeing right now is high mobility and low mask wearing in the United States,” Dr. Mokdad said.

The solution, he said, is for all adults to get another dose of vaccine — he doesn’t like calling it a booster.

“Because they’re vaccinated and they have two doses they have a false sense of security that they are protected. We needed to come ahead of it immediately and say you need a third dose, and we were late to do so,” Dr. Mokdad said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Swell in off-label antipsychotic prescribing ‘not harmless’

A growing trend of off-label, low-dose antipsychotic prescribing to treat disorders such as anxiety and insomnia has been tied to an increased risk of cardiometabolic death, new research shows.

Investigators studied data from large Swedish registries on over 420,000 individuals without previous psychotic, bipolar, or cardiometabolic disorders and found that off-label treatment with olanzapine or quetiapine for 6 to 12 months – even at a low dose – was associated with an almost twofold higher risk of cardiometabolic mortality, compared to no treatment. The risk remained elevated after 12 months, but the finding was not deemed significant.

“Clinicians should be made aware that low-dose treatment with these drugs is probably not a harmless choice for insomnia and anxiety, and while they have the benefit of not being addictive and [are] seemingly effective, they might come at a cost of shortening patients’ life span,” study investigator Jonas Berge, MD, PhD, associate professor and resident psychiatrist, Lund University, Sweden, said in an interview.

“Clinicians should take this information into account when prescribing the drugs and also monitor the patients with regular physical examinations and blood tests in the same way as when treating patients with psychosis with higher doses of these drugs,” he said.

The study was published online Nov. 9 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

A growing trend

Use of low-dose antipsychotics to treat a variety of psychiatric and behavioral disturbances, including anxiety, insomnia, and agitation, has “surged in popularity,” the authors wrote.

Quetiapine and olanzapine “rank as two of the most frequently prescribed second-generation antipsychotics and, next to clozapine, are considered to exhort the highest risk for cardiometabolic sequelae, including components of metabolic syndrome,” they added.

Previous research examining the association between second-generation antipsychotics and placebo has either not focused on cardiometabolic-specific causes or has examined only cohorts with severe mental illness, so those findings “do not necessarily generalize to others treated off-label,” they noted.

“The motivation for the study came from my work as a psychiatrist, in which I’ve noticed that the off-label use of these medications [olanzapine and quetiapine] for anxiety and insomnia seems highly prevalent, and that many patients seem to gain a lot of weight, despite low doses,” Dr. Berge said.

There is “evidence to suggest that clinicians may underappreciate cardiometabolic risks owing to antipsychotic treatment, as routine screening is often incomplete or inconsistent,” the authors noted.

“To do a risk-benefit analysis of these drugs in low doses, the risks involved – as well as the effects, of course – need to be studied,” Dr. Berge stated.

To investigate the question, the researchers turned to three large cross-linked Swedish registers: the National Patient Register, containing demographic and medical data; the Prescribed Drug Register; and the Cause of Death Register.

They identified all individuals aged 18 years and older with at least one psychiatric visit (inpatient or outpatient) between July 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2016, to see how many were prescribed low-dose olanzapine or quetiapine (defined as ≤ 5 mg/day of olanzapine or olanzapine equivalent [OE]), which was used as a proxy marker for off-label treatment, since this dose is considered subtherapeutic for severe mental illness.

They calculated two time-dependent variables – cumulative dose and past annual average dose – and then used those to compute three different exposure valuables: those treated with low-dose OE; cumulative exposure (i.e., period treated with an average 5 mg/day); and a continuous variable “corresponding to each year exposed OE 5 mg/day.”

The primary outcome was set as mortality from cardiometabolic-related disorders, while secondary outcomes were disease-specific and all-cause mortality.

‘Weak’ association

The final cohort consisted of 428,525 individuals (mean [SD] age, 36.8 [15.4] years, 52.7% female) at baseline, with observation taking place over a mean of 4.8 years [range, 1 day to 10.5 years]) or a total of over 2 million (2,062,241) person-years.

Of the cohort, 4.3% (n = 18,317) had at least two prescriptions for either olanzapine or quetiapine (although subsequently, 86.5% were censored for exceeding the average OE dose of 5 mg/day).

By the end of the study, 3.1% of the cohort had died during the observation time, and of these, 69.5% were from disease-specific causes, while close to one-fifth (19.5%) were from cardiometabolic-specific causes.

