User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Children & COVID: Rise in new cases slows

New cases of COVID-19 in children climbed for the seventh consecutive week, but the latest increase was the smallest of the seven, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Since the weekly total bottomed out at just under 26,000 in early April, the new-case count has risen by 28.0%, 11.8%, 43.5%, 17.4%, 50%, 14.6%, and 5.0%, based on data from the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is almost 13.4 million since the pandemic began, and those infected children represent 18.9% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said based on data from 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

That 18.9% is noteworthy because it marks the first decline in that particular measure since the AAP and CHA started keeping track in April of 2020. Children’s share of the overall COVID burden had been holding at 19.0% for 14 straight weeks, the AAP/CHA data show.

Regionally, new cases were up in the South and the West, where recent rising trends continued, and down in the Midwest and Northeast, where the recent rising trends were reversed for the first time. At the state/territory level, Puerto Rico had the largest percent increase over the last 2 weeks, followed by Maryland and Delaware, the organizations noted in their joint report.

Hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 have changed little in the last week, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting rates of 0.25 per 100,000 population on May 23 and 0.25 per 100,000 on May 29, the latest date available. There was, however, a move up to 0.26 per 100,000 from May 24 to May 28, and the CDC acknowledges a possible reporting delay over the most recent 7-day period.

Emergency department visits have dipped slightly in recent days, with children aged 0-11 years at a 7-day average of 2.0% of ED visits with diagnosed COVID on May 28, down from a 5-day stretch at 2.2% from May 19 to May 23. Children aged 12-15 years were at 1.8% on May 28, compared with 2.0% on May 23-24, and 15- to 17-year-olds were at 2.0% on May 28, down from the 2.1% reached over the previous 2 days, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

New cases of COVID-19 in children climbed for the seventh consecutive week, but the latest increase was the smallest of the seven, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Since the weekly total bottomed out at just under 26,000 in early April, the new-case count has risen by 28.0%, 11.8%, 43.5%, 17.4%, 50%, 14.6%, and 5.0%, based on data from the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is almost 13.4 million since the pandemic began, and those infected children represent 18.9% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said based on data from 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

That 18.9% is noteworthy because it marks the first decline in that particular measure since the AAP and CHA started keeping track in April of 2020. Children’s share of the overall COVID burden had been holding at 19.0% for 14 straight weeks, the AAP/CHA data show.

Regionally, new cases were up in the South and the West, where recent rising trends continued, and down in the Midwest and Northeast, where the recent rising trends were reversed for the first time. At the state/territory level, Puerto Rico had the largest percent increase over the last 2 weeks, followed by Maryland and Delaware, the organizations noted in their joint report.

Hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 have changed little in the last week, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting rates of 0.25 per 100,000 population on May 23 and 0.25 per 100,000 on May 29, the latest date available. There was, however, a move up to 0.26 per 100,000 from May 24 to May 28, and the CDC acknowledges a possible reporting delay over the most recent 7-day period.

Emergency department visits have dipped slightly in recent days, with children aged 0-11 years at a 7-day average of 2.0% of ED visits with diagnosed COVID on May 28, down from a 5-day stretch at 2.2% from May 19 to May 23. Children aged 12-15 years were at 1.8% on May 28, compared with 2.0% on May 23-24, and 15- to 17-year-olds were at 2.0% on May 28, down from the 2.1% reached over the previous 2 days, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

New cases of COVID-19 in children climbed for the seventh consecutive week, but the latest increase was the smallest of the seven, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Since the weekly total bottomed out at just under 26,000 in early April, the new-case count has risen by 28.0%, 11.8%, 43.5%, 17.4%, 50%, 14.6%, and 5.0%, based on data from the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is almost 13.4 million since the pandemic began, and those infected children represent 18.9% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said based on data from 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

That 18.9% is noteworthy because it marks the first decline in that particular measure since the AAP and CHA started keeping track in April of 2020. Children’s share of the overall COVID burden had been holding at 19.0% for 14 straight weeks, the AAP/CHA data show.

Regionally, new cases were up in the South and the West, where recent rising trends continued, and down in the Midwest and Northeast, where the recent rising trends were reversed for the first time. At the state/territory level, Puerto Rico had the largest percent increase over the last 2 weeks, followed by Maryland and Delaware, the organizations noted in their joint report.

Hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 have changed little in the last week, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting rates of 0.25 per 100,000 population on May 23 and 0.25 per 100,000 on May 29, the latest date available. There was, however, a move up to 0.26 per 100,000 from May 24 to May 28, and the CDC acknowledges a possible reporting delay over the most recent 7-day period.

Emergency department visits have dipped slightly in recent days, with children aged 0-11 years at a 7-day average of 2.0% of ED visits with diagnosed COVID on May 28, down from a 5-day stretch at 2.2% from May 19 to May 23. Children aged 12-15 years were at 1.8% on May 28, compared with 2.0% on May 23-24, and 15- to 17-year-olds were at 2.0% on May 28, down from the 2.1% reached over the previous 2 days, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

FDA withdraws lymphoma drug approval after investigation

Umbralisib had received accelerated approval in February 2021 to treat adults with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma following at least one prior therapy and those with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma who had received at least three prior therapies.

But safety concerns began to emerge in the phase 3 UNITY-CLL trial, which evaluated the drug in a related cancer type: chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Last February, the FDA said it was investigating a possible increased risk of death associated with umbralisib.

Five months later, the results are in.

“Updated findings from the UNITY-CLL clinical trial continued to show a possible increased risk of death in patients receiving Ukoniq. As a result, we determined the risks of treatment with Ukoniq outweigh its benefits,” the FDA wrote in a drug safety communication published June 1.

In April, the drug manufacturer, TG Therapeutics, announced it was voluntarily withdrawing umbralisib from the market for its approved uses in marginal zone lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.

The FDA’s safety notice includes instructions for physicians and patients. The FDA urges health care professionals to “stop prescribing Ukoniq and switch patients to alternative treatments” and to “inform patients currently taking Ukoniq of the increased risk of death seen in the clinical trial and advise them to stop taking the medicine.”

In special instances in which a patient may be benefiting from the drug, the company plans to make umbralisib available under expanded access.

The FDA also recommends that patients who discontinue taking the drug dispose of unused umbralisib using a drug take-back location, such as a pharmacy, or throwing it away in the household trash after placing it in a sealed bag mixed with dirt or cat litter and removing personal identification information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Umbralisib had received accelerated approval in February 2021 to treat adults with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma following at least one prior therapy and those with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma who had received at least three prior therapies.

But safety concerns began to emerge in the phase 3 UNITY-CLL trial, which evaluated the drug in a related cancer type: chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Last February, the FDA said it was investigating a possible increased risk of death associated with umbralisib.

Five months later, the results are in.

“Updated findings from the UNITY-CLL clinical trial continued to show a possible increased risk of death in patients receiving Ukoniq. As a result, we determined the risks of treatment with Ukoniq outweigh its benefits,” the FDA wrote in a drug safety communication published June 1.

In April, the drug manufacturer, TG Therapeutics, announced it was voluntarily withdrawing umbralisib from the market for its approved uses in marginal zone lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.

The FDA’s safety notice includes instructions for physicians and patients. The FDA urges health care professionals to “stop prescribing Ukoniq and switch patients to alternative treatments” and to “inform patients currently taking Ukoniq of the increased risk of death seen in the clinical trial and advise them to stop taking the medicine.”

In special instances in which a patient may be benefiting from the drug, the company plans to make umbralisib available under expanded access.

