User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Why is vitamin D hype so impervious to evidence?

The vitamin D story exudes teaching points: It offers a master class in critical appraisal, connecting the concepts of biologic plausibility, flawed surrogate markers, confounded observational studies, and slews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing no benefits on health outcomes.

Yet despite the utter lack of benefit seen in trials, the hype continues. And the pandemic has only enhanced this hype as an onslaught of papers have reported the association of low vitamin D levels and COVID-19 disease.

My questions are simple: Why doesn’t the evidence persuade people? How many nonsignificant trials do we need before researchers stop studying vitamin D, doctors stop (routinely) measuring levels, and patients stop wasting money on the unhelpful supplement? What are the implications for this lack of persuasion?

Before exploring these questions, I want to set out that symptomatic vitamin deficiencies of any sort ought to be corrected.

Biologic plausibility and the pull of observational studies

It has long been known that vitamin D is crucial for bone health and that it can be produced in the skin with sun exposure. In the last decade, however, experts note that nearly every tissue and cell in our body has a vitamin D receptor. It then follows that if this many cells in the body can activate vitamin D, it must be vital for cardiovascular health, immune function, cancer prevention: basically, everything health related.

Oodles of observational studies have found that low serum levels of vitamin D correlate with higher mortality from all causes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and now even COVID-19. Yet no matter the amount of statistical adjustment in these studies, we cannot know whether these associations are due to true causality.

The major issue is confounding: That is, people with low vitamin D levels have other conditions or diseases that lead to higher rates of ill health. Consider a patient with obesity, arthritis, and cognitive decline; this person is unlikely to do much exercise in the sun and may have low vitamin D levels. The low vitamin D level is simply a marker of overall poor health.

The randomized controlled trials tell a clear story

There are hundreds of vitamin D RCTs. The results simplify into one sentence: Vitamin D supplements do not improve health outcomes.

Here is a short summary of some recent studies.

VITAL, a massive (N > 25,000) RCT with 5 years of follow-up, compared vitamin D supplements to placebo and found no differences in the primary endpoints of cancer or cardiac events. Rates of death from any cause were nearly identical. Crucially, in subgroup analyses, the effects did not vary according to vitamin D levels at baseline.

The D-Health investigators randomly assigned more than 21,000 adults to vitamin D or placebo and after 5.7 years of follow-up reported no differences in the primary endpoint of overall mortality. There also were no differences in cardiovascular disease mortality.

Then you have the Mendelian randomized studies, which some have called nature’s RCT. These studies take advantage of the fact that some people are born with gene variations that predispose to low vitamin D levels. More than 60 Mendelian randomization studies have evaluated the consequences of lifelong genetically lowered vitamin D levels on various outcomes; most of these have found null effects.

Then there are the meta-analyses and systematic reviews. I loved the conclusion of this review of systematic reviews from the BMJ (emphasis mine):

“Despite a few hundred systematic reviews and meta-analyses, highly convincing evidence of a clear role of vitamin D does not exist for any outcome, but associations with a selection of outcomes are probable.”

The failure to persuade

My original plan was to emphasize the power of the RCT. Despite strong associations of low vitamin D levels with poor outcomes, the trials show no benefit to treatment. This strongly suggests (or nearly proves) that low vitamin D levels are akin to premature ventricular complexes after myocardial infarction: a marker for risk but not a target for therapy.

But I now see the more important issue as why scientists, funders, clinicians, and patients are not persuaded by clear evidence. Every day in clinic I see patients on vitamin D supplements; the journals keep publishing vitamin D studies. The proponents of vitamin D remain positive. And lately there is outsized attention and hope that vitamin D will mitigate SARS-CoV2 infection – based only on observational data.

You might argue against this point by saying vitamin D is natural and relatively innocuous, so who cares?

I offer three rebuttals to that point: Opportunity costs, distraction, and the insidious danger of poor critical appraisal skills. If you are burning money on vitamin D research, there is less available to study other important issues. If a patient is distracted by low vitamin D levels, she may pay less attention to her high body mass index or hypertension. And on the matter of critical appraisal, trust in medicine requires clinicians to be competent in critical appraisal. And these days, what could be more important than trust in medical professionals?

One major reason for the failure of persuasion of evidence is spin – or language that distracts from the primary endpoint. Here are two (of many) examples:

A meta-analysis of 50 vitamin D trials set out to study mortality. The authors found no significant difference in that primary endpoint. But the second sentence in their conclusion was that vitamin D supplements reduced the risk for cancer deaths by 15%. That’s a secondary endpoint in a study with nonsignificance in the primary endpoint. That is spin. This meta-analysis was completed before the Australian D-Health trial found that cancer deaths were 15% higher in the vitamin D arm, a difference that did not reach statistical significance.

The following example is worse: The authors of the VITAL trial, which found that vitamin D supplements had no effect on the primary endpoint of invasive cancer or cardiovascular disease, published a secondary analysis of the trial looking at a different endpoint: A composite incidence of metastatic and fatal invasive total cancer. They reported a 0.4% lower rate for the vitamin D group, a difference that barely made statistical significance at a P value of .04.

But everyone knows the dangers of reanalyzing data with a new endpoint after you have seen the data. What’s more, even if this were a reasonable post hoc analysis, the results are neither clinically meaningful nor statistically robust. Yet the fatally flawed paper has been viewed 60,000 times and picked up by 48 news outlets.

Another way to distract from nonsignificant primary outcomes is to nitpick the trials. The vitamin D dose wasn’t high enough, for instance. This might persuade me if there were one or two vitamin D trials, but there are hundreds of trials and meta-analyses, and their results are consistently null.

Conclusion: No, it is not hopeless

A nihilist would argue that fighting spin is futile. They would say you can’t fight incentives and business models. The incentive structure to publish is strong, and the journals and media know vitamin D studies garner attention – which is their currency.

I am not a nihilist and believe strongly that we must continue to teach critical appraisal and numerical literacy.

In fact, I would speculate that decades of poor critical appraisal by the medical profession have fostered outsized hope and created erroneous norms.

Imagine a counter-factual world in which clinicians have taught society that the human body is unlike an engine that can be repaired by fixing one part (i.e., the vitamin D level), that magic bullets (insulin) are rare, that most treatments fail, or that you can’t rely on association studies to prove efficacy.

In this world, people would be immune from spin and hype.

The norm would be that pills, supplements, and procedures are not what delivers good health. What delivers health is an amalgam of good luck, healthy habits, and lots of time spent outside playing in the sun.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He espouses a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vitamin D story exudes teaching points: It offers a master class in critical appraisal, connecting the concepts of biologic plausibility, flawed surrogate markers, confounded observational studies, and slews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing no benefits on health outcomes.