On the whole, treatment status (i.e., treated vs. untreated) was not significantly associated with cardiometabolic mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], .86 [95% confidence interval, 0.64-1.15]; P = .307).

Compared to no treatment, treatment with olanzapine or quetiapine for less than 6 months was significantly associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR, .56 [.37 – .87]; P = .010). On the other hand, treatment for 6-12 months was significantly associated with an almost twofold increased risk (adjusted HR, 1.89 [1.22-2.92]; P = .004). The increased risk continued beyond 12 months, although the difference no longer remained significant.

“In the subgroup analysis consisting of individuals who had ever been treated with olanzapine/quetiapine, starting at the date of their first prescription, the hazard for cardiometabolic mortality increased significantly by 45% (6%-99%; P = .019) for every year exposed to an average 5 mg/day,” the authors reported.

The authors concluded that the association between low-dose olanzapine/quetiapine treatment and cardiometabolic mortality was present, but “weak.”

The hazard for disease-specific mortality also significantly increased with each year exposed to an average of 5 mg/day of OE (HR, 1.24 [1.03-1.50]; P = .026).

Treatment status similarly was associated with all-cause mortality (HR, 1.16 [1.03-1.30]; P = .012), although the increased hazard for all-cause mortality with each year of exposure was not considered significant.

“The findings of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that continuous low-dose treatment with these drugs is associated with increased cardiometabolic mortality, but ,” Dr. Berge said.

Seek alternatives

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, called it a “timely paper” and “an important concept [because] low-doses of these antipsychotics are frequently prescribed across America and there has been less data on the safety [of these antipsychotics at lower doses].”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, said that this “important report reminds us that there are metabolic safety concerns, even at low doses, where these medications are often used off label.”

He advised clinicians to “seek alternatives, and alternatives that are on-label, for conditions like anxiety and sleep disturbances.”

This work was supported by the South Region Board ALF, Sweden. Dr. Berge and coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A growing trend of off-label, low-dose antipsychotic prescribing to treat disorders such as anxiety and insomnia has been tied to an increased risk of cardiometabolic death, new research shows.

Investigators studied data from large Swedish registries on over 420,000 individuals without previous psychotic, bipolar, or cardiometabolic disorders and found that off-label treatment with olanzapine or quetiapine for 6 to 12 months – even at a low dose – was associated with an almost twofold higher risk of cardiometabolic mortality, compared to no treatment. The risk remained elevated after 12 months, but the finding was not deemed significant.

“Clinicians should be made aware that low-dose treatment with these drugs is probably not a harmless choice for insomnia and anxiety, and while they have the benefit of not being addictive and [are] seemingly effective, they might come at a cost of shortening patients’ life span,” study investigator Jonas Berge, MD, PhD, associate professor and resident psychiatrist, Lund University, Sweden, said in an interview.

“Clinicians should take this information into account when prescribing the drugs and also monitor the patients with regular physical examinations and blood tests in the same way as when treating patients with psychosis with higher doses of these drugs,” he said.

The study was published online Nov. 9 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

A growing trend

Use of low-dose antipsychotics to treat a variety of psychiatric and behavioral disturbances, including anxiety, insomnia, and agitation, has “surged in popularity,” the authors wrote.

Quetiapine and olanzapine “rank as two of the most frequently prescribed second-generation antipsychotics and, next to clozapine, are considered to exhort the highest risk for cardiometabolic sequelae, including components of metabolic syndrome,” they added.

Previous research examining the association between second-generation antipsychotics and placebo has either not focused on cardiometabolic-specific causes or has examined only cohorts with severe mental illness, so those findings “do not necessarily generalize to others treated off-label,” they noted.

“The motivation for the study came from my work as a psychiatrist, in which I’ve noticed that the off-label use of these medications [olanzapine and quetiapine] for anxiety and insomnia seems highly prevalent, and that many patients seem to gain a lot of weight, despite low doses,” Dr. Berge said.

There is “evidence to suggest that clinicians may underappreciate cardiometabolic risks owing to antipsychotic treatment, as routine screening is often incomplete or inconsistent,” the authors noted.

“To do a risk-benefit analysis of these drugs in low doses, the risks involved – as well as the effects, of course – need to be studied,” Dr. Berge stated.