The FDA also recommends that patients who discontinue taking the drug dispose of unused umbralisib using a drug take-back location, such as a pharmacy, or throwing it away in the household trash after placing it in a sealed bag mixed with dirt or cat litter and removing personal identification information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Umbralisib had received accelerated approval in February 2021 to treat adults with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma following at least one prior therapy and those with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma who had received at least three prior therapies.

But safety concerns began to emerge in the phase 3 UNITY-CLL trial, which evaluated the drug in a related cancer type: chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Last February, the FDA said it was investigating a possible increased risk of death associated with umbralisib.

Five months later, the results are in.

“Updated findings from the UNITY-CLL clinical trial continued to show a possible increased risk of death in patients receiving Ukoniq. As a result, we determined the risks of treatment with Ukoniq outweigh its benefits,” the FDA wrote in a drug safety communication published June 1.

In April, the drug manufacturer, TG Therapeutics, announced it was voluntarily withdrawing umbralisib from the market for its approved uses in marginal zone lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.

The FDA’s safety notice includes instructions for physicians and patients. The FDA urges health care professionals to “stop prescribing Ukoniq and switch patients to alternative treatments” and to “inform patients currently taking Ukoniq of the increased risk of death seen in the clinical trial and advise them to stop taking the medicine.”

In special instances in which a patient may be benefiting from the drug, the company plans to make umbralisib available under expanded access.

The FDA also recommends that patients who discontinue taking the drug dispose of unused umbralisib using a drug take-back location, such as a pharmacy, or throwing it away in the household trash after placing it in a sealed bag mixed with dirt or cat litter and removing personal identification information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOARDING psychiatric patients in the ED: Key strategies

Boarding of psychiatric patients in the emergency department (ED) has been well documented.1 Numerous researchers have discussed ways to address this public health crisis. In this Pearl, I use the acronym BOARDING to provide key strategies for psychiatric clinicians managing psychiatric patients who are boarding in an ED.

Be vigilant. As a patient’s time waiting in the ED increases, watch for clinical blind spots. New medical problems,2 psychiatric issues, or medication errors3 may unexpectedly arise since the patient was originally stabilized by emergency medicine clinicians.

Orders. Since the patient could be waiting in the ED for 24 hours or longer, consider starting orders (eg, precautions, medications, diet, vital sign checks, labs, etc) as you would for a patient in an inpatient psychiatric unit or a dedicated psychiatric ED.

AWOL. Unlike inpatient psychiatric units, EDs generally are not locked. Extra resources (eg, sitter, safety alarm bracelet) may be needed to help prevent patients from leaving this setting unnoticed, especially those on involuntary psychiatric holds.

Re-evaluate. Ideally, re-evaluate the patient every shift. Does the patient still need an inpatient psychiatric setting? Can the involuntary psychiatric hold be discontinued?

Disposition. Is there a family member or reliable caregiver to whom the patient can be discharged? Can the patient go to a shelter or be stabilized in a short-term residential program, instead of an inpatient psychiatric unit?

Inpatient. If the patient waits 24 hours or longer, begin thinking like an inpatient psychiatric clinician. Are there any interventions you can reasonably begin in the ED that you would otherwise begin on an inpatient psychiatric unit?

Nursing. Work with ED nursing staff to familiarize them with the patient’s specific needs.

Guidelines. With the input of clinical and administrative leadership, establish local hospital-based guidelines for managing psychiatric patients who are boarding in the ED.

1. Nordstrom K, Berlin JS, Nash SS, et al. Boarding of mentally ill patients in emergency departments: American Psychiatric Association Resource Document. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(5):690-695.

2. Garfinkel E, Rose D, Strouse K, et al. Psychiatric emergency department boarding: from catatonia to cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(3):543-544.

3. Bakhsh HT, Perona SJ, Shields WA, et al. Medication errors in psychiatric patients boarded in the emergency department. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2014;26(4):191-198.

Boarding of psychiatric patients in the emergency department (ED) has been well documented.1 Numerous researchers have discussed ways to address this public health crisis. In this Pearl, I use the acronym BOARDING to provide key strategies for psychiatric clinicians managing psychiatric patients who are boarding in an ED.

Be vigilant. As a patient’s time waiting in the ED increases, watch for clinical blind spots. New medical problems,2 psychiatric issues, or medication errors3 may unexpectedly arise since the patient was originally stabilized by emergency medicine clinicians.

Orders. Since the patient could be waiting in the ED for 24 hours or longer, consider starting orders (eg, precautions, medications, diet, vital sign checks, labs, etc) as you would for a patient in an inpatient psychiatric unit or a dedicated psychiatric ED.

AWOL. Unlike inpatient psychiatric units, EDs generally are not locked. Extra resources (eg, sitter, safety alarm bracelet) may be needed to help prevent patients from leaving this setting unnoticed, especially those on involuntary psychiatric holds.

Re-evaluate. Ideally, re-evaluate the patient every shift. Does the patient still need an inpatient psychiatric setting? Can the involuntary psychiatric hold be discontinued?

Disposition. Is there a family member or reliable caregiver to whom the patient can be discharged? Can the patient go to a shelter or be stabilized in a short-term residential program, instead of an inpatient psychiatric unit?

Inpatient. If the patient waits 24 hours or longer, begin thinking like an inpatient psychiatric clinician. Are there any interventions you can reasonably begin in the ED that you would otherwise begin on an inpatient psychiatric unit?

Nursing. Work with ED nursing staff to familiarize them with the patient’s specific needs.

Guidelines. With the input of clinical and administrative leadership, establish local hospital-based guidelines for managing psychiatric patients who are boarding in the ED.

Boarding of psychiatric patients in the emergency department (ED) has been well documented.1 Numerous researchers have discussed ways to address this public health crisis. In this Pearl, I use the acronym BOARDING to provide key strategies for psychiatric clinicians managing psychiatric patients who are boarding in an ED.

Be vigilant. As a patient’s time waiting in the ED increases, watch for clinical blind spots. New medical problems,2 psychiatric issues, or medication errors3 may unexpectedly arise since the patient was originally stabilized by emergency medicine clinicians.

Orders. Since the patient could be waiting in the ED for 24 hours or longer, consider starting orders (eg, precautions, medications, diet, vital sign checks, labs, etc) as you would for a patient in an inpatient psychiatric unit or a dedicated psychiatric ED.

AWOL. Unlike inpatient psychiatric units, EDs generally are not locked. Extra resources (eg, sitter, safety alarm bracelet) may be needed to help prevent patients from leaving this setting unnoticed, especially those on involuntary psychiatric holds.

Re-evaluate. Ideally, re-evaluate the patient every shift. Does the patient still need an inpatient psychiatric setting? Can the involuntary psychiatric hold be discontinued?

Disposition. Is there a family member or reliable caregiver to whom the patient can be discharged? Can the patient go to a shelter or be stabilized in a short-term residential program, instead of an inpatient psychiatric unit?

Inpatient. If the patient waits 24 hours or longer, begin thinking like an inpatient psychiatric clinician. Are there any interventions you can reasonably begin in the ED that you would otherwise begin on an inpatient psychiatric unit?

Nursing. Work with ED nursing staff to familiarize them with the patient’s specific needs.

Guidelines. With the input of clinical and administrative leadership, establish local hospital-based guidelines for managing psychiatric patients who are boarding in the ED.

1. Nordstrom K, Berlin JS, Nash SS, et al. Boarding of mentally ill patients in emergency departments: American Psychiatric Association Resource Document. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(5):690-695.

2. Garfinkel E, Rose D, Strouse K, et al. Psychiatric emergency department boarding: from catatonia to cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(3):543-544.