Yet despite the utter lack of benefit seen in trials, the hype continues. And the pandemic has only enhanced this hype as an onslaught of papers have reported the association of low vitamin D levels and COVID-19 disease.

My questions are simple: Why doesn’t the evidence persuade people? How many nonsignificant trials do we need before researchers stop studying vitamin D, doctors stop (routinely) measuring levels, and patients stop wasting money on the unhelpful supplement? What are the implications for this lack of persuasion?

Before exploring these questions, I want to set out that symptomatic vitamin deficiencies of any sort ought to be corrected.

Biologic plausibility and the pull of observational studies

It has long been known that vitamin D is crucial for bone health and that it can be produced in the skin with sun exposure. In the last decade, however, experts note that nearly every tissue and cell in our body has a vitamin D receptor. It then follows that if this many cells in the body can activate vitamin D, it must be vital for cardiovascular health, immune function, cancer prevention: basically, everything health related.

Oodles of observational studies have found that low serum levels of vitamin D correlate with higher mortality from all causes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and now even COVID-19. Yet no matter the amount of statistical adjustment in these studies, we cannot know whether these associations are due to true causality.

The major issue is confounding: That is, people with low vitamin D levels have other conditions or diseases that lead to higher rates of ill health. Consider a patient with obesity, arthritis, and cognitive decline; this person is unlikely to do much exercise in the sun and may have low vitamin D levels. The low vitamin D level is simply a marker of overall poor health.

The randomized controlled trials tell a clear story

There are hundreds of vitamin D RCTs. The results simplify into one sentence: Vitamin D supplements do not improve health outcomes.

Here is a short summary of some recent studies.

VITAL, a massive (N > 25,000) RCT with 5 years of follow-up, compared vitamin D supplements to placebo and found no differences in the primary endpoints of cancer or cardiac events. Rates of death from any cause were nearly identical. Crucially, in subgroup analyses, the effects did not vary according to vitamin D levels at baseline.

The D-Health investigators randomly assigned more than 21,000 adults to vitamin D or placebo and after 5.7 years of follow-up reported no differences in the primary endpoint of overall mortality. There also were no differences in cardiovascular disease mortality.

Then you have the Mendelian randomized studies, which some have called nature’s RCT. These studies take advantage of the fact that some people are born with gene variations that predispose to low vitamin D levels. More than 60 Mendelian randomization studies have evaluated the consequences of lifelong genetically lowered vitamin D levels on various outcomes; most of these have found null effects.

Then there are the meta-analyses and systematic reviews. I loved the conclusion of this review of systematic reviews from the BMJ (emphasis mine):

“Despite a few hundred systematic reviews and meta-analyses, highly convincing evidence of a clear role of vitamin D does not exist for any outcome, but associations with a selection of outcomes are probable.”

The failure to persuade

My original plan was to emphasize the power of the RCT. Despite strong associations of low vitamin D levels with poor outcomes, the trials show no benefit to treatment. This strongly suggests (or nearly proves) that low vitamin D levels are akin to premature ventricular complexes after myocardial infarction: a marker for risk but not a target for therapy.

But I now see the more important issue as why scientists, funders, clinicians, and patients are not persuaded by clear evidence. Every day in clinic I see patients on vitamin D supplements; the journals keep publishing vitamin D studies. The proponents of vitamin D remain positive. And lately there is outsized attention and hope that vitamin D will mitigate SARS-CoV2 infection – based only on observational data.

You might argue against this point by saying vitamin D is natural and relatively innocuous, so who cares?

I offer three rebuttals to that point: Opportunity costs, distraction, and the insidious danger of poor critical appraisal skills. If you are burning money on vitamin D research, there is less available to study other important issues. If a patient is distracted by low vitamin D levels, she may pay less attention to her high body mass index or hypertension. And on the matter of critical appraisal, trust in medicine requires clinicians to be competent in critical appraisal. And these days, what could be more important than trust in medical professionals?

One major reason for the failure of persuasion of evidence is spin – or language that distracts from the primary endpoint. Here are two (of many) examples:

A meta-analysis of 50 vitamin D trials set out to study mortality. The authors found no significant difference in that primary endpoint. But the second sentence in their conclusion was that vitamin D supplements reduced the risk for cancer deaths by 15%. That’s a secondary endpoint in a study with nonsignificance in the primary endpoint. That is spin. This meta-analysis was completed before the Australian D-Health trial found that cancer deaths were 15% higher in the vitamin D arm, a difference that did not reach statistical significance.

The following example is worse: The authors of the VITAL trial, which found that vitamin D supplements had no effect on the primary endpoint of invasive cancer or cardiovascular disease, published a secondary analysis of the trial looking at a different endpoint: A composite incidence of metastatic and fatal invasive total cancer. They reported a 0.4% lower rate for the vitamin D group, a difference that barely made statistical significance at a P value of .04.

But everyone knows the dangers of reanalyzing data with a new endpoint after you have seen the data. What’s more, even if this were a reasonable post hoc analysis, the results are neither clinically meaningful nor statistically robust. Yet the fatally flawed paper has been viewed 60,000 times and picked up by 48 news outlets.

Another way to distract from nonsignificant primary outcomes is to nitpick the trials. The vitamin D dose wasn’t high enough, for instance. This might persuade me if there were one or two vitamin D trials, but there are hundreds of trials and meta-analyses, and their results are consistently null.

Conclusion: No, it is not hopeless

A nihilist would argue that fighting spin is futile. They would say you can’t fight incentives and business models. The incentive structure to publish is strong, and the journals and media know vitamin D studies garner attention – which is their currency.

I am not a nihilist and believe strongly that we must continue to teach critical appraisal and numerical literacy.

In fact, I would speculate that decades of poor critical appraisal by the medical profession have fostered outsized hope and created erroneous norms.

Imagine a counter-factual world in which clinicians have taught society that the human body is unlike an engine that can be repaired by fixing one part (i.e., the vitamin D level), that magic bullets (insulin) are rare, that most treatments fail, or that you can’t rely on association studies to prove efficacy.

In this world, people would be immune from spin and hype.

The norm would be that pills, supplements, and procedures are not what delivers good health. What delivers health is an amalgam of good luck, healthy habits, and lots of time spent outside playing in the sun.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He espouses a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vitamin D story exudes teaching points: It offers a master class in critical appraisal, connecting the concepts of biologic plausibility, flawed surrogate markers, confounded observational studies, and slews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing no benefits on health outcomes.

Yet despite the utter lack of benefit seen in trials, the hype continues. And the pandemic has only enhanced this hype as an onslaught of papers have reported the association of low vitamin D levels and COVID-19 disease.

My questions are simple: Why doesn’t the evidence persuade people? How many nonsignificant trials do we need before researchers stop studying vitamin D, doctors stop (routinely) measuring levels, and patients stop wasting money on the unhelpful supplement? What are the implications for this lack of persuasion?