To investigate the question, the researchers turned to three large cross-linked Swedish registers: the National Patient Register, containing demographic and medical data; the Prescribed Drug Register; and the Cause of Death Register.

They identified all individuals aged 18 years and older with at least one psychiatric visit (inpatient or outpatient) between July 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2016, to see how many were prescribed low-dose olanzapine or quetiapine (defined as ≤ 5 mg/day of olanzapine or olanzapine equivalent [OE]), which was used as a proxy marker for off-label treatment, since this dose is considered subtherapeutic for severe mental illness.

They calculated two time-dependent variables – cumulative dose and past annual average dose – and then used those to compute three different exposure valuables: those treated with low-dose OE; cumulative exposure (i.e., period treated with an average 5 mg/day); and a continuous variable “corresponding to each year exposed OE 5 mg/day.”

The primary outcome was set as mortality from cardiometabolic-related disorders, while secondary outcomes were disease-specific and all-cause mortality.

‘Weak’ association

The final cohort consisted of 428,525 individuals (mean [SD] age, 36.8 [15.4] years, 52.7% female) at baseline, with observation taking place over a mean of 4.8 years [range, 1 day to 10.5 years]) or a total of over 2 million (2,062,241) person-years.

Of the cohort, 4.3% (n = 18,317) had at least two prescriptions for either olanzapine or quetiapine (although subsequently, 86.5% were censored for exceeding the average OE dose of 5 mg/day).

By the end of the study, 3.1% of the cohort had died during the observation time, and of these, 69.5% were from disease-specific causes, while close to one-fifth (19.5%) were from cardiometabolic-specific causes.

On the whole, treatment status (i.e., treated vs. untreated) was not significantly associated with cardiometabolic mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], .86 [95% confidence interval, 0.64-1.15]; P = .307).

Compared to no treatment, treatment with olanzapine or quetiapine for less than 6 months was significantly associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR, .56 [.37 – .87]; P = .010). On the other hand, treatment for 6-12 months was significantly associated with an almost twofold increased risk (adjusted HR, 1.89 [1.22-2.92]; P = .004). The increased risk continued beyond 12 months, although the difference no longer remained significant.

“In the subgroup analysis consisting of individuals who had ever been treated with olanzapine/quetiapine, starting at the date of their first prescription, the hazard for cardiometabolic mortality increased significantly by 45% (6%-99%; P = .019) for every year exposed to an average 5 mg/day,” the authors reported.

The authors concluded that the association between low-dose olanzapine/quetiapine treatment and cardiometabolic mortality was present, but “weak.”

The hazard for disease-specific mortality also significantly increased with each year exposed to an average of 5 mg/day of OE (HR, 1.24 [1.03-1.50]; P = .026).

Treatment status similarly was associated with all-cause mortality (HR, 1.16 [1.03-1.30]; P = .012), although the increased hazard for all-cause mortality with each year of exposure was not considered significant.

“The findings of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that continuous low-dose treatment with these drugs is associated with increased cardiometabolic mortality, but ,” Dr. Berge said.

Seek alternatives

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, called it a “timely paper” and “an important concept [because] low-doses of these antipsychotics are frequently prescribed across America and there has been less data on the safety [of these antipsychotics at lower doses].”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, said that this “important report reminds us that there are metabolic safety concerns, even at low doses, where these medications are often used off label.”

He advised clinicians to “seek alternatives, and alternatives that are on-label, for conditions like anxiety and sleep disturbances.”

This work was supported by the South Region Board ALF, Sweden. Dr. Berge and coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A growing trend of off-label, low-dose antipsychotic prescribing to treat disorders such as anxiety and insomnia has been tied to an increased risk of cardiometabolic death, new research shows.

Investigators studied data from large Swedish registries on over 420,000 individuals without previous psychotic, bipolar, or cardiometabolic disorders and found that off-label treatment with olanzapine or quetiapine for 6 to 12 months – even at a low dose – was associated with an almost twofold higher risk of cardiometabolic mortality, compared to no treatment. The risk remained elevated after 12 months, but the finding was not deemed significant.