3. Bakhsh HT, Perona SJ, Shields WA, et al. Medication errors in psychiatric patients boarded in the emergency department. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2014;26(4):191-198.

1. Nordstrom K, Berlin JS, Nash SS, et al. Boarding of mentally ill patients in emergency departments: American Psychiatric Association Resource Document. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(5):690-695.

2. Garfinkel E, Rose D, Strouse K, et al. Psychiatric emergency department boarding: from catatonia to cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(3):543-544.

3. Bakhsh HT, Perona SJ, Shields WA, et al. Medication errors in psychiatric patients boarded in the emergency department. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2014;26(4):191-198.

Coffee drinkers – even those with a sweet tooth – live longer

Among more than 170,000 people in the United Kingdom, those who drank about two to four cups of coffee a day, with or without sugar, had a lower rate of death than those who didn’t drink coffee, reported lead author Dan Liu, MD, of the department of epidemiology at Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

“Previous observational studies have suggested an association between coffee intake and reduced risk for death, but they did not distinguish between coffee consumed with sugar or artificial sweeteners and coffee consumed without,” Dr. Liu, who is also of the department of public health and preventive medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine.

To learn more, the investigators turned to the UK Biobank, which recruited approximately half a million participants in the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2010 to undergo a variety of questionnaires, interviews, physical measurements, and medical tests. Out of this group, 171,616 participants completed at least one dietary questionnaire and met the criteria for the present study, including lack of cancer or cardiovascular disease upon enrollment.

Results from these questionnaires showed that 55.4% of participants drank coffee without any sweetener, 14.3% drank coffee with sugar, 6.1% drank coffee with artificial sweetener, and 24.2% did not drink coffee at all. Coffee drinkers were further sorted into groups based on how many cups of coffee they drank per day.

Coffee drinkers were significantly less likely to die from any cause

Over the course of about 7 years, 3,177 of the participants died, including 1,725 who died from cancer and 628 who died from cardiovascular disease.

After accounting for other factors that might impact risk of death, like lifestyle choices, the investigators found that coffee drinkers were significantly less likely to die from any cause, cardiovascular disease, or cancer, than those who didn’t drink coffee at all. This benefit was observed across types of coffee, including ground, instant, and decaffeinated varieties. The protective effects of coffee were most apparent in people who drank about two to four cups a day, among whom death was about 30% less likely, regardless of whether they added sugar to their coffee or not. Individuals who drank coffee with artificial sweetener did not live significantly longer than those who drank no coffee at all; however, the investigators suggested that this result may have been skewed by higher rates of negative health factors, such as obesity and hypertension, in the artificial sweetener group.

Dr. Liu and colleagues noted that their findings align with previous studies linking coffee consumption with survival. Like those other studies, the present data revealed a “U-shaped” benefit curve, in which moderate coffee consumption was associated with longer life, whereas low or no consumption and high consumption were not.

Experts caution against drinking sweetened beverages despite new findings

Although the present findings suggested that adding sugar did not eliminate the health benefits of coffee, Dr. Liu and colleagues still cautioned against sweetened beverages, citing widely known associations between sugar consumption and poor health.

In an accompanying editorial, Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, deputy editor of Annals of Internal Medicine, pointed out a key detail from the data: the amount of sugar added to coffee in the U.K. study may be dwarfed by the amount consumed by some coffee drinkers across the pond.

“The average dose of added sugar per cup of sweetened coffee [in the study] was only a little over a teaspoon, or about 4 grams,” Dr. Wee wrote. “This is a far cry from the 15 grams of sugar in an 8-ounce cup of caramel macchiato at a popular U.S. coffee chain.”

Still, Dr. Wee, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the obesity research program in the division of general medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, suggested that your typical coffee drinker can feel safe in their daily habit.

“The evidence does not suggest a need for most coffee drinkers – particularly those who drink it with no or modest amounts of sugar – to eliminate coffee,” she wrote. “So drink up – but it would be prudent to avoid too many caramel macchiatos while more evidence brews.”

Estefanía Toledo, MD, MPH, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, offered a similar takeaway.

“For those who enjoy drinking coffee, are not pregnant or lactating, and do not have special health conditions, coffee consumption could be considered part of a healthy lifestyle,” Dr. Toledo said in a written comment. “I would recommend adding as little sugar as possible to coffee until more evidence has been accrued.”

Dr. Toledo, who previously published a study showing a link between coffee and extended survival, noted that moderate coffee consumption has “repeatedly” been associated with lower rates of “several chronic diseases” and death, but there still isn’t enough evidence to recommend coffee for those who don’t already drink it.

More long-term research is needed, Dr. Toledo said, ideally with studies comparing changes in coffee consumption and health outcomes over time. These may not be forthcoming, however, as such trials are “not easy and feasible to conduct.”

David Kao, MD, assistant professor of medicine-cardiology and medical director of the school of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said that the study conducted by Dr. Liu and colleagues is a “very well-executed analysis” that strengthens our confidence in the safety of long-term coffee consumption, even for patients with heart disease.

Dr. Kao, who recently published an analysis showing that higher coffee intake is associated with a lower risk of heart failure, refrained from advising anyone to up their coffee quota.

“I remain cautious about stating too strongly that people should increase coffee intake purely to improve survival,” Dr. Kao said in a written comment. “That said, it does not appear harmful to increase it some, until you drink consistently more than six to seven cups per day.”

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by CAST, the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, and others. Dr. Toledo and Dr. Kao disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Among more than 170,000 people in the United Kingdom, those who drank about two to four cups of coffee a day, with or without sugar, had a lower rate of death than those who didn’t drink coffee, reported lead author Dan Liu, MD, of the department of epidemiology at Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

“Previous observational studies have suggested an association between coffee intake and reduced risk for death, but they did not distinguish between coffee consumed with sugar or artificial sweeteners and coffee consumed without,” Dr. Liu, who is also of the department of public health and preventive medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine.

To learn more, the investigators turned to the UK Biobank, which recruited approximately half a million participants in the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2010 to undergo a variety of questionnaires, interviews, physical measurements, and medical tests. Out of this group, 171,616 participants completed at least one dietary questionnaire and met the criteria for the present study, including lack of cancer or cardiovascular disease upon enrollment.

Results from these questionnaires showed that 55.4% of participants drank coffee without any sweetener, 14.3% drank coffee with sugar, 6.1% drank coffee with artificial sweetener, and 24.2% did not drink coffee at all. Coffee drinkers were further sorted into groups based on how many cups of coffee they drank per day.

Coffee drinkers were significantly less likely to die from any cause

Over the course of about 7 years, 3,177 of the participants died, including 1,725 who died from cancer and 628 who died from cardiovascular disease.

After accounting for other factors that might impact risk of death, like lifestyle choices, the investigators found that coffee drinkers were significantly less likely to die from any cause, cardiovascular disease, or cancer, than those who didn’t drink coffee at all. This benefit was observed across types of coffee, including ground, instant, and decaffeinated varieties. The protective effects of coffee were most apparent in people who drank about two to four cups a day, among whom death was about 30% less likely, regardless of whether they added sugar to their coffee or not. Individuals who drank coffee with artificial sweetener did not live significantly longer than those who drank no coffee at all; however, the investigators suggested that this result may have been skewed by higher rates of negative health factors, such as obesity and hypertension, in the artificial sweetener group.

Dr. Liu and colleagues noted that their findings align with previous studies linking coffee consumption with survival. Like those other studies, the present data revealed a “U-shaped” benefit curve, in which moderate coffee consumption was associated with longer life, whereas low or no consumption and high consumption were not.