Before exploring these questions, I want to set out that symptomatic vitamin deficiencies of any sort ought to be corrected.

Biologic plausibility and the pull of observational studies

It has long been known that vitamin D is crucial for bone health and that it can be produced in the skin with sun exposure. In the last decade, however, experts note that nearly every tissue and cell in our body has a vitamin D receptor. It then follows that if this many cells in the body can activate vitamin D, it must be vital for cardiovascular health, immune function, cancer prevention: basically, everything health related.

Oodles of observational studies have found that low serum levels of vitamin D correlate with higher mortality from all causes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and now even COVID-19. Yet no matter the amount of statistical adjustment in these studies, we cannot know whether these associations are due to true causality.

The major issue is confounding: That is, people with low vitamin D levels have other conditions or diseases that lead to higher rates of ill health. Consider a patient with obesity, arthritis, and cognitive decline; this person is unlikely to do much exercise in the sun and may have low vitamin D levels. The low vitamin D level is simply a marker of overall poor health.

The randomized controlled trials tell a clear story

There are hundreds of vitamin D RCTs. The results simplify into one sentence: Vitamin D supplements do not improve health outcomes.

Here is a short summary of some recent studies.

VITAL, a massive (N > 25,000) RCT with 5 years of follow-up, compared vitamin D supplements to placebo and found no differences in the primary endpoints of cancer or cardiac events. Rates of death from any cause were nearly identical. Crucially, in subgroup analyses, the effects did not vary according to vitamin D levels at baseline.

The D-Health investigators randomly assigned more than 21,000 adults to vitamin D or placebo and after 5.7 years of follow-up reported no differences in the primary endpoint of overall mortality. There also were no differences in cardiovascular disease mortality.

Then you have the Mendelian randomized studies, which some have called nature’s RCT. These studies take advantage of the fact that some people are born with gene variations that predispose to low vitamin D levels. More than 60 Mendelian randomization studies have evaluated the consequences of lifelong genetically lowered vitamin D levels on various outcomes; most of these have found null effects.

Then there are the meta-analyses and systematic reviews. I loved the conclusion of this review of systematic reviews from the BMJ (emphasis mine):

“Despite a few hundred systematic reviews and meta-analyses, highly convincing evidence of a clear role of vitamin D does not exist for any outcome, but associations with a selection of outcomes are probable.”

The failure to persuade

My original plan was to emphasize the power of the RCT. Despite strong associations of low vitamin D levels with poor outcomes, the trials show no benefit to treatment. This strongly suggests (or nearly proves) that low vitamin D levels are akin to premature ventricular complexes after myocardial infarction: a marker for risk but not a target for therapy.

But I now see the more important issue as why scientists, funders, clinicians, and patients are not persuaded by clear evidence. Every day in clinic I see patients on vitamin D supplements; the journals keep publishing vitamin D studies. The proponents of vitamin D remain positive. And lately there is outsized attention and hope that vitamin D will mitigate SARS-CoV2 infection – based only on observational data.

You might argue against this point by saying vitamin D is natural and relatively innocuous, so who cares?

I offer three rebuttals to that point: Opportunity costs, distraction, and the insidious danger of poor critical appraisal skills. If you are burning money on vitamin D research, there is less available to study other important issues. If a patient is distracted by low vitamin D levels, she may pay less attention to her high body mass index or hypertension. And on the matter of critical appraisal, trust in medicine requires clinicians to be competent in critical appraisal. And these days, what could be more important than trust in medical professionals?

One major reason for the failure of persuasion of evidence is spin – or language that distracts from the primary endpoint. Here are two (of many) examples:

A meta-analysis of 50 vitamin D trials set out to study mortality. The authors found no significant difference in that primary endpoint. But the second sentence in their conclusion was that vitamin D supplements reduced the risk for cancer deaths by 15%. That’s a secondary endpoint in a study with nonsignificance in the primary endpoint. That is spin. This meta-analysis was completed before the Australian D-Health trial found that cancer deaths were 15% higher in the vitamin D arm, a difference that did not reach statistical significance.

The following example is worse: The authors of the VITAL trial, which found that vitamin D supplements had no effect on the primary endpoint of invasive cancer or cardiovascular disease, published a secondary analysis of the trial looking at a different endpoint: A composite incidence of metastatic and fatal invasive total cancer. They reported a 0.4% lower rate for the vitamin D group, a difference that barely made statistical significance at a P value of .04.

But everyone knows the dangers of reanalyzing data with a new endpoint after you have seen the data. What’s more, even if this were a reasonable post hoc analysis, the results are neither clinically meaningful nor statistically robust. Yet the fatally flawed paper has been viewed 60,000 times and picked up by 48 news outlets.

Another way to distract from nonsignificant primary outcomes is to nitpick the trials. The vitamin D dose wasn’t high enough, for instance. This might persuade me if there were one or two vitamin D trials, but there are hundreds of trials and meta-analyses, and their results are consistently null.

Conclusion: No, it is not hopeless

A nihilist would argue that fighting spin is futile. They would say you can’t fight incentives and business models. The incentive structure to publish is strong, and the journals and media know vitamin D studies garner attention – which is their currency.

I am not a nihilist and believe strongly that we must continue to teach critical appraisal and numerical literacy.

In fact, I would speculate that decades of poor critical appraisal by the medical profession have fostered outsized hope and created erroneous norms.

Imagine a counter-factual world in which clinicians have taught society that the human body is unlike an engine that can be repaired by fixing one part (i.e., the vitamin D level), that magic bullets (insulin) are rare, that most treatments fail, or that you can’t rely on association studies to prove efficacy.

In this world, people would be immune from spin and hype.

The norm would be that pills, supplements, and procedures are not what delivers good health. What delivers health is an amalgam of good luck, healthy habits, and lots of time spent outside playing in the sun.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He espouses a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC preparing to update mask guidance

, CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, said on Feb. 16.

“As we consider future metrics, which will be updated soon, we recognize the importance of not just cases … but critically, medically severe disease that leads to hospitalizations,” Dr. Walensky said at a White House news briefing. “We must consider hospital capacity as an additional important barometer.”

She later added, “We are looking at an overview of much of our guidance, and masking in all settings will be a part of that.”

Coronavirus cases continue to drop nationwide. This week’s 7-day daily average of cases is 147,000, a decrease of 40%. Hospitalizations have dropped 28% to 9,500, and daily deaths are 2,200, a decrease of 9%.

“Omicron cases are declining, and we are all cautiously optimistic about the trajectory we’re on,” Dr. Walensky said. “Things are moving in the right direction, but we want to remain vigilant to do all we can so this trajectory continues.”

Dr. Walensky said public masking remains especially important if someone is symptomatic or not feeling well, or if there has been a COVID-19 exposure. Those who are within 10 days of being diagnosed with the virus should also remain masked in public.