“Clinicians should be made aware that low-dose treatment with these drugs is probably not a harmless choice for insomnia and anxiety, and while they have the benefit of not being addictive and [are] seemingly effective, they might come at a cost of shortening patients’ life span,” study investigator Jonas Berge, MD, PhD, associate professor and resident psychiatrist, Lund University, Sweden, said in an interview.

“Clinicians should take this information into account when prescribing the drugs and also monitor the patients with regular physical examinations and blood tests in the same way as when treating patients with psychosis with higher doses of these drugs,” he said.

The study was published online Nov. 9 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

A growing trend

Use of low-dose antipsychotics to treat a variety of psychiatric and behavioral disturbances, including anxiety, insomnia, and agitation, has “surged in popularity,” the authors wrote.

Quetiapine and olanzapine “rank as two of the most frequently prescribed second-generation antipsychotics and, next to clozapine, are considered to exhort the highest risk for cardiometabolic sequelae, including components of metabolic syndrome,” they added.

Previous research examining the association between second-generation antipsychotics and placebo has either not focused on cardiometabolic-specific causes or has examined only cohorts with severe mental illness, so those findings “do not necessarily generalize to others treated off-label,” they noted.

“The motivation for the study came from my work as a psychiatrist, in which I’ve noticed that the off-label use of these medications [olanzapine and quetiapine] for anxiety and insomnia seems highly prevalent, and that many patients seem to gain a lot of weight, despite low doses,” Dr. Berge said.

There is “evidence to suggest that clinicians may underappreciate cardiometabolic risks owing to antipsychotic treatment, as routine screening is often incomplete or inconsistent,” the authors noted.

“To do a risk-benefit analysis of these drugs in low doses, the risks involved – as well as the effects, of course – need to be studied,” Dr. Berge stated.

To investigate the question, the researchers turned to three large cross-linked Swedish registers: the National Patient Register, containing demographic and medical data; the Prescribed Drug Register; and the Cause of Death Register.

They identified all individuals aged 18 years and older with at least one psychiatric visit (inpatient or outpatient) between July 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2016, to see how many were prescribed low-dose olanzapine or quetiapine (defined as ≤ 5 mg/day of olanzapine or olanzapine equivalent [OE]), which was used as a proxy marker for off-label treatment, since this dose is considered subtherapeutic for severe mental illness.

They calculated two time-dependent variables – cumulative dose and past annual average dose – and then used those to compute three different exposure valuables: those treated with low-dose OE; cumulative exposure (i.e., period treated with an average 5 mg/day); and a continuous variable “corresponding to each year exposed OE 5 mg/day.”

The primary outcome was set as mortality from cardiometabolic-related disorders, while secondary outcomes were disease-specific and all-cause mortality.

‘Weak’ association

The final cohort consisted of 428,525 individuals (mean [SD] age, 36.8 [15.4] years, 52.7% female) at baseline, with observation taking place over a mean of 4.8 years [range, 1 day to 10.5 years]) or a total of over 2 million (2,062,241) person-years.

Of the cohort, 4.3% (n = 18,317) had at least two prescriptions for either olanzapine or quetiapine (although subsequently, 86.5% were censored for exceeding the average OE dose of 5 mg/day).

By the end of the study, 3.1% of the cohort had died during the observation time, and of these, 69.5% were from disease-specific causes, while close to one-fifth (19.5%) were from cardiometabolic-specific causes.

On the whole, treatment status (i.e., treated vs. untreated) was not significantly associated with cardiometabolic mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], .86 [95% confidence interval, 0.64-1.15]; P = .307).

Compared to no treatment, treatment with olanzapine or quetiapine for less than 6 months was significantly associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR, .56 [.37 – .87]; P = .010). On the other hand, treatment for 6-12 months was significantly associated with an almost twofold increased risk (adjusted HR, 1.89 [1.22-2.92]; P = .004). The increased risk continued beyond 12 months, although the difference no longer remained significant.

“In the subgroup analysis consisting of individuals who had ever been treated with olanzapine/quetiapine, starting at the date of their first prescription, the hazard for cardiometabolic mortality increased significantly by 45% (6%-99%; P = .019) for every year exposed to an average 5 mg/day,” the authors reported.

The authors concluded that the association between low-dose olanzapine/quetiapine treatment and cardiometabolic mortality was present, but “weak.”

The hazard for disease-specific mortality also significantly increased with each year exposed to an average of 5 mg/day of OE (HR, 1.24 [1.03-1.50]; P = .026).