Experts caution against drinking sweetened beverages despite new findings

Although the present findings suggested that adding sugar did not eliminate the health benefits of coffee, Dr. Liu and colleagues still cautioned against sweetened beverages, citing widely known associations between sugar consumption and poor health.

In an accompanying editorial, Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, deputy editor of Annals of Internal Medicine, pointed out a key detail from the data: the amount of sugar added to coffee in the U.K. study may be dwarfed by the amount consumed by some coffee drinkers across the pond.

“The average dose of added sugar per cup of sweetened coffee [in the study] was only a little over a teaspoon, or about 4 grams,” Dr. Wee wrote. “This is a far cry from the 15 grams of sugar in an 8-ounce cup of caramel macchiato at a popular U.S. coffee chain.”

Still, Dr. Wee, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the obesity research program in the division of general medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, suggested that your typical coffee drinker can feel safe in their daily habit.

“The evidence does not suggest a need for most coffee drinkers – particularly those who drink it with no or modest amounts of sugar – to eliminate coffee,” she wrote. “So drink up – but it would be prudent to avoid too many caramel macchiatos while more evidence brews.”

Estefanía Toledo, MD, MPH, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, offered a similar takeaway.

“For those who enjoy drinking coffee, are not pregnant or lactating, and do not have special health conditions, coffee consumption could be considered part of a healthy lifestyle,” Dr. Toledo said in a written comment. “I would recommend adding as little sugar as possible to coffee until more evidence has been accrued.”

Dr. Toledo, who previously published a study showing a link between coffee and extended survival, noted that moderate coffee consumption has “repeatedly” been associated with lower rates of “several chronic diseases” and death, but there still isn’t enough evidence to recommend coffee for those who don’t already drink it.

More long-term research is needed, Dr. Toledo said, ideally with studies comparing changes in coffee consumption and health outcomes over time. These may not be forthcoming, however, as such trials are “not easy and feasible to conduct.”

David Kao, MD, assistant professor of medicine-cardiology and medical director of the school of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said that the study conducted by Dr. Liu and colleagues is a “very well-executed analysis” that strengthens our confidence in the safety of long-term coffee consumption, even for patients with heart disease.

Dr. Kao, who recently published an analysis showing that higher coffee intake is associated with a lower risk of heart failure, refrained from advising anyone to up their coffee quota.

“I remain cautious about stating too strongly that people should increase coffee intake purely to improve survival,” Dr. Kao said in a written comment. “That said, it does not appear harmful to increase it some, until you drink consistently more than six to seven cups per day.”

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by CAST, the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, and others. Dr. Toledo and Dr. Kao disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Among more than 170,000 people in the United Kingdom, those who drank about two to four cups of coffee a day, with or without sugar, had a lower rate of death than those who didn’t drink coffee, reported lead author Dan Liu, MD, of the department of epidemiology at Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

“Previous observational studies have suggested an association between coffee intake and reduced risk for death, but they did not distinguish between coffee consumed with sugar or artificial sweeteners and coffee consumed without,” Dr. Liu, who is also of the department of public health and preventive medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine.

To learn more, the investigators turned to the UK Biobank, which recruited approximately half a million participants in the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2010 to undergo a variety of questionnaires, interviews, physical measurements, and medical tests. Out of this group, 171,616 participants completed at least one dietary questionnaire and met the criteria for the present study, including lack of cancer or cardiovascular disease upon enrollment.

Results from these questionnaires showed that 55.4% of participants drank coffee without any sweetener, 14.3% drank coffee with sugar, 6.1% drank coffee with artificial sweetener, and 24.2% did not drink coffee at all. Coffee drinkers were further sorted into groups based on how many cups of coffee they drank per day.

Coffee drinkers were significantly less likely to die from any cause

Over the course of about 7 years, 3,177 of the participants died, including 1,725 who died from cancer and 628 who died from cardiovascular disease.

After accounting for other factors that might impact risk of death, like lifestyle choices, the investigators found that coffee drinkers were significantly less likely to die from any cause, cardiovascular disease, or cancer, than those who didn’t drink coffee at all. This benefit was observed across types of coffee, including ground, instant, and decaffeinated varieties. The protective effects of coffee were most apparent in people who drank about two to four cups a day, among whom death was about 30% less likely, regardless of whether they added sugar to their coffee or not. Individuals who drank coffee with artificial sweetener did not live significantly longer than those who drank no coffee at all; however, the investigators suggested that this result may have been skewed by higher rates of negative health factors, such as obesity and hypertension, in the artificial sweetener group.

Dr. Liu and colleagues noted that their findings align with previous studies linking coffee consumption with survival. Like those other studies, the present data revealed a “U-shaped” benefit curve, in which moderate coffee consumption was associated with longer life, whereas low or no consumption and high consumption were not.

Experts caution against drinking sweetened beverages despite new findings

Although the present findings suggested that adding sugar did not eliminate the health benefits of coffee, Dr. Liu and colleagues still cautioned against sweetened beverages, citing widely known associations between sugar consumption and poor health.

In an accompanying editorial, Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, deputy editor of Annals of Internal Medicine, pointed out a key detail from the data: the amount of sugar added to coffee in the U.K. study may be dwarfed by the amount consumed by some coffee drinkers across the pond.

“The average dose of added sugar per cup of sweetened coffee [in the study] was only a little over a teaspoon, or about 4 grams,” Dr. Wee wrote. “This is a far cry from the 15 grams of sugar in an 8-ounce cup of caramel macchiato at a popular U.S. coffee chain.”

Still, Dr. Wee, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the obesity research program in the division of general medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, suggested that your typical coffee drinker can feel safe in their daily habit.

“The evidence does not suggest a need for most coffee drinkers – particularly those who drink it with no or modest amounts of sugar – to eliminate coffee,” she wrote. “So drink up – but it would be prudent to avoid too many caramel macchiatos while more evidence brews.”

Estefanía Toledo, MD, MPH, PhD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, offered a similar takeaway.

“For those who enjoy drinking coffee, are not pregnant or lactating, and do not have special health conditions, coffee consumption could be considered part of a healthy lifestyle,” Dr. Toledo said in a written comment. “I would recommend adding as little sugar as possible to coffee until more evidence has been accrued.”

Dr. Toledo, who previously published a study showing a link between coffee and extended survival, noted that moderate coffee consumption has “repeatedly” been associated with lower rates of “several chronic diseases” and death, but there still isn’t enough evidence to recommend coffee for those who don’t already drink it.

More long-term research is needed, Dr. Toledo said, ideally with studies comparing changes in coffee consumption and health outcomes over time. These may not be forthcoming, however, as such trials are “not easy and feasible to conduct.”

David Kao, MD, assistant professor of medicine-cardiology and medical director of the school of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said that the study conducted by Dr. Liu and colleagues is a “very well-executed analysis” that strengthens our confidence in the safety of long-term coffee consumption, even for patients with heart disease.

Dr. Kao, who recently published an analysis showing that higher coffee intake is associated with a lower risk of heart failure, refrained from advising anyone to up their coffee quota.

“I remain cautious about stating too strongly that people should increase coffee intake purely to improve survival,” Dr. Kao said in a written comment. “That said, it does not appear harmful to increase it some, until you drink consistently more than six to seven cups per day.”

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by CAST, the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, and others. Dr. Toledo and Dr. Kao disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Are docs getting fed up with hearing about burnout?

There is a feeling of exhaustion, being unable to shake a lingering cold, suffering from frequent headaches and gastrointestinal disturbances, sleeplessness and shortness of breath ...