“We all share the same goal: to get to a point where COVID-19 is no longer disrupting our daily lives. A time when it won’t be a constant crisis,” Dr. Walensky said. “Moving from this pandemic will be a process led by science and epidemiological trends, and one that relies on the powerful tools we already have.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, said on Feb. 16.

“As we consider future metrics, which will be updated soon, we recognize the importance of not just cases … but critically, medically severe disease that leads to hospitalizations,” Dr. Walensky said at a White House news briefing. “We must consider hospital capacity as an additional important barometer.”

She later added, “We are looking at an overview of much of our guidance, and masking in all settings will be a part of that.”

Coronavirus cases continue to drop nationwide. This week’s 7-day daily average of cases is 147,000, a decrease of 40%. Hospitalizations have dropped 28% to 9,500, and daily deaths are 2,200, a decrease of 9%.

“Omicron cases are declining, and we are all cautiously optimistic about the trajectory we’re on,” Dr. Walensky said. “Things are moving in the right direction, but we want to remain vigilant to do all we can so this trajectory continues.”

Dr. Walensky said public masking remains especially important if someone is symptomatic or not feeling well, or if there has been a COVID-19 exposure. Those who are within 10 days of being diagnosed with the virus should also remain masked in public.

“We all share the same goal: to get to a point where COVID-19 is no longer disrupting our daily lives. A time when it won’t be a constant crisis,” Dr. Walensky said. “Moving from this pandemic will be a process led by science and epidemiological trends, and one that relies on the powerful tools we already have.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, said on Feb. 16.

“As we consider future metrics, which will be updated soon, we recognize the importance of not just cases … but critically, medically severe disease that leads to hospitalizations,” Dr. Walensky said at a White House news briefing. “We must consider hospital capacity as an additional important barometer.”

She later added, “We are looking at an overview of much of our guidance, and masking in all settings will be a part of that.”

Coronavirus cases continue to drop nationwide. This week’s 7-day daily average of cases is 147,000, a decrease of 40%. Hospitalizations have dropped 28% to 9,500, and daily deaths are 2,200, a decrease of 9%.

“Omicron cases are declining, and we are all cautiously optimistic about the trajectory we’re on,” Dr. Walensky said. “Things are moving in the right direction, but we want to remain vigilant to do all we can so this trajectory continues.”

Dr. Walensky said public masking remains especially important if someone is symptomatic or not feeling well, or if there has been a COVID-19 exposure. Those who are within 10 days of being diagnosed with the virus should also remain masked in public.

“We all share the same goal: to get to a point where COVID-19 is no longer disrupting our daily lives. A time when it won’t be a constant crisis,” Dr. Walensky said. “Moving from this pandemic will be a process led by science and epidemiological trends, and one that relies on the powerful tools we already have.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Tiny hitchhikers like to ride in the trunk

Junk (germs) in the trunk

It’s been a long drive, and you’ve got a long way to go. You pull into a rest stop to use the bathroom and get some food. Quick, which order do you do those things in?

If you’re not a crazy person, you’d use the bathroom and then get your food. Who would bring food into a dirty bathroom? That’s kind of gross. Most people would take care of business, grab food, then get back in the car, eating along the way. Unfortunately, if you’re searching for a sanitary eating environment, your car may not actually be much better than that bathroom, according to new research from Aston University in Birmingham, England.

Let’s start off with the good news. The steering wheels of the five used cars that were swabbed for bacteria were pretty clean. Definitely cleaner than either of the toilet seats analyzed, likely thanks to increased usage of sanitizer, courtesy of the current pandemic. It’s easy to wipe down the steering wheel. Things break down, though, once we look elsewhere. The interiors of the five cars all contained just as much, if not more, bacteria than the toilet seats, with fecal matter commonly appearing on the driver’s seat.

The car interiors were less than sanitary, but they paled in comparison with the real winner here: the trunk. In each of the five cars, bacteria levels there far exceeded those in the toilets, and included everyone’s favorites – Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

So, snacking on a bag of chips as you drive along is probably okay, but the food that popped out of its bag and spent the last 5 minutes rolling around the back? Perhaps less okay. You may want to wash it. Or burn it. Or torch the entire car for good measure like we’re about to do. Next time we’ll buy a car without poop in it.

Shut the lid when you flush

Maybe you’ve never thought about this, but it’s actually extremely important to shut the toilet lid when you flush. Just think of all those germs flying around from the force of the flush. Is your toothbrush anywhere near the toilet? Ew. Those pesky little bacteria and viruses are everywhere, and we know we can’t really escape them, but we should really do our best once we’re made aware of where to find them.

It seems like a no-brainer these days since we’ve all been really focused on cleanliness during the pandemic, but according to a poll in the United Kingdom, 55% of the 2,000 participants said they don’t put the lid down while flushing.

The OnePoll survey commissioned by Harpic, a company that makes toilet-cleaning products, also advised that toilet water isn’t even completely clean after flushed several times and can still be contaminated with many germs. Company researchers took specialized pictures of flushing toilets and they looked like tiny little Fourth of July fireworks shows, minus the sparklers. The pictures proved that droplets can go all over the place, including on bathroom users.

“There has never been a more important time to take extra care around our homes, although the risks associated with germ spread in unhygienic bathrooms are high, the solution to keeping them clean is simple,” a Harpic researcher said. Since other studies have shown that coronavirus can be found in feces, it’s become increasingly important to keep ourselves and others safe. Fireworks are pretty, but not when they come out of your toilet.

The latest in MRI fashion

Do you see that photo just below? Looks like something you could buy at the Lego store, right? Well, it’s not. Nor is it the proverbial thinking cap come to life.

(Did someone just say “come to life”? That reminds us of our favorite scene from Frosty the Snowman.)

Anywaaay, about the photo. That funny-looking chapeau is what we in the science business call a metamaterial.

Nope, metamaterials have nothing to do with Facebook parent company Meta. We checked. According to a statement from Boston University, they are engineered structures “created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature.”

Superpowers, eh? Who doesn’t want superpowers? Even if they come with a funny hat.

The unit cells, known as resonators, are just plastic tubes wrapped in copper wiring, but when they are grouped in an array and precisely arranged into a helmet, they can channel the magnetic field of the MRI machine during a scan. In theory, that would create “crisper images that can be captured at twice the normal speed,” Xin Zhang, PhD, and her team at BU’s Photonics Center explained in the university statement.

In the future, the metamaterial device could “be used in conjunction with cheaper low-field MRI machines to make the technology more widely available, particularly in the developing world,” they suggested. Or, like so many other superpowers, it could fall into the wrong hands. Like those of Lex Luthor. Or Mark Zuckerberg. Or Frosty the Snowman.

The highway of the mind

How fast can you think on your feet? Well, according to a recently published study, it could be a legitimate measure of intelligence. Here’s the science.