Treatment status similarly was associated with all-cause mortality (HR, 1.16 [1.03-1.30]; P = .012), although the increased hazard for all-cause mortality with each year of exposure was not considered significant.

“The findings of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that continuous low-dose treatment with these drugs is associated with increased cardiometabolic mortality, but ,” Dr. Berge said.

Seek alternatives

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, called it a “timely paper” and “an important concept [because] low-doses of these antipsychotics are frequently prescribed across America and there has been less data on the safety [of these antipsychotics at lower doses].”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, said that this “important report reminds us that there are metabolic safety concerns, even at low doses, where these medications are often used off label.”

He advised clinicians to “seek alternatives, and alternatives that are on-label, for conditions like anxiety and sleep disturbances.”

This work was supported by the South Region Board ALF, Sweden. Dr. Berge and coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Firefighters’ blood pressure surges when they are called to action

In response to a 911 alert or page, firefighters’ systolic and diastolic blood pressure surges and their heart rate accelerates, with a similar response whether the call is for a fire or medical emergency, a small study suggests.

On average, the 41 firefighters monitored in the study, who were middle-aged and overweight, had a 9% increase in systolic blood pressure when called to a fire, a 9% increase in diastolic blood pressure when called to a medical emergency, and a 16% increase in heart rate for both types of calls.

Senior study author Deborah Feairheller, PhD, presented these results at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Firefighters have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than that of the general population, explained Dr. Feairheller, director of the Hypertension and Endothelial Function with Aerobic and Resistance Training (HEART) Lab and clinical associate professor of kinesiology at the University of New Hampshire, Durham.

More than 50% of firefighter deaths in the line of duty are from CVD, she noted. Moreover, almost 75% of firefighters have hypertension and fewer than 25% have it under control.

The study findings show that all emergency and first responders “should know what their typical blood pressure level is and be aware of how it fluctuates,” Dr. Feairheller said in a press release from the AHA. “Most important, if they have high blood pressure, they should make sure it is well controlled,” she said.

“I really hope that fire departments everywhere see these data, rise to the occasion, and advocate for BP awareness in their crews,” Dr. Feairheller, a volunteer firefighter, said in an interview.

“I do think this has value to any occupation that wears a pager,” she added. “Clinicians, physicians, other emergency responders, all of those occupations are stressful and could place people at risk if they have undiagnosed or uncontrolled hypertension.”

Invited to comment, Comilla Sasson, MD, PhD, an emergency department physician who was not involved with this research, said in an interview that she saw parallels between stress experienced by firefighters and, for example, emergency department physicians.

The transient increases in BP, both systolic and diastolic, along with the heart rate are likely due to the body’s natural fight or flight response to an emergency call, including increases in epinephrine and cortisol, said Dr. Sasson, vice president of science and innovation for emergency cardiovascular care at the American Heart Association.

“The thing that is most interesting to me,” said Dr. Sasson, who can be subject to a series of high-stress situations on a shift, such as multiple trauma victims, a stroke victim, or a person in cardiac arrest, is “what is the cumulative impact of this over time?”

She said she wonders if “having to be ‘ready to go’ at any time, along with disruptions in sleep/wake schedules, and poorer eating and working-out habits when you are on shift, has long-term sequelae on the body.”

Stress-related surges in blood pressure “could be a reason for worse health outcomes in this group,” Dr. Sasson said, adding that this needs to be investigated further.

Firefighters with high normal BP, high BMI

Dr. Feairheller and colleagues recruited 41 volunteer and employee firefighters from suburban Philadelphia and Dover, N.H.

On average, the 37 men and 4 women had a mean age of 41 years, had been working as firefighters for 16.9 years, and had a mean body mass index of 30.3 kg/m2.

They wore ambulatory blood pressure monitors during an on-call work shift for at least 12 consecutive hours.

In addition to the automatic readings, the participants were instructed to prompt the machine to take a reading whenever a pager or emergency call sounded or when they felt they were entering a stressful situation.

Over the 12-hour shift, on average, participants had a blood pressure of 131/79.3 mm Hg and a heart rate of 75.7 bpm.

When they were alerted go to a fire, their blood pressure surged by 19.2/10.5 mm Hg, and their heart rate rose to 85.5 bpm.