That was how burnout was described by clinical psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, who first used the phrase in a paper back in 1974, after observing the emotional depletion and accompanying psychosomatic symptoms among volunteer staff of a free clinic in New York City. He called it “burnout,” a term borrowed from the slang of substance abusers.

It has now been established beyond a shadow of a doubt that burnout is a serious issue facing physicians across specialties, albeit some more intensely than others. But with the constant barrage of stories published on an almost daily basis, along with studies and surveys, it begs the question:

Some have suggested that the focus should be more on tackling burnout and instituting viable solutions rather than rehashing the problem.

There haven’t been studies or surveys on this question, but several experts have offered their opinion.

Jonathan Fisher, MD, a cardiologist and organizational well-being and resiliency leader at Novant Health, Charlotte, N.C., cautioned that he hesitates to speak about what physicians in general believe. “We are a diverse group of nearly 1 million in the United States alone,” he said.

But he noted that there is a specific phenomenon among burned-out health care providers who are “burned out on burnout.”

“Essentially, the underlying thought is ‘talk is cheap and we want action,’” said Dr. Fisher, who is chair and co-founder of the Ending Physician Burnout Global Summit that was held in 2021. “This reaction is often a reflection of disheartened physicians’ sense of hopelessness and cynicism that systemic change to improve working conditions will happen in our lifetime.”

Dr. Fisher explained that “typically, anyone suffering – physicians or nonphysicians – cares more about ending the suffering as soon as possible than learning its causes, but to alleviate suffering at its core – including the emotional suffering of burnout – we must understand the many causes.”

“To address both the organizational and individual drivers of burnout requires a keen awareness of the thoughts, fears, and dreams of physicians, health care executives, and all other stakeholders in health care,” he added.

Burnout, of course, is a very real problem. The 2022 Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report found that nearly half of all respondents (47%) said they are burned out, which was higher than the prior year. Perhaps not surprisingly, burnout among emergency physicians took the biggest leap, jumping from 43% in 2021 to 60% this year. More than half of critical care physicians (56%) also reported that they were burned out.

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) – the official compendium of diseases – has categorized burnout as a “syndrome” that results from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” It is considered to be an occupational phenomenon and is not classified as a medical condition.

But whether or not physicians are burned out on hearing about burnout remains unclear. “I am not sure if physicians are tired of hearing about ‘burnout,’ but I do think that they want to hear about solutions that go beyond just telling them to take better care of themselves,” said Anne Thorndike, MD, MPH, an internal medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “There are major systematic factors that contribute to physicians burning out.”

Why talk about negative outcomes?

Jonathan Ripp, MD, MPH, however, is familiar with this sentiment. “‘Why do we keep identifying a problem without solutions’ is certainly a sentiment that is being expressed,” he said. “It’s a negative outcome, so why do we keep talking about negative outcomes?”

Dr. Ripp, who is a professor of medicine, medical education, and geriatrics and palliative medicine; the senior associate dean for well-being and resilience; and chief wellness officer at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is also a well-known expert and researcher in burnout and physician well-being.

He noted that burnout was one of the first “tools” used as a metric to measure well-being, but it is a negative measurement. “It’s been around a long time, so it has a lot of evidence,” said Dr. Ripp. “But that said, there are other ways of measuring well-being without a negative association, and ways of measuring meaning in work – fulfillment and satisfaction, and so on. It should be balanced.”

But for the average physician not familiar with the long legacy of research, they may be frustrated by this situation. “Then they ask, ‘Why are you just showing me more of this instead of doing something about it?’ but we are actually doing something about it,” said Dr. Ripp.

There are many efforts underway, he explained, but it’s a challenging and complex issue. “There are numerous drivers impacting the well-being of any given segment within the health care workforce,” he said. “It will also vary by discipline and location, and there are also a host of individual factors that may have very little to do with the work environment. There are some very well-established efforts for an organizational approach, but it remains to be seen which is the most effective.”

But in broad strokes, he continued, it’s about tackling the system and not about making an individual more resilient. “Individuals that do engage in activities that improve resilience do better, but that’s not what this is about – it’s not going to solve the problem,” said Dr. Ripp. “Those of us like myself, who are working in this space, are trying to promote a culture of well-being – at the system level.”

The question is how to enable the workforce to do their best work in an efficient way so that the balance of their activities are not the meaningless aspects. “And instead, shoot that balance to the meaningful aspects of work,” he added. “There are enormous challenges, but even though we are working on solutions, I can see how the individual may not see that – they may say, ‘Stop telling me to be resilient, stop telling me there’s a problem,’ but we’re working on it.”

Moving medicine forward

James Jerzak, MD, a family physician in Green Bay, Wisc., and physician lead at Bellin Health, noted that “it seems to me that doctors aren’t burned out talking about burnout, but they are burned out hearing that the solution to burnout is simply for them to become more resilient,” he said. “In actuality, the path to dealing with this huge problem is to make meaningful systemic changes in how medicine is practiced.”

He reiterated that medical care has become increasingly complex, with the aging of the population; the increasing incidence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes; the challenges with the increasing cost of care, higher copays, and lack of health insurance for a large portion of the country; and general incivility toward health care workers that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

“This has all led to significantly increased stress levels for medical workers,” he said. “Couple all of that with the increased work involved in meeting the demands of the electronic health record, and it is clear that the current situation is unsustainable.”

In his own health care system, moving medicine forward has meant advancing team-based care, which translates to expanding teams to include adequate support for physicians. This strategy addressed problems in health care delivery, part of which is burnout.

“In many systems practicing advanced team-based care, the ancillary staff – medical assistants, LPNs, and RNs – play an enhanced role in the patient visit and perform functions such as quality care gap closure, medication review and refill pending, pending orders, and helping with documentation,” he said. “Although the current health care workforce shortages has created challenges, there are a lot of innovative approaches being tried [that are] aimed at providing solutions.”

The second key factor is for systems is to develop robust support for their providers with a broad range of team members, such as case managers, clinical pharmacists, diabetic educators, care coordinators, and others. “The day has passed where individual physicians can effectivity manage all of the complexities of care, especially since there are so many nonclinical factors affecting care,” said Dr. Jerzak.

“The recent focus on the social determinants of health and health equity underlies the fact that it truly takes a team of health care professionals working together to provide optimal care for patients,” he said.

Dr. Thorndike, who mentors premedical and medical trainees, has pointed out that burnout begins way before an individual enters the workplace as a doctor. Burnout begins in the earliest stages of medical practice, with the application process to medical school. The admissions process extends over a 12-month period, causing a great deal of “toxic stress.”

One study found that, compared with non-premedical students, premedical students had greater depression severity and emotional exhaustion.

“The current system of medical school admissions ignores the toll that the lengthy and emotionally exhausting process takes on aspiring physicians,” she said. “This is just one example of many in training and health care that requires physicians to set aside their own lives to achieve their goals and to provide the best possible care to others.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is a feeling of exhaustion, being unable to shake a lingering cold, suffering from frequent headaches and gastrointestinal disturbances, sleeplessness and shortness of breath ...

That was how burnout was described by clinical psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, who first used the phrase in a paper back in 1974, after observing the emotional depletion and accompanying psychosomatic symptoms among volunteer staff of a free clinic in New York City. He called it “burnout,” a term borrowed from the slang of substance abusers.

It has now been established beyond a shadow of a doubt that burnout is a serious issue facing physicians across specialties, albeit some more intensely than others. But with the constant barrage of stories published on an almost daily basis, along with studies and surveys, it begs the question:

Some have suggested that the focus should be more on tackling burnout and instituting viable solutions rather than rehashing the problem.