Researchers from the University of Würzburg in Germany and Indiana University have suggested that a person’s intelligence score measures the ability, based on certain neuronal networks and their communication structures, to switch between resting state and different task states.

The investigators set up a study to observe almost 800 people while they completed seven tasks. By monitoring brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging, the teams found that subjects who had higher intelligence scores required “less adjustment when switching between different cognitive states,” they said in a separate statement.

It comes down to the network architecture of their brains.

Kirsten Hilger, PhD, head of the German group, described it in terms of highways. The resting state of the brain is normal traffic. It’s always moving. Holiday traffic is the task. The ability to handle the increased flow of commuters is a function of the highway infrastructure. The better the infrastructure, the higher the intelligence.

So the next time you’re stuck in traffic, think how efficient your brain would be with such a task. The quicker, the better.

Junk (germs) in the trunk

It’s been a long drive, and you’ve got a long way to go. You pull into a rest stop to use the bathroom and get some food. Quick, which order do you do those things in?

If you’re not a crazy person, you’d use the bathroom and then get your food. Who would bring food into a dirty bathroom? That’s kind of gross. Most people would take care of business, grab food, then get back in the car, eating along the way. Unfortunately, if you’re searching for a sanitary eating environment, your car may not actually be much better than that bathroom, according to new research from Aston University in Birmingham, England.

Let’s start off with the good news. The steering wheels of the five used cars that were swabbed for bacteria were pretty clean. Definitely cleaner than either of the toilet seats analyzed, likely thanks to increased usage of sanitizer, courtesy of the current pandemic. It’s easy to wipe down the steering wheel. Things break down, though, once we look elsewhere. The interiors of the five cars all contained just as much, if not more, bacteria than the toilet seats, with fecal matter commonly appearing on the driver’s seat.

The car interiors were less than sanitary, but they paled in comparison with the real winner here: the trunk. In each of the five cars, bacteria levels there far exceeded those in the toilets, and included everyone’s favorites – Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

So, snacking on a bag of chips as you drive along is probably okay, but the food that popped out of its bag and spent the last 5 minutes rolling around the back? Perhaps less okay. You may want to wash it. Or burn it. Or torch the entire car for good measure like we’re about to do. Next time we’ll buy a car without poop in it.

Shut the lid when you flush

Maybe you’ve never thought about this, but it’s actually extremely important to shut the toilet lid when you flush. Just think of all those germs flying around from the force of the flush. Is your toothbrush anywhere near the toilet? Ew. Those pesky little bacteria and viruses are everywhere, and we know we can’t really escape them, but we should really do our best once we’re made aware of where to find them.

It seems like a no-brainer these days since we’ve all been really focused on cleanliness during the pandemic, but according to a poll in the United Kingdom, 55% of the 2,000 participants said they don’t put the lid down while flushing.

The OnePoll survey commissioned by Harpic, a company that makes toilet-cleaning products, also advised that toilet water isn’t even completely clean after flushed several times and can still be contaminated with many germs. Company researchers took specialized pictures of flushing toilets and they looked like tiny little Fourth of July fireworks shows, minus the sparklers. The pictures proved that droplets can go all over the place, including on bathroom users.

“There has never been a more important time to take extra care around our homes, although the risks associated with germ spread in unhygienic bathrooms are high, the solution to keeping them clean is simple,” a Harpic researcher said. Since other studies have shown that coronavirus can be found in feces, it’s become increasingly important to keep ourselves and others safe. Fireworks are pretty, but not when they come out of your toilet.

The latest in MRI fashion

Do you see that photo just below? Looks like something you could buy at the Lego store, right? Well, it’s not. Nor is it the proverbial thinking cap come to life.

(Did someone just say “come to life”? That reminds us of our favorite scene from Frosty the Snowman.)

Anywaaay, about the photo. That funny-looking chapeau is what we in the science business call a metamaterial.

Nope, metamaterials have nothing to do with Facebook parent company Meta. We checked. According to a statement from Boston University, they are engineered structures “created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature.”

Superpowers, eh? Who doesn’t want superpowers? Even if they come with a funny hat.

The unit cells, known as resonators, are just plastic tubes wrapped in copper wiring, but when they are grouped in an array and precisely arranged into a helmet, they can channel the magnetic field of the MRI machine during a scan. In theory, that would create “crisper images that can be captured at twice the normal speed,” Xin Zhang, PhD, and her team at BU’s Photonics Center explained in the university statement.

In the future, the metamaterial device could “be used in conjunction with cheaper low-field MRI machines to make the technology more widely available, particularly in the developing world,” they suggested. Or, like so many other superpowers, it could fall into the wrong hands. Like those of Lex Luthor. Or Mark Zuckerberg. Or Frosty the Snowman.

The highway of the mind

How fast can you think on your feet? Well, according to a recently published study, it could be a legitimate measure of intelligence. Here’s the science.

Researchers from the University of Würzburg in Germany and Indiana University have suggested that a person’s intelligence score measures the ability, based on certain neuronal networks and their communication structures, to switch between resting state and different task states.

The investigators set up a study to observe almost 800 people while they completed seven tasks. By monitoring brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging, the teams found that subjects who had higher intelligence scores required “less adjustment when switching between different cognitive states,” they said in a separate statement.

It comes down to the network architecture of their brains.

Kirsten Hilger, PhD, head of the German group, described it in terms of highways. The resting state of the brain is normal traffic. It’s always moving. Holiday traffic is the task. The ability to handle the increased flow of commuters is a function of the highway infrastructure. The better the infrastructure, the higher the intelligence.

So the next time you’re stuck in traffic, think how efficient your brain would be with such a task. The quicker, the better.

Junk (germs) in the trunk

It’s been a long drive, and you’ve got a long way to go. You pull into a rest stop to use the bathroom and get some food. Quick, which order do you do those things in?

If you’re not a crazy person, you’d use the bathroom and then get your food. Who would bring food into a dirty bathroom? That’s kind of gross. Most people would take care of business, grab food, then get back in the car, eating along the way. Unfortunately, if you’re searching for a sanitary eating environment, your car may not actually be much better than that bathroom, according to new research from Aston University in Birmingham, England.

Let’s start off with the good news. The steering wheels of the five used cars that were swabbed for bacteria were pretty clean. Definitely cleaner than either of the toilet seats analyzed, likely thanks to increased usage of sanitizer, courtesy of the current pandemic. It’s easy to wipe down the steering wheel. Things break down, though, once we look elsewhere. The interiors of the five cars all contained just as much, if not more, bacteria than the toilet seats, with fecal matter commonly appearing on the driver’s seat.