Similarly, when they were alerted to go to a medical emergency, their blood pressure jumped up by 18.7/16.5 mm Hg and their heart rate climbed to 90.5 bpm.

The surges in blood pressure and heart rate were similar when participants were riding in the fire truck to a call or when the call turned out to be a false alarm.

What can be done?

“If we can increase awareness and identify specific risk factors in firefighters,” Dr. Feairheller said, this could “save a life of someone who spends their day saving lives and property.”

To start, “regular, in-station or home BP monitoring should be encouraged,” she said. “Firefighters should start to track their BP levels in the morning, at night, at work. Being a volunteer firefighter myself, I know the stress and anxiety and sadness and heavy work that comes with the job,” she said. “I want to be able to do what I can to help make the crews healthier.”

Dr. Sasson suggested that ways to increase awareness and improve the health of firefighters might include “counseling, appropriate breaks, possibly food service/delivery to provide better nutritional options, built-in time for exercise (gym or cardio equipment on site), and discussions about how stress can impact the body over time.”

It is important to advocate for better mental health care, because people may have PTSD, depression, substance abuse, or other mental health conditions brought on by their stressful jobs, she said.

“Also, it would be interesting to know what is the current state of health monitoring (both physical, mental, and emotional) that occurs for firefighters,” she said.

The American Heart Association funded the study. The authors and Dr. Sasson report no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In response to a 911 alert or page, firefighters’ systolic and diastolic blood pressure surges and their heart rate accelerates, with a similar response whether the call is for a fire or medical emergency, a small study suggests.

On average, the 41 firefighters monitored in the study, who were middle-aged and overweight, had a 9% increase in systolic blood pressure when called to a fire, a 9% increase in diastolic blood pressure when called to a medical emergency, and a 16% increase in heart rate for both types of calls.

Senior study author Deborah Feairheller, PhD, presented these results at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Firefighters have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than that of the general population, explained Dr. Feairheller, director of the Hypertension and Endothelial Function with Aerobic and Resistance Training (HEART) Lab and clinical associate professor of kinesiology at the University of New Hampshire, Durham.

More than 50% of firefighter deaths in the line of duty are from CVD, she noted. Moreover, almost 75% of firefighters have hypertension and fewer than 25% have it under control.

The study findings show that all emergency and first responders “should know what their typical blood pressure level is and be aware of how it fluctuates,” Dr. Feairheller said in a press release from the AHA. “Most important, if they have high blood pressure, they should make sure it is well controlled,” she said.

“I really hope that fire departments everywhere see these data, rise to the occasion, and advocate for BP awareness in their crews,” Dr. Feairheller, a volunteer firefighter, said in an interview.

“I do think this has value to any occupation that wears a pager,” she added. “Clinicians, physicians, other emergency responders, all of those occupations are stressful and could place people at risk if they have undiagnosed or uncontrolled hypertension.”

Invited to comment, Comilla Sasson, MD, PhD, an emergency department physician who was not involved with this research, said in an interview that she saw parallels between stress experienced by firefighters and, for example, emergency department physicians.

The transient increases in BP, both systolic and diastolic, along with the heart rate are likely due to the body’s natural fight or flight response to an emergency call, including increases in epinephrine and cortisol, said Dr. Sasson, vice president of science and innovation for emergency cardiovascular care at the American Heart Association.

“The thing that is most interesting to me,” said Dr. Sasson, who can be subject to a series of high-stress situations on a shift, such as multiple trauma victims, a stroke victim, or a person in cardiac arrest, is “what is the cumulative impact of this over time?”

She said she wonders if “having to be ‘ready to go’ at any time, along with disruptions in sleep/wake schedules, and poorer eating and working-out habits when you are on shift, has long-term sequelae on the body.”

Stress-related surges in blood pressure “could be a reason for worse health outcomes in this group,” Dr. Sasson said, adding that this needs to be investigated further.

Firefighters with high normal BP, high BMI

Dr. Feairheller and colleagues recruited 41 volunteer and employee firefighters from suburban Philadelphia and Dover, N.H.

On average, the 37 men and 4 women had a mean age of 41 years, had been working as firefighters for 16.9 years, and had a mean body mass index of 30.3 kg/m2.

They wore ambulatory blood pressure monitors during an on-call work shift for at least 12 consecutive hours.