There haven’t been studies or surveys on this question, but several experts have offered their opinion.

Jonathan Fisher, MD, a cardiologist and organizational well-being and resiliency leader at Novant Health, Charlotte, N.C., cautioned that he hesitates to speak about what physicians in general believe. “We are a diverse group of nearly 1 million in the United States alone,” he said.

But he noted that there is a specific phenomenon among burned-out health care providers who are “burned out on burnout.”

“Essentially, the underlying thought is ‘talk is cheap and we want action,’” said Dr. Fisher, who is chair and co-founder of the Ending Physician Burnout Global Summit that was held in 2021. “This reaction is often a reflection of disheartened physicians’ sense of hopelessness and cynicism that systemic change to improve working conditions will happen in our lifetime.”

Dr. Fisher explained that “typically, anyone suffering – physicians or nonphysicians – cares more about ending the suffering as soon as possible than learning its causes, but to alleviate suffering at its core – including the emotional suffering of burnout – we must understand the many causes.”

“To address both the organizational and individual drivers of burnout requires a keen awareness of the thoughts, fears, and dreams of physicians, health care executives, and all other stakeholders in health care,” he added.

Burnout, of course, is a very real problem. The 2022 Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report found that nearly half of all respondents (47%) said they are burned out, which was higher than the prior year. Perhaps not surprisingly, burnout among emergency physicians took the biggest leap, jumping from 43% in 2021 to 60% this year. More than half of critical care physicians (56%) also reported that they were burned out.

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) – the official compendium of diseases – has categorized burnout as a “syndrome” that results from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” It is considered to be an occupational phenomenon and is not classified as a medical condition.

But whether or not physicians are burned out on hearing about burnout remains unclear. “I am not sure if physicians are tired of hearing about ‘burnout,’ but I do think that they want to hear about solutions that go beyond just telling them to take better care of themselves,” said Anne Thorndike, MD, MPH, an internal medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “There are major systematic factors that contribute to physicians burning out.”

Why talk about negative outcomes?

Jonathan Ripp, MD, MPH, however, is familiar with this sentiment. “‘Why do we keep identifying a problem without solutions’ is certainly a sentiment that is being expressed,” he said. “It’s a negative outcome, so why do we keep talking about negative outcomes?”

Dr. Ripp, who is a professor of medicine, medical education, and geriatrics and palliative medicine; the senior associate dean for well-being and resilience; and chief wellness officer at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is also a well-known expert and researcher in burnout and physician well-being.

He noted that burnout was one of the first “tools” used as a metric to measure well-being, but it is a negative measurement. “It’s been around a long time, so it has a lot of evidence,” said Dr. Ripp. “But that said, there are other ways of measuring well-being without a negative association, and ways of measuring meaning in work – fulfillment and satisfaction, and so on. It should be balanced.”

But for the average physician not familiar with the long legacy of research, they may be frustrated by this situation. “Then they ask, ‘Why are you just showing me more of this instead of doing something about it?’ but we are actually doing something about it,” said Dr. Ripp.

There are many efforts underway, he explained, but it’s a challenging and complex issue. “There are numerous drivers impacting the well-being of any given segment within the health care workforce,” he said. “It will also vary by discipline and location, and there are also a host of individual factors that may have very little to do with the work environment. There are some very well-established efforts for an organizational approach, but it remains to be seen which is the most effective.”

But in broad strokes, he continued, it’s about tackling the system and not about making an individual more resilient. “Individuals that do engage in activities that improve resilience do better, but that’s not what this is about – it’s not going to solve the problem,” said Dr. Ripp. “Those of us like myself, who are working in this space, are trying to promote a culture of well-being – at the system level.”

The question is how to enable the workforce to do their best work in an efficient way so that the balance of their activities are not the meaningless aspects. “And instead, shoot that balance to the meaningful aspects of work,” he added. “There are enormous challenges, but even though we are working on solutions, I can see how the individual may not see that – they may say, ‘Stop telling me to be resilient, stop telling me there’s a problem,’ but we’re working on it.”

Moving medicine forward

James Jerzak, MD, a family physician in Green Bay, Wisc., and physician lead at Bellin Health, noted that “it seems to me that doctors aren’t burned out talking about burnout, but they are burned out hearing that the solution to burnout is simply for them to become more resilient,” he said. “In actuality, the path to dealing with this huge problem is to make meaningful systemic changes in how medicine is practiced.”

He reiterated that medical care has become increasingly complex, with the aging of the population; the increasing incidence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes; the challenges with the increasing cost of care, higher copays, and lack of health insurance for a large portion of the country; and general incivility toward health care workers that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

“This has all led to significantly increased stress levels for medical workers,” he said. “Couple all of that with the increased work involved in meeting the demands of the electronic health record, and it is clear that the current situation is unsustainable.”

In his own health care system, moving medicine forward has meant advancing team-based care, which translates to expanding teams to include adequate support for physicians. This strategy addressed problems in health care delivery, part of which is burnout.

“In many systems practicing advanced team-based care, the ancillary staff – medical assistants, LPNs, and RNs – play an enhanced role in the patient visit and perform functions such as quality care gap closure, medication review and refill pending, pending orders, and helping with documentation,” he said. “Although the current health care workforce shortages has created challenges, there are a lot of innovative approaches being tried [that are] aimed at providing solutions.”

The second key factor is for systems is to develop robust support for their providers with a broad range of team members, such as case managers, clinical pharmacists, diabetic educators, care coordinators, and others. “The day has passed where individual physicians can effectivity manage all of the complexities of care, especially since there are so many nonclinical factors affecting care,” said Dr. Jerzak.

“The recent focus on the social determinants of health and health equity underlies the fact that it truly takes a team of health care professionals working together to provide optimal care for patients,” he said.

Dr. Thorndike, who mentors premedical and medical trainees, has pointed out that burnout begins way before an individual enters the workplace as a doctor. Burnout begins in the earliest stages of medical practice, with the application process to medical school. The admissions process extends over a 12-month period, causing a great deal of “toxic stress.”

One study found that, compared with non-premedical students, premedical students had greater depression severity and emotional exhaustion.

“The current system of medical school admissions ignores the toll that the lengthy and emotionally exhausting process takes on aspiring physicians,” she said. “This is just one example of many in training and health care that requires physicians to set aside their own lives to achieve their goals and to provide the best possible care to others.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is a feeling of exhaustion, being unable to shake a lingering cold, suffering from frequent headaches and gastrointestinal disturbances, sleeplessness and shortness of breath ...

That was how burnout was described by clinical psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, who first used the phrase in a paper back in 1974, after observing the emotional depletion and accompanying psychosomatic symptoms among volunteer staff of a free clinic in New York City. He called it “burnout,” a term borrowed from the slang of substance abusers.

It has now been established beyond a shadow of a doubt that burnout is a serious issue facing physicians across specialties, albeit some more intensely than others. But with the constant barrage of stories published on an almost daily basis, along with studies and surveys, it begs the question:

Some have suggested that the focus should be more on tackling burnout and instituting viable solutions rather than rehashing the problem.

There haven’t been studies or surveys on this question, but several experts have offered their opinion.

Jonathan Fisher, MD, a cardiologist and organizational well-being and resiliency leader at Novant Health, Charlotte, N.C., cautioned that he hesitates to speak about what physicians in general believe. “We are a diverse group of nearly 1 million in the United States alone,” he said.

But he noted that there is a specific phenomenon among burned-out health care providers who are “burned out on burnout.”