The car interiors were less than sanitary, but they paled in comparison with the real winner here: the trunk. In each of the five cars, bacteria levels there far exceeded those in the toilets, and included everyone’s favorites – Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

So, snacking on a bag of chips as you drive along is probably okay, but the food that popped out of its bag and spent the last 5 minutes rolling around the back? Perhaps less okay. You may want to wash it. Or burn it. Or torch the entire car for good measure like we’re about to do. Next time we’ll buy a car without poop in it.

Shut the lid when you flush

Maybe you’ve never thought about this, but it’s actually extremely important to shut the toilet lid when you flush. Just think of all those germs flying around from the force of the flush. Is your toothbrush anywhere near the toilet? Ew. Those pesky little bacteria and viruses are everywhere, and we know we can’t really escape them, but we should really do our best once we’re made aware of where to find them.

It seems like a no-brainer these days since we’ve all been really focused on cleanliness during the pandemic, but according to a poll in the United Kingdom, 55% of the 2,000 participants said they don’t put the lid down while flushing.

The OnePoll survey commissioned by Harpic, a company that makes toilet-cleaning products, also advised that toilet water isn’t even completely clean after flushed several times and can still be contaminated with many germs. Company researchers took specialized pictures of flushing toilets and they looked like tiny little Fourth of July fireworks shows, minus the sparklers. The pictures proved that droplets can go all over the place, including on bathroom users.

“There has never been a more important time to take extra care around our homes, although the risks associated with germ spread in unhygienic bathrooms are high, the solution to keeping them clean is simple,” a Harpic researcher said. Since other studies have shown that coronavirus can be found in feces, it’s become increasingly important to keep ourselves and others safe. Fireworks are pretty, but not when they come out of your toilet.

The latest in MRI fashion

Do you see that photo just below? Looks like something you could buy at the Lego store, right? Well, it’s not. Nor is it the proverbial thinking cap come to life.

(Did someone just say “come to life”? That reminds us of our favorite scene from Frosty the Snowman.)

Anywaaay, about the photo. That funny-looking chapeau is what we in the science business call a metamaterial.

Nope, metamaterials have nothing to do with Facebook parent company Meta. We checked. According to a statement from Boston University, they are engineered structures “created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature.”

Superpowers, eh? Who doesn’t want superpowers? Even if they come with a funny hat.

The unit cells, known as resonators, are just plastic tubes wrapped in copper wiring, but when they are grouped in an array and precisely arranged into a helmet, they can channel the magnetic field of the MRI machine during a scan. In theory, that would create “crisper images that can be captured at twice the normal speed,” Xin Zhang, PhD, and her team at BU’s Photonics Center explained in the university statement.

In the future, the metamaterial device could “be used in conjunction with cheaper low-field MRI machines to make the technology more widely available, particularly in the developing world,” they suggested. Or, like so many other superpowers, it could fall into the wrong hands. Like those of Lex Luthor. Or Mark Zuckerberg. Or Frosty the Snowman.

The highway of the mind

How fast can you think on your feet? Well, according to a recently published study, it could be a legitimate measure of intelligence. Here’s the science.

Researchers from the University of Würzburg in Germany and Indiana University have suggested that a person’s intelligence score measures the ability, based on certain neuronal networks and their communication structures, to switch between resting state and different task states.

The investigators set up a study to observe almost 800 people while they completed seven tasks. By monitoring brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging, the teams found that subjects who had higher intelligence scores required “less adjustment when switching between different cognitive states,” they said in a separate statement.

It comes down to the network architecture of their brains.

Kirsten Hilger, PhD, head of the German group, described it in terms of highways. The resting state of the brain is normal traffic. It’s always moving. Holiday traffic is the task. The ability to handle the increased flow of commuters is a function of the highway infrastructure. The better the infrastructure, the higher the intelligence.

So the next time you’re stuck in traffic, think how efficient your brain would be with such a task. The quicker, the better.

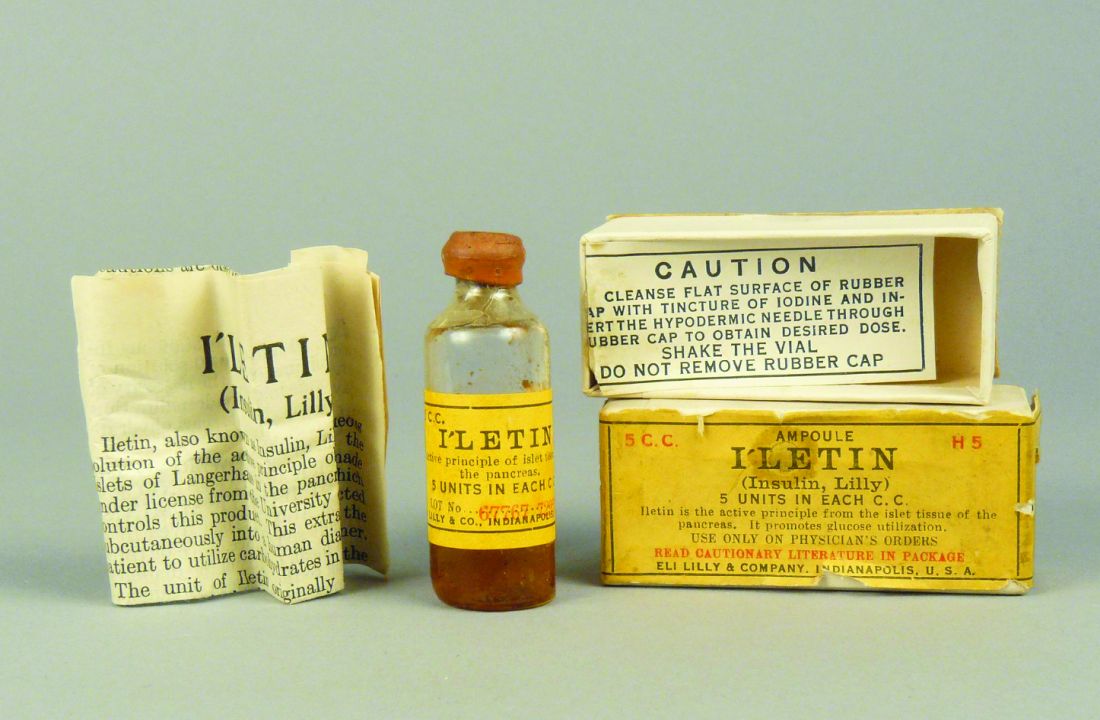

The battle of egos behind the life-saving discovery of insulin

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on Jan. 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks – months at best – Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery – and the Nobel Prize that went with it – lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, England, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Dr. Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At death’s door: Diabetes before the 1920s

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation – albeit a slightly slower death – to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the United States alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by this news organization.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8-12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the United States is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles by this news organization, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Ore.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Dr. Stephens stressed.