“Essentially, the underlying thought is ‘talk is cheap and we want action,’” said Dr. Fisher, who is chair and co-founder of the Ending Physician Burnout Global Summit that was held in 2021. “This reaction is often a reflection of disheartened physicians’ sense of hopelessness and cynicism that systemic change to improve working conditions will happen in our lifetime.”

Dr. Fisher explained that “typically, anyone suffering – physicians or nonphysicians – cares more about ending the suffering as soon as possible than learning its causes, but to alleviate suffering at its core – including the emotional suffering of burnout – we must understand the many causes.”

“To address both the organizational and individual drivers of burnout requires a keen awareness of the thoughts, fears, and dreams of physicians, health care executives, and all other stakeholders in health care,” he added.

Burnout, of course, is a very real problem. The 2022 Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report found that nearly half of all respondents (47%) said they are burned out, which was higher than the prior year. Perhaps not surprisingly, burnout among emergency physicians took the biggest leap, jumping from 43% in 2021 to 60% this year. More than half of critical care physicians (56%) also reported that they were burned out.

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) – the official compendium of diseases – has categorized burnout as a “syndrome” that results from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” It is considered to be an occupational phenomenon and is not classified as a medical condition.

But whether or not physicians are burned out on hearing about burnout remains unclear. “I am not sure if physicians are tired of hearing about ‘burnout,’ but I do think that they want to hear about solutions that go beyond just telling them to take better care of themselves,” said Anne Thorndike, MD, MPH, an internal medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “There are major systematic factors that contribute to physicians burning out.”

Why talk about negative outcomes?

Jonathan Ripp, MD, MPH, however, is familiar with this sentiment. “‘Why do we keep identifying a problem without solutions’ is certainly a sentiment that is being expressed,” he said. “It’s a negative outcome, so why do we keep talking about negative outcomes?”

Dr. Ripp, who is a professor of medicine, medical education, and geriatrics and palliative medicine; the senior associate dean for well-being and resilience; and chief wellness officer at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is also a well-known expert and researcher in burnout and physician well-being.

He noted that burnout was one of the first “tools” used as a metric to measure well-being, but it is a negative measurement. “It’s been around a long time, so it has a lot of evidence,” said Dr. Ripp. “But that said, there are other ways of measuring well-being without a negative association, and ways of measuring meaning in work – fulfillment and satisfaction, and so on. It should be balanced.”

But for the average physician not familiar with the long legacy of research, they may be frustrated by this situation. “Then they ask, ‘Why are you just showing me more of this instead of doing something about it?’ but we are actually doing something about it,” said Dr. Ripp.

There are many efforts underway, he explained, but it’s a challenging and complex issue. “There are numerous drivers impacting the well-being of any given segment within the health care workforce,” he said. “It will also vary by discipline and location, and there are also a host of individual factors that may have very little to do with the work environment. There are some very well-established efforts for an organizational approach, but it remains to be seen which is the most effective.”

But in broad strokes, he continued, it’s about tackling the system and not about making an individual more resilient. “Individuals that do engage in activities that improve resilience do better, but that’s not what this is about – it’s not going to solve the problem,” said Dr. Ripp. “Those of us like myself, who are working in this space, are trying to promote a culture of well-being – at the system level.”

The question is how to enable the workforce to do their best work in an efficient way so that the balance of their activities are not the meaningless aspects. “And instead, shoot that balance to the meaningful aspects of work,” he added. “There are enormous challenges, but even though we are working on solutions, I can see how the individual may not see that – they may say, ‘Stop telling me to be resilient, stop telling me there’s a problem,’ but we’re working on it.”

Moving medicine forward

James Jerzak, MD, a family physician in Green Bay, Wisc., and physician lead at Bellin Health, noted that “it seems to me that doctors aren’t burned out talking about burnout, but they are burned out hearing that the solution to burnout is simply for them to become more resilient,” he said. “In actuality, the path to dealing with this huge problem is to make meaningful systemic changes in how medicine is practiced.”

He reiterated that medical care has become increasingly complex, with the aging of the population; the increasing incidence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes; the challenges with the increasing cost of care, higher copays, and lack of health insurance for a large portion of the country; and general incivility toward health care workers that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

“This has all led to significantly increased stress levels for medical workers,” he said. “Couple all of that with the increased work involved in meeting the demands of the electronic health record, and it is clear that the current situation is unsustainable.”

In his own health care system, moving medicine forward has meant advancing team-based care, which translates to expanding teams to include adequate support for physicians. This strategy addressed problems in health care delivery, part of which is burnout.

“In many systems practicing advanced team-based care, the ancillary staff – medical assistants, LPNs, and RNs – play an enhanced role in the patient visit and perform functions such as quality care gap closure, medication review and refill pending, pending orders, and helping with documentation,” he said. “Although the current health care workforce shortages has created challenges, there are a lot of innovative approaches being tried [that are] aimed at providing solutions.”

The second key factor is for systems is to develop robust support for their providers with a broad range of team members, such as case managers, clinical pharmacists, diabetic educators, care coordinators, and others. “The day has passed where individual physicians can effectivity manage all of the complexities of care, especially since there are so many nonclinical factors affecting care,” said Dr. Jerzak.

“The recent focus on the social determinants of health and health equity underlies the fact that it truly takes a team of health care professionals working together to provide optimal care for patients,” he said.

Dr. Thorndike, who mentors premedical and medical trainees, has pointed out that burnout begins way before an individual enters the workplace as a doctor. Burnout begins in the earliest stages of medical practice, with the application process to medical school. The admissions process extends over a 12-month period, causing a great deal of “toxic stress.”

One study found that, compared with non-premedical students, premedical students had greater depression severity and emotional exhaustion.

“The current system of medical school admissions ignores the toll that the lengthy and emotionally exhausting process takes on aspiring physicians,” she said. “This is just one example of many in training and health care that requires physicians to set aside their own lives to achieve their goals and to provide the best possible care to others.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Very high HDL-C: Too much of a good thing?

A new study suggests that .

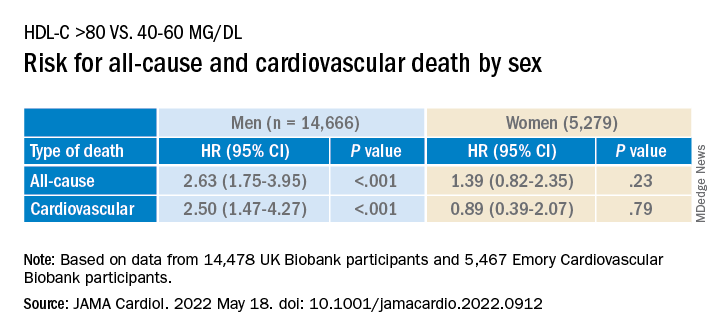

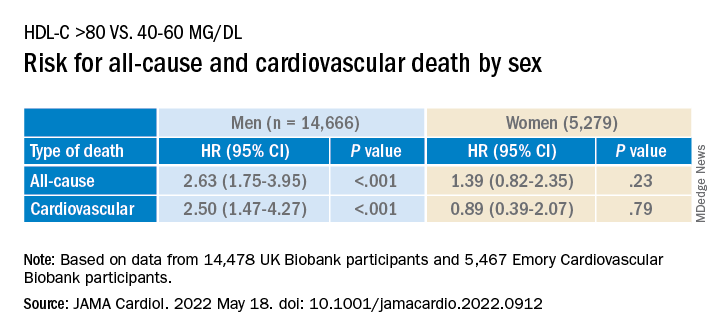

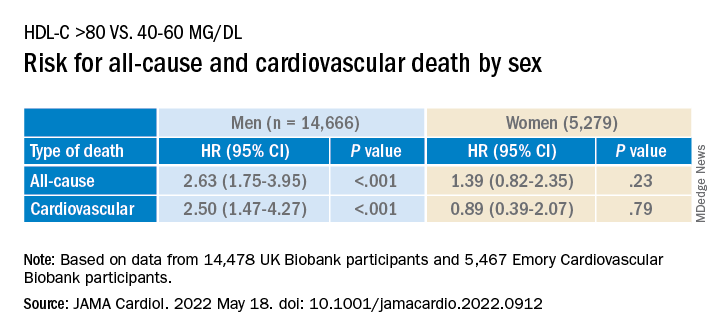

Investigators studied close to 10,000 patients with CAD in two separate cohorts. After adjusting for an array of covariates, they found that individuals with HDL-C levels greater than 80 mg/dL had a 96% higher risk for all-cause mortality and a 71% higher risk for cardiovascular mortality than those with HDL-C levels between 40 and 60 mg/dL.