Antidiabetic effects of pancreatic extract limited

Back in 1869, Paul Langerhans, MD, discovered pancreatic islet cells, or islets of Langerhans, as a medical student. Researchers tried to produce extracts that lowered blood glucose but they were too toxic for patient use.

In 1908, as detailed in his recent book, Insulin – the Crooked Timber, Dr. Hall also refers to the fact that a German researcher, Georg Zuelzer, MD, demonstrated in six patients that pancreatic extracts could reduce urinary levels of glucose and ketones, and that in one case, the treatment woke the patient from a coma. Dr. Zuelzer had purified the extract with alcohol but patients still experienced convulsions and coma; in fact, they were experiencing hypoglycemic shock, but Dr. Zuelzer had not identified it as such.

“He thought his preparation was full of impurities – and that’s the irony. He had in his hands an insulin prep that was so clean and so potent that it sent the test animals into hypoglycemic shock,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

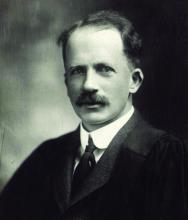

By 1921, two young researchers, Frederick G. Banting, MD, a practicing medical doctor in Toronto, together with a final year physiology student at the University of Toronto, Charles H. Best, MD, DSc, collaborated on the instruction of Dr. Best’s superior, John James Rickard Macleod, MBChB, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, to make pancreatic extracts, first from dogs and then from cattle.

Over the months prior to treating Thompson, working together in the laboratory, Dr. Banting and Dr. Best prepared the pancreatic extract from cattle and tested it on dogs with diabetes.

Then, in what amounted to a phase 1 trial of its day, with an “n of one,” a frail and close-to-death Thompson was given 15 cc of pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital in January 1922. His blood glucose level dropped by 25%, but unfortunately, his body still produced ketones, indicating the antidiabetic effect was limited. He also experienced an adverse reaction at the injection site with an accumulation of abscesses.

So despite success with isolating the extract and administering it to Thompson, the product remained tainted with impurities.

At this point, colleague James Collip, MD, PhD, came to the rescue. He used his skills as a biochemist to purify the pancreatic extract enough to eliminate impurities.

When Thompson was treated 2 weeks later with the purified extract, he experienced a more positive outcome. Gone was the injection site reaction, gone were the high blood glucose levels, and Thompson “became brighter, more active, looked better, and said he felt stronger,” according to a publication describing the treatment.

Dr. Collip also determined that by over-purifying the product, the animals he experimented on could overreact and experience convulsions, coma, and death due to hypoglycemia from too much insulin.

Fighting talk

Recalling an excerpt from Dr. Banting’s diary, Dr. Hall said that Dr. Banting had a mercurial temper and testified to his loss of patience with Dr. Collip when the chemist refused to share his formula of purification. His diary reads: “I grabbed him in one hand by the overcoat ... and almost lifting him I sat him down hard on the chair ... I remember telling him that it was a good job he was so much smaller – otherwise I would ‘knock hell out of him.’ ”

According to Dr. Hall, in 1923, when Dr. Banting and Dr. Macleod were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Dr. Best resented being excluded, and despite Dr. Banting’s sharing half his prize money with Dr. Best, animosity prevailed.

At one point, before leaving on a plane for a wartime mission to the United Kingdom, Dr. Banting noted that if he didn’t make it back alive, “and they give my [professorial] chair to that son-of-a-bitch Best, I’ll never rest in my grave.” In a cruel twist of fate, Dr. Banting’s plane crashed and all aboard died.

The Nobel Prize had also been a source of rivalry between Dr. Banting and his boss, Dr. Macleod. In late 1921, while presenting the findings from animal models at the American Physiological Society conference, Dr. Banting’s nerves got the better of him and Dr. Macleod took over at the podium to finish the talk. Dr. Banting perceived this as his boss stealing the limelight.

Only a few months later, at the Association of American Physicians annual conference, Dr. Macleod played to an audience for a second time by making the first formal announcement of the discovery to the scientific community. Notably, Dr. Banting was absent.

The Nobel Prize or a poisoned chalice?

Awarded annually for physics, chemistry, medicine/physiology, literature, peace, and economics, Nobel Prizes are usually considered the holy grail of achievement. In 1895, funds for the prizes were bequeathed by Alfred Nobel in his last will and testament, with each prize worth around $40,000 at the time (approximately $1,000,000 in today’s value).

Writing in 2001 in the journal Diabetes Voice, Professor Sir George Alberti, DPhil, BM BCh, former president of the UK Royal College of Physicians, summarized the burden that accompanies the Nobel Prize: “I personally believe that such prizes and awards do more harm than good and should be abolished. Many a scientist has gone to their grave feeling deeply aggrieved because they were not awarded a Nobel Prize.”

Such high stakes surround the prize that, in the case of insulin, the course of its discovery meant courtesies and truth were swept aside in hot pursuit of fame. After Dr. Macleod died in 1935 and Dr. Banting died in 1941, Dr. Best took the opportunity to try to revise history. There was the small obstacle of Dr. Collip, but Dr. Best managed to play down Dr. Collip’s contribution by focusing on the eureka moment as being the first insulin dose administered, despite the fact that a more complete recovery without side effects was later achieved only with Dr. Collip’s help.

Despite exclusion from the Nobel Prize, Dr. Best nevertheless became recognized as the “go-to-guy” for the discovery of insulin, said Dr. Hall. When Dr. Best spoke about the discovery of insulin at the New York Diabetes Association meeting in 1946, he was introduced as a speaker whose reputation was already so great that he did “not require much of an introduction.”

“And when a new research institute was opened in Toronto in 1953, it was named in his honor. The opening address, by Sir Henry Dale of the UK Medical Research Council, sang Best’s praises to the rafters, much to the disgruntlement of Best’s former colleague, James Collip, who was sitting in the audience,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

Both Dr. Hall and Dr. Stephens live with type 1 diabetes and have benefited from the efforts of Dr. Banting, Dr. Best, Dr. Collip, Dr. Zuelzer, and Dr. Macleod.

“The discovery of insulin was a miracle, it has allowed people to survive,” said Dr. Stephens. “Few medicines can reverse a death sentence like insulin can. It’s easy to forget how it was when insulin wasn’t there – and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Dr. Hall reflects that scientific progress and discovery are often portrayed as being the result of towering geniuses standing on each other’s shoulders.

“But I think that when German philosopher Immanuel Kant remarked that ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing can ever be made,’ he offered us a much more accurate picture of how science works. And I think that there’s perhaps no more powerful example of this than the story of insulin,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on Jan. 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks – months at best – Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery – and the Nobel Prize that went with it – lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, England, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Dr. Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At death’s door: Diabetes before the 1920s

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation – albeit a slightly slower death – to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the United States alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by this news organization.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8-12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the United States is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles by this news organization, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Ore.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Dr. Stephens stressed.