A U-shaped association was found, with higher risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with both very low and very high, compared with midrange, HDL-C values.

“Very high HDL levels are associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes, not lower risk, as previously thought. This is true not only in the general population, but also in people with known coronary artery disease,” senior author Arshed A. Quyyumi, MD, professor of medicine, division of cardiology, Emory University, Atlanta, told this news organization.

“Physicians have to be cognizant of the fact that, at levels of HDL-C above 80 mg/dL, they [should be] more aggressive with risk reduction and not believe that the patient is at ‘low risk’ because of high levels of ‘good’ cholesterol,” said Dr. Quyyumi, director of the Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute.

The study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

Inverse association?

HDL-C levels have “historically been inversely associated with increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk; however, recent studies have questioned the efficacy of therapies designed to increase HDL-C levels,” the authors wrote. Moreover, genetic variants associated with HDL-C have not been found to be linked to CVD risk.

Whether “very high HDL-C levels in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) are associated with mortality risk remains unknown,” they wrote. In this study, the researchers investigated not only the potential risk of elevated HDL-C levels in these patients, but also the association of known HDL-C genetic variants with this risk.

To do so, they analyzed data from a subset of patients with CAD in two independent study groups: the UK Biobank (UKB; n = 14,478; mean [standard deviation] age, 61.2 [5.8] years; 76.2% male; 93.8% White) and the Emory Cardiovascular Biobank (EmCAB; n = 5,467; mean age, 63.8 [12.3] years; 66.4% male; 73.2% White). Participants were followed prospectively for a median of 8.9 (interquartile range, 8.0-9.7) years and 6.7 (IQR, 4.0-10.8) years, respectively.

Additional data collected included medical and medication history and demographic characteristics, which were used as covariates, as well as genomic information.

Of the UKB cohort, 12.4% and 7.9% sustained all-cause or cardiovascular death, respectively, during the follow-up period, and 1.8% of participants had an HDL-C level above 80 mg/dL.

Among these participants with very high HDL-C levels, 16.9% and 8.6% had all-cause or cardiovascular death, respectively. Compared with the reference category (HDL-C level of 40-60 mg/dL), those with low HDL-C levels (≤ 30 mg/dL) had an expected higher risk for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, even after adjustment for covariates (hazard ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.64 and HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.09-1.85, respectively; P = .009).

“Importantly,” the authors stated, “compared with the reference category, individuals with very high HDL-C levels (>80 mg/dL) also had a higher risk of all-cause death (HR, 1.58 [1.16-2.14], P = .004).”

Although cardiovascular death rates were not significantly greater in unadjusted analyses, after adjustment, the highest HDL-C group had an increased risk for all-cause and cardiovascular death (HR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.42-2.71; P < .001 and HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.09-2.68, respectively; P = .02).

Compared with females, males with HDL-C levels above 80 mg/dL had a higher risk for all-cause and cardiovascular death.

Similar findings were obtained in the EmCAB patients, 1.6% of whom had HDL-C levels above 80 mg/dL. During the follow-up period, 26.9% and 13.8% of participants sustained all-cause and cardiovascular death, respectively. Of those with HDL-C levels above 80 mg/dL, 30.0% and 16.7% experienced all-cause and cardiovascular death, respectively.

Compared with those with HDL-C levels of 40-60 mg/dL, those in the lowest (≤30 mg/dL) and highest (>80 mg/dL) groups had a “significant or near-significant greater risk for all-cause death in both unadjusted and fully adjusted models.

“Using adjusted HR curves, a U-shaped association between HDL-C and adverse events was evident with higher mortality at both very high and low HDL-C levels,” the authors noted.

Compared with patients without diabetes, those with diabetes and an HDL-C level above 80 mg/dL had a higher risk for all-cause and cardiovascular death, and patients younger than 65 years had a higher risk for cardiovascular death than patients 65 years and older.

The researchers found a “positive linear association” between the HDL-C genetic risk score (GRS) and HDL levels, wherein a 1-SD higher HDL-C GRS was associated with a 3.03 mg/dL higher HDL-C level (2.83-3.22; P < .001; R 2 = 0.06).

The HDL-C GRS was not associated with the risk for all-cause or cardiovascular death in unadjusted models, and after the HDL-C GRS was added to the fully adjusted models, the association with HDL-C level above 80 mg/dL was not attenuated, “indicating that HDL-C genetic variations in the GRS do not contribute substantially to the risk.”

“Potential mechanisms through which very high HDL-C might cause adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CAD need to be studied,” Dr. Quyyumi said. “Whether the functional capacity of the HDL particle is altered when the level is very high remains unknown. Whether it is more able to oxidize and thus shift from being protective to harmful also needs to be investigated.”

Red flag

Commenting for this news organization, Sadiya Sana Khan, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine (cardiology) and preventive medicine (epidemiology), Northwestern University, Chicago, said: “I think the most important point [of the study] is to identify people with very high HDL-C. This can serve as a reminder to discuss heart-healthy lifestyles and discussion of statin therapy if needed, based on LDL-C.”

In an accompanying editorial coauthored with Gregg Fonarow, MD, Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center, University of California, Los Angeles, the pair wrote: “Although the present findings may be related to residual confounding, high HDL-C levels should not automatically be assumed to be protective.”

They advised clinicians to “use HDL-C levels as a surrogate marker, with very low and very high levels as a red flag to target for more intensive primary and secondary prevention, as the maxim for HDL-C as ‘good’ cholesterol only holds for HDL-C levels of 80 mg/dL or less.”

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Abraham J. & Phyllis Katz Foundation. Dr. Quyyumi and coauthors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Khan reports receiving grants from the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr. Fonarow reports receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study suggests that .

Investigators studied close to 10,000 patients with CAD in two separate cohorts. After adjusting for an array of covariates, they found that individuals with HDL-C levels greater than 80 mg/dL had a 96% higher risk for all-cause mortality and a 71% higher risk for cardiovascular mortality than those with HDL-C levels between 40 and 60 mg/dL.

A U-shaped association was found, with higher risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with both very low and very high, compared with midrange, HDL-C values.

“Very high HDL levels are associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes, not lower risk, as previously thought. This is true not only in the general population, but also in people with known coronary artery disease,” senior author Arshed A. Quyyumi, MD, professor of medicine, division of cardiology, Emory University, Atlanta, told this news organization.

“Physicians have to be cognizant of the fact that, at levels of HDL-C above 80 mg/dL, they [should be] more aggressive with risk reduction and not believe that the patient is at ‘low risk’ because of high levels of ‘good’ cholesterol,” said Dr. Quyyumi, director of the Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute.

The study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

Inverse association?