Antidiabetic effects of pancreatic extract limited

Back in 1869, Paul Langerhans, MD, discovered pancreatic islet cells, or islets of Langerhans, as a medical student. Researchers tried to produce extracts that lowered blood glucose but they were too toxic for patient use.

In 1908, as detailed in his recent book, Insulin – the Crooked Timber, Dr. Hall also refers to the fact that a German researcher, Georg Zuelzer, MD, demonstrated in six patients that pancreatic extracts could reduce urinary levels of glucose and ketones, and that in one case, the treatment woke the patient from a coma. Dr. Zuelzer had purified the extract with alcohol but patients still experienced convulsions and coma; in fact, they were experiencing hypoglycemic shock, but Dr. Zuelzer had not identified it as such.

“He thought his preparation was full of impurities – and that’s the irony. He had in his hands an insulin prep that was so clean and so potent that it sent the test animals into hypoglycemic shock,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

By 1921, two young researchers, Frederick G. Banting, MD, a practicing medical doctor in Toronto, together with a final year physiology student at the University of Toronto, Charles H. Best, MD, DSc, collaborated on the instruction of Dr. Best’s superior, John James Rickard Macleod, MBChB, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, to make pancreatic extracts, first from dogs and then from cattle.

Over the months prior to treating Thompson, working together in the laboratory, Dr. Banting and Dr. Best prepared the pancreatic extract from cattle and tested it on dogs with diabetes.

Then, in what amounted to a phase 1 trial of its day, with an “n of one,” a frail and close-to-death Thompson was given 15 cc of pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital in January 1922. His blood glucose level dropped by 25%, but unfortunately, his body still produced ketones, indicating the antidiabetic effect was limited. He also experienced an adverse reaction at the injection site with an accumulation of abscesses.

So despite success with isolating the extract and administering it to Thompson, the product remained tainted with impurities.

At this point, colleague James Collip, MD, PhD, came to the rescue. He used his skills as a biochemist to purify the pancreatic extract enough to eliminate impurities.

When Thompson was treated 2 weeks later with the purified extract, he experienced a more positive outcome. Gone was the injection site reaction, gone were the high blood glucose levels, and Thompson “became brighter, more active, looked better, and said he felt stronger,” according to a publication describing the treatment.

Dr. Collip also determined that by over-purifying the product, the animals he experimented on could overreact and experience convulsions, coma, and death due to hypoglycemia from too much insulin.

Fighting talk

Recalling an excerpt from Dr. Banting’s diary, Dr. Hall said that Dr. Banting had a mercurial temper and testified to his loss of patience with Dr. Collip when the chemist refused to share his formula of purification. His diary reads: “I grabbed him in one hand by the overcoat ... and almost lifting him I sat him down hard on the chair ... I remember telling him that it was a good job he was so much smaller – otherwise I would ‘knock hell out of him.’ ”

According to Dr. Hall, in 1923, when Dr. Banting and Dr. Macleod were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Dr. Best resented being excluded, and despite Dr. Banting’s sharing half his prize money with Dr. Best, animosity prevailed.

At one point, before leaving on a plane for a wartime mission to the United Kingdom, Dr. Banting noted that if he didn’t make it back alive, “and they give my [professorial] chair to that son-of-a-bitch Best, I’ll never rest in my grave.” In a cruel twist of fate, Dr. Banting’s plane crashed and all aboard died.

The Nobel Prize had also been a source of rivalry between Dr. Banting and his boss, Dr. Macleod. In late 1921, while presenting the findings from animal models at the American Physiological Society conference, Dr. Banting’s nerves got the better of him and Dr. Macleod took over at the podium to finish the talk. Dr. Banting perceived this as his boss stealing the limelight.

Only a few months later, at the Association of American Physicians annual conference, Dr. Macleod played to an audience for a second time by making the first formal announcement of the discovery to the scientific community. Notably, Dr. Banting was absent.

The Nobel Prize or a poisoned chalice?

Awarded annually for physics, chemistry, medicine/physiology, literature, peace, and economics, Nobel Prizes are usually considered the holy grail of achievement. In 1895, funds for the prizes were bequeathed by Alfred Nobel in his last will and testament, with each prize worth around $40,000 at the time (approximately $1,000,000 in today’s value).

Writing in 2001 in the journal Diabetes Voice, Professor Sir George Alberti, DPhil, BM BCh, former president of the UK Royal College of Physicians, summarized the burden that accompanies the Nobel Prize: “I personally believe that such prizes and awards do more harm than good and should be abolished. Many a scientist has gone to their grave feeling deeply aggrieved because they were not awarded a Nobel Prize.”

Such high stakes surround the prize that, in the case of insulin, the course of its discovery meant courtesies and truth were swept aside in hot pursuit of fame. After Dr. Macleod died in 1935 and Dr. Banting died in 1941, Dr. Best took the opportunity to try to revise history. There was the small obstacle of Dr. Collip, but Dr. Best managed to play down Dr. Collip’s contribution by focusing on the eureka moment as being the first insulin dose administered, despite the fact that a more complete recovery without side effects was later achieved only with Dr. Collip’s help.

Despite exclusion from the Nobel Prize, Dr. Best nevertheless became recognized as the “go-to-guy” for the discovery of insulin, said Dr. Hall. When Dr. Best spoke about the discovery of insulin at the New York Diabetes Association meeting in 1946, he was introduced as a speaker whose reputation was already so great that he did “not require much of an introduction.”

“And when a new research institute was opened in Toronto in 1953, it was named in his honor. The opening address, by Sir Henry Dale of the UK Medical Research Council, sang Best’s praises to the rafters, much to the disgruntlement of Best’s former colleague, James Collip, who was sitting in the audience,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

Both Dr. Hall and Dr. Stephens live with type 1 diabetes and have benefited from the efforts of Dr. Banting, Dr. Best, Dr. Collip, Dr. Zuelzer, and Dr. Macleod.

“The discovery of insulin was a miracle, it has allowed people to survive,” said Dr. Stephens. “Few medicines can reverse a death sentence like insulin can. It’s easy to forget how it was when insulin wasn’t there – and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Dr. Hall reflects that scientific progress and discovery are often portrayed as being the result of towering geniuses standing on each other’s shoulders.

“But I think that when German philosopher Immanuel Kant remarked that ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing can ever be made,’ he offered us a much more accurate picture of how science works. And I think that there’s perhaps no more powerful example of this than the story of insulin,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on Jan. 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks – months at best – Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery – and the Nobel Prize that went with it – lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, England, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Dr. Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At death’s door: Diabetes before the 1920s

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation – albeit a slightly slower death – to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the United States alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by this news organization.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8-12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the United States is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles by this news organization, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Ore.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Dr. Stephens stressed.

Antidiabetic effects of pancreatic extract limited